Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 4

September 7, 2024

Telmarines: the ultimate Whenwes

Prince Caspian by C.S. Lewis

Prince Caspian by C.S. LewisMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

I've just finished reading Prince Caspian for the fourth time, and this time I read it chapter for chapter with Inside Prince Caspian by Devin Brown, and most of my comments on it will be found in my review of Inside Prince Caspian.

I will add one thing here, though -- that on this reading I was struck even more by how C.S. Lewis got it absolutely right about the notion of white supremacy -- which in Prince Caspian appears as Telmarine supremacy.

Back in the 1960s, when I first read it, Kenya had just become independent, and there was a flood of disgruntled white immigrants from Kenya into apartheid South Africa. They soon became known as "Whenwes" because of their habit of prefacing most things they said with the phrase "When we were in Keen-yah...".

They were also given much air time on South African radio (no TV in those days), especially by current affairs host Ivor Benson, who seemed to have a Whenwe from Kenya every week on his prime-time propaganda show, where they spread the message that the white man should rule, and black people were incompetent and unfit to govern.

One of the things we wondered about was why, if they wanted to get away from black people, white Kenyan immigrants didn't go to a country where there were no or few black people. Why did they come to South Africa, where the majority of the population were black?

It soon became apparent, however, from what they said on the radio, that they could not do without black people, because there would be no one to "clean my carpets, scrub the floors, and polish up the hearth". They needed black people, but only if they were subservient to white rule -- and that is exactly how C.S. Lewis portrays the Telmarines in Prince Caspian -- as the ultimate Whenwes. They were unwilling to stay in Narnia if they were no longer the ruling race, with all others subservient to them.

And C.S. Lewis nails it. He nails it absolutely. The Telmarines are the Platonic ideal Whenwes, white supremacists to the core.

View all my reviews

September 2, 2024

C.S. Lewis on Christian Nationalism

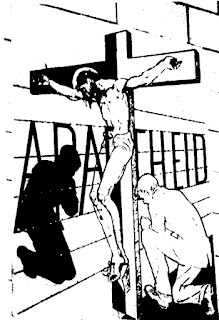

Christian Nationalism was the philosophical underpinning for the apartheid ideology of the National Party that ruled South Africa from 1948 to 1994. During that period Christian Nationalism was dominant and all-pervasive. Student teachers at universities were taught that they had to teach subjects like Geology in a "Christian National way". All children in schools were to be taught to be nationalist in their thinking, and nationalism was defined as "love of one's own".

But what is "one's own"?

Many Christian groups in South Africa at that time questioned the Christian Nationalist ideology, and some explicitly and outright rejected it. Christian Nationalism grew out of an attempt to give a Christian flavour to a romantic secular nationalism that had grown up in Europe, especially Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. For more on that, see my article on Nationalism, Violence and Reconciliation.

Now Christian Nationalism seems to be making a come-back in certain circles in North America, in Russia, and in some other places. Many Christians find this disturbing. Those of us who were involved in the struggle against apartheid from the 1950s to the 1980s are aware that Christian Nationalism was not merely a heresy, it was a pseudo-gospel, a false offer of salvation by race, not grace.

It was not merely South Africans who were aware of that, however. C.S. Lewis (1898–1963), a professor of English literature, author, and Christian apologist, was also acutely aware of the dangers of nationalism, and two of the villains of his fiction, Professor Weston of his space trilogy, and the dwarf Nikabrik in his children's book Prince Caspian exemplify the dangers.

Devin Brown, in his book Inside Prince Caspian, makes this clear in the following passage:

The only virtue remaining in Nikabrik at the time of his death was a concern -- it would be hard to call it a love -- for his own kind. Nikabrik allowed this virtue to expand until it became the greatest virtue, erasing all others. In this way he became like another of Lewis's villains: Professor Weston from the space trilogy. Near the end of Out of the Silent Planet, the great Oyarsa, or ruler, of Mars has a long conversation with Weston, trying to understand the reasoning behind the scientist's depraved actions. The Oyarsa maintains that there are laws that all sentient beings know, "pity and straight dealing and shame and the like". He points out that Weston is willing to break all of these laws except "the love of kindred," which he notes "is not one of the greatest laws." As this law became the only law and principle for both Weston and Nikabrik, it became bent and distorted and, in the end, led to evil, not good.

The "love of kindred" that Lewis talks about there is the "love of one's own" that the Afrikaner nationalists of South Africa's National Party gave as the definition of nationalism. And "own kind" was a nationalist mantra. It was the rationale for apartheid. People must live among their "own kind". They must go to school and church with their "own kind". They could only play games and sports with their "own kind". There were government departments and legislative bodies arranged according to "own affairs". And there were laws against "improper interference" in affairs that might concern everyone, and were not regarded by the government as "own affairs".

The "own kinds" were defined by law: White, Black, Coloured and Asian. And those took precedence over everything else. Christians could not see their fellow Christians as their "own kind". Own-kindedness was determined not by faith, but by race. So, under "Christian" nationalism, Christians were expected to sell their heavenly birthright for the pottage of this sinful world (cf Genesis 25:29-34).

The "own kinds" were defined by law: White, Black, Coloured and Asian. And those took precedence over everything else. Christians could not see their fellow Christians as their "own kind". Own-kindedness was determined not by faith, but by race. So, under "Christian" nationalism, Christians were expected to sell their heavenly birthright for the pottage of this sinful world (cf Genesis 25:29-34). For those who may be concerned about the viral spread of Christian Nationalism in the 2020s, therefore, there are remedies. Perhaps you can inoculate your children against the virus of Christian Nationalism by reading C.S. Lewis's Narnia stories to them, and noting the lessons to be learned from the failings of Nikabrik.

When they get older and become interested in "Young Adult" stories, encourage them to read Out of the Silent Planet and note the failings of Professor Weston.

And don't forget the words of Balthazar Johannes Vorster (1915-1983), who became South African Minister of Justice in 1961 (when he turned South Africa into a police state), Prime Minister in 1966, State President in 1978. But back in 1942 he said (when his country was at war with Germany, Italy and Japan):

We stand for Christian Nationalism, which is an ally of National Socialism. You can call the anti-democratic system dictatorship if you like. In Italy it is called Fascism, in Germany National Socialism, and in South Africa, Christian Nationalism.

September 1, 2024

11.22.63 by Stephen King

11.22.63 by Stephen King

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Stephen King's books are a mixed bag -- some very good, some very bad, and some mediocre. This one, I think, is one of his best. It's also difficult to classify. It involves time travel, so perhaps it is science fiction, but the time travel is not the result of any scientific discovery, and its mechanism is never explained. Fantasy then? But no, everything else in the story, apart from the time travel, is pretty mundane In that respect, it most resembles The Time Traveler's Wife by Audrey Niffenegger. It's also, to some extent, a love story, so one could perhaps add "romance" to the list of genres covered.

In the story Jake Epping, a school teacher in Maine, USA, is told by his friend Al Templeton about a time gateway, and Al tries to persuade him to go back in time from 2011 to prevent the assassination of President John Kennedy in 1963. The gateway, however, will only take him back to 1958, so if he accepts the task it will take five years of his life.

It has an interesting plot, and I had a great deal of sympathy for the main characters, and even for several of the minor ones.

The story has a great deal of historical information about the assassination of President Kennedy, and to some extent that part of the story was familiar to me. The names Lee Harvey Oswald and his killer Jack Ruby were familiar, as were references to the "grassy knoll" and the Texas Book Depository, not from reading history, but from contemporary news reports.

View all my reviews

August 12, 2024

What's your lifestyle?

Giovanni Gaggia, CEO of Real Estate Services, said that lifestyle estates offer a unique blend of luxury living and community engagement.But the shanty-town lifestyle estates of informal settlements not only don't offer such "typical" features as golf courses, fitness centres and nature reserves, they also do not typically have indoor plumbing, sewerage, proper roads or electricity.

The estates typically offer several amenities, including golf courses, fitness centres and nature reserves, which cater to various interests and promote an active lifestyle.

They also offer a secure environment and well-maintained infrastructure to add to their appeal.

The advertising hype suggests that only an affluent lifestyle of conspicuous consumption qualifies as a lifestyle at all.

The earliest reference to "lifestyle" in the Oxford English Dictionary was 1915, and it is defined as

A style or way of living (associated with an individual person, a society, etc.); esp. the characteristic manner in which a person lives (or chooses to live) his or her life.

It only became popular in the late 1960s, however, when it was used mainly to contrast the lifestyles of the "hip" and the "straight". The hippie counterculture espoused different values from those of "straight" society, and expressed these values through different lifestyles.

One of the values that hippies eschewed was the lifestyle of conspicuous consumption that was practised or aspired to by straight society.

The advertising industry, which was dedicated to promoting conspicuous consumption, fought back, and one of the ways it did so was by adopting hip jargon to promote products and services and sell them to the changing youth culture. "Lifestyle banking" was one of the earlier ones, illustrated with yachts and luxury cars.

Part of the countercultural lifestyle is, however, still reflected by my Collins Millennium Dictionary (does that make it a dictionary for "Millennials"?) which gives

lifestyle business a small business in which the owners are more anxious to pursue interests that reflect their lifestyle than to make more than a comfortable living.

Advertising hype has not taken over completely. We still talk about the lifestyle of hunter-gatherers as compared with the lifestyle of peasant farmers, neither of which would be found in the so-called "lifestyle estates".

Advertising hype has not taken over completely. We still talk about the lifestyle of hunter-gatherers as compared with the lifestyle of peasant farmers, neither of which would be found in the so-called "lifestyle estates".When the term first became popular it was variously spelt as "life style", "life-style" or "lifestyle", depending on the house style (house-style, housestyle) of the publication concerned, but now the "lifestyle" spelling predominates.

The point to remember here is that a lifestyle of poverty is just as much a lifestyle as a lifestyle of affluence, no matter how much the advertising agencies would like us to believe otherwise.

Another point to remember is found in the OED definition: the characteristic manner in which a person lives (or chooses to live) his or her life

A lifestyle may be voluntary or involuntary.

The lifestyle of a prisoner is involuntary.

The lifestyle of a person living in an affluent "lifestyle estate" is voluntary. If you can afford to live in one, you can also afford not to live in one. And if you can afford not to live in one, you can also choose to avoid an affluent lifestyle, and choose rather to live an abstemious one.

For most people, lifestyle is a mixture of voluntary and involuntary. Inmates of institutions like boarding schools, hostels, communes, monasteries, old-age homes, etc may have varying degrees of choice whether to enter such institutions, but, once within them, they need to adopt features of the prescribed lifestyle or leave.

To some extent, this might be true of "lifestyle estates" as well. The lifestyle is prescribed and circumscribed, sometimes even more than the lifestyle of informal settlements. If you live in a "lifestyle estate" and start erecting shacks in your backyard to sub-let to others, you would soon discover the limits of freedom in a "lifestyle estate".

There are many ways in which lifestyle is determined by circumstances, such as wealth or poverty, ones upbringing, one's education or the lack of it. But some, like monks, choose voluntary poverty, and this was also the case with some in the hippie counterculture of the late 1960s.

Lifestyle is also linked to values. An authentic lifestyle reflects your values; an inauthentic lifestyle probably conflicts with your values, or perhaps reflects the values you actually hold rather than the values you profess.

Before the hippies came the beats, who didn't speak of lifestyle, though they knew what it was. Their term for what the hippies called "straight" society was "square", and as Lawrence Lipton put it in his book The Holy Barbarians (Lipton 1959:150):

The New Poverty is the disaffiliate’s answer to the New Prosperity. It is important to make a living. It is even more important to make a life. Poverty. The very word is taboo in a society where success is equated with virtue and poverty is a sin. Yet it has an honourable ancestry. St. Francis of Assisi revered poverty as his bride, with holy fervor and pious rapture. The poverty of the disaffiliate is not to be confused with the poverty of indigence, intemperance, improvidence or failure. It is simply that the goods and services he has to offer are not valued at a high price in our society. As one beat generation writer said to the square who offered him an advertising job: ‘I’ll scrub your floors and carry out your slops to make a living, but I will not lie for you, pimp for you, stool for you or rat for you.’ It is not the poverty of the ill-tempered and embittered, those who wooed the bitch goddess Success with panting breath and came away rebuffed. It is an independent, voluntary poverty.But for more on that see here: It's Cool to be Hip, but not Hip to be Cool.

July 15, 2024

A Gentleman in Moscow -- the mind and face of Bolshevism

A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles

A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor TowlesMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

The best book I've read so far this year.

Count Alexander Rostov is sentenced by the Bolsheviks to indefinite house arrest in the Hotel Metropole in Moscow's theatre district. He becomes head waiter of the hotel, with friends among the staff and some of the regular guests, including an actress and a nine-year-old girl who has acquired a master key to all the hotel rooms, and shows him all the secret places. His life is so bound up with the hotel that it almost becomes a character in the story.

Through the life of the hotel Count Rostov (and the reader) learn of the changes of Soviet society. Once, many years ago, I read a book called The Mind and Face of Bolshevism and this book reminded me of that one at several points, in that it actually gives one a fairly good picture of Soviet life during that period. The Mind and Face of Bolshevism must be a fairly rare book. The copy I read was at the library of the KwaNzimela Centre in Zululand, but when we visited it in 2012 about three-quarters of the books had disappeared from the library, including that one.

It is also a book to savour, like a good wine. I found I only wanted to read a chapter, or sometimes a scene or two, and think about them before reading on, so I interspersed my reading of it with several other books. One needs to pause after each scene to think about it.

View all my reviews

July 4, 2024

The Dictionary of Lost Words -- and lost printing technology

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Esmé Nicoll's widowed father was an assistant to James Murray, the editor of the first Oxford Dictionary, and because her mother was dead, she accompanied her father to the Scriptorium, the shed in the Murrays' garden, where the work of compiling the dictionary was carried on. While they sorted the slips of paper with the entries, many sent in by volunteers, five-year-old Esmé sat quietly under the table, noting the shoes and socks worn by the editorial assistants.

One day one of the slips falls from the table, and when no one bends down to retrieve it, Esmé puts it in her pocket, and later hides it away in an old trunk belonging to Lizzie Lester, the Murrays' housemaid, who is only a few years older than Esmé herself. So Esmé becomes a collector of lost words, words that are discarded from the dictionary, words that are lost inadvertently, and a few that she pilfers from the sorting table. When her pilfering ways are discovered, she is banished for a while from the Scriptorium, but her interest in words continues and as she grows older she begins collect them on her own account.

She also becomes aware that the all-male lexicographers are not aware of, or not interested in words that are used only by women, or words that are spoken by the common people rather than by the educated classes, and so becomes aware of social inequalities in late-Victorian and Edwardian England.

The Dictionary of Lost Words is only semi-fictional. Not for Pip Williams the usual disclaimer that none of the characters bear any resemblance to any actual person, living or dead. James Murray and most of the other editorial assistants, including members of Murray's family, are the real people, and they appear in a photograph at the end of the book. Of course their conversations are imagined, but some of the things they say are taken from their own writings, or contemporary reports and memoranda. One can learn quite a lot of the way in which the Oxford Dictionary was compiled from the book.

I really enjoyed reading it, not just because, having worked as a proof reader and editor at various times, I have an interest in words and how they are used, but also because Esmé and the other characters, fictional or otherwise, come across as real people, so that one shares their joys and sorrows, and cares about what happens to them.

The book also sparked lots of memories for me, which don't belong in a GoodReads review, as they go beyond the merits of the book itself, but I'll share some of them here.

Esmé visits the Bodleian Library, and the Oxford University Press, where she becomes friendly with one of the compositors, and describes the work of the compositor in setting up the page for printing. And that recalled to me my time as a proof reader on the Windhoek Advertiser in the early 1970s, which was the end of the hot-metal type printing era.

When I began working as a proof reader I sat at a table in the works near the typesetters, who were mostly German-speaking, and worked on Intertype machines which set each line of type in hot lead. The lines were collected in "galleys", and once they had finished the story they would bring me a galley proof, which I would correct, not merely as a proof reader, following copy, but also as a line editor, checking for errors of fact, grammar and spelling. These would go back to the typesetters, who would set the corrections, often with much swearing.The galleys would then go to the sub-editor and the compositor, who fitted them into the page, sometimes shortening the story to fit, and added the headlines. Once the page was set up, the page proof would come back to me for final corrections -- the most common mistake being transposed or missing lines. Then paper maché clichés or stereotypes would be made from the set page, from which the moulded lead plates would be made for the rotary press. All this was a much longer process than the book printing described in The Dictionary of Lost Words, where the compositor appears to have done the typesetting as well.

When I began working as a proof reader I sat at a table in the works near the typesetters, who were mostly German-speaking, and worked on Intertype machines which set each line of type in hot lead. The lines were collected in "galleys", and once they had finished the story they would bring me a galley proof, which I would correct, not merely as a proof reader, following copy, but also as a line editor, checking for errors of fact, grammar and spelling. These would go back to the typesetters, who would set the corrections, often with much swearing.The galleys would then go to the sub-editor and the compositor, who fitted them into the page, sometimes shortening the story to fit, and added the headlines. Once the page was set up, the page proof would come back to me for final corrections -- the most common mistake being transposed or missing lines. Then paper maché clichés or stereotypes would be made from the set page, from which the moulded lead plates would be made for the rotary press. All this was a much longer process than the book printing described in The Dictionary of Lost Words, where the compositor appears to have done the typesetting as well.While I was at the Windhoek Advertiser however, electronic typesetting was introduced. A typist in the newsroom would type the story on a machine that produced a punched paper tape, which was then fed into an attachment on the Intertype machines, and the skilled typesetters became mere machine minders. They fed the paper tape into the machine and watched it work. The only time they touched the keyboard was to set the corrections.

Then I moved to Durban, and my wife Val had a cousin who married a compositor on The Daily News. He had just completed a five-year apprenticeship, and was almost immediately made redundant when the newspaper switched from hot-metal printing to offset litho. The job of compositor, as described in The Dictionary of Lost Words, had ceased to exist.

I read an article in the same Daily News about the journalist's experience with the new Atex computerised typesetting system. The journalist would compose the article on the machine, polishing and correcting it as it went. The sub-editor would read it on the same machine, edit, cut it and write the headline, and it would then go to the people who did page makeup, all marked by codes on the same machine. I wanted one. That was in about 1974, fifty years ago. I dreamed of having a machine that could store whatever text I wrote, and could correct and change without retyping.

Twelve years later I got my wish. I went to work in the Editorial Department of the University of South Africa in 1986, editing academic texts on their Atex system. It was not as exciting as I thought it would be, though, because by then I already had an Osborne portable (well, luggable) microcomputer and could use the Wordstar word processor. The Atex system was clunky by comparison. If you wanted to save a document you were working on, you could walk to the canteen and have a cup of coffee and a chat while waiting for it to return to the screen.

The following year, however, we got microcomputers, where the Atex system had been ported in a new word processing program called XyWrite, which was much faster, and, for sheer word-processing power, has still not been surpassed 35 years later. It may lack the bells and whistles of the latest word processors, but still has more pistons and cylinders, and the whole thing fitted on a 360K floppy disk.

All these memories, and many others, came back while reading The Dictionary of Lost Words. I thought the book was very good indeed, but perhaps that's just me, because of my experience with words and meanings and putting them into books. But I still think it's worth five stars.

June 28, 2024

The Drunken Silenus

The Drunken Silenus: On Gods, Goats, and the Cracks in Reality by Morgan Meis

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This book is an extended personal meditation on Peter Paul Rubens's painting of the drunken Silenus.

Silenus was the tutor of Dionysus (whom the Romans called Bacchus), the dying and rising Graeco-Roman god of wine. Silenus was also the leader of the Satyrs, the half-human, half-goat companions of Dionysus. Silenus is shown as a fat old man, and, in contrast to his companions, his drunkenness is not the drunkenness of frenzied excess; in Rubens's painting it is the semi-conscious stumbling drunkenness of one who drinks to forget.

What made me want to read this book in the first place was the appearance of Silenus, Dionysus and their retinue in C.S. Lewis's children's novel Prince Caspian. And while this book doesn't explain it, it certainly gives more of the background.

Morgan Meis takes us on a journey, starting with the life and times of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), going back to ancient Greece, when the cult of Dionysus flourished, and forward to the time of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) who had his own view of Silenus, whom he regarded as the father of Greek tragedy.

Meis examines the significance of Silenus against the historical background of each of these periods with an intertwining of history, biography, art history, philosophy and religion, with a great deal of personal speculation thrown in. None of these is treated in a formal academic way; there are no footnotes or other references, though there is a short bibliography at the end. But this broad, comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach does present Silenus, and Rubens himself, in a more holistic way than, say, a purely art-historical approach would do. The only fault I could find with this approach is that at times Meis tends to become too verbose and repetitious.

I found the book stimulating. It stimulates an interest in all these topics. One does not necessarily have to accept all Meis's speculations, but one can treat them as a starting point for one's own. Rubens painted the drunken Silenus at the beginning of the Thirty Years' War, and the book would be interesting to anyone interested in that period, or art of that period.

One regret is that I could not find a decent reproduction of the painting online, and none is included in the book. The ones I could find online lacked the detail that is described in the book, and a full-colour reproduction would have been a useful additions.

In addition to being tutor to Dionysus, Silenus was a philosopher and a prophet, and when the legendary King Midas asked him what was the best thing for man, Silenus answered that the best thing for man was never to have been born, and the next best thing, having been born, was to die.

That's a pretty pessimistic outlook on life, and makes me wonder, even more, why C.S. Lewis would include him in a book written for children, even though he doesn't mention that side of Silenus. According to Meis, however, Nietzsche liked it:

The Greeks, Nietzsche thinks, the ancient Greeks— the Greeks of the satyr plays and the music in the forest, the Greeks who came before the classical period of Plato and the brilliant days of Greek rationalism, the Greeks before that, the ones who danced the Sicinnis dance and celebrated their secret rites—those Greeks were bold enough to make a health of their pessimism. They were strong, thought Nietzsche, tremendous in their ability to think that pessimism all the way through. Nay, to live that pessimism all the way through. That’s the way Nietzsche thought about it.

For Meis, the tragedy of Silenus is that he is immortal without being fully divine; he cannot die although at times he longs to do so. This is reminiscent of Tolkien's elves, for whom death is "the gift of Illuvatar", for which they envy men.

Faced with such a fate, it is perhaps unsurprising that Silenus should seek refuge in liquor. Again, as Meis puts it:

Silenus is, after all, somewhere between dying and not dying. He is not fully immortal like Dionysus, he isn’t a true god, nor is he fully mortal like King Midas, since he must always exist in order to be the attendant of Dionysus as Dionysus is perennially born and then torn apart and then reborn and then torn apart again. And Silenus is also, we should mention again, extremely drunk in the painting. And one of the key aspects of being verydrunk, as everyone knows, is that you are conscious without being all the way conscious. You are there without being all the way there. You are present while at the same being absent. You are moving around without going anywhere.For C.S. Lewis, however, even Dionysus, though a god, is not the True God. He is a creature, created, not begotten, and it is only in Christ that both Dionysus and Silenus find true fulfilment. In Prince Caspian Silenus is still tipsy, and still falls off his donkey, but it is the tipsiness of revelling rather than the drunkenness of oblivion.

View all my reviews

June 8, 2024

The Color Purple (Book Review)

The Color Purple by Alice Walker

The Color Purple by Alice WalkerMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

An epistolary novel.

It's set in the southern USA in the 1930s & 1940s. and is about the life of a poor black family there.

Celie is raped by her stepfather and has a couple of children who disappear. She is then more or less forced to marry a man, Albert ____, who doesn't love her and treats her badly. Celie is gay and doesn't love him. Initially the story is told in a series of letters she writes to God.

Celie's sister Nettie goes to Africa as an au pair with a couple of missionaries and their adopted children, and writes to Celie, with descriptions of what is happening in the place where they live. This, for me was the best part of the book, reminiscent, in a way, of The Poisonwood Bible. It describes how an overseas rubber plantation company dispossesses the local people, forcing them to move off their land, and destroys their way of life -- "expropriation without compensation" is the latest political buzz-phrase for that kind of thing. Though the book is set in the 1930s and 1940s, it is the kind of thing that could still happen in South Africa 80 years on.

Celie, however, doesn't at first receive her sister's letter, because her husband hides them, but nevertheless switches from writing to God to writing to her sister. Celie eventually leaves her husband, finds someone who loves her, and starts a business, but things go wrong again.

In many ways it is a very sad book, all about people's messed up relationships, and how they manage to cope with them. I also found it quite a complex book, and had to read the first few chapters again when I was halfway through, just to keep track of the characters' relationships.

View all my reviews

May 8, 2024

Travelling through southern Africa in the 19th & 21st Centuries

Footing with Sir Richard's Ghost by Patricia Glyn

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Patricia Glyn, having heard about the travels of her great grand uncle Sir Richard Glyn, decides to walk the trail of his 19th-century journey from Durban to the Victoria Falls. This is the diary of her journey, with excerpts from his diary, and notes on the places they passed through, and historical events that had taken place there.

Sir Richard Glyn and his English companion were that comparatively rare species of traveller, the British "sportsman", who came to Africa primarily to hunt animals for sport, and left with their trophies. Though comparatively rare, however, unlike most other travellers they kept comparatively good written records in the form of diaries, and so their travels are better documented than most.

The book was a toss-out from the Alkantrant Library, probably a donation from a deceased estate. I hope the reason that the library tossed it out was that they already had a copy, and not just that they didn't think they needed one because it would be a pity if this book were not available. Just as her relative's diary is a valuable account of how people travelled and lived in the 1860s, so hers is a record of how people travelled and lived in the same parts of the world in the early 21st century.

In the 1860s the travellers relied of paid local guides, accounts of other travellers, or local advice or knowledge. In the 21st century this was supplemented by cell- and satellite phones and more accurate maps.

One of the reasons I found it interesting was that in 2013 my wife Val and I went on a similar journey, following in the footsteps of her great-great-grandfather Fred Green, who travelled through much of the same region, and also that to the west, from the 1850s until his death in 1870. Unlike the Glyns, he was not a sportsman, but a professional hunter, trader and explorers, his main source of income being ivory for which he hunted and traded. Unlike Patricia Glyn, however, we did not walk, but drove by car, taking three weeks instead of five months.

The book is illustrated with photos and maps, and has side panels with historical and geographical notes drawn from a variety of sources, which are all listed in the copious bibliography.

View all my reviews

April 10, 2024

Rites of Spring

Rites of Spring by Anders de la Motte

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

A Scandinavian whodunit with a difference -- the protagonist isn't a boozy detective drinking himself to divorce and death.

Instead the protagonist is a doctor, Thea Lind, who goes to the small town in southern Sweden where her husband David had grown up. He goes back to start a restaurant, while Thea starts working at the local clinic. She soon discovers that there is a secret in the village that affects her husband David, something that happened on Walpurgis Night several years before. She gradually learns that the events back then had affected her husband when he was a child, and a young girl had been killed in a ceremony to mark the night.

The story moves back and forth between past and present, in a manner reminiscent of the books of Robert Goddard, and the past events are written in the past tense, which those in the story present are written in the present tense.

St Walpurgis Night (strictly St Walburga's Eve) is celebrated in Sweden and several other northern European countries to celebrate the canonisation of St Walburga, an 8th-century English missionary nun who worked in Germany. It took place on the night of 30 April, and her feast day was 1 May, which also marked the beginning of summer in Sweden.

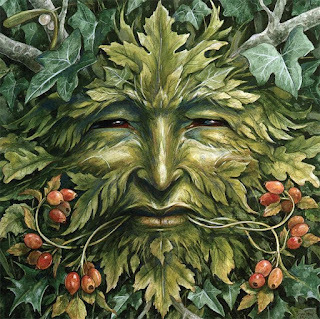

In the story some elements of English folklore have also been incorporated into the celebration, including the Green Man. The "green man" folklore has grown up around the foliate heads that appear in the decoration of churches in various parts of Europe, and in the story the Green Man is treated as a person who appeared on St Walpurgis Night, and the girl who was killed was enacting a rite of sacrifice to the Green Man.

The more Thea discovers about those past events, the more opposition she encounters from those who want to keep the secret, but Thea has secrets in her own past as well.

It's a gripping story and well written.

It also interested me in ways that go beyond this particular story, and that is the incorporation of motifs from folklore into the story, even quite recent folklore, such as that of the Green Man. I like writing such stories myself, and so I find it interesting to see how other writers do it.

The "Green Man" legend goes back about 85 years or so, and was originally applied to the names of pubs, which was then linked to the foliate heads found in churches, and a quite extensive folklore has developed around the linked symbols.

The "Green Man" legend goes back about 85 years or so, and was originally applied to the names of pubs, which was then linked to the foliate heads found in churches, and a quite extensive folklore has developed around the linked symbols. The legend has been used and developed in several novels. I recently reviewed another novel, Wildwood, that also incorporated it. That was a so-called "young adult" (teenage) story, and each such story adds to the legend. A Facebook friend, who was a fellow student at university with me, recently posted an interesting article on Facebook linking it to the Arthurian story of the Green Knight and the Green Chapel.

While I haven't used this particular story in books I've written, one of my children's stories, The Enchanted Grove, incorporates creatures from Zulu folklore, while another, Cross Purposes has them from Russian and Mongolian folklore.

Rites of Spring doesn't incorporate anything from the life of St Walburga, but I looked it up anyway, and found that German Christians asked her to protect them from various diseases and witchcraft. That didn't seem to form any part of the Swedish celebrations, but then neither, apart from in this story, did the Green Man.