Mette Ivie Harrison's Blog, page 10

February 25, 2015

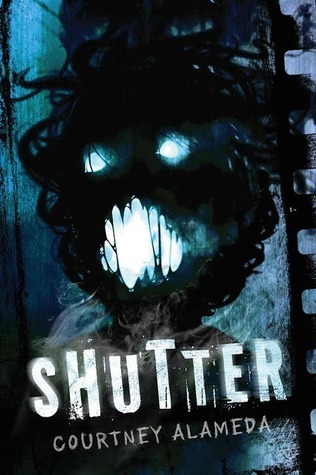

Reviews of Razorhurst and Shutter

Razorhurst by Justine Larbelestier is a murder mystery set in 1930s Sydney Australia with a paranormal bent. The two adhoc investigators of the murder are a girl and a woman with the ability to see the ghosts of the dead, including the dead man who was killed who keeps telling them who he thinks did it. Only problem with this is that the dead are confused about their own lives and have weird motives with regard to how the future moves forward without them.

One of the most intriguing features of this book is the omniscient voice. Omniscient used to be the standard method of storytelling back in the 1800s, but it has fallen out of vogue. I've never actually used it myself. It has always felt like it would take away too much from the close pov that I like to use. Au contraire! The master Justine Larbelestier here uses omniscient brilliantly. Short little chapters from different points of view are interspersed with slightly longer chapters from the povs of the two main characters, Dymphna and Kelpie (love those names, BTW). I never felt like I wasn't close to either Dymphna or Kelpie, and I never felt like the short intersped chapters made me lose interest in the main forward movement of the story. But they did make me feel like I understood a wider picture of the time period and culture, and of particular other characters before moving on. I am definitely going to try this technique sometime in the future if I find a book or story that would lend itself well.

And in case you're wondering, hell yeah, I recommend this book. I love the time period, which I've never really seen done in Australia. The research is meticulous. I loved the focus on women and women's power and vulnerability. I loved Kelpie's insistence on getting away from welfare. I loved how deeply immersed I was in the whole book, but particularly in Kelpie and Dymphna's goals.

.

Shutter by Courtney Alameda is a horror with an interesting supernatural twist. The protagonist, Micheline Helsing, is a descendant of THE Van Helsing and it's her job to use her special eyesight to take photographs of the dead that send them back where they belong. Only she comes across a ghost so powerful and so different than none of her usual tricks work against it. And the ghost is targeting her own friends and family members to kill.

When I read books these days, I always read as a fellow author. That means I am looking at the craft and the story-telling. And I'm always trying to learn something from other authors. Well, to be honest, that means I'm trying to steal things for use in my own stories. What will I be stealing from Courtney? I felt like her use of language was just superb. For example:

"I followed Damian out into an anemic, waning night. Spindly trees lined the wide avenue, shedding the gangrenous leaves of fall. The world smelled terminal, waiting for winter and rot. October in San Francisco was usually warm, but this year, fog frothed over the peninsula, carried by a chilly wind. I crossed my arms over my chest, hugging my camera and belt." (62)

I felt like I was getting all my senses pinged here. She mixed description with emotion and vivid texture. I loved how every word throbs with meaning. And this is just one paragraph. The whole book is filled with quotable bits and pieces, in addition to a great plot and interesting characters. I, for one, did not see the big plot twist near the end and I was glad I hadn't, because it made me care that

much more about Micheline. I'm not usually much of a horror fan and I don't really care for vampire lore per se, so I don't feel like I was primed to love this book, but love it I did. Hopefully you'll see some of Courtney's influence in my later books!

Oh, and just for the sake of it, I'm linking here to a nasty review of the book, which cited multiple examples of the very passages I loved as things that he hated. Is there some misogyny latent in the review? Well, I'll let you make your own judgment of that. But as for me, I doubt this guy would have said anything like this if he hadn't been a man and Courtney hadn't been a woman writing about a woman.

http://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1061782052?book_show_action=false&page=1

February 23, 2015

What is Plot

Plot is actually all the things that happen along the way from point A to point B (or at least in the beginning, when that’s where the protagonist still thinks she is headed). It’s more like the story of what happened when someone was headed from point A to point B and then ended up veering off toward point C, then point D, E, and F, and then headed back to point A. Or something like that.

I don’t mean to suggest that there is only one plot, of course. There isn’t. That’s part of the problem. If you as a writer love one particular book or movie so much that you are trying to duplicate it too closely, everyone will see that and your version won’t feel original. There’s nothing wrong with being inspired by someone else’s art, but you have to make it your own, and that means taking it off in other directions than from where it went. It means inventing a new plot for it.

Another way of thinking of plot is thinking of it as the mistakes the characters make as they are trying to go from point A to point B. It might turn out that point B is where the story ends, after all. That’s fine. But what makes your story unique and interesting is how the characters get there. And where the detours are along the way.

Sure, there are plenty of stories where it feels like the author didn’t care about putting in any plot at all, and maybe you want to avoid that. The best strategy for that is to make sure that your characters always think that they know where they are headed, and are doing their best to get there. But they are flawed and so end up failing over and over again (classic try-fail cycle here).

In a novel, your readers are less interested in going on a successful journey with your characters where at the end they feel like they have achieved something notable, and more interested in experiencing something like a real journey themselves. Readers want it to feel like it takes time to make a journey. They want to feel like it was hard to get to the destination. They want to feel like they learned something along the way that they didn’t know before. And that’s why your character is going to spend plenty of time learning things and making mistakes along the way. Because readers don’t actually want to read about a character who already knows everything necessary to make the trip from point A to point B without any interruptions.

And besides, that won’t be a novel anyway. It won’t even be a short story. Just a boring, one paragraph summary.

February 20, 2015

A Good Agent is Worth Ten Times 15%

Obviously, a literary agent is not a lawyer. You don’t pay an agent to settle out of court, to prep you for a court date. But a good literary agent will keep you out of court, and that’s worth a lot to me in terms of anxiety spiraling out of control.

A good agent, in my experience, doesn’t just sell your work. They create opportunities you never knew existed. They sell work you haven’t written or even conceived of yet. They help you see yourself and your ability to write in completely new ways.

And that’s not even talking about how a good agent can act as a cheerleader, a networking partner, a collaborator on marketing, and on and on. Seriously, if you ever as an author consider cutting ties with a good agent because it costs too much, I will think you are crazy. Don’t settle for a bad agent. That’s not what I’m saying. Bad agents can be worse than not having an agent. If that’s the only experience you’ve had, then I would gently suggest that yes, you’re right to fire that agent. But that doesn’t mean that every agent it like that. You just didn’t have a good one if you didn’t see all the other benefits that come with having an agent. Keep looking.

February 19, 2015

Life Block vs. Writers Block

If you are stuck in your manuscript and you don’t know where the story goes next, I always say that you should go back to the beginning because most likely you have gone off the rails somewhere and once you figure out where that is, you won’t have any problem writing. But you do have to be willing to throw out all of the pages you wrote after that point. Alternatively, I sometimes think that writers start a project that they don’t love and it can be almost impossible to keep writing in that state. If this is your problem, I would say you need to work on something else, not that you have Writer’s Block and can’t write anything.

But if you have Life Block, this is more serious. Life Block can’t be solved by rereading the manuscript because it isn’t about the manuscript at all. There are some writers who honestly go deeper into their writing and do better when they are dealing with horrible life circumstances, but I think there are very few of them. If you are dealing with the loss of a loved one, with a terrible diagnosis, with simply too many demands from people you could not in good conscience say no to, then I would say you have Life Block. The answer to problems with Life Block is to deal with life, not with writing.

If you desperately need to write a few lines a day to keep sane, then do that. But do it without expectations and without recriminations. There is nothing bad about you if you let go of writing for a while to deal with real life problems. Yes, some people get more of these than others. Yes, it is completely unfair. No, I have no idea why this happens. I’m planning some long conversations with God in the after-life about this.

My point is, don’t call Life Block Writer’s Block because it will make you insane thinking that you should just keep plowing forward no matter how impossible it is. A friend of mine was dealing with a flood in her house and a deadline and she was going crazy. This is Life Block. The answer is you call up your editor and say you need a deadline extension. If you end up being on bed rest during a pregnancy, or if your mother is diagnosed with breast cancer and moves in with you, or your child is going through depression, writing will necessarily take second place to these other problems.

Yes, you can try to keep working through them. I know that writing is a job to some people and real life problems do not mean that everyone can take time off. But the reality of writing as a profession is that you can’t phone it in the way I think that people in other jobs can. You can’t just go on autopilot. You need your full heart and mind in it to get the work done, and I don’t think you can do that when your heart and mind are given fully to something else.February 18, 2015

A Generous Moderator

This year, as a moderator myself and as someone moderated by others, I have been pondering the importance of generosity and flexibility in a moderator. Preparation seems an obvious good trait in a moderator. It’s good if the moderator remembers to write some questions down ahead of time, even better if she remembers to send them out to the people on the panel. Reading books of people on the panel so you know where they’re coming from is a third step that can be really useful, but takes a lot of time. I think this ends up helping with a lot of the misunderstanding that can happen on panels if the participants don’t know each other and make assumptions about experience or inexperience.

Flexibility and generosity are different from preparation, however, and I’m not sure how easily these skills are taught. I think Ellen Degeneres is a great talk show host because she has both of these qualities. You know when you go on her show that if she makes fun of you, it will be gently and kindly. You know that if you do something out of the blue, she will be able to roll with it, and won’t be stuck looking at her list of questions with her mouth wide open. Think of Ellen when you imagine a really good moderator.

A generous moderator will allow another member of the panel to ask a question if it works within the board guidelines of the panel. A generous moderator can rephrase questions from the audience in such a way that they are easier to answer and make more sense. A generous moderator compliments all of the panelists for their answers and feels no need to make insignificant corrections.

A flexible moderator can go with the flow and throw out all of the questions she painstakingly wrote down weeks before. A flexible moderator can figure out what to do when someone on the panel has been put on the panel for the wrong reason or is suffering some kind of mental breakdown on the panel itself. A flexible moderator can feel the audience’s response to certain comments, and steer the panel in a direction that the audience is more interested in than perhaps what was expected. A flexible moderator knows when someone has hit the motherlode in an answer and can let everyone else catch their breath as they process this response.

February 17, 2015

Sympathetic Characters

Just a quick list of ways you can get your audience to sympathize with characters:

1.Pity

2. Humor

3. Universality

4. Envy

5. Passion

6. Beauty

7. Competence

8. Passion

9. Goodness

A lot of the time writers focus on #3 or #9 a lot, trying to create characters who are easy to sympathize with because they have small foibles that are universal and because they have deep goodness. But you can have seriously messed up characters who readers love and root for without either of those traits.

(#4 Envy refers to the phenomenon of reading about characters who are often despicable but live "big" lives with money, fame, or in exotic locales that readers envy. Similarly, #6 Beauty is why so many romance writers try to establish their characters as beautiful to begin with so that we want to watch what they do.)February 11, 2015

How Authors Get Paid

I am surprised sometimes at how mysterious it seems to those outside of the publishing world how authors get paid. But maybe if I weren’t in this world myself, I wouldn’t understand it, either. To the basics:

1. Authors Get Paid Royalties. This means that they get a percentage of books sold new. Not checkouts from libraries (in America). Not reused books.

2. Authors Get Paid Advances on Royalties. Sometimes. This means that the publisher estimates how many copies will sell, and pays the author this much money up front.

3. Authors Get Paid for Appearances, etc. If you pay them and if you invite them. Authors you do not invite for school visits or appearance do not get paid. Authors who come for free do not get paid.

4. Authors Get Paid for Movie Rights or Other Subsidiary Rights. Sometimes even if movies do not get made, authors get money. But for the vast majority of authors, these rights do not exist.

5. Authors Get Paid for Translation Rights. If the translation is done by a legitimate publisher that bothers to pay them.

This all sounds perfectly obvious, right? But a lot of people I talk to think that authors get paid a lot more than they actually get paid. This is partly because of a wide variety of misconceptions, such as:

1. Publishers Pay Authors just for being authors. This doesn’t happen. If books aren’t being sold, authors are not being paid. No authors get paid for sitting around being authorly.

2. Authors are selling lots and lots of books, a hundred thousand or more. No. Most authors are lucky if they sell about 5,000 copies of a book.

3. The percentage of cover price an author makes on a book is a lot lower than you think. Ten percent is good for most contracts. And there are a lot of exceptions. Books given away for free in promotions don’t count, etc.

4. Me personally getting a pirated book for free won’t hurt anyone. The publishing world is becoming more like the music world, where the artists who make money are the ones who tour and charge for live appearances. I don’t think this is a good thing.

5. Authors who splash in the news for big advances are making less than you think. An author who sells a three book deal for $1 million is probably making less than an accountant. This is because that deal is divided into chunks over years, some of it may never happen, and there are a lot of expenses involved in being an author at that level, including traveling expenses, assistants, publicity people, and an agent—which comes directly out of the author’s pocket. Not to mention health insurance costs (insuring yourself is a nightmare and expensive, even now). And self-employment taxes, which no one but the self-employed really understand, and which is why most people try to avoid being self-employed like the plague. You pay 40% in the lowest tax bracket for self-employment tax.

6. Authors who get big reviews or are subjects of newspaper/internet articles are not paid for this. (In fact, it may sometimes be the reverse.)

Look, I don’t think ebook piracy is going away anytime soon. I don’t think being vigilant on my part is going to help. I doubt my telling you to stop doing it is going to be more than a drop in the bucket. I’ve given up on that point.

But it’s useful for people outside of the publishing world to understand how authors get paid so that they don’t think it is some magical thing that happens that they don’t have to think about. This isn’t about guilt. It’s about informing you so you can see the truth more clearly.

Authors get paid by the books they sell. Pure and simple. This is why authors often turn down opportunities to appear at events where they can promote their books but aren’t being paid anything. Child care costs alone can be prohibitive. Authors whose books you buy remaindered at B&N aren’t getting paid for them. It’s sad, but true. Authors whose books you buy on a big promo aren’t (often) getting paid for them, either. I’m not saying it’s bad for them, but it’s not the same thing as money.

Authors are often shy people, not used to publicity and attention. It’s weird, then, that for many of us, the only way to make a living is to become a celebrity and charge for personal appearances. I don’t like it, but I think it’s a reality that authors are having to start to face as the industry changes.

February 10, 2015

Your Next Book

The book you choose to write and to spend the next year or two—or more—writing, is a reflection of who you are and who you want to be. It’s like listening to a young child ask parents what she should be when she grows up. It’s a game, and it’s funny, unless the kid is 25 and is still asking around for help. No one knows who you are better than you do.

Now, I admit, there are times when people can steer you in the right direction. And sometimes when it’s just as useful that they steer you in the wrong direction because it’s immediately obvious how wrong that direction is. Sometimes other people see how we are trying to deceive ourselves. You listen to a writer talk about how her next book is going to be science fiction and yet she is obsessed with music. You listen to a writer talk about writing a historical novel when she spends all her time talking about the last romance novel she read and exactly what was wrong with it.

But ultimately, you are the boss. And sometimes the hardest part of being a grown up is that you are the boss, you and no one else. You are going to have to decide what kind of writer you are. Are you a writer who writes series? Do you write in the same genre all the time? Do you change genres every time you pick up a keyboard? Do you have a theme that you continue to hit on, consciously or not, in every book you write? Do you have a style that sets you apart? A language? A rhythm? A kind of description or worldbuilding?

You decide this as you write book after book, and you do not always decide it consciously, I admit. But nonetheless, you create yourself with your words. So when you ask if this book or that one is the one that you should work on next, the only way people can find out the answer is to reflect the question back at you and ask which you want to work on the most? If you don’t know the answer, then it’s probably neither of them. You may not have found what the right book is yet. I know that’s not what you want to hear, but there it is.

And sometimes (a lot more often than we want to hear), you end up writing a book that is the wrong one. And you sit and look at it for a long time, and you think about how close it is to the right one. You wonder about whether or not you can change it into the right one, because you’re good at editing, right? But no amount of fixing is going to change the wrong book into the right one. You are probably going to have to start all over.

I don’t know about you, but I’m afraid that adulthood is mostly about accepting that you made the wrong choice, that it feels like you wasted a bunch of time, and then stopping complaining, and getting back to work. Being an adult writer means that you spend a little bit of time telling yourself that you needed to make the wrong choice to get to the right one, so it’s not really wasted. And then you quit talking about it because it doesn’t matter and you’re busy, DAMMIT!

February 9, 2015

Drafting and Editing

I’m not trying to convert anyone to my way of creating, but if you are like me, you may find it easiest to write sloppily, messily, quickly, and as unconsciously as possible. Sometimes my sloppy first drafts are brilliant, just as they are (rarely). Most of the time, there are brilliant pieces of my sloppy first drafts which I save and then add to, draft by draft, until all the parts fit together and are equally good. Sometimes, my sloppy first drafts are wretched all around and need to be either thrown out completely or reconsidered so thoroughly that it is almost the same thing.

If you work best this way, you need to figure out a way to disengage the critical part of your mind while creating. The critical faculty will be of enormous use later on. It’s just not going to help you while drafting. The critical part is mainly going to tell you one of the following:

1. I’ve seen this before in x, y, and z. This thought is not an original one. And in fact, this treatment is not an original one, either.

2. Those words are a very pedestrian way to get at that expression.

3. This whole section needs to be cut. And this one. It’s self-indulgent twaddle.

4. This character is so boring. Blah, blah, blah. Get to the interesting part!

5. This plot makes no sense at all. No real person would do that! The pieces are connected in the most arcane possible way.

6. Too much explaining. Also, too many new words that make no sense.

7. Are you trying to offend everyone on the planet?

8. Don’t you have anything deep to offer in your theme? Is this just a meaningless series of events?

Basically, the critical impulse is a replay of all the bad reviews you’ve ever read or written, about your book or anyone else’s.

The critical impulse isn’t necessarily there to stop you from writing, but for me, that is what the end effect is. It makes me think so hard and doubt myself so much that I can’t create new stuff while I’ve got it turned on. It’s only useful for telling me what’s wrong. But to fix what’s wrong, I still have turn off critical impulse and turn on creative impulse.

Creative impulse says one of the following:

1. Hey, try this! It’s awesome.

2. You are the most brilliant creator ever! Good for you! Isn’t this fun?

3. No one has ever said this before in quite this way.

4. You are creating something completely original. Isn’t that amazing?

5. What else can I add in to make this even more fun? How about giant spiders, monsters from outer space, and also some Jane Austen witty dialog?

6. I am this person I have created. I see the world completely from her point of view.

7. Let’s make some new rules for this world. And also, new magic. And throw in some people who break all the rules!

When I draft, I give my creative side free reign. But you must be aware as a creator that doing this is a dangerous thing. Your creative side isn’t always as brilliant as it would like to believe. So when you go back to your first draft, you must be just as eager to cut the parts that aren’t working as you are willing to write anything that pops into your head while drafting.

I sometimes cut 20k words in a day. And usually I don’t feel a twinge of pain because do you know—those words were all bad ones! I didn’t know it while writing them, and I didn’t want to know it. Writing them helped me get to the ones that were good, and I don’t regret my process.

Again, this may not be your process, but if it is, this may be helpful to think about. Now go forth and draft messily and edit judiciously!

Where Do Characters Come From?

Well, I am a conglomerate of all the people I have met and what they have said to me and what I saw them do. Add to that all the books I have read and the characters I have read about in them. Movies, television, songs, paintings, etc.

I choose to show certain aspects of myself which I have approved to the world. That means there are parts of me that I don’t show. There may be parts of me I don’t like. Those parts may or may not later came out in other events in my life. I may keep them suppressed forever.

The main difference between humans and the apes, our near-twins genetically, is the human capacity to think and reason, to act based on social expectation rather than what is expedient personally at the moment. Society is based on this. It may be good or bad, the way that social expectations form us, but it is very human.

In order to write characters well, even the most evil characters, I as a writer feel like I have to understand that character on some deep level. I have to know what sent an evil character in the direction. I should know some moment in the past when she wasn’t this character, when there was a chance for a different end. The evil character becomes evil in some combination of choice and fate, just like the good character does.

All characters are, therefore, on some level, me. And none of them are fully me, either. Because no matter how real and fully realized a character in a book is, there are only 100k words, a few hours that you get to spend with that character. There is no way that a real human is that simple.

So if you hate my characters, do you hate me? If you love my characters, do you love me? Both yes and no. I am so complex that all the novels I ever write will never encompass me. They are a hint about who I am, no more than that.

Mette Ivie Harrison's Blog

- Mette Ivie Harrison's profile

- 436 followers