Jennie Walters's Blog, page 2

December 17, 2012

Some Christmas cheer... and a super-fruity mincemeat recipe

Christmas will be low-key in our house this year but I'm at last beginning to feel the tiniest bit festive. London is looking lovely, all lit up, and I've made a batch of mincemeat, which is about a hundred times nicer than the shop-bought kind. It's very easy - you just have to allow a little time for chopping and stirring (which is no problem if you have a food processor). I don't like mixed peel, so I substitute a mixture of chopped dried cherries and apricots.

Christmas will be low-key in our house this year but I'm at last beginning to feel the tiniest bit festive. London is looking lovely, all lit up, and I've made a batch of mincemeat, which is about a hundred times nicer than the shop-bought kind. It's very easy - you just have to allow a little time for chopping and stirring (which is no problem if you have a food processor). I don't like mixed peel, so I substitute a mixture of chopped dried cherries and apricots.You will need:

2 large or 3 medium-sized cooking apples, cored but not peeled

8 oz/225 g/2 cups shredded suet (I use the light vegetarian kind)

12 oz/350g/2 heaped cups raisins

8 oz/225g/2 scant cups sultanas

8 oz/225g/2 scant cups currants

8 oz/225g/2 scant cups chopped mixed candied peel -

or the same quantity of sour dried cherries and dried apricots, chopped finely

12 oz/350g/2 heaped cups dark brown sugar

grated zest and juice of 2 oranges and 2 lemons

2 oz/50g/1/2 cup flaked almonds, smashed up a little more

4 teaspoons mixed spice

grated nutmeg

4 tablespoons brandy (optional)

5 or 6 clean jam jars

Simply chop the apples - in a food processor if you have one - and then mix them up in a large bowl with the rest of the ingredients, except for the brandy. Cover the bowl with foil and leave it for a few hours so that everything steeps together, then place in a low oven (225 F/120 C/gas 1/4) for 2 - 3 hours so the suet melts. Your kitchen will now smell wonderfully Christmassy!

Simply chop the apples - in a food processor if you have one - and then mix them up in a large bowl with the rest of the ingredients, except for the brandy. Cover the bowl with foil and leave it for a few hours so that everything steeps together, then place in a low oven (225 F/120 C/gas 1/4) for 2 - 3 hours so the suet melts. Your kitchen will now smell wonderfully Christmassy!

As the mixture cools, stir from time to time so the suet is evenly distributed. When it has cooled right down, add the brandy, then spoon into clean dry jars, cover with waxed discs and seal. Use in mincepies, as the basis for a Christmas cake, or in the wonderful Dan Lepard's apple and mincemeat pasties with brown sugar pastry. Best eaten within a few months, but I have kept jars from one Christmas to the next and it's been fine.

Happy Christmas, everyone. The end of this year seems to have been a sad one for all sorts of reasons, but here's hoping the Christmas rituals will bring some kind of comfort for anyone who's grieving, that getting together with family and friends will lighten up the darker days, and that spring doesn't seem too far away...

Published on December 17, 2012 04:51

December 10, 2012

Five favourite Edwardian memoirs

Consuelo, Duchess of MarlboroughResearching

Eugenie's Story

, which is set in 1893, I found it essential to read memoirs written by women who'd lived through those times - both for the detail the books contained and perhaps even more importantly, to get a flavour of the language. Here are five I particularly enjoyed. If you're at all interested in the Downton Abbey world, the workings of grand English country houses and the etiquette of entertaining in the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras, you should find something on this list to tickle your fancy. (I'm keeping my very favourite book till last, by the way, so stick with it.) Where editions of these books are readily available, I've added a link to the Amazon UK site.

Consuelo, Duchess of MarlboroughResearching

Eugenie's Story

, which is set in 1893, I found it essential to read memoirs written by women who'd lived through those times - both for the detail the books contained and perhaps even more importantly, to get a flavour of the language. Here are five I particularly enjoyed. If you're at all interested in the Downton Abbey world, the workings of grand English country houses and the etiquette of entertaining in the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras, you should find something on this list to tickle your fancy. (I'm keeping my very favourite book till last, by the way, so stick with it.) Where editions of these books are readily available, I've added a link to the Amazon UK site.

Blenheim PalaceFirst off we have

The Glitter and the Gold

, by the American-born Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, who was married against her will at the behest of her pushy mother, Alva, to the ninth Duke of Marlborough, so becoming mistress of Blenheim Palace at the age of nineteen. This book provides a fascinating insight into the running of one of England's largest stately homes. Division of labour, for one thing, was acutely important. Consuelo once made the mistake of asking the butler to light the fire; he told her frostily he would summon a footman, whose job this was. After luncheon, the butler would leave a basket of tins on a side table, into which it was the Duchess had to pile the leftovers for distribution among the poor. She was considered dangerously progressive for sorting the meat, vegetables and pudding into separate tins rather than following tradition by jumbling them all up together. I love all of that sort of detail. I sometimes find the Duchess's tone a little laboured and self-conscious, but who could fail to sympathize with a young girl trapped in this huge mausoleum of a house with a husband for whom she had little initial attraction and later detested. Mealtimes were a particular ordeal. 'As a rule, neither of us spoke a word. I took to knitting in desperation and the butler read detective stories in the hall.'

Blenheim PalaceFirst off we have

The Glitter and the Gold

, by the American-born Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, who was married against her will at the behest of her pushy mother, Alva, to the ninth Duke of Marlborough, so becoming mistress of Blenheim Palace at the age of nineteen. This book provides a fascinating insight into the running of one of England's largest stately homes. Division of labour, for one thing, was acutely important. Consuelo once made the mistake of asking the butler to light the fire; he told her frostily he would summon a footman, whose job this was. After luncheon, the butler would leave a basket of tins on a side table, into which it was the Duchess had to pile the leftovers for distribution among the poor. She was considered dangerously progressive for sorting the meat, vegetables and pudding into separate tins rather than following tradition by jumbling them all up together. I love all of that sort of detail. I sometimes find the Duchess's tone a little laboured and self-conscious, but who could fail to sympathize with a young girl trapped in this huge mausoleum of a house with a husband for whom she had little initial attraction and later detested. Mealtimes were a particular ordeal. 'As a rule, neither of us spoke a word. I took to knitting in desperation and the butler read detective stories in the hall.' Lucy, Lady Duff-GordonNext on the list comes Discretions and Indiscretions, by the designer Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon. 'Lucile' (her professional name) was a hugely important figure in Edwardian society, along with her sister, the romantic novelist Elinor Glin. When Lucy's first husband deserted her, she turned to dressmaking for her society friends to support herself and her daughter, and eventually built a reputation that stretched beyond Britain to France and America. She revolutionized the fashion industry, both because of her innovative designs and because of the way she displayed her clothes: on living mannequins, gorgeous girls who became stars in their own right. 'I was the first dressmaker to bring joy and romance into clothes,' she proclaims. 'I was a pioneer. I loosed upon a startled London - a London of flannel underclothes, woollen stockings and voluminous petticoats - a cascade of chiffons, of draperies as lovely as those of Ancient Greece, of softly-rounded breasts (I brought in the brassiere in opposition to the hideous corset of the time...) and draped skirts which opened to reveal slender legs.'

Lucy, Lady Duff-GordonNext on the list comes Discretions and Indiscretions, by the designer Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon. 'Lucile' (her professional name) was a hugely important figure in Edwardian society, along with her sister, the romantic novelist Elinor Glin. When Lucy's first husband deserted her, she turned to dressmaking for her society friends to support herself and her daughter, and eventually built a reputation that stretched beyond Britain to France and America. She revolutionized the fashion industry, both because of her innovative designs and because of the way she displayed her clothes: on living mannequins, gorgeous girls who became stars in their own right. 'I was the first dressmaker to bring joy and romance into clothes,' she proclaims. 'I was a pioneer. I loosed upon a startled London - a London of flannel underclothes, woollen stockings and voluminous petticoats - a cascade of chiffons, of draperies as lovely as those of Ancient Greece, of softly-rounded breasts (I brought in the brassiere in opposition to the hideous corset of the time...) and draped skirts which opened to reveal slender legs.'It was this book which brought home to me the true importance of clothes to an upper-class Edwardian girl of marriageable age - clothes which could decide her destiny - and Lady Duff Gordon's writing style influenced me enormously when I was trying to find Eugenie's 'voice'.

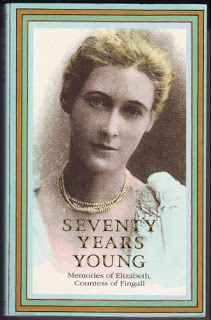

Seventy Years Young is the memoir of Elizabeth, Countess of Fingall. Her irrepressible joie de vivre shine through every sentence of this captivating account. Growing up in Ireland, she married Arthur Plunkett, the eleventh Earl of Fingall, at the age of seventeen and lived with him as chatelaine of Killeen Castle, County Meath. Apparently the earl fell in love with her at first sight, on catching a glimpse of her in a Dublin street, and who can blame him? She could clearly charm the birds out of the trees. 'The grass grew higher in Meath,' she writes of her first year of marriage, 'deepened in green colour, the trees became heavier and darker, until at last I felt that the lush growth of everything was sending me asleep. It must have been in an effort to keep awake that I used to dance by myself under the beech trees those summer evenings. "I am alive," I would cry joyously. "I am alive! And no one can take that from me!"'

As hunting was the main occupation during the winter months she had to learn to ride, which she found quite terrifying, although, 'The clothes were fun... To Busvine I went for a riding habit and much admired my own figure as I turned before the mirror while it was being fitted. No garment in the world showed off or gave away a figure like the riding habit of those days. And to Peal and Bartley for boots which must fit perfectly, not showing a wrinkle anywhere. Such bootmakers were geniuses, born not made, and Peal's genius was for the leg of a boot, Bartley's for the foot.'

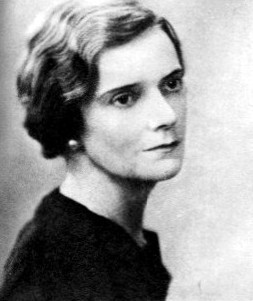

Lady Cynthia AsquithLady Cynthia Asquith, nee Charteris, is another accomplished writer. She married Herbert Asquith, the son of the British Prime Minister (who confusingly has the same name). Her mother, Lady Mary Charteris, was one of the group of intellectuals known as the 'Souls' who dominated English society for about twenty-five years from the 1880s onwards, and Cynthia - who became a novelist and friend to writers such as D H Lawrence and J M Barrie, whose secretary she was - inherited her mother's intelligence and wit. I particularly enjoyed the second volume of her memoirs, Remember and Be Glad. She recalls the complicated house parties her mother used to organize, and the sparkling conversations of their illustrious guests: H G Wells, Arthur Balfour, the academic Sir Walter Raleigh, the socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb, and many others. Besides a wonderfully entertaining account of her 'coming out', with all its arcane rules and regulations, in the chapter 'Country-house Visiting', she describes how it felt to attend a 'Friday-to-Monday' as a nervous young debutante.

Lady Cynthia AsquithLady Cynthia Asquith, nee Charteris, is another accomplished writer. She married Herbert Asquith, the son of the British Prime Minister (who confusingly has the same name). Her mother, Lady Mary Charteris, was one of the group of intellectuals known as the 'Souls' who dominated English society for about twenty-five years from the 1880s onwards, and Cynthia - who became a novelist and friend to writers such as D H Lawrence and J M Barrie, whose secretary she was - inherited her mother's intelligence and wit. I particularly enjoyed the second volume of her memoirs, Remember and Be Glad. She recalls the complicated house parties her mother used to organize, and the sparkling conversations of their illustrious guests: H G Wells, Arthur Balfour, the academic Sir Walter Raleigh, the socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb, and many others. Besides a wonderfully entertaining account of her 'coming out', with all its arcane rules and regulations, in the chapter 'Country-house Visiting', she describes how it felt to attend a 'Friday-to-Monday' as a nervous young debutante. 'I see myself being convoyed by a butler across a wide expanse of well-kept lawn to where beneath the great flat branches of a magnificent cedar, my hostess dispenses tea. Through the mists of my shyness I see the pleasing sight of honey-in-the-comb, blackberry jelly and Devonshire cream. I peer into the silver kettle at my distorted reflection to see if my nose is shiny. It is...'

We also learn the odd little fact that a post-visit thank-you letter was known as a 'Collins' (perhaps after the Collins Dictionary?) 'The prospect of having to write it darkened our whole visit. Painfully laboured rough copies left behind by mistake were sometimes found in blotting-books, and it must be admitted that certain hostesses did have the reprehensible habit of entertaining the guests of one party by reading alound unintentionally funny Collinses written by their previous guests.'

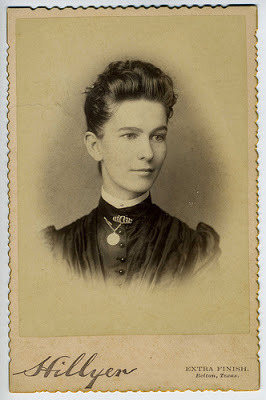

And so to my last and favourite book: Period Piece, by Gwen Raverat, grand-daughter of Charles Darwin and daughter of a strong-willed American, Maud du Puy, who arrived in England for a visit in 1882, married Darwin's second son, George, and never left. Like Cynthia Asquith, Gwen grew up in the late-Victorian/early Edwardian era, and this memoir is an account of her blissful childhood in Cambridge, and the long family visits to Down House in Kent, the home of her famous grandfather. The family lived in Newnham Grange, a large house on the river Cam. Gwen and her brothers and sister spent hours boating and swimming there alone from a very early age - her mother being convinced that her children couldn't possibly drown. The book is a complete delight. Illustrated by Gwen's own line drawings (she was an accomplished artist, later specializing in woodcuts), it captures the general spirit of the times as well as conjuring up a host of eccentric Darwin relatives.

Gwen Darwin, aged 12 'Ladies were ladies in those days,' Gwen writes; 'they did not do things themselves, they told other people what to do and how to do it. My mother would have told anybody how to do anything: the cook how to skin a rabbit, or the groom how to harness a horse; though of course she had never done, or even observed, these operations herself.'

Gwen Darwin, aged 12 'Ladies were ladies in those days,' Gwen writes; 'they did not do things themselves, they told other people what to do and how to do it. My mother would have told anybody how to do anything: the cook how to skin a rabbit, or the groom how to harness a horse; though of course she had never done, or even observed, these operations herself.'Aunt Etty is one such lady who, having no children to bring up and a maid to cater to her every whim, took up ill health as her main interest in life. 'When there were colds about, she often wore a kind of gas-mask of her own invention. It was an ordinary wire kitchen-strainer, stuffed with antiseptic cotton-wool and tied on like a snout, with elastic over her ears. In this she would receive her visitors and discuss politics in a hollow voice out of her eucalyptus-scented seclusion, oblivious of the fact that they might be struggling with fits of laughter.'

This is a book to treasure and re-read. The best way to convince anyone of its merits is probably to let the writing speak for itself, so I'll end with one last extract, an account of an ill-fated family picnic.

'It was a grey, cold, gusty day in June. The aunts sat huddled in furs in the boats, their heavy hats flapping in the wind. The uncles, in coats and cloaks and mufflers, were wretchedly uncomfortable on the hard, cramped seats, and they hardly even tried to pretend that they were not catching their deaths of cold. But it was still worse when they had to sit down to have tea on the damp, thistly grass near Grantchester Mill. There were so many miseries which we young ones had never noticed at all: nettles, ants, cow-pats. . . besides that all-penetrating wind. The tea had been put into bottles wrapped in flannels (there were no Thermos flasks then); and the climax came when it was found that it had all been sugared beforehand. This was an inexpressible calamity. They all hated sugar in their tea. Besides it was Immoral. Uncle Frank said, with extreme bitterness: ‘It’s not the sugar I mind, but the Folly of it.’ This was half a joke; but at his words the hopelessness and the hollowness of a world where everything goes wrong, came flooding over us; and we cut our losses and made all possible haste to get them home to a good fire.'

I was delighted to come across this article recently by Gwen's grandson, William Pryor, which gives an insider's view of her life and her later relationships with members of the Bloomsbury group, notably Virginia Woolf and her sister Vanessa. I have reproduced the photograph of Gwen aged 12 from this post, with many thanks. For anyone wanting to find out more about the Edwardian era and these and many other characters who defined it, I can also heartily recommend Evangeline Holland's meticulously researched and beautifully written blog, Edwardian Promenade.

So, who have I left out? What would be on your list of favourite memoirs?

Published on December 10, 2012 06:55

November 28, 2012

In which I meet Julian Fellowes, and learn some Downton Abbey secrets...

Well, my dears, the excitement! Last night I went along to the Society of Authors' offices in Drayton Gardens with my friend and fellow writer, Yang-May Ooi, to hear Julian Fellowes (who scarcely needs introducing as the man who created Downton Abbey) talk about life before and after Downton. Yang-May had had the presence of mind to bring a camera, and after the talk had finished, we boldly carved a path through the crowd of admirers to ask for a photograph. Look, here we are! It wasn't a dream!

Well, my dears, the excitement! Last night I went along to the Society of Authors' offices in Drayton Gardens with my friend and fellow writer, Yang-May Ooi, to hear Julian Fellowes (who scarcely needs introducing as the man who created Downton Abbey) talk about life before and after Downton. Yang-May had had the presence of mind to bring a camera, and after the talk had finished, we boldly carved a path through the crowd of admirers to ask for a photograph. Look, here we are! It wasn't a dream!Lord Fellowes - Baron Fellowes of West Stafford, as we should properly call him - began by saying that the breakthrough in his career had come when the director Robert Altman asked him to work on a country-house murder mystery (but 'a whocareswhodunnit, rather than a whodunnit'), set in the 1930s. This film was Gosford Park, the forerunner to Downton Abbey, which was to earn its writer an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and change his life. Before that, Julian Fellowes has described himself as 'a fifty-year-old fat balding actor', who had once waited for hours by the telephone to find out if he'd been cast as replacement dwarf in Fantasy Island. Now, post-Gosford and post-Downton, directors are beating a path to his door and he can hardly have time to breathe. A fourth series of DA has just been commissioned and there's the Christmas special to write; I read elsewhere that a series on English country houses fronted by him for ITV is in the pipeline, and that he's working with NBC on a programme about the American elite.

Success hasn't made him arrogant, however; in person, he is every bit as charming as Lord Grantham or Matthew Crawley at their most persuasive. Anyone can tell he has an actor's training: he projects his voice effortlessly to the back of the room and embarks on anecdotes with gusto. That incident when Mr Pamuk the Turk expires post-coitally in Lady Mary's bed, which some people have said stretches the bounds of credibility? Well, it really happened. The incident was inspired by the diary of an aunt of one of his friends, who related the very same thing happening along 'a corridor of women' who all realized the implications of such a scandal and dragged the corpse back to a more appropriate bedroom.

Success hasn't made him arrogant, however; in person, he is every bit as charming as Lord Grantham or Matthew Crawley at their most persuasive. Anyone can tell he has an actor's training: he projects his voice effortlessly to the back of the room and embarks on anecdotes with gusto. That incident when Mr Pamuk the Turk expires post-coitally in Lady Mary's bed, which some people have said stretches the bounds of credibility? Well, it really happened. The incident was inspired by the diary of an aunt of one of his friends, who related the very same thing happening along 'a corridor of women' who all realized the implications of such a scandal and dragged the corpse back to a more appropriate bedroom. He also told us a wonderful story about Robert Altman wanting to cut one of the best lines of all in Gosford Park (delivered by Maggie Smith, of course), in which she tells the movie producer that he needn't worry about giving away the denouement of his latest murder mystery 'because none of us will ever see it'. Apparently the very idea of anyone not wanting to watch a film was so upsetting to Mr Altman that he could hardly bear to include the line; Dame Maggie had to persuade him she could somehow 'make it work'.

So what else did we learn? His wife, Emma, is his first script-reader. She is the person who suggested making Bates the valet, lame - which raises a host of interesting questions. Why would Lord G employ a handicapped servant? What is their past history which makes the one indebted to the other? (Questions that, unless I missed a crucial moment, the series has yet to answer...) Also, he reads every word of the script out loud, which shows him the repetitions that need to be deleted and whether the dialogue will work. And as to the secret of Downton Abbey's success, he believes it is because Downton is 'inclusive'. Everyone has their story to tell, from Daisy the scullery maid to Lord G himself, and each story carries the same weight.

Goodness, I think he may be right. Added to that, the casting is great, the setting is spectacular, and if the storylines are occasionally a bit bonkers, they're deliciously so. What's not to like? My one regret is that in the time allowed for questions afterwards, I didn't ask the most pressing one of all: So what is it with O'Brien and Thomas? Why did she love him to begin with and why does she hate him now?

Goodness, I think he may be right. Added to that, the casting is great, the setting is spectacular, and if the storylines are occasionally a bit bonkers, they're deliciously so. What's not to like? My one regret is that in the time allowed for questions afterwards, I didn't ask the most pressing one of all: So what is it with O'Brien and Thomas? Why did she love him to begin with and why does she hate him now?What's the question you would have asked Lord F, had you been there? (And just so you know, he won't say anything about future plot developments...)

Published on November 28, 2012 13:12

November 19, 2012

Delicious Dower House Chutney

Clarence HouseI've been thinking about dower houses - those 'spillover' buildings where the widow of an estate-owner (the dowager) was usually dispatched on the death of her husband, to make way for the new heir. Clarence House in London was used as the dower house for Buckingham Palace when Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, moved there in 1953 after she was widowed. There's a dower house on the estate at Swallowcliffe, where Kate and Edward have been living since their marriage. When Edward's father dies, he and Kate will move into the main house and his mother will take their place in the

Clarence HouseI've been thinking about dower houses - those 'spillover' buildings where the widow of an estate-owner (the dowager) was usually dispatched on the death of her husband, to make way for the new heir. Clarence House in London was used as the dower house for Buckingham Palace when Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, moved there in 1953 after she was widowed. There's a dower house on the estate at Swallowcliffe, where Kate and Edward have been living since their marriage. When Edward's father dies, he and Kate will move into the main house and his mother will take their place in the Dower House. Somehow I feel she won't retire gracefully and make life easy for Kate when she takes over the running of the Hall.

I haven't started writing yet, or even planning in much detail, so I'm busily looking for displacement acivities and distractions. Making Dower House Chutney feels vaguely productive, especially at this time of year when plums and apples are plentiful. (I suppose the recipe name must have come from a dower house with lots of fruit trees.) This chutney will make a great Christmas present, though it needs 2 - 3 months to mature. Eat with cheese and cold meats, and add a spoonful to your gravy for a lovely fruity taste.

I haven't started writing yet, or even planning in much detail, so I'm busily looking for displacement acivities and distractions. Making Dower House Chutney feels vaguely productive, especially at this time of year when plums and apples are plentiful. (I suppose the recipe name must have come from a dower house with lots of fruit trees.) This chutney will make a great Christmas present, though it needs 2 - 3 months to mature. Eat with cheese and cold meats, and add a spoonful to your gravy for a lovely fruity taste. You need:

11/2 lb (700g) dark-skinned plums - Victoria's if you can get them

2 lb (900g) sour green cooking apples, peeled and cored

8 oz (225g) tomatoes, skinned by soaking in boiling water and coarsely chopped

8 oz (225g) onions, peeled and cut into chunks

1 lb raisins

1 lb raisins 4 oz (110g) preserved ginger in syrup

6 - 8 cloves garlic

1 1/2 tablespoons salt

1 1/2 lb (700g) demerara sugar

2 tablespoons pickling spice, tied in a square of muslin

1 pint (570 ml/3 cups) malt vinegar

A preserving pan or large saucepan

A square of muslin

8 jam jars, sterilised in warm oven

Halve and stone the plums, cut them into rough chunks and put in the pan with the roughly-chopped skinned tomatoes. Peel, core and quarter the apples and whizz them in a food processor with the onions, preserved ginger and raisins. Add these to the pan with the chopped or minced garlic, and stir in the sugar, vinegar and salt. Lastly, add the pickling spice tied up in a square of muslin.

Cook the chutney very slowly for about 1 1/2 hours. You want most of the vinegar to evaporate, so that when you draw a wooden spoon through the chutney, it doesn't immediately fill with liquid. This is about right:

Cook the chutney very slowly for about 1 1/2 hours. You want most of the vinegar to evaporate, so that when you draw a wooden spoon through the chutney, it doesn't immediately fill with liquid. This is about right: Fill the warm jars, screwing on the lids when the chutney has cooled, and leave for about 2 - 3 months for the vinegar taste to mellow.

Fill the warm jars, screwing on the lids when the chutney has cooled, and leave for about 2 - 3 months for the vinegar taste to mellow.

Published on November 19, 2012 03:36

November 7, 2012

Taking my mind - and the dog - for a walk

Brockwell Hall, the Georgian house in my local parkJust now I'm in the fallow period before starting to write my next Swallowcliffe Hall book: Lady Catherine's Story, in which Kate Vye takes over the running of the Hall when her husband Edward inherits the title on the death of his father. I find walking really productive when mulling over ideas - a combination of being out of the house in the fresh air and moving along to a rhythm, which seems to help my mind make connections as well.

Brockwell Hall, the Georgian house in my local parkJust now I'm in the fallow period before starting to write my next Swallowcliffe Hall book: Lady Catherine's Story, in which Kate Vye takes over the running of the Hall when her husband Edward inherits the title on the death of his father. I find walking really productive when mulling over ideas - a combination of being out of the house in the fresh air and moving along to a rhythm, which seems to help my mind make connections as well. I'm trying to imagine the dilemmas Kate would face, becoming mistress of a place like Swallowcliffe: her relationship with her fearsome mother-in-law, now exiled to the Dower House (maybe even refusing to go?), her dealings with the servants, who are possibly reluctant to take orders from a young American woman, the state of her marriage to a self-centred husband, used to getting his own way. Her money has saved the Hall but Edward considers it his, to use as he likes. There's also the fact that, after 6 or 7 years of marriage, they still have no children. And always in the background is Edward's charming brother, Rory. Has Kate married the wrong man? Does he still love her? Will she ever be happy with the life she has chosen? I must think about her upbringing and her American family, too: her relationship with her parents, and with her cousin, Julia, who has married an Englishman and settled in the country. Because I've written about the Vye family in various periods of history (and in fact Kate's ultimate fate is described in Isobel's Story), there are various facts that constrain me - the trick is to throw in a few surprises along the way.

From the collection of Patrick LynchI'm looking forward to getting to know Kate. Up until now, we've only seen her through other people's eyes: Polly, the servant who maids for her when she first comes to stay at the Hall in 1890; Eugenie Vye, Kate's sister-in-law, who considers her attempts to look after the tenants on the estate a waste of time and money; Grace, Polly's daughter, who works at the house during the First World War and sees Lady Vye return from an ill-fated voyage aboard the Lusitania. Now I must try to catch Kate's voice and let her speak for herself. A cover image certainly helps. After a long search, I've found this photograph, which seems to me to represent Kate perfectly: her beauty, her enthusiasm, her energy. If you've read the books, does she look like Kate to you? I'd love to know!

From the collection of Patrick LynchI'm looking forward to getting to know Kate. Up until now, we've only seen her through other people's eyes: Polly, the servant who maids for her when she first comes to stay at the Hall in 1890; Eugenie Vye, Kate's sister-in-law, who considers her attempts to look after the tenants on the estate a waste of time and money; Grace, Polly's daughter, who works at the house during the First World War and sees Lady Vye return from an ill-fated voyage aboard the Lusitania. Now I must try to catch Kate's voice and let her speak for herself. A cover image certainly helps. After a long search, I've found this photograph, which seems to me to represent Kate perfectly: her beauty, her enthusiasm, her energy. If you've read the books, does she look like Kate to you? I'd love to know!So it will take a few more walks in the park before I've made a start at working it all out, before the characters begin to take shape. I don't want them to be cliches. The housekeeper, for example: we're all too familiar with a Mrs Danvers figure, hovering in the corridors full of malicious intent. Yet she can't be straightforwardly wonderful, either; there must be something or someone for Kate to rub up against (although Edward fills that role very well). I'm slightly concerned that her life may be too hard. If her marriage is unhappy, will the story be overly bleak? Somehow I must find a way of bringing joy into it.

I also need to think about where to begin. I wrote Eugenie's Story in the form of a diary, so that the reader discovered events pretty much the same time as she did. The first three stories were all told retrospectively, however, with a short coda at the end in the present tense - as Polly watches Kate leave the Hall to be married, as Grace and Philip declare their feelings for each other, and as Isobel describes what Swallowcliffe Hall has become in 1939. I think I might go back to that format. I may even have Kate starting the story by remembering her wedding, describing it quite differently from Polly. And Polly must come back into the story - she and Kate have a special bond - so I shall have to work out what's happening to her in 1900.

So much to decide! Now where's the dog lead?

Published on November 07, 2012 04:01

October 28, 2012

In Defence of Eugenie

Since releasing the latest volume in my Swallowcliffe Hall series, Eugenie's Story, about a month ago, I have come to realise that, while the book is selling well on both sides of the Atlantic, readers in the US don't actually seem to like Eugenie very much - or at least, not as much as Polly, Grace and Isobel. Poor Eugenie! I feel guilty. After all, I dreamed her up and now she's baring her soul in public, only to be condemned as a superficial airhead on Amazon.com.

Since releasing the latest volume in my Swallowcliffe Hall series, Eugenie's Story, about a month ago, I have come to realise that, while the book is selling well on both sides of the Atlantic, readers in the US don't actually seem to like Eugenie very much - or at least, not as much as Polly, Grace and Isobel. Poor Eugenie! I feel guilty. After all, I dreamed her up and now she's baring her soul in public, only to be condemned as a superficial airhead on Amazon.com.It's true that Eugenie is superficial - at least to begin with. She is a product of her class and time, obsessed with herself, unaware of the feelings and lives of others, blind to the many injustices around her. I wanted to create a less straightforward narrator for this story, so that when she assessed a particular situation or judged a certain person, the reader might wonder what the real truth of the matter was. The gap between Eugenie's frequently high-flown language and the mundane reality of her life is sometimes touching, and often (to me, at least) comical. Upper-class girls of marriageable age in the Edwardian era were placed under such narrow constraints, their opportunities for expression so few, that many of them must have been frequently verging on the edge of hysteria, just like Eugenie. Her blunders and misapprehensions lead her into such trouble! Here she is, visiting a tenant cottage on the Swallowcliffe estate where the man of the house lies ill upstairs. She has brought some cast-off clothes with her:

I visit the Beamishes, with qualified success. Bearing the mourning gowns Miss Pratt has deemed beyond salvation, I knock on their front door for some minutes before Mrs Beamish eventually emerges, sleeves rolled up and hair falling down at the back. Apparently it’s wash day. Inside, the cottage is in chaos: there are children tumbling about all over the place and the baby is wailing. Mrs B takes me into the front room, where the furniture is now covered in dustsheets, but has to keep darting back to the kitchen as the copper’s boiling over. I’m not offered any refreshment, and when I unpack the parcel to show her the mourning gowns, she starts to cry. It soon becomes clear these are not tears of gratitude, as I initially assumed. One of the children sidles into the room to stare at me but runs away when I attempt to engage it in conversation. Feeling a little de trop, I take my leave as soon as decently possible, promising to return another day; Mrs Beamish is clearly relieved. Despite the best of intentions, I fear I lack the common touch. Who else but Eugenie would consider mourning gowns a suitable gift when calling on the sick? I'm sorry, but she just makes me laugh. And that, I suppose, is the nub of the matter. If you don't find Eugenie at all funny, she must be hard to like. She's not particularly nice to her long-suffering maid, for example, constantly under-estimating and patronizing poor Bessie: The transformation of Bessie has begun! Part of the problem, I realized with one of those flashes of inspiration that seem to come so regularly to me now, is her name. ‘Bessie’ sounds positively bovine, and her surname is Cheesman which presents further difficulties. I can’t go about calling ‘Cheesman!’ – it would be too ridiculous and has connotations with trade. I have decided to call her Beth, which is so much more refined. The name makes me think of Little Women, one of my favourite books, and while Bessie (as was) may never reach the fictional Beth’s heights of saintliness, she has now been leant a certain dignity. If nothing in that passage makes you smile, at least inwardly, then Eugenie must seem very unlikeable. Books with unlikeable main characters can be hard work, yet they can also make a reader question the narrative and look for the truth between the lines. (Jane Harris's Gillespie and Me, for example, is quite brilliantly unsettling.) Granted, Eugenie is a snob, obsessed with herself and blind to the injustices around her, yet I've also tried to show that she's brave, passionate, kind-hearted in her own way, and funny. If anyone who's read the story would like to tell me what they think of her, I'd be fascinated. PS - And look at her tiny waist! How could anyone be charitable in a corset laced so tightly?

Published on October 28, 2012 11:38