D.W. Wilkin's Blog, page 169

November 21, 2014

An Unofficial Guide to how to win the Scenarios of Rollercoaster Tycoon 3

An Unofficial Guide to how to win the Scenarios of Rollercoaster Tycoon 3

I have been a fan of this series of computer games since early in its release of the very first game. That game was done by one programmer, Chris Sawyer, and it was the first I recall of an internet hit. Websites were put up in dedication to this game where people showed off their creations, based on real amusement parks. These sites were funded by individuals, an expense that was not necessarily as cheap then as it is now. Nor as easy to program then as it might be to build a web page now.

Prima Books released game guides for each iteration of the game, Rollercoaster Tycoon 1, Rollercoaster Tycoon 2 and Rollercoaster Tycoon 3 (RCT3) but not for the expansion sets. And unlike the first two works, the third guide was riddle with incorrect solutions. As I played the game that frustrated me. And I took to the forums that Atari, the game publisher hosted to see if I could find a way to solve those scenarios that the Prima Guide had written up in error. Not finding any good advice, I created my own for the scenarios that the “Official” Guide had gotten wrong.

Solutions that if you followed my advice you would win the scenario and move on. But if you followed the

“Official” version you would fail and not be able to complete the game. My style and format being different than the folks at Prima, I continued for all the Scenarios that they had gotten right as well, though my solutions cut to the chase and got you to the winner’s circle more quickly, more directly.

My contributions to the “Official” Forum, got me a place as a playtester for both expansions to the game, Soaked and Wild. And for each of these games, I wrote the guides during the play testing phase so all the play testers could solve the scenarios, and then once again after the official release to make changes in the formula in case our aiding to perfect the game had changed matters. For this, Atari and Frontier (the actual programmers of the game) placed me within the game itself.

And for the longest time, these have been free at the “Official” Forums, as well as my own website dedicated to the game. But a short time ago, I noticed that Atari, after one of its bankruptcies had deleted their forums. So now I am releasing the Guide for one and all. I have added new material and it is near 100 pages, just for the first of the three games. It is available for the Kindle at present for $2.99.

(Click on the picture to purchase)

Not only are all 18 Scenarios covered, but there are sections covering every Cheat Code, Custom Scenery, the famous Small Park Competition, the Advanced Fireworks Editor, the Flying Camera Route Editor which are all the techniques every amusement park designer needs to make a fantastic park in Rollercoaster Tycoon 3.

November 20, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-William Charles Keppel 4th Earl of Albemarle

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

William Charles Keppel 4th Earl of Albemarle

14 May 1772 – 30 October 1849

William Charles Keppel

William Charles Keppel 4th Earl of Albemarle was the only child of General George Keppel, 3rd Earl of Albemarle, and Anne, daughter of Sir John Miller, 4th Baronet. He succeeded in the earldom in October 1772, aged five months, on the early death of his father. He was educated at St John’s College, Cambridge.

On the formation of the Ministry of All the Talents in 1806, Lord Albemarle was appointed Master of the Buckhounds by Lord Grenville. Thereby he became an officer in the Master of the Horse’s department in the Royal Household and also the equivalent of today’s Representative of Her Majesty at Ascot. The Mastership of the Buckhounds being a political office, the holder changed with every government and because the Earl’s patrons fell in March 1807 he lost his position after only one year. He remained out of office until 1830 when he was sworn of the Privy Council and made Master of the Horse by Lord Grey which was the third ranking officer at court (after the Lord Chamberlain and Lord Steward). He continued in this office until November 1834, the last few months under the premiership of Lord Melbourne, and held the same post under Melbourne between 1835 and 1841. Consequently he was responsible for managing all matters equine at the changeover from one reign to the next and, in particular, at Queen Victoria’s Coronation. The Earl was accorded the honour of travelling to Westminster Abbey inside the Gold State Coach with the nineteen-year-old, and as yet unmarried Victoria, who recorded in her diary:

“At 10 I got into the State Coach with the Duchess of Sutherland and Lord Albemarle…It was a fine day, and the crowds of people exceeded what I have ever seen; their good humour and excessive loyalty was beyond everything, and I really cannot say how proud I feel to be the Queen of such a nation”.

In addition to managing the bloodstock of two successive Heads of State, when the horse was still a main mode of transport, the 4th Earl of Albemarle was also a leading racehorse owner of his day. As an owner, William Charles won two Classics (the 1000 Guineas in 1838 with Barcarolle and the 2000 Guineas in 1841), and the Ascot Gold Cup three times (with two different horses) in 1843, 1844, and 1845. The second Gold Cup win, in 1844, was by a colt which the Earl had not yet named. One of the witnesses of this triumph, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, let William Charles know how excited he had been by the race, and the Earl promptly named his horse “The Emperor” in honour of the distinguished Russian visitor. In 1845, when “The Emperor” won the Gold Cup (now renamed The Emperor’s Plate) again the Earl received a massive silver centrepiece paid for by the Tsar as the race prize based on Falconet’s well known sculpture of Peter the Great in St Petersburg, the base flanked by Russian equestrian troops. William Charles’s horses were also victorious in the 1840s in the Cesarevitch and Cambridgeshire major handicaps run at Newmarket.

In 1833 he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Hanoverian Order.

Lord Albemarle married, firstly, the Hon. Elizabeth Southwell, daughter of Edward Southwell, 20th Baron de Clifford, on 9 April 1792. They had eleven children:

William Keppel, Viscount Bury (1793 – 1804), died young.

Augustus Frederick Keppel, 5th Earl of Albemarle (1794 – 1851), who married Frances Steer. No issue.

Lady Sophia Keppel (c. 1798 – 1824), married Sir James Macdonald, 2nd Baronet and had issue.

George Thomas Keppel, 6th Earl of Albemarle (1799 – 1891), through whom is descended Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall

Reverend Hon. Edward Southwell Keppel (1800 – 1883), Dean of Norwich, married Lady Maria, daughter of Nathaniel Clements, 2nd Earl of Leitrim.

Lady Anne Amelia Keppel (1803 – 1844), married Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester, through whom is descended Sarah, Duchess of York; married, secondly, Edward Ellice.

Lady Mary Keppel (1804 – 1898), married Henry Frederick Stephenson, MP, and had issue.

Admiral Hon. Sir Henry Keppel (1809 – 1904), married Katherine Crosby and had issue.

Reverend Hon. Thomas Robert Keppel (1811 – 1863), married Frances Barrett-Lennard, daughter of Sir Thomas Barrett-Lennard, 1st Baronet and had issue.

Lady Caroline Elizabeth Keppel (1814 – 1898), married the Very Reverend Thomas Garnier and had issue.

Lady Georgiana Charlotte (d. 1854), married William Henry Magan.

After his first wife’s death in November 1817, aged 41, Lord Albemarle married, secondly, Charlotte Susannah, daughter of Sir Henry Hunloke, 4th Baronet, on 11 February 1822. This marriage was childless. He died at Quidenham, Norfolk, in October 1849, aged 77, and was succeeded in the earldom by his second but eldest surviving son, Augustus.

The Dowager Countess, Charlotte Susannah, was nicknamed the “Rowdy Dow” by her stepchildren, who accused her of squandering the family’s fortune. In the words of one biographer: “[She] managed to disperse Keppel heirlooms with extravagant eccentricity.” The Dowager Countess of Albemarle died at Twickenham, London, in October 1862, aged 88.

Caution’s Heir from Regency Assembly Press-Now available everywhere!

Caution’s Heir is now available at all our internet retailers and also in physical form as well

The Trade Paperback version is now available for purchase here @ $15.99 (but as of this writing, it looks like Amazon has still discounted it 10%)

Caution’s Heir is also available digitally for $4.99 @ the iBookstore, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo and Smashwords.

The image for the cover is a Cruikshank, A Game of Whist; Tom & Jerry among the ‘Swell Broad Coves.’ Tom and Jerry was a very popular series of stories at the time.

Teaching a boor a lesson is one thing.

Winning all that the man owns is more than Lord Arthur Herrington expects. Especially when he finds that his winnings include the boor’s daughter!

The Duke of Northampshire spent fortunes in his youth. The reality of which his son, Arthur the Earl of Daventry, learns all too well when sent off to school with nothing in his pocket. Learning to fill that pocket leads him on a road to frugality and his becoming a sober man of Town. A sober but very much respected member of the Ton.

Lady Louisa Booth did not have much hope for her father, known in the country for his profligate ways. Yet when the man inherited her gallant uncle’s title and wealth, she hoped he would reform. Alas, that was not to be the case.

When she learned everything was lost, including her beloved home, she made it her purpose to ensure that Lord Arthur was not indifferent to her plight. An unmarried young woman cast adrift in society without a protector. A role that Arthur never thought to be cast as. A role he had little idea if he could rise to such occasion. Yet would Louisa find Arthur to be that one true benefactor? Would Arthur make this obligation something more? Would a game of chance lead to love?

Today, the iBookstore is added, HERE

Get for your Kindle, Here

In Trade Paperback, Here

Digitally from Smashwords, Here

For your Sony Kobo, Here

Or for your Nook, Here

From our tale:

Chapter One

St. Oswald’s church was bleak, yet beautiful all in one breath. 13th century arches that soared a tad more than twenty feet above the nave provided a sense of grandeur, permanence and gravitas. These prevailed within, while the turret-topped tower without, once visible for miles around now vied with mature trees to gain the eye of passers-by.

On sunny days stain-glass windows, paid for by a Plantagenet Baron who lived four hundred years before and now only remembered because of this gift, cast charming rainbow beams across the inner sanctum. And on grey overcast days ghostly shadows danced along the aisle.

As per the custom of parish churches the first three pews were set-aside for the gentry. On this day the second pew, behind the seat reserved for the Marquess of Hroek, who hadn’t attended since the passing of his son and heir, was Louisa Booth his niece and her companion Mrs Bottomworth.

Mrs Bottomworth was a stocky matron on the good side of fifty. Barely on the good side of fifty. But one would not say that was an unfortunate thing for she wore her years well and kept her charge free of trouble. Mrs Bottomworth’s charge was an only child, who would still have been in the schoolroom excepting the fact of the death of her mother some years earlier. This had aged the girl quickly, and made her hostess to her father’s household. The Honourable Hector Booth, third son of the previous Marquess, maintained a modest house on his income of 300 pounds. That was quite a nice sum for just the man and one daughter, with but five servants. They lived in a small, two floor house with four rooms. It should be noted that this of course left two bedchambers that were not inhabited by family members. As the Honourable Mr Booth saved his excess pounds for certain small vices that confined themselves with drink and the occasional wager on a horse, these two rooms were seldom opened.

Mrs Bottomworth had thought to make use of one of the empty rooms when she took up her position, but the Honourable Hector Booth advised and instructed her to share his daughter’s room. For the last four years this is what she had done. When two such as these shared a room, it was natural that they would either become best of friends, or resent each other entirely. Happily the former occurred as Louisa was in need of a confidant to fill the void left in her mother’s absence, and Mrs Bottomworth had a similar void as her two daughters had grown and gone on to make their own lives.

The Honourable Mr Booth took little effort in concerning himself with such matters as he was ever about his brother’s house, or ensconced in a comfortable seat at either the local tavern or the Inn. If those locations had felt he was too warm for them, he would make a circuit of what friends and acquaintances he had in the county. The Honourable Mr Booth would spend an hour or two with a neighbour discussing dogs or hunters, neither of which he could afford to keep, though he did borrow a fine mount of his brother to ride to the hunt. The Marquess took little notice, having reduced his view of the world by degrees when first his beloved younger brother who was of an age between the surviving Honourable Mr Booth had perished shortly after the Marquess’ marriage. Their brother had fallen in the tropics of a fever. Then the Marquess had lost his second child, a little girl in her infancy, his wife but a few years after, and most recently his son and heir to the wars with Napoleon.

This caused the Honourable Mr Booth to be heir to Hroek, a situation that had occurred after he had lost his own wife. With that tragedy, Mr Booth had found more time to make friends with all sorts of new bottles, though not to a degree that it was considered remarkable beyond a polite word. Mr Booth was not a drunkard. He was confronting his grief with a sociability that was acceptable in the county.

Louisa, however, was cast further adrift. No father to turn to. No uncle who had been the patriarch of the family her entire life. And certainly now no feminine examples to follow but her companion and governess, Mrs Bottomworth. That Mrs Bottomworth was an excellent choice for the task was more due to acts of the Marquess, still able to think clearly at the time she was employed, than to the Honourable Mr Booth. Mr Booth was amenable to any suggestion of his elder brother for that man controlled his purse, and as Mr Booth was consumed with grief, while the Marquess had adapted to various causes of grief prior to the final straw of his heir’s death, the Marquess of Hroek clearly saw a solution to what was a problem.

Now in her pew, where once as a young girl she had been surrounded by her cousins, parents, uncles and aunt, she sat alone except for her best of friends. Louisa was full of life in her pew, her cheeks a shade of pink that contrasted with auburn hair, which glistened as sunlight that flowed though the coloured panes of glass touched it from beneath her bonnet. Blue eyes shown over a small straight nose, her teeth were straight, though two incisors were ever so slightly bigger than one would attribute to a gallery beauty painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

She was four inches taller than five feet, so rather tall for a young woman, but her genes bred true, and many a girl of the aristocracy was slightly taller than those women who were of humbler origins. Her back was straight and for an observant man, of which there were some few in the county, her figure might be discussed. The wrath though of her uncle the Marquess would not wish to be bourne should it be found out that her form had become a topic amongst the young men. Noteworthy though was that she had a figure that men thought inspiring enough to tempt that wrath, and think on it. A full bosom was high on her chest, below her heart shaped face. She was lean of form, though her hips flared just enough that one could see definition in her torso. Certainly a beauty Sir Thomas’ brushes would wish the honour to meet.

The vicar Mr Spotslet had at one time in his early days in the community, discussed the Sunday sermons with the Marquess. Mr Spotslet had enjoyed long discussions of theology, philosophy, natural history and the holy writ that were then thoughtfully couched in terms to be made accessible by the parish. The lassitude that had overtaken the Marquess had caused those interviews to become shortened and infrequent and as such the sermons suffered, as many were wont to note. There had been dialogues that Mr Spotslet had engaged in with the attendees of his masses. Now he seemed to have lost his way and delivered soliloquies.

This day Mr Spotslet indulged in a speech that talked to the vices of gambling. The local sports, of which the Honourable Mr Booth was an intimate, had raced their best through the village green the previous Wednesday for but a prize of one quid, and this small bet had caused pandemonium when Mrs McCaster had fallen in the street with her washing spread everywhere and trampled by the horses. Not much further along the path, Mr Smith the grocer’s delivery for the vicar himself was dropped by the boy and turned into detritus as that too was stampeded over. A natural choice for a sermon, yet only two of the culprits were in attendance this day. The rest had managed to find reasons to avoid the Mass.

Louisa squirmed a little in her seat the moment she realised that her father had been one of the men that the sermon was speaking of. Was she not the centre of everyone’s gaze at such a time? Her father having refused to attend for some years, and her uncle unable due to his illness. She was the representative of the much reduced family. Not only was it expected that the parish would look to her as the Booth of Hroek, but with her father’s actions called to the attentions of all, it was natural that they look at her again. This time in a light that did not reflect well on her father and she knew that she had no control over that at all.

Mrs Bottomworth, who might have been lightly resting her eyes, Louisa would credit her in such a generous way, came to tensing at the mention of the incident. Louisa did not want to bring her friend to full wakefulness, but Mrs Bottomworth realised what was occurring and the direction that the sermon was taking. Louisa’s companion took her hand and patted it reassuringly.

“Perhaps a social call on Lady Walker?” Mrs Bottomworth suggested as they walked back to the house after services. The house which sat just within the estate boundaries was four hundred feet off the main bridal way that led to Hroek Castle. A small road had been cleared from the gatehouse to the house that Mr Booth now maintained, and this the two women travelled.

Louisa generally appreciated visits such as this as she had gotten older, and certainly several of the adults in the neighbourhood showed a kindly interest in her education and the development of her social manners. “I think I shall go to the castle and read to my uncle.” A task that she had done each day of the last fortnight but one.

“We have not talked, but you and the Marquess had an interview with the doctors.” Mrs Bottomworth had tried to comfort her charge after that, but Louisa had waved her hand and gone to sit quietly under a yew tree that had a grand vista of the park leading to Hroek Castle.

“Uncle will be most lucky if he should be with us come Michaelmas.”

“That will be a sad day when we lose such a friend.” These were words of comfort. Mrs Bottomworth had been well encouraged in her charge by the Marquess but one could not say that they interacted greatly with one another. The Marquess ensured that his brother heeded the suggestions and advisements of Mrs Bottomworth as the Honourable Mr Booth left to his own devices would have kept his daughter in the nursery and would have forgotten to send a governess to provide her with instruction.

“Indeed, my uncle may not have been one of the great men of England, but he is well regarded in the county.” Often with that statement followed the next, “Warmly remembered is it when the Prince Regent came and stayed for a fortnight of sport and entertainment.” This had been many years before, and certainly before any of the tragedies beset the line of the Booths.

“Yes, I have heard it said with great earnestness. But come let us change your clothes and then we shall go up to the great house. I shall have Mallow fetch the gig so we may proceed all the more expeditiously.”

“That would be good, but we will have to use the dogcart. Father was to take the gig to see Sir Mark today, or so he said at breakfast.” Where Louisa knew he would drink the Baronet’s sherry for a couple hours before thinking to return, unless he was asked to stay for dinner.

November 19, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Sir John Simeon 1st Baronet

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Sir John Simeon 1st Baronet

1756 – 4 February 1824

Sir John Simeon 1st Baronet of Walliscot in Oxfordshire was Member of Parliament (MP) for Reading in Berkshire from 1797 to 1802 and from 1806 to 1818. He also practised as barrister and a member of Lincoln’s Inn, and held the offices of Recorder of Reading 1779-1807 and Master in Chancery from 1795 until 1808 when he became Senior Master, and was created 1st Baronet Simeon in 1815.

Simeon was the second eldest son of Richard Simeon (died 1784) and Elizabeth Hutton. His elder brother, named Richard after their father, died early. The third brother, Edward Simeon, was a director of the Bank of England. His youngest brother, Charles Simeon, became a prominent evangelical clergyman.

Rebecca, Lady Simeon

John Simeon married Rebecca Cornwall, daughter of John Cornwall of Hendon House in Middlesex, in 1783. They had a number of children:

Richard G. Simeon married Louisa-Edith Barrington on 8 April 1813, producing three sons and two daughters

Harriet Simeon married Sir Frederick Francis Baker, 2nd Baronet in July 1814, producing 1 daughter and 3 sons.

November 18, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Francis Douglas 8th Earl of Wemyss

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Francis Douglas 8th Earl of Wemyss 4th Earl of March

15 April 1772 – 28 June 1853

Francis Douglas 8th Earl of Wemyss 4th Earl of March was the son of Francis Wemyss Charteris, Lord Elcho (1749–1808), and the grandson of Francis Charteris, de jure 7th Earl of Wemyss. In 1810 he succeeded his second cousin twice removed William Douglas, 4th Duke of Queensberry and 3rd Earl of March to the Earldom of March, as the lineal heir male of the aforementioned Lady Anne Douglas, sister of the first Earl of March.

In 1821 he was created Baron Wemyss, of Wemyss in the County of Fife, in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, which entitled him to an automatic seat in the House of Lords. In 1826 he obtained a reversal of the attainder of the earldom of Wemyss and became the eighth Earl of Wemyss as well. From 1821 to 1853 he served as Lord-Lieutenant of Peeblesshire.

On 31 May 1794, he married Margaret Campbell and they had eight children:

Lady Charlotte Charteris (d. 1886)

Lady Louisa Antoinetta Charteris (d. 1854)

Lady Harriet Charteris (d. 1858)

Lady Eleanor Charteris (1796–1832), married Walter Frederick Campbell of Shawfield

Francis Wemyss-Charteris, 9th Earl of Wemyss (1796–1883)

Hon. Walter Charteris (1797–1818)

Lady Margaret Charteris (1800–1825)

Lady Katherine Charteris Wemyss (1801–1844), married her first cousin George Grey, 8th Baron Grey of Groby.

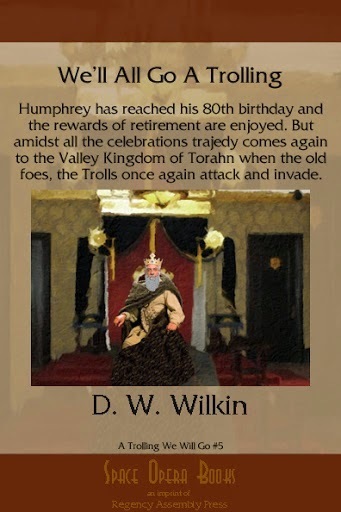

Conclusion of the Trolling Series-We’ll All Go A Trolling

We’ll All Go A Trolling Not only do I write Regency and Romance, but I also have delved into Fantasy.

The Trolling series is the story of a man, Humphrey. We meet him as he has left youth and become a man with a man’s responsibilities.

We follow him in a series of stories that encompass the stages of life. We see him when he starts his family, when he has older sons and the father son dynamic is tested.

We see him when his children begin to marry and have children, and at the end of his life when those he has loved, and those who were his friends proceed him over the threshold into death.

All this while he serves a kingdom troubled by monsters. Troubles that he and his friends will learn to deal with and rectify. It is now available in a variety of formats.

For $2.99 you can get this fantasy adventure.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook

King Humphrey, retired, has his 80th birthday approaching. An event that he is not looking forward to.

A milestone, of course, but he has found traveling to Torc, the capital of the Valley Kingdom of Torahn, a trial. He enjoys his life in the country, far enough from the center of power where his son Daniel now is King and rules.

Peaceful days sitting on the porch. Reading, writing, passing the time with his guardsmen, his wife, and the visits of his grandson who has moved into a manor very near.

Why go to Torc where he was to be honored, but would certainly have a fight with his son, the current king. The two were just never going to see eye to eye, and Humphrey, at the age of 80, was no longer so concerned with all that happened to others.

He was waiting for his audience with the Gods where all his friends had preceded him. It would be his time soon enough.

Yet, the kingdom wanted him to attend the celebrations, and there were to be many. So many feasts and fireworks he could not keep track, but the most important came at the end, when word was brought that the Trolls were attacking once more.

Now Humphrey would sit as regent for his son, who went off to fight the ancient enemy. Humphrey had ruled the kingdom before, so it should not have been overwhelming, but at eighty, even the little things could prove troublesome.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

November 17, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Lucia Elizabeth Vestris

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Lucia Elizabeth Vestris

January 1797 – 8 August 1856

Lucia Elizabeth Vestris

Lucia Elizabeth Vestris January 1797 – 8 August 1856) was an English actress and a contralto opera singer, appearing in works by Mozart and Rossini. While popular in her time, she was more notable as a theatre producer and manager. After accumulating a fortune from her performances, she leased the Olympic Theatre in London and produced a series of burlesques and extravaganzas for which the house became famous, especially popular works by James Planché. She also produced his work at other theatres she managed.

She was born Elizabetta Lucia Bartolozzi in London in 1797, the first of two daughters of the highly regarded German pianist Theresa Jansen Bartolozzi and Gaetano Stefano Bartolozzi. He was a musician and son of the immigrant Francesco Bartolozzi, a noted artist and engraver, appointed as Royal Engraver to the king. Gaetano Bartolozzi was a successful art dealer, and the family moved to Europe in 1798 when he sold off his business. They spent time in Paris and Vienna before reaching Venice, where they found that their estate had been looted during the French invasion. They returned to London to start over, where Gaetano taught drawing. They separated there and Therese gave piano lessons to support her daughters.

Lucia studied music and was noted for her voice and dancing ability. She was married at age 16 to the French dancer, Auguste Armand Vestris, a scion of the great family of dancers of Florentine origin, but her husband deserted her four years later. Nevertheless, since she had started singing and acting professionally as “Madame Vestris”, she retained the stage name throughout her career.

In 1815 her contralto voice and attractive appearance gained Madame Vestris her first leading role at age 18 in Italian opera in the title-role of Peter Winter’s II ratto di Proserpina at the King’s Theatre, where she also sang in 1816 in Martín y Soler’s Una cosa rara and performed the roles of Dorabella and Susanna in Mozart’s operas Così fan tutte and The Marriage of Figaro. She had immediate success in both London and Paris. In the French capital city she occasionally appeared at the Théâtre-Italien and various other theatres, and legend has it that she even performed as a tragic actress at the Théâtre-Français playing Camille opposite François-Joseph Talma in Corneille’s Horace. Which however has turned out to be untrue. The mistake derived from a misreading of Talma’s Mémoires where the actor narrates an episode in which a ‘Madame Vestris’ – not Eliza Lucia Vestris, who was born several years later.

Her first hits in English were in 1820 at age 23 at the Drury Lane in Stephen Storace’s Siege of Belgrade, and in Moncrieff’s burlesque Giovanni in London, where she performed the male title-role of no less than Don Giovanni: the succès de scandale of this breeches performance in which she showed off her fabulously perfect legs, launched her career as a scandalous beauty. Thenceforward she remained an extraordinary favourite in opera, musical farces and comedies until her retirement in 1854. At the King’s Theatre she sang in the English premieres of many Rossini operas, sometimes conducted by the composer himself: La gazza ladra (as Pippo, 1821), La donna del lago (as Malcolm Groeme, 1823), Ricciardo e Zoraide (as Zomira, 1823), Matilde di Shabran (as Edoardo, 1823), Zelmira (as Emma, 1824) and Semiramide (as Arsace, 1824)”.

She excelled in “breeches parts,” and she also performed in Mozart operas, such as Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Blonde) in 1728, and later, in 1742, The Marriage of Figaro (Cherubino), in a complete specially crafted English version by James Planché. She was credited with popularizing such new songs as “Cherry Ripe”, “Meet Me by Moonlight Alone” (written by Joseph Augustine Wade), I’ve been roaming,” etc. She also took part in world premieres, creating the role of Felix in Isaac Nathan’s comic opera The Alcaid or The Secrets of Office, (London, Little Theatre in the Haymarket, 1824), and, above all, that of Fatima in Oberon or The Elf King’s Oath, “the Grand Romantic and Fairy Opera” by Carl Maria von Weber, which was given at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden on 12 April 1826.

In 1830, having accumulated a fortune from her performing, she leased the Olympic Theatre from John Scott. There she began presenting a series of burlesques and extravaganzas—for which she made this house famous. She produced numerous works by the contemporary playwright James Planché, with whom she had a successful partnership, in which he also contributed ideas for staging and costumes.

She married in 1838 for the second time, to the British actor Charles James Mathews and accompanied him on tour to America. She aided him in his subsequent managerial ventures, including the management of the Lyceum Theatre and the theatre in Covent Garden.

Mme Vestris and Mathews inaugurated their management of Covent Garden with the first-known production of Love’s Labour’s Lost since 1605; Vestris played Rosaline. In 1840 she staged one of the first relatively uncut productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which she played Oberon. This began a tradition of female Oberons that lasted for 70 years in the British theatre.

In 1841 Vestris produced the highly successful Victorian farce London Assurance by Dion Boucicault, with possibly the first use of a “box set”.

She also introduced the soprano Adelaide Kemble to the theatre in Bellini’s Norma and La Sonnambula. A daughter of John Kemble, actor-manager and one of the theatre’s owners, and niece of Sarah Siddons Adelaide had a sensational but short career before retiring into marriage.

About her time in charge at Covent Garden, a note by the actor James Robertson Anderson reported in C.J. Mathews’s autobiography, says:

Madame was an admirable manager, and Charles an amiable assistant. The arrangements behind the scenes were perfect, the dressing rooms good, the attendants well-chosen, the wings kept clear of all intruders, no strangers or crutch and toothpick loafers allowed behind to flirt with the ballet-girls, only a very few private friends were allowed the privilege of visiting the green-room, which was as handsomely furnished as any nobleman’s drawing-room, and those friends appeared always in evening dress….There was great propriety and decorum observed in every part of the establishment, great harmony, general content prevailed in every department of the theatre, and universal regret was felt when the admirable managers were compelled to resign their government.

Another contemporary actor George Vandenhoff in Dramatic Reminiscences also bears testimony to the fact that: ‘To Vestris’s honour, she was not only scrupulously careful not to offend propriety by word or action, but she knew very well how to repress any attempt at double-entendre, or doubtful insinuation, in others. The green-room in Covent Garden was a most agreeable lounging place, from which was banished every word or allusion that would not be tolerated in a drawing-room.’

Her last performance (1854) was for Mathews’ benefit, in an adaptation of Madame de Girardin’s La Joie fait peur, called Sunshine through Clouds. She died in London in 1856.

RAP has The End of the World

The End of the World This is the first of the Regency Romances I published. It is available for sale and I hope that you will take the opportunity to order your copy.

For yourself or as a gift. It is now available in a variety of formats. For $5.99 you can get this Regency Romance for your eReader. A little more as an actual physical book.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook

Amazon for your Kindle and as a Trade Paperback

Hermione Merwyn leads a pleasant, quiet life with her father, in the farthest corner of England. All is as it should be, though change is sure to come. For she and her sister have reached the age of marriage, but that can be no great adventure when life at home has already been so bountiful.

When Samuel Lynchhammer arrives in Cornwall, having journeyed the width of the country, he is down to his last few quid and needs to find work for his keep. Spurned by the most successful mine owner in the county, Gavin Tadcaster, Samuel finds work for Gavin’s adversary, Sir Lawrence Merwyn.

Can working for Sir Lawrence, the father of two young women on the cusp of their first season to far away London, be what Samuel needs to help him resolve the reasons for his running away from his obligations in the east of the country?

Will the daughters be able to find happiness in the desolate landscapes and deadly mines of their home? When a stranger arrives in Cornwall while the war rages on the Peninsula, is he the answer to one’s prayers, or a nightmare wearing the disguise of a gentleman?

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

November 16, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Sir John Thomas Duckworth 1st Baronet

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Sir John Thomas Duckworth 1st Baronet

9 February 1748 – 31 August 1817

John Thomas Duckworth

Sir John Thomas Duckworth 1st Baronet was Born in Leatherhead, Surrey, England, Duckworth was one of five sons of Sarah Johnson and the vicar Henry Duckworth A.M. of Stoke Poges, County of Buckinghamshire. The Duckworths were descended from a landed family, with Henry later being installed as Canon of Windsor. John Duckworth went to Eton College, but began his naval career in 1759 at the suggestion of Edward Boscawen, when he entered the Royal Navy as a midshipman on HMS Namur. Namur later became part of the fleet under Sir Edward Hawke, and Duckworth was present at the Battle of Quiberon Bay on 20 November 1759. On 5 April 1764 he joined the 50-gun HMS Guernsey at Chatham, after leaving HMS Prince of Orange, to serve with Admiral Hugh Palliser, then Governor of Newfoundland. He served aboard HMS Princess Royal, on which he suffered a concussion when he was hit by the head of another sailor, decapitated by a cannonball. He spent some months as an acting lieutenant, and was confirmed in the rank on 14 November 1771. He then spent three years aboard the 74-gun HMS Kent, the Plymouth guardship, under Captain Charles Fielding. Fielding was given command of the frigate HMS Diamond in early 1776, and he took Duckworth with him as his first lieutenant. Duckworth married Anne Wallis in July 1776, with whom he had a son and a daughter.

After some time in North America, where Duckworth became involved in a court-martial after an accident at Rhode Island on 18 January 1777 left several men dead, the Diamond was sent to join Vice-Admiral John Byron’s fleet in the West Indies. Byron transferred him to his own ship, HMS Princess Royal, in March 1779, and Duckworth was present aboard her at the Battle of Grenada on 6 July 1779. Duckworth was promoted to commander ten days after this and given command of the sloop-of-war HMS Rover. After cruising off Martinique for a time, he was promoted to post captain on 16 June 1780 and given command of the 74-gun HMS Terrible. He returned to the Princess Royal as flag-captain to Rear-Admiral Sir Joshua Rowley, with whom he went to Jamaica. He was briefly in command of HMS Yarmouth, before moving into HMS Bristol in February 1781, and returned to England with a trade convoy. In the years of peace before the French Revolution he was a captain of the 74-gun HMS Bombay Castle, lying at Plymouth.

Fighting against France, Duckworth distinguished himself both in European waters and in the Caribbean. He was initially in command of the 74-gun HMS Orion from 1793 and served in the Channel Fleet under Admiral Lord Howe. He was in action at the Glorious First of June. Duckworth was one of few commanders specifically mentioned by Howe for their good conduct, and one of eighteen commanders honoured with the Naval Gold Medal, and the thanks of both Houses of Parliament. He was appointed to command the 74-gun HMS Leviathan in early 1794, and went out to the West Indies where he served under Rear-Admiral Sir William Parker. He was appointed commodore at Santo Domingo in August 1796. In 1798 Duckworth was in command of a small squadron of four vessels. He sailed for Minorca on 19 October 1798, where he was a joint commander with Sir Charles Stuart, initially landing his 800 troops in the bay of Addaya, and later landing sailors and marines from his ships, which included the frigates HMS Cormorant and HMS Aurora, to support the Army. He was promoted to rear-admiral of the white on 14 February 1799 following Minorca’s capture, and “Minorca” was later inscribed on his coat of arms. In June his squadron of four ships captured Courageux.

In April 1800 was in command of the blockading squadron off Cadiz, and intercepted a large and rich Spanish convoy from Lima off Cadiz, consisting of two frigates (both taken as prizes) and eleven merchant vessels, with his share of the prize money estimated at £75,000. In June 1800 he sailed to take up his post as the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief at Barbados and Leeward Islands, succeeding Lord Hugh Seymour.

Duckworth was nominated a Knight Companion of the most Honourable Military Order of the Bath in 1801 (and installed in 1803), for the capture of the islands of St. Bartholomew, St. Martin, St. Thomas, St. John and St. Croix and defeat of the Swedish and Danish forces stationed there on 20 March 1801. Lieutenant-General Thomas Trigge commanded the ground troops, which consisted of two brigades under Brigadier-Generals Fuller and Frederick Maitland, of 1,500 and 1,800 troops respectively. These included the 64th Regiment of Foot (Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Pakenham), and the 2nd and 8th West Indies Regiments, two detachments of Royal Artillery, and two companies of sailors, each of about 100 men. The ships involved, in addition to Leviathan, included HMS Andromeda, HMS Unite, HMS Coromandel, HMS Proselyte, HMS Amphitrite, HMS Hornet, the brig HMS Drake, armed brig HMS Fanny, schooner HMS Eclair, and tender HMS Alexandria. Aside from the territory and prisoners taken during the operation, Duckworth’s force took two Swedish merchantmen, a Danish ship (in ballast), three small French vessels, one privateer brig (12-guns), one captured English ship, a merchant-brig, four small schooners, and a sloop.

From 1803 until 1805, Duckworth assumed command as the commander-in-chief of the Jamaica Station, during which time he directed the operations which led to the surrender of General Rochambeau and the French army, following the successful Blockade of Saint-Domingue. Duckworth was promoted to vice-admiral of the blue on 23 April 1804, and he was appointed a Colonel of Marines. He succeeded in capturing numerous enemy vessels and 5,512 French prisoners of war. In recognition of his service, the Legislative Assembly of Jamaica presented Duckworth with a ceremonial sword and a gold scabbard, inscribed with a message of thanks. The merchants of Kingston provided a second gift, an ornamental tea kettle signifying Duckworth’s defence of sugar and tea exports Both sword and kettle were subsequently gifted to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

Duckworth remained in Jamaica until 1805, returning to England that April aboard HMS Acasta. On his return to England again, he was called to face court-martial charges brought by Captain James Athol Wood of HMS Acasta, who claimed that Duckworth had transgressed the 18th Article of War; “Taking goods onboard other than for the use of the vessel, except gold & etc.” Duckworth had apparently acquired some goods, and in wishing to transport them home in person reassigned Captain Wood to another vessel on Jamaica station knowing that the vessel was soon to be take under command by another flag officer. Consequently Duckworth was able to take the goods to England as personal luggage, and Wood was forced to sail back as a passenger on his own ship. The court-martial was held on board HMS Gladiator in Portsmouth on 25 April 1805, but the charge was dropped on 7 June 1805.

In 1805 the Admiralty decided that Duckworth should raise his flag aboard HMS Royal George and sail to join Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson off Cadiz. However, the Plymouth Dockyards could not make Royal George ready to sail in time, and Duckworth was directed to raise his flag in HMS Superb, with Captain Richard Keats as his flag-captain. By the time of his arrival on 15 November, the Battle of Trafalgar had been fought. Duckworth was ordered to take command of the West Indies squadron involved in the blockade of Cadiz, with seven sail of the line, consisting of five 74-gun ships, the 80-gun HMS Canopus and the 64-gun HMS Agamemnon, and two frigates.

Although known for a cautious character, he abandoned the blockade and sailed in search of a French squadron under Admiral Zacharie Allemand, which had been reported by a frigate off Madeira on 30 November, on his own initiative. While searching for the French, which eventually eluded him, he came across another French squadron on 25 December, consisting of six sail of the line and a frigate. This was the squadron under Contre-Admiral Jean-Baptiste Willaumez, heading for the Cape of Good Hope, and pursued by Rear-Admiral Sir Richard Strachan. Duckworth gave chase, but with his squadron scattered, decided not to risk engaging with his one ship, and gave it up.

Duckworth then set sail for the Leeward Islands to take on water, dispatching the 74-gun HMS Powerful to reinforce the East Indies squadron. There, at Saint Kitts, he was joined on 21 January 1806 by the 74-gun ships HMS Northumberland and HMS Atlas commanded by Sir Alexander Cochrane, and on 1 February a brig Kingfisher commanded by Nathaniel Day Cochrane, which brought news of French at San Domingo. The French had a squadron of five ships: the 120-gun Imperial, two 84-gun and two 74-gun ships and two frigates, under the command of Vice-Admiral Corentin Urbain Leissègues which escaped from Brest and sought to reinforce the French forces at San Domingo with about 1,000 troops. Arriving at San Domingo on 6 February 1806, Duckworth found the French squadron with its transports anchored in the Occa bay. The French commander immediately hurried to sea, forming a line of battle as they went. Duckworth gave the signal to form two columns of four and three ships of the line.

In the Battle of San Domingo, Duckworth’s squadron defeated the squadron of French when

Duckworth at once made the signal to attack and “with a portrait of Nelson suspended from the mizzen stay of the Superb with the band playing ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Nelson of the Nile’, bore down on the leading French ship Alexandre of 84 guns and engaged her at close quarters. After a severe action of two hours, two of the French ships were driven ashore and burnt with three others captured. Only the French frigates escaped.

Despite this, it is thought that Duckworth used his own ship cautiously, and the credit for the victory was due more to the initiative of the individual British captains. Duckworth nearly grounded his own ship as he attempted to board Impérial.

His victory over the French Admiral Leissègues off the coast of Hispaniola on 6 February together with Admiral Alexander Cochrane’s squadron was a fatal blow to French strategy in the Caribbean region, and played a major part in Napoleon’s eventual sale of Louisiana, and withdrawal from the Caribbean. It was judged sufficiently important to have the Tower of London guns fire a salute. San Domingo was added to Duckworth’s coat of arms as words; a British sailor was added to the supporters of the Arms in 1814.

A promotion to vice-admiral of the white in April 1806 followed, along with the presentation of a sword of honour by the House of Assembly of Jamaica, while his naval feats were acknowledged with several honours, including a sword of honour by the corporation of the City of London. A great dinner was also held in his honour as the Mansion House. On his return to England, Duckworth was granted a substantial pension of £1,000 from the House of Commons, and the freedom of the city of London.

Santo Domingo was the last significant fleet action of the Napoleonic Wars which, despite negative claims made about his personality, displayed Duckworth’s understanding of the role of naval strategy in the overall war by securing for Britain mastery of the sea, and thus having sea-oriented mentality having placed a British fleet in the right strategic position. Duckworth also displayed the willingness of accept changing tactics employed by Nelson, and maintained the superiority of British naval gunnery in battle.

Duckworth was appointed second in command of the Mediterranean Fleet in 1805 primarily on consideration by the Admiralty of having a senior officer in the forthcoming operations with the Imperial Russian Navy. Sailing in the 100-gun first-rate HMS Royal George with eight ships of the line and four smaller vessels, he arrived at the island of Tenedos with orders to take possession of the Ottoman fleet at Constantinople, thus supporting Dmitry Senyavin’s fleet in the Dardanelles Operation. Accompanying him were some of the ablest Royal Navy officers such as Sidney Smith, Richard Dacres and Henry Blackwood but he was in doubt of having the capability to breach the shore batteries and reach the anchored Ottoman fleet. Aware of Turkish efforts to reinforce the shore artillery, he nevertheless took no action until 11 February 1807 and spent some time in the strait waiting for a favourable wind. In the evening of the same day Blackwood’s ship, HMS Ajax accidentally caught fire while at anchor off Tenedos, and was destroyed, although her captain and most of the crew were saved and redistributed among the fleet. Finally on 19 February at the Action at Point Pisquies (Nagara Burun), a part of the British force encountered the Ottoman fleet which engaged first. One 64-gun ship of the line, four 36-gun frigates, five 12-gun corvettes, one 8-gun brig, and a gunboat were forced ashore and burnt by the part of the British fleet.

The British fleet consisted of HMS Standard, under Captain Thomas Harvey, HMS Thunderer, under Captain John Talbot, HMS Pompee, under flag captain Richard Dacres, and HMS Repulse, under Captain Arthur Kaye Legge, as well as the frigate HMS Active, under Captain Richard Hussey Mowbray, under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir Sidney Smith, commanding the rear division. They took one corvette and one gunboat, and the flags of the Turkish Vice-Admiral and Captain Pasha in the process, with adjacent fortifications destroyed by landing parties from HMS Thunderer, HMS Pompée, and HMS Repulse, while its 31 guns were spiked by the marines. The marines were commanded by Captain Nicholls of HMS Standard who had also boarded the Turkish ship of the line. There were eight 32 lb and 24 lb brass guns and the rest firing marble shot weighing upwards of 200 pounds. On 20 February the British squadron under Duckworth, having joined Smith with the second division of ships under command of Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Louis, reached the Ottoman capital, but had to engage in fruitless negotiations with the Sultan’s representatives, advised by Napoleon’s ambassador Sébastiani, and with the accompanying British ambassador Charles Arbuthnot and Russian plenipotentiary Andrey Italinski, the latter being carried aboard on HMS Endymion, under the command of Captain Thomas Bladen Capel, due to the secret instructions that were issued as part of his orders for the mission, and therefore losing more time as the Turks played for time to complete their shore batteries in the hope of trapping the British squadron.

Smith was joined a week later by Duckworth, who observed the four bays of the Dardanelles lined with five hundred cannon and one hundred mortars as his ships passed towards Constantinople. There he found the rest of the Turkish fleet of twelve ships of the line and nine frigates, all apparently ready for action in Constantinople harbour. Exasperated by Turkish intransigence, and not having a significant force to land on the shore, Duckworth decided to withdraw on 1 March after declining to take Smith’s advice to bombard the Turkish Arsenal and gunpowder manufacturing works. The British fleet was subjected to shore artillery fire all the way to the open sea, and sustaining casualties and damage to ships from 26-inch calibre (650 mm) guns firing 300-800 pound marble shot.

Though blamed for indecisiveness, notably by Thomas Grenville, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Duckworth announced that

I must, as an officer, declare to be my decided opinion that, without the cooperation of a body of land forces, it would be a wanton sacrifice of the squadrons to attempt to force the passage

After his departure from Constantinople, he commanded the squadron protecting transports of the Alexandria expedition of 1807, but that was forced to withdraw after five months due to lack of supplies. Duckworth summed up this expedition, in reflection on the service of the year by commenting that

Instead of acting vigorously in either one or the other direction, our cabinet comes to the miserable determination of sending five or six men-of-war, without soldiers, to the Dardanelles, and 5000 soldiers, without a fleet, to Alexandria.

Soon after, he married again, on 14 May 1808 to Susannah Catherine Buller, a daughter of William Buller, the Bishop of Exeter. They had two sons together before his death, she survived him, dying on 27 April 1840.

Duckworth’s career however did not suffer greatly, and in 1808 and 1810 he went on to sail in HMS San Josef and HMS Hibernia, some of the largest first-rates in the Royal Navy, as commander of the Channel Fleet, One of the least pleasant duties in his life was his participation in the court-martial of Admiral Lord Gambier, after the Battle of the Basque Roads.

Probably because he was thought of as irresolute and unimaginative, on 26 March 1810 Duckworth was appointed Governor of Newfoundland and Commander-in-Chief of the Canadian squadron’s three frigates and eight smaller vessels. Although this was a minor command in a remote station spanning from Davis Strait to the Gulf of St Lawrence, he also received a promotion to admiral of the blue, flying his flag aboard the 50-gun HMS Antelope.

While serving as Governor he was attacked for his arbitrary powers over the territory, and retaliated against the pamphleteer by disallowing his reappointment as surgeon of the local militia unit, the Loyal Volunteers of St John, which Duckworth renamed the St John’s Volunteer Rangers, and enlarged to 500 officers and militiamen for the War of 1812 with the United States.

Duckworth also took an interest in bettering relationship with the local Beothuk Indians, and sponsored Lieutenant David Buchan’s expedition up the Exploits River in 1810 to explore the region of the Beothuk settlements.

As the governor and station naval commander, Duckworth had to contend with American concerns over the issues of “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights.” His orders and instructions to captains under his command were therefore directly concerned with fishing rights of US vessels on the Grand Banks, the prohibition of United States trade with British colonials, the searching of ships under US flag for contraband, and the impressment of seamen for service on British vessels. He returned to Portsmouth on 28 November in HMS Antelope after escorting transports from Newfoundland.

On 2 December 1812, soon after arriving in Devon, Duckworth resigned as governor after being offered a parliamentary seat for New Romney on the coast of Kent. At about this time he found out that his oldest son George Henry had been killed in action while serving in the rank of a Colonel with the Duke of Wellington, during the Peninsular War. George Henry had been killed at the Battle of Albuera at the head of the 48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot. Sir John was created a baronet on 2 November 1813, adopting a motto Disciplina, fide, perseverantia (Discipline, fidelity, perseverance), and in January 1815 was appointed Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth 45 miles from his home; a post considered one of semi-retirement by his successor, Lord Exmouth. However, on 26 June that year it became a centre of attention due to the visit by HMS Bellerophon bearing Napoleon to his final exile, with Duckworth being the last senior British officer to speak with him before his departure on board HMS Northumberland.

Duckworth died at his post on the base in 1817 at 1 o’clock, after several months of illness; after a long and distinguished service with the Royal Navy. He was buried on 9 September at the church in Topsham, where he was laid to rest in the family vault, with his coffin covered with crimson velvet studded with 2,500 silvered nails to resemble a ship’s planking.

The Weekly Regency Post

A play upon The Morning Post that was published in the Regency Era. A newspaper owned by R. Tattersall and His Royal Highness, Prince George.

This is a weekly wrap-up of posts from various sources who write regency posts brought to you on a Sunday.

Visit at The Weekly Regency Post