D.W. Wilkin's Blog, page 168

November 27, 2014

A Trolling we Will Go Omnibus: The first three Fantasy stories of Humphrey and Gwendolyn

A Trolling We Will Go Omnibus:The Early Years Not only do I write Regency and Romance, but I also have delved into Fantasy.

The Trolling series, (the first three are in print) is the story of a man, Humphrey. We meet him as he has left youth and become a man with a man’s responsibilities.

We follow him in a series of stories that encompass the stages of life. We see him when he starts his family, when he has older sons and the father son dynamic is tested.

We see him when his children begin to marry and have children, and at the end of his life when those he has loved, and those who were his friends proceed him over the threshold into death.

All this while he serves a kingdom troubled by monsters. Troubles that he and his friends will learn to deal with and rectify.

Here are the first three books together as one longer novel.

A Trolling We Will Go, Trolling Down to Old Mah Wee and Trolling’s Pass and Present.

Available in a variety of formats.

For $6.99 you can get this fantasy adventure.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook

The stories of Humphrey and Gwendolyn. Published separately in: A Trolling we Will Go, Trolling Down to Old Mah Wee and Trollings Pass and Present.

These are the tales of how a simple Woodcutter and an overly educated girl help save the kingdom without a king from an ancient evil. Long forgotten is the way to fight the Trolls.

Beasts that breed faster than rabbits it seems, and when they decide to migrate to the lands of humans, their seeming invulnerability spell doom for all in the kingdom of Torahn. Not only Torahn but all the human kingdoms that border the great mountains that divide the continent.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

November 26, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-John Emery (English Actor)

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

John Emery (English Actor)

1777–1822

Emery was born at Sunderland, 22 September 1777, and obtained a rudimentary education at Ecclesfield in the West Riding of Yorkshire. His father, Mackle Emery (died 18 May 1825), was a country actor, and his mother, as Mrs. Emery, sen., appeared 6 July 1802 at the Haymarket Theatre as Dame Ashfield in Morton’s Speed the Plough, and subsequently played at Covent Garden Theatre.

Emery was brought up for a musician, and when twelve years of age was in the orchestra at the Brighton Theatre. At this house he made his first appearance as Old Crazy in the farce of Peeping Tom by O’Keeffe.’ John Bernard says that in the summer of 1792 Mr. and Mrs. Emery and their son John, a lad of about seventeen, who played a fiddle in the orchestra and occasionally went on in small parts, were with him at Teignmouth, again at Dover, where young Emery played country boys, and again in 1793 at Plymouth. Bernard claims to have been the means of bringing Emery on the stage, and tells an amusing story concerning the future comedian. After playing a short engagement in Yorkshire with Tate Wilkinson, who predicted his success, he was engaged to replace T. Knight at Covent Garden, where he was first seen, 21 September 1798, as Frank Oatland in Morton’s A Cure for the Heart Ache.

Lovegold in Miser and Oldcastle in the Intriguing Chambermaid (both by Fielding), Abel Drugger in the Tobacconist (an alteration by Francis Gentleman of Jonson’s The Alchemist) and many other parts followed. On 13 June 1800 he appeared for the first time at the Haymarket as Zekiel Homespun in The Heir at Law by Colman, a character in the line he subsequently made his own. At Covent Garden, 11 February 1801, he was the original Stephen Harrowby in Colman’s Poor Gentleman.

In 1801 he played at the Haymarket Clod in the Young Quaker of O’Keeffe, Farmer Ashfield in Speed the Plough, and other parts. From this time until his death he remained at Covent Garden, with the exception of playing at the English Opera House, 16 August 1821, as Giles in the Miller’s Maid, a comic opera based on one of the Rural Tales of Bloomfield, adapted by John Davy.

He was the original Dan in Colman’s John Bull, 5 March 1803; Tyke in Morton’s School of Reform, 15 January 1805; Ralph Hempseed in Colman’s X Y Z, 11 December 1810; Dandie Dinmont in Guy Mannering, 12 March 1816, and Ratcliff in the Heart of Midlothian, 17 April 1819, (both by Terry, based on novels by his friend Sir Walter Scott). His last performance was Edie Ochiltree in The Antiquary (again by Terry, based on Scott), 29 June 1822.

On 25 July 1822 he died of inflammation of the lungs in Hyde Street, Bloomsbury, and was buried 1 August in a vault in St. Andrew’s, Holborn. On 5 August 1822, under the patronage of the Duke of York, several plays and a concert, were given at Covent Garden for the benefit of Emery’s aged parents, widow and seven children. An address by Colman was spoken by Bartley, and a large sum was realised.

No less than seven portraits of him in various characters, of which four are by De Wilde, and one presenting him together with Liston, Mathews, and Blanchard, by Clint, are in the Mathews collection at the Garrick Club.

He had considerable powers of painting, and exhibited between 1801 and 1817 nineteen pictures, chiefly sea pieces, at the Royal Academy. He was a shrewd observer, an amusing companion, and a keen sportsman, very fond of driving four-in-hand. Unfortunately he drank to excess, and was never so happy as when in the society of jockeys and pugilists.

A Jane Austen Sequel: Colonel Fitzwilliam’s Correspondence

Colonel Fitzwilliam’s Correspondence For your enjoyment, one of the Regency Romances I published.

It is available for sale and I hope that you will take the opportunity to order your copy.

For yourself or as a gift. It is now available in a variety of formats.

For just a few dollars this Regency Romance can be yours for your eReaders or physically in Trade Paperback.

Visit the dedicated Website

Barnes and Noble for your Nook or in Paperback

Amazon for your Kindle or in Trade Paperback

Witnessing his cousin marry for love and not money, as he felt destined to do, Colonel Fitzwilliam refused to himself to be jealous. He did not expect his acquaintance with the Bennet Clan to change that.

Catherine Bennet, often called Kitty, had not given a great deal of thought to how her life might change with her sisters Elizabeth and Jane becoming wed to rich and connected men. Certainly meeting Darcy’s handsome cousin, a Colonel, did not affect her.

But one had to admit that the connections of the Bingleys and Darcys were quite advantageous. All sorts of men desired introductions now that she had such wealthy new brothers.

Kitty knew that Lydia may have thought herself fortunate when she had married Wickham, the first Bennet daughter to wed. Kitty, though, knew that true fortune had come to her. She just wasn’t sure how best to apply herself.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

November 25, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Sir George Seymour

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Sir George Seymour

17 September 1787 – 20 January 1870

George Seymour

Sir George Seymour was the eldest son of Vice-Admiral Lord Hugh Seymour (himself a son of Francis Seymour-Conway, 1st Marquess of Hertford) and Anna Horatia Waldegrave (a daughter of James Waldegrave, 2nd Earl Waldegrave) and entered the Royal Navy in 1797.

In 1806, he took command of Kingfisher and sailed her back to Britain. Promoted to Captain later that year, he was given command of HMS Aurora.

He captained HMS Pallas during the Battle of Basque Roads and HMS Fortunée and HMS Leonidas during the War of 1812. For his part in the latter war, he was appointed a CB in 1815 (alongside many other Captains) and a KCH in 1831 (and later a GCH in 1834). In 1841 he was appointed Third Naval Lord.

He was appointed Commander-in-Chief Pacific Station in 1844, Commander-in-Chief North America and West Indies Station in 1851 and Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth in 1856.

He was appointed a GCB in 1860 and promoted to Admiral of the Fleet in 1866.

He died in January 1870, eight months before his first cousin once removed, the 4th Marquess of Hertford; had he survived him, he would have succeeded to the title. His son Francis succeeded as the 5th Marquess in August.

In 1811, Seymour had married Georgiana Mary Berkeley (a daughter of Sir George Berkeley) and they had eight children:

Francis George Hugh (1812–1884), succeeded cousin as Marquess of Hertford in 1870.

George Henry (1818–1869), Lord of the Admiralty.

Laura Williamina (1832–1912), married Queen Victoria’s nephew Prince Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (eventually becoming known as Princess Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg).

William Frederick Ernest (1838–1915), General

Georgina Isabella (d. 1848), married Charles Corkran of Long Ditton.

Horatia Louisa (d. 1829), died unmarried.

Emily Charlotte (d. 1892), married William Ormsby-Gore, 2nd Baron Harlech.

Matilda Horatia (d. 1916), married Lt-Col Cecil Rice.

Space Opera Books presents ECO Agents:Save The Planet a Young Adult Adventure

First ECO Agents book available

Those who follow me for a long time know that I also write in other fields aside from Regency Romance and the historical novels I do.

A few months ago, before the end of last year and after 2011 NaNoWriMo, (where I wrote the first draft of another Regency) I started work on a project with my younger brother Douglas (All three of my brothers are younger brothers.)

The premise, as he is now an educator but once was a full on scientist at the NHI and FBI (Very cloak and dagger chemistry.) was that with the world having become green, and more green aware every week, why not have a group of prodigies, studying at a higher learning educational facility tackle the ills that have now begun to beset the world.

So it is now released. We are trickling it out to the major online channels and through Amazon it will be available in trade paperback. Available at Amazon for your Kindle, or your Kindle apps and other online bookstores. For $5.99 you can get this collaboration between the brothers Wilkin. Or get it for every teenager you know who has access to a Kindle or other eReader.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook Smashwords iBookstore for your Apple iDevices Amazon for your Kindle

Five young people are all that stands between a better world and corporate destruction. Parker, Priya, JCubed, Guillermo and Jennifer are not just your average high school students. They are ECOAgents, trusted the world over with protecting the planet.

Our Earth is in trouble. Humanity has damaged our home. Billionaire scientist turned educator, Dr. Daniel Phillips-Lee, is using his vast resources to reverse this situation. Zedadiah Carter, leader of the Earth’s most powerful company, is only getting richer, harvesting resources, with the aid of not so trustworthy employees.

When the company threatens part of the world’s water supply, covering up their involvement is business as usual. The Ecological Conservation Organization’s Academy of Higher Learning and Scientific Achievement, or simply the ECO Academy, high in the hills of Malibu, California overlooking the Pacific Ocean, is the envy of educational institutions worldwide.

The teenage students of the ECO Academy, among the best and brightest the planet has to offer, have decided they cannot just watch the world self-destruct. They will meet this challenge head on as they begin to heal the planet.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

November 24, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-John Bell (Folk Music)

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

John Bell (Folk Music)

1783 – 1864

John Bell was born in 1783, it is thought in Newcastle, and was a printer, sometime surveyor, collector (or probably more correctly, an obsessive hoarder) of anything and everything, but particularly to do with the music that was popular at the time.

Bell followed the precedent set by Joseph Ritson, an eminent and eccentric scholar from Stockton, was probably one of (if not the) first to set down some of the local dialect songs popular in the day. He published a series of “Northern Garlands” in 1793 which contained among others “The Collier’s Rant”, “The Keel Row”, “Bobby Shaftoe” and “Elsie Marle.” Bell followed close behind, but adopted a more organised and professional approach.

His many sources ranged from the rich and famous down to the characters of the Newcastle Quayside. His book “Rhymes of Northern Bards” was published in 1812. It included “Bobby Shaftoe”, “Buy Broom Besoms”, “Water of Tyne”, “Dollia”, but with very few mining themed songs except “The Collier’s Pay Week”, ”Footy Agin the Wall” and “Byker Hill”. There appears to be no logic or method behind the selection of the lyrics, except that they were all local dialect, as it covers a wide range of topics including politics, history, crimes, local characters, work and pleasure. Bell had added notes which two hundred years later are historically very interesting and important.

Bell died in 1864.

Space Opera Books Presents A Trolling We Will Go Omnibus:The Latter Years

A Trolling We Will Go Omnibus:The Latter Years

Not only do I write Regency and Romance, but I also have delved into Fantasy.

The Trolling series, is the story of a man, Humphrey. We meet him as he has left youth and become a man with a man’s responsibilities. He is a woodcutter for a small village. It is a living, but it is not necessarily a great living. It does give him strength, muscles.

We follow him in a series of stories that encompass the stages of life. We see him when he starts his family, when he has older sons and the father son dynamic is tested.

We see him when his children begin to marry and have children, and at the end of his life when those he has loved, and those who were his friends proceed him over the threshold into death.

All this while he serves a kingdom troubled by monsters. Troubles that he and his friends will learn to deal with and rectify.

Here are the last two books together as one longer novel.

Trolling, Trolling, Trolling Fly Hides! and We’ll All Go a Trolling.

Available in a variety of formats.

For $5.99 you can get this fantasy adventure.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook

The stories of Humphrey and Gwendolyn. Published separately in: Trolling, Trolling, Trolling Fly Hides! and We’ll All Go a Trolling. These are the tales of how a simple Woodcutter who became a king and an overly educated girl who became his queen helped save the kingdom of Torahn from an ancient evil. Now with the aid of their children and their grandchildren.

Long forgotten is the way to fight the Trolls. Beasts that breed faster than rabbits it seems, and when they decide to migrate to the lands of humans, their seeming invulnerability spell doom for all in the kingdom of Torahn. Not only Torahn but all the human kingdoms that border the great mountains that divide the continent.

The Kingdom of Torahn has settled down to peace, but the many years of war to acheive that peace has seen to changes in the nearby Teantellen Mountains. Always when you think the Trolls have also sought peace, you are fooled for now, forced by Dragons at the highest peaks, the Trolls are marching again.

Now Humphrey is old, too old to lead and must pass these cares to his sons. Will they be as able as he always has been. He can advise, but he does not have the strength he used to have. Nor does Gwendolyn back in the Capital. Here are tales of how leaders we know and are familiar with must learn to trust the next generation to come.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

November 23, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Charles Compton Cavendish 1st Baron Chesham

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Charles Compton Cavendish 1st Baron Chesham

28 August 1793 – 12 November 1863

Charles Compton Cavendish

Charles Compton Cavendish was the fourth son of George Augustus Henry Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington, third son of the former Prime Minister William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, and his wife Lady Charlotte Elizabeth Boyle, daughter of the architect Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork. His mother was Lady Elizabeth Compton, daughter of Charles Compton, 7th Earl of Northampton. In 1814, at the age of 21, Cavendish was elected Member of Parliament for Aylesbury, a seat he held until 1818, and later sat for Newtown from 1821 to 1830, for Yarmouth (Isle of Wight) from 1831 to 1832, for East Sussex from 1832 to 1841, for Youghal from 1841 to 1847 and for Buckinghamshire from 1847 to 1857. In 1858 he was raised to the peerage as Baron Chesham, of Chesham in the County of Buckingham.

Lord Chesham married Lady Catherine Susan Gordon, daughter of George Gordon, 9th Marquess of Huntly, in 1814. He died in November 1863, aged 70. He was succeeded in the barony by his son William George Cavendish.

November 22, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Claire Clairmont

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Claire Clairmont

27 April 1798 – 19 March 1879

Clara Mary Jane Clairmont

Claire Clairmont was born in 1798 in Brislington, near Bristol, the second child and only daughter of Mary Jane Vial Clairmont. Throughout her childhood she was known as “Jane”. In 2010 the identity of her father was discovered: John (later Sir John) Lethbridge of Sandhill Park, near Taunton, Somerset. Her mother had identified him as a “Charles Clairmont”, adopting the name Clairmont for herself and her children, to disguise their illegitimacy. It appears that the father of her first child, Charles, was Charles Abram Marc Gaulis, “a merchant and member of a prominent Swiss family, whom she met in Cadiz”.

When she was three years old, Claire (Jane) Clairmont acquired a stepfamily. In December 1801, her mother married a neighbour, William Godwin, the writer and philosopher. This brought the toddler two step-sisters: Godwin’s daughter, Mary (later Mary Shelley), only eight months older than she, and his adopted daughter, Fanny Imlay, a couple of years older. Both of them were the children of Mary Wollstonecraft, who had died some four years before, but whose presence continued to be felt in the household. The family was completed with the birth of a boy to Mary Jane and William, giving Claire Clairmont a younger brother.

All of the children were influenced by Godwin’s radical anarchist philosophical beliefs. Both parents were well-educated and they co-wrote children’s primers on Biblical and classical history. Godwin encouraged all of his children to read widely and give lectures from early childhood.

Mary Jane Godwin was a sharp-tongued woman who often quarrelled with Godwin and favoured her own children over her husband’s daughters. She contrived to send the volatile and emotionally intense Clairmont to boarding school for a time, thus providing her with more formal education than her stepsisters.

Clairmont, unlike Mary Shelley, was fluent in French when she was a teenager and later was credited with fluency in five different languages. However, the girls grew close and remained in contact for the rest of their lives.

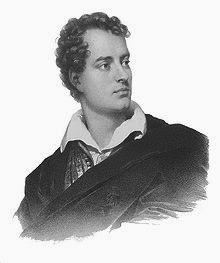

Lord Byron

At sixteen, Clairmont was a lively, voluptuous brunette with a good singing voice and a hunger for recognition. Her home life had become increasingly tense, as her stepfather William Godwin sank deeper into debt and her mother’s relations with Godwin’s daughter Mary became more strained. Clairmont aided her stepsister’s clandestine meetings with Percy Bysshe Shelley, who had professed a belief in free love and soon left his own wife and two small children to be with Mary. When Mary ran away with Shelley in July 1814, Clairmont went with them. Clairmont’s mother traced the group to an inn in Calais, but couldn’t make the girl go home with her. Godwin needed the financial assistance that the aristocratic Shelley could provide.

Clairmont remained in the Shelley household in their wanderings across Europe. The three young people traipsed across war-torn France, into Switzerland, fancying themselves like characters in a romantic novel, as Mary Shelley later recalled, but always reading widely, writing, and discussing the creative process. On the journey, Clairmont read Rousseau, Shakespeare, and the works of Mary’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft.

“What shall poor Cordelia do – Love & be silent,” Clairmont wrote in her journal while reading King Lear. “Oh [th]is is true – Real Love will never [sh]ew itself to the eye of broad day – it courts the secret glades.” Clairmont’s emotions were so stirred by Cordelia that she had one of her “horrors,” a hysterical fit, Mary Shelley recorded in her own journal entry for the same day. Clairmont, who was surrounded by poets and writers, also made her own literary attempts. During the summer of 1814, she started a story called “The Idiot,” which has since been lost. In 1817-1818, she wrote a book which Percy Bysshe Shelley tried without success to have published. But though Claire lacked the literary talent of her stepsister and brother-in-law, she always longed to take centre stage. It was during this period that she changed her name from “Jane” to first “Clara” and finally the more romantic-sounding “Claire.”

Any romantic designs Clairmont might have had on Shelley were frustrated initially, but she did bring the Shelleys into contact with Lord Byron, with whom she entered into an affair before he left England in 1816 to live abroad. (A year marked by agricultural failures and widespread European famine, but also of significant literary advances as the Godwin-Shelley-Byron circle holed up indoors, 1816 would later be known as the “year without a summer”.) Clairmont had hopes of becoming a writer or an actress and wrote to Byron asking for “career advice” in March 1816, when she was almost eighteen. Byron was a director at the Drury Lane Theatre. Clairmont later followed up her letters with visits, sometimes with her stepsister Mary Godwin, whom she seemed to suggest Byron might also find attractive. “Do you know I cannot talk to you when I see you? I am so awkward and only feel inclined to take a little stool and sit at your feet,” Clairmont wrote to Byron. She “bombarded him with passionate daily communiques” telling him he need only accept “that which it has long been the passionate wish of my heart to give you”. She arranged for them to meet at a country inn. Byron, in a depressed state after the break-up of his marriage to Annabella Milbanke and scandal over his relationship with his half-sister Augusta Leigh, made it very clear to Clairmont before he left that she would not be a part of his life. Clairmont, on the other hand, was determined she would change his mind. She convinced Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley, that they should follow Byron to Switzerland, where they met him and John William Polidori (Byron’s personal physician) at the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva. It is unknown whether or not Clairmont knew she was pregnant with Byron’s child at the commencement of the trip, but it soon became apparent to both her travelling companions and to Byron not long after their arrival at his door. At first he maintained his refusal of Clairmont’s companionship and allowed her to be in his presence only in the company of the Shelleys; later, they resumed their sexual relationship for a time in Switzerland. Clairmont and Mary Shelley also made fair copies of Byron’s work-in-progress, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, which he was in the process of writing.

Clairmont was the only lover, other than Caroline Lamb, whom Byron referred to as a “little fiend.” Confessing the affair in a letter to his half-sister Augusta Leigh, Byron wrote

What could I do? — a foolish girl — in spite of all I could say or do — would come after me — or rather went before me — for I found her here … I could not exactly play the Stoic with a woman — who had scrambled eight hundred miles to unphilosophize me.”

He referred to her also in the following manner, in a letter to Douglas Kinnaird (20 January 1817):

“[Claire Clairmont] You know–& I believe saw once that odd-headed girl—who introduced herself to me shortly before I left England—but you do not know—that I found her with Shelley and her sister at Geneva—I never loved her nor pretended to love her—but a man is a man–& if a girl of eighteen comes prancing to you at all hours of the night—there is but one way—the suite of all this is that she was with child–& returned to England to assist in peopling that desolate island…This comes of “putting it about” (as Jackson calls it) & be dammed to it—and thus people come into the world.”

Clairmont was to say later that her relationship with Byron had given her only a few minutes of pleasure, but a lifetime of trouble.

The group left Byron in Switzerland at the end of the summer and returned to England. Clairmont took up residence in Bath and in January 1817 she gave birth to a daughter, Alba, whose name was eventually changed to Allegra. Throughout the pregnancy, Clairmont had written long letters to Byron, pleading for his attention and a promise to care for her and the baby, sometimes making fun of his friends, reminding him how much he had enjoyed making love to her, and sometimes threatening suicide. Byron, who by this time hated her, ignored the letters. The following year, Clairmont and the Shelleys left England and journeyed once more to Byron, who now resided in Italy. Clairmont felt that the future Byron could provide for their daughter would be greater than any she herself would be able to grant the child and, therefore, wished to deliver Allegra into his care.

Upon arriving in Italy, Clairmont was again refused by Byron. He arranged to have Allegra delivered to his house in Venice and agreed to raise the child on the condition that Clairmont keep her distance from him. Clairmont reluctantly gave Allegra over to Byron.

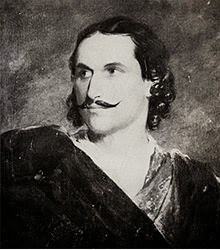

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Clairmont may have been sexually involved with Percy Bysshe Shelley at different periods, though Clairmont’s biographers, Gittings and Manton, find no hard evidence. Their friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg joked about “Shelley and his two wives,” Mary and Claire, a remark that Clairmont recorded in her own journal. Clairmont was also entirely in sympathy, more so than Mary, with Shelley’s theories about free love, communal living, and the right of a woman to choose her own lovers and initiate sexual contact outside marriage. She seemed to conceive of love as a “triangle” and enjoyed being the third. She had also formed a close friendship with Shelley, who called her “my sweet child” and inspired and fed off his work. Mary Shelley’s early journals record several times when Clairmont and Shelley shared visions of Gothic horror and let their imaginings take flight, stirring each others’ emotions to the point of hysteria and nightmares. In October 1814, Shelley deliberately frightened Clairmont by assuming a particularly sinister and horrifying facial expression. “How horribly you look … Take your eyes off!” she cried. She was put to bed after yet another of her “horrors.” Percy Bysshe Shelley described her expression to Mary Shelley as “distorted most unnaturally by horrible dismay”. In the autumn of 1814 Clairmont and Shelley also discussed forming “an association of philosophical people” and Clairmont’s conception of an idealized community in which women were the ones in charge.

Shelley’s poem “To Constantia, Singing” is thought to be about her:

“

Constantia turn!

In thy dark eyes a power like light doth lie

Even though the sounds which were thy voice, which burn

Between thy lips, are laid to sleep:

Within thy breath, and on thy hair

Like odour, it is yet,

And from thy touch like fire doth leap.

Even while I write, my burning cheeks are wet

Alas, that the torn heart can bleed, but not forget!

”

Mary Shelley revised this poem, completely altering the first two stanzas, when she included it in a posthumous collection of Shelley’s works published in 1824.< In Shelley’s “Epipsychidion,” some scholars believe that he is addressing Clairmont as his

“

Comet beautiful and fierce

Who drew the heart of this frail Universe

Towards thine own; till, wrecked in that convulsion

Alternating attraction and repulsion

Thine went astray and that was rent in twain.

”

At the time Percy Shelley wrote the poem, in Pisa, Clairmont was living in Florence, and the lines may reveal how much he missed her.

Mary Shelley

It has occasionally been suggested that Clairmont was also the mother of a daughter fathered by Percy Shelley. The possibility goes back to the accusation by Shelley’s servants, Elise and Paolo Foggi, that Clairmont gave birth to Percy Shelley’s baby during a stay in Naples, where, on 27 February 1819, Percy Shelley registered a baby named Elena Adelaide Shelley as having been born on 27 December 1818. The registrar recorded her as the daughter of Percy Shelley and “Maria” or “Marina Padurin” (possibly an Italian mispronunciation of “Mary Godwin”), and she was baptized the same day as the lawfully begotten child of Percy Shelley and Mary Godwin. It is, however, almost impossible that Mary Shelley was the mother, and this has given rise to several theories, including that the child was indeed Clairmont’s. Claire herself had ascended Mount Vesuvius, carried on a palanquin, on 16 December 1818, only nine days before the date given for the birth of Elena. It may be significant, however, that she was taken ill at about the same time—according to Mary Shelley’s journal she was ill on 27 December—and that her journal of June 1818 to early March 1819 has been lost. In a letter to Isabella Hoppner of 10 August 1821, Mary Shelley, however, stated emphatically that “Claire had no child”. She also insisted:

I am perfectly convinced in my own mind that Shelley never had an improper connexion [sic] with Claire … we lived in lodgings where I had momentary entrance into every room and such a thing could not have passed unknown to me … I do remember that Claire did keep to her bed there for two days—but I attended on her—I saw the physician—her illness was one that she had been accustomed to for years—and the same remedies were employed as I had before ministered to her in England.

The infant Elena was placed with foster parents and later died on 10 June 1820. Byron believed the rumors about Elena and used them as one more reason not to let Clairmont influence Allegra.

Clara Allegra Byron

Clairmont was granted only a few brief visits with her daughter after surrendering her to Byron. When Byron arranged to place her in a Capuchin convent in Bagnacavallo, Italy, Clairmont was outraged. In 1821, she wrote Byron a letter accusing him of breaking his promise that their daughter would never be apart from one of her parents. She felt that the physical conditions in convents were unhealthy and the education provided was poor and was responsible for “the state of ignorance & profligacy of Italian women, all pupils of Convents. They are bad wives & most unnatural mothers, licentious & ignorant they are the dishonour & unhappiness of society … This step will procure to you an innumerable addition of enemies & of blame.” By March 1822 it had been two years since she had seen her daughter. She plotted to kidnap Allegra from the convent and asked Shelley to forge a letter of permission from Byron. Shelley refused her request. Byron’s seemingly callous treatment of the child was further vilified when Allegra died there at age five from a fever some scholars identify as typhus and others speculate was a malarial-type fever. Clairmont held Byron entirely responsible for the loss of their daughter and hated him for the rest of her life. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s death followed only two months later.

Shortly after Clairmont had introduced Shelley to Byron she met Edward John Trelawny, who was to play a major role in the short remaining lives of both poets. After Shelley’s death, Trelawny sent her love letters from Florence pleading with her to marry him, but she was not interested. Still, she remained in contact with him the rest of her long life. Clairmont wrote to Mary Shelley; “He [Trelawny] likes a turbid and troubled life; I a quiet one; he is full of fine feeling and has no principles; I am full of fine principles but never had a feeling (in my life).”

Devastated after Shelley’s death, Mary returned to England. She paid for Clairmont to travel to her brother’s home in Vienna where she stayed for a year, before relocating to Russia, where she worked as a governess from 1825 to 1828. The people she worked for treated her almost as a member of the family. Still, what Clairmont longed for most of all was privacy and peace and quiet, as she complained in letters to Mary Shelley.

Edward John Trelawny

Two Russian men she met commented on her general disdain for the male sex; irritated by their assumption that since she was always falling in love, she would return their affections if they flirted with her, Clairmont joked in a letter to Mary Shelley that perhaps she should fall in love with both of them at once and prove them wrong. She returned to England in 1828, but remained there only a short while before departing for Dresden, where she was employed as a companion and housekeeper. Scholar Bradford A. Booth suggested in 1938 that Clairmont, driven by a need for money, might have been the true author of most of “The Pole,” an 1830 short story that appeared in the magazine The Court Assembly and Belle Assemblée as by “The Author of Frankenstein” Unlike Mary Shelley, Clairmont was familiar with the Polish used in the story. At one point, she thought of writing a book about the dangers that might result from “erroneous opinions” about the relations between men and women, using examples from the lives of Shelley and Byron. She did not make many literary attempts, as she explained to her friend Jane Williams:

But in our family, if you cannot write an epic or novel, that by its originality knocks all other novels on the head, you are a despicable creature, not worth acknowledging.

Clairmont returned to England in 1836 and worked as a music teacher. She cared for her mother when she was dying. In 1841, after Mary Jane Godwin’s death, Clairmont moved to Pisa, where she lived with Lady Margaret Mount Cashell, an old pupil of Mary Wollstonecraft. She lived in Paris for a time in the 1840s. Percy Bysshe Shelley had left her twelve thousand pounds in his will, which she finally received in 1844.

She carried on a sometimes turbulent, bitter correspondence with her stepsister Mary Shelley until she died in 1851. She converted to Catholicism, despite having hated the religion earlier in her life. She moved to Florence in 1870 and lived there in an expatriate colony with her niece, Paulina. Clairmont also clung to memorabilia of Percy Bysshe Shelley. The Aspern Papers by Henry James is based on the narrator’s attempts to gain ownership of these items. She died in Florence on 19 March 1879, at the age of eighty. Clairmont outlived all the members of Shelley’s Circle, except Trelawny and Jane Williams.

November 21, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Henry Vane 2nd Duke of Cleveland

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Henry Vane 2nd Duke of Cleveland

6 August 1788 – 18 January 1864

Henry Vane

Henry Vane 2nd Duke of Cleveland was a British peer, politician and army officer.

Born The Honourable Henry Vane, he was the eldest son of William Vane, Viscount Barnard and his first wife, Katherine, the second daughter of Harry Powlett, 6th Duke of Bolton. In 1792, his father inherited the earldom of Darlington from his father, whereupon Vane became Viscount Barnard.

In 1812, Barnard became Member of Parliament for County Durham, a seat he held until 1815. He was then MP for Winchelsea from 1816–18, Tregony from 1818–26, Totnes from 1826–30, Saltash from 1830–31 and finally for South Shropshire from 1832–42. In 1827, Barnard’s father was promoted in the Peerage as Marquess of Cleveland in 1827 and further as Duke of Cleveland in 1833, whereupon Barnard became Earl of Darlington after the first promotion.

In 1815, Darlington had joined the British Army, eventually rising through the ranks as a lieutenant-colonel in the 75th Regiment of Foot in 1824, major-general in 1851, lieutenant-general in 1857 and finally a general in 1863. In 1842, he inherited his father’s titles and was also appointed a Knight of the Garter that year.

On 18 November 1809, Cleveland had married Lady Sophia Poulett (1785–1859), the eldest daughter of John Poulett, 4th Earl Poulett. He died childless in 1864 and his titles passed to his brother, William.