Remittance Girl's Blog, page 30

August 14, 2012

The Sense of an Ending

Chocolate Cake, All Day, Every Day, Because the Customer is Always Right.

I feel free to appropriate this title because, although it happens to be the title of Julian Barnes’ celebrated piece of literary fiction, he borrowed it from an older, and much wiser book by Frank Kermode: The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction.

Despite the title, Kermode’s book isn’t really about endings. It’s about how we deal with time in fiction, of how we sequence fictional space, of how stories take on certain spaces because of where we choose to start and finish our fictional tales.

One of the hallmarks of literary fiction is the way time is represented. It eschews definitive endings in favour of realism. Because if you ask someone to tell you the story of an event, you will notice that knowing where to begin and end are very problematic. Existentially, it really starts at the moment of self-consciousness and ends with death.

If I were to tell you a small story involving my altercation with a Laotian immigration officer, do I start in the line-up to get my passport stamped for entry? Or on the flight there? Or do I start by telling you why I decided to go to Laos in the first place? Now I have to ask myself the question: is this really just a story about an altercation at immigration, or is it something broader, deeper, wider than that? What did I go to Laos for? Why is it important to get in? Or perhaps this is actually about barriers and how we keep each other out of our respective ‘countries’?

It’s ironic that no critic every complained of too abrupt a beginning. It’s the endings we seem to feel more keenly. Perhaps this is because they are the last words we read and they stay with us. That happens in that last chapter seems to frame the entire story, tint it. Once read, it can never be unread.

Genre fiction has different conventions when it comes to endings. Some, like the Romance genre, have quite overtly proscribed endings. But in detective fiction, the reader can usually expect to have the murder or crime solved. In thrillers, one can be pretty confident that the bad guys will be stopped and brought to justice (or killed).

Hollywood and television drama have played a tremendous role in the kind of endings we define as a ‘good ending’. Over the years, our tastes have been recorded through ‘test audience’ surveys and focus groups. Then those tastes are reflected back to us over and over. It has resulted in an interesting progression in taste training. Recursive and diminishing returns until only one possible ending will ever be acceptable to a majority of viewers. The happy one. The one where everything turns out beautiful. The fairy-tale ending.

No one today would end Gone With The Wind the way it was ended. No one would end The Graduate the way it was ended.

And I’ll put money on it. If they remade the Titanic (I’m sure they will), Leo will live.

You think I’m exaggerating? Okay, let’s play a game.

I’m a market researcher helping to start a new food product.

What’s your very favorite food?

Excellent. We’re going to make that! Do you want it grilled, fried or poached?

The grilled and fried votes are kind of split down the middle.

Fine, we’re going to make both. You’ll get a choice!

Until it becomes clear that a slightly higher percentage of people like it grilled. Then we’ll discontinue the fried type.

Now, you’re going to eat grilled * everyday, because that’s what you said your favorite was.

Remember: food companies aren’t in the business of making food, they’re in the business of making money. Hollywood is spending $159 Million on a film, they aren’t going to take a change on an ending the majority of people don’t say is their favorite ending. They’re going to go for the one every one likes.

Always.

Forever.

Because they’re not in the business of entertaining you. They’re in the business of making money. And so are publishers. And, I’m sad to say, a lot of authors.

You’re going to get exactly what you want, exactly the way you like it… FOREVER.

And you deserve exactly what you get because

YOU GET WHAT YOU WANT, ALL DAY, EVERY DAY!!!!

The only other possibility is that you don’t really get an ending at all, because that way they can sell you a sequel.

God, we’ve turned the world to shit.

August 8, 2012

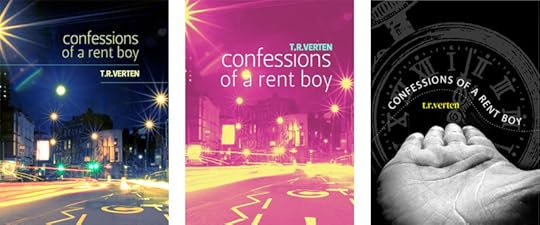

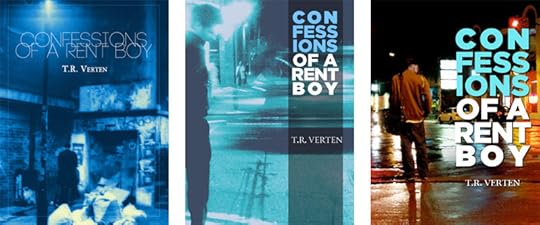

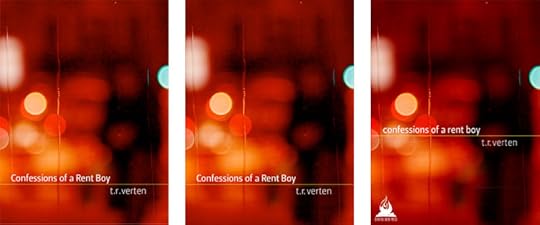

Cover Design for T.R. Verten – A Co-operative Working Model #bookcovers

T.R. Verten is a novelist with whom I had the pleasure of sharing a publisher – Republica Press. As publishers change, covers must be changed as well, because the cover is IP that has usually been paid for and is owned by the publisher, not by the author. I asked T.R. to allow me to have a go at designing a new cover for the novel “Confessions of a Rent Boy.” We used a combination of GChat and email to show things back and forth to each other. I wanted to get a sense of what was good about the original design, and what was lacking. Also a preference for fonts, colours, etc. T.R. graciously allowed me to have a go and, even more graciously, has written up a description of the process of working together with me to develop something that represented the spirit of the story, but would also stand out amidst the thousands of other books out there.

Original Cover

The original design was a stock photo with added text, which contained some of the elements I wanted, but had a pretty generic appearance. After we talked, RG took her cue from the aspects of that original cover that I liked: the long-exposure lights, the feeling of isolation. I wanted the cover to have the feel you get after being out all night partying and waiting for the first bus in the early morning hours.

The first set of covers (5,6,7) didn’t really resonate with me, even though the streetscape they portrayed had the right kind of vibe.

I much preferred the one with the man standing against the backdrop of an urban street in options 2 and 3, and the blue-toned cover was in the running to be one of the the final two. In the end, however, I decided that the solitary figure might actually confuse the issue, making the protagonist out to be a street prostitute, rather than simply a loner. Cover one gave off the same sort of impression, and was almost too seedy.

When I saw the abstract cover, though, I knew it was the right choice. The colors were rich and saturated, the pattern on the glass almost reminded me of tears. Though the book is erotica, it is suffused with sadness. The blue cover with a lone figure portrays a solitary man, whereas the cover I ultimately chose places the viewer in the protagonist’s place. Like the best writing, it shows rather than tells.

For my part, I’m really happy with the cover T.R. Verten chose. There’s a very nice semiotic contrast of the heat of the red tones and the cool of the drips of water. I like the ghostly lone figure of the protagonist, unfocused and waiting to be interpreted by the reader. It speaks to me of being terribly lonely in the midst of a crowded city. In the final (far right version) I lowercased all the typography as requested, and agreed that this really spoke to it being a very 21st century story, with aspects of pragmatism and alienation.

But mostly, I hope it will really attract the reader’s eye. It will pop off the shelf or off a webpage and intrigue the potential reader, while allowing them the pleasures of anticipating unknown and yet somehow familiar landscapes.

August 5, 2012

Chip Kidd on Book Covers

August 3, 2012

Who Do You Write For? Are we simply producers of product? Can I get a refund?

THE READER, by Fragonard, 1732-1806

This question should haunt every writer. Certainly, there is no writing course in the world that doesn’t confront students with it. It seems like an easy one to answer, but it has levels of complexity that, for the most part, only get discussed within their own, embattled spheres.

There is, philosophically, the overarching issue of the writer-text-reader relationship. The obligations of a writer to their readership was examined in many ways over the 20th Century. By the Aestheticists, all the way to the Post-Modernists, it has been a thoroughly chewed subject. I don’t want to list all the various theories – but here’s a good starting place if you’re interested.

Then, of course, there is the commercial sphere. It’s been important, in recent years to proclaim loudly and passionately that you write for your reading audience. It conforms well with the concept of fiction as ‘product’ and writers as ‘manufacturers’ who supply their ‘customers’ with the products they need.

But beyond all that, there is the very personal, very pragmatic reality for most writers of balancing genre expectations with their own creative impulses. And here, one can only speak for oneself. Looking back at the answers given by the writers who generously participated in my Other Voices, Other Genres series, it becomes clear that many writers write for themselves first. And this makes sense. We’re also the ‘first’ reader of any given work.

I spent a lot of time in the theoretical sphere, absorbing various understandings of ‘audience’ and ‘writerly’ reading and ‘open textedness’. And although I learned a lot, it has never been knowledge I could absorb and apply fully as a writer. Admittedly, both Barthes and Eco have had a very strong influence on the way I began to conceive of my ‘reader’. But when I actually sit down to write, I don’t consciously keep that theoretical understanding at the forefront of my mind. I do suspect, however, that it has subtly informed how I ‘address’ the reader in my writing.

I find the second sphere simplistic and degrading. I don’t think there is anything wrong with selling books or appealing to an audience, but I’m disturbed by the spectre of such a transactional relationship between reader and text. It is a model that benefits the retailers at the expense of both readers and writers. My relationship with the books and writers I have loved was far more nuanced and equitable than a ‘buyer & seller’ association. As much as I do believe that the reader plays an integral part in how any give story comes alive, I do acknowledge that the dialogue has been initiated with the writer’s proposition of a story. I prefer to envision the relationship as a cooperative one, a mutual journey. A purely commercial model doesn’t allow for that power distribution. When I put myself, as a reader, into a writer’s hands, I need to trust them. I can’t do that if I believe that the other party is only doing this for money. And, conversely, if I want to take a fictional journey somewhere I have never been before, I cannot demand that the writer deliver my laundry list of literary expectations.

Like any reader, I want to be surprised, but I don’t want to be disappointed. But I can’t be surprised without taking the risk of being disappointed. I have noticed that there has been a steady trend towards readers who would rather simply revisit the familiar than be disappointed. It was really hammered home to me when, after giving a book a very low rating on audible, I got a message from them asking if I’d like to return the book and get my money back.

That really shocked me. There was nothing technically wrong with the file. I simply didn’t LIKE the book. I didn’t warm to the character, the plot didn’t engage me. Why would I want my money back? I took a chance, and I was disappointed. But that doesn’t mean the writer doesn’t deserve to be paid for their book. It simply wasn’t my cup of tea and I won’t be looking for more books from that author. It wasn’t a matter of a mistaken purchase. or an inferior product. It was just a relationship that didn’t work out. You don’t want your money back. You learn and move on.

It did occur to me to wonder, though, why it is that, when the purchase of a book represented a significant outlay of money, both readers and writers have a far more respectful and valued view of each other. Could it be that the $2.99 e-novel has resulted in a $2.99 appreciation for storytelling? It seems a common problem with humans that we seem to value what we pay the most for, and have little respect for what we can purchase cheap or get free. I’m not suggesting we should go back to the days of ‘authorial worship’. But a middle ground might be found, no?

On a personal level, as a writer of stories, I try to write the prose that pleases me. I try to write stories I find interesting and characters who I find compelling. And, I guess, I rely on the fact that there will be readers out there who share my aesthetic. But I’m not willing, as a writer, to put the emotion and craft into my writing for someone whose only expectation is to have a good wank.

My recent interchange on the Guardian Books Blog elicited some interesting commentary: I found this one particularly interesting:

tkmarnell

2 August 2012 10:00PM

Wow, so much hullaballoo over a single sentence, which I didn’t even notice because I skipped the laundry list of titles and prices.

Here’s my take on erotica: its purpose is to titillate. The Google definition (by no means official, but generally representative of popular understanding) is, “Literature or art intended to arouse sexual desire.” If your purpose is not to arouse, but to explore the complications and implications of human mating behavior, it is not erotica. It is a story that happens to have sex…maybe a lot of it. Sex is not such a unique subject that every story that features it is automatically erotica, though nervous booksellers will lump it all together to avoid offending perpetually alarmed parents.

Now, you can’t deny that people who seek out straight-up erotica are looking to be aroused. Do you really think they’re there for the plot and prose, or complex discussions of how the social condemnation of desire impacts the modern man’s psychological makeup? They’re there for the rush. The endorphins. The emotional and physical high of the fantasy. Most don’t even care for the characters; a “he” and “she” will suffice for the purpose (or a “he” and “he,” or “she” and “she,” or two “shes” and a “he” with a cat watching from the doorway…). Conflict in these stories is not an avenue for private reflection and growth, but to build tension that makes the final release more satisfying. Ultimately, no, you don’t need to know the plot; it’s just the framework for the experience readers are after. You could say this about any book, really.

Erotica is what it is. It’s silly to try to justify it in terms of the genres detractors consider more “worthy.” By getting offended by the label of “porn” and insisting that erotica isn’t really about arousal, but all those things that great literary works are “supposed” to be about, you’re essentially agreeing that arousal isn’t a good enough goal on its own. What, exactly, is wrong with porn? Is it too base and obscene for the folks who write “quality” erotica? The message is so mixed it’s making my head spin.(Comment, “Ebooks round up: Fifty Shades of Erotica” Guardian Website, August 1, 2012, http://gu.com/p/39ecm)

What I was being told, if I’m reading this correctly, is that I should shut up and simply write stuff she can get off to, and drop any pretenses of skill, or plot, or characterization. She wants erotica to be porn. She wants erotica writers who believe there is a difference to shut up and put out.

Porn is a different genre of writing. Porn doesn’t require or even benefit from conflict. It doesn’t require characters, it requires stand-ins for the reader to step into and fantasize being. It only requires plot inasmuch as the sexual response could be charted as having a sort of three-act story structure. Writing good porn requires considerable skill. I have tried it and, frankly, I suck at it. You need to really understand that what you’re writing is a roleplay guideline for the reader. No matter what POV it is written in, should have the aura of 2nd Person POV haunting it. It is incredibly open-texted, a guided sexual fantasy experience. And anyone who thinks that is easy to pull off is nuts.

I maintain that erotica/ erotic fiction is different from porn. I know a that there are many erotica writers who disagree with me. I think there are a number of reasons for this.

There is the re-appropriation camp who feel that sexually explicit material of any type should be considered without value judgement. Although I agree with them politically, I do not feel, compelled, as a writer to represent that in my fiction. I’m a writer, not a social activist. Their stance is that if I won’t say that what I write is porn, then I’m saying porn is bad. No. I’m saying I am not skilled at writing porn, and taking a reader to orgasm is not the main motivation behind why I write or what I write. I am a piss poor producer of porn.

Second, there is a reactionary mainstream belief that porn is bad, but erotica is okay. Consequently there are a lot really good porn writers who call themselves erotica writers because their readers don’t like to admit what they’re after is porn. Erotica is ladylike, porn is for perverts. It’s kind of the opposite of the first camp.

What I see is that most erotic fiction writers get caught in the middle. They’re trying to craft a type of fiction that uses desire as a lens through which to tell a wider story. They write about characters whose conflicts are at least partially brought about by their desires, or are coloured by them. Sex, in erotic fiction, is contextualized within the lives and experiences of the character. It informs their definitions of self, and flavours their interactions with other characters in the story. But there has to be a story. There has to be conflict. Otherwise, it’s not erotic fiction.

All this has really led to me forming a much stronger picture of who I write for. I acknowledge that I don’t just write for myself. I do have a reader in mind when I write. It’s a reader who is interested in human complexity, a person who wants to be aroused, but on a less genital and more emotional level. And that requires that the eroticism is contextualized within a story form.

tkmarnell may be right. Perhaps when we speak of D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Anais Nin, Nabokov, etc, we should no longer use the term erotic fiction. Maybe the definition has changed. Maybe is has become a canon with no home.

But the problem with that is that, for literally 90% of my readers, I am an erotic fiction writer. The vast majority of my stories have sex and sexual desire at the very core of the story. It plays a pivotal role in plot and the narrative voice. So I’m not willing to agree with the commenter. I think she really just wants porn, and I don’t think most erotica writers write it.

August 1, 2012

Prigs with Web Hits

This article at at the Guardian made me see red:

Ebooks roundup: Fifty shades of new erotica and roll the dice for a pricePopulist titles tick the genre boxes, publishers get creative with eshort tasters and price-setting takes a new twist

I love how the author manages to get her web-hits by name dropping FSOG while not actually bothering to read any of the books she’s pissing on:

Meanwhile, explicit tales of erotic entanglement are legion as publishers chase the market opened up by the runaway success of Fifty Shades of Grey, still dominating the bestseller chart. This month sees the launch of Beth Kery’s Because You Are Mine, to be published in eight weekly instalments (Headline, ££1.49 each); Destined to Play by Indigo Bloome (HarperCollins, ££1.99); Marina Anderson’s Haven of Obedience (Hachette Digital, £3.99); Diary of a Submissive by Sophie Morgan (Michael Joseph, £2.99); and three collections of erotic short stories by Tobsha Learner titled, with unashamed camp, Quiver, Yearn and Tremble (Hachette Digital, £2.99). The plots involve – well. Do you really need to know the plots?

Yes, Ms Page, we DO REALLY NEED TO KNOW THE PLOTS.

It is the height of hypocrisy, in the digital age, that these literary arbiters will gladly get web-hits from the mention of a best selling erotic novel, but won’t actually stoop to read one.

Here, for what it is worth, was my response:

“The plots involve – well. Do you really need to know the plots?”

Yes, I really need to know the plots. That literary critics have felt it so beneath them to critique erotic fiction has certainly contributed to the sad reality that few writers within the erotic fiction genre have developed the sort of storytelling skills of other fiction genres.

If, as Iain Banks eloquently said, the genre of science fiction examines how humans deal with change, then erotic fiction examines how humans deal with desire. Within those parameters, there is a great deal of scope for theme, story, character and conflict.

Every year, the Bad Sex Awards come along and the Guardian posts yet another article on how sad it is that no one writes sex well in novels. Not terribly surprising — when literary luminaries think it so beneath them to actually read any well-written sex, or can be arsed to critically review novels in which the good sex writing appears.

Sexual desire is a fairly universal experience and yet the literary world is still stuck in the grip of Aristotles’ insistence that no rational thought is possible under its sway. If ever there was an unquestioning, uncritical acceptance of dogma, this has to be it. It’s been 90 years since Lady Chatterly’s Lover was written. Could you please get over it?

There are wonderful stories out there about how humans navigate the storm of desire. Presidents court impeachment, the great and good are brought low by it. And the literary world’s response, for the most part, is to tiptoe around the reality of those tempests like parsimonious prigs picking their way down a shit-strewn alley.

When some adventurous writer doesn’t follow that banal path, it’s labeled ‘porn’. Which only goes to show what sheltered little lives most critics live. Because if you did consume any, you’d be able to tell the difference between porn and erotic fiction: no one in their right puts conflict into porn.

If you are an erotic fiction writer or reader, I urge you to take your digital ass over to the Guardian and give them what for. The attitude is patronizing and the tactic is blatantly opportunistic.

July 30, 2012

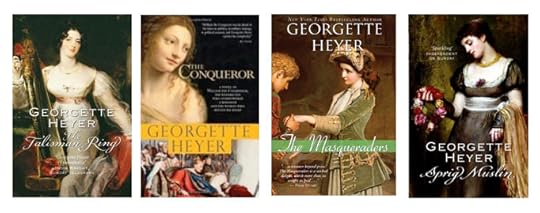

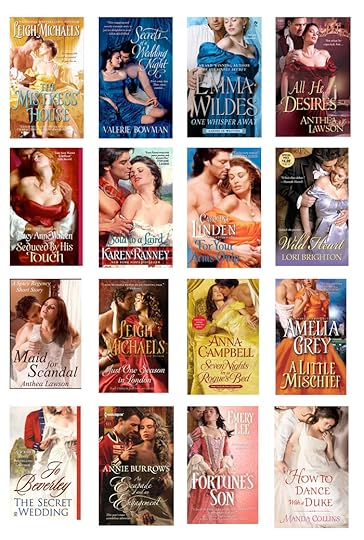

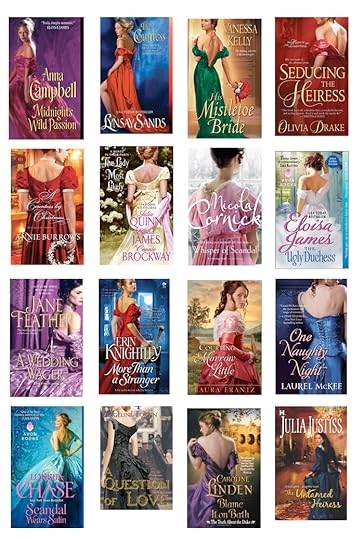

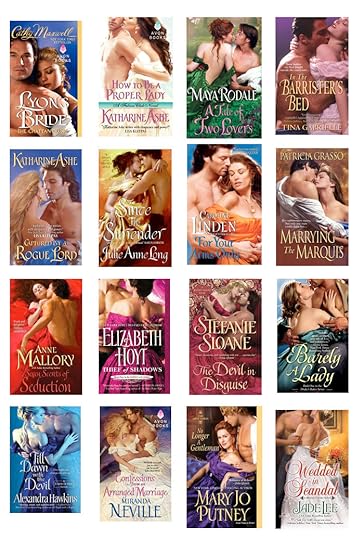

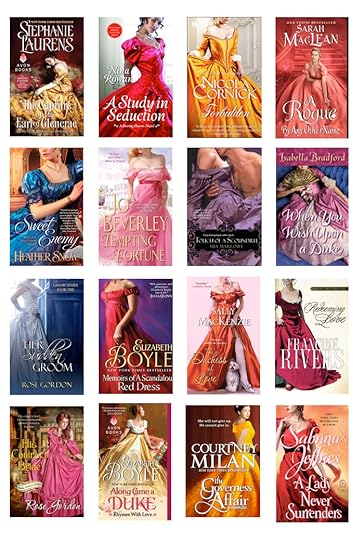

A Market Survey: My Final Plea for Non-Conformity #bookcovers #historicalromance

Can you tell I’m a little OCD? Well, I spent the spare moments of my day surveying the world of historical romance fiction in order to try and construct my last argument for why romance authors should consider breaking out of the ‘typical’ romance cover mold.

I think a huge hurdle with trying to persuade them is that authors don’t see what consumers see. Once they’ve got a cover, they associate it with the contents. They know the book is unique because they’ve bloody read the thing. But a consumer has not.

And to consumers, let me show you what they see. I have identified four distinct cover types:

I call this the ‘look out behind you’ meme

This I call the ‘Talk To My Zipper’ meme

The ‘Pecs Ahoy’ meme

and finally, and most puzzling of all, to me

the ‘It’s the dress, stupid’ meme

The point I’d like to make in all of this is – these are what the shelves look like, ladies. Do you want to conform, or do you want to stand out?

Some notable exceptions were Georgette Heyer, whose covers are always either paintings of the period, or very skilled reproductions

Here are a number of best selling exceptions

July 28, 2012

The Challenge – Redefine the Regency Romance Cover #bookcovers

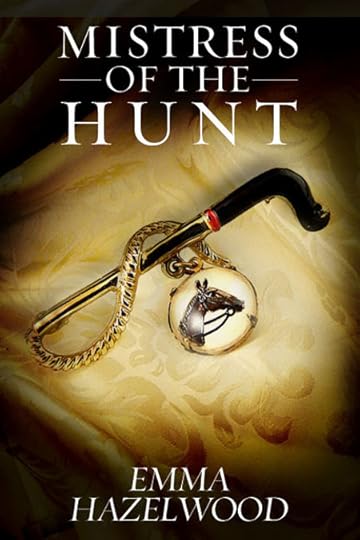

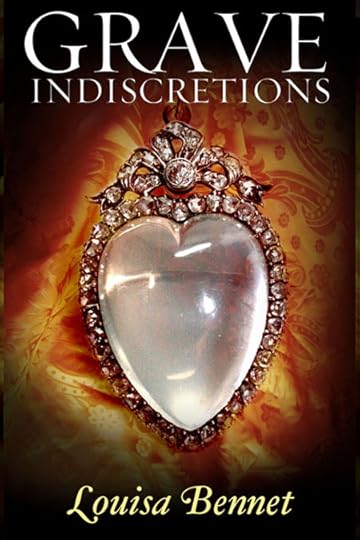

A couple of historical romance authors challenged me to offer an alternative to the ubiquitous ‘girl with a flounce’ covers on most historical romances.

Doing this right would involve paying my father’s old friends in the antique business a visit – I could only work with what I could find lying around on the web. The interesting thing about the early 1800s is that they had some marvelous trinkets – very personal, very intimate items like chatelaines and necessaires for ladies, beautiful toilet sets, ivory carved dance card cases, etc. They also had some wonderful silverware at table, like sugar snips. Plus beautiful textiles. There are also some gorgeous engravings and maps surviving, not to mention outstanding paintings. And, of course, there are surviving English landscape and architecture that is period. So there is a lot to work with, but if I was going to make a living at this, I’d be taking some trains and my SLR and getting a collection of good, relevant stock photography.

Nevertheless, in a pinch, I have taken my cue from Sarah Waters’ delightful book designs, which speak volumes to a later Victorian period. Darkened edges, poignant artifacts, and typography that suits the period. I used Perpetua, Sanbon, and Jensen. All transitional fonts that were first crafted in the late 18th century and early 19th. The items I used were jewelry circa 1830.

Again, they aren’t brilliant covers. But they’re good covers. They’re not cliche, they won’t get lost amidst the frilly women and shirtless men, and no one is going to be able to make snap judgements on what these books contain.

Screw ‘Where’s Wally”. It’s time for ‘Where’s RG?’

My Disaster Cover #bookcovers

After writing the last post, Sandrine Lopez, (@sanpezzers) tweeted and asked if I’d ever had an experience of having to live with a bad cover and would I do a post on it.

I have to confess, this cover is so bad, it has tainted how I feel about the story as a whole. The publisher, who I will not name, did not even send me a jpg of the cover before the ebook was out, so the first I saw of it was when I stumbled across it there, up on Amazon, in all its gory glory. A done deal. I sent them an email saying I was shocked, and got sucking silence.

[image error]

I hope you know, I’m dying a little here, just in the humiliating act of uploading this.

What I’d ask you to do first, is read the story: which is here. Please read it now, because it’s likely to be off the site in about a month.

Now, you can see what happened. The ‘designer’ (whose job title I have put in quotes for reasons I will go into later) either read or was given a verbal synopsis that went like this: “this is a story about a girl who fucks a guy for money. Make a cover.”

It doesn’t embody the setting, the mood, the fact that the protagonist is not a prostitute, or that (puzzlingly) it isn’t an interracial couple. Not only doesn’t it address the theme of the story, which has a real undercurrent of D/s, with money as the instrument of power. It infers that she has the money and the power. Which is the antithesis of the theme. Also, the male in the story is a middle-aged, rather pudgy man, who never gets fully undressed. The one on the cover looks magnificently swarthy, and appears to either be clutching a massive cock, or a gun. I don’t know which one bothers me more.

For many reasons, this cover isn’t just bad, it’s flat out misleading advertising.

Now to the issue of the quotes I used around the word designer. See the icky white halo above her stocking. That’s just unforgivably bad cropping. I understand that designers on a budget have to composite images, but they should learn how to fucking do it properly.

Second, can you read the author name? Was it really necessary to put my name in scrolly script AND have it in a flaming gradient as well?

Don’t mistake this for post-modern challenging typography. This is just a very bad wannabe designer with photoshop filters and too much fucking time on their hands. It’s unforgivable.

Let me be honest, I don’t think that writers are the best designers of their own covers, even when they have the graphics skills to do it. The best cover designs require a little distance from the story – to be able to visualize the bigger picture, not the minutiae. But if I had to sit down and design a cover for this, one of these would be far more appropriate.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

I want to be clear. I’m not saying that any of these are brilliant covers. It took me an hour to source the images and artwork them and add typography to all of them. And I would spend significantly more time on any given book cover. What I’m saying is they would be clearer, more eye-catching and, above all, less misleading to the reader.

I don’t really believe there is a perfect book cover. Text is text and image is image, and by their very nature, one is never going to translate perfectly into the other. It’s why literature and the visual arts exist as separate art-forms. But I think that it is possible to make a cover that doesn’t do actual violence to the contents of a novel, invites the reader in bearing questions, and isn’t humiliating to have to post on your blog.

July 27, 2012

Cover-rage: Why Writers Need to Care about Covers #bookcovers

I had a horrible nightmare last week. I dreamed that my novel was released with a cover featuring a blonde bimbo with fake tits sandwiched between two rambo clones. I could see it so clearly, in all its revoltingly literal, misleading, exploitative glory. The scrolled, wedding-invite font was the last straw. I broke through into consciousness in a pool of sweat, fighting for air, heart racing, with that nauseating sense of incipient doom. And if you think I’m being neurotic, lemme tell ya – it wasn’t fantasy, it was a flashback.

There are very few publishers who will even entertain the notion of including an author’s approval of the cover in a publishing contract. I say ‘very few’ because I don’t know of any, but I’m sure some do exist. But unless you are a massive best-selling author, chances are, it’s not going to happen.

Maybe, because I was a graphic designer at one point, I am more bothered by this than most people. I should just be grateful to get published at all. And yet, I’ve designed my fair share of book covers for other authors, and I know that I’m not the only writer who dreads having the spirit of their work utterly misrepresented by an image that encapsulates nothing but the most literal scene in their story.

Personally, I am a proponent of metaphor and mood when it comes to covers. What I mean by this is that the cover should NOT interpret the work, or close off the meaning of the work for the reader. I have been terribly put off from buying a book because the heroine on the front cover is physically someone I can’t relate to. I just won’t buy the book. And it’s silly, isn’t it? Because the actual novel might be magnificent, but the cover has already solidified the character for me, and I can’t move past it.

Covers should catch the prevailing overall mood of a book. They should trigger questions in the reader, which the text answers. Let me give you an example of three really spectacular book covers:

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

I don’t care what you think of the book, this is a brilliant cover. It doesn’t visualize the story, it visualizes the theme in metaphor. It utilizes a tremendously powerful semiotic image of the apple. We are offered the invitation to taste the fruit of knowledge, dangerous knowledge that will imperil innocence. Also, note the trouble taken on the typography – it went on to identify the whole brand.

All Water’s books have great covers. This one is no different. It situates the story in the past. And it tells us it is a story of women. There is the implication of hard times and struggle. Again, it doesn’t tell you about the story at all. It simply visualizes theme and a mood that prevails through the novel. The choice of font on the title is perfect for the time in which the story is set. As readers, this is an invitation, not a synopsis.

Put your feelings of this book aside. The cover is brilliant.The chill of the blue is in direct contrast to the content of the novel. It sets up an immediate dichotomy. It invites the reader to wonder who the tie belongs to. It uses the image of the tie as a metaphor for economic success, but also social constraint and hints, very subtly, at other, more sexual forms of constraint.

You’ll notice that all these books have objects as their dominant focus, not people. Even the Twilight cover, which has a set of hands cupping the apple, uses the line of the arms as ‘continuance‘ to draw the eye to the apple nestled in the palms. These are effective covers because they DON’T attempt to TELL the story, but to invite the reader into the storyspace. There are no humans for you to either feel you can relate to, or worse, feel alienated from. And this is one of the major problems with a great number of erotic romance covers. Perfect, pretty girls. Fuck, I hate them. And sadly, this has become so much the ubiquitous format for erotic romance, that you only have to glance very quickly at the cover to receive the message of what the book probably contains. Another formulaic story. The sad thing is, many of the stories may NOT be formulaic. They may be brilliant novels, but their cover typifies and calls to mind the very worst assumptions about the genre.

Here’s another set of three, from very successful novels. Just in case you thought I only liked black backgrounds.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Julian Barne’s The Sense of an Ending is not really about endings but the process of them. And the cover is a beautifully metaphoric visualization of this. Dandelions lose themselves in a last hopeful gust before their own ends. The seeds scatter chaotically. The type is tentative and eroded, and the the right hand side appears to be curling into darkness, into the past. It captures the mood of the novel perfectly. Yet gives away nothing.

Cronin’s cover works both as metaphor and as setting. It is the story of a journey through an imagined world. The colours and imagery invite the reader into this new, post-apocalyptic landscape. But it also illustrates the ‘forest from the trees’ adage, which is very relevant to the story’s theme.

We have a fire-red cover to accord with the title. The strands of long blonde hair imply a woman in the story, but also the tangles and twists of the plot.Again, the typography is a homage to post-modernist designers like David Carson and Neville Brody, who believed that slightly illegible text did a better job at engaging the reader, who invests time with the image to decipher it.

I think it is time to stop treating readers like 5-year olds, who need to see exactly what is in the box. A cover should be eye-catching, engaging, and prompt questions, not give answers.

It’s a fucking book cover, not a spoiler.

Now, let’s see how much of a hissy fit I can pull to get something decent for my novel.