MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 177

May 14, 2015

12,300-Year-Old Bone Pendants May be Oldest Artwork Ever Discovered in Alaska

Ancient Origins

Ancient OriginsCarved bone pendants have been found at a prehistoric site in Alaska that may prove to be the very first known examples of artwork in the northern region of North America.

Two pairs of pendants were revealed at the Mead archaeological dig site in the wilderness of the Alaska interior between Fairbanks and Delta Junction. At a recent lecture at the UA Museum of the North, anthropologist Ben Potter from the University of Alaska Fairbanks said of the find, “It made my heart stop when I saw it.”

Detail, prehistoric bone pendants found at the Mead archaeological site in Alaska may be the first examples of artwork in northern North America. Photo credit: Barbara Crass, Shaw Creek Archaeological ResearchPotter has lead the Mead site excavations for the past two years in cooperation with local and regional indigenous organizations. The site has been undergoing annual excavations since at least 2009.

Detail, prehistoric bone pendants found at the Mead archaeological site in Alaska may be the first examples of artwork in northern North America. Photo credit: Barbara Crass, Shaw Creek Archaeological ResearchPotter has lead the Mead site excavations for the past two years in cooperation with local and regional indigenous organizations. The site has been undergoing annual excavations since at least 2009.A student uncovered the tiny bone pendants while working in what is believed to be the location of a hide-covered hut from 12,300 years ago, reports local news website NewsMiner.

Reportedly the pendants were discovered in 2013, but announcements of the finds were held off by researchers until further exploration was done to ensure other artifacts hadn’t been missed. The team has also recovered stone tools and animal bones dating to between 11,820 and 12,200 years ago. A brown bear jawbone was found with its pointy canine teeth removed, presumably to be included as powerful talismans in other jewelry.

Missing from the Mead site are weapon fragments – suggesting the location was used as a base camp rather than a hunting camp.

Two infant graves dating back 11,500 years found in Alaska Oldest and largest concentration of ancient rock art under threat from Australian Government Stone tool unearthed in Oregon may date back 15,800 years or more The pendants are considered samples of sophisticated craftsmanship of their time.

Carved from bone, two of the pendants look like zipper pulls, and the other two resemble stylized fish or bird tails. There is a delicate cross-hatching design on the outer edges of the pendants. Researchers theorized they might have been toggles, buttons for clothing, earrings or pendants, or ornaments.

Upon their discovery, Potter first tried to pinpoint their use by discern their function, how the pieces might have benefited the Ice Age people, and kept them alive. However, the team would soon reconsider the artifacts to be very early artwork.

Potter said, “Art serves as a way to fix social boundaries. ‘This is our group, not yours.’ These could be a way to communicate. They could be the first evidence we have for social boundary maintenance (in high-latitude North America),” writes NewsMiner.

Excavationists work at the Mead site in Alaska where 12,300-year-old pendants have been found. Credit: Ben Potter Barbara Crass, director of Shaw Creek Archaeological Research said of the site in 2014, “Outside of a few beads there’s nothing else that age and artistic in the New World or at least North America.”

Excavationists work at the Mead site in Alaska where 12,300-year-old pendants have been found. Credit: Ben Potter Barbara Crass, director of Shaw Creek Archaeological Research said of the site in 2014, “Outside of a few beads there’s nothing else that age and artistic in the New World or at least North America.”Potter and colleagues have been excavating Mead and the nearby Upward Sun River site and have uncovered the remains of three ice-age child grave sites, and tent areas.

Archaeologists Discover Pre-Contact Native Village in Alaska Ancient Bronze Artifacts in Alaska Reveals Trade with Asia Before Columbus Arrival Ancient Oregon caves may change understanding of human habitation in Americas Researchers are excited about the finds which push back the dating on artworks in northern North America and reveal Ice-Age Alaskan life and craftsmanship. The discoveries at Mead and other prehistoric sites in the Alaskan interior show that not all camps were exclusively for hunting, and early humans of the region devoted some of their time to creating ornaments of cultural and decorative importance.

Featured Image: Bone pendants, seen right, were found at an archaeological dig site in the Alaskan interior. Credit: Ben Potter

Published on May 14, 2015 08:04

History Trivia - English physician Edward Jenner gives the first successful smallpox vaccination

May 14

1264 Barons War: Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, defeated English king Henry III.

1572 Gregory XIII, best known for his calendar reform, was elected pope.

1796 English physician Edward Jenner gave the first successful smallpox vaccination.

1264 Barons War: Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, defeated English king Henry III.

1572 Gregory XIII, best known for his calendar reform, was elected pope.

1796 English physician Edward Jenner gave the first successful smallpox vaccination.

Published on May 14, 2015 01:00

May 13, 2015

History Trivia - Cardinal Richelieu of France creates the table knife

May 13

1497 Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) excommunicated Girolamo Savonarola (Italian Dominican friar and an influential contributor to the politics of Florence. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Rodrigo Borgia).

1515 Mary Tudor, Queen of France and Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk were officially married at Greenwich.

1637 Cardinal Richelieu of France created the table knife.

1497 Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) excommunicated Girolamo Savonarola (Italian Dominican friar and an influential contributor to the politics of Florence. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Rodrigo Borgia).

1515 Mary Tudor, Queen of France and Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk were officially married at Greenwich.

1637 Cardinal Richelieu of France created the table knife.

Published on May 13, 2015 01:30

May 12, 2015

The Rock Show with Diane Turner

Published on May 12, 2015 08:27

History Trivia - Richard I of England marries Berengaria of Navarre.

May 12,

254 Pope Stephen I succeeded Pope Lucius I as the 23rd pope. He was beheaded while celebrating Mass during Emperor Valerian's persecution of Christians.

1191 Richard I of England married Berengaria of Navarre.

1264 The Battle of Lewes, between King Henry III of England and the rebel Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, began.

254 Pope Stephen I succeeded Pope Lucius I as the 23rd pope. He was beheaded while celebrating Mass during Emperor Valerian's persecution of Christians.

1191 Richard I of England married Berengaria of Navarre.

1264 The Battle of Lewes, between King Henry III of England and the rebel Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, began.

Published on May 12, 2015 01:00

May 11, 2015

History Trivia - John Knox ignites the Scottish Reformation

May 11

330 Constantinople was dedicated as the new capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great.

482 Justinian I (the Great) was born. He was Byzantine (East Roman) emperor AD 527-565 who collected Roman laws under one code known as the Justinian Code.

1559 Religious reformer John Knox ignited the Scottish Reformation with a sermon at Perth, Scotland.

330 Constantinople was dedicated as the new capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great.

482 Justinian I (the Great) was born. He was Byzantine (East Roman) emperor AD 527-565 who collected Roman laws under one code known as the Justinian Code.

1559 Religious reformer John Knox ignited the Scottish Reformation with a sermon at Perth, Scotland.

Published on May 11, 2015 01:00

May 10, 2015

History Trivia - Siege of Jerusalem

May 10

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, opened a full-scale assault on Jerusalem and attacked the city's Third Wall to the northwest.

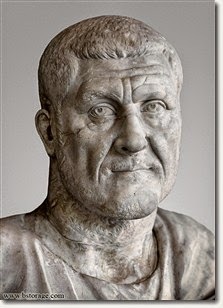

238 Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus, the Thracian, Roman Emperor, was murdered.

1291 Scottish nobles recognized the authority of Edward I of England.

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, opened a full-scale assault on Jerusalem and attacked the city's Third Wall to the northwest.

238 Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus, the Thracian, Roman Emperor, was murdered.

1291 Scottish nobles recognized the authority of Edward I of England.

Published on May 10, 2015 01:30

May 9, 2015

History Trivia - Colonel Thomas Blood.steals the crown jewels

May 9,

1092 Lincoln Cathedral, one of the most important medieval cathedrals in England, was consecrated.

1386 England and Portugal signed the Treaty of Windsor, the oldest alliance in Europe still in force.

1671 The crown jewels were briefly stolen from the Tower of London by Irish adventurer Colonel Thomas Blood.

1092 Lincoln Cathedral, one of the most important medieval cathedrals in England, was consecrated.

1386 England and Portugal signed the Treaty of Windsor, the oldest alliance in Europe still in force.

1671 The crown jewels were briefly stolen from the Tower of London by Irish adventurer Colonel Thomas Blood.

Published on May 09, 2015 01:00

May 8, 2015

8 things you (probably) didn’t know about medieval elections

History Extra

How did elections work in the Middle Ages? Here, Professor Björn Weiler from Aberystwyth University investigates…

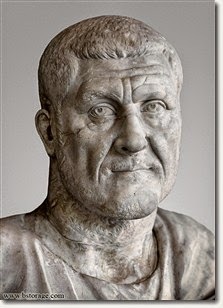

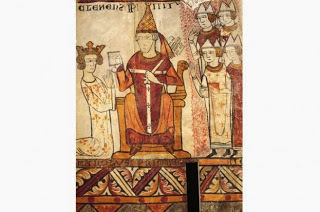

Pope Clement IV. After his death in 1268 it took the cardinals nearly three years to elect a new pope. (DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Pope Clement IV. After his death in 1268 it took the cardinals nearly three years to elect a new pope. (DeAgostini/Getty Images)

1) Elections were a common occurrenceMedieval people liked their elections: they elected bishops, popes, abbots, mayors, members of parliament, town councils, and so on. Perhaps surprisingly, they also elected their kings. When we look closely at these elections, we find many important differences between medieval and modern elections – but also some striking parallels.

2) Elections were seen as mixed blessingsSuch ambivalence reflected both the Biblical models on which writers and observers drew, and practical realities. On the one hand, elections thus provided a source of legitimacy.

Already in the Bible, the will of the people was an important (though not the only) factor in determining who would, for instance, become king of Israel. In fact, in the Old Testament, in the Book of Samuel, the existence of kingship itself was an expression of the people’s will: the Israelites wanted a king, and God gave them one.

In addition, sometimes elections were simply necessary: kings died without issue, or popes, bishops and abbots had to be chosen, and so on. A smooth succession, where son followed father without rival or dispute, was a rare one indeed. In England, for instance, only two occurred between 1066 and 1216 (when William Rufus (pictured below) followed William the Conqueror in 1087, and Richard Henry II in 1189).

While simple father-son successions became more common in the 14th century, few dynasties managed to match the Capetians, who had an unbroken run of sons succeeding fathers from 987 to 1316. Much of this had to do with biological vagaries. Sometimes there were no sons; the sons were under age, or there were several claimants with equally valid claims.

On the other hand, elections were also seen as occasions of strife, as starting points for revolt and rebellion. This was, in fact, the fear most frequently expressed about elections, and much of what we know about them was aimed at reducing the potential for strife and unrest.

King William Rufus (from the Historia Anglorum, Chronica majora). Found in the collection of British Library. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

3) Elections were supposed to be unanimousIn 1125, the German princes assembled to elect a new king. According to rumours, the archbishop of Mainz, who presided over the event, threatened the assembled candidates that he would behead any claimant who objected to the election of his rival.

The prelate’s actions reflected two major reasons why medieval elections were meant to be unanimous. They were, after all, often described as reflecting God’s will, who spoke through the people. A split result, in turn, would mean that either the candidates or the electors ignored the will of God (dissension was how the devil usually got his way).

In more pragmatic terms, there was no guarantee that an unsuccessful candidate would accept a decision. This had been the fear underpinning the archbishop’s actions in 1125 – and rightly so: the following year, one of the unsuccessful candidates sought to claim the throne by force.

That’s why normally several months could elapse, and why elections were normally conducted in private, away from the gaze of chroniclers and observers. The moment a decision had been made, the emphasis was on demonstrating unanimity.

In those papal elections that took place after 1271,a two-thirds majority was deemed sufficient. However, to ensure the semblance of unanimity, ballot papers were thus burned before an election was announced: nobody would know just how the votes had been shared out.

4) Elections could take a very long timeAfter the death of Pope Clement IV in November 1268, it took the cardinals nearly three years to elect a new pope. Even then, they reached a decision only after the exasperated citizens of Viterbo (where they had convened) locked them in a church, refused to feed them anything but water and bread, and removed the roof of the church.

While this was an extreme case, many months could elapse between the death of a king or prelate, and the succession of his successor. Sometimes this reflected practical needs: electors had to be assembled and convened, for instance; a suitable meeting place arranged, and so on. More importantly, though, the delay was often because elections were supposed to be unanimous.

5) Elections were concerned with moralityMedieval writers embraced an idea that went back to Classical Antiquity, according to which those who most desired power were the ones least deserving of it – nobody should desire to have authority over others. After all, it brought with it responsibility for both the spiritual and the material wellbeing of one’s subjects.

Those holding power would be responsible to God, and if they failed, would condemn both themselves and those given into their care. Moreover, power would corrupt those exercising it, and those who lacked moral backbone would succumb to this temptation all the more easily.

The ideal candidate, by contrast, was someone who was unwilling; who had to be forced to assume power over others. Being elected, in turn, was a means with which those chosen could demonstrate that they did not desire power, but had it thrust upon them.

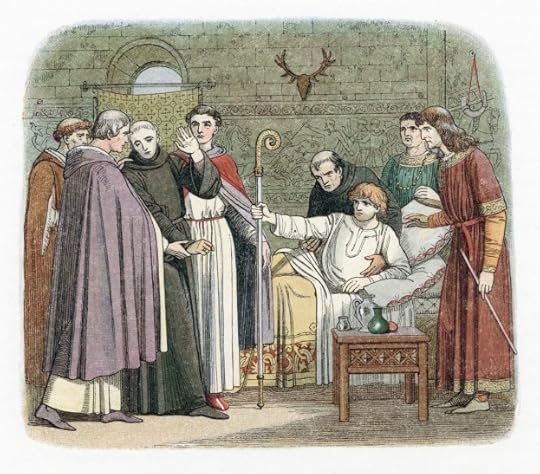

Most abbots and bishops were thus described as having been forced to accept their election. In fact, when St Anselm was elected archbishop of Canterbury in 1093, one account claimed that his fingers had to be broken for the episcopal staff to be passed into his hands.

We similarly have some evidence that kings, after they had been chosen, displayed a degree of reluctance: either asking that the election be repeated, or otherwise displaying humility and uncertainty.

St Anselm, Italian-born Archbishop of Canterbury. In this colour-printed wood engraving, Anselm is seen reluctantly accepting Archbishopric (represented by Crozier) from William II (Rufus) of England in 1093. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

6) The people mattered. But some people mattered more than othersWhen medieval authors wrote about the will of the people, they did not normally mean the populace at large. In fact, its role was viewed with a degree of suspicion. On the one hand, the people were needed: they were meant to acclaim, and to provide a suitably festive backdrop. However, they might take matters into their own hands.

The result of this unease could be real bloodshed. When William the Conqueror was crowned king of England in 1066, the presiding archbishop called on the assembled English and Normans to acclaim the king. This they did, but the Norman soldiers posted outside the Church mistook this to be an attack on the king, and started setting fire to the buildings surrounding the church.

Generally, therefore, being an elector was a token of prestige, a sign of being one of those people whose opinions mattered. The premise applied even in an urban context. Wide swathes of the population were thus excluded: women; children; foreigners; members of the clergy, and those who were not property owners (or whose properties earned less than a certain minimum income).

In 13th-century Florence, in order to be able to vote, one also had to join one of the city’s guilds (Dante Alighieri was in theory an apothecary and physician). Moreover, exactly because these people were so powerful, steps were taken to ensure unanimity – if these men felt cheated or ignored, they would too easily resort to violence – a recurrent feature in late medieval Italy.

Election procedures could thus be highly complex: rival groups would elect members from the opposing camp, who would then choose electors who both sides could agree on, who would in turn make a final decision. This was meant to ensure, if not unanimity, at least consensus: the person chosen, and the people doing the choosing, were meant to be acceptable to rival groups and factions, but without one dominating the others.

7) Election campaigns were frowned upon. But still happenedWith unanimity – the most desirable outcome – election campaigns were, at least in theory, frowned upon. They would, after all, encourage candidates to flaunt their ambition, and would encourage strife and factionalism.

In practice, matters were, of course, rather different: unanimity and consensus had to be ensured; allies won and rivals outwitted. Sometimes, rather drastic measures were taken: in 1002, for instance, Duke Henry of Bavaria claimed to have been so overtaken by grief at seeing the corpse of Emperor Otto III that he abducted the monarch’s remains as well as the archbishop escorting them, and did not set them free until the archbishop agreed to support Henry’s bid for the throne.

In a less macabre fashion, when Stephen of Blois claimed the English throne in 1135 he spent quite some time seeking to win over important nobles and prelates by promising much needed reforms and the favourable settlement of legal disputes. Just as frequently, candidates offered money and grants of lands or titles: votes, in short, were sold and bought.

It is more difficult to ascertain how these matters were handled in urban contexts: we simply lack the evidence for much of the period. We do, though, know about ecclesiastical elections, where campaigning could take rather different forms from the ones we are used to.

When, in the 1190s, the monks of Bury-St-Edmunds sought to elect a new abbot, one of the candidates was especially pious, and frequently proclaimed his reluctance – and he did so very publicly. The monks suspected this was campaigning rather than genuine reluctance, and felt vindicated when the brother was hit by a collapsing beam.

Sometimes, campaigning was cut short rather brutally by outside forces: in 1173, King Henry II of England was said to have taken matters into his own ends by writing to the canons of Winchester, who were about to elect a new bishop: “I command you to hold a free election, but I do not want you to accept anyone but my clerk Richard, archdeacon of Poitiers.”

Coronation of Otto III c998. The king's remains were abducted in 1002 by Duke Henry of Bavaria, who claimed to have been overtaken by grief at seeing the corpse. Henry refused to set them free until the archbishop agreed to support his bid for the throne. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

8) Elections were for life (except when they weren’t)Most medieval elections were for life: abbots, bishops and archbishops, and kings were chosen until they died or – more rarely – abdicated. Once elected and enthroned they could, at least in theory, no longer be deposed. In practice, however, there were of course rebellions and revolts, and from the later 12th century, new ideas of oversight developed across Europe.

Much of this oversight emerged from the election process: even after a king had been chosen, the decision still had to be made public. This often took the form of a presiding archbishop quizzing the candidate, and reminding him of his duties.

In 1199, the archbishop of Canterbury was thus said have warned King John that he had been elected to perform certain duties, and that he could be unelected again if he failed to perform them.

By the 14th century, this premise had become more widely accepted. In Germany, the electoral princes deposed kings in 1298 and 1400, and in England the nobles and parliament deposed kings in 1327 and 1399. In towns and cities, by contrast, terms were much shorter (with the exception of Venice, where the doge was elected for life).

Dante Alighieri was thus prior (the leading secular officer) of Florence for the customary term of two months, while mayors were normally elected for a period of one year. This partly reflected Roman antecedents (where consuls ruled for a year), but also the expense of office (there was no salary), and the desire to prevent the formation of factions.

Björn Weiler is a professor of medieval history at Aberystwyth University. He specialises in political and historical culture in the European Middle Ages between the 10th and 13th centuries.

How did elections work in the Middle Ages? Here, Professor Björn Weiler from Aberystwyth University investigates…

Pope Clement IV. After his death in 1268 it took the cardinals nearly three years to elect a new pope. (DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Pope Clement IV. After his death in 1268 it took the cardinals nearly three years to elect a new pope. (DeAgostini/Getty Images) 1) Elections were a common occurrenceMedieval people liked their elections: they elected bishops, popes, abbots, mayors, members of parliament, town councils, and so on. Perhaps surprisingly, they also elected their kings. When we look closely at these elections, we find many important differences between medieval and modern elections – but also some striking parallels.

2) Elections were seen as mixed blessingsSuch ambivalence reflected both the Biblical models on which writers and observers drew, and practical realities. On the one hand, elections thus provided a source of legitimacy.

Already in the Bible, the will of the people was an important (though not the only) factor in determining who would, for instance, become king of Israel. In fact, in the Old Testament, in the Book of Samuel, the existence of kingship itself was an expression of the people’s will: the Israelites wanted a king, and God gave them one.

In addition, sometimes elections were simply necessary: kings died without issue, or popes, bishops and abbots had to be chosen, and so on. A smooth succession, where son followed father without rival or dispute, was a rare one indeed. In England, for instance, only two occurred between 1066 and 1216 (when William Rufus (pictured below) followed William the Conqueror in 1087, and Richard Henry II in 1189).

While simple father-son successions became more common in the 14th century, few dynasties managed to match the Capetians, who had an unbroken run of sons succeeding fathers from 987 to 1316. Much of this had to do with biological vagaries. Sometimes there were no sons; the sons were under age, or there were several claimants with equally valid claims.

On the other hand, elections were also seen as occasions of strife, as starting points for revolt and rebellion. This was, in fact, the fear most frequently expressed about elections, and much of what we know about them was aimed at reducing the potential for strife and unrest.

King William Rufus (from the Historia Anglorum, Chronica majora). Found in the collection of British Library. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

3) Elections were supposed to be unanimousIn 1125, the German princes assembled to elect a new king. According to rumours, the archbishop of Mainz, who presided over the event, threatened the assembled candidates that he would behead any claimant who objected to the election of his rival.

The prelate’s actions reflected two major reasons why medieval elections were meant to be unanimous. They were, after all, often described as reflecting God’s will, who spoke through the people. A split result, in turn, would mean that either the candidates or the electors ignored the will of God (dissension was how the devil usually got his way).

In more pragmatic terms, there was no guarantee that an unsuccessful candidate would accept a decision. This had been the fear underpinning the archbishop’s actions in 1125 – and rightly so: the following year, one of the unsuccessful candidates sought to claim the throne by force.

That’s why normally several months could elapse, and why elections were normally conducted in private, away from the gaze of chroniclers and observers. The moment a decision had been made, the emphasis was on demonstrating unanimity.

In those papal elections that took place after 1271,a two-thirds majority was deemed sufficient. However, to ensure the semblance of unanimity, ballot papers were thus burned before an election was announced: nobody would know just how the votes had been shared out.

4) Elections could take a very long timeAfter the death of Pope Clement IV in November 1268, it took the cardinals nearly three years to elect a new pope. Even then, they reached a decision only after the exasperated citizens of Viterbo (where they had convened) locked them in a church, refused to feed them anything but water and bread, and removed the roof of the church.

While this was an extreme case, many months could elapse between the death of a king or prelate, and the succession of his successor. Sometimes this reflected practical needs: electors had to be assembled and convened, for instance; a suitable meeting place arranged, and so on. More importantly, though, the delay was often because elections were supposed to be unanimous.

5) Elections were concerned with moralityMedieval writers embraced an idea that went back to Classical Antiquity, according to which those who most desired power were the ones least deserving of it – nobody should desire to have authority over others. After all, it brought with it responsibility for both the spiritual and the material wellbeing of one’s subjects.

Those holding power would be responsible to God, and if they failed, would condemn both themselves and those given into their care. Moreover, power would corrupt those exercising it, and those who lacked moral backbone would succumb to this temptation all the more easily.

The ideal candidate, by contrast, was someone who was unwilling; who had to be forced to assume power over others. Being elected, in turn, was a means with which those chosen could demonstrate that they did not desire power, but had it thrust upon them.

Most abbots and bishops were thus described as having been forced to accept their election. In fact, when St Anselm was elected archbishop of Canterbury in 1093, one account claimed that his fingers had to be broken for the episcopal staff to be passed into his hands.

We similarly have some evidence that kings, after they had been chosen, displayed a degree of reluctance: either asking that the election be repeated, or otherwise displaying humility and uncertainty.

St Anselm, Italian-born Archbishop of Canterbury. In this colour-printed wood engraving, Anselm is seen reluctantly accepting Archbishopric (represented by Crozier) from William II (Rufus) of England in 1093. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

6) The people mattered. But some people mattered more than othersWhen medieval authors wrote about the will of the people, they did not normally mean the populace at large. In fact, its role was viewed with a degree of suspicion. On the one hand, the people were needed: they were meant to acclaim, and to provide a suitably festive backdrop. However, they might take matters into their own hands.

The result of this unease could be real bloodshed. When William the Conqueror was crowned king of England in 1066, the presiding archbishop called on the assembled English and Normans to acclaim the king. This they did, but the Norman soldiers posted outside the Church mistook this to be an attack on the king, and started setting fire to the buildings surrounding the church.

Generally, therefore, being an elector was a token of prestige, a sign of being one of those people whose opinions mattered. The premise applied even in an urban context. Wide swathes of the population were thus excluded: women; children; foreigners; members of the clergy, and those who were not property owners (or whose properties earned less than a certain minimum income).

In 13th-century Florence, in order to be able to vote, one also had to join one of the city’s guilds (Dante Alighieri was in theory an apothecary and physician). Moreover, exactly because these people were so powerful, steps were taken to ensure unanimity – if these men felt cheated or ignored, they would too easily resort to violence – a recurrent feature in late medieval Italy.

Election procedures could thus be highly complex: rival groups would elect members from the opposing camp, who would then choose electors who both sides could agree on, who would in turn make a final decision. This was meant to ensure, if not unanimity, at least consensus: the person chosen, and the people doing the choosing, were meant to be acceptable to rival groups and factions, but without one dominating the others.

7) Election campaigns were frowned upon. But still happenedWith unanimity – the most desirable outcome – election campaigns were, at least in theory, frowned upon. They would, after all, encourage candidates to flaunt their ambition, and would encourage strife and factionalism.

In practice, matters were, of course, rather different: unanimity and consensus had to be ensured; allies won and rivals outwitted. Sometimes, rather drastic measures were taken: in 1002, for instance, Duke Henry of Bavaria claimed to have been so overtaken by grief at seeing the corpse of Emperor Otto III that he abducted the monarch’s remains as well as the archbishop escorting them, and did not set them free until the archbishop agreed to support Henry’s bid for the throne.

In a less macabre fashion, when Stephen of Blois claimed the English throne in 1135 he spent quite some time seeking to win over important nobles and prelates by promising much needed reforms and the favourable settlement of legal disputes. Just as frequently, candidates offered money and grants of lands or titles: votes, in short, were sold and bought.

It is more difficult to ascertain how these matters were handled in urban contexts: we simply lack the evidence for much of the period. We do, though, know about ecclesiastical elections, where campaigning could take rather different forms from the ones we are used to.

When, in the 1190s, the monks of Bury-St-Edmunds sought to elect a new abbot, one of the candidates was especially pious, and frequently proclaimed his reluctance – and he did so very publicly. The monks suspected this was campaigning rather than genuine reluctance, and felt vindicated when the brother was hit by a collapsing beam.

Sometimes, campaigning was cut short rather brutally by outside forces: in 1173, King Henry II of England was said to have taken matters into his own ends by writing to the canons of Winchester, who were about to elect a new bishop: “I command you to hold a free election, but I do not want you to accept anyone but my clerk Richard, archdeacon of Poitiers.”

Coronation of Otto III c998. The king's remains were abducted in 1002 by Duke Henry of Bavaria, who claimed to have been overtaken by grief at seeing the corpse. Henry refused to set them free until the archbishop agreed to support his bid for the throne. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

8) Elections were for life (except when they weren’t)Most medieval elections were for life: abbots, bishops and archbishops, and kings were chosen until they died or – more rarely – abdicated. Once elected and enthroned they could, at least in theory, no longer be deposed. In practice, however, there were of course rebellions and revolts, and from the later 12th century, new ideas of oversight developed across Europe.

Much of this oversight emerged from the election process: even after a king had been chosen, the decision still had to be made public. This often took the form of a presiding archbishop quizzing the candidate, and reminding him of his duties.

In 1199, the archbishop of Canterbury was thus said have warned King John that he had been elected to perform certain duties, and that he could be unelected again if he failed to perform them.

By the 14th century, this premise had become more widely accepted. In Germany, the electoral princes deposed kings in 1298 and 1400, and in England the nobles and parliament deposed kings in 1327 and 1399. In towns and cities, by contrast, terms were much shorter (with the exception of Venice, where the doge was elected for life).

Dante Alighieri was thus prior (the leading secular officer) of Florence for the customary term of two months, while mayors were normally elected for a period of one year. This partly reflected Roman antecedents (where consuls ruled for a year), but also the expense of office (there was no salary), and the desire to prevent the formation of factions.

Björn Weiler is a professor of medieval history at Aberystwyth University. He specialises in political and historical culture in the European Middle Ages between the 10th and 13th centuries.

Published on May 08, 2015 07:14

Possible Captain Kidd Treasure Found off Madagascar

Discovery News

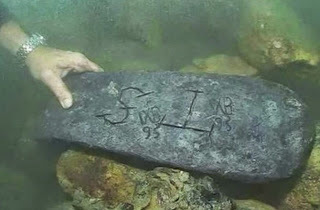

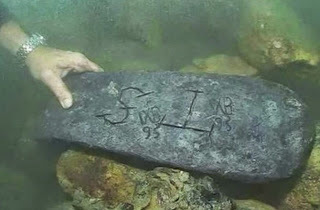

A 110-pound silver bar was found in the wreck of Kidd's ship the Adventure Gallery.

A 110-pound silver bar was found in the wreck of Kidd's ship the Adventure Gallery.

A team of American explorers on Thursday claimed to have discovered silver treasure from the infamous 17th-century Scottish pirate William Kidd in a shipwreck off the coast of Madagascar.

Marine archaeologist Barry Clifford told reporters he had found a 50-kilogram (110-pound) silver bar in the wreck of Kidd's ship the Adventure Gallery, close to the small island of Sainte Marie.

Captain Kidd, who was born in Scotland in about 1645, was first employed by British authorities to hunt pirates, but he turned himself into a ruthless criminal of the high seas.

After looting a treasure-laden ship in 1698, he was caught, imprisoned and questioned in front of the British parliament before being executed in Wapping, close to the River Thames in 1701.

The fate of much of his booty, however, has remained a mystery, sparking intrigue and excitement for generations of treasure-hunters.

Clifford, who was filmed by a documentary crew lifting the silver bar off the sea bed, handed it over to Malagasy President Hery Rajaonarimampianina on Sainte Marie. Soldiers guarded the apparent treasure at the ceremony, which was attended by the US and British ambassadors.

"We discovered 13 ships in the bay," Clifford said. "We've been working on two of them over the last 10 weeks. One of them is the Fire Dragon, the other is Captain Kidd's ship, the Adventure Galley."

How A Roman Ship Carried Live Fish: PhotosIndependent archaeologist John de Bry, who attended the ceremony, said the shipwreck and silver bar were "irrefutable proof that this is indeed the treasure of the Adventure Gallery." Robert Yamate, US ambassador to Madagascar, said the discovery was a boost for the country.

"This is a fantastic find that shows the hidden story of Madagascar," he said. "This is great for tourism... and it is just as important as historical preservation."

A 110-pound silver bar was found in the wreck of Kidd's ship the Adventure Gallery.

A 110-pound silver bar was found in the wreck of Kidd's ship the Adventure Gallery.A team of American explorers on Thursday claimed to have discovered silver treasure from the infamous 17th-century Scottish pirate William Kidd in a shipwreck off the coast of Madagascar.

Marine archaeologist Barry Clifford told reporters he had found a 50-kilogram (110-pound) silver bar in the wreck of Kidd's ship the Adventure Gallery, close to the small island of Sainte Marie.

Captain Kidd, who was born in Scotland in about 1645, was first employed by British authorities to hunt pirates, but he turned himself into a ruthless criminal of the high seas.

After looting a treasure-laden ship in 1698, he was caught, imprisoned and questioned in front of the British parliament before being executed in Wapping, close to the River Thames in 1701.

The fate of much of his booty, however, has remained a mystery, sparking intrigue and excitement for generations of treasure-hunters.

Clifford, who was filmed by a documentary crew lifting the silver bar off the sea bed, handed it over to Malagasy President Hery Rajaonarimampianina on Sainte Marie. Soldiers guarded the apparent treasure at the ceremony, which was attended by the US and British ambassadors.

"We discovered 13 ships in the bay," Clifford said. "We've been working on two of them over the last 10 weeks. One of them is the Fire Dragon, the other is Captain Kidd's ship, the Adventure Galley."

How A Roman Ship Carried Live Fish: PhotosIndependent archaeologist John de Bry, who attended the ceremony, said the shipwreck and silver bar were "irrefutable proof that this is indeed the treasure of the Adventure Gallery." Robert Yamate, US ambassador to Madagascar, said the discovery was a boost for the country.

"This is a fantastic find that shows the hidden story of Madagascar," he said. "This is great for tourism... and it is just as important as historical preservation."

Published on May 08, 2015 07:00