MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 175

May 22, 2015

History Trivia - Alexander the Great defeats Darius III of Persia

May 22,

334 BC The Macedonian army of Alexander the Great defeated Darius III of Persia in the Battle of the Granicus.

337 Constantine the Great, the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity died.

1455 Wars of the Roses: at the First Battle of St Albans, Richard, Duke of York, defeated and captured King Henry VI of England.

334 BC The Macedonian army of Alexander the Great defeated Darius III of Persia in the Battle of the Granicus.

337 Constantine the Great, the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity died.

1455 Wars of the Roses: at the First Battle of St Albans, Richard, Duke of York, defeated and captured King Henry VI of England.

Published on May 22, 2015 00:30

May 21, 2015

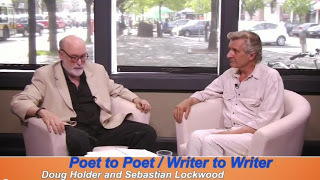

Gilgamesh! Sebastian Lockwood interviewed by Doug Holder on Poet to Poet/Writer to Writer, SCATV.

Sebastian Lockwood discusses his works with Doug Holder.

The Briton and the Dane fans: The Briton and the Dane is narrated by Sebastian Lockwood. Have a listen on Soundcloud:

Published on May 21, 2015 09:14

Author Brenda Perlin is featured in the 2014 Flash Fiction Anthology

The Indies Unlimited 2014 Flash Fiction Anthology features a year's worth of winning entries from the IndiesUnlimited.com weekly flash fiction challenge. It contains 50 stories by 34 different authors from around the world, with full color pictures by award-winning photographer K. S. Brooks and thought-provoking prompts by five-star author Stephen Hise. From a magic marmot to a zombie trick-or-treater, there are a myriad of genres and stories to appeal to every taste.

Best viewed on a color reader.

Authors with stories in the anthology include: Annette Rochelle Aben, Ralph L. Angelo, Jr., R.L. Austin, Laurie Boris, Melissa Bowersock, Christian A. Brown, Lynne Cantwell, A.V. Carden, Victoria A. Carr, Joan Childs, DW Davis, Leland Dirks, Jennifer Don, Ed Drury, Kathryn El-Assal, Sylvia Heike, Jamie R. Hershberger, Yvonne Hertzberger, Chris James, Howard Johnson, Vickie Johnstone, A. L. Kaplan, K.L. Kelso, L.A. Lewandowski, Angela Luo, S.A. Molteni, Kevin D. Montgomery, Arlene R. O'Neil, Sasha A. Palmer, Brenda Perlin, Sara Stark, Kathy Steinemann, Dick C. Waters, and Mandy White.

Amazon US

Published on May 21, 2015 08:58

History Trivia - English Lady Jane Grey marries Guildford Dudley.

May 21,

on this day The Agonalia was held. It was held on January 9th, March 17th, May 21st, and December 11th. On each day a ram was sacrificed, probably as an offering to Janus.

1420 Charles VI ceded France to Henry V of England in the Treaty of Troyes, after Henry's victory at Agincourt.

1553 English Lady Jane Grey married Guildford Dudley.

on this day The Agonalia was held. It was held on January 9th, March 17th, May 21st, and December 11th. On each day a ram was sacrificed, probably as an offering to Janus.

1420 Charles VI ceded France to Henry V of England in the Treaty of Troyes, after Henry's victory at Agincourt.

1553 English Lady Jane Grey married Guildford Dudley.

Published on May 21, 2015 01:30

May 20, 2015

8 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Woodvilles

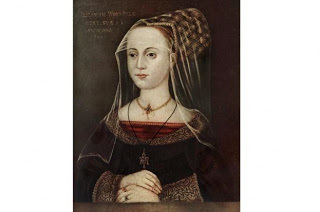

Elizabeth Woodville (1437–1492) in 1463. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

History Extra

In 1464, England's most eligible bachelor, King Edward IV, shocked the nation by announcing that he had taken a bride: Elizabeth Woodville, an impoverished widow with two young sons. The match brought his queen’s family into the thick of the Wars of the Roses

One of 12 surviving siblings, Elizabeth herself was the product of a runaway match between Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, and a knight, Sir Richard Woodville. Here, Susan Higginbotham, author of The Woodvilles: The War of the Roses and England's Most Infamous Family, reveals eight things you might not have known about Edward IV's in-laws…

1) Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, could have become queenWhen Henry V died in 1422, he left his infant son, Henry VI, as king. During the royal minority, Henry V's younger brothers, John, Duke of Bedford, and Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, governed the kingdom – Bedford was in charge of the crown's French possessions, while Gloucester handled affairs at home.

In 1433, the widowed Bedford took as his second wife Jacquetta de Luxembourg, the 17-year-old niece of the Bishop of Thérouanne. Had little Henry VI died, under the usual order of succession Bedford would have become king of England, and Jacquetta his queen.

This, of course, did not happen. Instead, Bedford died after just two years of marriage, leaving Henry VI to grow up to rule disastrously on his own, and Jacquetta to make a shocking, secret marriage to Sir Richard Woodville, the son of Bedford's chamberlain. But although Jacquetta never wore a crown, her daughter Elizabeth would, through making her own clandestine marriage to Edward IV.

2) Elizabeth Woodville founded Queens' College – againMargaret of Anjou, Henry VI's queen, founded a college at Cambridge in 1448. When Henry VI lost his crown to Edward IV, the college fell on hard times. Enter Elizabeth, Edward's queen. In 1465 she refounded the college, and gave it its first statutes 10 years later.

It is often said that the placement of the apostrophe in Queens' reflects the fact that two queens founded the college, but the college disputes that story. Even if Elizabeth can't claim credit for the placement of an apostrophe, her portrait hangs in the college.

3) Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, was accused of witchcraftIn 1469, Edward had a falling-out with Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, over foreign policy and over what Warwick believed was the undue influence Edward gave to upstarts such as the Woodvilles.

Relations between the two deteriorated to the point where Warwick revolted against Edward, taking him prisoner and killing Elizabeth Woodville's father and her brother John.

During this period of upheaval, a follower of Warwick produced some lead images that he claimed Jacquetta had made for the purposes of witchcraft and sorcery. Despite the shock of her recent bereavement, Jacquetta refused to be cowed by the accusations, and wrote to the mayor and the aldermen of London for their assistance, which they granted.

Further intervention proved unnecessary, however, for Warwick found it decidedly awkward to keep holding the king captive, and released him. With Edward back in charge, the king’s council cleared Jacquetta of the charges against her. The accusations of witchcraft did not die, however, but were revived by Richard III in 1484, when his parliament declared that Jacquetta had used witchcraft to procure her daughter's marriage to the king.

Elizabeth Woodville with Edward IV in 1464. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

4) Anthony Woodville helped save London from a Lancastrian attackWarwick reconciled with Edward IV, but the amity was short-lived. In 1470, Warwick allied with the exiled Margaret of Anjou to put the now imprisoned Henry VI back on the throne. Having been forced to flee the country, Edward IV returned to reclaim the throne and defeated the Lancastrians at the battles of Barnet (14 April 1471) and Tewkesbury (4 May 1471).

The Yorkist victory at Tewkesbury, however, did not end the conflict. Although Warwick was killed at Barnet, and Henry VI's teenage son was killed at Tewkesbury, Henry VI remained alive inside the Tower of London. With the thought of freeing him, a Neville relation known as the Bastard of Fauconberg launched an attack on London, which Edward had left in the charge of the Earl of Essex and Anthony, Earl Rivers, Elizabeth Woodville's brother.

As Fauconberg's men attacked Aldgate, Anthony drove them back, thus helping save London for the Yorkists – a feat his contemporaries would remember in verse: "Through his enemies that day did he p

5) While abroad, Anthony Woodville was robbedThe most cultivated of the Woodville family, Anthony went on pilgrimage to Italy in 1476. The 2nd Earl Rivers did not travel light, and in Venice he was robbed of his jewels and plate, which were worth at least 1,000 marks.

It helps a traveller, however, to be the brother-in-law of the king of England. The Venetians promptly set about searching for the criminals and restoring to Anthony his jewels – which had been purchased by local citizens – while arranging to reimburse those who had bought the purloined goods in good faith. When Anthony finally resumed his travels, the Venetians were probably happy to see the last of him, as he had been a rather expensive visitor.

6) Anthony Woodville was a ‘techie’In late 1475 or early 1476, William Caxton brought a newfangled device to England – the printing press. Soon he had produced the first book printed in England: an edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s ever-popular Canterbury Tales.

The nobility, however, were slow to embrace this new technology, with Edward IV himself preferring to amass illuminated manuscripts. One nobleman, however, seized upon this new opportunity to disseminate knowledge to the masses: Anthony Woodville. He translated three books for Caxton to print, and may have been responsible for sending several others to press as well.

Caxton even made a joke about Anthony's love life. In his epilogue to Anthony's translation of The Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers (a book which, sadly, has not withstood the test of time), Caxton noted that Anthony had omitted some of Socrates' unflattering observations about women. He surmised: “But I suppose that some fair lady hath desired him to leave it out of his book. Or else he was amorous on some noble lady…”

c1800: Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers. Engraved by Gerimia from the book A Catalogue of the Royal and Noble Authors published 1806. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

7) The Woodvilles didn't rob the treasuryIn 1483, Edward IV suddenly died, leaving a 12-year-old heir, Edward. By the time the dust settled, Edward IV's younger brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was king (Richard III), and Prince Edward and his younger brother had been taken to the Tower of London, never to be seen again.

For reasons that remain debatable, Gloucester arrested Anthony Woodville and several others after Edward IV's death, and Elizabeth Woodville fled into sanctuary. Legend has it she took with her part of the royal treasury, which she supposedly divvied up between one of her brothers and her oldest son from her first marriage. But did this really happen?

The sole source for the story is an Italian observer, Dominic Mancini, who reported the treasury story only as a rumour he had heard, not as an established fact. Richard III never accused Elizabeth or her family of stealing royal treasure, nor is there is any evidence that he believed any treasure was missing. In fact, as historian Rosemary Horrox has shown, excursions against the Scots had left the treasury seriously depleted by the time Edward IV died, and defending the realm against French pirates left England even poorer.

One Woodville, however, did acquire a very large sum during this time: Sir Edward Woodville, Elizabeth Woodville's youngest brother, who was busy patrolling the seas when Anthony was captured. In mid-May 1483 he seized some £10,250 in English gold from a vessel, claiming it for the crown. Soon afterward, learning that Gloucester had ordered his arrest, Edward sailed to Brittany – presumably taking his gold with him, for it was never heard of again.

8) Sir Edward Woodville lost his teeth for Ferdinand and IsabellaHaving helped Henry Tudor defeat Richard III at the battle of Bosworth in 1485, Edward went to Spain the following year to fight the ‘infidels’, possibly in fulfillment of a vow. Having joined forces led by Ferdinand and Isabella to fight the Moors, Edward was mounting a scaling ladder when he was struck by a stone that knocked him unconscious and cost him his two front teeth.

Visited later by Henry VII and his queen, Edward quipped of his missing teeth: “Our Lord, who reared this fabric, has only opened a window in order to discern the more readily what passes within.”

When Edward finally returned to England, he did not go empty-handed: Queen Isabella sent him away with 12 Andalusian horses, two beds with rich hangings, and other valuables. But Edward's next foreign adventure proved to be his last: in 1488, he was killed while fighting for Brittany against France.

Susan Higginbotham is the author of The Woodvilles: The War of the Roses and England's Most Infamous Family (The History Press, March 2015), the first non-fiction book on the Woodville family. To find out more, click here.

Published on May 20, 2015 15:11

Archaeologists in Sweden unearth first Viking brooch piece depicting dragon head

Ancient Origins

Ancient OriginsArchaeologists carrying out excavations in the port of Birka, Sweden’s oldest town, have unearthed a tiny dragon head once used on a Viking brooch. The bronze relic matches the shape of a mold that was found back in 1870, but it is the first time researchers have found the actual object that came out of the mold.

The dragon’s head is one of the most famous symbols of the Vikings. Their ships typically had a Viking head mounted on the bow to scare off sea monsters, which they would remove as they approached land so as not to repel the land gods.

The dragon head is a famous symbol of the Vikings and was often mounted on their ships. ‘Guests from Overseas’ by Nicholas Roerich. (

Wikipedia

)According to The Local, the tiny dragon’s head was found during a dig in the harbor at Birka on the island of Björkö ("Birch Island") in Lake Mälaren, which is located approximately 40kms from Stockholm. During the Viking Age, Birka was an important trading center which handled goods from Scandinavia as well as Central and Eastern Europe and the Orient. Established in the middle of the 8th century, the site is generally regarded as Sweden's oldest town, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993.

The dragon head is a famous symbol of the Vikings and was often mounted on their ships. ‘Guests from Overseas’ by Nicholas Roerich. (

Wikipedia

)According to The Local, the tiny dragon’s head was found during a dig in the harbor at Birka on the island of Björkö ("Birch Island") in Lake Mälaren, which is located approximately 40kms from Stockholm. During the Viking Age, Birka was an important trading center which handled goods from Scandinavia as well as Central and Eastern Europe and the Orient. Established in the middle of the 8th century, the site is generally regarded as Sweden's oldest town, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993.Earlier this year, a silver ring excavated over a century ago from a Viking-era grave in Birka was found to have an Arabic inscription, providing physical evidence of direct contact between the Vikings of Sweden and the Muslim world, in this case possibly Asia Minor.

While the archaeological site of Birka has continued to yield fascinating relics ever since excavations first began in the 17th century, the discovery of the bronze dragon's head is considered one of the most exciting finds in recent years.

Excavation at Birka on the island of Björkö (

Wikimedia Commons

)The dragon’s head is made of bronze and was originally part of a small brooch or costume needle, which came out of a mold that was originally found at Birka over a century ago. The dragon is wearing a collar and has open jaws and curls of hair, a style which researchers have said is unique to the island on which it was found.

Excavation at Birka on the island of Björkö (

Wikimedia Commons

)The dragon’s head is made of bronze and was originally part of a small brooch or costume needle, which came out of a mold that was originally found at Birka over a century ago. The dragon is wearing a collar and has open jaws and curls of hair, a style which researchers have said is unique to the island on which it was found.Ring discovered in Viking-era grave has Arabic inscription Did a Native American travel with the Vikings and arrive in Iceland centuries before Columbus set sail? Norsemen transformed international culture, manufacturing, tech and trade during Viking Era

Viking style dragon at the Hopperstad stave church (

Wikimedia Commons

)"We did not understand immediately what it was that we had found. It took a couple of minutes. But when we looked a second time, we saw the strands of hair," said Sven Kalmring, professor at the German Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie, who has been excavating in the port together with people from Stockholm University's archaeology department.

Viking style dragon at the Hopperstad stave church (

Wikimedia Commons

)"We did not understand immediately what it was that we had found. It took a couple of minutes. But when we looked a second time, we saw the strands of hair," said Sven Kalmring, professor at the German Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie, who has been excavating in the port together with people from Stockholm University's archaeology department.The brooch or costume needle upon which the dragon head was mounted had long since disintegrated. Archaeologists will now analyze the artifact, and compare it to other similar Viking relics found at other sites throughout Scandinavia.

Featured image: The dragon's head on the piece of metal fits into the mold found in 1870. Photo: Antje Wendt/Historiska museet.

Published on May 20, 2015 15:01

History Trivia - Battle of Dunnichen - Picts victorious

May 20,

325 Roman emperor Constantine called the Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical Christian council.

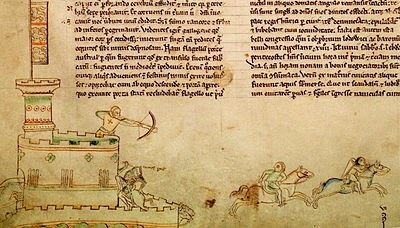

685 The Battle of Dunnichen or Nechtansmere was fought between a Pictish army under King Bridei III and the invading Northumbrians under King Ecgfrith, who were decisively defeated.

1217 The Second Battle of Lincoln was fought near Lincoln, England, resulting in the defeat of Prince Louis of France by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke.

325 Roman emperor Constantine called the Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical Christian council.

685 The Battle of Dunnichen or Nechtansmere was fought between a Pictish army under King Bridei III and the invading Northumbrians under King Ecgfrith, who were decisively defeated.

1217 The Second Battle of Lincoln was fought near Lincoln, England, resulting in the defeat of Prince Louis of France by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke.

Published on May 20, 2015 01:00

May 19, 2015

History Trivia - Queen Elizabeth I of England orders the arrest of Mary, Queen of Scots

May 19,

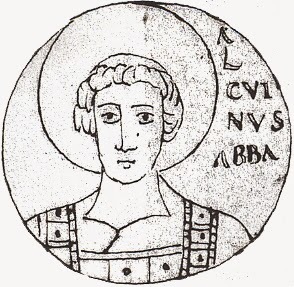

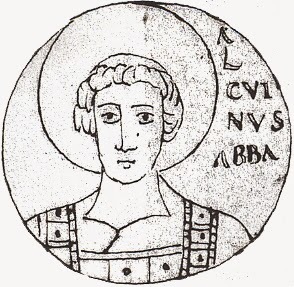

804 Alcuin of York, English scholar, died in Tours France. He was welcomed at the Palace School of Charlemagne in Aachen where he remained during the 780's and 790's.

1499 Catherine of Aragon (age 13), was married by proxy to Arthur Tudor (age 12), Prince of Wales.

1568 Que en Elizabeth I of England ordered the arrest of Mary, Queen of Scots.

en Elizabeth I of England ordered the arrest of Mary, Queen of Scots.

804 Alcuin of York, English scholar, died in Tours France. He was welcomed at the Palace School of Charlemagne in Aachen where he remained during the 780's and 790's.

1499 Catherine of Aragon (age 13), was married by proxy to Arthur Tudor (age 12), Prince of Wales.

1568 Que

en Elizabeth I of England ordered the arrest of Mary, Queen of Scots.

en Elizabeth I of England ordered the arrest of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Published on May 19, 2015 00:30

May 18, 2015

How the Tudors invented breakfast

History Extra

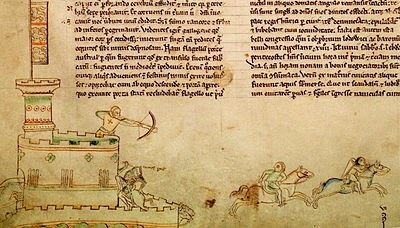

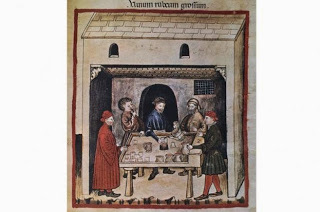

History ExtraIn the Middle Ages, the nation that was to give the world the full English widely skipped breakfast. Yet, by 1600, a culinary non-entity had become a key part of our daily routine. Why the change? Ian Mortimer investigates.

This article was first published in the April 2013 issue of BBC History Magazine

Few of us in the 21st century would dream of embarking upon our days on an empty stomach, but in historical terms, breakfast is hardly noticeable. Whole books have been written about feasts and banquets, dinners and suppers. Even teatime has its place on the shelves of our social history. But breakfast? Cornflakes, muesli, bacon and eggs, continental or full English – they are almost all ignored. And they are all features of the modern breakfast, which is far more often studied than breakfasts before 1600.

The reason is not hard to find. Feasts and banquets have their ritual, their theatre and their sources. We can read about the tens of thousands of animals killed for a two-day visit by Queen Elizabeth because accounts had to be compiled to manage the provision of so much meat. Likewise in the medieval royal household, the feasts were occasionally described by chroniclers who witnessed the king eating in the company of his courtiers.

We know about seating plans, table arrangements, etiquette and procedure at many formal meals. Cookery books survive to reveal the kind of dishes that were informally served, and poems and stories attest to what poorer folk ate for supper and dinner.

Breakfasts, by comparison, do not have their literature. Chroniclers did not observe monarchs eating breakfast. The first meal of the day is thus one of those features of life that has slipped through the historian’s net.

What historians have known for a long time is that in the late medieval period many people did not eat breakfast. Evidence for this lies in such sources as the household ordinances of the nobility and gentry, which regularly specify who was allowed to eat breakfast and who was not. In 1412–13 only half a dozen of the 20 or so people in the household of Dame Alice de Bryenne were permitted to eat breakfast.

Sixty years later, in the household of Cicely, Duchess of York, the privilege of attending breakfast was extended only “to head officers when they be present, to the ladies and gentlewomen, to the dean and to the chapel, to the almoner and to the gentlemen ushers, to the cofferer, to the clerk of the kitchen and the marshal”. In the ‘Black Book’ of Edward IV, careful attention was paid to the ranks that were allowed to eat breakfast.

A two-meal dayClearly, breakfast was a privilege in the 15th century. One comes across a few other references to it being eaten in different contexts – travellers ate breakfast, for instance – but, on

the whole, the lack of evidence for breakfasting in the late Middle Ages (by comparison with plentiful references to dining, supping and feasting) leave us with the distinct impression that most people went without. Rather than a three-meal-per-day routine, medieval people had a two-meal one. The main meal, dinner, was held at about 10.30 or 11 in the morning, and supper about five hours later.

This is all well and good until you ask the question, why did things change? And when exactly did the change take place? Suddenly, looking at a few documents and making a few sweeping generalisations doesn’t seem quite adequate.

The ‘when’ is the easiest bit of the question to answer. As we’ve already seen, household servants were regularly denied breakfasts in the 15th century. Yet schoolboys a hundred years later could expect it. In Claudius Hollyband’s book The French Schoolmaster (1573),

a maidservant says to a schoolboy: “Ho, Frances, rise and get you to school; you shall be beaten, for it is past seven. Make yourself ready quickly, say your prayers, then you shall have your breakfast.”

If schoolboy breakfasts were the norm in 1573 then it is reasonable to assume that many other unimportant people were eating them too. Several early 16th-century sources back this up. Thomas More wrote in 1528 “men should go to Mass as well after supper as before breakfast”, and Thomas Elyot recommended eating breakfast four hours before dinner in his popular work The Castell of Health (1539). Lest it be thought that these references only apply to a minority of literate gentlemen, Andrew Boorde in his Dietary of Health (1542) stated that “a labourer may eat three times a day [ie including breakfast] but that two meals are adequate for a rest man”.

To go further than this, we need to examine what breakfast meant in the earlier centuries. In so doing it is necessary to steer ourselves away from just considering noble households. What was the ordinary person doing at breakfast time in the Middle Ages?

It’s also important to bear in mind that medieval people might not have thought of breakfast in the same way that we do. If some people could have breakfast and some couldn’t, the status implicit in eating early in the morning may well have meant that breakfasts had ceremonial significance at points in the past.

A survey of the contemporary sources available reveals that before 1500 non-ceremonial breakfasts were routinely taken by several sections of society. First, breakfast was seen as medicinal: people might be prescribed “a breakfast of…” as a means to sustain them in illness or old age. In 1305, Edward I (then aged 65), employed a cook just to prepare breakfasts.

Second, we find certain classes of monks eating breakfast. Old and sick monks fall into the category above, of course; but in addition young monks were permitted a light breakfast. At Peterborough it was argued that if the young monks did not have a breakfast, they ate so much at dinner they fell asleep in the afternoons.

The lady paysMonastic breakfasts are understandable in the context of young men having to get up in the early hours to sing Mass. The early start also explains why travellers setting out often consumed a breakfast before spending a long day in the saddle. And manorial tenants were sometimes entitled to breakfast at harvest time. This is only recorded, of course, when the duty for providing the breakfast fell on the lord of the manor, such as at Bicester in 1325, when a customary (written selection of customs) declared the harvest workers should be provided with a breakfast at the expense of the lady of the manor.

Some manorial customaries go so far as to state when the lord was not responsible for paying for a breakfast. On the manor of Chinnor in 1279, for example, all the tenants had to scythe the lord’s fields and cart hay: when carting hay they were provided with a breakfast, but when scything they had to provide their own. Labourers working on York Minster in 1352 were permitted to eat their breakfast in part of the building – again no doubt due to the long hours they were working.

What emerges from a study of a wide range of sources is that breakfast was often provided for labourers as well as the gentry in the late 13th and early 14th centuries – but that labourers and men and women of modest means tended to eat breakfast only if they were rising very early,

working very long hours, or they were old or sick.

Breakfast was rooted in necessity, not a demonstration of status. No doubt it extended beyond the limits outlined above – for it is important to remember that the sources used are nearly all for the formal allowance of breakfast by a third party. If a town worker got up early to work and was hungry, and there was some bread remaining from the previous day, he would naturally eat it – but there would be no record of his doing so.

Alongside practical breakfasts were a number of ceremonial ones. When Joan de Valence was travelling in 1297, she hosted a jantaculum (breakfast) attended by several noblemen and women and 20 paupers. In 1415 Henry V invited a large number of noblemen to discuss the forthcoming Agincourt campaign with him in a great jantaculum at Westminster.

Ceremonial breakfasts were held by a number of guilds and corporations on the admittance of a new member. For example, in 14th-century Reading, new burgesses entering the Guild had to pay 3s 4d for a ceremonial breakfast on top of their entry fee. A similar corporate jantaculum was held at Norwich before the start of the annual procession of St George in the 15th century.

Practical breakfasts were naturally more varied than ceremonial ones, many of them being private. However, most were fairly basic. There are very few references to anything being cooked for breakfast, and none to the provision of sauces. Choristers at St Paul’s in the 12th century received bread and ale.

Similarly, 12th and 13th-century manorial breakfasts at harvest time were often stated to be of bread, cheese and ale. In 1402, Westminster monks having their blood let were provided with breakfasts of bread and ale; and the Norwich jantaculum was traditionally of wine, bread and cheese.

The most significant difference was the traveller’s breakfast. Often we find this consisted of nothing but ale or wine. In 1274, for example, a flask of wine costing 4d was “bought for the jantaculum of the lord Geoffrey and W de Hexton going towards Windsor to prepare against the coming of the queen”, and in the 1390s, when the future Henry IV was on his travels, he sometimes had only a liquid breakfast. Henry was not a creature of routine, however; sometimes in France he paid for chickens to be bought and cooked for his breakfast, in addition to bread, wine and beer.

The noblemen’s breakfasts of the 16th century were more elaborate. In 1501, the Duke of Buckingham built himself a breakfast room in his house at Queenhithe. There he ate in the company of about 30 important guests and members of his household. On fish days (Wednesday, Fridays and Saturdays), when eating meat was forbidden, his breakfast consisted of pike, plaice, roach, butter and eggs.

Ten years later the 5th Earl of Northumberland and his countess sat down each fish-day morning to the following repast: two manchets (high-quality white loaves), two pints of beer, three pints of wine, two pieces of salt fish, six smoked herrings, four white herring or a dish of sprats. On meat days they replaced the fish with a neck of mutton or boiled beef.

The servants in the earl’s household were also given breakfast. What they each received depended on their status: the countess’s lady companions were given a loaf of household bread, beer and boiled mutton or beef. The men in the stables just received a small amount of household bread and beer.

Love of butterMore dairy products appeared in the 16th century. In 1558 the executors of Henry Willoughby’s estate were given a breakfast of bread, ale and a sweet dish made of eggs, butter, sugar and currants. Thomas Cogan remarked in The Haven of Health (1584) that “bread and butter” was a countryman’s breakfast. Butter became exceedingly popular. Various herbs were added to butter to impart their properties to the breakfaster: sage was thought to sharpen the wits, so this was a popular additive.

The idea that breakfast could do you good was no longer considered to apply solely to the sick and old. Indeed, in some quarters, people began to think that the old did not need breakfast at all. In 1602 the physician William Vaughan advised: “Eat three meals a day until you come to the age of 40 years.”

Eating breakfast was not quite ubiquitous by 1600. At Grimsthorpe Castle, two meals per day was still the rule in 1561, with only a few exceptions. Similarly, the household ordinances of Francis Willoughby (died 1596), the builder of Wollaton Hall, do not consistently mention breakfasts. Sir John Harington (died 1612) advised his readers to “feed only twice a day when you are at a man’s age” although he went on to say that the choleric should eat breakfast. Despite these late 16th‑century exceptions, the majority of the middling sort and many yeomen and labourers were regularly eating breakfast by 1600.

So, why the change? As the above has shown, the shift to eating breakfast was not quite as sudden as previously thought. Prior to 1500 several sorts of common people did eat a breakfast of sorts. However, there clearly was a degree of change in the 16th century: it became the norm, not the exception.

Some writers have attributed this to the Reformation. Some to the greater availability of food. Proponents of both explanations have not explained how either event affected society’s dining habits as a whole. Something more profound was happening.

Regular hoursThe answer is probably to be found in changing patterns of employment. In the earlier Middle Ages, the majority of people organised their own time. They were not ‘employed’ as such.

A manorial tenant had work to do on his lord’s land, but he did not have to get up at the crack of dawn to do it. Only in summer, with haymaking and hay-carting responsibilities to fulfil, did the breakfast become a necessity, because of the long hours in the fields. It was the same for travellers setting off on long journeys: the early start made breakfast a necessity. It was such a long time until dinner at 11am that they needed the sustenance to keep them going. Young monks clearly ate breakfast for the same reason.

What happened in the 16th century was that men increasingly started working for other people, employed for a prescribed set of hours each day. The long hours that employees could be expected to work can be seen in a statute of 1515 which declared that, between mid-March and mid-September, the working day of craftsmen and labourers should begin at 5am and continue to 7 or 8pm with only an hour and a half for dinner.

The consequences are obvious: if a labourer cannot have his supper until 7 or 8pm, he is going to get hungry if he has his dinner at the traditional medieval time of 10.30 or 11am: a nine-hour gap. As mentioned above, Thomas Elyot recommended that dinner and supper be no more than six hours apart. Thomas Cogan echoed this in his 1584 treatise. Thus the old medieval dinner time was pushed back to the later time of luncheon.

Delaying lunch had a knock-on effect on the start of the day. As the time of dinner was pushed back to luncheon, at 12 or 1pm, people needed a solid breakfast to keep them going. As for the gap between breakfast and dinner, Elyot, Cogan and Vaughan all agreed that this should be no more than four hours. Such a shift, based around employment, was thus primarily an urban phenomenon, or one of workers in towns, and areas providing the towns.

We can see the transition in progress in the pages of William Harrison’s Description of England (1577). In that work he states that “the nobility, gentry, and students [all of them old-fashioned institutions] do ordinarily go to dinner at 11 before noon, and to supper at five, or between five and six at afternoon. The merchants dine and sup seldom before 12 at noon, and six at night, especially in London. The husbandmen dine also at high noon as they call it, and sup at seven or eight…”

The history of breakfasting is thus much more nuanced than the old conclusion that, in the Middle Ages, ‘only the rich ate breakfasts’. It is bound up with, and indicative of, our emergence as a people who worked for a living rather than lived off the land.

Dr Ian Mortimer is the author of 10 books and many articles on English history, and writes fiction under the name James Forrester.

Published on May 18, 2015 07:50

"My Lovely Blog" Blog Hop

Author Kim Scott I’ve been tagged by author Kim Scott (you can check out her blog at http://www.kimscottbooks.com/apps/blog) as a participant in the ‘My Lovely Blog’ blog hop. Thanks, Kim. And now for the answers you've all been waiting for. DRUM ROLL PLEASE

Author Kim Scott I’ve been tagged by author Kim Scott (you can check out her blog at http://www.kimscottbooks.com/apps/blog) as a participant in the ‘My Lovely Blog’ blog hop. Thanks, Kim. And now for the answers you've all been waiting for. DRUM ROLL PLEASE First Memory At the young age of 4, I was playing in front of our house with the other children. My mom was sitting on the front stairs, talking with the other moms when a dad walking a St. Bernard headed towards our little group. We squealed with delight when told we could ride the dog, and one by one, each of my little friends was put on the back of the St. Bernard who then walked to the corner of the block and back again. By the time it was my turn, the dog must have either been tired or resentful of being used as a horse, because he threw me to the ground and bit my neck. And that is the reason why I am not an animal lover.

Books My love for books began with my first grade reader “Mac and Muff” - See Mac run. See Muff run. I don’t recall the titles of any other grade school readers, but I do remember quite a few required reading novels while in high school: Ivanhoe, Silas Marner, To Have and to Hold, to name but a few. Sir Walter Scott, George Eliot and Mary Johnston created a visual world for an impressionable young mind to explore.

Books My love for books began with my first grade reader “Mac and Muff” - See Mac run. See Muff run. I don’t recall the titles of any other grade school readers, but I do remember quite a few required reading novels while in high school: Ivanhoe, Silas Marner, To Have and to Hold, to name but a few. Sir Walter Scott, George Eliot and Mary Johnston created a visual world for an impressionable young mind to explore.

Being fascinated with historical figures throughout the ages, my recreational reading might be considered required texts for history courses. Favorites include Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, Alfred the Great, Richard III, Elizabeth I, Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia, Henry VIII and so on - too many favorites to list.

An excellent find was discovering Frans G. Bengtsson’s The Long Ships and, more recently, Roma: A Novel of Ancient Rome by Steven Saylor. Thank you, Amazon, for your category menus - such a wonderful selection of talented authors.

Libraries or Bookshops While growing up, most of my time was spent in the library, but with the advent of the mall, bookshops popped up and, suddenly, you could easily purchase a favorite book not readily available in the local library.

Libraries or Bookshops While growing up, most of my time was spent in the library, but with the advent of the mall, bookshops popped up and, suddenly, you could easily purchase a favorite book not readily available in the local library.

Yonkers, NY Public Library, Main Branch

Yonkers, NY Public Library, Main BranchBookshops not only market best sellers and new releases, they offer bargain books on a variety of topics, which is how I built my medieval library. Imagine me doing a happy dance when I came upon an illustrated copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles on one of the shelves.

It’s fun to browse a retail bookstore - you never know what gems you will find.

Learning I was an average student during my high school years and after graduation, I studied medical technology in a year-long program. Working in the field for several years was rewarding, but I decided upon a different career path, studying business administration. I was either a late bloomer or my interests had changed, because I graduated with honors with a B.S. degree.

Learning I was an average student during my high school years and after graduation, I studied medical technology in a year-long program. Working in the field for several years was rewarding, but I decided upon a different career path, studying business administration. I was either a late bloomer or my interests had changed, because I graduated with honors with a B.S. degree.

Since writing-related courses was not part of the curriculum, I signed up for creative writing workshops and took non-credit writing courses throughout the years. I continue to hone my craft and am currently enrolled in an on-line writing course at Future Learn. And yes, I’m still having fun.

What's Your Passion First is my love for family - number one priority in my life. You can find me in the stands at all sporting events and dance competitions, cheering on my grandchildren. It doesn’t get any better than that.

What's Your Passion First is my love for family - number one priority in my life. You can find me in the stands at all sporting events and dance competitions, cheering on my grandchildren. It doesn’t get any better than that.

Second is my passionate support of the United States Military. Freedom is not free and we must never forget the sacrifices of the men and women who protect our country, and I have dedicated my novels to our fallen soldiers.

Next is my passion for history. When I visited Rome a few years ago, I went to the Forum and stood where Julius Caesar stood and walked the coliseum where so many people died. One could envision how it must have looked during the Empire’s glorious days. Touching stones over two thousand years gives me Goosebumps.

Lastly, but not least, is my writing career. There’s nothing better than having a reader enjoy a story you have written. While mere man returns to dust, his words live forever.

And now it’s time for me to pass on the baton to author K. Meador (http://inthemidst-km.blogspot.com).

Author K. Meador

Author K. Meador

Published on May 18, 2015 04:30