MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 168

June 26, 2015

History Trivia - Pied Piper leads 130 children out of Hamelin, Germany

June 26

1284 the legendary Pied Piper led 130 children out of Hamelin, Germany.

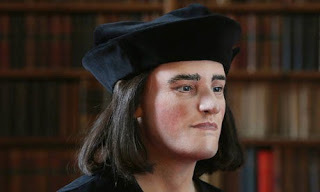

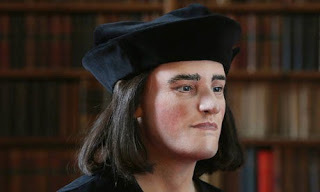

1483 Richard III was crowned king of England after declaring his nephews Edward and Richard illegitimate.

1498 Toothbrush invented

1284 the legendary Pied Piper led 130 children out of Hamelin, Germany.

1483 Richard III was crowned king of England after declaring his nephews Edward and Richard illegitimate.

1498 Toothbrush invented

Published on June 26, 2015 02:00

June 25, 2015

History Trivia - Battle of Vézeronce

June 25

253 Pope Cornelius died at Centumcellae where he was exiled during the Christian persecution under Trebonianus Gallus Augustus.

524 The Franks defeated the Burgundians in the Battle of Vézeronce.

524 The Franks defeated the Burgundians in the Battle of Vézeronce.

841 In the Battle of Fontenay-en-Puisaye, forces led by Charles the Bald and Louis the German defeated the armies of Lothair I of Italy and Pepin II of Aquitaine.

253 Pope Cornelius died at Centumcellae where he was exiled during the Christian persecution under Trebonianus Gallus Augustus.

524 The Franks defeated the Burgundians in the Battle of Vézeronce.

524 The Franks defeated the Burgundians in the Battle of Vézeronce.

841 In the Battle of Fontenay-en-Puisaye, forces led by Charles the Bald and Louis the German defeated the armies of Lothair I of Italy and Pepin II of Aquitaine.

Published on June 25, 2015 01:30

June 24, 2015

History Trivia - outbreak of St. John's Dance in streets of Aachen, Germany

June 24

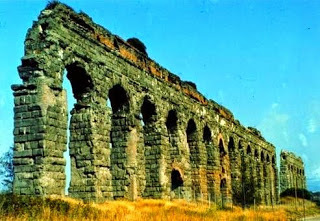

109 The Aqua Traiana was inaugurated by Emperor Trajan, the aqueduct channeled water from Lake Bracciano, 25 miles north-west of Rome.

803 Bishop Higbald of Lindisfarne died. In a communiqué to the scholar Alcuin of York (teacher at the Carolingian court at the invitation of Charlemagne), he described in graphic detail the Viking raid on Lindisfarne on 8 January 793 in which many of his monks were killed.

1374 A sudden outbreak of St. John's Dance (Dancing Plague) caused people in the streets of Aachen, Germany, to experience hallucinations and begin to jump and twitch uncontrollably until they collapsed from exhaustion. One of the most prominent theories is that victims suffered from ergot (fungus) poisoning.

109 The Aqua Traiana was inaugurated by Emperor Trajan, the aqueduct channeled water from Lake Bracciano, 25 miles north-west of Rome.

803 Bishop Higbald of Lindisfarne died. In a communiqué to the scholar Alcuin of York (teacher at the Carolingian court at the invitation of Charlemagne), he described in graphic detail the Viking raid on Lindisfarne on 8 January 793 in which many of his monks were killed.

1374 A sudden outbreak of St. John's Dance (Dancing Plague) caused people in the streets of Aachen, Germany, to experience hallucinations and begin to jump and twitch uncontrollably until they collapsed from exhaustion. One of the most prominent theories is that victims suffered from ergot (fungus) poisoning.

Published on June 24, 2015 02:00

June 23, 2015

History Trivia - Titus succeeds his father Vespasian

June 23

79 Titus succeeded his father Vespasian as the tenth Roman Emperor.

79 Titus succeeded his father Vespasian as the tenth Roman Emperor.

930 The world's oldest parliament, the Iceland Parliament, was established.

930 The world's oldest parliament, the Iceland Parliament, was established.

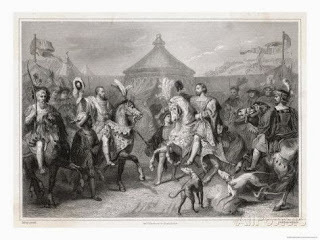

1532 Henry VIII and François I signed a secret treaty against Emperor Charles V.

1532 Henry VIII and François I signed a secret treaty against Emperor Charles V.

79 Titus succeeded his father Vespasian as the tenth Roman Emperor.

79 Titus succeeded his father Vespasian as the tenth Roman Emperor.  930 The world's oldest parliament, the Iceland Parliament, was established.

930 The world's oldest parliament, the Iceland Parliament, was established.  1532 Henry VIII and François I signed a secret treaty against Emperor Charles V.

1532 Henry VIII and François I signed a secret treaty against Emperor Charles V.

Published on June 23, 2015 01:00

June 22, 2015

History Trivia - Galileo Galilei recants

June 22

168 BC Battle of Pydna: Romans under Lucius Aemilius Paullus defeated and captured Macedonian King Perseus ending the Third Macedonian War.

1377 Richard II succeeded Edward III as king of England.

1633 The Holy Office in Rome forced Galileo Galilei to recant his view that the Sun, not the Earth, is the center of the Universe. (on Oct 31, 1992, Vatican admitted it was wrong)

168 BC Battle of Pydna: Romans under Lucius Aemilius Paullus defeated and captured Macedonian King Perseus ending the Third Macedonian War.

1377 Richard II succeeded Edward III as king of England.

1633 The Holy Office in Rome forced Galileo Galilei to recant his view that the Sun, not the Earth, is the center of the Universe. (on Oct 31, 1992, Vatican admitted it was wrong)

Published on June 22, 2015 02:00

June 21, 2015

Summer Solstice - June 21, 2015

The longest day of the year! The summer solstice occurs when the tilt of a planet's semi-axis, in either the northern or the southern hemisphere, is most inclined toward the star that it orbits.

Published on June 21, 2015 04:00

History Trivia - battle at Lake Trasimenus - Hannibal victorious

June 21

217 BC Carthaginian forces led by Hannibal destroyed a Roman army under Consul Gaius Flaminicy in a battle at Lake Trasimenus in central Italy.

1314 The Scots, under Robert the Bruce, defeated Edward II's army at Bannockburn.

1675 Christopher Wren started the rebuilding St. Paul's Cathedral in London after the Great Fire.

217 BC Carthaginian forces led by Hannibal destroyed a Roman army under Consul Gaius Flaminicy in a battle at Lake Trasimenus in central Italy.

1314 The Scots, under Robert the Bruce, defeated Edward II's army at Bannockburn.

1675 Christopher Wren started the rebuilding St. Paul's Cathedral in London after the Great Fire.

Published on June 21, 2015 02:30

June 20, 2015

Janni Styles Wins Flash Fiction Challenge

Indies Unlimited

Janni Styles is the readers’ choice in this week’s Indies Unlimited Flash Fiction Challenge.

Janni Styles is the readers’ choice in this week’s Indies Unlimited Flash Fiction Challenge.

The winning entry is rewarded with a special feature here today and a place in our collection of winners which will be published as an e-book at year end.

Without further ado, here’s the winning entry:

Guides

by Janni StylesMy left leg hurt so I couldn’t move swiftly. I soon found myself feeling very fond of the kindly dogs.

After a time, I stopped to rest on a boulder by the gravel road. An approaching vehicle rumbled toward us. The dogs sat sentry like, one either side of me. Their ears perked and their heads tilted as a rusty jeep appeared.

Two men wearing orange vests stood with their guns poised on the roll bars while the driver navigated to a gentle halt.

“Lucy, are you okay?” the handsome driver with friendly eyes asked.

“Who are you?” I asked.

“It’s okay, sweetie, let’s get you home,” the man said, helping me into the jeep.

His two burly companions had set their rifles down and were chatting amiably.

“Hey guys, see if you can limp her car home?” the driver asked.

“Sure,” the tallest guy answered as both jumped out and headed back toward the car.

The dogs leapt into the jeep when the driver called them by name.

“Are these dogs yours?” I asked.

“Yep,” he said.

My brain was so foggy, I didn’t know whether to be scared or not.

“Good thing we were hunting,” he said, “this logging road is rarely used anymore.”

His calm hand movements as he shifted gears sparked a chord in me.

“You are my husband!”

Hot tears started down my face.

“I am,” he said.

“I have PTSD!”

“Yes, you do, my sweetheart,” he said, “Yes, you do.”

Janni Styles is the readers’ choice in this week’s Indies Unlimited Flash Fiction Challenge.

Janni Styles is the readers’ choice in this week’s Indies Unlimited Flash Fiction Challenge.The winning entry is rewarded with a special feature here today and a place in our collection of winners which will be published as an e-book at year end.

Without further ado, here’s the winning entry:

Guides

by Janni StylesMy left leg hurt so I couldn’t move swiftly. I soon found myself feeling very fond of the kindly dogs.

After a time, I stopped to rest on a boulder by the gravel road. An approaching vehicle rumbled toward us. The dogs sat sentry like, one either side of me. Their ears perked and their heads tilted as a rusty jeep appeared.

Two men wearing orange vests stood with their guns poised on the roll bars while the driver navigated to a gentle halt.

“Lucy, are you okay?” the handsome driver with friendly eyes asked.

“Who are you?” I asked.

“It’s okay, sweetie, let’s get you home,” the man said, helping me into the jeep.

His two burly companions had set their rifles down and were chatting amiably.

“Hey guys, see if you can limp her car home?” the driver asked.

“Sure,” the tallest guy answered as both jumped out and headed back toward the car.

The dogs leapt into the jeep when the driver called them by name.

“Are these dogs yours?” I asked.

“Yep,” he said.

My brain was so foggy, I didn’t know whether to be scared or not.

“Good thing we were hunting,” he said, “this logging road is rarely used anymore.”

His calm hand movements as he shifted gears sparked a chord in me.

“You are my husband!”

Hot tears started down my face.

“I am,” he said.

“I have PTSD!”

“Yes, you do, my sweetheart,” he said, “Yes, you do.”

Published on June 20, 2015 06:55

Why ‘Bad King John’ was actually Good

History Extra

King John wasn't so 'Bad', argues Graham E Seel. © North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy

King John wasn't so 'Bad', argues Graham E Seel. © North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy

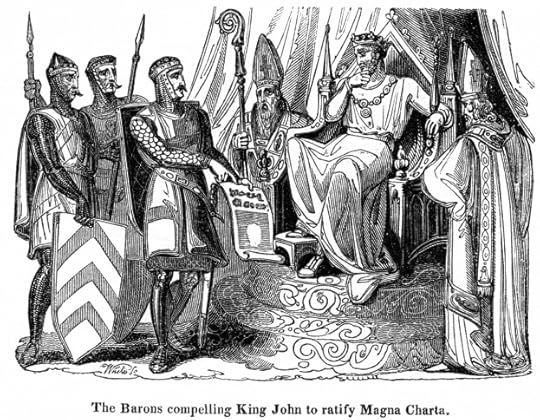

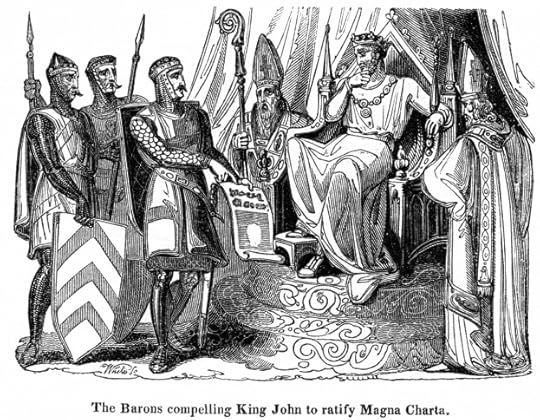

After a great political struggle, King John was forced to accept the terms of his rebellious barons and seal Magna Carta at Runnymede in June 1215 – an anniversary marked both in Britain and the United States earlier this week. But was ‘Bad King John’, as he has been famously nicknamed, really as ‘bad’ as history has made him out to be?

Here, writing for History Extra, author Graham E Seel considers John’s governance, and asks whether it is time to change our opinions of him.

One might have hoped that the 800th anniversary of the sealing of Magna Carta would have provided at least some oxygen to the argument that ‘Bad King John’ was perhaps not too ‘Bad’ after all; and – whisper it – that in some ways this traditionally most maligned of monarchs was perhaps really rather Good.

Instead, the anticipated tsunami of popular and learned articles collectively assert, inter alia, that John was at once cruel and coercive, treacherous and tyrannical, pusillanimous and pitiful, lazy and lackluster. For the large part it seems that, 800 years later, opinion has broadly backed Matthew Paris, the 13th-century chronicler who alleged that John’s greatest achievement was, by dying, to make yet more foul the existing foulness of Hell: John was not only Bad; he was diabolical.

Popular understanding of Magna Carta has significantly stunted debate on the nature and achievement of John. Magna Carta, we are told, stands for the rule of law. Invoked by those in 17th-century England who sought to thwart the allegedly despotic tendencies of Charles I, and latterly employed by the American Revolutionaries in their making of the United States Bill of Rights in 1789, Magna Carta has become totemic of the liberties by which western societies identify themselves.

Indeed, this tendency has travelled so far that Magna Carta has, according to G Hindley, “acquired an almost mystic incantatory quality”. This, he claims, is partly evidenced by the fact that the government sponsored the Magna Carta 800th anniversary website, which currently asserts that Magna Carta “is the foundation stone supporting the freedoms enjoyed today by hundreds of millions of people in more than 100 countries”.

These are powerful words, and it follows that if John ignored Magna Carta – which he did – then it must surely be the case that he was indeed malign. The ever-growing extent to which Magna Carta is celebrated and elevated necessarily means that, in equal and opposite degree, the reputation of John is tarnished and diminished. In this context, to argue that John was anything other than ‘Bad’ seems inappropriate and somewhat unbelievable.

However, the Magna Carta that John chose to ignore did not purport to be a constitutional document adumbrating and guaranteeing liberties to all English people. The Magna Carta of 1215 (it is important to realise that there were many reissues of Magna Carta after the reign of John, each different to the one presented to John) is better understood as a set of flawed peace terms designed to heal the incipient civil war between John and an element of rebellious barons.

In order to try and bind John to their terms, the barons insisted that John accept a committee of 25 of their number empowered to police and enforce Magna Carta by seizing John’s castles and assets when he was judged – by them, and against criteria put forth by them – to have transgressed.

No medieval monarch could have accepted for any length of time the Magna Carta of 1215, for it clearly rendered the king a phantom of a monarch. Indeed, so extreme was this impact that it is not beyond sensible contemplation that the ambition of the rebel barons was not to obtain a lasting peace, but instead absolutely to provoke John to break the newly agreed terms so that they could seize his largesse. John did indeed overturn Magna Carta, but arguably any medieval monarch would have done the same. The Magna Carta of 1215 is not the Magna Carta of popular imagination.

(Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Popular representations of events at Runnymede in June 1215 would also have us believe that leading rebel barons such as Eustace de Vesci and Robert Fitzwalter were revered freedom fighters. In fact, they are better understood as tight-knuckled, low browed feudal reactionaries kicking against John’s increasingly efficacious administration.

A considerable body of evidence in the form of pipe rolls, charters and letters patent indicates strongly that John was highly effective – perhaps too effective – in mobilizing the resources of his kingdom and in imposing the royal will upon the population at large. This apparently incontestable evidence shows John to have been possessed of vigour and vim, constantly on the move enforcing Angevin aspirations. Ironically, the very fact that John faced rebellion in 1215 is itself indicative of the fact that his government had bite as well as bark.

Moreover, even though chronicle sources allege that the whole of the baronage was united against John, this was clearly not the case – not least because there would have been no possibility of civil war if there had not been two sides, each with the wherewithal to resist the other. Indeed, by the spring of 1215, it has been estimated that of England’s 197 baronies only 39 were in active opposition to the king, with perhaps the same number acting in his support.

Nor is it true that John antagonized elements of the baronage because he was lacking in martial prowess, or that the king was ‘Softsword’, as the chroniclers assert. His reluctance to commit to pitched battles was entirely conventional in an age when all leaders preferred to avoid them – John’s arch-enemy, Philip Augustus, King of France (r1180–1223) shied away from a setpiece battle at least as frequently as his protagonist. We should not mistake John’s military caution for cowardice. Instead, John prosecuted siege warfare with the sort of energy, determination and success that is usually only spoken of in reference to Henry II and Richard I.

Thus, we see him, for example, razing the walls and castle of Le Mans in 1200, assaulting the forces besieging Mirebeau in 1202 (having covered a distance of 80 miles in 48 hours), marching upon Montauban in 1206 and pressing the siege of Rochester castle in 1215 – an event that the leading authority of castles and castle warfare in this period considers was “the greatest operation in England up to that time” (RA Brown).

John was also an effective strategist. His plan to relieve the siege of Chateau-Gaillard in 1203 by arranging a simultaneous assault from land and amphibious forces has been described as “a masterpiece of ingenuity”by K Norgate. Even John’s much-criticised twin-pronged invasion of France in 1214 (which culminated in the disastrous battle of Bouvines on 27 July 1214) achieved its basic aim of dividing the Capetian forces.

John’s alleged lasciviousness and acts of cruelty have been presented as further character traits that antagonised the barons and thus prevented him from delivering strong kingship. Lusting after the wives and daughters of those men he relied upon to deliver the royal command was no doubt a problem in a world where private relationships were the stuff of high politics. Yet nearly all medieval kings took mistresses. Indeed, William the Conqueror’s loyalty to his wife, Matilda, was the subject of perplexed comment.

If John was indeed a “smutty minded groper” (CJ Tyerman), he remained a rake rather than a rogue. His marriage to Isabella of Angouleme when she was unlikely to have been more than 15 and quite possibly as young as nine has prompted a flood of accusations that John was a 13th-century Humbert Humbert. Yet marriage at an early age was commonplace at the time – a survey of the marriage arrangements of John’s contemporaries leads to the conclusion that the Angevin king had an eye for an older women!

Isabella of Angouleme, queen consort of King John. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Further contextual analysis also diminishes the charge that John was a perverted purveyor of acts of cruelty. The evidence does not permit John to be charged definitively with killing his nephew, Arthur, but the king nevertheless had arguably legitimate reasons to undertake such an act since Arthur (a 16-year-old boy) had put himself at the head of a rebellion sponsored by Philip Augustus.

Similarly, it is not proven that John starved Matilda de Braose and her son to death in Corfe Castle, but if he did so it was because of her refusal to offer her sons as hostages in order to trim the rebellious behaviour of their father. Yet hostage taking was part-and-parcel of medieval government, and as such it follows that they sometimes paid the ultimate price. Indeed, King Stephen was seen as weak for refusing to hang the son of Marshal when the latter broke the terms of an agreement with the king.

If John is guilty of cruelty, then what of Richard I in 1191 when, following a dispute about the terms upon which Acre had been surrendered, he ordered the killing of 2,700 Muslim prisoners? What of Henry V, who during the battle of Agincourt in 1415 ordered the killing of several thousand French prisoners? What of John’s father, Henry II who, having taken 22 hostages from the Welsh in 1165, ordered that the males among them – some of them sons of princes – be blinded and castrated, and that the females should have their noses and ears cut off? Medieval monarchs were expected to be fierce, and John fulfilled those expectations.

The Barnwell annalist, Walter Of Coventry, concluded that John “was indeed a great prince but less than successful [and that]…he met with both kinds of luck”. John was certainly unlucky in that his reign coincided with probably the two most accomplished leaders of the Middle Ages – Philip Augustus and Pope Innocent III (r1198–1216) – and he was certainly unlucky in that the Angevin ‘empire’ he had inherited in 1199 was increasingly ungovernable and assaulted by fissiparous tendencies. Yet, I argue, he was not “less than successful”. John’s achievement is that he held things together for as long as he did.

Graham Seel is head of history at St Paul’s School in London. He is the author of King John: An Underrated King (Anthem Press, 2012). He has recently released ‘King John’, an app version of the book available on iPad.

Click here to listen to our King John podcast.

King John wasn't so 'Bad', argues Graham E Seel. © North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy

King John wasn't so 'Bad', argues Graham E Seel. © North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy After a great political struggle, King John was forced to accept the terms of his rebellious barons and seal Magna Carta at Runnymede in June 1215 – an anniversary marked both in Britain and the United States earlier this week. But was ‘Bad King John’, as he has been famously nicknamed, really as ‘bad’ as history has made him out to be?

Here, writing for History Extra, author Graham E Seel considers John’s governance, and asks whether it is time to change our opinions of him.

One might have hoped that the 800th anniversary of the sealing of Magna Carta would have provided at least some oxygen to the argument that ‘Bad King John’ was perhaps not too ‘Bad’ after all; and – whisper it – that in some ways this traditionally most maligned of monarchs was perhaps really rather Good.

Instead, the anticipated tsunami of popular and learned articles collectively assert, inter alia, that John was at once cruel and coercive, treacherous and tyrannical, pusillanimous and pitiful, lazy and lackluster. For the large part it seems that, 800 years later, opinion has broadly backed Matthew Paris, the 13th-century chronicler who alleged that John’s greatest achievement was, by dying, to make yet more foul the existing foulness of Hell: John was not only Bad; he was diabolical.

Popular understanding of Magna Carta has significantly stunted debate on the nature and achievement of John. Magna Carta, we are told, stands for the rule of law. Invoked by those in 17th-century England who sought to thwart the allegedly despotic tendencies of Charles I, and latterly employed by the American Revolutionaries in their making of the United States Bill of Rights in 1789, Magna Carta has become totemic of the liberties by which western societies identify themselves.

Indeed, this tendency has travelled so far that Magna Carta has, according to G Hindley, “acquired an almost mystic incantatory quality”. This, he claims, is partly evidenced by the fact that the government sponsored the Magna Carta 800th anniversary website, which currently asserts that Magna Carta “is the foundation stone supporting the freedoms enjoyed today by hundreds of millions of people in more than 100 countries”.

These are powerful words, and it follows that if John ignored Magna Carta – which he did – then it must surely be the case that he was indeed malign. The ever-growing extent to which Magna Carta is celebrated and elevated necessarily means that, in equal and opposite degree, the reputation of John is tarnished and diminished. In this context, to argue that John was anything other than ‘Bad’ seems inappropriate and somewhat unbelievable.

However, the Magna Carta that John chose to ignore did not purport to be a constitutional document adumbrating and guaranteeing liberties to all English people. The Magna Carta of 1215 (it is important to realise that there were many reissues of Magna Carta after the reign of John, each different to the one presented to John) is better understood as a set of flawed peace terms designed to heal the incipient civil war between John and an element of rebellious barons.

In order to try and bind John to their terms, the barons insisted that John accept a committee of 25 of their number empowered to police and enforce Magna Carta by seizing John’s castles and assets when he was judged – by them, and against criteria put forth by them – to have transgressed.

No medieval monarch could have accepted for any length of time the Magna Carta of 1215, for it clearly rendered the king a phantom of a monarch. Indeed, so extreme was this impact that it is not beyond sensible contemplation that the ambition of the rebel barons was not to obtain a lasting peace, but instead absolutely to provoke John to break the newly agreed terms so that they could seize his largesse. John did indeed overturn Magna Carta, but arguably any medieval monarch would have done the same. The Magna Carta of 1215 is not the Magna Carta of popular imagination.

(Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Popular representations of events at Runnymede in June 1215 would also have us believe that leading rebel barons such as Eustace de Vesci and Robert Fitzwalter were revered freedom fighters. In fact, they are better understood as tight-knuckled, low browed feudal reactionaries kicking against John’s increasingly efficacious administration.

A considerable body of evidence in the form of pipe rolls, charters and letters patent indicates strongly that John was highly effective – perhaps too effective – in mobilizing the resources of his kingdom and in imposing the royal will upon the population at large. This apparently incontestable evidence shows John to have been possessed of vigour and vim, constantly on the move enforcing Angevin aspirations. Ironically, the very fact that John faced rebellion in 1215 is itself indicative of the fact that his government had bite as well as bark.

Moreover, even though chronicle sources allege that the whole of the baronage was united against John, this was clearly not the case – not least because there would have been no possibility of civil war if there had not been two sides, each with the wherewithal to resist the other. Indeed, by the spring of 1215, it has been estimated that of England’s 197 baronies only 39 were in active opposition to the king, with perhaps the same number acting in his support.

Nor is it true that John antagonized elements of the baronage because he was lacking in martial prowess, or that the king was ‘Softsword’, as the chroniclers assert. His reluctance to commit to pitched battles was entirely conventional in an age when all leaders preferred to avoid them – John’s arch-enemy, Philip Augustus, King of France (r1180–1223) shied away from a setpiece battle at least as frequently as his protagonist. We should not mistake John’s military caution for cowardice. Instead, John prosecuted siege warfare with the sort of energy, determination and success that is usually only spoken of in reference to Henry II and Richard I.

Thus, we see him, for example, razing the walls and castle of Le Mans in 1200, assaulting the forces besieging Mirebeau in 1202 (having covered a distance of 80 miles in 48 hours), marching upon Montauban in 1206 and pressing the siege of Rochester castle in 1215 – an event that the leading authority of castles and castle warfare in this period considers was “the greatest operation in England up to that time” (RA Brown).

John was also an effective strategist. His plan to relieve the siege of Chateau-Gaillard in 1203 by arranging a simultaneous assault from land and amphibious forces has been described as “a masterpiece of ingenuity”by K Norgate. Even John’s much-criticised twin-pronged invasion of France in 1214 (which culminated in the disastrous battle of Bouvines on 27 July 1214) achieved its basic aim of dividing the Capetian forces.

John’s alleged lasciviousness and acts of cruelty have been presented as further character traits that antagonised the barons and thus prevented him from delivering strong kingship. Lusting after the wives and daughters of those men he relied upon to deliver the royal command was no doubt a problem in a world where private relationships were the stuff of high politics. Yet nearly all medieval kings took mistresses. Indeed, William the Conqueror’s loyalty to his wife, Matilda, was the subject of perplexed comment.

If John was indeed a “smutty minded groper” (CJ Tyerman), he remained a rake rather than a rogue. His marriage to Isabella of Angouleme when she was unlikely to have been more than 15 and quite possibly as young as nine has prompted a flood of accusations that John was a 13th-century Humbert Humbert. Yet marriage at an early age was commonplace at the time – a survey of the marriage arrangements of John’s contemporaries leads to the conclusion that the Angevin king had an eye for an older women!

Isabella of Angouleme, queen consort of King John. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Further contextual analysis also diminishes the charge that John was a perverted purveyor of acts of cruelty. The evidence does not permit John to be charged definitively with killing his nephew, Arthur, but the king nevertheless had arguably legitimate reasons to undertake such an act since Arthur (a 16-year-old boy) had put himself at the head of a rebellion sponsored by Philip Augustus.

Similarly, it is not proven that John starved Matilda de Braose and her son to death in Corfe Castle, but if he did so it was because of her refusal to offer her sons as hostages in order to trim the rebellious behaviour of their father. Yet hostage taking was part-and-parcel of medieval government, and as such it follows that they sometimes paid the ultimate price. Indeed, King Stephen was seen as weak for refusing to hang the son of Marshal when the latter broke the terms of an agreement with the king.

If John is guilty of cruelty, then what of Richard I in 1191 when, following a dispute about the terms upon which Acre had been surrendered, he ordered the killing of 2,700 Muslim prisoners? What of Henry V, who during the battle of Agincourt in 1415 ordered the killing of several thousand French prisoners? What of John’s father, Henry II who, having taken 22 hostages from the Welsh in 1165, ordered that the males among them – some of them sons of princes – be blinded and castrated, and that the females should have their noses and ears cut off? Medieval monarchs were expected to be fierce, and John fulfilled those expectations.

The Barnwell annalist, Walter Of Coventry, concluded that John “was indeed a great prince but less than successful [and that]…he met with both kinds of luck”. John was certainly unlucky in that his reign coincided with probably the two most accomplished leaders of the Middle Ages – Philip Augustus and Pope Innocent III (r1198–1216) – and he was certainly unlucky in that the Angevin ‘empire’ he had inherited in 1199 was increasingly ungovernable and assaulted by fissiparous tendencies. Yet, I argue, he was not “less than successful”. John’s achievement is that he held things together for as long as he did.

Graham Seel is head of history at St Paul’s School in London. He is the author of King John: An Underrated King (Anthem Press, 2012). He has recently released ‘King John’, an app version of the book available on iPad.

Click here to listen to our King John podcast.

Published on June 20, 2015 06:46

200 years later, experts seek to unearth the Battle of Waterloo’s secrets

Fox News

Performers take part in the re-enactment of the battle of Ligny, during the bicentennial celebrations for the Battle of Waterloo, in Ligny, Belgium, June 14, 2015. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)

On June 18, 1815 the course of European history was changed when French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte found himself outmatched on the fields near Waterloo, Belgium. Britain's Duke of Wellington would become a celebrated hero and eventually Prime Minister, while Napoleon would retreat to Paris and soon after head into exile on the island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic. It all came down to a cool day in June that began with heavy rains. By nightfall some 10 hours after it began, the battle was over, as was the French leader's 100-day comeback.

For 200 years the Battle of Waterloo has been debated time and time again. In part it has been argued that it was a battle Napoleon could have won, and even should have won. However, the modern thinking is that the battle actually might not have been as decisive as suggested.

Related: First complete Battle of Waterloo skeleton identified as German soldier

"In the end, the battle probably did not matter much. Had Napoleon won, it would have been very embarrassing for the British, and Wellington's reputation would not have been as great," Professor Michael Broers of the history department at the University of Oxford, told FoxNews.com. "However, there was a very large, battle hardened Russian army in Western Europe, which would have seen Napoleon off. The Allies were not prepared to give in."

A Smaller Battle

One other facet of Waterloo that is often overlooked is that in terms of Napoleonic Era battles it wasn't the largest by any means. While Napoleon is remembered for being on the short side, a common misconception is that Waterloo was the titanic battle to end all battles, but this is far from the truth. It was an important battle, no doubt, but when compared to other engagements Waterloo was quite smaller.

"There had been much bigger battles," Paul O'Keeffe, author of “Waterloo: The Aftermath” told FoxNews.com. "The Battle of Leipzig in 1813 had some 90,000 dead and wounded, whereas Waterloo had some 45,000 dead and wounded."

Related Image Frenchman Frank Samson takes part in the re-enactment of the battle of Ligny, as French Emperor Napoleon, during the bicentennial celebrations for the Battle of Waterloo, in Ligny, Belgium, June 14, 2015. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)

Frenchman Frank Samson takes part in the re-enactment of the battle of Ligny, as French Emperor Napoleon, during the bicentennial celebrations for the Battle of Waterloo, in Ligny, Belgium, June 14, 2015. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)

This is still a tragically high number, O'Keeffe agreed, but the other significant detail is that these men fell in a relatively small patch of land in Belgium on that fateful June day.

"Waterloo was fought on a much smaller area than other battles of the era, just five square miles," said O'Keeffe. "Compare that to Leipzig, which was fought over 21 miles. The carnage at Waterloo was thus horrific with so many dead, as well as some 7,000 dead and maimed horses!"

Napoleon may have met his Waterloo but he didn't technically surrender there and instead retreated back to Paris. Throughout the summer of 1815 there were a number of small engagements and the final peace wasn't signed until November 20, 1815.

So why does Waterloo earn its place in history?

"While there was still fighting this battle in essence brought to an end of nearly 20 years of continuous warfare in Europe," said O'Keefe. "There were decisive battles but this was really a conclusive battle as it knocked out the French entirely."

The Fog of War

If there is one word that could truly describe the situation on the ground on June 18, 1815 it was probably "confusion." This is noted by several authors and historians. Part of the reason was that the colorful uniforms of the day didn't make it easy to distinguish friend from foe.

At one point the British 12th Light Dragoons, who wore blue coats as opposed to the more infamous "red coats" that were donned by the British infantry, came under friendly fire; while later in the day the Prussian black uniforms may have been mistaken for French blue. That latter and seemingly simple mistake may have cost Napoleon the battle and his empire.

"Napoleon knew that Marshal Grouchy was following the Prussians, and he hoped it was Grouchy who was approaching in the late afternoon," said Tim Clayton, author of “Waterloo: Four Days that Changed Europe's Destiny”.

The Prussians were not the only British allies at Waterloo who from a distance resembled their foes! Clayton noted that the Dutch Orange-Nassau Regiment wore blue uniforms with tall French style shakos, or hats.

"That added an extra layer of confusion and that took a little while to sort out," he told FoxNews.com. "This may have caused Napoleon to be even more optimistic especially as the advancing Prussians fired on the Nassau Regiment (who were in fact their allies). This may have helped convince Napoleon that the Prussians were actually Grouchy's troops after all! Waterloo is a classic example of the fog of war. If only they had mobile phones."

Beyond phones the French could have benefitted from GPS – or at least better maps. But even without the most accurate maps, this may have had little effect on the battle.

"The last little 'sensation' reported around Waterloo is that Napoleon was using a map that was wrongly printed and therefore 'lost' the battle, or the result may have been different," explained Robert Kershaw, author of “24 Hours at Waterloo: 18th June 1815”. "As an ex-military man, anyone trying to explain a map topographical error affecting the outcome of a battle such as this has got to be wired to the moon. What people tend to miss is that the battle certainly was, as Wellington explained, 'a close thing.'"

Wellington, known as “the Iron Duke” refused to comment on the battle for years.

"During a battle it is clear no one knows what the hell was going on," said O'Keeffe. "But afterward the Duke of Wellington refused to give any account of the battle. There were 40 publications in the [following] six months that brought out account of battle. Wellington refused and didn't give account. The Duke did suggest that the battle was like a ball or dance, where you don't know what is happening on the other side of the room. Simply put no-one could understand what was going on beyond their sector."

Napoleon's Health

The general wellbeing and health of Napoleon has also been called into question since his defeat at Waterloo. It has been argued over the years that he wasn't feeling well and even the brief time he spent in the saddle may have been far more than he could handle.

"It is very difficult to know how ill he was," added Clayton. "We must too remember he wasn't the young man he had been at the outset of his career and he must have been exhausted by that stage of the 100 days since his return from exile."

Not only did he have a military campaign to manage but he had to dictate to his secretaries about the state of the government and happenings in Paris each night. Rest might have helped, but it could also be argued that the respite from the front may have cost him the battle.

"On June 15 he reportedly had a comfortable night sleep in the town of Charleroi, yet he said in exile he wished he had stayed at the front lines so he could have kept better track of the Prussians," noted Clayton.

Digging the Battlefield

What is beneath the ground in Waterloo in the Belgian countryside could also shed more light on the battle. Recently the first complete skeleton of a soldier killed at the battle was recovered, and identified as Friedrich Brandt, a member of the King's German Legion who served under Britain's King George III. Brandt, who was reportedly just 23-years old when he fell, was killed when a musket ball lodged in his ribs.

This soldier's remains likely won't be the last to be recovered.

"The entire battlefield was cleared almost as soon as the fighting ended as locals and soldiers looted it for anything of value," said O'Keeffe. "Moreover it is really a mass grave as the soldiers were buried or burned in the thousands. We have to remember this was a time before there were war cemeteries."

The Waterloo Uncovered project, which began this year, aims to explore the battlefield and reveal secrets that may have been buried for the last 200 years. An international team began the first major excavation at Hougoumont Farm, which proved to be a decisive position in the British lines as 4,000 British troops successfully held off some 15,000 French soldiers throughout the afternoon.

"I suspect they are hoping to find the mass burial pits located near the farm," said Clayton. "Already excavations have found a surprising number of bullets, but because the battlefield has been looted there is still a question about how much this or other efforts will find."

It isn't just archaeologists and historians who are helping sift through the dirt at Waterloo. In April experts in soil sensing from Ghent University in Belgium used mobile multi-receiver electromagnetic induction (EMI) sensors as well as magnetometers to survey the landscape. This will help pinpoint areas that could be of potential interest to archaeologists.

The focus is on the Hougoumont Farm, explained Tony Pollard, director of the centre for battlefield archaeology at the University of Glasgow, who has been working closely with the Waterloo Uncovered project.

"The farm buildings still exist, apart from the chateau, which burned down during the battle. We began with a geophysical survey, which gives us an impression of below ground activity as magnetic or electrical anomalies," he told FoxNews.com. "Metal detector survey has demonstrated that illegal metal detecting has denuded the amount of battle related material, such as buttons and musket balls, in the ground. There is still enough left to tell us a story about how and where things occurred but if things continue as they are Hougoumont will be 'hoovered' (vacuumed) up by relic collectors over the next few years."

He added that the scatter of musket and pistol balls may suggest that the road into the woods nearby was hard fought over – possibly harder fought than past understanding.

"Even after just a few days’ work we have learned a lot more than we knew before - we are not going to change the course of the battle through the archaeology but it is providing a new level of detail, specifically at the moment in the area of the wood," Pollard said. "It is very early days yet and we hope in the long term to move out onto other areas of the battlefield."

While this year marks the 200th anniversary of the famous battle the Waterloo Uncovered project will continue over the coming five years with the next phase due to start in summer of 2016. Perhaps these discoveries will shed more light on the battle that reshaped the political map of Europe for the next 100 years.

Performers take part in the re-enactment of the battle of Ligny, during the bicentennial celebrations for the Battle of Waterloo, in Ligny, Belgium, June 14, 2015. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)

On June 18, 1815 the course of European history was changed when French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte found himself outmatched on the fields near Waterloo, Belgium. Britain's Duke of Wellington would become a celebrated hero and eventually Prime Minister, while Napoleon would retreat to Paris and soon after head into exile on the island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic. It all came down to a cool day in June that began with heavy rains. By nightfall some 10 hours after it began, the battle was over, as was the French leader's 100-day comeback.

For 200 years the Battle of Waterloo has been debated time and time again. In part it has been argued that it was a battle Napoleon could have won, and even should have won. However, the modern thinking is that the battle actually might not have been as decisive as suggested.

Related: First complete Battle of Waterloo skeleton identified as German soldier

"In the end, the battle probably did not matter much. Had Napoleon won, it would have been very embarrassing for the British, and Wellington's reputation would not have been as great," Professor Michael Broers of the history department at the University of Oxford, told FoxNews.com. "However, there was a very large, battle hardened Russian army in Western Europe, which would have seen Napoleon off. The Allies were not prepared to give in."

A Smaller Battle

One other facet of Waterloo that is often overlooked is that in terms of Napoleonic Era battles it wasn't the largest by any means. While Napoleon is remembered for being on the short side, a common misconception is that Waterloo was the titanic battle to end all battles, but this is far from the truth. It was an important battle, no doubt, but when compared to other engagements Waterloo was quite smaller.

"There had been much bigger battles," Paul O'Keeffe, author of “Waterloo: The Aftermath” told FoxNews.com. "The Battle of Leipzig in 1813 had some 90,000 dead and wounded, whereas Waterloo had some 45,000 dead and wounded."

Related Image

Frenchman Frank Samson takes part in the re-enactment of the battle of Ligny, as French Emperor Napoleon, during the bicentennial celebrations for the Battle of Waterloo, in Ligny, Belgium, June 14, 2015. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)

Frenchman Frank Samson takes part in the re-enactment of the battle of Ligny, as French Emperor Napoleon, during the bicentennial celebrations for the Battle of Waterloo, in Ligny, Belgium, June 14, 2015. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)This is still a tragically high number, O'Keeffe agreed, but the other significant detail is that these men fell in a relatively small patch of land in Belgium on that fateful June day.

"Waterloo was fought on a much smaller area than other battles of the era, just five square miles," said O'Keeffe. "Compare that to Leipzig, which was fought over 21 miles. The carnage at Waterloo was thus horrific with so many dead, as well as some 7,000 dead and maimed horses!"

Napoleon may have met his Waterloo but he didn't technically surrender there and instead retreated back to Paris. Throughout the summer of 1815 there were a number of small engagements and the final peace wasn't signed until November 20, 1815.

So why does Waterloo earn its place in history?

"While there was still fighting this battle in essence brought to an end of nearly 20 years of continuous warfare in Europe," said O'Keefe. "There were decisive battles but this was really a conclusive battle as it knocked out the French entirely."

The Fog of War

If there is one word that could truly describe the situation on the ground on June 18, 1815 it was probably "confusion." This is noted by several authors and historians. Part of the reason was that the colorful uniforms of the day didn't make it easy to distinguish friend from foe.

At one point the British 12th Light Dragoons, who wore blue coats as opposed to the more infamous "red coats" that were donned by the British infantry, came under friendly fire; while later in the day the Prussian black uniforms may have been mistaken for French blue. That latter and seemingly simple mistake may have cost Napoleon the battle and his empire.

"Napoleon knew that Marshal Grouchy was following the Prussians, and he hoped it was Grouchy who was approaching in the late afternoon," said Tim Clayton, author of “Waterloo: Four Days that Changed Europe's Destiny”.

The Prussians were not the only British allies at Waterloo who from a distance resembled their foes! Clayton noted that the Dutch Orange-Nassau Regiment wore blue uniforms with tall French style shakos, or hats.

"That added an extra layer of confusion and that took a little while to sort out," he told FoxNews.com. "This may have caused Napoleon to be even more optimistic especially as the advancing Prussians fired on the Nassau Regiment (who were in fact their allies). This may have helped convince Napoleon that the Prussians were actually Grouchy's troops after all! Waterloo is a classic example of the fog of war. If only they had mobile phones."

Beyond phones the French could have benefitted from GPS – or at least better maps. But even without the most accurate maps, this may have had little effect on the battle.

"The last little 'sensation' reported around Waterloo is that Napoleon was using a map that was wrongly printed and therefore 'lost' the battle, or the result may have been different," explained Robert Kershaw, author of “24 Hours at Waterloo: 18th June 1815”. "As an ex-military man, anyone trying to explain a map topographical error affecting the outcome of a battle such as this has got to be wired to the moon. What people tend to miss is that the battle certainly was, as Wellington explained, 'a close thing.'"

Wellington, known as “the Iron Duke” refused to comment on the battle for years.

"During a battle it is clear no one knows what the hell was going on," said O'Keeffe. "But afterward the Duke of Wellington refused to give any account of the battle. There were 40 publications in the [following] six months that brought out account of battle. Wellington refused and didn't give account. The Duke did suggest that the battle was like a ball or dance, where you don't know what is happening on the other side of the room. Simply put no-one could understand what was going on beyond their sector."

Napoleon's Health

The general wellbeing and health of Napoleon has also been called into question since his defeat at Waterloo. It has been argued over the years that he wasn't feeling well and even the brief time he spent in the saddle may have been far more than he could handle.

"It is very difficult to know how ill he was," added Clayton. "We must too remember he wasn't the young man he had been at the outset of his career and he must have been exhausted by that stage of the 100 days since his return from exile."

Not only did he have a military campaign to manage but he had to dictate to his secretaries about the state of the government and happenings in Paris each night. Rest might have helped, but it could also be argued that the respite from the front may have cost him the battle.

"On June 15 he reportedly had a comfortable night sleep in the town of Charleroi, yet he said in exile he wished he had stayed at the front lines so he could have kept better track of the Prussians," noted Clayton.

Digging the Battlefield

What is beneath the ground in Waterloo in the Belgian countryside could also shed more light on the battle. Recently the first complete skeleton of a soldier killed at the battle was recovered, and identified as Friedrich Brandt, a member of the King's German Legion who served under Britain's King George III. Brandt, who was reportedly just 23-years old when he fell, was killed when a musket ball lodged in his ribs.

This soldier's remains likely won't be the last to be recovered.

"The entire battlefield was cleared almost as soon as the fighting ended as locals and soldiers looted it for anything of value," said O'Keeffe. "Moreover it is really a mass grave as the soldiers were buried or burned in the thousands. We have to remember this was a time before there were war cemeteries."

The Waterloo Uncovered project, which began this year, aims to explore the battlefield and reveal secrets that may have been buried for the last 200 years. An international team began the first major excavation at Hougoumont Farm, which proved to be a decisive position in the British lines as 4,000 British troops successfully held off some 15,000 French soldiers throughout the afternoon.

"I suspect they are hoping to find the mass burial pits located near the farm," said Clayton. "Already excavations have found a surprising number of bullets, but because the battlefield has been looted there is still a question about how much this or other efforts will find."

It isn't just archaeologists and historians who are helping sift through the dirt at Waterloo. In April experts in soil sensing from Ghent University in Belgium used mobile multi-receiver electromagnetic induction (EMI) sensors as well as magnetometers to survey the landscape. This will help pinpoint areas that could be of potential interest to archaeologists.

The focus is on the Hougoumont Farm, explained Tony Pollard, director of the centre for battlefield archaeology at the University of Glasgow, who has been working closely with the Waterloo Uncovered project.

"The farm buildings still exist, apart from the chateau, which burned down during the battle. We began with a geophysical survey, which gives us an impression of below ground activity as magnetic or electrical anomalies," he told FoxNews.com. "Metal detector survey has demonstrated that illegal metal detecting has denuded the amount of battle related material, such as buttons and musket balls, in the ground. There is still enough left to tell us a story about how and where things occurred but if things continue as they are Hougoumont will be 'hoovered' (vacuumed) up by relic collectors over the next few years."

He added that the scatter of musket and pistol balls may suggest that the road into the woods nearby was hard fought over – possibly harder fought than past understanding.

"Even after just a few days’ work we have learned a lot more than we knew before - we are not going to change the course of the battle through the archaeology but it is providing a new level of detail, specifically at the moment in the area of the wood," Pollard said. "It is very early days yet and we hope in the long term to move out onto other areas of the battlefield."

While this year marks the 200th anniversary of the famous battle the Waterloo Uncovered project will continue over the coming five years with the next phase due to start in summer of 2016. Perhaps these discoveries will shed more light on the battle that reshaped the political map of Europe for the next 100 years.

Published on June 20, 2015 06:39