MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 164

July 14, 2015

Fighting for freedom: the storming of the Bastille and the French Revolution

History Extra

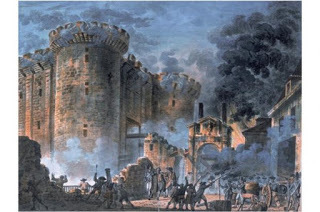

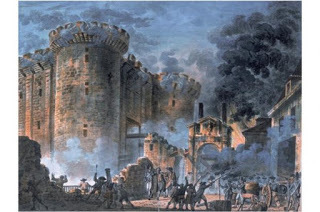

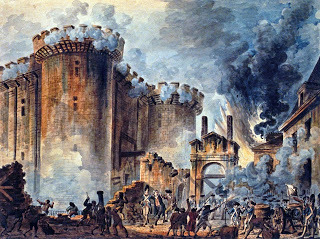

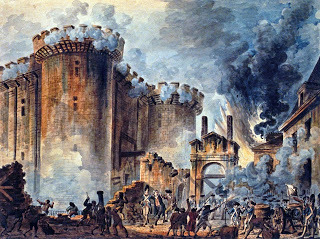

A contemporary illustration of the Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789. (Musee Carnavalet-AKG Images)

A contemporary illustration of the Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789. (Musee Carnavalet-AKG Images)

1789–1815: The world in revoltDavid Andress explains how the events of 1789 were an attempt to strip society of the inequalities of privilege, at a time when ‘freedom’ had a very confused meaningThe medieval fortress-prison of the Bastille loomed over eastern Paris. For centuries the enemies and victims of royal power had been carried there in shuttered coaches, and rumours ran of unspeakable tortures in its dungeons. On 14 July 1789 Parisians stormed the fortress, their rage against aristocratic enemies they thought ready to destroy the city to save their privilege driving some to suicidal bravery.

Men leapt over rooftops to smash drawbridge chains, others dismantled cannon and hauled them by hand over barricades. The tiny garrison yielded on the point of being overwhelmed, and at the news, royal troops elsewhere in the city packed up and marched away, their officers unwilling to try their loyalty against the triumphant people.

The storming of the Bastille was the high-water mark of a wave of insurrection that swept France in the summer of 1789. Events that created the very idea of ‘revolution’ as the modern world was to know it, as a complete overthrowing of an old order, followed a failed attempt to prop up an absolute monarchy.

That monarchy had bankrupted itself, in one of the greatest ironies of this age, paying for a war of liberation halfway around the world. When the French king Louis XVI heeded the enthusiasts for American independence and sent his troops and fleets to fight the British Empire in 1778, he thought he was dealing a death-blow to an age-old foe. In fact, he launched a process that would make Britain an even more dominant global power than it had been before the United States broke free. But he would also create, against his will, a culture of equality and rights with a disputed heritage all the way to the present day.

A battle for the regencyFrance’s ancient enemy, Britain, was facing its own crisis as 1789 dawned. King George III had fallen into raving mania, and a bitter political battle was under way for the powers of a regency. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, after five years in office as the country’s youngest ever premier, had never shaken off the view of his opponents that his rule was an unconstitutional imposition. Placed in office in 1783 by the king’s favour, his government had faced threats of impeachment before a hard-fought 1784 election had given him a working majority. Now the opposition, led by Charles James Fox, saw the chance to eject Pitt when their royal patron, the Prince of Wales, took on the regency.

In America a transition scarcely less delicate or contested was in train. The years after independence in 1783 were a time of political and fiscal disorder. For two years the much-disputed form of a new constitution for the new nation crept towards fulfilment. ‘Federalists’ and ‘Antifederalists’ clashed vigorously, and occasionally violently, over the powers of central government, and though George Washington was unanimously chosen in January 1789 to be the first president, many still feared that the new power-structure would subject them to a tyranny as great as the British one they had escaped.

At stake in all of these countries was a tangled web of ideas about the meaning of freedom, its connection to the concept of rights, and the besetting question of whether such terms covered the privileged possessions of a few, or were the natural heritage of all. For the Anglo-American world, freedom and rights had first been seen as the historical consequence of a very particular evolution.

From the medieval days of Magna Carta and the time-honoured maxims of English Common Law, radicals in Britain and its North American colonies drew an inspiration which blended seamlessly with the new philosophies of men such as John Locke in the 1680s, so that rebellious Virginians in 1776 could assert boldly that, “All men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

Yet as they did so, they also excluded their very many slaves from these same rights. To the west, in the Kentucky territory, and further north in the borderlands of the Ohio, white Americans were to show through the 1780s, and beyond, that the Indian nations of the continent also lacked the mysterious qualities necessary to participate in Locke’s ‘natural’ rights.

Many on the more radical side of British politics, meanwhile, had supported the American quest for freedom, and seen it as part of a larger transatlantic struggle against tyranny. In this tradition, the ousting of the Catholic king, James II, in 1688 was hailed as a victory for liberty, the ‘Glorious Revolution’ on which British freedoms were founded. Celebrating its centenary in November 1788, the speaker at a grand dinner of such radicals expressed a wish for universal freedoms, that, “England and France may no longer continue their ancient hostility against each other; but that France may regain possession of her liberties; and that two nations, so eminently distinguished... may unite together in communicating the advantages of freedom, science and the arts to the most remote regions of the earth.”

Such talk was cheap, however. While George III recovered from his madness in Britain and the United States eased slowly into existence across the Atlantic, in France the clash between the forces of freedom and privilege, rights and subjection, was played out in a dire and epochal confrontation.

Harassed by the need for money to pay off the state’s debts, the French monarchy found itself trapped between incompatible visions of reform. On one side stood institutions that claimed to be time-honoured defenders of liberty against overweening power. French nobles and judges asserted their rights to protect the nation from arbitrary rule, in the name of an unwritten constitutional tradition much like that accepted in Britain. For such men, the route to reform was through a more consistent acknowledgement of ancient rights, a more balanced approach to government – where what was to be ‘balanced’ were the interests of Crown and aristocratic elites.

To Versailles! An engraving showing an army of citizens marching on the French royal palace on 5 October 1789 to protest against King Louis XVI. (Musee Carnavalet, Paris-Dagli Orti-Art Archive)

Radical renegadesOn the other side were the advocates of thoroughgoing change. Some, like the comte de Mirabeau, were radical renegades from noble ranks; others, like Emmanuel Sieyès, had risen from humble birth (in his case through the ranks of the church). Though much of the late 1780s had seen such reformers in alliance with the defenders of the unwritten constitution, half a century of the philosophy and subversion of the Enlightenment had pushed the arguments of this grouping towards a dramatic divergence.

Enlightened thinking challenged the long-standing connections between belief in a universe created by God, the authority of religion over public life, and the hierarchical and authoritarian social and political order that such religion defended as ‘natural’. With sciences from physiology to physics on their side, thinkers set out a fresh role for the free individual in society. They wanted a new order – still a monarchy, but one both publicly accountable, and stripped of the buttresses of privilege that kept the talents of the majority from reaching the peaks of public office.

The Crown’s desperate straits had driven it to answer the calls of the massed ranks of its critics for an Estates-General – a national consultative assembly that had not met for almost two centuries. What should have been a panacea provoked a further sharp divide, as the privileged nobility and clergy were granted half the delegates, and possibly two-thirds of the votes. As the opening of the Estates in May 1789 approached, the mood turned apocalyptic.

Sieyès had written at the start of the year that trying to place noble privilege within a new constitution was “like deciding on the appropriate place in the body of a sick man for a malignant tumour... It must be neutralised”. His aristocratic opponents lamented “this general agitation of public insanity” to strip them of their ancient rights, making “the whole universe” seem “in the throes of convulsions”.

This conflict of words was already matched by one of deeds. Harsh weather and poor harvests had left French peasants impoverished and anxious. The political storm over the Estates-General provoked fears of an aristocratic plot to beat the people into submission. By the spring of 1789 tithes and dues owed to clergy and privileged landlords were being refused, and in some cases abbeys and châteaux were invaded, their stocks looted and records destroyed.

Meanwhile, urban populations, dependent on the countryside for food, and always suspicious of peasant motivations, increasingly saw such disruption as part of the aristocratic plot itself – for any trouble threatened the fragile supply-lines that brought grain to the cities. Town-dwellers formed militias, and waited anxiously for news from the men they had sent to the Estates at Versailles.

What played out over the summer months of 1789 was partly a violent confrontation – nowhere clearer than in the storming of the Bastille on 14 July – but also a strange mixture of dread and euphoria, as even many of the feared aristocrats came to be swept up in the idea of change.

On 4 August, in a bid to appease the restless peasantry, the first suggestion was made in the National Assembly (as the Estates-General had rebaptised itself in June) to end the various exactions that privileged lords could claim, by time-honoured right, from farmers’ harvests. The result a few hours later was a commitment to total civic equality, born of a “combat of generosity”, a “bountiful example of magnanimity and disinterestedness”. This spirit was expressed still more vividly later in August, in the voting “for all men and for all countries” of a Declaration of the Rights of Man.

From this euphoric peak, however, the only way was down. Within the year, those whose power was being directly challenged by the transformations of 1789 had coalesced into an overt ‘Counter-revolution’, and the links of this aristocratic grouping to the other powers of Europe fuelled a rising paranoia among revolutionaries, until a war to cleanse France’s frontiers of threat seemed the only way forward.

War was declared on Austria in April 1792, with Prussia entering the conflict shortly afterwards. An army wracked by dissent between ‘patriotic’ troops and ‘aristocratic’ officers (many of whom had already deserted to the counter-revolution) produced a string of military disasters. The conviction among Parisian radicals that royal treason was behind this led them to bring down the monarchy with armed force on 10 August 1792.

Newly-republican French armies rallied to save the country from defeat, but France moved inexorably towards the horrors of civil war and state terror, the revolutionary political class clawing at itself in furious division. Even amid such internal conflict, the spirit of free citizenship and newfound republicanism inspired continued prodigies of military effort. France went to war with Britain, Spain, the Netherlands and the Italian states from early 1793, plunging Europe into a generation of conflict.

Suffocated hopesThe true tragedy of this descent was that it suffocated all the international hopes of 1789. Americans found themselves forced to choose sides, with enmity towards either Britain or France a key component of the vicious factional politics reigning in the United States by the later 1790s.

Britain, where Thomas Paine in his Rights of Man had tried to bring the message of the American and French Revolutions home, saw assaults on freedoms such as habeas corpus and public assembly. The claims of the lower orders for a share of power were assimilated, in the words of one 1794 statute, to “a traitorous and detestable Conspiracy... for introducing the System of Anarchy and Confusion which has so fatally prevailed in France”.

Real revolt broke out in Ireland in 1798, fomented by exaggerated hopes of French intervention and exacerbated by the brutality of an establishment wedded to a view of the Catholic peasantry as little better than beasts. Thirty thousand died in months of savage repression. Napoleon Bonaparte, also in 1798, tried to take the war to Britain in the East, and the chaotic failure of his Egyptian expedition did not prevent him from ascending first to dictatorship the next year, and to an imperial throne in 1804. By then he had already, in 1803, broken a short-lived peace with Britain, and for the following decade was to pursue a relentless policy of expansion.

Napoleon Bonaparte on the Bridge at Arcole, 1796. His campaigns were to transform the map of Europe. (Bridgeman Art Library)

The unwillingness of the other powers to fully accept Napoleon’s legitimacy was one factor in this, but the emperor’s own determination to have dominance at almost any cost was itself a reason for that intransigent opposition. Together, they made for a spiral of warfare that criss-crossed Europe from Lisbon to Moscow, until the final insane Russia campaign of 1812 turned the tide.

Napoleon was driven back within French borders, abdicating in 1814 before returning the next year for a last hurrah at Waterloo. His final fate, to be held on the island of Saint Helena thousands of miles from Europe, reflects ironically on the power of the individual liberated by the events of 1789. Where the revolutionaries had hoped to create the conditions for the rise of free individuals everywhere, they gave power to one such man, someone so extraordinary he had to end his days like a character in a Greek myth, chained to a rock.

Napoleon’s legacy was to ensure that revolution would always be viewed through the lens of war. Abandoning a universalist rhetoric – and reinstating the colonial slavery his more radical predecessors had abolished in 1794 – the emperor of the French later claimed to have had a vision of a Europe of Nations, where Spaniards, Italians, Germans and Poles could live free of aristocratic tyranny.

Since he actually created an empire that stretched from Hamburg to Genoa, and client-kingdoms for his relations around its edges, there is little reason to take this claim seriously. That he thought it worth making, however, shows how central the new question of nationality would be, as the troubled generations to come wrestled yet again with the question of who was entitled to be free.

A contemporary illustration of the Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789. (Musee Carnavalet-AKG Images)

A contemporary illustration of the Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789. (Musee Carnavalet-AKG Images) 1789–1815: The world in revoltDavid Andress explains how the events of 1789 were an attempt to strip society of the inequalities of privilege, at a time when ‘freedom’ had a very confused meaningThe medieval fortress-prison of the Bastille loomed over eastern Paris. For centuries the enemies and victims of royal power had been carried there in shuttered coaches, and rumours ran of unspeakable tortures in its dungeons. On 14 July 1789 Parisians stormed the fortress, their rage against aristocratic enemies they thought ready to destroy the city to save their privilege driving some to suicidal bravery.

Men leapt over rooftops to smash drawbridge chains, others dismantled cannon and hauled them by hand over barricades. The tiny garrison yielded on the point of being overwhelmed, and at the news, royal troops elsewhere in the city packed up and marched away, their officers unwilling to try their loyalty against the triumphant people.

The storming of the Bastille was the high-water mark of a wave of insurrection that swept France in the summer of 1789. Events that created the very idea of ‘revolution’ as the modern world was to know it, as a complete overthrowing of an old order, followed a failed attempt to prop up an absolute monarchy.

That monarchy had bankrupted itself, in one of the greatest ironies of this age, paying for a war of liberation halfway around the world. When the French king Louis XVI heeded the enthusiasts for American independence and sent his troops and fleets to fight the British Empire in 1778, he thought he was dealing a death-blow to an age-old foe. In fact, he launched a process that would make Britain an even more dominant global power than it had been before the United States broke free. But he would also create, against his will, a culture of equality and rights with a disputed heritage all the way to the present day.

A battle for the regencyFrance’s ancient enemy, Britain, was facing its own crisis as 1789 dawned. King George III had fallen into raving mania, and a bitter political battle was under way for the powers of a regency. Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, after five years in office as the country’s youngest ever premier, had never shaken off the view of his opponents that his rule was an unconstitutional imposition. Placed in office in 1783 by the king’s favour, his government had faced threats of impeachment before a hard-fought 1784 election had given him a working majority. Now the opposition, led by Charles James Fox, saw the chance to eject Pitt when their royal patron, the Prince of Wales, took on the regency.

In America a transition scarcely less delicate or contested was in train. The years after independence in 1783 were a time of political and fiscal disorder. For two years the much-disputed form of a new constitution for the new nation crept towards fulfilment. ‘Federalists’ and ‘Antifederalists’ clashed vigorously, and occasionally violently, over the powers of central government, and though George Washington was unanimously chosen in January 1789 to be the first president, many still feared that the new power-structure would subject them to a tyranny as great as the British one they had escaped.

At stake in all of these countries was a tangled web of ideas about the meaning of freedom, its connection to the concept of rights, and the besetting question of whether such terms covered the privileged possessions of a few, or were the natural heritage of all. For the Anglo-American world, freedom and rights had first been seen as the historical consequence of a very particular evolution.

From the medieval days of Magna Carta and the time-honoured maxims of English Common Law, radicals in Britain and its North American colonies drew an inspiration which blended seamlessly with the new philosophies of men such as John Locke in the 1680s, so that rebellious Virginians in 1776 could assert boldly that, “All men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

Yet as they did so, they also excluded their very many slaves from these same rights. To the west, in the Kentucky territory, and further north in the borderlands of the Ohio, white Americans were to show through the 1780s, and beyond, that the Indian nations of the continent also lacked the mysterious qualities necessary to participate in Locke’s ‘natural’ rights.

Many on the more radical side of British politics, meanwhile, had supported the American quest for freedom, and seen it as part of a larger transatlantic struggle against tyranny. In this tradition, the ousting of the Catholic king, James II, in 1688 was hailed as a victory for liberty, the ‘Glorious Revolution’ on which British freedoms were founded. Celebrating its centenary in November 1788, the speaker at a grand dinner of such radicals expressed a wish for universal freedoms, that, “England and France may no longer continue their ancient hostility against each other; but that France may regain possession of her liberties; and that two nations, so eminently distinguished... may unite together in communicating the advantages of freedom, science and the arts to the most remote regions of the earth.”

Such talk was cheap, however. While George III recovered from his madness in Britain and the United States eased slowly into existence across the Atlantic, in France the clash between the forces of freedom and privilege, rights and subjection, was played out in a dire and epochal confrontation.

Harassed by the need for money to pay off the state’s debts, the French monarchy found itself trapped between incompatible visions of reform. On one side stood institutions that claimed to be time-honoured defenders of liberty against overweening power. French nobles and judges asserted their rights to protect the nation from arbitrary rule, in the name of an unwritten constitutional tradition much like that accepted in Britain. For such men, the route to reform was through a more consistent acknowledgement of ancient rights, a more balanced approach to government – where what was to be ‘balanced’ were the interests of Crown and aristocratic elites.

To Versailles! An engraving showing an army of citizens marching on the French royal palace on 5 October 1789 to protest against King Louis XVI. (Musee Carnavalet, Paris-Dagli Orti-Art Archive)

Radical renegadesOn the other side were the advocates of thoroughgoing change. Some, like the comte de Mirabeau, were radical renegades from noble ranks; others, like Emmanuel Sieyès, had risen from humble birth (in his case through the ranks of the church). Though much of the late 1780s had seen such reformers in alliance with the defenders of the unwritten constitution, half a century of the philosophy and subversion of the Enlightenment had pushed the arguments of this grouping towards a dramatic divergence.

Enlightened thinking challenged the long-standing connections between belief in a universe created by God, the authority of religion over public life, and the hierarchical and authoritarian social and political order that such religion defended as ‘natural’. With sciences from physiology to physics on their side, thinkers set out a fresh role for the free individual in society. They wanted a new order – still a monarchy, but one both publicly accountable, and stripped of the buttresses of privilege that kept the talents of the majority from reaching the peaks of public office.

The Crown’s desperate straits had driven it to answer the calls of the massed ranks of its critics for an Estates-General – a national consultative assembly that had not met for almost two centuries. What should have been a panacea provoked a further sharp divide, as the privileged nobility and clergy were granted half the delegates, and possibly two-thirds of the votes. As the opening of the Estates in May 1789 approached, the mood turned apocalyptic.

Sieyès had written at the start of the year that trying to place noble privilege within a new constitution was “like deciding on the appropriate place in the body of a sick man for a malignant tumour... It must be neutralised”. His aristocratic opponents lamented “this general agitation of public insanity” to strip them of their ancient rights, making “the whole universe” seem “in the throes of convulsions”.

This conflict of words was already matched by one of deeds. Harsh weather and poor harvests had left French peasants impoverished and anxious. The political storm over the Estates-General provoked fears of an aristocratic plot to beat the people into submission. By the spring of 1789 tithes and dues owed to clergy and privileged landlords were being refused, and in some cases abbeys and châteaux were invaded, their stocks looted and records destroyed.

Meanwhile, urban populations, dependent on the countryside for food, and always suspicious of peasant motivations, increasingly saw such disruption as part of the aristocratic plot itself – for any trouble threatened the fragile supply-lines that brought grain to the cities. Town-dwellers formed militias, and waited anxiously for news from the men they had sent to the Estates at Versailles.

What played out over the summer months of 1789 was partly a violent confrontation – nowhere clearer than in the storming of the Bastille on 14 July – but also a strange mixture of dread and euphoria, as even many of the feared aristocrats came to be swept up in the idea of change.

On 4 August, in a bid to appease the restless peasantry, the first suggestion was made in the National Assembly (as the Estates-General had rebaptised itself in June) to end the various exactions that privileged lords could claim, by time-honoured right, from farmers’ harvests. The result a few hours later was a commitment to total civic equality, born of a “combat of generosity”, a “bountiful example of magnanimity and disinterestedness”. This spirit was expressed still more vividly later in August, in the voting “for all men and for all countries” of a Declaration of the Rights of Man.

From this euphoric peak, however, the only way was down. Within the year, those whose power was being directly challenged by the transformations of 1789 had coalesced into an overt ‘Counter-revolution’, and the links of this aristocratic grouping to the other powers of Europe fuelled a rising paranoia among revolutionaries, until a war to cleanse France’s frontiers of threat seemed the only way forward.

War was declared on Austria in April 1792, with Prussia entering the conflict shortly afterwards. An army wracked by dissent between ‘patriotic’ troops and ‘aristocratic’ officers (many of whom had already deserted to the counter-revolution) produced a string of military disasters. The conviction among Parisian radicals that royal treason was behind this led them to bring down the monarchy with armed force on 10 August 1792.

Newly-republican French armies rallied to save the country from defeat, but France moved inexorably towards the horrors of civil war and state terror, the revolutionary political class clawing at itself in furious division. Even amid such internal conflict, the spirit of free citizenship and newfound republicanism inspired continued prodigies of military effort. France went to war with Britain, Spain, the Netherlands and the Italian states from early 1793, plunging Europe into a generation of conflict.

Suffocated hopesThe true tragedy of this descent was that it suffocated all the international hopes of 1789. Americans found themselves forced to choose sides, with enmity towards either Britain or France a key component of the vicious factional politics reigning in the United States by the later 1790s.

Britain, where Thomas Paine in his Rights of Man had tried to bring the message of the American and French Revolutions home, saw assaults on freedoms such as habeas corpus and public assembly. The claims of the lower orders for a share of power were assimilated, in the words of one 1794 statute, to “a traitorous and detestable Conspiracy... for introducing the System of Anarchy and Confusion which has so fatally prevailed in France”.

Real revolt broke out in Ireland in 1798, fomented by exaggerated hopes of French intervention and exacerbated by the brutality of an establishment wedded to a view of the Catholic peasantry as little better than beasts. Thirty thousand died in months of savage repression. Napoleon Bonaparte, also in 1798, tried to take the war to Britain in the East, and the chaotic failure of his Egyptian expedition did not prevent him from ascending first to dictatorship the next year, and to an imperial throne in 1804. By then he had already, in 1803, broken a short-lived peace with Britain, and for the following decade was to pursue a relentless policy of expansion.

Napoleon Bonaparte on the Bridge at Arcole, 1796. His campaigns were to transform the map of Europe. (Bridgeman Art Library)

The unwillingness of the other powers to fully accept Napoleon’s legitimacy was one factor in this, but the emperor’s own determination to have dominance at almost any cost was itself a reason for that intransigent opposition. Together, they made for a spiral of warfare that criss-crossed Europe from Lisbon to Moscow, until the final insane Russia campaign of 1812 turned the tide.

Napoleon was driven back within French borders, abdicating in 1814 before returning the next year for a last hurrah at Waterloo. His final fate, to be held on the island of Saint Helena thousands of miles from Europe, reflects ironically on the power of the individual liberated by the events of 1789. Where the revolutionaries had hoped to create the conditions for the rise of free individuals everywhere, they gave power to one such man, someone so extraordinary he had to end his days like a character in a Greek myth, chained to a rock.

Napoleon’s legacy was to ensure that revolution would always be viewed through the lens of war. Abandoning a universalist rhetoric – and reinstating the colonial slavery his more radical predecessors had abolished in 1794 – the emperor of the French later claimed to have had a vision of a Europe of Nations, where Spaniards, Italians, Germans and Poles could live free of aristocratic tyranny.

Since he actually created an empire that stretched from Hamburg to Genoa, and client-kingdoms for his relations around its edges, there is little reason to take this claim seriously. That he thought it worth making, however, shows how central the new question of nationality would be, as the troubled generations to come wrestled yet again with the question of who was entitled to be free.

Published on July 14, 2015 06:41

A rare treasure of ancient Roman frescoes comparable to Pompeii has been unearthed in France

Ancient Origins

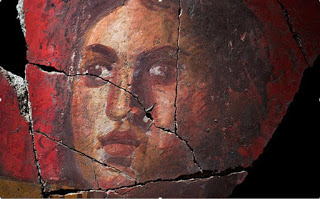

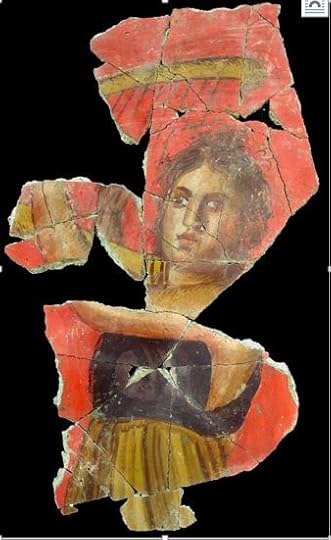

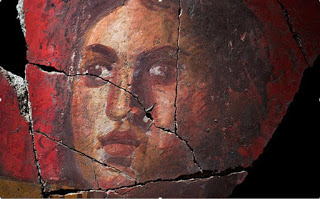

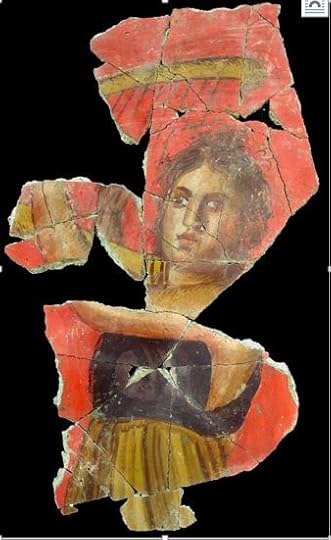

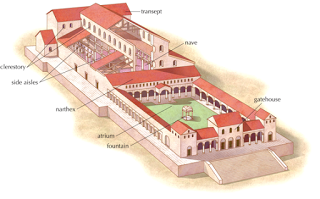

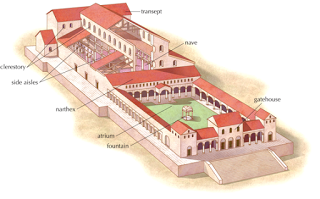

Archaeologists have excavated an ancient Roman villa in Arles, France, with fresco murals depicting a musician playing a harp, Dionysus and the entourage of Bacchus. Researchers say it is rare to find such fresco paintings from the ancient Roman era outside of Italy, and in France these frescoes are unique. Though these frescoes are broken and fragmentary, researchers will be able to piece them together.

Archaeologists have excavated an ancient Roman villa in Arles, France, with fresco murals depicting a musician playing a harp, Dionysus and the entourage of Bacchus. Researchers say it is rare to find such fresco paintings from the ancient Roman era outside of Italy, and in France these frescoes are unique. Though these frescoes are broken and fragmentary, researchers will be able to piece them together.

The most recent dig in the villa, in the state room, followed one in which a bedroom or cubiculum was excavated. Archaeologists also uncovered murals in the bedroom, but the ones in the state room were particularly fine. They were painted between 70 and 20 BC in expensive vermilion and purple pigments from Egypt, a fact that points to the wealth of the owners of the villa. The Arles Museum of Antiques says an extremely skilled Italian workshop probably produced the paintings. The depiction of the people and their clothing and the quality of the presentation are very well done, says a press release from the museum.

It is rare to find even fragments of ancient Roman frescoes outside Italy, but to find these relatively well-preserved murals in France is unique and offers a great scientific and museological opportunity, the museum said. It calls them an archaeological treasure and compares them to the spectacular frescoes of Pompeii. Some years from now, the museum says it will display these murals, made for the most elite of ancient Romans in Arles. It could take up to 10 years to restore the murals because they are in so many fragments.

The Roman god Bacchus as a Christian icon Ancient Greek Theater and the Monumental Amphitheaters in Honor of Dionysus The Houses of Pleasure in Ancient Pompeii A more complete view of the woman playing the harp (Photo by Arles Museum of Antiques)The frescoes recall those of the ancient city of Pompeii, researchers said. Much of Pompeii, including buildings, people in their final moments, and the Villa of Mysteries frescoes, was frozen in time by a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried the city in ash and pumice in 79 AD.

A more complete view of the woman playing the harp (Photo by Arles Museum of Antiques)The frescoes recall those of the ancient city of Pompeii, researchers said. Much of Pompeii, including buildings, people in their final moments, and the Villa of Mysteries frescoes, was frozen in time by a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried the city in ash and pumice in 79 AD.

A fresco from the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, Italy (Photo by MatthiasKabel/

Wikimedia Commons

)In Arles, the ruins of the Roman villa have been under excavation since 2014, but this find in the state room was unexpected.

A fresco from the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, Italy (Photo by MatthiasKabel/

Wikimedia Commons

)In Arles, the ruins of the Roman villa have been under excavation since 2014, but this find in the state room was unexpected.

The Independent reported:

The temptation of Eve and expulsion of Adam and Even from Eden, a fresco of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: The mural shows a woman plucking a harp. (Photo by the Arles Museum of Antiques)

The temptation of Eve and expulsion of Adam and Even from Eden, a fresco of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: The mural shows a woman plucking a harp. (Photo by the Arles Museum of Antiques)

Archaeologists have excavated an ancient Roman villa in Arles, France, with fresco murals depicting a musician playing a harp, Dionysus and the entourage of Bacchus. Researchers say it is rare to find such fresco paintings from the ancient Roman era outside of Italy, and in France these frescoes are unique. Though these frescoes are broken and fragmentary, researchers will be able to piece them together.

Archaeologists have excavated an ancient Roman villa in Arles, France, with fresco murals depicting a musician playing a harp, Dionysus and the entourage of Bacchus. Researchers say it is rare to find such fresco paintings from the ancient Roman era outside of Italy, and in France these frescoes are unique. Though these frescoes are broken and fragmentary, researchers will be able to piece them together.The most recent dig in the villa, in the state room, followed one in which a bedroom or cubiculum was excavated. Archaeologists also uncovered murals in the bedroom, but the ones in the state room were particularly fine. They were painted between 70 and 20 BC in expensive vermilion and purple pigments from Egypt, a fact that points to the wealth of the owners of the villa. The Arles Museum of Antiques says an extremely skilled Italian workshop probably produced the paintings. The depiction of the people and their clothing and the quality of the presentation are very well done, says a press release from the museum.

It is rare to find even fragments of ancient Roman frescoes outside Italy, but to find these relatively well-preserved murals in France is unique and offers a great scientific and museological opportunity, the museum said. It calls them an archaeological treasure and compares them to the spectacular frescoes of Pompeii. Some years from now, the museum says it will display these murals, made for the most elite of ancient Romans in Arles. It could take up to 10 years to restore the murals because they are in so many fragments.

The Roman god Bacchus as a Christian icon Ancient Greek Theater and the Monumental Amphitheaters in Honor of Dionysus The Houses of Pleasure in Ancient Pompeii

A more complete view of the woman playing the harp (Photo by Arles Museum of Antiques)The frescoes recall those of the ancient city of Pompeii, researchers said. Much of Pompeii, including buildings, people in their final moments, and the Villa of Mysteries frescoes, was frozen in time by a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried the city in ash and pumice in 79 AD.

A more complete view of the woman playing the harp (Photo by Arles Museum of Antiques)The frescoes recall those of the ancient city of Pompeii, researchers said. Much of Pompeii, including buildings, people in their final moments, and the Villa of Mysteries frescoes, was frozen in time by a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried the city in ash and pumice in 79 AD. A fresco from the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, Italy (Photo by MatthiasKabel/

Wikimedia Commons

)In Arles, the ruins of the Roman villa have been under excavation since 2014, but this find in the state room was unexpected.

A fresco from the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, Italy (Photo by MatthiasKabel/

Wikimedia Commons

)In Arles, the ruins of the Roman villa have been under excavation since 2014, but this find in the state room was unexpected.The Independent reported:

“The use of such luxurious colours underlines the wealth of the area during Roman times, experts said. The villa no doubt belonged either to rich tradesmen or the political elite of the city… the quality of the works suggested the fresco artists had been dispatched from Italy to paint them. The mural also comprises false columns imitating marble and several figures painted against a vermillion background at half or three quarters life size. After this excavation, the scientists will have over 12,000 boxes of the fresco fragments stored in black sand. These still need to be painstakingly pieced together like a giant puzzle.”Fresco painting is a style of applying pigments in solution to a newly plastered wall or other surface. Pigments are ground in water and then applied while the plaster is wet. The pigments become a part of the wall. The painter must be extremely skilled because once the pigments and plaster dry, the painting cannot be changed. Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel in frescoes, which is considered one of the greatest feats in the history of art.

The temptation of Eve and expulsion of Adam and Even from Eden, a fresco of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: The mural shows a woman plucking a harp. (Photo by the Arles Museum of Antiques)

The temptation of Eve and expulsion of Adam and Even from Eden, a fresco of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: The mural shows a woman plucking a harp. (Photo by the Arles Museum of Antiques)

Published on July 14, 2015 06:29

History Trivia - storming of the Bastille

July 14

664 Deusdedit of Canterbury, the first native-born holder of the see of Canterbury died. An Anglo-Saxon, he became archbishop in 655 and held the office until his death, probably from the plague.

1430 Joan of Arc, taken prisoner by the Burgundians in May, was handed over to Pierre Cauchon, the bishop of Beauvais.

1789 The Bastille, a fortress in Paris used to hold political prisoners, was stormed by a mob, beginning of the French Revolution.

1789 The Bastille, a fortress in Paris used to hold political prisoners, was stormed by a mob, beginning of the French Revolution.

664 Deusdedit of Canterbury, the first native-born holder of the see of Canterbury died. An Anglo-Saxon, he became archbishop in 655 and held the office until his death, probably from the plague.

1430 Joan of Arc, taken prisoner by the Burgundians in May, was handed over to Pierre Cauchon, the bishop of Beauvais.

1789 The Bastille, a fortress in Paris used to hold political prisoners, was stormed by a mob, beginning of the French Revolution.

1789 The Bastille, a fortress in Paris used to hold political prisoners, was stormed by a mob, beginning of the French Revolution.

Published on July 14, 2015 02:30

July 13, 2015

Why we say: 'Beware the Greeks bearing gifts'

The military tactic, the Trojan Horse, was portrayed in the 2004 blockbuster Troy © Mg1408 | Dreamstime.com The phrase is used to warn against possible deception by an adversary, but where does it originate?

The military tactic, the Trojan Horse, was portrayed in the 2004 blockbuster Troy © Mg1408 | Dreamstime.com The phrase is used to warn against possible deception by an adversary, but where does it originate?For ten years, the city of Troy had been under siege from the armies of Greece, after the Trojan prince Paris eloped with - the wife of Menelaus, King of Sparta. Or at least, that’s the myth.

Thousands had died in the decade-long war but the stone walls of Troy remained impenetrable. With the two sides at stalemate, the Greek warrior king Odysseus hatched a cunning plan.

A giant wooden horse was built and left at the gates of Troy and the Greek ships sailed out of sight. The Trojans, believing the war was over, saw the horse as an offering to the gods and as a gift of peace so wheeled it into the city and celebrated their victory. This is exactly what Odysseus wanted – once the Trojans had all gone to sleep – many of them blind drunk – a host of armed soldiers crept out from the belly of the horse and opened the city gates. Troy was overrun and destroyed and the ‘Trojan Horse’ became revered as one of the most successful military tactics ever.

In Virgil’s epochal version of events, Aeneid, there was one voice of reason among the Trojans who distrusted the Greeks. A priest named Laocoon pleaded against accepting the gift and bringing the horse into the city, declaring, “Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes” – roughly translated, as “I fear the Greeks, even those bearing gifts.” It was adapted over the years to the expression we have today.

But, as the story goes, Laocoon and his sons were strangled by two large serpents, sent by the gods. The Trojans saw this as a sign that the priest was wrong, and the horse was a sincere gesture of peace.

History Extra

Published on July 13, 2015 08:07

More Music Radio - Diane Turner - the Queen of Rock!

Published on July 13, 2015 07:29

History Trivia - Dean of St Paul's Cathedral perfect a way to bottle beer

July 13,

1099 The Crusaders launched their final assault on Jerusalem.

1174 William I of Scotland, a key rebel in the Revolt of 1173–1174, was captured at Alnwick by forces loyal to Henry II of England.

1568 the Dean of St Paul's Cathedral perfected a way to bottle beer.

1099 The Crusaders launched their final assault on Jerusalem.

1174 William I of Scotland, a key rebel in the Revolt of 1173–1174, was captured at Alnwick by forces loyal to Henry II of England.

1568 the Dean of St Paul's Cathedral perfected a way to bottle beer.

Published on July 13, 2015 02:00

July 12, 2015

History Trivia - Henry VIII marries Catherine Parr

July 12

100 BC Gaius Julius Caesar was born.

1472 Richard Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester and later King of England, married Anne Neville, daughter of the Earl of Warwick, in Westminster Abbey.

1543 King Henry VIII of England married his sixth and last wife, Catherine Parr, at Hampton Court Palace.

100 BC Gaius Julius Caesar was born.

1472 Richard Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester and later King of England, married Anne Neville, daughter of the Earl of Warwick, in Westminster Abbey.

1543 King Henry VIII of England married his sixth and last wife, Catherine Parr, at Hampton Court Palace.

Published on July 12, 2015 01:30

July 11, 2015

Britain’s 8 most amazing castles

Dover Castle in Kent. (Credit: Olaf Protze/LightRocket via Getty Images)

1) Dover CastleWilliam the Conqueror quickly began reinforcing his kingdom’s defences following his triumph at the battle of Hastings in 1066. Being so close to English shores, William I needed a castle at Dover to be strong enough to defend the country from possible invasion.

For Henry II, Dover Castle was also of strategic importance. In the 1180s he began to rebuild the great tower into a palace so that he could receive, entertain and impress visitors. The building work for this palatial design continued into the reigns of King John and Henry III in the 13th century.

Following the murder of Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170, Henry built a chapel in his honour on the second floor of the tower.

While the castle continued to be used by monarchs throughout the medieval and early modern period, the castle was adapted during the 18th century when England was under threat of invasion from Napoleon’s troops. Barracks for English troops were created underneath the castle in tunnels.

The stories for which Dover Castle is most famous emerged during the Second World War. The tunnels constructed during the Napoleonic years became a headquarters facility for the navy. It was here that the Dunkirk withdrawal, codenamed Operation Dynamo, was devised. Under the command of Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay, some 338,000 troops were rescued from where the Germans were closing in at Dunkirk, and taken to the secret tunnels at Dover to safety.

Visitors can today explore the tunnels for themselves and watch real film footage from the rescue operation at the castle.

To find out more about Dover Castle, click here.

Prime minister Winston Churchill viewing activity in the Channel from an observation post at Dover Castle, 28 August 1940. (Credit: Capt. Horton/ IWM via Getty Images)

2) Warwick CastleWilliam the Conqueror established Warwick castle in 1068 when he built a motte and baily fort on top of a large mound of earth. It was nearly 200 years later that the wooden frame was replaced by grand stone fortress.

During the Second Barons’ War (1264-1267), Simon de Montfort’s forces were too strong for the castle’s defences, upon which they inflicted a great deal of damage.

In 1268, William de Beauchamp succeeded as the next Earl of Warwick, beginning a dynasty that continued to hold the castle for the next 148 years. Throughout this time, the Beauchamps rebuilt Warwick Castle and they developed Guy’s and Caesar’s Tower, which still survive today.

In 1449 Richard Neville was made the Earl of Warwick. He later become known as the ‘Kingmaker’ after he helped to depose Henry VI, before he changed sides and was involved in the deposing of Edward IV in 1470.

The castle withstood a siege in 1642, during the first Civil War. A number of royalist soldiers were imprisoned in the dungeon of the castle.

The castle was bought in 1978 by The Tussauds Group, which transformed it into a tourist attraction. Visitors can now explore parts of the castle that have been converted to look as they would have done during different centuries.

To find out more about Warwick Castle, click here.

Warwick Castle. (Credit: DeAgostini/Getty Images)

3) Bodiam CastleRenowned as one of the most picturesque castles in Britain, Bodiam Castle in East Sussex was built in 1385.

The reasons behind the building of Bodiam have been debated greatly by historians: was it an imposing fortress built to defend the English from foreign invasion? Or was it an impressive home that reflected the social prestige and majesty of the inhabitants?

Owing to a lack of adequate defences, the castle was twice besieged – once by Richard III’s forces in 1484, and then again in 1643 when royalist John Tufton faced a siege orchestrated by parliamentarian Sir William Waller.

The 1643 siege left the inside of the castle in ruins until it was restored during the 19th century. The National Trust was granted ownership of the castle in 1925.

To read more about Bodiam Castle, click here.

Bodiam Castle. (Credit: Andrea Ricordi / Contributor / Getty Images)

4) Alnwick CastleRecognised by many as the set of the Harry Potter films and the 2014 Downton Abbey Christmas special, Alnwick castle has for centuries dominated the landscape of Alnwick in Northumberland.

There has been much debate around when Alnwick castle was first constructed, but there was most probably a fortress erected there by the late 11th century. The majority of the castle was constructed during the 14th and 15th centuries under the ownership of the Percy family, who still inhabit the castle today.

Positioned close to the Scottish border, the castle was for the majority of the medieval period a key stronghold for English forces safeguarding the people from a Scottish invasion. With an almighty portcullis, strong battlements, a 21-ft drop below the drawbridge and walls more than seven feet thick, the castle was successfully defended throughout its history.

The impressive octagonal towers were built during the middle of the 14th century and they are adorned with 13 stone shields that symbolise the different families who have lived in the castle or married into the Percy family.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Dukes of Northumberland repaired a great deal of the castle after it fell into disrepair. These dukes transformed the medieval remains into an impressive gothic residence.

Today, many parts of the castle are open throughout the year for the public to view.

To read more about Alnwick Castle’s history, click here.

Alnwick Castle. (Credit: © Dimitry Bobroff / Alamy)

5) Leeds CastleLeeds Castle in Kent boasts an eventful history: constructed by a Norman baron during Henry I’s reign, the castle then came under the ownership of Edward I’s wife, Eleanor of Castile, in 1278. Over the next three centuries, the castle served as a residence for the royal family.

The castle underwent some major changes during Henry VIII’s reign to turn the fortress into a palatial residence for Henry and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. An inventory from 1532 notes that there were fireplaces decorated with Spanish symbols (reflecting Catherine’s nationality) alongside Henry’s royal arms. On his journey to northern France in 1520 to meet with Francis I at the Field of Cloth of Gold, Henry and Catherine, along with 5,000 nobles, servants and entertainers, stayed at Leeds Castle for an evening before continuing their journey.

In 1618 the St Leger family, who owned the castle, were required to sell it to Sir Richard Smythe, a wealthy family member, after they were faced with financial ruin from their association with Sir Walter Raleigh’s unsuccessful expedition to find gold in El-Dorado. Soon after this, the Smythes commissioned a Jacobean house to be built after destroying all of the north end buildings of the castle.

The castle suffered further damage in the 1660s when French and Dutch prisoners of war that were imprisoned there set fire to their quarters, destroying parts of the building.

Large-scale improvements were made to Leeds Castle in the mid 18th century under the direction of the Fairfax family. It was also in this century that George III and Queen Charlotte paid the castle a visit in 1778. In preparation for the royal visit the owner, Robert Fairfax, refurbished the reception rooms at a large cost.

To find out more about Leeds Castle, click here.

Leeds Castle. (Credit: © World Pictures / Alamy)

6) Arundel CastleBuilt by Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Arundel, at the end of the 11th century, Arundel Castle’s history spans nearly 1,000 years. For more than 850 years the Dukes of Norfolk and their relatives have owned the castle.

The castle was seriously damaged in the 1640s after being besieged twice during the first Civil War. The royalists first took control of the castle, and then a parliamentarian force commanded by William Waller seized the fortress. The damage was not resolved until the 8th Duke of Norfolk began repairs in around 1718.

During the second half of the 18th and start of the 19th centuries, the 11th Duke, Charles Howard, undertook further restoration projects of the castle.

In 1846 Queen Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, visited the castle for three days. To mark her visit, the furniture for the bedroom and library were custom made, and the 13th Duke commissioned a portrait of the queen in 1843.

The castle was one of the first country houses in England to be fitted with electricity for lighting, lifts, central heating and fire fighting equipment.

To find out more about Arundel Castle, click here.

Arundel Castle. (Credit: © Derek Croucher / Alamy)

7) Hever CastleRecognised by many as the childhood home of Anne Boleyn, this motte and bailey castle in Kent was built in 1270. Over the next century the owners of the castle expanded its battlements, transforming the exterior. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Boleyn family oversaw further changes to the castle, which included creating an east and west wing.

The castle was lived in by Henry’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, and Henry’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, became the owner of the castle following the annulment of their marriage in 1540.

Later, families such as the Waldegraves, the Meade Waldos and the Humphreys owned Hever Castle. Its condition declined until William Waldorf Astor authorised the restoration of the castle and the gardens in the early 20th century. Some 800 men were employed to excavate an impressive 35-acre lake, while another 748 worked to restore the castle itself.

To find out more about Hever Castle, click here.

Hever Castle. (Credit: © nick read / Alamy)

8) Rochester CastleThe Bishop of Rochester built this castle in Kent in the 1080s, and it remains one of the best examples of Norman architecture in England.

Henry I assigned the fortress to the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1127. It was under the Archbishop’s control that the great keep was constructed – the tallest surviving building of its kind in Europe. The decorative arches, fireplaces, doors and windows have all survived the test of time, meaning today’s visitors can imagine how the keep would have looked hundreds of years ago.

One of Rochester Castle’s most famous tales is that of King John’s attempts to seize it in 1215. While rebel barons garrisoned the castle, John was able to construct a mine under the castle and use the fat from 40 pigs as an explosive under the castle’s floor. The south-eastern corner of the keep was brought down as a result. Despite this, the garrisons continued to hold the castle until they had run out of resources and had to surrender to John’s will around seven weeks later.

The castle was rebuilt and developed during the 14th century under Edward III and Richard II. However, the condition of the castle began to deplete as it ceased to be used for military purposes during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Today, the castle and the gardens are the setting for numerous festivals and music concerts.

To find out more about Rochester Castle, click here.

Rochester Castle. (Credit: © Dreamingofpixels | Dreamstime.com - Rochester Castle Photo)

History Extra

Published on July 11, 2015 06:23

Viking Longhouse Discovery Rewrites the History of Icelandic Capital City

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists conducting an excavation in the center of Reykjavik, Iceland were actually looking for a farm cottage from 1799. Instead, they discovered something much older, a Viking longhouse 20 meters (65.6 feet) in length, 5.5 meters (18 feet) wide and with one of the largest ‘long fire’ pits ever found in the country at over 5.2 meters (17 feet) long.

Archaeologists conducting an excavation in the center of Reykjavik, Iceland were actually looking for a farm cottage from 1799. Instead, they discovered something much older, a Viking longhouse 20 meters (65.6 feet) in length, 5.5 meters (18 feet) wide and with one of the largest ‘long fire’ pits ever found in the country at over 5.2 meters (17 feet) long.

The longhouse dates back to when the Vikings first settled in Iceland, between 870 and 930 AD. Archaeologists expect to obtain a more exact date following completion of the excavation. The team has discovered a number of artifacts inside the hut, including weaving implements, a silver ring and a pearl.

“This find came as a great surprise for everybody” Þorsteinn Bergsson told The Iceland Monitor. “This rewrites the history of Reykjavik.” Mr. Bergsson is the Managing Director of Minjavernd, an independent association working for the preservation of old buildings in Iceland.

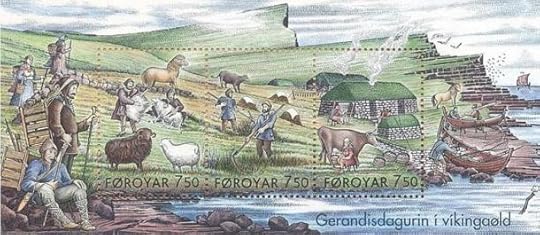

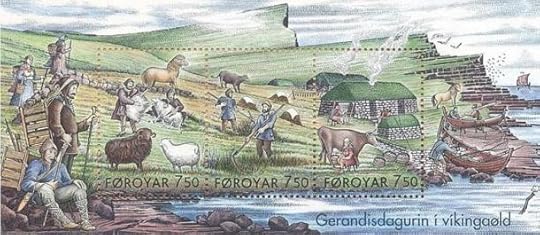

Stamps Showing Everyday Life in the Viking Age (

Wikimedia Commons

)Although it would be nice to find out who actually lived in the longhouse, the chances of ever doing this are exceedingly difficult if not impossible, according to Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir, archaeologist at the Icelandic Institute of Archaeology.

Stamps Showing Everyday Life in the Viking Age (

Wikimedia Commons

)Although it would be nice to find out who actually lived in the longhouse, the chances of ever doing this are exceedingly difficult if not impossible, according to Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir, archaeologist at the Icelandic Institute of Archaeology.

“We have no records of any building on this spot other than the cottage built in 1799” Ms Guðmundsdóttir explained. “The cottage was built on a meadow with no remnants of anything else.”

The Sagas of the Icelanders shed light on Golden AgeNewly-discovered ancient fortress reveals architectural accomplishments of VikingsNew study reveals Vikings could navigate after dark using sun-compass and mythical sunstoneThe Headless Vikings of DorsetA longhouse was a long and probably very chaotic structure, plagued by noise and dirt. This was primarily because a number of families tended to live in the same house along with their animals which were kept at one end of the structure which they used as a barn. This area would also be where the crops were stored and it would have been separated into stalls for animals and crops. The animals served a secondary purpose in that they helped to keep the longhouse warm, despite the noise. Keeping the animals in the barn also protected them from cattle thieves, as animals were also a valued form of currency.

The fire was a source of heat and light but there was no chimney and that meant the longhouse would have been very smoky. Sometimes, additional lighting was provided in the form of stone lamps with fish liver oil or whale oil as the fuel. Seating was either in the form of wooden benches along the walls or an available spot on the floor. The benches also served as beds.

Reconstruction of Viking Longhouse, Iceland (

Wikimedia Commons

)Longhouses were constructed in a number of ways but generally according to the same basic plan. The walls were commonly made from a structure of wooden poles with wattle and daub infilling. In Denmark, some longhouses had forges inside them, although more commonly the forge was housed in a separate building. The size of the longhouse depended on the wealth of the owner. Some of the largest were decorated with tapestries and rugs. The occupants may also have hung their shields on the walls. Some of the Norse sagas mention the use of tables for feasting as well. The Viking diet largely consisted of salted meat, porridge, stew, bread, cheese and honey. Viking settlers in more northerly regions hunted polar bear and seals.

Reconstruction of Viking Longhouse, Iceland (

Wikimedia Commons

)Longhouses were constructed in a number of ways but generally according to the same basic plan. The walls were commonly made from a structure of wooden poles with wattle and daub infilling. In Denmark, some longhouses had forges inside them, although more commonly the forge was housed in a separate building. The size of the longhouse depended on the wealth of the owner. Some of the largest were decorated with tapestries and rugs. The occupants may also have hung their shields on the walls. Some of the Norse sagas mention the use of tables for feasting as well. The Viking diet largely consisted of salted meat, porridge, stew, bread, cheese and honey. Viking settlers in more northerly regions hunted polar bear and seals.

In some areas of Denmark, royal longhouses were located in settlements within round earthen embankments consisting of four longhouses. Each longhouse accommodated the crew of a ship and their families. The roof was made of thatch or wooden shingles

Ingolf tager Island i besiddelse,by P. Raadsig (1850). Depicting Ingólfur Arnarson, the first permanent settler in Iceland. Legend says he threw two pillars overboard and vowed to settle wherever they landed. They landed in what is known today as Reykjavik (Cove of Smoke). (

Wikimedia Commons

)The last time a longhouse was discovered in Iceland was in 2001, at Aðalstræti. The relics found at this site represented the oldest evidence of human habitation in Reykjavik, dating back to before 871 AD. The longhouse has been preserved as the center for an exhibition about the Viking settlement of the site.

Ingolf tager Island i besiddelse,by P. Raadsig (1850). Depicting Ingólfur Arnarson, the first permanent settler in Iceland. Legend says he threw two pillars overboard and vowed to settle wherever they landed. They landed in what is known today as Reykjavik (Cove of Smoke). (

Wikimedia Commons

)The last time a longhouse was discovered in Iceland was in 2001, at Aðalstræti. The relics found at this site represented the oldest evidence of human habitation in Reykjavik, dating back to before 871 AD. The longhouse has been preserved as the center for an exhibition about the Viking settlement of the site.

Featured Image: The long fire pit in the center of the longhouse. ( Kristinn Ingvarsson/Iceland Monitor )

Archaeologists conducting an excavation in the center of Reykjavik, Iceland were actually looking for a farm cottage from 1799. Instead, they discovered something much older, a Viking longhouse 20 meters (65.6 feet) in length, 5.5 meters (18 feet) wide and with one of the largest ‘long fire’ pits ever found in the country at over 5.2 meters (17 feet) long.

Archaeologists conducting an excavation in the center of Reykjavik, Iceland were actually looking for a farm cottage from 1799. Instead, they discovered something much older, a Viking longhouse 20 meters (65.6 feet) in length, 5.5 meters (18 feet) wide and with one of the largest ‘long fire’ pits ever found in the country at over 5.2 meters (17 feet) long.The longhouse dates back to when the Vikings first settled in Iceland, between 870 and 930 AD. Archaeologists expect to obtain a more exact date following completion of the excavation. The team has discovered a number of artifacts inside the hut, including weaving implements, a silver ring and a pearl.

“This find came as a great surprise for everybody” Þorsteinn Bergsson told The Iceland Monitor. “This rewrites the history of Reykjavik.” Mr. Bergsson is the Managing Director of Minjavernd, an independent association working for the preservation of old buildings in Iceland.

Stamps Showing Everyday Life in the Viking Age (

Wikimedia Commons

)Although it would be nice to find out who actually lived in the longhouse, the chances of ever doing this are exceedingly difficult if not impossible, according to Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir, archaeologist at the Icelandic Institute of Archaeology.

Stamps Showing Everyday Life in the Viking Age (

Wikimedia Commons

)Although it would be nice to find out who actually lived in the longhouse, the chances of ever doing this are exceedingly difficult if not impossible, according to Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir, archaeologist at the Icelandic Institute of Archaeology.“We have no records of any building on this spot other than the cottage built in 1799” Ms Guðmundsdóttir explained. “The cottage was built on a meadow with no remnants of anything else.”

The Sagas of the Icelanders shed light on Golden AgeNewly-discovered ancient fortress reveals architectural accomplishments of VikingsNew study reveals Vikings could navigate after dark using sun-compass and mythical sunstoneThe Headless Vikings of DorsetA longhouse was a long and probably very chaotic structure, plagued by noise and dirt. This was primarily because a number of families tended to live in the same house along with their animals which were kept at one end of the structure which they used as a barn. This area would also be where the crops were stored and it would have been separated into stalls for animals and crops. The animals served a secondary purpose in that they helped to keep the longhouse warm, despite the noise. Keeping the animals in the barn also protected them from cattle thieves, as animals were also a valued form of currency.

The fire was a source of heat and light but there was no chimney and that meant the longhouse would have been very smoky. Sometimes, additional lighting was provided in the form of stone lamps with fish liver oil or whale oil as the fuel. Seating was either in the form of wooden benches along the walls or an available spot on the floor. The benches also served as beds.

Reconstruction of Viking Longhouse, Iceland (

Wikimedia Commons

)Longhouses were constructed in a number of ways but generally according to the same basic plan. The walls were commonly made from a structure of wooden poles with wattle and daub infilling. In Denmark, some longhouses had forges inside them, although more commonly the forge was housed in a separate building. The size of the longhouse depended on the wealth of the owner. Some of the largest were decorated with tapestries and rugs. The occupants may also have hung their shields on the walls. Some of the Norse sagas mention the use of tables for feasting as well. The Viking diet largely consisted of salted meat, porridge, stew, bread, cheese and honey. Viking settlers in more northerly regions hunted polar bear and seals.

Reconstruction of Viking Longhouse, Iceland (

Wikimedia Commons

)Longhouses were constructed in a number of ways but generally according to the same basic plan. The walls were commonly made from a structure of wooden poles with wattle and daub infilling. In Denmark, some longhouses had forges inside them, although more commonly the forge was housed in a separate building. The size of the longhouse depended on the wealth of the owner. Some of the largest were decorated with tapestries and rugs. The occupants may also have hung their shields on the walls. Some of the Norse sagas mention the use of tables for feasting as well. The Viking diet largely consisted of salted meat, porridge, stew, bread, cheese and honey. Viking settlers in more northerly regions hunted polar bear and seals.In some areas of Denmark, royal longhouses were located in settlements within round earthen embankments consisting of four longhouses. Each longhouse accommodated the crew of a ship and their families. The roof was made of thatch or wooden shingles

Ingolf tager Island i besiddelse,by P. Raadsig (1850). Depicting Ingólfur Arnarson, the first permanent settler in Iceland. Legend says he threw two pillars overboard and vowed to settle wherever they landed. They landed in what is known today as Reykjavik (Cove of Smoke). (

Wikimedia Commons

)The last time a longhouse was discovered in Iceland was in 2001, at Aðalstræti. The relics found at this site represented the oldest evidence of human habitation in Reykjavik, dating back to before 871 AD. The longhouse has been preserved as the center for an exhibition about the Viking settlement of the site.

Ingolf tager Island i besiddelse,by P. Raadsig (1850). Depicting Ingólfur Arnarson, the first permanent settler in Iceland. Legend says he threw two pillars overboard and vowed to settle wherever they landed. They landed in what is known today as Reykjavik (Cove of Smoke). (

Wikimedia Commons

)The last time a longhouse was discovered in Iceland was in 2001, at Aðalstræti. The relics found at this site represented the oldest evidence of human habitation in Reykjavik, dating back to before 871 AD. The longhouse has been preserved as the center for an exhibition about the Viking settlement of the site.Featured Image: The long fire pit in the center of the longhouse. ( Kristinn Ingvarsson/Iceland Monitor )

Published on July 11, 2015 06:07

History Trivia - Vikings sign The Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte

July 11

472 after being besieged in Rome by his own generals, Western Roman Emperor Anthemius was captured in the Old St. Peter's Basilica and put to death.

911 The Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between Charles the Simple of France and Rollo leader of the Vikings was signed. The treaty protected Charles kingdom from further invasion and created the duchy of Normandy; the Vikings became known as Normans. Also Rollo agreed to be baptized and to marry the illegitimate daughter of Charles, thus becoming the king's vassal.

1533 Pope Clement VII excommunicated England's King Henry VIII.

472 after being besieged in Rome by his own generals, Western Roman Emperor Anthemius was captured in the Old St. Peter's Basilica and put to death.

911 The Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between Charles the Simple of France and Rollo leader of the Vikings was signed. The treaty protected Charles kingdom from further invasion and created the duchy of Normandy; the Vikings became known as Normans. Also Rollo agreed to be baptized and to marry the illegitimate daughter of Charles, thus becoming the king's vassal.

1533 Pope Clement VII excommunicated England's King Henry VIII.

Published on July 11, 2015 02:00