MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 144

October 7, 2015

Who were the Celts?

History Extra

Silver coin produced by Danube Celts. © Bridgeman

Silver coin produced by Danube Celts. © Bridgeman

“The whole race… is war-mad, high-spirited and quick to battle… And so when they are stirred up they assemble in their bands for battle quite openly and without forethought.” So wrote the Greek historian Strabo about the Celts at the beginning of the first century AD. It is a generalisation that has coloured our view of the northern neighbours of the Romans and Greeks ever since.

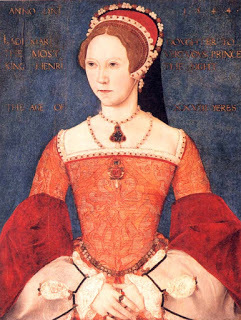

Celts first came into the consciousness of early modern historians in the 16th and 17th centuries when the works of classical writers like Strabo, Caesar and Livy were becoming widely available. These texts describe how the many barbarian tribes of western and central Europe came into conflict with the Roman and Greek worlds. The writers called these disparate peoples ‘Celts’ or ‘Gauls’ – a tradition that is at least as early as the sixth century BC, when the ethnographer Hecataeus of Miletus wrote of Celts living in the hinterland of the Greek colony of Massalia (Marseilles).

Later, in the fourth century BC, the Greek historian Ephorus of Cymae believed that barbarian Europe was occupied by only two peoples, the Scythians in the east and the Celts in the west, and Strabo adds the gloss that Ephorus considered Celtica to be so large that it included most of Iberia as far as Gades (Cadiz). These early generalisations were accepted by the later Roman authors when they came to write about their growing contacts with the peoples of central and western Europe.

In the fifth century BC, quite possibly as a result of an exponential increase in population, the tribes occupying a broad arc including the Loire valley, the Marne region, the Rhineland and Bohemia began to take on a new mobility, thousands of people moving en masse out of their homelands. These were the Celts. One of the migrating hordes thrust southwards through the Alpine passes to the Po Valley, where the disparate tribes settled down in reasonable harmony.

Another moved eastwards to the fertile country of Transdanubia (Hungary) and beyond that to the middle and lower Danube region (Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania). Once settled in their new homelands, the various Celtic tribes could indulge in raiding – a socially embedded system that enabled individuals to display and enhance their status. From the Po Valley, raiding parties swept across the Apennines deep into the Italian peninsula, confronting Roman armies and, in 390 BC, besieging Rome itself.

Later, from the middle Danube, other tribes penetrated Greece, ravaging the temple of Apollo at Delphi in 279 BC. Deflected from Greece, these migrating bands later crossed the Dardanelles and the Hellespont into Asia Minor and eventually settled in the vicinity of modern Ankara, from where they began to raid the Hellenistic cities of the Aegean coast. The raids lasted until the powerful state of Pergamon successfully defeated the marauders in a series of engagements. To commemorate these campaigns, a victory monument was erected at Pergamon depicting the defeated enemy. The famous statue of the Dying Gaul, now in Rome, is a copy of one of the figures.

A detail from the Pergamon altar, which was built in the second century BC to mark Pergamon’s victory over marauding Celtic tribes © Bridgeman

Image problemThe classical world, then, came into conflict with Celts in Italy, Greece and Asia Minor. As victors, they wrote of these strange barbarians, carefully depicting them as ‘other’ by emphasising the characteristics that distinguished them from the civilised Mediterraneans: the Celts were brave fighters, but lost heart and ran away – unlike the steadfast Romans; the Celts drank wine undiluted and got drunk – unlike the Romans, who diluted theirs and remained sober; the Celts fought naked in battle – unlike the well-armed Romans, and so on. It was a biased picture – a caricature almost – but, like any good caricature, it had within it some elements of the truth.

Much of our popular picture of the Celts comes from these very biased sources. Later, in the middle of the first century BC, when Julius Caesar campaigned in Gaul, we get from his Commentaries a rather more balanced picture of many different tribal groups, often centred on well-established towns, in various forms of alliance, with stable systems of government, able to come together to act in unison against the external threat posed by Rome. Caesar was reluctantly impressed by the belief systems of the Gauls and the centralising power of the druids.

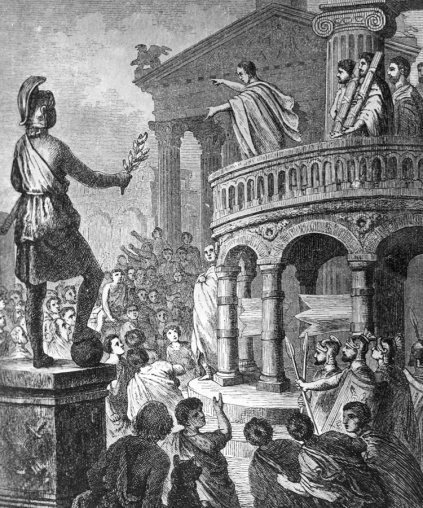

One tribe, the Aedui, sent their chief magistrate, Divitiacus, who was also a druid, to seek Roman aid against their enemies. Divitiacus addressed the Roman Senate and met Cicero, who wrote that Divitiacus “declared that he was acquainted with the system of nature that the Greeks call natural philosophy and he used to predict the future both by augury and inference”. The orator was impressed. The picture we can glean from these engagements is of a sophisticated people, quite different from the image of hairy, naked savages rushing blindly into battle.

The archaeological evidence too offers a far more reliable and unbiased picture of tribal societies at the time and also enables us to understand the earlier formative centuries. By about 1000 BC, much of western and central Europe shared a broadly similar culture and set of belief systems, reflecting a society in which warrior prowess was important.

The foundation of Massalia around 600 BC saw Mediterranean luxury goods, such as wine vessels and wine itself, being traded northwards to the chiefdoms (called Hallstatt) occupying a wide zone north of the Alps. Much of this exotic material was eventually buried in the graves of the elite, so is well known to us from the famous burials of Vix in Burgundy and Hochdorf near Stuttgart.

Men slay bulls in a detail from the Gundestrup cauldron, which dates from between c100 BC and AD 1. Though discovered in Denmark, this vessel is believed to be the handiwork of Thracians in contact with Celts © AKG Images

In return for the luxury goods, the Hallstatt chiefs in all probability offered raw materials such as gold, tin and amber, as well as slaves, which were becoming increasingly important to the Mediterranean economy.

Such a system depended on the co-operation of tribes living around the Hallstatt chiefdom zone, who acquired and supplied the raw materials and the slaves. The market for slaves encouraged raiding in these peripheral zones, creating instability that led to the breakdown of the system in the early fifth century BC. As a result, the old Hallstatt chiefdoms collapsed, while the peripheral groups occupying that arc from the Loire to Bohemia became increasingly dominant.

These societies shared cultural aspects –both in burial rites, now focusing on the warrior, and in a highly original elite art style expressed mainly in metalwork. In the archaeological terminology, this cultural manifestation is called La Tène (after a site in Switzerland) and the decorative style is often referred to as Celtic art. It was from these La Tène tribes that the migratory movements which impacted on the classical world came.

Given this archaeological background, it is reasonable to argue that the Celts, as defined by the Hellenistic and Roman writers, developed from a cultural tradition that can be traced back in west central Europe well into the second millennium BC.

When, in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, antiquarians began to take an interest in the Celts and Celtic origins, they had no archaeological evidence to inform them, but instead had to create hypotheses based partly on interpretations of the Bible and partly on the classical sources then available. The general view to emerge was that the Celts must have originated somewhere in the east and moved westwards across Europe, eventually crossing into Britain and Ireland.

The idea was taken up by a brilliant antiquarian and linguist, Edward Lhuyd, keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, who in 1707 published his great work Archaeologia Britannica, in which he set out details of his study of the native languages of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and Brittany, recognising them as belonging to the same family, which he called Celtic. Later, in letters to friends, he speculated that the languages had been introduced into Britain, Ireland and Brittany by waves of Celtic migrants coming from western central Europe. In this he was simply following the theories then current. Lhuyd’s work was to form the cornerstone of Celtic studies for the next 250 years and provide the predominant model, which later scholars were content to follow.

The ancient Roman statue of the Dying Gaul, which reinforced the traditional idea of Celts as savage, naked warriors © Bridgeman

Challenging the consensusFrom the mid-19th century, archaeological evidence began to appear in increasing quantity and was at first interpreted in terms of the accepted hypothesis, but by the 1960s archaeologists were finding it difficult to force the increasingly sophisticated data set into Lhuyd’s old linguistic model: there were things that simply did not fit. Most notably, there was no convincing archaeological evidence of migrations from central Europe into Britain and Ireland, or into Iberia – regions where the Celtic languages were known to have been spoken. It was time to take a new objective look at the evidence.

Out of this has grown a new theory: that the languages we call Celtic originated in the Atlantic zone of Europe (Iberia, western France, Britain and Ireland) as a lingua franca among the maritime communities who can be shown to have been in active contact with each other along the Atlantic seaways from the fifth millennium BC. Belief systems, artistic styles and a sophisticated knowledge of cosmology were shared along this Atlantic facade, implying that people could communicate with one another in a common language.

But if the Celtic language developed in this zone (where, in some areas, it is still spoken), then how and when did it spread eastwards into central Europe? The simplest hypothesis consistent with the archaeological evidence is that the advance took place in the second millennium with the spread of the Maritime Bell Beaker phenomenon – a time of complex movements of people, beliefs and knowledge associated with the rapid development of copper and bronze metallurgy and the exploitation of a wide range of raw materials.

By the end of the second millennium, the Beaker phenomenon embraced the whole of western and central Europe and provided the basis from which subsequent Bronze Age cultures, including those of the early Hallstatt culture, emerged. The new hypothesis neatly explains how the Celtic language may have spread and why the earliest identified Celtic inscriptions, dating to the seventh century BC, are to be found in south-western Iberia. If we accept that speakers of the Celtic language can be called Celts then, by this hypothesis, the Celts originated in Atlantic Europe long before the Greeks and Romans first encountered them in the mid-first millennium BC.

Whether the new hypothesis will stand the tests of time remains to be seen, but powerful new techniques of scientific analysis are being developed to create entirely new data sets to put alongside the archaeological and linguistic evidence. The most promising of these, the study of ancient DNA derived from human bone, will enable us to chart the movements of populations and to see if the ancestors of the Celts really did come from the west.

In 1963, despairing at the fragmented nature of Celtic studies, JRR Tolkein wrote: “Celtic of any sort is… a magic bag into which anything may be put, and out of which anything may come… Anything is possible in the fabulous Celtic twilight, which is not so much a twilight of the gods as of the reason.” He would, I think, be reassured that Celtic studies are now in vigorous good health and are at last emerging from the dimly lit realms.

Were the Britons Celtic?The inhabitants of the British Isles spoke the same language as their continental cousins. But did that make them Celts?

A 19th-century illustration shows early Britons, who were known as Prettanike, possibly meaning ‘painted ones’ © Bridgeman

The word Celtic was loosely used by the classical writers and has continued to be loosely used in more recent times to such a degree that some commentators question whether it has any value at all. Julius Caesar, however, very specifically said that the region between the rivers Garonne and Seine was known to its inhabitants as Celtica and this is supported by a late fourth-century BC writer, Pytheas, who refers to the projecting mass of the Armorican peninsula as Keltike. But no ancient writer refers to the Britons as Celts.

The poem Ora Maritima, which makes use of sources going back to the sixth century, calls Britain “the island of the Albiones”, adding that Ireland was inhabited by the Hierni, but the more widely used name was Prettanike or Pretannia whence came the name Britannia, familiar to the Romans. Prettanike may come from the word ‘painted ones’, referring to body decorations of the natives. If so, it may not be an ethnonym (the name people called themselves), but a description of the islanders reported to Pytheas by the neighbouring inhabitants of Gaul.

So can we call the Britons and Irish Celtic? That they were indigenous people and not immigrants is now broadly agreed, but they were bound to continental Europe by networks of connectivity across the English Channel and southern North Sea and along the Atlantic seaways, and through these connections they shared aspects of their culture with their continental neighbours. The most dramatic is ‘Celtic art’, which developed in western central Europe and was being introduced into Britain and Ireland by the fourth century BC to be copied and developed by local craftsmen. The motifs of Celtic art were redolent with meaning and reflected belief systems that the Britons must now have held in common with their continental neighbours.

Part of the Celtic ‘Battersea shield’, which was found in the Thames in 1857 © Bridgeman

More telling is the fact that the Celtic language was used in Britain and Ireland as well as across much of the continent – and there is good reason to suggest that the language first developed in the Atlantic zone. If so, then the Irish and the Britons, as early Celtic speakers, have a strong claim to be classified as Celts.

That said, while the tribes in regular contact with the continent will have recognised their similarities with their continental neighbours, they will also have been conscious of their differences. They will have seen themselves as first and foremost a member of their tribe, but they will also have recognised an affinity with those across the Channel. Whether they regarded their common language and traditions as part of a broader Celtic heritage, we will never know.

Barry Cunliffe is emeritus professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford. He is the author of Britain Begins (OUP, 2013).

Alice Roberts and Neil Oliver go in search of the Celts in the series The Celts: Blood, Iron, and Sacrifice, due to air on BBC Two tonight. Click here to find out more.

Meanwhile the British Museum’s Celts: Art and Identity exhibition runs until 31 January 2016. Find out more at britishmuseum.org

You can also listen to our Celts special podcast here.

Silver coin produced by Danube Celts. © Bridgeman

Silver coin produced by Danube Celts. © Bridgeman “The whole race… is war-mad, high-spirited and quick to battle… And so when they are stirred up they assemble in their bands for battle quite openly and without forethought.” So wrote the Greek historian Strabo about the Celts at the beginning of the first century AD. It is a generalisation that has coloured our view of the northern neighbours of the Romans and Greeks ever since.

Celts first came into the consciousness of early modern historians in the 16th and 17th centuries when the works of classical writers like Strabo, Caesar and Livy were becoming widely available. These texts describe how the many barbarian tribes of western and central Europe came into conflict with the Roman and Greek worlds. The writers called these disparate peoples ‘Celts’ or ‘Gauls’ – a tradition that is at least as early as the sixth century BC, when the ethnographer Hecataeus of Miletus wrote of Celts living in the hinterland of the Greek colony of Massalia (Marseilles).

Later, in the fourth century BC, the Greek historian Ephorus of Cymae believed that barbarian Europe was occupied by only two peoples, the Scythians in the east and the Celts in the west, and Strabo adds the gloss that Ephorus considered Celtica to be so large that it included most of Iberia as far as Gades (Cadiz). These early generalisations were accepted by the later Roman authors when they came to write about their growing contacts with the peoples of central and western Europe.

In the fifth century BC, quite possibly as a result of an exponential increase in population, the tribes occupying a broad arc including the Loire valley, the Marne region, the Rhineland and Bohemia began to take on a new mobility, thousands of people moving en masse out of their homelands. These were the Celts. One of the migrating hordes thrust southwards through the Alpine passes to the Po Valley, where the disparate tribes settled down in reasonable harmony.

Another moved eastwards to the fertile country of Transdanubia (Hungary) and beyond that to the middle and lower Danube region (Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania). Once settled in their new homelands, the various Celtic tribes could indulge in raiding – a socially embedded system that enabled individuals to display and enhance their status. From the Po Valley, raiding parties swept across the Apennines deep into the Italian peninsula, confronting Roman armies and, in 390 BC, besieging Rome itself.

Later, from the middle Danube, other tribes penetrated Greece, ravaging the temple of Apollo at Delphi in 279 BC. Deflected from Greece, these migrating bands later crossed the Dardanelles and the Hellespont into Asia Minor and eventually settled in the vicinity of modern Ankara, from where they began to raid the Hellenistic cities of the Aegean coast. The raids lasted until the powerful state of Pergamon successfully defeated the marauders in a series of engagements. To commemorate these campaigns, a victory monument was erected at Pergamon depicting the defeated enemy. The famous statue of the Dying Gaul, now in Rome, is a copy of one of the figures.

A detail from the Pergamon altar, which was built in the second century BC to mark Pergamon’s victory over marauding Celtic tribes © Bridgeman

Image problemThe classical world, then, came into conflict with Celts in Italy, Greece and Asia Minor. As victors, they wrote of these strange barbarians, carefully depicting them as ‘other’ by emphasising the characteristics that distinguished them from the civilised Mediterraneans: the Celts were brave fighters, but lost heart and ran away – unlike the steadfast Romans; the Celts drank wine undiluted and got drunk – unlike the Romans, who diluted theirs and remained sober; the Celts fought naked in battle – unlike the well-armed Romans, and so on. It was a biased picture – a caricature almost – but, like any good caricature, it had within it some elements of the truth.

Much of our popular picture of the Celts comes from these very biased sources. Later, in the middle of the first century BC, when Julius Caesar campaigned in Gaul, we get from his Commentaries a rather more balanced picture of many different tribal groups, often centred on well-established towns, in various forms of alliance, with stable systems of government, able to come together to act in unison against the external threat posed by Rome. Caesar was reluctantly impressed by the belief systems of the Gauls and the centralising power of the druids.

One tribe, the Aedui, sent their chief magistrate, Divitiacus, who was also a druid, to seek Roman aid against their enemies. Divitiacus addressed the Roman Senate and met Cicero, who wrote that Divitiacus “declared that he was acquainted with the system of nature that the Greeks call natural philosophy and he used to predict the future both by augury and inference”. The orator was impressed. The picture we can glean from these engagements is of a sophisticated people, quite different from the image of hairy, naked savages rushing blindly into battle.

The archaeological evidence too offers a far more reliable and unbiased picture of tribal societies at the time and also enables us to understand the earlier formative centuries. By about 1000 BC, much of western and central Europe shared a broadly similar culture and set of belief systems, reflecting a society in which warrior prowess was important.

The foundation of Massalia around 600 BC saw Mediterranean luxury goods, such as wine vessels and wine itself, being traded northwards to the chiefdoms (called Hallstatt) occupying a wide zone north of the Alps. Much of this exotic material was eventually buried in the graves of the elite, so is well known to us from the famous burials of Vix in Burgundy and Hochdorf near Stuttgart.

Men slay bulls in a detail from the Gundestrup cauldron, which dates from between c100 BC and AD 1. Though discovered in Denmark, this vessel is believed to be the handiwork of Thracians in contact with Celts © AKG Images

In return for the luxury goods, the Hallstatt chiefs in all probability offered raw materials such as gold, tin and amber, as well as slaves, which were becoming increasingly important to the Mediterranean economy.

Such a system depended on the co-operation of tribes living around the Hallstatt chiefdom zone, who acquired and supplied the raw materials and the slaves. The market for slaves encouraged raiding in these peripheral zones, creating instability that led to the breakdown of the system in the early fifth century BC. As a result, the old Hallstatt chiefdoms collapsed, while the peripheral groups occupying that arc from the Loire to Bohemia became increasingly dominant.

These societies shared cultural aspects –both in burial rites, now focusing on the warrior, and in a highly original elite art style expressed mainly in metalwork. In the archaeological terminology, this cultural manifestation is called La Tène (after a site in Switzerland) and the decorative style is often referred to as Celtic art. It was from these La Tène tribes that the migratory movements which impacted on the classical world came.

Given this archaeological background, it is reasonable to argue that the Celts, as defined by the Hellenistic and Roman writers, developed from a cultural tradition that can be traced back in west central Europe well into the second millennium BC.

When, in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, antiquarians began to take an interest in the Celts and Celtic origins, they had no archaeological evidence to inform them, but instead had to create hypotheses based partly on interpretations of the Bible and partly on the classical sources then available. The general view to emerge was that the Celts must have originated somewhere in the east and moved westwards across Europe, eventually crossing into Britain and Ireland.

The idea was taken up by a brilliant antiquarian and linguist, Edward Lhuyd, keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, who in 1707 published his great work Archaeologia Britannica, in which he set out details of his study of the native languages of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and Brittany, recognising them as belonging to the same family, which he called Celtic. Later, in letters to friends, he speculated that the languages had been introduced into Britain, Ireland and Brittany by waves of Celtic migrants coming from western central Europe. In this he was simply following the theories then current. Lhuyd’s work was to form the cornerstone of Celtic studies for the next 250 years and provide the predominant model, which later scholars were content to follow.

The ancient Roman statue of the Dying Gaul, which reinforced the traditional idea of Celts as savage, naked warriors © Bridgeman

Challenging the consensusFrom the mid-19th century, archaeological evidence began to appear in increasing quantity and was at first interpreted in terms of the accepted hypothesis, but by the 1960s archaeologists were finding it difficult to force the increasingly sophisticated data set into Lhuyd’s old linguistic model: there were things that simply did not fit. Most notably, there was no convincing archaeological evidence of migrations from central Europe into Britain and Ireland, or into Iberia – regions where the Celtic languages were known to have been spoken. It was time to take a new objective look at the evidence.

Out of this has grown a new theory: that the languages we call Celtic originated in the Atlantic zone of Europe (Iberia, western France, Britain and Ireland) as a lingua franca among the maritime communities who can be shown to have been in active contact with each other along the Atlantic seaways from the fifth millennium BC. Belief systems, artistic styles and a sophisticated knowledge of cosmology were shared along this Atlantic facade, implying that people could communicate with one another in a common language.

But if the Celtic language developed in this zone (where, in some areas, it is still spoken), then how and when did it spread eastwards into central Europe? The simplest hypothesis consistent with the archaeological evidence is that the advance took place in the second millennium with the spread of the Maritime Bell Beaker phenomenon – a time of complex movements of people, beliefs and knowledge associated with the rapid development of copper and bronze metallurgy and the exploitation of a wide range of raw materials.

By the end of the second millennium, the Beaker phenomenon embraced the whole of western and central Europe and provided the basis from which subsequent Bronze Age cultures, including those of the early Hallstatt culture, emerged. The new hypothesis neatly explains how the Celtic language may have spread and why the earliest identified Celtic inscriptions, dating to the seventh century BC, are to be found in south-western Iberia. If we accept that speakers of the Celtic language can be called Celts then, by this hypothesis, the Celts originated in Atlantic Europe long before the Greeks and Romans first encountered them in the mid-first millennium BC.

Whether the new hypothesis will stand the tests of time remains to be seen, but powerful new techniques of scientific analysis are being developed to create entirely new data sets to put alongside the archaeological and linguistic evidence. The most promising of these, the study of ancient DNA derived from human bone, will enable us to chart the movements of populations and to see if the ancestors of the Celts really did come from the west.

In 1963, despairing at the fragmented nature of Celtic studies, JRR Tolkein wrote: “Celtic of any sort is… a magic bag into which anything may be put, and out of which anything may come… Anything is possible in the fabulous Celtic twilight, which is not so much a twilight of the gods as of the reason.” He would, I think, be reassured that Celtic studies are now in vigorous good health and are at last emerging from the dimly lit realms.

Were the Britons Celtic?The inhabitants of the British Isles spoke the same language as their continental cousins. But did that make them Celts?

A 19th-century illustration shows early Britons, who were known as Prettanike, possibly meaning ‘painted ones’ © Bridgeman

The word Celtic was loosely used by the classical writers and has continued to be loosely used in more recent times to such a degree that some commentators question whether it has any value at all. Julius Caesar, however, very specifically said that the region between the rivers Garonne and Seine was known to its inhabitants as Celtica and this is supported by a late fourth-century BC writer, Pytheas, who refers to the projecting mass of the Armorican peninsula as Keltike. But no ancient writer refers to the Britons as Celts.

The poem Ora Maritima, which makes use of sources going back to the sixth century, calls Britain “the island of the Albiones”, adding that Ireland was inhabited by the Hierni, but the more widely used name was Prettanike or Pretannia whence came the name Britannia, familiar to the Romans. Prettanike may come from the word ‘painted ones’, referring to body decorations of the natives. If so, it may not be an ethnonym (the name people called themselves), but a description of the islanders reported to Pytheas by the neighbouring inhabitants of Gaul.

So can we call the Britons and Irish Celtic? That they were indigenous people and not immigrants is now broadly agreed, but they were bound to continental Europe by networks of connectivity across the English Channel and southern North Sea and along the Atlantic seaways, and through these connections they shared aspects of their culture with their continental neighbours. The most dramatic is ‘Celtic art’, which developed in western central Europe and was being introduced into Britain and Ireland by the fourth century BC to be copied and developed by local craftsmen. The motifs of Celtic art were redolent with meaning and reflected belief systems that the Britons must now have held in common with their continental neighbours.

Part of the Celtic ‘Battersea shield’, which was found in the Thames in 1857 © Bridgeman

More telling is the fact that the Celtic language was used in Britain and Ireland as well as across much of the continent – and there is good reason to suggest that the language first developed in the Atlantic zone. If so, then the Irish and the Britons, as early Celtic speakers, have a strong claim to be classified as Celts.

That said, while the tribes in regular contact with the continent will have recognised their similarities with their continental neighbours, they will also have been conscious of their differences. They will have seen themselves as first and foremost a member of their tribe, but they will also have recognised an affinity with those across the Channel. Whether they regarded their common language and traditions as part of a broader Celtic heritage, we will never know.

Barry Cunliffe is emeritus professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford. He is the author of Britain Begins (OUP, 2013).

Alice Roberts and Neil Oliver go in search of the Celts in the series The Celts: Blood, Iron, and Sacrifice, due to air on BBC Two tonight. Click here to find out more.

Meanwhile the British Museum’s Celts: Art and Identity exhibition runs until 31 January 2016. Find out more at britishmuseum.org

You can also listen to our Celts special podcast here.

Published on October 07, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Lepanto - Ottoman navy routed

October 7

336 Pope Saint Mark (Marcus) died of natural causes, ending his reign as Catholic Pope which lasted under a year. He is credited with the foundation of the Basilica of San Marco in Rome, and a cemetery church over the Catacomb of Balbina, just outside the city.

1571 The Holy League of the Papal States, Spain and Venice routed the Ottoman navy at the Battle of Lepanto. This was the defining battle of the crusades between the Christian nations on the Mediterranean and the Muslim Turks where the outnumbered Christians were victorious.

336 Pope Saint Mark (Marcus) died of natural causes, ending his reign as Catholic Pope which lasted under a year. He is credited with the foundation of the Basilica of San Marco in Rome, and a cemetery church over the Catacomb of Balbina, just outside the city.

1571 The Holy League of the Papal States, Spain and Venice routed the Ottoman navy at the Battle of Lepanto. This was the defining battle of the crusades between the Christian nations on the Mediterranean and the Muslim Turks where the outnumbered Christians were victorious.

Published on October 07, 2015 00:30

October 6, 2015

Dig uncovers gladiatorial ring in an ancient Cilician city of Turkey

Ancient Origins

Dig uncovers gladiatorial ring in an ancient Cilician city of TurkeyThe long reach of the Roman Empire was felt in southern Turkey, where in the town of Anazarbus the Romans erected a triumphal arch after defeating a Parthian force in the first century BC and where gladiators fought wild beasts in a well-preserved stadium.

Dig uncovers gladiatorial ring in an ancient Cilician city of TurkeyThe long reach of the Roman Empire was felt in southern Turkey, where in the town of Anazarbus the Romans erected a triumphal arch after defeating a Parthian force in the first century BC and where gladiators fought wild beasts in a well-preserved stadium.

Excavations at the ancient city have been under way since mid-2014. The most recent discovery is the arena or gladiators’ ring. The archaeologists, with a $335,000 grant from Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, also intend to excavate a nearby amphitheater in the 4-million-square-meter (988-acre) city.

Underneath the amphitheater are arches and chambers where wild animals, including lions and tigers, waited to be brought into the stadium to fight the gladiators, according to Çukurova University archaeologist Fatih Gülşen, who is in charge of the project. The stadium had tall granite watchtowers where referees oversaw the combats.

A mosaic of fish in the ancient city (Photo by Klaus-Peter Simon/Wikimedia Commons)

A mosaic of fish in the ancient city (Photo by Klaus-Peter Simon/Wikimedia Commons)

Anazarbus or Anavarza was one of the most important Roman military outposts in the East. There is evidence that the city was at various times home to Sassanian, Greek, Ottoman, Byzantine and Armenian peoples. The foundation of a fortress at the site may date back to the seventh century BC and the Assyrians. The Romans took it over from the Cilicians. It declined during the later Byzantine period but became the capital of the Armenian kingdom in the 12th century AD. The Armenians abandoned the city in 1375 after the Marmalukes defeated them. The city was never reoccupied.

Anazarbus is on the outskirts of present-day Dilekkaya in the Kozan district of Adana Province. The ruins are becoming a tourist attraction.

The ancient fortress at Anazarbus or Anavarza, which may date back to Assyrians building in the seventh century BC. (Photo by Sarah Murray/Wikimedia Commons)Earlier this year, the triumphal arch of Anazarbus, which is 22.5 meters (74 feet) wide, 10.5 meters (34.5 feet) high and 5.6 meters (18.4 feet) thick, was under renovations to restore it as a tourist attraction.

The ancient fortress at Anazarbus or Anavarza, which may date back to Assyrians building in the seventh century BC. (Photo by Sarah Murray/Wikimedia Commons)Earlier this year, the triumphal arch of Anazarbus, which is 22.5 meters (74 feet) wide, 10.5 meters (34.5 feet) high and 5.6 meters (18.4 feet) thick, was under renovations to restore it as a tourist attraction.

Gülşen said in May 2015 that the gate had three arches, but only two are still standing, according to Archaeology News Network. However, restoration experts used laser scanners to determine which blocks go where in order to replace them. The arch was made with granite, marble and smooth lime. Gülşen called it an artistic wonder.

The city was home to some famous ancients, including the poet Opanius and Pedanius Dioscorides, who has been called the founder of pharmacology – he concocted medicines from 50 local plants.

Featured image: The triumphal arch and city gates of the ancient Cilician city of Anazarbus in southern Turkey; archaeologists are excavating and restoring the city. (Photo by Mustafa Tor/Wikimedia Commons)

By Mark Miller

Dig uncovers gladiatorial ring in an ancient Cilician city of TurkeyThe long reach of the Roman Empire was felt in southern Turkey, where in the town of Anazarbus the Romans erected a triumphal arch after defeating a Parthian force in the first century BC and where gladiators fought wild beasts in a well-preserved stadium.

Dig uncovers gladiatorial ring in an ancient Cilician city of TurkeyThe long reach of the Roman Empire was felt in southern Turkey, where in the town of Anazarbus the Romans erected a triumphal arch after defeating a Parthian force in the first century BC and where gladiators fought wild beasts in a well-preserved stadium.Excavations at the ancient city have been under way since mid-2014. The most recent discovery is the arena or gladiators’ ring. The archaeologists, with a $335,000 grant from Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, also intend to excavate a nearby amphitheater in the 4-million-square-meter (988-acre) city.

Underneath the amphitheater are arches and chambers where wild animals, including lions and tigers, waited to be brought into the stadium to fight the gladiators, according to Çukurova University archaeologist Fatih Gülşen, who is in charge of the project. The stadium had tall granite watchtowers where referees oversaw the combats.

A mosaic of fish in the ancient city (Photo by Klaus-Peter Simon/Wikimedia Commons)

A mosaic of fish in the ancient city (Photo by Klaus-Peter Simon/Wikimedia Commons)“We’ll be able to see how such structures operated beyond Rome, in distant states like Anatolia. We’ll see how they were planned, which wild animals were used, which tools and equipment were required,” Gülşen said, according to an article in BGN News.The area was inhabited long before the Romans took over, but the ruins being excavated now were built on the order of Emperor Augustus beginning in 19 BC. Gülşen said the name Anazarbus means “unvanquished” in Persian.

Anazarbus or Anavarza was one of the most important Roman military outposts in the East. There is evidence that the city was at various times home to Sassanian, Greek, Ottoman, Byzantine and Armenian peoples. The foundation of a fortress at the site may date back to the seventh century BC and the Assyrians. The Romans took it over from the Cilicians. It declined during the later Byzantine period but became the capital of the Armenian kingdom in the 12th century AD. The Armenians abandoned the city in 1375 after the Marmalukes defeated them. The city was never reoccupied.

Anazarbus is on the outskirts of present-day Dilekkaya in the Kozan district of Adana Province. The ruins are becoming a tourist attraction.

The ancient fortress at Anazarbus or Anavarza, which may date back to Assyrians building in the seventh century BC. (Photo by Sarah Murray/Wikimedia Commons)Earlier this year, the triumphal arch of Anazarbus, which is 22.5 meters (74 feet) wide, 10.5 meters (34.5 feet) high and 5.6 meters (18.4 feet) thick, was under renovations to restore it as a tourist attraction.

The ancient fortress at Anazarbus or Anavarza, which may date back to Assyrians building in the seventh century BC. (Photo by Sarah Murray/Wikimedia Commons)Earlier this year, the triumphal arch of Anazarbus, which is 22.5 meters (74 feet) wide, 10.5 meters (34.5 feet) high and 5.6 meters (18.4 feet) thick, was under renovations to restore it as a tourist attraction.Gülşen said in May 2015 that the gate had three arches, but only two are still standing, according to Archaeology News Network. However, restoration experts used laser scanners to determine which blocks go where in order to replace them. The arch was made with granite, marble and smooth lime. Gülşen called it an artistic wonder.

“It is a huge and unique structure decorated with Corinthian heads, columns, pilasters [rectangular columns] and niches,” he said. “Because of these features, it is the only one in the region that we call Çukurova today, and one of the few monumental city gates within the borders of Turkey.”Daily Sabah reports the city had the only known two-lane road in the ancient world. The road was 2,700 meters (8,858 feet) long and was lined with monumental columns, which archaeologists are restoring.

The city was home to some famous ancients, including the poet Opanius and Pedanius Dioscorides, who has been called the founder of pharmacology – he concocted medicines from 50 local plants.

Featured image: The triumphal arch and city gates of the ancient Cilician city of Anazarbus in southern Turkey; archaeologists are excavating and restoring the city. (Photo by Mustafa Tor/Wikimedia Commons)

By Mark Miller

Published on October 06, 2015 03:30

History Trivia - Battle of Arausio - Roman army defeated

October 6

105 BC Battle of Arausio: The Cimbri (tribe from Northern Europe) inflicted the heaviest defeat on the Roman army of Gnaeus Mallius Maximus.

891 Formosus was elected Pope. During his pontificate, he attempted to liberate Rome from the Spoletan Holy Roman co-emperors Guy and his son Lambert, crowned Arnulf of the East Franks emperor and requested he invade Italy which left the German states in discord.

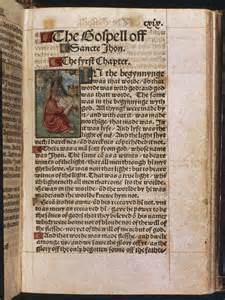

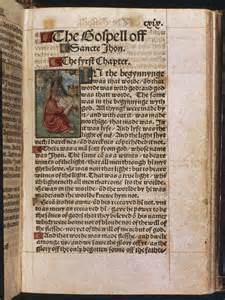

1536 William Tyndale, the English translator of the New Testament, is strangled and burned at the stake for heresy at Vilvorde, France.

105 BC Battle of Arausio: The Cimbri (tribe from Northern Europe) inflicted the heaviest defeat on the Roman army of Gnaeus Mallius Maximus.

891 Formosus was elected Pope. During his pontificate, he attempted to liberate Rome from the Spoletan Holy Roman co-emperors Guy and his son Lambert, crowned Arnulf of the East Franks emperor and requested he invade Italy which left the German states in discord.

1536 William Tyndale, the English translator of the New Testament, is strangled and burned at the stake for heresy at Vilvorde, France.

Published on October 06, 2015 00:30

October 5, 2015

New Scans of Ancient Pompeii Victims Reveal Great Teeth and Good Health

Ancient Origins

CT scanners are being used on the plaster casts of the Mount Vesuvius victims from Pompeii. Preliminary results show that, in general, they had great teeth and were in remarkably good health before the volcanic eruption. This new discovery goes against the commonly held belief that Romans were often hedonists that enjoyed consuming in excess whenever possible.

CT scanners are being used on the plaster casts of the Mount Vesuvius victims from Pompeii. Preliminary results show that, in general, they had great teeth and were in remarkably good health before the volcanic eruption. This new discovery goes against the commonly held belief that Romans were often hedonists that enjoyed consuming in excess whenever possible.

Especially surprising for the scientists is that the ancient Pompeiians had great dental records, despite the poor dental care available in 79 AD. “They ate better than we did and have really good teeth.” Elisa Vanacore, a dental expert, said in a press release. The Pompeiians ate a diet high in fruits and vegetables and low in sugars. Apart from a healthy diet, “The initial results also show the high levels of fluorine that are present in the air and water here, near the volcano,” Vanacore continued. Fluorine may have been a beneficial or a detrimental factor to the dental and bone health of the Pompeiians depending on the quantity they consumed.

Scan of one of the plaster casts from Pompeii revealing a healthy set of teeth. (Credit: Napoli/Giino/Ropi/ZUMA Press/Newscom)30 of the 86 Pompeiian plaster casts have passed through the scanning process so far. The results are providing more details on the lives of the individuals found from the site. “It will reveal much about the victims: their age, sex, what they ate, what diseases they had and what class of society they belonged to. This will be a great step forward in our knowledge of antiquity.” Massimo Osanna, the archaeological superintendent of Pompeii, said.

Scan of one of the plaster casts from Pompeii revealing a healthy set of teeth. (Credit: Napoli/Giino/Ropi/ZUMA Press/Newscom)30 of the 86 Pompeiian plaster casts have passed through the scanning process so far. The results are providing more details on the lives of the individuals found from the site. “It will reveal much about the victims: their age, sex, what they ate, what diseases they had and what class of society they belonged to. This will be a great step forward in our knowledge of antiquity.” Massimo Osanna, the archaeological superintendent of Pompeii, said.

For Stefania Giudice, a conservator from Naples national archaeological Museum, the Pompeiians are also taking on a more human importance as they continue to be studied: 'It can be very moving handling these remains. Even though it happened 2,000 years ago, it could be a boy, a mother or a family. It's human archaeology, not just archaeology.' These connections enhance the significance of the study for those involved as well.

The plaster casts of Pompeii victims were placed through CT scans to reveal what was underneath. Source: BigStockPhotoThe team is a multidisciplinary one that is composed of archaeologists, computer engineers, radiologists, and orthodontists. In conjunction with the CT scanners, they have also used a contrast dye that mimics the appearance of muscles and skin to accentuate the features of the victims. Together, the technologies are providing the images of the remains in vivid details.

The plaster casts of Pompeii victims were placed through CT scans to reveal what was underneath. Source: BigStockPhotoThe team is a multidisciplinary one that is composed of archaeologists, computer engineers, radiologists, and orthodontists. In conjunction with the CT scanners, they have also used a contrast dye that mimics the appearance of muscles and skin to accentuate the features of the victims. Together, the technologies are providing the images of the remains in vivid details.

Decaying and Looted Pompeii Gets a Big Infusion of Care from the Italian GovernmentGiraffe and Sea Urchin on the Menu for People of PompeiiThe Houses of Pleasure in Ancient PompeiiPompeii of the East: 4,000 year-old victims of Chinese earthquake captured in their final momentsWhen the Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli first thought of plaster casting the remains in 1866, his goals were mostly to move and preserve the fragile bodies. Unfortunately, this delayed the process of analyzing the organic matter, until now.

Tomography is the process of creating a 2D image or 'slice' of a 3D object that allows doctors to search in detail for problems in their patients. It is in common use in hospitals and is becoming more familiar in archaeology as well.

One of the Pompeii victim’s scan results, Italy. Credit: The Archaeological Site of Pompeii.In this study the scientists are using a 16-layer CAT technology machine. “One of the problems we encountered was the density of chalk used for the cast technique. It is a density similar to bones, that's why we had to use the 16-layer CAT technology." Massimo Osanna explained.

One of the Pompeii victim’s scan results, Italy. Credit: The Archaeological Site of Pompeii.In this study the scientists are using a 16-layer CAT technology machine. “One of the problems we encountered was the density of chalk used for the cast technique. It is a density similar to bones, that's why we had to use the 16-layer CAT technology." Massimo Osanna explained.

Another difficulty the team has had to contend with regarding the CT scanners is that they only allow individuals up to a 70 cm (27.6 inches) diameter to enter the machine. Thus the more robust Pompeiians are only providing scans of their heads and upper chests. These scans also show the team that many of the victims have severe cranial injuries, undoubtedly due to falling rubble during the eruption of Vesuvius.

The scientists have now begun scanning on animals to accompany their results from the human remains.

Featured Image: Plaster cast containing a four-year-old boy from Pompeii being put in the CAT machine. Italy (Credit: Photoshot)

By Alicia McDermott

CT scanners are being used on the plaster casts of the Mount Vesuvius victims from Pompeii. Preliminary results show that, in general, they had great teeth and were in remarkably good health before the volcanic eruption. This new discovery goes against the commonly held belief that Romans were often hedonists that enjoyed consuming in excess whenever possible.

CT scanners are being used on the plaster casts of the Mount Vesuvius victims from Pompeii. Preliminary results show that, in general, they had great teeth and were in remarkably good health before the volcanic eruption. This new discovery goes against the commonly held belief that Romans were often hedonists that enjoyed consuming in excess whenever possible.Especially surprising for the scientists is that the ancient Pompeiians had great dental records, despite the poor dental care available in 79 AD. “They ate better than we did and have really good teeth.” Elisa Vanacore, a dental expert, said in a press release. The Pompeiians ate a diet high in fruits and vegetables and low in sugars. Apart from a healthy diet, “The initial results also show the high levels of fluorine that are present in the air and water here, near the volcano,” Vanacore continued. Fluorine may have been a beneficial or a detrimental factor to the dental and bone health of the Pompeiians depending on the quantity they consumed.

Scan of one of the plaster casts from Pompeii revealing a healthy set of teeth. (Credit: Napoli/Giino/Ropi/ZUMA Press/Newscom)30 of the 86 Pompeiian plaster casts have passed through the scanning process so far. The results are providing more details on the lives of the individuals found from the site. “It will reveal much about the victims: their age, sex, what they ate, what diseases they had and what class of society they belonged to. This will be a great step forward in our knowledge of antiquity.” Massimo Osanna, the archaeological superintendent of Pompeii, said.

Scan of one of the plaster casts from Pompeii revealing a healthy set of teeth. (Credit: Napoli/Giino/Ropi/ZUMA Press/Newscom)30 of the 86 Pompeiian plaster casts have passed through the scanning process so far. The results are providing more details on the lives of the individuals found from the site. “It will reveal much about the victims: their age, sex, what they ate, what diseases they had and what class of society they belonged to. This will be a great step forward in our knowledge of antiquity.” Massimo Osanna, the archaeological superintendent of Pompeii, said.For Stefania Giudice, a conservator from Naples national archaeological Museum, the Pompeiians are also taking on a more human importance as they continue to be studied: 'It can be very moving handling these remains. Even though it happened 2,000 years ago, it could be a boy, a mother or a family. It's human archaeology, not just archaeology.' These connections enhance the significance of the study for those involved as well.

The plaster casts of Pompeii victims were placed through CT scans to reveal what was underneath. Source: BigStockPhotoThe team is a multidisciplinary one that is composed of archaeologists, computer engineers, radiologists, and orthodontists. In conjunction with the CT scanners, they have also used a contrast dye that mimics the appearance of muscles and skin to accentuate the features of the victims. Together, the technologies are providing the images of the remains in vivid details.

The plaster casts of Pompeii victims were placed through CT scans to reveal what was underneath. Source: BigStockPhotoThe team is a multidisciplinary one that is composed of archaeologists, computer engineers, radiologists, and orthodontists. In conjunction with the CT scanners, they have also used a contrast dye that mimics the appearance of muscles and skin to accentuate the features of the victims. Together, the technologies are providing the images of the remains in vivid details.Decaying and Looted Pompeii Gets a Big Infusion of Care from the Italian GovernmentGiraffe and Sea Urchin on the Menu for People of PompeiiThe Houses of Pleasure in Ancient PompeiiPompeii of the East: 4,000 year-old victims of Chinese earthquake captured in their final momentsWhen the Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli first thought of plaster casting the remains in 1866, his goals were mostly to move and preserve the fragile bodies. Unfortunately, this delayed the process of analyzing the organic matter, until now.

Tomography is the process of creating a 2D image or 'slice' of a 3D object that allows doctors to search in detail for problems in their patients. It is in common use in hospitals and is becoming more familiar in archaeology as well.

One of the Pompeii victim’s scan results, Italy. Credit: The Archaeological Site of Pompeii.In this study the scientists are using a 16-layer CAT technology machine. “One of the problems we encountered was the density of chalk used for the cast technique. It is a density similar to bones, that's why we had to use the 16-layer CAT technology." Massimo Osanna explained.

One of the Pompeii victim’s scan results, Italy. Credit: The Archaeological Site of Pompeii.In this study the scientists are using a 16-layer CAT technology machine. “One of the problems we encountered was the density of chalk used for the cast technique. It is a density similar to bones, that's why we had to use the 16-layer CAT technology." Massimo Osanna explained.Another difficulty the team has had to contend with regarding the CT scanners is that they only allow individuals up to a 70 cm (27.6 inches) diameter to enter the machine. Thus the more robust Pompeiians are only providing scans of their heads and upper chests. These scans also show the team that many of the victims have severe cranial injuries, undoubtedly due to falling rubble during the eruption of Vesuvius.

The scientists have now begun scanning on animals to accompany their results from the human remains.

Featured Image: Plaster cast containing a four-year-old boy from Pompeii being put in the CAT machine. Italy (Credit: Photoshot)

By Alicia McDermott

Published on October 05, 2015 03:30

History Trivia - Byzantine Emperor Heraclius' fleet takes Constantinople

October 5

610 Byzantine Emperor Heraclius' fleet took Constantinople. He was responsible for introducing Greek as the Eastern Empire's official language.

869 4th Council of Constantinople (8th Ecumenical Council) opened.

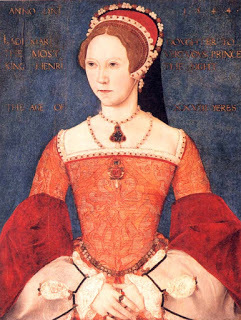

1553 Queen Mary's first Parliament met and declared Katherine of Aragon's marriage to Henry VIII legitimate, and also declared the Queen's birth legitimate.

610 Byzantine Emperor Heraclius' fleet took Constantinople. He was responsible for introducing Greek as the Eastern Empire's official language.

869 4th Council of Constantinople (8th Ecumenical Council) opened.

1553 Queen Mary's first Parliament met and declared Katherine of Aragon's marriage to Henry VIII legitimate, and also declared the Queen's birth legitimate.

Published on October 05, 2015 01:00

October 4, 2015

Religion in ancient Rome: what did they believe?

History Extra

Vulcan caught Venus and Mars in a net and shows them to the laughing Gods. (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images)

Vulcan caught Venus and Mars in a net and shows them to the laughing Gods. (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images)

“We Romans,” claimed the great orator Cicero in a public speech, “are not superior to the Spanish in population, nor do we best the Gauls in strength, nor Carthaginians in acumen, nor the Greeks in technical skills, nor can we compete with the natural connection of the Italians and Latins to their own people and land; we Romans, however, outstrip every people and nation in our piety, sense of religious scruple and our awareness that everything is controlled by the power of the gods.”

Cicero is hardly the only politician – ancient or modern – to have asserted that his people have a special relationship with the divine, but it is certainly striking that the evidence from Rome in his time (this speech was delivered in 56 BC) does reveal an incredible intensity and diversity of religious activity. The Romans lived in a world crowded with divinities, and they communicated with them almost constantly. Indeed, the following snapshots from Rome in the age of Cicero can show us just how the gods and their worship were woven into almost every part of the social fabric in the booming imperial capital…

Triumph in SeptemberIn late September 61 BC, the Roman general Pompey returned to Rome following conquests in the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East to celebrate his third and – although he did not yet know it – final triumph.

Rich treasures and a very large number of captives were paraded through the packed streets of the city; the general himself wore the cloak of Alexander the Great. It was, according to the later historian Appian, a dazzling celebration.

The culmination of this pageant was a sacrifice of white bulls to Jupiter Optimus Maximus – roughly ‘Jupiter the best and greatest’ [the god of sky and thunder and the chief deity of Roman state religion] – at his temple on the Capitoline Hill in the heart of the city.

In making this sacrifice, Pompey thanked the god for his support of Rome and demonstrated the supposed connection between the gods and the military success of Rome.

Watching the heavensIn ancient Rome, religion could divide as well as unite. This next snapshot dates from two years later: 59 BC, the year in which Julius Caesar – Pompey’s rival and eventual vanquisher – first held the supreme political office of consul.

Even at this early point in his career, Caesar was a polarising figure. The conservative Marcus Bibulus, who was his fellow chief magistrate for the year, used every tactic available to oppose Caesar’s agenda. Having exhausted conventional measures to block legislation, Bibulus shut himself in his house and used the traditional religious prerogative of the consul to declare that ill-omens forbade any public business.

Julius Caesar as dictator of Rome wearing a crown of laurel and holding a symbol of office. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Supporters of Caesar claimed that Bibulus was misusing the ritual – they said the declaration could not be made from home; only in public. Caesar ignored the bar on public business and proceeded to pass key laws.

Some modern historians have argued that this episode demonstrates that the Romans manipulated religion for political ends and did not really take it seriously. In fact, I would say the row, which was still being discussed years later, shows that the correct, ritual observance of omens was considered so important that it could become the very centre of political dispute.

Trendy SerapisOur third snapshot comes from the same decade as the snapshot previous. In one of his poems (Poem 10), the trendy young writer Catullus tells a revealing anecdote about himself and a couple of friends. Catullus was just back from a rich, Greek-speaking province in the east, where he had been a very junior member of the governor’s entourage. Keen to make out that he’d done well in the provinces, he lied that he had managed to bring back a sedan chair and also the slaves to carry it.

The girlfriend of one of his friends saw through the lie, however, and decided to set a trap for Catullus – she asked if she could borrow the chair to go over to the Temple of Serapis. Caught in the fib, Catullus had to admit that the sedan chair really belonged to another friend, and complained that she wasn’t being “cool”.

The woman’s destination is no incidental detail – the poet mentions it to give us an idea about her ‘type’. Serapis was not an old, respectable Roman god, but a controversial one recently ‘imported’ from Egypt. We might compare the attraction of the cult to the fashionable adoption of yoga and Buddhism in the contemporary west. By connecting her with this Egyptian deity, Catullus casts his tormentor as a trendy seeker of the exotic.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, who in 56 BC delivered a public speech about Romans' relationship with the divine. (Photo by ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Family mattersWithout modern medicine to rely upon, Romans turned to the divine in times of need: for example, a stone inscribed in c50–60 BC records the gratitude of a woman called Sulpicia to Juno Lucina, one of the Roman goddesses of childbirth. Sulpicia explains that her thanks to the goddess are on behalf of her daughter, Paulla Cassia.

It is safe to assume that Sulpicia had prayed to Juno while her daughter, Paulla, was in labour – perhaps a difficult one – with a grandchild.

A letter to the underworldThis next snapshot takes us beyond the walls of the city and out to the graveyards north of Rome. A woman scratches prayers on lead sheets at night, begging the underworld gods – Pluto, Proserpina and the three-headed dog Cerberus – to dismember her enemies: Plotius, Avonia, Vesonia, Secunda and Aquillia.

If the gods fulfil her wishes, she promises them a sacrifice of dates, figs and a black pig. To seal the prayer, she drives a nail through the lead sheets and buries them in a tomb – the conduit to the gods of the dead.

This appeal to the gods to harm enemies was a curse. Cicero was not thinking of this sort of thing when he proclaimed the piety of the Romans in 56 BC, but the principles underlying these prayers to the underworld are the same as those in the stories of Pompey and Sulpicia: the Romans communicated with the gods in prayer and sacrifice to maintain their favour and to seek advantage.

The gods of RomeAt the centre of Roman religion were the gods themselves. For us, this is one of the hardest things to understand about religion in ancient Rome. After all, few people believe in Roman gods, and we live in societies where scriptural monotheism [the belief in a single, all-powerful god] or atheism are the most common understandings of the divine.

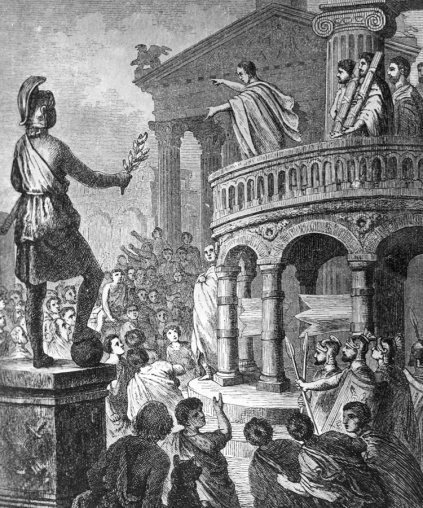

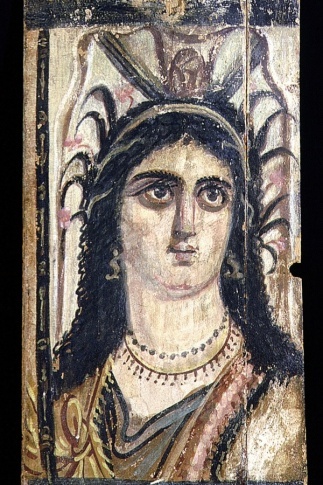

For the Romans, though, there were many gods and little fixed doctrine. Although the Roman state focused on a few important gods, like Jupiter, Juno, Mars and Apollo, for individuals there were countless possibilities, including exotic gods like Serapis [a Graeco-Egyptian god] and Isis [the patroness of nature and magic, first worshipped in ancient Egyptian religion]; and more homely deities like Mater Matuta [an indigenous Latin goddess] and Silvanus [a Roman deity of woods and fields]. The absence of scripture or a church orthodoxy allowed for a certain flexibility in how Romans thought about these gods.

Mythological stories about the gods, which mostly originated in Greece or in the old cultures of the Middle East, were very popular in Rome, and offered people the means to think through the nature of divine power. The stories did not always make the gods look good, but provided them with personalities and confirmed the possibility of their intervention in human affairs.

The Romans also conceived of the gods in visual terms, and worship focused on the anthropomorphic [human-like] images of the gods in temples and shrines. This had an impact: when the Romans thought about the god of commerce, Mercury, for example, they imagined him as a young man holding a bag of coins.

Depiction of Isis with crown supported by uraeus. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

For an educated few, the gods were also subject to philosophical speculation. Sceptics maintained that the gods were unknowable but that cult should be maintained anyway. Epicureans denied that gods worth the name would be amenable to human sacrifice and prayer, but accepted that they did exist, while Stoics insisted that the world itself was divine and that the many gods were a manifestation of that ‘world spirit’. It is, however, very difficult to find Roman sources that demonstrate atheism or strict monotheism.

We can imagine that a Gaul or Greek or Carthaginian, let alone a Jew or an Indian, might protest Cicero’s claim that the Romans were the most religious of ancient peoples. Nevertheless, the Rome of Cicero’s time was truly a place where the gods were a common and meaningful presence in the lives of people – ordinary, like Sulpicia and the curser in the graveyard, and extraordinary, like Cicero himself and Julius Caesar.

Duncan MacRae is a historian and assistant professor in the department of classics at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio. His work focuses on the history of the Roman Republic and early empire, particularly the history of religion and intellectual history.

To find out more, visit www.duncanmacrae.org.

Vulcan caught Venus and Mars in a net and shows them to the laughing Gods. (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images)

Vulcan caught Venus and Mars in a net and shows them to the laughing Gods. (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images) “We Romans,” claimed the great orator Cicero in a public speech, “are not superior to the Spanish in population, nor do we best the Gauls in strength, nor Carthaginians in acumen, nor the Greeks in technical skills, nor can we compete with the natural connection of the Italians and Latins to their own people and land; we Romans, however, outstrip every people and nation in our piety, sense of religious scruple and our awareness that everything is controlled by the power of the gods.”

Cicero is hardly the only politician – ancient or modern – to have asserted that his people have a special relationship with the divine, but it is certainly striking that the evidence from Rome in his time (this speech was delivered in 56 BC) does reveal an incredible intensity and diversity of religious activity. The Romans lived in a world crowded with divinities, and they communicated with them almost constantly. Indeed, the following snapshots from Rome in the age of Cicero can show us just how the gods and their worship were woven into almost every part of the social fabric in the booming imperial capital…

Triumph in SeptemberIn late September 61 BC, the Roman general Pompey returned to Rome following conquests in the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East to celebrate his third and – although he did not yet know it – final triumph.

Rich treasures and a very large number of captives were paraded through the packed streets of the city; the general himself wore the cloak of Alexander the Great. It was, according to the later historian Appian, a dazzling celebration.

The culmination of this pageant was a sacrifice of white bulls to Jupiter Optimus Maximus – roughly ‘Jupiter the best and greatest’ [the god of sky and thunder and the chief deity of Roman state religion] – at his temple on the Capitoline Hill in the heart of the city.

In making this sacrifice, Pompey thanked the god for his support of Rome and demonstrated the supposed connection between the gods and the military success of Rome.

Watching the heavensIn ancient Rome, religion could divide as well as unite. This next snapshot dates from two years later: 59 BC, the year in which Julius Caesar – Pompey’s rival and eventual vanquisher – first held the supreme political office of consul.

Even at this early point in his career, Caesar was a polarising figure. The conservative Marcus Bibulus, who was his fellow chief magistrate for the year, used every tactic available to oppose Caesar’s agenda. Having exhausted conventional measures to block legislation, Bibulus shut himself in his house and used the traditional religious prerogative of the consul to declare that ill-omens forbade any public business.

Julius Caesar as dictator of Rome wearing a crown of laurel and holding a symbol of office. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Supporters of Caesar claimed that Bibulus was misusing the ritual – they said the declaration could not be made from home; only in public. Caesar ignored the bar on public business and proceeded to pass key laws.

Some modern historians have argued that this episode demonstrates that the Romans manipulated religion for political ends and did not really take it seriously. In fact, I would say the row, which was still being discussed years later, shows that the correct, ritual observance of omens was considered so important that it could become the very centre of political dispute.

Trendy SerapisOur third snapshot comes from the same decade as the snapshot previous. In one of his poems (Poem 10), the trendy young writer Catullus tells a revealing anecdote about himself and a couple of friends. Catullus was just back from a rich, Greek-speaking province in the east, where he had been a very junior member of the governor’s entourage. Keen to make out that he’d done well in the provinces, he lied that he had managed to bring back a sedan chair and also the slaves to carry it.

The girlfriend of one of his friends saw through the lie, however, and decided to set a trap for Catullus – she asked if she could borrow the chair to go over to the Temple of Serapis. Caught in the fib, Catullus had to admit that the sedan chair really belonged to another friend, and complained that she wasn’t being “cool”.

The woman’s destination is no incidental detail – the poet mentions it to give us an idea about her ‘type’. Serapis was not an old, respectable Roman god, but a controversial one recently ‘imported’ from Egypt. We might compare the attraction of the cult to the fashionable adoption of yoga and Buddhism in the contemporary west. By connecting her with this Egyptian deity, Catullus casts his tormentor as a trendy seeker of the exotic.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, who in 56 BC delivered a public speech about Romans' relationship with the divine. (Photo by ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Family mattersWithout modern medicine to rely upon, Romans turned to the divine in times of need: for example, a stone inscribed in c50–60 BC records the gratitude of a woman called Sulpicia to Juno Lucina, one of the Roman goddesses of childbirth. Sulpicia explains that her thanks to the goddess are on behalf of her daughter, Paulla Cassia.

It is safe to assume that Sulpicia had prayed to Juno while her daughter, Paulla, was in labour – perhaps a difficult one – with a grandchild.

A letter to the underworldThis next snapshot takes us beyond the walls of the city and out to the graveyards north of Rome. A woman scratches prayers on lead sheets at night, begging the underworld gods – Pluto, Proserpina and the three-headed dog Cerberus – to dismember her enemies: Plotius, Avonia, Vesonia, Secunda and Aquillia.

If the gods fulfil her wishes, she promises them a sacrifice of dates, figs and a black pig. To seal the prayer, she drives a nail through the lead sheets and buries them in a tomb – the conduit to the gods of the dead.

This appeal to the gods to harm enemies was a curse. Cicero was not thinking of this sort of thing when he proclaimed the piety of the Romans in 56 BC, but the principles underlying these prayers to the underworld are the same as those in the stories of Pompey and Sulpicia: the Romans communicated with the gods in prayer and sacrifice to maintain their favour and to seek advantage.

The gods of RomeAt the centre of Roman religion were the gods themselves. For us, this is one of the hardest things to understand about religion in ancient Rome. After all, few people believe in Roman gods, and we live in societies where scriptural monotheism [the belief in a single, all-powerful god] or atheism are the most common understandings of the divine.

For the Romans, though, there were many gods and little fixed doctrine. Although the Roman state focused on a few important gods, like Jupiter, Juno, Mars and Apollo, for individuals there were countless possibilities, including exotic gods like Serapis [a Graeco-Egyptian god] and Isis [the patroness of nature and magic, first worshipped in ancient Egyptian religion]; and more homely deities like Mater Matuta [an indigenous Latin goddess] and Silvanus [a Roman deity of woods and fields]. The absence of scripture or a church orthodoxy allowed for a certain flexibility in how Romans thought about these gods.

Mythological stories about the gods, which mostly originated in Greece or in the old cultures of the Middle East, were very popular in Rome, and offered people the means to think through the nature of divine power. The stories did not always make the gods look good, but provided them with personalities and confirmed the possibility of their intervention in human affairs.

The Romans also conceived of the gods in visual terms, and worship focused on the anthropomorphic [human-like] images of the gods in temples and shrines. This had an impact: when the Romans thought about the god of commerce, Mercury, for example, they imagined him as a young man holding a bag of coins.

Depiction of Isis with crown supported by uraeus. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

For an educated few, the gods were also subject to philosophical speculation. Sceptics maintained that the gods were unknowable but that cult should be maintained anyway. Epicureans denied that gods worth the name would be amenable to human sacrifice and prayer, but accepted that they did exist, while Stoics insisted that the world itself was divine and that the many gods were a manifestation of that ‘world spirit’. It is, however, very difficult to find Roman sources that demonstrate atheism or strict monotheism.

We can imagine that a Gaul or Greek or Carthaginian, let alone a Jew or an Indian, might protest Cicero’s claim that the Romans were the most religious of ancient peoples. Nevertheless, the Rome of Cicero’s time was truly a place where the gods were a common and meaningful presence in the lives of people – ordinary, like Sulpicia and the curser in the graveyard, and extraordinary, like Cicero himself and Julius Caesar.

Duncan MacRae is a historian and assistant professor in the department of classics at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio. His work focuses on the history of the Roman Republic and early empire, particularly the history of religion and intellectual history.

To find out more, visit www.duncanmacrae.org.

Published on October 04, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Gregorian calendar reformed

October 4

1518 A treaty was signed between France and England that included a betrothal between Princess Mary and the young dauphin François.

1535 the first English translation of the entire bible was printed, with translations by Tyndale and Coverdale.

1582 the Gregorian calendar was reformed. To adjust the inaccuracy in the date caused by an extra day per century in the Julian calendar, Pope Gregory XIII ordered ten days to be subtracted from October of 1582. The calendar jumped from October 4 to October 15 and the new Gregorian calendar, used today, was devised.

1518 A treaty was signed between France and England that included a betrothal between Princess Mary and the young dauphin François.

1535 the first English translation of the entire bible was printed, with translations by Tyndale and Coverdale.

1582 the Gregorian calendar was reformed. To adjust the inaccuracy in the date caused by an extra day per century in the Julian calendar, Pope Gregory XIII ordered ten days to be subtracted from October of 1582. The calendar jumped from October 4 to October 15 and the new Gregorian calendar, used today, was devised.

Published on October 04, 2015 00:30

October 3, 2015

Lost 'Epic of Gilgamesh' Verse Depicts Cacophonous Abode of Gods

Live Science

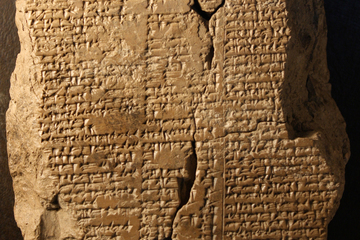

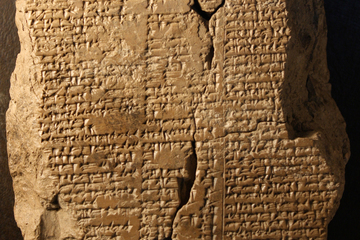

This clay tablet

This clay tablet in inscribed with one part of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It was most likely stolen from a historical site before it was sold to a museum in Iraq.

in inscribed with one part of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It was most likely stolen from a historical site before it was sold to a museum in Iraq.

Credit: Farouk Al-

A serendipitous deal between a history museum and a smuggler has provided new insight into one of the most famous stories ever told: "The Epic of Gilgamesh."

into one of the most famous stories ever told: "The Epic of Gilgamesh."

The new finding, a clay tablet, reveals a previously unknown "chapter" of the epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia. This new section brings both noise and color to a forest for the gods that was thought to be a quiet place in the work of literature. The newfound verse also reveals details about the inner conflict the poem's heroes endured.

In 2011, the Sulaymaniyah Museum in Slemani, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, purchased a set of 80 to 90 clay tablets from a known smuggler. The museum has been engaging in these backroom dealings as a way to regain valuable artifacts that disappeared from Iraqi historical sites and museums since the start of the American-led invasion of that country, according to the online nonprofit publication Ancient History Et Cetera.

from a known smuggler. The museum has been engaging in these backroom dealings as a way to regain valuable artifacts that disappeared from Iraqi historical sites and museums since the start of the American-led invasion of that country, according to the online nonprofit publication Ancient History Et Cetera.

Among the various tablets purchased, one stood out to Farouk Al-Rawi, a professor in the Department of Languages and Cultures of the Near and Middle East at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London. The large block of clay, etched with cuneiform writing, was still caked in mud when Al-Rawi advised the Sulaymaniyah Museum to purchase artifact for the agreed upon $800. [In Photos: See the Treasures of Mesopotamia]

of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London. The large block of clay, etched with cuneiform writing, was still caked in mud when Al-Rawi advised the Sulaymaniyah Museum to purchase artifact for the agreed upon $800. [In Photos: See the Treasures of Mesopotamia]

With the help of Andrew George, associate dean of languages and culture at SOAS and translator of "The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation" (Penguin Classics, 2000), Al-Rawi translated the tablet in just five days. The clay artifact could date as far back to the old-Babylonian period (2003-1595 B.C.), according to the Sulaymaniyah Museum. However, Al-Rawi and George said they believe it's a bit younger and was inscribed in the neo-Babylonian period (626-539 B.C.).