MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 140

October 28, 2015

A Toxic Price to Pay: Wealthy citizens in medieval Europe had poisoning from lead-glazed plates

Ancient Origins

Rich city dwellers in medieval northern Europe had elevated lead and mercury levels that probably caused them serious health problems. Fewer rural people, who were poorer, had elevated heavy metals and those that did had less of the toxins in their systems than city dwellers.

An analysis of medieval skeletons by a Danish research team shows poisonous lead had entered the bodies of people buried in cemeteries in northern Germany and Denmark. The study says the lead could have been introduced through several sources but rules out absorption after death.

The medieval people would not have known how poisonous lead is, of course, or they probably wouldn’t have used it to glaze their kitchenware and put it in coins. Other sources of the heavy metal in the villagers’ systems may have included the lead-lined roofs, where drinking water was collected, as well as stained-glass windows.

The researchers examined the remains of people from six cemeteries, both urban and rural, in the two countries and revealed high levels of lead and mercury for city dwellers. Fewer people who lived in the countryside had elevated levels, says a press release from Southern Denmark University.

A stained-glass window in Schleswig, German; remains in a cemetery there were analyzed for the study. Only the rich could afford such windows. (Photo by Frank Vincentz/

Wikimedia Commons

)Some of the symptoms of lead poisoning in kids include learning difficulties, developmental delay, loss of appetite and weight, vomiting, hearing loss, fatigue and sluggishness, according to WebMd. Constipation and abdominal pain affect both children and adults. WebMD.com says children are primarily at risk of lead poisoning, but adults too suffer ill effects from it, including high blood pressure, joint and muscle pains, lower mental function and headache. Adults also suffer from pain or numbness of extremities, bad moods, abnormal or reduced sperm counts and premature birth or miscarriage.

A stained-glass window in Schleswig, German; remains in a cemetery there were analyzed for the study. Only the rich could afford such windows. (Photo by Frank Vincentz/

Wikimedia Commons

)Some of the symptoms of lead poisoning in kids include learning difficulties, developmental delay, loss of appetite and weight, vomiting, hearing loss, fatigue and sluggishness, according to WebMd. Constipation and abdominal pain affect both children and adults. WebMD.com says children are primarily at risk of lead poisoning, but adults too suffer ill effects from it, including high blood pressure, joint and muscle pains, lower mental function and headache. Adults also suffer from pain or numbness of extremities, bad moods, abnormal or reduced sperm counts and premature birth or miscarriage.

The glazed pottery, used more in the more affluent towns than in the country, was a big source of lead, according to the press release from the University of Southern Denmark.

An aerial shot of Skt. Alberts cemetery on the island of Ærø, Denmark (Aegislash; Museum/

SDU

)They also studied bodies from cemeteries in St. Clements outside of Schleswig (Germany), Tirup outside of Horsens (Denmark), Nybøl in Jutland (Denmark) and St. Alberts Chapel on the island of Ærø (Denmark), the press release says,

An aerial shot of Skt. Alberts cemetery on the island of Ærø, Denmark (Aegislash; Museum/

SDU

)They also studied bodies from cemeteries in St. Clements outside of Schleswig (Germany), Tirup outside of Horsens (Denmark), Nybøl in Jutland (Denmark) and St. Alberts Chapel on the island of Ærø (Denmark), the press release says,

The team tested the skeletons mercury content. That element, also poisonous to humans, was employed in making red pigment cinnabar and for gilding. Medicines were also prepared from mercury to treat syphilis and leprosy, the press release states.

Again, city dwellers had more mercury than rural folk. Amazingly, about half the people examined had leprosy, which was treated with mercury.

Featured image: The skull of a young girl who suffered from syphilis; she would have been a candidate for treatment with mercury in the Middle Ages. (Birgitte Svennevig/ SDU )

By Mark Miller

Rich city dwellers in medieval northern Europe had elevated lead and mercury levels that probably caused them serious health problems. Fewer rural people, who were poorer, had elevated heavy metals and those that did had less of the toxins in their systems than city dwellers.

An analysis of medieval skeletons by a Danish research team shows poisonous lead had entered the bodies of people buried in cemeteries in northern Germany and Denmark. The study says the lead could have been introduced through several sources but rules out absorption after death.

The medieval people would not have known how poisonous lead is, of course, or they probably wouldn’t have used it to glaze their kitchenware and put it in coins. Other sources of the heavy metal in the villagers’ systems may have included the lead-lined roofs, where drinking water was collected, as well as stained-glass windows.

The researchers examined the remains of people from six cemeteries, both urban and rural, in the two countries and revealed high levels of lead and mercury for city dwellers. Fewer people who lived in the countryside had elevated levels, says a press release from Southern Denmark University.

"The exposure was higher and more dangerous in the urban communities, but lead was not completely unknown in the country. We saw that 30 percent of the rural individuals had been in contact with lead—although much less than the townspeople,” Professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen of University of Southern Denmark’s Department of Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy, said in the press release.

"Lead poisoning can be the consequence when ingesting lead, which is a heavy metal. In the Middle Ages you could almost not avoid ingesting lead, if you were wealthy or living in an urban environment. But what is perhaps more severe, is the fact that exposure to lead leads to lower intelligence of children.”

A stained-glass window in Schleswig, German; remains in a cemetery there were analyzed for the study. Only the rich could afford such windows. (Photo by Frank Vincentz/

Wikimedia Commons

)Some of the symptoms of lead poisoning in kids include learning difficulties, developmental delay, loss of appetite and weight, vomiting, hearing loss, fatigue and sluggishness, according to WebMd. Constipation and abdominal pain affect both children and adults. WebMD.com says children are primarily at risk of lead poisoning, but adults too suffer ill effects from it, including high blood pressure, joint and muscle pains, lower mental function and headache. Adults also suffer from pain or numbness of extremities, bad moods, abnormal or reduced sperm counts and premature birth or miscarriage.

A stained-glass window in Schleswig, German; remains in a cemetery there were analyzed for the study. Only the rich could afford such windows. (Photo by Frank Vincentz/

Wikimedia Commons

)Some of the symptoms of lead poisoning in kids include learning difficulties, developmental delay, loss of appetite and weight, vomiting, hearing loss, fatigue and sluggishness, according to WebMd. Constipation and abdominal pain affect both children and adults. WebMD.com says children are primarily at risk of lead poisoning, but adults too suffer ill effects from it, including high blood pressure, joint and muscle pains, lower mental function and headache. Adults also suffer from pain or numbness of extremities, bad moods, abnormal or reduced sperm counts and premature birth or miscarriage.The glazed pottery, used more in the more affluent towns than in the country, was a big source of lead, according to the press release from the University of Southern Denmark.

"In those days lead oxide was used to glaze pottery. It was practical to clean the plates and looked beautiful, so it was understandably in high demand. But when they kept salty and acidic foods in glazed pots, the surface of the glaze would dissolve and the lead would leak into the food," Rasmussen said.Rasmussen and colleagues examined 207 skeletons from cemeteries in Rathaus Markt in Schleswig (Germany) and Ole Worms Gade in Horsens (Denmark). The remains from both were from medieval cemeteries in wealthier towns that had more contact with the world than people in the countryside.

An aerial shot of Skt. Alberts cemetery on the island of Ærø, Denmark (Aegislash; Museum/

SDU

)They also studied bodies from cemeteries in St. Clements outside of Schleswig (Germany), Tirup outside of Horsens (Denmark), Nybøl in Jutland (Denmark) and St. Alberts Chapel on the island of Ærø (Denmark), the press release says,

An aerial shot of Skt. Alberts cemetery on the island of Ærø, Denmark (Aegislash; Museum/

SDU

)They also studied bodies from cemeteries in St. Clements outside of Schleswig (Germany), Tirup outside of Horsens (Denmark), Nybøl in Jutland (Denmark) and St. Alberts Chapel on the island of Ærø (Denmark), the press release says,The team tested the skeletons mercury content. That element, also poisonous to humans, was employed in making red pigment cinnabar and for gilding. Medicines were also prepared from mercury to treat syphilis and leprosy, the press release states.

Again, city dwellers had more mercury than rural folk. Amazingly, about half the people examined had leprosy, which was treated with mercury.

Featured image: The skull of a young girl who suffered from syphilis; she would have been a candidate for treatment with mercury in the Middle Ages. (Birgitte Svennevig/ SDU )

By Mark Miller

Published on October 28, 2015 03:30

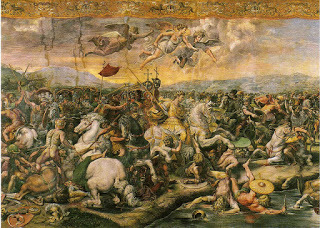

History Trivia - Constantine I victorious at Milvian Bridge.

October 28

312 Constantine I defeated Maxentius and became the sole ruler of the Roman empire in the west with victory at the Milvian Bridge.

1017 Emperor Henry III was born. Holy Roman Emperor and German King, Henry was the last emperor to effectively dominate the papacy.

1216 Henry III of England was crowned. Henry was the first English monarch to be crowned while still a minor.

312 Constantine I defeated Maxentius and became the sole ruler of the Roman empire in the west with victory at the Milvian Bridge.

1017 Emperor Henry III was born. Holy Roman Emperor and German King, Henry was the last emperor to effectively dominate the papacy.

1216 Henry III of England was crowned. Henry was the first English monarch to be crowned while still a minor.

Published on October 28, 2015 00:30

October 27, 2015

Hiker stumbles upon 1,200-year-old Viking sword while walking an ancient trail in Norway

Ancient Origins

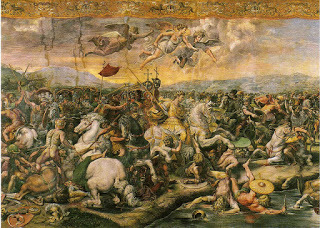

A hiker in Norway has discovered an ancient sword while walking an ancient route in the mountains of Haukeli. The well-preserved sword has been dated to the 8th century and is typical of a sword belonging to the Viking Age.

A hiker in Norway has discovered an ancient sword while walking an ancient route in the mountains of Haukeli. The well-preserved sword has been dated to the 8th century and is typical of a sword belonging to the Viking Age.The discovery was announced by Hordaland County Council, which described the weapon as a double-edged sword that is 30 inches (77 centimeters) long and made of wrought iron. Although in good condition, the sword is missing its handle. It is believed to date back to around 750 AD.

The sword was found by hiker Goran Olsen while walking on an old route that runs between western and eastern Norway. Olsen had stopped for a rest, when he spotted the weapon underneath some rocks.

Sword of Late Viking Age Burial Unveiled Exhibiting Links Between Norway and England A Step Closer to the Mysterious Origin of the Viking Sword Ulfberht

Goran Olsen was walking in the mountains of Haukeli when he stumbled upon the old Viking sword (Eirik Apeland / flickr)County Conservator Per Morten Ekerhovd said that the sword had been preserved by the frost and snow that covers the area for at least 6 months of the year.

Goran Olsen was walking in the mountains of Haukeli when he stumbled upon the old Viking sword (Eirik Apeland / flickr)County Conservator Per Morten Ekerhovd said that the sword had been preserved by the frost and snow that covers the area for at least 6 months of the year.“It’s quite unusual to find remnants from the Viking age that are so well preserved … it might be used today if you sharpened the edge,” Ekerhovd told CNN. "We are really happy that this person found the sword and gave it to us. It will shed light on our early history. It's a very (important) example of the Viking age."Ten Legendary Swords from the Ancient World Mysterious Viking Sword Made With Technology From the Future? A Status Symbol?After its discovery, the sword was examined by archaeologist Jostein Aksdal of Hordaland County Council. Aksdal told the Mail Online that it was unusual to find a sword of its type today. He speculates that, due to the high cost of extracting iron, the sword likely belonged to a wealthy individual and would have been somewhat of a status symbol, to “show power”.

Viking swords often had handles that were richly decorated with intricate designs in silver, copper, and bronze. The higher the status of the individual that yielded the sword, the more elaborate the grip.

An elaborate Viking sword hilt, 9th century, Museum of Scotland (

Wikimedia Commons

)While the sword discovery is rare and exciting, it does not bear the mark of a Viking Ulfberht sword. The superstrong Ulfberht swords, of which about 170 have been found, were made of metal so pure that scientists were long baffled as to how they mastered such advanced metallurgy eight centuries prior to the Industrial Revolution.

An elaborate Viking sword hilt, 9th century, Museum of Scotland (

Wikimedia Commons

)While the sword discovery is rare and exciting, it does not bear the mark of a Viking Ulfberht sword. The superstrong Ulfberht swords, of which about 170 have been found, were made of metal so pure that scientists were long baffled as to how they mastered such advanced metallurgy eight centuries prior to the Industrial Revolution. An Ulfberht sword displayed at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany. (Martin Kraft/Wikimedia Commons)The newly discovered Viking Sword is currently undergoing preservation at the University Museum of Bergen and plans are underway to conduct a research expedition to explore the area further. It is hoped that the sword may be one of many artifacts at the site.

An Ulfberht sword displayed at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany. (Martin Kraft/Wikimedia Commons)The newly discovered Viking Sword is currently undergoing preservation at the University Museum of Bergen and plans are underway to conduct a research expedition to explore the area further. It is hoped that the sword may be one of many artifacts at the site.Featured image: 8th century Viking sword discovered by a hiker in Norway. Credit: Hordaland Country Council.

By: April Holloway

Published on October 27, 2015 03:30

History Trivia - Constantine the Great receives Vision of the Cross.

October 27

312 Constantine the Great is said to have received his famous Vision of the Cross.

939 Athelstan died. Athelstan was the first West Saxon king to have effective rule over the whole of England. He was succeeded by Edmund I as King of England.

1401 Catherine of Valois was born. The neglected daughter of King Charles VI of France, Catherine married King Henry V of England and gave birth to his son, Henry VI. After her husband's untimely death, she began a relationship with Owen Tudor, and married him in secret. One of their sons was the father of King Henry VII.

.

312 Constantine the Great is said to have received his famous Vision of the Cross.

939 Athelstan died. Athelstan was the first West Saxon king to have effective rule over the whole of England. He was succeeded by Edmund I as King of England.

1401 Catherine of Valois was born. The neglected daughter of King Charles VI of France, Catherine married King Henry V of England and gave birth to his son, Henry VI. After her husband's untimely death, she began a relationship with Owen Tudor, and married him in secret. One of their sons was the father of King Henry VII.

.

Published on October 27, 2015 00:00

October 26, 2015

Medieval Village with Human Remains Discovered in Northern Spain

Ancient Origins

Medieval Village with Human Remains Discovered in Northern SpainThe medieval village of Arganzón has been brought to light in the area of Condado de Treviño, Burgos, Spain. Through a series of excavations, tombs, houses, and silos from the Middle Ages, as well as a convent from the early seventeenth century, have been uncovered.

Medieval Village with Human Remains Discovered in Northern SpainThe medieval village of Arganzón has been brought to light in the area of Condado de Treviño, Burgos, Spain. Through a series of excavations, tombs, houses, and silos from the Middle Ages, as well as a convent from the early seventeenth century, have been uncovered.

A team of archaeologists belonging to the research group Heritage and Cultural Landscapes, of the Universidad del País Vasco discovered the medieval village and Franciscan convent in the Zadorra river valley near the current town of La Puebla de Arganzón. However, NCYT Amazings reports that the formation of medieval villages and towns followed a very different process in the valley of the Zadorra than in other nearby areas.

Excavations and FindingsThe medieval village found in the excavations contains a large number of buildings, with one key feature being a large rectangular tower. This tower has walls about two meters (6.6 feet) wide and a height of about three meters (9.8 feet). A residential building made of sillarejo (carved stone blocks) has also been discovered at the site, according to reports from the Municipality’s official website .

View of the modern Puebla de Arganzón, located near the medieval village of Arganzón (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)In addition, the excavations have pinpointed a large cemetery with anthropomorphic tombs, graves enclosed by stone slabs, and burials carried out directly on the rock, dated before the year 1000 AD. “Anthropological studies have shown that the cemetery contains both children and adults, young and old, men and women - in short, the entire Arganzón community were buried here,”

Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo

, director of the project,

said

.

View of the modern Puebla de Arganzón, located near the medieval village of Arganzón (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)In addition, the excavations have pinpointed a large cemetery with anthropomorphic tombs, graves enclosed by stone slabs, and burials carried out directly on the rock, dated before the year 1000 AD. “Anthropological studies have shown that the cemetery contains both children and adults, young and old, men and women - in short, the entire Arganzón community were buried here,”

Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo

, director of the project,

said

.

The Spanish Inquisition: The Truth behind the Dark Legend (Part I)Scientists Believe they Have Found the Origins of the Unique Basque Culture‘Historical Amnesia’ has led to forgotten achievements of Muslim cultureIt has also been possible to identify some houses close to the cemetery, which were in use during the Middle Ages. These structures appear to have been built on stone and enclosed with ephemeral (short-lived) materials. Other interesting findings at the site include several silos that were used for grain storage.

Excavations have shown several silos for the storage of grain. (

UPV-EHU / Courier

)Apart from these finds, archaeologists have discovered that in 1615 the Franciscan convent of Our Lady of Conception was founded on the old Church of Santa Maria. Excavations have recovered a partial plan of the monastery, which includes the convent church, a large cloister, a garden, and other outer buildings. Inside the church they have uncovered numerous burials. One of the especially interesting graves contains a skeleton with a bone rosary around the neck. Several ceramic vessels, such as food dishes, have also been recovered at the monastery.

Excavations have shown several silos for the storage of grain. (

UPV-EHU / Courier

)Apart from these finds, archaeologists have discovered that in 1615 the Franciscan convent of Our Lady of Conception was founded on the old Church of Santa Maria. Excavations have recovered a partial plan of the monastery, which includes the convent church, a large cloister, a garden, and other outer buildings. Inside the church they have uncovered numerous burials. One of the especially interesting graves contains a skeleton with a bone rosary around the neck. Several ceramic vessels, such as food dishes, have also been recovered at the monastery.

The monastery, which was in use until 1834, was rebuilt and restored several times, as shown by the different types of floors and walls. Nonetheless, the Battle of Vitoria and the Carlist Wars severely damaged the monastery and this destruction eventually led to its abandonment.

History of ArganzónArganzón, located on the outskirts of the ancient Roman city of Iruña , was founded around the sixth century. The first written references about this medieval village are from the year 801, when the Batalla de las Conchas de Arganzón took place around the village. In this battle a Christian contingent ambushed Arab forces during one of the raids of Alava and Castile .

Invisible Killers - Poisons may have been used by Palaeolithic society 30,000 years ago, new testing showsArmillary Spheres: Following Celestial Objects in the Ancient WorldMystery of the Knights Templars: Protectors or Treasure Hunters on a Secret Mission?Later, in the year 871, a document mentions the church of Santa María de Arganzón, referring to how Mr. Arroncio donated various assets received in his inheritance to the monastery. As Arroncio came from the León family of the Northwest, some scholars have assumed that Arganzón was repopulated by people from that area.

Despite this connection, the newspaper El Correo points out that the researchers have come to other conclusions, and that the villages and medieval towns of the valley of the Zadorra followed a very different process from other towns of that time. “In other words, Arganzón was not formed as a result of repopulation carried out by settlers from other parts of northern Spain in the ninth century, but was the result of a local initiative.” According to Juan Antonio Quirós.

The Arganzón castle was built around the time of the village’s foundation in 1000 and is still partially preserved. The village, of great importance throughout the centuries, continued to be inhabited even after the foundation, in the late twelfth century, of the neighboring Puebla de Arganzón. Finally, the older Arganzón was permanently abandoned in the late Middle Ages, although the church was still maintained in later centuries.

Tower of the Arganzón castle, built circa 1000. (

UPV / EHU-Agencia Sinc

)Featured image: Some of the graves enclosed by stone slabs found in the medieval cemetery of Arganzón. (

UPV-EHU / NCYT Amazings

)

Tower of the Arganzón castle, built circa 1000. (

UPV / EHU-Agencia Sinc

)Featured image: Some of the graves enclosed by stone slabs found in the medieval cemetery of Arganzón. (

UPV-EHU / NCYT Amazings

)

By: Mariló TA

This article was first published in Spanish at https://www.ancient-origins.es/ and has been translated with permission.

Medieval Village with Human Remains Discovered in Northern SpainThe medieval village of Arganzón has been brought to light in the area of Condado de Treviño, Burgos, Spain. Through a series of excavations, tombs, houses, and silos from the Middle Ages, as well as a convent from the early seventeenth century, have been uncovered.

Medieval Village with Human Remains Discovered in Northern SpainThe medieval village of Arganzón has been brought to light in the area of Condado de Treviño, Burgos, Spain. Through a series of excavations, tombs, houses, and silos from the Middle Ages, as well as a convent from the early seventeenth century, have been uncovered.A team of archaeologists belonging to the research group Heritage and Cultural Landscapes, of the Universidad del País Vasco discovered the medieval village and Franciscan convent in the Zadorra river valley near the current town of La Puebla de Arganzón. However, NCYT Amazings reports that the formation of medieval villages and towns followed a very different process in the valley of the Zadorra than in other nearby areas.

Excavations and FindingsThe medieval village found in the excavations contains a large number of buildings, with one key feature being a large rectangular tower. This tower has walls about two meters (6.6 feet) wide and a height of about three meters (9.8 feet). A residential building made of sillarejo (carved stone blocks) has also been discovered at the site, according to reports from the Municipality’s official website .

View of the modern Puebla de Arganzón, located near the medieval village of Arganzón (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)In addition, the excavations have pinpointed a large cemetery with anthropomorphic tombs, graves enclosed by stone slabs, and burials carried out directly on the rock, dated before the year 1000 AD. “Anthropological studies have shown that the cemetery contains both children and adults, young and old, men and women - in short, the entire Arganzón community were buried here,”

Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo

, director of the project,

said

.

View of the modern Puebla de Arganzón, located near the medieval village of Arganzón (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)In addition, the excavations have pinpointed a large cemetery with anthropomorphic tombs, graves enclosed by stone slabs, and burials carried out directly on the rock, dated before the year 1000 AD. “Anthropological studies have shown that the cemetery contains both children and adults, young and old, men and women - in short, the entire Arganzón community were buried here,”

Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo

, director of the project,

said

.The Spanish Inquisition: The Truth behind the Dark Legend (Part I)Scientists Believe they Have Found the Origins of the Unique Basque Culture‘Historical Amnesia’ has led to forgotten achievements of Muslim cultureIt has also been possible to identify some houses close to the cemetery, which were in use during the Middle Ages. These structures appear to have been built on stone and enclosed with ephemeral (short-lived) materials. Other interesting findings at the site include several silos that were used for grain storage.

Excavations have shown several silos for the storage of grain. (

UPV-EHU / Courier

)Apart from these finds, archaeologists have discovered that in 1615 the Franciscan convent of Our Lady of Conception was founded on the old Church of Santa Maria. Excavations have recovered a partial plan of the monastery, which includes the convent church, a large cloister, a garden, and other outer buildings. Inside the church they have uncovered numerous burials. One of the especially interesting graves contains a skeleton with a bone rosary around the neck. Several ceramic vessels, such as food dishes, have also been recovered at the monastery.

Excavations have shown several silos for the storage of grain. (

UPV-EHU / Courier

)Apart from these finds, archaeologists have discovered that in 1615 the Franciscan convent of Our Lady of Conception was founded on the old Church of Santa Maria. Excavations have recovered a partial plan of the monastery, which includes the convent church, a large cloister, a garden, and other outer buildings. Inside the church they have uncovered numerous burials. One of the especially interesting graves contains a skeleton with a bone rosary around the neck. Several ceramic vessels, such as food dishes, have also been recovered at the monastery.The monastery, which was in use until 1834, was rebuilt and restored several times, as shown by the different types of floors and walls. Nonetheless, the Battle of Vitoria and the Carlist Wars severely damaged the monastery and this destruction eventually led to its abandonment.

History of ArganzónArganzón, located on the outskirts of the ancient Roman city of Iruña , was founded around the sixth century. The first written references about this medieval village are from the year 801, when the Batalla de las Conchas de Arganzón took place around the village. In this battle a Christian contingent ambushed Arab forces during one of the raids of Alava and Castile .

Invisible Killers - Poisons may have been used by Palaeolithic society 30,000 years ago, new testing showsArmillary Spheres: Following Celestial Objects in the Ancient WorldMystery of the Knights Templars: Protectors or Treasure Hunters on a Secret Mission?Later, in the year 871, a document mentions the church of Santa María de Arganzón, referring to how Mr. Arroncio donated various assets received in his inheritance to the monastery. As Arroncio came from the León family of the Northwest, some scholars have assumed that Arganzón was repopulated by people from that area.

Despite this connection, the newspaper El Correo points out that the researchers have come to other conclusions, and that the villages and medieval towns of the valley of the Zadorra followed a very different process from other towns of that time. “In other words, Arganzón was not formed as a result of repopulation carried out by settlers from other parts of northern Spain in the ninth century, but was the result of a local initiative.” According to Juan Antonio Quirós.

The Arganzón castle was built around the time of the village’s foundation in 1000 and is still partially preserved. The village, of great importance throughout the centuries, continued to be inhabited even after the foundation, in the late twelfth century, of the neighboring Puebla de Arganzón. Finally, the older Arganzón was permanently abandoned in the late Middle Ages, although the church was still maintained in later centuries.

Tower of the Arganzón castle, built circa 1000. (

UPV / EHU-Agencia Sinc

)Featured image: Some of the graves enclosed by stone slabs found in the medieval cemetery of Arganzón. (

UPV-EHU / NCYT Amazings

)

Tower of the Arganzón castle, built circa 1000. (

UPV / EHU-Agencia Sinc

)Featured image: Some of the graves enclosed by stone slabs found in the medieval cemetery of Arganzón. (

UPV-EHU / NCYT Amazings

)By: Mariló TA

This article was first published in Spanish at https://www.ancient-origins.es/ and has been translated with permission.

Published on October 26, 2015 03:30

History Trivia - Alfred the Great dies

October 26

899 King Alfred the Great died in Wessex. The actual year is not certain, but the year 901 as stated in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is suspect. How he died is unknown. He was originally buried temporarily in the Old Minster in Winchester, then moved to the New Minster. When the New Minster moved to Hyde, a little north of the city, in 1110, the monks transferred to Hyde Abbey along with Alfred's body and those of his wife and children. Soon after the dissolution of the abbey in 1539, during the reign of Henry VIII, the church was demolished, leaving the graves intact. The royal graves and many others were probably rediscovered by chance in 1788 when a prison was being constructed by convicts on the site. Coffins were stripped of lead, bones were scattered and lost, and no identifiable remains of Alfred have subsequently been found. Further excavations in 1866 and 1897 were inconclusive.

899 King Alfred the Great died in Wessex. The actual year is not certain, but the year 901 as stated in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is suspect. How he died is unknown. He was originally buried temporarily in the Old Minster in Winchester, then moved to the New Minster. When the New Minster moved to Hyde, a little north of the city, in 1110, the monks transferred to Hyde Abbey along with Alfred's body and those of his wife and children. Soon after the dissolution of the abbey in 1539, during the reign of Henry VIII, the church was demolished, leaving the graves intact. The royal graves and many others were probably rediscovered by chance in 1788 when a prison was being constructed by convicts on the site. Coffins were stripped of lead, bones were scattered and lost, and no identifiable remains of Alfred have subsequently been found. Further excavations in 1866 and 1897 were inconclusive.

Published on October 26, 2015 00:00

October 25, 2015

Mr. Chuckles conjures up Rose Edmunds while stirring the Wizard's Cauldron

The Wizard speaks:

Rose Edmunds makes a first appearance around the Cauldron this Sunday.

Once a high flying corporate tax advisor, Rose left that behind to write well-received financial thrillers on the sun drenched south coast of England.

Working squarely in the tradition of Grisham and Ridpath, Rose is part of a growing coterie of authors whose work is framed by the context of the Crash of 2008, examining its causes, consequences and its impact on the people who both detonated the explosion and those who were its collateral damage.

Read more

Published on October 25, 2015 06:29

Life of the Week: King Cnut

History Extra

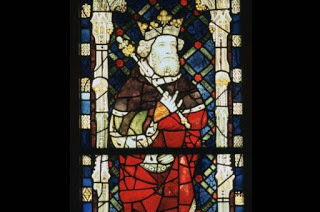

A stained glass window of King Cnut at Canterbury Cathedral. (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images) This week, the long-awaited Anglo-Saxon drama series The Last Kingdom airs on BBC Two. This eight-part series follows the lives of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, who in the 11th century battled it out to conquer the kingdom of England.

A stained glass window of King Cnut at Canterbury Cathedral. (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images) This week, the long-awaited Anglo-Saxon drama series The Last Kingdom airs on BBC Two. This eight-part series follows the lives of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, who in the 11th century battled it out to conquer the kingdom of England.Here, we look at the life of the warring king, Cnut…

Born: c985–995 AD, Denmark

Died: AD 12 November 1035, Dorset, England

Ruled England: AD 1016–1035

Remembered for: Conquering kingdoms across northern Europe and becoming king of England, Denmark, Norway, and areas of Sweden.

Family: Cnut’s father was the Danish prince Svein ‘Forkbeard’, who became king of England in 1013. Little is known about Cnut’s mother, but it has been suggested that she may have been the daughter of King Mieszko I of Poland.

Cnut married Ælfgifu of Northampton (date unknown), and together they had two children named Svein and Harold. However, it has been suggested that the church did not officially recognise this marriage, for reasons that are unclear, thus Cnut was allowed to marry again.

Cnut married Emma of Normandy in 1017, and they had two children – a son named Harthacnut and a daughter named Gunhilda.

His life: The exact date and location of Cnut’s birth is unknown, and there is little evidence of his upbringing in the 10th century.

Cnut grew up at a time when the crown of England was being ferociously fought over by the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings. In 1013, Cnut and his father, Svein, invaded England and deposed the king, Æthelred ‘The Unready’. Svein was proclaimed as king, but he died just a few months later on 3 February 1014. The English nobles then invited Æthelred ‘The Unready’ to return to the throne.

Upon learning of his father’s death, Cnut began planning an invasion of England to take the crown for himself. In 1015, Æthelred’s health deteriorated and England became divided over who should succeed the throne if he were to die. Some parts of the country allied with Cnut and the Vikings, while others showed support for Æthelred’s son, Edmund Ironside.

Following Æthelred’s death in April 1016, war broke out across southern England between Cnut and Edmund. After months of warfare, Edmund died on 30 November 1016, most probably after sustaining battle wounds. Cnut was now the undisputed successor to the English throne, and he was crowned at the Old St Paul’s cathedral in January 1017.

A silver penny from the reign of King Cnut. (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images)

In order to secure his position as king of England, Cnut married Æthelred’s widow, Emma of Normandy, in 1017. He also had any remaining enemies killed, and he exiled members of Æthelred’s family who were possible threats to his position on the throne.

In 1018, Cnut’s brother, Harald, the king of Denmark, died, and Cnut succeeded to the Danish throne. In 1027, Cnut traveled to Scotland where the Scottish kings acknowledged Cnut as the legitimate ruler of England, bringing peace to the two rivaling countries.

In 1027, Cnut also went on a pilgrimage to Rome, where he made alliances with the Pope and attended the coronation of Conrad II, the Holy Roman emperor. In 1028 Cnut expanded his empire further when he invaded Norway and placed his illegitimate son, Svein, as the governor there.

In England, Cnut attempted to gain the support of the church by giving gifts to different parish churches and monasteries, and he also oversaw the building of new churches across the country. Cnut was praised by his contemporaries for strictly enforcing English law and justice, and he strengthened the crown’s finances by establishing new trade routes between England and Scandinavia. Cnut successfully created a unified England, and it has been suggested that he was the first English ruler to not face any internal rebellions throughout his reign.

According to legend, Cnut’s circle of courtiers in England was so convinced of his power that they believed he could control the tides of the sea. Cnut saw this as an opportunity to demonstrate that, despite being king, he was not unaccountable to God. To prove this, he ordered that his throne be carried to the seashore. There, he sat on his throne and proved to his courtiers that he could not make the tides change, and in doing so demonstrated that God held power over everyone on Earth.

According to Henry of Huntingdon’s 12th-century chronicle, Cnut then announced: “Let all men know how empty and worthless is the power of kings. For there is none worthy of the name but God, whom heaven, earth and sea obey”.

Cnut died in Dorset, England, on 12 November 1035. The English crown was succeeded by his son Harold I. Cnut was buried in Winchester, which was the capital of the kingdom of Wessex, and his remains are now held in Winchester Cathedral.

The first episode of The Last Kingdom airs on Thursday 22 October at 9pm on BBC Two. To find out more, click here .

Published on October 25, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Henry V victorious at the Battle of Agincourt

October 25

1154 King Stephen of Blois (grandson of William the Conqueror) died. After the death of King Henry I, Stephen took the throne, preventing Henry's daughter Matilda from ruling, and setting off a civil war.

1400 Geoffrey Chaucer died at the age of 57. He was the first poet to be buried in Westminster Abbey.

1415, in Northern France, England led by Henry V won the Battle of Agincourt over France during the Hundred Years' War. Almost 6000 Frenchmen were killed while fewer than 400 were lost by the English.

1154 King Stephen of Blois (grandson of William the Conqueror) died. After the death of King Henry I, Stephen took the throne, preventing Henry's daughter Matilda from ruling, and setting off a civil war.

1400 Geoffrey Chaucer died at the age of 57. He was the first poet to be buried in Westminster Abbey.

1415, in Northern France, England led by Henry V won the Battle of Agincourt over France during the Hundred Years' War. Almost 6000 Frenchmen were killed while fewer than 400 were lost by the English.

Published on October 25, 2015 01:00

October 24, 2015

The Anglo-Saxon who (almost) united Britain

History Extra

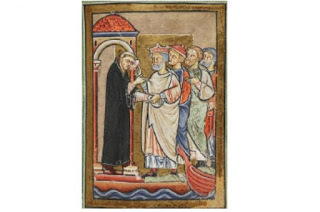

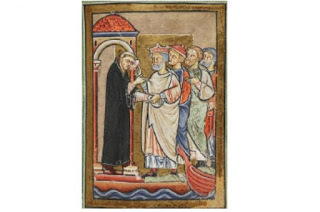

An illustration from Bede’s The Life of St Cuthbert shows Ecgfrith visiting St Cuthbert at Lindisfarne. © AKG Images

An illustration from Bede’s The Life of St Cuthbert shows Ecgfrith visiting St Cuthbert at Lindisfarne. © AKG Images

On Saturday 20 May AD 685, St Cuthbert was with Iurmenburh, Northumbria’s queen, at Carlisle, when he had a vision of Iurmenburh’s husband, Ecgfrith, dying at the hands of the Picts. A few days later, “they heard that it was announced far and wide that a wretched and lamentable battle had taken place at the very day and hour it was revealed to him”.

Ecgfrith was dead, and the flower of his army had fallen. For Northumbria, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that spanned much of what is now northern England and south-east Scotland, it was a fateful day. Bede, the English monk and author, later quoted from Virgil’s Aeneid: “The hope and valour of the realm of the English began ‘to ebb and flow away’.”

The Picts recovered lands previously taken from them and the Scots and northern Britons threw off English overlordship. The Northumbrians’ dream of exercising power across all of Britain was finally extinguished.

In the sixth and seventh centuries, Britain was a world of small kingships. Minor rulers found it necessary to look to more powerful kings for protection. The resulting regional kingships could be volatile and short-term but – thanks to a combination of dynastic alliances, Christian missions, raids and wars, sometimes pursued over considerable distances – a pattern of larger kingdoms slowly emerged, absorbing smaller neighbours.

Occasionally, in the seventh century, the most successful rulers established a Britain-wide, ‘over-’ or ‘high-kingship’ – by which every local or regional king in the whole island recognised the superiority of just one man. It was this supreme power that Ecgfrith lost his life trying to attain in 685.

Imperial ruleOf course, the idea of an overall authority across Britain (attempted, if not realised) stems ultimately from the ancient Romans, whose emperors were later understood locally as high-kings ruling over British kings.

This notion of a high-kingship was developed by Bede, who employed the word imperium in reference to both Roman and English supremacies.

Bede listed seven kings who had imperium south of the Humber, the last three of which were Northumbrians – Edwin, Oswald and Oswiu – whose power was centred further north. These, Bede tells us, had greater power: Edwin achieved authority over Anglesey and Man; Oswald ruled “within the same bounds” in this list, but Bede later claimed for him authority over all peoples speaking English, Welsh, Scottish and Pictish.

Finally, Oswiu additionally “overwhelmed and made tributary the greater part of the peoples of the Picts and Scots who inhabit the northern limits of Britain”. We can certainly see Oswiu as all-powerful in the years after 655, when he defeated the Mercians and took over much of the English Midlands and Fife in Scotland, becoming overlord of the northern kings beyond.

Bede visualised a progression, therefore, from ‘over-kingship’ of the south to a Northumbrian ‘high-kingship’ of all Britain. The subordination of all the other peoples of Britain to the (Northumbrian) English was, in Bede’s view, God’s plan for the island.

The one high-king who Bede omitted from this list was Ecgfrith, Oswiu’s son and heir, and a king who has not perhaps received as much attention as he deserves. He came to the throne of the Northumbrians, aged about 25, following his father’s death in 670.

An almost immediate challenge came from his father’s erstwhile northern tributaries, for the Picts rose against him, seeking to throw off English overlordship and recapture the Pictish territory that Oswiu had taken under Northumbrian rule. Ecgfrith may have been new to the throne but he was more than equal to the Picts’ challenge. He marched north and won an overwhelming victory against them, reimposing tribute, confirming his hold on Fife and instigating regime change.

At home, though, Ecgfrith was experiencing serious difficulties. At the root of his problems was a split in the Northumbrian church. On one side were the majority of the clergy, who had been trained within the Scottish tradition (centred on Lindisfarne, Melrose and Whitby), but had conformed to the Roman dating of Easter in 664.

On the other side of the divide was Bishop Wilfrid, who had adopted the continental view that British and Scottish churches were heretical, and was now moving energetically against British priests within Northumbria, expelling them by force of arms.

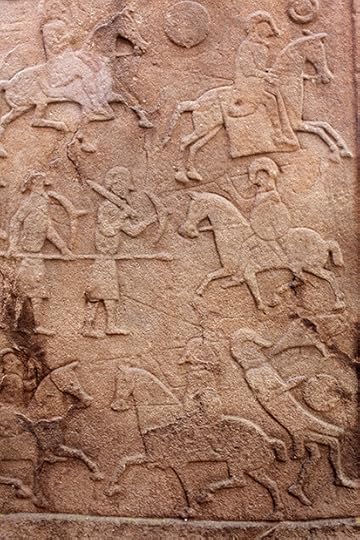

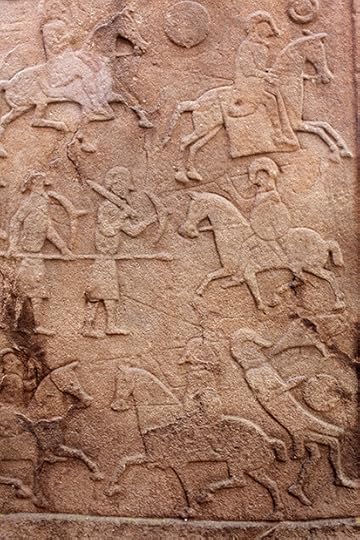

Historians have traditionally believed that this Pictish carved stone – from Aberlemno in Angus – depicts the battle of Dun Nechtain in 685, where the Picts ambushed a Northumbrian army and killed King Ecgfrith. However, many now suspect that it portrays a different conflict © SuperStock

The religious lifeSuch tensions within the church cannot have made life easy for Ecgfrith. Nor could the fact that his wife of 12 years, Æthelthryth, an East Anglian princess who was significantly older than the king, had consistently refused to consummate their marriage. Ecgfrith finally gave way and, around 672, allowed Æthelthryth to retire to the religious life. She went on to found a nunnery at Ely and took up its rule in 673.

On the face of it, a loss of a wife was a major setback. Yet it appears that Ecgfrith was able to turn this to his advantage. For, with Æthelthryth in her Ely retreat, Ecgfrith was free to marry again – and his next match, with Iurmenburh (probably a member of the Kentish royal household) helped secure him a vital alliance with the people of Kent, and greatly extended his influence in the south.

Yet where there are winners, there are inevitably losers. And in this case the losers were the Mercians, who saw their influence in the south wane as Ecgfrith’s grew and grew. Their response was to raise a great army against him in 674 – yet, once again, Ecgfrith emerged triumphant, defeating the Mercians in battle, and forcing them to cede Lindsey (broadly, Lincolnshire) and pay tribute. When the Mercian king, Wulfhere, died in 675, he was succeeded by his brother, Æthelred, who Ecgfrith had married off to his own sister – probably as part of the peace arrangements.

Ecgfrith’s victory over the Mercians marks the high-water mark of his reign. In fact, in 675, it would be no exaggeration to describe him – like his father, Oswiu, at Christmas 655 – as the high-king of Britain. Had his brother-in-law on the Mercian throne played ball, then Ecgfrith’s position might have become embedded.

Yet, unfortunately for Ecgfrith, the Mercians weren’t prepared to take the loss of Lindsey and the waning of their influence across the south lying down. In 676 they struck back, devastating Kent and effectively asserting their independence of Northumbrian overlordship. Just as significantly, they exposed Ecgfrith’s inability to protect his southern allies.

Worse still, the situation in the north was also deteriorating. The evidence is poor and often ambiguous but an alliance hostile to the high-king’s interests seems to have developed between the northern Britons on the Clyde, his cousin King Bruide of the Picts and the Irish high-king, Finsnechta Fledach, king of Brega.

A portrait of Æthelthryth, the queen who refused to consummate her marriage with Ecgfrith © Bridgeman

Such formidable opposition forced Ecgfrith to take a more conciliatory stance towards Scottish Christianity. He could no longer afford Bishop Wilfrid’s hostility towards those who had been trained within that tradition, and so he expelled Wilfrid in 678, and resisted all subsequent papal pressures to reinstate him. Ecgfrith turned instead to the Northumbrian clergy who had initially been educated and advanced within the Scottish church but had accepted Oswiu’s Catholic reformation in 664.

He also saw to it that candidates from this faction were appointed to new bishoprics. The last bishop whose appointment Ecgfrith engineered was St Cuthbert, who represented the final flowering of the tradition of preaching and asceticism established by the Scottish missionaries to Northumbria in the 630s.

Yet such moves didn’t pacify Ecgfrith’s enemies in the south. In 679, Æthelred’s Mercians marched against the Northumbrian king and defeated him in a great battle on the Trent, killing his brother, Ælfwine. Peace was restored by Theodore, archbishop of Canterbury – but not before Mercia had regained Lindsey. Ecgfrith’s high-kingship was rapidly slipping through his fingers.

The risk of further attacks by Mercia probably kept Ecgfrith close to his southern borders over the next few campaigning seasons but he successfully despatched a force to ravage the Irish territory of his opponents in 684 – the only Anglo-Saxon king ever to send forces across the Irish Sea.

Killed in battleIn 685, political upheavals among the South Saxons and then the West Saxons reduced the risk of a Mercian attack, allowing Ecgfrith to go on the offensive again, this time launching a lightning strike against the Picts. Yet this was to be his last throw of the dice for, as we’ve seen, on 20 May he was killed and ambushed by the very Picts he was trying to bring low, far to the north in the Scottish Highlands. We know very little of the battle beyond the outcome, which was a Northumbrian disaster.

In the crisis that followed, the Picts overwhelmed Fife, and even its Catholic bishop had to abandon his see. Aldfrith, an illegitimate, half-Irish brother of Ecgfrith, took the throne and continued Ecgfrith’s religious policies, but he was a middle-aged scholar and no warrior.

Aldfrith never attempted dominance of Britain either north or south of Northumbria. Instead he settled for an alliance with the West Saxons to try and contain Mercia, and made the most of his close friendships with the Irish to retain a degree of influence among the Celtic courts of the north.

Northumbria’s glory days were over, and with them any chance that a single king would attain universal superiority across Britain.

This sixth or seventh-century Anglo-Saxon gold pendant was discovered in Kent, which formed an alliance with Northumbria in the 670s © British Museum

Had Ecgfrith won his battle against the Picts, and then turned once more against the Mercians, might the pattern of history have been different? It is possible that Britain could have been welded into a single political unit under Northumbria’s kings across the late seventh and eighth centuries, but to do this they needed to secure permanent control of Mercia, so establishing a single realm from the Thames to the Firth of Forth and beyond.

They enjoyed temporary successes, but the kings never achieved this long enough for their power to take root. Instead, Northumbria’s kings often found themselves engaged on two fronts, to the north and south, and unable to deal effectively with either.

Despite this, Northumbria’s seventh-century kings were the only rulers to exercise even intermittent power universally across Britain before the 10th century, and their achievements should be recognised. Had they achieved lasting success, then the division that we see today between Scotland, England and Wales would probably be very different indeed.

High, but how mighty?How close did Ecgfrith’s fellow Northumbrian high-kings come to uniting Britain?

Æthelfrith (Ecgfrith’s paternal grandfather) should be viewed as the founder of Northumbria. He came to prominence as king of the Bernicians in northern Northumbria, c592, but expanded his rule dramatically by waging war against the neighbouring British kingdoms, and by imposing himself on Deira (basically Yorkshire). He also fought off an attack by the Scots of Dál Riata, then marched against the Welsh and won the battle of Chester around 615.

Edwin (Ecgfrith’s maternal grandfather) was king of Northumbria, 616–33. He was initially placed on the throne by East Anglian backers but from c626 onwards he was the most powerful king in Britain. He defeated the West Saxons and the Welsh and took control of Anglesey and Man. Conversion to Roman Christianity provided him with an important source of soft power, and his marriage allied him with Kent. He died in battle fighting the Welsh and Mercians.

Oswald (Ecgfrith’s paternal uncle) was king of Northumbria, c634/35–42. He was Æthelfrith’s son, obtaining power through victory over the Welsh king Cædwalla. A marriage alliance with Wessex stabilised his ‘over-kingship’ in the south, while disastrous defeat suffered by the Scots in Ireland probably allowed Oswald to extend his high-kingship across the north and take direct control of the Lothians. He was defeated and killed “treacherously” by the Mercians.

Oswiu (Ecgfrith’s father) was king of Bernicia from 642 and of all Northumbria from 655–70. He used his patronage of Scottish Christianity to expand his influence into the south-east Midlands and Essex but had to retreat right up to the Firth of Forth in 655 in the face of a massive Mercian-led invasion. The invaders were defeated and mostly slain on the river Went near Doncaster in late autumn as they returned home, allowing Oswiu to emerge as high-king of Britain.

Although his attempt to take over Mercia ultimately failed, Oswiu did expand Northumbria northwards into Fife and established his over-lordship across the north.

Nick Higham is professor emeritus at the University of Manchester. He is co-author (with Martin Ryan) of The Anglo-Saxon World (Yale, 2013).

Further reading

Ecgfrith: High-king of Britain by Nick Higham (Sean Tyas, forthcoming 2015)

Listen again

To listen to a series of portraits of 30 ground-breaking Anglo-Saxon men and women, which appeared on Radio 3’s The Essay.

An illustration from Bede’s The Life of St Cuthbert shows Ecgfrith visiting St Cuthbert at Lindisfarne. © AKG Images

An illustration from Bede’s The Life of St Cuthbert shows Ecgfrith visiting St Cuthbert at Lindisfarne. © AKG Images On Saturday 20 May AD 685, St Cuthbert was with Iurmenburh, Northumbria’s queen, at Carlisle, when he had a vision of Iurmenburh’s husband, Ecgfrith, dying at the hands of the Picts. A few days later, “they heard that it was announced far and wide that a wretched and lamentable battle had taken place at the very day and hour it was revealed to him”.

Ecgfrith was dead, and the flower of his army had fallen. For Northumbria, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that spanned much of what is now northern England and south-east Scotland, it was a fateful day. Bede, the English monk and author, later quoted from Virgil’s Aeneid: “The hope and valour of the realm of the English began ‘to ebb and flow away’.”

The Picts recovered lands previously taken from them and the Scots and northern Britons threw off English overlordship. The Northumbrians’ dream of exercising power across all of Britain was finally extinguished.

In the sixth and seventh centuries, Britain was a world of small kingships. Minor rulers found it necessary to look to more powerful kings for protection. The resulting regional kingships could be volatile and short-term but – thanks to a combination of dynastic alliances, Christian missions, raids and wars, sometimes pursued over considerable distances – a pattern of larger kingdoms slowly emerged, absorbing smaller neighbours.

Occasionally, in the seventh century, the most successful rulers established a Britain-wide, ‘over-’ or ‘high-kingship’ – by which every local or regional king in the whole island recognised the superiority of just one man. It was this supreme power that Ecgfrith lost his life trying to attain in 685.

Imperial ruleOf course, the idea of an overall authority across Britain (attempted, if not realised) stems ultimately from the ancient Romans, whose emperors were later understood locally as high-kings ruling over British kings.

This notion of a high-kingship was developed by Bede, who employed the word imperium in reference to both Roman and English supremacies.

Bede listed seven kings who had imperium south of the Humber, the last three of which were Northumbrians – Edwin, Oswald and Oswiu – whose power was centred further north. These, Bede tells us, had greater power: Edwin achieved authority over Anglesey and Man; Oswald ruled “within the same bounds” in this list, but Bede later claimed for him authority over all peoples speaking English, Welsh, Scottish and Pictish.

Finally, Oswiu additionally “overwhelmed and made tributary the greater part of the peoples of the Picts and Scots who inhabit the northern limits of Britain”. We can certainly see Oswiu as all-powerful in the years after 655, when he defeated the Mercians and took over much of the English Midlands and Fife in Scotland, becoming overlord of the northern kings beyond.

Bede visualised a progression, therefore, from ‘over-kingship’ of the south to a Northumbrian ‘high-kingship’ of all Britain. The subordination of all the other peoples of Britain to the (Northumbrian) English was, in Bede’s view, God’s plan for the island.

The one high-king who Bede omitted from this list was Ecgfrith, Oswiu’s son and heir, and a king who has not perhaps received as much attention as he deserves. He came to the throne of the Northumbrians, aged about 25, following his father’s death in 670.

An almost immediate challenge came from his father’s erstwhile northern tributaries, for the Picts rose against him, seeking to throw off English overlordship and recapture the Pictish territory that Oswiu had taken under Northumbrian rule. Ecgfrith may have been new to the throne but he was more than equal to the Picts’ challenge. He marched north and won an overwhelming victory against them, reimposing tribute, confirming his hold on Fife and instigating regime change.

At home, though, Ecgfrith was experiencing serious difficulties. At the root of his problems was a split in the Northumbrian church. On one side were the majority of the clergy, who had been trained within the Scottish tradition (centred on Lindisfarne, Melrose and Whitby), but had conformed to the Roman dating of Easter in 664.

On the other side of the divide was Bishop Wilfrid, who had adopted the continental view that British and Scottish churches were heretical, and was now moving energetically against British priests within Northumbria, expelling them by force of arms.

Historians have traditionally believed that this Pictish carved stone – from Aberlemno in Angus – depicts the battle of Dun Nechtain in 685, where the Picts ambushed a Northumbrian army and killed King Ecgfrith. However, many now suspect that it portrays a different conflict © SuperStock

The religious lifeSuch tensions within the church cannot have made life easy for Ecgfrith. Nor could the fact that his wife of 12 years, Æthelthryth, an East Anglian princess who was significantly older than the king, had consistently refused to consummate their marriage. Ecgfrith finally gave way and, around 672, allowed Æthelthryth to retire to the religious life. She went on to found a nunnery at Ely and took up its rule in 673.

On the face of it, a loss of a wife was a major setback. Yet it appears that Ecgfrith was able to turn this to his advantage. For, with Æthelthryth in her Ely retreat, Ecgfrith was free to marry again – and his next match, with Iurmenburh (probably a member of the Kentish royal household) helped secure him a vital alliance with the people of Kent, and greatly extended his influence in the south.

Yet where there are winners, there are inevitably losers. And in this case the losers were the Mercians, who saw their influence in the south wane as Ecgfrith’s grew and grew. Their response was to raise a great army against him in 674 – yet, once again, Ecgfrith emerged triumphant, defeating the Mercians in battle, and forcing them to cede Lindsey (broadly, Lincolnshire) and pay tribute. When the Mercian king, Wulfhere, died in 675, he was succeeded by his brother, Æthelred, who Ecgfrith had married off to his own sister – probably as part of the peace arrangements.

Ecgfrith’s victory over the Mercians marks the high-water mark of his reign. In fact, in 675, it would be no exaggeration to describe him – like his father, Oswiu, at Christmas 655 – as the high-king of Britain. Had his brother-in-law on the Mercian throne played ball, then Ecgfrith’s position might have become embedded.

Yet, unfortunately for Ecgfrith, the Mercians weren’t prepared to take the loss of Lindsey and the waning of their influence across the south lying down. In 676 they struck back, devastating Kent and effectively asserting their independence of Northumbrian overlordship. Just as significantly, they exposed Ecgfrith’s inability to protect his southern allies.

Worse still, the situation in the north was also deteriorating. The evidence is poor and often ambiguous but an alliance hostile to the high-king’s interests seems to have developed between the northern Britons on the Clyde, his cousin King Bruide of the Picts and the Irish high-king, Finsnechta Fledach, king of Brega.

A portrait of Æthelthryth, the queen who refused to consummate her marriage with Ecgfrith © Bridgeman

Such formidable opposition forced Ecgfrith to take a more conciliatory stance towards Scottish Christianity. He could no longer afford Bishop Wilfrid’s hostility towards those who had been trained within that tradition, and so he expelled Wilfrid in 678, and resisted all subsequent papal pressures to reinstate him. Ecgfrith turned instead to the Northumbrian clergy who had initially been educated and advanced within the Scottish church but had accepted Oswiu’s Catholic reformation in 664.

He also saw to it that candidates from this faction were appointed to new bishoprics. The last bishop whose appointment Ecgfrith engineered was St Cuthbert, who represented the final flowering of the tradition of preaching and asceticism established by the Scottish missionaries to Northumbria in the 630s.

Yet such moves didn’t pacify Ecgfrith’s enemies in the south. In 679, Æthelred’s Mercians marched against the Northumbrian king and defeated him in a great battle on the Trent, killing his brother, Ælfwine. Peace was restored by Theodore, archbishop of Canterbury – but not before Mercia had regained Lindsey. Ecgfrith’s high-kingship was rapidly slipping through his fingers.

The risk of further attacks by Mercia probably kept Ecgfrith close to his southern borders over the next few campaigning seasons but he successfully despatched a force to ravage the Irish territory of his opponents in 684 – the only Anglo-Saxon king ever to send forces across the Irish Sea.

Killed in battleIn 685, political upheavals among the South Saxons and then the West Saxons reduced the risk of a Mercian attack, allowing Ecgfrith to go on the offensive again, this time launching a lightning strike against the Picts. Yet this was to be his last throw of the dice for, as we’ve seen, on 20 May he was killed and ambushed by the very Picts he was trying to bring low, far to the north in the Scottish Highlands. We know very little of the battle beyond the outcome, which was a Northumbrian disaster.

In the crisis that followed, the Picts overwhelmed Fife, and even its Catholic bishop had to abandon his see. Aldfrith, an illegitimate, half-Irish brother of Ecgfrith, took the throne and continued Ecgfrith’s religious policies, but he was a middle-aged scholar and no warrior.

Aldfrith never attempted dominance of Britain either north or south of Northumbria. Instead he settled for an alliance with the West Saxons to try and contain Mercia, and made the most of his close friendships with the Irish to retain a degree of influence among the Celtic courts of the north.

Northumbria’s glory days were over, and with them any chance that a single king would attain universal superiority across Britain.

This sixth or seventh-century Anglo-Saxon gold pendant was discovered in Kent, which formed an alliance with Northumbria in the 670s © British Museum

Had Ecgfrith won his battle against the Picts, and then turned once more against the Mercians, might the pattern of history have been different? It is possible that Britain could have been welded into a single political unit under Northumbria’s kings across the late seventh and eighth centuries, but to do this they needed to secure permanent control of Mercia, so establishing a single realm from the Thames to the Firth of Forth and beyond.

They enjoyed temporary successes, but the kings never achieved this long enough for their power to take root. Instead, Northumbria’s kings often found themselves engaged on two fronts, to the north and south, and unable to deal effectively with either.

Despite this, Northumbria’s seventh-century kings were the only rulers to exercise even intermittent power universally across Britain before the 10th century, and their achievements should be recognised. Had they achieved lasting success, then the division that we see today between Scotland, England and Wales would probably be very different indeed.

High, but how mighty?How close did Ecgfrith’s fellow Northumbrian high-kings come to uniting Britain?

Æthelfrith (Ecgfrith’s paternal grandfather) should be viewed as the founder of Northumbria. He came to prominence as king of the Bernicians in northern Northumbria, c592, but expanded his rule dramatically by waging war against the neighbouring British kingdoms, and by imposing himself on Deira (basically Yorkshire). He also fought off an attack by the Scots of Dál Riata, then marched against the Welsh and won the battle of Chester around 615.

Edwin (Ecgfrith’s maternal grandfather) was king of Northumbria, 616–33. He was initially placed on the throne by East Anglian backers but from c626 onwards he was the most powerful king in Britain. He defeated the West Saxons and the Welsh and took control of Anglesey and Man. Conversion to Roman Christianity provided him with an important source of soft power, and his marriage allied him with Kent. He died in battle fighting the Welsh and Mercians.

Oswald (Ecgfrith’s paternal uncle) was king of Northumbria, c634/35–42. He was Æthelfrith’s son, obtaining power through victory over the Welsh king Cædwalla. A marriage alliance with Wessex stabilised his ‘over-kingship’ in the south, while disastrous defeat suffered by the Scots in Ireland probably allowed Oswald to extend his high-kingship across the north and take direct control of the Lothians. He was defeated and killed “treacherously” by the Mercians.

Oswiu (Ecgfrith’s father) was king of Bernicia from 642 and of all Northumbria from 655–70. He used his patronage of Scottish Christianity to expand his influence into the south-east Midlands and Essex but had to retreat right up to the Firth of Forth in 655 in the face of a massive Mercian-led invasion. The invaders were defeated and mostly slain on the river Went near Doncaster in late autumn as they returned home, allowing Oswiu to emerge as high-king of Britain.

Although his attempt to take over Mercia ultimately failed, Oswiu did expand Northumbria northwards into Fife and established his over-lordship across the north.

Nick Higham is professor emeritus at the University of Manchester. He is co-author (with Martin Ryan) of The Anglo-Saxon World (Yale, 2013).

Further reading

Ecgfrith: High-king of Britain by Nick Higham (Sean Tyas, forthcoming 2015)

Listen again

To listen to a series of portraits of 30 ground-breaking Anglo-Saxon men and women, which appeared on Radio 3’s The Essay.

Published on October 24, 2015 03:00