Bert Carson's Blog, page 4

December 28, 2011

Ever Wonder Why

A couple of months ago, October 22nd

to be exact, I listened to part of the Prairie Home Companion radio show. The part I heard included a short

conversation with Steve Wariner, who

I had never heard of until then. Garrison

Keillor described him as a “guitar heavy.” Later I heard Steve sing and play, and I have

to agree with Garrison.

Steve has been in the music business since

he was 17, starting in 1973 as a bass player with the Dottie West Band. Four years later he was hired by Chet Atkins

as a bass player. He told a story from his

days with Chet that stuck with me; first because it’s funny, and second because

there is a real lesson for me, and maybe for you, in it.

Steve’s story goes like this. During a show with Chet Atkins, while a

singer was performing, and Steve, Chet, and the rest of the band was playing,

Chet moved slowly across the stage until he was standing beside Steve. Without pausing or even looking at Steve,

Chet whispered, “Has anyone ever told you that you’re a great bass player?”

Steve, feeling a bit flattered, still

playing, whispered back, “No, no one ever has.”

To which Chet replied, “Do you ever wonder

why?”

*********

I've thought about that story so much I’ve

created the scene in my mind; and every time I let it play in my head, I laugh.

And every time I laugh, I ask myself, Has anyone ever told you that you’re a great

writer?

To which I reply, No, no one ever has.

And

then I hear another voice ask, Do you

ever wonder why?

Well

the truth is, I don’t wonder why, I know why and I’m doing something about it.

**********

Do

you ever wonder why?

December 26, 2011

6 Million New Kindles

Six million new Kindle owners! That’s the number that’s being kicked around

these days. Wow!

Now, I know that many of the “new owners” are like me. They really aren’t “new,” they have simply

added to their collection of Kindles or upgraded. I dreamed of a Kindle with a color screen

from the first day I owned a Kindle, and now I have a Kindle Fire. Of course my Kindle Keyboard is never far

away. If you are in that group of Kindle

owners, I’m not going to tell you anything new.

This blog is for the REAL new Kindle owner - the Kindle

owner who is finally powering up that long-awaited first Kindle. A first Kindle is like a first car. You have a choice. You can power up and drive it into a ditch,

or you can learn something about it and have it serve you for a long time. Choices, choices, choices.

I’m not going to discuss all the things your Kindle can

do. I’m going to talk about your Kindle

and your books. What were you reading

before your new Kindle moved into your life?

Like most of us, you probably were reading the best sellers – like John

Grisham’s latest, The Litigators – It’s

waiting for you at Amazon, along with thousands of other best sellers.

Maybe, like me, you love nonfiction best sellers. I often listen to Bob Edward’s Radio, hear an

author interviewed and know that I have to have it. In the past couple of weeks I discovered Grant’s

Final Victory by Charles Bracelen Flood, and God’s Secretaries by Adam

Nicolson, just that way. Before the

interviews ended, the books were in my Kindle library.

If you are new to Kindle, there is another book world for

you to explore; the world of Indie Writers.

Writers like Christina Carson, my wife, who just published her second

book, Dying to Know, the story of a woman faced with a clock stopping

medical choice. Or books by Kathy Lynn Hall,

Russell Blake, K.C. Hilton, Frederick Brooke, JH Sked, Ni'cola Mitchell… and

thousands, maybe even hundreds of thousands, of other independent authors.

If I’m lucky, you might even find me, and read about a 44

year old who becomes the starting quarterback for the University of Montana, or

a couple of dogs and a time traveler who connect a group of Vietnam veterans,

or three Vietnam Vets who own a commercial private investigation company called

Southern

Investigation.

So, is there some advice here for you? Some thought that might keep you and your

Kindle out of e-ditches? Yep, I do have a

suggestion – before you buy any Kindle book that you aren’t familiar with, download

the sample. Only you know what

you enjoy reading. Don’t gamble, read

the sample.

Have fun with your new Kindle. I bet you’ll enjoy it more every day.

Happy reading in 2012.

PS – the Indie Writers mentioned are all Twitter friends –

follow them, they are fun:

Christina Carson @carsoncanada

Kathy Lynn Hall @RedMojoMama

Russell Blake @BlakeBooks

K.C. Hilton @kchilton1

Fredericke Brooke @frederickbrooke

J.H. Sked @JHSked

Ni’cola Mitchell - @MsNicola

Me - @bertcarson

December 24, 2011

Christmas Eve Magic

It was Tuesday, September 8, 1948, and I was a half-step

away from losing all the magic that was left in my young life. Thirteen months earlier, with the arrival

of my brother, I’d ceased being an only child and become simply the older of

two boys. Nine months later, with my new

status almost handled, I began my schoolboy years. I knew I was in trouble when my mother abandoned

me in a room full of dungaree smelling kids who stared at me like I was a new

guppy in the piranha tank.

I hated school, and I still get goose bumps when I think of

all the miserable things that happened to me there; not the least of which

occurred that first day on the playground. In an effort to bring a bit of magic into

that miserable place, I confided to a few older boys that Santa Claus would be

stopping by my house very soon.

Today, sixty-three years later, I don’t have to close my

eyes to recall that moment. It’s still

etched in the front of my brain. In

perfect sync, they laughed like they had rehearsed it for months. I don’t mean giggled. They rolled.

Finally, the leader managed to say, “There is no Santa Claus. Santa Claus is for babies. You’re way too old to believe in Santa Claus.”

A baby brother, school, and now no Santa; it was too

much. I was sitting on the front steps

when my Daddy came home from work. He

took one look at me and postponed whatever he had intended to do. He sat down beside me. For a while we just stared at the cars going

up and down Second Avenue. Finally he

said, “How was school, Son?”

I didn’t pull any punches.

“It was really bad, Daddy. I didn’t

know anybody, and I didn’t learn anything; and I don’t want to go back.”

He thought about that for a while and then said, “What else

happened?”

It took a while for me to get it out between sobs. I grabbed the words and flung them out. “The big kids said there is no Santa Claus.”

He was quiet for a long time. He put his arm around my shoulders, looked

right in my eyes, and said, “That’s really the problem, isn’t it?”

I didn’t hesitate, “I guess it is.”

I can still see the smile that spread across his face as he

said, “I think I can do something about that son. Yep, I think I can.” He paused, looked through my eyes and right

into my heart, and then said, “This has to be our secret, OK?”

I couldn’t talk, but I managed to say, “Yes, Sir.”

“Good. Now, here’s

what I’m going to do. When you go to bed

on Christmas Eve, I’m going to wait for Santa.

When he comes into the kitchen for the coffee and cake you’ve left for

him, I’m going to ask him if he will take a minute to talk to you.”

It took a while for me to answer. When I could manage it, I said, “Do you think

he will?”

In a powerful voice I’d never heard before, he said, “I’m

not going to let him leave until he does.”

It was tough, but I kept our secret. When he finally tucked me in on Christmas

Eve, Daddy put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Don’t worry, Son. This is going to work.”

I don’t know how I managed to go to sleep or how long I’d

been sleeping when someone shook me gently.

My eyes snapped open, and I saw Daddy standing beside my bed. I felt a wave of disappointment begin to

sweep over me. It died when Daddy smiled

and whispered, “He’s here.”

Then the door swung wide open, and Santa walked into my bedroom. He sat down beside my bed, smiled, took a sip

of the coffee I’d left for him, and said, “I’m not supposed to do this, but

your Daddy said I couldn’t go until I talked to you; so here I am.”

He took another sip of coffee, touched my head and said, “No

matter what you hear about me, now you know the truth. Don’t ever forget. OK?”

I could only nod. He

stood, turned back toward me, bent low, and whispered, “Merry Christmas,” in my

ear, and then he and Daddy slipped from my room.

A few minutes later, Daddy returned and without a word sat

in chair that only a moment before Santa had used. We both laughed when the sound of sleigh

bells suddenly filled the room, then Daddy whispered, “Merry Christmas, Son.”

Santa locked the magic in my heart that night and it has

never left… it never will, may it never leave your heart either.

Merry Christmas

November 1, 2011

Take Off Speed

[image error]

I’ve always wanted to fly.

After sixteen months in Vietnam, where I spent a lot of crew time on

board helicopters, my desire to fly was stronger than ever. I went to Napier Field, in Dothan, Alabama,

found Steve Winters, an instructor at the Cessna dealership, and signed

up. Fourteen dual instruction hours

later, I soloed.

In the next few months, I accumulated a lot of hours, but

for a lot of reasons I didn’t take the private pilot written examination and

test flight. I didn’t fly again for

almost seventeen years. When I had money,

I didn’t have time; when I had time I didn’t have money. Then I moved to Mentone, Alabama where I had

both time and money. I went to Isbell

Field, in Fort Payne, Alabama. There I

met Waylon Lyons, the Fixed Base Operator at the airport and the owner of Lyons

Aviation.

Waylon, an old Army Aviator, had over 30,000 accident free

hours of flying in almost every type of aircraft. He had a twinkle in his eyes and a sense of

humor to go with it. He also had a

handlebar mustache and deep wrinkles around his eyes, no doubt the result of

laughing a lot and staring into the sun through countless airplane windscreens.

I told him what I wanted and sheepishly handed him my old

log book. He flipped through it, looked

at me, laughed, and said, “You have some catching up to do.” I’m not quite sure how it happened but within

minutes, I was strapped in the seat, the pilot’s seat, of a red and white Cessna

152. As we taxied toward the runway,

Waylon began my instruction. “Follow me

on the controls to get the feel again.” I

put my hand lightly on the yoke and my feet on the rudder pedals. “Easy,” he cautioned. I won’t get it in the air if I have to carry

you.” He laughed and continued his

dialogue.

Ten feet from the runway he stopped, checked the

instruments, took the microphone off its hook on the dash, keyed it and said, “All

traffic in the Fort Payne area, Cessna 26 Whiskey is departing on runway 4.” With that said, he listened to the silent

radio speakers for a few seconds, looked to the east, then the west, then released

the brakes, moved onto the runway, turned smoothly toward the west, lined up

with the center strip and gave the little plane full power. Seconds later, I was flying again.

We flew an hour that day, two hours the following day, and

on the third day, we had flown an hour of what was to be a two hour lesson when

Waylon said, “Go back to the airport and do a touch and go.” I complied, executing the landing and

takeoff. As we climbed away from the

airport he said, “Get back in the pattern, land, and taxi to the office.”

As I approached the office he said, “Turn back to the

runway, stop, and let me out.” I couldn’t

believe it. After seventeen years away

from flying, and with only three hours of instruction, Waylon was about to send

me up alone. I stopped the plane; Waylon

opened his door, unbuckled his belt, and swung his right leg out of the

plane. I grabbed his shoulder, and

shouting to be heard above the noise of the engine, called out, “Wait, I don’t

know the take-off speed of the plane.”

He stopped his exit movement but didn’t answer. He just sat there staring out the side

window.

A few seconds passed and I shouted again, “Waylon, I don’t

know the take-off speed.”

He turned toward me, grinned, and said, “I heard you the

first time, and I’m thinking about it. I

don’t know the take-off speed either, but I do know this, all you have to do is

taxi to the runway, let the traffic in the area know you’re leaving, turn onto

the runway, line up with the center strip, give the plane full power, and put

some back pressure on the yoke. When it’s

ready to fly, the plane will take off.”

Two minutes later I was flying.

That day, I learned about take-off speed and

since then I’ve learned that it applies to everything I do. All I have to do is set my intention, apply

full power, pull back a bit on the controls, and when I’ve reached take-off

speed, I will fly; so will you.

Note - the plane in the photo is a 1946 Champ - I'm a 1942 Redneck

September 22, 2011

Carrying a water buffalo

For sixteen months, I served in Vietnam as a U.S. Army

For sixteen months, I served in Vietnam as a U.S. Army

Platoon Sergeant, Battalion Personnel Section Supervisor, and part-time

helicopter door gunner and sometimes crew chief. I volunteered for Vietnam, extended my

service obligation (see Vacation Bible School) to go, and pulled a few strings

to make sure I would be assigned to a helicopter unit, specifically, the 214th

Combat Aviation Battalion.

Since the battalion flew 24/7, regular crewmembers always

needed time off, so there was no problem for a volunteer to get crewmember

flying time. I became such a regular that

a Special Order was cut authorizing my off duty flying, which meant when I’d

logged sufficient hours, I was awarded an Aircraft Crewmembers Badge, even

though I wasn’t school trained for the job. I still have a copy of the special order and

read it occasionally to remind myself that being weird isn’t a new thing for

me.

With the exception of one mission, all of my flying was on a

slick, a Huey rigged to transport men and sometimes supplies. This post is about that one mission and the

lesson I learned from it.

The mission began, as they all did, with a call from the

First Sergeant of one of our companies, asking if I could fly a mission as crew

chief. The difference between this call

and previous requests was that the caller was the First Sergeant of the 200th

Assault Support Helicopter Company, the Pachyderms, our only non-Huey

company. The 200th flew Chinooks, the Army’s

twin rotor; transport helicopter that is capable of carrying 40 fully equipped infantrymen

or a whole lot of equipment.

I told the First Sergeant that I had never been on a Chinook,

and I certainly wasn’t qualified to be the crew chief on a mission. I suggested that he use me as the door gunner. He said, “No, that won’t work, Carson. My company clerk, who is an E-4 and also non-experienced,

is going to gun. You’re an E-5, so you

out rank him. You have to be the crew

chief.”

He paused, and I considered the wisdom of crewing a Chinook

with two inexperienced crewmen. Before I

could voice my concern, he said, “Hell, don’t worry about it Carson. It’s a milk run. Nothing is going to happen. Be on the flight line at 0600 hours.”

That was good enough for me.

I told him, I would be there. I cleared

it with Lt. Vought, my commanding officer, and the next morning I was on the Pachyderm’s

flight line at 6 AM. The First Sergeant

made a quick round of introductions. I sized

up the Aircraft Commander, the copilot, and the Company Clerk/door gunner and determined

there was very little Chinook experience in the entire group.

If the First Sergeant had any misgivings about the experience

of the crew, he didn’t show them. After

the introductions, he said, “Gentlemen, today you’re going to help the Chaplain

who is behind in his quota of Pacification Program Projects. You’re going to fly a farmer and his water

buffalo from here to a small hamlet fifteen miles south of us.”

Before we could ask any questions, he said, “The farmer and

the buffalo will be here anytime. Have

fun, and I’ll see you later.” He quickly

turned and walked away leaving us to ponder the mission. We pondered for almost an hour and were on

the point of scrubbing the mission, when I saw our passengers approaching. As they drew closer, I realized that a water

buffalo is a lot bigger than I’d originally thought.

I’d never seen one up close until that moment. I’m 6’2”, and my eyes were at the level of

his shoulders. A few feet from us, the

farmer said something to the water buffalo that I couldn’t understand, but

obviously he did, because he stopped walking and stood motionless, waiting for

the next command. Then the farmer said

something to me that I couldn’t understand.

I turned to the Aircraft Commander, who shrugged, and said, “Sergeant,

you’re the crew chief, how are we going to carry the animal?”

The correct answer was to rig a sling around the water

buffalo and carry him beneath the Chinook.

However, the Pathfinders, who were responsible for rigging loads, had

left thirty minutes earlier as part of a “real mission.” I looked at the water buffalo, considered the

options, and said, “He seems pretty tame, Sir.

Let’s carry him inside.”

The AC said, “OK, get him on and secured, so we can get the

show on the road.” He and the copilot

went into the Chinook. I pointed to the

water buffalo and indicated to the farmer that he should bring him inside. I turned toward the Chinook as the farmer

spoke to the animal. The Company Clerk

called out, “They’re following you, Sarge.

This is going to work out.”

I put my right hand to my chest, crossed my fingers, and

answered. “Yep, it will be a piece of

cake.” For a while, it looked like I was

correct in my prediction. I pointed to

spot on the floor that I judged to be the center of gravity for water buffalo,

and indicated to the farmer that the water buffalo should lie down there. He turned to the animal, said something, and

the huge animal lay down in the designated spot. In short order, we secured him to the D-rings

in the floor with one inch wide nylon tie down straps. To be on the safe side, we used four of them.

When I was sure he was secure, I raised the ramp and spoke

into the intercom, “Sir, we are ready back here.” Fifteen minutes later, we were half way to

our destination, flying at 2,500 feet over rice paddies that stretched in every

direction as far as I could see. I

turned from the window and looked into the water buffalo’s eyes. He shook his massive head, heaved against the

tie down straps, and stood up. I don’t

mean he tried to stand up and the straps held him. I mean he stood up, sending pieces of nylon

strap over the cargo area.

Once upright, he stood motionless for a long time in spite

of the frantic commands of the farmer.

Then he looked at me, raised his right front leg, and stomped as hard as

he could. The floor of a Chinook is made

of aluminum, light-weight aluminum that is no match for a water buffalo. His hoof went through it like it was made of

cardboard, leaving a six inch hole. That

must have felt good to him because he immediately stomped another hoof and then

another and before you could say, “Aw Hell!,” I had a bunch of holes in the

floor of the helicopter that was flying a half mile above the earth.

Though I didn’t know much about Chinooks, I did know that

their controls were hydraulic and the hydraulic lines were under the

floor. I suddenly had a vision of what

was going to happen if the buffalo broke one of the lines. My vision was interrupted by the Aircraft

Commander’s shout in my intercom, “Sergeant, what the hell is going on back

there?”

I looked at the water buffalo and the holes in the floor and

said, “Sir, it appears that the water buffalo is ready to get off. NOW! And, if you want to see tomorrow, I

suggest you land immediately and let us unload him.” The AC got the picture and immediately executed

the maneuver known as autorotation. That

simply means he cut power back to dead idle, pointed the ship toward the

ground, and we began descending like a large boulder dropped from an

airplane.

Just before we reached the ground, I ran to the window to

check our landing spot. I couldn’t

believe what I saw. We were about to

settle into a rice paddy that was the center of a firefight. A group of ten or fifteen Viet Cong, tucked

in behind the dyke on the north side of the paddy, were firing at what I

guessed to be a squad of 9th Division infantrymen. It was too late to power up and move to a

more suitable rice paddy. The AC flared

the Chinook, and we settled into about a foot of black water and rice

plants. I lowered the ramp. The water buffalo and the farmer left. I raised the ramp as the Company Clerk

screamed into the intercom, “We’re clear.

LET’S GO!”

As we hauled out of the rice paddy, I stepped to the window

on the south side of the Chinook and looked down. The 9th Division troops, ten,

maybe twelve strong, were lying on their stomachs, weapons forgotten in their

hands, staring as we left the ground. I

quickly moved to the opposite side, looked down at the Viet Cong, and saw that

they too were staring opened mouthed.

In thirty minutes, we were back at Camp Bearcat, our home

base, where the AC and the copilot began explaining to the Officer of the Day

what had happened. Walking back toward

Headquarters Company, I thought about the looks on the faces of the VC and the

9th Division troops and recalled that all the time we were on the

ground in the middle of what had been a hot firefight, not a single shot was

fired. Even as we pulled out, a

defenseless target, no one fired, not even a single round.

For years, I thought about that mission, and then one day a

light went on in my head, and I got it. Four

American’s and a Vietnamese farmer focused all of their energy on one objective

– get the water buffalo off of the Chinook – and the power of our focus stopped

a firefight and saved our lives. As I

thought about that I realized that we create everything in our lives with our

focus, everything. There are no

exceptions.

Now, you’re probably thinking of all the things you’ve

experienced that you didn’t want to happen in your life that did. I invite you to look at those things again. It doesn’t matter whether we want to manifest

the object of our focus or not. All that

matters is the power we give it. Simply

stated, what we focus on we create. What

we focus on with all of our power we create quicker, in some cases instantaneously. That day in Vietnam, five men were

unwavering in their focus and manifested an improbable objective.

When we take conscious control of our focus and hold it in

place, in spite of appearances, the magic of creation comes into play. That’s

the power of conscious living. And, you

don’t need an irate water buffalo, or any other traumatic situation to prove that

power in your life.

September 12, 2011

My Twitter Family

Last Friday I celebrated my 69th birthday working

Last Friday I celebrated my 69th birthday working

my day job, along with my wife @carsoncanada and

our partner, Adrienne Wall @adrienne_wall. Adrienne takes photos of children, and

Christina and I sell them. It’s not

quite that simple, but it’s not much more complicated either. We are a three person company; no contract

photographers or sales reps. That means

we do everything and some weeks everything amounts to a lot. Last week was one of those. From Tuesday afternoon until a few minutes ago

(it’s now almost midnight Sunday), all I did was the day job. That means I didn’t write, I didn’t run, and

worst of all I didn’t spend any time with my Twitter Family.

Three months ago, I hardly knew what Twitter was. I opened an account last winter, but until

mid-June I didn’t use it. Then John

Locke wrote a book explaining how he sold a million eBooks. I read the book, and in case you haven’t, the

primary way John sold all the books was by building a huge following on Twitter. His followers not only bought his books, they

invited their friends to buy them.

The day after I finished John’s book I started Tweeting and

following like a mad man. Today, I have over

2,200 people following me, and I’m following more than 2,400. My book sales aren’t much more than they

were before I became active on Twitter, but something far more profound has occurred. I now have a family that cares about me much

like my platoon in Vietnam cared about me.

Here are a few stories to give you an idea what I’m talking

about: Christina and I talk about J.H.

Sked @JHSked like he is a good friend, because he is. J.H. is a writer and painter and lives in

London. Almost every day I talk to Kathy

Hall, @redmojomama and Joyce Faulkner @joycefaulkner, wonderful

writers who live in California and Pittsburg respectively. Dannie Hill and I have a lot in common –

Vietnam and a love for all things Asian.

Dannie @danniec_hill lives in Thailand. My buddy Will Bevis @WillBevis lives about forty miles from Huntsville, but we

met on Twitter, and so far that’s the only place we rendezvous. Claude Nougat @claudenougat and Emma Calin @emmacalin are good friends who never fail to encourage and

inspire. Claude lives in Italy, Emma in

France.

I wrote a blog about Black Women and my good friend Ni’Cola

Mitchell @msnicola of Las Vegas loved it and retweeted to her

followers (almost 19,000 strong today).

My racist cousin hated the blog, so I unfriended him on Facebook. Guess who I consider a member of my true

family?

Uta Burke @katzbrui lives,

works, writes, and blogs from New Jersey – she is a friend of mine. I spend a bit of time on Goodreads. In the beginning I could barely sign in –

thanks to a lot of help from my friend, KC. Hilton @kchilton1, from Kentucky, I

made it through the Goodreads initial learning curve but more importan, KC and

I are now good friends.

Jason Matthews @jason_matthews wrote

one of the first eBook marketing guides that I’ve read. And wonder of wonders, he is now a

friend. When I have a question, he

answers. Jason lives in California; I

live in Alabama.

Twitter has made it possible for me to have an international

family that I love more than you can imagine.

Arleen Boyd @alohaarleen has

92,000 followers yet she found the time to recommend the movie, The Spitfire

Grill and then told me I could find it on Netflix. Renee Pawlish @reneepawlish is a student of social media and shares every new

and exciting thing she discovers. Ryan

and Taliya Schneider @taliyaschneider and

@ryanlschneider are loyal friends who just happen to be smart and

funny, and I know I can count on them.

Michael Hicks @kreelanwarrior just

quit his day job to be a full time writer.

In spite of all the changes he’s going through I know that if I tweet

him with a question, I’ll have an answer as soon as he can get his hands on a

keyboard.

I know without looking over my shoulder that Fredrick Brooke

@frederickbrooke of Switzerland has my back, and anytime I want to

remember the truth of things Russell Blake @blakebooks, sitting under a palm tree in Mexico, will be

quick to oblige. Mrs. Thomas, my high

school English teacher meant a lot to me but not nearly as much as John Geddes @johnjgeddes of Ontario, a retired English teacher, amazing

writer, and my good friend.

And there is Bill Breckenridge and Rhumtetum @Rhumtetum,

one of the greatest cats in the world.

Bill and Rhumtetum live in Scotland and share their wisdom with me and

quite a few other lucky souls on the planet.

When I want a laugh, a good old fashioned belly laugh, I tweet Valerie

Thornburn @vallethor also of Scotland, a great Elvis fan and all

around funny person and/or our mutual friend Eric Miller @SpitToonsSaloon who lives in Philadelphia, and even though I

suspect he’s a Philly fan, I don’t hold that against him.

I could go on and on and still not mention everyone who is

part of my new family, but I have an idea that you get the message. Besides, Richard Bach has already said what I’m

feeling in his book, Illusions –

The bond that links your true family is not one of blood, but of

respect and joy in each other's life. Rarely do members of one family grow up

under the same roof.

September 3, 2011

Vacation Bible School

For this post to make sense there are a couple of things you

For this post to make sense there are a couple of things you

should know before you begin reading:

The first is, history pinpoints the Vietnam War as beginning

November 1, 1955 and ending with the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. What history doesn’t record is that the

United States almost lost the war on Jan 31, 1968, seven years before it

finally ended. That was the first day of

the Vietnamese New Year celebration that, in the U.S., is simply called Tet. In my opinion, Saigon would have fallen that

day if the VC and NVA had been better supplied.

In addition, if a stray unit of the 11th Armored Cav (Black Horse

Regiment), had not just happened to roll into Long Binh, a major U.S. Command

Center, at the height of the siege there, both the command center and Bien Hoa

Airbase would have been overrun and taken.

But that isn’t the point of this blog that I call Vacation Bible

School.

That brings me to the second thing you need to know before

you read the story. If you live in the

south, you know what Vacation Bible School is, however, if you live anywhere

else on the planet, you may not. For

you, let me explain. VBS is conducted

by churches, early in summer, usually a week or two after the final day of

school. Consider that from a kid’s point

of view. Just when you’ve acclimated to

a summer schedule, and weeks before you start counting the days left in your

summer vacation, you find yourself in church, hearing the same stories you’ve

heard twice a week forever, singing the same songs, drinking the same watered-down

lemonade, and eating stale vanilla wafers.

Do you get the impression that I didn’t like Vacation Bible School? Let me clarify that point for you – I’ll be

69 years old in a little over a week, and I still get goose bumps when I think

of the endless hours I spent in Vacation Bible School.

Now, the story.

The day President Kennedy was assassinated I got married,

for the first time. No one knows why

John Kennedy was killed. I do know why I

got married. I wanted to avoid being

drafted and sent to Vietnam. Things didn’t

work out the way I intended. A year

after my wedding the guidelines for drafting American males changed and

overnight married men with no children were eligible. I was one of the first invited to the

party.

I went through basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. Because I had done well on entrance testing,

I was sent to clerk’s school at Fort Jackson, SC. I was the only draftee in the class. My fellow recruits traded a year of their

lives to be clerks rather than risk being assigned to the infantry. I finished first in my clerical class and

when every one of my classmates came down on orders for Vietnam, I got orders

assigning me to the Advanced Personnel Management Center at Fort Benjamin

Harrison, Indiana. Five week later, I

again graduated first in my class. I

rode a troop train from Indianapolis to St. Louis, with the men I’d attended

class with. At St. Louis, they were

loaded on two buses for transportation to the St. Louis International Airport

where they would board a plane bound for Vietnam. I was moved into a private roomette for

transportation to my permanent duty station, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, known in

military circles as the “playground of the U.S. Army.”

Fort Sam was the home of the U.S. Modern Pentathlon Olympic

Team and Brooke Army Medical Center where doctors and nurses were converted

from civilians to Army officers. I

couldn’t believe my good fortune.

Fourteen months after my induction, I was promoted to Specialist

Five. I lived off post, and I had two

cushy jobs – one at base personnel, the other as a bartender at The Landing, a Dixieland

jazz club on the San Antonio River that is still in operation.

I would have spent the rest of my two year service

obligation at Fort Sam had my promotion to E-5 not included a new responsibility. I began processing the men who had completed

a tour in Vietnam and been reassigned to Fort Sam. At first glance, they looked like all the

other soldiers that I’d met in the past fourteen months, but almost immediately

I realized they were different – they were all different. I can’t explain it now any better than I

could have explained it then. About the

best that I can do is to say they didn’t talk about Vietnam, they seemed to

hear things I couldn’t hear, and to a man, they all had what came to be called “the

thousand-yard-stare.”

Within forty-eight hours, I knew I had to go to Vietnam to

see what had happened to the vets. I had

connections in the overseas orders department at the Pentagon, and with one

phone call I got myself on orders for reassignment to the 214th

Combat Aviation Battalion, headquartered on Camp Bearcat, ten miles from Long

Binh and roughly 30 miles from Saigon, as the crow flies. I chose the 214th hoping I’d be

able to crew on one the unit’s Hueys during my off duty hours.

I had to extend my 24 months service commitment by 12 months

in order to go to Vietnam. I didn’t

think twice about doing that, and two months after I began in-processing

Vietnam Vets, I was boarding a plane heading for Vietnam. I arrived at my new unit in May 1967. A couple of months later, I got a letter from

my wife informing me that in December I would be a father. I knew there was no way to get a leave to

attend the birth of my daughter so I didn’t ask for one. Early in December, Major Billy Sprague and

Sergeant Rossignoll, my immediate supervisor told me that if I would extend my

Vietnam tour by four months, I could go home for thirty days. They clinched the deal when they added that I

could muster out of the Army when I finished my extended tour. That meant I wouldn’t have to serve the six

months that would remain in my enlistment.

The deal was a no brainer. Less

than thirty-six hours later, I was on a chartered 707 heading back to the

states.

When I signed out, Major Sprague called me into his

office. He closed the door and said, “Sergeant

(he had converted me from a Specialist to a Sergeant when I joined the

battalion), scuttlebutt has it that the VC are going to stage a major offensive

next month. If that happens, I’m going

to need all of my NCO’s present for duty.

If there is any way you can cut your leave short and get on back, I’d

appreciate it.”

I’m couldn’t think of another moment in the previous

twenty-five years when I’d felt as needed as I felt in that moment.

I saluted and said, “You can count on me, Sir.”

He grinned and said, “I knew I could.”

Three weeks later, as I signed back in, Major Sprague walked

into the orderly room. As he passed me

he said softly, “Thanks, Sergeant.”

I just said, “You’re welcome, Sir.” We both knew what I meant.

Early, on the morning of January 31, 1968, all hell broke

loose and for once Camp Bearcat wasn’t being hit. Our first inkling of the magnitude of the

attack came when we got word that the 117th Assault Helicopter

Company, one of our units based at Long Binh, was pinned down by heavy ground

fire and couldn’t get a single chopper in the air. Shortly after that dispatch, we were ordered

to send Huey’s, with ammo, to the American Embassy in Saigon. The first chopper to land on the embassy took

forty-five hits crossing the street when it took off from the building. None of the crewmen were injured but the

chopper was in sad shape. It flew for

five miles before coming down in a rice paddy just east of the city.

Major Sprague sent Fleury, our company clerk, to find

me. In minutes I was talking to the

CO. He told me that our Pathfinders were

tied up and there was no one to secure the downed Huey. Before he could finish his sentence I said, “I’ll

get some men and do it, Sir.”

He laughed and said, “I knew you would,” then he hesitated

and said, “There’s not a man left in the area that’s qualified to do this, and

that includes you, Sergeant.”

I said, “Well, we’ll just have an OJT (on the job training)

experience.”

He thought about what I’d said then said, “See if you can

find twelve idiots to go with you… and…”

Finally I said, “And what, Sir.”

He blurted out, “And be careful, Son.” In the same breath he

turned to Fleury and said, “Don’t even think about going with him, Fleury. Don’t even think about it.”

Fifteen minutes later, eleven of the most unqualified

soldiers you can imagine, and an equally unqualified NCO, boarded two Hueys

that were running at a flight idle on the ready line. In seconds, we were airborne, heading toward

Saigon. Fifteen minutes later, I stood

on the skid of one of the hovering Hueys, took a breath and hoped there was a

bottom under the surface of the rice paddy I was about to jump into. There was.

As the sound of the two Huey’s faded, I thought, this is how all the troopers that I’ve been party to leaving in

isolated landing zones feel when we take off, leaving them alone.

I brought my attention back to the present, looked at the

shot-to-hell Huey half submerged in the center of the rice paddy and pointed to

various points on the dikes that enclosed the paddy as I dispatched my squad

with orders to stay alert and not make a sound unless I told them to.

With everyone in position, I evaluated the situation. In the distance, I could hear heavy fighting

in Saigon, punctuated by artillery and aircraft counter attacks. I looked at each member of my squad; five

clerks from my section, a Chaplin’s assistant, a communication specialist, a

medic, two cooks, the battalion supply sergeant, and me. Not a single one of us with infantry

training. I shook my head and moved

through the thigh deep water toward Robert Wilburn, one of my clerks. Robert was a really neat farm kid from Nebraska. I settled in beside him, my body, from the

waist down submerged in the wicked smelling water of the rice paddy. I knew I wouldn’t bet a dollar on our

chances of living through this. I wasn’t

scared, I was just being objective.

Moments later my mind turned to thoughts of leeches and unknown plagues. That’s when Robert whispered, “Hey Sarge.”

I whispered back, “Yeah, Robert.” Without hesitating he said, “Just remember,

it could be worse.” He hesitated and

then added, “We could be in Vacation Bible School.”

In half a second my John Wayne demeanor vanished like smoke

in front of a breeze, and I lost it.

Then Robert lost it. When we

regained a bit of composure, Sergeant Ferguson, our Supply Sergeant, called

out, “What is so damn funny?”

I shouted back, “Robert said that things could be

worse. We could be in Vacation Bible

School.”

Apparently every member of my makeshift squad knew what

Vacation Bible School was because instantly they roared as one.

We survived the day and in the process fulfilled our

objective. Just before nightfall, one of

our Chinooks, flying low and slow, appeared on the horizon. Within minutes, Howard Dirler, my good friend

and the NCO in charge of our Pathfinder Platoon, had his men rigging a harness

around the Huey. Minutes later, the twin

rotor helicopter easily lifted the disabled chopper out of the Rice Paddy and

headed off toward Camp Bearcat. Minutes

later, two Hueys with a Cobra escort came and picked up my squad and me.

*********

Every time I’ve faced impossible situations in the

forty-three years since the first day of Tet 1968, I’ve thought of Robert and

heard him say, “Things could be worse, Sarge.

We could be in Vacation Bible School.”

I thought about it in 1995, when I was sliding upside down

in my Jeep Wrangler down an Alabama highway after flipping to avoid hitting a

dog and in the process being hit by a UPS delivery truck. I thought about it when I collected 412

rejections slips in my search for an agent to represent me and my book, Fourth

and Forever. I thought about it

in 2005, when Christina and I ran out of money and housing at the same time and

found ourselves numbered with America’s homeless.

If you only get one thing from my Tet experience, get this,

no matter what situation you’re in, it could always be worse, you could be in

Vacation Bible School.

August 28, 2011

Let me tell you a story...

Sit down, take a deep breath, and relax. Let me tell you a story, a true story. I’ll begin this way…

Sit down, take a deep breath, and relax. Let me tell you a story, a true story. I’ll begin this way…

I lived and worked in Laurel, Mississippi, from 1979 through

1982. I moved there from Mobile,

Alabama, where I’d also lived for three years.

Prior to living in Mobile, I lived in Jacksonville, Florida for…, you

guessed it, three years. When I left

Laurel, my three year cycle was broken, due in large part to the book, Round

the Bend, by Nevil Shute.

When the chartered 707, carrying over two hundred of us, cleared

Vietnam’s airspace I thought I’d closed a chapter in my life story. I didn’t realize then that life doesn’t have

chapters. I know now that life is a

never-ending story; one sentence leads to the next, to the next, to the next… I

knew that I wanted to stay in the small north Florida town where I’d finished

high school, at least until I got a few things sorted in my head. That didn’t work. The only job I was qualified for existed

only in the Republic of South Vietnam.

The job I finally accepted didn’t pay enough to support me and my family. Within two months, I was back to searching

for a job.

To make a year’s long story shorter, in 1976 I was working

for Ryder Truck Rental in Jacksonville, Florida. After three years in Jacksonville, I

transferred to Mobile, Alabama. One day

a man came into the shop, told me he was from Mississippi, where he worked in

trucking. He asked if he could take a

look at our new shop. I gave him the

whole tour, more than he bargained for,

I thought later. But I was wrong. Inside of a week, he called and told me that

he and his brother would like to offer me the position of Managing Partner in a

car dealership they owned in Laurel, Mississippi. I had moved to Mobile when I discovered that

Vietnam Veterans were not in Ryder Truck Rental’s future District Manager

personnel pool. I thought about that for

a couple of seconds, and then told him I’d like to talk more about their

offer.

Two days later I accepted the position, sold my house in

Mobile, and moved to Laurel. My first

day on the job was a shocker. I

discovered that everything I’d been told about the dealership was a lie. The only assets the business had was a falsified

balance sheet and two lines of credit secured by the automobiles. They went on to explain that they generated

operating capital by using the proceeds of sold cars rather than paying them

off within twenty-four hours required by the terms of the credit lines. Seeing the shock on my face, my partners explained

that “everyone did it,” and made it clear that they expected me to lie, to the

representatives of the two institutions that issued the lines of credit, about

the whereabouts of cars that weren’t on the lot,.

I ignored the loud voice in my head that was screaming, “Don’t

do it!” And I did do it. I convinced

myself I had no choice. I lost sight of

my innate knowing that we always have a choice.

For the next two years I ran the dealership, on misappropriated funds,

and every day the knowledge of what I was doing ate at me.

One evening after I closed the business, I went to the

Laurel Public Library and began browsing the shelves for a book that I hoped

would get my mind off the condition I’d let my life slip into. I’d been up and down a few rows of fiction

when I stopped to look at the books at eye level. A second or two later something rustled on a

higher shelf. I looked up just as a book

bailed out of its place two shelves above my line of vision. I caught it before it hit the ground. I looked around to see if anyone had noticed

what had just happened – it’s a guy thing.

I was disappointed to see that I was alone. Only then did I look at the book.

It was Round the Bend by Nevil Shute. I had never heard of the book or the author. I

opened it to the first page and read:

“I came into aviation the hard way. I was never in the R.A.F., and my parents

hadn’t got fifteen hundred pounds to spend on pilot training for me at a flying

school. My father was, and is, a crane

driver at Southampton docks, and I am one of seven children, five boys and two

girls. I went to the council school like

all the other kids in our street, and then when I left school Dad got me a job

in a garage out on the Portsmouth Road.

That was in 1929.

I

stayed there for about three years and got to know a bit about cars. Then, early in the summer, Sir Alan Cobham

came to Southampton with his flying circus, National

Aviation Day, he called it. He

operated in a big way, because he had about fifteen aeroplanes, Avros and Moths

and a glider an Autogiro, and a Lincock for stunting displays, and a big old

Handley Page airliner for mass joyriding, and a new thing called an Airspeed

Ferry. My, that was a grand turnout to

watch.”

The next morning, as the sun rose on Laurel, Mississippi, I

read the final passage.

The following week a representative from one of the lending

institutions came to the dealership and counted the cars. When he finished he came in my office and

said, “Hi Bert. You’re missing a few

cars. Tell me where they are for my

report, and then we can go to lunch.”

I looked at him, smiled, and said, “Jerry, I sold them, and

I’m using the money to keep the dealership running.”

I didn’t go to lunch that day and that afternoon I told

Jerry’s boss exactly what I’d told Jerry, expecting to hear him say that I was

about to go to jail. Instead, he looked

at me and said, “We’ve known that for a while.

Most of our dealers are doing it.”

He paused, opened his briefcase, pulled out an envelope, looked at me

and continued, “I have a check here for you in the amount of $250,000.00. It’s an unsecured loan…”

I don’t know what else he said, but I do remember, like it

was yesterday, that when he finished talking I looked at him, and then I looked

at my two partners who had joined the meeting, and said, “You three can do what

you want to do, but the last couple of years have convinced me that this

business isn’t for me. I’ll be doing

something else from this day forward.”

Quickly, because it isn’t the point I want to make with this

blog post, I’ll tell you what happened next.

The lending institution wouldn’t make the loan unless I was the Managing

Partner and my partners didn’t want to operate without me running the place, so

we closed the business.

What is my point in telling you this? That’s simple. A book I’d never heard of changed my

life. It wasn’t a self-improvement book. It was a novel, a novel written by a novelist

who wrote twenty-one other books; a writer, just like you and me. He sat at a typewriter a long time ago and

poured himself into telling a story. He

didn’t write that story for me, he wrote it for himself, and he gave it his

very best effort. We have got to do the same. We can’t afford to give our writing anything

but our very best shot. We shouldn’t do

it for money or fame. We should write

for ourselves and because just maybe, one day someone is going to find our book

and read it because they need to get their mind off what’s going on in their

life. And, you can trust me on this, the

answers that make a difference are written into novels by authors just like you

and me; writers who know what matters and are willing to write about it.

Oh yes, the final passage of Round

the Bend goes like this:

“I still think Connie

was a human man, a very, very good one – but a man. I have been wrong in my judgments many times

before; if now I am ignorant and blind, I’m sorry, but it’s no new thing. If that should be the case, though, it means

that on the fields and farms of England, on the airstrips of the desert and the

jungle, in the hangars of the Persian Gulf and on the tarmacs of the southern

islands, I have walked and talked with God.”

August 24, 2011

Three Men and a Horse

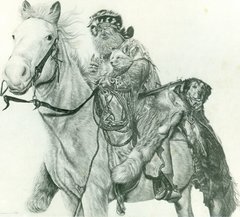

Yes, that is Robert E. Lee and the horse is Traveler. Don’t be concerned, this is not a story about

Yes, that is Robert E. Lee and the horse is Traveler. Don’t be concerned, this is not a story about

the American Civil War. The war plays

into it but only as backstory.

War is the manifestation of political failure. There are no exceptions. I always believed that, and then I went to

Vietnam and proved it. No matter what

you believe about war, you can know that I’ll never glamorize it. On the other hand, war is the essence of the

history of mankind, on the planet so there is no way I can ignore it.

I said all that to let you know this, this blog post is not

about the “glamor of war.” There is no

such thing. This story is about three

men and a horse who were drawn together by a war, and who shared a personal

trait that everyone who strives to succeed must have.

Robert E. Lee, a career army officer, engineer, and West

Point graduate, was offered the command of the Union Army. When Virginia, his home state, ceded from the

United States, Lee declined the offer and accepted Jefferson Davis’ offer of

the command of the Confederate Army. Lee

received both of those command offers because he was known to be a man of

impeccable character and integrity. A

man you could depend on.

General Lee had a string of four horses. The last horse added to the string was a two

year-old gelding named Traveler, the youngest of the General’s horses. On one of the first days that Lee rode

Traveler into battle, the horse, spooked by the noise of shells exploding and

muskets firing, reared and threw the General who landed with all of his weight

on his hands. For the next two weeks,

Lee’s wrists were so sore they were bandaged, and he couldn’t hold a horse’s

reins. His groom suggested that Traveler

be reassigned to the cavalry but Lee said no.

The next day, with assistance, the General mounted Traveler and rode

into another battle. This time the great

horse didn’t so much as quiver as he moved in the direction and at the speed the

General indicated with only soft verbal commands and knee pressure.

From that day, Traveler was the General’s number one horse. Soldiers reported that the most reassuring

sight they saw during a battle was a glimpse of Traveler and General Lee coming

steadily through the chaos and ear splitting noise. Wounded four times, Traveler took the General

home after the war, retired with him, and outlived the Confederate Commander by

four years.

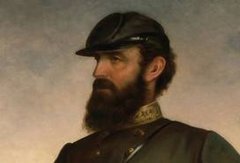

Thomas Johnathan

Jackson, a graduate of West Point, was a mediocre professor at Virginia Military Institute,

when Robert E. Lee invited him to join the Confederate Army as a division

invited him to join the Confederate Army as a division

commander. There was nothing in Jackson’s

history that justified the offer.

However, Lee had a keen insight into the character of men, and he saw

something in Jackson that wasn’t reflected in his history. Outnumbered by a better equipped force in his

first major battle with the Union Army, Jackson rallied his troops by standing

firm on the most dangerous spot on the battlefield. A junior officer reported later, “Me and my men

were ready to run when I looked through the smoke and haze of the battle and

saw General Jackson, facing the enemy and standing like a stone wall.” From that day until his last, General Jackson

was simply known as “Stonewall.”

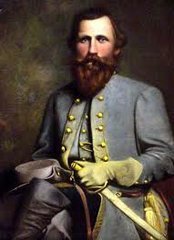

James Ewell Brown Stuart, better known as JEB Stuart, had

James Ewell Brown Stuart, better known as JEB Stuart, had

the well-earned reputation of a light-hearted, flamboyant, playboy. General Pickett’s wife, in her journal,

described him as a “banjo player.” Like

Stonewall, there was nothing in his background, beyond his West Point training,

that qualified him to be a cavalry General, yet that’s exactly what Robert E.

Lee asked him to be. JEB accepted

without hesitation, sending reports and dispatches to Lee that the commander

knew he could count on. In fact, the

closing line on every document Stuart sent to Lee was simply, “Yours to count

on.”

It is reliably reported that Robert E. Lee was only seen to

cry on two occasions during the entire war.

The first was upon learning of the death of General JEB Stuart, and the

second when he was told that General Stonewall Jackson had been killed.

Jackson, Stuart, and Traveler, had a trait in common. They could be counted on. No matter how hopeless a situation they found

themselves in, they never stumbled or faltered.

If we intend to achieve our objectives, no matter what they are, we must

share that level of commitment and resolve.

A number of years ago AT&T aired a radio commercial that

expressed that sentiment perfectly. In

an assured tone a man stated positively, “If you leave a message for me, and I

don’t get back to you, you can be sure that I’m dead.”

“Yours to count on,” is a commitment. It is a commitment to self. Beyond that it’s a commitment to a task, an

ideal, or to another person or group of people.

But first and foremost it is a commitment to self. When you make that commitment and honor it,

everything else falls into place.

August 15, 2011

Black women... unconditional love

As I

began writing this, I thought of many black women I've known whose picture I

could use to illustrate the piece. One

you might know, is Della Reese who took my hand one morning almost twenty years

ago,  looked right in my eyes and said, "Bert, always remember this; don't

looked right in my eyes and said, "Bert, always remember this; don't

take anything for granted. Just as soon as you hit the top they'll run a

Whitney Houston in on you." Then she laughed, and it was so contagious she

instantly had everyone on the far side of the room laughing though she and I

were the only ones who knew what she was laughing at.

A

second example I thought of was Rev. Dr. Johnnie Coleman, the founding minster

of Christ Universal Temple in Chicago.

Johnnie came from Mississippi with an innate understanding of the

oneness of all things and a desire to share that understanding with others; and

she did. She spent fifty  years building

years building

a ministry that was her vehicle for sharing universal love. She is regarded as the first lady of new age

but she is way more than that – Johnnie Coleman is love walking the earth.

Then I

thought of Rev. Ruth Mosley, who founded a Unity Church in downtown Detroit, and

refused to leave the neighborhood, even when most people felt it was unsafe. The last time I spoke in her church, Rev.

Ruth met me in the parking lot when I arrived.

As we walked toward the church, she said, “Bert, you’re going to have to

speak up today. Can you do that?” We stopped walking and she turned toward as

she said softly, “Last night one of the neighbor children broke in the church

and took our new sound system.”

I said,

“Rev. Ruth, if my voice starts failing everybody can move to the front.”

As I

write this, I can see what happened next like it happened yesterday. Smiling, and with her eyes sparkling, she

looked into my heart and said, “Lord, I know that’s right.” Then she patted my back. I’d have shouted for four hours if that’s

what it took.

And I

thought of Mrs. Lillie Hoskins who has

run a day care center in Batesville, Mississippi for twenty-five years and goes

through life trailed by clouds of love yet doesn't even know it. At last count, twelve valedictorians of South

Panola High School are graduates of Hoskins Learning Center. Lillie Hoskins has dedicated herself to

making sure that “her children” don’t take a back seat to anyone, and her love

and dedication have paid off.

And I

thought of Louise (there is no one left in my family who remembers her last

name) who took care of me every afternoon from the second grade through the

fifth. One day, I told her that I could

always see a halo around her head. She

stopped ironing, chuckled, patted my head, and said, “I wouldn’t tell anyone else

that, if I was you,” and we laughed.

Finally

Finally

I thought of my new Twitter friend, Ni’cola Mitchell (@MsNicola) who is responsible for this

post. I tweeted something to her and she

replied, “Thank you, Sweetie,” and a whole lot of wonderful memories filled my

mind. In seconds, I renewed my

commitment to finish and post this blog because it’s important.

My list

goes on and on but I’ll stop there. I didn't use Della's picture, or

Johnnie Coleman’s, or Ms Lillie's, or Ni’cola’s – I used them all and one of Norma

Jean Anderson, who I’ve not told you about yet.

When I think of black women and unconditional love she is the one that first

comes into my mind. Norma Jean is gone now.

She left an amazing list of accomplishments - too many to even begin to

note in this posting. But, as far as I'm

concerned, the most memorable of them occurred one night, twenty odd years ago,

in her home, when I blurted out, "Norma Jean, would you be my

mother?" She didn't laugh or pretend that she hadn't heard. She looked

into my eyes and my heart and my soul and then she smiled and said, "Bert,

it would be an honor." Norma Jean passed away almost four years ago but

she will be with me forever, as will Della, Louise, Lillie, Ruth, Ni’cola, and

a growing host of others.

I am a

white man, not something I had anything to do with, and certainly not something

I'm proud of. From a conventional point

of view, white men are the most powerful group on the planet. However, I'll be the first to own up to the

fact that a white man’s power is second rate when compared to the power of the unconditional

love of a black woman. In fact that's the point of this posting. I've done a

lot of things in this life and to be honest, everything being the same, I'd do

them all over again. Do I have any regrets? Well, sort of - but it's not about

anything I've done or failed to do. My regret is that I didn't spend this life

as a black woman rather than a white man.

I know that black women are the masters of unconditional love. It's in their

eyes, their hearts, and their every breath. No matter what you've done or who

you've done it to, they'll still love you. When a black woman looks in your

eyes and says, "Honey, it's going to be all right." You know that it

is.

I'm stuck with being a white man for the rest of this trip but I do have a

consolation - I have the friendship and love of a long list of black women and

that list grows longer every week.

“Thank

you, Sweetie.”