M. Louisa Locke's Blog, page 14

October 9, 2012

Historical Fiction Books of My Childhood

In the coming months, many of the members of the Historical Fiction Authors Cooperative are going write about the books that influenced their decisions to write historical fiction. In my own case, I was startled to realize the enormous effect the books I read as a child had on both my thirty-year career as a history professor who specialized in social and women’s history and my second career writing my Victorian San Francisco Mystery series (see Maids of Misfortune and Uneasy Spirits).

I was a voracious reader as a child, and my mother took me every week to the huge Carnegie Library in the next township so I could check out enough books to get me through to the next week. It was the 1950s and early 60s, and there were no local bookstores in my neighborhood, no Amazon.com, and most of the books in my house were either my mother’s childhood books or the books I got as presents for birthdays and Christmas.

I probably read thousands of library books in my youth, but my favorites were the hardbacks my family owned, that my parents read to me, that I learned how to read from, and that I read over and over. In fact, these favorites are sitting up on the shelves of my study still today.

The rest of this post is on the Historical Fiction eBooks blog .

September 10, 2012

Report on my latest KDP Select Free Promotion: Getting into that Holiday Spirit

Well, Amazon announced its new Kindles devices this week, and the first of the new Kindle Fire HD devices ship as early as next week, with the rest rolling out in October and the end of November. There is no telling at this point how many of these new devises will be bought as upgrades or additions by people who already have Kindles, but if the past two holiday sales patterns are any indication, authors should expect a growing number of new users to start looking for Kindle books over the next few months, culminating in a book buying frenzy in the months after Christmas. At least that is my hope.

In December 2009, my first book, Maids of Misfortune, had just been published, my Kindle sales were miniscule, and unless you typed in “Victorian mystery” as a key word search, you probably wouldn’t have found my book anywhere in the Amazon store. Then, if you found it, the $4.99 price for an unknown book by an unknown author, without any reviews, probably would have discouraged you from buying it. In fact, only 74 people bought a copy of that first book during the 4 months––December thru March of 2010, and I suspect a good number of them were friends and relations.

A year later, in time for the next holiday season, everything was different. The introduction of the Third Generation Kindle in August of 2010 had expanded the number of devices in consumer’s hands and by December of 2010 my book was now priced at $2.99, was #1 in the historical mystery category (so was no longer invisible), and I had eight 4 and 5 star reviews. I sold 7,400 books between Dec 1 and March 31, 2011, and I was able to quit teaching for good and start writing my second book.

Last holiday season was even better. I now had two books out, Maids of Misfortune, and Uneasy Spirits (published in October 2011). I had thirty 4 and 5 star reviews for Maids and already had six 4-5 star reviews for Uneasy Spirits, and both books were on the historical mystery bestseller list (albeit pretty far down because the list had just expanded exponentially). Even more importantly, that fall Amazon had just rolled out a $79 ebook, the Kindle touch, and the Kindle Fire, and there were a whole lot of new Kindle owners looking for books by Christmas. And, as I have written elsewhere, KDP Select and the free promotions I ran at the end of December, February, and March kept both of my books visible in the historical mystery category. The result? I sold 18,970 books between Dec 1 and March 31, 2012.

So, how am I making sure I am ready for the new crop of Kindle owners shopping for books this fall and Christmas season?

First of all, I made a price change this spring, raising the price of both of my books to $3.99. I did this because there is growing research that there a segment of the buying public out there that believe a 99 cent or $2.99 price point represents a book of lesser quality. And, while I have no desire to gouge my readers, raising my books to $3.99 seemed a way to tap into that segment of the buying public now that I am no longer such an unknown author.

Second, my KDP Select promotions have increased the number of my reviews significantly. I have gotten used to the fact that promotions also seem to attract people who wouldn’t ordinarily read my brand of cozy mystery and therefore can be negative, but I have also been very fortunate that the positive reviews tend to drown them out. Currently Maids of Misfortune has an average of 4.2 stars from 126 reviews and Uneasy Spirits has an average of 4.3 stars for 42 reviews. I know that this makes my books very competitive with the traditionally published books that cluster at the top of the historical mystery category. I still find it remarkable to have my ebooks ranked right along with the books of Anne Perry or Laurie King in my sub-genre.

Third, and probably most importantly, after my brief experiment with other booksellers, I re-enrolled my two books into KDP Select and mounted my most organized promotion yet, bringing both of my books back to full visibility.

My last promotion of Maids of Misfortune was June 23-24, 2012 and the book then went off of KDP Select (which meant no free promotions and no borrows.) That last promotion had been moderately successful, (6900 downloads) pushing Maids’ rank from the 7,000s to the 4,000s and increasing its rank on the historical mystery popularity list from 25 to 9 (although it stayed about the same, mid 20s, on the best seller list before and after the promotion.)

The last promotion of Uneasy Spirits before going off KDP Select was July 2-4, and, as usual, the sequel didn’t do as well as Maids did, despite being free for 3 days rather than 2 (I believe this is primarily because Maids is in 9 categories and subcategories and Uneasy is in only 4––see my posts on categories––which limits its visibility on free days). Uneasy Spirits had only 1440 downloads, and its rank didn’t improve much, keeping Uneasy Spirits in the 7000s and the 40s in both popular and bestselling lists for historical mysteries. One of the reasons that I decided to try going off of KDP Select was the feeling that I had, at least temporarily, saturated the market for my books among those who routinely browse the free lists.

I signed both books back up to KDP Select August 12, 2012. At that point, both books had slipped in terms of sales to their lowest point this year, and I immediately organized a promotion for both of them for August 20-22, hoping to have sufficient success to drive them back up the rankings and increase visibility, which would increase sales. (Maids was free 8/20-21; Uneasy was free 8/21-22)

This promotion did exactly what I wanted. My ranking in categories improved dramatically, which resulted in a distinct sales bump for both books, and in the two weeks after the promotion people have borrowed my novels 365 times.

Before Promotion

After Promotion

During Promotion

Maids of Misfortune

Over all Rank Paid List

14, 418

1,645

Historical-mystery bestseller rank

91

10

Historical-mystery popularity rank

127

5

Total sales in one week*

40

311

Average sales per day*

5.7

44.4

Total downloads

21,767

Peak rank in Free List

#7

Uneasy Spirits

Before Promotion

After Promotion

During Promotion

Over all Rank Paid List

23,352

5553

Historical-mystery bestseller rank

not on it

28

Historical-mystery popularity rank

127

11

Total sales in week

43

145

Average sales a day

6.1

20.7

Total Downloads

11, 572

Peak Rank in Free List

23

What I did to promote my free books––see a more extended post on Free Promotional Tips:

First, I thought carefully about how to schedule the promotion. I had noticed that the list of free books seemed longer on weekends (when I usually schedule mine), so I decided that I would try Monday through Wednesday this time. The fact that is was still officially summer, when some people are on vacation and not locked into the reading on a weekend routine, seemed to make this a safe bet. The success of this promotion suggests that being during the week didn’t hurt.

I also decided to stagger the promotions, putting Maids free on Monday and Tuesday, then Uneasy on Tuesday and Wednesday. My experience is that when Maids goes free, Uneasy’s sales jump a little, so by starting it a day later, this would give Uneasy a little bump to help it in the after promotion averaging in terms of ranking (in fact I sold 50 copies of Uneasy that first day). But I also have found that Uneasy does better in free downloads if it is paired for at least one day with Maids. Remember, the greater number of categories Maids shows up in compared to Uneasy is always going to give it a better shot at getting enough downloads to reach the top 100 of the Free list (the holy grail if you want to do well with a promotion.) From my experience, if Uneasy is free on its own, it is less likely to reach that top 100, but if I pair it with Maids, Maids drags it up (people figure if both are free, and they are in a series, why not get both at the same time.) This gives it a better shot at succeeding on the second day when it is up on the free list by itself. This strategy worked, with both books hitting the top 100 by the end of the first day they were promoted.

Second, at least a week before the promotion (which I had already scheduled on KDP Select–this is important) I went on to the growing number of websites that advertise ebooks and scheduled a number of free and inexpensive promotions. I have tried a variety of these sites in the past year, and this time I concentrated on not just promoting the books when they were free, but also doing more general marketing that would continue in the week after the free promotion to help boost sales. For example, I notified Pixel of Ink, The Frugal Reader, Kindle Nation Dailyand Ereader News Today of the free promotions, but I scheduled general promotions with Digital Book Today and Kindle Nation Daily for the week after the promotions were over.

I also used my own website to market the free promotions. Ahead of time I put up on my website that the books would be free and made sure that this information was also at the end of two blog posts I did (one two days before the promotions, the second on the first day of the promotion). I also made sure that these two posts appealed to my two different audiences. The first post, Update on Kobo’s Writing Life, appealed to the people who are interested in my self-publishing journey, the second, Victorian San Francisco in 1880: Social Structure and Character Development, appealed to the fans of my book. I have no way of determining what effect these posts had in getting people to look for my books, except the anecdotal evidence that people did mention that week in comments and emails that they had read my posts and gone looking for the books for free.

During the promotion I took advantage of the over twenty facebook pages that cater to people who read ebooks, particularly those with Kindles. On the day of the promotion, or the night before for the UK sites, I put a brief notice on the walls of all of these facebook pages of the book, where and when it was free, its genres, and a link to the Amazon.com page.

I also tweeted about the promotion, and asked that fellow members of the Historical Fiction eBooks group I belong to tweet as well, since my books are historical fiction and would likely be of interest to their followers.

What I think these promotional efforts did was to get enough people at the beginning of the promotion to download the books so the books rose up high enough on all the separate free lists to become visible, which in turn resulted in enough downloads to push the books to the top 100 free books. In short they primed the pump. The promotions I did afterward may have helped the books make the transition from free to paid, which hopefully helped sustain the sales. I plan on doing more marketing between free promotions this time, to see what effect this might have on keeping the books visible. For example the World Literary Cafe has helped me expand my twitter followers and makes it easy to do mass tweets.

Summary:

I achieved my goal to make the books more visible on Amazon browsing categories, which in turn has increased sales.

I am selling over seven times the number of Maids of Misfortune a day than I was selling before t he promotion, and nearly 3 weeks after the promotion Maids is now firmly in the top 15 bestsellers on the historical mystery bestseller list, but it can also be found on the historical fiction and historical romance and the U.S. history bestseller lists. Uneasy Spirits, which is only showing up on the historical mystery bestseller list, is therefore not selling as much and it as already bouncing around the 30s and 40s in ranking on that list. Even so, it is selling over three times the number of books a day as it was before the promotion. Both books have also added to their reviews, which will also continue to make the books more competitive.

However, for both books, my primary goal in the next months will remain the same, making sure that both books are visible in the Amazon kindle bookstore. Because that visibility is the best way I can ensure that when the hundreds of thousands of people (dare we hope millions) receive their new Kindles in the mail or under the Christmas tree and see my books up there at the top of bestseller lists (with reasonable prices, pretty covers, snappy descriptions, and solid reviews) that they will click buy!

What are you doing to get ready for the holiday sales period?

August 20, 2012

Victorian San Francisco in 1880: Social Structure and Character Development

I have embarked upon writing Bloody Lessons, the third book in my Victorian San Francisco Mystery series that features Annie Fuller and Nate Dawson, which means I am creating a whole new raft of secondary characters. And, as I have done in previous books, I am carefully considering the specific social make-up of San Francisco as I do so.

What follows is a brief summary of the social structure of San Francisco in 1880 (primarily from my dissertation, Like a Machine or an Animal) and how this has influenced some of the choices I have made in developing my characters in Maids of Misfortune and Uneasy Spirits, the first two books in my mystery series.

Brief Summary:

“In 1880 San Francisco, with a population of 233,959 residents, was the ninth largest city in the United States. Located at the end of the peninsula that separates the Bay of San Francisco from the Pacific Ocean, this city of hills, sand dunes, fogs, and mild temperatures had been only a small village called Yerba Buena less than forty years earlier. This small village was one of the chief beneficiaries of the incredible influx of people into the region after the discovery of gold to the north in the winter of 1847-48. In the early years of the Gold Rush, the town grew by over 1000 percent. Even in the 1860s San Francisco still grew at a rate of over 160 percent, but into the next decade the rate of growth slowed considerably to 57 percent, and the city would continue to grow at ever slower rates throughout the century.

“High sex ratios (more males than females) have traditionally accompanied high rates of growth, and this was particularly true in the Far West where so much of the initial growth in population was due to the in-migration of young single men searching for gold. San Francisco followed this rule, although it consistently had a more balanced ratio than did the state as a whole. Nevertheless, by 1880, as the city increasingly became the destination of families or as the earlier settlers either married or sent for their wives and children to join them, much of the imbalance in the sexes had disappeared. Most of the remaining imbalance reflected the large number of Chinese in the city, since most of the Chinese who immigrated to America at this time were males. In fact, among some groups in the city, the Irish for example, women now outnumbered men.

“As the number of women in the city grew, the proportion of families and children did as well. The percentage of adult males who lived in family households rose from fifteen percent in the 1850s to forty percent in 1880, and the average number of children per family rose as well. In addition, the city’s residents were now more likely to have been born in the Far West, and by 1880 over sixty percent of the city’s native-born population had been born in California.

“A significant number of the parents of these California born city residents were immigrants who had traveled to the Far West. In fact, from the beginning of San Francisco’s development, immigrants were more likely than the native-born migrants to be married or to bring their families with them when they moved to the city. In 1880 nearly 45 percent of San Francisco’s population was foreign-born, and if those native-born persons with foreign parents are considered, the proportion of residents with foreign parentage rises to over 74 percent.

“Reflecting national patterns of immigration, the foreign-born population of San Francisco consisted primarily of immigrants from Ireland (29.5%) the German Empire (19.1%) and Great Britain (9.6%). People from these three areas comprised over half of all the immigrants living in the city in 1880. However, the ethnic composition of San Francisco at this date did deviate from the ethnic composition of cities elsewhere in the nation in one substantial way. Chinese made up the second largest number (20.3%) of the foreign-born in the city; this was a proportion that was vastly greater than could be found anywhere outside of the Far West. In addition to the Chinese, Irish, German, and British immigrants that comprised the bulk of San Francisco’s foreign-born population, smaller numbers of French, Canadian, Scandinavian, and Mexican immigrants gave San Francisco an exceptionally cosmopolitan flavor. One Eastern visitor in 1880 felt that the city appeared even more cosmopolitan than New York City, commenting that when she asked a question on a San Francisco Street, it was ‘answered in a dozen different tongues.’ (Dall, My First Holiday 1881)

“The inhabitants of San Francisco did not share equally in the economic opportunities of the period. A foreign birthplace or a specific ethnic heritage clearly influenced entry into certain jobs and the possibilities of advancement. As a result, different groups clustered on different rungs of the city’s social ladder. Native-born residents of both sexes were much more likely than immigrants to hold white-collar jobs, while they were much less likely to work as semi-skilled or unskilled laborers. Native-born males in the city showed a greater degree of upward mobility as well.

“On the other hand, within the foreign-born population of San Francisco the occupational patterns of specific ethnic groups differed significantly, and some groups had better success at achieving or maintaining a higher occupational status than others. For example, among both males and females, the tendency of German immigrants to fill jobs within the lower white-collar ranks, particularly as petty merchants, meant that the occupational pattern of Germs did not deviate substantially from the pattern of native-born workers.

“Many of the young men who came to America from German in the nineteenth century first set up as peddlers on the east coast and then moved to the Far West to take advantage of the boom engendered by the Gold Rush. There they often worked first in the interior mining of farm towns until they could get enough capital to relocate in San Francisco as retail or wholesale merchants or manufacturers.

“By 1880 these Germans represented 34 percent of the merchant population of the city, comprising a much higher fraction of the merchant class than they did of the total city population. These German merchants concentrated in clothing and dry goods, and in the cigar trades, and they had a high degree of persistence in the city. Because Germans, including German Jews, played such an important role in the city’s merchant community, this group occupied a unique and favored position in the social hierarchy of San Francisco. While ethnic and religious prejudice against the Germans did exist in the city, and although Germans were not totally integrated into the ranks of the native-born elite, German Jews seemed to experience much less discrimination in San Francisco than they did within any comparable city in the nation in this period.

“While the backgrounds and eventual occupational success of the Germans and English permitted these two groups entrance into the social elite of the city, the Irish faced much greater obstacles. Their backgrounds of rural poverty and inadequate education constituted a handicap in employment, even though many of the Irish had settled on the east coast before traveling west. As a result, the Irish in San Francisco were under-represented in the white-collar or merchant occupations of the city, and as many as a third of them worked as common laborers in 1880. However, the Irish in San Francisco were upwardly mobile, for not only were Irish males increasingly more likely to work in white-collar jobs between 1850 and 1880, but their native-born children gained in occupational status.

“Native-born children of the Irish found that their greater experience with urban life and their greater access to education offered many of them a chance to escape from the ranks of unskilled labor into skilled, semi-skilled and white-collar jobs.

“Although proportionally fewer Irish climbed to the top of the business elite in San Francisco, this group was certainly not excluded from the bastions of power within San Francisco. As Burchell has pointed out, ‘The Irish in San Francisco fought their way up the political ladder in the usual fashion and met with the normal nativist response. But their success was more complete by 1880, even by 1870, than that of their group in other major cities.’ (Burchell The San Francisco Irish 1979) Partly because of their sheer numbers and partly because of the unusual degree of fluidity within early San Francisco, the Irish found relatively greater political and economic success in this city.

Social Structure and my character choices

The main protagonists in my mystery novels, Annie Fuller, a widowed boarding house owner, and Nate Dawson, a lawyer, represent the dominant group among the middle and upper classes of San Francisco residents living in the city 1880 because they are of native birth and parentage. Annie was born in the city, and Nate moved to California with his family as a young boy. While both live in boarding houses, (San Francisco was famous for hotel and boarding house living for all classes) Annie’s boarding house, containing a mother and child, a married couple, two unmarried sisters, a single woman, and two single men, reflects a city that was no longer the boom town of only young single men it had been thirty years earlier.

The servants working in Annie’s boarding house, Beatrice O’Rourke and Kathleen Hennessey, are of Irish heritage, (as is Nellie, the Voss parlor maid in Maids of Misfortune, and Biddy, Kathleen’s friend and a servant in the Frampton house in Uneasy Spirits) because the Irish not only made up the largest percentage of working class residents of any ethnic group in the city, but domestic service was the occupation held by a majority of women of Irish birth.

At the same time, as mentioned above, the Irish were extraordinarily successful in achieving political power in San Francisco, one result being the large number of Irish found in city employment, including the police force. Hence my decision to make Beatrice O’Rourke’s deceased husband and her nephew, Patrick McGee, be Irish police officers.

However, when I was looking for a non-Irish immigrant to hold the job of cook in the Frampton household, it was easy to decide that the uncommunicative cook, Mrs. Schmitt, should be German since German immigrant women were almost as likely to hold domestic service jobs as were the Irish.

On the other hand, while Irish and German servants would have been common in any middle class household in any American city outside of the South during this time period, Chinese males servants like Wong, who worked in the Voss home in Maids of Misfortune, would have been rarely found in any city outside the Far West. In later posts I will elaborate about the unique pattern of Chinese migration to San Francisco.

Finally, while I haven’t been explicit about the ethnic heritage of Annie Fuller’s prize boarders, Herman and Esther Stein, their names represent their German heritage. I chose this background for them because I wanted to provide an example of that interesting group of San Francisco residents, wealthy German merchants, bankers, and manufacturers.

In the book I am working on, Bloody Lessons, a good proportion of the minor characters are going to be teachers. I will need to keep in mind that the majority of teachers in San Francisco, as was true for the nation, were females, and that the men who did teach dominated the higher grades and administrative positions. I will also need to keep in mind the unusually important role of immigrants and their offspring in San Francisco.

The ethnic composition of San Francisco teachers reflected the fact that nearly two-thirds of San Francisco’s residents were either immigrants or the children of immigrants. As a result, 60 percent of the young women who taught in San Francisco in 1880 were native-born with immigrant parents, and another 12% were foreign-born. The percentage of female teachers in San Francisco who were of foreign birth or heritage was actually double that of the percentage found in either Portland or Los Angeles in that year.

These are just some of the ways I try to ground my mysteries in an accurate portrayal of the past, and I hope you found it added to your enjoyment of the series.

For those of you who haven’t yet read either Maids of Misfortune or Uneasy Spirits, you might check out the promotional offerings below.

Maids of Misfortune will be FREE on KINDLE Monday-Tuesday August 20-21 and

Uneasy Spirits will be FREE ON KINDLETuesday-Wednesday August 21-22.

The AUDIOBOOKversion of Maids of Misfortune will be discounted to $5.95 (even less to audible.com members) Saturday August 25 to Sunday September 2.

M. Louisa Locke

August 18, 2012

Update on Kobo’s WritingLife: A Work in Progress

As I discussed in my last post on my experiences going off of KDP Select, while I was not entirely happy with Kobo’s new indie publication initiative, WritingLife, I was pleased that, unlike Barnes and Noble, the support staff I contacted were very responsive to my communications with them over problems I encountered. So I feel I should point out a positive change that has happened this week. If you read the blog post, you will know I was concerned about with the way Kobo treated free books, and I was glad to discover there is now a 3rd way you can find free books–by clicking on a link that says Search a List of our Latest Free Books.

When I discovered this link and clicked on it this morning, I was surprised to discover that my short story Dandy Detects was listed first. I don’t know why it is at the top of the list. (I am assuming it was not there because I was a squeaky wheel!) I suppose Dandy could have had the most free downloads recently (which would be surprising-given that the #4 and #5 books on the list are short stories by N.Y. Times bestselling authors Jennifer Weiner and Bella Andre) or it could simply be the newest book put on the list, and if so, in time, no matter how popular it is, it will sink. It is also clearly a very abbreviated list, since there are only 172 books listed and most of them still seem to be public domain books. (Whereas if you put in the key word historical mystery and filter for free you get 880 free books-so obviously there are a lot more free books available on Kobo.) But if it is simply list of most recent free books, and Kobo readers can find this list on their devices, this might begin to help create a greater interest in free books from Kobo consumers, and that should help authors use the free promotion option to highlight their books.

However, from the author’s point of view, it is still frustrating to have no idea how many free copies of my story have been downloaded. And, I am assuming that the numbers must not be terribly large since my experience in other ebookstores is that a certain percentage of people who read Dandy Detects for free then immediately buy my other short story, The Misses Moffet Mend a Marriage, which is only 99 cents. But I have had only 1 sale of that book since Dandy went free. I am trying to be patient.

While I am on the subject of Kobo, I did want to add something else positive about Kobo (with a caveat). Kobo permits an author to link to their GoodReads reviews, which is of particular benefit to authors who have just put up a book on the site. In other bookstores like Amazon and Barnes and Noble and iBooks, you have to wait for people who have bought the book in that store to put up reviews, which can take months if not years. But because of Kobo’s policy, Dandy Detects, which has been available on Kobo for only a month, has 88 reviews. The downside of this policy is that there doesn’t seem to be a way for a reader to post a review directly on Kobo (all they can do is give them stars and it is not clear to me how a star rating by a Kobo reader is folded into the GoodReads star ratings.)

This can be a problem because not every author wants to put their books up on GoodReads, particularly when there are competing reader sites like Shelfari and LibraryThing that they may find more compatible. For example, just recently there was a huge controversy over retaliatory reviews on GoodReads that caused some authors to remove their books from this site. See the posts by Vacuous Minx for a discussion of some of these issues. The fact that linking to GoodReads is the only way for a book to get reviews on Kobo would then be a real handicap for these authors (or authors who have suffered a lot of negative reviews in one of these retaliatory wars).

In short, I applaud Kobo for the steps they have taken to be innovative and responsive to authors’ and readers’ needs, but they are definitely still a work in progress. Nevertheless, I am having fun watching the changes unfold.

As always, I would love to hear from all of you, particularly those of you who own Kobo readers or have published with them.

In addition here is some Shameless Blatant Promotion on my two Victorian San Francisco Mysteries now that I am safely back in the KDP Select fold.

Maids of Misfortune will be FREE on KINDLE Monday-Tuesday August 20-21 and

Uneasy Spirits will be FREE ON KINDLE Tuesday-Wednesday August 21-22.

The AUDIOBOOK version of Maids of Misfortune will be discounted to $5.95 (even less to audible.com members) Saturday August 25 to Sunday September 2.

August 8, 2012

My brief experiment going off KDP Select: At least I got this nifty blog piece out of it!

So…

I lasted only a month off of KDP Select. It was an eye-opening experience. I knew that I would lose sales on Amazon without the borrows and KDP free days to keep my books visible on the historical mystery bestseller lists, but my hope was that I would be building enough sales on Barnes and Noble, Kobo, and the Smashwords affiliates, to make up for these lost sales. I even told myself I was willing to accept lower overall sales for 2-3 months in order to test the idea that having my book on multiple sites (even if the sales on those sites were lower, on average, than on Kindle) was a workable alternative to exclusivity on Amazon, which is what KDP Select requires.

But this was predicated on being able to figure out how to get my books, Maids of Misfortune and Uneasy Spirits, discovered on these other sites, because my experience is that if readers find my books, they will buy them.

But I was not able to figure out how to do this for Barnes and Noble or Kobo and I didn’t see any evidence that this was something I would be able to solve in a short period of time.

As I have written about before, there are primarily two ways a person ends up buying a book (from a brick and mortar store or estore).

They either:

1) come to the store looking for that book (or books by a certain author) or

2) find the books in the store while browsing.

For authors who are independently published and who sell most of their books in on-line stores, social media (blogs, twitter, facebook, pinterest, etc) can play an important role in getting people to go looking for their books. When a potential reader discovers the title of a book through reading a review or an interview with an author on a blog, or reading a tweet or a facebook post from a friend, they may decide to go looking for this book. The more frequently they run across that author’s name or the title of the book, the more likely they are to do so. In addition, social media usually provides direct links to the product pages of estores so that the impulse to look for the book can lead immediately to the decision to buy the book, which increases the effectiveness of this form of marketing.

Social media also has the benefit of costing less money and requiring less clout than the methods traditionally used by authors to market (reviews in print media, book signings, talks at conventions, interviews on radio or tv, mass mailings, etc).

While I don’t believe that the majority of sales I have made have come through my social media activities, I did understand that I might have to work harder to drive people to look for my books in the Barnes and Noble and Kobo stores because they initially wouldn’t have much visibility in these stores. What I didn’t expect was to have difficulty finding places on the internet that specifically targeted Nook or Kobo owners. If an author wants to connect with Kindle owners there are the Kindle Boards, literally dozens of Kindle oriented facebook pages, book blogs and websites that target Kindle owners, providing free and paid methods of promoting your book. I couldn’t find any similar sites that focused on Kobo beyond their official facebook/websites, and the small number of sites that focused on Nook ebooks generally didn’t have many followers. So beyond tweeting using the #kobo or #nook hashtags, I discovered few ways of reaching out and alerting these specific readers that my books were available on their devices.

Which brings me to the other way people find books–browsing. Whether it was in the libraries of my youth, the bookstores of my middle years, or Amazon in my senior years, I discover new authors primarily by looking on the “shelves,” being intrigued by the cover picture and the title, looking at the short description of the book and blurbs, maybe scanning the first pages, and then deciding to take a chance. This is what I want to have happen with my books, and while Amazon’s browsing experience isn’t perfect, for my books, it turns out Amazon is much better than the other two major ebook stores at helping potential customers find my books on their shelves.

I had some hopes for Barnes and Noble because my books had been in this store before and had done moderately well. While I had been disappointed in the total number of my Nook sales, I thought that if I could figure out how to get my books visible in the right browsing categories I could increase these sales. I was particularly encouraged by the fact that Barnes and Noble gives you 5 categories to put your books in (Amazon now only gives you 2), and that they had some smaller sub-categories that Amazon didn’t have where I knew my historical mysteries would shine (like historical romances in the Victorian/Gilded Age, or American Cozy mysteries.) I also know a number of people who sell well on the Nook, although most of them have at least 5 books for sale, usually in a series, and they have been able to take advantage of either the NookFirst program or have used the first book in their series as their loss leader by making the book 99 cents or free (through price matching.) But they also seemed to have their books in the right categories.

However, my plan to make my books be more visible through better category placement in the Nook store failed completely when I couldn’t even figure out where my books were showing up after I uploaded them through ePubit, much less how to get them into the right categories.

Side note: all the Kindle/Nook/Kobo self-publishing systems have the same problem in that the categories you get to choose from when uploading your book aren’t identical to the categories that show up when browsing. See my discussion of this in my post on Categories .

Both the Amazon and Kobo product pages lists a book’s browsing categories, not so Barnes and Noble. When I went to the categories and subcategories I thought my books might be in and scrolled through, looking for my books, either my book would be missing or the pages would freeze before I got through the hundreds of pages, so I could never determine if they were there. Arggh. (And of course this means a potential customer wasn’t going to find them either.)

So, I did what I had done to get my books properly in the right categories on Amazon when I was first figuring out how browsing worked in that store, I wrote the Barnes and Noble/Nook support staff, first asking what 5 categories my books were in and next asking how I could get them into the 5 categories I wanted.

And got no reply. Not even an automated, “we have received your email and we are working on an answer.” Nothing. So I resent my request a week later (mentioning that this was the second request and that I would appreciate some response.) Nothing. So then I wrote the Director of Digital Content, asking if she could direct me to where I could find out the answers to my questions and asking if she could give me advice on how to better market my books for the Nook. No reply.

Bangs head.

I do believe that if I got my books into the right categories that I would begin to have decent sales on the Nook. I am assuming the books I did sell were primarily to those people who went into the bookstore looking for them (based on my tweets and facebook postings), but I don’t think it makes sense to go another month or two hoping I will finally get an answer, and that my books will finally start showing up where I want them to be. I am leaving my short stories up in this store, and maybe I will eventually get these stories into the right categories and begin to get more sales. If this happens and my sales of these stories increase enough on the Nook, I may try again with the full-length novels.

I also had high hopes for Kobo, after reading about their new self-publishing initiative, WritingLife. What was particularly attractive was that they are letting indies price their books at free, without an exclusivity requirement or time limit. But, despite the promise that they had been consulting with indie authors in beta testing, Kobo’s WritingLife is not yet ready for prime time when it comes to browsing categories or free promotions.

I was pleased with the ability to designate three categories on Kobo and my books actually showed up in the categories I put them in. The problem was that these categories are currently very limited. Most distressing from my perspective, there is no historical mystery category (which is the subgenre that is most aligned with my books). Also, if you put “historical mystery” in as a keyword search there were 51,000 books (many which didn’t appear to be historical mysteries), which says to me the search function isn’t very useful as an alternative way for readers to find this kind of book.

The categories my books do show up in the Kobo store (mystery-women sleuths, historical fiction and historical romance) contain a lot of books, with none of the sub-categories that the Nook has, which also makes it difficult for a book by a relative unknown such as myself to become visible in them. I was facing the old chicken and the egg problem (how do you get a book up high enough in a category for people to find it without sales, but how do you get sales if no one ever sees your book?) This is where I hoped Kobo’s free option would help––as it has helped so many authors who have used the KDP Select free promotion option.

However, when I put my short story, Dandy Detects,up as free on Kobo, I found that Kobo has a very ineffective method of making free books visible. While I don’t know how the Kobo ereader itself works, if you are using the Kobo ap there is no way to find free books because there is no way of finding out what books within a category or subcategory are free. This is true for the on-line Kobo bookstore as well.

For example, in Barnes and Noble’s Nook ebook store, if you click on the mystery-women sleuth category, you find 2338 books, and you can order these books by price, with the free books showing up first (15 of them). By the way, my short story Dandy Detect, which should be in this category as a 99 cent book, isn’t there (sigh).

For Kindle, if you look on the device at the best seller list under the “mysteries-women sleuths” you can look at the free list separately for this subcategory, and in the online store you can see the paid list to the left and the free list to the right in this category. Today the free list for this category is 53 books––so it is easy to have your book visible if it is in the midst of a free promotion. Visible not just to people who are looking for free books, but visible to people who are looking at books that are for sale––maybe the newest Anne Perry––and just glance over to the right and notice a free book that looks intriguing.

In the Kobo store, the mystery-women sleuth category (3303 books) can be sorted by price, but the lowest price is 99 cents, so no free books are visible. Instead, you have to click on the free books link on the home page of the estore, a link that is not available on the ap (I don’t know if it is on the Nook itself). Then there are two options. The most straightforward––on the surface––is a link to one of 6 categories, one that is called “Free Mysteries.” But when you click this link only 20 books show up, most of them public domain, and none of them Dandy Detects. Dead end, and frankly if I was a consumer I would try this category once, and never again.

The second option Kobo gives you is to follow these 3 Step instructions

Step 1: Perform a search using any keyword

Step 2: Filter your results by “Free Only” from the pull-down menu

Step 3: Select your download from the search results

This does work, and Dandy Detects did show up under key words like mystery, historical mystery, fiction historical, but the separation from paid books and the browsing categories means that this method isn’t going to produce the traffic that it would get in either the Kindle or Nook stores where there is a connection between the paid and the free listings. In addition, the Kobo method depends on the consumer to come up with the right key words.

I suspect that these problems (no way to find free books through the Nook ap, limited free books under the Free Mystery link, and the lack of connection between paid and free books) have meant that Kobo readers aren’t accustomed to looking for free promotions the way Kindle readers have become since the introduction of KDP Select. Even more frustrating, when I downloaded a free copy of Dandy to my Nook ap I discovered that the dashboard for WritingLife doesn’t report free book downloads so I had no way of knowing if anyone is finding it.

The only evidence I have that a few people eventually found the story (probably because I have been tweeting about Dandy being free) is after a few days a small number of other books started to show up in the “You Might Like” listing on Dandy’s product page. But I don’t know how many copies have been downloaded, I don’t know when they were downloaded (so I can’t connect up with my marketing), and, so far, putting Dandy up for free hasn’t translated into anyone buying either of my full-length novels or even the other short story. I also haven’t seen any movement in the total ranking of Dandy in the categories––so I don’t know if I put it back to paid if it would show up any higher in these categories. In short, at this point the Kobo option of putting a book up for free doesn’t seem to help sell books.

While I imagine that the Kobo techs, who have responded to my questions (unlike Barnes and Noble), will try to solve some of these problems, until they do and Kobo readers get used to looking for free books, I don’t anticipate free promotions being as successful as they are currently on Kindle.

Again, as with the Nook, I will keep my short stories in the Kobo store, keep Dandy free, and see if over the next few months some of these problems are resolved. But I don’t want to continue to let my sales on Kindle stagnate on the promise that the conditions for selling in either the Barnes and Noble or the Kobo stores will improve dramatically in the short term.

So…Back I will go to KDP Select next week, when my books have been successfully unpublished in the other stores, and then I can get back to writing and doing an occasional KDP promotion.

Obviously, I would love to hear if any of you have tips on how to get books in the right categories for the Nook, or have had better success with selling on Kobo. But meanwhile, if any of you are Nook or Kobo owners, my novels will be available for these devices until Sunday, August 12, and my short stories will continue to be there indefinitely.

July 31, 2012

How realistic must we be when writing historical fiction? Victorian San Francisco Mistresses and Maids

I had planned to write about the social structure of Victorian San Francisco when two recent events got me to thinking about the tension historical fiction authors feels between accurately portraying the past and telling a good story. The first event was a mixed review I got for my most recent mystery, Uneasy Spirits. The reviewer suggested my treatment of the relationship between my protagonist Annie Fuller (who runs a boarding house in addition to being an amateur sleuth) and her staff was “unrealistic” because she treated her servants as friends and permitted them to have a Halloween party. The second event was an article in the New York Times Magazine entitled Nannies––Love, Money, and Other People’s Children, which reminded me how little the has changed between the Nineteenth and the Twenty-first century in terms of the problematic nature of the relationships between employer and employee in the realm of “domestic service.”

I had planned to write about the social structure of Victorian San Francisco when two recent events got me to thinking about the tension historical fiction authors feels between accurately portraying the past and telling a good story. The first event was a mixed review I got for my most recent mystery, Uneasy Spirits. The reviewer suggested my treatment of the relationship between my protagonist Annie Fuller (who runs a boarding house in addition to being an amateur sleuth) and her staff was “unrealistic” because she treated her servants as friends and permitted them to have a Halloween party. The second event was an article in the New York Times Magazine entitled Nannies––Love, Money, and Other People’s Children, which reminded me how little the has changed between the Nineteenth and the Twenty-first century in terms of the problematic nature of the relationships between employer and employee in the realm of “domestic service.”

As the Times article pointed out, in modern urban America, economic success depends to a large degree on two incomes, which in turn has meant that many families have turned to nannies to care for their children (and I might add, cleaners to clean their houses and gardeners to keep up the yard). In the Nineteenth century, it generally wasn’t women working that increased the demand for servants, rather it was the new urban middle class ideal of gracious living, characterized by a plethora of consumer goods, multiple-course meals, and well-behaved children, Supposedly this was all made possible by an “Angel in the Home,” a middle class wife sitting firmly on her pedestal and making sure that all was quiet and serene when her hard-working entrepreneurial husband came home. This ideal was only possible to achieve if there were servants.

And, as is true today, there was often an uneasy relationship between the middle class women and the people, usually other women, who worked for them. Some of this came from cultural and class differences and some from a sense of guilt on the part of mistresses, who were handing over what is still characterized as “women’s work” to other women and the maids, who were forced by economic necessity to neglect their own families to do the work of other women.

My critical reviewer was therefore, partially correct. Many, maybe even the majority, of Victorian era mistresses would not have had the same friendly relationship with their maids that Annie did. In fact, one of the characteristics of domestic service in that period was the frequency with which servants, usually young and single, left their places of employment-––seldom staying long enough to develop any personal relationships between mistress and maid. The article on modern nannies made it equally clear that the relationship between mothers and the women who take care of their children can still be less than ideal.

But what the critical reviewer said was that the kind of friendly relationship I portrayed in my book would “not be allowed” and was therefore “unrealistic”–ie not real.

But this would only be true if everyone, now and in the past, behaved the way society says they should, and if there were no exceptions to the norm. But there are always exceptions to the norm, and as any professional historian knows, sometimes we can learn as much about the past from looking at the exceptions as we can from looking at what was “typical” behavior. For example, just as the author of the NYTimes article found nannies that had become valued “members of the family,” there is evidence of servants in Nineteenth century households who worked for families for decades, developing bonds of affection and mutual respect. The question an historian would consider is how exceptional were these examples and what factors explain them. But should that be the main question that the author of historical fiction should consider?

Having been both a professional historian and an author of historical fiction, I would argue that, while historical fiction authors are responsible for portraying the past accurately––no motor cars or electric lights before their time––they are primarily responsible for telling a good story with characters whose behavior the reader can understand and feel sympathy. It is fiction, after all, that we are writing.

I might have given my readers a better idea of the “typical” relationship between mistresses and maids if I had written a story where Annie had a cold and distant relationship with her cook and a story where Kathleen the parlor maid was resentful. However, this would have been an entirely different story, and Annie would have been a completely different character, and I believe the result would not be nearly as entertaining to read.

For example, Annie’s loss of her mother, her odd isolated childhood, her experience with her in-laws as badly treated dependent, all help explain why she would view the motherly cook, Beatrice, as a friend, or feel a sisterly affection for her maid, Kathleen. These relationships help define Annie, make her sympathetic, understandable. In addition, conversations with these servants make the story more dynamic since I can have Annie convey information I want the reader to know through these “friendly” conversations with her staff, rather than have everything come out as interior dialog. Elsewhere I have already addressed why the inclusion of the Halloween Party in Uneasy Spirits was an important plot device. How boring historical fiction would be if it stuck to the narrow confines of what you could prove “actually happened.” I have more than enough footnotes in my past, I don’t need any more.

However, whenever possible I did try to make the information I provided accurate. I made Beatrice and Kathleen Irish, gave the Vosses a Chinese male servant, and had Biddy, a servant in Uneasy Spirits, decide to leave domestic service for a manufacturing job, even though it paid less money, because all these were details based on the facts of San Francisco domestic service (see my blog post on this.)

It also wouldn’t have been historically accurate if I had portrayed every mistress and maid in my books has having had the same kind of relationship. From reading the diaries and memoirs of Nineteenth century domestics I know that some mistresses worked side by side with their servants, sitting down for a cup of tea with them, or asking after the health of their mothers when they came back from a night out, while others didn’t bother to learn their maids’ names, accused them of malingering when they were ill, and exploited them terribly.

In fact, one of the major themes of my first book, Maids of Misfortunes, was the insight Annie got into the life of a domestic servant and how other mistresses behaved (the hard work, the isolation, the snooty up-stairs maid, the uncomfortable intimacy with male members of the household, and the crabby mistress) when she became a domestic servant in order to uncover a murderer. This experience made my protagonist aware of how over-worked her own maid, Kathleen, was and it caused her to hire a laundress to share Kathleen’s workload.

Would a typical mistress be so thoughtful? Probably not. But then how typical was it to have a middle class woman go undercover as a maid? Not very, but that is why it is called fiction. In my choices of how to portray Annie and her relationship with her servants, I kept in mind my audience and the kind of mystery (a cozy––not a gritty explorations of the Victorian underbelly) I was writing.

Interesting side note, twenty years after the period when my protagonist went undercover as a servant, a social worker, Lillian Pettingill did the same thing to investigate domestic service, just as modern day investigative reporter Barbara Ehrenreich did as part of her research for Nickled and Dimed.

Finally, I wonder if authors and readers are holding historical fiction authors to a double standard when they demand complete accuracy, something they seem to do less frequently with contemporary fiction. I say this because the blogs and review comments are filled with discussions of how accurate or realistic historical fiction is or should be, from authors and readers alike. However, I don’t see similar debates over whether or not it is realistic to have circles of cozy quilters all agree to investigate a crime, or have a police detectives solve all her crimes by extracting confessions, or make most fictional private detectives conveniently single without children, so late night stake-outs are no problem. While I suspect that some readers do read contemporary mysteries to learn about the details of police procedures, and I certainly do enjoy learning about places and people and occupations I am unfamiliar with (a small Canadian town with Louise Penny, people living in Alaska with Dana Stabnow, or horse-racing with Dick Francis), I am very willing to suspend my disbelief and assume that they are not writing about those places, people, and occupations with complete accuracy. Yes, as readers we don’t want details to pull us from the fictional world we are inhabiting, but neither should the author agonize that they haven’t made all their characters behave in completely “typical” or “realistic” fashions.

What do you think?

July 15, 2012

Why DIY Publishing is not a Dead End

This morning I read a post by Anderson Porter about a four-piece article written a few weeks in the Boston Phoenix by Eugenia Williamson, entitled The dead end of DIY publishing. I had read the Williams piece earlier, and the more than fifty comments, which in my opinion had done a more than adequate job of pointing out its problems. But when Anderson seemed to accept much of her analysis, and labeled the comments as “the usual pitchfork-waving, spittoon-dinging dismissals, I found myself spending the rest of the morning writing a reply. When I finished, I thought I ought to expand abit, and post what I had to say as a blog, thereby at least justifying a morning lost to writing on my next book. So here goes:

I am a DIY self-published author, who found Williamson’s piece upsetting because it did what so many other pieces have done, alternated between describing self-published authors as a group in dismissive terms and using some of the most unrepresentative examples to prove its points. I am not going to argue that traditional publishing is dead, or that self-publishing is the best or only route for every author to take, but what I am going to do is give you my reasons why I don’t believe that self-publishing is a dead end.

Williams is making 3 points: That publishing is not profitable, that when it is, it is not because of merit, and that it can not provide “the equivalent of research and development: the nurturing of young writers with a first book of short stories as well as critically worthy mid-list authors provide the equivalent of research and best sellers paid for.”

For example, in Williamson’s article she has as a heading the statement: SELF-PUBLISHING ISN’T PROFITABLE, OR MERITOCRATIC. I don’t know how you would interpret this, but I read it to mean that if you self-publish you won’t make money, and if you are successful it isn’t because of the value of the work you produce. As a self-published author who is successful (in this my 3rd year as an author the income I am making per month in sales is well over what I made as a full time history professor), I naturally found the first part of the statement inaccurate and the second point insulting.

Her proof of the first statement is that for every Konrath there are thousands who don’t make any money. This is a meaningless statement since, while I am sure it is true, it is equally true that for every Steven King there are perhaps hundreds of thousands of traditionally published authors who make no money. Writing, at least until now, is not profitable for the vast majority of the people who engage in this activity. If she really wanted to make a statement that added to the discussion, she should have said that self-publishing was less profitable than traditional publishing for the majority of authors. But she can’t say this, not just because the systematic data comparing the two doesn’t exist, but because the increased number of traditional authors who are choosing to self-publish would argue that the statement was untrue.

Since she can’t prove her statement that self-publishing is unprofitable, she instead feels the need to insult those people who do it by suggesting that the authors don’t care if they make money because they “wouldn’t make a dime because no publisher would take them,” or that if they make money, it was only because they had the money to invest in the process because the “truth is self-publishing costs money.”

Then she picks one of the least representative examples of a self-published author she could find–De La Pava to prove this point. Here is an author who published a book and “forgot about it.” How unrepresentative is that! And she mentions that he spent thousands of dollars, which sounds like he used an “authors services” package. If she had either done her research or wanted to paint a balanced view of self-publishing surely she would have taken the time to interview one of the hundreds of self-published authors she could find on the internet (we blog incessantly about our experiences), and mentioned that Smashwords, Amazon’s KDP, and Barnes and Noble’s PubIt, and Amazon’s CreateSpace and Lightening Source have made it possible for authors to publish without that large initial investment.

But no, she doesn’t do that, instead she tries to use this author to make the point that there is no meritocracy in self-publishing because this particular author was successful because he had good luck. The implication is that success has nothing to do with the work an author puts into the writing of the book, or the marketing of the book, or the judgment of the readers, hence the idea that those who are successful don’t “merit” the success. If Williamson had spent just a few hours reading the blogs of self-published authors she would see how much time is being spent on the craft of writing, on learning how to design better books, inside and out, on how to most effectively promote, and on actual promotion, and she might have been able to see how little luck has to do with it.

Finally there is her third point that self-publishing doesn’t nurture young authors through the provision of advances or research and development possibilities the way traditional publishing does. Porter (and many of the authors who commented on the article) pointed out the problem with her assumption that traditional publishing uses its bestseller profits to nurture their midlist authors, so I won’t belabor this point. What I will argue is, that if we are discussing fiction, which Williamson seemed to be doing, the nurturing that authors need the most is a steady predictable income so that they don’t have to work full time at something else, and the research and development they need is marketing data that they can then use to develop new strategies for getting their work to the reader and getting that reader to buy their work.

If you compare the traditional to the self-publishing model, the self-publishing model is anything but a dead end. For the traditionally published author, small advances, spread over 3 or 4 payments, and royalties, that only come 2-4 times a year, mean that most authors have a very insecure and spotty income. It is hard to take the leap to leave your “day job” when your money comes in dribs and drabs and you don’t know from year to year what you are going to make.

In contrast, as a self-published author I see my sales daily, I get my checks monthly, I have sales data for 2 1/2 years and can tell you which months I will make the most money, and which months the sales dip, so I can make my fiscal plans accordingly. Within a year of publishing my first novel, I was making enough money monthly to replace my part-time teaching salary (I was semi-retired), and I retired completely to write full time. As with most small businesses, it may take authors who self-publish years to grow their business to the point of making a living, but I am hearing many more stories of authors finding this sort of sustainable income than I ever heard from mid-list authors in traditional publishing. And with more income coming from ebooks, which don’t have the short life span of print books, this income has a much longer impact on an author’s financial security.

I have every reason to expect that the two books I have published will continue to sell, and that as I publish more books, my income will go up. My traditionally published friends know that in most cases they will never make any money after the advance, and they have no guarantee that the next book they write will ever be published. Which vision of the future would you find more nurturing?

Williams says that if traditional publishing disappeared the only books published would be by those with “the money and the time to publish and promote it.” But if she had done adequate research she would have seen that the initial investments in self-publishing are generally small (mine was $250 for a cover) and can be recouped quickly, and only a small percentage of future profits need to be plowed back into the business on a yearly basis (upgrade websites, professional editing, etc.), and you don’t need to even do that to get out another book, which can then double your earnings.

And for fiction, research and development should mean researching the market and developing good promotional strategies. But again, traditional publishing doesn’t do a very good job of this for most authors. Traditional publishers are just starting to talk about shifting their marketing focus from book sellers to book readers, and most authors are still expected to come up with their own marketing campaigns based on extremely limited data and often years-out-of-date information about where and how their books are selling. Even if they get direct feedback from their fans, they have little control over covers, interior formatting, pricing or promotions. So even if they did their own research, they don’t have authority or mechanisms to use that information to improve the product.

In contrast, because I know every day how many books sold, in what venue, I can mount a promotion, change a price, upload a book into a new book store, and know instantly what the effect of these actions are. I can change a book cover, go in and correct formatting errors instantly, not wait until another edition is printed (if ever). And, as I write my next book, I can take into consideration what 100s of my readers have said in their reviews, not what an editor says based on limited marketing analysis of my mid-list genre.

Just three years ago when I started, it was very difficult to get any information on how other authors were doing with their sales. (Which is why Konrath’s willingness to publish his sales data was so revolutionary!) While there might have been a top down mentoring system among agents, editors and successful authors, there wasn’t the vibrant community that now exists among authors that is open to all. Self-published authors share information readily about what promotions worked and what didn’t. We share information about sales data, how to over come formatting difficulties, what covers work, what fonts to use, and promotional strategies. We open up our blogs to guest reviewers, form cooperatives for cross-promotional purposes. Self-publishing welcomes writers of any age, any background, who write about every subject in every form. Any time spent online looking in Barnes and Noble or Amazon’s stores, or reading writers’ blogs demonstrates that authors are experimenting more than ever before. Short stories, novellas, graphic novels are being published and read that would never have made it through the narrow gates of traditional publishing, which tended to strain out anything that deviated from the recent bestseller trend.

Will some authors fail, or be disappointed? Of course. Will some of these experiments prove unsuccessful, certainly. But, without self-publishing these authors wouldn’t have gotten the chance to fail, and many others, like myself, a former academic in her sixties, wouldn’t have ever gotten the chance to succeed.

I would love to hear from those of you who have had experience with both traditional and self-publishing and examples of nurturing you found in both.

June 23, 2012

Victorian San Francisco: Domestic Service

If you are going to write mysteries, as I do, set in urban America in the 19th century, servants are going to play a role, and so it is not surprising that you will find servants as important characters in my Victorian San Francisco mystery series. However, as I have mentioned previously, my purpose for writing this series, besides providing entertainment, is to illuminate the kinds of occupations held by women who had to work during the late 19th century. Maids of Misfortune, my first book, therefore was intended, from the beginning, to introduce the reader to the world of domestic service, the most important job young women had in the 19th century.

In fact, it was while I was doing research on my doctorial dissertation on working women in the west that I found a diary by Anna Harder, a San Francisco German servant, that provided the inspiration for Maids of Misfortune. Anna, like most live-in servants, got one night out a week. In one of the houses she worked, when she returned early in the morning from that night out she would find the door to the kitchen locked. So she sat outside, week after week, knowing that when someone would finally wake up and let her in that she would have a terrible morning trying to get caught up with her chores. As I read her diary entries I couldn’t help but think of the classic locked-door mysteries of the past, and the idea for Maids of Misfortune was born.

What follows is some background on what domestic service was like for the young San Francisco women who held this job in the 1870s and 1880s. The information is primarily from my dissertation (Like a Machine) and the article on domestic service that I wrote for the Women’s Studies Encyclopedia (WSE). As with all my historical posts, I hope this will either intrigue you enough to go on and read my books, or, if you have already read them, deepen your understanding of the lives of the characters I have created.

“Although domestic service was not a new occupation, by the mid-nineteenth century the nature of the job had been transformed. Previously, most domestic servants worked for the nobility of Europe and the wealthiest families of America where large, complex staffs of servants had been the standard, and male servants usually outnumbered females.” (WSE) This is the model we see portrayed in T.V series like Upstairs Downstairs, or Downton Abbey.

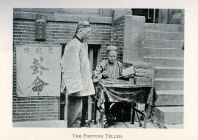

In the Untied States, this model continued to exist for the very wealthy, but the social and economic changes that came with industrialization and urbanization dramatically transformed the nature of domestic service for most. Servants in the United States were no longer neighbor girls of native birth and heritage who were hired by their neighbors as “help,” or members of large domestic staffs for the very wealthy. Instead servants were increasingly found living and working in the expanding number of urban middle class households. These servants were still young women, but they were primarily immigrants, or the daughters of immigrants, with Irish, German, and Scandinavian girls predominating. See these two Scandinavian servant girls.

In addition, unlike the large domestic staff in the first picture, most American domestic servants at the end of the 19th century worked alone, or with no more than one other servant, usually a cook or nursemaid. Servants in San Francisco were no exception, and it was with this in mind that I initially staffed Annie Fuller’s boarding house with two servants, Beatrice O’Rourke, the cook and housekeeper, and Kathleen Hennessey, the maid of all work.

“Ninety percent of the young single servant women in San Francisco, Portland, and Los Angeles were listed as general domestics, and over eighty percent of these young general domestics lived at their place of employment.” (Like a Machine) Their ethnicity followed national patterns as well. For instance, seventy percent of the young single Irish women who lived and worked in these far western cities, like Kathleen Hennessey, worked as domestics.

However, there was an interesting difference in the experience of young domestic servants in San Francisco, when compared to national patterns. Nationally, by 1870 no more than ten percent of domestic servants were male, so very few female domestic servants worked in households with live-in male servants. Yet, in western cities like San Francisco, among those servants who did work alongside another servant, over half worked with a male.

This appears to be in part the result of the demand for domestics outpacing the supply of available women, in a region where men still outnumbered women. At the same time it was in the west that you could find a large group of men, Chinese males, who didn’t have the cultural prescription against domestic labor that most European immigrant men had. As a result, the majority of female servants who worked in households with male servants were working with a Chinese male servant, like the character, Wong, in Maids of Misfortune. See two San Francisco Chinese males from this period.

This appears to be in part the result of the demand for domestics outpacing the supply of available women, in a region where men still outnumbered women. At the same time it was in the west that you could find a large group of men, Chinese males, who didn’t have the cultural prescription against domestic labor that most European immigrant men had. As a result, the majority of female servants who worked in households with male servants were working with a Chinese male servant, like the character, Wong, in Maids of Misfortune. See two San Francisco Chinese males from this period.

Domestic service entailed long hours, being “on call” 24/7, limited afternoon or evening’s out, and a variety of difficult tasks in which many young servant girls had little or no prior training. To make matters worse, in San Francisco at this time nearly two-thirds of these “maids of all work” were the only live-in servant in the house and therefore they cooked, did the dishes, cleaned, did the laundry, mended the clothing, and cared for their employer’s personal needs, as well as tended the children, all by themselves. And, unlike Annie Fuller’s servants, they often did so for mistresses who looked down on them because of their ethnicity, class, and religion and often treated them, in the words of the servant Anna Harder, “Like a machine or an animal.” (Like a Machine)

It is no wonder that young women, like the servant Biddy O’Malley, in my second book, Uneasy Spirits, would often take jobs in factories or as seamstresses that actually paid less than domestic service because they “would rather ‘starve genteely’ making neckties than work as a servant.” (Like a Machine)

Maids of Misfortune is, in large part, my attempt to honor all those women who scrubbed the floors, tended the babies, cooked the meals, and made a comfortable middle class life possible for so many urban Americans in the Victorian period.

Maids of Misfortune will be free on Kindle for two days only: June 23-24, take advantage of this last free promotion of the summer. Look for Maids of Misfortune to become available through Barnes and Noble, and Smashwords, in the next two weeks.

For futher reading on this subject you might want to read the following two new books on the subject: Unprotected Labor: Household Workers, Politics, and Middle Class Reform in New York, 1870-1940 Vanessa May, University of North Carolina Press, 2011; or Making Care Count: A Century of Gender, Race, and Paid Care Work, Mignon Duffy, Rutgers University Press, 2011

“ Like a Machine or an Animal: Working Women of the Far West in the Late Nineteenth Century,” University of California: San Diego dissertation, 1982

“DomesticService,” Women’s Studies Encyclopedia

June 17, 2012

What was San Francisco like in 1880? The Economy

This is the first in a multi-part series describing San Francisco in 1880. For those of you who have read either Maids of Misfortune or Uneasy Spirits, or my short stories, this will provide you with some deeper understanding of the city where my main characters, Annie Fuller and Nate Dawson, lived as children in the 1860s and returned to as adults in the 1870s. If you are not familiar with my Victorian San Francisco mystery series, I hope these historical pieces will pique your interest––although I promise my fiction is much livelier reading. All the material quoted below is from my thesis, “Like a Machine or an Animal: Working Women of the Far West in the Late Nineteenth Century,” University of California: San Diego dissertation, 1982 pp. 60-69.” I must say, it is much more entertaining to convey historical information through fiction than heavily footnoted fact!

Part One: The San Francisco Economy

“In 1880 San Francisco, with a population of 233,959 residents, was the ninth largest city in the United States. Located at the end of the peninsula that separates the Bay of San Francisco from the Pacific Ocean, this city of hills, sand dunes, fogs, and mild temperatures had been only a small village called Yerba Buena less than forty years earlier. This small village was one of the chief beneficiaries of the incredible influx of people into the region after the discovery of gold to the north in the winter of 1847-48.”

[For those of you who have read Maids of Misfortune and Uneasy Spirits––Annie Fuller, her parents, her Aunt and Uncle, and her housekeeper, Beatrice O'Rourke, were among those who traveled west and settled in San Francisco in those first years.]

“Commerce dominated San Francisco’s economic structure through out the nineteenth century. Its fine natural harbor and its location near both ocean shipping lanes and interior river routes stimulated much of the city’s early economic growth. The city served as the port of entry for the massive flow of people and goods into the region during the Gold Rush, and once agriculture developed in the interior in the 1860′s San Francisco also became the major port to handle goods shipped out of the region. The disruption in trade resulting from the Civil War further promoted the development of agriculture in the Far West, and San Francisco merchants worked hard in the 1850s and 1860s to ensure that all goods entering or leaving the region passed through their hands. By and large they were successful, and their control of the region’s trade remained firm until the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. As late as 1875, San Francisco still handled at least ninety percent of all the goods leaving the state and a major share of the trade leaving the Northwest.”