M. Louisa Locke's Blog, page 11

October 2, 2013

Cozies, cats, and a giveaway

Today I start on a 7 day Cozy Book Tour, and I am visiting Melissa’s Mochas, Mysteries & More with a post entitled Can it be a Cozy without a Cat (or a Dog)? This post expands upon the ways that my Victorian San Francisco mysteries are cozies. Please come on over and leave a comment so you can participate in the giveaway of a print or ebook copy of Maids of Misfortune.

M. Louisa Locke, October 2, 2013

October 2 –

Mochas, Mysteries and More - Guest Post, Giveaway

October 3 – Brooke Blogs – Review

October 4 - rantin’ ravin’ and reading – Review, Guest Post, Giveaway

October 5 – Shelley’s Book Case – Review

October 7 – Books-n-Kisses – Review, Guest Post

October 8 – Cozy Up With Kathy – Interview

October 10 – Christy’s Cozy Corners – Review, Giveaway

September 27, 2013

Victorian San Francisco Mystery Series––Cozy-style

When I first published Maids of Misfortune, book one in my Victorian San Francisco Mystery series, I placed it in the historical and women sleuth mystery categories on Amazon. Since the book was set in the Victorian era, and the main protagonist was a woman who acted as an amateur sleuth, this was perfectly appropriate. At the time there was no “cozy mystery” sub-category in the Kindle store, and I didn’t use this term as a key word because I tended to think of cozy mysteries as contemporary mysteries with some sort of theme: like baking, quilting, or cats. To a degree, I wasn’t wrong, since when Amazon created the cozy mystery sub-category a few months ago its three sub-divisions were: animals, crafts and hobbies, and culinary.

When I first published Maids of Misfortune, book one in my Victorian San Francisco Mystery series, I placed it in the historical and women sleuth mystery categories on Amazon. Since the book was set in the Victorian era, and the main protagonist was a woman who acted as an amateur sleuth, this was perfectly appropriate. At the time there was no “cozy mystery” sub-category in the Kindle store, and I didn’t use this term as a key word because I tended to think of cozy mysteries as contemporary mysteries with some sort of theme: like baking, quilting, or cats. To a degree, I wasn’t wrong, since when Amazon created the cozy mystery sub-category a few months ago its three sub-divisions were: animals, crafts and hobbies, and culinary.

Nevertheless, as I began to understand my audience and discover what people liked most about my books (the upside to reading reviews), I realized that many of them saw the books as cozy mysteries––and that this element was as important as the Victorian setting in explaining the series’ growing popularity.

So, why are my Victorian San Francisco mysteries considered cozies?

The definition of a cozy mystery is pretty consistent. Most commentators agree that the origins can be found in Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple series. The common characteristics of cozies are: the main protagonist is an amateur sleuth (usually female), the sleuth frequently has some connection (often a love interest) with a professional involved with the law (police, medical examiner, lawyer, etc.), the people in the book are part of a small or close-knit community, the main characters are “likable,” and the secondary characters (including animals) provide some sort of comic relief. See Cozy-Mystery List, and Laura DiSilverio’s post.

In addition, there is little graphic violence or sex (and limited profanity) in cozies, and good triumphs over bad, so that, as one author put it, “…when you finish you’ll have a smile on your face.” Nathan Bransford

While it is pretty obvious how contemporary mysteries that feature wacky families and small towns (such as Donna Andrew’s Meg Langston series, Lorraine Bartlett’s Victoria Square series, and Elizabeth Craig’s Southern Quilting series) fit this description, it isn’t as obvious how a mystery about a woman without any family who lived in San Francisco in the late 19th century does.

But it does. Let’s take those common cozy characteristics. My main protagonist, Annie Fuller, is definitely an amateur sleuth, since her main source of income is running a boarding house and giving advice as a clairvoyant, not investigating crimes. Annie also has help from a lawyer (Nate Dawson—her romantic partner) and a police constable (Patrick McGee––her maid’s romantic partner). Like most amateurs, she gets drawn into solving crimes because someone she knows is murdered, in danger, or accused of a crime, and her major attributes are that she is “intelligent, intuitive, and inquisitive.” Nathan Bransford

While Annie Fuller lives in a city, not a small town, San Francisco in 1880 was still limited geographically enough for a person to move across it by foot, and the boarding house she owns provides the same sort of cast of quirky characters that a small village does. These boarding house residents, like the elderly seamstresses, Millie and Minnie Moffet, and Dandy, the Boston terrier, do provide much of the comic relief.

Perhaps even more crucial to determining the “coziness” of my mysteries is their lack of explicit or gratuitous sex or violence. Much of the actual “wrong-doing” happens before the story starts or occurs off-stage. When violence is described, there isn’t a lot of blood and gore. As with other cozies, the solving of the mystery and what it reveals about the characters is more important than non-stop action scenes. This doesn’t mean that there can’t be a sense of danger or even a good fight, but as one of my reviewers once said, you can read my books right before you go to bed and not worry about bad dreams.

The same goes for sex. What I am interested in is the course of the romance between couples not their sexual practices. Since my books are set in a time period when women knew that even the whiff of sexual activity outside of marriage could ruin their reputations or their employment opportunities, I am being historically accurate as well. But even when I write about people who challenge those social mores or I describe a married couple, it doesn’t serve either my plot or my character development to give details about the bedroom, so I don’t.

I remember when I wrote the first draft of Maids of Misfortune in 1989 and an agent shopped it around, one of the common responses by editors was that they weren’t sure how strong the market was for historical mysteries in general, and that they already had one Victorian era mystery. Today, Kindle’s historical mystery category lists 3800 books, and 250 of these are related in some fashion to the Victorian era.

However, the Victorian era, with Jack the Ripper wandering the mean streets of England and poverty, prostitution, and political corruption destroying lives on both sides of the Atlantic, generally inspires a darker view of humanity. For example, Anne Perry’s Charlotte and Thomas Pitt and William Monk series and P.B. Ryan’s Nell Sweeney series are excellent Victorian mysteries, but they are definitely not cozies.

And yet I am not the only reader who enjoys both the Victorian period and the cozy-style of mystery when I settle down for a good beach read or a rainy day in front of the fire, and that may explain why the third book in my Victorian San Francisco mystery series, Bloody Lessons, just published, is already one of the top cozy bestsellers in the Kindle store. (And thanks to all of you who have helped get it there!)

And yet I am not the only reader who enjoys both the Victorian period and the cozy-style of mystery when I settle down for a good beach read or a rainy day in front of the fire, and that may explain why the third book in my Victorian San Francisco mystery series, Bloody Lessons, just published, is already one of the top cozy bestsellers in the Kindle store. (And thanks to all of you who have helped get it there!)

Next week I am going on a Cozy Book Tour, where I will get to expand on some of the reasons my Victorian San Francisco mysteries are cozies–I hope you all will come along!

September 23, 2013

Guest Post at Historical Fiction eBooks

Today I am over at my home away from home at Historical Fiction eBooks but I thought some of you might be interested in my post about When Truth is Stranger than Fiction.

Here is the introduction:

My Victorian San Francisco Mystery series features Annie Fuller, a widow who runs a boarding house, supplements her income as a clairvoyant, and investigates crimes. She fights hard to maintain her economic independence, and this independent streak gets her in trouble and causes personal and romantic difficulties. This is fiction, but it also is laced with historical fact.

On occasion, the factual elements of my books are harder for readers to swallow than the fictional parts. For example, some reviewers, after reading my first book, Maids of Misfortune, complained that my protagonist, Annie Fuller, is “too modern” in her attitude and behaviors. Yet, some of the most “feminist” statements Annie makes are shameless paraphrases of real speeches by real 19th century women.

Other readers found it far-fetched that I had Annie pretend to be a clairvoyant, Madam Sibyl, in order to be taken seriously when she gave business advice. This is why I decided to start half the chapters in my second book, Uneasy Spirits, with the real advertisements that fortunetellers, clairvoyants, and trance mediums put in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1879 — a number of them specifically offering to give business and stock advice.

Conversely, there have been times when something I thought I had made up turned out to have more ties to fact than even I imagined, creating a kind of synchronicity or happy accident. To continue reading, go here.

M. Louisa

September 18, 2013

What does it mean when your characters name themselves?

This week I read an interesting the importance of choosing the right names for fictional characters. One of the points the post made was that authors should avoid doing anything that might bring a reader out of the story, including having names that sound alike.

I first ran into this specific problem when I was about to publish my first book, Maids of Misfortune. Most of you know the story by now: I published this book thirty years after I came up with the plot and twenty years after I wrote the first draft so, as you might imagine, I had grown very fond of the character names I had chosen.

Then one of my beta readers pointed out that two of my main characters, my main protagonist, Annie Fuller, and Annie’s maid, who I had named Maggie, had names that ended in “ie,” and she found this to be confusing.

Well, that was a blow! I certainly wasn’t going to change Annie’s name, so the name Maggie had to go. As the writer, I may have believed that no one could possibly mix up the two characters, but as a reader, I could understand how someone who was being introduced to both characters for the first time could mix them up. So, I decided to turn Maggie into Kathleen (another good Irish name and a salute to Kathy, the reader who had pointed this problem out.) Six years later, I can’t imagine the character Kathleen being named anything else.

A second problem in similar names unfortunately slipped through. In Maids of Misfortune I introduced Mr. Harvey (one of Annie’s boarders) and Mr. Harper (one of Madam Sibyl’s clients) and I keep forgetting which is which when these characters reappear in my later books and stories—so I can imagine how difficult it might be for a reader to keep them straight. Since then, I have started keeping a list of characters names as I create them, changing them ruthlessly if I discover I have inadvertently created a name that is too similar to another.

A second issue is how to treat minor characters names in general. Since a minor character is often on the stage for a short time, I have discovered that I need to be very efficient in making that character memorable. For example, in any given book or short story in the series, the older seamstresses in Annie’s boarding house may not even have a speaking part, or they may only get to say a line or two (which is one of the reasons I finally gave them a whole short story of their own.) Here a name can do that. Miss Millie and Miss Minnie Moffet are hard to forget, because of their names. I also try to choose names that reflect a character’s ethnicity. I don’t have to keep reminding the reader that Beatrice O’Rourke is Irish because her name is the reminder. Interestingly, in 1880, over 74% of San Francisco residents in 1880 were either foreign-born or the native-born children of the foreign-born (from a variety of countries), so it is easy to create different kinds of names.

On the other hand, sometimes I leave a minor character nameless. There is no reason to force the reader to keep a name in their head if the character is never, ever going to appear again. Usually a descriptor like “errand boy,” “other teacher,” “policeman” is sufficient.

At the same time, I don’t want to get into the “unnamed ensign” habit (remember those early Star Treks, when one just knew that a crew member without a name was going to get killed on the next mission.) Giving names to enough minor characters makes it less obvious which of them might turn out to be important later on in the plot and which are really bit players.

Finally, there are the characters who simply announce themselves to me. This happens all the time. Beatrice O’Rourke’s name was just there from the moment I conceived of her over twenty-five years ago as Annie Fuller’s Irish cook and housekeeper. Then there was the occasion when I gave one very minor character in Maids of Misfortune (who had been one of those unnamed minor characters) a speaking part in my last major rewrite. When Annie ushered him into a room, he bowed and said, “I am Ambrose Wellsnap.” And there he was—fully formed, from my imagination to the page, and I wouldn’t have dared give him any other name. It’s a very silly name, and he is a pretty silly character. But I would swear he was the one who picked it, not I!

In Uneasy Spirits, it was the two spiritualists, Simon and Arabella Frampton, whose names just came, without any conscious thought, into my head. And in Bloody Lessons, it was Able Cranston, Nate Dawson’s new law partner. I can look back and speculate that I chose the name “Able” because I wanted the new law partner to be someone who Nate would look up to and learn from (who knows why his last name was Cranston?) But the choice itself was not conscious, nor can I imagine ever changing his name the way I did poor Kathleen’s. He was much too forceful a personality from the start, even though he only shows up in one scene. Then again, Kathleen is now such a real person to me now that I know she won’t ever let me change her name again (at least until Peter McGee gets her to tie the knot.)

Oh, and that reminds me of another problem––what to do with Annie Fuller’s name if (or when) she marries Nate Dawson. But I suspect that is a subject for a whole other post.

So, for the other authors reading this: How do you choose names for your characters? And readers, how important are names to you and do you have any kinds of character names that bug you—and take you out of the story?

September 15, 2013

Bloody Lesson Goes on Sale today.

Available in print and for the Kindle here!

Available in print and for the Kindle here!

Bloody Lessons is the third novel in my Victorian San Francisco Mystery series, and in celebration of this launch I am making the first book in the series, Maids of Misfortune, free on Kindle for 3 days (9/15-17) and discounting the second book in the series, Uneasy Spirits, to 99 cents for a week (9/15-21) on Kindle, Nook, Kobo, iTunes, and Smashwords.

Do tell your friends that they can get the whole series the next 3 days for under $5!

And a treat for those of you who have joined my Facebook author page, I will announce later today a contest with $5 Amazon gift cards as prizes that I will be running over the next two weeks.

Thanks to all of your for your support and now go buy your copy and start reading! Really! I, on the other hand, think I will take a nap.

M. Louisa Locke

September 13, 2013

Bloody Lessons: Victorian San Francisco Teachers–Part Three

This is the final part of my 3-part series on San Francisco teachers in 1880. I hope it helps deepen your enjoyment of Bloody Lessons, the third book in my Victorian San Francisco Mystery Series.

“Who were the women who did succeed in passing their examinations and securing jobs in San Francisco, Portland, or Los Angeles? And, what were their jobs like once they got them? Over eighty percent of the female teachers in these three cities in 1880 were single, and over two thirds of them were single and under the age of thirty. In Portland and Los Angeles, over two thirds of the female teachers had native-born parents. Nearly three quarters of the young single women teaching in (San Francisco) were either foreign-born or of foreign parentage, and a least a third of those who lived at home came from working class families.

“For young single women from immigrant or working-class backgrounds, the possession of a teaching job, with its high pay and middle class surroundings, may have represented a worthwhile improvement in status. Yet cultural strictures against higher education for women could create tensions for some of the young immigrant women who chose this occupation. Rebecca Kohut, who lived in San Francisco in this period, came under sharp criticism from her father’s Jewish congregation when she decided to go to the University of California to prepare to become a teacher. Moreover, the pressure to appear sufficiently ‘Americanized’ or middle class in dress, demeanor, and social behavior could prove a severe strain on a young woman from a working-class or immigrant background.

“Some of the young single women teaching in the Far West who came from middle-class and upper-class families probably saw their work as at least an enjoyable method of filling their time until marriage, or as a way to gain a little money of their own, or perhaps even as a vocation; for others, joining the work force was a matter of necessity. The economy went through periodic downturns in the Far West as elsewhere, and in a time when speculation was rampant, it was not unusual for prosperous merchant of professional to find himself in severe economic difficulties. As a result, daughters mar might suddenly find themselves expected to go to work to help their families survive the temporary, if not permanent reversals in fortunes, Moreover, when a young woman’s father died, her whole family often faced severe economic trials. It is quite possible, therefore, that a number of the young women teaching in the schools of San Francisco, Portland, and Los Angeles in 1880, particularly among those living with unemployed, widowed mothers, were doing so not out of choice but out of necessity. The young women might have seen their jobs as teachers a loss in status, a loss that the ‘genteel’ nature of the job could only partly assuage.

“Along with higher pay and shorter working days, teaching offered advantages over most other forms of female employment because it provided some chance of advancement, even within the smaller cities, Not only could women qualify for higher salaries by getting higher grade teaching certificates or teaching at the high school level, but some women held positions as special school assistants, vice-principals, principals, or even school superintendents, each of these jobs bringing with it an increase in salary and prestige.

“If high wages, shorter hours, and possibilities of advancement constituted some of the major advantages of teaching as an occupation for women, there were difficulties with the job as well. In San Francisco, teachers also faced such problems as outmoded examination systems and meddling bureaucrats, but they faced over-crowded classrooms as well. Throughout the San Francisco city schools in 1879, the teacher to student ration for the grammar and primary grade was 1 to 46, and some schools had as many as 54 students per classroom. In the large urban environment of San Francisco, with substantial numbers of working class and immigrant children attending school, classrooms of this size could severely restrict a teachers’ ability to teach.” Like Machine or an Animal:’ Working Women of the Far West in the Late Nineteenth Century”

As I developed the characters in Bloody Lessons, I didn’t consciously make them mirror the demographics of San Francisco teachers. However, the historical facts probably influenced me. As were most teachers in the nation in 1880, key characters–Nate Dawson’s sister, Laura, and her friend Hattie Wilks–are under the age of thirty, single, and native born of native heritage. At the same time, two of the main male teachers that show up in Bloody Lessons, taught in the higher grades and also had administrative roles as vice-principals, which was the common pattern (then as well as now!). This is why the average salary for men who taught in San Francisco was $50 a month more than the average salary for women.

And while a third of the female teachers in the city were either married or had been married, which was true for the characters Barbara Hewitt and Dorthea Anderson, the attitude that was expressed in the book that somehow a woman with children shouldn’t be teaching reflected real historical attitudes. Teaching was supposed to be the job held by young single woman who were waiting to marry, or reserved for the poor women who never caught a husband and lived the rest of their lives as “old maids.”

When I created Kitty Blaine (who was studying to become a teacher) and decided to make her the daughter of Irish immigrants, I was doing so primarily for plot reasons, but this was another case where my fictional creation was grounded in historical reality. While the national pattern (and the pattern found in both Los Angeles and Portland Oregon in 1880) was for teachers to be of native-born parentage, in San Francisco in 1880, 72% of the young single teachers (like Kitty) were born of foreign-born parents.

I remembered being quite surprised as I analyzed the data for my dissertation to discover how many of the teachers were of Irish heritage. I speculated that since one of the reasons a significant number of young Irish men got police jobs in the city was the dominant role the Irish played in city politics, it shouldn’t be surprising that a good number of young Irish women ended up as teachers.

I would never suggest that an author create a book “by the numbers,” making sure that a certain percentage of the characters fit a particular demographic pattern. But I do think that when you write historical fiction it is useful to be aware of those demographic patterns. Probably only a hand-full of people in the nation would know that Kitty Blaine’s Irish heritage and her desire to become a teacher was historically accurate, but as I created her, knowing she was grounded in reality helped her seem more real to me. And that is always the key. We need to believe in our characters if we are going to make them live in the imaginations of others.

Only two days to go, and Bloody Lessons will be available for sale, September 15. If you want to make sure it is on your Kindle, ready to read, Sunday morning, you might think about pre-ordering here.

September 10, 2013

Bloody Lessons: Victorian San Francisco Teachers: Part Two

In my newest Victorian San Francisco Mystery, Bloody Lessons, the question comes up over whether a teacher got her position through undue favoritism on the part of a school board member. Once again, a plot point came right out of the pages of my dissertation and the newspapers of the time period. And once again, the controversies of the past, in this case over city policies governing the hiring and retaining of public school teachers, echoes controversies in the present.

“No matter what their salary, women highly coveted the job of teaching in the nineteenth century, and by 1880 a position in the California or Oregon public schools was not always easy to obtain. In the 1850s and 1860s a teacher had to go through a yearly examination order to get and to retain her job, and examination that was often given by an incompetent or pretentious person who had little idea of what skills or knowledge made a good teacher. In his memoirs, John Swett, the family California educator, recounted the story of one examination he was forced to take in 1860. The questions that he and other teachers were expected to answer on the topic of geography were the following:

1. Name all the rivers of the globe.

2. Name all the bays, gulfs, seas, lakes, and other bodies of water on the globe.

3. Name all the cities of the world.

4. Name all the countries of the world.

5. Bound each of the states of the United States.

“These teachers had graciously been given an hour to complete the answers to all five questions!

“In the 1860s, California passed state legislation, as did Oregon at a later date, that somewhat rationalized the system of certifying teachers, that law stated that examinations would be administered by professional educations. This took care of some of the abuses within the system, but the process was by no means standardized, and the quality of the applicants given certification still depended greatly on the varying quality of teh state, county, and local boards of examiners.

“For men and women wishing to become teachers in the Far West in 1880, no matter what their educational background, getting a teaching certificate represented no easy task. In 1879 63 percent of the nearly 600 persons who took the Los Angeles and San Francisco county certification exams were rejected. Moreover, passing the examination remained only the first step to securing a job as a teacher. A woman then had to get a local school board to hire her, and there is strong evidence that within all three cities in this period getting a position as a teacher depended a good deal on who she was and whom she knew.” Like Machine or an Animal:’ Working Women of the Far West in the Late Nineteenth Century”

The late Victorian period in U.S. history was called the Gilded Age in part because of the corruption within national politics, particularly at the city level. Elected officials used their control of city jobs (police, fire, etc) and lucrative business opportunities (contracts to provide municipal services and construct public roads and buildings) to extort money and votes from city businesses and residents. The public school system proved no exception and as a result there was great competition between the parties over who was going to get elected to the local School Board. In turn, these officials were suspected (probably accurately in some cases) of misusing their power to award contracts to build schools for the expanding population, award textbook contracts, and hire teachers and administrators for their own political and monetary gain.

Two headlines from the 1879 San Francisco Chronicle reflect both the question of whether the examination system for teaching certificates was fair, and whether or not teachers were being hired entirely on merit:

“…Board of Education Special Investigating Committee, met in the Supervisors’ Room at the new City Hall and heard testimony in the matter of the anonymous letter heretofore received by the Committee insinuating that Miss Susie Jacobs, at teacher in the public schools, had obtained her certificate by means of having had previous access to the question being asked at the examination.”

“THE INCOMPETENT TEACHERS: Not only influential politicians, but prominent churches and benevolent societies had insisted, he said, that their favorites and protégés should be provided for in the School Department, irrespective of their Qualifications.”

We may never know if these accusations were true, but clearly, for many women, a teaching position in the 1880 San Francisco public school was worth fighting (or cheating) for. One of the reasons for this was it was one of the few positions that gave any chance of advancement, financial independence, and was considered “respectable.” Part Three will examine who the women were who succeeded in getting these jobs in 1880.

M. Louisa Locke

Bloody Lessons will be available September 15, 2013 in print and Kindle ebook, you can still pre-order here.

September 6, 2013

Bloody Lessons: Victorian San Francisco Teachers–Part One

From the start, my plan for the series of mysteries set in Victorian San Francisco has been that each book should feature a different occupation held by women of that period. In Maids of Misfortune, my protagonist, Annie Fuller, goes undercover as a domestic servant, in Uneasy Spirits, she investigates a fraudulent trance medium, and in my short story, The Misses Moffet Mend a Marriage, the elderly seamstresses who live in Annie Fuller’s boarding house are on center stage. In Dandy Detects, it is another boarder, Barbara Hewett, who is the main protagonist.

And it was while I was developing her background story, including her work as a teacher at the city’s Girls’ High, that I decided that my next full-length book after Uneasy Spirits would be about the teaching profession. In less than two weeks, that book, Bloody Lessons, will be published, and for those who like to know more about the historical background of my fiction, I am going post a multiple-part series on San Francisco teachers in the late 19th century. Most of this material is drawn from my dissertation, ‘Like Machine or an Animal:’ Working Women of the Far West in the Late Nineteenth Century and the San Francisco Chronicle.

And it was while I was developing her background story, including her work as a teacher at the city’s Girls’ High, that I decided that my next full-length book after Uneasy Spirits would be about the teaching profession. In less than two weeks, that book, Bloody Lessons, will be published, and for those who like to know more about the historical background of my fiction, I am going post a multiple-part series on San Francisco teachers in the late 19th century. Most of this material is drawn from my dissertation, ‘Like Machine or an Animal:’ Working Women of the Far West in the Late Nineteenth Century and the San Francisco Chronicle.

“Less than ten percent of all the women working in San Francisco, Portland, and Los Angeles in 1880 held jobs in the professions, and over ninety percent of them were teachers. Fifty years earlier school teaching had been dominated by men; women had begun to join the profession in significant numbers as full-time teachers only in the 1840s, and yet by 1880 over two thirds of the teachers in the United States were women.

“There were several reasons for the increasing importance of women in this profession in the period. The spread of the common school movement, which worked toward the establishment of public schools, had produced an accelerating demand for teachers. Men, who had traditionally taught in the public and private schools of the nation, could no longer adequately fill this demand, at least not at a price that the small budgets of public schools could handle. As a result, the hiring of women as teachers at lower rates of pay seemed a practical solution to the problems facing financially-strapped communities. Catherine Beecher, one of the earliest promoters of women as teachers stressed the advantages of accepting female teachers, writing at one point, ‘…women can afford to teach for one-half, or even less, the salary which men would ask…’

“Whether or not this view was correct, just as the demand for female teachers rose, there was an increasing number of women available and eager to meet this demand. The middle-and late-nineteenth century witnessed the expansion of institutions of higher learning for women, and more women were attending high schools, normal schools, and colleges. Teaching was a logical outlet for those women who wished to do something practical with their learning before settling down to marriage. At the same time, the middle classes were beginning to view teaching as a more respectable occupation for young women. The historical debate over the negative and positive effects of the ‘cult of domesticity’ still rages, but it is clear that activities, like teaching, that could be easily identified as an extension of maternal or domestic roles became more accepted pursuits for women in this period. Women who taught, particularly if they taught in the elementary grades, were seen as simply applying (or practicing) their maternal talents outside the home.”

“Western school boards hired women as teachers for all of these reasons. Urban leaders in the Far West felt that it was imperative to provide up-to-date institutions in their cities to prove that their region was a modern as the East. With rapidly growing populations, however, it was often difficult to secure the funds necessary to set up good public school systems. All three cities witnessed battles over the issue of school funding in the 1850s and 1860s; hiring women seemed an acceptable solution to these problems in the Far West as well.

“Even after the passage of a California law in 1874 that states, ‘Females employed as teachers in the public schools of this State, shall in all cases receive the same compensation as is allowed male teachers for like services, when holding the same grade certificates,’ the average salaries of women teaching in California were substantially lower than those made by males. For example, in 1879 a woman’s average monthly salary of between $70 and $80 was $50 a month less than a man’s. The ineffectiveness of the state law explains this differential in part, but the fact that women were usually limited to teaching in the lower-paying, elementary and primary grades while men were more likely to hold jobs as administrators of high school teachers explains most of the difference.” – ”‘Like Machine or an Animal:’ Working Women of the Far West in the Late Nineteenth Century”

While I knew the general outline of the problems facing women teachers from my dissertation work, the research I did last year in preparation for writing Bloody Lessons proved extremely enlightening. A search of the San Francisco Chronicle for 1879-1880 exposed the fact that in December 1879, just a month before Bloody Lessons opens, the newly elected city school board, in an attempt to cut the costs of public education, slashed the salaries of the primary school teachers––in some cases cutting their monthly salaries in half. Previously, a teacher’s salary was determined by the grade they taught (lower grades, lower salary), supplemented by the number of years teaching experience they had and what level of teaching certificate they had obtained through a statewide examination. Now, the base salary of primary school teachers base was lowered and their experience and training would not be taken into consideration.

This decision was made by a slender majority of the School Board, and it caused an uproar among the teachers and their supporters, culminating in a mass meeting held December 21, in the Metropolitan Temple (the large Baptist church founded by Rev. Isaac Kalloch, who had just been elected mayor of San Francisco.)

Teachers, principals, and the board members who had voted against the measure spoke out against the cut in salaries. Over and over, women testified that the new salary of $46.50 a month was not enough for a woman to live on, stressing that many of them were either entirely self-supporting or, even worse, were the sole support of widowed mothers. (My own study found that 30% of the women in San Francisco who held teaching jobs lived at home with unemployed parents–reinforcing the women’s testimony.)

They also argued that the new method of calculating salaries would drive the most experienced teachers out of the city’s public school system––or force them to refuse positions in the primary school grades.

However, it was clear from the Board’s decision to cut salary of the teachers in the lowest grades the most (and another proposal to have unpaid Normal school students substitute in these grades), that these men had accepted the common rational for paying women less––that women were simply exercising their natural maternal instincts with young students––hence their experience or education shouldn’t count.

Several of the teachers and principals directly addressed this idea in the mass meeting, one stating that “…the real work lies in the primary grades, where the groundwork for the pupil’s education is formed…” while another said, “Little children of six to ten years of age much be studies and carefully handled, and it is only after years of experience that any teacher can successfully cope with the difficulties of a class of very young children.” San Francisco Chronicle, December 22, 1879

The Board did not step back from its decision, causing one young woman to suggest that the teachers go out on strike, and in March a bill call the Traylor Act passed the state legislature rolling back the salary cuts. Yet, when the law’s constitutionality was questioned the Board withheld these teachers’ entire pay until halfway through the next summer, causing great economic difficulties for teachers and those how who depended on their income. San Francisco Chronicle, July 29, 1880

As a retired teacher, I must say I found this battle over teachers’ salaries distressingly familiar, echoing the recent controversies and cut-back facing public school teachers throughout the nation. There was even an “Anti-Tax Pledge” that all the Republican School Board members had taken during the previous election that had prompted the cut in salaries.

However, as a novelist, I couldn’t have been happier. I wasn’t going to have to invent a sense of crisis among my characters, it was already there, waiting for me to discover and turn into a mystery plot as I wrote Bloody Lessons.

M. Louisa Locke

Bloody Lessons the third book in my Victorian San Francisco Mystery series is due out September 15 in print and ebook on Kindle, and it is available for pre-order here.

August 30, 2013

Day in a Life of an Indie Author

In the countdown to publication of Bloody Lessons, my days are filled with the work of getting the final draft formatted, proofed, and ready to upload for both print and ebook. At the same time I am also working on lining up various promotional activities, including writing more frequently for my blog. Yesterday, as I thought about the various tasks I had to do, it occurred to me that some of you who aren’t self-published authors might find it interesting to get a glimpse into what a the day in the life of an indie author is like. You will notice that no writing (except for this blog) went on, but I did put in an 8 hour day. (And it is days like this that make it clear to me that I didn’t retire, I just launched a new career.)

In the countdown to publication of Bloody Lessons, my days are filled with the work of getting the final draft formatted, proofed, and ready to upload for both print and ebook. At the same time I am also working on lining up various promotional activities, including writing more frequently for my blog. Yesterday, as I thought about the various tasks I had to do, it occurred to me that some of you who aren’t self-published authors might find it interesting to get a glimpse into what a the day in the life of an indie author is like. You will notice that no writing (except for this blog) went on, but I did put in an 8 hour day. (And it is days like this that make it clear to me that I didn’t retire, I just launched a new career.)

5 A.M.: Woke up early and started thinking about my to-do list, which I knew was fairly formidable.

6 A.M.: Edited and published the weekly post I do for the Historical Fiction Authors Cooperative (HFAC) that lists what free promotions, discounts and new publications there are among the members. I am the chair of the HFAC Board of Directors and one of my primary responsibilities is coordinating our weekly post by members and putting together and publishing this weekly promotional post.

6:30 A.M.: Spent the next hour reading and responding to email (most of it from HFAC members).

7:30 A.M.: Breakfast–read some blog posts I subscribe to (I always look forward to the Business Rusch on Thursdays––and the post today was the difference between having a writing career and being a one-book writer, which seemed very timely given the day I have before me. There was also a long thread going on David Gaughran’s blog about comparing Smashwords and Draft2 Digital that I had commented on the day before, so I was getting all the rest of the comments in my email.

8:00 A.M.: Shower

8:30 A.M.: Spent the next hour compiling a PDF copy of Bloody Lessons (I finished editing the book yesterday) using Scrivner. This meant tweaking margins, getting rid of places where a chapter ended with just a few words at the top of a page. It took me 5 different test runs to get it right. Final book is 323 words for a 6 x 9 trade paperback. This is my shortest book, but it still tops 110,000 words.

10:00 A.M.: Wrote to my cover designer the total page number for the print version and attached back cover copy so she can produce the cover for upload on CreateSpace. If she gets it to me tomorrow I will upload and order a proof copy.

10:15 A.M: Consulted by phone with a writer in England over what his next step should be in his marketing (he just finished a 3 day KDP Select free promotion of his thriller Cry of the Needle.)

10:30 A.M.: filled out a questionnaire to submit to Great Escape Virtual Book Tours for a book tour for Bloody Lessons in October

11:30-1:30 Lunch and meeting with friends (only part of the day not working)

1:30 P.M.: Worked on this post and updated my website because Uneasy Spirits has just gone up on Kobo, iBooks, and Barnes and Noble stores (I used Draft2Digital this time, which was why I was interested in the thread about comparing to Smashwords.)

2:00 P.M.: Read email and more blog posts, and read the New York Times

3:00-4:30 P.M.: Saw that Maids of Misfortune had 499 reviews on Amazon and decided to go on my facebook author page and offer an Amazon gift card to the person who wrote review 500. Also assembled a list of potential reviewers for Bloody Lessons and sent out 5 email requests. (Got a winner almost immediately for the FB challenge and already received one yes from the 5 book reviewers I queried.)

4:30 P.M.: Finished up reading blog posts and worked a little more on this post

5:00-6:30 P.M. Dinner and British cop show on TV

6:30-6:45 P.M.: New email to read–HFAC has members from all over the world, so the email traffic goes on all day. I sent the winner of the 500th review a gift card and did some retweets.

9:00 P.M.: Checked my sales numbers and worked a little more on this blog post.

9:30 P.M. headed up to bed.

So, as you can see, this was a busy day. I am not complaining. While I prefer the months when a large proportion of my day is spent actually writing, without the kind of work I did today, the stories wouldn’t get out to the public, and I wouldn’t have the satisfaction of knowing how much people enjoy reading about Victorian San Francisco and Annie Fuller and Nate Dawson and the whole crew of people in the O’Farrell Street boarding house.

COUNTDOWN TO BLOODY LESSONS LAUNCH: 16 days

You can pre-order print and Kindle editions here.

August 28, 2013

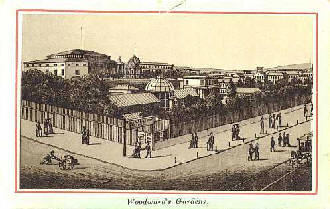

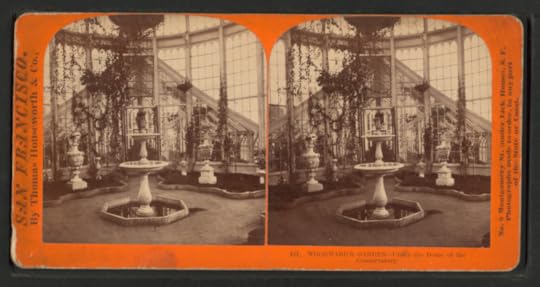

Victorian San Francisco: Woodward’s Gardens

In the countdown to the publication of Bloody Lessons, I am going to explore some of the places in I have let my characters visit in my Victorian San Francisco stories. For some of those places, you can still visit and experience what they would have been like in the late 19th century, for example, the famous Cliff House Inn, while others are so long gone that it is hard to imagine how important they had been to residents of San Francisco in the past.

Woodward’s Gardens is one such place. In 1879-1880, when my novels are set, Woodward’s Gardens was the preeminent place for San Franciscans to go to recreate–even more popular than Golden Gate Park, which was just still a good deal of sand dunes, newly landscaped carriage drives and a single Flower Conservatory.

However, today, if you go to look at the four city blocks between 13th and 15th street and Mission and Valencia where the Gardens used to be located, you will see a rather pedestrian mix of commercial and residential buildings, overshadowed by an overpass of U.S Route 101. There is a restaurant with the name Woodward’s Gardens, and an historical marker, but nothing else is left to remind you of the what used to be so famous.

What was most disconcerting to me when I visited this neighborhood this winter was how flat it was. As you can see from the pictures above, when Woodward’s Gardens existed, it was far from flat. Clearly, at some point, I expect when the overpass was built, these four blocks were leveled and all signs of the Gardens were lost. I rather felt like I had gone to Disneyland and found that it has disappeared.

In its heyday, Woodward’s Gardens was the former mansion and grounds of Robert Woodward, a man who came to San Francisco during the Gold Rush in 1849 and made his fortune running a popular hotel, The What Cheer House (where no alcohol was served!). Woodward loved collecting (artwork, curios, plants, and animals) during his extensive travels, and in the 1860s he started to turn his home into an amusement park for the city.

The entrance fee was 25 cents for adults, and 10 cents for children, and the grounds contained museums, art galleries, plant conservatories, an aquarium, a zoo, a performance pavilion, and a restaurant. It had the largest roller-skating rink on the west coast, a circular boat ride, and hot-air balloon events. Pretty much something for everyone, young and old alike.

Located in walking distance of the working class neighborhoods south of Market, and reached by frequent horse cars that funneled riders from the business and middle class residential districts north of Market, Woodward’s Gardens was relatively inexpensive, conveniently located, and because it was alcohol-free, it was considered a respectable place for young men and women to go courting.

In my first Victorian San Francisco mystery, Maids of Misfortune, the Gardens are mentioned as a place where one of the suspects goes on her day off and it figures in the question of whether or not she has an alibi (for the curious, check out Chapter 26). In Uneasy Spirits, my two main protagonists, Annie Fuller and Nate Dawson, meet there after several months’ separation, and I had particular fun having them stroll through the Conservatory and the Marine Aquarium (Chapter 15). In Bloody Lessons, I have a whole group of people from Annie Fuller’s boarding house make a day of it at the Gardens, and this time it is the zoological gardens that sets the scene (Chapter 16).

If you would like to get a better visual sense of the Woodward Gardens, do check out my pinterest board, and this website is particularly detailed in its description of the place. But of course, you can always just read my books!

COUNTDOWN TO BLOODY LESSONS PUBLICATION: 18 days.

You can pre-order both print or ebook on Kindle, here.