Regina Doman's Blog: Regina Doman's Updates, page 5

July 23, 2019

20 Things You Can Do For Those Who Are Grieving

This is a post I wrote nearly ten years ago on my son Joshua Michael's website. Since the website is currently offline and so many people keep asking me for it, I thought I would post it here. If you're one of the many people who posted links to the list years ago, I hope you can update the links. Thanks!

This is a post I wrote nearly ten years ago on my son Joshua Michael's website. Since the website is currently offline and so many people keep asking me for it, I thought I would post it here. If you're one of the many people who posted links to the list years ago, I hope you can update the links. Thanks!My husband and I would like to share some things that people did for us when Joshua died, things which we think might be helpful to do for others who are grieving. When tragedy happens, sometimes it is difficult to know what to do, yet many of us just want to do something. When our son Joshua died, so many people astonished us by the helpful and gracious things they did that we want to share them with you. They are some answers to the question of ‘What’: What can we do now? (the question Fr. Benedict Groeschel recommended we ask instead of ‘why.’)

Some of these things are easier to do for close friends or family, but others can be done for acquaintances, neighbors, or even total strangers who have suffered a loss.

1. Go to the funeral, if there is a funeral. I don’t think I ever realized how much that means until Joshua’s funeral. When my husband’s aunts from the Midwest walked in, aunts who had never visited Virginia before, I was overwhelmed. If you can afford it, if you can make the time, go. And if you can’t, send flowers or cards. If you are a close family member or friend and are able to step up to the plate, you could offer to handle the various details of the funeral, cemetery, hospital, or whatever it happens to be that is needed. Our brothers and sisters took over so many details about the hospital, funeral, insurance, a rental car so I wouldn’t have to drive, the cemetery and other things. This freed us up to be with our children and to spend time grieving, praying, and thinking about Joshua. We were so grateful for this.

2. Visit – if not at the time of the tragedy, then later. At the time of the tragedy, sometimes grieving families are overwhelmed by numbers of well-wishers. So the phone call, visit, or letter that comes six weeks later, six months later, after the hubbub has died down can be of particular importance. One thoughtful thing some of my friends who visited did was to make a point of writing their cell phone numbers on my fridge door so that I could call them whenever I needed to talk. Just looking at the numbers on a daily basis reminded me that they were there if I needed them.

3. Bring up the cause of mourning in open-ended, sensitive ways. As time goes on, the grieving person can feel as though no one else remembers the loss. It is constantly on their mind, yet they dread bringing it up, feeling that they’re just throwing cold water on whatever light conversation is going on. One mother who lost her infant told me, “I feel as though I’m a walking Death’s Head every time I walk into the room.” Feeling unable to speak about their loss can make grieving people feel so isolated. But there are ways you can let them know that you haven’t forgotten, that their loss is on your mind. I appreciated the person who said, “I was just thinking of you the other day,” or “I remember how Joshua used to do so-and-so; you must miss him,” or even just, “I’ve been praying for you.” If I wanted to talk about Joshua or about how I was feeling, this gave me an opening. But if I didn’t want to talk, it was still good to know that others remembered.

4. See what it is they might need. Friends from our church organized meals for us. A local church sent over boxes of disposable plates, cups and silverware the day after the accident. How did they know that we would be hosting a lot of guests, and that we might not feel up to washing dishes for a while? It was the perfect assist. And in the days following the accident, when I felt mostly numb, one thing that broke me into tears was learning that spontaneously, people had started taking up a collection to buy us another vehicle, so that I would no longer have to drive the suburban that hit Joshua again. Thanks to the assistance of so many people, we were able to buy a new used suburban on Ebay, and we were able to donate the old suburban to another family.

5. Get your group involved. If you are part of a group, such as the Knights of Columbus or the Legion of Mary, encouraging your group to make a contribution in some way to a suffering family can mean a lot. I don’t exactly know how to articulate this, but grief can make you feel so lonely: to have a group of people acknowledge your grief by helping can be strangely healing. The Knights in our parish not only held a fundraiser but also sent out some men to clean our yard, help do some outside seasonal chores to get us through the summer, and did some little fix-ups such as fixing our screen doors. But one thing I will mention is that it’s important to ask the family what they most need: sometimes a visit to the family’s home will bring to mind suggestions. For example, after visiting us, another Knight and his family asked if they could buy us air conditioners, since they noticed our house, which was undergoing renovations, didn’t have central air at the time. But doing chores without asking the family first can lead to some unexpected consequences: the friends of one family who had lost a child came in one afternoon and cleaned the entire house. The grieving mother was grateful, but she confided to me that months later she still hadn’t found things that were moved during the cleanup. So asking first is always the best.

6. Make concrete suggestions. “Is there anything you need?” is an often-heard question which can be difficult for a grieving person to formulate an answer to, because many times, they’re not sure what they need. So coming up with a concrete suggestion: “Could your family use someone to mow your lawn this month?” is really helpful. That way, the grieving family has less thinking to do.

7. Consider helping with finances. When Joshua died, Andrew’s brother Mike who lives near us immediately took over all financial arrangements. He and his wife even paid all our bills until the funeral was over, keeping careful records so that we could pay them back when the dust had cleared. Obviously this was only something a close family member could do for us, but we appreciated it. Gifts of money are usually welcome, since a death often means unexpected expenses or just a tendency to put everything on the credit card and sort it out later. If the family isn’t in need of money, asking them if they would like donations sent to a particular charity as a memorial is sometimes a welcome suggestion.

8. Send pictures. So many people dug up and sent us framed pictures of our son Joshua that they had snapped at weddings, parties, and other events. Having these photos meant a lot. One part of my grief at losing Joshua was realizing that we had no family photo that contained all of us together with Joshua and our new baby. For a long time, I quietly mourned over this. So it was with amazement that at Thanksgiving, we received two huge gold-framed portraits of our entire family with Joshua at my daughter’s baptism. They were sent by fellow parishioners who had been attending another baptism at the same time, and just happened to have snapped a photo of our family. They had the photo enlarged, then had a separate enlargement of Joshua holding my hand cropped out of the photo, and sent that in a matching frame. They had no idea how much this gift meant to me.

9. Remember the kids involved. Children work out their grief differently from adults, but they need special attention too. Relatives invited our children to come to their homes for special visits after Joshua died. Another family sent our children gift cards to a local toy store, and much to our children’s delight, they have repeated their generosity on Christmas and a month ago, on Joshua’s birthday. It gave us something to do to celebrate Joshua’s birthday, which our children were adamant about celebrating, and they were touched that it now seemed as though Joshua were buying birthday gifts for them.

10. Let them know you are praying. Have a Mass said. Offer a spiritual bouquet. Simply pray. We know that one reason our family has survived is the prayers of so many. There is no other way to explain how we have gone on without taking into account the power of prayer.

11. Send a grieving basket. I don’t know if this was an original idea or not, but my husband’s relatives sent us a lovely basket filled with comforting and soothing things: a prayer book, a scented candle, homeopathic calming drops, a journal for memories of Joshua, lip balm, quality tissues, massage oil, herbal tea bags, a crystal “hope” ornament, and a cuddly teddy bear that one of our children immediately adopted. We kept the grieving basket on our sideboard and used it whenever we needed it. Our children particularly loved helping themselves to it. It was so thoughtful.

12. Remember holidays. Christmas is always difficult for those who’ve experienced a tragedy, and I had a difficult time this Easter, when all the readings were about an empty tomb, and I was aware of a tomb that remained full. Father’s Day or Mother’s Day can also be painful. Offering to spend time with a family during those hard times or just sending a card or gift can be a real Godsend.

13. Send or make a prayer shawl. I found out about the prayer shawl ministry, a group of women who create shawls “knit with prayers” for grieving families. I received one of these beautiful shawls from a group of women in Pennsylvania, and my children love having it. One daughter constantly sleeps with ours, and I know I have snuggled up in it from time to time.

14. Recommend a bereavement program for children. Friends told us a local hospice had a free bereavement program, and we enrolled our children in it. They were able to make lovely memory boxes for themselves and it was good to have something they could go to that was just for them.

15. Send or make a memorial bracelet. On Joshua’s birthday just a few weeks ago, I received the most wonderful package. Kimberlee, a mother who makes jewelry, rosaries, and bracelets with her company Beads of Mercy (www.beadsofmercy.com) had created a gemstone memorial bracelet of Joshua for me. She had spelled out Joshua’s name in silver alphabet blocks, and attached charms for things that Joshua had loved the best: a knight in shining armor, a hammer, and a tiny train. She also added a small crown for the crown of glory in heaven, and a crucifix and Miraculous Medal. I was so touched by this.

16. Memorialize or remember the family’s loved one in a public way. When Joshua died, a local children’s theater group dedicated their performance to him, and later on, our local ballet school did the same with their Christmas Nutcracker performance. Some people have donated money or copies of my book Angel in the Waters to crisis pregnancy centers in Joshua’s name, which moves me. It seems as though Joshua continues to do good, even though he’s no longer on earth. That’s such a healing thing for us, and I think it would bless other grieving families as well.

17. Visit the gravesite and leave something there. We visit Joshua’s grave every Sunday we are home, and when we have found flowers or cards there from others, it’s very moving to us.

18. Help the family remember. I found I needed to do something positive in memory of Joshua in order to survive, and I’m told that this is a common way for families to turn their sorrow into something positive. At Christmastime our family decided to collect teddy bears in Joshua’s honor to donate to poor mothers. Friends and relatives made that possible. When we expressed a desire to start a small scholarship at Joshua’s nursery school, others came forward to help us. Something as simple as offering to help a grieving family plant a memorial tree can be welcome.

19. Remember the anniversary. Cards, phone calls, and emails a year later mean a lot. On the anniversary of Joshua’s death, we were out of town: my sister was having her new son baptized James Joshua Hernon, and asked my husband and me to be the godparents. So friends of ours asked if they could visit Joshua’s grave for us the day of the accident and pray for us. Of course, we were honored.

20. If you have experienced a similar tragedy, don’t be shy about expressing your sorrow, even if the people involved are strangers. My worst fear had always been hitting someone else’s child with my car. I never dreamed I might hit my own child. I didn’t think I could live with myself. But after the accident, one thing that meant so much to me was letters and emails from other parents who had accidentally run over their own children with their cars. I could not believe their vulnerability: that they would share their shame with me, that they would reach out to me and urge me to forgive myself. I don’t know their names: some of the cards were unsigned. But those letters meant the most to me, and I thank God for them.

Published on July 23, 2019 17:05

February 5, 2019

Building Creative Coalitions in a Polarized Culture

I gave this talk this past summer to a group of Catholic writers gathered for the Catholic Writer’ GuildLive Conference in August of 2018. To find out more about the Catholic Writers' Guild, click here.

I’m by nature an agreeable person. As the oldest of ten strong-minded children, I’ve had to learn to be even more agreeable to get anything done. Even though I have strong ideas of my own, Catholic family life taught me how to get along with those with whom I strongly disagreed. Even after we each, by the grace of God, had our respective conversions, this didn’t mean that we suddenly saw eye-to-eye on everything. Even today, we dearly love each other but we disagree. I am saying this to eliminate the wishful thinking of, “If my sister would just convert, then surely she would agree with me!” “If my brother would just follow Church teaching I’d find it so much easier to get along with him!” I have news for you: it just might not work that way. Having Church teaching on your side no longer becomes the personal deal breaker that it once was. Disagreements will still happen, and might get worse!

This should not surprise us, although it often does, because we forget that good and evil are very different. Goodness is creative and can take many different forms. Evil is the same old, same old, pathetic nonsense rebaked and resugared for another round of rot. Goodness ultimately comes from God. And it is God Who makes saints. He rarely makes them agree. If you compare the saints – not the one-paragraph summaries in the Liturgy of the Hours or their same-height-same-weight statues in a religious goods store – you will find that they vary vastly. And often when they lived at the same time, and even were attacking the same problems, they didn’t agree. The correspondence between contemporary saints is educational in this respect: and often hilarious! The flame wars of Sts. Augustine and Jerome. Philip Neri chiding St. Ignatius. The followers of Dominic and Francis bickering. If you give a problem to ten holy people, you are likely to get ten different solutions. This is not because of sinful human nature or pride: it’s just the beautiful variety of goodness that God creates. Because all goodness comes from God, the source of all goodness, and in every age and in every culture, the Holy Spirit raises up new ways of being good and of doing good.

As creative professionals in the Catholic world, we have to remember this, especially when working with other Catholics. You’ve come to this conference because you want to help build the culture of life: good! You want to network and learn and work with other Catholics to work towards the same goal: good! Let the disagreements begin!

As we all know, so much of work in Catholic community is “sandpaper ministry.” We get our rough edges rubbed off, our pet peeves polished, our OCD and personal preferences and the hills-we-thought-we’d-die-on smashed into a glimmering sheen of pearl. And this is how it should be. I just read the most brilliant article ever on Christian community by the virtually-unknown Thomas D. Dewey. It’s so good that, with your lenient patience, I’d like to quote from the article at length. The article, just so you know, is “10 ½ Rules for Christian Community” posted at The Catholic Thing.

God did not place us alone in this world but in the presence of others, starting with our families, working outwards, then – as He commanded us – loving our neighbors as ourselves.We’ve all heard that commandment innumerable times, but has it ever occurred to you to ask why it is so essential to our salvation to love our neighbor? After all, God could have ordered the world in other ways, including solitude for billions of souls.St. Catherine of Siena wondered about that too, and asked God, who told Catherine that what He most desires is for us to love Him as He loves us. That may sound straightforward, but it is impossible for us to love God as He desires to be loved without the presence of other human souls.Because for us to love God back is mere justice. We did absolutely nothing to deserve a single day of life, much less an immortal soul and the possibility of Heaven. When we love God directly, we are acting justly, but also in our own interest because of the promise of greater happiness on Earth and the mega-prize of eternal happiness after death. But, there was nothing in it for God when he loved us into creation. His Divine love is gratuitous and disinterested, whereas our love for Him is fitting and self-interested.So, in order to give us the opportunity to love divinely, He placed us among other souls whom we could love without any prospect of reward. We can only love God the way He wants us to by loving other people who cannot benefit us.And that is the reason why Christian Community is so important: communities are a target-rich environment for us to love selflessly. Forming Christian Community – communities of fellowship, brotherhood, and Christian charity – isn’t a nice optional thing to do after work. It’s why we are here.Thomas D. Dewey, “10 ½ Rules for Forming Christian Community,” posted at THE CATHOLIC THING.ORG on July 28, 2018

Community is necessary even for us independent minded solitary writer and artist types. Of course we know we have to make *some* community if we want to get published or get read. But if you’re one of those who struggle to connect faith, life, and work, this realization that we can’t truly love God and fulfill our purpose on this earth without loving others – and that working as creatives gives us opportunity to love others – can be a remarkable simplification and harmonization. I’ve said before that to be a great writer, you have to love lots of people: not just observe and study them, but love them, love them with that ‘tough love,’ ‘if not for the grace of God there go I’ identification. Nothing else really creates great writing like that grappling in love with the human condition. So in the end, there is no contradiction between becoming a great writer and becoming a great saint. We just often lose the forest for the trees.

The reason I picked this topic is because we live in time of polarization. I’m not naming names or political parties, but this has been a very confusing and frustrating time for Catholics. This past political season saw the splintering of many traditional coalitions that left some of us spinning and friendless, both on and offline. And the amplification of the Internet hasn’t helped things, to speak with very mild sarcasm.

Polarization is dangerous. I believe this strongly. It may happen accidentally, but it’s also a power tactic used deliberately in fomenting political revolution and agitation, and in seeking to arouse public partisanship and anger. The idea behind polarization is that you identify, freeze, and personalize a target, painting the person(s) in the blackest of hue, in order to isolate them and create polarization. This is done with the understanding that, when conflict happens, the great mass of people will fall back and stand silent, leaving the field clear. Then the fight can begin. The goal of the fight is to produce an extreme reaction: in military terms, to generate an atrocity: in personal terms, to get the person so mad that they do or say something “unforgivable,” to turn the masses against them – and hence towards the side of the instigator of the fight.

During this stage, one tactic that is deliberately used is to “kill the moderates.” This means to neutralize or ridicule anyone who is capable of making peace, of bringing the two sides together, of preventing the polarization which is the goal. This is why moderate Muslims and Hindus get assassinated in troubled countries. This is why political organizers recommend to “GET RID OF THE DO-GOODERS IN YOUR ORGANIZATION”—those with moral sense to question means. It’s a deliberate technique. Once revolution is underway and a grab for power is within your reach, why not bump off those who are capable of maintaining the peace?

Peace is perilous and must be renewed daily. Confronting evil while maintaining peace requires wisdom. Since all wisdom is seldom found within one person, I suspect Our Lord splits up the charism among several different people, seeing to it that some do just the right amount of bold confrontation while others do just the right amount of merciful forgiveness. Then the barque of Peter stays upright in the end.

So where do creatives come into this?

Most of us, I suspect, are fairly open-minded: that’s what makes us creatives. I believe it is also what specially equips us to be peacemakers and moderates in the culture wars.

1.) We tell stories. We make art. If we are doing it right, we are creating stories and art that everyone can enjoy, not just those of our party. Everyone loves a good story. Use that to bring people to the table together.

2.) We can empathize. If we are really telling our stories right, we are getting inside the villains and understanding not just how they think but realizing that we too are villains, or could be – except for the grace of God, as Chesterton’s Father Brown explains in The Secret of Father Brown (another Google). If we can understand and identify with a sociopathic villain, surely we should be able to understand and identify with an annoying sister-in-law or a infuriating parish council member. Next time you’re stuck with a blank page, try making that sister-in-law or parish council member or whoever else is irritating – excuse me, is sanctifying you – these days the hero or heroine of your novel and who knows? They might just smash through your writer’s block and you might just come to appreciate them more for their hidden talents.

3.) We have to get along with a lot of very different people in order to succeed. This includes editors, marketers, book reviewers, and of course, readers. We have to be a bridge. Use that bridge to help some of those others to get along with one another.

So what does this mean? Being a bridge, bringing people together, and so on?

It means that at your book signings, online enemies may come face to face. Use the opportunity to make peace. Technology makes polarization more inevitable because it inhibits shame. The physical experience of shame, as my friend Dr. Mary Stanford points out (in her article on Technology and the Language of Bodily Presence – google it) inhibits us from saying the angry or lustful things that we might say in someone’s presence. Technology erases those inhibitions, making us more vulnerable to sinning when there’s a screen between us. Be aware of that, and double down on the politeness and etiquette as a counterbalance. Use phrasing from Downton Abbey if it helps. “May I kindly ask you – and I know you would normally agree with me – to not swear on my page. Please delete that comment. Oh, thank you so much. You are too kind.”

It means choosing your battles very wisely. Let the political battles go, but not the doctrinal ones (how often we switch that!). If you do disagree, bring up what you have in common. Ask favors of those who hate your political stances. “Could I ask your advice on a good tagline?” Ben Franklin, no Catholic or moral example but a wise student of human nature, noted that those whom we ask for help are more inclined to think of us agreeably than those whom we ourselves help: they may resent our generosity.

I already mentioned social media fans. One thing that must characterize us as Catholics – and I say MUST – is relationship repair. I mean: forgiveness. If we can’t forgive and repair relationships, why the heck are we doing any of this? I mean, the whole point of our faith is that God forgave us in the person of Christ Jesus, who was crucified by us and for us and who forgave us. If we can’t forgive, we are failing at being Catholic on the most basic level possible. What that means is that you forgive them. You don’t have to trust them again – you’ve been forewarned and forearmed – but despite what psychology says, you and Christ can give them a second chance. Christ gave second chances. Forgiveness also means that you don’t gossip and backbite, but that you look them in the eye and you work with them again. It means you pick up the phone when you get an email you’d rather screenshot. It means you meet face to face and work it out if you have to. Maybe you can’t work it out, maybe you can’t ever work together again, but you can at least part ways in Christ. Don’t neglect that bit. In my mind, that’s what separates the real Catholics from those of us who just came for the party and stayed for the wine. So yes, forgive those who cheat you, who don’t return phone calls, who break contracts, who gossip about you, who screenshot you, who vent about you online. And recommend to others that they do the same when others hurt them. We want to be smart and protect our hearts – but we can’t forget to be Catholic in the midst of this. It’s who we are. It’s who we should be.

A word on gossip. It kills community faster than anything else I know. Don’t let it grow in your heart. Don’t let it grow in your garden. Shut it down when your friends start it. Say, “Let’s bring Sally into this conversation instead of talking about her.” “Oh, no? Then why are we talking about this?” Gossip destroys trust, especially among women, and we women are so much of the glue that holds communities together. Don’t do it. Vent alone to God or to a handwritten journal you can burn afterwards. And don’t commit anything to the Internet that you wouldn’t want published in the New York Times. We’re professionals: we should know that online communication is legally PUBLISHING.

I believe in the power of the Theology of Bodily Presence – or as I termed in, the Theology of Locality. That when Christ said the second part of the Greatest Commandment was to love your neighbor, He meant it. Who is my neighbor? Christ made it clear in one of His most famous stories: the scumbag in front of you on the side of the road is your neighbor. In other words, you are called by God to love the people who are physically present around you. And being in the physical presence of those people often helps you love them. Which is why in this world of virtual everything, we Catholic writers have a live conference, because bodily presence is essential to true Catholic community. Think about it: Christ set up the Church so that there never could be an online sacrament. There cannot be. The sacraments themselves require bodily presence. There is grace and power in that.So come to these conferences and take the opportunity to meet those you disagree with online. Get to know them, for real. Have a beer with them. If you’ve fallen out, use this conference as a moment to ask forgiveness and put that relationship repair Christ died for into practice. There’s grace unlocked by that. And yes, forgive the publisher who didn’t give you a book deal. Forgive the fellow writer who got that book deal that you wanted. Go up and shake hands and wish them well, and try to mean it. I know well how we writers are so prone to envy: ours is a lonely profession at times. But the grace is offered, if we will take it.

Enter the creative coalition. If you sense polarization and tribalism taking hold, the way to counter it is to build a creative coalition. A coalition is made of people who have one goal – and not much else – in common. Our old ones are splintering. The pro-life movement was a political coalition among people who began with very little else in common but who all agreed that babies shouldn’t be murdered in the womb. It has been a quarreling, bickering coalition from the start, and far from perfect, as members often don’t have anything else in common – religion, political affiliation, or temperament – which is one reason why the pro-life movement convulses when anyone suggests that another issue be added to the coalition. The goal of the pro-life movement was to build a generational movement that would survive long enough to fight abortion after the original founders were dead. It’s going to need to be a fight for the centuries. We often forget that the abolitionist movement was similarly chaotic and fractious and members had almost no agreement on politics or religion or even tactics. But it did succeed in keeping a movement alive from the missed opportunity of 1776 to 1865. I’m not saying the pro-life movement can’t change and widen to include, say, the death penalty – it did widen to include euthanasia and assisted suicide and help for crisis pregnancy. But it was always a coalition of very different individuals and you don’t change millions of minds in a heartbeat. And we would be foolish to suppose that the internal bickering will come to an end: but we can be more patient if we get a better sense of the animal that we are looking at and just how intractable it might be.

So make a coalition. Even a specifically creative one: let’s get together and found a novel series. Can I tap you to work on an independent film with us? If a relationship is fraying, find what you do agree on and work together on that. It’s hard to shoot the cow that gives the milk. These are the sort of things that can hold a society under threat together.

We hear a lot about tribalism. Now, I’m a Gen Xer. We’re the ones who love our friends. I like tribes. We’re awash in this sea of isolating technologies including things that isolate us subtly like the automobile that allows family and parishes sprawl beyond proximity, or AC that keeps people inside in front of screens during heat waves instead of sitting in the shade of porches and trees. So it’s natural that when we find those with whom we naturally mind-meld, we want to form a tribe. I get that. But tribes can become gangs, and gang warfare is never pretty. So we need to season tribalism with a generous amount of “both/and.” After all, the Israelites were twelve tribes, and the Lord God … never made an issue of it. But He did lay down that the moral law was to be extended to everyone, not just members of their own tribe. So I concur, let there be tribes. But charity is more important. And charity often means etiquette, a minor handmaid of charity, which allows us to communicate with non-tribe members in a respectful and coherent manner. You may be tired of saying, “Agree to disagree,” but you should keep on saying it.

A second way to build a coalition is to make peace and compromise on those issues that divide but which ultimately get in the way of unity. I’m looking at those of us who are barricaded in the ongoing Liturgical Wars and the even vaster battlefield of Liturgical Music. We Americans LOVE our music. We are the first generations with the ability to listen to our music whenever we want. The problem is that we all go to Church together. My solution: take the fight outside, guys. Who made the rule that Catholic music has to be in the liturgy or else it’s not real? There are other places to make music outside the Mass. There are concerts. There are campfires. There is Eucharistic adoration. There are processions. There is music to listen to around the house and on earbuds. If you love traditional music but your liturgist just won’t agree, organize an event outside the Mass where you CAN play traditional music. Same if you love contemporary Catholic music and your liturgist loves the organ. Let’s bring more music into the lives of our fellow Catholics: but let’s quit making the sole battlefield of success the Mass. And remember that while we can personalize our playlist, none of us should try to personalize the liturgy. If you’re living with someone else’s personalized liturgy, might as well offer it up on the altar of Christ’s sacrifice. That, as I recall, is kind of the point. But my point is that your natural allies in another cause might just be that hippie wielding a guitar or that Traddie fitting a pipe organ into her catapult – put down the weapons down, guys … slowly. There are bigger issues at stake just now.

Same on the matter of intentional communities versus “Catholic culture.” This is a broad war but breaks out periodically in frustration on many different fronts. Some Catholics channel their spiritual energy into building apostolates or communities of various kinds while others channel their spiritual energy into their own souls and minding their own business. The two types tend to misunderstand each other, very much so, because their approach to what seems to them the basics of the faith manifests so differently. The latter group is often more articulate, and the first group is often too busy and maxed out actually building Catholic community to respond coherently. I am a fan of both groups, but my sympathies are with the builders. So for example, I disagree with Ross Douthat, who recently opined in his latest book, “Conservative Catholics are better at building bunkers than evangelizing the culture.”

This is a common misperception. Building community isn’t building a bunker. Although I can see how the two things can be confused. So let me explain.

There are those who will attack or mock any attempt at intentionally creating a Catholic environment as striving for an unattainable perfection or cowardice in the face of a secular challenge.

I want to remind you that there is a difference between a hothouse and a greenhouse, however similar the structures themselves may look.

Both are “artificial environments” where malevolent or detrimental outside influences are consciously excluded. Both are run by gatekeepers who choose what can enter and what must stay outside. Both have walls that let in light and keep out the rest.

But one, the hothouse, is designed as a lifelong support system: the other is a training ground. One tries to cultivate dependency: the other to foster independence. But they look nearly the same, except for the intention.

In the same way, a Catholic environment that shelters souls too weak or exotic to face the outside world and a Catholic environment whose rules and practices and criteria are designed to allow the young to grow strong and healthy, ready to go out into the world and preach the Good News, might have similar rules, criteria, and practices. But the intention is entirely different. And being accused of sharing characteristics with a hothouse does not invalidate or do away with the necessity of creating Catholic greenhouses. And we need those, more than ever: for the young, for the broken, for those resting after battle.

If you are a fan of “Catholic culture” but are down on “Catholic apostolates,” or “Catholic communities” or can’t stand “those puritans who start screaming if they read a Catholic book with sex and swear words and who won’t buy my novel,” take a hard look at those you oppose. Are they building a hothouse or a greenhouse? You may think you know, but perhaps your perception is determined by temperament. If you’re familiar with fantasy, perhaps that “puritan” who won’t buy your book isn’t representative of her group: perhaps she’s just a gatekeeper. Gatekeepers, like police, need to make hundreds of micro-decisions as part of their job. They red-flag broadly to make their (very exhausting) job easier. Talk to the person behind the gatekeeper and they may be far more lenient and reasonable. Even gatekeepers can be brought to see context and reason. And a gatekeeper who comes on your side – especially if others in her group agree with you – can become your diehard fan.

So don’t write off an entire group or apostolate because of a bad experience with one or two of the members. Greenhouse building is absolutely crucial to building Catholic culture. A greenhouse may be turning into a hothouse – that’s always a possibility, but definitely not an inevitable one. Good healthy communities like good healthy families tend to be invisible. They do their jobs, they get out of the way, they never make the news or go viral – they just do what they’re supposed to do. And as a writer, you should find a healthy greenhouse and join it: the Catholic Writers’ Guild is one. So let’s not insist that all greenhouses are hothouses. The Catholic Church has been in the greenhouse business for millennia – religious communities being the flagship model, but there have always been smaller ones, from the first Christian commune in the Book of Acts to the women’s Bible study groups of the first century that became the first Catholic schools to the men gathered for prayer and silence in the desert who became monks to the charitable groups of women who founded the first hospitals – and the list goes on and on.

The easy days of living in a Catholic culture where you could go to Mass and just “be Catholic” are rapidly evaporating in the secularizing forces of today. We do need Christian community. We need more greenhouses: for the arts, for the professions, for Catholic education, for every section of Catholic work. If you want to just sit back and “breathe the Catholic air,” you’re going to need a greenhouse full of Catholic plants to do it. Go and see how you can help. We all need rest from the battle. We all need healing. We need sandpaper ministry. We need to be challenged to love the God who saved us by loving our neighbor, including our annoying Catholic co-patriots who “just don’t get culture.” And we all need to think about and care for the next generation of Catholics – both the young baptized and those outside the Church who need to be evangelized into Christ. The harvest is plentiful. Laborers are few. Where does Christ want you? Ask Him.

The Christian life resembles a vast dance around a central figure, the central figure being Christ. We all need to be connected to Him. The more of us are deeply converted – the stronger our connection to Him – the more people can join in the dance. Our job is to keep hurling our dance partners towards Christ and being hurled towards Him in turn. That’s Catholic culture.

And I’ll close with a word on hope. Polarization in our society is deeply troubling. We need to combat it intelligently by keeping civility, a sense of humor, wisely picking our battles, confronting evil wisely, but recognizing complexity and not rushing to demonize those who disagree. We need to model being a grownup for the young people in our lives. How can we criticize them for their screenslaving if we turn into uninhibited barbarians on Facebook? Sometimes the future can look bleak, and we are creatives, so when our dystopian imaginations get going, the future can look REALLY bleak. This can make us feel that any attempt at coalitions or creativity or charity is futile. This is what I’ve been asking myself lately.

Do I believe in the triumph of the Immaculate Heart? We don’t often think of Fatima as a hopeful vision. It’s often confused with apocalyptic thinking. But Our Lady’s message at Fatima was not about the end of the world. As she described the future conflicts that would engulf our centuries – and she totally nailed it, totally – she said, “But in the end, my Immaculate Heart will triumph. Russia will be converted and an era of peace will be granted to mankind.” Notice this is not one of her “if” statements. “if you pray the Rosary, if you make reparation… then …” It’s a “this is going to happen, regardless.”

So when I get discouraged, I ask myself, “Do I believe in the triumph of the Immaculate Heart? Can I work for that triumph? Can I work for that era of peace? Maybe I won’t see it, but maybe I can help others build something that will.”

Pray for it. Work for it. And write on.

Published on February 05, 2019 11:02

January 23, 2019

Update and IAM New books

Update and IAM New books

Dear friends,

I just wanted to give you a brief update about my writing. For the past year, I've been working on a new project called the Culture Recovery Journals. The first installment was published in Soul Gardening Journal, a journal for mothers by mothers, which I hope you will all consider subscribing to. I'm hoping to have the article, "A Theology of Locality," out as a book sometime this spring. I'll let you know how it goes! In the meantime, we continue to work on our homestead, I continue to teach high school English, and work on my long-awaited new novel series. I'm closer to finishing it now than I have been before, and I credit your prayers for the progress.

Peace and good

Regina

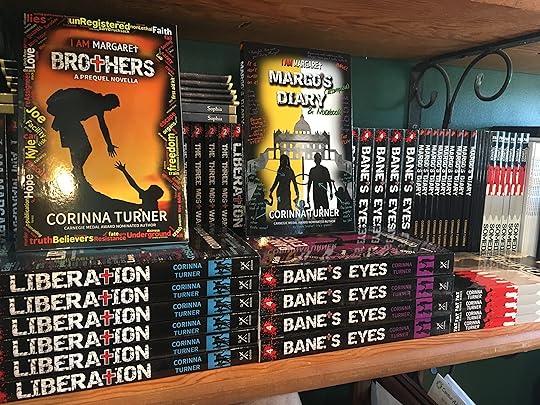

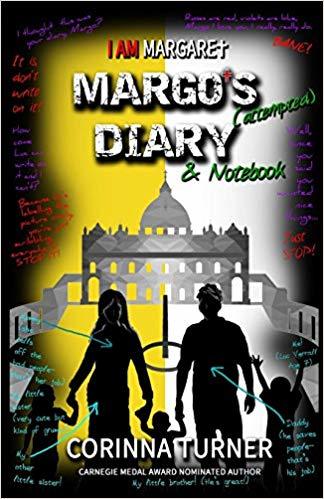

I AM MARGARET RETURNS!

MARGARET is back...with more books!Since we stopped carrying I AM MARGARET, the suspense-filled dystopian series by British Catholic author Corinna Turner, we've had requests for where to find the books. The new answer is, back at Chesterton Press! We have the entire I AM MARGARET series, together with a new book and a new novella by Corinna. Check it out!

MARGARET is back...with more books!Since we stopped carrying I AM MARGARET, the suspense-filled dystopian series by British Catholic author Corinna Turner, we've had requests for where to find the books. The new answer is, back at Chesterton Press! We have the entire I AM MARGARET series, together with a new book and a new novella by Corinna. Check it out!

Related productsTwo brothers must escape the EuroBloc...or die. A prequel novella to I AM MARGARET.View similar products »

Related productsTwo brothers must escape the EuroBloc...or die. A prequel novella to I AM MARGARET.View similar products »

New Novella!Now that the Vote is over, Margo ties up some loose ends and shares some fun bonus material.Buy it now»

New Novella!Now that the Vote is over, Margo ties up some loose ends and shares some fun bonus material.Buy it now»

Published on January 23, 2019 18:10

December 12, 2018

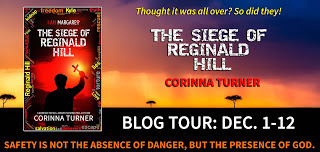

New Novella: The Siege of Reginald Hill

An odd surge filled my heart as I looked at him, sitting there in that chair: so old; so evil; so broken; so... alone. A warmth. A caring. A... love. I loved him. Just another poor sinner who need my care...SAFETY IS NOT THE ABSENCE OF DANGER, BUT THE PRESENCE OF GOD.Fr Kyle Verrall is living a quiet life as a parish priest in Africa when he’s snatched from his church one night by armed assailants. He’s in big trouble—his sister’s worst enemy is hell-bent on taking revenge on the famous Margaret Verrall by killing her brother, just as slowly and horribly as he can. What could possibly save him? The humble young priest is defenceless—or so Reginald Hill believes.But Kyle has a powerful weapon Hill knows nothing about. And he’s not afraid to use it.Is Reginald Hill really the hunter?Or is he the hunted?Buy the book at IamMargaret.co.uk

An odd surge filled my heart as I looked at him, sitting there in that chair: so old; so evil; so broken; so... alone. A warmth. A caring. A... love. I loved him. Just another poor sinner who need my care...SAFETY IS NOT THE ABSENCE OF DANGER, BUT THE PRESENCE OF GOD.Fr Kyle Verrall is living a quiet life as a parish priest in Africa when he’s snatched from his church one night by armed assailants. He’s in big trouble—his sister’s worst enemy is hell-bent on taking revenge on the famous Margaret Verrall by killing her brother, just as slowly and horribly as he can. What could possibly save him? The humble young priest is defenceless—or so Reginald Hill believes.But Kyle has a powerful weapon Hill knows nothing about. And he’s not afraid to use it.Is Reginald Hill really the hunter?Or is he the hunted?Buy the book at IamMargaret.co.uk

Published on December 12, 2018 03:54

October 30, 2018

It's about the Victims, not Tribalism

This is a post from Oct. 30, 2008, in the wake of the first testimony published by former US Nuncio Archbishop Viganò who called for the Vatican to reveal who was responsible for protecting and elevating abusers such as the former cardinal, Theodore McCarrick. I combined two of my posts and published them here today.

Life in America has been getting pretty tribal, probably thanks to my generation, the Gen Xers who love their friends over all else, including our Facebook friends. Catholics have always been tribal, and it’s tempting to put tribe over all in most situations. But this situation--the McCarrick crisis and Viganò’s revelations--are a moment when we need to look beyond tribalism and beyond Americanism. Catholic is a global religion and this is a universal family crisis, and rooting out this corruption needs all of our voices. Why? Because of the victims. The predator McCarrick didn’t quiz his victims on their orthodoxy, liberalism, or political views. He was an equal-opportunity predator who degraded his victims without regard for our precious tribal loyalties. Those who shielded him from Church discipline were equally unconcerned.Some of you are discounting Viganò because he’s from the wrong tribe -- in this case, conservative, insofar as a diplomat can be considered to fit into any American categories. But who are the other few heroes in this mess so far?

An ex-priest liberal investigator who never gave up digging, over decades of being ignored. An ex-Catholic contrarian journalist who wouldn’t let go of the story. And the courageous victims who went on the record, most of them ex-Catholic, some of them openly gay, but sick of the lies. And the fringe journalists of the traditionalist wing who told the truth to mostly-deaf ears and were thrown out of the Catholic mainstream in response. That’s an odd coalition, worthy of a Hollywood screenplay. Most of these people were in nobody’s tribe. But they told the truth. And they were right. My friend Rebecca Bratten Weiss said that in this mess of confusion, she is clear on one thing: standing with the victims. I agree. Now is not the moment to shoot down a courageous witness because he’s from the wrong side of the aisle. He’s backing up the victims. He’s throwing us information we can use. Don’t stop listening because you “don’t trust the source.” The question now is the same question that motivated these independent marginalized investigators. The question we should all be asking, “But is it the truth?” If it is, we have to follow up on it. Together. I have had enough of false prophets who prophesy, “Peace, peace. Policies are in place. The future will be different.” But the victims still mourn. Are the perpetrators and their protectors still in power? When will justice be done, in Christ’s Church? We need to fight for the Bride, our Mother Church. Because no matter what our tribe, we are all her children.

The whole point of the testimony of Archbishop Viganò is to obtain justice for the victims. The timing is significant. After the McCarrick revelations, the media and the laity were justifiably asking, “Who allowed this predator to continue in office?” Pope Francis and the Curia took away the cardinal’s hat from McCarrick but did NOT open an investigation to find out. In fact, the week of August 20th, in his “Letter to the People of God,” Pope Francis indicated that the ONLY plan he had was to offer prayers and condolences for the victims, but he was not going to look into why the scandal happened. His letter would have been the perfect juncture to open an investigation, but the Pope did not. This papal statement of Aug 20 was apparently what impelled Vigano to speak out on Aug 22. Viganò is a nuncio, a diplomat. Discretion and secrecy is the hallmark of their profession. If diplomats told everything they know, wars would never stop. So a good diplomat might see a lot, but never say anything, by virtue of their larger goal to help keep the peace. But when he saw that the Pope and the Curia were not inclined to investigate how McCarrick could have preyed on hundreds of young men for several decades, Viganò spoke out. That is why his letter contains statements like, “Before God,” and “my conscience dictates” because he knows he will have to answer to God for all he heard and saw. He wants justice for the victims. He does not want them to keep wondering why the Church hides predators.

Viganò knows that the men who protected McCarrick are powerful. He knows they have the ability to make even a disciplinary censure by Pope Benedict disappear. He implies that when Pope Benedict saw that his sanctions on McCarrick had no effect whatsoever, Benedict resigned, seeing his power was impotent. The only thing these men fear is light. Viganò had experienced this when he started asking where all the money was going when he worked in Vatican finance. His testimony is not addressed to the Pope or the Vatican. It is addressed to the world, to us. Because he felt that we had a right to know.

Viganò came to the United States as a diplomat, and lived here for many years as an outside observer. He read the testimonies of victims. He passed them on to higher ups, urging them to take action. He felt the frustration of victims and their families putting their pain on paper and sending it to the Vatican only to see it disappear into the black box that is the Curia. Now, at the end of his life, when the Curia is ready to wait out the news cycle once again in order to continue business as usual, he has chosen to buck all diplomatic tradition and act. He names names. He points fingers. He is saying, “Laity, if you want to know who knew about McCarrick, here’s who I know that knew.”Is Viganò a Francis hater? Does he expect Pope Francis to resign? My hunch is, probably not. But he wanted to get the Holy Father’s attention. His message was: Investigate this. Don’t let this one go by. The conspiracy of silence needs to end. The people need to have their faith in Christ’s Church restored. Don’t miss this moment, Holy Father.

Published on October 30, 2018 10:35

April 18, 2018

Libraries I Have Known

This is a talk I gave online at the Catholic Library Association's Online Conference. It's about libraries, good and bad, and my young journey with them. I am honored to be the recipient of this year’s St. Katherine Drexel Award. As a native of the Philadelphia diocese, one of the oldest dioceses in America, St. Katherine was part of the home team, so to speak, along with my patron saint, St. John Neuman, both great contributors to the Catholic Church in America and Catholic education. My parish church growing up, Visitation BVM, one of the largest in the diocese, had shrines to both.

Today I am joined by my junior English class at the school where I teach, Padre Pio Academy. Having grown up in Philadelphia and New Jersey, some of the oldest Catholic areas in America, my current home is strikingly different. I live in a diocese founded less that fifty years ago, in an area where Catholics were historically scattered, so although it’s now booming, little Catholic infrastructure exists in the Shenandoah Valley. We are a fledgling school based on hybrid model that brings together a parish setting with the new blood offered by the homeschooling movement. Our three-day-a-week model employs lay teachers who work part time and keeps tuition costs affordable for families. Uniforms for grade school, dress codes for high school, period bells, and school lunches remind me of the Catholic schools I grew up in, but we are pleased to be able to serve students whose families can’t afford private school tuition. It’s a new model suited to the needs of the laity, and provides accreditation and curriculum through our relationship with a nationally-accredited home study program, along with socialization and a parish connection for homeschooling families. We’re working on the kinks, but it’s been fun so far.As an eager and precocious reader at a young age, libraries were intensely important part of my imaginative and spiritual life as a Catholic school student. In this talk, I’m going to tell you about the libraries I have known and browsed through, and how each one met or failed to meet my needs and the needs of students of that age level. Here's a handout of my summary of the three stages of development, which I created for my fellow teachers to use.

Today I am joined by my junior English class at the school where I teach, Padre Pio Academy. Having grown up in Philadelphia and New Jersey, some of the oldest Catholic areas in America, my current home is strikingly different. I live in a diocese founded less that fifty years ago, in an area where Catholics were historically scattered, so although it’s now booming, little Catholic infrastructure exists in the Shenandoah Valley. We are a fledgling school based on hybrid model that brings together a parish setting with the new blood offered by the homeschooling movement. Our three-day-a-week model employs lay teachers who work part time and keeps tuition costs affordable for families. Uniforms for grade school, dress codes for high school, period bells, and school lunches remind me of the Catholic schools I grew up in, but we are pleased to be able to serve students whose families can’t afford private school tuition. It’s a new model suited to the needs of the laity, and provides accreditation and curriculum through our relationship with a nationally-accredited home study program, along with socialization and a parish connection for homeschooling families. We’re working on the kinks, but it’s been fun so far.As an eager and precocious reader at a young age, libraries were intensely important part of my imaginative and spiritual life as a Catholic school student. In this talk, I’m going to tell you about the libraries I have known and browsed through, and how each one met or failed to meet my needs and the needs of students of that age level. Here's a handout of my summary of the three stages of development, which I created for my fellow teachers to use.My first library was located in the grade school attached to Visitation BVM Catholic school where I attended school from Kindergarten through fifth grade. It had floors of waxed linoleum, a small rectangle of carpet for kindergarten story time, and maple wood furniture, with inviting picture books displayed everywhere. Although it was in the basement, my memory recalls it as a perpetually bright, sunny place, well-lined with shelves delightfully packed with books of all sorts and shapes. When I returned for fond visits years later, I was repeatedly shocked by what a small room it actually was. From the viewpoint of my childhood imagination, it was immense. There I read the books of Carol Brinkman and Beverly Cleary, sped through the Bobbsey Twins, Nancy Drew, and the Hardy Boys, and read books on cats, movie monsters, and unsolved mysteries. Much to my mother’s dismay, I had become obsessed with the rather dark and violent musical Man of La Mancha, and it was in fifth grade that I there read a translation of Don Quixote and discovered Shakespeare through the book The Enchanted Island by Ian Serralier. The librarian was a cheerful woman who loved children, and not only helped me find good books (I was easy to please) but allowed me to come in and stock shelves and catch up with my reading and research during recess.

Here I want to point out some characteristics of the first stage of learning, what that great Catholic educator Maria Montessori called the first plane of development or the sensorial plane. In this plane, children primarily encounter reality with their sense: touching, tasting, smelling, feeling, hearing. They learn focus and visual tracking, they seek whole-body experiences where every part of their being is learning. They love repetition, kinetic and auditory, and naming. They delight in names. As with other ages, their mind sorts bits of information and arranges them into narratives, personalized. The abstract concepts of big, medium and small are transliterated into “the daddy one, the mommy one, the baby one,” as the child fits the abstract to his or her personal narrative. Children need to be taught to trust that their senses are communicating reality to them. This will be the foundation for future learning. It is sad to reflect how the whole-body experience of a library—easing books off shelves, the crinkle of the inevitable plastic cover protectors as pages are turned and eyes track words, library voices are attempted, focus begins – that experience is in danger of being supplanted by a sterile virtual reality that absorbs the visual sense only while locking the rest into passive dormancy. I want to thank all of you librarians who continue to give that whole-body experience to our youngest students.Children ages 0-6 experience everything—including good and evil—sensually. In other words, they identify the good not by the nudges of conscience but by the colors the good guys wear, the sound of their voices, their theme songs, or the feeling of goodness inside. Beauty is what communicates goodness. It is critical that libraries in Catholic schools – and everything used to teach young children – be beautiful so that it can most effectively teach goodness sensually. For properly understood, beauty is the incarnation of goodness: it is what goodness feels like, sounds like, tastes like, smells like, looks like.I have an intense hatred of ugly children’s books, of shoddy storytelling and skimpy artwork, particularly in materials intended to present the faith. Our market-driven world seldom bothers to give well-crafted stories or fine artwork to children, with notable exceptions. Instead, children are left at the mercy of the marketplace of merchandised characters and their endless banal stories, with girls’ stories doused in pink paraphernalia, and boys’ bristling with weaponized black-leather-clad redundancies. The realities of female and male, feminine and masculine, need to be respected, but they shouldn’t be caricatured, in fact or fiction. Catholics realize this, but when Bible stories are revamped as awkwardly animated cartoons, when Christ is reduced to a Simpsons caricature, the child’s sensual experience of the sacred suffers. We adults might be pleased by sparse lines and knobby primitive artwork, but children are dismayed when the Blessed Mother isn’t as radiant as a princess. That is why Catholic environments were historically laden with bright stained-glass windows, textures of stone, wood, and linen, the sight of exquisite statues and flickering candles, the sound of bells and human voices, and smells of beeswax and incense. Our worship is meant to be sensorial. It is the catechesis for the youngest among us, and a reminder to the rest of us that Christ became sensorial, became flesh and dwelt among us.Make your library for young children a beautiful place, full of activities that quietly engage all the senses. Help our children to strengthen that connection between goodness and beauty, and curate carefully to leave out anything ugly, even if it purports to be teaching morality.Now, let me speak for a moment of Catholic communal culture, and a word about hothouses and greenhouses.

Here I want to point out some characteristics of the first stage of learning, what that great Catholic educator Maria Montessori called the first plane of development or the sensorial plane. In this plane, children primarily encounter reality with their sense: touching, tasting, smelling, feeling, hearing. They learn focus and visual tracking, they seek whole-body experiences where every part of their being is learning. They love repetition, kinetic and auditory, and naming. They delight in names. As with other ages, their mind sorts bits of information and arranges them into narratives, personalized. The abstract concepts of big, medium and small are transliterated into “the daddy one, the mommy one, the baby one,” as the child fits the abstract to his or her personal narrative. Children need to be taught to trust that their senses are communicating reality to them. This will be the foundation for future learning. It is sad to reflect how the whole-body experience of a library—easing books off shelves, the crinkle of the inevitable plastic cover protectors as pages are turned and eyes track words, library voices are attempted, focus begins – that experience is in danger of being supplanted by a sterile virtual reality that absorbs the visual sense only while locking the rest into passive dormancy. I want to thank all of you librarians who continue to give that whole-body experience to our youngest students.Children ages 0-6 experience everything—including good and evil—sensually. In other words, they identify the good not by the nudges of conscience but by the colors the good guys wear, the sound of their voices, their theme songs, or the feeling of goodness inside. Beauty is what communicates goodness. It is critical that libraries in Catholic schools – and everything used to teach young children – be beautiful so that it can most effectively teach goodness sensually. For properly understood, beauty is the incarnation of goodness: it is what goodness feels like, sounds like, tastes like, smells like, looks like.I have an intense hatred of ugly children’s books, of shoddy storytelling and skimpy artwork, particularly in materials intended to present the faith. Our market-driven world seldom bothers to give well-crafted stories or fine artwork to children, with notable exceptions. Instead, children are left at the mercy of the marketplace of merchandised characters and their endless banal stories, with girls’ stories doused in pink paraphernalia, and boys’ bristling with weaponized black-leather-clad redundancies. The realities of female and male, feminine and masculine, need to be respected, but they shouldn’t be caricatured, in fact or fiction. Catholics realize this, but when Bible stories are revamped as awkwardly animated cartoons, when Christ is reduced to a Simpsons caricature, the child’s sensual experience of the sacred suffers. We adults might be pleased by sparse lines and knobby primitive artwork, but children are dismayed when the Blessed Mother isn’t as radiant as a princess. That is why Catholic environments were historically laden with bright stained-glass windows, textures of stone, wood, and linen, the sight of exquisite statues and flickering candles, the sound of bells and human voices, and smells of beeswax and incense. Our worship is meant to be sensorial. It is the catechesis for the youngest among us, and a reminder to the rest of us that Christ became sensorial, became flesh and dwelt among us.Make your library for young children a beautiful place, full of activities that quietly engage all the senses. Help our children to strengthen that connection between goodness and beauty, and curate carefully to leave out anything ugly, even if it purports to be teaching morality.Now, let me speak for a moment of Catholic communal culture, and a word about hothouses and greenhouses.

Ours is a fragmented secular culture, whirled about in the eddies of new technology, constantly in danger of discarding even the vestiges of human rights and democracy, doubting human value and human choice. The tendency of American Catholics has been to wait for the secular culture to act, and then ride the wave, or barricade themselves against the wave with a barrage of criticism.This engagement with secular culture is very “Catholic,” in some ways, like the Church of the Dark Ages baptizing the barbarians even as they stormed the gates, but in these days, it tends to become either lukewarm and lost, or bitter and apocalyptic. In both cases, it’s reactionary, whether praising or pontificating against each new cultural storm.My personal sympathy as an artist is neither to conform or to criticize, but to create. So, I agree with those who say we ourselves need to be active, not reactive or passive, when it comes to creating culture. I believe we should do something new and Catholic, inspired by the Gospel. In this way I am perhaps siding with St. Benedict, creating intentional Catholic culture, a haven from the storms outside. If you try to create intentional Catholic culture, you will cause problems. You will challenge existing norms, start revolutions in thinking and acting, and possibly create more problems than you solve, at least initially. But you could argue, from a certain point of view, that any Catholic initiative, from Nicaea to Vatican II, created more problems and made existing problems worse, at least to contemporaries. And Catholic education and the Catholic school system were similarly criticized in the beginning, as you might recall, for pulling Catholic children out of the mainstream, sequestering them in a hothouse of feverish zeal, in the same way that Catholic homeschooling and Catholic lay movements are criticized today. There are those who will attack or mock any attempt at intentionally creating a Catholic environment as striving for an unattainable perfection or cowardice in the face of a worldly challenge.I want to remind you that there is a difference between a hothouse and a greenhouse, however similar the structures themselves may look.Both are “artificial environments” where malevolent or detrimental outside influences are consciously excluded. Both are run by gatekeepers who choose what can enter and what must stay outside. Both have walls that let in light and keep out the rest.But one, the hothouse, is designed as a lifelong support system: the other is a training ground. One tries to cultivate dependency: the other to foster independence. But they look nearly the same, except for the intention.In the same way, a Catholic environment that shelters souls considered too weak or exotic to face the outside world and a Catholic environment designed to allow the young to grow strong and healthy, ready to go out into the world and preach the Good News, might have similar rules, criteria, and practices. But the intention is entirely different. And being accused of sharing characteristics with a hothouse does not invalidate or do away with the necessity of greenhouses. And we need Catholic greenhouses, more that ever: for the young, for the broken, for those resting after battle. And I believe that the Catholic library is a vital kind of greenhouse, no matter how old their patrons.As a Catholic educator and author, I am also a greenhouse worker. Together with Catholic librarians, we help create Catholic culture by carefully collating collections and curriculum, weeding through sources, giving guidance, judiciously challenging, protecting, but also equipping.I think your job is harder than mind. I work with a set curriculum in education, with my imagination in the other. You have to face an expanding cloud of material in a world where technology and other revolutions are splintering categories and shattering institutions.You are creating gardens of literature and lore, properly scaled to the size of your students and patrons, where they can play and learn. Of course, research now tells us that playing and learning are remarkably similar.

In sixth grade, I switched to a public school, and a new library. This library was ample and generous, with satisfying rows of bookshelves just the right height, endless mazes of fiction and nonfiction, biography and reference. I loved them all. By this time, I was a researcher as well as a reader, and although I missed my old school, I rejoiced in looking up and learning more about my new passions: Shakespeare, theater, puppets, movie making, animation. But the library periods in public school were painfully short for my imagination and interests. I was by this time the awkward adolescent, the problem child in class, slow maturing, oddly dressed, quiet, and too opinionated for my own good. My homeroom English teacher targeted me for special education, advising me to read the latest edgy teen fiction and trendy teen magazines. I have no idea why: I am guessing she deduced my parents were strict religious nuts and wanted to liberate me. But I stolidly ignored her, following my own internal compass, with only a vague awareness of outside pressure. Naturally, I was a target for bullies during lunch, so I began escaping to the library to read my problems away. I read Wuthering Heights and was transported in bliss. I read Jane Eyre and was relieved my school was nowhere as bad as Lowood Institution. I researched Shakespeare and Queen Elizabeth, read about student filmmakers and dreamed of owning my own still-frame movie camera. The librarian was a nice, cheerful soul, and tried to accommodate me, but in a vast school of thousands of students, I was not where I was supposed to be, and that was a problem. One day my English teacher charged into the library and confronted me, demanding to know why I wasn’t in the cafeteria. My sanctuary days were over.Fortunately, that year I met my best friend in that school. She was not Catholic, but Christian, and we bonded over books, spending lunch periods throughout sixth and seventh grade comparing notes on the best reads. She listened avidly to my own stories and became my first fan. We also found common ground in Christianity, as my faith was becoming more vital to me, and I was on the verge of my high school commitment to Christ, as was she. Years later, I would finish what became my first published novel at the request of her younger sisters. She would remain a close friend and kindred spirit, who shared my passion for C.S. Lewis and introduced me to J.R.R. Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings (which I admired but would not read since it had no girl main characters.). This past spring, she shocked me by announcing that she and her husband were planning on joining the Catholic Church. Our Lord is full of surprises.My time in Catholic and public school coincided with what Montessori called the second plane of development and Dorothy Sayers the dialectic stage. It is characterized by working together bits of information to fit into a system and bits of experience and accumulated knowledge into a story, and a fixation on moral categories, the meaning of the story. Traditional Catholic education calls it attaining the age of reason, with the budding of the moral sense. It is the discerning of the universal story, the conflict between good and evil, asking the question to which the Old Testament and the Gospel are the answer. The child in this stage feels a need to separate light from darkness, right from wrong, and most overtly, fair from unfair. They seek stories with heroes and heroines, come up with complicated schemes to deal with evil: dealing with the possibility of being orphaned, laying plans for defeating death and escaping slavery or kidnapping or quicksand. If they are presented with the Ten Commandments at this time, they will usually memorize them easily, as well as endless catechism questions and the basics of moral theology. Rules and systems for clubs and codes, secret languages and trivia, all of these are categorized happily and codified. This stage is marked by an intense thirst for justice and fairness. As an example, my grade-school children are still debating whether, during last year’s end-of-school picnic games, the opposing team cheated, and whether the moral failure of the parental judges and the moral depravity of the other team should be forgiven or held against them for all eternity. I am forced again and again to be the lawyer for the defense, arguing “before the awful eyes of innocence,” for forgiveness, understanding, and mercy. As Chesterton notes, “children, being innocent, want justice, whereas we adults, being guilty, want mercy.”So, my best friend and I, questing over the gamut of grade school and high school, were quickly learning that the most alluring story could “slime” us by forcing us to read depictions of sex or bodily grossness that we, at age 12 and 13, found appalling. The Age of Blume—Judy Blume—was upon young adult fiction, and my persistent English teacher seemed determined that I should read it all. We secretly agreed she was weird and strange. We both rebelled with the passion of Puritans and developed a personal code as strict as that of any PTA guidelines. I would skim the back pages of any romance book for bedroom scenes, rejecting the book if it contained them. We deduced accurately that books that used swear words, particularly the F-word, usually contained slimy sexual content. This was sheer survival for our imaginations: our peers were reading V.C. Andrews, horror, and fiction full of drugs and suicide, of which our teachers apparently fully approved, and we decided we had to start judging books by covers, despite the aphorism. In these pre-Columbine days, teen fiction and music seemed to revel in horror and gore, and I began to struggle, not surprisingly, with depression. The required seating in public school which meant I had to stare a skull with teeth dripping blood on the back of the shirt of the classmate in front, probably didn’t help matters. The more I read of secular fiction, the more I hated it, and hated the culture which promoted it. In terms of socialization, the free-for-all and lack of guidance was making me more derisive than the most hardline culture warrior could have hoped. It was clear to my best friend and I that right was being mocked and wrong was being tolerated approvingly, and we were in a moral wilderness.

Violating a child’s sense of justice during this stage can have profound consequences. This world does not recognize this stage, and if they do, misunderstands and mocks. Librarians, please respect them. And in the name of the fumbling, shy tween that I was, please don’t try to rush them through this stage. Innocence is almost more crucial to a person now than earlier. This stage of black-and-white ideals will evaporate naturally during the teenage years, but while it endures, trying to convince a child that something their conscience is screaming is wrong is right or ok – whether that something is their parents’ divorce, their sister’s abortion, or blasphemous artwork – plays havoc with their sensibilities and can crush them, creating anger, alienation, depression, and self-hatred. The age of understanding moral complexity will come. But for now, they ask for answers: clear answers, uncomfortable answers, courageous answers. Don’t worry, they’ll probably go back and hunt down every loophole and explore every nuance when they are teens. Understanding this stage used to be what Catholic education excelled at: giving a coherent and holistic picture of the world, assuring students of meaning and purpose and connection. Many of us have lost confidence in that vision. We need to regain it.And the children in this stage are right—as children usually are: right and wrong, good and evil DO exist. There will be final choices. Moral choices do matter: in fact, they’re usually the most important aspect of our lives. What is the truth? How can we live the Truth? This is the question the Gospel answers: and the moral law in the form of the Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes, expressed in the Catechism – these are the limbs and branches of the Catholic faith which we as Catholic educators should be outlining for our students. There will be time enough for older students to perceive the fine twigs and shifting patterns of leaves around it.