Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 9

February 9, 2017

Will There Ever Be a Great Video-Game Movie?

Video games have perhaps never been as embedded in mainstream culture as they are now. It’s become almost a cliché to note that the video-game industry has equaled, if not surpassed Hollywood in terms of sheer profitability in recent years. Technology has improved to make games feel like immersive, cinematic experiences. Virtual reality is on its way to becoming a household item, and the grand debate over whether games can be considered “art” now seems passé. In 1993, Hollywood took its first crack at the video-game market with Super Mario Bros., a steampunk film adaptation of the colorful Nintendo game starring Bob Hoskins as the titular plumber. Unfortunately, it was a financial bomb, a critical disaster, and eventually disowned by everyone involved.

In the intervening decades, Hollywood has tried again and again to bring video games to the screen, with at least 40 major adaptations over the last 25 years. Exactly one, the Angelina Jolie-starring Lara Croft: Tomb Raider in 2001, was a genuine hit, grossing $131 million domestically. Others have been cult sensations, or popular overseas, where video-game brand recognition is enough to sell tickets. But the video-game movie remains a neglected subgenre in the action-movie world, still largely greeted with derision by critics. That said, there have been small signs of life in the genre recently—namely, efforts to engage with the act of gaming itself, rather than just trying to replicate the bloody shoot-em-ups and bombastic set pieces of the source material.

After a real fallow period for gaming films in the last five years (unless you count the success of The Angry Birds Movie, a children’s cartoon based on a cellphone app), two movies in the last two months glanced up against greatness, at least within the limited bounds of video-game cinema. The first, and more frustrating, was Assassin’s Creed, Justin Kurzel’s adaptation of the wildly successful franchise that transposes stealthy action with various historical settings. In the Assassin’s Creed games, the player’s character uses a device called the Animus which allows him to project his mind back in time, to play as one of his ancestors, an assassin operating in the past (say, during the French Revolution, or the Crusades). It’s the kind of bonkers made-up technology that games use all the time as a simple story crutch.

Except Kurzel not only kept the Animus for the film, he made it the central focus of the story, which followed petty criminal Callum Lynch (Michael Fassbender), a descendant of a famous assassin, being strapped into the device to experience the exploits of his murderous forefather. In the film, Callum plugs in, Matrix-style, to a giant spinal tap attached to a crane, and leaps and jumps around in an empty warehouse, mimicking the memories of a murderous hero in 15th-century Spain, while lab assistants (led by Marion Cotillard) around him take notes. It was a broad metaphor for the act of gaming itself—Callum lives an action-packed, but consequence-free, life of bloody mayhem within his own mind. And eventually, as with the other lab rats around him, it begins to take a strange mental toll.

The problem with Assassin’s Creed, strangely enough, was that the action itself was muddy-looking and dull; every time the film cut to Callum’s historical visions, it was hard to stay invested. Kurzel is an Australian director who had previously worked on the dark true-story drama Snowtown and a grim, but well-received adaptation of Macbeth also starring Fassbender and Cotillard. He was better suited to the blurry morality of Assassin’s Creed than to the convoluted video-game logic of its plot or the sweeping vistas of its set-pieces. It was an unusual inversion of the typical problem with video-game films, which emphasize crisp action over deeper philosophizing.

Kurzel was also one of the only directors with any hint of prestige filmmaking in his resume that dared take on video games. Usually, such films are handed to relative neophytes or filmmakers with a background in music videos or commercials. There’s a reason more established directors stay away—Mike Newell (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Donnie Brasco, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire) saw his reputation permanently dinged by the box-office failure of Prince of Persia, a Disney adaptation of a famed platform game, while Duncan Jones (Moon, Source Code) took on the mighty task of adapting Warcraft to the screen and was greeted by punishing reviews for his years of work.

The Resident Evil films are some of the only video-game movies that have come close to capturing the joy of the medium.

Those aforementioned films were embarrassments at the U.S. box office that nonetheless earned their money back worldwide, thanks to the global appeal of gaming’s biggest brands. Warcraft, an epic fantasy adventure that cost $160 million to make, grossed a pitiful $47 million from American audiences, but a staggering $220 million just in China, where the game it’s based on is hugely popular. And if you’ve ever wondered why six Resident Evil films have been made over the last 15 years, despite no discernible interest from U.S. viewers, it’s because those action-packed zombie dramas are consistent earners overseas.

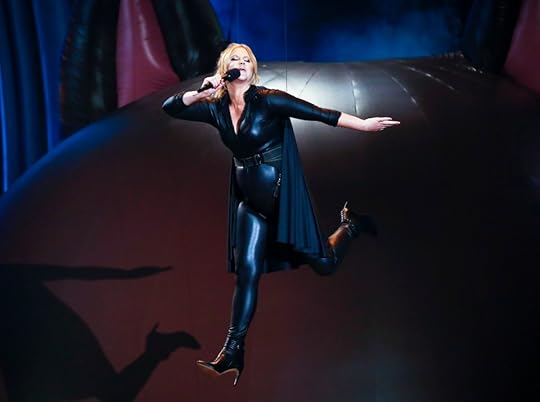

That bring us to Resident Evil: The Final Chapter, the latest in the long-running series that has quietly become a cult sensation over the years. Shepherded to screen by the director-writer-producer Paul W. S. Anderson (the king of video-game films, having also made 1995’s Mortal Kombat) and starring his wife and muse Milla Jovovich (a deeply underrated, immensely charismatic on-screen presence), the Resident Evil films are the only other video-game movies that have come close to capturing the joy of the medium.

The first Resident Evil (2002), starring Jovovich and Michelle Rodriguez, was a claustrophobic adventure set in an underground facility crawling with zombies, an evil computer, and various deathtraps. The characters literally moved from room to room dealing with new obstacles, progressing incrementally as one might through a mid-’90s horror game. As the years have passed, the films have expanded their scope, but remained similarly reliant on video-gamey plotting. Apocalypse (2004) was set in a city overrun with zombies; Extinction (2007) saw Jovovich’s Alice traversing a blasted, post-apocalyptic desert, Mad Max-style; Afterlife (2010) returned her to the setting of the first film, this time equipped with institutional memories (a player’s guide, if you will). In Anderson’s most ambitious effort, 2012’s Resident Evil: Retribution, Alice woke up in a simulation that revisited moments and revived characters from previous films, as if she was re-loading a save point and getting different chances to replay her life.

Some cineastes have grown to appreciate the weird artistry of Anderson’s work, even though the Resident Evil films are still laden with cheap CGI, wooden supporting characters, and buckets of gory action. Anderson’s been called a “vulgar auteur,” along with other B-movie action directors like Justin Lin (the Fast & Furious franchise) and the self-branded duo of Neveldine/Taylor (the Crank films). All of them owe some indirect debt to the world of video games, as their films combine intense action set-pieces with ridiculous, convoluted plotting that only the most die-hard fans can keep straight, but only Anderson has directly adapted games to the screen.

So many of the most hallowed titles—Nintendo’s Zelda franchise, the dystopian masterpiece Bioshock, or legendary PC games like Half-Life or Portal—have never made it to screen, despite frequent rumors over the years. It will always be difficult to find a way to adapt games that thrive on the user’s experience of exploring and existing in a world; it’s a fundamentally different experience from seeing a film, one that forgives more basic, derivative storytelling. Video games are not usually narrative media. Even the ones that are (like 2013’s apocalyptic The Last of Us) feel heavily indebted to films like 28 Days Later or I Am Legend, and are notable for putting players inside the story rather than making them spectators. Right now, the only adaptations worth any serious discussion are the ones that engage with that fact—that games succeed by inserting us into the action. But until others begin to do the same, movies like Resident Evil will never be widely seen as “great.”

John Wick: Chapter 2 Is More Brilliant, Bloody Fun

Nothing in recent cinema can top 2014’s John Wick for pure, furious, elemental action. The first half hour of Chad Stahelski’s directorial debut is like a spooky bedtime story whispered by a hardened mobster: A punk criminal (Alfie Allen) breaks into a man’s home, steals his car, and kills his dog, an unprompted act of aggression, simply because the man disrespected him. Only this man is John Wick (Keanu Reeves), and, viewers quickly learn (as Wick busts open the concrete floor of his basement and pulls a chest of weapons out of it), you don’t make John Wick angry. As my colleague Sophie Gilbert perfectly put it: An idiot killed his puppy, and now everyone must die.

The first Wick saw its antihero come out of retirement fueled by familial rage. His wife, who lured him out of his life as an assassin, had just died, and in losing their dog, he lost his last remaining tangible connection to her. John Wick: Chapter 2, the much awaited sequel, knows it can’t match the emotional heft of the original, so it wisely makes no effort to. Instead, Stahelski and his screenwriter Derek Kolstad double down on the other things that made John Wick great—its innovative, balletic approach to ultra-violence and the film’s peculiar, inventive worldbuilding. It is a fantastic decision that pays off.

There’s a strange comfort in just how good John Wick: Chapter 2 is. It’s a testament to the surprising success of the original, an instant cult classic that took the tropes of the revenge thriller and spun them into phantasmagorical directions. Wick, as played by Reeves, presented as a polite, if unnervingly calm businessman, and the film delighted in watching everyone around him react to his presence. In the first movie, after learning his son had killed Wick’s dog, the head of the Russian mafia reacts with just one word: “Oh.” Then, he tells his son who he’s awoken—“Baba Yaga,” or, as he puts it, the man you hire to kill the Boogeyman.

Chapter 2 begins with Wick dispatching the final elements of the Russian mob he went to war with in the first film, then returning to his life of solitude. But quickly enough, he’s dragged out of retirement again, this time by his fellow assassin Santino D’Antonio (Italian star Riccardo Scamarcio), to whom Wick owes an important debt. Santino can’t hope to appeal to Wick’s grief—this time, the departed Mrs. Wick is mentioned only in passing—but he can invoke the arcane rules and rituals of the league of assassins they both belong to, drawing Wick into a world the first film only explored the edges of.

Rather than try for the gritty societal realism of many a revenge film (think Death Wish or The Brave One), the Wick films exist in some wacky parallel reality where it seems like everyone, from your sainted grandmother to the guy you buy your coffee from in the morning, is a deadly assassin. Wick and his pals all room at the magical Continental Hotel, a five-star paradise run by the unctuous Winston (Ian McShane) where killers can sleep for the cost of one special gold coin. Yes, in these films, assassins even have their own currency (and a gaudy one at that), and the Continental functions as a safe zone where they aren’t allowed to hurt each other, like they’re playing some bloody, globe-trotting game of tag.

Chapter 2 justifies the existence of more Wick without overstaying its welcome.

So Wick re-enters this grand game, first to complete the task Santino demands of him, and then to do battle with the various gangster factions he awakens as a result. Among his enemies this time are Common, who plays an elite bodyguard whose skills equal Wick’s; Ruby Rose, as a mute security enforcer; and Reeves’s Matrix co-star Laurence Fishburne, as the head of some New York branch of killers dressed as hobos. This might all sound like lunacy on the page, but Reeves’s utter commitment to the role helps sell it, as does Stahelski’s skill for communicating so much of his world through simple, stark visuals.

But of course, you’re mainly coming to John Wick: Chapter 2 for the action. Stahelski is a former stuntman who doubled for Reeves on many of his films before moving to directing for John Wick. It’s that background that gives these films their distinctive look; the movies want the audience to see the entire stunt, to revel in the back-breaking labor of Hollywood action films, to enjoy their unreality. Wick fights like a gun-toting sorcerer, shooting any goon that comes close to him with uncanny accuracy. The world is so heightened, yet so strictly adherent to its own magical rules, that it remains compelling as it continues to expand around our hero.

Unlike the original, Chapter 2 sets a clear path for another sequel, acknowledging that it’s quickly grown from surprise cult hit to weirdo Hollywood franchise. Happily, there’s a clear path for a trilogy here, rather than just an endless barrage of movies in which Reeves creatively shoots people in the face. By doubling down on its idiosyncrasies, Chapter 2 justifies the existence of more Wick without overstaying its welcome. It’s a lesson most Hollywood sequels could stand to learn.

What Is CNN For? (Samantha Bee Edition)

It is extremely easy to make fun of CNN. All those shouty octoconvos. That over-reliance on ALL-CAPS CHYRONS sharing NEWS THAT IS FOR THE MOST PART EXTREMELY UN-CAPS-WORTHY. That time it confused Faith Evans with Faith Hill. Et cetera. The easy mockery is a case of great power bringing great—and, often, dashed—expectations: CNN, after all, frames itself as a nonpartisan news source, the place you’d go, all apologies to the Fox News Channel and MSNBC, when you’d prefer not so much to live in the comfort of your bubble as to have that bubble productively punctured. It’s smart branding that comes, implicitly, with a hefty journalistic challenge: CNN, presenting itself as it does as The Most Trusted Name in News, takes on much of the freight of the current debates about objectivity and biases and alternative facts and what-is-Truth-actually. It’s not easy to be Trusted.

So it was noteworthy that Samantha Bee, who is quickly becoming one of the foremost of the comedic public intellectuals, did what is almost unthinkable in late-night comedy: Bee, on Wednesday … praised CNN. And the even more noteworthy thing? She praised CNN, specifically, on the basis of its willingness to go beyond objectivity and nonpartisanship and bubble-busting. On Tuesday, Bee declared, CNN had A Good Day. And the network had its Good Day specifically because, she suggested, it was willing to give up some of its more straight-ahead stuff in favor of juicy, aggressive, and civic-minded argument.

Exhibit A, Bee suggested, was Jake Tapper’s combative interview with the Trump administration’s most celebrated truth-spinner, Kellyanne Conway. (As Bee summed it up: “After briefly banning Kellyanne Conway for being a flaxen-haired foundation of lies, CNN let her back in the gates—straight into Jake Tapper’s cage. And they haven’t fed him this week.”) Bee then aired a montage of the many times Tapper called out the falsehoods perpetuated by the administration, offering viewers a bullet-like spray of “false, false, falsehoods, false.” She accompanied it with a picture of a hungry tiger. Her in-studio audience, at this, wildly cheered.

And, then, Exhibit B: CNN’s airing of audio of the court arguments about the Trump administration’s controversial immigration bans. (Bee, in a moment of seriousness: “Honestly, I have always wanted to live in a country where people listened to and live-tweeted important court cases about civil liberties.”)

And, finally, Exhibit C: the live-aired debate in which Ted Cruz and Bernie Sanders argued the merits of the Affordable Care Act. Bee, first, made fun of the time-travel-back-to-2016 framing of the debate (“It’s like Jeff Zucker looked at his election ratings and said, ‘Hey, what if it was election all the time?’”). And then she made fun of its content (“The socialist and the Slytherin played all their greatest hits.”).

Related Story

How Comedians Became Public Intellectuals

But then, ultimately: Bee approved of CNN’s “We Can Still Have Debate Nights Even Though the Election Is Totally Over” experiment. The Sanders-Cruz meet-up, chock full of nerdery and policy, was yet one more time, Bee suggested, that CNN had distinguished itself by airing content with civic value. “This event that we expected to be a pointless train wreck,” she said, “actually ended up being a semi-thoughtful debate on the merits and flaws of America’s healthcare system.”

But it was also one more time, she implied, that CNN had gone beyond the rote reporting of the news, with all its shouty chyrons, to define what “news” means more broadly: holding power to account (Tapper’s false, false, falsity-falsefalsefalse). Airing an unsexy but judicially (and morally) significant court argument. Airing an unsexy but politically (and morally) significant debate.

Bee’s argument was, in its own way, fairly fraught; it suggested that CNN is at its best—and even, perhaps, that it is indeed only good—when it emphasizes passion, and argument. Her praising of CNN suggested how crucial punditry has become as an element of even the most straightforward of news reporting. It was an argument firmly in the tradition of Bee’s former colleague, Jon Stewart; it was also an argument that has become increasingly common, as even the most nominally “objective” of news sources abandon “That’s the Way It Is” for “This Is How We See It.”

“That’s the way it is” was, of course, fraught in its own way. Its traditions led, often, to false balance and he-said-she-said framings of reality—not to mention, on CNN, octo-convos that were conceived, down partisan lines, as essentially two quarto-convos. American politics, of course, is much more complicated—much more lively—than facile red/blue divides would make it seem.

CNN is aware of this. It is, like many of its fellow journalistic outlets, currently in the process of analyzing the role it will play as American politics and institutions adjust to the new presidential administration. Bee is suggesting one means of adjustment: a network that tries to remain The Most Trusted Name in News specifically by taking stands rather than avoiding them, and by helping to turn “the public” into, much more meaningfully, “a public”—a civic body on top of a demographic one. She is praising the network for airing the kind of debates that can exist not just to entertain people, but to enlighten them.

“We were watching CNN,” Bee told her viewers, a note of wonder in her voice, “and not just in an airport bar with the sound off.” She shifted, at that point, to the second person. “We saw you serve the public interest for almost half a day,” Bee told CNN. “And, sure, it couldn’t last forever,” she added, as a picture of Don Lemon filled her screen. As she ended her segment, the image switched, once again, to a tiger. “We’re just hoping you wake up hungry tomorrow.”

February 8, 2017

Migos the Pioneers

Like apparently a lot of Americans lately, I can’t stop listening to Migos. The particular object of obsession off the Atlanta rap trio’s No. 1 album Culture keeps changing, but for me, for now, the standout is a work of minimalist hypnosis called “Slippery,” on which a high, eerie synth line wavers over drum programming that sounds like a construction project undertaken by very unhurried carpenters. Band members Quavos, Offset, Takeoff and their guest Gucci Mane rap, per usual, about cocaine, sex, and money, but their delivery is anything but rote: Syllables seem to ricochet off the beat, an approximation of a sports car’s squeal serves as a two-note hook, and the verses are structured to create suspense about where they end. The word “wildebeest” figures in prominently, as does the phrase “believe me,” spoken more convincingly than by the president. Late in the track, Takeoff offers this telling line: “They think I’m dumb / They don’t know I see the plot.”

He’s probably referring to something other than the public discourse around his group, but it is true that some people think Migos are, yes, dumb. In the rap world, the band is a flashpoint in an intergenerational taste war over the trendy trap subgenre being “not lyrical,” with exhibit A being their breakout single that mostly consisted of the name “Versace” shouted in staccato. More broadly, Culture and Migos’s recent No. 1 hit (“Bad and Boujee”) aren’t going to persuade any random Facebook commenters to removed the letter “c” before their mentions of “rap.” And the group has made some foolish comments recently about homosexuality being incompatible with toughness. But there’s no denying the sophistication it takes to make music this fun, and Migos deserve credit for both helping to invent a musical form and, with Culture, moving it forward.

Migos have, in various ways, been influential for about half a decade. Contributions include helping popularize the dab—a gesture that for better or ill has reached even Paul Ryan—and a new way to spell the term describing the affections of the social class that owns the means of production. But the trio’s real achievement is musical. The so-called “Migos flow,” a patter-and-pause rhythm where the vocalist revs up in intensity over three-syllable bursts, became ubiquitous in hip-hop after 2013’s “Versace.” The form of a Migos song itself—rappers trading verses, plentiful ad-libs, that signature flow, a brooding-but-bouncy trap beat—is sonnet-like in its sturdiness, and now on Culture, they’ve stretched the template to epic scale and shown how much variation it can sustain.

For a primer in the trio’s appeal, the smash “Bad and Boujee” works well. Each line of the litany-like chorus ends with an ad-lib in the background (“blaow!” “savage!” “grrah!”), and the silky nonchalance of the title refrain contrasts with the serrated vocal patterns around it. The lyrics, while not high-concept per se, find some fun ways to communicate rap-familiar ideas: “Still be playin’ with pots and pans, call me Quavo Ratatouille,” Quavo says. Just as catchy but more dramatic is “T-Shirt,” whose beat is as icy as the song’s Revenant-inspired music video. The verses and chorus unspool methodically, with almost unsettling intensity, though a mention of Yoda lightens the mood.

The grandiosity of that song is typical of Culture, which is pocked with prog-rock moments: waterfalling pianos and lancing violins on the magisterial “Big on Big,” Prince-ly guitar noodling at the start of the contemplative “What’s the Price.” More crucial is the way that the sonic elements interlock rhythmically, like when the chimes, flutes, bass thumps, and verbal scatting of “Get Right Witcha” cohere for a pleasant asymmetrical sway recalling, say, a catamaran cruise under conditions of sun and whitecaps. These songs are party music foremost, but close listens can be both impressive and dizzying.

The running joke around Migos for years has been that fans think they’re “better than the Beatles,” a line that just made its way to the Golden Globes stage and possibly inspired their comrades-in-genre Rae Sremmurd’s recent No. 1 “Black Beatles.” This is sacrilege with a point: Hip-hop right now is as vibrant as rock and roll was in its heyday, and if Migos aren’t exactly literary craftsmen neither really were the Fab Four. If you’re looking for lyrical complexity, you can now turn to, say, Kendrick Lamar just as readily as boomers once turned to Bob Dylan. Meanwhile Migos will be surprising the ear and driving the culture, just like pop geniuses always have done.

'Nevertheless, She Persisted' and the Age of the Weaponized Meme

There are many ways that American culture tells women to be quiet—many ways they are reminded that they would really be so much more pleasing if they would just smile a little more, or talk a little less, or work a little harder to be pliant and agreeable. Women are, in general, extremely attuned to these messages; we have, after all, heard them all our lives.

And so: When presiding Senate chair Steve Daines, of Montana, interrupted his colleague, Elizabeth Warren, as she was reading the words of Coretta Scott King on the Senate floor on Tuesday evening—and, then, when Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell intervened to prevent her from finishing the speech—many women, regardless of their politics or place, felt that silencing, viscerally. And when McConnell, later, remarked of Warren, “She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted,” many women, regardless of their politics or place, felt it again. Because, regardless of their politics or place, those women have heard the same thing, or a version of it, many times before.

Related Story

All of that helps to explain why, today, “Silencing Liz Warren” and #LetLizSpeak are currently trending on social media platforms—and why, along with them, “She Persisted” has become a meme that is already “an instant classic.” It also helps to explain why you can now buy a “Nevertheless, She Persisted” T-shirt, or hoodie, or smartphone case, or mug, each item featuring McConnell’s full explanation—warned, explanation, persisted—scrawled, in dainty cursive, on its surface. As the feminist writer Rebecca Traister noted of the majority leader’s words: “‘Nevertheless, she persisted’ is likely showing up on a lot of protest signs this weekend.” And it’s likely to keep showing up—a testament to another thing American culture has told its women: that “silence” doesn’t have to equal silence.

It started like this: On Tuesday evening, during a late-night Senate session debating President Trump’s nomination of Jeff Sessions to become attorney general, Warren used her time at the podium to read a letter that Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King Jr., had written about Sessions in 1986. King, a civil rights leader in her own right, was opposing Sessions’s potential (and, later, realized) elevation from U.S. attorney to federal judge. Warren began reading the words King had written (to then-Senator Strom Thurmond): “It has been a long uphill struggle to keep alive the vital legislation that protects the most fundamental right to vote. A person who has exhibited so much hostility to the enforcement of those laws”—

At this point, Daines, the senator presiding over the session, interrupted Warren, citing Senate Rule XIX and its stipulation that “no Senator in debate shall, directly or indirectly, by any form of words impute to another Senator or to other Senators any conduct or motive unworthy or unbecoming a Senator.” The matter was put to a vote; it went down party lines; Warren was not permitted to continue. After this, McConnell was asked to explain himself and his party’s silencing of his Senate colleague.

And then: “She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted.” And with it, as the Chicago Tribune put it: “Mitch McConnell, bless his heart, has coined a new feminist rally cry.” Indeed: On the internet, “Nevertheless, she persisted” was applied to images not just of Warren and King, but also of Harriet Tubman, and Malala Yousafzai, and Beyoncé, and Emmeline Pankhurst, and Gabby Giffords, and Michelle Obama, and Hillary Clinton, and Princess Leia. It accompanied tags that celebrated #TheResistance.

Nevertheless, she persisted. pic.twitter.com/bKu3AfeaVH

—

Stephen Colbert's New Approach to Trump Is Working

Earlier in Stephen Colbert’s tenure on CBS’s Late Show, it might have been unusual to see the host deliver a resigned, almost angry assessment of Donald Trump’s political approach, but that was what happened on Tuesday night. “So many beanballs are coming over the plate that you’re not sure what to swing at, not sure what to pay attention to,” he told his guest and fellow Daily Show alumnus John Oliver. “And I think that’s part of the plan of the Trump administration, to do so many things at once that everybody gets swamped.”

As a Daily Show correspondent and host of The Colbert Report, Colbert was once late-night’s sharpest political humorist. But since moving to network television, he had often seemed adrift, sacrificing what made him so distinctive as he played to The Late Show’s broader audience. He seemed particularly lost in his interview segments, including a chat with Trump himself. Not so anymore. Colbert may not be the sarcastic, irony-laden character he once played for Comedy Central, but as Trump has dominated the news every day since taking office, The Late Show has become the home for reasoned, but incisive, discussion, on the perceived overreaches of the White House. Suddenly, Colbert is unafraid to get into the political nitty-gritty again, and one glance at his ratings shows what a success this shift has been.

Of course, Oliver was the perfect guest to participate in a wide-ranging political discussion tinged with fury—it’s the bedrock of his HBO show Last Week Tonight, which returns next week. On Tuesday, Colbert was most interested in Oliver’s last broadcast, shortly after Election Day, in which Oliver urged viewers to go outside their online bubble and actively work to fight whatever wrongs they see in the world. “I think people are still feeling viscerally repelled by things. I think the problem really arises when you get punch-drunk,” Oliver said. “When you hear of Betsy DeVos’s confirmation and think, ‘Well, that’s the way the world is now,’” then the never-ending news cycle has worked in the administration’s favor, he argued. Colbert has been similarly eager to run at Trump’s policies in recent weeks after a 2016 where he seemed far more passive.

On Tuesday, Colbert and Oliver discussed their roles as hosts in the coming years, as comedians and activists trying to keep their viewers focused on issues that matter. “It’s easy to be angry when you’re on adrenaline. It’s much harder when you’re just tired,” Oliver said, before launching into an excoriation of the president’s “debacle” of an executive order on immigration. As a green-card holder, he quipped, he no longer felt safe from deportation, voicing a genuine, broader fear that the administration was changing the bedrock rules of American society at an alarming pace. “Things are not what they are supposed to be,” he said, joking that Trump could be in office for 8, or even 12 years. “Words don’t mean anything anymore, why would numbers?”

What’s even more surprising for The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, though, is that this kind of discussion has grown beyond the occasional drop-by from a political comic like Oliver (or, of course, Jon Stewart himself). When the Quantico star Priyanka Chopra visited the show last week, the conversation was loaded with Trump jokes. Colbert’s monologues now usually focus on the day’s political news, and he’s come to excel at desk segments more reminiscent of his Colbert Report days, such as a humorous exposé of the non-existent “Bowling Green massacre.”

Last year, Colbert’s ratings were low enough that CBS had to publicly deny rumors that it was planning to move James Corden, the host of The Late Late Show, into Colbert’s job. The network then brought on Chris Licht, a CBS News vice president who specialized in morning shows, to help Colbert (who said he had spread himself too thin in his first few months) find his creative voice on the network. For a while, The Late Show seemed as lost as ever, featuring the kind of puffy celebrity interviews that its host struggles to engage with. But Trump’s election, and the constant churn of news and outrage that’s accompanied it, has given Colbert a meaningful boost.

Last week, for the second week in a row, The Late Show beat NBC’s Tonight Show (hosted by Jimmy Fallon) in the ratings, a rarity for The Late Show, even in the days when David Letterman was its host. Though Fallon remains the leader in the crucial “demo,” the 18-49 age bracket that advertisers prize, the ratings crown is no small victory, especially since CBS is a network that has long pitched itself at older viewers. Fallon’s Tonight Show remains resolutely uninterested in politics, discussing current events in only the most light-hearted of ways, and the blowback from its host’s fawning interview of Trump last September hasn’t fully evaporated yet.

Two weeks is a blip in the long-running ratings war that is late-night television, but it’s a meaningful blip nonetheless, coming at a time when it seems political news will never be out of the headlines. Fallon’s entire approach to The Tonight Show has been to lean on the kind of content that went viral with younger audiences—celebrity stunts, recurring Saturday Night Live-esque sketches, and other such meme-able videos. But right now, it’s Trump and the manifold reactions to him that dominate the internet, night after night, and in that realm, Colbert has the advantage.

The Imperfect Power of

I Am Not Your Negro

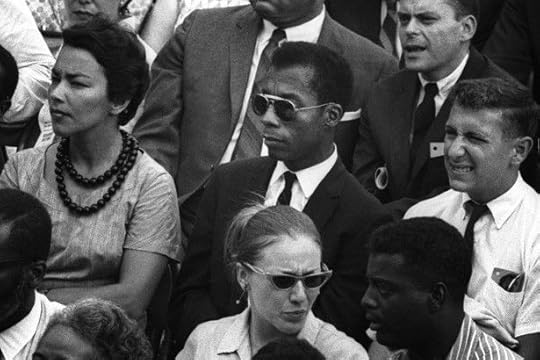

A novelist, essayist, playwright, and poet, James Baldwin was a writer with an arsenal of artistic talent and moral imagination. His signature style was his prose—startling in its intricate design and depth of perception, and fierce in its determination to dismantle the racial assumptions of the American republic and the English language. Baldwin lent his words and energies also to the civil-rights movement and would write one of the defining books of that era, The Fire Next Time, his 1963 classic.

While Baldwin fell out of critical favor in the last decade of his life, and in the years that followed his death in 1987, his work always remained a source of deep and demanding insight and beauty—which is why it’s so heartening to witness the national revival he is currently enjoying. This past September, at the dedication ceremony of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, President Barack Obama began his remarks by quoting from Baldwin’s short story, “Sonny’s Blues.” A group of arts and educational institutions in New York City declared 2014 “The Year of James Baldwin.” And, over the past decade, he has received an unprecedented level of scholarly attention, including the founding of an annual journal committed to reappraising and preserving his legacy.

Now add to this list the director Raoul Peck’s powerful but imperfect documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, which received critical acclaim and a Best Documentary Oscar nomination before it opened nationwide on February 3. The film draws its inspiration from Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript, Remember This House, intended to be a personal recollection of his friends, the civil-rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.—all of whom were assassinated within five years of each other. About a decade after King’s death, in a letter dated June 30, 1979, Baldwin told his literary agent that he had started sketching out a new book in which he wanted the lives of these extraordinary men “to bang against and reveal one another as they did in life.” Baldwin made little progress on the project, however, and left behind only 30 pages by the time he died in 1987.

I Am Not Your Negro’s narrative voice comes from this unfinished manuscript, in addition to Baldwin’s published works and various television appearances. Unlike conventional documentaries that cede narrative control to family members, friends, and experts to shed light on the film’s subject, Peck’s film relies almost exclusively on Baldwin’s writings, read by Samuel L. Jackson. This ingenious move allows viewers to fully appreciate Baldwin’s unmatched eloquence and form a portrait of the artist through his own words, even if the film largely (and somewhat inexplicably) omits a crucial aspect of his work and life: his sexuality.

I Am Not Your Negro begins with the author’s return to the U.S. in 1957 after living in France for almost a decade—a return prompted by seeing a photograph of 15-year-old Dorothy Counts and the violent white mob that surrounded her as she entered and desegregated Harding High School in Charlotte, North Carolina. After seeing that picture, Baldwin explained, “I could simply no longer sit around Paris discussing the Algerian and the black American problem. Everybody was paying their dues, and it was time I went home and paid mine.” I Am Not Your Negro chronicles Baldwin’s life through the civil-rights movement, focusing on his personal relationship to Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin.

Repeatedly, the documentary demonstrates Baldwin’s unique ability to expose the ways anti-black sentiment constituted not only American social and political life but also its cultural imagination. Baldwin was an avid moviegoer and wrote about a number of films in his 1976 book The Devil Finds Work, writings that are brought to life in the documentary. I Am Not Your Negro uses choice scenes from various films—Dance, Fools, Dance (1931), Imitation of Life (1934), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), among others—to show how Hollywood traffics in stereotypes of black menace and subservience as foils for white purity and innocence. In a reflexive move, then, Peck’s film also becomes a commentary on a U.S. movie industry that was bent on reifying racial stereotypes and on perpetuating a fiction of America as the greatest purveyor of freedom, democracy, and happiness.

However much a documentary about American life in the 1960s, I Am Not Your Negro also uses Baldwin’s insights to illuminate our own contemporary reality. The movie’s most gripping scenes intercut footage of police violence directed against black people in the ’60s and shots of similar violence enacted today, using Baldwin’s words to collapse the distance between the two eras. The juxtaposition bracingly highlights the uncanny similarity between the series of black deaths that punctuated Baldwin’s life during the civil-rights era, and the series of deaths—of Aiyana Jones, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and so many others—that mark our own calendar.

Yet for all its recognition that the circumstances of Baldwin’s time echo in the events of today, I Am Not Your Negro remains oddly silent on the role of sexuality in Baldwin’s work and life. Baldwin was one of the first American writers to write openly about queer sexuality. As early as 1949, Baldwin had broached the subject in his essay “The Preservation of Innocence,” and had made it a central theme in his fiction, beginning with his second novel, the 1956 masterpiece Giovanni’s Room. In fact, in 1979, when he began to sketch Remember This House, he had just published his last and arguably finest novel, Just Above My Head, the story of an internationally acclaimed black gay gospel singer.

I Am Not Your Negro presents no sense of this essential thread in Baldwin’s work. Only a passing instance gestures to his sexuality in the film, which reproduces a short sentence from an FBI memo that identifies Baldwin as a suspected homosexual. That the film uses the FBI to account for a major element of Baldwin’s life and corpus, instead of the author’s own voice, further compounds the silence. The apparent desire to represent Baldwin as the quintessential Race Man—a public spokesman and leader of African Americans with ostensibly straight bonafides—goes against not only the principles of Baldwin’s work, but also the reality of his fraught position in the civil-rights movement as a queer black man.

During the ’60s, liberals and radicals alike mocked and attacked Baldwin because of his sexuality. President John F. Kennedy, and many others, referred to him disparagingly as “Martin Luther Queen”; and Eldridge Cleaver, one of the leaders of the Black Panther Party, wrote in his memoir Soul on Ice: “The case of James Baldwin aside for a moment, it seems that many Negro homosexuals, acquiescing in this racial death-wish, are outraged and frustrated because in their sickness they are unable to have a baby by a white man.” In Baldwin’s No Name in the Street (1971), a source from which I Am Not Your Negro draws heavily, the author responded to Cleaver’s attacks against him, but viewers wouldn’t know from the film’s narrative slant how the experience of race and sexuality were closely intertwined for Baldwin.

That Peck chose not to complicate its audience’s view of Baldwin, especially the time in Baldwin’s life when his sexuality became a liability to his public role, is a missed opportunity. And it forgoes the chance to have Baldwin’s complex life reflect the complexity of our contemporary identities—including, how race and sexuality inform our lives not as discrete experiences but as mutually reinforcing ones. To be sure, as he was of America’s racial categories, Baldwin was suspicious of categories like “homosexual” or “gay” to sum up the range of human desire. Still, as he points out in one of his last essays, “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood,” from 1985: “The idea of one’s sexuality can only with great violence be divorced or distanced from the idea of the self.”

In spite of this startling omission, I Am Not Your Negro delivers a remarkable portrait of Baldwin’s life and more broadly of America’s ongoing racial dilemma. It’s a fitting effect for a film about a writer who displayed a rare vulnerability in his work, laying bare his own personal experience as text for national self-reflection. At a minimum, I Am Not Your Negro introduces viewers who may not have read Baldwin to the genius of one of America’s greatest writers. How deeply his words resonate today is a mark of his prophetic vision, which, as the film argues, this nation fails to heed at its continued peril.

Emmanuel Macron's Unexpected Shot at the French Presidency

The French presidential election has been full of surprises—from former Prime Minister Manuel Valls’s failed Socialist primary bid to the financial scandal plaguing the campaign of François Fillon, the center-right candidate. And no one has benefitted from these surprises more than Emmanuel Macron.

A poll released Monday by French pollster Opinionway showed the 39-year-old independent beating Marine Le Pen, the far-right National Front candidate, in the French election’s second round run-off in May with 65 percent of the vote. Le Pen is widely expected to finish either first or second in the first round of voting in April.

And while it’s still early, and polls can be wrong, Macron’s showing is a marked improvement from the third place finish some polls projected him having in December, a month after he declared his independent presidential bid. At the time, Macron was viewed as a political novice— one who, despite having briefly served as economy minister in President François Hollande’s government, vowed to break away from what he described as an obsolete, clan-based political system by launching his own centrist political movement En Marche!, or “On the Move!”

“I want to reconcile the two Frances that have been growing apart for too long,” Macron told a crowd of supporters Saturday in Lyon, France’s third largest city and industrial center, echoing calls he made to bridge the left and the right at the onset of his campaign.

The call for unity may favor Macron. Benoît Hamon’s victory in the Socialist Party primary last month, in which he defeated Valls, the favored candidate, signaled a strong rebuke of the party’s direction under Hollande, the deeply unpopular president who declined to seek re-election after his approval rating slumped to record lows. Hamon’s has been dubbed the “French Jeremy Corbyn,” for the leader of Britain’s Labour Party, or the “French Bernie Sanders,” for the U.S. senator from Vermont. Critics say the Socialist candidate’s politics make him similar to Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the Left Party candidate, whose political faction mainly comprises former Socialists. Mélenchon finished fourth in the 2012 presidential election.

Dr. David Lees, a researcher on French politics at Warwick University in the U.K., told me the dissimilarity between the left-wing candidates could cause more centrist Socialist voters to look elsewhere.

“Macron will be the real winner of the Hamon appointment,” Lees said. “The real issue here lies with the people who are more centrist in the Socialist party, and I suspect what they’ll do now is move towards Macron as a clear centrist candidate and somebody who appeals to left and right, without the same kind of populism and anti-immigrant rhetoric of Marine Le Pen.”

But Macron doesn’t just stand to gain votes on the left. On the right, Republican candidate Fillon’s campaign has been embroiled by allegations he paid his wife, Penelope, and his children a nearly 1-million euro ($1,067,930) salary over more than a decade for being his parliamentary assistants—a job some alleged they did not perform. The center-right candidate, who campaigned on a platform of cutting wasteful spending, reaffirmed he did nothing illegal, and said he would only drop out of the race if a formal investigation were launched. Still, the allegations have hurt him. Fillon, who was originally favored to lead the first round and beat Le Pen in the second round run-off, slumped to third place in the first round in a recent IFOP poll; the poll shows Le Pen finishing first and Macron second.

“It’s been hugely detrimental to his relationship with voters,” Lees said, adding that while traditional Catholic conservatives may likely still vote for Fillon, “center voters who might have voted for Fillon, they might now vote for Macron.”

Macron, though, is not without challenges. Despite presenting himself as an accomplished investment banker and an energetic political outsider, his government experience includes pushing through a number of unpopular business reforms, chief among them his signature Macron Law, which the government, due to its lack of support, had to force through by decree. The law aimed to boost economic growth by, among other things, allowing employers to more easily negotiate salaries and working hours, as well as enable businesses to open more Sundays per year—a departure from French tradition that Sundays should be a day of rest. Moreover, Macron’s independent candidacy runs against the French establishment—without which no presidential candidate has ever won.

But this challenge could also be an asset to Macron. Unlike Le Pen, who analysts have suggested would have a difficult time forming a government given her far-right populist views, Macron’s lack of establishment support would force him to make deals with parties across the spectrum—a feat that’s not improbable given the anticipation that Macron will push a centrist, business-oriented agenda (he has not published his campaign proposals, but is expected to release them this month).

“It’s actually quite a Gaullist idea,” Lees said of Macron’s potential appeal to other parties, referring to Charles de Gaulle, the iconic French leader. “De Gaulle had this idea of not having party politics. He always wanted to stand independently of the party. So it’s quite ironic to have a centrist who’s doing just that, who’s kind of willing to stand individually not part of a party who’s going to try to make these deals on both the left and right, forming some kind of alliance.”

Macron’s ability to sustain momentum will rely heavily on whether Fillon is able to recover from his financial scandal, or if the left will be able to consolidate its base behind Hamon. But it will also depend on whether Macron can avoid scandals himself. The front-runner has already faced allegations he used public funds to finance his campaign, and has recently been linked by Wikileaks’s Julian Assange to Hillary Clinton, the former U.S. secretary of state and Democratic presidential candidate, though neither claim has been substantiated—and it’s unclear why ties to Clinton are necessarily a bad thing in France. Russian state media has also taken aim at Macron, publishing an article accusing him of being an “agent” for American banks and a closeted gay man with ties to a “gay lobby.” He has denied the allegations.

“Those who want to spread the idea that I am a fake, that I have hidden lives or something else, first of all, it’s unpleasant for Brigitte,” Macron said Tuesday, referencing his wife, Brigitte Trogneux. Trogneux, Macron’s former high-school teacher, is 24 years his senior—an age difference that has prompted similar speculation about the pair in the past.

Emmanuel Macron poses with his wife, Brigitte Trogneux. (Philippe Wojazer / Reuters)

The reporting on Macron by Russian state media, coupled with their coverage of Fillon’s troubles, have led to worries Moscow might be interfering in France’s elections the way it did in the U.S. There have been reports of similar Russian activity in other European countries with pivotal elections this year; Russian media coverage appears to favor populist candidates in all those elections. In France, that coverage favors Le Pen, who has expressed views sympathetic to Russia—from rejecting the idea Russia’s actions in Ukraine’s Crimea was an invasion to describing Western sanctions against Moscow as “completely stupid.” Le Pen is also known to have borrowed millions of euros from a Russian bank to finance the National Front’s 2014 electoral campaign.

Still, it’s not clear whether the allegations about Macron’s personal life will be damaging ahead of the election. Personal scandals aren’t new among French presidents. François Mitterrand was discovered to have a secret second family. Jacques Chirac was given a two-year suspended prison sentence for embezzling public funds when he was mayor of Paris. Nicolas Sarkozy and his wife, Carla Bruni, have both been accused of having extramarital affairs, and the former French president was ordered Tuesday to stand trial in a campaign-finance case from 2012. Hollande, the current president, was caught having an affair with Julie Gayet, the French actress—a revelation that caused his popularity to rise by 2 percent.

“His personal life is more interesting than anything political, which appeals to the French sense of some kind of scandal in the private life,” Lees said of Macron. “He’s a colorful candidate, he’s not somebody who’s your average politician.”

Paradoxically, this too could play out in Macron’s favor.

February 7, 2017

'Recruit Rosie': When Satire Joins the Resistance

It went, roughly, like this: Over the weekend, Melissa McCarthy made a surprise appearance on Saturday Night Live, making sweaty, swaggery fun of Donald Trump’s combative press secretary, Sean Spicer. On Monday, Politico reported that Trump had been angered by SNL’s mockery of Spicer—not, it contended, because of McCarthy’s eviscerating portrayal of him, but because of the person of McCarthy herself. “More than being lampooned as a press secretary who makes up facts,” Politico noted, “it was Spicer’s portrayal by a woman that was most problematic in the president’s eyes, according to sources close to him.” As a top Trump donor added, bringing another voice to an idea that has become prominent in the early days of the new presidential administration: “Trump doesn’t like his people to look weak.”

From there it went, roughly, like this: You know, people began asking on Monday, what Trump would probably really, really hate? Say, just for instance, that SNL found a woman to play top presidential advisor Stephen Bannon. And say that they found not just any woman, but the woman Trump has sparred with more publicly, and more reliably, than any other. The one the president has referred to, over the course of their more-than-decade-long feud, as “a real loser” and “a total trainwreck” and “crude, rude, obnoxious, and dumb” and a “fat pig” and a “slob.”

The idea spread. Recruit Rosie! the people cried. Enlist O’Donnell! Who better than Trump’s so-called “pig” to really get his goat!

Dear @nbcsnl,

Now that we know for sure that being played by a woman bothers Trump:

ROSIE

ROSIE

ROSIE

ROSIE

ROSIE@Rosie

Rosie O’Donnell

— Amy Siskind (@Amy_Siskind) February 7, 2017

Ellen as Pence, Rosie O’Donnell as Trump, Melissa McCarthy as Spicer. I would pay all my monies to see this. https://t.co/jQO9fNx5lb

— Mo Ryan (@moryan) February 7, 2017

SNL should cast Rosie O’Donnell to play Steve Bannon. He’d be out by Monday morning.

— jake (@jakebeckman) February 7, 2017

TO DO LIST

-Rosie O’Donnell as Bannon on next week’s SNL

-Massive coordinated fax machine FOIA requests for Trump tax returns

— Seth Bockley (@sboke) February 7, 2017

I'm begging you @SNL - please get Rosie O’Donnell to play “President Bannon” over #BLOTUS. He’ll melt like the Wicked Witch! #TheResistance pic.twitter.com/DhaZuvgtvH

— Captain Janeway (@CaptJaneway2017) February 7, 2017

Rosie, it seems, read the tweets. And on Monday evening, jokingly-or-maybe-not-so-jokingly summoning George Washington and William Sherman and Franklin Roosevelt, the comedian gave her succinct reply: “I will serve,” O’Donnell tweeted.

It was all, on the one hand, a low-stakes joke—not so much at the expense of Steve Bannon as it was at the expense of a president who seems to be unprecedentedly thin-skinned. But “Recruit Rosie” was also, despite its tempest-in-a-tweetstorm setting, much more than a joke: It operated on the premise that jokes can effect significant changes in the daily operations of the White House. It assumed that one bit—O’Donnell playing Bannon, the “real loser” playing the person who seems to be, in Trump’s mind, the ultimate winner—could have not just a comedic punchline, but also a political upshot. Recruit Rosie took for granted that satire can be, at this moment, and with this president, not just a distraction or an amusement, but indeed a weapon of resistance.

The jokes take for granted that satire, with this president, is more than an amusement—it’s a weapon.

In one sense, certainly, that’s an extremely old and bland idea. Call it the banality of comedy: Politics and satire have been intertwined since at least the earliest days of democracy. The Roman poet Juvenal, famed practitioner of the art of Satura, noted that it was hard not to write satire, living as he did within the corruption and decadence of the “unjust City.” Juvenal was, of course, not alone in that sentiment. Shed of the particularities of geography or generation or political system, it is a very human tendency—perhaps the human tendency—to puncture those in power. And American democracy, in particular, with its lively media culture and its hosting of Thomas Nast and Ambrose Bierce and the writers of SNL, has been a particularly eager adopter of the practice. “We, the people” have become, over the years, extremely adept with our side-eye.

But here’s where Recruit Rosie breaks, just a little bit, with all that. Many of the most recent, and most memorable, of the presidential satires—Ronald Reagan, secret genius; Gerald Ford, obvious klutz; George W. Bush, sworn enemy of the English language—have existed not just to amuse their audiences, but also to influence the people’s perception of their targets. They have aimed at the zeitgeist, and, as such, have been less concerned with direct impact than with a softer kind of power: They have generally been concerned with shaping the public impressions that congeal into historical memory. Did George W. Bush, the person, talk about “strategery”—or did his SNL persona? Satire, when done well, makes it hard to remember for sure. Satire, traditionally, has played the long game.

Related Story

The Genius of Melissa McCarthy as Sean Spicer on Saturday Night Live

Trump, however, is not a traditional president. And the satire aimed at him and his administration has been, along with so much else, adjusting accordingly. And thus: Recruit Rosie—which is about humor, sure (O’Donnell as Bannon! Can you even imagine?), but which is also, and more directly, premised on action. It sees itself, as @CaptJaneway2017 suggested, as part of #TheResistance. Its real punchline is that President Trump is so sensitive about his public image that an unflattering portrayal of his primary advisor—which is also an unflattering portrayal of the president—might remove that advisor from the president’s good graces. Taken to its logical extreme … it might even get Bannon fired.

The news cycle that hosted the Politico piece about Trump’s SNL-driven anger with Spicer also featured another story: The New York Times reported that Trump has been spending the early evenings of his young presidency by retiring to the residence of the White House and watching cable news. It was a revelation that would surprise nobody who follows the president’s cable-driven Twitter feed (though Spicer, for the record, dismissed the entire Times story as one more instance—and, indeed, “the epitome”—of “fake news”).

Coupled with the Politico story, though, the Times’s reporting suggested just how powerful television has become as a means of shaping not just the public’s worldview, but also the president’s. Savvy lobbyists are now buying ads that air during the Fox News Channel and MSNBC shows the president is known to watch, on the assumption that it’s more efficient to buy presidential attention through ads than it is to try to obtain that most precious of commodities through more traditional means. And, now, people are suggesting that SNL and its satire can function in a similar way.

Recruit Rosie, that meme-y movement, acknowledges how protective of his public image the current occupant of the West Wing seems to be. It recognizes the extent to which President Trump, as a creature of reality TV, remains deeply concerned about his ratings, whether they be manifested through Nielsen scores or crowd sizes or polling numbers or, indeed, late-night comedy sketches. Progressives—and non-progressives along with them—have been publicly wondering how to resist the new president and his policies. Recruit Rosie hints at a tool that might have been overlooked, so far, in those discussions—one that is powerful precisely because it is so basic: Americans’ ability—at once cherished and time-tested and constitutionally stipulated—to laugh at their leaders.

Netflix and Chill With a Michael Bolton Valentine's Day Special

In 2011, The Lonely Island debuted “Jack Sparrow” on Saturday Night Live, an ingenious digital short in which the comedy-music trio asked the soft-rock icon Michael Bolton to provide a hook for their newest track. After a brief, generic introductory verse in which all four hit up a club, Bolton launched into the chorus: a completely disconnected ode to Captain Jack Sparrow from the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. The character of Michael Bolton was born, an endearing lunk (and major cinephile) so divorced from modern standards of cool that he inserts Disney references into hip-hop songs and yet somehow wins everyone over anyway with his vocal prowess and intense fandom.

It’s this same version of Bolton who stars in Michael Bolton’s Big, Sexy Valentine’s Day Special, released on Netflix on Tuesday, a sparkling and star-studded oddity that’s part-PBS telethon and part-depraved sex comedy, like the love child of Lawrence Welk and Lena Dunham. At its best, it’s a glorious, only partly ironic homage to the vocal power and unfettered sexual magnetism of one of the most indelible figures in balladry. At its worst, it’s baffling. Michael Bolton superfans will likely hate it. And yet it’s Bolton who makes it work, entirely committed to his role and transforming himself from a potential punchline into a hero.

Written and directed by Akiva Schaffer (The Lonely Island) and Scott Aukerman (Comedy Bang! Bang!), the hour-long special is based on the idea that Santa’s elves have made too many toys for Christmas, and there aren’t enough babies to receive them. So Bolton, the undisputed king of Valentine’s Day, is drafted to host a big, sexy TV special that encourages couples to conceive, with musical moments, guest performers, and a phone bank tasked by celebrities (Janeane Garofalo, Louie Anderson, Bob Saget, and Brooke Shields, who gets the most memorable and filthy line). Bolton sings his classic hits, and emcees proceedings from his love nest, a Liberace-esque boudoir tricked out with silk pillows, a roaring fireplace, and high-class erotic art.

An embarrassment of comic talents pop up as special guests, some winningly (Andy Samberg appears as a version of Kenny G who tells Bolton that though he’s cut his hair since the ’80s, he’ll always be “a brave warrior in the tribe of long locksmen”), some less so (Fred Armisen plays a chocolatier so earnestly that his sketch is completely devoid of humor). There’s Maya Rudolph, and Sarah Silverman, and Michael Sheen stealing proceedings as a demented choreographer. Will Forte is Bolton’s twin brother, who can’t sing. The real Kenny G plays a janitor. Jorma Taccone is a punk horrified by Bolton’s lack of cool.

The special seems to be going for a perverted Valentine’s Day version of Elf, with Bolton subbing in for Buddy as a genial innocent roped in to save Christmas (by encouraging couples to have sex on February 14). But he also serves as the adult in the room, expressing disgust when Silverman and Randall Park’s song descends into an ode to pubes, and reining in guests who get out of hand. The show is at its funniest when it fully embraces the heightened, golden-maned character of Bolton via sequences between scenes that show him riding in hot-air balloons or standing next to castles while dragons fly in the background. (“You’re like a heterosexual Anderson Cooper,” Eric André marvels.) At one point near the end, Garofalo yells ecstatically, “Whatever this is, we saved it!” Hopefully, watching the final cut, Bolton feels the same way.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower