Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 11

February 5, 2017

The Genius of Melissa McCarthy as Sean Spicer on Saturday Night Live

It was the kind of moment Saturday Night Live history was made of: an unannounced guest appearance so perfect that it took even the live audience a few moments to register what was actually happening. “Next, on C-SPAN, the daily White House press briefing with Press Secretary Sean Spicer,” a voiceover announced. Then, a person who looked uncannily like Spicer walked onstage to a makeshift podium, presumably causing many viewers at home to squint and look more closely at their televisions. Is that … ? Could it be … ?

It took a few insults delivered in a trademark shriek to hammer home that this really was Melissa McCarthy, in drag, capturing the unquestionable essence of a political figure whose public image so far has largely revolved around belligerence, alternative facts, and cinnamon gum. As soon as the assembled audience figured it out, they began cheering, causing McCarthy’s Spicer to berate them once again. “Settle down, SETTLE DOWN!,” she screeched. “Before we begin, I know that myself and the press have gotten off to a rocky start. And when I say rocky, I mean Rocky the movie because I came out here to punch you. In the face. And also I don’t talk so good.”

It was the particularly genius kind of casting only Saturday Night Live could have dreamed up, with McCarthy’s physical resemblance to the White House press secretary coming off at first as a little unsettling. But beyond that, her interpretation of Spicer—half preschool bully, half unhinged authoritarian caregiver—instantly seemed to stick, joining a list of memorably spot-on SNL performances. Like Tina Fey’s “I can see Russia from my house!” as Sarah Palin and Alec Baldwin’s pursed mouth and beetling glare as Donald Trump, McCarthy’s scene wildly exaggerated the characteristics that Spicer has thus far displayed while nailing the fundamentals of his id.

From the beginning, the fusion of reality and parody was remarkable. “I would like to begin today by apologizing on behalf of you, to me, for how you have treated me these last two weeks,” McCarthy said, “and the apology is not accepted. Because I’m not here to be your buddy. I’m here to swallow gum and to take names.” At which point she chugged back a container of gum, chewed frantically for a few seconds, and then stuck the wad on the podium, for “later.”

McCarthy’s Spicer parodied the White House’s delivery of questionable facts to members of the media during briefings, announcing of the rollout of Trump’s Supreme Court justice pick, Neil Gorsuch, that “the crowd greeted him with a standing ovation which lasted a full 15 minutes, and you can check the tape on that. Everyone was smiling. Everyone was happy. The men all had erections, and every single one of the women was ovulating left and right. And no one, no one was sad.” She engaged in a hostile battle of wills with the press, bullying Bobby Moynihan’s reporter and going on a knotty rant about the language of the Trump administration’s executive order on immigration that left Moynihan’s character cross-eyed. “I’m using your words,” she shrieked. “You said ban. You said ban. You just said that. He’s quoting you. It’s your words, he’s using your words, when you said the words and he’s using them back, it’s circular using of the words and that’s from you.”

The scripting of the skit was brilliant on its own (really, all that was missing was a reference to Dippin’ Dots), but McCarthy’s energy and weaponized hostility took it to another level. Twice, she physically attacked reporters with her podium, threatening to stick other wrongdoers “in the corner with CNN.” When one reporter asked a question about the omission of Jews from the White House’s Holocaust Memorial Day statement, McCarthy shot him with a water gun. “This is soapy water, and I’m washing that filthy lie right out of your mouth,” she yelled.

It was a performance that appeared to have its roots in many of McCarthy’s past roles (the unpredictable Megan in Bridesmaids, a deranged parent in This Is 40, a disgraced Martha Stewart type in The Boss) but one that also seemed immediately part of the pop-culture canon of the Trump presidency. McCarthy’s Spicer may or may not return, but in one eight-minute scene Saturday Night Live reminded viewers that there’s no more potent institution when it comes to political satire.

The Political Saga of Avocados

If beans are, as is sometimes said, a musical fruit, avocados are produce’s Forrest Gump. Far from being just a simple superfood with a deceptively tough shell, avocados have popped up, persistently, throughout some of the notable political and cultural controversies of the last century, from the War on Fat to the War on Brunch to the looming Tariff War on Mexico. They even endured, in typical hardy fashion, the Great Pea Catastrophe of 2015.

Avocados have, you might conclude, been pitted against history ever since they entered the American diet, and have long experienced collateral damage thanks to mercurial opinions on everything from nutrition to immigration to weevils. This weekend, as the nation consumes an estimated 200 million pounds of avocados while watching the Super Bowl, avocados will inadvertently enter the front lines once more, highlighting the clash between popular Mexican imports and President Donald Trump. Which makes it as ripe a time as any to consider the strangely contentious history of a very nutritious fruit.

From the beginning, the relationship between avocados and the U.S. was a tricky one. For one thing, their Spanish name, “aguacate,” was difficult for Americans to say. For another, it’s derived from the Aztec word for “testicle.” Avocados were introduced to the U.S. as a crop in the 19th century but not widely cultivated until the early 1900s, when, as Howard Yoon detailed for NPR in 2006, a group of California farmers came together in Los Angeles to debate their marketing problem. They came up with a new name (avocado), a plural form of spelling (no “e”) and a new strategy, forming the California Avocado Association (it persists today under a slightly different name).

Before the 20th century, avocados were, of course, a staple in Latin American countries, and in Mexico, archeologists estimate that their consumption dates back almost 10,000 years. But in the U.S., home chefs weren’t initially sure what to do with this novel, unsweet fruit. And, as my colleague Olga Khazan reported in 2015, they were prohibitively expensive. So the farmers marketed avocados as a luxury item, playing off ongoing tensions in Europe regarding the rise of communism and the toppling of monarchs. In the late 1920s, ads touted avocados as the “aristocrat of salad fruits.”

Avocados didn’t catch on widely until the 1950s, when they began to be featured more frequently in salads in restaurants and at home. By that time, 25 different varieties of avocados were being grown in California. But in the 1980s, avocados fell victim to the growing anti-fat movement being touted by nutritionists, who spread the message that dietary fat led to heart disease and obesity. And in the 1990s, after the North American Free Trade Agreement was ratified, American avocado growers were concerned that imports of Mexican avocados would bring fruit flies into the country that would ruin American crops. (Importation of Mexican avocados had been banned since 1914, after U.S. plant health officials declared that weevils posed a danger to U.S. orchards—right around the time that American avocado growers were plotting their own rise.)

In 1997, the ban on Mexican avocado imports was overturned in 19 states (although not California) after U.S. health inspectors announced they were satisfied with Mexican sanitary conditions following a two-year investigation. Then, in the early 2000s, the low-carb craze gave avocados a boost, with fat suddenly deemed more acceptable. But it was nothing compared to the looming beast on the horizon, the monster trend no one could predict: avocado toast.

Some time around 2014 (writers have searched for the exact origins of the trend), restaurant chefs started mashing avocado with lemon juice, salt, and other pantry staples, and spreading it on toast, occasionally accompanying it with a fried egg or a slice of tomato. Coupled with the rise of Instagram and the growing predilection for sharing pictures of food, avocado toast became an internet obsession. And avocados in general benefited from the uptick. In 2016, as Super Bowl 50 played out in San Francisco, an estimated 139 million pounds of avocados were consumed in the U.S., up from just 99 million pounds in 2014.

Avocado toast, inevitably, sparked a backlash. In 2015, after the TV chef and domestic goddess Nigella Lawson filmed a recipe for avocado toast for a BBC show, British viewers were unimpressed. “She’ll be teaching us how to make a cuppa next,” one griped. The same year, The New York Times published a recipe for guacamole that featured peas, prompting a debate so furious even the president weighed in. Meanwhile, avocado toast was becoming a stand-in for clueless millennial hipsters and their smugly healthful habits. It culminated in a viral sign at a protest after the November election of Donald Trump: “Put avocado on racism so white ppl will pay attention.”

None of this could change the fact that America had, indeed, become addicted to the fruit, and that in 2016, demand for avocados was outpacing supply. In August, The Guardian asked if hipsters could “stomach the unpalatable truth” about avocados, which was that consuming them in such record numbers was responsible for “illegal forestation and environmental degradation,” not to mention drought (avocado plants are notoriously thirsty), appalling conditions for migrant workers, and orchards controlled by drug cartels.

Will it be a consolation, then, that avocados could fall victim to a 20 percent tariff leveled at imports from Mexico to subsidize a border wall? Probably not. By this stage, they’re a bipartisan fruit, beloved by red and blue staters alike. “A 20 percent tax on Mexican imports would punch Americans in the stomach,” Forbes concluded. Meanwhile, as Adweek reported, avocado mentions jumped 371 percent on Twitter after the White House press secretary Sean Spicer suggested the tariff. If anything can unite Americans against a wall, it’s the little fruit with the big stone(s), and as my colleague Conor Friedersdorf has written, using avocados to achieve political ends is just low-hanging fruit.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show and How Sitcoms Moved to the City

After her death late last month at age 80, Mary Tyler Moore was widely celebrated for portraying one of television’s first modern career women on her eponymous series. But if The Mary Tyler Moore Show, which ran from 1970 to 1977, was a sign of emerging second-wave feminism it was also a harbinger of another related and, if possible, even more contentious cultural change: gentrification.

This may seem far-fetched to contemporary urbanites who equate gentrification with microbreweries and doggy day-care storefronts. In the 1970s, Minneapolis was a demure Starbucks-and bike-free city that resembled Portlandia about as much Anchorage resembles Dubai. Which makes it all the more remarkable that the writers of The Mary Tyler Moore Show managed to sense not just the burgeoning revolution in women’s roles but also its relation to the growth of the white-collar city.

When they started working on the show, the Mary Tyler Moore Show writers certainly didn’t have many television models for understanding the impending change. After World War II, the situation comedy was often a bourgeois suburban family affair. Shows that are now the butt of knowing contemporary jokes like Father Knows Best, The Donna Reed Show, and Leave it to Beaver comforted a still raw nation with images of middle-class, white normalcy in the quiet safety of the ’burbs. In the early 1960s in The Dick Van Dyke Show, Moore herself had played a New Rochelle housewife tending to the pot roast while her husband took the 5:15 train home from his comedy-writing job in Manhattan. The domestic arrangements of Laura and Rob Petrie and their young son on that show were really the same as the Cleavers of Leave it to Beaver, though thankfully the writing for the former was immeasurably wittier.

Television shows set in the city during those decades were generally working-class comedies or mean-street police dramas and reflected the reality of a soon-to-fade urban industrial era. Cops fought crime and vice in The Streets of San Francisco, in Police Story in Los Angeles, and in Kojak in New York City. The best known of the working-class comedies was undoubtedly The Honeymooners, which aired in the early 1950s. Its main character Ralph Kramden, played so memorably by Jackie Gleason, was an everyman bus driver married to an aproned and sharp-tongued wife. Living in the same apartment building in a shabby Brooklyn apartment in the déclassé neighborhood of Bensonhurst was Ed Norton, Ralph’s best friend and neighbor, a sewer worker, as humble an occupation as the writers could have come up with.

Only a few decades later came the last of the urban working-class comic antiheroes, Archie Bunker. In All in the Family, Archie had a day job as a foreman at the docks, but his primary role was to represent the bigotry and obsolescence of the white outer-borough working man in a world poised for change. All in the Family aired on CBS in the same Saturday night lineup as The Mary Tyler Moore Show. It may have only been a coincidence, but in one evening viewers jostled between urban past and present. Mary Richards represented an entirely new economic and social reality set to overpower Archie Bunker and his city.

A decade of urban singlehood had become a predictable part of the life course for the educated middle class.

Chances are the show’s producers calculated that a white-bread Midwestern city would cushion the disorientation of viewers unaccustomed to imagining a young woman living alone in an urban apartment. By the mid-1970s, young boomer women were putting off marriage and children in part because they were busy getting more college degrees. Like Mary, with a B.A. in hand, they were eager to keep their own bank accounts and find their place in an expanding white-collar economy.

A city was the only possible setting for the independence and career ambition of a woman like Mary Richards. Though a time of widespread blue-collar malaise, between 1970 and 1982, the number of college-educated workers doubled; single women played a big role in that increase. Ambitious, forward-thinking media women like Helen Gurley Brown and Gloria Steinem were already showing the way to places like New York and San Francisco where the most appealing jobs were.

That helps explain why by the late 1990s the young urbanite pursuing a career in media or other creative fields was a television staple. The characters of Seinfeld, soon followed by Living Single, Friends (which took the premise of Living Single and added a white cast, as CityLab’s Brentin Mock wrote), Ally McBeal, Sex and the City, and Suddenly Susan constituted a fictional tribe of what sociologists had begun calling “emerging adults.” The median age of marriage for both sexes soared to record heights to reach 28 for women and 30 for men. A decade or so of urban singlehood and career preparation had become a predictable part of the life course for the educated middle class: You graduated from college, then you moved to one of the cities, including Seattle, Portland, Washington, D.C., and Chicago, that hinted at the promise of upward mobility.

The urban single career woman remains a key character in television land.

The characters in these pre-adulthood comedies often had fantasy careers clearly designed to appeal to educated young women strivers. Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw was a dating columnist who hobnobbed with big shots at fashion shows and Charlotte (a Smith College graduate) managed an art gallery; Suddenly Susan’s main character was a successful magazine writer. The shows had equally fantastic urban settings: often lily white, clean, and safe with impossibly large, well-lit and well-appointed apartments. Still their premise was not mythical. A number of cities, especially on the East and West Coasts, were coming out of their postindustrial funk. Crime was down; restaurants and bars catering to well-travelled urbanites were opening in former dollar stores. Cities were gentrifying, and so were sitcoms.

These days, in the trendiest cities, a new educated work force has almost entirely edged out an aging industrial-era working class. In a similar vein on television in shows like The Simpsons and Family Guy, the working-class family has been turned into a cartoon and moved to small towns. The sewer worker is nowhere to be seen; neither for that matter is the dock foreman. Middle-class families still move to the suburbs, of course, and a few television shows have followed them there—including The Middle and, in a nod to the increasing racial integration of such communities, Blackish and Fresh Off the Boat.

But even today the urban single career woman remains a vital character in television land, particularly in sitcoms: 30 Rock is a new classic of the genre, which went on to include The Mindy Project, New Girl, and Insecure. The foursome of Lena Dunham’s Girls and the duo of Broad City work in service jobs as they struggle in a hyper-competitive creative economy—a phenomenon recognizable to many new college grads.

Meanwhile, that house in Minneapolis with the Palladian windows where Mary Richards went when she wasn’t in the office? It’s on the market for 1.7 million. Even the determined Mary might wonder whether she was going to make it after all.

February 4, 2017

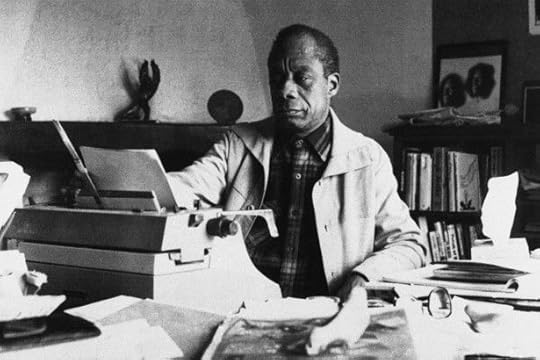

James Baldwin and the Raised Fist: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

James Baldwin Should Make You Feel Uncomfortable

K. Austin Collins | The Ringer

“He’s never left us. And yet his popularity has risked flattening some of the most important tensions in his work. The meme-friendly Baldwin quotations adorning our dating profiles and dormitory walls lack self-awareness. The urgency of his thought prevails, but the consciousness-raising sense of antagonism, the resistance to easy takeaways or preordained political credibility, is smoothed over. If you have Baldwin on your bookshelf or quoted on your Facebook page, you’re signifying that you’re already hip to his message: He attests to your hard-won knowledge, not to the fact that you need further education. (We all do.)”

High on the Apocalypse

Jessa Crispin | The Baffler

“Maybe we all just decided it was cooler to be George Orwell (who came from money) than H. G. Wells (who did not)—cooler to be the smirker saying, ‘Pah, it’ll never work,’ than to be the kid chirping, ‘Here is what we can do.’ The H. G. Wells we find profiled in Krishan Kumar’s Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times was someone who suffered greatly and wanted to help prevent the suffering of future generations. He was someone who cycled through great optimism and great despair, but kept coming back to optimism, believing that equality is possible without totalitarianism.”

24 Is Back to Make You Fear Muslim Terrorists Again

Gazelle Emami | Vulture

“24: Legacy’s arrival at this moment in American history highlights the awkward tension inherent to TV reboots, particularly ones linked to a larger, arguably dated, cultural discourse (see also: Queer Eye for the Straight Guy). In many ways, 24 reflected the Bush era’s war on terror mentality, and was largely accepted by critics and viewers at the time within that context. When a show reboots, especially one with such explicit political overtones, should it pretend like nothing has changed in its absence?”

The Unusual Genius of the Resident Evil Movies

Daniel Engber | The New Yorker

“I wouldn’t call them soulful—they’re highly processed and derivative, as one might expect—but they also have a real electric spark. It’s as if the robotic process that created them had Easter eggs hidden in its code, producing moments when calculated mayhem bursts into abstraction. [Paul W. S.] Anderson may be a Hollywood hack, but he’s one who has found a way to break into the industry machine and turn what should have been an empty-headed action-horror franchise into a vehicle for his spectacular, maximalist aesthetic.”

What Does the Raised Fist Mean in 2017?

Niela Orr | BuzzFeed

“Certain mottos and slogans from the civil rights and Black Power movements have fallen out of fashion, but the raised fist remains a hugely popular visual signal of defiance and solidarity. The co-optation of the raised fist as a patriotic symbol, winking cultural reference, and even totem of irony show that it is just as much about how we perform protest in the 21st century as it is about communicating resistance.”

Ghost in the System: Has Technology Ruined Horror Films?

Scott Tobias | The Guardian

“As physical media has disappeared, and the digital realm of streaming and smartphones has taken over, the movies have struggled to figure out how to make technology a threat again. The telephone was once a reliable scare tactic: the abrupt shock-scare of a ring, the raspy taunts of a serial killer, the cutting of a landline, the cord as a strangling implement, and even the phone itself as a blunt force object in films like The Stepfather. Starting with the dawn of cellphones, however, the new technology has become more a hassle than an opportunity.”

Sampha’s Debut Album Speaks to Anyone With Anxiety

Aimee Cliff | The Fader

“Like the process of navigating any mental health issue, Sampha’s album is not linear or predictable. With its glittering synth melodies and lyrical imagery, it's flooded with sunlight—but this brightness doesn’t always offer comfort. But in the end, Process acts like a musical balm for anxious minds, ending with the message of how important it is to accept the things we can't change about ourselves.”

The Rise of the Female Nerd

Inkoo Kang | MTV News

“Living well is the best revenge, the poet George Herbert wrote—and by that metric, nerdy girls and women should star in their own Tarantino flick. Theirs has been a quiet but steady vengeance, as smart female protagonists and fan favorites have vanquished their previous invisibility or two-dimensionality to claim their place in pop culture, though mostly on TV. The gradual fusion between the nerdy and the normal has heralded a greater acceptance of women who tend to prize their own bright minds as people worth humanizing and getting to know. (It’s an event that Stranger Things, in its salivating adulation for the ’80s, completely missed about Barb, whom it treated as mere fodder.)”

How Pepsi Used Pop Music to Build an Empire

Jeremy Larson | Pitchfork

“If there still exists two separate states of art and commerce, they are often smeared together by the marketing concept of creativity: the extremely clever ad, the artist-facing sponsored content, the spectacular Pepsi Super Bowl Halftime Show. As long as there is the appearance of creativity, the brand underwriting the show will fade into the background and the consumer will fawn upon its aesthetic bona fides. It may even be truly transcendent, leaping from mere creativity to high art.”

February 3, 2017

Rings Would Be Better Off at the Bottom of a Well

In the entirely hypothetical ranking of various rings, the new horror movie Rings belongs somewhere far, far below the following: Wagner’s Ring Cycle, onion rings, engagement rings, The Lord of the Rings, the rings inside trees, the rings encircling the planet Saturn, Ring Pops, and the botched Olympic ring at the Sochi Games in 2012.

That Rings is not good will probably come as no surprise to those who’ve seen the trailer, or who know how horror franchises tend to go after the second film. Still, it’s disappointing enough for anyone who enjoyed the 1998 Japanese classic Ringu or either of the American films it inspired, 2002’s The Ring and 2005’s The Ring Two. Fifteen years after mainstream U.S. audiences were first introduced to J-horror, Rings is presumably making some kind of nostalgia play by bringing back one of the scariest monsters in recent cinema: the undead girl who crawls out of the TV and kills you seven days after you watch her videotape unless you make a copy and show it to someone else. But the story of Samara Morgan, once potent nightmare fuel, has become less scary with each new iteration, culminating in this new, ridiculous installment directed by F. Javier Gutiérrez.

Rings begins with two short, irritating backstories that shakily aim to set up the plot: a plane crash, and an estate sale in which a the deadly video tape is uncovered. But 20 minutes in, it’s still completely unclear how the movie will seek to expand on the Samara mythology. The protagonist is Julia (played by the Italian actress Matilda Lutz), whose boyfriend Holt (Alex Roe) goes off to college and quickly gets roped into a secret experiment involving the video tape, which was found by a college professor named Gabriel (The Big Bang Theory’s Johnny Galecki) who’s now seeking to prove the existence of the human soul.

All this—the going away to college, Julia’s discovery of the experiment, her discovery of Holt’s involvement, Gabriel’s explanation of the experiment—manages to take up the first one-third or so of the film. And it unfolds in the most awkward, unintuitive way possible, with odd time jumps, cringe-worthy character interactions, unexplained tonal shifts, and weird dream sequences. Given the amount of time spent setting up this storyline, it seems for a while that Rings is going in a somewhat intriguing, and unexpected, science-fiction-y direction. But then the story lurches again, trudging down a totally different, more predictable path involving Samara’s origin story.

As the first film in the American franchise without Naomi Watts, Rings makes it immediately clear how much the Anglo-Australian actress elevated the story. Lutz and Roe do what they can in their roles, but they’re not nearly magnetic enough to overcome the jumbled mess they’re stuck with (few are, to be fair). Julia’s inexplicably fearless obsession with the video tape and the visions she’s suddenly plagued with is meant to drive the plot, but her reasons never feels authentic, despite her half-hearted insistences that she has a connection with Samara. (“I can feel her pain and suffering; I’m sick with it and it’s getting worse.”)

The only merciful thing to do at this point would be to put the story of Samara Morgan to rest for good.

As for the scariness: Rings largely fails at re-capturing the terror of Samara, whether it’s trying to remind old fans or convert newcomers. That’s because it sells her malevolence with two lazy approaches. First, it makes different characters discuss the urban legend in the most basic ways possible (“There’s this video, and a chick calls you in seven days.” ) Second, the movie bashes viewers over the head with the sheer freakiness of Samara and her tape, both of which make a dizzying number of appearances, diluting the suspense considerably. Ringu and The Ring, meanwhile, deployed the girl and the video strategically, to maximize scares and to cultivate some mystery.

Rings takes itself way too seriously, which, combined with a weak grasp on tone, translates to the film being unintentionally hilarious from start to finish. When Gabriel heard the voice whisper “seven days” on the phone and demanded, “Who is this!”—the audience in my theater laughed. When a student (played by Aimee Teegarden) called Julia over Skype and screamed, “She’s coming! There’s no stopping her!”—they laughed again. When Vincent D’Onofrio appeared later and intoned mysteriously, “You’re looking for the girl,”—they laughed some more.

Which may offer a glimmer of hope to those who still feel any desire to see Rings: It’s pretty funny! (It may also be a small comfort that the trailer has little to do with the main plot, so there are some surprises left in store.) After watching, it’s hard not to assume production was a torturous process requiring a ton of revisions—the film was originally due out in November 2015, and the story feels like a large puzzle that someone just sort of randomly taped together. So the only merciful thing to do at this point would be to put the story of Samara and her perpetually sodden hair-mop to rest for good. Unfortunately, the logic of her curse closely mirrors the logic of sequel-making: Watch the story, make a copy, and force someone else to watch it quickly as possible, no matter the cost. The real-life version of this curse is far scarier than Rings—and far less funny.

Pop Culture's Fraught Obsession With Celebrity Baby Bumps

At a time of national political controversy, no one would argue that Beyoncé’s pregnancy with twins is particularly consequential news. But no one can deny the public’s fascination with it, either. Her colorful and evocative Instagram post about the matter quickly became the most-liked in history, and celebrity pregnancies have been objects of widespread obsession for years.

In her 2015 book Pregnant With the Stars: Watching and Wanting the Celebrity Baby Bump, Renee Cramer argued that the way that famous mothers-to-be are discussed and obsessed over reflects deep-seated attitudes about gender, race, and reproductive rights. A professor and chair of law, politics, and society at Drake University, she analyzed Beyoncé’s 2011 pregnancy with Blue Ivy while writing the book.

I spoke with Cramer on Thursday. This conversation has been edited.

Spencer Kornhaber: You wrote about Beyoncé’s first pregnancy in your book. What did you say about it?

Renee Cramer: What I argued was that the pregnancies of women of color were being covered in popular culture and the blogosphere in ways that replicated the ways that dominant culture talks about women of color in general: that they were hypersexualized, overly abundant, dangerously fertile.

With Beyoncé in particular, people didn’t believe that she was pregnant—[they believed] that this was just a media stunt meant to solidify her relationship with Jay Z in the public eye. This sense of the black female body as untrustworthy was a real dominant narrative of coverage of her pregnancy.

This time, I’m not seeing that [suspicion] at all. Maybe that’s because the announcement was made with a photo that is an undeniable baby belly. It’s there. I actually don’t know what the gestational age of the twins is, but it seems as though this is a later announcement than the Blue Ivy announcement. Women show their second pregnancies more quickly, and in a twin pregnancy certainly [they show more].

Kornhaber: What were some examples of other celebrity pregnancies you compared her to?

Cramer: There are all these different ways we can see celebrities. They can be “good girls” like Jennifer Garner, Julia Roberts. There are “bad girls” like Britney Spears, there are “bad girls redeemed” like Angelina Jolie. They can be this docile and worried-over woman like Katie Holmes or Nicole Kidman.

But women of color in particular—not just black women but also Latinas—are treated as much more sexualized objects than the white women. With Halle Berry, almost every headline about her was titled with “whoa,” like, “Whoa, sexy mama!” With J. Lo it was an obsessive emphasis on how quickly she returned to her pre-pregnancy bod, and of course the booty. So less an emphasis on the bump for these women and more on the bust line and the back side.

Kornhaber: What do you make of how Beyoncé announced her twins?

Cramer: There’s a huge market in the images of pregnancy and babies. Jay Z and Beyoncé have been amazingly good at stifling that market, or at least using it to their own benefit. They have privatized these images and made fans feel part of the family circle that gets to see them, rather than selling them—or worse, having the paparazzi grab them.

It disrupts this narrative we have of the media being in control of outing celebrities when they’re pregnant, and it really refocuses on her choice to say “yes, I am [pregnant].” Just like her choice to discuss her miscarriage in 2013. These are private moments that are selectively curated, much in the way that all social-media users do, but to maintain an image of control.

“Our obsession is a double-edged sword.”

Kornhaber: In the photos she released, there are ones of her nude, which calls back to pictures like Demi Moore’s famous Vanity Fair cover. What is an image like that typically trying to do?

Cramer: It used to be an image like that was trying to shock and reclaim women’s sexuality in pregnancy. Now, I think there’s a different resonance to those photos, and it’s more of an assertion of comfort. As I’ve watched how people are responding to the announcement, I’m noticing much more glee and happiness than shock or disdain.

Our obsession is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s lovely to be distracted from some of the crap that’s going on in the world by following some celebrity’s pregnancy. On the other hand, doing so enables us to feel comfortable being surveilled in our own reproductive lives. I see a lot more of the former in this one. People are going, “thank you for announcing right now because we really needed a distraction, and we recognize it as a distraction.” I’ve seen speculation that the announcement is timed in such a way as to celebrate black fertility at a moment when that feels powerful but not overtly political.

Kornhaber: Why should we care about celebrity pregnancies?

Cramer: Because we do. She broke the internet. It was the most liked picture on Instagram. That’s insane. When a celebrity announces she’s pregnant, magazine sales go through the roof, [as do] social-media clicks. People care. They care for lots of different reasons, but the fact that they are so interested in someone else’s pregnancy and body is an important thing to notice.

Kornhaber: In your book you say some celebrities have an “inscrutable pregnancy.” What does that mean?

Cramer: I used it to apply to a couple of ways of parenting. So moms who parent without the bump: Melissa Harris-Perry or Sarah Jessica Parker have surrogates, that’s a subversive act. Moms who parent without dads, whether they’re lesbian moms or whether they’re Minnie Driver, who for a long time refused to say who the dad was. M.I.A.’s performance of pregnancy was outside the boundaries of what pop culture has seen when she rapped three days before she had Ikhyd. And Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher used pregnancy subversively—naming a daughter Wyatt as a new gender-neutral name, the way they played with baby pictures.

Those things are part of their curated image, but they also disrupt a coherent narrative. And when we disrupt coherent narratives, that’s where social-movement activism and peoples’ capacity to recreate their own lives comes in.

Kornhaber: Any other thoughts on Beyoncé?

Kramer: She is so in charge of the image. And the fact that she is in charge of her image gives women a deep desire to also be in charge of their bodies.

Kornhaber: So you think she is pushing back on social control of women’s bodies?

Kramer: Yes. Of course she has tremendous wealth, and that helps. But my goodness, I live in a state that’s going to vote in about 20 minutes to defund Planned Parenthood. It isn’t something I intended to have the book become about, but clearly in the last 10 years as our obsession with celebrity pregnancy has risen, so has other peoples’ obsession with controlling the reproductive capacity of average women. And [Beyoncé’s] image of an empowered black woman embracing her own autonomy as a reproducing human, I think that resonates with people.

South Park's Creators Have Given Up on Satirizing Donald Trump

“Jokes about Donald Trump aren’t funny anymore,” The Economist declared in 2015. The magazine took the example of the Roman poet Juvenal, noted practitioner of the art of Satura, who once noted that it was hard not to write satire, when one lived within the corruption and decadence of the “unjust City.” Trump, the magazine noted, “poses a curious inversion to this: He makes satire almost impossible.”

It’s a complaint that has been often articulated about Trump, as the larger-than-life mogul became a larger-than-life presidential candidate became a larger-than-life actual president: How do you mock someone who so readily mocks himself? How do you penetrate those layers of toughness and Teflon to reveal its underlying absurdities? How, as The Economist noted, do you take a tweet like this—“Sorry losers and haters, but my IQ is one of the highest and you all know it! Please don’t feel so stupid or insecure, it’s not your fault”—and make it even more ridiculous?

Related Story

South Park Imagines the Trumpocalypse

One answer: You don’t. That’s the solution come to, at any rate, by Matt Stone and Trey Parker, the creators and writers of, among other works of irreverent pop culture, the long-running show South Park. As Parker told the Australian Broadcasting Company in a recent interview, while promoting the Australian premiere of The Book of Mormon: Making fun of the new U.S. government is more difficult now than it was before, “because satire has become reality.”

Parker noted how challenging it had been for him and Stone to write the last season (season 20) of South Park, which attempted to create a pseudo-Trump through the person of South Park Elementary’s fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Garrison. Mr. Garrison’s political fortunes rose throughout the season, to the extent that its finale—spoiler—found Garrison becoming the 45th president of these United States. It might have been a cheeky take on Trump’s own unconventional rise to power; instead, the season struck something of a sour note. As Esquire put it, “South Park’s 20th Season Was a Failure, and Trey Parker and Matt Stone Know It.”

It explained, of the season’s frantic creative process:

Ideas were started and abandoned. Story lines fizzled out (What happened to the gentlemen’s club? What exactly happened with the Member Berries?). The stories that were completed either made no sense or seemed like they were forced together, as if Parker and Stone tried to shove a puzzle piece into the wrong spot. (Why was SpaceX involved? What were they trying to say with Cartman’s girlfriend? What was the deal with Star Wars and J.J. Abrams?) It was a season of half-thoughts and glimmers of brilliance that never amounted to anything. And because they were trying to keep up with the rapid changes in the election, the jokes and analysis suffered.

South Park in many ways suffered from the same thing that plagued many creators of pop culture in the aftermath of the election: Things hadn’t gone as many had thought they would. They had to adjust not just their expectations, but also their creative plans. Which was unfortunate: The 2016 election came on the heels of a 19th season that was exceptionally prescient in its assessment of Trump. One episode, the much anticipated “Where My Country Gone?,” was expected to take on immigration. It did, but its story also doubled as a dire warning about treating a man who was, in 2015, still a long-shot presidential candidate as a joke. (“Nobody ever thought he’d be president!” one of the episodes Canadian refugees wailed, about the man who had turned his country into an apocalyptic hellscape. “It was a joke! We just let the joke go on for too long. He kept gaining momentum, and by the time we were all ready to say, ‘Okay, let’s get serious now, who should really be president?’ he was already being sworn into office.”)

It’s a shocking decision, coming from writers who have reliably delighted in the absurdities of American culture.

The episode was smart. It was nuanced. It was Neil Postman, in the guise of Eric Cartman. But it worked because it was able to do what the best satire always does: to point out that which is hiding in plain sight. It warned about laughing at Donald Trump long before it occurred to other people to adopt the same anxieties.

And now that @realDonaldTrump is also President Donald Trump, the threats he represents to American democratic institutions are more obvious than they were before. Trump himself, through his executive orders and his seemingly stream-of-consciousness Twitter feed, has made them obvious. Satire, in that context, is more difficult. South Park’s role—and the value it can add—is less clear. So, Parker explained, “we decided to kind of back off and let them do their comedy and we’ll do ours.”

It’s a fairly shocking decision, coming from writers who have, for so many years, reliably delighted in the absurdities of American culture. There’s a certain defeatism to it. But there’s a certain realism, too. As Stone put it: “People say to us all the time, ‘Oh, you guys are getting all this good material,’ like we’re happy about some of the stuff that’s happening. But I don’t know if that’s true. It doesn’t feel that way. It feels like they’re going to be more difficult. We’re having our head blown off, like everybody else.”

Zombies and Marital Strife: The Santa Clarita Diet

One of the more typical scenes of Santa Clarita Diet unfolds like this: Sheila (Drew Barrymore) and Joel (Timothy Olyphant) unload a heavy plastic tub from their car. “Guess what Kelly told me last night? She and Ben are selling their home,” Sheila says. Joel is more concerned with why the tub has no lid, and why Sheila can’t organize their storage better. They bicker amicably for a while, seemingly blasé about the fact that the container they’re squabbling about is filled with the bloody, viscous remains of a colleague whom Sheila has killed and eaten.

That’s basically the whole premise for the new 10-part Netflix show, which debuts in its entirety Friday: the idea that it’s hilarious to splice a cozy marital sitcom with a gruesome, visceral (literally) zombie horror. And a lot of the time, it is, although it takes a while to warm up. The first episode is the most jarring with the shock and gore, testing viewer tolerance for graphic cannibalism and projectile vomiting, among other things, but if you can stick it out there are some, well, killer punchlines ahead.

The conceit for the show, created by Victor Fresco (Better Off Ted) was kept largely mysterious until January, when teasers were released showing Barrymore in character touting the virtues of a new diet, Jenny Craig-style (“I satisfy all my cravings and eat whoever I want”). So it’s not spoiling things to reveal that Sheila is a married realtor and mom who, somewhat unexpectedly, becomes undead. (She’s diagnosed by the teenager next door after the aforementioned projectile vomiting leaves her with no pulse, no pain threshold, and a sudden appetite for uncooked hamburger.) The twist is that Sheila actually likes her new state. Her energy skyrockets, her sex drive peaks, and life takes on a new kind of zest, illustrated by the show’s switch from a muted palette to vibrant color.

The vague drama that unfolds hinges on how Sheila’s zombiehood affects her family, namely Joel and their daughter, Abby (Liv Hewson). After Sheila spontaneously eats a rival realtor (Nathan Fillion at his smarmiest) who won’t stop hitting on her, she discovers her true appetite for human flesh, and the show shifts again into a caper drama, as Sheila and Joel wrestle with whom they might ethically murder and how best to cover up their activities, Little Shop of Horrors-style. (“I hate eating so late,” Sheila pouts after they’re forced to go out at night. “Yeah, there’s a lot about this that isn’t ideal,” Joel responds.)

Zombies, in culture, usually function as a metaphor, whether it’s for slavery or drug addiction or contagion or the decline of humanity. In Santa Clarita Diet, Sheila’s new affliction seems to be an excuse to consider how a midlife crisis might affect a marriage, where instead of having an affair, going on Atkins, or taking up Crossfit, she’s hunting and eating humans. (She buys a Range Rover impulsively, and brags to her friends about the miracle of her new all-protein diet.) And the show’s most sincere moments come as this dynamic is probed, like when Abby wonders if her mom still loves her now she’s undead. But on the whole, Fresco seems to be content using his series to set up increasingly predictable jokes about middle-class zombies. “Got your poncho?” Joel asks. “Keys? Remember your snack?” Sheila nods, holding up a bag of fingers.

For the most part, though, the obvious cannibalism gags are less funny than the show’s sharp grasp on modern culture. (“Pharmaceutical rep hours are super flexible,” a neighbor explains at one point. “That’s why so many of us have time to go on The Bachelor.”) Barrymore is at her zany best as Sheila, gamely gnawing her way through entrails and getting face deep in her various food sources. Olyphant does stellar work with a demanding ask, having to play the straight man to Sheila’s wacky antics while also conveying Joel’s befuddled confusion and loyalty to his ever-more undead wife, coupled with his growing sense of emasculation. “We’re gonna kill people, sweetheart,” he says at one point. “We’re gonna kill them so you can eat them. We’ve been Joel and Sheila since high school. I’m not gonna bail on you now.”

Just as engaging are the scenes featuring Abby and her besotted neighbor, Eric (Skyler Gisondo). Teenagers are enormously tricky for family comedies to get right, but Hewson nails Abby’s sharp intelligence, her cynical affect, and her vulnerability, while Gisondo’s geeky Eric is hugely charming. Santa Clarita Diet’s best scenes often emerge when Joel, Sheila, and Abby scheme to find ways to keep their unit intact—deducing that the family that slays together stays together. It largely makes up for the weak plotting and spotty structure, but whether or not it can hold up a show whose whole existence feels like an excuse to make cannibalism gags depends on your tolerance for (a) gratuitous carnage and (b) the same joke, over and over. (“Sometimes your pot smoking bugs me.” “Well, I don’t like that you’re soon gonna be killing and eating people.”) But if you can get with the gore, there’s frequently a sweet, oddball marital comedy fighting to get out.

The Comedian Is a Laugh-Free Nightmare

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: There are some standup comedians out there (many of them irascible men) who dare to talk about their sex lives, their anger issues, and their various inadequacies on stage—often while using a lot of bad language. Further, the friendly sitcom stars of our youth, whom we know best as sanitized parent figures accompanied by a hearty laugh track, actually tend to be flawed individuals in real life. If all of this is news to you, then you may find Taylor Hackford’s film The Comedian to be a revolutionary piece of art.

Otherwise, you’ll see it as a useless throwback—a fetid, overlong drama laden with bizarre subplots and an inexplicably star-studded supporting cast, built around the dated idea that standup comedians can, indeed, be jerks. The Comedian has all kinds of pedigree: a grumbly Robert De Niro in the title role, an Oscar-nominated director (for Ray, Hackford’s last big hit), and an ensemble that includes Edie Falco, Harvey Keitel, Patti LuPone, Charles Grodin, and Danny DeVito. But this film serves as a good reminder that in moviemaking, pedigree can only take you so far.

The comedian in question is Jackie Burke (De Niro), once the star of a ’70s (possibly ’80s) sitcom where he played a wise-guy cop with a crazy family, who’s now a semi washed-up standup who makes his money at nostalgia comedy nights or signing autographs for increasingly older fans. He’s a toxic mix of bitterness, loneliness, and relative poverty, managed by a straight-faced comedy booker (Falco) and resented by his restaurateur brother (DeVito) and sister-in-law (LuPone). The insult comedian Jeff Ross has a writing credit on the film and supposedly provided much of its onstage material—rancorous and foul-mouthed, but lacking any hint of irony or an artistic sensibility. Like Louis C.K., but without the self-awareness.

De Niro is coasting, as he so often has in recent years, but he’s still not bad. Being a standup requires a particular presence and a strangely confident approach to being pathetic; De Niro largely nails that, taking the stage with sullen ease, and barking penis jokes as if he’s done it for 40 years. His material isn’t special, but it’s authentic enough, the kind of thing one might expect from a night at the Comedy Cellar in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, where a good chunk of the film takes place (including, alongside De Niro, snippets from several actual pro comedians).

However, the life of an over-the-hill club comedian is hardly the stuff of heady cinema. It’s particularly well-worn territory given the recent efforts of TV stars like C.K. and of the director/producer Judd Apatow, the auteur of the “self-loathing bastard” subgenre (whose Funny People was a more piercing, if similarly bloated, exploration of the mind of a faded star). Perhaps you’d expect one other parallel plot for The Comedian, to run alongside Jackie’s efforts on the standup circuit. Instead, The Comedian’s saggy script (which has four credited writers, including Ross) tosses in every twist of fate imaginable.

If you’ve dreamed of seeing De Niro croon fart jokes into a microphone, then The Comedian belongs on your bucket list.

Early on, Jackie gets in an altercation with a heckler at a standup set and punches him; given the chance to apologize by a judge, he refuses and goes to prison. Stuck doing community service, he meets Harmony (Leslie Mann), a fellow self-loathing miscreant that he immediately falls for, despite their 29-year age difference. Unfortunately, that necessitates dealing with her father Mac (Keitel), some sort of retired mobster with a serious attitude problem. Burke also keeps getting on the wrong side of his brother, with a whole extended set piece taking place at his niece’s wedding. There’s also a bunch of funny business at the Friar’s Club, presided over by an imperious hack (Grodin); a segment in which Jackie hosts a Fear Factor-esque game show straight out of 2002; and a random trip to Florida, where he improvises a scatological version of “Makin’ Whoopee” to a crowd of scandalized geriatrics.

On and on it goes, with each new plot element more nonsensical and disconnected than the last. It’s almost like The Comedian is trying to distract from the inherent ridiculousness of its central romantic pairing by throwing celebrity cameos and grumpy mobsters at the audience. Eventually, it resorts to a late-stage twist so hackneyed and groan-worthy I almost called it quits right there (fear not—I stuck it out through the ending, which includes a surprise time-jump).

One could call The Comedian a waste of De Niro’s skill, but he’s also the man who made Dirty Grandpa last year. He’s not trying very hard here, but even so, he’s a fairly magnetic presence—though that certainly doesn’t justify the cost of admission. Mann, on the other hand, is a genuine talent so often thrust into these sorts of roles: women defined only as having a chip on their shoulders, in need of some half-hearted attempt at taming. The Comedian does her this usual disservice, despite her best efforts, and it’s similarly unappreciative of its supporting actors. If you’ve long dreamed of seeing De Niro croon fart jokes into a microphone, then The Comedian belongs on your bucket list. Otherwise, just wait for his next mediocre comedy—no doubt another one is right around the corner.

February 2, 2017

The Obama-Trump Truce Is Already Over

It took George W. Bush and Barack Obama a while to warm up to each other. They had many differences—in party, in age, in temperament, in style. Obama had risen to the presidency in part by peddling a harsh critique of Bush’s administration. The relationship grew gradually over time. The two men joked at the unveiling of Bush’s White House portrait in 2012. Bush invited Obama to the opening of his presidential library. By the time Michelle Obama and the former president embraced at the opening of the National Museum of African American History, stories emerged about the odd friendship between the couples.

Related Story

The Feedback Loop of Doom for Democratic Norms

That growing warmth was fostered in part by a detente between the two men. While Obama fired broadsides against Bush on the campaign trail, Bush mostly shrugged it off. He instructed Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson to keep Obama briefed on responses to the economic crisis, Jonathan Alter reported, with Paulson deeming Obama far more informed about the economy than John McCain. During the transition process, Bush invited Obama and his national-security appointees to war games.

After Obama’s inauguration, Bush quietly left the scene and mostly avoided talking about politics. He repeatedly stressed the importance of allowing Obama to govern without the interference of an ex-president. The silence was so striking that when reports surfaced in April 2015, seven years into Obama’s presidency, that Bush had privately criticized Obama’s ISIS policy, it was headline news. Just as notably, former Bush spokesman Ari Fleischer disputed the reports. “He never mentioned Obama. He gave direct, blunt answers to the hottest topics of the day involving politics of the Middle East,” Fleischer told CNN.

Obama, in turn, responded to Bush’s withdrawal using the same method—he seldom mentioned Bush’s name. As conservatives did not fail to point out, whenever Obama was confronted with his administration’s struggles to get the economy rolling, he complained that he had been handed an extremely poor economy. But he usually avoided saying just who he had inherited that economy from. It was a small courtesy for the former president, and a token of Obama’s gratitude for Bush’s graciousness. Former Obama Chief of Staff Bill Daley told The Washington Post that Obama didn’t mention Bush much in private, either, though some of his staffers grumbled about the former president. (Many of Bush’s aides still found Obama’s criticisms of their old boss unfair and distasteful.)

The public truce between Obama and Bush was notable because of the harsh tone of the 2008 campaign, but it followed the pattern set by previous commanders in chief: The outgoing president would stay out of the way and the incoming president would avoid attacking him. Despite Barack Obama’s attempts to build a rapport with Donald Trump during the presidential transition, and despite Trump’s public gratitude, the tradition seems moribund now.

Obama had already declared his intention to deviate from tradition “if there are issues that have less to do with the specifics of some legislative proposal or battle, but go to core questions about our values and our ideals.” He has already broken his silence once, with a spokesman issuing a statement on protests last weekend over Trump’s immigration executive order. “President Obama is heartened by the level of engagement taking place in communities around the country,” the statement said, calling the demonstrations “exactly what we expect to see when American values are at stake.”

But if Obama is willing to fire a broadside at his successor, Trump’s administration has shown its willingness to attack Obama in terms that are equally harsh, or even harsher. In a statement on Wednesday about Iran conducting a ballistic-missile test, National Security Adviser Michael Flynn spent nearly as much ink blasting Obama’s policies as he did the Iranians:

The Obama Administration failed to respond adequately to Tehran's malign actions—including weapons transfers, support for terrorism, and other violations of international norms. The Trump Administration condemns such actions by Iran that undermine security, prosperity, and stability throughout and beyond the Middle East and place American lives at risk. President Trump has severely criticized the various agreements reached between Iran and the Obama Administration, as well as the United Nations—as being weak and ineffective.

On Thursday, Press Secretary Sean Spicer also opened up on Obama. Spicer was being quizzed about a phone call between Trump and Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, which reportedly ended acrimoniously in part due to differences over an agreement by the Obama administration to accept 1,250 refugees from Australia.

“The president is unbelievably disappointed in the previous administration’s deal that was made and how poorly it was crafted, and the threat to national security it put the United States on,” Spicer said, a statement remarkable not only for its directness but for the accusation that Obama had endangered American security.

A showdown between presidents is unpredictable because it’s so rare. But Obama might feel emboldened by his public standing. He has a hefty advantage in approval ratings—he left office with a 59 percent approval rate, according to Gallup, against Trump’s current 45 percent. (Incidentally, he also had the upper hand when he entered office, with two-thirds of Americans approving of his performance against just 34 percent approval for Bush, which might have encouraged Bush to stay mum.)

Nonetheless, these are likely only the opening skirmishes of a longer campaign of sniping between Obama and Trump. Trump’s agenda is full of just the kinds of items that Obama said would force him to speak up. The tone of Flynn’s attack on Obama startled White House reporters, who asked Spicer on Wednesday whether to expect more like that. Yes, came the answer.

“I think in areas where there's going to be a sharp difference, in particular national security, in contrasting the policies that this president is seeking to make the country safer, stronger, more prosperous, he's going to draw those distinctions and contrast out,” Spicer said. “And so he's going to continue to make sure that the American people know that some of these deals and things that were left by the previous administration, that he wants to make very clear what his position is and his opposition to them. And the action and the notice that he put Iran on today is something that is important, because I think the American people voted on change.”

One changed they voted on, whether they realized it or not, was the end of the tradition of comity between former and current presidents.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower