Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 85

September 5, 2016

The Philippine President's Vulgar Warning to Obama

Rodrigo Duterte, the president of the Philippines, doesn’t hesitate to swear at public officials in public settings. In May, Duterte called the pope a “son of a whore.” In June, he responded to criticism from United Nations secretary-general Ban Ki-moon by calling the organization “stupid” and threatening to withdraw “if you are that disrespectful, son of a bitch.” And this week, Duterte warned that if President Barack Obama asked him about his government’s recent extrajudicial killings, “son of a bitch, I will swear at you.”

Duterte, who took office in late June, made the remarks at a news conference Monday in Manila, the Philippine capital, the Associated Press reported. More than 2,000 alleged drug deals and users have been killed since Duterte launched a crackdown on illegal drug trafficking after assuming office, prompting strong condemnation from the United Nations and human-rights groups.

“I am a president of a sovereign state and we have long ceased to be a colony. I do not have any master except the Filipino people, nobody but nobody,” Duterte told reporters. “You must be respectful. Do not just throw questions. Putang ina, I will swear at you in that forum.”

“Putang ina” is the Tagalog phrase for son of a bitch.

Duterte spoke before he was scheduled to fly to Laos for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit. Obama arrived in Laos Sunday for the summit, becoming the first sitting U.S. president to visit the Southeast Asian country. Duterte and Obama were scheduled to meet there this week, but Duterte’s comments may change that.

Obama said Monday night he had been informed of Duterte’s remarks, and instructed his staff to speak with their Philippine counterparts “to find out if this, in fact, a time where we can have some constructive, productive conversations.”

“I have seen some of those colorful statements in the past, and so, clearly, he’s a colorful guy,” the president said during a news conference in Hangzhou, China, after the Group of 20 Summit there. He called the Philippines an ally, and said his relationship with the Philippine people has been “extraordinarily warm and productive.”

Last month, the U.S. State Department publicly expressed concern over the Philippine government’s detention of alleged drug dealers. Also last month, Duterte made a homophobic slur in Tagalog against Philip Goldberg, the U.S. ambassador to the Philippines, and called him “the son of a whore” in televised remarks.

Obama said Monday he would bring up Duterte’s war on drugs should the two leaders meet.

“We recognize the significant burden that the drug trade plays just not just in the Philippines, but around the world,” he said. But “we will always assert the need to have due process and to engage in that fight against drugs in a way that’s consistent with basic international norms. And so, undoubtedly, if and when we have a meeting, that this is something that’s going to be brought up, and my expectation, my hope is, is that it could be dealt with constructively.”

Hermine's East Coast Journey

NEWS BRIEF Millions of people are under weather advisories in some parts of the East Coast as Hermine continues make its way north, but the storm is not expected to make landfall in the coming days.

Hermine, now considered a post-tropical cyclone, is currently swirling hundreds of miles off the coast in the Atlantic Ocean, further east than meteorologists predicted. The storm is generating heavy rains, strong winds, and powerful waves from the Mid-Atlantic region to southern New England, which pose the greatest danger to coastal cities and beaches. The storm is expected to continue turning toward the sea and weaken by Wednesday and Thursday, according to forecasters.

The storm hit Florida early Friday as a Category 1 hurricane. Flooding forced more than a dozen people from their homes in the state, and some were rescued from rising waters by emergency workers. Hermine was downgraded to a tropical storm later that day as it moved northward.

Here’s an animation of the storm’s movements, courtesy of NASA satellites:

Hermine is a huge storm, but it’s a slow-moving one. It’s currently working its way up the coast at six miles per hour, according to the National Hurricane Center. Its strongest winds were recorded at 70 miles per hour.

Clint Eastwood, Bard of Competence

In the days after US Airways Flight 1549 ditched into the Hudson River, with all 155 people aboard the plane surviving the impact, the water landing came to be known as “the miracle on the Hudson.” The term came from the movies: “We had a Miracle on 34th Street,” New York’s then-governor, David Paterson, said in a speech hailing the heroics that made for the successful water landing. He paused. “I believe now we have had a Miracle on the Hudson.”

In his upcoming movie about the fated flight, Sully—named, of course, for the pilot who guided the Airbus to safety that day—Clint Eastwood frames that miracle in more prosaic (you could also say more humanist) terms. Here, the successful ditching of the plane into the frigid waters of the Hudson is a triumph not of divine intervention, but of something both duller and more interesting: basic human competence. Things worked out the way they did that day because Captain Chesley Sullenberger and his first officer, Jeffrey Skiles, were able to summon years’ worth of rote aviation experience to transform a narrow body of water into an ad hoc runway.

That bit of spiritual revisionism would seem to make Sully, which will premiere on Friday as the 38th movie Clint Eastwood has directed, fitting for a moment whose movies are as concerned with reveling in life’s banalities as with escaping them. Sully is Eastwood’s entry into an expansive—and burgeoning—genre: “competence porn.”

Competence porn takes that classic concern, “the human condition,” and renders it relatably banal.

This term seems to have been coined in 2009, by John Rogers, one of the writers of the TV show Leverage—based on his recognition that, “for the audience, watching competent people banter and plan was a big part of the appeal.” The genre is older than its coinage, certainly; Star Wars would be considerably less awesome had Luke been unable to get the hang of a light saber. But it is having a particular moment now. Its exuding of competence is what helped to give The Martian its “science the shit out of it” verve. And what makes Olivia Pope, in Scandal, compelling as a professional as well as a character. And also the doctors of Seattle Grace. And the wonks of The West Wing. And the space-travelers of Star Trek. (And also the cooks of Top Chef, and the designers of Project Runway, and the singers of The Voice, and the bakers of The Great British Baking Show.)

The performance of competence is “porn,” ostensibly, because of the small frisson of pleasure it offers in presenting people who are really, really good at their jobs—that classic Hollywood cliche, “the human condition,” only refigured for relatable banality.

Related Story

American Sniper Makes a Case Against 'Support Our Troops'

You might not expect Eastwood to make a film to join that genre. He is, after all—his professed annoyance against people over-reading his work notwithstanding—a director who tends to revel in themes of traditional epicness: heroism and its opposite, forgiveness and its opposite, justice and its opposite. As an actor but particularly as a director, over an expansive, omnivorous career, Eastwood has been broadly concerned with exploring what happens when the individual encounters the hulking machinery of the institution—be it law enforcement (Dirty Harry, The Outlaw Josey Wales), or the military (American Sniper, Flags of Our Fathers, Letters From Iwo Jima), or marriage (The Bridges of Madison County), or NASA (Space Cowboys). Eastwood favors straightforward, taut storytelling—he is Hemingway to Hollywood’s Nolanian, Herzogian Faulkners—and yet, thematically, his films tend to swoop and swerve and soar. Dirty Harry has become a philosopher.

And Eastwood has been at his best as a director when he’s taken his preferred dynamic, the individual chafing against the communal, to consider a theme that has particularly preoccupied him in recent years: redemption. The dynamics of grace, and the extent to which a right can compensate for a wrong, animate Gran Torino, and Million Dollar Baby, and Mystic River, and Invictus, and Unforgiven (perhaps his greatest film, if you don’t count the ones that found him co-starring with an orangutan named Clyde). Their attendant questions help to make Eastwood, whether his topic be cowboys or Jersey boys, continually relevant.

And yet, in Sully, this question seems to be absent. The film instead takes its nominal “miracle”—that fragile fusion of the human and the divine—and picks it apart, second by second and decision by decision. “For me, the real conflict came after,” Eastwood explains to Variety, “with the investigative board questioning his decisions, even though he’d saved so many lives.” So he trains his focus not on the landing itself, but on the bureaucratic aftermath of the landing: the investigation, designed to ensure that another miracle would not be necessary.

Eastwood favors straightforward storytelling: He is Hemingway to Hollywood’s many Faulkners.

This is also to say that Eastwood focuses, essentially, on the human work that made the miracle, on the professional expertise that allowed it to be achieved. Here is the 10,000-hours thesis, celebrated for its filmic virtues.

And here, too, is competence celebrated for its own sake—and not just at the individual level. Sully is a celebration, according to its star, of institutions themselves. “In the political atmosphere we’re in, there are an awful lot of points being made on [the notion that] you can’t count on people and institutions because they’re all broken—that none of them work,” Tom Hanks said of the film. “Well, that’s nonsense. They’re not all broken. And you can still have faith in them. And, in that regard, I think this movie makes a really strong case.”

If so, it’s a generally new chapter for Eastwood. In his personal life, after all, he has identified as a libertarian, and his “leave everybody alone” stance is what has informed Eastwood’s better-known political activities, whether they involve (recently) decrying the varied delicacies of the “pussy generation” or (slightly less recently) giving a televised lecture to a chair. And yet a celebration of institutional competence also serves as an apt coda to Eastwood’s earliest work and explorations: There is, after all, a certain freedom that comes when someone is really, really skilled at something. And when it’s a bunch of someones who join forces to be really, really skilled at something together, great things can happen. Things that can be, indeed, their own kind of miracle.

September 4, 2016

Sainthood for Mother Teresa

NEWS BRIEF Mother Teresa, the nun who devoted her life to working with sick and poor communities in India and elsewhere, was canonized as a saint on Sunday.

Pope Francis declared sainthood for Teresa during a ceremony at the Vatican in front of tens of thousands of people. Her canonization comes a day before the anniversary of her death in 1997.

“Her mission to the urban and existential peripheries remains for us today an eloquent witness to God's closeness to the poorest of the poor,” the pope said. “Today, I pass on this emblematic figure of womanhood and of consecrated life to the whole world of volunteers: may she be your model of holiness.”

Here was the scene in St. Peter’s Square:

Stefano Rellandini / Reuters

Teresa will now be known as Saint Teresa of Kolkata. She was born Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu in Skopje in modern-day Macedonia in 1910 to Albanian parents. She is known for founding the religious order Missionaries of Charity in 1950, an organization of nuns that is now active in more than 100 countries and cares for the impoverished and the sick, particularly people with AIDS, and orphans and the elderly. She won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 for her work. She died in 1997 at the age of 87.

Saint Teresa joins about 10,000 other official saints in the Catholic Church. Becoming a saint is not easy and can take decades, and the process for canonization usually begins five years after a candidate’s death. “Because she was so widely admired among the faithful, however, Pope John Paul II waived that traditional waiting period, allowing the process to begin only 18 months after her death in 1997,” explained Josh Ulick and Youjin Shin in The Wall Street Journal this week.

To become a saint, one must, as my colleague Kathy Gilsinan outlined last year, “1. be dead 2. have demonstrated ‘heroic virtue’ while alive and 3. perform miracles posthumously.” She continued:

Modern miracles are mostly healings, and the Vatican reviews them with both doctors and theologians to make sure they are “complete,” “instantaneous,” “durable,” and inexplicable but for the intercession of the holy person.

The Vatican acknowledged Teresa’s first miracle in 2003, after the nun was said to have cured a woman with tumors in Kolkata. Her second miracle, recognized in 2015, involved curing a man with multiple brain abscesses in Brazil.

While many celebrated Teresa’s path to canonization, others believe some of her actions were less than saintly. NBC News’s Matt Bradley describes some of the criticism:

In the eyes of some, particularly in India, she put fame and piety before her mission of aid. Among other critiques, she has been accused of offering stingy or substandard medical care; of proselytizing to her patients; of claiming virtue in suffering rather than trying to alleviate it; cozying up to dictators; and of promoting her efforts to a global media eager for heroes.

The Vatican distributed 100,000 tickets for Sunday’s canonization ceremony. The square was bursting with people, some waving the national flags of India, where Teresa arrived at 19 years old and where she would carry out most of her work.

The View From Baltimore

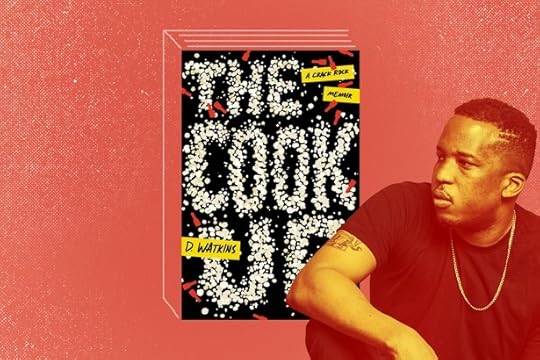

D. Watkins’s memoir, The Cook Up, begins on a spring day in East Baltimore, in 1998. The author, then a senior in high school, was “rolling a celebratory blunt because College Park, Georgetown … and a couple other schools were letting me in” when a neighbor banged on the door: Watkins’s older brother, Bip, had just been shot dead on the street outside.

I ducked under the yellow warning tape and pushed past the beat cop … The noise and a cold silence blanketed the crowd.

“Bip, get up!” I begged. “Get up. Come on …”

The beat cop gathered himself and slammed me down next to my brother. He flipped me like a pissy mattress, positioning for a chokehold. Fuck fighting back. I wish I had died too.

Bip raised Watkins from the age of 12, keeping him on the straight and narrow with Frederick Douglass quotes and bling for good grades, while Bip hustled home-cooked crack cocaine. After the murder, Watkins has to make his own way. He tries college, which looks and feels like “a Gap commercial,” a place where other black students try on middle-class whiteness, wear pastels, call each other “dude.” Watkins, for his part, wears Gucci sweat suits and $15,000 worth of jewelry. In the athletic center, he plays dice.

The juxtaposition is straight out of the sitcoms Watkins’s generation grew up watching, like The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and the Cosby Show spin-off A Different World—stories about black self-sufficiency made safe for curious, comfortable white people. Watkins flips this script twice. He drops out mid-semester and spends the next four years cooking crack in a Pyrex measuring cup in his kitchen, peddling it to neighborhood addicts, hiring friends and relatives to hustle for him, and making “a ridiculous amount of money.” Then, at the peak of his empire, he renounces it all, Siddhartha-like, to read and think. Watkins returns to college in the last pages of his memoir. In the final scene, he’s in an introductory writing class, reading Langston Hughes, Michael Eric Dyson, and Sister Souljah—writers who kindle what he calls “my obtainable superpower.”

A decade separates that scene and The Cook Up’s publication this spring. After Watkins earned his bachelor’s degree, he went back for a master’s in education and an M.F.A. in creative writing. He’s written essays for The New York Times, The Guardian, and Rolling Stone, 23 of which are collected in his first book, The Beast Side: Living (and Dying) While Black in America (2015). After one of those essays (on being “Too Poor for Pop Culture”) went viral in 2014, Watkins was featured on mainstream-media outlets such as NPR, CNN, and NBC.

As high as he’s climbed, Watkins is quick to tell interviewers that he hasn’t “made it out yet.” He still lives in East Baltimore, where he is an adjunct professor and a freelance writer; on the side, he makes commemorative videos for weddings and funerals. Watkins’s native-son appeal is usually part of the reason he’s interviewed. The mainstream has a way of absorbing minority writers by typecasting them as “the voice” of this or that margin. Watkins plays along in order to address fatal disparities in American culture—and in his readership.

When Watkins was pitching his book, one publisher reportedly told him that his target audience was “white people who watch Breaking Bad.” Watkins seems more interested in drawing readers from his own neighborhood, though he splits the difference with his subtitle. A Crack Rock Memoir isn’t hype. Substance is style here. The short sentences are hard and bitter. The chapters are two minutes long, with quick blasts of intensity calibrated to hook anyone.

It’s easy to imagine the memoir being assigned in schools. Accessible and edifying, the book even comes with a list of discussion questions. If life lessons sometimes slow down the action, perhaps that’s to be expected. (I’m thinking of two pages where the word “should’ve” appears 18 times.) Like the rappers he quotes, Watkins acts out his self-understanding through story or sermon—or story as sermon.

In the tradition of James Baldwin’s “Letter From a Region in My Mind,” The Cook Up is a personal history that complicates racial stereotypes. “To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it,” Baldwin wrote. Since then, Baltimore has eclipsed Harlem as a locus of America’s racial anxiety. The image of that anxiety has changed, too, with the mass criminalization of young black men. Watkins’s writing offers answers to a question Baldwin might have asked, had he lived long enough: How can a superpredator’s past be used?

The Cook Up is costumed as a crime drama (the crack rocks stippling the cover, the blurb from David Simon), but its real drama is universal: coming of age. Watkins spends much of the book in a state of hyperadolescence, acting the part of a gangsta but unable to be one. Angsty and confused, he gropes toward fulfillment, spending drug money on random acts of kindness. Eventually he gets his bearings the way everyone must, by mastering what he’s inherited.

What Watkins learns on the streets of Baltimore is just as true on the Upper West Side: Everyone is compromised by things that hurt so good.

During that first semester at college, Watkins discovers the “trust fund” his brother stashed in a red safe—“stacks and bundles of balled up and unseparated cash, receipts, a watch, maybe a brick and a half of Aryan-colored cocaine, about half a brick of heroin, two pistols, a big zip of vials.” The inheritance offers an object lesson that anyone growing up under late capitalism would recognize: Power comes from commercializing a demand and exploiting it.

The mainstream economy has producers and consumers. Watkins’s has “dope boys” and junkies. The transactions between them are toxic, but compensate for opportunities that don’t exist, services that don’t deliver, and authority that doesn’t function. After crooked police raid Watkins’s home to seize his late brother’s jewelry and electronics, two junkies hide Watkins’s safe for him. How’s that for child protective services?

The insight that makes Watkins go clean, launching him into adulthood, is that helping people endure a rigged culture blurs into doing harm. Take Miss Angie, a godmother figure. When gentrification triples her rent, Watkins gives her enough cash to live for a year. She returns the favor, frying up comfort food around the clock for Watkins and his crew. But look again: The gift implicates Miss Angie in the crime that ruined her neighborhood, and in turn she keeps Watkins on a diet of tasty poison. What Watkins learns on the streets of Baltimore is just as true on the Upper West Side: Everyone is compromised by things that hurt so good.

Bill Clinton’s finger-wagging rebuke of Black Lives Matter protesters back in April was a reminder that conversations about race and class are hopeless when people can’t find common ground to stand on. But if presidents can’t create a basis for mutual understanding—a hard-learned lesson of the Obama era—writers can. It isn’t comfortable seeing oneself in the portrait of a crack dealer, and that’s the point. In one of his sharper lines, Watkins sums up his motivation for hustling: “Because only drug dealers and the top 1 percent of Americans can afford to push a cart through Whole Foods.”

Watkins knows his readers live in different Americas. The Cook Up is their invitation to notice one another standing in the same line.

September 3, 2016

Hope Solo and 'Hamilton': The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Why We Make Women Athletes Into Villains

Beejoli Shah | Rolling Stone

“The respectability politics of female athleticism have never come under real scrutiny before because, well, female athletes were never really under scrutiny before. But to hold them to a standard of behavior based on what we want our athletes to exude—professionalism, dedication, veins cold as ice—is a tenuous game to play given that our standards for sportsmanship are a constantly moving target.”

Making House: Notes on Domesticity

Rachel Cusk | The New York Times Magazine

“Like the body itself, a home is something both looked at and lived in, a duality that in neither case I have managed to reconcile. I retain the belief that other people’s homes are real where mine is a fabrication, just as I imagine others to live inner lives less flawed than my own. And like my daughter, I, too, used to prefer other people’s houses, though I am old enough now to know that, given a choice, there is always a degree of design in the way that people live.”

Gabrielle Union on Birth of a Nation Co-Star Nate Parker’s Rape Allegations

Gabrielle Union | Los Angeles Times

“I took this part in this film to talk about sexual violence. To talk about this stain that lives on in our psyches. I know these conversations are uncomfortable and difficult and painful. But they are necessary. Addressing misogyny, toxic masculinity, and rape culture is necessary. Addressing what should and should not be deemed consent is necessary.”

Why Movies Still Matter

Richard Brody | The New Yorker

“The experience that the watching and the critique of new serial television resembles above all is the college experience. Binge-watching is cramming, and the discussions that are sparked reproduce academic habits: What It Says About, What It Gets Right About, What It Gets Wrong About. There is a lot of aboutness but very little being; lots of puzzle-like assembling of information to pose particular kinds of questions (posing questions—sounds like a final exam), to explore particular issues (sounds like a term paper).”

The Burning Desire for Hot Chicken

Danny Chau | The Ringer

“Hot chicken’s widespread popularity suggests a shift in the national palate. But it’s a dish rooted in a strong sense of place; you’ll always know how to go directly to the source. The most celebrated and emblematic dish of one of the 25 most populous cities in the country is something designed to hurt you. I’d never felt more American than when I was eating hot chicken in Nashville.”

Black Tweets Matter

Jenna Wortham | Smithsonian Magazine

“For all its power as a protest medium, black Twitter serves a great many users as a virtual place to just hang out. There is much about the shared terrain of being a black person in the United States that is not seen on small or silver screens or in museums or best-selling books, and much of what gets ignored in the mainstream thrives, and is celebrated, on Twitter. For some black users, its chaotic, late-night chat party atmosphere has enabled a semi-private performance of blackness, largely for each other.”

Javier Muñoz of Hamilton Has Been Reborn, Over and Over and Over Again

Taffy Brodesser-Akner | GQ

“Javier’s life story—the mere fact that he’s even still here at all—might explain his open-heartedness, his refusal to take his good fortune for granted. But it could just as easily explain the opposite. Brushes with death don’t always bring out the best in people; sometimes the fear of mortality, of throwing away your shot, or having it taken from you, can wreck a man, harden him into chasing glory at the cost of his soul. Javier nearly had his life taken from him, twice.”

The Stinky Cheeseman Introduces Kids to a Postmodern Landscape

J.J. Anselmi | The A.V. Club

“The Stinky Cheese Man finds momentum as much from its illustrations, which convey a similar ghoulishness as the characters in The Nightmare Before Christmas, as its text. A cow’s jaw unnervingly drops as if made of clay, and the fox’s toothy grin is the stuff of bad dreams. In the end, the small man made of malodorous cheese gets discarded into a river, where he falls apart. No lessons about not trusting strangers here: just a few lumps of cheese that dissolve in water.”

Vince Staples Remains More Reality Than Television on Prima Donna EP

Matthew Ramirez | SPIN

“True to everything he’s ever put on record or said to the press, Staples is a pragmatist. He neither romanticizes violence nor outright condemns gang life; he doesn’t linger on its brutality to valorize the struggle or revel in it for authenticity points. He’s a chronicler who puts his thoughts at the forefront of his stories, like a great first-person essayist.”

Carly Rae Jepsen, the Most Useful Pop Star

A Carly Rae Jepsen song is an irony-free zone. Unlike with the Beyoncés and Taylor Swifts of the world, are no meta-narratives about fame and personal lives to untangle, no satirical winks, and few expeditions to unexpected musical traditions. It’s just 2010s pop technology recreating 1980s pop carefreeness, reliably spitting out giddy, deeply felt, and well-crafted tributes to such simple things as falling in love, falling out of love, and …

Going to the store!

Those little videos above and all the other ones like them online are the result of the Internet discovering the fabulous utility of “Store,” from Jepsen’s new collection Emotion: Side B. The song is technically about walking out on a relationship by saying you’re going out to pick up some seltzer or something, but really it’s destined to become a soundtrack for actually just going out to pick up seltzer or something. Those hard string jolts, that jock-jam rhythm, the way Jepsen yelps “store” as “stoh” (?)—it’s music to skip to, and unlike most such music, it describes a mundane activity you might well be doing as you listen.

Jepsen is a very good songwriter of the mundane, putting little images and unique but simple phrases into her love stories to make memorable. Her mega-smash debut, “Call Me Maybe,” hinged on one word, “maybe,” that’s underused in pop music but overused in real life. “Store” is similar in that attention to relatable detail, as are the other seven songs on Side B, an add-on to her great 2015 release Emotion. It’s her most consistent and unapologetically retro group of songs yet—the highs are not the highest of her career, but there’s not an un-strutworthy song in the bunch.

Jepsen hints at her make-’em-feel-and-make-’em-move mentality of the album with the Flashdance bounce of “Body Language,” where she keeps cautioning a lover, “I think we’re overthinking it.” “First Time” sets you up for a “Like a Virgin” theme but actually uses the theme to describe heartbreak. “Higher” cribs its aching verse melody from “How Will I Know,” which is no sin at all. The dewy synths on “Fever” evoke a hot summer night as Jepsen narrates a very emotional bike ride. And it’ll be a shame if the excellent ballad “Cry” doesn’t inspire at least one prom slowdance singalong next year.

The “Store” videos represent the third or fourth great meme the Internet has made from Jepsen—there were all the “Call Me Maybe” covers back in 2012, the Vine jokes featuring the glorious sax peal from 2015’s “Run Away With Me,” and there’s also a running gag where people call her “the queen of” various ridiculous kingdoms. It’s all a sign of how Jepsen inspires a unique kind of ferocity. She’s chart pop’s great underdog: Despite two and a half wonderful albums, she’s nowhere near shrugging off “one hit wonder” tag in the mass consciousness, perhaps due to the endearing fact that she just wants to sing rather than conquer all media formats and dominate all conversations. Jepsen simply makes music to live with—a gift for the pop listener, the kind you can’t just go out and buy.

September 2, 2016

The End of Antibacterial Soap

NEWS BRIEF The Food and Drug Administration on Friday banned soap companies from using more than a dozen chemicals in antibacterial soaps, citing the possibility they could have harmful side effects.

Regulators also say there is a lack of evidence that soaps with antibacterial chemicals are more effective than soaps without them. The FDA, in a statement, said:

Companies will no longer be able to market antibacterial washes with these ingredients because manufacturers did not demonstrate that the ingredients are both safe for long-term daily use and more effective than plain soap and water in preventing illness and the spread of certain infections.

The new FDA mandate targets two ingredients that are widely used: triclosan and triclocarban, reports the Associated Press. Previous animal research has shown those chemicals can encourage drug-resistant bacteria and affect hormone levels.

The FDA has scrutinized the soaps for years. In December 2013, the FDA proposed that companies prove their soap products were safe and more effective than plain soap. A study in November 2014 linked the chemical triclosan to tumor growth.

According to the FDA, some companies are already removing the chemicals from their products. The FDA has not yet ruled on hand sanitizers. While some use antibacterial chemicals, many of them use alcohol instead.

The Light Between Oceans Is Sympathy-Defying Melodrama

The tragic weepy can be a tough genre to sit through, but sometimes being put through the emotional wringer is a deeply satisfying experience. Derek Cianfrance’s new melodrama, The Light Between Oceans, wants to oblige, but only if viewers submit themselves to another kind of agony: watching characters make bad, bad decisions. At times, the film is a powerful, pensive work about loneliness and human connection. But the movie errs most with its main plot, which requires the characters to behave with utmost stupidity, sacrificing its hard-earned storytelling for a frustrating payoff.

It’s unfortunate, because The Light Between Oceans, based on a novel by M. L. Stedman, starts off by selling its central romance beautifully. Michael Fassbender plays Tom, a World War I veteran who takes a job as a lighthouse-keeper in Australia; Alicia Vikander plays Isabel, the local girl who falls for his impenetrable stoicism. Their courtship and marriage is charmingly inevitable. Cianfrance repeatedly bombards the audience with beautiful ocean vistas, but it’s clear things have to turn dark at some point. Then a baby washes ashore in a rowboat, accompanied by a dead man, and Isabel and Tom are faced with a painful dilemma that only leads to predictable misery—for both them and the viewer.

Stedman’s book is slightly more focused on Tom’s distress about his part in the war, which fuels his desire to be as far away from people as possible. Wisely, Cianfrance opts not to use voiceover narration, since Fassbender’s perpetual empty stare is more than enough to communicate his feelings. Tom seems perfectly content to sail off to a remote island and man its lighthouse, a self-appointed act of solitary penance for whatever happened in the trenches. But Isabel, the daughter of his employer, takes an immediate shine to that steely gaze and clenched jaw, and the romantic die is cast.

The opening act of the film is where Cianfrance succeeds at capturing the melodramatic air that these kinds of stories live or die by. Tom and Isabel first flirt by correspondence, writing each other letters of restrained admiration as the waves crash around them and Alexandre Desplat’s paint-by-numbers piano score builds on the soundtrack. The dialogue is sparse, the imagery lovely, and Fassbender and Vikander both excel at conveying emotion with a furtive glance and a tremble of the lower lip. When the two quickly marry and Isabel moves to the lighthouse, it’s easy to be on board; when Isabel then suffers two painful miscarriages, it’s genuinely sad, and the isolation of the lighthouse goes from feeling tranquil to oppressive.

All of this build-up (and it’s a long build-up, more than 45 minutes of the film) exists to try and justify the extreme decision Tom and Isabel make when a rowboat washes ashore, bearing a dead man and a living newborn baby girl. Isabel, recovering from a miscarriage she suffered just days earlier, begs Tom to let her keep the baby and pretend that it’s hers. Tom knows it’s a bad idea, but accedes out of love for his wife, and the film switches from a gentle romance to a high-stakes tragedy. Every scene, even if it’s just Tom playing with his new daughter on the beach, feels ominous. When the family makes a trip to shore and a grief-stricken wraith clad in black (Rachel Weisz) enters proceedings, viewers sense what’s coming: This is the girl’s real mother, who lost her husband and child at sea, and she brings the righteous forces of misery with her.

Weisz, another extraordinary performer, does what she can with the appropriately aggrieved Hannah, but she’s nothing more than a plot device. Hannah is merely an avatar of Tom and Isabel’s guilt, and the film’s quiet, if ponderous romanticism gets swept aside for a series of brutal recriminations and further bad decision-making. Tom’s introversion transforms into an irritating impassiveness; Isabel’s desire to have a child becomes an almost monstrous lack of empathy. Cianfrance handled similar adversity with more compassion in his previous films, the dark romantic drama Blue Valentine and the sprawling family epic The Place Beyond the Pines, but here, it can’t rise past the level of a chintzy made-for-TV movie.

The heartbreaking decision Tom and Isabel make to keep the baby that washes ashore, is the dramatic hinge of Stedman’s story, and of course Cianfrance wasn’t going to excise it from his script. But despite his best storytelling efforts, he can’t sell their choice as a remotely sympathetic one, and so, as Tom and Isabel’s problems mount, it’s harder to feel invested in their struggle. The Light Between Oceans does finally find its way to a more muted, moving conclusion, but not before a series of eye-rolling twists including a murder investigation and a dramatic search for a runaway child. By the time viewers get to the film’s tear-inducing coda, they may be too exhausted and frustrated to care.

Is Food the Greatest Art Form of All?

The tendency with a show like Chef’s Table—a series that frequently delivers high-definition shots of sumptuous, immaculately presented meals—is to refer to it as “food porn,” lumping it in with, say, late-night Arby’s ads, or BuzzFeed videos of Oreos being smothered with molten cheesecake. Food porn is omnipresent these days; it’s excessive, it’s wanton. It’s strings of cheese glistening in slow motion while a pizza is pulled teasingly apart, or endless layers of roast beef collapsing gracefully onto a bun, pink and exposed.

But Chef’s Table, whose spinoff, Chef’s Table: France, debuts Friday on Netflix, is as far removed from such lowbrow gluttony as Guy Savoy is from Guy Fieri. For one thing, the documentary series, which spends each 50-minute episode profiling some of the world’s most extraordinary chefs, isn’t really about food at all—it’s about art. More explicitly, it’s about the strange and seemingly random circumstances that coalesce to produce unparalleled creative talents. The show focuses on each subject’s history not to pad out each episode with personal detail, but to reveal how much great food is a product of the soul of the person who made it. “A cuisine reflects what you have inside of you,” says the French chef Adeline Grattard in one new episode. “It’s an expression of your inner life.”

That such thoughtfulness is accompanied by close-ups of impossibly extravagant dishes—glossy squid enveloped by wafer-thin slices of cucumber and sweet-potato noodles, an improbably engineered chocolate millefeuille—is what makes the show so compelling. And oddly soothing. As with PBS’s The Great British Baking Show, there’s something remarkably calming about watching humans execute dazzling feats of culinary ingenuity from the comforts of the couch. Each moment of high drama ends in happy resolution; each difficult period in a chef’s life is revealed to have buffeted his or her genius in some way.

While two previous seasons have featured chefs all over the world, from remote Patagonian islands to downtown Melbourne, this iteration focuses on France. It makes sense: France is the birthplace of haute cuisine, the Michelin Guide, Escoffier. But Chef’s Table: France seems determined to disrupt the art of French cooking, focusing on chefs who are subverting the country’s traditions in their own distinct ways. The first episode focuses on Alain Passard, who shocked the Paris food scene when he took meat and fish off the menu at his three-starred restaurant L’Arpège. The second follows Alexandre Couillon, who created a culinary destination out of his isolated, water-locked village. The third is dedicated to Grattard, whose fusion of French and Chinese cooking became an unlikely hit in a tiny Paris teahouse called Yam‘Tcha. And the last features Michel Troisgros, a chef in the small town of Roanne wrestling with his father’s legacy.

The final episode is directed by the show’s creator, David Gelb, and it seems to have the most direct parallels to Gelb’s stunning 2010 debut documentary, Jiro Dreams of Sushi. That film, which almost certainly inspired Chef’s Table, followed the 85-year-old artisan working in a 10-seat Tokyo sushi restaurant with three Michelin stars. Jiro’s incomparable creativity, his fanaticism, his lifelong quest to perfect sushi as an art form, and his complex relationship with his two sons made the movie a critical hit. Chef’s Table shares many of its best qualities—a meditative, almost loving treatment of its subjects; stunning visuals; and a meticulously selected soundtrack (the theme is taken from Max Richter’s interpretation of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons). But above all, the show has Jiro’s deep curiosity when it comes to craft. How does a dreamer turn visions into food? How can something so ubiquitous—the simple act of eating—become something akin to a religious experience?

Most great art, after all, exists to appeal to a single sense. But food works to entice all five: sight, sound, smell, touch, taste.

The subjects of Chef’s Table: France have varied backgrounds and histories, but what each has in common is a desire to translate experiences into food. Troisgros, while visiting Italy, happened across an exhibition of work by the founder of Spatialism, Lucio Fontana, and became fixated on replicating Fontana’s signature slashed canvases into a dish composed only of milk and black truffle. Couillon’s experiments with seafood stem from an impulse to capture the essence of his remote island, Noirmoutier, on the plate: One of his dishes is a crunchy seaweed with oyster cream, another incorporates squid-ink broth to imitate the disastrous effects of an oil spill on local habitats.

This particular brand of particular innovative genius—with a touch of lunacy—has surely been part of culinary pioneering throughout the ages (consider, if you will, the absurd bravery of the first person to pry open and guzzle an oyster). The joy of watching Chef’s Table: France is to see how vividly impossible visions or abstract thoughts can become works of art, as intensely flavorful as they are visually striking. Most great art, after all, exists to appeal to one or two senses. But food works to entice all five: sight, sound, smell, touch, taste. These four episodes offer a compelling case that in crafting such exquisite and fleeting experiences, the most singular chefs are staking their claim as the greatest artists of all.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower