Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 84

September 6, 2016

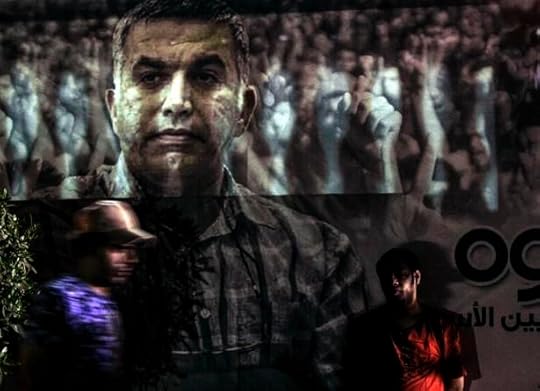

The Detention of a Bahraini Human-Rights Activist

NEWS BRIEF The U.S. State Department has called on Bahrain to release the human rights-activist Nabeel Rajab, who is currently facing 15 years in prison for posting statements on Twitter that Bahraini officials say are critical of government. Authorities reportedly handed down more charges Monday after Rajab published a letter in The New York Times criticizing the country.

“We’re very concerned—both about his ongoing detention and about the new charges filed against him,” State Department spokesman Mark Toner said Tuesday. “We call on the government of Bahrain to release him immediately.”

Rajab was arrested in June 2015 for tweeting criticism of both the Saudi-led coalition’s military operations in Yemen, of which Bahrain is an active member, and the condition of detainees in Bahraini prisons. The Gulf monarchy accused Rajab of deliberately spreading “false or malicious news, statements, and rumors,” a crime which carries up to 10 years in prison. He also faced charges of “offending a foreign country,” which carries a possible two-year sentence, and “offending national institutions,” which carries up to three years in prison. Rajab faces 15 years in prison. It’s unclear how more charges will affect the potential penalty.

The latest charges against Rajab came Monday after the activist published a “Letter From a Bahraini Jail” in the Sunday edition of The New York Times. Bahraini officials say the op-ed includes “false news and statements and malicious rumors that undermine the prestige of the kingdom,” the Times reported, citing the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, a watchdog group. Rajab wrote:

The government has gone after me not only for my comments on Yemen, but also for my domestic activism. One of my charges, “insulting a statutory body,” concerns my work shedding light on the torture of hundreds of prisoners in Jaw Prison in March 2015. The State Department has highlighted the same problem, but last year lifted the arms embargo it had placed on Bahrain since the repressions that followed the 2011 Arab Spring protests, citing “meaningful progress on human rights reforms.” Really?

...

Recent American statements on Bahrain’s human rights problems have been strong, and that is good. But unless the United States is willing to use its leverage, fine words have little effect. America’s actions, on the other hand, have emboldened the government to detain me and other rights advocates: Its unconditional support for Saudi Arabia and its lifting of the arms ban on Bahrain have direct consequences for the activists struggling for dignity in these countries.

Human Rights Watch, where Rajab is a member of the organization’s Middle East advisory committee, called on the Bahraini government to suspend its prosecution of Rajab, arguing the charges against him violate his right to freedom of expression.

“Bahrain keeping Nabeel Rajab in a prison cell for criticizing abuses shows the ruling Al Khalifa family’s deep contempt for basic human rights,” Joe Stork, the deputy Middle East director for Human Rights Watch, said Sunday in a statement. “States that claim to support peaceful activism should use the Human Rights Council session to demand Rajab’s immediate release. And they should push Bahrain to lift the restrictions placed on Nabeel’s colleagues.”

Rajab said he is one of 4,000 political prisoners currently detained in Bahrain. The Gulf country has the highest prison population rate per capita in the Middle East.

Atlanta’s Magic Is in the Details

For me, Atlanta is partly mythical. It’s a place where urban legends sit next to you on the MARTA bus; where supercars from rap songs break the sound barrier on lazy interstates; where business meetings, graduation parties, and radio shows coincide at strip clubs; where goat pens and international banking headquarters share neighborhoods with condominiums and subsidized housing; and where roads named after southern icons of civil rights cross roads named after southern icons of the Civil War. Years ago, it was the place where I sat as a country-bumpkin college freshman glued to the television watching the local news, enthralled with the idea of black weathermen and stock analysts. It’s the city that demanded the music world’s attention after André 3000 told the world that the South had something to say. Atlanta is a magic city.

Through the four episodes that I’ve watched so far, Donald Glover’s new FX show Atlanta manages the herculean feat of portraying all of that magic, and plenty more. The show seems solely dedicated to portraying the peculiarity of the city at first, name-dropping a ridiculous amount of hotspots and traveling at warp speed between rural, urban, and suburban sets. But along with rapid-fire references to (and portrayals of) famous strip clubs and restaurants, its 30-minute episodes deliver characters who navigate their own American dreams, all while beginning to outline a mythology of the hip-hop renaissance that has defined the city as much as anything else since the ’96 Olympics.

Glover’s Earnest “Earn” Marks is a character who can only exist in the city—a nerdy Princeton drop-out working at Hartsfield-Jackson airport who’s also a homeless deadbeat dad trying to connive his way into the rap game as a manager—and his eclectic cast-mates are just as unique. Brian Tyree Henry plays “Paper Boi” Miles, Earn’s cousin and a rapper who lives in the stereotypical “trap” and sells drugs to fund his career, but also struggles with the ramifications of his own caricature. Darius, played by Keith Stanfield, is a Nigerian American weedhead-mystic who plays the part of Paper Boi’s hype man. Zazie Beetz rounds out the cast as Van, Earn’s love interest who’s already the mother of his child and puts in the emotional labor of supporting his antics while also harboring her own entrepreneurial ambitions.

The series juxtaposes the surreal elements of Atlanta with the real problems in different characters’ daily lives. Earn becomes a rap manager in short order, but he still struggles with money. His lofty ambitions play well in the black-lit glow of the city, but sound hollow, arrogant, and self-serving in the light of day when he explains to Van why he can’t provide for his daughter. Following in the tradition of several prominent Atlanta rappers like Gucci Mane, Paper Boi soon finds himself in trouble with the law. This actually kickstarts his career, and further advances him within its constellation of minor and major stars, but it deeply troubles his conscience in real life as he marinates on his career in a neighborhood off Edgewood. While many shows and films about music feature similar contradictions between the glitz and the grit, in the world of Atlanta they feel like natural extensions of the city itself.

Those contradictions are key in telling what appears to be the main arc of the show: It’s an origin story of hip-hop. While it’s obviously not the cosmological origin of Baz Luhrmann’s The Get Down, which is a coming-of-age story of a group of teenagers in the Bronx during the birth of the art form, the two share a bit of DNA. The Get Down is also mired in the strangeness of a founding myth, although most of it is attributable to Luhrmann’s distinctive brand of fiction, as opposed to the character of the Bronx itself. The magic of The Get Down is alchemy: characters transmute the pain of their marginalized lives in the lower-class Bronx, and in the process transmute disco into hip-hop via the philosopher’s stone of the turntable.

The magic of Atlanta so far is also alchemy; only this time the substance being transmuted is hip-hop itself.

The magic of Atlanta so far is also alchemy; only this time the substance being transmuted is hip-hop itself. It’s no secret that the past two decades of hip-hop history have seen the balance of power shift south from New York City. The mythologizing of Atlantan hip-hop stretches beyond the immortal dope boys of Outkast to T.I.’s Chevrolet-riding menace to Gucci Mane’s drawling picture-painting. Each of these titans played a part in the southern renaissance of hip-hop, changing the art in new and radical ways. The presence of that renaissance overwhelms today on the radio, just as it makes its mark on Glover’s characters.

For a person who fell in love with that renaissance, Atlanta reaches almost fan-service-levels of gratuitous references and déjà vu. Whether the show will land with similar joy to those unfamiliar with the city is something I’m not equipped to say, but the level of dedication to scene and place are clear marks of care from Glover and help underscore the social energy and zeitgeist of a city that is clearly in the process of creation.

The Trial Date for Bill Cosby

NEWS BRIEF Bill Cosby will go on trial for sexual-assault on June 5, 2017, two years after a slew of women began claiming that the comedian drugged and raped them.

Pennsylvania Judge Steven O’Neill set the tentative trial date at a preliminary hearing Tuesday. The 79-year-old actor will face three counts of felony aggravated indecent assault against one of those women at the trial next year.

Cosby has been accused of drugging and raping a former Temple University employee at his home in 2004. Andrea Constand claims Cosby gave her cocktail of wine and pills that left her incapacitated and incapable of consenting to sexual contact. Cosby pled not guilty to the charges in December.

Prosecutors are hoping to include other testimony against Cosby. CNN explains:

The judge also said the district attorney filed a motion saying he intends to present 13 alleged prior instances.

Rule 404(b) of the Pennsylvania Rules of Evidence allows prosecutors to call witnesses about a defendant's previous conduct if it relates to the trial at hand.

The women who might testify are not named in the motion, but more than 50 have come forward in recent years to say Cosby sexually molested them.

O’Neill did not say when he would rule on this latest motion. Cosby’s lawyers also plan on filing a motion in the next 60 days to move the trial venue from Norristown, Pennsylvania, to another city.

This is the first time Cosby, a popular television star most known for sitcom The Cosby Show, is being charged with sexual assault. Dozens of women have come forward since 2014 and accused Cosby of drugging and raping them. He has denied any wrongdoing.

Characters Don't Change, but Readers Do

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

In the 1970s, Alice Mattison made a decision that would transform her life: She hired a babysitter to care for her infant son, which gave her two two-hour shifts a week in which to write. At first she worked only in the basement of her house, her typewriter keys clacking over the rumble of the washing machine, stopping every now and then to fold laundry between paragraphs. It didn’t matter that outward successes were few and far between—the fact that she earned only $35 for her first published poem, or that it took three years to publish another. “The time in the basement changed me,” she writes, in the introduction to her new book The Kite and the String. “Writing emerged, dominant, undeniable.”

But it wasn’t until she discovered Grace Paley that Mattison gained the confidence to write fiction. In a conversation for this series, she explained how Paley’s stories—short, nimble, free-wheeling, conversational—get away with breaking all the rules. We discussed Paley’s classic “A Conversation with My Father,” which demonstrates how a short story without a conventional plot can nonetheless feel complete, and why the old axiom that a characters must undergo fundamental change isn’t necessarily true.

The Kite and the String, a book-length master class that draws on years of teaching, reading, and first-hand experience, argues that good writing is all about balance: the kite-like creative unconscious also needs a steady set of hands manning the line. Alice Mattison is the author of six novels (most recently, When We Argued All Night) four story collections, and three books of poetry, and her work appears in venues like The New Yorker, Ploughshares, and The New York Times. She teaches creative writing at Bennington College, and spoke to me by phone.

Alice Mattison: When I discovered Grace Paley, I had little kids, I was teaching part-time, and I was writing poems—sending them out and getting them rejected. I don’t think I was ambitious enough to think that I might one day be a writer. I was thinking, “Maybe I’ll get that poem published." And: “Maybe eventually I could learn to write a story.” I had a dream of writing fiction, but I didn’t know how. Most of the short stories I’d read were by James Joyce or Henry James, and I wasn’t going to write stories like that.

Then I took Grace Paley’s book The Little Disturbances of Man from the public library. I remember where I was sitting as I read the book. And as I read, I began to think maybe I could write short stories. It could have been because she was a woman, or because she wrote about ordinary life—not about Europe, not about people of wealth and stature. These stories were about urban people, some of them Jews, like me. She was frank about her politics in her fiction; that mattered to me. The ordinariness spoke to me.

From Paley, I learned that I could write about lives and feelings like those I knew. Also that I didn’t have to imitate a 19th-century writer to structure stories. Her stories didn’t have elaborate, suspenseful plots. And yet, for a long time after I encountered her, the stories I wrote weren’t really stories. Paley’s stories have little plot, but are complete. In mine, nothing happened at all. I didn’t understand the difference between an incident and a short story.

How can you write a complete story without a conventional plot? We often hear that in short stories, the main character must change. But in some stories, including some by Grace Paley, the characters don’t change. Instead, her stories change the reader. You’re different by the time you reach the end.

Paley’s story “A Conversation with my Father," is an example. The narrator’s father is on his deathbed—we learn that right at the beginning. He’s having trouble with his lungs, and he’s on an oxygen machine. And he complains to his daughter, the narrator, about the stories she’s been writing.

“I would like you to write a simple story just once more,” he says, “the kind de Maupassant wrote, or Chekhov, the kind you used to write. Just recognizable people and then write down what happened to them next.”

Sure, the daughter thinks. She can do that. As she puts it:

“I want to please him, though I don’t remember writing that way. I would like to try to tell such a story, if he means the kind that begins: ‘There was a woman ...’ followed by plot, the absolute line between two points which I’ve always despised. Not for literary reasons, but because it takes all hope away. Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life.”

What she says is wonderfully contradictory. “Why not?”, she thinks—but, at the same time, she says she despises the very idea of such a story.

The narrator makes up a story about a woman who becomes a heroin addict in solidarity with her son, who is a heroin addict. He gets clean, and she does not, and she loses him. The father is upset with the story—and he’s right, the first version is just bare bones. So she expands it and tells the story again, explains what it is that attracts the son about drugs, what it’s like for him as an addict, how a woman convinces him to get off drugs and eat healthy, organic food. It’s all very interesting. There are more details in the second version, but the outcome is the same.

The father doesn’t like the second story either, except for one part: its final words, “The End.”

“The end. You were right to put that down. The end.”

I didn’t want to argue, but I had to say, “Well, it is not necessarily the end, Pa.”

“Yes,” he said, “what a tragedy. The end of a person.”

“No, Pa,” I begged him. “It doesn’t have to be. She’s only about forty. She could be a hundred different things in this world as time goes on. A teacher or a social worker. An ex-junkie! Sometimes it’s better than having a master’s in education.”

“Jokes,” he said. “As a writer that’s your main trouble. You don’t want to recognize it, Tragedy! Plain tragedy! Historical tragedy! No hope. The end.”

And we’re reminded of what’s really going on. Their argument becomes about more than storytelling. The narrator still believes in “the open destiny of life.” The father can’t. And he’s dying. The father and daughter will be separated forever, like the mother and son in the story. The reader, at this point, may have forgotten that fact—the oxygen machine—but then the father puts the tubes back into his nostrils and it hits us: she’s going to lose him.

In this story I think neither character changes. The father is stuck in his perspective, and the daughter remains faithful to hers. This “conversation” is less a dialogue than two characters talking past each other. But there is a shift, and that’s what makes the story—it’s just that it happens in the reader, not in one of the characters. We don’t expect to agree with the father: he thinks the story that his daughter tells is tragic because the woman in it won’t change. We—agreeing with the daughter—feel that life has more possibility than that. But then Paley ends the story with the dying father’s accusation that her daughter won’t look tragedy in the face. We feel the tragedy of the father and daughter’s separation, the inevitability of his death. Our perspective shifts toward his: we change.

I had never really thought that in a story the protagonist always changes, but I couldn’t have explained why until I met a student I taught about ten years ago. Her name was Catherine. She was interested in alcoholism: many of her characters were drunks who couldn’t reform. She’d been told many times that in a story the protagonist always changes. This made her angry—it was contrary to something she knew about life. Why couldn’t she write stories about those drunks?

Catherine forced me to ask myself: What makes it a story if it’s not the protagonist changing? If a story says that Steve got drunk on Monday, and he got drunk on Tuesday, and he got drunk on Wednesday, and on Thursday, and on Friday—it obviously isn’t a complete story. But if on Wednesday, Steve thinks, Maybe I’ll give up drinking, and on Thursday he goes to an AA meeting, but doesn’t walk through the door, and on Friday he gets drunk again—that is a story. Because something shifts in us—we think he can change—and we understand.

You can start with the person you already are, whomever that may be.

On the most basic level, this is what a story consists of: Something happens, and then something else happens, and then you come to the end, and it makes you think—huh! That’s a stupidly simple formula, but it’s true. Something happens, and then something shifts. Something occurs that changes things from the way they are at the beginning, then brings them back to the way they were, or brings us and the characters somewhere altogether new. Of course, conventional plots often follow this formula: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl. But it’s also key to understanding unconventional stories like Paley’s, which are short and subtle and yet somehow complete. We need the feeling that we’ve gone a distance and then arrived somewhere. Often nothing changes for the protagonist, but something changes for the reader: we understand the characters in a new way.

Many of us grow up assuming that books are about places other than the one we live in, which is so familiar that it couldn’t possibly be in a book. Grace Paley taught me that I didn’t have to become someone else, from somewhere else, to write. That this girl from Brooklyn—which is what I am, from Brooklyn in the days when Brooklyn had no glamour—could write a story. I often ask my students where they grew up, and encourage them to read the writers from there. Sometimes it can be revelatory to realize that somebody actually put the town or neighborhood where you grew up into a book. But Grace Paley seems to be a good ancestor for a lot of people who aren’t New York Jews. She speaks to a great many new writers. And maybe what she’s saying is: you can start with the person you already are, whomever that may be.

The Minnesota Abduction Solved Nearly 27 Years Later

NEWS BRIEF The remains of Jacob Wetterling, the 11-year-old boy whose abduction in Minnesota nearly 27 years ago helped lead to the creation of a national sex-offender registry, have been found and identified through dental records.

The Stearns County sheriff’s office said Saturday Wetterling’s remains were recovered in a farm in central Minnesota. Police were led there by Danny James Heinrich, who on Tuesday confessed in court to kidnapping and killing the boy on October 22, 1989.

Wetterling, his 10-year-old brother, and an 11-year-old friend were biking home from a convenience store that day when a masked gunman stopped them. The assailant told Wetterling’s brother and friend to run, but forced Wetterling into his car and handcuffed him.

Heinrich led police to the spot where he buried the body near Paynesville, Minnesota, last week, the Star Tribune in Minnesota reported. Heinrich was charged last year with 25 counts of possessing and receiving child pornography. He spoke in court Tuesday after agreeing to a plea deal that cut the number of charges to one.

Heinrich’s retelling of the crime Tuesday was the first time the Wetterling family and the public heard about what happened to Jacob Wetterling. Heinrich said he drove Wetterling to an area near a gravel pit, led him out of the vehicle, uncuffed him, and molested him. More from the Star Tribune:

Jacob asked to go home, but Heinrich told him he couldn’t take him all the way home.

Jacob started to cry.

“I panicked. I pulled the revolver out of my pocket...I loaded it with two rounds. I told Jacob to turn around,” Heinrich said.

“I told him I had to go to the bathroom,” Heinrich said. “I raised the revolver to his head. I turned my head and it clicked once. I pulled the trigger again and it went off. Looked back, he was still standing.

“I raised the revolver again and shot him again.”

Search crews spent months looking for Wetterling, and a group of anonymous Minnesota business owners offered a $100,000 reward for his return. Wetterling’s parents, Jerry and Patty, created an advocacy group for children’s safety in Jacob’s name in 1990, three months after their son’s abduction. The Wetterlings began lobbying for the creation of a statewide registry for individuals convicted of sexual offenses in Minnesota. In 1994, the Jacob Wetterling Act became federal law, requiring all 50 states to create sex-offender registries.

“We are in deep grief. We didn’t want Jacob’s story to end this way,” the Jacob Wetterling Resource Center said in a statement Tuesday. “In this moment of pain and shock, we go back to the beginning. The Wetterlings had a choice to walk into bitterness and anger or to walk into a light of what could be, a light of hope. Their choice changed the world.”

The Stearns County sheriff’s office said Tuesday state authorities will conduct further DNA testing of the remains. The office said local and state law-enforcement agencies, as well as the FBI, are “currently in the process of reviewing and evaluating new evidence in the Jacob Wetterling investigation.”

Obama on Kaepernick: Sometimes Democracy Is 'Messy'

NEWS BRIEF President Obama was in Asia this weekend, focusing on his administration’s critical foreign-policy pivot to the continent. So, of course, he was asked about Colin Kaepernick.

The 49ers quarterback has a constitutional right not to stand for the national anthem, Obama said Monday, adding, “Sometimes it’s messy, but it’s the way democracy works.” The president explained why Kaepernick fired so many people up:

As a general matter, when it comes to the flag and the National Anthem, and the meaning that that holds for our men and women in uniform and those who fought for us, that is a tough thing for them to get past to then hear what his deeper concerns are. But I don’t doubt his sincerity, based on what I’ve heard. I think he cares about some real, legitimate issues that have to be talked about. And if nothing else, what he’s done is he’s generated more conversation around some topics that need to be talked about.

Since he began his protest against racial injustice two weeks ago, Kaepernick has sparked a national debate, not only about police brutality but also about how people should protest. He’s also been joined by a couple other football players.

Now, the protest is moving to a different kind of football. Megan Rapinoe, a star on the U.S. Women’s National Team, kneeled during the playing of “The Star Spangled Banner” during a National Women’s Soccer League game Sunday night between her Seattle Reign and the Chicago Red Stars.

@JohnDHalloran pic.twitter.com/XJHiOhgbTW

— ❤️NWSL⚽️ (@gbpackfan32) September 5, 2016

She said she was joining Kaepernick, who she said has been treated in a “disgusting” way, in his protest against racism in American society. She explained to American Soccer Now:

Being a gay American, I know what it means to look at the flag and not have it protect all of your liberties. It was something small that I could do and something that I plan to keep doing in the future and hopefully spark some meaningful conversation around it. It’s important to have white people stand in support of people of color on this. We don’t need to be the leading voice, of course, but standing in support of them is something that’s really powerful.

The World Cup winner said there needs to be a more substantive conversation surrounding race in the United States.

The Pointless, Nasty Spectacle of the Comedy Central Roast

The ostensible purpose of Comedy Central’s intermittent “Roast” specials has varied over the years. When the network began televising the classic Friars Club roasts of comedians like Chevy Chase or Denis Leary in the late ’90s, it offered fans an inside look at the back-patting boy’s club of stand-up, where comics would hurl insults at each other all in good fun. More recently, it’s evolved into a sort of extended mea culpa pulpit, an image-rehab opportunity for celebrities like Charlie Sheen, Justin Bieber, or Donald Trump to boost their reputation by proving they’re willing to “take a joke.” The newer roasts still allowed stand-ups to hone their skills at writing nasty jokes, but they were largely televised PR events. But with Sunday night’s Rob Lowe roast, the tradition seems to have entered a new era: one of utter irrelevance.

The roastmaster David Spade, who presided over the broadcast, summed up the pointlessness of the event early on when he said, “That’s right, we’re here to honor one of the biggest stars of 1987—with some of the biggest stars of 1984.” It’s hard to guess why Comedy Central decided to roast Lowe—he’s not exactly a ratings-grabbing name, and he has no upcoming projects to promote. But it makes sense why the most noteworthy part of the event was the cruelty lobbed at Ann Coulter, the conservative-media polemicist who inexplicably agreed to take part in the event and quickly became its most fascinating feature. If there was any narrative at all to the night, it was a surprising, unexpected one: Could Comedy Central viewers actually feel bad for Coulter?

Coulter, after all, has arguably based her entire profession on trolling TV viewers and political commentators with intentionally shocking, awful statements. To enumerate them all would be impossible—she’s less a pundit and more a vessel for free-associative hate speech, much of it recently directed against Mexican immigrants and Muslims living in the United States, all part of her devoted support for the Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump. Her newsmaking brand isn’t dissimilar from the approach to writing a roast-appropriate joke: Craft an insult that’s as vicious as possible but still ends on a laugh line, a wink to the audience that suggests the whole thing is all in good fun. Coulter, however, mostly lacks that final element—her defenders might claim that she’s just trying to push buttons, but her arena isn’t the world of stand-up.

Still, it makes some vague sort of sense that Coulter might work within the medium, and she was clearly eager to promote her new book In Trump We Trust, a copy of which she brought to the stage with her. But the main reason to include her was obviously so Comedy Central could court some controversy. Surely few people were truly excited about Lowe being cut down to size, but part of the format of the special is that the roasters also turn on each other. And so the odd grab-bag of celebrities on the dais all gleefully turned their fire toward Coulter. The softball jokes about Lowe’s lack of fame and decades-old sex tape scandal harmlessly bounced off of their target, but the jokes directed at Coulter were genuinely raw and angry, and she seemed bewildered by what was happening.

Part of the theater of the roast is appearing to be in on the joke—it’s why a big celebrity like Justin Bieber will take part, to claim the cachet of being able to shrug off a mean dig with a smile. Coulter, instead, responded to the lines with a sort of frozen, tortured grin, rendering the whole thing deeply uncomfortable. Much of the material was about her right-wing politics, with multiple roasters joking that she was part of the Ku Klux Klan. “Last year we had Martha Stewart, who sells sheets, and now we have Ann Coulter, who cuts eyeholes in them,” Saturday Night Live’s Pete Davidson said. Plenty more, though, was directed at her looks—a not-uncommon subject for any roast, but in this case featuring some truly brutal, wince-inducing lines. “Ann Coulter is one of the most repugnant, hateful, hatchet-faced bitches alive,” the British comic Jimmy Carr said. “But it’s not too late to change, Ann—you could kill yourself.”

Even comparatively “harmless” non-comedians jumped in: The retired quarterback Peyton Manning compared Coulter to a horse. (Many of the jokes at the roasts are scripted by off-stage writers, and this was no different.) The singer Jewel summed up the bizarre event when she joked, “As a feminist, I can’t support everything that’s being said up here tonight, but as somebody who hates Ann Coulter, I’m delighted.” When Coulter finally took the stage, she bombed hard in front of the hostile crowd, stammering through many of her lines, and vigorously plugging her book to loud boos.

While there will always be washed-up stars from the ’80s and fringe media figures who are happy to throw themselves on the pyre of cheap publicity, it’s hard to know who benefits from something like Coulter’s impromptu public shaming, except for comedians like Jeff Ross who specialize in the format and otherwise tweet “clever” jokes like this one.

RT if you would bang @AnnCoulter #LoweRoast

— Jeff Ross (@realjeffreyross) September 6, 2016

This is an era of comedy that’s increasingly suspicious of jokes that are cruel simply for cruelty’s sake, from the outrage over Kurt Metzger’s sexist tirades about rape culture to Daniel Tosh’s onstage rants at audience members. A few years ago, up-and-coming comics like Anthony Jeselnik, Whitney Cummings, and Amy Schumer established themselves as roasters before moving on to more thoughtful comedy, but it’s hard to argue now that the specials serve as a proving ground for young performers when the stage is crowded with figures like Coulter, Manning, Jewel, Spade, and The Karate Kid’s Ralph Macchio.

So it may be time to for Comedy Central to retire the roast. The only way that would likely happen would be if ratings cratered, but selecting throwback honorees like Lowe and promoting sadistic distractions doesn’t bode well for the network.

The Toppling of an Iconic Sandstone Formation in Oregon

NEWS BRIEF The Duckbill was popular among visitors to Cape Kiwanda along Oregon’s northern coast. Whether it was the subject of photos looking out into the Pacific Ocean or just something to climb, the 10-foot-tall limestone pedestal was an iconic part of the state park.

Now, the natural formation, shaped from centuries of erosion, is a pile of rubble after a group of vandals—as yet unidentified—toppled the landmark last month.

David Kalas was visiting the cape when he saw a group of eight people pushing the pedestal. Initially, he didn’t think they could topple it. But then, as it started moving, he began recording the incident, showing them succeeding:

The vandals explained their logic to Kalas, the videographer, which he relayed to KATU News:

I asked them, you know, why they knocked the rock down, and the reply I got was: their buddy broke their leg earlier because of that rock. They basically told me themselves that it was a safety hazard, and that they did the world or Oregon a favor.

After they toppled the rock, Kalas says they stood on the pile of shattered rocks “laughing, smiling, giggling.”

The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department says it is investigating the vandalism along with the Oregon State Police. If caught, the vandals could face fines of up to $435.

ITT Tech's Road to Closure

NEWS BRIEF The company behind ITT Technical Institute, the chain of for-profit schools in the United States, will shut down all of its campuses following financial sanctions from the U.S. Department of Education.

ITT Educational Services said in a statement Tuesday it would shutter more than 130 locations in 39 states. The move affects hundreds of thousands of current students and more than 8,000 employees of the ITT Technical Institute, known colloquially as ITT Tech, the company said.

“It is with profound regret that we must report that ITT Educational Services, Inc. will discontinue academic operations at all of its ITT Technical Institutes permanently after approximately 50 years of continuous service,” it said in a statement on its website.

ITT blamed the closure on the “actions of and sanctions from” the U.S. Department of Education. Last Thursday the government agency barred the company from enrolling new students using federal financial aid, a source of funding ITT Tech has relied on heavily. A day later, ITT announced it would not enroll any new students in the coming semester.

U.S. officials say ITT Tech has been found twice this year to be out of compliance with the standards of its accreditor, the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools. ITT Tech and for-profit colleges have been criticized for charging tens of thousands in tuition but failing to provide a valuable education to students, instead leaving them saddled with debt. As my colleague Bourree Lam reported in June, a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research this year found “on average, students pursuing bachelor’s and associate’s degrees at for-profit colleges saw their earnings drop, compared to before they started the program.”

“We made a difficult choice to pursue additional oversight in order to protect you, other students, and taxpayers from potentially worse educational and financial damage in the future if ITT was allowed to continue operating without increased oversight and assurances to better serve students,” said John King, the U.S. Secretary of Education, in a statement Tuesday.

ITT Tech enrolls more than 40,000 students in undergraduate and graduate programs. The Department of Education said Tuesday some students may be eligible to have their federal student loans discharged and their debt erased. They may also be able to transfer their ITT credits to another institution. “Whatever you choose to do, do not give up on your education,” King said.

In April 2015, Corinthian Colleges, another for-profit chain with hundreds of campuses across the country, shut down after similar sanctions from the federal government. The Department of Education offered to forgive millions of dollars of debt of thousands of students enrolled in the schools, on the grounds that Corinthian defrauded them.

Cleaning Up the Bombs From the Secret U.S. War in Laos

NEWS BRIEF President Barack Obama pledged $90 million on Tuesday to help Laos clean up millions of unexploded bombs the U.S. dropped on the country in a secretive nine-year bombing campaign during the Vietnam War.

Obama flew to Laos as part of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit, and his trip marks the first time a sitting U.S. president has visited the country. The U.S. already spends millions to help clean up the unexploded bombs, but this new announcement would double what the U.S. spends over three years. In his speech to a roomful of students and politicians Tuesday, Obama said, “Given our history here, I believe that the United States has a moral obligation to help Laos heal.”

The CIA led the bombing campaign, which dropped more than 270 million cluster bombs, or around 2 million tons of explosives, on villages and suspected supply routes from 1964 to 1973. That was more bombs than dropped on Germany and Japan combined during World War II. During the Vietnam War, Laos had officially remained neutral. But the U.S. believed communist groups in the country were helping to supply the North Vietnamese, particularly along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This is why the CIA carried out their missions in secret, without congressional approval. Of all those bombs, it’s estimated 80 million never went off, and dozens of Laotians die each year from unexploded ordnance.

Here’s a video by Agence France-Presse that talks about the danger these bombs still pose for Laotians.

Although Obama promised to send Laos more money to clear unexploded bombs, the president did not offer an apology for the secret war. Instead, Obama said, “Whatever the cause, whatever our intentions, war inflicts a terrible toll."

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower