Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 63

October 5, 2016

How Hollywood Whitewashed the Old West

As movie genres go, the Western is a workhorse. It draws from a well of cultural symbols meant to capture the essence of America, including the freedom of the open frontier and the righteous self-determination of man. Standing tall inside this cinematic shorthand is the cowboy himself, a figure commonly understood to be an excellent shot who rides horses and who, above all, is white. This narrow image is foundational to the genre, which includes films such as John Sturges’s 1960 classic The Magnificent Seven. A retelling of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, the movie centers on a group of seven white men hired to protect a Mexican village being terrorized by a band of outlaws.

But a new adaptation of the film offers a notably different set of heroes. Directed by Antoine Fuqua and starring Denzel Washington, the 2016 version centers around a team of misfits trying to defend a town built around a gold mine. In addition to Washington, the “seven” include Byung-hun Lee, Manuel Garcia-Rulfo, and Martin Sensmeier—all of whom subvert the conventional idea of the Western hero. But if anything, this subversion brings the movie closer to history: The Old West and the iconic cowboys who populate it in movies were never solely white to begin with. In recent years, filmmakers have grappled with this reality to varying degrees of success. Despite the admirable efforts of Westerns such as The Revenant and The Magnificent Seven, movies like Django Unchained, The Keeping Room, The Lone Ranger, and Bone Tomahawk all show how difficult it is to modernize the genre without continuing to peddle an inaccurate and exclusionary account of American history.

Cowboy culture refers to a style of ranching introduced in North America by Spanish colonists in the 16th century—a time when most ranch owners were Spanish and many ranch hands were Native. None of the first cowboys were (non-Hispanic) white. And while historians don’t know exact figures, by the late 19th century roughly one in three cowboys (known as vaqueros) was Mexican. The recognizable cowboy fashions, technologies, and lexicon—hats, bandanas, spurs, stirrups, lariat, lasso—are all Latino inventions.

White Americans wouldn’t be exposed to, and subsequently incorporate, cowboy culture into their ranching practices until 200 years after its inception, once westward expansion brought Anglo-colonists and African slaves into the area in the early 1800s. At that time, cowboys did the kind of hard labor that wealthy white Americans would often force others to do, meaning many were black slaves. Around this same time, the frontier was also populated by roughly 20,000 Chinese immigrants who contributed significantly to the development of the West, including the construction of the first Transcontinental Railroad. In other words, people of color were not only present at the inception of the Wild West—but they were also its primary architects. And yet, even today, black cowboys are fighting for recognition.

When filmmakers weren’t misrepresenting other races, they were often ignoring them entirely.

Most historians and cowfolk of color agree that Hollywood is responsible for popularizing the falsehood of the all-white Wild West. Filmmakers built a genre that hinged on racial conflict and then, in defiance of that fact, filled the silver screen with only white protagonists. While whitewashing remains a modern problem, it has a long history in American film: In the very first Hollywood movie, 1910’s In Old California, white actors played non-white roles.

This practice was especially commonplace in Westerns, which relied on racist stereotypes of Native people as bloodthirsty savages and drew inspiration for stories about white heroes from the experiences of freed slaves in the West. The story of one of America’s most eminent frontiersmen, Jim Beckwourth, formed the basis for 1951’s Tomahawk, which starred a white actor even though Beckwourth was black. The famous 1956 Western epic The Searchers was based on a black man named Britt Johnson. He was played by John Wayne, one of the genre’s biggest movie stars, who in 1971 told Playboy, “I believe in white supremacy until blacks are educated to the point of responsibility.” Even the fictional character of the Lone Ranger (who originally debuted in a radio show in 1933) shares striking similarities to Bass Reeves, believed to be the first black U.S. Deputy Marshal west of the Mississippi.

By the time Westerns gained wider prominence with movie audiences in the 1950s, the ubiquity of the genre’s all-white protagonists had helped fully obscure the reality of race on the American frontier. Crucial to this effort were directors like Cecil B. DeMille (The Squaw Man, Rose of the Rancho, The Trail of Lonesome Pine, The Buccaneers) and John Ford (My Darling Clementine, Fort Apache, The Searchers). Non-white characters were usually antagonists with names like “Mexican Henchman” or “Facetious Redskin.” When filmmakers weren’t misrepresenting other races (whether intentionally or not), they were often ignoring them entirely: Ford’s 1924 opus The Iron Horse manages to tell the story of the country’s first transcontinental railroad without Chinese actors, save a few who were background extras.

Over the next few decades Hollywood would occasionally cast a black cowboy to appear alongside otherwise all-white casts in Westerns such as Lonesome Dove (1989) or Unforgiven (1992). In a 1993 Chicago Tribune article about Beckwourth, the writer commended the aforementioned films for their palatable diversity while criticizing 1993’s Posse for being “too politically correct” with its all-black cast (which, historically, would have been more plausible). Both before and following the Civil War, many black men fled to the frontier for a cowboys’s life of freedom. The broad notion of “freedom” stitched into the seams of the Western canon has far more cultural significance than the genre has ever truly acknowledged.

If the Western genre is to evolve, then its scope must first be widened.

Whenever Westerns spring back into relevance, they resort to the same habits of misrepresentation. The result is that racial ignorance has been stratified, brick by brick, into the foundations of the genre on the groundless basis of “historical accuracy.” So what happens when a modern Western tries to remain faithful to genre conventions while being less regressive on issues of race?

Viewers wind up with an ouroboros like The Hateful Eight, a film Quentin Tarantino intended as commentary on American racial inequity, made with the art form that helped edify it. The movie’s predecessor, Django Unchained, is also supposedly a revisionist Western, but the title character (played by Jamie Foxx) is inert until the white hero Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) takes Django and guides him forward. The Keeping Room (2014), set at the close of the Civil War, was billed as a “feminist, revisionist” movie but clumsily equates the problems white women face with those endured by enslaved black women. In one cringe-worthy moment, the sullen Louise (Hailee Steinfeld) calls Mad (Muna Otaru) the n-word, at which her older sister Augusta (Brit Marling) snaps: “I done told you, Louise. We all niggers now.”

Such films have a difficult time critiquing the systemic power imbalances that helped usher the genre into being, despite the intentions of those involved. Tarantino said he wanted to “tap into” modern racial strife for The Hateful Eight, and the Keeping Room’s star, Marling, said of the film, “It’s an incredibly prescient movie in that this country is in some ways hopefully waking up to racism.” But both films depict racism through a white lens: In each, a black character experiences violence until a Caucasian hero steps in to enlighten the attacker. In this way, the films offer the same white-savior premise as 1960’s The Magnificent Seven without really critiquing it. But even these films are an improvement over works like The Lone Ranger (2013) and Bone Tomahawk (2015), which take the radically conservative approach and offer genocide so gratuitously violent that even Tarantino objects. In keeping with tradition, these films present racially motivated conflicts earnestly, and in The Lone Ranger, Johnny Depp plays the famously Native character Tonto.

If the Western genre is to truly reckon with its past, then Hollywood needs to start with the basics. Studios should hire more directors and writers who aren’t white, while more regularly seeking out stories about the American frontier that feature both characters and actors of color. This has already begun: The Revenant (2015), from the Oscar-winning Mexican director Alejandro González Iñárritu, was made with remarkable realism. It was meticulously researched, and the Native characters were played by Native actors. The film itself is was based on William Ashley’s 1823 expedition up the Missouri river, of which at least three black men were members (including, interestingly enough, Beckwourth).

The Magnificent Seven, too, has received attention for its “rainbow coalition” cast. The director Fuqua, for his part, has a sturdier grounding in American history than most of his forbears. “The west was a mixed bag of people coming from everywhere,” he told ScreenDaily. “It was more diverse than what we see in westerns.” But one of the biggest criticisms of the film has been that the characters of color are there “just for show” and inadvertently treated as tokens—a frequent flaw of “diverse” major-studio ensemble movies such as Suicide Squad. It’s unfair to expect a couple contemporary Westerns to reverse the genre’s legacy, but it’s heartening to see broader representation in big-budget films with all-star performers and famed directors at the helm.

In a Guardian interview, Denzel Washington tried to downplay the idea that The Magnificent Seven was trying to explore deeper or more serious themes. “The average person who’s paying to see it is just looking for a good time,” he said, adding that people go to the movies to escape. “It ain’t that deep.” So, too, decades worth of Westerns offered their own kind of escape from reality. At the turn of the 20th century, the country was trying to construct a new national identity following the end of slavery, and amid immigration and westward expansion. Through it all, stories about cowboys and renegades on horseback offered entertainment, but also fantastical utopias of white heroism. These tropes will always be part of the genre’s past. But Hollywood’s gradual efforts to extend more opportunities to people of color and to—hopefully—learn from its mistakes, may prompt more viewers to eventually see the all-white Wild West for what it is: fiction.

Poland's Increasingly Unpopular Abortion Ban

NEWS BRIEF Widespread protests over a proposed abortion law in Poland have led to a shift in political opinion, and some conservative politicians now say they will no longer support the legislation.

Thousands of women, dressed in black, marched in the streets of Polish cities earlier this week, waving black flags and holding black umbrellas. They protested the proposed law, which would ban abortion in all cases, including incest, rape, or when birth risks a mother’s life. Current law, one of the strictest in Europe, makes exceptions for these cases.

Police estimated more than 17,000 women joined protests in Warsaw alone, and Reuters estimated it at 100,000 nationwide. On Wednesday, the Minister of Science and Higher Education, Jarosław Gowin, said the massive demonstrations forced him and other conservative politicians to rethink the abortion regulation, and that protesters “taught us humility.”

The law, proposed by the ruling right-wing Law and Justice Party, would include a penalty of up to five years of jail for women who receive abortions and for the doctors who carry out the procedure.

Beata Szydlo, Poland’s prime minister and the leader of the Law and Justice Party, backed away from the proposed law after the protests Monday (she has previously said she supported the measure). On Tuesday, when Witold Waszczykowski, the foreign minister, called the protests a “mockery of important issues,” Szydlo said she disapproved of such comments and that not every member of her party backed the proposal. The party won strong support from women last year when it came to power, but after this week seemed to be at risk of losing female supporters. From Reuters:

Such criticism matters for PiS, whose appeal is based on a blend of Polish nationalism, Catholic piety and promises to help poorer Poles who have not benefited much from a decade of heady economic growth. Some 40 percent of women backed the party last year, compared to 38 percent of the wider population.

The Law and Justice Party won control of parliament last year. It is largely a nationalist, Euroskeptic, anti-immigrant party that is also staunchly pro-Catholic.

The Catholic Church has come out in favor of the law, which was inspired by a citizen-led petition that was taken up by parliament in September after it gathered more than 100,000 signatures. Newsweek Polska poll found 74 percent of citizens favor keeping Poland’s abortion laws as is.

Kid Cudi Sparks a Conversation on Depression, Race, and Rap

Reviewing Danny Brown’s new album Atrocity Exhibition yesterday, I wrote about how we’re in a moment when rappers like Brown are regularly defying stigmas against admitting to depression, addiction, and other mental-health issues. Wednesday brought another powerful example from Kid Cudi, the Ohio rapper known for songs like “Day and Night.”

He has checked himself into rehab for depression and suicidal thoughts, and he isn’t trying to hide it on. On Facebook he wrote,

Its been difficult for me to find the words to what Im about to share with you because I feel ashamed. Ashamed to be a leader and hero to so many while admitting I've been living a lie. It took me a while to get to this place of commitment, but it is something I have to do for myself, my family, my best friend/daughter and all of you, my fans.

Yesterday I checked myself into rehab for depression and suicidal urges.

I am not at peace. I haven't been since you've known me. If I didn't come here, I wouldve done something to myself. I simply am a damaged human swimming in a pool of emotions everyday of my life. Theres a ragin violent storm inside of my heart at all times. Idk what peace feels like. Idk how to relax. My anxiety and depression have ruled my life for as long as I can remember and I never leave the house because of it. I cant make new friends because of it. I dont trust anyone because of it and Im tired of being held back in my life. I deserve to have peace. I deserve to be happy and smiling. Why not me? I guess I give so much of myself to others I forgot that I need to show myself some love too. I think I never really knew how. Im scared, im sad, I feel like I let a lot of people down and again, Im sorry. Its time I fix me. Im nervous but ima get through this.

It’s a wrenching statement, and many on social media are reacting with well-wishes and admiration for his honesty, giving rise to the hashtag #yougoodman for people to discuss race, masculinity, and depression.

Mental health is a fraught subject regardless of who you are in American society—see Donald Trump’s recent comments about PTSD affecting soldiers who aren’t “strong.” But a lot has been written about the particular burden depression represents for people like Kid Cudi, who’s stepping away from the spotlight right as he’s about to release an album. “Tell a black man it's okay to show emotion today,” one popular tweet said this morning. “Tell a black man that ‘Strength’ isn't only physical. Tell a black man he can be depressed.”

Also on Twitter, users are sharing examples of rap songs “about black men and mental health.” The list that has resulted is a reminder of the fact that there’s been a recent boom in public expressions of vulnerability from artists like Kendrick Lamar and Cudi himself. But also surfacing are tracks from Wu-Tang Clan and Notorious B.I.G., a reminder of the fact that the genre has from time to time engaged in the topic all along.

Darryl McDaniels of the legendary Run-DMC, for example, showed the inter-generational nature of the struggle when talking about his battles against mental illness with MacLeans earlier this year. He said that resisting help for depression is “a problem with men but even more for black men … In all of our cultures, there’s stupid things that us men do because we think it’s the masculine man thing to do, not realizing we are destroying our very universe.” The frankness of people like himself and Kid Cudi may eventually help to change that pattern.

Why India and Pakistan Won't Face Off at the Kabaddi World Cup

NEWS BRIEF India and Pakistan’s latest diplomatic tension has spilled over into sports after it was announced Wednesday Pakistan would be barred from competing in the Kabaddi World Cup, set to begin Friday in Ahmedabad, India, the BBC reports.

The International Kabaddi Federation, the sport’s governing body, cited heightened tensions between India and Pakistan as the reason behind the decision.

“Pakistan is a valuable member of the IKF, but looking at the current scenario, and in the best interest of both the nations, we decided that Pakistan must be refrained from the championship,” Deoraj Chaturvedi, the IKF chief, told Agence France-Presse.

Pakistan Kabaddi Federation officials called the IKF’s ruling to single out Pakistan unfair, likening a kabaddi world cup without Pakistan to “a football world cup without Brazil.”

Kabaddi is a full-contact sport originating in India, which has won every world cup since the tournament began in 2010. Pakistan was the runner-up in 2010 and 2012, and Nasir Ali, the Pakistani team captain, told AFP the team had high hopes to clinch the winning title after defeating India last month at the Asian Beach Games in Vietnam.

Relations between India and Pakistan—both of which have nuclear weapons—deteriorated in recent weeks following a deadly attack on an army base in Indian-administered Kashmir—one which India has blamed on Pakistan, though Islamabad has rejected the claim. India said it retaliated with a series of “surgical strikes” on Pakistan-controlled Kashmir—attacks which Pakistan denies took place, though it acknowledged two of its soldiers were killed in cross-border fire.

This heightened tension is the latest salvo in fraught relations that span nearly seven decades. Kashmir has been a source of dispute between the two countries, both of which have claimed the contested region in its entirety since the two achieved independence from Britain in 1947. Three wars have been fought over the territory, which is controlled partially by India, Pakistan, and China.

I Drank Coffee Like a Gilmore Girl

“I should’ve brought coffee to wait for this coffee,” my neighbor lamented.

And: Same. It was early—and I mean eeearly—on Wednesday morning, and I was one member of an extremely long line of people who were all waiting for 1) free caffeine, and 2) what we were told would be an IRL experience of the late, lamented Gilmore Girls. Netflix, to promote the new season of the show that will air in November, set up pop-up versions of Gilmore Girls’s iconic diner, Luke’s—the setting where so much of the show’s action (which is to say, rapid-fire dialogue between the girls in question, Lorelai and Rory Gilmore) took place.

The pop-ups popped up, on Wednesday, at locations around the country (some 200 in all). And I—we—were at one of Washington, D.C.’s three versions of Luke’s: the one set up at Flying Fish Coffee and Tea in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood.

A sign from Netflix announced that participants, by participating, relinquished their “Personal Rights.”

And: Wow, there were so many wes! The line to get coffee at Flying Fish-slash-Luke’s stretched down the block, getting ever longer, full of people (most of them in their late 20s and early 30s, most of them women) simultaneously excited and, as the pre-work minutes ticked by, annoyed at how long they were waiting for their whimsy. (One couple behind me, indignant about both the wait and the briskness of the early-fall morning—and extra-annoyed, apparently, that both were endured under hangry and un-caffeinated circumstances—got frustrated by the whole thing, and left.)

For the most part, though, the mood was “low-grade delight.” Luke’s, IRL! One pair of girls marveled at their willingness to be part of such an spectacle at such an early hour; as one of them remarked, though, “nostalgia is a powerful thing.”

The Stars Hollowed cafe “takeover” didn’t, to be clear, offer a fully immersive Luke’s experience; there were no charmingly mismatched tables and chairs, no quirky townsfolk, no proprietor yelling at people to turn off their cell phones. There was, though, a lot of what I’ve come to think of as “selfie infrastructure”: stations designed, basically, to give fans opportunities to take pictures. The features varied by location; the Luke’s I visited, though, went roughly like this:

Station 1: A selfie-optimized Luke’s sign, hanging just outside the cafe’s entrance.

Megan Garber

Station 2: A sign from Netflix announcing that, in exchange for the free coffee, participants relinquish their rights to their own “name, image, likeness, voice, and/or statements”—which is to say, to their own “Personal Rights.”

Megan Garber

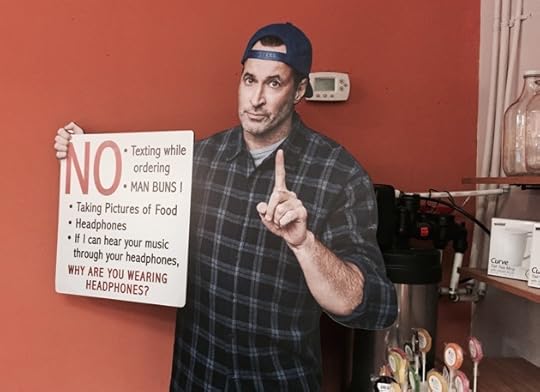

Station 3: An enormous cardboard cut-out of Luke, featuring a 2016-updated list of all the things the ornery-but-lovable diner owner would not allow in his establishment. (The cut-out—set up in a corner, away from the snacking line—was also selfie-optimized.)

Megan Garber

Station 4: The sign at the cash register instructing visitors to “take a picture of you and your Luke’s cup, and tag whom [ed: whom!] you’ll be watching Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life with on November 25, exclusively on Netflix.” (This was not selfie-optimized.)

Megan Garber

Station 5: The behind-the-bar situation, which featured baristas wearing Luke’s caps and t-shirts (but who were, alas, neither flannel-clad nor ornery).

Megan Garber

Station 6: The cup—complete with a commemorative Luke’s sleeve and, underneath, a printed quote from Lorelai about her love of coffee, and a snapcode—that is your free gift, along with the brewed coffee, for attending/line-waiting/Personal Rights-abandoning. (The cup is also, conveniently, perfect for Instagramming.)

Megan Garber

Station 7: The “NO CELL PHONES” sign, maybe the most ready icon of Luke’s Diner, hanging in this case above the milk-and-sugar bar.

Megan Garber

“No cell phones”! In 2016! It’s a nice irony. But it was also, in its way, appropriate. As marketing, the “Luke’s takeover” was only part of the point; the real point was the fans who waited in line at 7 a.m. for coffee that came with an extra shot of nostalgia. People got caffeinated, sure, but they also took selfies and chatted and took some more selfies and spent an hour or two in an ad-hoc amusement park that was amusing only partly because of its physical architecture.

Netflix’s marketing strategy, in all this, may have been bursting with all the buzzwords of the current moment, from the “pop-up” to the “fan service” to the general assumption that attendees would snap and Insta and tweet and otherwise find ways to transform their “experience” into media, thus spreading the word—and, yes, the buzz—about the show’s return. But the “experience,” in that sense, was in the end less about Luke’s, and less about Netflix, and more about fandom: It was a celebration of the fact that people cared enough about Lorelai and Rory and their hyper-literate lives to get up early on a Wednesday to do that caring with other people.

Related Story

Netflix Is Reportedly Bringing Back Gilmore Girls

Audiences are no longer merely audiences, to the extent they ever were; more and more, viewers are part of a show. They influence creators. They bring beloved series back from the brink. They show up. They take selfies. They share them. They tag a friend. And: They love nothing more than being audiences, together. They form, across the expansive and invisible geography of the Internet, their own communities.

As we waited to have that experience, a man on a bike pedaled up to us. “What’s the line for?” he asked.

“It’s a pop-up—a coffee shop,” one of the women next to me replied, struggling to find the words that would put the line-waiting in context for someone who might not be a Gilmore Girls fan. “From … a TV show.”

“Oh, like they’re filming in there?”

“No, it’s a promotion thing,” she replied. She and her friend exchanged a glance. This was really hard to explain. And then the woman settled on the thing that would make the most sense to someone unacquainted with Stars Hollow and its residents and their favorite local diner: “There’s free coffee.”

The Knife Attack on Brussels Police

NEWS BRIEF A knife-wielding man attacked two police officers in Brussels Wednesday in an assault authorities are investigating as terrorism.

The attack occurred in the Belgian city’s Schaerbeek neighborhood, Reuters reported, citing public broadcaster VRT. One officer was stabbed in the neck and the other in the stomach. The assailant fled, but was stopped by other police officers. The assailant broke the nose of a third police officer, who then shot him in the leg.

None of the officers sustained life-threatening injuries. The attacker was a 43-year-old Belgian man, according to The Guardian. He was taken to the hospital for treatment.

Belgian officials said the assault will be investigated by the country’s counterterrorism investigators, but did say why the attack is believed to be connected to terrorism.

In August, a man attacked two police officers with a machete in the city of Charleroi, located about 50 kilometers, or 30 miles, south of Brussels. A nearby officer shot and killed the attacker. The wounded officers were treated for non-life-threatening injuries.

Brussels has been on high alert since bombings in March killed 32 people and wounded more than 300 at the city’s airport and a metro station. The country’s terror alert is at its second-highest, which means the threat of an attack remains high.

October 4, 2016

Elena Ferrante and the Cost of Being an Author

Here are some of the ways the Italian novelist who published under the name Elena Ferrante has explained her desire to remain anonymous:

The wish to remove oneself from all forms of social pressure or obligation. Not to feel tied down to what could become one’s public image. To concentrate exclusively and with complete freedom on writing and its strategies.” –The Guardian

I’m still very interested in testifying against the self-promotion obsessively imposed by the media. This demand for self-promotion diminishes the actual work of art, whatever that art may be, and it has become universal ... The individual person is, of course, necessary, but I’m not talking about the individual—I’m talking about a manufactured image. –The Paris Review

I simply decided, once and for all, over 20 years ago, to liberate myself from the anxiety of notoriety and the urge to be a part of that circle of successful people, those who believe they have won who-knows-what. This was an important step for me. Today I feel, thanks to this decision, that I have gained a space of my own, a space that is free, where I feel active and present. To relinquish it would be very painful. –Vanity Fair

Relinquish it, now, she has: Not by her own volition, but because an investigative reporter tracked down Ferrante’s non-fictional identity, thus solving “one of modern literature’s most enduring mysteries.”

There are many, many questions you could ask about the author’s unwanted unmasking. Was it journalistically responsible—of the New York Review of Books, which published the exposé, and of the reporter Claudio Gatti, who wrote it—to reveal Ferrante’s true (legal, personal, nominal) identity? Is there sexism at play in the way the author’s expressed wishes were regarded—which is also to say, ignored? Is it relevant that New York magazine has, for decades, protected several biographical details about Thomas Pynchon? Is it relevant that the IRL Ferrante is the daughter of a Holocaust refugee?

“Leave Elena Ferrante Alone,” The New Republic demanded. It’s worth wondering why we couldn’t.

And also: Why do we care, actually, who Ferrante is? Will knowing Ferrante’s true identity, now, change the way readers think about her books? Should it?

There’s another question here, though, one that has less to do with Ferrante herself and more to do with the literary environment within which she—and we—currently operate: Do we, as a culture, ask too much of our authors? Do we assume too much our-ness in the “our authors” premise to begin with? How much, really, does Ferrante owe us—and we to her? “Leave Elena Ferrante Alone,” The New Republic, writing on the ethics of the unmasking, demanded. It’s worth wondering why we couldn’t.

* * *

In 1962, Harper Lee, the young and suddenly famous author of To Kill a Mockingbird, gave a press conference to promote the film version of her novel. One of its exchanges went like this:

“Will success spoil Harper Lee?” a reporter asked.

“She’s too old,” Lee replied.

“How do you feel about your second novel?” another asked.

“I’m scared,” Lee replied.

Lee would have, it would turn out, reason to be leery of the lurching machinations of the author-industrial complex. The press would, decade after decade, patiently hound her about that second novel, and about her life in general. (In 2006, The New York Times published a piece that listed the “three most frequently asked questions” associated with Lee’s name: “Is she dead? Is she gay? What ever happened to Book No. 2?”) Her repeated response to the interview requests of Charles Shields, who wrote a biography about her in 2006, was “not just no, but hell no.” As the Times summed it up, euphemistically: “Unmanageable success made her determined to vanish.” And vanish she did. Lee, with occasional exceptions, would join Salinger and Coetzee and Pynchon and, you could argue, Ferrante in casting herself as a castaway.

Lee, tellingly, attributed her reticence directly to her desire to avoid the publicity that’s an unavoidable element of finding oneself a famous author. “I wouldn’t go through the pressure and publicity I went through with To Kill A Mockingbird,” she told a friend, “for any amount of money.”

That would change, of course, when, at the very end of her life, Lee’s lawyer and her publisher announced last year that the long-awaited sequel to Mockingbird would be forthcoming. It remains uncomfortably unclear whether Lee, who at that point had suffered a stroke that left her “95 percent blind, profoundly deaf,” according to a friend, and with a poor short-term memory, actually approved the book’s publication.

What remains uncomfortably clear, though, is the extent to which, in the public reception of Go Set a Watchman, Lee’s desires didn’t much matter. Harper Lee was a person, yes, but she was also, dissolved into the decades, a brand and a political declaration and a beloved childhood memory and a name Brooklynites were fond of appending to their newborns. She was a human, that is to say, who was also an author. The “author” status, in the end, won out. Harper Lee had been claimed by the people.

Even before her unmasking, Ferrante fell victim to a ritual of contemporary literary life: Person and persona, unified and muddled.

There are similar dynamics at play in the literary afterlife of David Foster Wallace. (Christian Lorentzen: “Nobody owns David Foster Wallace anymore. In the seven years since his suicide, he’s slipped out of the hands of those who knew him, and those who read him in his lifetime, and into the cultural maelstrom, which has flattened him. He has become a character, an icon, and in some circles a saint.”) And there were similar human/author tensions at play even while he was alive. After Infinite Jest was published to frenzied acclaim, Wallace began changing his phone number every few months, to prevent unsolicited calls from fawning fans. He began making restaurant reservations under fanciful pseudonyms. When a friend wrote to congratulate him on the book’s success, he replied, “WAY MORE FUSS ABOUT THIS BOOK THAN I’D ANTICIPATED. ABOUT 26% OF FUSS IS WELCOME.”

So, too, Pynchon. So, too, Didion. And so, too, Ferrante—who was, even in her erstwhile anonymity, the subject of Vogue profiles, and Times roundtables, and countless interviews. Who was, as New York magazine put it a couple of years ago, “a new breed of literary girl-crush.” Who was there as a constant reminder of the fine line, in the age of social media and the performative self, between fact and fiction, between author and person. Even before her unmasking, Ferrante had been consumed according to the rituals of contemporary literary life: Person and persona, both unified and muddled. As New York’s Kat Stoeffel put it,

My Elena Ferrante books have been inhaled, dog-eared, loaned out, and warped by water. Now I want to know how Ferrante’s house is decorated. What does she wear when she writes? Who looked after her children? Does she drink? Does she smoke?

We may now find out. Because we ask so much of our authors—to make things, yes, but also to be things for us—and the “we” is generally more powerful than the “they.” Many writers, pragmatically, are introverts. Many of them would prefer, if they had their way about it, not to go on TV, or the radio, or your cousin’s podcast. Many would don’t feel the need to write Franzenian op-eds in the Times. Many don’t want to go on Oprah, or to be on Twitter. Many would prefer to focus instead on doing the thing that is so very hard to do well, and that few can do as satisfyingly as a writer named—still named—Elena Ferrante.

Ferrante, pre-masking, offered another explanation of her desire to stay anonymous: The author, she declared, is an illusion. “I believe that books,” she said, “once they are written, have no need of their authors.” Ferrante was being Barthes-y, sure, with her cheeky eulogy for the author. But she was also being realistic. She was recognizing how separate the writer, in the current, commercialized moment, has become from the writer’s product. She was also, perhaps, foreshadowing her own authorial demise. The prevailing ethic of the current cultural moment gives moral and political primacy to the individual—to one’s experience and perspective and desires. Choice feminism. Identity politics. Empathy above all. “Identity,” as the current discussion well understands, is both a given and an illusion, a declaration and an aspiration, a fact and a fiction. Ferrante’s own identity was, this week—the paradox is revealing—simultaneously shared and destroyed. What now?

Reports of Cinema’s Death Are Highly Exaggerated

The next time you enter a multiplex, or your local arthouse theater, be sure to pause for a moment of quiet contemplation, or perhaps leave a bouquet of flowers at the concession stand. Because, if you haven’t heard, movies are dead, or dying—or, at the very least, they’re looking very sickly, from the way people have been talking about them recently. “Someday we may look back on 2016 as the year the movies died,” the Boston Globe proclaimed last month. “Not To Be Melodramatic, but Movies as We Know Them Are Dead,” The Huffington Post blared melodramatically in June. “They don’t make movies like they used to,” bemoaned the Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump at a rally in Pennsylvania last week.

Yes, one of these is not like the others. But doom-laden warnings about the impending decline of Hollywood, or the expiration of the cinematic art form itself, aren’t new, though the cause often varies. Mark Harris blamed risk-averse movie studios in a 2011 GQ essay. Andrew O’Hehir blamed the rise of television in a 2012 piece for Salon. The same year, David Denby accused Hollywood of murder in The New Republic. The evidence is often anecdotal, which is why it resonates with readers: Ticket costs are higher than ever, the range of television options are vast, and the glut of sequels that crowds the summer-movie market has only grown every year. But with all that said, and even with an objectively horrible blockbuster season in the rearview mirror, I can still happily assert that film isn’t dead, or dying, but changing—and, in many ways, for the better.

The argument for cinema’s death usually revolves around some mix of the arrival of prestige television and an over-reliance on sequels and franchise films, so it’s no surprise alarms were sounded again in the summer of 2016. Airless efforts like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows, Alice Through the Looking Glass, Independence Day: Resurgence, Now You See Me 2, and The Huntsman: Winter’s War bombed with audiences, failing to coast on their name recognition as studios had hoped. Even hits like X-Men: Apocalypse, Suicide Squad, and Jason Bourne were critically derided, and Disney was the only studio that had a truly positive summer, thanks to its animated films (Finding Dory, Zootopia), a remake (The Jungle Book), and Marvel (Captain America: Civil War). Hardly a future to get excited for.

Hollywood’s latest bout of sequelitis is part of a reaction to franchise successes like Marvel, but critics should hold off pronouncing it a new world order for an industry that’s still inherently reactive. This summer, studios have taken note of original, smaller-budget hits like Don’t Breathe, Sausage Party, Bad Moms, and Hell or High Water (all of which cost between $10 and $20 million to make), and mid-budget successes like Central Intelligence, Sully, and Pete’s Dragon, most of which were fueled by good reviews and strong word of mouth. There’s profit to be made in more tightly budgeted features, as Paramount was recently reminded when it reported a $115 million earnings loss because of Monster Trucks, a film that hasn’t even come out yet but is already predicted to be an overpriced flop.

As studios have floundered in their efforts to make Disney-sized franchise smashes, smaller organizations are rushing to fill the gap left in the market. STX, a new “mid-major” studio, had its first $100 million grosser with Bad Moms this summer, after nurturing the surprise critical success The Gift to a healthy $58 million box-office take last year. The indie studio A24 aggressively pushed its horror hit The Witch into a wide release, rather than employing the traditional independent strategy of opening in major cities then relying on word of mouth to expand around the country—and it worked. The supposed film-killer Amazon, partnered with the distributor Roadside Attractions, has had increasing success building critically acclaimed works like Love & Friendship or Hello My Name Is Doris into theatrical hits before rolling them out on its home-streaming platform.

The argument that Hollywood focuses more on sequels to appease an international market and stockholders may not hold true forever. The Chinese market, which has become a supposed box-office boon for Hollywood in recent years, is seemingly souring on America’s offerings as the country’s own film industry becomes more robust; nothing in 2016 has come close to the takes of previous international hits like Furious 7 or Transformers: Age of Extinction. A studio’s performance on Wall Street has more to do with profits than anything else. So given that franchise films like Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice are dismissed as financial misfires because they fail to gross an obscene $1 billion worldwide, and expensive endeavors like Monster Trucks hurt profit margins even before their release, executives will have to get smarter about how they use their resources. If studios continue to gamble on giant-budget releases, they could very well spend their way into extinction.

The “death of movies” debate, more than anything, is about awareness.

But the film industry has steered its way out of catastrophe many times before now. In 2012, after a wave of essays predicting that prestige TV’s popularity meant the end of movies, Indiewire’s Oliver Lyttelton compiled a useful list of funeral notices for cinema throughout history. The Romanian director Isidore Isou said the art form had “reached its maximum” in the 1940s. The then-critic (and future director) Francois Truffaut was called the “gravedigger of French cinema” in 1957 for his dire portents; he later marked October 1962, and the release of the James Bond film Dr. No, as the specific time of death for film. Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls blamed the release of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, seen as the first modern blockbuster. The director Peter Greenaway said in 2002 that nobody he knew went to the theater anymore. Indie movies specifically died in 2008, according to Peter Bart of Variety.

In fact, the options for seeing a smaller film are easier than ever, thanks to the rise of video on demand. Rather than wait for an indie hit to open locally, audiences can often view it on the same day of release, if not soon after, in their home theaters (and/or laptops). A great, micro-budgeted art film like The Fits, hailed by critics but never released in more than 20 theaters, can be seen by everyone as long as the hype is loud enough—and it can be made for a tenth of the cost of an indie work in the 1990s thanks to the rise of digital cameras and editing software.

The “death of movies” debate, more than anything, is about awareness. A film like The Fits is not going to get the promotional push of a new show on Netflix, even though it might appeal to an equally wide audience. Cinema remains siloed into “studio” and “indie” efforts, with a good chunk of audiences largely ignoring the latter, while television (which essentially has to be made within a studio system) can offer the kind of adult dramas and politically aware works that are seemingly missing from multiplexes. But these aren’t the signs of a lifeless industry. Film is just doing what it’s always done—finding a way to adapt, survive, and serve new audiences.

Danny Brown and the Freedom to Be Depressed

In February 2014, Danny Brown was four months out from having released his most commercially successful work, Old, and he wasn’t feeling good. “I can't sleep my anxiety is at an all time high but don't none of y'all care about that shit .. Y'all just want me to be goofy,” he tweeted. “Depression is serious y'all think I do drugs cause it's fun. [...] Nobody cares if I live or die .. That's the bottom line .. Y'all want me to overdose just don't be surprised when u get what u asked for.”

It was a dark message, one that may indeed have surprised casual fans who thought of Brown as just “goofy” because he raps in a crazed squawk and his most famous lyrics are vivid comparisons between sex and food (once you’re familiar with Brown’s discography, Cool Ranch Doritos are no longer an acceptable snack option). But to anyone who’d actually sat with his albums, the talk of drugged-out sadness verging on suicidal would have seemed on brand for the deliriously talented Detroit rapper with a serious experimental streak. The second track from his breakout 2011 album XXX announced his intentions to, per its title, “Die Like a Rockstar.” Its lyrics ran through a list of celebrities who went early, Kurt Cobain to Heath Ledger to Britney Murphy.

“Die Like a Rockstar” also, though, did exactly the thing that Brown’s Twitter spree took aim at: treat self-destructive behavior as entertaining, sexing up tragedy. Brown’s music, like so much music and art about drugs and depression, has often staggered along the line between cautionary confession and exciting spectacle—or highlighted how there really might not be a line between those two things at all. “What people don’t understand is a lot of those songs are about depression,” he told Stereogum. “‘Smokin & Drinkin’ to forget about it, just partying to get away from all your problems,” he added, referring to the name of one of his hits.

His new album, Atrocity Exhibition, works to make clearer that Brown’s problems aren’t fun. It takes its title from a song by Joy Division on which Ian Curtis, who killed himself before its release, sung about insane asylums where voyeurs paid to watch the patients. And the opener’s title, “Downward Spiral,” calls back to the 1994 masterpiece album of the same name by Nine Inch Nails, one of the all-time-great bands for making deep emotional trauma into a fun scream-along time via pop hooks and disco beats. Brown’s not doing that. The dazzling and difficult Atrocity Exhibition pushes Brown’s sound in more extreme, musically innovative directions to mimic the extremity that’s been in his words all along.

The album opens with what sounds like a band in warm-up, a drummer messing around but finding no groove, a guitar pealing out scattered notes but no riff—a beat that will by the end of the record seem typical, courtesy of producer Paul White. Brown narrates an awful drug comedown, and when it begins to seem like he’s getting back to bragging about sex he takes the story to a place that male pop artists simply don't ever go: “Had a threesome last night, ain’t matter what it cost / Couldn’t it get hard, tried to stuff it in soft.” Later in the song, he recounts feeling numb to everybody telling him he has a lot to be proud of; in interviews, he’s located the album’s storyline as depicting the period after XXX gained him wide recognition.

From there, Atrocity Exhibition has the feeling of a montage, flashing back and forward in time, telescoping in or broadening out, often in search of the source of Brown’s woes. For its second track, “Tell Me What I Don’t Know,” he beams back to his days as school-age drug dealer, a period when he was “naive to the outcome” and landed behind bars. A morose synth line reminiscent of a ’90s computer-game death sequence loops as Brown raps not in his trademark yelp but in an even, low speaking voice: “Shit is like a cycle / You get out, I go in, this is not the life for us.” It’s the sound of existential doubt and fear being planted at an early age.

Elsewhere, rap success itself comes off as the inner villain on woozy tracks like “Rolling Stone,” which revives the unhappy rock-star comparisons, and “Lost,” a portrait of shut-in hedonism. He perks up, wild-eyed, for the extraordinary “Aint It Funny,” powered by blasts of noise that distill the disaffection of peak Iggy Pop as Brown boasts about his lyrical agility—“Verbal couture / Parkour / With the metaphors”—and his drugs (“The rocks bout the size / As the teeth in Chris Rock's mouth”). There’s the bizarrely infectious “White Lines,” where a keyboard line tracks Brown’s up-and-down vocal melody for a creepy funhouse vibe. He’s partying on tour, hoping that the latest line of coke isn’t the one that kills him.

Then there are moments where Brown considers that his depression and addictions aren’t rooted in any specific cause other than his own biology—or maybe his upbringing. It’s a concept that he’s talked about before, and on “Ain’t It Funny” it comes up again with Brown rapping about “a living nightmare / That most of us might share / Inherited in our blood /It's why we stuck in the mud.” The fatalism of those words is profound, but he at least gives a hint of determination to overcome in the closing track where piano keys tinkle anxiously but Brown affirms himself, “I'm a give em hell for it / Until it's heaven on earth.”

It’s not happier music, but more committed, more extraordinary unhappy music.

The album’s not entirely without jams to jump around to, though anyone paying attention gets that even their subtext is not super happy. “Dance In the Water” is an explosive, clattering reverie probably meant to mimic a frantic high, and “Pneumonia” has a great hook where Brown compares his flow to the illness of the title—one more physical malady on an album full of them. Then there’s the confidently swaying anthem “Really Doe,” featuring Kendrick Lamar, Earl Sweatshirt, and Ab-Soul, all rappers who, like Brown, have highlighted hip-hop’s potential to embrace darker, emotionally precise lyrics in the last few years.

In fact, the extremity of Atrocity Exhibition could be a sign of the times for the genre. In the past, Brown’s work and public statements have been included in think pieces about rap’s—and portions of black America’s—fraught relationship with depression. Previous generations of emcees may have sometimes confessed to trying times, but lately there’s been a flowering of major artists who put their emotional struggles at the center of their work, from Drake’s chart-topping grimaces to Lamar’s scalding self-examinations to Vince Staples’s extraordinary and fearless recent EP Prima Donna.

All of which, perhaps, is a liberating thing for Danny Brown, someone who’s been outré all along both in sound and in subject matter. In his 2014 Twitter confession about depression, Brown wrote that part of his problem was that he felt disrespected by his industry: “all the rappers i look up to this i suck or think I'm a wierdo or some shit.” He singled out Nas as someone he wished would pay him some attention but hadn’t. But the world has begun to catch up, and while creating Atrocity Exhibition, Nas reportedly sat Brown down and gave him a pep talk. The results weren’t happier music, but more committed, ever-more-extraordinary unhappy music.

Erdogan Jokes Aren't Verboten in Germany

NEWS BRIEF German prosecutors halted Tuesday their investigation into a German satirist who faced legal repercussions for reciting a televised poem insulting Recep Tayyip Edogan, the Turkish president, Deutsche Welle, the state-run German broadcaster, reports.

The prosecutors cited insufficient evidence that Jan Böhmermann, the TV comic, committed a crime when he performed a satirical poem in March criticizing Erdogan’s policies as well as making lewd sexual references toward the Turkish president. Erdogan was not amused by the poem, and Ankara demanded the clip be removed. Böhmermann and Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF), the German public broadcaster which aired the poem, refused.

The diplomatic spat between Berlin and Ankara prompted Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, to give prosecutors the green light in April to launch a criminal inquiry into whether Böhmermann’s actions were legal—a move she said “means neither a prejudgment of the person affected nor a decision about the limits of freedom of art, the press, and opinion.”

Now, prosecutors are saying they’ve found no evidence of criminal behavior to support filing charges.

Böhmermann wasn’t just facing prosecution for hurting a world leader’s feelings. Rather, the prosecutors’ investigation sought to determine if the comic had broken German law. Under paragraph 103 of Germany’s penal code, it is unlawful to slander representatives of foreign states. It reads:

Whosoever insults a foreign head of state, or, with respect to his position, a member of a foreign government who is in Germany in his official capacity, or a head of a foreign diplomatic mission who is accredited in the Federal territory shall be liable to imprisonment not exceeding three years or a fine, in case of a slanderous insult to imprisonment from three months to five years.

Böhmermann defended himself by calling the poem an “exaggerated portrayal” of the Turkish leader that could be easily recognized as “a joke.” Joke or not, the incident has prompted Germany to re-examine its defamation laws, with some calling for the prescription against insulting foreign leaders to be abolished altogether.

Though criticism of Erdogan may not exactly be verboten in Germany, that’s certainly not the case in Turkey, where authorities have arrested more than 32,000 people with suspected links to Fethullah Gulen, the U.S.-based cleric who Turkey says orchestrated the coup attempt in July.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower