Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 61

October 7, 2016

The Russian Hack of the DNC

NEWS BRIEF U.S. intelligence officials accused Russia Friday of orchestrating the July hack of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, reaffirming speculation that Moscow played a role in the breach that resulted in the release of thousands of DNC staff emails.

In a joint statement by the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the U.S. government said it is “confident” the Russian government played a role in the hack aimed at interfering with the ongoing presidential election. Here’s more from the statement:

The recent disclosures of alleged hacked e-mails on sites like DCLeaks.com and WikiLeaks and by the Guccifer 2.0 online persona are consistent with the methods and motivations of Russian-directed efforts. These thefts and disclosures are intended to interfere with the US election process. Such activity is not new to Moscow—the Russians have used similar tactics and techniques across Europe and Eurasia, for example, to influence public opinion there. We believe, based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia's senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.

But the statement added that the U.S. intelligence committee and DHS “assess that it would be extremely difficult for someone, including a nation-state actor, to alter actual ballot counts or election results by cyber attack or intrusion.”

U.S. officials have long said Moscow was behind the breach that resulted in a leak of nearly 20,000 DNC emails—obtained by a hacker known as “Guccifer 2.0” and published by Wikileaks—which revealed DNC staffers favored Hillary Clinton over then-rival Bernie Sanders for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination; the leaks led to the resignation of Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the committee’s chair.

Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, denied his government’s involvement with the breach. When asked about the breach last month, he told Bloomberg: “I don’t know anything about it, and on a state level Russia has never done this.” He added: “Listen, does it even matter who hacked this data? The important thing is the content that was given to the public.’’

The issue made its way to the first presidential debate between Clinton and her Republican rival, Donald Trump. Trump, who has praised the Russian leadership and whose now-former top aide had close ties to Russia, said it wasn’t clear Moscow was behind the hack.

“She’s saying Russia, Russia, Russia,” he said during the debate. “I don't—maybe it was. I mean, it could be Russia, but it could also be China, it could also be lots of other people. It also could be somebody sitting on their bed who weighs 400 pounds, OK?”

Green Day Finds Comfort in Protest

One of the last times Green Day had a real hit, it consisted of Billie Joe Armstrong asking, over and over again, “Do you know your enemy?” His band rumbled behind him, creating a kind of back-and-forth sawing sensation, as he repeated the question but only ever answered it vaguely.

As is the case with a lot of music that styles itself as “punk” (even or especially pop punk), there is always an enemy in Green Day’s songs. In the early days, the villain was small-scale suburban conformity; in the band’s grandiose 2000s, it was also the state of the world more broadly. The group’s solidly enjoyable new album Revolution Radio positions itself as continuing on the protest march announced by 2004’s American Idiot, but listening to its songs’ mentions of gun violence, drones, and the Flint water crisis, you might get the counterintuitive sense that “the enemy” here is not actually any larger evil—it’s age.

Green Day are 30 years into their career, and their entry into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2015—their first year of eligibility—was a recognition of the group’s enormous influence. The fact that their near-contemporaries Blink-182 had a No. 1 album this year speaks to the fan base that remains for pop-punk veterans. But Revolution Radio is also the band’s first album since Armstrong’s well-publicized 2012 onstage meltdown and trip to rehab for addiction, and also its first release since the poorly received album trilogy ¡Uno!, ¡Dos!, and ¡Tré!. All of which explains why Revolutionary Radio sounds like a safe regrounding. It’s a 12-song blast of comforting melody and guitar crunch that uses protest rhetoric almost like someone saying their daily affirmations—rebellion as soothing routine.

“I never wanted to compromise or bargain with my soul / How did a life on the wild side ever get so dull?” Armstrong asks over glimmering guitars on the spacious, wide-eyed opener “Somewhere New.” The rest of the song hints that we’re meant to think he’s talking about a national kind of malaise—“I put the ‘riot’ in ‘Patriot,” “All we want is money and guns / A new catastrophe”—but throughout the album, political bummed-outedness and personal bummed-outedness blur together. The hard-driving single “Bang Bang” puts itself in the mind of mass shooters, whose primary motivations, Armstrong argues, are boredom and attention-seeking, the same things that these songs suggest power some of his own vices. And the careening title track, inspired by Black Lives Matter demonstrations, focuses more on the thrill of banding together for a purpose than it does focus on any particular purpose itself.

Then there are moments clearly meant to illustrate Armstrong’s own life, or at least the life of the washed-up punk singer he plays in the forthcoming indie film Ordinary World. The Fountains of Waynes-y bop “Youngblood” is about how Armstrong’s wife keeps him feeling youthful; “Still Breathing” is a first-raising ballad about resilience; the lovely acoustic closer “Ordinary World” makes peace with banal reality. Most transparent in its message is “Outlaws,” which channels a touch of “Earth Angel” and Weezer as Armstrong pines for his band’s younger days, when they were, per the title, “outlaws.” It’s the cry of a rebel who’s always been in search of a cause.

The music is unfailingly melodic and crisp, derived as much from Tom Petty as from The Descendants, and it often shows off Green Day’s underrated ability to make sneering radio rock feel as cozy as a Christmas carol (the opening track even has sleigh bells). A few songs boast cute innovations: the bar-band romp “Bouncing Off the Walls” doesn’t have a singalong chorus but rather a repeating riff and a closing refrain, and the ambitious “Forever Now” switches tempos between its various sections before revisiting and revising a line from the start of the album. “How did a life on the wild side / Ever get so full?” Armstong asks, and the implication is that he’s been saved, once again, through the simple power of music about resistance.

An End to U.S.-Philippine Defense Cooperation?

NEWS BRIEF The Philippines announced Friday plans to cancel future joint military exercises with the United States in the South China Sea—a marked break in defense cooperation between the long-standing allies that follows weeks of rhetoric aimed at the U.S. by the new Filipino president.

“This year would be the last,” Rodrigo Duterte, the president of the Philippines, said Friday of the countries’ joint military exercises.

Addressing the U.S. directly, he said: “For as long as I am there, do not treat us like a doormat because you’ll be sorry for it. I will not speak with you. I can always go to China.”

In addition to halting military exercises between the two countries, Delfin Lorenzana, the country’s defense minister, said Duterte hopes to dismiss U.S. troops helping monitor and fight Islamist militants in the southern part of the country—a task he said the Philippines would assume once it acquired the necessary intelligence-gathering capabilities.

In response to the possibility of the coordinated drills between the two countries ending, Roger Hollenbeck, a U.S. military spokesman, said, “I have nothing to do with that and we are going to continue to work together, we’ve got a great relationship.”

The future of this “great relationship” remains unclear, however. The Philippine president hasn’t shied away from suggesting that he may pursue closer relations with Russia and China—at the expense of his country’s ties with the U.S. But a closer relationship with China might not be quite as easy as Duterte hopes: Both countries claim the South China Sea. As my colleague J. Weston Phippen pointed out:

More than $5 trillion of trade passes through its waters each year, and while China claims most of the South China Sea,Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines have competing claims and would like a larger share. In July, an international tribunal in The Hague ruled in favor of the Philippines’ claim to a portion of the sea and concluded China has no legal right over the bulk. China refused to acknowledge the ruling.

That could make for an awkward introduction, or an interesting bargaining chip as Duterte seeks a closer relationship with Beijing—assuming Duterte sticks by his words.

Since his election over the summer, Duterte has used testy language to describe criminals, drug users, the U.S., and President Obama. Last month, he called Obama a “son of a bitch” in response to a U.S. inquiry about his government’s extrajudicial killings of more than 2,000 people in an effort to “kill all the drug lords.” Duterte later apologized, only to tell Obama to “go to hell” a month later.

Duterte was also criticized after he likened his ambitions to the Nazis’ mass murder of 6 million Jews, saying, “Now there’s 3 million, there’s 3 million drug addicts. There are. I’d be happy to slaughter them.”

Those comments aren’t restricted to Duterte. As the BBC reports, Teodoro Locsin Jr., the Philippines’ recently appointed ambassador to the United Nations, said in August: “I believe that the Drug Menace is so big it needs a FINAL SOLUTION like the Nazis adopted. That I believe. NO REHAB.” Locsin, who is not a career diplomat, issued an apology Thursday for invoking the Holocaust, though not for view towards the country’s drug war.

How ‘Important’ Is The Birth of a Nation Really?

One of the words most commonly used to describe Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation is “important.” The word seemed less fraught when the movie, which tells the story of the 1831 slave rebellion led by Nat Turner, debuted to notable acclaim at Sundance early this year. But it took on a different feel when college rape allegations against Parker and his co-writer for the film emerged during promotion for the movie. And then again when news broke that the alleged victim killed herself in 2012. “Important,” now, is being deployed to help sway those who remain critical of or conflicted about Parker, The Birth of a Nation’s writer, director, and star.

Amid the strong criticism of Parker that’s ensued, there have been many calls to prioritize the significance of the movie over any personal feelings about the filmmaker. Again and again, cast members, critics, and supporters have suggested both explicitly and implicitly that The Birth of a Nation should be seen because it’s an “important” work. But what exactly makes a film required viewing despite personal ambivalence or objection? What does “important” mean?

The Birth of a Nation is important insofar as any narrative about slavery, race, or other parts of America’s dark past is. Films in this tradition are valuable because they demand a continued reckoning with a history that’s too easy to forget or gloss over, and they also explore how the impact of that past continues into the present. But the fact that The Birth of a Nation is representatively important as a movie doesn’t mean that it’s good cinema, or even a necessary addition to the genre of stories about slavery.

One oft-cited meaningful feature of the film is its historical grounding in one of the bloodiest slave rebellions on record: Nat Turner’s revolt in Virginia, which resulted in the deaths of over 50 white people and the subsequent killing of hundreds of blacks as retribution. The Birth of a Nation doesn’t spare its audience the powerful and disturbing images of beatings, force feedings, and a litany of other atrocities that supposedly motivated Turner’s rebellion. Nor should it. But aside from its status as one of the deadliest, there’s not a widespread consensus among historians that Turner’s uprising had critical, long-lasting consequences for the institution of slavery or the people who benefited from it.

Further, little is actually known about Turner himself aside from a few sparse historical accounts and the confessional he wrote prior to his execution—a document that deserves scrutiny since it was produced by a white attorney during Turner’s confinement and published after Turner’s death. This knowledge vacuum would make it difficult for a filmmaker (or anyone) to fill in the blanks about Turner’s life and motivations without significant editorializing. And Parker does editorialize, choosing to include scenes and tropes that viewers may bristle at: at least two instances of the brutalization and rape of black women and the portrayal of Turner as the constant, morally unambiguous hero.

But even as a narrative about slavery in general, The Birth of a Nation doesn’t break any new ground that would make it essential viewing. Rather, the movie retreads some of the same emotional and visual terrain as Roots, 12 Years a Slave, and Django Unchained—and in some cases it does so less artfully. There are familiar tropes: the at once beautiful and devastating scenery of antebellum plantations with lush foliage being toiled by black bodies bent under the watchful eye of an overseer. The frustrating Uncle Tom house slave and the benevolent white benefactor. The commonness of unspeakable cruelty.

Parker, it seems, is trying to convey the strength, bravery, and agency of slaves in the face of unimaginable atrocities. Turner’s motivation—solidified during his travels as a preacher to his fellow slaves—becomes answering a moral call to stand up for his brethren and himself. A reading of Turner’s own words reflects far more religious fanaticism than moral imperative. Much of the heart and feeling infused into The Birth of a Nation are of Parker’s own design. And even in these instances, intended to humanize an enigmatic historical figure, the film offers heavy-handed moments of gravitas that come off as trite rather than moving.

Despite prominent examples of stories about slavery, the subject—along with the broader issue of race—is still dramatically under-explored and underrepresented in Hollywood, leaving plenty of room for more incisive history-based accounts. In this context, it’s little surprise that The Birth of a Nation received the premature praise and attention it did. Many Hollywood studios, critics, and moviegoers looked at the movie and saw a rare and thus seemingly vital project—one driven by the singular, ambitious artistic vision of black American man. It was hard not to respect the apparent passion behind the film, which was made with much of Parker’s own money and with the help of other black actors and writers.

Ultimately, the movie isn’t sublime nor can it transcend the personal flaws of its creator.

Together, these factors created astronomically high expectations for The Birth of a Nation itself. The promise of a groundbreaking work about slavery and a heroic portrayal of a revolt brought to Hollywood by a rising black filmmaker was enticing. But hopes for the movie and its creator hit a snag as Parker faced scrutiny for his past and criticism for how he handled questions about the rape allegations today. Amid growing disappointment with Parker’s personal life, emphasis on the film’s importance as new addition to the canon of works about black America has only intensified.

Though The Birth of a Nation does little to artistically differentiate itself from its predecessors, it remains a special case of a black person telling a story about black people and, at least at Sundance, receiving applause for it. The Birth of a Nation finds itself in the middle of a national conversation where many who are frustrated with persistent racism and inequality are willing to embrace a tale about the oppressed rising up against their oppressors at any cost. The movie’s reappropriation of the title of one of the most sweeping works of racist propaganda ever created in order to tell the story of a slave uprising is, perhaps, its most clever victory.

But for those who’ve said they hoped to view and enjoy the the film in spite of mixed feelings about Parker and his past, that may prove difficult. The fact remains, The Birth of a Nation is a movie that is solely about Nat Turner, told from Turner’s largely fictional perspective. It is envisioned, written, editorialized, and performed by Nate Parker. Ultimately, the movie isn’t sublime nor can it transcend the personal flaws of its creator—its own failures as a work of cinematic art simply don’t allow it to. Whatever importance The Birth of a Nation does have lies solely in its status as an uncommon film that forces viewers to confront the horrifying and courageous history of black people in America.

What Should the Nobel Peace Prize Recognize?

The Nobel Committee’s decision to award the 2016 Peace Prize to Juan Manuel Santos is a gamble of sorts, a bet on a peace process that is troubled and still incomplete. But that gamble also represents a return to a different sort of award for the committee. After a string of winners notable for their admirable heroism, the committee has chosen to grant an award recognizing a major effort toward resolving a specific conflict.

The committee praised Santos “for his resolute efforts to bring the country’s more than 50-year-long civil war to an end, a war that has cost the lives of at least 220,000 Colombians and displaced close to six million people. The award should also be seen as a tribute to the Colombian people who, despite great hardships and abuses, have not given up hope of a just peace, and to all the parties who have contributed to the peace process.”

Related Story

It also acknowledged that the peace in Colombia is a work in progress: “The fact that a majority of the voters said no to the peace accord does not necessarily mean that the peace process is dead.” In a positive sign, the leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) congratulated Santos as negotiations continued in Cuba.

Many of the most memorable prizes have gone to people working to resolve intractable, decades-long conflicts, and many of them have been controversial gambles. Take the 1973 award to Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho. On the one hand, the end of the Vietnam War, which it recognized, was a monumental moment. On the other hand, the idea of Kissinger being a peace laureate has taken on the air of a ghoulish joke: Between the revelation that his boss, Richard Nixon, prolonged the war for political gain, and the proof of Kissinger’s complicity and indifference to slaughter in Bangladesh and elsewhere, he hardly seems like a hero. While the Oslo Accords seemed like a turning point, earning Yasser Arafat, Shimon Peres, and Yitzhak Rabin the 1994 prize, a lasting peace in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict seems as remote as ever. Yet other prizes have borne the test of time, whether Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat for the Camp David Accords or F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela for the end of Apartheid.

Over the past two decades, however, there have been few such towering prizes. The recent string of winners shows a trend toward recognizing winners who are admirable but have fewer concrete achievements. Too often prizes look like ‘A’s for effort, rather than achievement. No two winners encapsulate this better than 2009 winner Barack Obama and 2014 co-winner Malala Yousafzai. Obama was given the prize scanty months into his presidency, primarily in recognition, it seems, of his not being George W. Bush. Yousafzai became an international hero at age 15 when she was shot by the Pakistani Taliban. Her award acknowledged her status as a powerful activist and voice, but even some supporters were uncomfortable with her win.

“Statement” awards like this are a common theme in recent years: Al Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Mohamed ElBaradei and the International Atomic Energy Agency in 2005, two years into the war in Iraq. Sometimes, the Nobel panelists have opted to choose winners who represent broad ideas. In 2011, Liberians Leymah Gbowee and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf won, but the committee tacked on Yemeni activist Tawakkul Karman, making the award not a recognition of gains in either country but a more nebulous set of work. In other cases, the committee has made somewhat uninspiring choices, recognizing the European Union (2012) or the United Nations (2001). Does anyone remember either of these today?

Arguably not since 1998, when John Hume and David Trimble won the prize for the Northern Irish peace process, has the committee spotlighted leaders who had worked to solve an intractable, violent struggle. It is in years like this that the committee seems to come closest to meeting Alfred Nobel’s original mandate: That the prize go “to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

The 2015 prize was somewhere in the middle. It went to four groups that helped establish a post-Arab Spring government in Tunisia. That country has emerged as the only (if tentative) success story of the wave of revolutions across North Africa and the Middle East, but the award felt somewhere between premature and anti-climactic. Is preventing a hypothetical bloodshed the same as ending one?

Unfortunately, peace processes like the one in Colombia, or in Northern Ireland, or the Camp David Accords are unusual. They are also risky for the Nobel committee, which could see the negotiations in Havana fail, producing an Oslo-like situation. But negotiations like the one in Colombia are much riskier for Santos and his FARC interlocutors, and it is right and fitting that the Nobel Committee should emphasize their work.

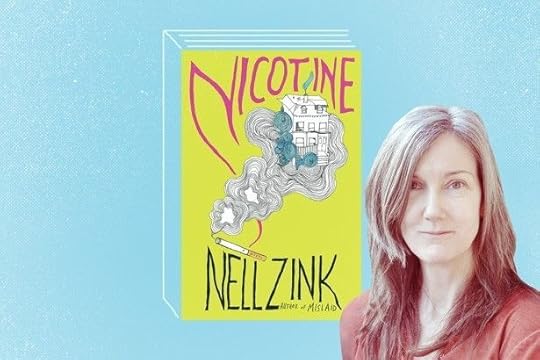

The Key to Nell Zink's Subversive Satire

Many writers who are said to “come out of nowhere” are just young—what makes their fame surprising is their youth. The novelist Nell Zink’s route to success has been genuinely unusual. Until a small publisher released The Wallcreeper in 2014, she was a complete unknown, a bricklayer turned secretary turned translator from Virginia who moved to Bad Belzig and wrote fiction in private. Zink’s closest brush with the literary world had been exchanging letters (about birding) with Jonathan Franzen, who encouraged her to get serious about her writing. In short order, she has developed a reputation as an idiosyncratic talent, had her work long-listed for the National Book Award, and been profiled in national magazines.

Zink, 52, has now published her third novel, Nicotine, which is a disappointment compared with its two wily, almost unclassifiable predecessors. About halfway through, the protagonist says of her mother, “I don’t know what she’s going to get up to next, but it’s sure to be a tragicomedy with much OMG.” And that’s a fine encapsulation of the novel. By turns dark and funny, the drama inspires a careless, off-the-cuff response: OMG, or maybe LOL.

Yet beneath the froth runs the same rich theme that has informed her distinctive satiric perspective from the start: the slippery nature of our public identities and loyalties. Zink takes a special interest in how we present ourselves socially—how we navigate the mutable relation between private reality and appearance, between insider and outsider status. In prose that deploys social theory and delivers one-liners with equal antic verve, Zink makes sure that her role-shifting characters keep her readers off-balance.

The Wallcreeper, a manic monologue that skewers middle-class social mores and sacred cows, turns on the conceit that everything is a sham—and on the notion that nobody is totally convinced. The narrator, Tiff, barely knows her husband. How could she, having married Stephen mere weeks after their first meeting? What’s more, Stephen’s “ruling principle” is “let’s not and say we did.” He believes that “most people don’t give a fuck what you’ve done and not done,” so all that matters is the facade.

Zink creates amusing mayhem by planting doubts about such confident cynicism. Good luck figuring out why Stephen abandons his job as a pharmaceutical researcher to join the environmental movement. Is he passionate about restoring rivers, or is he trying to please his paramour, Birke? For that matter, is Birke pure of heart, or is she drawn to activism because she likes making posters and giving interviews? Whatever the truth, they successfully pass for true believers at conferences. But even, or especially, Stephen isn’t spared a dose of angst about his bona fides.

Zink skips the telling nuances and settles for hurried farce.

Zink captures his predicament in a brilliant bit of marital byplay. To Stephen’s complaint that engineers and ecologists condescend to him, Tiff offers what she thinks is a comforting reality check: “You’re an activist running a media campaign. They know that.” Stephen takes umbrage. “I know I’m a self-styled activist promoting a slogan. You don’t have to remind me.” Grudgingly, Stephen concedes that styling and being, publicizing and doing are not the same.

Zink’s second novel, Mislaid (2015), is more ambitious—a screwball, vaguely Shakespearian comedy of errors in which the protagonist tries on and casts off characteristics we generally consider immutable: sexual orientation and race. As a teenager, Peggy comes to the conclusion that “she was intended to be a man,” by which she means that she’s a lesbian. At college, however, she and a gay male poetry professor fall for each other, to their complete surprise.

Their attraction is sincere, which isn’t to say that Zink presents sexual orientation as wholly situational, much less imaginary. Eventually, the spell wears off. Lee goes back to liking men, and Peggy goes back to liking women. They would probably remember the affair as nothing more than a puzzling interlude if it hadn’t had consequences: a son and a daughter. Of course parenthood doesn’t stop Peggy from challenging the contours of identity even further as the novel barrels on. She and her daughter run away from Lee, and they impersonate “tawny black people” to elude the authorities. Although this is absurd—they have blond hair—it is no more absurd than American racial categories. “Maybe you have to be from the South to get your head around blond black people,” the narrator explains:

Virginia was settled before slavery began, and it was diverse ….The only way to tell white from colored for purposes of segregation was the one-drop rule: if one of your ancestors was black—ever in the history of the world, all the way back to Noah’s son Ham—so were you.

Just when it looks as though Zink is delving into pure fantasy—a world in which appearances don’t matter in the slightest— in fact she is exposing the reality of the one-drop rule, a system that has nothing to do with skin color. Two white people can easily pass for black and, in effect, be black. Indeed, everyone treats them as if they were black, and that is their lived experience: White girls call Peggy’s daughter “nigger” and black girls call her “half-white.”

Nicotine serves up light sexual comedy and broadbrush satire of social activist pretenses.

The third time around, Zink skips the telling nuances and settles for hurried farce. Once again, her characters don different hats, as it were; the difference is that in Nicotine they’re more obviously poseurs, their morphing less self-aware and more frivolous. Penny, the central character, is a flighty 20-something surrounded by flighty 20-somethings, and eager for distance from her hippy family. Zink gives her an exotic backstory—her mother was a 13-year-old member of the Kogi tribe in Columbia when her father, a middle-aged white American, spotted her, adopted her, and then married her. But the focus is on the present, not the past.

Sent to inspect her father’s childhood home, Penny discovers that it’s been turned into a squatters’ co-op, one of several in his old New Jersey neighborhood. Although she’s supposed to move the squatters along, she decides to join them instead after falling for their de facto leader, Rob, who’s alluring in part because he is off-limits (he claims he’s asexual).

Nicotine serves up light sexual comedy and broadbrush satire of social activist pretenses, recalling Zink’s previous work in what almost feels like self-parody. “The requirement to live in [a co-op] is that activism be your main occupation,” Rob explains. “The houses all have themes,” of rather different calibers:

Some [themes] are pretty trivial—bicycle activists like me, tree tenders, you know, small-time BS—and some are big mainstream political issues like environmental stuff, disarmament, different health issues, AIDS and TB and whatever.

Actually, Rob’s house barely has a theme at all; the only unifying factor is that its residents are addicted to nicotine and rail against a society that ostracizes smokers.

Sincere commitment to a cause is hard to find among any of the squatters, who seize opportunities to join the bougie world as soon as they arise. Rob’s claims to being asexual don’t amount to much either. It turns out he’s been numbing his desires with nicotine because he’s ashamed of his penis size. All it takes is a little nudging, and he’s ready to embrace sex. Maintaining an outsider pose, Zink has shown before, is hard—not because against-the-grain allegiances go deep, but because they don’t. Yet on this occasion the astringent insight can’t rescue a narrative that ends up feeling as silly as the characters.

What about Penny’s parents, a couple who evidently violated social norms with their May-December, cross-cultural romance? An odd kind of spoiler is in order: Zink leaves the potentially discomfiting implications of that storyline unexamined. In Penny’s family, a relative suggests, people may be adopting rebellious poses out of more conventional motives than she realizes. Since we never find out for sure— Zink opts for loose ends— Nicotine feels unfinished. Lore has it that she writes astonishingly quickly, drafting her novels in less than a month, so here’s hoping Zink was simply in a rush to turn to something truly different.

The Nobel Prize for Peace

Updated at 7:44 a.m. ET

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has been awarded this year’s Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts—rejected by voters last week—to end the country’s decades-long civil war with FARC rebels.

The Nobel Committee said Santos was being given the award “for his resolute efforts to bring the country’s more than 50-year-long civil war to an end.” But the committee acknowledged that Colombian voters had narrowly rejected the deal in a nationwide referendum last weekend—one that stunned the world given that Santos and the FARC leader known as Timochenko had signed the deal on September 26 with much fanfare, flanked by officials from around the world, as well as members of the rebel group. Here’s more:

The fact that a majority of the voters said no to the peace accord does not necessarily mean that the peace process is dead. The referendum was not a vote for or against peace. What the “No” side rejected was not the desire for peace, but a specific peace agreement. The Norwegian Nobel Committee emphasizes the importance of the fact that President Santos is now inviting all parties to participate in a broad-based national dialogue aimed at advancing the peace process. Even those who opposed the peace accord have welcomed such a dialogue. The Nobel Committee hopes that all parties will take their share of responsibility and participate constructively in the upcoming peace talks.

Indeed, the Nobel committee said the “award should also be seen as a tribute to the Colombian people who ... have not given up hope of a just peace.”

Santos, in an audio interview posted on the Nobel Prize’s Facebook page, said he accepted the award on behalf of “the Colombian people who have suffered so much in this war.”

As my colleague J. Weston Phippen has reported, the details of the deal had angered many Colombians who said it was too lenient toward FARC rebels. The regions where the “no” vote won by the largest margins were the ones that had witnessed the worst violence in the five-decade-long conflict.

The peace deal, among other things, would have led to about 5,800 FARC soldiers laying down their arms and many being granted amnesty. Those accused of more severe war crimes would have been tried under special tribunals. Sentencing would likely have been light, because, under the deal’s terms, leaders could qualify for community-service work.

Although the fate of the peace deal is uncertain, negotiators representing the government and FARC are meeting in Havana to discuss a way forward.

Santos is the second Colombian to win a Nobel Prize: Gabriel Garcia Marquez was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982.

October 6, 2016

Grappling With The Birth of a Nation

Rarely have a film’s apparent fortunes fallen so far so quickly. At Sundance this year, The Birth of a Nation, a film documenting the 1831 slave uprising led by Nat Turner, won both the grand jury and audience awards, earned its writer-director-star Nate Parker a standing ovation before the movie even screened, and sold for a festival record of $17.5 million. Since then, however, the film’s critical and commercial prospects have taken a decisive hit, from presumed Oscar frontrunner to borderline cinematic pariah.

Over the summer, the news broke widely that Parker had been charged with rape while he was a student at Penn State in 1999. Although he was acquitted at trial in 2001, his co-defendant, Jean Celestin (who is also the co-writer of The Birth of a Nation), was convicted in a ruling that was later overturned. Not long after, it emerged that the alleged victim had committed suicide in 2012. Many have found Parker’s subsequent responses to questioning on the subject inadequate.

To what degree should we judge a film by its author? How is it that the backlash against Parker, a black filmmaker, has been so much swifter than those against—to cite two obvious examples—Woody Allen and Roman Polanski? These are thorny questions, and I can only recommend that potential viewers grapple with them as best they can.

I feel more comfortable in saying that The Birth of a Nation is a good film—at times a very good one—but not the masterpiece that it was hailed to be coming out of Sundance. Parker has demonstrated himself an ambitious young director in explicitly offering his film as a rebuttal to D.W. Griffith’s original, 1915 pro-Klan The Birth of a Nation, but his ambition at times outstrips his ability. And though he also shows himself to be a powerful performer, he hasn’t yet learned how to fully share the screen with others.

Parker plays the central role of Nat Turner, who was taught to read the Bible as a boy and grew up to become a preacher to his fellow slaves. His relatively beneficent owner, Samuel (Armie Hammer), accords him certain liberties and latitudes, going so far as to purchase a pretty young slave, Cherry (Aja Naomi King), on his advice. (Nat later marries her.) But Samuel’s plantation is struggling, and it soon becomes clear that a black preacher is a valuable commodity: someone who can instruct slaves on neighboring properties that it is God’s will that they continue to obey their masters. So Samuel rents Nat out to share the gospel of racial subservience, and Nat quickly discovers that there are masters far more brutal than Samuel. The visible torment with which he counsels fellow slaves to accept the monstrous tyrannies laid upon them accounts for many of the most powerful moments of the film.

Samuel has a taste for drink, and over time his personal deterioration—as well as that of his plantation—renders him more akin to the other slaveholders in disposition. In response, Nat’s sermons adopt a more vengeful tenor, and when he’s whipped raw for the sin of baptizing a white man, his conversion to an ethos of armed rebellion is complete. “With the strength of our Father,” he tells his collaborators, “we’ll cut the head from the serpent. We’ll destroy them all.”

You don’t have to be a close student of history to know that Nat Turner’s prediction did not come to pass. Several dozen white slaveholders were killed during his brief revolt. Many more black people, slave and free alike, were killed in retribution. Parker’s film is at its best when he presents this harrowing story straightforwardly. When he strives for higher artistry—an image of a bleeding corncob, another of a black angel garbed in celestial white—the result is often closer to artifice, undermining the immediacy of the events being portrayed.

Parker’s most dubious decision is perhaps to use rape as a central narrative device.

A few scenes of African spirituality are never meaningfully integrated into the movie’s Christian themes. The score, by Henry Jackman, is at times overwrought. And the film’s distinct resemblances to Braveheart—which Parker has praised as an inspiration and cites in the credits—become tiresome, particularly in the final acts. Like Mel Gibson before him, Parker presents his protagonist as a man of nearly bottomless virtue. And though his screen presence in the role is highly compelling, one can’t help but wish for a more nuanced rendering of this deeply conflicted man.

Moreover, apart from Nat himself, the principal characters serve as little more than props. The great stage actor Colman Domingo is sorely wasted as Parker’s friend and fellow revolutionary, Hark. The female characters—slave (Aunjanue Ellis) and slaveholder (Penelope Ann Miller) alike—are modest and demure, consistently submitting to the wishes of their menfolk. And in a truly forced and tedious trope, Jackie Earle Haley plays a sadistic slave-catcher who reappears at critical junctures throughout Nat’s life: attempting to kill his father when Nat is a boy; raping and beating Cherry many years later; and, finally, engaging in a hand-to-hand struggle to the death with Nat himself.

Indeed, Parker’s most dubious decision is perhaps to use rape as a central narrative device. Nat’s journey toward rebellion is hastened not only by the rape of Cherry but also by that of Hark’s wife, Esther (played by the real-life rape survivor Gabrielle Union). As far as I can tell, there is no historical evidence that either one of these sexual violations occurred. Which brings us to perhaps the central dilemma of Parker’s powerful but problematic film: a man accused of sexually victimizing a woman in the past has now invented new sexual victims as a pretext for his onscreen character’s righteous, masculine vengeance. Whatever else one thinks of Parker’s film, this was a dire mistake.

The Birth of a Nation is not so great a film that I would encourage anyone leery of watching it to do so. But for those who remain conflicted—about its maker or its decidedly mixed messages—it’s an endeavor worthy of viewing and further consideration.

Do Hurricanes Really Induce Labor?

Oh, the tales a labor and delivery nurse can tell.

Along with the general chaos that can accompany new babies on their way into the world, all it takes is a full moon or—more dramatically—a raging hurricane to make things really interesting. That’s the conventional wisdom, anyway, among those who swear that pregnant women go into labor, en masse, during major storms.

But is it true?

With Hurricane Matthew expected to deliver a devastating blow to Florida, pregnant women are already heading to the hospital ahead of time as a precaution. Two hospitals in the Miami area are allowing some pregnant women to register for sheltering at the hospital before the storm hits, according to the local ABC affiliate there. Priority will likely be given to women who are pregnant with twins or multiples, and who are at least 34 weeks pregnant—along with other pregnant women who have been diagnosed with placental abnormalities or have a history of preterm labor.

When Hurricane Andrew hit Florida in 1992, some 1,500 pregnant women flocked to area hospitals. “I’ve never seen so many pregnant people in my entire life,” a spokeswoman for Memorial Hospital, in Fort Lauderdale, told The Sun Sentinel at the time. Some women ended up delivering their babies over the course of the hurricane—though most did not.

Still, there is evidence to support the idea that more women deliver babies at low barometric pressure—one of the key atmospheric conditions associated with a hurricane. In a 2007 paper published in the Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, researchers found “a significant increase” in pregnant women whose water broke—signaling delivery is imminent—during low pressure systems. The researchers concluded that low barometric pressure indeed induces delivery.

Additional studies have found similar outcomes, including a 1985 study that counted a “significant increase” among women whose water broke prematurely within three hours of an atmospheric pressure drop. Other meteorologic conditions seem to affect pregnancy outcomes, too. In desert climates, according to one study, the risk of preterm birth is higher in the spring and autumn, when the weather is most unstable.

There’s also a growing body of medical literature that finds links between stressful events in pregnancy—including natural disasters—and poor birth outcomes. One 2013 study, found that even if a hurricane doesn’t induce labor, exposure to a hurricane during pregnancy increases a baby’s likelihood of some abnormal conditions—like needing to go on a ventilator for more than 30 minutes after delivery. Other studies have found less decisive links—or no links at all—between hurricanes and the onset of labor, and many scientists agree the relationship between labor and hurricanes requires more study. Most women, even those who are approaching their due date, won’t deliver their babies just because a hurricane is approaching.

Yet severe storms, generally, present all kinds of potential logistical problems to expectant moms. In 2013, a Connecticut woman’s husband pulled her, via sled, so she could make it to the hospital amid heavy snow and road closures.

“In principle, hurricanes could also subject pregnant women to other negative conditions including injury, disruptions in the supply of clean water, inadequate access to safe food, exposure to environmental toxins, interruption of healthcare, or crowded conditions in shelters...” wrote Janet Currie, the author of the 2013 study, published in the Journal of Health Economics. “The primary threat to pregnant women in the path of a hurricane is the stress that is generated by the fear of the hurricane, as well as by the property damage and disruption that follows it.”

The U.S. Army Equipment That Ended Up on eBay

NEWS BRIEF Eight people, including six U.S. soldiers, have been charged with conspiring to steal equipment from the U.S. Army, federal prosecutors said Thursday.

The six soldiers allegedly stole more than $1 million worth of sensitive military equipment from the U.S. Army installation at Fort Campbell, located on the border between Hopkinsville, Kentucky and Clarksville, Tennessee. The equipment, which included sniper telescopes, machine gun parts, flight helmets, and medical supplies, was allegedly sold to two civilians, who are accused of illegally selling the stolen items to anonymous buyers on eBay. The sales were tracked to customers in Russia, China, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Lithuania, Moldova, Malaysia, Romania, and Mexico.

The soldiers charged include U.S. Army Specialists Michael Barlow, Jonathan Wolford, Kyle Heade, Alexander Hollibaugh, Dustin Nelson, and Aaron Warner. John Roberts and Cory Wilson, both civilians from Clarksville, Tennessee, were also indicted.

As The Tennessean reports, the military equipment was never intended for non-military use and was marked as “DEMIL D,” which requires that it be disposed of by the military.

Here’s more from The Tennessean:

Robert Hammer, agent in charge of homeland security investigations, said the investigation included looking at more than 1,600 online listings as well as working with the US Postal Service and investigating imports and exports.

"At a time when tensions are high between foreign nations such as China and Russia, it is disheartening as an American to see our own military members shipping stolen equipment and technology to those countries, as well as others such as Hong Kong and Ukraine," Hammer said.

Five of those indicted were in custody Thursday, and authorities are working on arresting the other three.

Each defendant was charged with one count of conspiracy and, if convicted, faces up to five years in prison and up to $250,000 in fines. Three of the men, however, face additional charges. Roberts was charged with two counts of violating the Arms Export Control Act and 10 counts of wire fraud; Wilson was charged with one count of money laundering, one count of violating the Arms Export Control Act, and seven counts of wire fraud; and Barlow was charged with three counts of selling U.S. Army property without authority.

If convicted, Roberts and Wilson could face 20 years in prison for each count of wire fraud and violating the Arms Export Control act. Each count of selling U.S. Army property without authority carries a 10-year prison sentence.

The indictment comes one day after federal prosecutors announced the arrest of Harold Thomas Martin III, a National Security Agency contractor accused of stealing classified materials from the government.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower