Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 418

June 10, 2015

The Triumph of Occupy Wall Street

On her first campaign stop in Iowa in April, Hillary Clinton struck a decisively populist tone, declaring that “the deck is still stacked in favor of those at the top.” Later, she sharpened her rhetoric on income inequality by comparing the salaries of America’s richest hedge fund managers with kindergarten teachers.

Clinton isn’t alone. Democratic presidential challenger Bernie Sanders has spent the spring railing against the excesses of Wall Street greed while calling for a financial transactions tax and a breakup of the big banks. Even leading Republican contenders have jumped on the inequality bandwagon: Jeb Bush, through his Right to Rise PAC, asserted that “the income gap is real,” while Ted Cruz admitted that “the top 1 percent earn a higher share of our income nationally than any year since 1928,” and Marco Rubio proposed reversing inequality by turning the earned-income tax credit into a subsidy for low-wage earners.

Nearly four years after the precipitous rise of Occupy Wall Street, the movement so many thought had disappeared has instead splintered and regrown into a variety of focused causes. Income inequality is the crisis du jour—a problem that all 2016 presidential candidates must grapple with because they can no longer afford not to. And, in fact, it’s just one of a long list of legislative and political successes for which the Occupy movement can take credit.

Until recently, Occupy’s chief accomplishment was changing the national conversation by giving Americans a new language—the 99 percent and the 1 percent—to frame the dual crises of income inequality and the corrupting influence of money in politics. What began in September 2011 as a small group of protesters camping out in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park ignited a national and global movement calling out the ruling class of elites by connecting the dots between corporate and political power. Despite the public’s overwhelming support for its message—that the economic system is rigged for the very few while the majority continue to fall further behind—many faulted Occupy for its failure to produce concrete results.

Yet with the 2016 elections looming and a spirit of economic populism spreading throughout the nation, that view of Occupy’s impact is changing. Inequality and the wealth gap are now core tenets of the Democratic platform, providing a frame for other measurable gains spurred by Occupy. The camps may be gone and Occupy may no longer be visible on the streets, but the gulf between the haves and the have-nots is still there, and growing. What appeared to be a passing phenomenon of protest now looks like the future of U.S. political debate, heralded by tangible policy wins and the new era of activist movements Occupy inaugurated.

One of Occupy’s largely unrecognized victories is the momentum it built for a higher minimum wage. The Occupy protests motivated fast-food workers in New York City to walk off the job in November 2012, sparking a national worker-led movement to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. In 2014, numerous cities and states including four Republican-dominated ones—Arkansas, Alaska, Nebraska, and South Dakota—voted for higher pay; 2016 will see more showdowns in New York City and Washington, D.C., and in states like Florida, Maine, and Oregon. From Seattle to Los Angeles to Chicago, some of the country’s largest cities are setting a new economic bar to help low-income workers.

Related Story

Should Conservatives Practice Civil Disobedience?

The tidal wave didn’t come from nowhere. The grassroots movement composed of fast-food workers and Walmart employees, convenience-store clerks, and adjunct teachers seized on the energy of Occupy to spark a rebirth of the U.S. labor movement. This renaissance was most recently visible on April 15, when tens of thousands of workers marched in hundreds of cities to demand better pay and conditions. McDonald’s and Walmart have responded with incremental wage hikes, and Senate Democrats this spring called for raising the federal minimum wage to $12 an hour. As Seattle City Council member Kshama Sawant, a socialist who rose to prominence with the Occupy movement, put it, “$15 in Seattle is just a beginning. We have an entire world to win.”

Occupy also reshaped the U.S.-environmental movement, which had its rebirth in fall 2011 when 1,200 people were arrested in Washington, D.C., protesting the Keystone XL pipeline. As people gravitated to Occupy encampments, teach-ins, and demonstrations across the country, that energy easily transferred into the fight against climate change. This was especially true on college campuses, where a student-led divestment movement has rid more than $50 billion in fossil-fuel assets from universities and institutional investment funds worldwide.

Occupy prompted a grassroots anti-fracking movement that pushed cities, counties and states to enact bans on the controversial drilling process—from Athens, Ohio, to Mendocino County, California, and in states like New York and Maryland. Last fall, those movements coalesced into the world’s largest climate march when 400,000 protesters descended on New York City to demand robust cuts in emissions and investments in renewable energy. President Obama has responded to the growing pressure by mandating new carbon cuts for power plants, signing a first-ever emissions-slashing deal with China, and vetoing a Republican measure to push through Keystone (although his decision in May granting permission for Shell to drill in the Arctic struck many as a disturbing reversal of his climate promises).

When it comes to money in politics, Occupy also drew mainstream attention to the corrosive influence of wealth on the political process. That helped spur a nationwide movement as 16 state legislatures and more than 600 U.S. towns and cities have passed resolutions to overturn Citizens United and draft a constitutional amendment declaring that corporations are not people and money is not speech. In April, the “We the People Amendment” to outlaw corporate personhood was introduced in the House by a Democratic coalition led by Representatives Rick Nolan (Minnesota), Jared Huffman (California), Keith Ellison (Minnesota), Matt Cartwright (Pennsylvania), and Raul Grijalva (Arizona). The message has resonated on both sides of the aisle, as presidential candidates from Clinton to Republican Senator Lindsey Graham call for a new era of campaign-finance reform to remove big money from electoral politics.

The student-debt crisis is another magnified arena where the Occupy protests shouted first and loudest—and in which serious policy shifts are now afoot. Occupy offshoot movements like Strike Debt, Rolling Jubilee, and Debt Collective are tackling America’s $1.3 trillion college-debt conundrum by buying back student debt for pennies on the dollar and forgiving it. Those movements also spurred a rebellion by student debtors, known as the Corinthian 15, who in April celebrated the closure of the for-profit Corinthian College chain, which they had accused of deceptive marketing and deliberately steering students into high-cost loans. In January, President Obama addressed the burgeoning crisis by introducing a $60 billion plan to make all community college free for two years. And in late April, nine Democratic Senators joined a list of 60 Congress members supporting a resolution to institute four-year, debt-free college nationwide—a dramatic departure from piecemeal proposals of the past.

Most significant, perhaps, is how the debate over inequality sparked by Occupy has radically remade the Democratic Party. Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts senator-who-is-definitely-not-running-for-president and the party’s most dynamic leader, launched her political career in 2012 with the 99 percent movement’s message of Main Street versus Wall Street. Since entering the Senate, Warren has drafted numerous bills to address income inequality, including the 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act that would separate investment banking from commercial banking and the Bank on Students Emergency Loan Refinancing Act that would allow students to refinance college loans at a lower federal rate. By fighting to strengthen financial regulations in Dodd-Frank, break up “too big to fail” banks, and impose stiff taxes on corporations and the wealthy, Warren is the closest thing to an Occupy candidate the movement ever got. And now an army of elected populists in both the Senate and House is unifying around her.

On a local level, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio swept into office last year on a 99-percent-style “tale of two cities” campaign to address income inequality. He has since expanded pre-K education for tens of thousands of students, created municipal ID cards for undocumented immigrants, increased affordable housing, and guaranteed sick days for workers in America’s largest city. De Blasio now leads a national task force of mayors who hope to aggressively tackle the wealth gap in their cities—something scarcely imaginable before Occupy reshuffled the political deck.

Occupy was, at its core, a movement constrained by its own contradictions: filled with leaders who declared themselves leaderless, governed by a consensus-based structure that failed to reach consensus, and seeking to transform politics while refusing to become political. Ironic as it may seem, the impact of the movement that many view only in the rearview mirror is becoming stronger and clearer with time. Since the Great Recession, shareholder profits, CEO pay, and corporate tax breaks have soared while average household wealth continues to sink, college debt skyrockets, living costs increase, real wages decline, and the middle class struggles to survive. The world’s 1 percent now possess almost as much combined wealth as the bottom 90 percent. And while no one in Washington may have the full answer about how to fix income inequality, everyone, it seems, is now grasping for a solution.

It won’t be easy. Wresting power from the ruling financial elites will be an ongoing challenge, and ending big money’s grip on politics lies at the core of this effort. But business as usual must change because the planet can’t wait, and the people can’t, either. Occupy got the diagnosis correct. It also charted the course for concrete legislative reform. It’s now up to elected officials to achieve much bigger results—and for the grassroots movements to continue driving those policies into being. Because as millions of Americans learned following the election of Barack Obama, real change doesn’t come in slogans: It comes when the people demand it.

June 9, 2015

Why Aren't Women's Sports as Big as Men's? Your Thoughts

With the women’s World Cup in full swing this week, The Atlantic has two pieces examining the differences that female soccer players face compared to their male counterparts. Arguing that soccer is a “feminist issue,” Maggie Mertens is frustrated that female players don’t get much attention from the mainstream media and feminist activists alike. Gwendolyn Oxenham, a former pro, hones in on the “unequal fortunes” of Brazilian superstars Neymar, a man who makes $15 million a year, and Marta, a woman struggling to even find a team without it folding soon after.

Mertens’s piece was the most contentious among Atlantic commenters. A key passage:

The thinking goes that if women’s sports were worthy of more coverage, they would receive it. But as [Perdue professor Cheryl Cooky] points out, a lot of our perceptions of how interesting women’s sports are come from the media itself. “Men’s sports are going to seem more exciting,” she says. “They have higher production values, higher-quality coverage, and higher-quality commentary ... When you watch women’s sports, and there are fewer camera angles, fewer cuts to shot, fewer instant replays, yeah, it’s going to seem to be a slower game, [and] it’s going to seem to be less exciting.”

TheMeInTeam doesn’t buy it:

This week’s cover of Sports Illustrated

I would have found this article more interesting if the author could have just conceded the obvious fact that elite female athletes are simply not equal to their male counterparts in terms of physical ability—kind of an important thing for an athlete, unlike in other professions. Look at any world record, or watch an NBA and WNBA game back-to-back. The difference is real and impossible to ignore. It’s just physiology.

To put it another way, who would have the advantage in any athletic competition you can think of: an elite female athlete or her identical twin who trained just as hard but also took testosterone injections from the age of 12?

TwoHatchet snarks, “Caitlyn Jenner has shown the world that women can compete at the very highest levels of sport and leave men in the dust.” Field Zhukov’s view:

Women’s sports that are identical to men’s sports—soccer and basketball, for example—will never be popular, because men are faster, stronger and more athletic. On the other hand, sports that highlight the different strengths of female athletes—tennis, gymnastics, ice skating—are popular. None of those are team sports, so there may be something there.

Tg297527 adds, “No one cares about men’s gymnastics and men’s figure skating.” TheMeInTeam responds to Field Zhukov:

I think you may be on to something about the difference with team sports. When the Olympics come around (winter and summer), I enjoy the women’s and men’s events pretty much equally. The women may be running/swimming/skiing slightly slower than their male counterparts, but I can’t really tell, and it’s just as exciting. For some reason, however, when it comes to team sports where I’m used to watching men, that slight difference in physical ability becomes glaringly obvious and I just can’t stay interested in the women.

PeterJakes doesn’t see it that way:

One of the best soccer matches I ever saw, men or women, was Canada versus USA in the 2012 Olympics.

Canada’s Christine Sinclair put her team on her back and almost carried them into the Gold Medal match, only to be thwarted by questionable officiating. That game represented the beauty of athletic competition.

GeorgeOrwellGeorge points to a sport where relative female weakness is actually an asset for spectating:

I actually prefer watching women’s tennis. Men hit the ball so hard, particularly on the serve, that there’s less volleying and it’s less exciting to watch.

Likewise, Diozkouroi looks to another sport to argue that physical dominance isn’t everything:

If people only paid attention to the top performers, there would be no categories apart from “heavyweight” in sports like boxing. Floyd Mayweather can get easily beaten by a heavyweight, but he is the one who gets more money and attention in that sport.

And by my count, only 19 of the 50 “greatest boxers of all time” fought primarily as heavyweights, and likewise for only half of the “most popular of all time.” As vkg123 puts it, “People don't make stupid comparisons like Mike Tyson vs Manny Pacquiao, and it doesn't stop people from enjoying one or the other.” A retort from ksmugg:

That’s a fair point, but it’s generally one that’s distinct to individual competition instead of team sports. I’m curious if you or anyone else can provide an example in a team sport.

Maybe women’s volleyball? According to this study:

Women earn fewer quick points than men due to differences in arm strength, so digging becomes essential to victory for women. With the ball in play longer, staying alive determines the winner of a match.

And those rallies can get really amazing:

Another way that men can slow down a game:

You know how in men’s soccer, a strong wind is enough to knock a player over [and] they play-act like babies? The women don’t have time for that. According to a study, women fake injury half as much as men do. And when they are on the ground rolling around, they’re back up 30 seconds faster than men.

Commenter j r turns the debate toward equal pay and Mertens’s frustration that “female athletes have historically received very little attention from activists and advocates for gender equality”:

Somewhere in this world, there is the world’s greatest ultimate frisbee player and the world’s greatest lawn bowler. Chances are, you don't know their names and they probably don’t make much money. Why? Because not a lot of people are willing to pay to watch ultimate frisbee and lawn bowling.

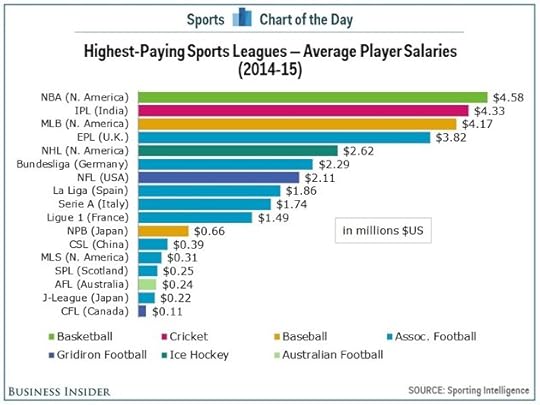

For that matter, compare the salaries of Major League Soccer players to those playing in Europe’s La Liga or the English Premier League. The former get paid a lot less for the same reasons.

If the day comes when as many people want to pay to watch women’s soccer as want to watch men’s soccer, then female players will earn similar money. That’s it. End of story.

Another simple but strong argument from Ivan Lendl:

They are entertaining and inspirational to young women all over the world. For that reason, they have great value, and I think they are worthy of charitable help when teams get insolvent.

But let’s not pretend that there is some sexist conspiracy driving the pay discrepancy between Neymar and Marta. If she were able to compete on the same level as Neymar, she would, and she’d be compensated accordingly.

BatmanDontShiv isn’t as charitable:

Oxenham’s article doesn’t really address why women’s soccer should be given charity by men’s organizations if it can’t survive on its own. If enough female fans can’t be bothered to get together and support women’s teams so they can remain solvent, why should men care?

A similar view from d1onys0s:

If women want to support their own gender by becoming sport fanatics like the droves of idiot men, there is nothing stopping them. They appear to have other interests and that’s totally fine … isn’t feminism about doing whatever you as an individual want to do?

But Diane (DeeG) thinks the cards have been too stacked against female athletes:

After centuries of getting all the advantages over women in every aspect of life, of course men’s sport is more “popular.” As those advantages are starting to be shared on a more equal footing, more people are deciding that they like women’s sports.

Men’s and women’s soccer may be the same game, but they don't have to be played identically to be appreciated.

Fox Sports is banking on that sentiment, with this stirring ad:

Insanedreamer takes a step back:

I’m 100 percent in favor of equal opportunity and equal pay. But in the entertainment business (which is what sports is), there is inherently huge inequality based on what’s popular or not.

In another part of the entertainment business, pop music, there is more gender parity; women hold four of the top 10 slots for wealth among recording artists, including the #1 slot, which goes to Madonna. In the acting world, however, men sweep the top 10. Back to sports, tennis seems to be the only place of parity—five of the top 10 earners are women. But that causes Thurman Ulrich to complain:

The four Grand Slam tournaments pay women the same cash prize as it does for men, despite the fact that men have to play two more sets than women.

Cxt points to general disparities across the sports world:

The best track and field athletes don't make as much as most basketball players. The strongest men in the world and the toughest MMA fighters only make a fraction of the endorsement money of golfers like Tiger Woods or tennis players like Maria Sharapova. Baseball players make much more than football players, despite their sport having less chance of serious injury and a much longer playing life.

Yes, it sucks to be that talented yet not as financially rewarded, but that is the nature of spectator sports.

A snapshot of those varying rewards:

TwoHatchet tries to simplify things when it comes to sports and gender:

Mertens’s argument seems to be that women are equal to men and it’s only discrimination causing the disparity of results. The solution here is simple: abolish women’s soccer and open up men’s soccer to women. Now we can compare, person to person, how well each player performs and teams can be composed of the best players, both men and women.

On that note, Luke asks:

Why doesn’t Marta play for a men’s team? That hasn’t been mentioned. Is it because she isn’t good enough or not allowed?

Hope Solo makes a save. (Ben Nelms / Reuters)

Former Serie A side Perugia attempted to sign German international Birgit Prinz and Sweden striker Hanna Ljungberg in 2003, while Brazilian forward Marta has continually claimed she could cut it in a men’s league. Meanwhile, Mexican club Celaya actually announced it had signed El Tri’s Maribel Dominguez in 2004, but FIFA stepped in to veto the move, and [U.S. goalie Hope] Solo says it was wrong.

“It’s unfortunate that it wouldn’t be allowed by FIFA because I think as women, we need a place to play and there’s not always a lot of opportunities to become the best in the world, and if you look at the players who want to do it, they want to be the best in the world; the Martas, Maribel Dominguez, the Ljungbergs,” Solo said. “I think it should be allowed if it’s fair and if they deserve to be on the team. Not out of charity.”

Dr_Ads takes that notion of equality to a radical end:

If there were such a thing as an equality movement, as opposed to a feminist movement, there would be calls for the abolition of “men’s” and “women’s” sport. Gender is an arbitrary distinction, and it’s just as wrong to divide people by gender as it would be to have separate races for black sprinters and white sprinters to give the latter a chance of winning.

I’m opposed to the Paralympics for the same reason. Want people with disabilities to be treated identically to the able-bodied in society? Then stop making them a special case.

Tim Gabin has a more creative approach:

It’s the copycatting that is limiting female professional sports. I think it’s time the brains behind these feminist ambitions started inventing sports that women are particularly good at, ones that fit the female anatomy, physiology, and skill set. That is when the fun begins. Stop using male role models and male athletic archetypes to create meaning and legitimacy. Start making something new—that everyone will love.

Phil Heinricke simply wants skeptics of women’s soccer to give it a second look:

I asked some people if they intended to watch the World Cup. They all said hell no. But then someone turned on the TV and Germany was playing, and a young woman they were calling "Sausage" (real name Sasic) was kicking some tail. [Yesterday she led Germany to a 10-0 victory 10-0 victory over Ivory Coast, the second-biggest in World Cup history:

The people watching the German game were impressed with the women’s ball handling skills, their teamwork and their propensity to always be in position. Three men sat there and watched the whole game.

Sasic and Marta aren’t the only talented female athletes. There is Debora, Beatriz Zaneratto, Andressa Alves, Thaisinha, young Byanca and the baby-faced Andressinha—and that’s just Brasil.

I’m a big fan who has always said that the problem is that people just don't want to watch the women, but I think if they at least gave them a chance, a lot of people would like it.

You can track the following month of World Cup matches here. For daily coverage, check out espnW and Screamer.

GE’s First Steps Away From Banking

General Electric (GE) will sell its private-equity lending unit to the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) in a deal valued at $12 billion. This deal is the first in the company’s effort, announced in April, to unload $100 billion of assets from GE Capital by the end of the year. The total assets of GE’s finance arm is a number that’s currently up for debate, but it’s estimated to be in the $300 to $500 billion range.

GE’s decision to sell of GE Capital was born of a desire to concentrate on the company’s roots: the business of manufacturing equipment for various industries. Jeff Immelt, GE’s CEO, says the company expects to generate 90 percent of its earnings from “high-value industries” such as aviation, energy, and healthcare equipment by 2018.

GE was formed in 1892 in a merger between Thomas Edison’s Edison General Electric Company and its competitor Thomas-Houston Company. The company’s name brings to mind washing machines and jokes on 30 Rock. GE Capital, GE’s “shadow bank,” started in the 1980s, and at one point contributed significantly to GE—some years as much as half of the company’s profits. However, this dependence on GE Capital became a problem following the financial crisis. Immelt’s decision to sell off GE Capital’s assets has been seen as “exorcising the financial demons” of his predecessor Jack Welch, who started GE Capital and has been criticized for GE’s dependence on GE Capital.

CPPIB is the investment arm of the Canada Pension Plan. Nearly every worker over 18 in Canada contributes to this fund; it covers retirement pensions and benefits, disability benefits, and after-death benefits for Canadians. The CPPIB manages the assets of 18 million Canadians contributing to the pension plan, about $265 billion. Investing in private equity has been a trend for pension funds in recent years, the Canadian style of pension fund investing has been praised for operating like an asset-management business and paying its officials like bankers. The fund just had its best year on record with an 18 percent return for the fiscal year ending March 31. Last year, CCPIB bought the U.S. insurance company Wilton Re Holdings for $1.8 billion.

The lending business in America isn’t what it used to be, and as Paul Krugman writes, selling off GE Capital might mean that financial reform and greater oversight is working. But it’s not only that: As people living in developing countries get richer, they’re starting to want the kind of products GE is expert at. Perhaps there is a second life yet to come for American manufacturing, but it’ll look very different: Higher tech products, purchased by consumers all over the world.

How Activists Intend to Force the Arrest of Police Officers

It’s been 199 days since Tamir Rice was shot to death by a Cleveland police officer. And for a group of community leaders in the Forest City, that’s too long to wait for prosecutors to charge the officers involved in the shooting. Instead, they went to a municipal court judge Tuesday morning and asked him to issue a warrant for the officers on charges of murder, aggravated murder, involuntary manslaughter, reckless homicide, negligent homicide, and dereliction of duty.

If that sounds confusing, it’s not just you. The activists made the request under an obscure provision of Ohio law that entitles citizens to file an affidavit demanding an arrest. While a few other states have similar clauses, the law is little-known and seldom-used—especially in cases of murder. A close reading of the statute suggests that it’s unlikely to seriously change the direction of the case, since any murder charge ultimately has to go through a grand jury. But the filing of affidavits sends a signal, and might add some pressure on the prosecutor to file charges against Officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback.

“What you see here is one of the most American things I’ve seen in my life,” said Walter Madison, an attorney for the Rice family, at a press conference on the courthouse steps after filing the affidavits. “The people have taken the opportunity to make the government work for them. This is not a circumvention. This is simply applying the law that is available.”

Related Story

Can the Feds Clean Up Cleveland's Police Force?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the union representing Cleveland police did not agree, calling it an attempt to “hijack rule of law.” Yet the statute is clear—the coalition behind the affidavits is well within its rights. (The full filing is here.) The law states: “A private citizen having knowledge of the facts who seeks to cause an arrest or prosecution under this section may file an affidavit charging the offense committed with a reviewing official...” As long as the judge or magistrate who receives the affidavits finds them to be both in good faith and valid, he or she has to issue the warrant.

In this case, it seem clear that the activists are working in good faith—they truly believe a crime was committed. It also seems clear that there’s probable cause, as anyone who has seen the video of Rice’s shooting can attest. Even if a trial court were ultimately to rule that Loehmann was justified in firing on Rice, all evidence suggests that a homicide was committed and justifies an arrest.

A judge could take another tack, deciding that the petition was either in bad faith or didn’t show probable cause. In that case, he or she would refer it to a prosecutor—essentially sending things back to right where they are. But how likely is that?

“It seems to me that the judge would have no choice but to issue a warrant.”“Given the video evidence of the case and whatever else they have, including the police officers’ report, I’d think the judge would be hard-pressed to say it’s not filed in good faith, and that the claim is at least meritorious,” said Michael Benza, a senior instructor in criminal law at Cleveland’s Case Western Reserve University Law School who’s been following the case. “It seems to me that the judge would have no choice but to issue a warrant.”

The decision could come quite quickly. Judges and magistrates generally move quickly on issuing warrants, though this one might take longer since it’s a murder case and uses a little-known law.

From there, however, things get messier. For one thing, police can’t be compelled to go out and haul Loehmann and Garmback in; as Benza noted, there are legions of people out on the streets with warrants against them. And even if the officers were arrested, it’s unclear what would happen next. Any murder charge in the state of Ohio has to go through a grand jury.

“There is no means to compel a prosecutor to take a case to a grand jury,” Benza noted. “Even if the judge would issue an arrest warrant, it still doesn’t force a prosecution. This statute does not allow a private person to take a case to a grand jury.”

In fact, there seem to be very few cases where the statute in question has led to prosecutions. Benza said he’d been unable to find a single case that went forward—although, he noted, there may be others that did but aren’t easily discoverable because they don’t cite the law. And he did find several cases in which clerks ordered courts to accept the affidavits. The oddball nature of the law means that many attempts to obtain warrants under it tend to be frivolous—for example, a convicted criminal attempting to obtain warrants for witnesses against him, alleging that they had perjured themselves while putting him behind bars.

Ohio’s law is unusual but not unique. North Carolina has a similar law (as you can find out in this somewhat diverting account of a war between a mayor and town commissioner in Belville, North Carolina, population 1,936), and so does New Jersey. The Buckeye State’s law dates to 1960, but Benza said he’d found references to what appeared to be similar laws farther back. In fact, the idea of allowing citizen complaints harkens back to a much, much older age in the English legal tradition. As Lawrence Friedman notes in Crime And Punishment In American History, around the time England was colonizing the U.S., private citizens were in charge of bringing accused criminals before the system:

One striking aspect of trial was the system of private prosecution. English law had no district attorney, no public prosecutor. If you were a shopkeeper, and you caught a thief robbing your store, it was your responsibility to bring him to justice. A constable might help you chase and catch the thief; but that was all. In any event, the money for the prosecution would have to come out of your pocket.

What’s happening in Cleveland is an ironic twist on that outdated system. Professional prosecutors were intended to make the system more equitable and fair, by eliminating the need for citizens to front the financial resources necessary for prosecutions. But activists in Cleveland are reaching back to the older system of private prosecution, because they feel that the official channels have been insufficiently responsive.

Whether the system is actually non-responsive is a different question. Rice’s family and its allies are understandably upset that months after a shooting captured on camera, there have been no charges. In some ways, that’s a clear travesty of justice. But prosecutors are working on the case, and say that their investigation is ongoing. As clear as the facts might seem, cases in which officers shoot citizens almost always take a great deal of time. As David Jaros, an associate professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law, told me in May, that’s because the justice system works for police officers in much the same way that people (incorrectly) expect it to work for ordinary citizens. In contrast to run-of-the-mill crimes, district attorneys tend to be exhaustive and meticulous with officer-involved shootings.

One reason for that is that prosecutors have an interdependent relationship with police: They rely on the cops to arrest people, bring them in, and testify against them. As the tension between Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby and the Baltimore Police Department has shown, bringing charges against officers can create strained relationships. In the Rice case, County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty has shown the dangers of erring too far in the other direction, producing concern that he’s not serious about the case. But can the activists succeed in altering his course?

“From a legal standpoint, they should be able to get arrest warrants for these officers to be issued, but after that the case goes back to exactly where it is now,” Benza said.

The affidavits may be an effective way to place public pressure on McGinty, but the Rice case is still ultimately going to come down to prosecutorial discretion.

The Great Lie of Apple Music

Drake started from the bottom, now he’s at Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference to tell you about a great new product. He took to the stage in San Francisco on Monday with a swagger, joking about the Internet being the next big thing and showing off the vintage Macintosh-computers jacket he’d acquired online. Then he turned to the topic of “the way technology changed what I do for a living,” and … started … talking … more slowly … at times appearing to lose his train of thought.

As is often the case with Drake, there was a everyman-turned-titan narrative to fudge. “I always wondered if my city [Toronto] or country [Canada] would have someone break into the global music scene as a true superstar,” he said. It wasn’t the people in “towering New York label buildings” who helped him become that superstar. It was the Internet, and the ability to release music directly to the public. “This approach is how we broke in 2008,” he said, referring to the blogs, social-media platforms, and mix-tape distribution sites the TV actor used to first build a rap fanbase. “And it has been, of course, perfected and simplified by the great people at Apple.”

Related Story

The Golden Age of Online Music Is Over (and Another Is Beginning)

Perfected and simplified—that’s the essence of Apple’s pitch for its forthcoming music app. Apple Music gathers three kinds of online music experiences into one place: all-you-can-listen-to streaming a la Spotify, radio stations à la Pandora or I Heart Radio, and a publishing and outreach platform for artists similar to YouTube, Facebook, Tumblr, or Soundcloud. As The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer has noted, innovation is not on offer, but the rhetoric of the presentation said that consolidating features under the Apple logo will change the industry by making things more convenient and accessible for artists and listeners alike. Supposedly, this will enable more success stories like Drake’s. If it succeeds, it will also shore up the market position of the company whose once-dominant iTunes has been threatened by streaming, though that business imperative went unmentioned.

Jimmy Iovine, the famed Interscope founder who’s now on Apple’s payroll, lamented the fact that the music industry has become a “fragmented mess,” where artists have multiple ways of reaching the public and the public has multiple ways of hearing them. Left unsaid was that this state of affairs has allowed a certain Canadian rapper, a certain Canadian YouTube singer, and plenty of other new artists to find success over the past decade or so. Using Apple’s promotional dollars, tech advantage, and brand allure to try and get everybody into the same system might provide an easier way for DIY musicians to reach a mass audience. Or it might make traditional gatekeeper figures all the more important—and make the gatekeepers who work for Apple even more so.

Tidal, launched by Jay Z and a group of other celebrity musicians a few months ago, also offers streaming, hand-picked playlists, and ways for artists to publish new content. Its Nietzsche-quoting press conference will go down in history as one of the most self-important marketing events of all time, with lofty promises to transform the industry, restore music’s “dignity,” and help connect fans and artists in new ways. Anyone who watched that presentation might have felt some déjà vu during the Apple Beats announcement on Monday. “There needs to be a place where music can be treated less like digital bits but more like the art it is, with a sense of respect and discovery,” Trent Reznor proclaimed in a video, and he may as well have been Jack White stumping for Tidal.

The language of social change has been part of the marketer’s toolkit for decades, so it’s hard to imagine that many consumers are impressed by abstract vows to revolutionize music consumption, especially when absolutely no new ways of consuming music are on offer. But it’s still worth noting how hollow, and arguably hypocritical, the recent streaming wave’s professed loyalty to the idea of music as art and not product has been. Apple and Tidal portray the world that currently exists—in which people download from a variety of sources, stream from a variety of sources, and find new music from a variety of sources—as degrading, not democratic, and say they want to class the place up. Apple’s Beats1 Radio station, anchored by mega-DJ Zane Lowe, was touted on Monday as being a place that will only play the “best” music, as if there’s one way of determine such a thing. Siri will even play you the “best” song by any given artist. Who knows what that means?

Siri will now play you the “best” song by any given artist. Who knows what that means?If there’s an existential problem with the music ecosystem today, a lot of musicians would say it’s the fact that too few people are paying to listen, which means artists have an even harder time making enough money to survive. The Apple presentation didn’t attempt to address this. Spotify gives 70 percent of its revenues to musicians and their labels; Tidal gives 75 percent; each individual artist’s cut is determined by the proportion of total streams they receive from users. Apple hasn’t said what its royalty percentages will be, but what really matters is the amount of money being paid into the system in total—there currently aren’t enough streamers for companies like Spotify to either make much cash or dole much out. Reports say that Apple is shooting to have 100 million paid users, which indeed could mean a huge windfall for the music industry, given that there are only 41 million people paying for all the other streaming platforms currently available. (The price for the Apple service is $10, the streaming-world standard. There’s also a $14.99 family option that will enable six different users on one account.)

To hit that goal, Apple Beats will need everyone and their dad to sign up, lured by Apple’s enormous reach, endorsements from the likes of Drake, and, yes, a degree of high-minded marketing nonsense. The Beats presentation opened with a video outlining the history of music’s evolution, and you could probably storyboard it sight unseen: phonographs to tape decks to CDs to iPods, all set to jaunty percussion. Jimmy Iovine came out to state a self-evident truth: “Technology and art can work together.” Then came the addendum. “At least, at Apple.”

June 8, 2015

Stan Wawrinka: Tennis’s Unlikely, Deserving Champion

The most remarkable thing about Stanislas Wawrinka isn’t his backhand, the devastatingly effective shot that confounded the world number one Novak Djokovic (whose backhand is often cited as the best in men’s tennis) throughout Sunday’s French Open final. And it’s not that Wawrinka was able to upset Djokovic, who prior to Sunday’s match appeared invincible on the red clay of Paris, 4-6, 6-4, 6-3, 6-4 to win his first French Open title. It’s that Wawrinka doesn’t look or comport himself like a Grand Slam champion. From his bright pink “pajama” shorts to his faintly dadboddish physique, the Swiss native looks more like someone you’d find at Home Depot than Roland Garros.

Related Story

Explaining the U.S. Tennis Slump

Each member of tennis’s “big four” possesses an aesthetic that’s both impressive and defined by something singular: Djokovic’s sinewy flexibility, Rafael Nadal’s bulging muscles, Andy Murray’s tree-trunk legs and veined-forearms, Roger Federer’s lithe grace. But when Wawrinka walks on the court, he doesn’t exactly look like a world-class athlete. His shorts tend to ride a bit too high; his shirts always seem loose in all the wrong places. Tennis is a sport where players value personal appearance and strive to take the court looking impeccable and exuding style. Wawrinka, as he did on Sunday, often starts matches with sunscreen residue on his nose and cheeks, like a teenage lifeguard preparing for a long day at the pool. His signature shorts look like something your uncle might wear after rummaging through the attic. Style has never been his strong suit.

This isn’t to criticize Wawrinka’s sartorial choices so much as it’s to affirm that upon first glance he might not seem like a player capable of demonstrating mind-blowingly beautiful tennis. But that’s exactly what he did on Sunday, en route to the second grand-slam title of his career. Wawrinka didn’t just defeat Djokovic; he displayed shot-making prowess of the highest order. His line-licking forehands and exquisitely angled backhands served as a reminder that tennis, when played at the highest degree, has as equal claim to the appellation “the beautiful game” as soccer or any other sport. Wawrinka’s play incited so many “oohs” and “ahs” from the fans who gathered on court Philippe Chatrier on Sunday that it seemed at times as if they were witnessing a magic show or particularly adroit circus performance. He hit one backhand that has to be seen to be believed. Few, if any players—perhaps Roger Federer in his prime of primes—can say they simultaneously wowed an audience and thoroughly beat down a high-caliber opponent in quite the same way Wawrinka did.

His triumph means several things. It means he will never again live in the shadow of Federer, whose one victory at the French Open came at the expense of the inconsequential Robin Söderling (as opposed to a player of Djokovic’s caliber). It means he’ll step out of the circle of tennis’s one-hit wonders; players like Gaston Gaudio and Thomas Johansson, who won a single grand-slam title and subsequently disappeared into professional irrelevance. It means that the men’s game truly exists in a post-big four era—three of the past six grand-slam championships have been won by players outside that elite quartet, and Wawrinka owns two of those titles. It means he has as good a chance as any player on tour to win Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. (If he continues to play as he did during the past two weeks, there might not be a player who can beat him.)

At first glance, Wawrinka’s ascension may seem unlikely. The 30-year-old spent the early part of his career toiling outside the top five, looking like a player who’d define himself by getting knocked out of major tournaments before the quarterfinals. He didn’t win his first grand-slam championship until the age of 28; he didn’t win his first Master’s 1000 title until a few months later. Wawrinka’s late rise to world-class player is, however, indicative of a broader trend in men’s tennis: A sport that once favored fresh-faced youngsters has become the dominion of more seasoned statesmen. As NPR's social-science correspondent Shankar Vedantam reported in 2014, the average age of top players increased from 25 to 28 between the mid-early 2000s and 2014. Wawrinka has partially credited his late-career bloom to the former ATP pro Magnus Norman joining his coaching team, saying Norman has imbued him with a mental toughness and degree of self-belief that had been lacking in the past. He displayed that mental toughness throughout Sunday’s final. He never lost his cool, even after dropping the first set, but rather went for big shots without hesitation until he had effectively hit Djokovic right off the court.

A sport that once favored fresh-faced youngsters has become the dominion of more seasoned statesmen.The outcome of Sunday’s French Open final also means that Djokovic’s career is becoming increasingly difficult to define. For the past four and a half seasons, Djokovic has, without question, been the most dominant player in the men’s game. During that time he’s won 19 Masters 1000 titles and three ATP World Tour Finals. He’s spent more weeks ranked at number one than any other player. And he’s accomplished all of this with a game that’s so clinical and systematic that it seems unassailable. He is, in other words, the kind of player analysts and casual fans alike expect to win several grand-slam championships each season. At the start of every major tournament, he always appears untouchable.

Yet Djokovic’s loss to Wawrinka brings his career record in grand-slam finals to eight wins and eight losses, a number that confirms both his ability to reach the highest stages of his sport and his frequent inability to cross the finish line. He’s not a choke artist per se—the losses he’s suffered are excusable in that they’ve come at the hands of players in peak form—it’s just he’s curiously unable to seal the deal at grand slams with the same ruthless efficiency he regularly dispenses at lesser tournaments. Of all the Open-era tennis players who’ve won at least eight grand-slam titles, only Djokovic and Ivan Lendl don’t have winning records in grand-slam finals.

In all fairness, Djokovic played the more impressive tournament—he defeated Nadal in straight sets in the quarterfinals, marking only the second time the Spaniard has fallen at Roland Garros. Djokovic also stopped a red-hot Murray in a tough semifinal match that stretched over the course of two days. Wawrinka’s path to the trophy wasn’t nearly as formidable, and yet what most people will remember from the 2015 French Open is that Djokovic once again failed on his sport’s biggest stage while his opponent put on a show for the ages.

Wawrinka’s beautiful, attacking tennis trumped Djokovic’s nearly impervious defensive style. The match was both breathtaking and surprising. And the fact that such stunning tennis was displayed by a player with such an unassuming, almost goofy demeanor makes it all the more remarkable.

Stan Wawrinka: Tennis’ Unlikely, Deserving Champion

The most remarkable thing about Stanislas Wawrinka isn’t his backhand, the devastatingly effective shot that confounded the world number one Novak Djokovic (whose backhand is often cited as the best in men’s tennis) throughout Sunday’s French Open final. And it’s not that Wawrinka was able to upset Djokovic, who prior to Sunday’s match appeared invincible on the red clay of Paris, 4-6, 6-4, 6-3, 6-4 to win his first French Open title. It’s that Wawrinka doesn’t look or comport himself like a Grand Slam champion. From his bright pink “pajama” shorts to his faintly dadboddish physique, the Swiss native looks more like someone you’d find at Home Depot than Roland Garros.

Related Story

Explaining the U.S. Tennis Slump

Each member of tennis’ “big four” possesses an aesthetic that’s both impressive and defined by something singular: Djokovic’s sinewy flexibility, Rafael Nadal’s bulging muscles, Andy Murray’s tree-trunk legs and veined-forearms, Roger Federer’s lithe grace. But when Wawrinka walks on the court, he doesn’t exactly look like a world-class athlete. His shorts tend to ride a bit too high; his shirts always seem loose in all the wrong places. Tennis is a sport where players value personal appearance and strive to take the court looking impeccable and exuding style. Wawrinka, as he did on Sunday, often starts matches with sunscreen residue on his nose and cheeks, like a teenage lifeguard preparing for a long day at the pool. His signature shorts look like something your uncle might wear after rummaging through the attic. Style has never been his strong suit.

This isn’t to criticize Wawrinka’s sartorial choices so much as it’s to affirm that upon first glance he might not seem like a player capable of demonstrating mind-blowingly beautiful tennis. But that’s exactly what he did on Sunday, en route to the second grand-slam title of his career. Wawrinka didn’t just defeat Djokovic; he displayed shot-making prowess of the highest order. His line-licking forehands and exquisitely angled backhands served as a reminder that tennis, when played at the highest degree, has as equal claim to the appellation “the beautiful game” as soccer or any other sport. Wawrinka’s play incited so many “oohs” and “ahs” from the fans who gathered on court Philippe Chatrier on Sunday that it seemed at times as if they were witnessing a magic show or particularly adroit circus performance. He hit one backhand that has to be seen to be believed. Few, if any players—perhaps Roger Federer in his prime of primes—can say they simultaneously wowed an audience and thoroughly beat down a high-caliber opponent in quite the same way Wawrinka did.

His triumph means several things. It means he will never again live in the shadow of Federer, whose one victory at the French Open came at the expense of the inconsequential Robin Söderling (as opposed to a player of Djokovic’s caliber). It means he’ll step out of the circle of tennis’ one-hit wonders; players like Gaston Gaudio and Thomas Johansson, who won a single grand-slam title and subsequently disappeared into professional irrelevance. It means that the men’s game truly exists in a post-big four era—three of the past six grand-slam championships have been won by players outside that elite quartet, and Wawrinka owns two of those titles. It means he has as good a chance as any player on tour to win Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. (If he continues to play as he did during the past two weeks, there might not be a player who can beat him.)

At first glance, Wawrinka’s ascension may seem unlikely. The 30-year-old spent the early part of his career toiling outside the top five, looking like a player who’d define himself by getting knocked out of major tournaments before the quarterfinals. He didn’t win his first grand-slam championship until the age of 28; he didn’t win his first Master’s 1000 title until a few months later. Wawrinka’s late rise to world-class player is, however, indicative of a broader trend in men’s tennis: A sport that once favored fresh-faced youngsters has become the dominion of more seasoned statesmen. As NPR's social-science correspondent Shankar Vedantam reported in 2014, the average age of top players increased from 25 to 28 between the mid-early 2000s and 2014. Wawrinka has partially credited his late-career bloom to the former ATP pro Magnus Norman joining his coaching team, saying Norman has imbued him with a mental toughness and degree of self-belief that had been lacking in the past. He displayed that mental toughness throughout Sunday’s final. He never lost his cool, even after dropping the first set, but rather went for big shots without hesitation until he had effectively hit Djokovic right off the court.

A sport that once favored fresh-faced youngsters has become the dominion of more seasoned statesmen.The outcome of Sunday’s French Open final also means that Djokovic’s career is becoming increasingly difficult to define. For the past four and a half seasons, Djokovic has, without question, been the most dominant player in the men’s game. During that time he’s won 19 Masters 1000 titles and three ATP World Tour Finals. He’s spent more weeks ranked at number one than any other player. And he’s accomplished all of this with a game that’s so clinical and systematic that it seems unassailable. He is, in other words, the kind of player analysts and casual fans alike expect to win several grand-slam championships each season. At the start of every major tournament, he always appears untouchable.

Yet Djokovic’s loss to Wawrinka brings his career record in grand-slam finals to eight wins and eight losses, a number that confirms both his ability to reach the highest stages of his sport and his frequent inability to cross the finish line. He’s not a choke artist per se—the losses he’s suffered are excusable in that they’ve come at the hands of players in peak form—it’s just he’s curiously unable to seal the deal at grand slams with the same ruthless efficiency he regularly dispenses at lesser tournaments. Of all the Open-era tennis players who’ve won at least eight grand-slam titles, only Djokovic and Ivan Lendl don’t have winning records in grand-slam finals.

In all fairness, Djokovic played the more impressive tournament—he defeated Nadal in straight sets in the quarterfinals, marking only the second time the Spaniard has fallen at Roland Garros. Djokovic also stopped a red-hot Murray in a tough semifinal match that stretched over the course of two days. Wawrinka’s path to the trophy wasn’t nearly as formidable, and yet what most people will remember from the 2015 French Open is that Djokovic once again failed on his sport’s biggest stage while his opponent put on a show for the ages.

Wawrinka’s beautiful, attacking tennis trumped Djokovic’s nearly impervious defensive style. The match was both breathtaking and surprising. And the fact that such stunning tennis was displayed by a player with such an unassuming, almost goofy demeanor makes it all the more remarkable.

A Prison Escape From 'Little Siberia'

The daring prison break in Dannemora, New York, that launched a thousand Shawshank Redemption references (and even one side-by-side comparison) still remains unsolved.

Convicted murderers Richard Matt and David Sweat, who were said to have used power tools to dig their escape route, are still at large. A $100,000 reward has been posted as a search continues both in the United States and Canada, just 40 miles north of the Clinton Correctional Facility, the maximum-security prison where the men were serving time.

The escape is as baffling as it is unprecedented. The two were reported missing from their cells during a 5:30 a.m. bed check on Saturday morning. The men had been replaced by dummies made of sweatshirts in their beds. As The Washington Post relayed, “it was the first time that anyone had escaped from the maximum-security portion of the institution, which has been open since 1865 and is known as ‘Little Siberia’ because of its isolated location and the region’s harsh winters.” Following the weekend, with a massive manhunt already underway, one official warned that the two men “could literally be anywhere.”

In a Monday press conference, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo told reporters that he believes the two men may have had help from the staff on the inside. "I'd be shocked if a correction guard was involved in this, but they definitely had help,” he told NBC’s Today. “Otherwise, they couldn't have done this on their own."

Martin Horn, the former commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction, gave support to the idea of some broader conspiracy, telling the Canadian Press that the prison keeps a strict inventory of "every pair of scissors, every wrench, every power tool.” The prison also boasts some 1,400 guards for an inmate population of just under 3,000.

On Monday, the New York Post reported that a female prison worker had been interrogated and was thought to be a possible accomplice in the escape. The woman was not thought to be a guard and has since been removed from her post. Meanwhile, the bloodhounds are still out.

The Most Horrifying Game of Thrones Death Yet

Spencer Kornhaber, Christopher Orr, and Amy Sullivan discuss the latest episode of Game of Thrones.

Orr:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

George R. R. Martin has said that Robert Frost’s brief, Dante-inspired poem in turn provided inspiration for A Song of Ice and Fire, and never has this lineage been half as evident as over the past two episodes of this season. Last week at Hardhome, we saw the chilling, remorseless hate of the Night’s King; this week, we watched the burning desire of Stannis (resulting in arguably the most disturbing scene of the show to date) and, in a less awful fashion, that of Daenerys. A few scattered thoughts on other events in the episode before I come back to these two huge developments.

Related Story

Game of Thrones: The Only War That Matters

First, I know I’m a broken record on the subject of Ramsay Snow/Bolton, but why is it that every single storyline connected to him has to immediately become stupid? His dad, Roose, is an accomplished military commander, but it’s untrained, never-been-to-war-in-his-life Ramsay who leads the brilliant expedition in which a couple dozen men cripple an army of thousands.

“Twenty men rode into our camp without a single guard sounding the alarm?” Stannis asks, speaking on behalf of every single viewer of this latest ridiculous Ramsayism. Ser Davos offers the nonsense reply (which has been tediously set up in previous episodes by several Ramsay references to “we Northerners”), “The Northerners know more about their land than we ever will.” Such as how to ride horses into a guarded military camp, set dozens of fires, and leave before anyone notices? Utterly, utterly lame. (Also, Melisandre: Isn’t gazing into the flames supposed to show you what’s going to happen, rather than what happened a few minutes ago immediately outside your tent?) My predictions of a week and a half ago are looking pretty good except for the assumption that Ramsay would finally get his. The Bastard of Bolton’s ability to screw up even episodes in which he does not appear suggests, once again, that showrunners David Benioff and D. B. Weiss just can’t quit him.

While I’m griping, let me note that the Arya-is-going-to-kill-Ser-Meryn-Trant storyline, which has been pretty obvious ever since Cersei dispatched the latter to Braavos, just evolved from “Pleasant Nugget of Vengeance” to “Typically Overlong Benioff and Weiss Portrait of (Sexual) Villainy.” We already knew Meryn Trant was a bad guy. We didn’t need five minutes of his haggling for an underaged prostitute—“Too old,” “too old,” “too old,” “you’ll have a fresh one for me tomorrow”—to convince us that he deserved to die. He’s a third-tier baddie who should have shuffled off his mortal coil tonight. It’s a waste of precious time to extend his imminent, inevitable death into the season finale.

Up at the Wall, Jon Snow was visibly relieved that Ser Alliser, after some consideration, opened the gate for him and his Wildling refugees. Afterward, Alliser told Jon “You have a good heart,” which is—and was intended to be—about the most vicious insult one can lob in Westeros. Although even that was nothing compared to the death gaze Olly gave Jon in response to his smile.

The scenes in Dorne were ... not completely awful? Progress! Yes, we still had to watch the ever-pointless Sand Snakes play their slap games—“Are you going to cry?”—and Ellaria Sand’s ongoing treason went well beyond implausible. Let’s review: She’s Oberyn’s former paramour, who was just imprisoned for planning an uprising and trying to kill Princess Myrcella, the betrothed of the heir to Dorne. But she nonetheless got to attend the royal negotiation between Prince Doran, Jaime, Trystane, and Myrcella (sorry for trying to kill you!), and she seized the occasion to ostentatiously pour her Dornish red on the floor. Yes, she later kissed Doran’s ring. But seriously, dude: You needed to execute her. What’s that phrase? You have a good heart.

That said, I liked Ellaria’s subsequent scene with Jaime, in which she attempted a rapprochement by way of shared sexual complications. Her comment “We want who we want” was an almost direct echo of Jaime’s line to Brienne back in season three: “We don’t get to choose who we love.” (Let’s all agree to please not extend this ethos to Ser Meryn’s pubescent fetishism.)

But enough stalling: It’s time to work through my unhappy response to the horrible death of Princess Shireen Baratheon, an event that has not taken place—at least not yet—in the Martin novels. This made it a new experience for book readers in two overlapping ways: It was the first genuinely shocking death that we hadn’t already experienced on the page and, as a result, the first for which we didn't know whether to “blame” novelist Martin or showrunners Benioff and Weiss. In some ways, it was a clarifying moment—one in which we had to ask “Are we okay with this plot development?” without falling back on the easier question of “Can we complain because it diverged from the books?”

I’m honestly torn. I don't think any of the horrors that the show has offered up so far can compare with a father—one whom we’d clearly been groomed to like and identify with this season—cold-heartedly sentencing his daughter to an excruciating death for personal gain. The show had been hinting at this outcome for a while, of course. But up until the moment the pyre was lit, I genuinely didn’t believe it would go through with it.

Up until the moment the pyre was lit, I genuinely didn’t believe the show would go through with it.Another momentary digression from the awfulness of the scene itself: How exactly is this royal-blood-magic supposed to work? As the “scenes from previous episodes” reminded any forgetful viewers, a couple of seasons ago the leeching of a royal bastard (yes, after some This-Is-HBO fluffing) was enough to kill three presumptive kings. By that deadly recipe, shouldn’t a few hemoglobic drops from Shireen prove enough to take out a Warden of the North and his bastard son? But obviously, I didn’t major in R’hllor chemistry.

I’ll be curious to see how Shireen’s death sits with me in a day or two. For now, it was the first moment in which the relentlessly dark vision of the show—and in different ways, the books—felt as though it might be more bug than feature. I’m well aware that the world can be a terrible place. I don’t generally watch televised entertainment in order to be reminded of this fact. Or, as Tyrion neatly put it tonight, “There's always been more than enough death in the world for my taste. I can do without it in my leisure time.”

If there was a crucial mistake in this episode—and I think there was—it was to give us that horrifying Shireen sacrifice with almost half-an-hour still left in the episode. This was a scene that, however one responded to it, should have closed out the show.

Instead, we had the big set piece at Daznak’s Pit in Meereen, where gladiatorial combat turned into a nasty insurrection before turning into what Drogon calls “lunch.” Like Hardhome last episode, this was a Big Finale. (I’m fairly certain we’re due for yet another next week.) I had my quibbles here and there: e.g., enough with the third-rate double entendres, Daario Naharis 2.0. And seriously, Ser Jorah, it's time to get over Dany, preferably without having an intimate, slow-music moment with her (in the midst of a murderous uprising) that might pass on your notoriously contagious greyscale STD. And, his quote about death and entertainment notwithstanding, I can’t recall the show ever having made poorer use of Tyrion. That said, it was ultimately a big, terrifically executed finale (again: Drogon!), the second in two remarkably cinematic weeks.

But for me, the pyrotechnics were largely wasted. The episode essentially ended when Shireen was burned at the stake. Gladiators, Sons of the Harpy, a dragon buffet—nothing compared to a father’s decision to sacrifice his own daughter.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

I’m no longer sure which of Frost’s (and Martin’s) competing visions would be worse. And I’m not entirely certain I’m all that eager to witness it either way.

How about you two? Did this episode throw you as much as it did me?

Kornhaber: Whenever something like the death of Shireen happens—something so awful that even folks who don’t watch the show begin talking about it, usually by asking their shell-shocked friends, “Why the hell do you watch this stuff?—a few arguments get thrown around in Game of Thrones’ defense. The most common talking point says it’s silly to expect anything but brutality on a show that’s in large part about the causes and consequences of brutality. A kid got pushed out of a window in the very first episode of Thrones; did anyone expect Westeros to be a gentle fantasyland after that?

It’s both a valid and vile argument—at its core, a call for numbness. In a twisted way, it’s to the show’s credit that after five seasons of killing lovable people in awful ways, the audience can still experience deep shock and horror. Then again, that shock and horror comes by pretty crude means: ever-more-awful crimes against ever-more-lovable (and less deserving) victims. Lots of people have been burned alive on this show. Lots of people have been raped. But until this season, those fates had never befallen children who the audience had watched grow up for a few years, who’d become sympathetic in large part because of their innocence. (The closest analogue might be the faux-charring of Bran and Rickon in Season 2, a development that indeed almost made me quit watching before Theon’s duplicity was revealed.)

In fact, in the annals of popular storytelling, Shireen’s death has few precedents. Society basically only allows depictions of filicide when either parent or child has been invaded by evil spirit or illness. Even Darth Vader didn’t have the will to kill Luke, and even the God of the Old Testament didn’t make Abraham go through with the sacrifice of Isaac. So in the Thrones tradition of torching old tropes, it’s radical to have a character as generally sympathetic as Stannis kill his goodhearted daughter essentially in the name of political ambition. What’s more, she died in a manner so painful that the warrior king Mance Rayder was spared of it in the first episode of the season. It’s more than okay to be deeply disturbed.

Another defense of the show is a moral one, calling hypocrisy on anyone who mourns some atrocities more than others. D.B. Weiss trotted this one out when talking to EW about Shireen’s death: “If a superhero knocks over a building and there are 5,000 people in the building that we can presume are now dead, does it matter? Because they’re not people we know. But if one dog we like gets run over by a car, it’s the worst thing we’ve ever seen. I totally understand where that visceral reaction comes from. I have that same reaction. There’s also something shitty about that. So instead of saying, ‘How could you do this to somebody you know and care about?’ maybe when it’s happening to somebody we don’t know so well, maybe then it should hit us all a bit harder.”

Game of Thrones is not here to teach a lesson about caring for each life equally. If anything, the lesson is to care about none of them.This line of thinking can be useful and profound when talking about risk management, foreign policy, or giving to charity. But coming from the creator of a show in which the death of one little girl was carefully presented to have maximum emotional impact—the seasons-worth of reading lessons, the recent bonding between her and the father, those screams from the pyre—it’s galling misdirection. Game of Thrones is not here to teach a lesson about caring for each life equally. If anything, the lesson is to care about none of them.

All of that said, while Shireen's end filled me with disgust, I’m not ready to say it was reckless storytelling. In the post-episode HBO interview, the showrunners indicated that this death came on orders from George R.R. Martin and that it freaked them out as well, but that it makes sense in the universe of the show. Indeed, Stannis has been set up as someone who relishes making the hard and personally wounding choices. He believes that becoming king is not only his destiny, but something that has to happen for the good of the realm. And after Melisandre’s smoke baby, the leeches, and the failure at Blackwater, he has reason to believe in the power of fire magic. The final conversation between him and his daughter offered the finest acting yet from Stephen Dillane, who showed a mix of duty and despair via gravelly voice and sad eyes. Unfortunately, it was Kerry Danielle Ingram’s best scene to date as well. Shireen’s intelligence and attitude is so charming that you can’t help but yearn for her to live and join Arya and Tyrion in the “cripples, bastards, and broken things” Westerosi justice league.

But the most crucial moment of the whole Shireen sequence may have been after the deed was done, and Queen Selyse let out of a low, moaned “nooo.” Stannis’s response was a look of pure disorientation. All this time, his wife has been the lead fanatic of the marriage, and for her to lose her faith reminds him that he’s undertaken this heinous action on a gamble. The facial expressions on the soldiers watching the ceremony certainly indicated that this bonfire wasn't going to boost morale. If the Lord of Light doesn’t come through, Stannis is truly lost. Perhaps that would be justice.

The number of words I’ve spent on Shireen’s death indicates that you’re right, Chris, that it was a mistake for the episode not to end with it. The uprising in the Meereen fighting pits provided cool visuals but, maybe because of what came before, didn’t hit me with the momentous power I think it was meant to have. Perhaps the problem was that the dragon ex machina surprise was no surprise at all—as soon as trouble arose, I assumed a firebreather would bail the gang out. The only real twist of the sequence was that Hizdahr, the gladiatorial apologist who’d been suspiciously late to the ceremony, found himself on the wrong end of an insurgent’s dagger. The best action came before the real action, in the form of the ringside philosophical sparring between Tyrion, Hizdahr, and Daario. The show itself might want to take into consideration Tyrion’s brief for less violence:

Hizdahr: It's an unpleasant question, but what great thing has ever been accomplished without killing or cruelty?

Tyrion: It's easy to confuse “what is” with “what ought to be.” Especially when “what” is has worked in your favor.

I also agree, Chris, that the Meryn Trant storyline seems like it could have been initiated and wrapped up in this episode. The lengthy amount of time spent at the brothel mostly served to hint that Arya could be in sexual peril. With the show being so cruel to its young female characters lately, the last thing I want is any suspense about what’s going to happen if Arya tries to exact revenge while pretending to be a pedophile’s prostitute. Please, Benioff and Weiss, let her just serve him a stanky oyster and be done with it. (On the other hand, I wouldn’t mind a few more scenes of the buffoonish Mace Tyrell playing the Ugly Westerosi to the cosmopolitan calm of a Braavosi banker.)

Nine episodes in, and I still don’t get what’s up with Dorne. The scenes with Jaime were indeed better than they have been lately, but the entire situation comes across as nonsensical for all the reasons you’ve listed, Chris. Mostly, I feel a sense of squandered opportunity about the setting. Doran’s palace and the Water Gardens look, for lack of another word, dope. I know book readers say Martin got bogged down with this stuff, but I want to learn more about the tiling, the shrubbery, the wine! The political situation seems so transparent—a ruler too lenient and merciful for his own good—that I’m hoping there’s a conspiracy afoot with Doran installing Trystane on the small council. And I can’t tell whether Ellaria Sand’s sudden kindness toward a Lannister is a performance, or just another example of the tempestuousness of the Dornish.

Sullivan: If forced to choose, I’d take the insult of having a good heart any day, despite the uncertainty and second-guessing that usually accompany it. It takes a fanatic to burn people alive—but a fanatic at least is completely confident, if often misguided. To burn a little girl alive when you’re unsure, when you’re playing at being confident for reasons of faith or ambition or “leadership,” is something else entirely. It’s evil.

Queen Selyse found her faith tested by the excruciating blood sacrifice of her daughter (so she does have a heart, after all). Stannis, after appearing to stand with Cersei for just a few episodes in placing love and protection of his child above all else, gives up Shireen to Melisandre because he’s too freaking proud to retreat to Castle Black. And Melisandre herself was recently flirting with Jon Snow and his much-speculated royal blood. Surely they all would have tried to exhaust every other possible option before killing a child, right? Right?

At least Queen Selyse forced herself to watch Shireen’s fiery death. Like you, Spencer, I’m torn about violence in—not as—entertainment. We may not live in a world as medieval as Tyrion’s, but I can agree with him when he says, “There’s always been more than enough death in the world for my taste. I can do without it in my leisure time.”

But in our first-world lives, we rarely have to witness unsavory consequences, whether of something like hoarding life-saving medications for ourselves, or sending others off to war for us. This past year has taught many of us that the story we told ourselves of our race-blind criminal justice system was believable only because we didn’t have to watch black men being shot in the back by police.

Before we even got to the wrenching scene of Shireen’s death, I was struck by the way the camera actually lingered on the line of soldiers waiting for their meager helping of horse stew. Those men aren’t Stannis’s blood brothers, who proudly signed up for this fight. They have no choice. They’re exhausted, they’re freezing, they’re starving, and they’re going to die.

What if Dany is just another high-born with delusions of grandeur who was content to let the deaths of others be the price?They’re not so different from the pit fighters who declare they will live or die for the queen but in reality have little choice. Or the spectators who were slaughtered by the Sons of the Harpy. Or, for that matter, the Sons of the Harpy who were burnt to a crisp by Drogon. We’re supposed to feel relief for Dany, who lives to rise into the clouds on her dragon offspring and fulfill her destiny. But what if we’re wrong? What if she’s just another high-born with delusions of grandeur who was content to let the deaths of others be the price?

Give me Jon Snow instead, who cut off Janos’ head earlier this season in a rare instance of trying to please a father figure—this time, Stannis—but who at least had the decency to look disgusted with himself. Jon, who looked shattered this episode, not just because of the terrifying enemy he encountered at Hardhome but because of the scale of death the Wildlings suffered. Pollyanna Sam tries to buck him up by pointing him to the very real people who are alive because of Jon’s actions, but Jon can only see the very real faces of those who didn’t make it. Is a leader someone who sees each of those faces or someone who can block them out to concentrate on the larger goal? You have a good heart, Jon Snow.

Elsewhere, my notes on the Braavosi scenes simply read: “DO NOT DO THIS TO ARYA.” Okay, that’s not entirely true. There’s one other word: “Mycroft!” But by the penultimate episode of the season, this Braavos storyline should be able to do more than make me want to re-watch old Sherlock episodes. It’s been an improvement on the interminable House of Black and White plot in the books, but that is a very low bar.

And then there’s Dorne, which at this point I’m convinced has just been an excuse to keep fan favorites Jaime and Bronn involved this season. Is The Dornish Mis-Adventure a buddy comedy? A family sitcom? (Jaime’s critiquing Myrcella’s clothing choices now—heads up, girl, he must be your dad.) Why are the Sand Snakes so crazy? Why does their mom whipsaw between cartoon villain and relatively normal schemer? And she has a fourth daughter—what?

Actually, forget it. I don’t have time to care about the answers to any of those questions. The season finale is one week away, and I need to finish making my Ramsay voodoo doll.

The Brief and Tragic Life of Kalief Browder

We are in the midst of a debate around criminal justice right now, a timid one no doubt, but a debate nonetheless. In the midst of such debates it is customary for pundits, politicians, and writers like me to sally forth with numbers to demonstrate the breadth and width of the great American carceral state. The numbers are, indeed, bracing and are not hard to find. The fact that African Americans comprise some one in 200 of all known people in the world, and yet African American men comprise one in 12 of all known prisoners has always given me pause.