Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 417

June 11, 2015

The New True Crime

In the summer of 1841, police found the body of Mary Cecelia Rogers floating in the Hudson River. The authorities had their theories: Rogers might have been the victim of a well-known local abortionist, a gang, or an accident. But all they knew for sure was that she was around 20 years old, had worked in a New York City tobacco shop and had been gorgeous. Hence the nickname the media gave her: “The Beautiful Cigar Girl.” Her case remains officially unsolved, but at the time it drew national attention and inspired the writer Edgar Allan Poe to do some investigating of his own. He later claimed he had untangled the riddle of her death and wrote a story called The Mystery of Marie Roget, which gave the real case a thin Parisian sheen (Marie Roget’s body was found in the Seine, etc.). A true crime prototype, Marie Roget featured many of the hallmarks the genre retains to this day: the thrill of amateur sleuthing, the female victim, the gruesome and vivid descriptions.

Related Story

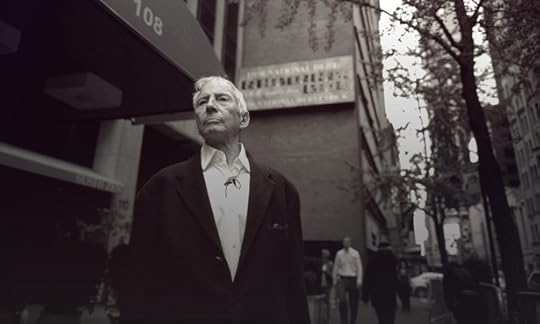

As Robert Durst Is Arrested, The Jinx Finale Takes Viewers on a Thrill Ride

Since that time, true crime has mostly been dismissed as tabloid fodder, with a few exceptions—most notably, Truman Capote’s 1966 In Cold Blood, which showed that the genre could be a real literary form. Recently, though, true crime has taken on new visibility. First came Serial, the 2014 This American Life spinoff, which revisited the investigation of the 1999 killing of the Baltimore teenager Hae Min Lee, and the conviction of her boyfriend, Adnan Syed. That series spawned the legal-analysis podcast Undisclosed, focusing on the same case, which debuted in mid-April as iTunes’s most-downloaded podcast and has since settled into the #14 spot. In film, Bennett Miller’s Oscar-nominated Foxcatcher explored the life of the philanthropist and murderer John du Pont. On television, HBO aired the six-part docuseries The Jinx earlier this year, focusing on the suspected murderer Robert Durst. The Weinstein Company recently bought the rights to turn In Cold Blood into a miniseries. And American Crime Story, an upcoming FX series, will tackle the O.J. Simpson trial when it debuts in 2016.

Although true crime has found new ways to appeal to mainstream audiences in the 21st century, in many ways, the genre hasn’t changed much since the days of Poe or Capote, as evidenced by the surface similarities between Marie Roget and Serial. But in other, deeper ways, it has. New forces—improved technology, new media, and less trust in institutions—have helped shape true crime into a truly modern form. Social media helped turn The Jinx and Serial into participatory experiences, while also contributing to their widespread exposure. The average American today has greater familiarity with the legal process, thanks in part to procedurals dramas and the round-the-clock media coverage of splashy crimes that began with the O.J. Simpson trial in the 1990s. And people are more aware than ever of flaws in the criminal-justice system, including police brutality and wrongful convictions. The result is a genre that’s still indebted to decades-old conventions, but also one that has found renewed relevance and won a new generation of fans by going beyond the usual grisly sensationalism.

***

Twitter isn’t lighting up anymore with speculations of “Did Jay do it?” or declarations for “#TeamAdnan.” But Serial, which concluded in December 2014, sparked a series of events, most recently last month’s news that Syed might be able to offer new evidence in his appeal for a shorter sentence. The series didn’t offer the kind of triumphant, seemingly straightforward conclusion The Jinx did (an apparent hot-mic confession by Durst and a timely real-life arrest), but it’s unlikely Syed’s case would have progressed in such a meaningful way without Koenig’s podcast and the influence it generated. And in filing a motion June 4 to suppress evidence obtained during Durst’s arrest, defense lawyers claimed that as millions of viewers prepared for The Jinx’s finale, “[Police] were hurriedly planning to arrest Durst before the final episode” to capitalize on the hype, and “were crafting a dramatic moment of their own.”

Social media supports the quick ascendance of particular stories, allowing a grassroots energy to buoy otherwise niche cases to the top of the trending list. Ironically, in this environment, lesser-known stories can often have a longer shelf life than headline news reports. “It’s for this same reason that lesser-known stories and cold cases [without] an online or verifiable footprint really resonate with people,” said Michael Arntfield, a former police officer and professor of criminology at Western University in Ontario.

When a story is being covered on every media outlet (including Twitter), it becomes part of the accelerated news cycle, which pulls stories down as quickly as it props them up. But when the only source of information is a credible report by a captivating storyteller like Koenig, a case tends to hold people’s attention much longer. Platforms like Twitter and Reddit have also made it easier for people to publicly fact check stories and call out inaccuracies. This added level of engagement can be frustrating for storytellers, but it can also translate into a greater investment in the story—and its outcome.

As a result, Arntfield said he believes audiences are more likely to see the same stories—the popular ones—being retold more frequently. The Intercept ran its own multiple-installment interviews with Serial’s elusive character Jay, followed later by the launch of Undisclosed, which explores the case from a different point of view. Even the decades-old Charles Manson case is inspiring fresh takes. Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders has remained the #1 bestselling true-crime book since its publication in 1974. The acclaimed podcast You Must Remember This, which focuses on stories of 20th-century Hollywood, will spend its second season focusing on Manson’s “life, crimes, and cultural reverberations.” (The third episode aired Tuesday.) The new NBC show Aquarius, which debuted in late May, features a Manson-centered plot and a shameless tagline: “Murder. Madness. Manson.”

The rapid turnover of crime stories isn’t necessarily unique to the 21st century. In the early 1900s, American tabloids were filled with grisly tales of triple slayings, decapitations, and executions that would be forgotten weeks later. And while the sensationalism surrounding true crime hasn’t diminished today, audiences are better equipped to parse the technical details of different cases. David Schmid, an English professor at the University of Buffalo and an expert on crime in U.S. popular culture, pointed to the Simpson trial as a flashpoint for this change. “The line that was crossed with that case was that it gave the general public a level of familiarity with the legal process they didn’t possess before,” he said.

This skepticism and distrust of the criminal-justice system can be a selling point for stories that promise to probe the blurry edges of the law.The reality channel CourtTV, which launched in 1991, found immense popularity during this time with its criminal justice-oriented programming and nonstop coverage of courtroom drama. (The channel covered the infamous trial of Lyle and Erik Menendez, convicted of killing their parents in 1994.) Legal and police procedural shows, especially the Law and Order franchise, similarly flooded the public consciousness. Though not exactly true crime, Law and Order became known for its ripped-from-the-headlines episodes that often featured easily recognizable elements from real-life cases (à la Marie Roget).

This greater legal awareness has given storytellers the chance to embark on ever-more sophisticated true-crime stories. “Serial goes into the ins and outs of the legal process to a great degree and is produced for an audience that is fairly knowledgeable about what constitutes legal evidence and trial procedure,” said Schmid. In fact, he added, “Perceived knowledge of the legal process is one of the preconditions for the success of something like Serial.”

Related Story

The Grisly, All-American Appeal of Serial Killers

Yet another precondition is the feeling shared by many Americans that the legal system is broken. (Schmid described Serial in particular as a “symposium” on whether justice in the U.S. is possible.) As of last June, 76 percent of Americans had some, little, or no confidence in the criminal-justice system, according to a Gallup poll. Pamela Colloff, a veteran crime reporter and executive editor at Texas Monthly, told me, “There’s been an incredible shift in public consciousness about wrongful convictions and the possibility that someone who’s in prison is innocent.” This is in addition to public anger over recent police killings of unarmed African American men. Skepticism and distrust of the current state of law and order can be a selling point for stories that promise to probe the dark, blurry edges of the law.

“It would be interesting to see whether there’s a possibility of some kind of synergy developing between creative writers and producers of shows and [organizations like] the Innocence Project,” Schmid said. It’s an intriguing prospect: a kind of vertical integration between advocacy groups—with their considerable resources and arsenal of information—and editorial teams equipped to turn that raw data into fascinating stories.

But that would of course intensify a question that creators already face: What kinds of cases should producers, podcasters, authors, networks, and journalists ultimately choose to pursue? The coldest cases? The most baffling verdicts? The goriest crime scenes? The most sympathetic victims? The handsomest killers? Or the worthiest causes?

***

In its purest form, true crime doesn’t shy away from the gratuitousness that’s always been part of the genre. “I’m all for sensationalism—it satisfies a certain kind of primal appetite,” said Harold Schechter, a professor of literature at Queens College-CUNY and a serial-killer expert who’s written more than 30 crime books. While much has been made of the violence depicted in popular culture, Schechter sees it as a good thing, even a sign of social progress. “Not long ago,” he said, “humans demanded to see actual executions and humans being tortured.”

In 17th century New England, large groups of people would gather to hear preachers give an execution sermon before a criminal was put to death. In more recent history, lynchings of blacks in the American South often drew celebratory crowds. But now, most people are content to witness violence in virtual form, via TV and movies. And despite their voyeuristic elements, crime stories haven’t always been first and foremost about titillating audiences. Poe’s story about Mary Rogers functioned as a critique of law enforcement’s ineffective investigation of her death.

In order to craft a compelling narrative, most true-crime authors rely on certain conventions. Some of these are obvious and grotesque, such as opening a story with a graphic description of a violent crime. Other are subtler, like framing a case so certain facts are left out, or omitted until later.

A sense of balance is key. Telling a story about a miscarriage of justice sometimes requires devices that might be seen as pulpy. “But the line is, you don’t want to go into lurid,” said Colloff, whose whose wrongful conviction stories have been nominated five times for National Magazine Awards (her two-part feature The Innocent Man won the award for Feature Writing in 2013). “There are gradations of what kinds of storytelling is done in true crime. Some of it is tasteful and some of it isn’t. I think there were times in Serial when Koenig walked right up to the line.” Koenig has been criticized for not focusing enough on the victim, Lee, and for dangling the possibility that Adnan’s friend, Jay, might have been more involved than he let on. (My colleague Adrienne LaFrance delved deeper into the ethical questions surrounding being “hooked” on the podcast.)

The public’s appetites also help determine which cases journalists, filmmakers, and writers choose to explore in the first place. “I’m very deliberately picking the one that has the most compelling narrative arcs, the most compelling people, as vehicles for telling the larger story of problems in the criminal-justice system,” Colloff said. The story archetypes that intrigue readers most are unsolved mysteries, serial-killer cases, or Jack the Ripper–style tales involving beautiful female victims (especially when their bodies are found in bleak places). Despite the public outrage about Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Jordan Davis, when was the last time the victim in a true-crime story was a young, unarmed black man?

When was the last time the victim in a true-crime story was a young, unarmed black man?“Serial and other narratives aren’t doing enough to challenge what ‘mediagenic’ means,” said Schmid. The result is story after story “replicating that same set of assumptions about what it takes to constitute an interesting crime narrative.” Even stories looking to make broader social statements often end up borrowing from this narrow set of tropes. For example, the HBO’s documentary Tales of the Grim Sleeper takes an unsettling look at the complex intersection of race and crime but focuses on an alleged serial killer in South Central Los Angeles whose victims were almost all female.

One project that appears to deviate from this formula a bit is the podcast Criminal, which launched in January 2014 and tells short yet nuanced stories of people involved in some way with crime. For another counterexample, Schmid pointed to The Los Angeles Times’ Homicide Report, which challenges the popular notions of what kinds of crimes matter by assiduously documenting every single homicide in the city. The project’s tagline? “A Story for Every Victim.”

And most of them aren’t beautiful young women.

***

These long-percolating cultural shifts hint at what true crime’s future could look like: less straight entertainment and more advocacy journalism, if not in style, then at least in consequence. Months after the final episode of Serial ended, Syed’s case continues to see new developments, and Durst continues to sit in jail, waiting for a trial that could end with him facing the death penalty for the murder of his friend. True crime may, in the coming decades, further challenge which kinds of victims deserve sympathy and which kinds of crimes should provoke outrage and disgust.

In the past, Schecter said his readers would come up to him after his book events, and tell them how abashed they felt about being fans of true crime. Compare that to the unabashed attention surrounding the likes of Foxcatcher, The Jinx, Serial, and Undisclosed (maybe not so much Lifetime’s recently wrapped, campy series Chronicles of Lizzi Borden starring Cristina Ricci).

None of the experts I spoke with thought this increased attention would fundamentally change the basic elements of true-crime stories. But most agreed that current media forms have given the genre distinctly modern characteristics. Imagine if Twitter had existed at the time the Clutter family had been killed—or conversely, if Facebook hadn’t existed when the story of Hae Min Lee’s murder ended up on Koenig’s desk. Or think of a subreddit obsessively poring over details of Mary Rogers’ death the way Poe did in the 19th century, desperate to find the one clue that would explain everything.

June 10, 2015

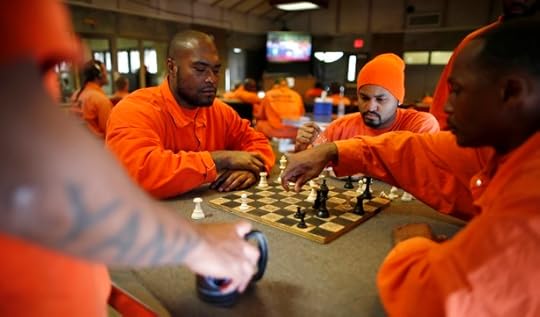

How Prisons Kick Inmates Off Facebook

It takes a little bit of work to get off Facebook. To suspend your profile, you have to walk through some settings pages and submit a form explaining why you’re de-activating. And if you want to permanently delete a profile, you have to submit a different form, then wait several days.

But for at least four years, the Facebook accounts of incarcerated Americans had a fast track to suspension.

Since at least 2011, prison officials who wanted to suspend an inmate’s profile could submit a request to Facebook through its “Inmate Account Takedown Request” page. The company would then suspend the account—immediately, often with “no questions asked,” reports Dave Maass, an investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), who first wrote about the page.

This relationship could get cozier than a web form, too. In an email correspondence first published by the EFF, a California corrections officer asked a Facebook employee to “please remove these [attached] profiles” of currently incarcerated inmates.

“Thank you for providing me with this information. I apologize for the delay in getting these profiles taken down,” a Facebook employee replied. “I have located and removed all five accounts from the site. I apologize again!”

This fast-and-loose suspension regime has now changed. Or, at least it appears that way: Last week, Facebook announced measures that will create a higher threshold for removing inmates’ accounts. The company now requests much more information from corrections officers about an inmate’s account, and it also requires officers to demonstrate that inmates have violated law or prison policy in the first place. This was never something it asked about in its previous form.This is a big change. As Maass points out, suspending an inmate’s account is a kind of state censorship: A government agency asks Facebook, “hey, can you make this speech go away?” and Facebook says “sure,” without seeing if the inmate was threatening someone or otherwise violating its terms of service. A Facebook spokesman said questions about its role in what critics say is censorship would be better posed to lawmakers.

Facebook provides data about censorship requests (it calls them “content restriction requests”) for many countries, including Brazil, Germany, and the United Kingdom. But while it provides some information about U.S. national security requests, it does not disclose how many American “content restriction requests” it receives. A Facebook spokesman declined to provide statistics about how many profiles were suspended to The Atlantic. So we’re left with estimates: The EFF found that in two states alone (California and South Carolina) the combined number of suspended accounts exceeded 700.This change doesn’t mean either that inmates can now have a Facebook profile in every state. Louisiana, for instance, prohibits prisoners from maintaining an account, and Alabama forbids inmates specifically from having a profile operated by a proxy user (like a friend or family member).

States can be harsh with their punishments. South Carolina treats “one day of operating a Facebook account” as a “level-one offense,” a crime on par with murdering or raping a fellow inmate. That’s how a South Carolinian prisoner—who used a Facebook account for 37 days—was sentenced to 37 years of solitary confinement earlier this year. It’s unclear whether he will serve out the term.

Facebook, of course, is not the only website that American inmates use. (Earlier this year, a Fusion investigation into technology and prisons discovered an anonymous inmate’s Vine account, evidently operated from a contraband smartphone. The account has now been removed.) But Maass said Facebook is the website that correction officers fixate on.

“Of the hundreds of cases I’ve reviewed, all but three involved Facebook,” he told me. “Prisons don’t seem to be going after any site other than Facebook. That’s what they see inmates on, and that’s what they know how to use.”

It wasn’t always this way. Back in 2006, he said, Myspace was the social network of choice for both inmates and corrections officials. “It had just taken over, it was the most visited site on the Internet,” Maass said.

There was a campaign in Texas to take down the pages of prisoners on death row. This was before the rise of smartphones, so inmates operated their pages through a proxy family member or friend, with whom they communicated by letter. Myspace stood firm that inmates shouldn’t lose their accounts just because they were inmates.

“Unless you violate the terms of service or break the law, we don't step in the middle of free expression,” a Myspace spokesman told USA Today at the time. “There's a lot on our site we don’t approve of in terms of taste or ideas, but it's not our role to be censors.”

Mosul Under ISIS: Clean Streets and Horror

On Wednesday, the United States announced that it would send up to 450 additional troops to Iraq to train Iraqi fighters as they aim to retake the city of Ramadi from ISIS.

The timing was eerie. It was almost exactly a year ago that ISIS achieved its shocking takeover Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city. And just two months ago, Iraqi fighters scored their biggest success yet in the fight to take it back, when they defeated ISIS in Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s hometown, which lies on the highway to Mosul. But as ISIS held on to that key city in Iraq’s north, it was also gaining territory in the west, and in mid-May the group swept in and took over Ramadi, the capital city of Iraq’s largest province.

The new deployment of U.S. troops is part of an anti-ISIS strategy that, to borrow Obama’s word, is not yet “complete.”

The picture of life in Mosul after a year of Islamic State rule is similarly uncertain. Accounts from the city give a (very) surprisingly textured portrait.

“Theft is punished by amputating a hand, adultery by men by throwing the offender from a high building, and adultery by women by stoning to death,” one resident told the BBC. “The punishments are carried out in public to intimidate people, who are often forced to watch.”

The report also noted the destruction of mosques, the conversion of churches, and harsh implementation of strict Shariah law, under which women are forced to cover up head-to-toe (including gloves), and which includes floggings for small infractions like smoking cigarettes. A widowed mother of four told The Guardian she had had her hand chopped off for stealing.

Another Mosul resident declared himself a slightly ambivalent supporter and praised some of the group’s ability to impose order and provide public services. “Isis with all its brutality is more honest and merciful than the Shia government in Baghdad and its militias,” he said. Another resident told The Wall Street Journal, “I have not in 30 years seen Mosul this clean, its streets and markets this orderly.”

The admixture of strict rule, terror, and the creation of infrastructure has been a hallmark of ISIS governance elsewhere in its domain. It’s a model that will be exceedingly difficult to dislodge.

The Fitful Journey Toward Police Accountability

For almost a year, the nation has been focused on cases of violence against citizens by police—most of them involving black victims, and many of them involving white officers. A complaint that advocates have raised again and again is that there’s too little accountability for officers: They’re seldom prosecuted or punished when people die, and when they are prosecuted, they usually aren’t convicted.

That makes this an interesting moment, because across the nation this week, steps are being taken to hold officers accountable—whether through official reviews, the legal process, or citizen action. Here are a few of the stories swirling on Wednesday:

McKinney: In McKinney, Texas, Corporal Eric Casebolt resigned Tuesday afternoon. Casebolt was the officer captured on camera pulling a gun and tackling a black teenage girl at a pool party in the Dallas suburb. While Casebolt’s resignation—a two-word statement, “I resign,” with no apology—was described as voluntary, Police Chief Greg Conley also made clear that he did not approve of Casebolt’s actions, calling them “indefensible.” Casebolt’s attorney, Jane Bishkin, is expected to hold a press conference on Wednesday, though the timing is not yet clear. (A call to her office has not yet been returned.) Bishkin is experienced at handling cases involving police, and has represented unions and individuals. Cleveland: Community leaders are awaiting a decision from a judge on a criminal complaint they filed in Cleveland Municipal Court, seeking arrests for the two officers involved in the November shooting death of 12-year-old Tamir Rice. As I explained Tuesday, that comes under a little-known and less-used Ohio law that allows citizens to request an arrest warrant from a court. Michael Benza, an instructor at Case Western Reserve Law School, believed that a warrant was likely and could come quickly. Los Angeles: An investigation found fault with two officers involved in the August death of Ezell Ford, a 25-year-old, mentally ill black man shot at his home while he was unarmed. A civilian oversight commission “found that both officers acted improperly when they drew their guns, and that one officer also acted improperly in both approaching Mr. Ford and using his gun.” The case now goes to Police Chief Charlie Beck to decide whether to take any action against the officers. Ford’s mother welcomed the commission’s decision but was dubious that Beck—who had previously cleared the officers—would take serious action. She also called for prosecution of the officers. New York: The FBI announced arrests of two New York City corrections officers in connection with the 2012 death of a Rikers Island inmate. Ronald Spear, 52, was restrained when officers attacked him, with one reportedly repeatedly kicking him in the head. The two guards were charged with conspiracy, filing a false report, and lying to a grand jury. The city agreed to pay $2.75 million to settle a suit over his death last year.Meanwhile, a different sort of vision of accountability: Following up on a project launched by The Guardian that seeks to record every police-involved fatality—a response to the fact that no government authority keeps reliable statistics—The Intercept’s Josh Begley has created a collection of Google Maps images of the locations of fatal encounters. It’s an unsettling journey through haunted corners of the American landscape.

The Simpsons Are Separating: A Rant

D’oh! And also hmm: The Simpsons, it seems, are separating.

In an interview with Variety this week, show-runner Al Jean reveals that, in this fall’s premiere of the The Simpsons’ 27th season,

it’s discovered after all the years Homer has narcolepsy and it’s an incredible strain on the marriage. Homer and Marge legally separate, and Homer falls in love with his pharmacist, who’s voiced by Lena Dunham.

This isn't the first time, to be sure, that the Simpsons have faced marital difficulties. The threat of divorce has long loomed over Springfield's bluest-haired and baldest-headed couple, the threat usually caused by something dumb and/or comically inconsiderate that Homer did. (There was also the episode in Season 20 that revealed that, because of a clerical error, the couple had been legally divorced since Season 8.)

But Homer and Marge have persevered, together, both in spite and because of the key fact of their marriage: The Simpson union features a clear reacher … and a clear settler.

How I Met Your Mother laid out the basic dynamics of the reacher/settler theory: In every relationship, the idea goes, there's a reacher and there's a settler. The roles are fairly self-explanatory—the reacher has gotten someone out of his or her league; the settler has, indeed, settled. Which isn’t to say that a reaching/settling couple don’t both love each other or get something equally fulfilling out of their relationship; it is to say, though, that according to traditional and occasionally superficial romantic criteria—looks, smarts, charm, whatever else you want to throw in there—couples will rarely be evenly matched. One will go up; the other will go down.

So. In the long-running union of Marjorie Bouvier Simpson (beautiful, smart, kind, patient, a good mother and a beloved daughter from a country club family) and Homer J. Simpson (unhealthy, possibly alcoholic, hot-tempered, not terribly smart or industrious or successful as a worker or a father), the reach/settle dynamics are obvious. So much so that they are one of The Simpsons’ longest-running jokes. He's a loser! Why is she with him? Questions like that, punctuated by examples of Homer’s terribleness and Marge’s long-sufferingness, have been a well of humor for Simpsons writers throughout 26 seasons of the show.

Which all makes the legal-separation plot line Jean describes … actually kind of infuriating. The arc, basically, is this: The couple separates. Homer falls in love with someone else. The reacher reaches away from the person who has settled for him. Marge’s long-sufferingness is now, ostensibly, even longer and more suffer-y.

Am I over-thinking the dynamics of a marital union whose bonds have been entered into by four-fingered cartoons who never age? Oh, totally. But also! The Simpson marriage is, after all, the longest-running fictional marriage on television. It has been, in its weird, static way, a source of stability for audiences across seasons and years and even generations.

And the Simpson marriage has existed, maybe more importantly, within a television environment that has also aired shows like The King of Queens and Family Guy and Modern Family and Two and a Half Men—shows that ask their audiences to blithely accept marriages and relationships in which women, by pretty much every observable measure, have settled for men. These shows don’t suggest, as The Simpsons has, that there’s humor in the reach/settle divide; they suggest instead something more pernicious: that the divide is completely unremarkable. That a woman settling is just The Way Things Are.

But now, with this latest plot line? The Simpsons, too, is buying into that tired old assumption. One of the most consistently innovative shows is going retrograde. In the Marge/Homer separation, it is Homer who falls for someone else. It is Homer who gets someone else to settle for him. While Marge—smart, beautiful, caring, patient, long-suffering Marge—is left alone.

The Complicated Legacy of Batman Begins

Ten years ago, the idea of Batman actually scaring people was far-fetched. So when Christopher Nolan's Batman Begins was released in 2005, one of its biggest achievements was revitalizing the Caped Crusader as a dark icon of intimidation: snarling at Gotham’s underbelly while using fear (a major theme in the movie) to fight crime. Gone was the cartoonish, nipple-suited hero of the 90s; here, instead, was a tortured, flawed champion whose emotional depth grounded his exploits in a more realistic and recognizable universe. It was a revolution.

Related Story

The Batmanization of Bond Movies

But pop culture's memory is short, and the sight of Ben Affleck growling through his Batsuit in the trailer for Batman vs. Superman earlier this year provoked waves of online derision. Here was the real-world grit and psychological complexity of Nolan’s Batman, only dialed to a thousand. If once Batman had been too silly, now he was too serious. And this is the complicated legacy of Batman Begins: Nolan’s film allowed that superhero franchises could exist with one foot in the real world, and inspired legions of imitators to do the same. Some, like the James Bond franchise rebooted around Daniel Craig, followed that thread beautifully. But others seemed to assume that it was a cynical sense of bleakness that made Batman Begins special. The reality, as it turns out, is much more complex, and much more indebted to Nolan’s unique vision.

Warner Brothers is currently preparing a huge slate of similar comic-book adaptations along Nolanesque lines, but trying to emulate Batman Begins' success just by adopting its darker mood won’t work. So much of what makes the movie unique is Nolan himself, and his meticulous attention to detail. His Gotham is a relatable urban landscape (shot in New York and Chicago) with lurid flourishes like the run-down “Narrows” district, an island in the center of town bustling with the city’s poorest citizens. His Batman can grapple and glide around the city, but every gadget is parsed out to the audience and given real-world practicality. His Batmobile isn’t an improbable, gadget-laden sports car but a brutish tank originally designed for the military.

Batman Begins was able to justify such detail because it didn’t have to worry about the future—Warner Bros.’s intention wasn’t to plan out a series of sequels and spinoffs, but to re-invest audiences in a brand that had gone awry, giving Nolan the chance to re-create the character from the ground up. It takes an hour of runtime before Bruce Wayne puts on the suit and declares himself Batman, and in that hour, Nolan has him train with ninjas, deal with the trauma of his parents’ death, and cautiously explore a Gotham overrun by organized crime.

When Nolan was hired in 2003 to create a new Batman film, it was six years after the failure of Batman & Robin (the fourth entry in a franchise started by Tim Burton's 1989 Batman), and Nolan didn’t yet have an established reputation, let alone global acclaim as a wide-screen IMAX camera-toting dream-weaver. His biggest film at that point was the mid-sized cop drama Insomnia, and his indie reputation rested square on the shoulders of the brilliant, twisty neo-noir film Memento. Warner Bros. picking Nolan to revitalize Batman was hailed as a risky gambit, and it succeeded largely because the director was granted free rein to create a world free of franchise possibilities or other heroes lurking on the sidelines. His Batman was a bizarre apparition in a recognizably human world of cops and gangsters who’d never contended with a masked hero before. As simple as that sounds, there may never be a superhero film created along those lines again.

Nolan’s Batman was a bizarre apparition in a recognizably human world that had never contended with a masked hero before.Nolan subtly signaled these decisions to dedicated comic-book fans throughout the film, most notably in his slight alteration of Bruce Wayne's creation myth. Batman is still a scion of Gotham's wealthiest family who witnesses his parents' murder; but while the comics often portrayed the Waynes leaving a screening of a Zorro film, Nolan wanted his Bruce to be completely new to the idea of masked vigilantism. "We wanted nothing that would undermine the idea that Bruce came up with this crazy plan of putting on a mask all by himself," he told the Los Angeles Times in 2008. "That allowed us to treat it on our own terms. So we replaced the Zorro idea with the bats to cement that idea of fear and symbolism."

In Batman Begins, Bruce flees an opera that features dancers masquerading as bats, which frighten him. The concept of Batman as a symbol of fear is shot through the whole movie—Nolan (who scripted the film with David S. Goyer) works hard to have the audience understand why Wayne might be drawn to the bizarre idea of dressing as a giant bat to intimidate Gotham's criminals, drawing inspiration from the theatrics of the ninja who train him and the creatures that haunt the caves below his family mansion. Most comic-book films assume the audience will roll with the hero donning a colorful uniform because it's such recognizable imagery, but Batman Begins wants the first appearance of the Batsuit to feel genuinely shocking to both Gotham’s criminals and the audience.

Not all of this thinking originated with Nolan. A Batman film centered around intimidation had been in the works years before he came on board: Before the 1997 release of Batman & Robin, its director Joel Schumacher was already at work on the next entry, tentatively titled Batman Triumphant, which featured the fearmongering Scarecrow as the villain. That element bounced through several undeveloped Batman concepts before making it into the Begins script. Cillian Murphy plays Nolan's take on Dr. Jonathan Crane, a psychiatrist who poisons his patients with a fear toxin and controls them through the monstrous avatar of "Scarecrow." While the primary villains in the film are the League of Shadows, evil vigilantes led by Ra's Al Ghul (Liam Neeson), Crane's fear toxin is their weapon of choice, and a simple and effective way for Nolan to demonstrate Batman's terrifying status among the gangsters he's trying to wipe out.

Nolan's Batman ended his journey with The Dark Knight Rises and will never return to the big screen.Bale's performance goes a long way towards making this super-serious, super-scary Batman relatable. He doesn't deploy the cartoonishly gravelly voice he adopted for 2008 sequel The Dark Knight, which inspired a thousand parody videos, but nor does he lean into the idea that Bruce Wayne might just be a lunatic, which is the angle Michael Keaton (very successfully) worked in his two Tim Burton-directed Batman films. Bale's Bruce is barely clinging to his humanity, and is still haunted and driven by the death of his parents. But he's not liberated when he puts on the suit—above all, he's giving a performance, typified by his brutal interrogation of the corrupt Detective Flass, where Batman roars questions in his face while dangling him upside down by his feet. For Nolan's Batman, this is a means to an end, rather than a pure state of being. That theme recurs through his two sequels—The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises—which end in Batman’s retirement, seen as a necessary step for Bruce Wayne to live a normal, human life.

After the completion of his Dark Knight trilogy, Nolan was asked to help set the tone for a new slate of Warner Bros. films inspired by the DC Comics universe. That decision makes sense, but it feels somewhat curious when you consider that Nolan's Batman ended his journey with The Dark Knight Rises and very definitively will never return to the big screen. After Marvel Studios' first film— Iron Man (released in 2008)—ended with a post-credits teaser mentioning Nick Fury and the Avengers, the interconnected universe became en vogue, and once Nolan's films ran their course, Warner Bros. needed a new slew of heroes to keep up. Nolan and his Batman Begins co-scripter Goyer wrote the story to Man of Steel, a Superman reboot planned as a franchise-starter, then hired Zack Snyder to direct. Snyder is now firmly at the helm of the series Man of Steel launched, but Nolan is an executive producer on its sequel Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice and reportedly had a hand in the hiring of Ben Affleck as the big screen's newest Batman.

It's hard to say how much of Batman Begins' aesthetic has carried over to these new films, since they’re so dominated by Snyder's heightened, muddy visual palette (Nolan has always favored a crisper look). But in selling its coming franchise, Warner Bros. is bragging about the same artistic idealism that got Nolan hired in the first place. "The filmmakers who are tackling these properties are making great movies about superheroes; they aren't making superhero movies," Warner Bros. President Greg Silverman told the Hollywood Reporter.

It's a nice sentiment (and a jab at the visual sameness of the Marvel franchise), but it might only work when the intention is just to make a one-off film. Even Nolan's The Dark Knight, which was a sequel to Batman Begins, was made with no specific future in mind (by all reports, the director had to be heavily coaxed back to even make a third entry). Zack Snyder's Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice is cursed with that unwieldy title because it has to bring Batman into Superman's world and lay the groundwork for the Justice League by introducing several other heroes, including Wonder Woman and Aquaman. In comparison Batman Begins has but one simple task: get the audience on board with its main character. It's a triumph the superhero films of 2015 are seeking to repeat, but amidst Nolan's success, the simplicity of his original pitch has been forgotten.

Long Commutes Are Awful, Especially for the Poor

Commuting, by and large, stinks. Congested roads can quickly turn what would be a scenic drive into a test of patience, and for those who use mass transit, the decision to put their trips in the hands of local public-transit systems can quickly go from freeing to aggravating thanks to late trains, crowded buses, or the bad behavior of fellow riders. But lengthy and burdensome commutes are awful for another reason, too—they disproportionately affect the poor, making it more difficult for them to reach and hold onto jobs.

A recent survey released by Citi found that on average, round trip commutes for those who were employed full time in the U.S. took about 45 minutes and costs around $12 per day. But for both cost and time there were enormous variations. In metro areas like New York and Chicago, average round-trip commute times were longer than an hour, and in Los Angeles the daily cost of commuting averaged about $14—that’s more than $3,500 each year. Nearly two-thirds of commuters said that the cost of getting to work had increased over the past five years, with about 30 percent saying that their cost of commuting had gone up substantially.

More From In the Sharing Economy, No One's an Employee All Your Clothes Are Made With Exploited Labor Where Should Poor People Live?

In the Sharing Economy, No One's an Employee All Your Clothes Are Made With Exploited Labor Where Should Poor People Live? Most unfair of all: When it came to the most extreme commutes in terms of price, the survey found that about 11 percent of respondents who said they paid $21 or more for their daily commute made less than $35,000. For those in the highest income bracket—making $75,000 or more—only 8 percent had such pricey commutes.

Though the Citi survey included a small sample size of about 1,000 respondents, some of the issues brought up by these findings are corroborated by other recent research in this area. According to Natalie Holmes and Alan Berube of the Brookings Institution the shifting locations of impoverished populations is a major contributor to the problem. “Between 2000 and 2012, poverty grew and re-concentrated in parts of metropolitan areas that were farther from jobs, particularly in suburbs, which are now home to more than half of the poor residents of the country’s 100 largest metro areas,” they write.

Between 2000 and 2012, the number of jobs within a worker’s typical commuting distance—which can range from five miles to nearly 13 miles depending on metro area—declined by 7 percent. But for the poor and minorities, who often live in segregated, concentrated neighborhoods, that figure was much bigger: For those at the bottom of the income distribution, the decline in local job opportunities decreased by more than double what it did for the affluent. Proximate jobs for Hispanic metro-area residents has declined by 17 percent, for black residents the decline was around 14 percent. For white metro-area residents the drop was only 6 percent. That means longer, more expensive treks to work for those who need work most.

More concentrated suburban poverty, which is made worse by decreasing job opportunities, and longer, more expensive commutes can be seriously detrimental to social mobility, as recent studies have documented. And that’s not just bad for current residents of these impoverished communities: It also hinders the ability of their children to get to better schools, extracurricular activities, and to slowly but surely build better lives for themselves.

Why Is MERS So Contagious?

When you study something that is, in the strictest sense, invisible, answers to seemingly straightforward questions quickly become elusive.

Like: What makes one virus replicate more efficiently than another? And why do some people get really, really sick—while others are able to fight off the same illness with few symptoms?

“Oh, there are lots of questions,” said Vincent Munster, the chief of the Virus Ecology Unit at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, when I asked him to describe the sorts of things that still have virologists puzzled about the MERS virus. MERS refers to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, a new and potentially deadly virus that has killed at least nine people and sickened dozens more in South Korea since last month, prompting travel warnings and a massive quarantine order. Symptoms can include fever, cough, and shortness of breath—just like many other less serious viruses, which makes MERS difficult to diagnose at first.

“Here's a very important question,” Munster said. “How does this virus spread so easily between healthcare settings?”

MERS has only been observed in humans since 2012, and the recent cases in South Korea represent the largest outbreak of the virus ever outside of Saudi Arabia, where it originated in camels before jumping to humans. “For dromedary camels, [MERS is] very much like what we get in a common cold,” Munster said. “But if it comes into humans, it moves into the lower respiratory tract where it can cause some harm. If you are relatively healthy, you probably don't get too sick from this virus. But if you have co-morbidities—let's say a heart condition, diabetes, or obesity, maybe all three—the outcome for you if you get this virus is increasingly worse.”

Those co-morbidities—the fact that some pre-existing conditions make a person more likely to die from MERS—are a clue to Munster’s earlier question: Why is this virus moving so aggressively through hospitals?

Looking at the population most susceptible to severe illness from MERS may help explain why it is rampant in healthcare settings. The people who are at a greater risk of complications from MERS are more likely to be in the hospital in the first place. And, as The New York Times reported, the physically crowded hospital system in South Korea exacerbates the spread of viral illnesses. The way people go about getting admitted to the best hospitals in South Korea is part of the problem, the newspaper reported: Patients flock to big medical centers and wait in emergency rooms until they can be seen, potentially spreading germs in the process. Before the current outbreak, MERS cases worldwide had already started spiking up since last year. “The reason for this increase in cases is not yet completely known,” the CDC wrote in a statement on its website. “What CDC does know is that because we live in an interconnected world, diseases, like MERS, can make their way to the United States, even when they begin a half a world away.”

Like other respiratory viruses, MERS is highly contagious because it is spread through droplets —from when a person couughs or sneezes, for instance.For scientists who are tracking the latest outbreak, examining the environment where MERS is spreading is only a piece of a larger puzzle. They’re still racing to understand the virus itself. Researchers know that, like other respiratory viruses, MERS is highly contagious because it is spread through droplets—from when a person coughs or sneezes, for instance. But other mechanics of how the virus behaves are a mystery.

“Our current knowledge is still rather imperfect,” said Mark Pallansch, the director of the Division of Viral Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. “Knowledge about viruses and other infectious agents is cumulative. So when you have exposure to diseases over many decades or even centuries, the doctors and scientists have learned more about those specific viruses than something that is brand new. When something is brand new, we often try to see what it is most similar to that we already know about. In the case of MERS, the immediate comparison was to SARS.”

SARS refers to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, a virus that killed nearly 800 people and spread to dozens of countries in an huge outbreak in 2003. SARS and MERS are in the same larger family of viruses, called coronaviruses. Both viruses spread through the respiratory track and can cause severe illness. And both SARS and MERS can affect people and animals. “So by those close comparisons, you at least have a starting point for basic characteristics you can compare and evaluate the new agent to,” Pallansch said. “We have a start to better understanding MERS than if it had been something completely new and unknown. The next point: Is it going to be as bad as SARS?”

Maybe not. Early studies show there’s reason to believe that MERS poses less of a global threat than SARS did—which is good news for the general population—even though scientists don’t yet understand why. “MERS is not as transmissible as SARS," Pallansch told me. “That doesn't answer the question why, but it is an observation that can be used to public-health advantage in that infection control procedures would be expected to be effective in stopping MERS.”

Rigorous hygiene practices—hand-washing with soap and warm water, especially—are the best way for individuals to protect themselves. Health officials are also reminding people to avoid touching their eyes, nose, and mouth. “It does not reduce your risk to zero,” Pallansch said. But hand washing will also help guard against viruses that most people are far more likely to encounter, like the flu. (The CDC estimates thousands of people in the United States alone died from influenza this past winter.)

“I would say MERS is less concerning because it doesn't seem to affect the general population,” Munster said. “This virus seems to be able to jump a couple of times but then hopefully dies out again. But it is of concern in the healthcare setting—and that would be the same in the U.S. Hospitals have a lot of susceptible people inside. People should start thinking really carefully about hospital-hygiene practices and personal hygiene.”

Is Obama Trying to Sway the Supreme Court?

As President Obama took the stage at a hotel ballroom on Tuesday to deliver his latest defense of the Affordable Care Act, you had to wonder who exactly he was trying to reach. Was it the members of the Catholic Health Association—the supportive audience in front of him? Republicans in Congress? The divided public at large?

Or perhaps, was it just the two particular Catholics—Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy—who at this moment hold the fate of Obama’s healthcare law in their hands?

In a 25-minute speech, the president never mentioned King v. Burwell, the case now before the Supreme Court in which the justices must decide the legality of federal insurance subsidies for millions of Americans. But his decision to champion his signature achievement in such pointed terms just weeks before the high court’s ruling is due raised the question of whether Obama was trying to jawbone the justices at the 11th hour.

As he has before, the president turned both to statistics (more than 16 million people covered; the lowest uninsured rate on record) and personal stories (a man whose cancer was caught and cured because of Obamacare insurance) to highlight the benefits of the Affordable Care Act. And with hundreds of Catholics in the audience, Obama made an explicitly moral argument for the law. “It seems so cynical,” he said, “to want to take coverage away from millions of people; to take care away from people who need it the most; to punish millions with higher costs of care and unravel what’s now been woven into the fabric of America.”

It was that final phrase—“woven into the fabric of America”—that seemed most directed at lawmakers in the Capitol and the justices on the Supreme Court. For Obama, the fight to preserve the healthcare in the face of a serious legal challenge carries a sense of deja vu. It was three years ago this month that Roberts alone, straddling the ideological poles on the court, decided to save Obamacare by declaring its requirement that Americans purchase insurance a constitutional exercise of Congress’s taxing power. The difference this time around, Obama not-so-subtly argued, is that the law is no longer “myths or rumors.” It is a reality, and so too would be the consequences of unraveling it. “This is now part of the fabric of how we care for one another,” Obama said. “This is healthcare in America.”

The speech came a day after the president, in response to a reporter’s question, commented directly on the case before the justices, which hinges on whether the law as written allows the federal government to subsidize coverage for residents of states that did not establish their own insurance exchanges. "Under well-established precedent, there is no reason why the existing exchanges should be overturned through a court case," Obama said. "This should be an easy case. Frankly, it probably shouldn't even have been taken up," he added.

“I can’t imagine it’ll make any difference, and I can’t imagine he thinks it’ll make any difference.”There’s a long history of presidents trying to lobby the Supreme Court to rule on their behalf, and Franklin Roosevelt famously tried—and failed—to pack the court with additional members when the original nine invalidated parts of the New Deal. Obama himself has clashed repeatedly with the Court during his tenure. In 2010, he criticized its 5-4 decision in the Citizens United campaign-finance case during the State of the Union, while the justices sat directly in front of him (prompting Samuel Alito shake his hand and mouth, “no”). Two years later, he sharply warned the Court not to rule against his healthcare law the first time around. “I'm confident that the Supreme Court will not take what would be an unprecedented, extraordinary step of overturning a law that was passed by a strong majority of a democratically elected Congress,” Obama said then.

Yet there’s less evidence that even the most persuasive use of the bully pulpit can sway the justices. “Would it help or hurt? I can’t imagine it’ll make any difference, and I can’t imagine he thinks it’ll make any difference,” said Charles Fried, the Harvard law professor who argued cases before the court as Ronald Reagan’s solicitor general. (Fried has weighed in on the Obama administration’s side in King v. Burwell.)

While the Supreme Court likely won’t issue its Obamacare ruling until the end of the month, the justices often make their decision soon after the oral arguments, which for King v. Burwell occurred in March. “I would think the die is cast,” Fried said. At the same time, the convoluted opinions in the 2012 healthcare decision left the impression with some court-watchers—bolstered by reporting from Jan Crawford of CBS News— that Roberts’s decision to uphold most of the law came late in the process, or even that he changed his mind after the initial conference. It is once again Roberts, along with Kennedy, who is considered the possible swing vote in King v. Burwell.

Obama’s speech was laying the groundwork for the political fight to come.The chief justice is seen as being uniquely sensitive to the Supreme Court’s public reputation in the polarized political environment, but he surely needs no reminder about the stakes of the latest Obamacare challenge. Obama’s speech, then, along with his comments on Monday, were more about laying the groundwork for the political fight to come if the Court does strike down the federal subsidies in 36 states. As he told reporters, “Congress could fix this whole thing with a one-sentence provision.” And as he well knows, it won’t.

Republicans aren’t about to clean up a law they have spent years trying to gut, and if the Court rules against it, the best Obama can hope for is that they’ll offer to restore the subsidies in exchange for other revisions the president won’t accept—like ending the individual or employer mandates that similarly tie the legislation together. The argument you’ll hear is the same one he made on Tuesday: The Affordable Care Act is now the reality of healthcare in America—“woven into the fabric”—and the painful disruptions and the parade of horribles that Republicans predicted five years ago will now only come to pass if they allow it to unravel. Of course, Obama could easily have waited a few weeks to deliver the speech, if he needed to give it at all. But Obama apparently wanted to begin mounting his case now—and, perhaps, sway any justice who might be having last-minute doubts.

Jeb Bush's European Adventure

It’s like being stuck in endless sequels to the movie Taken. A carefree Republican presidential candidate heads to Europe. The voyage promises to be fun and low-key—a chance to learn and have a good time—but then everything suddenly spins out of control. Worst of all, there’s no Liam Neeson around to save them—just a pack of reporters eager to see them falter.

That’s the scenario Jeb Bush is looking to avoid as he embarks on a tour of Central and Eastern Europe, kicking off with a speech on Tuesday in Germany.

Consider the fate of some predecessors. In February, Chris Christie went to London to burnish his foreign-policy credentials and show his seriousness. The result was what Politico described as a “weeklong train wreck”:

The Republican governor started a trip to London by bobbling a question about whether measles vaccinations should be mandatory. The next day he snapped at a reporter who tried to ask him about foreign policy. He faced questions about a new federal investigation into his administration and came under scrutiny for his taste in luxurious travel.

Scott Walker had a rough run of it too. Because he, like Christie, is a governor, there’s a desire to show that he knows how to carry himself abroad. Instead, Walker punted over and over again, declining to answer a series of questions during an appearance at Chatham House, a London think-tank. One reason was the traditional warning that “politics stops at water’s edge”—the idea that politicians shouldn’t criticize American policy while overseas, increasingly honored in the breach. But that didn’t explain why he couldn’t lay out a general foreign-policy vision—or say whether he believed in evolution.

When Bobby Jindal went to the U.K., he claimed that there were areas of Britain that the government had effectively ceded to radical Muslims. Unsurprisingly, that turned out not be true; more surprisingly, he refused to concede that there was no evidence for his claim.

And then there was Mitt Romney, whose 2008 tour through the continent was really more like Spinal Tap, with marginally fewer deceased percussionists. At the start of the trip, he managed to alienate even the British, America’s closest and most tolerant allies, by questioning their preparation for the London Olympics. Next, he was roundly attacked for comments on Palestinian culture he made while in Israel. In Poland, he met with Lech Walesa, only to be attacked by Solidarity, the union Walesa once led. “What about your gaffes?” a Washington Post reporter memorably shouted at Romney. He didn’t reply—but then what was there to say that hadn’t already been said?

It’s enough that CNN referred to “the curse of London.” Not everyone stumbles quite so badly—you’re just not as likely to hear about it. Marco Rubio visited, too, though back in December 2013, before he was a candidate for president. That visit was received fairly quietly, but generally politely. (Rand Paul also visited London, but, uh, not that one.)

One big danger in the trip is embedded in the purpose. The goal is less to make concrete connections overseas—though that’s useful—than to imbue a candidate with gravitas, especially if he’s a governor without much foreign-policy experience. But once a politician gets there, reporters are eager to ask questions about the trip and what they think about the world. Perhaps the smartest course for a candidate is to offer solid but anodyne answers and try to make few waves. (According to this rubric, Walker simply erred in being too cautious.)

Not every trip is so fraught—consider the rapturous welcome Barack Obama received when he delivered a speech in Berlin in July 2008. But Obama had several advantages. For one, he’d traveled abroad a fair amount and was a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, so he had less to prove.

For another, his politics made him much more welcome. That’s a challenge for every Republican who travels across the Atlantic—in most of Europe, the GOP is simply far to the right on most issues, so Republicans find fewer natural allies. Even in Britain, where the Conservative Party is in power, the Tories are to the left of the Republican Party, and Prime Minister David Cameron is unusually close to President Obama. On a continent where a strong social safety net is a given, a party that has railed against it for decades faces an uphill battle. Hawkish foreign-policy stands also don’t go over so well. (Already, European foreign ministers are thought be more or less tacitly supporting Hillary Clinton.)

Obama had one other big advantage when he went to Germany: His last name wasn’t Bush. George W. Bush was immensely unpopular with Europeans and in particular with Germans, and the prospect of a new American leader excited them. Needless to say, that remains a challenge for Jeb Bush, George’s little brother. The New York Times went out into the streets of the German capital and found that Berliners are skeptical of the Bush name—more, even, than Americans are. “The alarm bells ring,” one young German said.

One way to handle that risk is simply not to worry too much about the way the Germans take it. As McKay Coppins reports, Bush seems to be speaking to two audiences by using his trip to rail against Vladimir Putin. That telegraphs to Eastern European nations that he’d be on their side, and it positions him as a Russia hawk within the Republican primary field.

That message was met politely by an audience of roughly 1,000 in Germany—just a hair short of the 200,000 who came out for Obama (albeit at a later stage in the campaign). Bush’s next task: Get through the next four days while avoiding the traps that snared so many of his Republican rivals.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower