Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 337

September 28, 2015

The Big Question: Reader Poll

We asked readers to answer our question for the November issue: What science-fiction gadget would be most valuable in real life? Vote for your favorite response, and we’ll publish the results online and in the next issue of the magazine.

Create your own user feedback surveyComing up in December: What is the greatest comeback of all time? Email your nomination to bigquestion@theatlantic.com for a chance to appear in the December issue of the magazine and the next reader poll.

The Changing Face of America

More than 59 million immigrants have arrived in the country since the passage of the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the Pew Research Center announced Monday in a new report.

The report added that the U.S. population in 2065 will be about 441 million, up from about 318 million now. The growth will be driven by Asian and Hispanic immigration; 18 percent of the population in 2065 will be foreign-born, Pew says.

The Pew report was released Monday to mark the 50th anniversary of the passage of the immigration act. That law ended a system that heavily favored migration from Northern Europe, and opened up America’s doors to people from all over the world.

Here are some key takeaways from the report:

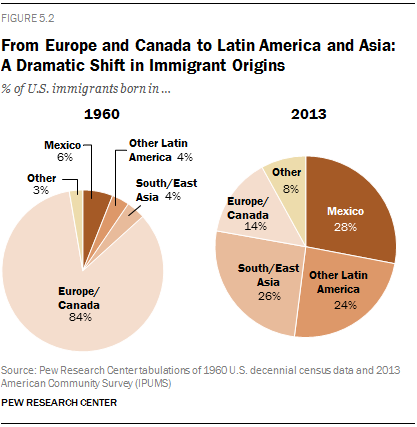

In 2013, a record 41.3 million foreign-born people lived in the U.S.—13.1 percent of the population. The growth has been sharp since 1965, though it has slowed in recent years. Here’s what that looks like: Immigration to the U.S. has shifted from Europe and Canada in the 1960s and ’70s to Latin America and Asia now.

Immigration to the U.S. has shifted from Europe and Canada in the 1960s and ’70s to Latin America and Asia now.

The foreign-born share of the U.S. population in 2065 will be nearly 18 percent.

The foreign-born share of the U.S. population in 2065 will be nearly 18 percent.

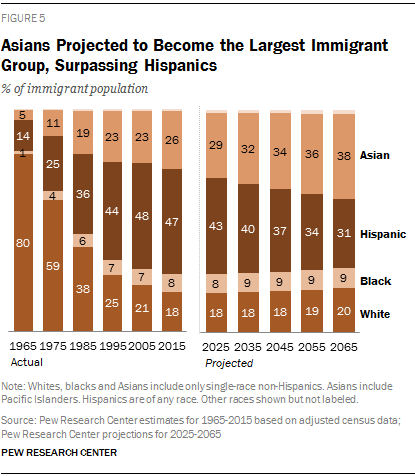

Asians are projected to be the top source of migrants to the U.S. in 2065.

Asians are projected to be the top source of migrants to the U.S. in 2065.  Attitudes toward the immigrants are mixed.

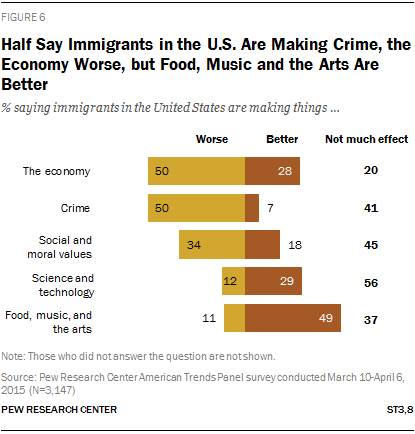

Attitudes toward the immigrants are mixed.

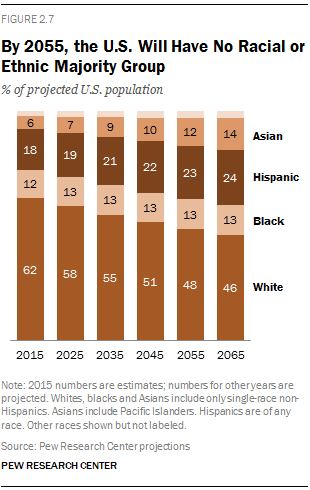

By 2055, there won’t be a racial or ethnic majority in the U.S.

By 2055, there won’t be a racial or ethnic majority in the U.S.

September 27, 2015

Who Will John Boehner Be Now?

John Boehner was thinking about yoga this morning.

“It’s great for my back,” he said Sunday in an interview on CBS’s Face the Nation. “I’ve had back problems for 50 years.”

Boehner said he hasn’t been as diligent about practicing yoga lately, but he will soon have more time to fit in a few sun salutations. On Friday, the congressman from Ohio shocked Washington and members of both parties—even his closest friends—when he announced that he would step down as speaker of the House and leave Congress altogether at the end of October. He walked into that day’s press conference singing "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” a lighthearted start for a man who some say sacrificed his career for the sake of the House and its governing party.

Boehner’s departure marks the end of a nearly five-year-long tug-of-war between the House’s establishment wing and its Tea Party conservatives. As Norm Ornstein wrote this morning:

It was inevitable that these two forces—radicals flexing their muscles, demanding war against Obama from their congressional foxholes, and leaders realizing that a hard line was a fool’s errand—would collide violently. … Boehner would have been placed at the right end of his party a couple of decades ago. But as a realist operating in the real world of divided government and separation of powers, he became a target within his own ranks.

Rumors that the speaker would resign or be ousted were not uncommon, especially after a historic number of his colleagues voted no in his reelection in January. The most recent fight—over Planned Parenthood—threatened to shut down the government at the end of this month. But now that he’s on his way out, Boehner doesn’t have to please the conservatives demanding language to defund the organization in the legislation that will keep the government running. And the chances of passing a “clean” bill look good so far.

Boehner said Sunday that a shutdown won’t happen.

“I expect a little more cooperation from around town to get as much finished as possible,” he told host John Dickerson. “I don't want to leave my successor a dirty barn. I want to clean the barn up before the next person.”

House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy is widely regarded as the favorite to succeed Boehner. He hasn’t formally announced he wants the job, but he started calling members to rally support for the speakership soon after Friday’s announcement. Boehner said he planned to step down at the end of 2014, but stayed on when Eric Cantor’s stunning primary defeat last summer shook the chamber. Pope Francis’s visit to Congress this week, which Boehner organized, “helped clear the picture” on timing. The congressman has tried to bring a pope to the Capitol for nearly 20 years.

Boehner’s exit has renewed urgency for handling a few outstanding legislative debates, including raising the debt ceiling, funding the country’s highway system, and re-opening the Export-Import Bank, whose funding expired in July.

“I’ve got another 30 days to be speaker,” Boehner said Sunday. “I’ll make the same decisions the same way I have the last four-and-half years.”

As for what happens next month, when he puts down the gavel for good:

“I don’t know,” Boehner said. “We’ll figure it out.”

The Pope's Meeting with Sex-Abuse Victims

Pope Francis addressed the Catholic Church’s sex-abuse scandal on Sunday.

“I hold the stories and the suffering and the sorry of children who were sexually abused by priests deep in my heart. I remain overwhelmed with shame that men entrusted with the tender care of children violated these little ones and caused grievous harm,” he said in unscripted remarks before a speech in Philadelphia. “I am profoundly sorry. God weeps.”

Francis said that “the crimes and sins of the sexual abuse of children must no longer be held in secret,” according to a transcript provided by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

“I pledge the zealous vigilance of the church to protect children and the promise of accountability for all,” he said.

This weekend, Francis met privately with three women and two men who suffered sex abuse as minors, according to the Vatican's English language press representative. They were accompanied by several clergy members, including Cardinal Seán Patrick O'Malley, whom Francis named to a Vatican anti-abuse commission last spring. More on the meeting from the representative:

The Pope spoke with visitors, listening to their stories and offering them a few words together as a group and later listening to each one individually. He then prayed with them and expressed his solidarity in sharing their suffering, as well as his own pain and shame in especially in the case of injury caused them by clergy or church workers.

Francis vowed to punish offenders:

He renewed the commitment of the Church to the effort that all victims are heard and treated with justice, that the guilty be punished and that the crimes of abuse be combated with an effective prevention activity in the Church and in society.

The pope is wrapping up his first-ever visit to the United States, which he began in Washington earlier this week.

Lisbeth Salander: The Girl Who Survived Her Creator

In a 2010 piece for Slate, Michael Newman argued that Lisbeth Salander, the brilliant, fearsome hacker heroine of the hit Millennium series deserves better than the man who created her. “Of all the unlikely triumphs of Lisbeth Salander,” he writes, “the most gratifying is her victory over Stieg Larsson.” This victory came in more ways than one: The Swedish author and journalist died in 2004 at the age of 50, after handing over the manuscripts for the first three books, but before seeing a single published copy, or reaping any of the profits from the 80 million copies sold worldwide, not to mention the four film adaptations in Swedish and English.

Knopf

Knopf With Larsson no longer around, Newman posited, “maybe now someone else can pick up Salander’s story.” His wish was granted earlier this month with the publication of The Girl in the Spider’s Web, a continuation of the series written by the Swedish writer and biographer David Lagercrantz. The most prominent name on the cover is Lagercrantz’s, then the words “A Lisbeth Salander Novel,” and then in smaller type at the bottom, “Continuing Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Series.” It’s clear, without so much as cracking the spine, that the girl with the dragon tattoo has outlasted her creator.

Larsson’s legacy is complicated by a messy battle between his father and brother—both of whom inherited the bulk of his property and approved this new book—and his partner of 32 years, Eva Gabrielsson. Excluded from his estate thanks to Sweden’s lack of legal recognition for common-law spouses, Gabrielsson has expressed her disgust at the fourth Salander novel in no uncertain terms. But the practice of writing new stories for iconic characters after their authors pass on is long-established, and is becoming increasingly popular in the era of the reboot, the remake, the franchise, and the fictional “universe.” This prompts questions of ownership that are both literal and philosophical. If authors die without dictating what should happen to their characters, who gets to decide their fate? When should stories end? And if characters become celebrated and beloved enough, do they stop essentially belonging to the people who created them?

* * *

A few years ago, Lagercrantz, who’d previously published a hugely well-received biography of the soccer star Zlatan Ibrahimović and a novel about Alan Turing, was having a drink with his agent, discussing his career, mulling his increasingly “depressive” work, and wondering whether he was simply better as a writer when he was channeling someone else. He saw his agent’s face suddenly change. Not long after, he was smuggled surreptitiously into the basement of Norstedts Förlag, Larsson’s publishing house, to discuss writing the fourth book in the Millennium series. He walked home in “a state of fever.”

Tasked with dreaming up a new plot for Larsson’s protagonists, the crusading journalist Mikael Blomkvist and the brilliant goth-hacker Lisbeth Salander, Lagercrantz woke at four the next morning thinking about a story he’d done in his reporting days about savants. At the time, the Edward Snowden scandal was in full burn, and after re-reading Larsson’s books over a few days, Lagercrantz suddenly had his synopsis: An autistic child who’d never spoken witnessed a murder, whose perpetrators had connections in the tech world reaching all the way to the NSA. He sent it to the publisher, and after a few anxious days received a three-word text message: So damn good. “And then off we went,” he says.

David Lagercrantz (Magnus Liam Karlsson)

David Lagercrantz (Magnus Liam Karlsson) For Lagercrantz and his publishers, there had to be a balance between staying true to Larsson’s voice and vision without aping his style too directly. “I couldn’t give Lisbeth Salander three kids and leave them at daycare or anything,” he says. “Lisbeth should be Lisbeth and Mikael should be Mikael. We should feel at home in his universe and with his storytelling. But at the same time, it was very important that I was not pretending to be Stieg Larsson, because that was of course impossible.”

Lagercrantz mentions Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, stating that it’s a huge privilege to inherit such characters, although each new interpreter is bound to have his or her own understanding of the people in play. But at the same time, he believes that some characters, once they’ve reached a level of popularity and public fascination, become concepts that are needed rather than desired. “There are certain characters who we go back to, over and over: the Greek gods, and Sherlock Holmes, and right now we’re obsessed with the superheroes in Hollywood and the Marvel comic figures,” he says. “There are certain characters who we need. Lisbeth Salander is certainly one of them. She changed crime fiction in a way. She’s the girl who refused to be a victim.”

Writing Salander wasn’t easy. In the beginning Lagercrantz exaggerated her too much, making her “a sort of terrible punk warrior,” and giving her emotions that just didn’t fit her persona. Meanwhile, the pressure of replicating such an iconic character only made things harder. “I had nightmares that people would come after me,” he says. But eventually he realized the key was letting the character do, rather than be. “Lisbeth is best in action,” he says. “The hardest thing was to find the introspection.”

Larsson’s style presented its own challenges. Newman isn’t alone in finding his writing lacking. “We’re not looking at Tolstoy here,” Joan Acocella wrote in The New Yorker in 2011. “The loss of Larsson’s style would not be a sacrifice.” Among the worst flaws of the first three books are their clunky dialogue, their absurdly literal descriptions, and their author’s dedication to describing the minutiae of what characters eat and drink on a given day. (Blomkvist: coffee and open-faced sandwiches. Salander: McDonald’s and soda.) Larsson’s storytelling, while indeed sweeping and ornate, can be impossible to follow, while his inability to project emotions onto his characters is almost Salanderian in its detachment.

The Girl in the Spider’s Web, then, is masterful in the way it negotiates mining Larsson’s weaknesses for authenticity’s sake while polishing the rough edges. Lagercrantz’s story is intricate and ambitious, and his new antagonists for Salander and Blomkvist are appreciably exaggerated, without crossing a line into ridiculousness. The effect for the reader is very much one of reading a Stieg Larsson book, warts and all.

While writing, Lagercrantz was only too aware of the controversy surrounding his project. In an Agence France-Presse interview in March, Gabrielsson railed against the new book, stating it all boiled down to “a publishing house that needs money (and) a writer who doesn’t have anything to write so he copies someone else.” She called Lagercrantz “a totally idiotic choice,” criticizing his background, his journalistic credentials, and even the planned title for the book (from Swedish, it roughly translates as That Which Does Not Kill Us). “I know all the discussion, and I welcome all the discussion,” Lagercrantz says. “But I didn’t have any moral doubts about it at all. And I feel it more and more now, that people really needed Salander.”

* * *

Following Ian Fleming’s death in 1964, his publishers commissioned authors including Kingsley Amis (using a pseudonym), John Gardner, Sebastian Faulks, William Boyd, and Anthony Horowitz to continue the James Bond series (Horowitz has also written two Sherlock Holmes novels, The House of Silk and Moriarty). Eric Van Lustbader took over the Jason Bourne series following the death of Robert Ludlum. In 2012, Terry Pratchett declared that his daughter Rhianna would carry on the Discworld novels after his death, although she ultimately declined to do so. A Song of Ice and Fire fans, meanwhile, fret openly about George R.R. Martin’s failure to appoint a literary successor in the case of his untimely death, to Martin’s outspoken chagrin.

The instinct to further gratify fans after a series has concluded is embodied most prominently by J.K. Rowling, who continues to tweet out tidbits and details more than eight years after the release of her final Harry Potter book, and whose new two-part play extending the story will debut in London next year. Rowling, obviously, has total control over the universe she created, although unauthorized Harry Potter fan fiction is rife online, with more than 80,000 stories existing on one website alone. The line between fan fiction and published work was also blurred by 50 Shades of Grey, the juggernaut S&M book written by E.L. James. The series was famously created as fan fiction responding to Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight books, but after some fans objected to the explicit content, James reinvented the characters and moved it to her own website.

The instinct to continue existing stories isn’t new—in 1914, Sybil Brinton published the first work of Jane Austen fan fiction, titled Old Friends and New Fancies: An Imaginary Sequel to the Works of Jane Austen. More recently, the author Emma Tennant published Pemberley, a Pride and Prejudice sequel in 1993, while the late crime writer P.D. James tackled her own Austen pastiche in 2011, Death Comes to Pemberley. This month, the former basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar releases Mycroft Holmes, a book about Sherlock Holmes’s older brother. “The leap between fan and novelist is a whole lot more work,” Abdul-Jabbar told Electric Literature.

Gabrielsson, Larsson’s partner, maintains that the benefit of co-opting existing characters goes to publishers, not readers. “They say heroes are supposed to live forever,” she said in an interview with Agence France-Presse. “That’s a load of crap, this is about money.” Martin seems to agree, telling the Sydney Morning Herald, “One thing that history has shown us is that eventually these literary rights pass to grandchildren or collateral descendants, or people who didn’t actually know the writer and don’t care about his wishes. It’s just a cash cow to them.” Which results, he added, in “abominations to my mind like Scarlett, the Gone With the Wind sequel.”

Martin has vowed never to let another writer pick up his mantle; meanwhile Game of Thrones fanfic flourishes online. Rowling, for her part, encourages fan fiction as long as no one tries to profit from her work, but the author Ann Rice despises it. “I do not allow fan fiction,” she wrote in a letter to her fans. “The characters are copyrighted. It upsets me terribly.”

* * *

The question for authors to consider in this brave new world of mimicry, both professional and otherwise, is to what extent they consider their characters to be theirs and theirs alone. For most, it isn’t something that will become an issue during their lifetime: Copyright law stipulates that books only enter the public domain 70 years after the death of the author, even if most fanfic writers aren’t limited in terms of what they can post online.

It isn’t a simple question, and by no means does it have a universal answer. Arthur Conan Doyle, when asked by a playwright if he could give Sherlock Holmes a wife, reportedly replied, “You may marry him, or murder him, or do anything you like to him.” Stephen King has published his own fan-fictionesque works featuring monsters created by H.P. Lovecraft. C.S. Lewis once encouraged a young fan to “fill up the gaps in Narnian history” herself. Ursula Le Guin, however, has objected to the way fan fiction is distributed, and the fact that readers might encounter it and assume it’s her work.

There’s a difference, clearly, between unauthorized writing online and a published work that continues the series an author created. In Larsson’s case, most of the controversy stems from the fact that he never got to choose; he died before his books were published, and thus never had to think about what might happen to his characters without him. And Gabrielsson is right in assuming that publishers almost always choose to continue popular series for financial reasons. But that doesn’t mean readers don’t also benefit. Lisbeth Salander is, as Lagercrantz states, an extraordinary heroine whose hacker skills are more relevant than ever in an increasingly high-tech surveillance society. In creating such a compelling female character, Larsson gave readers a significant gift. The fact that she continues to thrive on the page long after his lifetime is both a testament to his imagination and a sacrifice he didn’t get to approve.

September 26, 2015

After 40 Years, Rocky Horror Has Become Mainstream

The Rocky Horror Picture Show, that campy beacon of sexuality and self-acceptance, premiered in the U.S. on September 25, 1975, at the Westwood Theater in Los Angeles. The film follows a terribly traditional 1950s-esque couple, Brad (Barry Bostwick) and Janet (Susan Sarandon), as they spend the night in the gothic castle of the cross-dressing alien Dr. Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry) and his Transylvanian posse. Following its release, it was quickly shelved. But due to the marketing savvy of a young executive at 20th Century Fox, Rocky Horror was revitalized in the form of a midnight screening the next year at the Waverly Theater in Greenwich Village, New York. Over the next four decades, Rocky Horror would be transformed from failed movie-musical to underground phenomenon to rebellious coming-of-age ritual to mainstream icon, all thanks to the hardcore fans who flocked to its late-night showings.

Born in the midst of the punk revolution in the form of Richard O’Brien’s 1973 dark cabaret musical The Rocky Horror Show and reincarnated into The Rocky Horror Picture Show by Jim Sharman two years later, the film is currently the longest-running movie in history. Through its immersive, fan-driven screenings and unadulterated idolatry of weirdness, it’s ended up so ingrained in the cultural fabric that networks like HBO and Fox are using the film’s 40th anniversary to capitalize on its popularity. Rocky Horror, once an embodiment of all that’s transgressive and outside the mainstream, has become the ultimate crowd-pleaser.

The film and its endearingly kooky and devoted subculture have been referenced in everything from Sesame Street to Fame to That ‘70s Show to Glee, which did a “watered-down, Disney-fied version” during its second season. (Instead of being from Transsexual, Translyvania, Frank-N-Furter, played by the Glee character Mercedes, is from Sensational, Translyvania.) Earlier this year, Fox announced a Rocky Horror two-hour TV special directed and choreographed by Kenny Ortega (High School Musical, This Is It) and executive produced by Lou Adler, who also produced the original.

It wasn’t always so. According to the National Fan Club’s president Sal Piro, who wrote a definitive history of the film, Rocky Horror’s countercultural traditions began when a group of regulars made a weekly pilgrimage to New York’s Waverly Theater. Sitting in the first row of the balcony, they’d scream for their favorite characters, boo villains, and adlib jokes that would be repeated at future screenings and codified into a kind of audience script.

From the roots of a rowdy small group of filmgoers, entranced by the film’s portrayal of tranvestism, orgies, and unabashed sexuality as well as its campy charm, came a new trend: A shadow cast began performing the story beneath the screen. Their presence made every Rocky Horror screening more of a mini-musical-dance-party that was entertaining in its own right—if newcomers (referred to as “virgins”) weren’t familiar with the audience lines or the “Time Warp,” Rocky Horror’s famous dance-along hit, they were able to pick it up soon enough, and the sense of every screening being an event encouraged more newcomers to experience the movie.

Midnight screenings and new accompanying casts sprung up around the country as word of the New York-based spectacle spread among devotees. Young people who felt disconnected from society could identify with the film’s literal aliens, and for those from more straight-laced backgrounds, the initially conservative Brad and Janet’s presence gave them a way into a fantasy world outside their immediate experience. Still, the appeal wasn’t only in the film’s content, but the sense of community and way of thinking that came along with its almost-ritualistic conventions. As Roger Ebert wrote, “The Rocky Horror Picture Show is not so much a movie as more of a long-running social phenomenon” because “the fans put on a better show than anything on the screen.”

This combination of inclusivity and immersive entertainment became a key factor in Rocky Horror’s growing popularity. And as the nation became more welcoming of alternative lifestyles and orientations, the film became a not-so-cult hit, with “Time Warp” played at school dances and Rocky Horror allusions infiltrating popular culture, turning the film and its ostentatious fans into a reference point.

Rocky Horror transformed from failed movie-musical to underground phenomenon to rebellious coming-of-age ritual to mainstream icon.Regardless of HBO’s and Fox’s recent attempts to capitalize on Rocky Horror’s cultural cache, the midnight screenings continue and the film’s fan base gleefully continues to partake in the mayhem-inducing, intensely participatory experience that can be found in many an indie movie theater across the country. The time-honored traditions—such as throwing rice during the film’s wedding scene or toasting along with Frank-N-Furter at dinner—aren’t something that can be captured in a television special.

Despite the broad appeal of the movie, the film’s most hardcore fans, who often become cast members themselves, continue to congregate around the world to celebrate its message. Sarah de Ugarte, who’s part of the unofficial New York cast at Bow Tie Chelsea Cinemas, first saw the show at age 18. Two years later, she has taken time off from Stanford to devote her time to performing Rocky Horror.

This weekend, she’s at the Rocky Horror 40th Anniversary Convention in Manhattan, where around 500 performers and fans from around the world are gathering to celebrate the movie, flanked by the film’s stars Little Nell (Columbia), Barry Bostwick (Brad), and Patricia Quinn (Magenta). While the film might have achieved mainstream success, the passion of its most devoted fans remains an emblem of Rocky Horror’s underground origins.

“I think it has a large appeal because ... people are accepted as they are: fabulous, regardless of gender or sexuality or race or body type,” de Ugarte says. “I love Rocky because it lets me and everyone around me be uninhibited and fly our freak flag, and not be ashamed to be ridiculous.” It’s that mantra that has surely contributed to the lasting appeal of a long-beloved phenomenon: years ahead of its time, but now appreciated by more than its creators could ever have dreamed.

Jeremiah Wright Is Still Angry at Barack Obama

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — It didn’t seem like the proper setting for an angry, anti-American firebrand.

An amiable crowd was milling around the fellowship hall of the United Church of Chapel Hill on a Saturday morning, slurping coffee and eating bagels. Posters advertised trips to the Holocaust Museum, advocated for LGBT rights, and warned against ableism, with helpful definitions. The crowd skewed white and, as in many churches, older, but befitting this college town, it was an eclectic bunch: aging granola grandmas, middle-aged men in black jeans, and salt-and-pepper goatees, older men in suits.

What, exactly, was the Reverend Jeremiah Wright—former pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, erstwhile minister to Barack Obama, and the man who infamously thundered, “God damn America!” doing here?

Lecturing on racial reconciliation, as it turns out—at least that was the idea. For nearly three hours, that’s mostly what Wright did. In the last 10 minutes, he couldn’t quite hold himself back, and the firebrand emerged. (Perhaps it’s no coincidence that his biblical namesake was known for angry harangues about injustice in society.) What does Wright think about the refugee crisis in Europe and anti-immigration rhetoric in the United States?

“I heard Donald Trump say if you’re here illegally you need to go back. Let’s start in the 1400s!” he said, then quickly moved to discussing the “the illegal state of Israel.” On the plight of Palestinians, he offered a Canaanite’s perspective: “What kind of God you got that promised your ass my land?”

Just as suddenly he was veering back to Trump: “You want to talk about thugs and rapists? Georgia was founded as a colony for criminals!”

“Our Halfrican-American president—he don’t want to talk about reparations. It’s not personal responsibility. You’re missing the point. Let’s talk about white-on-black crime.”Next question, from an older woman in a beautiful, long robe with a long, gray-accented braid: Should black Americans receive reparations? The pastor was off and running again, another circuitous answer taking him to Luke 19 via the Caribbean. “One of the reasons America has never confessed to its original sin is that confession means repentance, and repentance means you gotta pay,” he said. “That’s not black people getting a check next week—it’s structural issues” like housing covenants and redlining, he said.

Then he turned to his most famous former congregant, accusing him of failing to speak out about structural racism.

“My daughter and granddaughter call him our Halfrican-American president—he don’t want to talk about reparations,” Wright said, never naming Obama. “It’s not personal responsibility. It’s not ‘pull your pants up.’ Don’t get on Fox News and lecture black men. You’re missing the point. Let’s talk about white-on-black crime. Until we have a hard dialogue, it’s all gonna be superficial, ‘Kumbaya,’ ‘We Shall Overcome.’”He followed that with an extended metaphor about sheepdogs—once they’re trained to protect a flock, he said, they’ll fight against even dogs from their own litter—and declared, “We got a lot of sheepdogs in the African American community.” He didn’t name any. He didn’t really need to.

* * *

Wright has a penchant for tossing in his most inflammatory comments as near-afterthoughts. In the noted April 2003 sermon, Wright was nearly finished when he said, “Let me leave you with one more thing,” and then proceeded to build to the imprecation: “Not ‘God Bless America’; God damn America! That’s in the Bible, for killing innocent people. God damn America for treating her citizens as less than human. God damn America as long as she keeps trying to act like she is God and she is supreme!”

When that sermon—and another, from shortly after 9/11, in which he said that “America’s chickens are coming home to roost”—surfaced in 2008, Wright was briefly the biggest story in American politics. Coverage of the sermons dominated the news and inspired what many people still consider Obama’s finest and most important speech, an address on race.

Gradually, the story faded away. But although Wright, who had already announced his retirement, slipped into relative obscurity, he didn’t go away. He’s popped up occasionally to reignite a furor. In June 2009, he said he had voted for Obama despite the candidate’s disavowal but hadn’t spoken to him. “Them Jews ain’t going to let him talk to me,” he saidd. “They will not let him to talk to somebody who calls a spade what it is .... I said from the beginning: He’s a politician; I’m a pastor. He’s got to do what politicians do.” Needless to say, his anti-semitism drew condemnation. In 2010, he complained that Obama “threw me under the bus.” He was “toxic” to the White House, Wright said—hard to disagree with, given his comments the year before.

Wright is a flawed messenger with a flawed message, but the message feels far more suited to the times in 2015 than it did to 2008. Back then, the prospect of an Obama election set off giddy daydreams of a post-racial America. Today, nearly three out of five Americans say that race relations in the United States are bad. Wright’s argument in those sermons more than a decade ago, that the United States was structurally racist and conceived in white supremacy, are now commonly voiced, by those like my colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates, Black Lives Matters activists, and white liberals. Another cause he championed back then has come to draw adherents from across the political spectrum—the dangers of mass incarceration. Wright said in 2003:

The United States of America government, when it came to treating her citizens of Indian descent fairly, she failed. She put them on the reservations. When it came to treating her citizens of Japanese descent fairly, she failed. She put them in internment prison camps. When it came to treating the citizens of African descent fairly, America failed. She put them in chains. The government put them on slave quarters, put them on auction blocks, put them in cotton fields, put them in inferior schools, put them in substandard housing, put them in scientific experiments, put them in the lowest paying jobs, put them outside the equal protection of the law, kept them out of the racist bastions of higher education and locked them into positions of hopelessness and helplessness. The government gives them the drugs, builds bigger prisons, passes a three-strike law and then wants us to sing “God Bless America”?

The tense current mood on race is what brought Wright to Chapel Hill. Since the United Church of Christ was formed in 1957 from the merger of Congregationalists and the Evangelical and Reformed Church, the denomination has been closely involved in civil rights. But while it does include some predominantly black congregations—such as Trinity—the church remains nearly 90 percent white. In a January 2015 pastoral letter to member churches, UCC leaders discussed racism and police violence against people of color and called on members to work for racial reconciliation. That call inspired the United Church of Chapel Hill to invite Wright to speak.

What’s remarkable for anyone familiar with Wright only from those two sermons or from his bigoted remarks, is how different the man can be in person. Clad in black trousers and a collarless purple shirt with black-and-white tribal patterns on it, Wright seemed more like the retired grandfather he is than a prophet of doom. He spent five minutes trying, and failing, to get his phone to play a clip of the Howard Gospel Choir. He spent much of the next 45 minutes on a raconteurish, often-entertaining narration of his early life and how he became interested in black sacred music.

Over the next two hours, Wright ruminated on the need for alternative perspectives to a European-centered worldview—as he put it, “different does not mean deficient”—in everything from music to pedagogical styles to theology. (In one memorable moment, he demonstrated differences in rhythmic sensibility by asking white and black members of the audience to clap along with songs; with surprising uniformity, white ones clapped on the traditional, European dominant beats while black ones clapped on the offbeats.) Some of what he said seemed to have emerged whole from the 1990s via time machine, such as Wright’s impassioned defense of Ebonics as carrying all the technical characteristics of a language. Some parts smacked of pseudoscience, like the idea that different learning styles for white and black children was “in their DNA.”

“You want to talk about thugs and rapists? Georgia was founded as a colony for criminals!”But much of it sounded very much like what you might hear from liberal professors in university classrooms across America: the emphasis on structural racism; skepticism of imperialism in many guises; sympathy for Palestinians and even antipathy toward Israel; praise for interdisciplinarity; the plea for multiculturalism and alternative viewpoints. Adding to the professorial vibe, Wright peppered his talk with repeated “assignments” for reading: the pioneering black historian Carter Woodson; C. Vann Woodward’s classic The Strange Career of Jim Crow; A. Leon Higginbotham’s In the Matter of Color: The Colonial Period; academic monographs in various disciplines. (The parallels between Coates and Wright were amusing: an interest in the study of white supremacy; a deep immersion in academic literature; a reverence for Howard University as an intellectual Mecca.)

Of course, Wright occasionally put things in more colorful terms: Arguing that the U.S. needed to write a new constitution from scratch because the current one is inherently racist, he quipped that trying to fix the problem with amendments is like leaving sugar out of a cake and trying to rectify the problem by sprinkling sugar on top once it’s out of the oven. That debate itself, however, is the stuff of academia.

Yet Wright had little to say about Black Lives Matter. “You think Occupy is something, you think Black Lives Matter is something?” he asked. “In the ’60s kids were taking over administration buildings, taking over campuses, locking up faculty!” But later he evinced more respect for the movement, professing himself “giddily happy” and brushing back older civil-rights leaders who have been critical. “If you think their language is something, y’all should have heard SNCC,” he said. “Old people say, ‘They don’t know what they’re doing.’ They know exactly what they’re doing! You don’t know what you’re doing!”

Even with Wright’s spicy closing remarks, it was a strange experience. Like Monica Lewinsky, who recently reemerged complete with a TED Talk, it’s hard to imagine Wright outside of the context of his brief political infamy, to think of him as a real person whose life has gone on. If Wright had felt any need to tone down his personality since the controversy, it hardly showed. He only briefly showed a flash of self-consciousness, pausing to be sure his lecture was being recorded before delivering an elaborate joke about black dialect. The joke won’t translate in writing, but suffice it to say that the punchline was disappointingly PG-rated.

But even the Prophet Jeremiah couldn’t deliver only jeremiads. And even his message was rejected by the Judeans. True to the biblical pattern, once the lecture concluded, the Chapel Hillians streamed politely out to a parking lot, got into cars adorned with proudly faded Obama-Biden bumper stickers, and headed home.

Baseball Players Don't Always Make Good Managers

In about a week, the Washington Nationals—picked by many to reach the World Series before the season started—will finish well behind the New York Mets and miss the postseason altogether. In all likelihood, manager Matt Williams will lose his job over the underperformance. His firing, if it happens, won’t be terribly surprising—he’s well-documented as a terrible tactical manager. But Williams did about as well as could be expected given his history. He had virtually no managerial experience before the Nationals hired him prior to the 2014 season, and his greatest asset was perhaps being an exceptionally good player years ago. Given that Williams wasn’t hired for his managerial know-how, his poor performance says more about the team who hired him than it does about Williams himself.

Related Story

Quite obviously, “once played baseball well” isn’t a qualification for management; playing and running a team are unrelated skill sets. In virtually any other industry, hiring a relative novice to command the nine-figure payroll of a franchise valued at over a billion dollars would be malpractice. In Major League Baseball? It’s commonplace. In an era where data analysis is more important than ever to on-field success, the practice of hiring managers like Williams is especially damaging.

When Michael Lewis released his 2003 book Moneyball, a chronicle of the successful moves and analysis performed by the cash-strapped 2002 Oakland Athletics, it marked a major milestone in baseball analysis, known as sabermetrics. Although many of the book’s lessons were well-known for years within the analysis-focused community, Moneyball popularized sabermetrics and gave it enough credibility to become part of all MLB front offices. Indeed, teams that don’t embrace advanced analytics suffer—the last-place Philadelphia Phillies, who only recently committed to a greater focus on analytics, have long been laggards in this field.

Yet Moneyball itself is really only notable for the credibility bump, not for what it taught. Many of the tactics employed by the 2002 A’s were derived from Bill James’ Baseball Abstract publications of the late ’70s and ’80s. Clearly, the field of baseball research has evolved since then—especially when it comes to measuring player defense. It’s easy to agree on the definition of a .300 hitter (someone who gets a hit in 30% or more of their at bats). It’s far harder to agree on what a good team defense, or even a single good defender looks like. Not every defensive blunder involves dropping the ball or making a wild throw. Some miscues aren’t even notable—consider a slow-footed outfielder versus a fast one: both might never drop a ball, but the fast outfielder will reach more balls and thus have more chances than his slower counterpart. This is a gross oversimplification—in many cases speed is only a small component of defense; a player who takes a straight route to the eventual landing spot of a ball can make up a speed gap versus a player who takes a more circuitous route.

All of which is a long way of saying “it’s complicated.” And if the complexity weren’t frustrating enough, getting a clearer sense requires numerous data points—enough that it’s virtually impossible to structure it in a way that’s useable and downloadable to laypersons. Yet there’s no question that this information is useful to the analysts and statisticians employed by MLB teams. The Pittsburgh Pirates, resurgent after two decades of losing, have their own analyst that travels with the coaching staff. (For those who enjoyed Moneyball but want a refresh, Big Data Baseball is a good choice.)

A great deal of work goes into forming a baseball system capable of having its big-league club qualify for the postseason. Yet all of that work is wasted when the field manager ignores it and instead manages by gut feeling. One could argue that the Kansas City Royals lost (and the Giants won) the World Series last season on the back of a single managerial decision in Game 7. Royals manager Ned Yost managed as if there were a Game 8 and held back from using his dominant bullpen despite his starting pitcher struggling. Meanwhile, Giants manager Bruce Bochy immediately removed his own struggling starter and eventually used his best pitcher—starter Madison Bumgarner—to hold the Royals at bay in the season’s final innings. It was a high-visibility move with obvious consequences, yet “use your best pitchers to attempt to win in the postseason” is still somehow a controversial tactic.

Despite the preponderance of useful data and the potential for a non-savvy manager to render it useless, most MLB managers are former players. Contrast this with the NFL, NBA, and NHL, where fewer than half of all head coaches are former players. These sports, by and large, recognize that a managerial or head coaching role is too important to assign to someone whose only success came when playing.

Why is MLB so different from its other major counterparts? There doesn’t seem to be a very clear answer. It may be a function of legacy—MLB is a much older league than its counterparts, and transitioning from the field to the dugout became ingrained in the league’s culture. (Yet the NHL and NFL formed at roughly the same time and clearly have very different hiring practices from one another.) And in all cases, the sports played in each league have dramatically evolved over time. No one would confuse a 19th-century baseball game for one played today, Conan O’Brien’s attempts notwithstanding. Or it may be because baseball has a distinct position—catcher—which is regarded as more cerebral than other positions and thus creates the perception of grooming players into managers. Whatever the reason, MLB has clearly been slower than its counterparts in moving away from using playing experience as a proxy for managing experience.

Even today, the sport doesn’t seem to be learning its lesson. A recent article by FOX Sports’ CJ Nitkowski (himself a former player) points out numerous managerial candidates with no previous experience being considered for 2016 hires. Yet the article highlights current managers with no experience either: Mike Matheny, Robin Ventura, Walt Weiss, Craig Counsell, and Brad Ausmus. If one wanted to make a case that managerial experience isn’t a prerequisite for success, this is an awfully strange list of examples to make that case. Of those five managers, all but Matheny oversee teams that have lost far more than they’ve won. Two of those five manage clubs in last place in their division; two more are next to last. Ausmus is likely to be fired at the end of the season. Even Matheny, the manager of the Cardinals, seems to win in spite of his inexperience even while his blunders are well-chronicled.

Certainly, even a great tactical manager is limited by the talent he’s able to put on the field. Given the injuries, age-related decline, and general lack of talent on the rosters of many of these managers’ teams, you’d be hard-pressed to claim a different manager would’ve gotten appreciably different results. Data analysis and good use of data almost certainly can’t take a team from last place to first.

In virtually any other industry, hiring a novice to command the 9-figure payroll of a franchise valued at over a billion dollars would be malpractice.But baseball is a sport played at the margins. Given that the Pirates and Cardinals are currently locked in a dogfight for their division title, that the Pirates manager is arguably more receptive to analytics than any other manager, and that Matheny is rather lesser regarded, managers may well make the difference in this instance. As shown previously, managerial maneuvers absolutely make a difference in the postseason, where a bad decision is magnified due to the small sample of games—there’s simply no time for the talent of a roster to normalize away from the impact of bad managing.

To be sure, managing a baseball team isn’t simply done on spreadsheets: Like any managerial position, it requires people skills. Someone with an analyst background may transition poorly to the dugout. The Pirates manager who uses analytics, Clint Hurdle, is a former player. Being a former player should by no means disqualify a potential candidate, but neither should it augment a candidacy: A manager’s ability to use the information his team gives him is in no way informed by how many home runs that manager hit during his playing days.

The solution to solving the conundrum of bad managerial hires may lie in separating the roles of “clubhouse manager” and “in-game tactician.” NFL head coaches, in many cases, focus on actual managerial tasks while ceding offensive and defensive decisions to their respective coordinators, for example. It’s not unreasonable to believe that an MLB team could enjoy similar success with such a division of labor. If MLB teams hope to keep up with the rapid advancements in understanding on-field success that data analysis offers, they cannot continue to use a managerial candidate’s baseball card as his resume.

Choose Your Own Adventure: HBO Edition

Soon, HBO audiences might be able to take part in a project that allows them to control what happens in the story. Deadline reports that the show is an “experimental film” called Mosaic that ties into an app that allows the audience to pick the ending. Variety reports that the project will shoot many variations of the script, with viewers ultimately choosing which version ends up on TV.

The project is reportedly led by the Oscar-winning director Steven Soderbergh, who’s no stranger to working with HBO—he’s currently the auteur behind the early-1900s medical thriller The Knick on Cinemax, which is owned by the network. He also directed the HBO film Behind the Candelabra and helped produce the Edward Snowden documentary Citizenfour for HBO Films.

“I believe the good people at HBO are genuinely enthusiastic about Mosaic for two reasons: First, it represents a fresh way of experiencing a story and sharing that experience with others,” Soderbergh said in a statement quoted by Variety. “Second, it will require a new Emmy category, and we will be the only eligible nominee.”

An HBO spokesperson declined to comment on the reports.

Television fans can be a riotous, opinionated bunch, and thus, you could argue, they’ve had a say in their programs for years. But this project would be somewhat unprecedented. The pay-TV channel has proven it’s willing to experiment and innovate (Soderbergh’s The Knick being a prime example), but this is experimentation on a whole other level.

“It will require a new Emmy category, and we will be the only eligible nominee.”The 1985 cult film Clue famously allowed its viewers to pick one of three endings (Ending C is the best one, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise). A recent episode of the CBS show Hawaii Five-0 (a remake of the 1970s series of the same name) allowed viewers to vote online as to how the episode would end. The format has also been tried several times on reality TV shows. But, in general, it’s fairly untrodden territory, especially for a prestigious channel like HBO. The company won 14 Emmys last week—10 more than any other network.

The project seems like it could be a natural fit for the company’s new standalone streaming service, HBO Now. While the product appears successful—both in terms of Apple App Store revenue and what little we know about its subscriber numbers—it still suffers from some brand confusion with HBO’s other streaming service, HBO Go, which is merely the online component given to the channel’s cable subscribers. The two services house the same content.

HBO performed some clever marketing to perhaps clear up that issue, when host Andy Samberg shared his HBO Now password with the world during the Emmys broadcast on Fox last week. Mosaic may end up being a similar stunt, perhaps meant specifically to be consumed on HBO Now, an Internet platform that could give the film a chance to experiment with some interesting types of interaction with its audience.

September 25, 2015

FIFA Unraveling

The Swiss attorney general’s office announced Friday it has opened a criminal investigation into Sepp Blatter, the long-time president of FIFA, soccer’s governing body.

Blatter faces allegations of criminal mismanagement and misappropriation during his presidency. According to the attorney general’s office, the allegations center on a contract Blatter signed with the Caribbean Football Union in 2005.

“[T]his contract was unfavorable for FIFA,” the office said in a statement. “[T]here is as suspicion that, in the implementation of this agreement, Joseph Blatter also violated his fiduciary duties and acted against the interest of FIFA and/or FIFA Marketing & TV AG.”

Jack Warner, the president of the Caribbean Football Union at the time, is fighting extradition from Trinidad and Tobago to the United States. Warner was indicted by U.S. prosecutors in May in a multinational corruption investigation that targeted some of the most influential figures in global soccer. He and 13 other FIFA officials face charges of bribery, racketeering, and money laundering in the U.S. in relation to an alleged conspiracy to rig the World Cup host-selection process.

“Additionally, Mr. Joseph Blatter is suspected of a disloyal payment of CHF 2 Mio. to Michel Platini, President of Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), at the expense of FIFA, which was allegedly made for work performed between January 1999 and June 2002 ; this payment was executed in February 2011,” the Swiss attorney general office’s statement said.

Platini, a former French soccer great, is among the candidates to replace Blatter as FIFA’s president in February. The Swiss attorney general’s statement said Platini “was asked for information” in connection with the investigation into Blatter. The Swiss authorities also said they searched FIFA’s offices Friday and seized data from Blatter’s office.

FIFA commands tremendous financial resources and international clout. Blatter sat at the center of the web of regional and continental fiefdoms that shape the world’s most popular sport for more than 17 years. Corruption allegations dogged various FIFA officials throughout his tenure, and as recently as last week, but Blatter endured, aided by his mastery of the organization’s election processes and his dispensation of patronage to smaller, far-flung national soccer organizations that backed his reign.

That reign ended June 2, days after his re-election, when the U.S. indictments were announced. Blatter resigned the presidency and called for a new extraordinary election to be held. He continues to hold the office until that vote, which is expected to take place in February 2016.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower