Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 335

September 30, 2015

What's the Matter, Whole Foods?

Earlier this week, Whole Foods announced it would lay off 1,500 employees as the upscale grocery chain aims to save money and lower its prices. On the same day as the announcement, Whole Foods co-CEO Walter Robb told the crowd at a Fortune conference the entire food industry is in the midst of a “tectonic shift” as organic food goes mainstream.

That’s a pretty breezy explanation from the co-head of a company whose shares have fallen about 38 percent this year. It’s true that Whole Foods’s storied growth has been undercut by all the grocers muscling in on the company’s turf. As Helaine Olen noted in Slate:

Once an upstart, Whole Foods is now so successful that it’s spawned its own competitors. A decade ago, organic and other food like gluten-free items were considered specialty products. Whole Foods could charge high prices, because many of their customers were choosing between Whole Foods and … Whole Foods. Now Walmart carries the organic Wild Oats line of food.

But as the market for organic food has grown, there are other reasons why ever-loyal consumers have become less apt to walk down the aisle in search of powdered vinegar. Items like vegan teethers, ornamental kale, and the short-lived asparagus water—infamously, a $6 bottle of water with three stalks of asparagus inside—have buoyed the troubling “Whole Foods-Whole Paycheck” reputation.

And even if you are among the lucky many who don’t blink at the prices or perhaps buy into some dubious aisle-side huckstering, it certainly doesn’t help that the company has been repeatedly brought to task for overcharging customers.

In 2014, California regulators fined Whole Foods $800,000 following a year-long investigation into its pricing. More recently, the company was accused of “systemic overcharging for pre-packaged foods” with hundreds of violations logged in its New York City stores. Inspectors from the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs called it “the worst case of mislabeling they have seen in their careers.”

For a company whose noble ethics are baked into its marketing materials, this is particularly bad news. But, despite having lost part of its footing in a market that it pioneered, Whole Foods is both still growing and finally taking action that goes beyond laying off 1.6 percent of its workforce.

To combat the “whole paycheck” perception, the company is angling to lower prices as well as launch a chain of ostensibly millennial-friendly stores with cheaper “curated” selections. It also has invested in technology and apps to streamline the shopping experience.

It’s also trying new ways to market itself. As we noted in June, Whole Foods recently introduced a new food-rating system called “Responsibly Grown” in its stores. The classification system is controversial because it undercuts the organic designation, but it also highlights less pricy, non-organic offerings.

One way it can truly win is by continuing to do what it does especially well: Providing solid-paying work and above-average benefits to its employees. Even if that ultimately means laying some off, presenting relatively generous severance packages is a good thing, too.

The Continuing Battle for Kunduz

Afghan forces, aided by U.S. airstrikes, failed to retake the city of Kunduz that was captured by the Taliban on Monday—the militant group’s biggest prize since it was ousted from power following the U.S.-led invasion of 2001.

U.S. planes struck Taliban targets near the city’s airport, driving the militants back. The airport is where government troops and civilians fled after the Taliban overran the city. The Afghan government has sent reinforcements to Kunduz, the capital of the province of the same name. A NATO spokesman said special forces from the military alliance were on the ground in Kunduz, advising their Afghan counterparts. Agence France-Presse reported the forces were from the U.S., Britain, and Germany.

The New York Times quoted Afghan government officials as saying U.S. special forces “headed out toward the city with Afghan commandos.” Their role there wasn’t clear, but the Times added: “[A]t least one American operation in the city of Kunduz failed. An Afghan security official, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said that American forces had sought to resupply a group of beleaguered Afghan soldiers trapped in an ancient fortress north of the city.”

The progress of government reinforcements has been slowed by Taliban ambushes in the roads leading up to the city, as well as landmines.

President Ashraf Ghani, who marked one year in office on Tuesday, has vowed to take Kunduz back, but the loss of the city is an embarrassment to his effort to bring security to Afghanistan a year after U.S. and NATO troops left the country.

On the other hand, the capture of Kunduz is a major victory for the Taliban, a group that might have been forgotten in the West because of competition elsewhere from organizations such as the Islamic State that might espouse a similar brand of Islam, but are even more brutal in their tactics, and even more successful in their military achievements. The Taliban has also been riven by factionalism since the death of its leader, Mullah Muhammad Omar, was confirmed in July, but the capture of Kunduz is likely to bolster Mullah Akhtar Mansour, its new chief.

But to those in Kunduz province and the city itself, the Taliban’s stunning victory wasn’t unexpected. The Taliban has besieged the northern city, an important transportation hub, for months, and local officials say they repeatedly asked Kabul to send reinforcements, which never came.

The militant group already controls many districts in the province. Now, its control of the city—and the Afghan pushback—is exacting a toll on Kunduz’s civilians.

It’s unclear how many people are dead or injured, but local medical officials say they are overwhelmed. The UN has condemned the fighting and urged “all parties to the conflict to uphold their obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law to protect civilians and to take all feasible steps to prevent the loss of life and injuries to civilians.”

September 29, 2015

Nicki Minaj, Person

When I first saw the news that a scripted TV show was being made about the rapper Nicki Minaj, my first thought was that it might be on Cartoon Network. You can envision it, right? The various personaities Minaj has constructed through her music—the unhinged Roman Zolanski, the brash Nicki Lewinski, the sweet Harajuku Barbie—rendered in zany, Anime-inflected colors, like Samurai Jack or The Powerpuff Girls or the “Only” video, with fewer Nazi overtones.

But the show that’s actually being made is a live-action sitcom on ABC Family that “will focus on Minaj’s growing up in Queens in the 1990s with her vibrant immigrant family and the personal and musical evolution that lead to her eventual rise to stardom,” Deadline’s Nellie Andreeva reports. Kate Angelo, who penned the 2014 Cameron Diaz/Jason Segal comedy Sex Tape, will write it; Minaj will executive-produce and act in it.

The show, no doubt, represents another front in Minaj’s efforts as “a business, woman,” sitting alongside holdings in perfume and alcohol that keep her on the Forbes annual list of wealthiest rappers. It’s also a fairly on-brand move for ABC Family, whose other programming—including the warmly reviewed lesbian family drama The Fosters (executive produced by another American Idol judge, Jennifer Lopez) and the wildly popular mystery series Pretty Little Liars—appeals to young people, especially women.

But the show also might have more intangible benefits for Minaj and pop culture in general. With her extravagant costumes and alter-egos and crazy voices, Minaj was often initially grouped alongside Lady Gaga, part of a boom of self-consciously weird divas who rarely talked about their personal lives. The otherworldliness was part of her appeal, a high-concept riff on the fact that she was a genuinely novel presence in mainstream music: an aggressive female rapper who also unabashedly embraced feminine dance pop. In the process, she provoked an all-sides backlash that, to lot of pop observers, seemed to go beyond what most stars received. Rap gatekeepers accused her of being fake, a perversion of the genre; criticism from other quarters focused on her abrasiveness and often included coded language about her body (or not-so-coded—one otherwise measured respondent to the Quora entry asking “Why do people hate Nicki Minaj so much?” offers that he’s “not a big fan of her face”).

Lately, though, Minaj has started to shed much of the glitter and rubber. Her newest full-length, The Pinkprint, basically abandoned her multiple-personality shtick and instead served up some surprisingly tender songs about her upbringing, her love life, and her birth country (Trinidad and Tobago). Rather than beginning with a party-minded banger, it opened with the confessional ballad “All Things Go,” which addressed a marriage proposal from a decade ago, the murder of her cousin, and recent difficulties she’s had with her relatives.

She can remind the public that superhuman performers are, by definition, still human.At the same time, she has become increasingly overt in her politics; Minaj has been on a mission not only to humanize herself, but to stand up for the huge portions of humankind who resemble her in various ways.The Internet-breaking “Anaconda” video, for example, was a sexual tease that was also meant to flip the script on some of society’s racial and body-type biases, at least to hear Minaj tell it on Twitter. When she called out Miley Cyrus for trash-talking her in the press, it was a very simple statement: What’s good—a.k.a., I’m here, I see you and I hear what you’ve said about me. I’m a person.

Now, after the announcement of the ABC Family show, the hashtag #YoungNicki is trending, with social-media users suggesting various actors who could star as the young immigrant Onika Maraj. It’s an example of the power that a show like this can have, asking girls to envision themselves growing up to be someone with both Minaj’s business success, cultural power, and uncompromising vision (fans have long known she’s been after this: She raps on “I’m the Best” that she’s “fighting for the girls who never thought they could win”). In the process, she can also remind the public that superhuman performers are, by definition, still human.

Chicago's Problem With Gun Violence

Over the weekend in Chicago, the Cubs clinched their first playoff berth since 2008 despite losing three straight games. The University of Chicago prepared to host a campaign event for Bernie Sanders, who attended the school in the 1960s. And for the second straight weekend, more than 50 people were shot in the city. The Chicago Tribune reports:

The toll included four men killed and at least 53 people wounded between Friday evening and early Monday morning, according to police. Last weekend, nine people were killed and at least 45 were wounded.

The violence, which has become bleakly commonplace, didn’t end Monday. The city has endured 2,300 shootings so far this year—an average of more than eight per day and 400 more shootings than at this point last year. And, America’s third-largest city continues to contend with a 21 percent increase in homicides. On Monday evening, an 11-month-old boy was wounded in a south-side shooting that also killed his pregnant mother and his grandmother.

“In a second, two generations of that child’s family were wiped out.”“In a second, two generations of that child’s family were wiped out,” Eugene Roy, a Chicago deputy chief of detectives, told reporters. (A total of six people have been killed and eight others have been wounded since Monday morning.)

The violence is widely seen to stem from a deadly combination of gangs and illegal guns. Responding to Monday’s shootings, Mayor Rahm Emanuel squared his focus on gangs.

“Wherever you live, you should be able to get out of your car and go to your home. … it’s time that our criminal justice system and the laws as it relates to access to guns and the penalties for using ’em reflect the values of the people of the city of Chicago,” he said.

In June, Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy told PBS that police have confiscated more illegal guns in Chicago than Los Angeles and New York City combined in the first half of the year. Drug trafficking is also a major factor, with as much as 80 percent of illegal drugs in the city estimated to come from Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s Sinaloa cartel.

Indeed, following each of his escapes from prison, Guzman was given the title of “Public Enemy No. 1” in Chicago. He remains the first person to be given that designation since Al Capone in 1930.

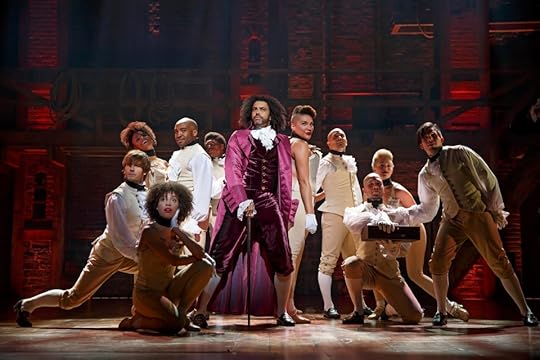

How Lin-Manuel Miranda Shapes History

Art has a long tradition of shaping public perceptions of history. Shakespeare transformed Richard III, a brutal monarch in a typically brutal time, into a physically-deformed, Machiavellian tyrant. Leon Uris romanticized the story of Israel’s founding for a generation of Americans with Exodus. Evita immortalized a controversial Argentinian icon as a cynical, power-hungry entertainer. Now, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton has the opportunity to change the way people consider one of the Founding Fathers and the era he lived in.

Related Story

How Hamilton Recasts Thomas Jefferson as a Villain

Miranda is the writer, composer, and star of Hamilton, as well as the newly minted recipient of a “genius” grant from the MacArthur Foundation. His show follows the trajectory of Hamilton’s life from an orphaned upbringing in the West Indies to his death at the hands of Aaron Burr. Hamilton’s core elements—its hip-hop and R&B-inspired music and its racially diverse cast—are geared specifically towards making history as relatable as possible. “This is a story about America then, told by America now,” Miranda explains, “and we want to eliminate any distance between a contemporary audience and this story.”

Hamilton, then, has the potential to strongly influence the way Americans think about the early republic. For one thing, as my colleague Alana Semuels writes, it understands Thomas Jefferson to be a deeply flawed individual. It presents an American history in which women and people of color share the spotlight with the founding fathers. The primarily black and Hispanic cast reminds audiences that American history is not just the history of white people, and frequent allusions to slavery serve as constant reminders that just as the revolutionaries were fighting for their freedom, slaves were held in bondage.

Perhaps the most significant lesson the show might teach audiences, and one that has particular relevance today, is the outsized role immigrants have played in the nation’s history. Alexander Hamilton was an immigrant—a fact that Miranda repeatedly emphasizes throughout the show—and the musical also prominently features the Marquis de Lafayette, a French nobleman who played a crucial role during the revolutionary war.

I spoke with Miranda last week about the process of translating history onto the stage; the ways in which Hamilton could alter our perception of history; and the role artists play in shaping historical narratives. An edited and condensed transcript of the conversation follows.

Delman: What do you make of the idea that the show could become the basis for how many people understand the revolutionary period and Alexander Hamilton? In the same way that Evita is the way most people see Eva Perón, and Shakespeare doomed Richard III as a villain.

Miranda: That’s so interesting you say that, because I’m theater people, and theater people, the only history they know is the history they know from other plays and musicals ... So to that end, I felt an enormous responsibility to be as historically accurate as possible, while still telling the most dramatic story possible. And that’s why Ron Chernow is a historical consultant on the thing, and, you know, he was always sort of keeping us honest. And when I did part from the historical record or take dramatic license, I made sure I was able to defend it to Ron, because I knew that I was going to have to defend it in the real world. None of those choices are made lightly.

Delman: Obviously the show is adapted from Chernow’s biography. Was that your first exposure to Hamilton, the founding fathers, and the revolutionary period in general?

Miranda: Yes. I wrote a paper on Hamilton in high school. And it was just about the duel. That’s what most people focus on. And that’s really all I knew when I grabbed Ron’s book off the shelf. The sort of thinking that went into it was, “This will have a good ending.” Ron’s book was a really acclaimed, well-reviewed book and biography, and I was just looking for a good biography to read on the beach.

Delman: How did Chernow keep you honest?

Miranda: I think the strength of his book is he approaches his history novelistically. It’s always historically accurate, but he is able to keep a through-line of relentlessness that I think characterizes Hamilton as a person, and I was able to plug into that. I didn’t know Hamilton was an immigrant, and I didn’t know half of the traumas of his early life. And when he gets to New York, I was like, “I know this guy.” I’ve met so many versions of this guy, and it’s the guy who comes to this country and is like, “I am going to work six jobs if you’re only working one. I’m gonna make a life for myself here.” That’s a familiar storyline to me, beginning with my father and so many people I grew up with in my neighborhood. So ... every play or work of fiction kind of has to start with you identifying a character and saying, “I know this guy. I could write that guy.” And I kind of ran with that.

Delman: Did you talk to or consult with any other period experts, or bring in outside opinions other than Chernow’s?

Miranda: I read a lot of outside opinions. I read The Heartbreak of Aaron Burr by H.W. Brands. Burr was important for me to get because I knew he was narrating, and there’s not a lot of stuff about Burr, or there is, but the tone is super defensive—rightfully so, because he’s the Richard III of American history—and so the people who write about him, choose to write about him, often just write from this place of, “No no no no no, you don’t understand!” Which is not always the most compelling reading. So I was really looking for facts and figures and ways for me to understand him, and H.W. Brands was very helpful in that respect because he largely focused on the family and that’s a great way into anyone, to have empathy with anyone. And then, Joanne Freeman’s book Affairs of Honor. She’s since become a friend, but Affairs of Honor was great in terms of understanding the dueling code, and also her collected book of Hamilton’s writing that she published through Yale Press, which was sort of my touchstone. You know, anytime I was in the wilderness I could go back to what Hamilton wrote and kind of figure it out from there.

“I didn’t know Hamilton was an immigrant, and I didn’t know half of the traumas of his early life. And when he gets to New York, I was like, ‘I know this guy.’”Delman: What do you feel is your responsibility as a playwright and a storyteller when it comes to telling this kind of story?

Miranda: My only responsibility as a playwright and a storyteller is to give you the time of your life in the theatre. I just happen to think that with Hamilton’s story, sticking close to the facts helps me. All the most interesting things in the show happened. They’re not shit I made up. Honestly, I think of the quote, Burr’s final quote in the show, “The world was wide enough for both Hamilton and me.” That’s a real letter from Burr later in his life. It’s a reference to an author he likes—if I had read something more and Voltaire less—

Delman: Sterne and Voltaire.

Miranda: Yeah, “Sterne more and Voltaire less, I might have realized the world was wide enough for both Hamilton and me.” That’s a heartbreaking thing. Even though in Burr’s actual telling it’s kind of a joke, it’s still a heartbreaking sentiment. So I guess my answer is, my job as a writer is to give you the most interesting and dramatic tale possible, and Hamilton’s life affords a unique opportunity for me to do that without straying from the historical record. I got a sneak preview of the world’s reception of this, because I performed that first song at the White House, and that thing’s been online since the fall of 2009. And I’ve seen history teachers use it in their classes. So I’m just very excited that the whole thing is out in the world, because I knew that making it come alive—Ron did it for me, and I think the secret sauce of this show, at least in the writing—leaving aside the unbelievable production Tommy Kail and Andy Blankenbuehler and Alex Lacamoire have put together—I think the secret sauce in the words is my enthusiasm for learning all this stuff in the first place. It’s like that scene in Like Water for Chocolate, where Tita cries in the recipe and suddenly everyone is eating the wedding cake but they’re all bawling. Well if you’re crying listening to the cast recording, it’s because I cried first writing it. My tears are all up in this recipe.

Delman: You talked about seeing people use the opening song in classrooms—how do you think your interpretation of Hamilton and this period will shape the way people understand the man and his era?

Miranda: Well, I think it’s a particularly nice reminder at this point in our politics, which comes around every 20 years or so, when immigrant is used as a dirty word by politicians to get cheap political points, that three of the biggest heroes of our revolutionary war for independence were a Scotsman from the West Indies, named Alexander Hamilton; a Frenchman, named Lafayette; and a gay German, named Friedrich von Steuben, who organized our army and taught us how to do drills. Immigrants have been present and necessary since the founding of our country. I think it’s also a nice reminder that any fight we’re having right now, politically, we already had it 200-some odd years ago. The fights that I wrote between me and Jefferson, you could put them in the mouths of candidates on MSNBC. They’re about foreign relations; they’re about states’ rights versus national rights; they’re about debt. These are all conversations we’re still having, and I think it’s a comfort to know that they’re just a part of the more perfect union we’re always working towards, or try to work towards, and that we’re always working on them. You know, we didn’t break the country; the country came with a limited warranty, like it was never perfect. It was never perfect, and there’s been no fall from grace. I find that heartening, honestly, that we’re still working on it.

“My job as a writer is to give you the most interesting and dramatic tale possible, and Hamilton’s life affords a unique opportunity to do that.”Delman: It’s interesting that Hamilton, when he reads the constitution in its fullness, is kind of ambivalent about it, but still decides to make himself its strongest defender and fights and fights for it, knowing that it’s not perfect.

Miranda: Yeah, it’s not perfect. Hamilton pitched his own version, and the fact that he did that gave him a bad reputation for the rest of his career. They’d say, “Well, did you hear Hamilton’s version at the Constitutional Convention—this asshole?” But the Federalist Papers are the best Talmudic discussions on the original intent of the founders that we have, because they were written around the same time. If you want to look at what the founders intended, you have to read the Federalist Papers. And some of them aren’t great—Madison got stuck with defending slavery. But they are the commentary by the people who were there. You know, when you study Gospels in Christianity—I took a great class on this at Wesleyan—you know, there are scholars who, it’s not about the Christian tenets but it’s about, “Alright, which Gospel was written close to the time historical Jesus was alive? Which sentences agree over the four Gospels and, in researching all this, can we get close to what the actual thing historical Jesus maybe said?” That’s why the Federalist Papers—you know, I had to read them all—they’re fascinating to me. And the lawyers—my wife is a lawyer—lawyers really love that part because they still draw on that. We still look to that for sign of intent, and I think that’s great that a parallel document exists.

Delman: What do you think is the role of artists in either shaping our national history or our sense of history at large?

Miranda: I think it’s entirely self-participatory. Here’s the thing about artists—their job is to fall in love for a living. Like, you could commission me to go write a historical fiction, a historical musical. If I’m not in love with it and I don’t know how to get myself into the characters, you’re going to be bored to tears by whatever the fuck I write. You can’t assign falling in love, because it takes falling in love to write a musical. I’ve been writing this thing for seven years. That’s longer than pretty much every relationship I’ve ever been in, except for my wife. And that’s what it takes—waking up and knowing you’ve still got challenges within it, and how are you going to crack this problem, and how are you going to compress this section. You’ve got to be able to go into that work lovingly, willingly. So it’s very hard to dictate what the artist’s role should be. I’m lucky that Hamilton grabbed me. I feel lucky. But it depends on what I fall in love with enough to put in the time and work to write, because it’s hard work. And it should never feel like work. When you’re in love, it doesn’t feel like it.

Mullet Over: The Lonely Brilliance of MacGyver

Here is the plot of the “Trumbo’s World” episode of MacGyver, first aired in 1985 and summarized today by Amazon Video:

Deep in the primitive Amazon jungle, MacGyver teams with an entomologist friend and a local plantation owner to battle a horde of invading ants.

Yes. YES. This—the casual use of the word “primitive,” the fact that the foe faced here is “a horde of invading ants”—is classic MacGyver. The Amazon-on-the-Amazon-episode summary may not be fully accurate (Mac’s friend, in this case, is actually an ornithologist), but it gets to the heart of the show that was, in so many ways, quintessentially ’80s. The show that birthed weird spinoffs and loving satires (MacGruber!) and only-pseudo-ironic memes and, of course, its very own verb. The show that found a new way to insist to a generation of viewers that knowledge is power.

MacGyver premiered 30 years ago today, in 1985, on ABC. It would run for seven seasons, ending in May of 1992. The show did well, ratings-wise, but not spectacularly; it was one of those series that took on a kind of mythic status that has kept it alive in the culture far after it went off the air. MacGyver is, to be clear, a pure delight to watch today, and only partially because of Richard Dean Anderson’s epic man-mullet. It is exceptionally cheesy. It is occasionally riveting. It is the 1980s, incarnate. It is like putting on a 45-minute-long pair of legwarmers.

And yet. I am extremely sorry to report that MacGyver has not, all else considered, aged well.

I’m also surprised to report it! My early childhood roughly coincided with MacGyver’s run on network TV; in my vague memory, MacGyver is the ultimate non-super superhero—ultimate because his superpower is, yes, his mind. MacGyver, ever resourceful and armed with a seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of engineering and chemistry, can make dynamite out of … well, pretty much anything. He can save himself from an avalanche using a jury-rigged straw; he can track down a “Yeti” in the Canadian wilderness using only the ground; he can get himself out of pretty much any scrape imaginable. MacGyver is also, as a kind of problem-solver-for-hire, almost magically omnipresent, effortlessly hopping around the world to help those in need of his services. (You shudder, today, imagining his carbon footprint.) He’s Olivia Pope, basically, except his goblet of red wine is a weaponized stick of deodorant.

“MacGyver, what do you do by profession?” one of his foes asks him.

“I, uh, move around,” comes the reply.

It turns out, though, that while Angus “Mac” MacGyver may well be the heroic supernerd I recall from my childhood, he is also, more simply, a nerd. (It’s a running joke throughout the series that no one is exactly sure what his profession is, technically—what “uh, moving around” actually entails. Is MacGyver an engineer? Is he a chemist? Is he a walking, talking Swiss Army knife sent from the future to save humanity, one adventure at a time? “I’m sort of a repairman,” Mac tells the little brother he volunteers with, in the pilot episode of the show. That seems to sum it up best.)

MacGyver also narrates the beginnings of episodes with a distinctly aw-shucks tone, Doogie Howser/Kevin Arnold-style. In the “Trumbo’s World” episode, Mac confides to the audience:

Oh, what a life I lead: riding the rapids in the Pyrenees Mountains one day, and the next crossing half the world to help out a friend with a very weird problem in a very strange part of the Amazon. I think I should get an unlisted phone number!

Wah-wah. You get the sense that, were MacGyver around today, he’d definitely be rocking some dad jeans along with his MacMullet.

But the problem here isn’t really MacGyver. It’s the show itself that reads, ultimately, as outdated—and not just because of the hyper-synthed score that plays whenever MacGyver Encounters Danger. The problem is, instead, precisely the thing I remember so fondly about the show: MacGyver’s (super)man premise. One man, doing everything for himself, being everything to everyone! One man, whose damsel in distress is basically the whole world!

MacGyver’s format—each episode a self-contained puzzle—is familiar today from shows like Sherlock and House and pretty much every procedural that has ever aired on American television. What makes MacGyver different, though, is how much the show relies on the single guy—armed with knowledge and a nail file—to solve the puzzle. Even House has his diagnostic team. Even Sherlock has his Watson. MacGyver may occasionally be saved by his best friend and boss, Pete Thornton; he may occasionally enlist the services of an “entomologist friend” and “a local plantation owner” as he solves the problems a particular episode throws his way. For the most part, however, everyone relies on him. He—well, the show that gives him life—is everyone’s savior.

You could probably read some end of men/demise of the patriarchy/death of adulthood anxiety into all of this. You could definitely read some White Savior Industrial Complex in it. For the most part, though, MacGyver’s premise, today, just reads as boring. Without the help of other people—without, essentially, teamwork—MacGyver’s many episodes resemble action movies stripped of everything but the action scenes. There’s a lot of drama. There are a lot of explosions. (Though, notably, very little gunfire: MacGyver, famously, eschewed the weapons, looking instead for relatively non-violent solutions to his weekly life-or-death dilemmas.) There are a lot, in general, of “eeee, are they gonna make it?” tensions. Here, for example, are more of Amazon’s Season One episode listings:

The Golden Triangle

While retrieving a poison-filled canister from a crash site in Burma, MacGyver is forced to take on a powerful drug lord when he is mistaken for a narcotics agent.Thief of Budapest

In Budapest, MacGyver obtains vital microfilmed information hidden inside a watch. But when the watch is stolen, MacGyver has to find the thief: a young Gypsy girl.The Gautlet

MacGyver goes up against an entire army when he helps an American journalist escape across the border of a South American dictatorship.The Heist

A Virgin Islands casino owner steals $60 million in diamonds. MacGyver and an American senator’s daughter plot to steal them back from the casino’s impenetrable vault.

Exciting, right? And yet, with all the adventure—breaking into an “impenetrable vault,” with a “senator’s daughter!”—there is very little time left over for character development, or meaningful dialogue, or relationship-building. Romances, friendships, life-and-death stakes—all of them are contained in a single episode. Outsiders, here, are largely expendable. This is the Great Man theory of adventure, basically.

There’s nothing overtly objectionable about that. It is how many TV shows operate. But MacGyver embraces its own insistent loneliness to an absurd degree. And that, in turn, makes the whole show feel distinctly retrograde. Today, in an age of television in which even the most lowbrow of sitcoms tend to offer some kind of literary merit, MacGyver sags under the weight of its old-school definition of heroism. It glorifies the single man—the single mullet—while treating other people as victims and saps. It takes the logic of Man vs. Wild, adding supporting characters who exist mostly to be saved and then forgotten. Which is too bad, because other people can be not only entertaining, but helpful! Even, and especially, when you’re fighting killer ants.

The Philosophy of Selfie

“I’ve observed a general societal decline in kindness to our fellow man,” wrote the blogger Matt Raymond in 2010. “At the same time, our senses of entitlement have seemingly spiked. You can look almost anywhere and witness this unfortunate evolution.”

“As part of the autograph community,” he continued, “I see this all the time.”

The autograph community is what it sounds like, the community whose members collect autographs. Raymond, writing at the website Autograph University, went on to list 10 rules of etiquette for grabbing famous signatures— “Don’t try to graph a celebrity who is with their family,” “Don’t interrupt a celebrity,” “Say ‘please’ and ‘thank you,’” and so on. Manners.

As that post hinted, the autograph was in danger, but more due to technology than “general societal decline.” Last year in the Wall Street Journal, Taylor Swift observed that she hasn’t “been asked for an autograph since the invention of the iPhone with a front-facing camera. The only memento ‘kids these days’ want is a selfie.”

Swift’s remarks sparked a few more online commentaries about diehard fan habits reflecting changes in civilization-wide mores. A few autograph partisans posited that a supposedly urbane practice was being replaced by a supposedly savage one: “The golden rule of autograph-hunting was that you never touched the celebrity; the inescapable law of the selfie is that you’ve got at least to put an arm round them,” wrote The Telegraph’s Christopher Middleton, who called selfie pursuit “as close to human big-game hunting as you can get.”

Now, one of the high priests of selfie culture is grappling with its dark side, or at least its annoying side. In a series of Snapchat videos recorded while on tour in Australia, Justin Bieber has issued what amounts to a white paper on the subject of fan-celebrity-selfie etiquette:

The way that you ask or approach me when you want a photo with me is going determine if I take a photo or not. If I’m walking somewhere or arriving somewhere and you guys are asking to take a photo, if I don’t respond, if I continue just walking, the likelihood is probably that I don’t want to take a photo at that moment. Now, if you start screaming louder that’s not going to make me want to take a photo more.

I want to enjoy the moment just as you are enjoying the moment. But I can’t enjoy it if I don’t feel like there’s any respect given to me at that moment. So if you’re asking kindly, usually the chances are I’ll take a photo, but if perhaps I don’t or I’m in a mood where I’m not trying to take a photo at that moment, please just respect me and just treat me the way you would want to be treated. That’s all. I just want us to be on the same page.

It’s like, why did you travel to see me in the first place—was it really to see me or was it to get that moment of you seeing me so you could tell people about it?

There’s a frightening poignance to that last line, a distillation of the weirdness of celebrity and the weirdness of social-media culture, both of which can mess with the ability to trust in your own relationships. It also puts a fine point on what exactly does change when the currency of fandom goes from physical samples of handwriting to easily shareable digital photos. Fame requires people to be “on” regardless of whether they want to be, to force smiles constantly; a steady stream of selfie requests only amplifies that task. Decide not to play along, and you make headlines, as Kanye West did at the Super Bowl last year:

US Weekly

US Weekly But in other ways, Bieber’s comments just underscore the continuity between autographs and selfies, the ways in which the relationships between fans and famous people will always be fraught and awkward and unseemly for all involved. The list is long of celebrities who’ve made sweeping pronouncements about the circumstances under which plebs may and may not approach them for souvenirs; Rosie O’Donnell reportedly will only sign for kids, as adult signature seekers make her “sad.” And everyone seems to have horror stories. Just this week, in an interview to promote his new show The Grinder, Rob Lowe talked about a nurse reaching over his grandmother’s deathbed to ask Lowe for an autograph; he also said he usually helps coach fans on how to light their selfies with him.

Both living members of the Beatles, the band whose ’60s success set the template for Bieber and all other young male musicians swamped by screaming young women, have declared a no-more-autographs rule in recent years. Reliant as he is on the fervor of his fanbase and on social media in order to sustain (or: relaunch) his career, Bieber has not yet gotten to that point with selfies.

But perhaps it’s coming. This week, tabloids published reports that a Playboy contest participant named Sarah Harris accused Bieber of touching her breast without consent. The incident supposedly arose at a party where Bieber turned down another woman’s request for a selfie, and Harris initially sided with Bieber.

“I said to her, ‘Look babe we’ve kind of been taking photos all night and we’re over it,’” Harris later recounted. “Imagine how he feels — he gets that every single day.”

“After that, Justin thanked Sarah for defending him with a hug and a kiss,” Hollywood Life writes, “which is when he allegedly touched her inappropriately.”

What the FBI Can't Tell Us About Crime

The FBI says violent crime fell again across the nation last year, continuing a two-decade-long downward trend.

The 2014 edition of the Uniform Crime Report released Monday said violent crime dropped nationwide by 0.2 percent. New England saw the sharpest declines, with double-digit falls in New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Outside of the Northeast, the numbers varied greatly: Illinois saw an 8.3 percent decline, for example, while Florida saw reports of violent crime increase by almost 17 percent.

The UCR is the most well-known measure of crime in the United States, but it’s not flawless. FBI Director James Comey, who told reporters in April that it was “ridiculous that I can’t tell you how many people were shot by the police last week, last month, last year,” announced a new initiative Monday to collect more data on police shootings in the wake of high-profile incidents over the past year. But activists warned that police departments would still submit data on a voluntary basis instead of through a desired mandatory system.

As I noted in May, much statistical information about the U.S. criminal-justice system simply isn’t collected. The number of people kept in solitary confinement in the U.S., for example, is unknown. (A recent estimate suggested that it might be as many as 80,000 and 100,000 people.) Basic data on prison conditions is rarely gathered; even federal statistics about prison rape are generally unreliable. Statistics from prosecutors’ offices on plea bargains, sentencing rates, or racial disparities, for example, are virtually nonexistent.

Without reliable data on crime and justice, anecdotal evidence dominates the conversation. There may be no better example than the so-called “Ferguson effect,” first proposed by the Manhattan Institute’s Heather MacDonald in May. She suggested a rise in urban violence in recent months could be attributed to the Black Lives Matter movement and police-reform advocates.

“The most plausible explanation of the current surge in lawlessness is the intense agitation against American police departments over the past nine months,” she wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

Many others have disputed MacDonald’s analysis. Using data from the first half of 2015 from the 60 most populous U.S. cities, FiveThirtyEight’s Carl Bialik wrote that despite an overall increase in homicides, the picture was far murkier than what MacDonald portrayed.

Most of these changes aren’t statistically significant on a city level. Even amid the national upward trend, and in some of the country’s most populous cities, homicides remain, thankfully, a rare event. That means some increases that look large on a percentage basis affect the raw totals only slightly, to an extent that could arise by chance alone. A 20 percent increase in Seattle sounds a lot more significant than an increase to 18 homicides from 15 through Aug. 29. Homicides in Arlington, Texas, through Aug. 31 are down by 50 percent — to four from eight.

Gathering even this basic data on homicides—the least malleable crime statistic—in major U.S. cities was an uphill task. Bialik called police departments individually and combed local media reports to find the raw numbers because no reliable, centralized data was available. The UCR is released on a one-year delay, so official numbers on crime in 2015 won’t be available until most of 2016 is over.

These delays, gaps, and weaknesses seem exclusive to federal criminal-justice statistics. The U.S. Department of Labor produces monthly unemployment reports with relative ease. NASA has battalions of satellites devoted to tracking climate change and global temperature variations. The U.S. Department of Transportation even monitors how often airlines are on time. But if you want to know how many people were murdered in American cities last month, good luck.

ISIS’s Foreign Fighters: Maxime, Peter, and Emilie

The Treasury and State Departments announced Tuesday the designations of 30 individuals and groups for sanctions. The list includes “terrorists and those providing support to terrorists or acts of terrorism,” all accused of operating at the behest of ISIS.

If anything relating to the terrorist group still has the capacity to surprise, it would be the diversity on the two lists. Individuals who were sanctioned on Tuesday hail from places like Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia, but also France, the United Kingdom, Russia, and Indonesia. Some of those named include Sally Jones, a British national who is accused of recruiting women to join ISIS and conduct attacks within the United Kingdom, as well as Maxime Hauchard, Emilie Konig, and Peter Cherif, three French nationals all accused of traveling to Syria to fight with ISIS.

One senior administration official commented that the actions announced Tuesday “highlight the truly global nature of the threat.” However, the selection and timing of the designations also carry a strategic import. With the United Nations in session, the United States is working to fortify a global anti-ISIS coalition.

According to administration officials, the announcements precede both the United Nations’s naming of individuals and groups for sanctions as well as the Leaders’ Summit on Countering ISIL and Violent Extremism, which will take place on the sidelines of the UN on Tuesday.

Corruption Shocks—Shocks!—FIFA

FIFA’s ethics panel has banned Jack Warner, a former executive of soccer’s governing body, for life, citing repeated misconduct.

Warner, a former FIFA vice president, was one of 14 executives the U.S. indicted in May on corruption charges. Warner, who previously served as the president of the Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football—which oversaw the sport in this region—is accused of taking bribes for his vote in the bidding process for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups.

Here’s more from the ethics panel:

Mr Warner was found to have committed many and various acts of misconduct continuously and repeatedly during his time as an official in different high-ranking and influential positions at FIFA and CONCACAF. In his positions as a football official, he was a key player in schemes involving the offer, acceptance, and receipt of undisclosed and illegal payments, as well as other money-making schemes. He was found guilty of violations of art. 13 (General rules of conduct), art. 15 (Loyalty), art. 18 (Duty of disclosure, cooperation and reporting), art. 19 (Conflicts of interest), art. 20 (Offering and accepting gifts and other benefits) and art. 41 (Obligation of the parties to collaborate) of the FIFA Code of Ethics.

Warner has vigorously denied the charges against him, and in the process joined a list of public figures who confused The Onion for fact, claiming the charges against him were part of a U.S. conspiracy against FIFA.

“If the FIFA is so bad, why is it the U.S.A. wants to keep the FIFA World Cup?” he asked in the video, referring to The Onion article headlined: "FIFA Frantically Announces 2015 Summer World Cup In The United States: Global Soccer Tournament To Kick Off In America Later This Afternoon.”

News of Warner’s ban for life comes amid increased scrutiny of soccer’s governing body and its longtime president, Sepp Blatter. FIFA has faced allegations of corruption for years. Those drumbeats became more prominent after the 2018 and 2022 World Cups were awarded to Russia and Qatar, respectively. They were capped in May by a joint U.S.-Swiss operation that resulted in the arrests of several FIFA executives in Zurich.

On Tuesday, Swiss authorities said they would extradite one of those officials, Eduardo Li, the former head of Costa Rica’s soccer federation, to the U.S.

Last week, the Swiss attorney general’s office announced it had opened a criminal investigation into Blatter himself. As my colleague Matt Ford reported:

Blatter faces allegations of criminal mismanagement and misappropriation during his presidency. According to the attorney general’s office, the allegations center on a contract Blatter signed with the Caribbean Football Union in 2005.

To put in perspective FIFA’s clout and the power exercised by Blatter, its chief, consider this from Matt:

FIFA commands tremendous financial resources and international clout. Blatter sat at the center of the web of regional and continental fiefdoms that shape the world’s most popular sport for more than 17 years. Corruption allegations dogged various FIFA officials throughout his tenure, and as recently as last week, but Blatter endured, aided by his mastery of the organization’s election processes and his dispensation of patronage to smaller, far-flung national soccer organizations that backed his reign.

That reign ended June 2, days after his re-election, when the U.S. indictments were announced. Blatter resigned the presidency and called for a new extraordinary election to be held. He continues to hold the office until that vote, which is expected to take place in February 2016.

Swiss officials also alleged last week that Blatter had paid Michel Platini, the head of UEFA, about $2 million. Both Blatter and Platini—a former French soccer great who is among the candidates to replace Blatter as FIFA’s president in February—have denied the charges.

And earlier this month, FIFA suspended its secretary general, Jérôme Valcke, amid allegations he was part of a scheme to sell tickets for the World Cup above their face value.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower