Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 318

October 20, 2015

The Increasingly Confusing Mammogram Guidelines

On Tuesday, the influential American Cancer Society further complicated an already mixed set of recommendations about breast cancer screening by releasing revised guidelines about when women should have mammograms.

According to the new guidelines, the ACS suggests that women at average risk for breast cancer can wait until age 45 to undergo their first mammogram and then alternate years starting at age 55. These revisions buck against what many groups (including the ACS) and cancer awareness initiatives have been recommending for years, namely that women begin screening at age 40 and undergo regular exams by their doctors.

As NBC notes, the new directives also suggest that women forgo clinical breast exams by their doctors altogether so long as they are at average risk. As recently as April, the United States Preventative Services Task Force, a government panel, clarified its guidelines that call for mammograms to begin at age 50, but for individual women to coordinate decisions to screen earlier with their doctors.

When the USPSTF’s 50-and-over recommendation was first made in 2009, it sparked an uproar for not suggesting that women undergo screening in their 40s.

“I am appalled and horrified,” one Sloan-Kettering doctor told Time. “There is no doubt that mammography screening in women in their 40s saves lives. To recommend that women abandon that is absolutely horrifying to me.”

The new ACS guidelines now fall more in line with the assessment that women have been getting screened too early and, sometimes, too often.

“The changes reflect increasing evidence that mammography is imperfect, that it is less useful in younger women, and that it has serious drawbacks, like false-positive results that lead to additional testing, including biopsies,” noted Denise Grady at The New York Times.

As Christie Aschwanden at FiveThirtyEight points out, if there’s one solace here, it’s that other countries offer conflicting assessments on the issue of screening as well:

If you’re a woman living in the U.K., the National Health Service will invite you to come in for mammography screening for breast cancer every three years from age 50 through 69. In Australia, women ages 50 through 74 are advised to undergo screening every two years. Women in Uruguay ages 40 to 59 are obliged to get mandatory mammograms every two years, and in Austria, women are told, “Participation is entirely up to you!”

The Dos and Don’ts of Cultural Appropriation

Sometime during the early 2000s, big, gold, “door-knocker” hoop earrings started to appeal to me, after I’d admired them on girls at school. It didn’t faze me that most of the girls who wore these earrings at my high school in St. Louis were black, unlike me. And while it certainly may have occurred to me that I—a semi-preppy dresser—couldn’t pull them off, it never occurred to me that I shouldn’t.

More From Quartz What Do We Really Mean When We Talk About Cultural Appropriation Blackness Isn’t Something That Can Be Acquired With a Little Bronzer Junya Watanabe’s Africa-Themed Fashion Show Was Missing a Key Element: Black ModelsThis was before the term “cultural appropriation” jumped from academia into the realm of Internet outrage and oversensitivity. Self-appointed guardians of culture have proclaimed that Miley Cyrus shouldn’t twerk, white girls shouldn’t wear cornrows, and Selena Gomez should take off that bindi. Personally, I could happily live without ever seeing Cyrus twerk again, but I still find many of these accusations alarming.

At my house, getting dressed is a daily act of cultural appropriation, and I’m not the least bit sorry about it. I step out of the shower in the morning and pull on a vintage cotton kimono. After moisturizing my face, I smear Lucas Papaw ointment—a tip from an Australian makeup artist—onto my lips before I make coffee with a Bialetti stovetop espresso maker a girlfriend brought back from Italy. Depending on the weather, I may pull on an embroidered floral blouse I bought at a roadside shop in Mexico or a stripey marinière-style shirt—originally inspired by the French, but mine from the surplus store was a standard-issue Russian telnyashka—or my favorite purple pajama pants, a souvenir from a friend’s trip to India. I may wear Spanish straw-soled espadrilles (though I’m not from Spain) or Bahian leather sandals (I’m not Brazilian either) and top it off with a favorite piece of jewelry, perhaps a Navajo turquoise ring (also not my heritage).

As I dress in the morning, I deeply appreciate the craftsmanship and design behind these items, as well as the adventures and people they recall. And while I hope I don’t offend anyone, I find the alternative—the idea that I ought to stay in the cultural lane I was born into—outrageous. No matter how much I love cable-knit sweaters and Gruyere cheese, I don’t want to live in a world where the only cultural inspiration I’m entitled to comes from my roots in Ireland, Switzerland, and Eastern Europe.

There are legitimate reasons to step carefully when dressing ourselves with the clothing, arts, artifacts, or ideas of other cultures. But please, let’s banish the idea that appropriating elements from one another’s cultures is in itself problematic.

Such borrowing is how we got treasures such as New York pizza and Japanese denim—not to mention how the West got democratic discourse, mathematics, and the calendar. Yet as wave upon wave of shrill accusations of cultural appropriation make their way through the Internet outrage cycle, the rhetoric ranges from earnest indignation to patronizing disrespect.

And as we watch artists and celebrities being pilloried and called racist, it’s hard not to fear the reach of the cultural-appropriation police, who jealously track who “owns” what and instantly jump on transgressors.

In the 21st century, cultural appropriation—like globalization—isn’t just inevitable; it’s potentially positive. We have to stop guarding cultures and subcultures in efforts to preserve them. It’s naïve, paternalistic, and counterproductive. Plus, it’s just not how culture or creativity work. The exchange of ideas, styles, and traditions is one of the tenets and joys of a modern, multicultural society.

So how do we move past the finger pointing, and co-exist in a way that’s both creatively open and culturally sensitive? In a word, carefully.

1. Blackface Is Never Okay

This is painfully obvious. Don’t dress up as an ethnic stereotype. Someone else’s culture or race—or an offensive idea of it—should never be a costume or the butt of a joke.

You probably don’t need an example, but U.S. fraternity parties are rife with them. Sports teams such as the Washington Redskins, and their fanbases, continue to fight to keep bigoted names and images as mascots—perpetuating negative stereotypes and pouring salt into old wounds. Time to move on.

2. It’s Important to Pay Homage to Artistry and Ideas, and Acknowledge Their Origins

Cultural appropriation was at the heart of this year’s Costume Institute exhibition, “China: Through the Looking Glass,” at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. There was a great deal of hand-wringing in advance of the gala celebrating the exhibit’s opening—a glitzy event for the fashion industry which many expected to be a minefield for accidental racism (and a goldmine for the cultural-appropriation police).

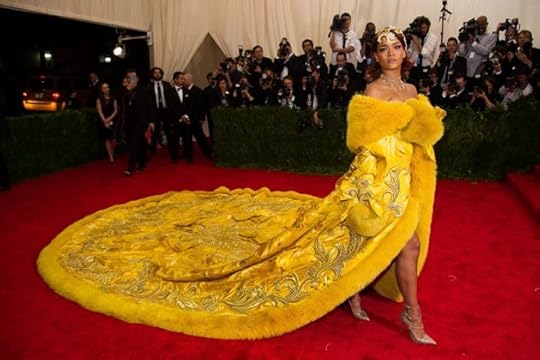

Rihanna’s dress for the Met Gala was made by the Chinese designer Guo Pei in her Beijing atelier. (Charles Sykes / Invision / AP)

Rihanna’s dress for the Met Gala was made by the Chinese designer Guo Pei in her Beijing atelier. (Charles Sykes / Invision / AP) Instead, the red carpet showcased some splendid examples of cultural appropriation done right. Among the evening’s best-dressed person was Rihanna, who navigated the theme with aplomb in a fur-trimmed robe by Guo Pei, a Beijing-based Chinese couturier whose work was also part of the Met’s exhibition. Rihanna’s gown was “imperial yellow,” a shade reserved for the emperors of ancient Chinese dynasties, and perfectly appropriate for pop stars in the 21st century. Rihanna could have worn a Western interpretation, like this stunning Yves Saint Laurent dress Tom Ford designed for the label in 2004, but she won the night by rightfully shining the spotlight on a design from China.

3. Don’t Adopt Sacred Artifacts as Accessories

Karlie Kloss in a headdress at the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show (Jamie McCarthy / Getty Images)

Karlie Kloss in a headdress at the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show (Jamie McCarthy / Getty Images) When Victoria’s Secret sent Karlie Kloss down the runway in a fringed suede bikini, turquoise jewelry, and a feathered head dress—essentially a “sexy Indian” costume—many called out the underwear company for insensitivity to native Americans, and they were right.

Adding insult to injury, a war bonnet like the one Kloss wore has spiritual and ceremonial significance, with only certain members of the tribe having earned the right to wear feathers through honor-worthy achievements and acts of bravery.

“This is analogous to casually wearing a Purple Heart or Medal of Honor that was not earned,” Simon Moya-Smith, a journalist of the Oglala Lakota Nation, told MTV.

For this reason, some music festival organizers have prohibited feather headdresses. As The Guardian points out, it’s anyone’s right to dress like an idiot at a festival, but someone else’s sacred object shouldn’t be a casual accessory. (Urban Outfitters, take note.)

4. Remember That Culture Is Fluid

“It’s not fair to ask any culture to freeze itself in time and live as though they were a museum diorama,” says Susan Scafidi, a lawyer and the author of Who Owns Culture?: Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law. “Cultural appropriation can sometimes be the savior of a cultural product that has faded away.”

A denim processor in Kojima, Japan (Chris McGrath / Getty Images)

A denim processor in Kojima, Japan (Chris McGrath / Getty Images) Today, for example, the most popular blue jeans in the U.S.—arguably the cultural home, if not the origin of the blue jean—are made of stretchy, synthetic-based fabrics that the inventor Levi Strauss (an immigrant from Bavaria) wouldn’t recognize. Meanwhile, Japanese designers have preserved “heritage” American workwear and Ivy League style, by using original creations as a jumping-off point for their own interpretations, as W. David Marx writes in Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style:

America may have provided the raw forms for Japan’s fashion explosion, but these items soon became decoupled from their origin …More importantly, the Japanese built new and profound layers of meaning on top of American style—and in the process, protected and strengthened the original for the benefit of all. As we will see, Japanese fashion is no longer a simple copy of American clothing, but a nuanced, culturally rich tradition of its own.

Not to mention the ne plus ultra for many American denim-heads.

5. Don’t Forget That Appropriation Is No Substitute for Diversity

At Paris Fashion Week earlier this month, the Valentino designers Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli sent out a collection they acknowledged was heavily influenced by Africa.

“The real problem was the hair,” wrote Alyssa Vingan at Fashionista, pointing out that the white models wore cornrows, a style more common for those with African hair, “thereby appropriating African culture.”

In a recent video that went viral, the Nicki Minaj at the MTV Video Music Awards (Mark Ralston / AFP / Getty Images)

‘‘Come on, you can’t want the good without the bad,” said Minaj. “If you want to enjoy our culture and our lifestyle, bond with us, dance with us, have fun with us, twerk with us, rap with us, then you should also want to know what affects us, what is bothering us, what we feel is unfair to us. You shouldn’t not want to know that.’’

Cherry-picking cultural elements, whether dance moves or print designs, without engaging with their creators or the cultures that gave rise to them not only creates the potential for misappropriation; it also misses an opportunity for art to perpetuate real, world-changing progress.

7. Treat a Cultural Exchange Like Any Other Creative Collaboration—Give Credit, and Consider Royalties

Co-branded collaborations are common business deals in today’s fashion industry, and that’s just how Oskar Metsavaht, the founder and creative director of the popular Brazilian sportswear brand Osklen, treated his dealings with the Asháninka tribe for Osklen’s Spring 2016 collection.

Francisco Piyako, an Asháninka representative, told Quartz the tribe will get royalties from Osklen’s spring 2016 collection, as well as a heightened public awareness of their continued struggle to protect land against illegal loggers and environmental degradation.

Osklen's Spring 2016 collection (Oskar Metsavaht / Lynda Churilla / Osklen)

Osklen's Spring 2016 collection (Oskar Metsavaht / Lynda Churilla / Osklen) In return, Metsavaht returned from his visit with the Asháninka with motifs and concepts for Osklen’s spring 2016 collection: Tattoos were reproportioned as a print on silk organza; the striking “Amazon red” of a forest plant accented the collection; and women’s fabric slings for carrying children reappeared in the crisscross shape of a dress. Metsavaht’s photographs of the Amazon forest, the Asháninka, and wild animals also appeared on garments, as well as Osklen’s website.

“Sharing values, sharing visions, sharing the economics, I think it’s the easiest way to work,” said Metsavaht. “This is the magic of style. It’s the magic of art. It’s the magic of the design.”

And it’s a magic that I’d be happy to appropriate for my closet.

‘Stories Are a Living Thing’

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

Doug McLean When John Freeman stepped down as the editor of Granta in 2013—in a much-publicized protest against the budget cuts at the celebrated British journal—the literary world waited to see what he’d do next. Since then, he’s been busy writing book reviews, editing an anthology of essays on New York City life, and publishing his own book of interviews with writers like Toni Morrison and Don DeLillo. But it wasn’t until this month that Freeman finally returned to where he’s likely most comfortable: at the helm of a literary journal. The new endeavor, Freeman’s, is more like a recurring anthology than a traditional magazine—two themed, book-length issues will be published each year by Grove Press. The first issue, “Arrivals,” features titans like Haruki Murakami and Lydia Davis alongside emerging writers.

When I spoke to Freeman for this series, he explained his attraction to the work of Louise Erdrich, the National Book Award-winning novelist who’s featured in the first Freeman’s. Erdrich, he told me, knows how to tell a story as well as anyone alive; he pointed to a favorite chapter from her 1984 novel Love Medicine, and tried to account for her particular brand of narrative magic. We spoke about why some stories snare us more than others, why his new magazine doesn’t even have a website, and why he thinks print books will prevail as our favorite way to read.

Freeman, the former president of the National Book Critics Circle, is also the author of the nonfiction book The Tyranny of Email, and his poems have appeared in venues like The New Yorker. He spoke to me by phone.

John Freeman: I first read Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine in 1992, when I was a college student at Swarthmore. It was one of the first books I read where, based on the picture on the back flap, the author was younger than my mother. At the time, I’d read only the kinds of books they assigned in public high schools in California, where I grew up. I’d read almost nothing by anyone living, obviously—because why would you do that? Books were by dead people.

The first reading bowled me over. Love Medicine is a book about people who are, to some degree, invisible, and the invisible forces that determine their lives: love and betrayal and heritage. What was remarkable to me was the way it took all the narrative complexities of Faulkner and reinterpreted them onto this reservation on the edge of North Dakota. The book managed to convince me that stories—mutually shared, argued over, and fought for, as they are in Faulkner—are a living thing. (A thing with unique power for Native Americans, whose history was entirely co-opted, and possessed largely by the tellers of those tales.)

Erdrich herself is a master storyteller, too—she is, you think, someone who’s been around storytellers her whole life. (Now that writing can be taught, I think we underestimate the power of being around good storytellers. Erdrich has clearly learned from the best.) Her language isn’t particularly fancy. It’s practical. She just tells you and shows you things—and, along the way, this magical effect happens.

My favorite chapter, which was also published in standalone form as a short story called “Scales,” is told in the first person by a woman, Albertine Johnson. She becomes friends with a pregnant woman, Dot, whose Native American boyfriend, Gerry, is always breaking out of prison. Over the course of the chapter, as Dot gets closer to giving birth, their friendship gets closer and closer—and Gerry keeps running farther from the law.

This story works, on the one hand, because of its plot—the buildup of tension around Dot’s pregnancy, and Gerry’s journeys in and out of jail. Erdrich is thinking about meaning and love and justice through the action, and through what the characters do. If it were just this, though, it might be slightly melodramatic. What makes it work is the way Erdrich also manages to include images that somehow distill this situation, its characters, and the truth of their emotional lives.

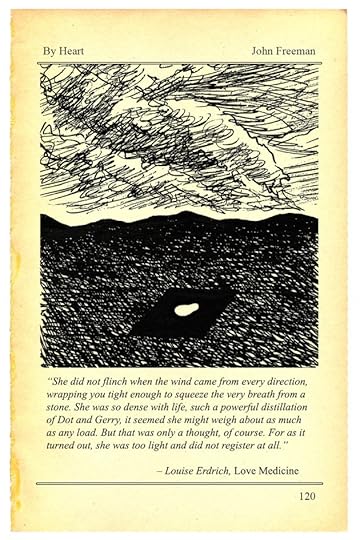

My favorite example of this comes at the very end of the story. The two women have been working at a weigh station, where they weigh trucks full of gravel on state roads. When Gerry gets captured—killing someone in the process—all they have left of value is a child, Gerry’s child. And so they put this little baby on the truck scales:

Dot and I continued to work the last weeks together. Once we weighed baby Shawn. We unlatched her little knit suit, heavy as armor, and bundled her in a light, crocheted blanket. Dot went into the shack to adjust the weights. I stood there with Shawn. She was such a solid child, she seemed heavy as lead in my arms. I placed her on the ramp between the wheel sights and held her steady for a moment, then took my hands slowly away. She stared calmly into the rough distant sky. She did not flinch when the wind came from every direction, wrapping you tight enough to squeeze the very breath from a stone. She was so dense with life, such a powerful distillation of Dot and Gerry, it seemed she might weigh about as much as any load. But that was only a thought, of course. For as it turned out, she was too light and did not register at all.

This passage literally took my breath away when I first read it. Taken out of context, it’s magical and strange a little bit weird—what they’re doing is odd and impractical, a little bit like trying to weigh the soul. But there’s a real sadness that the things Erdrich’s characters cherish cannot be weighed at all, because they’re not valued in the world they inhabit. Dot and Albertine are trying to find some confirmation that the world registers the things that are important to them. This huge scale made for trucks is designed to measure raw materials, things that are ripped from the earth. But a child, with a heart, and a brain, and lungs? That, it can’t do.

When Erdrich couples her dramatic plot with an image as powerful as this one—a baby in a too-tight winter suit, being weighed in the middle of a wind that’s almost strong enough to knock it over—that’s where the magic happens. When action and image combine in this way, plot becomes a story.

One of the hard things about editing is that it’s very hard to find moments like this one that make everything work. Say this same story came in as a submission, but it was just the plot. You can’t as an editor, say, “Why don’t you have them weigh a baby?” You can only say, there’s something missing. It’s up to the writer to have the imagination to figure out what that will be.

One of the amazing things about Erdrich is that she never tries to instruct you about the past or history. Yes, her books are about justice and historical memory and the terrible cost of violence—and mostly about family and love—but she’s never didactic about the content. Instead, she just tells stories. She doesn’t press her own ideas and interpretations down into her books. Language contains meaning that is greater than our intended meaning—and Erdrich, of all the living American writers, uses that capacity to the greatest ability. Her work feels huge as a result—an entire universe contained inside a North Dakota town.

Erdrich’s work feels huge—an entire universe contained inside a North Dakota town.I think in order for stories to take off, they have to leave the artist behind in this way. This is true even with someone like David Mitchell, who’s like a Philip Johnson or Rem Koolhaas of narrative architecture. All the world writers that we hold onto and treasure, they’re magicians of narrative—the magic trick is their ability to make something bigger than themselves. The Halldór Laxnesses and the Elena Ferrantes and the Günter Grasses and the Murakamis—there’s always something oracle-like about them. It’s not that they explain the world. It’s that what flows through their stories seems far bigger than what can be contained in one life, one body, one organism. That’s the quality that brings me back to Louise Erdrich.

That deep, immersive experience of reading around a theme … is an experience, I think, that’s best had between the covers of a book. Scrolling and toggling and moving from screen to screen is trance-like, sure. But it's a different experience, physically, to spend two hours on the Internet versus two hours in a book. Your body feels different. Your eyes feel different. Online, the form and the content are working, to some degree, against each other.

But, happily, you see the recent data: E-book sales are down, bookstore openings are up, people are returning to the physical book. And when people do read online, they are reading longer pieces. People do seem to miss that immersive experience. I think it’s something essential to the interior lives of people who think.

If you look logically at books, everyone should be reading on e-books. They’re better paper-wise. They’re better and more efficient for your back. (I’m travelling right now and I seem to have about 20 books with me.) But maybe storytelling is a greater faculty than reason. The narrative experience, the storytelling experience that you get from a book seems to be more immersive for many people. So, in some ways, it’s a good time to be starting an anthology or a journal in print.

As an editor there’s a certain perfection that you look for, that perfect wrapping of form around meaning. So much of Louise Erdrich’s intelligence is braided into the graceful and instinctual ways she tells a story. When you try to articulate why her pieces work, it’s very hard to pry apart the craft from the meaning of the stories. To me, that’s always a very, very good sign.

The Civilian Toll of Russia’s Bombing Campaign

Exactly three weeks after Russia decided to launch airstrikes in Syria, the country’s campaign has already been criticized for hitting non-ISIS targets, its violations of Turkish airspace, and allowing its planes to fly too close to American ones, as well as a misfiring of cruise missiles from the Caspian Sea that mistakenly landed in Iran.

On Tuesday, some light was shed on the civilian toll of Russia’s bombing campaign. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, 370 people have been killed by Russian warplanes since September 30. Of that number, 34 percent have been civilians—127 people, including 36 children and 34 women.

When held against one assessment of the airstrikes by the American-led coalition, which started in September 2014, the Russian numbers come more clearly into view. Back in June, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights noted that of 3,000 people who had been killed by coalition airstrikes in Syria, 162 were civilians. (At the time, the British-based monitoring organization “re-expressed its strong condemnation” of the United States and its international partners.)

The figures in Tuesday’s report did not include an overnight Russian airstrikes in Syria’s Latakia province that killed a high-ranking commander of a Syrian rebel group that had received American-made weapons. According to some reports, at least 15 civilians were killed in the sustained bombardment.

Also, on Tuesday, CNN reported American military pilots have been warned against reacting to Russian planes over Syrian skies. After some recent close calls, the two countries are working to iron out a technical agreement so that pilots will maintain contact with each other in the air.

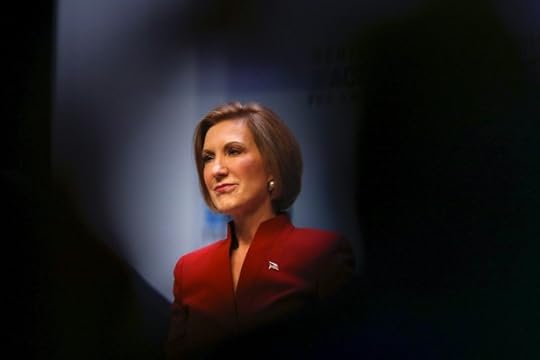

What Happened to Carly Fiorina?

Remember Carly Fiorina? It now seems forever ago, but in late September she was being heralded as the next big thing in the Republican primary field—the outsider candidate who could marshall establishment support, and finally slay the Trump dragon.

Now look at the polls. An NBC/Wall Street Journal poll Monday has her at 7 percent, running behind the much-maligned Jeb Bush. That’s down from 11 in late September. A CNN poll released Tuesday is even bleaker. She comes in fourth—tied with also-ran Chris Christie and behind Rand Paul, who’s on campaign deathwatch. That’s even worse than it seems, because in mid-September she was at 15 percent in the same poll, good for second place.

Related Story

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Race: A Cheat Sheet

So what happened to Fiorina? There’s no single obvious explanation, but here are a few ideas.

Fiorina’s polling has correlated strongly with her debate performance. She surged after dominating the undercard at the first Republican debate in August, and after winning a promotion to the main stage for the second debate, she was the consensus winner there, too. After each debate, her numbers surged. But there hasn’t been a GOP debate for more than a month, since September 16.

In that time, her stock has plummeted. Fiorina has practically disappeared from the headlines in the last few weeks. She doesn’t seem to be as good at collecting “earned media”—attention in the press, more or less. Donald Trump and Ben Carson, in contrast, are great at creating controversies that get them on TV. John Sides at The Monkey Cage has been on a crusade to convince readers that Trump’s high polling, and any dips, are caused almost entirely by the level of media attention he receives. Carson’s statements about the Holocaust and gun control, or about the Umpqua massacre, may be derided by some, but they keep his name in the news—and they rile up supporters who see criticism of his remarks as persecution. (Fiorina pulled something similar off when she insisted she’d seen a video taken at a Planned Parenthood that did not exist, but that moment passed, and she hasn’t created another.)

Read Follow-Up Notes Readers criticize FiorinaPeople have been predicting the demise of Trump’s campaign since, well, before it existed, but the drumbeat actually grew after the second debate, in which he was generally said to have put in a subpar performance. But as Molly Ball points out today, that hasn’t happened—he’s really running.

The non-demise of Trump, and the continued strength of Ben Carson, seem to go a long way to explaining Fiorina’s struggles. Her big climb coincided with Trump’s first stumble. But now his polling has stabilized. There a large group of GOP voters who want an “outsider” candidate, but however large that group may be, it’s also finite, and it’s being split between Trump, Carson, and Fiorina. In fact, Fiorina’s campaign has taken the path that many pundits expected for Trump, while Trump and Carson both gained ground in the NBC/WSJ poll. As long as they’re strong, it will take voters away from her. Here’s the three-way matchup:

One lesson from this is that Fiorina will flounder until (a) Trump and/or Carson collapses; (b) she figures out the earned-media game; or (c) the next debate, which is October 28.

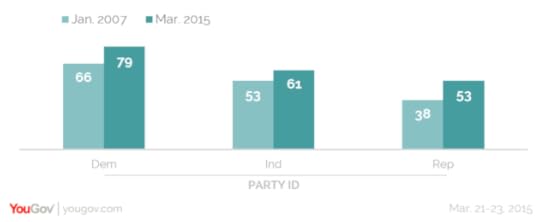

But Fiorina has always had a structural disadvantage in the campaign, because she is a woman. While Americans have become dramatically more willing to elect a female president over the last quarter-century, there remains some reluctance. It’s particularly strong on the Republican side of the aisle, as YouGov found in March:

Is the U.S. Ready for a Woman President? ‘Yes’ in 2007 vs. 2015

In a separate question, nine in 10 Democrats told pollsters that they’re rooting for a female president to be elected in their lifetimes—which lifts Hillary Clinton. In contrast, only a third of Republicans feel that way.

It’s also possible, though, that Fiorina’s support was never really there, that she was a paper tiger erected by the press. She doesn’t seem to have a natural constituency, doesn’t have much establishment support, and doesn’t have the same mix of charisma and outlandish comments that has boosted Trump. Perhaps her strong showings in late September were all just a media creation—poll numbers being pumped up by media coverage of the first debate, with her sudden polling jump begetting still more media coverage through the second debate. It will be easier to tell once post-debate polls start arriving, but even if Fiorina turns in a strong performance—and past experience suggests she will—that may not be enough to sustain real momentum.

Update, 11:43 a.m.: John Sides points me to this graph, which shows how closely the collapse in press attention to Fiorina’s campaign tracks her polling collapse:

Carly Fiorina Television Mentions, Last 30 Days

2016 Campaign Television Tracker

2016 Campaign Television Tracker

The Computer Glitch That's Keeping Poor People From Their Money

Updated on October 20, 2015 at 12:00 p.m.

Updated on October 20, 2015 at 12:00 p.m.

The final few days before a paycheck can be nerve wracking. That’s especially true for poorer Americans who generally have little wealth, no emergency cash, and limited access to credit to help them bridge the gap during a difficult time. And for those who rely on the alternative financing of RushCards—prepaid debit cards aimed specifically at underbanked Americans—things have gotten much more stressful after their cards stopped working a week ago.

More From Ghost Towns of the 21st Century When Technology Is Too Advanced Hangovers: They're Costing the U.S. Economy

Ghost Towns of the 21st Century When Technology Is Too Advanced Hangovers: They're Costing the U.S. Economy RushCards aren’t tied to a bank account, and getting one doesn’t involve a credit check. People can buy them online and then load the card with a specific amount of money. They can also have their employer direct-deposit checks directly to the card. The cards can be used at stores, online, or anyplace one might use a normal debit card, which makes it more convenient than cash or checks. But, there are shortfalls. Though they are insured, such cards don’t necessarily fall under the same regulations as bank cards. And without the backing of a traditional bank account, a technical glitch—like that experienced by RushCard—is much more dangerous, because it leaves users without any way to access their money. They can’t, for instance, head to a local branch with their account number and withdraw money or pay bills.

The complaints from users started rolling in early last week—cards weren’t working, balances were erroneously listed as zero. Many who called customer service weren’t able to get through, some who did connect were told their accounts couldn’t be found. Others said that paychecks, which they have direct deposited onto their cards, hadn’t shown up on time. For just about anyone, this scenario sounds like a nightmare. But for those who are already pinching pennies, missed or late paychecks and denied account access can be disastrous—leading them to take out loans of last resort, like those made by payday lenders, or, failing that, leaving them without money to pay rent, buy groceries, or put gas in their cars, which in turn can make it hard to get to work, which in turn can lead to being fired.

@RushCard it's been a whole week without money, it's hard out here. Single mother no help. I work hard for my money and now I can't get it

October 19, 2015

Netflix Brings Back Gilmore Girls

Gilmore Girls is one of the great triumphs in modern TV—a sharp, endlessly rewatchable dramedy that holds up better than most new television, with a Netflix fanbase as wide as its original audience on the (now-defunct) WB network. It also had one of the worst goodbyes in TV history, airing a tragically bad seventh season without the involvement of its creator Amy Sherman-Palladino. So Netflix is riding to the rescue, ordering a limited-series revival of the show, penned by Sherman-Palladino and starring Lauren Graham, Alexis Bledel, and all the old old favorites.

Related Story

The Guys Who Love Gilmore Girls

Netflix long ago began branding itself as some super-powered take on Nick at Nite, airing classic shows and bringing them back to life with new seasons. In Arrested Development’s case, it felt like an obvious move. A planned revival of Full House felt more cynical. The return of Wet Hot American Summer was bizarre and unexpected. But Gilmore Girls feels the most karmically appropriate of them all: a chance for Amy Sherman-Palladino, who exited the show after its sixth and penultimate season because of a contract dispute, to right the wrongs done in her absence.

Not that Netflix cares one bit for karma. No doubt its internal algorithms have made the case for new Gilmore Girls episodes very clear. But the chance for redemption is a fun bonus storyline, and Gilmore Girls fans are an intense bunch. Michael Ausiello, who broke the news of Gilmore’s return on TVLine, has long stoked the fires for a revival, hanging on Sherman-Palladino’s comment that she had written a series finale that ended with four words that never aired after she left the show. When Gilmore Girls closed up shop in 2007, the concept of a revival, or even a goodbye movie, seemed ludicrous. With the rise of Netflix’s nostalgia machine, it became inevitable.

Apparently all the “major players” will be back—Graham and Bledel as the mother-daughter team Lorelai and Rory Gilmore, Kelly Bishop as Lorelai’s mother, Emily, and Scott Patterson as Lorelai’s chief love interest Luke. The tragic loss of Edward Herrmann, who played Lorelai’s father, Richard, will have to be addressed, and who knows if the now-Oscar-nominated Melissa McCarthy (who played the ever-cheerful chef Sookie) will be able to clear her schedule for the four 90-minute episodes being planned. But these are just extra details. What really matters: Gilmore Girls is coming back, and that’s plenty to be excited about.

Law & Order: PSA

The line between reality and fiction has always been somewhat porous when it comes to Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, between its ripped-from-the-headlines plots and its star Mariska Hargitay’s advocacy efforts on behalf of victims of sexual assault. The show has been accused of exploiting real-life tragedies for ratings, of making “rape a spectator sport,” and of descending into paranoid alarmism from time to time. But as a recent study conducted by Washington State University reveals, the Law & Order franchise might also be educating viewers about rape.

The study, published in the Journal of Health Communication, took 313 college freshmen and surveyed them on whether they watched the three main procedural franchises on network television: Law & Order, CSI, and NCIS. Students were asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with statements that explored rape-myth acceptance (“If a woman is raped she is at least somewhat responsible for letting things get out of control”), intentions to seek consent for sexual activity (“I would stop and ask if everything is okay if my partner doesn’t respond to my sexual advances”), and intentions to refuse unwanted sexual activity (“I would refuse unwanted sexual activity from my date even if it may destroy the romantic atmosphere”).

The surveys found that exposure to Law & Order was associated with “lower rape-myth acceptance,” greater intentions to seek consent for sexual activity, greater intentions to refuse unwanted sexual activity, and greater intentions to adhere to decisions related to sexual consent. By contrast, exposure to CSI was associated with lowered intentions to seek consent and a greater acceptance of rape myths. There were fewer significant findings related to NCIS, although exposure to the show was associated with lower intentions to refuse sexual activity. “Our results indicate that specific crime drama franchises are associated with decreased rape-myth acceptance,” the study states.

The authors acknowledge that causality is hard to infer: People who are more informed about rape myths and issues of consent might choose to watch Law & Order over other shows because it affirms their pre-existing beliefs. Nevertheless, they conclude that watching Law & Order might indeed have a positive effect on viewers:

Given the Law & Order producers’ conscientious efforts to not glamorize rape and to portray punishment of the crime, they have essentially created a program that could be used to reduce sexual assault. In contrast, the CSI franchise frequently depicts sexual assault in ways that objectify the victim and reinforce common rape myths. This study’s findings indicate that depicting sexual assault in this manner may promote behaviors that are not conducive to healthy sexual relationships. This has significant implications, given that the CSI franchise has enjoyed much greater popularity than the Law & Order franchise.

The research is by no means the first academic attempt to draw conclusions about how television influences popular understanding of sexual assault. A 2006 study conducted at the University of California, Santa Barbara found that watching a television movie featuring a character who was raped by an acquaintance “increased awareness of date rape as a social problem across all demographic groups” who were surveyed. And in 2007, research found that the acceptance of rape myths among female college students was associated with watching television generally.

In her 1999 book Rape on Prime-Time: Television, Masculinity, and Sexual Violence, the women’s studies professor Lisa M. Cuklanz writes that prime-time episodic portrayals of rape on television between 1976 and 1990 offer insight into how advocacy affects television and how television affects public opinion. “By 1990,” Cuklanz writes, “prime-time episodes were offering complex depictions of date/acquaintance rape and other issues more often than the highly formulaic depictions of violent stranger rape commonly found in the earlier years. Thus, this 15-year period encompasses a remarkable adaptation in television’s treatment of rape.”

Law & Order: SVU, the only show in the franchise still in production, certainly isn’t perfect, and the ways in which it shows police officers doggedly investigating sex crimes and handling victims with the utmost care and attention certainly defies the real-life experiences of many survivors. But that it offers such explicit and incontrovertible definitions of what constitutes sexual assault, the study suggests, might nevertheless make it a valuable and productive show for cultural consumers.

A Blistering Response From Amazon

Updated on October 19 at 3:15 p.m. ET

Amazon says a New York Times story from August about what it’s like to work at the online retailer “misrepresented” the company. In a scathing response, Amazon says it presented its findings to the newspaper several weeks ago, “hoping they might take action to correct the record. They haven’t, which is why we decided to write about it ourselves.” Dean Baquet, the Times’s executive editor, in a response reiterated his “support for our story about Amazon’s culture.”

The piece, published in Medium, is written by Jay Carney, the former White House spokesman who now serves as Amazon’s senior vice president for global corporate affairs. Baquet’s response, in the form of a letter to Carney, was also posted on Medium.

Among the claims made in Amazon’s response: Bo Olson, the former Amazon employee quoted in the Times story as saying, “Nearly every person I worked with, I saw cry at their desk,” left the company “after an investigation revealed he had attempted to defraud vendors and conceal it by falsifying business records”; another worker, Elizabeth Willet, who was quoted as saying she was “strafed” through the company’s feedback tool, received three pieces of feedback through that tool, including positive feedback; Dina Vaccari, an Amazon employee quoted in the story saying she didn’t sleep for four days because of how hard the company wanted its employees to work, now says: “No one forced me to do this—I chose it and it sucked at the time but in no way was I asked or forced by management to do this.”

The response specifically finds fault with the Times’ Jodi Kantor, who spent six months reporting the story with David Streitfeld, another of the newspaper’s reporters.

“We were in regular communication with Ms. Kantor from February through the publication date in mid-August,” Carney writes. “And yet somehow she never found the time, or inclination, to ask us about the credibility of a named source whose vivid quote would serve as a lynchpin for the entire piece.”

Amazon’s response adds:

In any story, there are matters of opinion and there are issues of fact. And context is critical. Journalism 101 instructs that facts should be checked and sources should be vetted. When there are two sides of a story, a reader deserves to know them both. Why did the Times choose not to follow standard practice here? We don’t know. But it’s worth noting that they’ve now twice in less than a year been called out by their own public editor for bias and hype in their coverage of Amazon. (Last fall, the public editor wrote a critique of the paper’s coverage of Amazon’s negotiations with Hachette titled “Publishing Battle Should Be Covered, Not Joined.” And in the wake of the story on Amazon’s culture, she wrote, “The article was driven less by irrefutable proof than by generalization and anecdote. For such a damning result, presented with so much drama, that doesn’t seem like quite enough.”)

What we do know is, had the reporters checked their facts, the story they published would have been a lot less sensational, a lot more balanced, and, let’s be honest, a lot more boring. It might not have merited the front page, but it would have been closer to the truth.

The pushback from the company more than two months after the Times published its story illustrates the level to which Amazon is trying to correct the narrative that depicted Amazon as a brutal place to work. Here’s an excerpt from the Times story, that’s fairly typical:

At Amazon, workers are encouraged to tear apart one another’s ideas in meetings, toil long and late (emails arrive past midnight, followed by text messages asking why they were not answered), and held to standards that the company boasts are “unreasonably high.” The internal phone directory instructs colleagues on how to send secret feedback to one another’s bosses. Employees say it is frequently used to sabotage others. (The tool offers sample texts, including this: “I felt concerned about his inflexibility and openly complaining about minor tasks.”)

Baquet, in his response, said in the course of the reporting, the Times found patterns: “many people raised similar concerns.” Here’s more:

Virtually every person quoted in the story stated a view that multiple other workers had also told us. (Some other workers were not quoted because of nondisclosure agreements, fear of retribution or because their current employers were doing business with Amazon.)

And he noted: “The story did not assert that every Amazon employee had a difficult time there.” Baquet issued a point-by-point rebuttal of every example Carney raised in his post earlier Monday. Discussing the specific example of Olson, Baquet wrote:

Olson described conflict and turmoil in his group and a revolving series of bosses, and acknowledged that he didn’t last there. He disputes Amazon’s account of his departure, though. He told us today that his division was overwhelmed and had difficulty meeting its marketing commitments to publishers; he said he and others in the division could not keep up. But he said he was never confronted with allegations of personally fraudulent conduct or falsifying records, nor did he admit to that.

If there were criminal charges against him, or some formal accusation of wrongdoing, we would certainly consider that. If we had known his status was contested, we would have said so.

Carney replied to Baquet’s letter, saying: “The bottom line is the New York Times chose not to fact-check or vet its most important on-the-record sources, despite working on the story for six months. I really don’t see a defensible explanation for that failure.”

But Amazon, in its posts Monday, did not challenge the other claim made in the Times story: that Amazon can be a challenging place for its female employees. One female employee, Molly Jay, who had received high ratings for years, found herself being called “a problem” after she began traveling to care for her father, who was stricken with cancer. Another, Michelle Williamson, a 41-year-old mother of three children, was told, in the words of the newspaper, “that raising children would most likely prevent her from success at a higher level because of the long hours required.” A third, Julia Cheiffetz, wrote in Medium, about being sidelined after having a child and being diagnosed with cancer.

When the story was first published, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos responded almost immediately, writing a memo to his company’s 180,000 workers that “The article doesn’t describe the Amazon I know or the caring Amazonians I work with every day.”

Baquet, writing directly to Carney, added: “I should point out that you said to me that you always assumed this was going to be a tough story, so it is hard to accept that Amazon was expecting otherwise.”

Carney’s reply to Baquet: “Reporters like to joke about stories and anecdotes that are ‘too good to check.’ But the joke is really a warning. When an anecdote or quote is too good to check, it’s usually too good to be true.”

Steve Jobs and the Triumph of the Work Wife

“Why haven’t we slept together?” Steve Jobs (Michael Fassbender) asks his marketing director and confidante, Joanna Hoffman (Kate Winslet), before one of the dramatic product launches that frame the movie named for him. Joanna, without missing a beat, gives her reply: “Because I’m not in love with you.” Steve nods. They leave the matter at that.

In one sense, the exchange is classic Aaron Sorkin: snappy, revealing, fraught both despite and because of its nonchalance. It’s also a notably asexual discussion about sex: The CEO’s question to the woman the movie frames as his Marketing Director Friday isn’t a come-on, really; it’s simply an intellectual wondering. If relationships are operating systems, Steve wants to understand this one a little bit better. And Joanna, for her part, helps him to do that. The two haven’t slept together not just because she has decided against it, she suggests, but because sex was never a possibility in the first place. Because, though the two love each other, they’re not in love.

Related Story

In Steve Jobs, a Fascinating Subject Remains Elusive

Which is another way of saying that Joanna, in Steve Jobs, is the work wife. In her, Sorkin has created a character who is, in many ways, Jobs’s equal—or, well, as equal as anyone could possibly hope to be to Aaron Sorkin’s Steve Jobs. There is respect between them. There is partnership between them. But there is no sex.

Joanna is not, to be clear, a great cinematic figure. She is—like literally every other character in Steve Jobs, arguably including Jobs himself—an extremely eloquent stick figure. (The real Joanna Hoffman, who joined Apple as the fifth hire for Jobs’s beloved Macintosh team in 1980, was a relatively minor character in Steve Jobs, the Walter Isaacson book the movie was based on. Sorkin’s decision to amplify her role in Jobs’s life was based, it seems, on a desire for narrative impact more than a fealty to history.) We are never given an explanation for why she has Jobs’s ear in a way that other people—including Apple’s co-founder, Steve Wozniak—don’t. We’re never told (or shown) her motivation for serving, at the low points as well as the high of his career, as Jobs’s “right-hand woman.”

Instead, Joanna exists, in Steve Jobs’s aggressively hermetic universe, mostly as a classic foil to the film’s eponymous inventor: She’s the yin to his yang, the human to his automaton. (“Do you want to try being reasonable,” she asks him, in an accent only mildly inflected with her native Polish, “just to see what it feels like?”) Joanna is there, in theater after theater, to remind Steve that he, too, is in possession of that classic Sorkenian preoccupation: “better angels.” She is there to reprimand and cajole him into some semblance of human decency. She is his Manic Pixie Moral Compass.

And yet. The flip side of being a foil is the fact that there’s a flip side at all. There’s an inherent equality to the tension between Steve and Joanna in all this, an inherent balance that blends Newtonian physics and that even older of things: human camaraderie. A big part of the equilibrium they maintain throughout the movie, through all the clashes and the inevitable compromises, stems from the very thing Joanna points out to Steve: Their relationship is, both implicitly and deliberately, platonic. Their defining tautology—they have not slept together because they would never sleep together—keeps them, as an operating system, stable.

Joanna is there to cajole Steve into some semblance of goodness. She is his Manic Pixie Moral Compass.It’s been a favorite pastime of critics—and an extremely legitimate one—to point out the sexist streaks of Sorkin’s work, a body partially populated with women who exist to be admired, to be accessorized, to be agents of absolution for men. It’s not that the members of Sorkin’s sisterhood aren’t, individually, compelling characters; the general problem is, instead, that their physics are off—these women orbit around men whose gravitational pull is greater than theirs could ever hope to be. Sydney in The American President, whose happy ending involves keeping her high-powered boyfriend at the expense of her high-powered job. Donna in The West Wing, an assistant who is great at her job, the show suggests, in part because of her fawnish crush on her assistee. Harriet in Studio 60. Dana in Sports Night. MacKenzie in The Newsroom. Pretty much every single woman in The Social Network.

There are explanations for that (the environmental fact, for example, that most of Sorkin’s works are set in male-dominated locations and institutions, whether they be the military or the West Wing or a Hollywood writer’s room). And there are notable exceptions to it, as well. Jo in A Few Good Men. Marylin in The Social Network. C.J. in The West Wing.

And Joanna is, in her way, another exception. She is, in Steve Jobs, neither absent nor accessorized. She is not melodramatic. She is not self-sacrificial. As the Right-Hand Woman to Jobs’s Great Man, she embodies the very thing that can be one of the most compelling aspects of Sorkin’s writing: his understanding of the delicate dynamics that make for effective creative partnerships. He seems fascinated, in particular, by vertical relationships—the president and the chief of staff, the news director and the anchor, the editor and the writer—made horizontal through the flattening forces of mutual respect. Andy Shepherd and A.J. MacInerney. Dan Rydell and Casey McCall. Will McAvoy and MacKenzie McHale. Josiah Bartlet and Leo McGarry. The West Wing introduced many Americans to the notion that the chief of staff can, when truly respected by the president, be the second-most powerful person in American politics. The Newsroom was an object lesson in the sausage-making that makes TV news what it is (and is not).

Joanna Hoffman is, for Steve Jobs, that powerful employee-equal. She is as much of a “trusted confidante” as his narcissism will allow. Which is significant—not just for Sorkin’s work, but for, in some sense, the moment Sorkin is writing for. It speaks to a time when women are gaining a semblance of equality in the workplace. (Sheryl Sandberg has explained the dearth of female executives in part by the fact that male executives resist mentoring younger women, preferring to focus on men not because they’re more promising, but because they present less of a risk of misunderstood intentions.) It speaks to a time when horizontal relationships are becoming increasingly normalized within offices. (The “collaborative workspace”!) It speaks to a time defined culturally by online dating, and by later-in-life marriages, and by the fact that many young people are choosing—or, more often, settling for—gigs over careers. A time when “the office” isn’t what it used to be. And a time when office relationships that extend beyond the platonic are the taboo more than they’re the norm.

Will they or won’t they? we asked. That “they” were co-workers was not, at the time, considered problematic.Compare the Steve/Joanna relationship to the relationship between, say, Mad Men’s Don Draper and pretty much any of his secretaries. (Even with Peggy—the closest thing Don, or the show, had to a work wife—the show’s writers hinted at the possibility of sex between them.) That sexual tension was served, like so many straight-up martinis, around the office may have been an element of the aggressive historical irony the show specialized in, but the sex-at-work ethos neither started nor ended with Mad Men’s televised Madison Avenue. A healthy portion of the sitcoms and series that have been on TV in the last decades have indulged in office-set sexual tension, and indeed treated that tension as a premise of many of their melodramas. Moonlighting. Cheers. Grey’s Anatomy. And on and on. Will they or won’t they? we asked, breathlessly. That the “they” in question were co-workers was not, at the time, considered problematic.

The current crop of shows and movies—not exclusively, certainly, but noticeably—are rejecting that premise. They’re treating work, and the office it’s conducted in, instead as a kind of sacred space that offers refuge from the assorted dramas of family life. In place of Draperian dalliances, we’re getting the cross-generational camaraderie of Jules and Ben in The Intern. The frenemied machinations of Gretchen and Sam in You’re the Worst. Even the cutthroat craftsmanship of reality shows like Top Chef and Project Runway.

And also: the work-marriage of Steve Jobs. And we’re getting, through it, the logical extreme of the moment’s preoccupation with work-life balance: work that comes at the expense of family. Work that is, like a Mac or an iPod, pure in its design aesthetic. In his review, my colleague Chris Orr mentioned an especially strange omission in the film: For some of the later scenes, the scenes that followed Jobs’s unveiling of the iMac, the real-life Jobs was married. Not (just) work-married, but actually married. Steve Jobs no mention of that. Jobs’s marriage was, for Sorkin—another artist who appreciates the aesthetic power of simplicity—perhaps too inconvenient a detail. Families, Sorkin argues again and again, complicate things. Sex complicates things. Compromise complicates things. If you want to put a dent in the universe, Steve Jobs suggests, the best you can hope for is a partner who will understand all that—and who will offer loyalty, honesty, and,when it’s required, a good hammer.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower