Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 314

October 26, 2015

Can't Touch This?

Eating bacon and hot dogs raises a person’s risk of getting colon cancer, the World Health Organization said Monday, and eating non-processed, red meat might do so as well. The agency classified the consumption of red meat as “probably carcinogenic to humans,” and processed meats as “carcinogenic to humans,” based on evidence linking the foods to colorectal and other cancers.

The new status puts processed meat, such as ham and sausages, in the highest-risk “group 1” category, along with substances like tobacco and asbestos. In a statement, the agency said its experts “concluded that each 50 gram portion of processed meat eaten daily increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18 percent.” Red meat is in the level below, called “2a” by the organization, and it encompasses beef, veal, pork, lamb, mutton, horse, and goat.

“Consumed meat should be lean and unprocessed, but not necessarily avoided.”“These findings further support current public-health recommendations to limit intake of meat,” said Christopher Wild, director of the WHO's International Agency for Research on Cancer. “At the same time, red meat has nutritional value.”

The 2a designation is “the equivalent of a take-care label,” as the University of Michigan’s Risk Science Center explains. It only means people should eat less of the foods, not give them up entirely. French-fry oil and shift work, for example, are also both considered “probable” carcinogens by the organization.

In April of last year, IARC called attention to studies linking red and processed meats to colorectal, esophageal, lung, and pancreatic cancers and said exploring the connection further was “a high priority.” The WHO has also said part of meat’s cancer risk might be explained by cooking temperatures. The high-heat, charring method that gives steak and sausages a blackened look might also create cancer-causing compounds.

The designation is predicted to spark hand-wringing within the meat lobby. Shalene McNeill, the executive director of human nutrition research at the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, told Reuters that the group believes the science linking cancer and red meat is far from settled. “Cancer is a complex disease that even the best and brightest minds don't fully understand,” McNeill said. “Billions of dollars have been spent on studies all over the world and no single food has ever been proven to cause or cure cancer.”

It’s true that it’s difficult to prove causality for cancer. A major 2012 study found a small, positive association between meat consumption and cancer. But as the British science writer and pharmacologist David Colquhoun points out, it didn’t totally control for smoking or alcohol consumption.

It’s also worth noting that the new designation doesn’t mean bacon is as deadly as smoking. Cancers from cigarettes and alcohol—other substances in group 1—kill far more people globally than does cancer from processed meat. The higher ranking only means that the evidence linking processed meat to cancer is stronger than that for red meat.

But it does mean processed meat is one food people could cut back on if they want to be healthier.

“Processed meats have been suspect for a while and red meat has been linked to cardiovascular disease, so there is good reason to limit these foods,” said Marleen Meyers, an assistant professor in the division of hematology and medical oncology at the Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York. “For many health reasons, consumed meat should be lean and unprocessed but not necessarily avoided.”

For starters, you can opt for turkey this Thanksgiving rather than ham: There’s no sign that white meat causes cancer—at least not yet.

Related VideoNew plant-based meats are an exciting development for nutrition and the environment.

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump Lash Out

Can there be many things more fun than being an ascendant candidate? It must have been a great few months for Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. Their poll numbers kept rising. The establishment candidates they were running against—Hillary Clinton for Sanders, Jeb Bush and everyone else for Trump—were proving to be less than the juggernauts promised. Across the country, thousands of enthusiastic fans were showing up for rallies. The press, which had sneered at their chances, was suddenly chastened.

But what happens when the magic appears to wear off? Neither Trump nor Sanders is in free fall, but there are signs of diminishing momentum for both. Over the weekend, both candidates took aggressive stands they’d mostly tried to avoid.

At the Iowa Jefferson-Jackson Dinner, a major Democratic event, Sanders took repeated swipes at Clinton, though without naming her.

Related Story

How Will Trump Respond to Ben Carson's Iowa Surge?

“That agreement is not now, nor has it ever been, the ‘gold standard’ of trade agreements,” he said of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, using her own language. “I did not support it yesterday. I do not support it today, and I will not support it tomorrow!”

“Today, some are trying to rewrite history by saying they voted for one anti-gay law to stop something worse. That’s not the case,” he said. “If you agree with me about the urgent need to address climate change, then you would know immediately what to do about the Keystone pipeline. It was not a complicated issue.”

And so on. Sanders has pledged not to run personal attack ads, and in these cases he’s assailing Clinton on the issues. Still, these are some of his most direct attacks on her, and they seem to represent a change to a more aggressive strategy. It’s also potentially risky, since Sanders has won praise for running a “clean campaign.” But he’s in a tough spot: After months in which he steadily gained on her, Clinton has the momentum again, with her lead growing nationally as Sanders’ support stays mostly flat. She was also generally thought to be the winner of the first Democratic debate this month.

Sanders isn’t the only candidate to go negative this weekend. As I noted on Friday, Ben Carson is gaining on Donald Trump nationally and leads him in two recent Iowa polls, putting Trump in a corner. Lo and behold, Trump opened fire on his rival this weekend. Speaking of Carson’s Christian denomination, he said, “I mean, Seventh-day Adventist, I don’t know about, I just don’t know about.” He also accused Carson of having “low energy,” the same attack he’s used on Jeb Bush.

This isn’t the first time Trump has attacked Carson. In September, the two traded barbs, but then quickly reconciled. In mid-October, Trump told George Stephanopoulos he wouldn’t attack Carson: “He’s been so nice to me, I can’t do it.”

But Trump, it seems, has had a change of heart. His broadsides against Jeb Bush as “low energy” seem to have been genuinely damaging. Carson, however, isn’t an establishment figure like Bush, and besides, his brand is his low-key demeanor. As with Sanders, it will be interesting to see whether going negative works for Trump. For now, both Trump and Sanders’s days of carefree sailing are over.

An Earthquake in Afghanistan

Updated at 12:11 p.m. ET

A powerful earthquake that hit a remote part of Afghanistan has killed dozens of people in the country as well as in neighboring Pakistan. The magnitude-7.5 quake was felt across Central Asia and in parts of India.

The quake knocked out power lines and communications, making the scale of the destruction unclear. The death toll, which according to various news reports exceeds 100, is expected to increase.

The BBC reported that at least 150 people had died, 123 of them in Pakistan. Thirty-three are reported dead in Afghanistan, including a dozen girls who were killed in a stampede after fleeing from their school following the quake. The Associated Press quoted Pakistani officials as saying at least 147 people were killed. Hundreds were injured in both countries. The AP also reported that two women died in Indian-administered Kashmir of heart attacks suffered during the quake.

Here are details about the quake from the U.S. Geological Survey:

470 DYFI responses listing "strong" to "very strong" near M7.5 Afghanistan epicenter. https://t.co/OR7fOv6bg5 pic.twitter.com/9gP0ksVAjQ

— USGS (@USGS) October 26, 2015

The quake’s epicenter was in the Hindu Kush mountain region, in the province of Badakhshan, the USGS said. The sparsely populated area borders Pakistan, Tajikistan, and China. The epicenter was 130 miles deep and 45 miles south of Fayzabad, the provincial capital.

USGS Shakemap showing intensity of shaking for affected areas around M7.5 in Afghanistan https://t.co/PvPc0NQrxW pic.twitter.com/ZmiBwPbaFR

— USGS (@USGS) October 26, 2015

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani sent his condolences to the families of those killed and to those who lost property, and set up a committee to ensure emergency aid quickly reaches those who need it.

Afghan Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah said on Twitter the quake was “the strongest one felt in recent decades.” He urged people to stay outdoors because of possible aftershocks. He said there were reports of damage in the northern and eastern provinces, but the extent was unclear because mobile-phone networks were down.

Here’s what the damage looks like in Afghanistan:

Damages after powerful earthquake in #Afghanistan @pajhwok pic.twitter.com/j657PdMoq9

— Sharif Amiry (@sharifamiry1) October 26, 2015

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi tweeted:

I have asked for an urgent assessment and we stand ready for assistance where required, including Afghanistan & Pakistan.

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) October 26, 2015

Here is video footage of the quake in New Delhi:

The Brownback Backlash

President Obama won barely a third of the vote in Kansas when he ran for reelection in 2012. Mitt Romney routed him by 22 points. Two years later, Sam Brownback beat back a fierce challenge to win a second term as the state’s governor and promptly used that four-point victory to claim public support for his “real-live experiment” in conservative fiscal policy.

Not so fast, Sam.

Nearly a year later, the Democratic president is suddenly a more popular figure in Kansas than the reelected Republican governor, according to a new poll. It’s not that Obama has won the hearts of voters in the heartland—just 28 percent of respondents said they were “very” or “somewhat satisfied” with the president’s performance. It’s that support for Brownback has fallen off a cliff in the midst of a difficult year that saw the tax policies he enacted early in his tenure lead to a gaping budget deficit. Just 18 percent of Kansas voters said they were satisfied or very satisfied with Brownback, while nearly half—48 percent—were “very dissatisfied” with his performance. More than three-fifths of respondents called Brownback’s tax policy either a “failure” or a “tremendous failure.” (By comparison, just 0.2 percent said it was a “tremendous success.”)

Now for the standard caveat: The annual Kansas Speaks survey by Fort Hays University was only one poll with a margin of error of 3.9 percent. And polls often show some level of voter remorse in the year after an election. In 2013, some national surveys found that Romney would have defeated Obama if voters had a do-over.

But rarely do a governor’s approval ratings tumble as dramatically as Brownback’s, and it’s a reflection of just how firmly Kansans have rejected his supply-side economic program. Working in concert with a Republican-controlled legislature, Brownback won approval for deep tax cuts both for individuals and businesses, which he claimed would lead to stronger job-creation and economic growth. But while the policy’s impact on jobs was debatable, its effect on the budget was not: Revenue projections consistently—and badly—missed their targets, and by early 2015, Brownback was forced to confront a projected deficit of $600 million. The governor blamed court-mandated increases in education spending, but he had no choice but to propose a slowing of the planned tax cuts and an increase in cigarette and other sales taxes to make up the difference. Lawmakers bickered for weeks before finally voting on a budget that, as even Brownback admitted, pleased no one.

The governor has crossed voters in other areas. The social conservative signed an executive order on “religious liberty” in July in response to the Supreme Court’s decision legalizing same-sex marriage. The poll released Sunday found that a plurality of voters supported gay marriage and a slim majority believed that business owners should have to provide the same services to gay couples as straight couples. Brownback signed a new voter-ID law in June, even though most Kansans—according to the survey—said voter fraud was no more than “a minor problem.” Yet Brownback’s tenure remains defined by his experiment with taxes. He has said repeatedly his goal is to reduce the income-tax rate to zero, but it’s possible his approval rating will get there first.

October 25, 2015

Should Literary Journals Charge Writers Just to Read Their Work?

It’s fall, the time of year when literary journals open their doors for new submissions. Around the country, writers are polishing poems, short stories, and essays in hopes of getting published in those small-but-competitive journals devoted to good writing. Though I’ve published short stories in the past, I’m not submitting any this year, and if things continue the way they have been, I may stop writing them altogether. The reason, in a nutshell, is reading fees—also called submission or service fees—which many literary journals now charge writers who want to be considered for publication. Writers pay a fee that usually ranges from $2 to $5—but sometimes goes as high as $25—and in return, the journal will either (most likely) reject or accept their submission and publish it. Even in the lucky case that a piece is published, most journals don’t pay writers for their work, making it a net loss either way.

If this seems like a reasonable practice, it’s worth noting that this model is nonexistent in the rest of publishing, where it’s always been free for writers to send their work to editors. In fact, literary agents who charge reading fees are usually considered shady, and writers are warned to stay away. But over the last few years, more and more literary journals have started charging fees, including well-known publications such as Ploughshares, New England Review, American Short Fiction, The Southern Review, and The Iowa Review. While most journals are still free, every few months, a new journal seems to announce that it’s going to start charging writers to submit their work—a trend that’s slowly threatening the inclusivity of literature when it comes to new, diverse voices.

A $3 fee might not sound like much, but the average short story might receive around 20 rejections before it’s published, meaning writers can be us much as $60 in the hole per story. Ideally, a writer is producing more than one story a year. If you’re trying to build a career—and yes, that’s still possible—you’re investing a lot just to get started, with no expectation of financial return.

To make matters worse, being poor is already the norm for writers. A recent industry survey showed that more than half of writers earn less than the federal poverty level of $11,670 a year from their work. I know what this feels like. There was a time when I made two cents per word as a writer and worked part-time as a waiter to pay the bills. I lived in a bad part of town, slept on a blow-up bed, ate on a card table, and owned a 1978 TV with a broken channel changer that I had to turn with a pair of pliers. When that was my life, these fees would have added up so quickly that I couldn’t have afforded to write fiction at all.

Reading fees also pose an extra obstacle to the literary community’s efforts to be more diverse. The fraught issue received renewed attention last month when a white man named Michael Derrick Hudson successfully published a poem in Ploughshares under a Chinese pseudonym that was later accepted into a prestigious anthology, The Best American Poetry 2015. The literary world was justifiably appalled by Hudson’s actions, which seemed an insult to the community’s goal of publishing more women, minorities, and other marginalized groups.

However sincere the intentions, saying that you want to hear from marginalized voices rings hollow against the literal barrier of the reading fee. It’s hard enough to submit to a system you’re outside of without having to pay to do it. Fees ensure that people who have disposable income will submit the most. So it’s fine to charge fees if you’re targeting mostly white, male writers who went to elite schools and who have a financial safety net. It’s not so great if you want to hear from the single mom working two jobs who writes poetry at night.

It’s hard enough to submit to a system you’re outside of without having to pay to do it.Surprisingly, the major reason literary journals charge fees has less to do with money, and more to do with the enormous number of submissions they receive. Around the country, MFA programs are graduating people who want to be writers, so they submit creative writing to literary journals. The journals, with small staffs and minuscule budgets, are overwhelmed with submissions and take a long time—sometimes six months to a year—to reply. Most writers can’t wait that long for a single response, so they send their work to more journals. The whole thing snowballs and soon these tiny publications are receiving hundreds, if not thousands, of submissions a month.

In some sense, then, writers are to blame for blanketing journals they haven’t even read with their work. The Internet has made this process easy: Do a search for “literary journals,” click on the websites, and fire away, submitting to one after another. Charging a fee, then, began as an attempt to slow electronic submissions down. The thinking was that if people had to pay to submit, maybe they’d consider what the journal was looking for and only send their best work. This attempt to force writers into behavior they should have been doing all along may seem reasonable until you consider that it doesn’t work. Instead of slowing things down, fees increased submissions 20 to 35 percent.

So the slush pile is getting bigger, but is it getting better? It’s unlikely, since professional writers with skill and experience are trying to get paid for their writing, not the other way around. Even if they make time to publish for free as a labor of love or because they want to build a literary reputation, they aren’t going to pay to submit. The people who do are likely novice writers who might think their submission will be taken more seriously because they paid for the privilege.

And yet journals don’t publish that much from the slush anyway; some estimates say it accounts for only 1 to 2 percent of published submissions. Instead, editors solicit work from writers they know, or writers who have name recognition. If a journal does pay its writers, it pays solicited people first. This produces an ethical problem: When a journal takes reading fees from the slush pile and then pays the writers they solicited, they’ve created an exploitative system where the unknown writers are funding the well-known ones.

While some journals only allow paid submissions, others have begun to allow writers to submit for “free” if they pay $20 to $50 for a yearly subscription—a policy that poses a similar financial burden. For other journals, the only free option is the now-antiquated process of mailing a hard copy of their submission. One of the most troubling arguments for reading fees is the idea that since writers don’t have to pay the post office to send online submissions, they should give the money to the journal instead. Look at it as supporting the community you love, some might say, like a tip jar. But it’s a flawed comparison—tips are optional, which means submission fees are more akin to being charged to audition for a play or to interview for a job. Instead, many writers like myself choose to support literature by buying work we like and subscribing to journals we admire, when we can afford to do so.

And yet it’s easy to sympathize with literary journals, many of which are struggling. The editors are often unpaid, the budgets from universities don’t always cover operating costs, and readership is small. Often it must feel like the only people paying attention are the ones trying to get published, people who, perversely, don’t buy or read the very journals they want to be in. A revenue stream, no matter how small, must be tempting. It’s harder to develop an audience, get advertisers, and apply for funding than it is to take money from the people sending in submissions. But if literary journals are about championing good writing, using prospective writers for revenue goes against the heart of that mission. Worse, it changes the journal from a publication with relevant content to something closer to a vanity press that exists as a place for MFA students to submit work.

If literary journals are about championing good writing, using prospective writers for revenue goes against the heart of that mission.Maybe it all comes down to this: It’s convenient for journals to charge fees because of submission software like Submittable. All an editor has to do is click a box requiring writers to pay, and she has an instant revenue stream. Meanwhile, Submittable takes a cut of every fee. Before Submittable came along, literary journals rarely charged fees, and the few that did, like Narrative Magazine, were an anomaly. Then a writer with a background in computer programming developed submission software with his partners and promoted it to the literary community, vowing that it would “always be free to indies.” Suddenly, there was an affordable (free) way to manage online submissions with an option to charge built right into the software.

These days, Submittable is used by NPR, Playboy, and the Harvard Review alike, and it’s no longer free for independent journals, though the company gives them a discount on pricing. While not the only submission software out there, it has become such a staple in the community that I’ve heard editors of smaller journals discuss charging fees just so they could afford Submittable—rather than using email, which is what most national magazines do.

However understandable the predicament of literary journals is, reading fees are ultimately exploitative. It’s bad enough that creative writers can’t expect to be paid for their work, but now they have to pay just to be considered. If all publications did this, there’d be no professional writers, only be people with other jobs who write on the side.

Clearly literary journals that charge fees are struggling to survive in the age of changing technology and may not fully realize the negative effects of their editorial policies. Aside from the fact that fees do nothing to solve the bigger issue of how to attract and keep readers, profiting off writers poses major problems for underrepresented voices in literature. And that should concern those of us who want to see more creative writing that reflects new perspectives—there’s just no way to tell who reading fees are pushing away.

October 24, 2015

Room: A Whole World in Four Walls

It’s hard to think of a movie adaptation of a book that feels truer and more loyal to its source than Room. In part, that’s thanks to the precise environment Emma Donoghue crafted in her Orange Prize-winning 2010 novel, the majority of which was set in an 11-foot by 11-foot insulated space with a lone skylight. But the book was also narrated in its entirety by a five-year-old boy, and much of its power and poignancy came from how well Donoghue captured the voice and perspective of such a small child—a much trickier endeavor for film, where childlike naivete and wonder can often become mawkish.

Room’s director, Lenny Abrahamson—whose most high-profile film previously was the offbeat Frank, starring Michael Fassbender as an eccentric musician who wears a large papier maché head—navigates the balance with remarkable finesse, working from a screenplay written by Donoghue. The movie opens with Jack (Jacob Tremblay) describing the events of his fifth birthday, and the details of the tiny universe he inhabits, Room. His Ma (Brie Larson), he explains, was alone in Room until he “zoomed down from heaven” to save her.

The agony of Donoghue’s book is in how long it takes to piece together the evidence given Jack’s limited capabilities as an interpreter, but here it’s soon clear that Ma and Jack are prisoners. Their only visitor is Old Nick (Sean Bridgers), who’s keeping them captive, and who rapes Ma while Jack sleeps in the closet.

When Old Nick reveals that he’s lost his job, and might also lose his house, Ma, realizing he will probably kill them both rather than let them escape, begins hatching a plan to set Jack free. In the space of a few days, she tries to teach Jack everything about the outside world—often a logical and philosophical conundrum as much as a practical one, since all he can see is empty sky. Room is unmistakably an allegory for the painful process of growing up, and here it’s rendered in rapid time, with Jack stubbornly resisting the puzzling, threatening barrage of new information, and Ma forced to move past his discomfort. Abrahamson punctuates these scenes with fierce suspense, adding urgency to Ma’s lessons in how to understand the world.

Perhaps it’s natural that an adult audience would see the events unfolding much more from Ma’s point of view than Jack’s, but it’s also a testament to Larson’s performance. She’s restrained but tightly coiled, practical and maternal, but also unpredictable. The world that Ma and Jack live in is one that Ma has made to protect and nourish her child as best she can—they exercise in the small space, read, and watch TV only for an hour a day, so it doesn’t “rot our brains,” as Jack explains. With Jack deprived of any social contact, every single item in Room becomes his friend: Wardrobe, Bed, Toilet, Lamp, Egg Snake (which they craft from leftover eggshells and hide under the bed). Tremblay is equally extraordinary in his role, imbuing tiny Jack with natural amounts of charm, courage, wit, and fear.

It’s hard to imagine that such a bleak scenario could be made so beautiful, but Abrahamson finds poetry in the small details of Room, captured through grey filters to emphasize the lack of light. More, though, the film captivates because of its central duo, who are each other’s whole world. As much as the audience empathizes with Jack, and feels his agony at losing what he interprets as a safe and familiar environment, so too they feel Ma’s pain in having to disrupt it.

Room is the kind of drama that feels tailor-made for theater, with its limited locales and emotional intensity. But it’s after Jack finally leaves the space for the first time that the potency of film is most felt—in its ability to express his wonder and confusion and discombobulation at seeing things he’d only experienced through a screen. It’s to Room’s credit that it makes that disorientation so visceral to viewers, communicating the angst and the elation of breaking free.

The Week the Rest of America Learned About RushCards

Over the past two weeks, people who use a RushCard prepaid debit card have struggled to buy food, been forced to go without medicine, and been anxiously unable to pay for rent, utilities, and other necessities. The technical glitch that left RushCard users unable to access their funds—which for many included entire paychecks—flooded Twitter and various media outlets. The hardships were heartbreaking, but they were also an important glimpse of what life is like in the U.S. for the tens of millions who struggle to maintain bank accounts.

For many, news of the RushCard problems brought up questions of what exactly these types of cards were—who uses them, and why? A report from Pew estimated that about 12 million adults use prepaid debit cards and the market has grown, with about $65 billion held on prepaid debit cards in 2012, which is double the amount on such cards only three years earlier. So with such fast growth, why is the world of these nebulous financial products still so poorly understood and largely overlooked?

More From Millennials: Forever Renters? Working From Home: Awesome or Awful? Are Public Universities Going to Disappear?

Millennials: Forever Renters? Working From Home: Awesome or Awful? Are Public Universities Going to Disappear? Until recently, the people most familiar with RushCards were likely those who had them, or who watched healthy doses of BET during the early aughts, where they were advertised heavily. The fact that the 12-year-old RushCard was launched by hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons doubled down on the targeting of this product to black consumers.

But it’s hardly the only product that used a combination of celebrity and economic vulnerability to push fee-heavy, less-regulated financial tools. There’s been a Lil Wayne Young Money card, and Suze Orman has been the face of a prepaid card too. There was the MAGIC Card from Magic Johnson, and, never a family to miss an opportunity for both alliteration and financial gain, Kim and company released the Kardashian Kard.

Users of prepaid cards are largely low-income, pulling in $30,000 or less. And nearly half of them have had a checking account forcibly closed, or closed one themselves due to problems with overdraft fees. That means that by and large, the Americans relying on prepaid cards are a group already struggling with the traditional banking system. They may have difficulty getting credit, or opening bank accounts if they’ve had one shuttered. They might also just not know about better options for free, or at least low-fee, checking accounts.

The upside here is that the scrutiny on RushCards could mean they, and similar products, will be more closely watched in the future. Many RushCard users reported that media attention helped them connect with the company’s customer-service employees to get their account issues resolved. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announced this week that it would launch an investigation into the mishap and debit-card provider’s response, and would work with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Trade Commission to ensure that all account issues were resolved. The CFPB also issued a statement on Facebook, saying, “It is outrageous that consumers have not had access to their money for more than a week. We are looking into this very troubling issue.”

Outrageous indeed. It’s unlikely that a situation like this—where Americans were left without access to their money for two weeks—would happen at a major bank. And if it did, customers, regulators, and the financial industry would have the power, backing, and incentive to act—quickly. Those who have already been marginalized by the financial industry don’t have as many options. Perhaps this glitch, and the ensuing scrutiny, will help to change that.

Tyler Oakley and Kidz Bop: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

The Kidz Bop Is All Right: A Night Alone With America’s Shrillest Pop Franchise

Jia Tolentino | Jezebel

“But we graduate away from ourselves constantly. The toddlers around me would never know what they looked like, bouncing on dad shoulders; the cliques of third-grade girlfriends dancing around me would forget all their old games, their jokes.”

Tyler Oakley’s Radical YouTube Memoir

Johannah King-Slutzky | The New Republic

“Anyway, who said YouTube ought to be political? Well, YouTubers did. That’s what makes YouTube so compelling and so infuriating. When we’re all annotating our own celebrity ... it’s difficult to distinguish between cases where the personal really is political and cases where that motto is appropriated for personal and uncritical gain.”

Terry Gross and the Art of Opening Up

Susan Burton | The New York Times Magazine

“‘Having the conversation’—that’s what’s compelling about the wish. It’s a wish not for recognition but for an experience. It’s a wish for Gross to locate your genius, even if that genius has not yet been expressed. It’s a wish to be seen as in a wish to be understood. The interview wish is as old as the form itself.”

Same Old Script

Aisha Harris | Slate

“Writers who speak up in the room aren’t just doing it out of a sense of political correctness. They’re doing it because they know that three-dimensional characters of color make their shows better—and because they know that white writers don’t always get it right.”

Why Sex That’s Consensual Can Still Be Bad. And Why We’re Not Talking About It.

Rebecca Traister | The Cut

“Young women don’t always enjoy sex—and not because of any innately feminine psychological or physical condition. The hetero (and non-hetero, but, let’s face it, mostly hetero) sex on offer to young women is not of very high quality, for reasons having to do with youthful ineptitude and tenderness of hearts, sure, but also the fact that the game remains rigged.”

Crusader Chic

Danielle Peterson Searls | Lapham’s Quarterly

“It is worth emphasizing that the new desires for exotic clothing started with men, not women. In fact, the Crusader epics are more likely to focus on the textiles worn by horses. In one tale a sultan, wanting to tempt the hero Godfrey of Bouillon with his wealth, is advised to bring out his white Arabian charger. While Godfrey resists, the poet and his audience succumb—not to the horse’s size and strength, but to its dazzling accessories.”

Capes & Crossovers: How Franchises Invaded Television

Andy Greenwald | Grantland

“And so we reach the part of the column where you would expect me to decry this dogged, interlacing brand-building as corporate avarice run amok, further proof of the golden age of television’s sad descent into plastic ideas. But I can’t do it. The truth is, shared universes are one of storytelling’s greatest joys.”

We Embraced the Future and It Nearly Killed Us

Hal Niedzviecki | Literary Hub

“Escape from future shock won’t come from lamenting the rise of a techno-industrial age and trying to push back against it by what the Tofflers dismiss as a ‘return to passivity, mysticism and irrationality.’ The answer isn’t to question the path we’re on. The answer is to fully embrace the potential of the one and only path—future change all the time. We must merge with the future and go wherever that takes us.”

What Would Barthes Think of His Hermès Scarf?

Christy Wampole | The New Yorker

“Nearly everyone in the middle class, particularly those under 40 or so, spends a significant amount of their waking hours consuming and critiquing television shows, commercials, apps, objects and their design, political performances, celebrity behavior, and brands on the Internet. Perhaps without ever having read him, they are imitating Barthes’s approach to culture.”

Bill Murray Just Needs to Start Making Good Movies Again

Mike Ryan | Uproxx

“Bill Murray has quietly made a lot of bad movies since Lost in Translation, and no one has noticed because everyone is so damned enamored of Bill Murray ‘being Bill Murray.’ You are not helping him. You are enabling him. Deep down, Murray still wants that Oscar. He’s never going to get it as long as we think it’s just so great that he shows up on Jimmy Kimmel wearing a costume.”

October 23, 2015

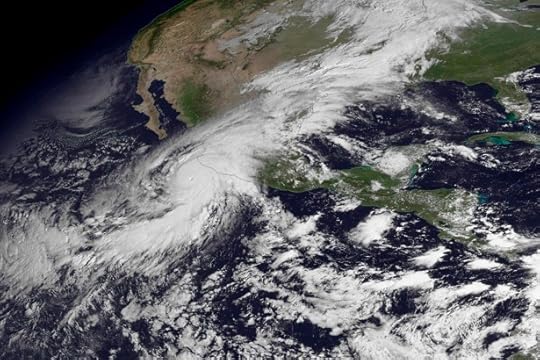

How Did Hurricane Patricia Intensify So Quickly?

Hurricanes really aren’t supposed to get stronger than Hurricane Patricia.

That’s not hyperbole. Hurricanes shouldn’t see sustained winds above 190 miles per hour in Earth’s modern-day climate. Yet on Friday morning, Patricia’s winds were measured at about 200 miles per hour.

That’s not the only exceptional aspect of the storm. The category-five tropical cyclone, now spinning off the western coast of Mexico, is expected to make landfall Friday evening. It will be the second-strongest storm to make landfall in history, after Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines 2013.

Remarkably, it only holds that “second strongest” title because it has weakened slightly in the past few hours. On Friday morning, Patricia was the strongest storm ever measured by the U.S. National Hurricane Center, which has monitored all storms in the Atlantic and north Pacific for the past half-century.

Patricia got extremely strong, extremely fast. Late Wednesday evening, it was merely a strong tropical storm, with peak winds of 65 miles per hour. By the following morning, it had become a category-one hurricane; and by Friday morning, it had exceeded records.

How did it intensify so quickly? Falko Judt, a meteorologist at the University of Miami who studies hurricane intensity, said the intensification wasn’t entirely unexpected. It’s just that almost everything that could go the cyclone’s way, did.

The two major factors that govern hurricane intensity, Judt said, are ocean temperature and wind shear. The ocean-surface temperature was very warm under Patricia—it was measured at 31 degrees Celsius, or more than 87 degrees Fahrenheit—which provided the storm with a lot of fuel. At the same time, wind shear was very low, which meant that wind was blowing in the same direction across multiple levels of atmosphere and there was little frictional drag on the storm.

Judt said that these two factors were aided further by very high humidity locally.

“It’s not totally unexpected to me that it intensified so quickly,” he told me. “Everything looked toward it becoming a strong hurricane. It’s just incredible how strong it got.”

What drove that strength?

Judt said that he thought El Niño played a large role. El Niño is a Pacific Ocean-spanning climate phenomenon, in which the eastern part of the ocean, near the equator, becomes warmer than usual. The central and western Pacific in turn become cooler. The effects of the climatological phenomenon are felt across the globe, which causes droughts in Australia and Ethiopia and deluges in California.

“The largest signal of El Niño is around the equator, so it tapers off at higher and lower latitudes. But Mexico is still close enough that it feels the effects,” he said.“It’s always hard to attribute one single storm to a larger phenomenon like El Niño, but it most likely did play a role.”

(Did climate change also affect the storm? Meteorologists are still debating how much global warming drove this year’s especially strong El Niño. Over at Slate, the meteorologist Eric Holthaus discusses how climate change has shaped Patricia in particular.)

Some forecasters have proposed that, to measure the planet’s increasingly strong storms, more categories should be tacked on to the end of the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale is used to measure hurricane intensity. Right now, that scale only counts to five, which equates to wind speeds over 155 miles per hour. On an expanded scale, Hurricane Patricia might qualify as a seven:

Recall suggestion for addition of Category 6 to Saffir Simpson scale? If extrapolated further, Hurricane #Patricia would be Category 7.

— Ryan Maue (@RyanMaue) October 23, 2015

Judt, however, wasn’t as sure that an expanded scale was needed. Hurricane categories don’t need to measure beyond 150 miles per hour, he said, because winds at that speed cause the maximum level of destruction possible.

“I’m reluctant to change categories because categories are based on wind destruction,” he said. “Everything is destroyed in a Category Five, so everything of course will be destroyed in a Category Six, too. You can’t really assess how bad [a storm] was because everything is destroyed anyway, as bad as that sounds.”

He did note, though, that the hurricane seemed to meet or even exceed its maximum potential intensity. That’s a way of predicting cyclone intensity developed in the late 1990s by the climatologists Marja Bister and Kerry Emanuel.

Emanuel, now a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told me Friday that his maps had correctly predicted the hurricane’s intensity: They had predicted winds as strong as 207 miles per hour, and those at 200 miles per hour had been recorded. But it was rare, he said, that a storm actually achieves its potential.

“Very few storms make it right to their speed limit,” he said. “This hurricane happened to develop in a place where its unusually strong.”

Judt echoed that statement. “Globally, at the moment, storms couldn’t get any stronger than that anywhere in the planet. Patricia found the sweet spot,” he said.

And Emanuel also added that it was possible for a tropical cyclone to have winds stronger than 200 miles per hour—but not with ocean temperatures like those in the Pacific. “In a different climate, or in a different place and time, it could just go as well with a higher number,” he said.

No Charges for Lois Lerner

The Justice Department says that while it found “substantial evidence of mismanagement, poor judgment and institutional inertia” at the IRS, it found no evidence of a crime in the way the department treated conservative organizations. The determination, which came in a letter to Congress on Friday, means no charges will be brought against any IRS officials, including Lois Lerner, the former IRS official at the center of the scandal.

“Our investigation uncovered substantial evidence of mismanagement, poor judgment and institutional inertia leading to the belief by many tax-exempt applicants that the IRS targeted them based on their political viewpoints,” Assistant Attorney General Peter Kadzik said in a letter to the House Ways and Means Committee. “But poor management is not a crime. We found no evidence that that any IRS official acted based on political discriminatory, corrupt or other inappropriate motives that would support a criminal prosecution.”

At issue is the scandal that involved the IRS’s decision to hold up applications by Tea Party-related groups for tax-exempt status. An inspector general’s audit found that the criteria used by the agency for its decisions were inappropriate. Lerner, who headed the IRS’s Exempt Organizations Division, became the key figure in the scandal. Here’s more from USA Today:

The “targeting” began in 2010 during the emergence of the Tea Party movement, when Lerner was the director of Exempt Organizations for the IRS. A 2011 list of groups held up for review obtained by USA TODAY showed that 80% were conservative, although a number of liberal groups had similar problems.

Last year, Lerner denied any wrongdoing and invoked her Fifth Amendment rights, declining to testify before the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee about her role—a move for which she was held in contempt of Congress. She is now retired.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower