Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 240

February 2, 2016

My, Look How They've Grown

On Tuesday morning, the market was ready to crown a new firm as the most-valuable public company. The market capitalization of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, soared to $570 billion after the release of solid earnings numbers—which surpassed Apple’s $535 billion. By midday, the companies both hovered below $530 billion.

The “war” for the top spot between Alphabet and Apple is unlikely to end anytime soon, as one good (or bad) earnings report can be enough to shift the balance. That’s exactly what happened this week. Last summer, Google announced that it would be reorganizing its operations under a parent company, called Alphabet, so investors could have a better view of what was really going on in each of its ventures. After investors took a look at these finances and liked what they saw on Monday, Alphabet was poised to overtake Apple when the markets opened the following day.

Regardless of which company’s valuation happens to be highest during any given quarter, it’s pretty astounding that both are past halfway to a trillion dollars. How did they get so large? First, these are two tech companies that have been incredibly successful at getting millions of people to use their services or products—the iPhone for Apple, and search for Google.

Secondly, like other tech giants before them, both Apple and Google have been prolific acquirers. Google has been the more prolific of the two—since 1998, it’s estimated that Google has bought more than 170 companies and has spent some $24 billion on its 10 most expensive buys. (Though last year, the company seemed to have slowed down in its M&A activity.) On the other hand, Apple was reportedly not seriously in the game of acquisitions until 2009, but its most memorable buy in recent memory is its $3 billion purchase of Beats in 2014.

They are not exceptions. Companies in the U.S. and beyond have been getting bigger and bigger. According to data compiled by FiveThirtyEight, not only are more companies getting larger, but the largest are growing at a faster pace. M&A is part of the reason: 2015 was a record year for mergers and acquisitions, and 2016 is expected to be similar, as cash-rich companies often see dealmaking as the best way to spend in the current economic environment. But the big-company trend has been going on for longer than that. According to The Economist, huge firms have been steadily getting huger for decades. Worryingly, though, recent studies have found that this may come with wider costs: The gigantic companies of today are not producing as many American jobs as the giant companies before them.

The Zika Cases in the United States

The Zika virus has been transmitted in the United States for the first time through sexual contact, health officials said.

The case in Dallas County in Texas was confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tuesday. Until now, the more than 30 cases of the virus reported in the continental U.S. were among travelers who returned to the country from Latin America, which, particularly Brazil, has seen a spike in Zika cases in recent months.

The individual in Texas was infected with the mosquito-borne virus after having sexual contact with a Zika-infected person who had traveled to a country where the virus is present, according to the Dallas County Health and Human Services. The virus is usually transmitted by mosquito bites.

“Now that we know Zika virus can be transmitted through sex, this increases our awareness campaign in educating the public about protecting themselves and others,” said Zachary Thompson, the Dallas health department’s director. “Next to abstinence, condoms are the best prevention method against any sexually-transmitted infections.”

Zika is primarily transmitted through Aedes mosquitoes, the same insects that spread the dengue and Chikungunya viruses. About 1 in 5 people infected with the virus will get sick. The CDC says the disease is usually mild, and those disease and those who do get sick show symptoms—fever, rash, joint pain, and red eyes—for up to a week. But the virus has been linked to a condition called microcephaly in babies born to infected mothers in Latin America and the Caribbean. Infants born with microcephaly have smaller-than-normal head size, which can result in severe cognitive, neurological, and motor disabilities. In Brazil, which saw its first case of Zika last May, there were 20 times more microcephaly cases in 2015 than in 2014.

There is no specific medical treatment or vaccine for the Zika virus, though several pharmaceutical companies say they are working on one. There is no vaccine.

It is unclear whether after this case of sexual transmission the CDC will designate the continental U.S. an area where Zika is locally transmitted. Cases of the virus have been reported in Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, and 21 nations, as well as three French and two Dutch territories in the Caribbean, according to the CDC. Transmission by mosquitos has not been reported in the continental U.S.

The World Health Organization on Monday designated the spread of the virus and the increase in cases of microcephaly a public-health emergency of international concern. The classification—the most serious action the organization can take—is intended to galvanize an international response to the virus. It’s rare, too: WHO previously declared such emergencies in the Ebola and polio outbreaks in 2014 and the H1n1, or swine flu, outbreak in 2009.

Some governments in Latin America advised women to hold off on having children as the outbreak grows. Brazil and Colombia have suggested women avoid getting pregnant for several months, while El Salvador has asked them to wait until 2018.

Health officials have advised the public to use insect repellant, protect skin with long-sleeved shirts and pants, remove standing water—the breeding grounds for mosquitos—in and around their homes, and avoid being outside at dusk and dawn, when the bugs feed.

Which Is the Fastest-Talking State in the Union?

“Life is short. Talk fast,” Gilmore Girls advises. It may well be a good tip: There are some distinct advantages to being a motormouth, among them conversational efficiency and—some research suggests—a general perception that fast-talkers are smarter than their slower-speeched peers. So, sure, if you count yourself among the world’s fast-talkers, that could be a sign of your intelligence. Or of your impatience. Or of nothing at all.

Related Story

Congratulations, Ohio! You Are the Sweariest State in the Union

Or! It could be a sign that you’re from Oregon.

Yes. Oregon. The Beaver State, according to a new analysis of consumer phone calls—placed to businesses across the country, and recorded anonymously—is home to the Lorelai Gilmore-iest, Jackie Chiles-iest speakers in the nation. The second-fastest talkers? They’re in Minnesota. The third? In Massachusetts.

The slowest talkers, for their part, can be found in the South: in South Carolina, Louisiana, and—the most laconically languaged state of them all—Mississippi.

To arrive at those state-by-state breakdowns, the analytics firm Marchex used what it calls Call DNA technology—software that analyzes call recordings to determine things like rate of speech, density of speech, hold times, and silences—on a set of calls recorded between 2013 and 2015. (These are the recordings that result when a pleasant robo-voice informs you that “this call may be recorded.” Marchex’s analysis includes more than 4 million such calls.)

The fastest talkers are in Oregon. The second-fastest are in Minnesota. And the slowest? In Mississippi.

The full ranking of states, from the fastest-talking to the slowest:

1. Oregon

2. Minnesota

3. Massachusetts

4. Kansas

5. Iowa

6. Vermont

7. Alaska

8. South Dakota

9. New Hampshire

10. Nebraska

11. Connecticut

12. North Dakota

13. Washington

14. Wisconsin

15. Rhode Island

16. Idaho

17. Florida

18. Pennsylvania

19. New Jersey

20. West Virginia

21. Maine

22. Colorado

23. California

24. Missouri

25. Montana

26. Indiana

27. Hawaii

28. Virginia

29. Nevada

30. Arizona

31. Utah

32. Michigan

33. Tennessee

34. Maryland

35. Oklahoma

36. Wyoming

37. Delaware

38. New York

39. Kentucky

40. Illinois

41. Ohio

42. Arkansas

43. Georgia

44. Texas

45. New Mexico

46. North Carolina

47. Alabama

48. South Carolina

49. Louisiana

50. Mississippi

In some sense, Marchex’s findings hew to cultural stereotypes. The fast-talkers are concentrated in the North; the slow-talkers are concentrated in the South. (Speed-speech-y Florida is an outlier whose fast-talking ways can likely be explained by both the state’s high concentration of Spanish speakers and the fact that many of its residents are transplants from faster-talking states.) Here, in other words, is a state’s culture directly affecting that most intimate of things: the way people speak. It’s all very Geography of Time.

Marchex

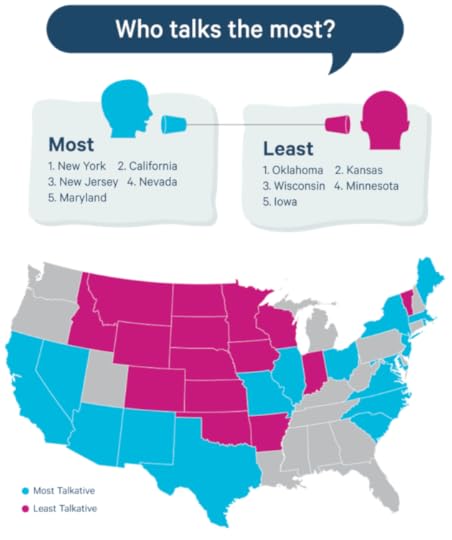

But speedy speech doesn’t necessarily equate to dense speech. Marchex also used its dataset to analyze the wordiest speakers, state by state—the callers who, regardless of their tempo, used the most words during their interactions with customer service agents.

That breakdown looked like this:

Marchex

The variation here is significant. What the word-density differences amount to, Marchex notes, is that, for example, “a New Yorker will use 62 percent more words than someone from Iowa to have the same conversation with a business, according to our data.” And, again, the linguistic variations hint at cultural ones. Some of the slower-talking states (Texas, New Mexico, Virginia, etc.) are also some of the wordier, suggesting a premium on connection over efficiency. Some of the fastest-talking states (Idaho, Wyoming, New Hampshire) are also some of the least talkative, suggesting the get-down-to-business mentality commonly associated with those states.

Here is a state’s culture directly affecting that most intimate of things: the way people speak.

And what of that most communicative form of language—silence? Marchex also considered the holding patterns of the calls it analyzed, noting whether callers who were put on hold during their interactions with businesses hung up or hung on.

The states in green, below, are the ones whose residents were most likely to hang up after being put on hold. The states in pink are the ones whose residents stuck around until their calls resumed.

Marchex

It’s not so much a North-South divide as it is, very roughly, a regional one: The most impatient people here are congregated within the Northeast, the mid-Atlantic, and the upper Midwest. And the most patient can be found in the Midwest and the South. Perhaps, as well, it’s not surprising that Ohio would distinguish itself, in this analysis, for its impatience; a previous Marchex study found that the Buckeye State carries the dubious distinction of being the most profanity-prone of these United States.

Music Sales Are Music PR

When people talk about commercial success in popular music, they’re often talking about one of three concepts. There’s the reach of a work of music—the number of listeners it gets. There’s perception, or bragging rights. And there’s the money made—arguably the most important metric, almost entirely obscured from public view.

The announcement that the Recording Industry of America will now count on-demand streaming figures when doling out Gold and Platinum certifications for albums means such certifications will better reflect the first aforementioned category: actual listenership. Over the past few years, more and more people have stopped paying to download or physically own albums and started instead consuming music on platforms like Spotify, YouTube, and Apple Music (Pandora, too, but because you don’t get to pick individual songs its data still won’t factor into RIAA certifications). The RIAA’s rule change means those people can push an album to Gold or Platinum status, and that’s a good thing if certification is meant to capture real marketplace interest in a musical work.

But the rule switch-up also makes understanding what exactly Gold or Platinum status means more difficult than ever before. Until now, Gold indicated at least 500,000 copies sold in stores or through platforms like iTunes, while Platinum indicated a million. Now, those numbers are the sum of sales and the equivalent of sales. The formula for equivalency: “1,500 on-demand audio and/or video song streams = 10 track sales = 1 album sale.” The question of whether that’s a “fair” calculation is inherently unanswerable. What’s clear is that certifications will go from being a cut-and-dry benchmark to an approximation.

Should the public mind? Probably not. An album sells what it sells regardless of certification; certificates are only handed out after a record company or musician puts in an application for one. For artists, the incentive to do so is the same incentive to pursue any kind of award: recognition for hard work. For everyone else, Gold and Platinum plaques have always been about that second idea of musical success that I mentioned earlier: appearances. Certificates allow musicians and their record companies to market themselves as successful. They give fans ammo in their online wars against rival fandoms. The RIAA’s own press release makes certifications sound like promotional gimmicks:

Gold & Platinum recognition is often among the most celebrated news in an artist’s social media feed. The RIAA utilizes a myriad of social media platforms – Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipagram, and a YouTube page – to market and publicize artist award achievements. The RIAA also recently unveiled a new RIAA.com and Gold & Platinum database where fans can more easily search and share the award recognition.

That third version of commercial success, how much money a song or album has made, remains hard to talk about. Remember, RIAA awards are a marker of thresholds—an album can sell anywhere between 1,000,000 and 1,999,999 copies and still be Platinum. The other widely used commercial metric in music, Nielsen Soundscan, does keep precise sales and streaming totals, but much of that is only available to subscribers. The Billboard charts simply use those totals to render success in the relative terms of a ranking. And even when the public does know the full consumption figures for a work of music, that’s far from a full portrait of financial success.

It’s always been the case that the amount an artist makes from an individual sale—as opposed to how much the record company or distributor profits—has been confidential. But today, the picture is even less clear. That’s in part because streaming payouts are famously complicated and mutable. It’s also because in many cases, profitability has been largely decoupled from sales in favor of merchandising, touring, and, of increasing importance, sponsorships.

Take the case of Rihanna’s new album, Anti. On Friday, The New York Times reported that by Nielsen’s count, only 460 copies had been sold. That’s a shockingly low number, but as the reporter Ben Sisario wrote, it’s surely so small only because of quirks of rules and timing. As I wrote the same day, the RIAA certified Anti platinum within 14 hours of it hitting the Internet—apparently because Samsung, with whom Rihanna’s signed a reported $25 million marketing deal, bought up a million album copies that were then gifted to fans who typed in a download code. Nielsen doesn’t count such free promotions in its numbers; the RIAA does, on the theory that they still reflect consumer demand for an album. One measure of counting is certainly better for Rihanna’s publicity machine. Neither tells anyone how much money she’s made.

A Federal Criminal Investigation in Flint

The poisoning of Flint’s population with lead is a human tragedy, and a story about the failure of government to protect its citizens. But is it a crime, too?

The FBI might be looking into that question, the Detroit Free Press reports Tuesday. The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Detroit said almost a month ago it was working on an investigation of the man-made disaster, but it wouldn’t say whether that inquiry was criminal or civil. It now appears the answer is criminal, as officials told the Freep the team includes the FBI, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the EPA’s Office of Inspector General Criminal Investigation Division.

Related Story

The obvious, and unanswered, question now is who might be prosecuted and for what crimes. There’s plenty of blame to go around: City and state officials knew about problems with the water for months before taking action, downplaying the risks or simply saying they were someone else’s problem. The director of the state Department of Environmental Quality has been fired. EPA also failed to stop the disaster, saying it was the state’s responsibility; the regional director for the agency has resigned in the wake of that revelation.

The federal task force isn’t the only group investigating Flint. Governor Rick Snyder has appointed a task force, and state Attorney General Bill Schuette has also launched an investigation. The U.S. House Oversight Committee is holding hearings as well.

Much of the scrutiny, and fury, centers on the role of Darnell Earley, who was Flint’s emergency manager when it began drawing its drinking water from the Flint River. The city had elected to stop using Detroit’s water system, but Detroit terminated Flint’s contract before a replacement pipeline was built, leading Flint to use the river. But the Flint River’s water, which has a higher chloride content than the water from Lake Huron that Detroit uses, corroded Flint’s aging lead pipes, bringing the metal into the water supply—a problem that continues even after Flint went back to the Detroit system.

Earley was appointed by Snyder under Michigan’s much-maligned emergency-manager law, which grants the state the ability to bring in administrators to run troubled cities. Earley was called by the House Oversight Committee, but has apparently declined to testify. After leaving Flint, he became emergency manager of the Detroit Public Schools, and controversy has dogged him in that job, too—and he will step down from the job February 29. As the Freep reports, the Flint disaster is just one factor:

Earley has faced growing criticism in recent months both for what happened Flint and the problems within DPS such as crowded classrooms, dilapidated schools and a growing debt. Teachers have staged several sick-outs in recent weeks to protest the mold, water damage and rodent problems in some of the city's older schools, saying Earley had ignored their complaints.

Alexander Chee on What Writing Parties Reveals About Characters

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

A few years ago, the publishing imprint Picador asked writers to share their favorite party scenes from literature. Many classics were cited—the finale of Mrs. Dalloway, Joyce’s winter-bleak “The Dead,” Bilbo’s birthday celebration in The Fellowship of the Ring, Jay Gatsby’s wild Friday nights. But one writer, the award-winning novelist Jim Crace, had a different take. “I hate parties,” he wrote. “Come on, admit it, everyone hates parties. Stop pretending.”

It’s a reminder that parties, as fun as they can be, often also provoke profound anxiety and dread—and that dichotomy is one reason Alexander Chee, author of The Queen of the Night, loves writing about them. For Chee, parties are essential dramatic tools in fiction: They’re supercharged with action, intrigue, and uncertainty. In our conversation for this series, Chee looked closely at a pivotal scene in Charlotte Bronte’s Villette, where a play is put on during a lavish ball. In Chee’s view, Bronte offers an apt metaphor for how parties work: We’re all acting, and the roles we choose and costumes we wear say everything about us.

It’s been almost 15 years since Chee’s acclaimed first novel, Edinburgh, was published in 2001. It’s clear why this one took him so long: The Queen of the Night is a multi-stranded, thoroughly researched epic about the world of 19th-century French opera. The main character, a soprano with a harrowing past she is ashamed of, is offered a starring role in an production written specifically for her by an anonymous composer; to her horror, she discovers that the work contains details about her secret life. In our discussion, Chee explained how Villette helped him become more comfortable writing about 19th-century mores, and imbue performance scenes with dramatic force.

Chee’s essays and stories have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Tin House, Slate, Guernica, NPR, and Out, among others. The winner of a 2003 Whiting Award, he inspired the idea for the much-discussed “Amtrak residency” and curates the Dear Reader reading series in New York City, where he lives.

Alexander Chee: I had a writing teacher once who told us writers should never describe parties. If possible, she said, we should avoid it. It might have been her own disinclination for parties, even though she seemed to be a very social person. Or it may have been that she was simply tired of the way undergraduates wrote about parties. But her advice made the description of parties incredibly taboo to me, and gradually, I knew, I would have to write about them.

The qualities that make parties such a nightmare for people—and also so pleasurable—make them incredibly important inside of fiction. There’s a chaos agent quality to them: You just don’t know who’s going to be there, or why. You could run into an old enemy, an old friend, an old friend who’s become an enemy. You could run into an ex-lover, or your next lover. The stakes are all there, and that’s why they’re so fascinating.

In my first novel, there’s a party scene that I’m incredibly proud of, which I would hold up as a model to anyone. But that was the kind of party I was very used to—kids in college, someone’s family isn’t home—which made it easy to write. My new novel presented a very different challenge. I had zero experience with the parties of the 19th century. (Most of us alive, I guess you could say, really don’t.) When you’re writing historical fiction you have to think a little farther into the situation: what the average social interactions were, what was acceptable behavior. What did people think was fun, what did they find unhappy, and why?

I knew I wanted the parties in The Queen of the Night to be convincing, beautiful, and also dramatic, situations where significant things happened on a scale that was both grand and intimate.

There were several texts that helped me think about how to do this and one of the most important ones was Charlotte Bronte’s novel Villette. The heroine, Lucy Snowe, is not particularly beautiful, but is incredibly intelligent, and was born into unfortunate circumstances. She has ruthless standards of behavior for herself and others that she believes protects her, and so parties are almost like battles for her, over her identity, even her soul.

There’s a party in Chapter XIV, “The Fete,” which beautifully demonstrates the dramatic stakes. Lucy has left England for France, and is working as a teacher at a boarding school for young women there. The party is an annual one, celebrating the headmistress, Madame Beck, and involves a short play performed in her honor as well as dancing.

You could run into an old enemy, an old friend, an old friend who’s become an enemy.

On the grand scale, it brings out the world of the novel and the larger political context of the era. The students and teachers are from different parts of the world, and there’s a lot of commentary about what is English and what is French, so their two nations’ longstanding conflict with each other gets rendered as a sort of banter. That was useful for me to see as the parties in The Queen of the Night have international guests, some of them very important diplomatic or aristocratic figures, some of whom had been at war or were about to be at war, or were spying on each other. Seeing how that plays itself out in the minutiae of these parties was part of what I was looking for.

But “The Fete” does its best on a smaller scale, bringing out dynamics between the main characters. One of the things that’s really important in Queen of the Night is how people communicate with their clothes. We start to see that, here, before the party even begins. There’s a great scene where Lucy is thinking about how everyone will dress, and also how she will dress, and is anxious about it. As she watches a group of young girls preparing for the evening, dressed in muslin, she can’t see herself in their brilliant white outfits:

In beholding this diaphanous and snowy mass, I well remember feeling myself to be a mere shadowy spot on a field of light; the courage was not in me to put on a transparent white dress: something thin I must wear—the weather and rooms being too hot to give substantial fabrics sufferance, so I had sought through a dozen shops till I lit upon a crape-like material of purple-gray—the colour, in short, of dun mist, lying on a moor in bloom. My tailleuse had kindly made it as well as she could: because, as she judiciously observed, it was “si triste—si pen voyant,” care in the fashion was the more imperative: it was well she took this view of the matter, for I, had no flower, no jewel to relieve it: and, what was more, I had no natural rose of complexion.

We become oblivious of these deficiencies in the uniform routine of daily drudgery, but they will force upon us their unwelcome blank on those bright occasions when beauty should shine.

However, in this same gown of shadow, I felt at home and at ease; an advantage I should not have enjoyed in anything more brilliant or striking.

Lucy is anxious to look appropriate to the situation even as she does not want to draw attention to herself. She’s hoping to choose her dramatic role in the evening, aware that the whole thing is a play of a kind, not just the one rehearsed event. Party clothes say so much about what someone wants to communicate to other people about themselves, as well as what they’re also feeling about themselves, and whether what they’re making makes them feel more or less powerful. And the “gown of shadow,” is such a fantastic phrase: turning her mousy attire into something transfiguring and even powerful for a brief moment. At the beginning of that section she’s a shadowy spot on a field of light. And by the end of that description, she’s the gown of shadow.

And, as I read it, I can see how this phrase, “gown of shadow” became incredibly important as an image in my own novel, and I suspect this is where it comes from. Also this sense of being dressed and hidden at the same time.

In fiction, I think, you’re always working with who your characters are and who they believe they are. You’re telling a story that’s about both of those people. At a party you see, most of all, who they aspire to be, a kind of theatrical role they hope to assume—it’s not just Lucy Snowe doing this. And so the costume we are in, as it were, matters hugely—and Bronte makes that overt in this scene, when an emergency requires Lucy to play a part in the little play that’s going to be put on: One of the male actors has fallen ill, and she’s forced to step in. She’s told she must dress as a man for this. And so, she’s unwillingly being drawn into the center of attention even as she’s already being disguised by the costume that she must wear. That is a wonderful paradox of forces to subject someone like Lucy to—someone who is hoping to simply wear that gown of shadow and slip by, watching from the edges and certainly not be at the center of attention.

These kinds of entertainments were very common back then; it was typical, at these parties, to have a tableau vivant or charade, play, or operetta, as part of the game of the evening. The play doubles as a kind of metaphor for the way a party brings out certain elements of a character’s personality, and Bronte pulls that off masterfully here.

At a party you see, most of all, who they aspire to be, a kind of theatrical role they hope to assume.

Lucy refuses to wear a man’s clothes—and instead consents to wear some of each, becoming kind of a hermaphoditic presence—and this affects the way the other characters, especially the female characters, relate to her as the night goes on. Meanwhile, one of the other characters, Ginevra, plays the coquette between two suitors, one of whom is the character Lucy is playing—and this is a role Lucy will continue inhabiting during the rest of the evening. For both, the drama they perform in becomes truer than might have been thought.

With this, Charlotte Bronte introduces a story within a story, another thing that I wanted to do in The Queen of the Night with my character who fears her voice is cursed, dooming her to repeat the fates of the characters she’s performed. This kind of doubling was important for me to create throughout the novel.

And so I really disagree with my old writing teacher. It’s a commonplace of teaching writing that the story really takes off when your characters speak to each other. But I think when your characters go to a party, so much more is possible than can happen in just a simple conversation. The kinds of surprising developments here are exactly what you want to have come forward in the novel. Parties aren’t to be avoided—they could even be said to be paramount.

Ben Carson's Campaign Is Spending Like Crazy

During the fall, an interesting double dynamic enveloped the Ben Carson campaign. The outsider candidate was starting to surprise political observers with his strong performance and especially his exceptional fundraising numbers—some of the strongest in the field, beating the long-established GOP bigwigs. The huge hauls were driven by small-dollar donations, not big checks. On the one hand, people outside the campaign were impressed. On the other hand, they looked at the huge amounts Carson was spending on direct mail and telemarketing and wondered whether the strategy was sustainable, or even ethical.

When I asked the Carson campaign about this in October, then-spokesman Doug Watts gamely explained that the point was to build up a fundraising list. Carson, as a first-time politician, had to build up a database of supporters. Sure, many of the campaign’s donors were small-dollar givers identified by telemarketers, but once they were in the system, they’d keep giving, Watts promised.

Related Story

Where Is Ben Carson's Money Going?

“Strategically it was our plan to build a donor base,” he said. “There’s only one way you do that—you invest in prospecting in direct mail, prospecting in telemarketing, prospecting online. Prospecting is expensive.” But he said the campaign expected its heavy reliance on direct marketing and telemarketing to drop as the list built.

Watts is no longer with the campaign, having quit in frustration in December, but Carson’s year-end FEC report, released Sunday, suggests that far from decreasing its reliance on these methods, the campaign has only become more reliant on them. The campaign raised $22.6 million, but it spent $27.3 million, and closes out with just $6.6 million cash on hand. (For comparison, Ted Cruz has $18.7 million on hand; Hillary Clinton has $38 million.) Among the largest spending areas, a couple stick out: fundraising phone calls ($2.4 million), and postage and printing ($7.3 million). So do several of the largest payees:

Action Mailers, $4.5 million

CMDI, $1.4 million

Communication Management Source, $1.3 million

Direct Advantage, $3 million

Eleventy Marketing, $4.8 million

InfoCision, $2.4 million

TMA Direct, $2.9 million

Together, these vendors account for $21.2 million, the vast majority of what Carson spent in the fourth quarter.

Most of these companies are involved in either direct mail or telemarketing for fundraising. Every campaign uses these methods, but they’re very expensive—you have to spend a lot of money to make money—the Carson campaign’s heavy reliance on them fed two allegations. Some observers felt the campaign was unfairly targeting naive low-dollar donors; and either way, the fact that many of the vendors doing the pricey work were connected to the campaign made it look like they were treating the Carson for president push as a way to line their own pockets.

This filing doesn’t do much to assuage those concerns. For example, TMA is run by Mark Murray, one of Carson’s top fundraisers. Murray has also long worked with Eleventy and InfoCision, two Akron, Ohio-based companies. InfoCision has been implicated in past scams. Eleventy’s president is chief marketing officer for Carson. Communication Management Source is run by Joanne Parker, whose husband Dean Parker departed the campaign in December.

Can the Carson campaign do more than just fundraise? In Iowa, he won three delegates, at a cost of $47.5 million so far. It’s hard to see what sort of future it has after the Hawkeye State. Carson came in fourth in Iowa, and things only get rougher from here. In New Hampshire, he’s a distant eight in the RealClearPolitics average, and while he does a little better in South Carolina, it’s still a long way back and will drop if he has two weak showings. Nationally, he’s also down to fourth in a no-man’s-land between the triple leaders Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio and a peloton of also-rans.

What’s peculiar is not just that he has dropped. It’s the circumstances. Typically, a candidate leaves the race because he is out of money or because it becomes clear that voters don’t like him. Yet neither of those apply to Carson. He had another excellent fundraising quarter to close 2015—more on that in a moment—and he’s viewed quite favorably. Nearly a third of Iowa voters viewed him favorably in that DMR poll, and his unfavorability is about even with Marco Rubio in the lowest slot. Nationally, Carson is also well-liked.

The surprise for Carson is perhaps not that he is fading as the race reaches the actual voting stage—it’s how it took so long. In a cycle when pundits’ many predictions have been proved wrong, it was actually fairly easy to guess that Carson, a first-time candidate with a great personal appeal but mixed-up policy positions, would end up near the back of the pack. The question is how he managed to rise and then fall back to earth.

Unless Carson manages to pull some tricks out of his sleeve in New Hampshire, will those small-dollar donors keep writing checks to fund the fundraising machine? Just because you like a guy doesn’t mean you’re willing to set your own money on fire for him.

A Rethink on India’s Gay-Sex Law

India’s Supreme Court is taking another look at a controversial decision that upheld Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a 155-year-old law that criminalizes gay sex.

At issue is the colonial-era law enacted in 1860 that imposes a 10-year prison sentence for “unnatural offenses … against the order of nature.” In 2013, the Supreme Court overturned a landmark ruling by the Delhi High Court in 2009 that decriminalized gay sex. The lower court had ruled that Section 377 violated the fundamental rights guaranteed by India's Constitution. But its decision was challenged by religious groups, and, subsequently, the Supreme Court ruled only Parliament can change the law.

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard a “curative petition” against its decision and said it would re-examine the order, calling it a “matter of constitutional importance.” No date has been given for when this will happen, but the issue will be heard by a five-judge panel headed by India’s chief justice.

Activists gathered outside the Supreme Court in New Delhi cheered upon hearing the news, and sang “We shall overcome.”

“It is definitely a move forward,” Anand Grover, a lawyer and longtime campaigner against the law, told Reuters.

The curative petition was the last legal stop available to gay-rights groups and their supporters. A legislative change is considered unlikely at this time—despite support for decriminalization from key members of the government and opposition—because the country, despite growing calls for gay sex to be decriminalized, remains deeply conservative.

India is one of more than 70 countries that has laws criminalizing gay sex. Although prosecutions under Section 377 are rare, it is often used by police to harass gays and lesbians.

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Race: A Cheat Sheet

Iowa has a reputation for confounding expectations, and 2016 has been no exception. On the Republican side, Donald Trump’s seemingly unstoppable momentum hit the wall of Ted Cruz and shuddered to a halt, dropping down to second. Marco Rubio proved skeptics wrong—or at least overzealous—in doubting that he was building momentum. The Florida senator delivered a strong third-place finish (he practically pretended it was first anyway), and nearly caught Trump. On the Democratic side, after months of trading leads, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders finally ended in an effective tie. (The Iowa Democratic Party said Clinton had finished with the thinnest of leads.)

Now the campaign heads to New Hampshire ahead of the February 9 primary there. There are four big questions to watch now.

First, is our long national Trump nightmare over? The Iowa caucuses had been presented by many journalists—and not least by Trump—as a chance for him to prove that he wasn’t just a master of publicity but also had the organizational oomph to turn out voters. If so, he failed the test. Turnout was high on Monday, but that wasn’t enough for Trump, who still slumped into second, with Rubio hot on his heels. The problem for Trump is clear enough: He will have to play catch-up to learn turnout skills, even as he has to explain why his failure to win in Iowa doesn’t disqualify a guy who’s candidacy is based on winning. But we’ve heard that Trump was finished before, and he has a huge lead in New Hampshire at the moment. It might be a tiny bit premature to breathe a sigh of relief.

Second, can Republicans stop Cruz? The Trump stumble is a pyrrhic victory for GOP leaders. They were petrified of Trump winning but fear and loathe Cruz, too. They both dislike him personally and think he’d be a bad general-election candidate. Cruz heads to New Hampshire in second place with momentum and a large war chest. Inextricable from this question is whether Rubio can finally muster the forces of the establishment behind him. Monday was a good start, but Rubio’s campaign has promised to finish second in the Granite State, and probably needs to do so to clear the field of other Cruz alternatives.

Third, what kind of momentum will Bernie Sanders get? Given that he was leading a few weeks ago, Sanders’s tie feels almost like a defeat. It shouldn’t. A year ago, Sanders seemed like a novelty candidate and Hillary Clinton seemed like a lock. Sanders fought her machine to a draw in the Hawkeye State and now goes to New Hampshire, where his lead already looked insurmountable even before the Iowa results. Sanders’s real challenge is down the road in Nevada, South Carolina, and the Super Tuesday states. (It’s important to remember that the candidates are fighting for delegates, too—CNN projects Clinton taking a slight lead among Iowa’s 44 delegates.)

Fourth, will anyone else drop out? On Monday night, two long-shot candidates left the race. Mike Huckabee, who won the Iowa caucus big in 2008, struggled to be heard among the many younger Republicans, and he dropped out after pulling less than 2 percent of caucuses. On the Democratic side, Martin O’Malley suspended his campaign as well, after registering less than 1 percent against Clinton and Sanders.

As for the rest of the field, the less said is probably the better. Only Ben Carson, Rand Paul, and Jeb Bush managed to crack 2 percent, and only Carson made it to double digits. New Hampshire is very different political terrain than Iowa, but those numbers are a good sign that the other campaigns may not be long for this world.

Yet with so many candidates still in the mix, it’s tough to keep track of it all. To help out with that, this cheat sheet on the state of the presidential field will be periodically updated throughout the campaign season. Here’s how things look right now.

* * *

The Republicans

Gage Skidmore

JIM GILMORE

Who is he?

Right? Gilmore was governor of Virginia from 1998 to 2002. Before that, he chaired the Republican National Committee for a year. In 2008, he ran for Senate in Virginia and lost to Mark Warner by 31 points.

Is he running?

Yes. He filed his papers on July 29, 2015.

Who wants him to run?

Who knows?

Can he win?

Nah.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

Holy Freudian slip, Batman!

Wikimedia

JOHN KASICH

Who is he?

The current Ohio governor ran once before, in 2000, after a stint as Republican budget guru in the House. Between then and his election in 2010, he worked at Lehman Brothers. Molly Ball wrote a definitive profile in April.

Is he running?

Yes. His announcement was July 21, 2015 at THE Ohio State University in Columbus.

Who wants him to run?

Kasich’s pitch: He’s got better fiscal-conservative bona fides than any other candidate in the race, he’s proven he can win blue-collar voters, and he’s won twice in a crucial swing state.

Can he win the nomination?

Kasich’s strategy has long been to place strongly in New Hampshire. He’s in the tightly packed peloton well behind yellow-jacket wearing Trump in the Granite State, fighting for votes with Chris Christie and Jeb Bush— two other moderate-ish, technocratic governors. Kasich’s has been a steady presence, but it’s tough to see how he could break out.

What else do we know?

John Kasich bought a Roots CD and hated it so much he threw it out of his car window. John Kasich hated the Coen brothers’ classic Fargo so much he tried to get his local Blockbuster to quit renting it. George Will laughed at him. John Kasich is the Bill Brasky of philistinism. John Kasich probably hated that skit, too.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

Nope.

David Shankbone

CHRIS CHRISTIE

Who is he?

What’s it to you, buddy? The combative New Jerseyan is in his second term as governor and previously served as a U.S. attorney.

Is he running?

Christie kicked off his campaign June 30, 2015 at Livingston High School, his alma mater.

Who wants him to run?

Moderate and establishment Republicans who don’t like Bush or Kasich; big businessmen, led by Home Depot founder Ken Langone.

Can he win the nomination?

Doubtful. The tide of opinion had turned against Christie even before the "Bridgegate" indictments. Citing his horrific favorability numbers, FiveThirtyEight bluntly puns that “Christie's access lanes to the GOP nomination are closed.” But since snagging the endorsement of the New Hampshire Union Leader, he’s seen a small boomlet.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

We would have gone with the GIF, but sure.

Gage Skidmore

DONALD TRUMP

Who is he?

America’s sweetheart.

Is he running?

And how.

Who wants him to run?

A shocking portion of the Republican primary electorate; Democrats; white supremacists. The rest of the Republican field, along with its intellectual luminaries, however, are horrified.

Can he win the nomination?

Right up until the Iowa caucus, the political class was just starting to come around to the idea that he could. But after he slipped to a disappointing second in the Hawkeye, things could get ugly in New Hampshire and beyond.

What else do we know?

He cheats at golf, probably.

Gage Skidmore

JEB BUSH

Who is he?

The brother and son of presidents, he served two terms as governor of Florida, from 1999 to 2007.

Is he running?

Yes, as of June 15, 2015.

Who wants him to run?

Establishment Republicans; George W. Bush; major Wall Street donors.

Can he win the nomination?

It sure doesn’t look like it. Bush’s campaign is a case study in how money isn’t everything. Despite the $100 million super PAC backing him, Bush has been a feckless, adrift candidate. Every now and then a poll will show him rising to, oh, fourth or something and there will be rumors of a Bush comeback. But one look at his unfavorables shows why he’s pretty much been written off.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

Yes—y en español también.

Gage Skidmore

RICK SANTORUM

Who is he?

Santorum represented Pennsylvania in the Senate from 1995 until his defeat in 2006. He was the runner-up for the GOP nomination in 2012.

Is he running?

Yes, with a formal announcement on May 27, 2015.

Who wants him to run?

Social conservatives. The former Pennsylvania senator didn't have an obvious constituency in 2012, yet he still went a long way, and Foster Friess, who bankrolled much of Santorum's campaign then, is ready for another round.

Can he win the nomination?

Nah. As much as Santorum feels he deserves more respect for his 2012 showing, neither voters nor the press seem inclined to give it to him, and he remains trapped in the basement.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

No.

Gage Skidmore

BEN CARSON

Who is he?

A celebrated former head of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins, Carson became a conservative folk hero after a broadside against Obamacare at the 2013 National Prayer Breakfast.

Is he running?

Yes. He announced May 4, 2015.

Who wants him to run?

Grassroots conservatives. Carson has an incredibly appealing personal story—a voyage from poverty to pathbreaking neurosurgery—and none of the taint of politics.

Can he win the nomination?

Hey, it was a fun run while it lasted: Would Dr. Ben be the man to take our Trump? It wasn’t to be. Gaffe-prone, ill-informed, and incapable of managing a fractious staff, Carson has fallen from a lofty second to a distant fourth nationally. If it’s any consolation, history weighed heavily against Carson’s chances all along: Not since Dwight Eisenhower has either party nominated anyone without prior elected experience for the presidency.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

No.

Gage Skidmore

CARLY FIORINA

Who is she?

Fiorina rose through the ranks to become CEO of Hewlett-Packard from 1999 to 2005, before being ousted in an acrimonious struggle. She advised John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign and unsuccessfully challenged Senator Barbara Boxer of California in 2010.

Is she running?

Yes, as of a May 4, 2015, announcement.

Who wants her to run?

It isn’t clear exactly what Fiorina’s constituency is, but she’s a business-friendly candidate with a talent for a sharp turn of phrase or jab.

Can she win the nomination?

Fiorina went from also-ran to huge story on the strength of her first two debate performances. Then her momentum stalled, and she now leads only Santorum (and Gilmore, we guess) nationally.

What else do we know?

Fiorina’s unsuccessful 2010 Senate race against Barbara Boxer produced two of the most entertaining and wacky political ads ever, "Demon Sheep" and the nearly eight-minute epic commonly known as "The Boxer Blimp."

Does her website have a good 404 page?

No.

Wikimedia

MARCO RUBIO

Who is he?

A second-generation Cuban-American and former speaker of the Florida House, Rubio was catapulted to national fame in the 2010 Senate election, after he unexpectedly upset Governor Charlie Crist to win the GOP nomination.

Is he running?

Yes—he announced on April 13, 2015.

Who wants him to run?

Rubio enjoys establishment support, and has sought to position himself as the candidate of an interventionist foreign policy.

Could he win the nomination?

Rubio’s campaign is banking on breaking out at exactly the right time. First, that seemed like it was going to be in November, when breakout debate performances pushed him into the spotlight. Then he flatlined. Then his aides started talking about a “3-2-1” strategy, for where his targeted finish in Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina, respectively. Rubio nailed the 3 in Iowa and gave a pseudo-victory speech. His task now is to consolidate the anti-Cruz, anti-Trump coalition.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

It’s decent.

Wikimedia

RAND PAUL

Who is he?

An ophthalmologist and son of libertarian icon Ron Paul, he rode the 2010 Republican wave to the Senate, representing Kentucky.

Is he running?

Yes, as of April 7, 2015.

Who wants him to run?

Ron Paul fans; Tea Partiers; libertarians; civil libertarians; non-interventionist Republicans.

Can he win the nomination?

Once tabbed by Time as the most interesting man in politics, he has failed to elicit much interest from voters. The deathwatch stories in December (and September, and October) were clearly premature, but that doesn’t mean they were wrong.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

No.

Wikimedia

TED CRUZ

Who is he?

Cruz served as deputy assistant attorney general in the George W. Bush administration and was appointed Texas solicitor general in 2003. In 2012, he ran an insurgent campaign to beat a heavily favored establishment Republican for Senate.

Is he running?

Yes. He launched his campaign March 23, 2015 at Liberty University in Virginia.

Who wants him to run?

Hardcore conservatives; Tea Partiers who worry that Rand Paul is too dovish on foreign policy; social conservatives.

Can he win the nomination?

It looks more likely than ever, especially after his commanding Iowa victory over Trump. Once dismissed as too conservative and too hated by even fellow Republicans, Cruz’s stock has risen over the course of the fall. But Cruz still contends with the fact that much of his party absolutely despises him, so much so that they're willing to back Trump. .

Does his website have a good 404 page?

No.

* * *

The Democrats

Wikimedia

HILLARY CLINTON

Who is she?

As if we have to tell you, but: She’s a trained attorney; former secretary of State in the Obama administration; former senator from New York; and former first lady.

Is she running?

Yes.

Who wants her to run?

Most of the Democratic Party.

Can she win the nomination?

Yep. But she’ll have to fight for it.

What else do we know?

The real puzzler, after so many years with Clinton on the national scene, is what we don't know. Here are 10 central questions to ask about the Hillary Clinton campaign.

Does her website have a good 404 page?

If you’re tolerant of bad puns and ’90s ’80s outfits, the answer is yes.

Wikimedia

BERNIE SANDERS

Who is he?

A self-professed socialist, Sanders represented Vermont in the U.S. House from 1991 to 2007, when he won a seat in the Senate.

Is he running?

Yes. He announced April 30, 2015.

Who wants him to run?

Far-left Democrats; Brooklyn-accent aficionados; progressives who worry that a second Clinton administration would be far too friendly to the wealthy.

Can he win the nomination?

When Sanders launched his campaign, this question seemed beside the point. That’s no longer true: Sanders is running neck and neck or even ahead of Clinton in key early primary states and regularly drawing larger crowds than her. He trails by double digits nationally and seems likely to struggle in the South, but his strong showing in Iowa will give him a boost.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

Yes, and it is quintessentially Sanders.

* * *

Third Party and Independent

Wikimedia

MICHAEL BLOOMBERG

Who is he?

The billionaire finance-and-technology entrepreneur was benevolent dictator mayor of New York from 2002 to 2013.

Is he running?

No, but there have been trial balloons launched in the press. He will reportedly decide by March.

Who wants him to run?

If the past is any indication, it’s mostly Bloomberg aides. Supposedly, Bloomberg is terrified of a Trump vs. Sanders race and would run if that was the matchup. Is there a base for Bloomberg, a fiscally conservative but socially liberal abrasive New Yorker? Seems unlikely.

What are his prospects?

Bloomberg himself has repeatedly belittled his own electability, either as an individual or, in the abstract, as a third-party candidate. And he’s probably right. It’s hard to imagine who would vote for him, especially if Clinton wins the Democratic nod: He’s slightly to the right of her, but Republicans hate him, and he makes her seem like Miss Congeniality.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

Please. This is a guy who doesn’t even think websites are necessary.

Wikimedia

JIM WEBB

Who is he?

Webb is a Vietnam War hero, author, and former secretary of the Navy. He served as a senator from Virginia from 2007 to 2013.

Is he running?

Not at the moment. Webb launched a Democratic bid July 2, 2015 but dropped it October 20, 2015. He has since made noises about mounting an independent campaign, including hiring a fundraiser.

Who wants him to run?

As a Democrat, doves; the Anybody-But-Hillary camp; and my colleague James Fallows. As an independent? Maybe some of the same socially conservative, economically populist Democrats who backed him before. But he barely registered in the race the first time around.

What are his prospects?

Bad. Every independent candidate is at best a very long shot, and Webb’s weaknesses—dislike for campaigning, weak fundraising, heterodox views—were on clear display during his Democratic bid.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

No.

Wikimedia

JILL STEIN

Who is she?

A Massachusetts resident and physician, she is a candidate of nearly Stassen-like frequency, having run for president in 2012 and a slew of other offices before that.

Is she running?

Yes. Stein announced in June 2015 that she would again seek the nomination of the Green Party, which she won in 2012.

Who wants her to run?

Stein seems to have strong support with the Green Party. She managed to collect nearly 500,000 votes in 2012—the party’s strongest showing since Ralph Nader’s disastrous 2000 run, but well short of the 2.9 million votes he got.

What are her prospects?

She seems well placed to win the nomination. Her rivals include Darryl Cherney, a musician the FBI once accused of bombing himself, and Bill Kreml, a Taoist professor emeritus of political science. It’s too soon to speculate how she might fare in the general election compared to 2012.

Does her website have a good 404 page?

Possibly not original, but kind of soothing and on-message.

Wikimedia

GARY JOHNSON

Who is he?

Oh come on, you remember Gary! He ran for the GOP nomination in 2012 and then got the Libertarian Party nod after that didn’t work out. He was previously two-term governor of New Mexico. He now runs a company that sells THC lozenges.

Is he running?

Sure is. He announced his attempt for an encore performance with the Libertarian Party on January 6.

Who wants him to run?

As his company’s site notes, “Now that he's associated with what is being hailed the best legal cannabis product on the market, Gary may be drafted for President of the United States by a grateful nation one day.” Johnson’s also an unusually talented and successful politician to vie for the Libertarian line. The 1.3 million votes he collected in 2012 were the party’s all-time high … so to speak.

What are his prospects?

He’s running against the outlandish oddball former tech titan John McAfee in the party, so that looks good. But of his general-election chances, he told my colleague Nora Kelly, “I have no delusions of grandeur here. I know what happened last time.”

Does his website have a good 404 page?

No.

* * *

Out of the Running

Republicans

Gage Skidmore

[image error]

MIKE HUCKABEE

Who is he?

An ordained preacher, former governor of Arkansas, and Fox News host, he ran a strong campaign in 2008, finishing third, but sat out 2012.

Is he running?

No. Huckabee dropped out on February 1 after pulling less than 2 percent of the vote in the Iowa caucuses.

Who wanted him to run?

Social conservatives; evangelical Christians.

Could he have won the nomination?

No. Evangelicals, his old base, flocked to Ted Cruz instead. Huckabee’s answer was to play as a populist, but that it never really took.

Did his website have a good 404 page?

It’s pretty good.

Wikimedia

LINDSEY GRAHAM

Who is he?

A senator from South Carolina, he’s John McCain’s closest ally in the small caucus of Republicans who are moderate on many issues but very hawkish on foreign policy.

Is he running?

No sir. Graham kicked off the campaign June 1, 2015 but suspended it on December 21.

Who wanted him to run?

John McCain, naturally. Senator Kelly Ayotte, possibly. Joe Lieberman, maybe?

Could he have won the nomination?

No. But he had some fun in losing it.

What else do we know?

Graham promised to have a rotating first lady if he wins. We were rooting for Lana del Rey.

Gage Skidmore

BOBBY JINDAL

Who is he?

A Rhodes Scholar, he’s the outgoing governor of Louisiana. He previously served in the U.S. House.

Is he running?

No. He kicked off his campaign on June 24, 2015 but suspended it on November 17.

Who wanted him to run?

It’s was hard to say. Jindal assiduously courted conservative Christians, both with a powerful conversion story (he was raised Hindu but converted to Catholicism in high school) and policies (after other governors reversed course, he charged forward with a religious-freedom law). But he still trailed other social conservatives like Ted Cruz and Mike Huckabee.

Could he have won the nomination?

No. Jindal never gained traction at the national level, faced an overcrowded field of social conservatives, and his stewardship of Louisiana came in for harsh criticism even from staunch fiscal conservatives.

What else do we know?

In 1994, he wrote an article called “Physical Dimensions of Spiritual Warfare,” in which he described a friend’s apparent exorcism.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

Meh. Good joke, but past its expiration date.

Gage Skidmore

RICK PERRY

Who is he?

George W. Bush’s successor as governor of Texas, he entered the 2012 race with high expectations, but sputtered out quickly. He left office in 2014 as the Lone Star State’s longest-serving governor.

Is he running?Yes. He announced on June 4. Perry dropped out of the race on September 11, 2015.

Who wanted him to run?

Bueller?

Could he have won the nomination?

No. Perry promoters insisted that Rick 2016 was a polished, smart campaigner, totally different from the meandering, spacey Perry of 2012. It didn’t seemed to matter in this field. Perry had to quit paying his staff in South Carolina and New Hampshire, and was down to a single staffer in Iowa when he dropped out.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

That depends. Is this an “oops” joke? If so, yes.

Gage Skidmore

SARAH PALIN

Who is she?

If you have to ask now, you must not have been around in 2008. That’s when John McCain selected the then-unknown Alaska governor as his running mate. After the ticket lost, she resigned her term early and became a television personality.

Is she running?

No, despite a bizarre speech in January 2015 that made a compelling case both ways.

Who wants her to run?

Palin still has diehard grassroots fans, but there are fewer than ever.

Can she win the nomination?

No.

When will she announce?

It doesn't matter.

Gage Skidmore

MITT ROMNEY

Who is he?

The Republican nominee in 2012 was also governor of Massachusetts and a successful businessman.

Is he running?

Probably not, but who knows! He announced in late January 2015 that he would step aside, but now New York claims that the Trump boom has him reconsidering.

Who wanted him to run?

Former staffers; prominent Mormons; Hillary Clinton's team. Romney polled well, but it's hard to tell what his base would have been. Republican voters weren't exactly ecstatic about him in 2012, and that was before he ran a listless, unsuccessful campaign. Party leaders and past donors were skeptical at best of a third try.

Could he have won the nomination?

He proved the answer was yes, but it didn't seem likely to happen again.

Gage Skidmore

JOHN BOLTON

Who is he?

A strident critic of the UN and leading hawk, he was George W. Bush’s ambassador to the UN for 17 months.

Is he running?

Nope. After announcing his announcement, in the style of the big-time candidates, he posted on Facebook that he wasn’t running.

Who wanted him to run?

Even among super-hawks, he didn’t seem to be a popular pick, likely because he had no political experience.

Could he have won the nomination?

They say anything is possible in politics, but this would test the rule. A likelier outcome could be a plum foreign-policy role in a hawkish GOP presidency.

Gage Skidmore

SCOTT WALKER

Who is he?

Elected governor of Wisconsin in 2010, Walker earned conservative love and liberal hate for his anti-union policies. In 2013, he defeated a recall effort, and he won reelection the following year.

Is he running?

No. Walker dropped out of the race on September 21, 2015.

Who wanted him to run?

Walker was a favorite of conservatives who detest the labor movement because of his union-busting in Wisconsin. He attracted interest from the Koch brothers, and some establishment Republicans saw him as the perfect marriage of executive know-how, business-friendly credentials, and social conservatism without culture-warrior baggage.

Could he have won the nomination?

For months, Walker was considered—along with Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio—a top-tier contender for the nomination. Hurricane Trump hurt all three, but none more than Walker. After largely fading from view during the second presidential debate, he polled below 1 percent in a national CNN poll. Perhaps a radically different campaign would have produced a different result, but Walker didn’t seem ready for national primetime.

Did his website have a good 404 page?

Aye, matey.

Michael Vadon

GEORGE PATAKI

Who is he?

Pataki ousted incumbent Mario Cuomo in 1994 and served three terms as governor of New York.

Is he running?

No. He announced his entry on May 28, 2015, but dropped out on December 29—using free time he’d won on TV in compensation for Donald Trump’s Saturday Night Live appearance.

Who wanted him to run?

Apparently no one: His RealClearPolitics average by the time he dropped out was a neat 0.0. Establishment Northeastern Republicans once held significant sway over the party, but those days have long since passed.

Could have have won the nomination?

Nope.

Did his website have a good 404 page?

No.

* * *

Democrats

Wikimedia

[image error]

MARTIN O'MALLEY

Who is he?

He’s a former governor of Maryland and mayor of Baltimore.

Is he running?

No. O’Malley announced he was suspending his campaign after getting less than 1 percent in the February 1 Iowa caucus.

Who wanted him to run?

Not clear. He has some of the leftism of Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, but without the same grassroots excitement.

Could he have won the nomination?

No. Why O’Malley—who says all the right progressive things—couldn’t gain any momentum among progressives who seem eager for Sanders, for Warren, really for anyone but Clinton, is a fascinating conundrum.

What else do we know?

Have you heard that he plays in a Celtic rock band? You have? Oh.

Did his website have a good 404 page?

No.

Wikimedia

LAWRENCE LESSIG

Who is he?

Lessig is a professor at Harvard Law School, political activist, and occasional Atlantic contributor.

Is he running?

No. Having announced a run in early September, he dropped out on November 2, 2015.

Who wanted him to run?

Lessig’s campaign was designed to cater almost exclusively to the many Americans who are upset about the influence of money in politics. He pitched himself as a “referendum president” who would pass his proposed Citizens Equality Act of 2017, which would enact universal voting registration, campaign-finance limits, and anti-gerrymandering provisions.

Could he have won the nomination?

No. In dropping out, he cited his inability to break into the Democratic debates, but given his lack of electoral experience, his idiosyncratic platform, and the track record of his Mayday PAC in the 2014 election, he never really had a shot.

What else do we know?

In a season 6 episode of The West Wing, a fictional Lessig (played by Christopher Lloyd) worked with the White House to write a new constitution for Belarus.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

“Sorry, we’re too busy fixing democracy to design a clever 404 page!” You have time now!

Steven Senne / AP

LINCOLN CHAFEE

Who is he?

The son of beloved Rhode Island politician John Chafee, Linc took his late father’s seat in the U.S. Senate, serving as a Republican. He was governor, first as an independent and then as a Democrat.

Is he running?

No. Chafee announced his run on June 3, 2015, but ended it October 23.

Who wanted him to run?

You can meet all 10 of them in this great NPR piece.

Could he have won the nomination?

No. Chafee’s showing in the first debate was so bad that even Wolf Blitzer begged him to get out for his own reputation’s sake.

Does his website have a good 404 page?

No.

Wikimedia

JOE BIDEN

Who is he?

Biden is vice president, and the foremost American advocate for aviator sunglasses and passenger rail.

Is he running?

No. After lengthy deliberation, Biden ruled out a run on October 21, 2015.

Who wanted him to run?

The original driving force for the run seems to have been the late Beau Biden, along with his brother Hunter. An outside group called Draft Biden (slogan: “I’m Ridin’ With Biden”) tried to coax him in.

Could he have won the nomination?

It’s highly doubtful. Even when Hillary Clinton was at her weakest, she had huge organizational advantages. And past presidential campaign showed that Biden, while compelling, could be an undisciplined, self-defeating candidate.

Wikimedia

ELIZABETH WARREN

Who is she?

Warren has taken an improbable path from Oklahoma, to Harvard Law School, to progressive heartthrob, to Massachusetts senator.

Is she running?

Are you still scrolling down here to check? Not a chance, amigo.

Who wants her to run?

Progressive Democrats; economic populists, disaffected Obamans, disaffected Bushites.

Can she win the nomination?

No, because she’s not running.

February 1, 2016

'No, It's Iowa': When TV Dramas Go to Caucus

Iowa is no longer, electorally speaking, a winner-take all state. As of 2012, for Republicans and Democrats alike, the state has relied on a system of proportional allocation: Win 29 percent of the state’s electorate, get 29 of the state’s electoral vote. As a matter of lore, though—which has a sneaky way, via media-aided alchemy, of turning itself into political reality—the Iowa stakes are high. It was his win in Iowa in 2008 that helped build momentum for the candidacy of Barack Obama. It was his win in Iowa in 2000 that did the same for George W. Bush. The caucuses enforce a mingling of expectations and reality, of gauzy punditry and grassroots politics; their results are at once scientific and ineffable. Through these great pageants of American democracy, political fictions become political realities. Push, as it were, meets Shove.

Related Story

It’s no surprise, given all that, that Hollywood—which loves nothing more than juicy dramas that are at once high-stakes and deeply human—would do its part to celebrate the events that Iowans euphemize as “gatherings of neighbors.” Television, in particular has tended to treat the caucuses not (just) as defining moments for its fictional politicos, but also as defining moments for its characters more broadly. TV shows, essentially, have echoed what political pundits have taken for granted: that political dramas are human dramas. That campaigns are battles, fundamentally, of character. That political campaigns are best understood not in terms of dueling policies, but in terms of dueling people.

Take, most recently, The Good Wife. One of the few awkward elements of the show—an otherwise excellent drama enjoying an otherwise excellent seventh season on CBS—has been this: its tendency to relegate to a B-plot the fact that its protagonist’s husband is running for president. (Of the United States.) Audiences have gotten reminders of Peter Florrick’s presidential bid every once in awhile—an extremely reluctant Alicia Florrick was once forced to appear, with her mother, on the local talk show Mama’s Homespun Cooking—but for the most part, the show has insisted that its characters live in a world in which campaigning to be First Lady is a forgettable side gig.

TV shows suggest what punditry has taken for granted: that political dramas are human dramas, and that campaigns are battles of character.

For Iowa, though, The Good Wife shed its illusions. The show dedicated a full episode to Peter’s attempt to come in second in the caucuses—an attempt that found the entire Florrick family, enthusiastically (Peter, Zack, Grace) and less so (Alicia), traveling together on a bus through the state’s counties and precincts. (On advice of the Florrick campaign manager, Ruth Eastman, the family attempts a “full Grassley,” or a visit to every county in Iowa.) And yet the real contest of the episode is not the campaign (which rather awkwardly makes mention of “Hillary” to put things into a 2016 IRL context). It is instead the long-simmering uncertainties between Alicia and Peter about the future of their marriage. Alicia spends her time on the campaign bus immersed in her memories of the man she’d loved before marrying Peter. She spends her time in the episode doing the duties of a “full campaign wife,” but dreaming, all the while, of what might have happened had she married the other guy.

The caucuses, in the episode, come and go—and yet their political outcomes (and here is the show reverting to its traditional posture) are secondary. The real stakes here are emotional. The real caucus here has an n of 1: The real decision, the episode suggests, is the one Alicia is making about Peter and her relationship to him. As per Iowa’s wont, Push is coming to Shove; it’s just that the collisions between expectation and reality aren’t, primarily, about politics.

House of Cards’s Iowa episode—the series’s third season finale—offers a similar emotion-over-election theme. These caucuses find Frank Underwood engaged in a neck-and-neck fight against his Democratic challenger, Heather Dunbar. And while it’s an open question throughout the episoe, whether Frank—by now the sitting president—will be able to eke out a victory in the caucuses, the real drama, as in The Good Wife, concerns the fate of the protagonists’ marriage.

The episode opens with Claire informing her husband that “we have been lying to each other”; it closes with the question of whether Claire will show up to support him as he delivers his speech—regardless of whether that speech be a matter of victory or concession. Quickly, though, things escalate—so that the real questions become existential: Can the Underwood marriage survive Frank’s campaign for president? Are Claire and Frank a true partnership? Were they ever a partnership at all? “We used to make each other stronger, or at least I thought so,” Claire tells her husband. “But that was a lie. We were making you stronger.”

Iowa, making-or-break-ing once again.

Iowa has done, on TV, just what it claims to do in IRL politics: It puts people on equal footing. It flattens them, in the best sense of the word.

Similar themes are on offer in other recent political shows. In Scandal, Olivia Pope’s original political sin—the thing that taints her White Hat—is revealed to be her participation in the election-rigging scheme that started with Fitzgerald Grant’s defeat in the Iowa caucuses. And in The West Wing, the Iowa episode “King Corn,” which superficially revolves around the Democratic candidates’ internal debates about whether to take “the ethanol pledge,” more directly concerns the growing sexual tension between Josh Lyman and Donna Moss. The episode finds the two—the Sam and Diane of The West Wing, coming ever closer to answering the will-they-or-won’t-they question in the affirmative—realizing that their hotel rooms in Cedar Rapids are directly across the hall from each other. It emphasizes their parallel mornings. It emphasizes their parallel days. It ends with Josh, aaaalmost deciding to knock on Donna’s door when the day is done, and then deciding against it.

And yet: The episode does the work that will be necessary for Donna and Josh to become a couple: It insists on their equality. All those parallels—rooms and days—suggest how far Donna has come from being, simply, Josh’s assistant. They suggest that Donna and Josh becoming a couple would not be a boss-and-secretary affair, but rather a marriage—or, you know, a committed relationship—of equals.

It’s just another instance of Iowa doing, on television, just what it claims to do in IRL politics: putting people on equal footing. Flattening them, in the best sense. Allowing them to compete, and converse, and consider their options. (“Is this heaven? No, it’s Iowa.”) The stakes, on TV—just as they are in politics writ large—may not be winner-take-all. They’re nuanced, and messy. But the stakes, for all that, are also high. Iowa, just as it will in IRL politics, helps to define the path its characters will take the rest of the way.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower