Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 238

February 4, 2016

Obama's $10 Oil-Tax Pipe Dream

If Congress won’t raise taxes on gasoline, will it slap a fee on oil?

That’s what President Obama will ask of lawmakers when he releases his final budget proposal next week, calling for a $10 tax on every barrel of oil to pay for a long-term infusion of spending on infrastructure. Coming from a lame-duck Democratic president, the proposal is, plainly, a non-starter in the Republican-led Congress. But the idea is sure to jumpstart the debate over energy and infrastructure in this year’s presidential campaign, and it signals a renewed effort to find a fresh way to pay for upgrades to the nation’s transportation system that both parties agree are sorely needed.

“Our transportation system used to be a source of competitive advantage for our global economy, but today we’re at risk of it becoming an Achilles heel,” Jeffrey Zients, director of the White House National Economic Council, told reporters on a conference call.

While both Democratic and Republican-led states have been raising the gas tax in recent years to pay for upgrades, Congress hasn’t touched the 18.4 cent-per-gallon gas tax in more than two decades, even as prices have dropped steadily to below $2 a gallon at the pump. On the surface, taxing a barrel of oil rather than gasoline should be an easier political sell. The levy would still be passed onto consumers in price increases, but it’s a less direct hit and would be broader than targeting only the heaviest users of streets and highways. Oil companies have always been ripe targets for Democrats, who have proposed windfall-profits taxes in the past.

Yet Obama’s $10-a-barrel tax comes at a more precarious moment for the oil industry, which has been rocked by plummeting prices in recent months. Companies that complained whenever politicians would propose a new tax can now do so a bit more credibly. “The industry is in largest crisis in over 25 years,” the Independent Petroleum Association of America tweeted Thursday afternoon. “This is an energy consumer tax disguised as an oil company fee.”

Zients acknowledged that oil companies “will likely pass on some of these costs,” but he said the burden of a per-barrel tax would be shared much more broadly than increasing the gas tax. While imported oil would be subject to the fee, U.S. companies exporting oil would not. “Our domestic producers will continue to operate on a level playing field,” he said.

Congress passed its first long-term infrastructure bill in more than a decade late last year. Obama signed it into law but said at the time that its $305 billion in spending was only a down payment on what was needed. Administration officials pitched his new plan as one that would simultaneously boost overall surface transportation spending by 50 percent as well as continue to fight climate change by shifting away from oil and toward more efficient transit options like high-speed rail.

The big short-term question is not how Congress will react, nor even the Republicans running to succeed Obama. They’ll almost certainly reject the president’s plan. But what about Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, both of whom have promised expansive infrastructure investments? Will they embrace a tax on oil companies, or are they wary of alienating the consumers who might ultimately have to pay it? “For too long, there’s been strong bipartisan agreement that we need much more infrastructure, but that hasn’t been accompanied by the political will to fund it,” Zients said. “People call for more transportation spending, but they never talk about how they’ll pay for it.”

Obama is starting that conversation, but he won’t be the one to finish it.

Hannibal Buress: Enough With the Cosby Business

Hannibal Buress was already a well-known standup with three great albums to his name and a burgeoning acting career when he became known as the comic who spurred the downfall of Bill Cosby. It’s a strange note to have on any resumé, and from the looks of Buress’s latest Netflix special Comedy Camisado, it’s one he’s eager to live down. Filmed in a smallish Minneapolis theater, the hour-long set sees Buress largely discussing his life on the road, but he also touches on the newspaper headlines about his Philadelphia standup bit that referenced the long history of rape accusations against Cosby.

Related Story

Key & Peele and Hannibal Buress Highlight Comedy Central's Evolution

“I was just doing a joke at a show! I didn’t like the media putting me at the forefront of it. They were sly, dissing me in the news: ‘Unknown Comedian Hannibal Buress...’” he jokes. “‘Homeless comedian Hannibal Buress took the stage in Philly, covered in rags…’” Comedy Camisado is being hyped as Buress closing the book on his reputation as a Cosby-slayer, but it’s more a work of bemused reflection on that time in his life. Buress has the confidence of a comedian who was already a rising superstar before a slew of newspaper headlines began wondering who he was, and his latest special coasts on that trajectory rather than trying to move in a new direction.

Buress, to his credit, has always been very self-aware about the Cosby business, recognizing the irony that it took a male comedian talking about the accusations against him to ignite the issue in the media again. Though his comedy often slyly tackles issues of race and institutional discrimination (the shaggy dog story “Apple Juice,” from his second album Animal Furnace, is a required listen), Buress isn’t a polemical standup. In a recent appearance on The Daily Show With Trevor Noah, Buress recalled a disastrous appearance in South Africa, where some attending journalists knew him only as an advocate and were surprised when he started telling jokes.

With Comedy Camisado, Buress is pumping the brakes and getting back to what he does best—telling strange, windy stories of surreal encounters in airports or bizarre chats with strangers that somehow manage to elicit belly laughs even if they don’t lead toward a conventional punchline. Buress has always had one of the most captivating delivery styles in the comedy business: quiet, conversational, then suddenly building to amused rage. It’s what helped him stick out as the supporting character Lincoln on Broad City, it’s what’s helped him carve out a burgeoning film career in comedies like Neighbors and Daddy’s Home, and it’s what keeps Comedy Camisado afloat even as it struggles to match the strength of his previous hours.

Buress is still a pleasure to watch, but he’s run into a problem that besieges a lot of observational comedians as they get more and more famous: His material is mostly about life as a comedian, doing tours, and grappling with increasing recognition as occasional TV appearances blossom into full-fledged, on-screen careers. One of Comedy Camisado’s longest stories is about a hotel clerk denying Buress access to his room because he forgot his ID, even as he protests that she can just look him up online. It’s funny (and he pulls it off by never quite sounding outraged), but the bit skirts close to Buress asking “Don’t you know who I am?”

On his first album, My Name Is Hannibal, Buress tended more toward the absurd, whether he was noting the pointless existence of the “Fire SUV” that travels along with the fire trucks, or spending minutes musing on the flavorful potential of pickle juice. On his second album Animal Furnace, Buress was more focused on love and intimacy, bluntly tapping into real emotional turbulence alongside his more whimsical digressions. But on Comedy Camisado, things sound like they’re generally going well for Buress. He has a career, he’s in a solid relationship, and his big joke about Cosby amounts to, “Hey, I was already pretty famous when these papers started writing about me.” His confidence even comes through in the small venue he chose to film the special in: Buress has nothing left to prove, nor should he.

If anything, Comedy Camisado (the name refers to a military term for a sneak attack at night, but has no bearing on the jokes within) feels like a holding pattern for Buress as he decides what to do next. It’s not dissimilar from Aziz Ansari’s Madison Square Garden album, or Louis C.K.’s Live at the Beacon Theater, all of which came at high points for their respective stars, and were followed by stranger, more introspective TV works. Buress’s first solo television show, Why? With Hannibal Buress on Comedy Central, failed to catch fire, but he’s already started talking about branching out and doing something scripted for Netflix. He’ll never stop being funny onstage, but the lesson of Comedy Camisado was that there’s perhaps no new ground left for Buress to break on that front. A change could do him good.

When Did Rick Snyder Learn About Legionnaire's in Flint?

It’s getting increasingly harder for Michigan officials to claim ignorance about the poisoning of the city of Flint.

According to newly revealed emails, an aide to Governor Rick Snyder learned nine months ago of an outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease tied to Flint’s water supply. Ten people died from the bacterial infection, which Snyder made public in mid-January. At the time, he said he’d only become aware of the outbreak a couple days earlier. The emails don’t prove that’s false, but they shows that Snyder probably should have known about it.

Related Story

What Did the Governor Know About Flint's Water, and When Did He Know It?

“The increase of the illnesses closely corresponds with the timeframe of the switch to the Flint River water. The majority of the cases reside or have an association with the city,” a Genesee County health official wrote to the state Department of Environmental Quality and to Flint’s state-appointed emergency manager on March 10. “This situation has been explicitly explained to MDEQ and many of the city’s officials … I want to make sure in writing that there are no misunderstandings regarding this significant and urgent public health issue.”

Three days later, DEQ’s spokesman, Brad Wurfel, wrote to DEQ Director Dan Wyant as well as to a Snyder aide, noting the Genesee county official had “made the leap formally in his e-mail that the uptick in cases is directly attributable to the river as a drinking water source,” which Wurfel called “beyond irresponsible.”

That fits with a pattern of state officials insisting that what was happening in Flint was either not a problem or at least not their problem. When high levels of chlorine in the water produced a high concentration of carcinogens called TTHMs, a state official wrote, “It’s not ‘nothing.’ But it’s not like it’s an eminent [sic] threat to public health.” In another email, Snyder’s then-chief of staff acknowledged the problems in Flint, but tried to present the problem as a matter for local officials.

The main story of the Flint poisoning is not Legionnaire’s or TTHM but lead poisoning, which can create long-term developmental disabilities in children and other health problems. The problems began when Flint began drawing its water from the Flint River, rather than from the Detroit Water Services District; the river water, which has a higher concentration of chlorides, corroded Flint’s pipes, so lead remains a problem even now, after the city returned to Detroit water.

Throughout the crisis, Snyder has protested his own ignorance about the problems. Several state officials, including Wyant and Wurfel, were forced to resign over the scandal. But a steady stream of messages—including a large cache released by Snyder’s office—have shown that whatever Snyder personally knew, people in his office knew about the crisis in Flint months before it became a national story and brought about state and federal emergency declarations. While citizens of Flint begged for help, the problem wasn’t that no one was listening. It’s that the people who heard didn’t have the political will to do anything about it.

For Snyder, the drip-drip forces him to walk in the paths of executives before him, from Chris Christie to Rahm Emanuel, who have argued that though their aides were well-versed on topics, they were not.

Clinton and Sanders Go One-on-One in New Hampshire

Sorry, Marty. It’s down to Hillary and Bernie now.

With Martin O’Malley out of the presidential race, the two remaining Democratic candidates will go head-to-head for the first time on Thursday night, launching a two-person contest likely to stretch to Super Tuesday and beyond. The 9 p.m. debate on MSNBC was only confirmed on Wednesday, after Clinton, Sanders, and the Democratic National Committee agreed to add four additional match-ups to the two remaining contests that were previously scheduled.

Presidential candidate debates in recent elections have often come with a theme—the economy, for example, or national security and foreign policy. Thursday’s event is ostensibly open-ended, but it will probably focus on one over-arching question: What does it mean to be a progressive?

That’s been the topic of discussion in the three days since Clinton defeated Sanders by the thinnest margin in the history of the Iowa Democratic caucuses. Defending his comfortable lead in the New Hampshire polls, Sanders has begun to question Clinton’s progressive credentials. The dispute began on Tuesday, when a reporter asked Sanders if he considered his rival a progressive. “Some days, yes,” he replied. “Except when she announces that she is a proud moderate, and then I guess she is not a progressive.”

Ouch.

The Clinton camp didn’t take kindly to that. “You’re progressive enough, Hillary,” tweeted Jennifer Palmieri, the campaign’s communications director. It was a none-too-subtle reference to Barack Obama’s infamous backhanded compliment from 2008, when he told Clinton during a New Hampshire debate, “You’re likable enough.”

Sanders ran with the contrast, however, embracing the argument that his supporters have been making for months: He’s the authentic liberal, and Clinton is a progressive when it’s convenient. In a tweetstorm on Wednesday, Sanders unleashed a litany of examples of where he believed the former secretary of state had strayed from the cause, including her vote for the Iraq war and her past support of the Trans Pacific Partnership and praise for the Keystone pipeline (both of which she ultimately opposed.)

You can be a moderate. You can be a progressive. But you cannot be a moderate and a progressive.

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) February 3, 2016

Most progressives that I know don't raise millions of dollars from Wall Street.

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) February 3, 2016

Most progressives I know are firm from day 1 in opposition to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. They didn't have to think about it a whole lot.

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) February 3, 2016

Most progressives that I know were opposed to the Keystone pipeline from day one. Honestly, it wasn’t that complicated.

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) February 3, 2016

Sanders concluded with a tweet listing more than 20 other policy-related complaints about Clinton (although it was most notable for the sly inclusion of the words “pleads guilty” right after her name).

Some other days... pic.twitter.com/7SjQdgiiQr

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) February 3, 2016

As my colleague Clare Foran noted, Sanders made his argument in person at a town-hall forum Wednesday night on CNN. Clinton responded by saying that based on his standards, if she wasn’t a progressive, then neither is President Obama nor Vice President Biden. She even invoked the late liberal icon, Senator Paul Wellstone.

Sanders and Clinton will be able to continue the discussion face-to-face on Thursday night, and for the first time, they won’t have to worry about being interrupted by O’Malley, the former Maryland governor who dropped his bid after winning less than 1 percent of the vote in Iowa. The debate at the University of New Hampshire came together at the last minute as a part of the agreement for the candidates to hold four additional debates over the next few months.

Both candidates are coming off strong performances during Wednesday’s forum, although it’s likely that Clinton will look for a re-do on her answer about earning $675,000 in paid speeches from Goldman Sachs. “I don’t know. That’s what they offered,” she said awkwardly Wednesday, drawing cringes from Democrats and Republicans alike. She has moved swiftly to lower expectations for her performance in Tuesday’s Granite State primary, even claiming that some people urged her to skip the state.

Given Clinton’s strength in South Carolina, New Hampshire isn’t a must-win state for her. But the debate over progressivism is fundamental in a Democratic Party that has moved significantly to the left in the two decades since her husband won his second term. The word “liberal” might not be fully rehabilitated, but the progressive label is now as important to Democrats as conservative is for Republicans. The question of Clinton’s bona fides was bound to explode eventually, and as the two remaining Democratic contenders share the stage alone for the first time, Thursday night seems as good a night as any to fully air it out.

Marco Rubio Proves Obama's Point About Islam

For years, President Obama avoided visiting a mosque in the United States. While the White House never explained why, American Muslims tended to believe he was afraid of the backlash such a visit might inspire from conservatives.

On Wednesday, he finally visited the Islamic Society of Baltimore, and much of the right’s reaction is validating those suspicions. There was some outright dishonesty, like Donald Trump’s implication that Obama is a Muslim: “Maybe he feels comfortable there.” (Memo to The Donald: He didn’t do this until the eighth year of his presidency.) That’s standard Trump fare. More surprising was Marco Rubio’s response:

He gave a speech at a mosque, basically implying that America is discriminating against Muslims. Of course there’s discrimination in America, of every kind. But the bigger issue is radical Islam. This constant pitting people against each other, I can’t stand that. It's hurting our country badly.

Reading Rubio’s remarks, anyone who heard Obama must have thought, “Did he watch the same speech I did?” The answer is most likely not: Rubio is in the middle of a hectic New Hampshire campaign swing, and it’s hard to imagine he spent an hour watching Obama speak. Suffice it to say that the president’s address bore little resemblance to Rubio’s description.

Obama’s speech did speak about incidents of Islamophobia, about slurs and attacks on Muslims and mosques in the U.S. Those accounts are factually true, and the sense of fear among American Muslims—whether one regards it as justified or not—is real. But rather than blame all Americans, Obama said this:

Your fellow Americans stand with you .... That’s not unusual. Because just as so often we only hear about Muslims after a terrorist attack, so often we only hear about Americans’ response to Muslims after a hate crime has happened, we don’t always hear about the extraordinary respect and love and community that so many Americans feel.

Obama’s comments about Islamic extremism were carefully nuanced, but they hardly ignored the problem of radical Islam. He did take a shot at Republicans who criticize him for not referring to “Islamic terrorists” as much as they’d like, but he also said, “It is undeniable that a small fraction of Muslims propagate a perverted interpretation of Islam.” (In the past, Obama has been more reluctant to make that connection, leading to the tortured spectacle of a Christian U.S. president trying to adjudicate Muslim orthodoxy.) He spoke about the need for religious freedom and pluralism at home and abroad, called for Muslims to condemn persecution of Christians in the Middle East, and decried anti-Semitism in Europe—all rebukes of certain strains of Muslim preaching and thought.

When spoken in other contexts, these ideas are mainstays of conservative rhetoric. Religious freedom has been an important rallying cry for American conservatives upset by changing laws on gay equality. Obama mentioned the persecution of Christians during Thursday’s National Prayer Breakfast, without raising Republican ire.

Related Story

Obama to Muslim Americans: 'You’re Right Where You Belong'

In fact, Rubio’s charge of divisiveness only makes sense if one believes that Islam is inherently incompatible with American values. Obama explicitly rejected this view Wednesday, speaking of all the ways that Islam has been a part of the United States since colonial times, and telling his audience, “You’re not Muslim or American. You’re Muslim and American.” (The idea that Islam, a long-standing part of the national culture, is not American echoes arguments that white culture is somehow the “true” American culture, and African American culture is separable from it.)

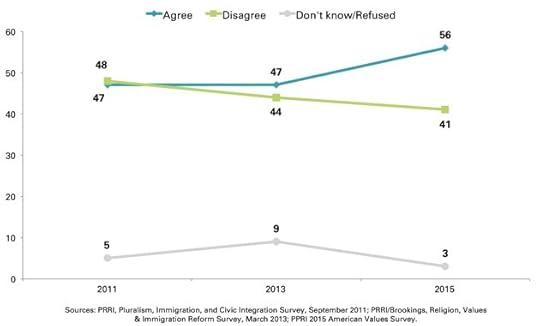

I’m not in any position to determine what Rubio truly believes, but there’s ample evidence that many Americans do feel Islam is incompatible with American values—especially those whose votes Rubio is trying to win in the Republican primary. According to the Public Religion Research Institute’s 2015 American Values Survey, 56 percent of Americans think “the values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life.” The numbers are much higher among Republicans and Tea Party members—76 and 77 percent agree with that statement, respectively. (Only 43 percent of Democrats agree.)

That antipathy is relatively new. Obama’s words, in fact, bore a close resemblance to President George W. Bush’s remarks after 9/11, when he called Islam a religion of peace and criticized discrimination and attacks against American Muslims. (Bush’s brother Jeb notably voiced support for Obama’s mosque visit Wednesday, speaking with some passion about inclusion—and criticizing the president for taking so long to get to a mosque, just as many American Muslims criticized Obama.)

So what changed? Why were those 2001 comments by a Republican president welcomed, while Obama’s very similar comments today were not? Part of it is surely partisanship. But Americans have also become less and less accepting of Islam. When PRRI asked the same question in 2011, for example, just 47 percent of Americans agreed that Islam was incompatible with American values, and 48 percent disagreed.

Are the Values of Islam at Odds With American Values?

Other surveys, using slightly different formulations, produce similar results. “Three weeks after 9/11, an ABC News poll found that Americans had a more favorable view of Islam than unfavorable, 47 percent to 39 percent,” notes Shibley Telhami of the Brookings Institution. “But a decade later, the picture changed dramatically. A poll I conducted in April 2011 showed that 61 percent of Americans expressed unfavorable views of Islam, while only 33 percent expressed favorable views.”

There’s a rich irony to Rubio’s remarks: He is upset that Obama would offer generalizations about Americans’ attitudes, but sees no problem with equally sweeping characterizations of Muslims. But although Obama did not, in fact, say that Americans are anti-Islam, these poll numbers show that he would have been largely accurate if he had. Reflexive attacks on even the most broad, inclusive messages, like the ones Obama delivered Wednesday, seem certain to only widen the gap between American Muslims and their fellow citizens.

Arizona v. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

The U.S. Constitution is the supreme law of the land. In theory, it acts as one unifying body of law for each and every corner of that land. But in practice, the Constitution can mean different things in different places. That’s because federal law divides the United States into 12 geographic districts, each with its own separate federal court of appeals, whose constitutional interpretations apply only within its own circuit.

And now, Arizona wants to switch circuits. Governor Doug Ducey, Senator Jeff Flake, and Representative Matt Salmon announced a joint effort last week to sever their state from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, citing its heavy workload, high rate of reversal, and slow resolution of cases.

Which states are placed in which federal appellate circuits might seem a little wonky, but the practical implications are huge. Except for the few petitions granted by the Supreme Court each year, the circuit courts of appeal are the final arbiter of almost all federal cases.

And Arizona’s leaders have a point. If you designed the American federal judiciary from scratch today, the Ninth Circuit probably wouldn’t exist. Of the 13 circuit courts of appeal, it’s by far the largest, spanning the states of Alaska, Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington, as well as the Pacific territories of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. When Congress created the court in 1891, its vast territory was sparsely inhabited, holding less than 4 percent of the U.S. population. Now, after 125 years of westward migration, more than 20 percent of all Americans live within its jurisdiction.

With great size comes great logistical challenges. “The Ninth Circuit is by far the most overturned and overburdened court in the country, with a 77 percent reversal rate,” Ducey said in a statement last week. “Meanwhile, due to its voluminous caseload and disproportionate size, the Ninth Circuit has an abysmal turnaround time of over 15 months for an average ruling—a figure that’s only going to grow as the docket does.”

In a letter to Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell last October, Ducey offered two possible solutions. First, he proposed that Arizona could be moved into the neighboring Tenth Circuit, which currently stretches from New Mexico to Wyoming.

Alternatively, he suggested that Congress spin off Arizona and “other noncoastal states” into a new Twelfth Circuit, which would logically also include Idaho, Montana, and Nevada. The shrunken Ninth Circuit would then consist of Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington, as well as the Pacific territories.

Splitting the circuit, however, isn’t that easy. Much of the difficulty can be traced to California’s disproportionate influence. The Golden State possesses half of the Ninth Circuit’s population, and none of its neighbors even come close. Cases from the state fill the court’s dockets, most of its judges and staff live and work there, and most of its hearings take place in San Francisco or Pasadena. (The only other city where it holds year-round hearings is Seattle; the court also convenes a smaller number of panels in Alaska and Montana each year.)

And like moons caught in Jupiter’s orbit, California’s neighbors are hindered in their attempt to escape by its mass. If a new circuit court gets California and only one or two other states, the Golden State could overwhelm its docket and its character. If, on the other hand, too many states join California in a new circuit, the court could again become too large to manage.

Proposed splits have received ample study over the last three decades, most recently in 1998, when Congress appointed a commission headed by retired Justice Byron White to reexamine the federal appeals courts’ structure. Central to the commission’s purpose was assessing the viability of splitting the Ninth Circuit. In the end, the commission recommended against it. Instead, it proposed three administrate divisions within the circuit to alleviate logistical burdens while maintaining court cohesion.

“Any realignment of circuits would deprive the West Coast of a mechanism for obtaining a consistent body of federal appellate law, and of the practical advantages of the Ninth Circuit administrative structure,” the commission concluded. “Moreover, it is impossible to create from the current Ninth Circuit two or more circuits that would result in both an acceptable and equitable number of appeals per judge and courts of appeals small enough to operate with the sort of collegiality we envision, unless the State of California were to be split between judicial circuits—an option we believe to be undesirable.”

Splitting the state between two circuits would alleviate the broader problem, the commission reasoned, but at the cost of legal chaos in California itself. No state currently obeys the rulings of two different federal appellate courts, and such an arrangement would invite constant Supreme Court intervention to harmonize their rulings, thereby defeating the purpose of the courts. The commission also rejected the idea of placing California in its own circuit, which would deprive the court of its federal character and give disproportionate influence to a single state's senators when selecting potential judges.

The commission’s aversion to splitting the Ninth Circuit wasn’t shared by the Supreme Court justices at the time, including Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and John Paul Stevens. Justices Anthony Kennedy and Antonin Scalia even proposed a three-circuit split to the commission, with northern California, Hawaii, and Nevada in one circuit, southern California, Arizona and the Pacific territories in a second circuit, and Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington in a third circuit. The commission, however, emphatically rejected the idea of splitting California between two federal circuits.

Carving up large circuits into more manageable ones isn’t completely unprecedented, though. In 1929, Congress split the Eighth Circuit and reorganized the Rocky Mountain states and some of the Great Plains states into the Tenth Circuit. But some historical proposals also had less-than-noble motives. During the 1960s, the Fifth Circuit, which encompassed Texas, Florida, and the Deep South, was among the largest and most overburdened appellate courts in the country. It also had a relatively progressive bench and acted as a bulwark of anti-segregation rulings in the South.

In 1964, Southern legislators proposed a bill that would have split the Fifth Circuit along the Mississippi River into two smaller circuits. The existing judges would be divided between them and new judges would be appointed to fill each bench. Since senators can effectively block judicial nominations through the custom of senatorial courtesy, Southern senators could have exercised significant influence over the new appointments. Civil-rights activists rallied and the plot against the Fifth Circuit failed, but Congress eventually did split the Eleventh Circuit off from it in 1981—out of, as a New York Times editorial noted, “not racism but practicality.”

Arizona obviously isn’t a Jim Crow state, and Ducey and his colleagues aren’t segregationists. But the Ninth Circuit's liberal reputation, deserved or not, frequently hangs over the discussions of its fate. In 1990, Washington Senator Slate Gorton tried to move the Pacific Northwest into its own circuit; critics, including Chief Judge Alfred Goodwin, linked the effort to recent pro-environmental rulings. In 1997, Alaska Senator Ted Stevens led a failed legislative revolt to carve all of the states except California and Nevada into a new Twelfth Circuit after a three-judge panel with no Alaska-based judges ruled on a major Alaska Native case.

Arizona has also suffered a number of major legal defeats at the Ninth Circuit in recent years. The court ruled against the state’s controversial SB1070 immigration law and a policy that denied driver’s licenses to people who entered the country illegally as children, a ban on health benefits for same-sex partners of state employees, a 20-week ban on abortions and tougher restrictions on abortion medications, an anti-day-laborer law, and a ban on pro-life licenses plates, to name a few.

None of the officials who backed splitting the Ninth Circuit last week mentioned these rulings, but the state's continuous record of defeat couldn’t have been far from their minds. Nor are similar complaints far from the Supreme Court justices’ minds. Justice Kennedy, who served on the Ninth Circuit prior to his current job, warned against manipulating the circuit courts for ideological reasons during a House Appropriations Committee hearing in 2007.

“You don’t design a circuit around the perceived political leanings of the judges,” he told the committee. “That’s quite wrong. You design it for other, neutral reasons.” Justice Clarence Thomas, who also testified before the committee, echoed those sentiments.

At the same time, Kennedy also cited “sound structural reasons” why the Ninth Circuit should be split. Because of its size, a three-judge panel consisting of “a circuit judge, a senior judge, and a visiting judge from another circuit or a district court can bind 22 percent of the nation’s population,” he noted. The 29-judge bench is too large and too dispersed to maintain collegiality, Kennedy argued, and having an “amorphous, remote, distant court” makes it hard for the public, the press, and bar associations to be familiar with the judges who serve on it.

There’s no straightforward solution to these confounding problems. In that respect, the debate echoes one that has raged in the United Kingdom, known as the West Lothian question. Why, the question asks, do Scottish Members of Parliament get to vote in Parliament on English laws when English MPs have no voice in Scottish laws passed in the Scottish Assembly?

Thousands of studies and white papers can be found on the question and its possible resolution, but one of the most memorable assessments comes from former Lord Chancellor Darry Irvine. “The best answer to the West Lothian question,” he told the House of Lords during a 1999 debate, “is to stop asking it.”

The Shadow Over Cologne’s Carnival Celebrations

On New Year’s Eve in the German city of Cologne, hundreds of women were harassed, groped, or robbed as revelers rang in 2016. Gangs of men, many drunk, formed rings around young women near the city’s cathedral. In the days and weeks after the holiday, the number of complaints filed to police rose nearly tenfold. Police, outnumbered and unable to control the crowds, described the assaults as a “completely new dimension of crime.”

Now, just over a month later, there’s a small white booth with orange lettering outside Cologne’s cathedral. “Women’s Security Point,” it reads.

The booth is meant to serve as a spot for women and girls who feel threatened during Carnival, a five-day annual street party in the Rhineland region that kicked off Thursday. The festival, which draws hundreds of thousands of people, is one of pure merrymaking, with parades, colorful costumes, masked balls, lots of singing—and plenty of booze. City and police officials have vowed “to do everything in their power” to avoid a repeat of New Year’s Eve in Cologne, the epicenter of the celebrations.

The number of complaints stemming from the wave of crime on New Year’s Eve stands at 945, according to the BBC. About 60 percent are allegations of sexual assault. The wave of crime sparked debate over police response and sexual-assault prevention, as well as Germany’s open-door refugee policy; most of the perpetrators were described as men of Arab or North African origin, and the two who have been arrested are from Morocco and Tunisia.

This year, Cologne police have doubled their usual presence at Carnival to about 2,000 officers, some of whom will wear body cameras. The city’s police chief was fired days after New Year’s Eve for what the German interior ministry called “serious mistakes” in the department’s reaction to the assaults. Cologne police had initially issued a news release that reported most celebrations had gone “peacefully” in the city, but soon retracted it as the scope of the crimes started to become clearer.

Cologne has released guidelines for women participating in Carnival festivities, advising them to stay away from individuals who make them uncomfortable, travel in groups, avoid consuming alcohol alone, and in the event of an attack, “muster up all your rage (scream) and fight back with determination.”

“Women have the right to move freely and without danger in public spaces,” the advisory explained. “It is not the responsibility of women to protect themselves against sexual assaults, either by the way they dress or by avoiding appearing in public.”

The guidelines are markedly different than the advice offered by Cologne’s mayor in the days after the New Year’s Eve assaults. Back then, Henriette Reker, a victim of assault herself, suggested that women could protect themselves from sexual harassment or assault by keeping potential assailants at “arm’s length.” The comment drew backlash for appearing to place the responsibility for the prevention of sexual violence on victims rather than perpetrators.

Deutsche Welle reports that a girls’ high school in Cologne has closed entirely Thursday because it’s near the city’s main train station, where many of the attacks occurred on New Year’s Eve.

The revelation that most of the attackers that night were foreign led some to link the crimes to the 1 million refugees and migrants the German government accepted in 2015. Hundreds-strong protests, some of them violent, against immigration of Muslims sprung up in German cities following the assaults. German Chancellor Angela Merkel vowed to find and prosecute the perpetrators regardless of their backgrounds, and introduced measures that would make it easier to deport asylum-seekers convicted of committing crimes in the country. The proposal is expected to pass the German Parliament. Several thousand people continue to arrive at Germany’s borders each day.

Earlier this week, a welfare organization held training sessions in Cologne for migrants intended to introduce them to the raucous Carnival celebrations. The program, conceived months before New Year’s Eve, advises first-time revelers how to enjoy the festivities without overdoing it, reported the AP’s Daniel Niemann, who sat in on the session.

“Especially gentlemen, if you do it right and if you do it good, charming, nice and not pushing, you might have success with women,” explained one slide. “This is no guarantee. No enforceable right and no promise for a marriage.”

The Mystery of the $63-Million Lotto Ticket

People of California, check your couch cushions and the pockets of that coat you wore that one night, because no one has claimed the $63-million lottery jackpot. At 5 p.m. today, if no one steps forward with the winning numbers, 1-16-30-33-46, and Mega number of 24, then no one wins.

Except, someone has already claimed the jackpot. Brandy Milliner of Los Angeles County has even filed a lawsuit against the the California Lottery alleging a conspiracy.

The winning SuperLotto Plus ticket was sold on August 8 at a 7-Eleven in Chatsworth, California. Milliner said he bought that ticket, mailed it in as proof, then received a letter congratulating him and said he’d have his check in couple months. Instead of becoming California’s newest millionaire, Milliner said lotto officials told him in January that the ticket was “too damaged to be reconstructed,” the Los Angeles Times reported. On top of that, Milliner says the lottery commission won’t send him back his ticket, which he believes they destroyed to cover their tracks.

“The last-minute timing of this is suspicious,” a lottery spokesman told the Times.

Local TV station KTLA has a photo of Milliner’s ticket. It is indeed damaged beyond recognition. Even the clerk at the 7-Eleven where the winning ticket was sold seemed dubious of Milliner’s claim.

“You can’t even read the barcode,” the clerk told KTLA.

Barring an 11th-hour miracle, it seems no one will win. If that happens, it’ll be California’s largest unclaimed jackpot ever. But under lottery rules, if no one has claimed the jackpot after 180 days, the money goes to California’s public schools.

The Postindustrial Electronic Bar-Fly Blues

The soundtrack to this winter, for me, has been the electronic group Junior Boys’ excellent new album Big Black Coat. This means I’m propagating a cliché. Ever since their 2003 debut Last Exit, the many warm reviews for the Canadian band’s songs have overused adjectives about cold: “icy,” “chilly,” “wintry.”

This phenomenon should persist for Big Black Coat, Jeremy Greenspan and Matt Didemus’s first album in five years. The height of Junior Boys’ acclaim came around 2006’s So This Is Goodbye, whose songs—including the new indie classic “In the Morning”—drew comparisons to Depeche Mode and other ’80s synth-poppers. Big Black Coat, though, excavates more underground traditions—Detroit techno, industrial dance music, the early days of drum-machine-backed disco—as its songs spool out patient, hypnotic rhythms rendered in high-hat hisses that sometimes, yes, sound like ice being chipped. One track, “C’mon Baby,” ends in a glorious cloud of static and synthetic pinging that makes me visualize a ship passing a glacier at night. Another, “No One’s Business,” has a slowly swirling arrangement that makes the singing easier and harder to hear at different times; the effect is like a voice calling out in a blizzard. Ugh to these descriptions right?

I wanted to speak with Greenspan to figure out whether the frigid imagery commonly surrounding his music results from his own intentions, or whether he’s annoyed at the fact that his unapologetically mechanical songs keeps getting compared to the weather. Happily, he was cool about it. “I cultivate it to some extent,” he said of the winter theme.

In fact, Big Black Coat is something of an accidental concept album about the struggles of people in his hometown of Hamilton, Canada, a postindustrial city on the banks of Lake Ontario. This explains the desperation and yearning in these songs, as well as the temperature.

Big Black Coat is available February 4th, though it’s currently streaming on NPR.

Kornhaber: Why do you think that whatever techniques you’re using get associated with cold?

Greenspan: When I was about 17 or so, there were a couple pieces of music that I heard for the first time: John Foxx’s Metamatic, the band Japan, and Kraftwerk. They are all music that evoked, visually in me, imagery that was institutional—sort of eerily intuitional in the way that a Cronenberg movie is or a J.G. Ballard book is. That was super influential to me, because I always felt like there was a huge amount of emotion you can convey in these seemingly icy or cold things.

Kornhaber: Did that music feel institutional because it was electronic, or because of the amount of repetition, or something else?

Greenspan: Well in the case of John Foxx and Kraftwerk, it was explicitly institutional in the sense that the lyrics were about that kind of stuff. It probably had to do with the time; there was a certain energy about the changing landscape politically and economically in the ’80s.

For me—and this is where my interest in synth-pop fused with my interest in modern R&B and in dance music—it always has been about a kind of unrepentant futurism in the music. Music that seems like it’s coming from a future or is about the immediate future has always been the music that’s excited me the most, because I’ve always thought of culture as something that’s pulled toward the future. I’m not the kind of person who listens to a lot of music that is of a firmly established genre or something like that.

Kornhaber: It’s interesting because synth-pop, R&B, and a lot of the other things you put in your music kind of code as nostalgic now, don’t they?

Greenspan: Yeah. The funny thing is that even with a band like Kraftwerk when they were starting out, there was a weird retro-futurism to what they were doing—an obsession with notions of the future from the past.

I’m sort of obsessed with nostalgia. I think that’s one of the reasons I still live in my hometown. Every building, every place is super-pregnant with meaning for me, and I think you only get that if you live in the place where you grew up. That figures pretty prominently in my music as well.

Kornhaber: This album does reference a lot of musical history. Do you think it’s important for the listener to be picking up on that?

Greenspan: No. The thing that I think has been my saving grace is that I’m not very good at sounding like the things that I want to sound like. There are producers out there that can listen to something and say “I want to make something that sounds like that,” and then they go home and they make something that sounds like that. I don’t have that skill. Every time I try to make something that sounds like something else, it ends up sounding like me.

If you listen to “C’mon Baby,” that’s me trying to sound like DJ Mustard. It’s so off completely that it’s just ridiculous. The first song on the album, “You Say That”—all the chord structure, everything, came from Gil Scott-Heron. I really don’t think anyone would listen to that song and think “Gil Scott-Heron,” you know? But that’s what I was consciously trying to do.

Kornhaber: What do the words “Big Black Coat” mean to you?

Greenspan: Well, I didn’t realize it until almost after the fact. I wrote all these songs very quickly; I did a whole lot of material and wasn’t too precious about it. The lyric writing was done in much the same way. I wrote stuff and sang it, and the demos stuck, which is different from what I’ve done before, when I edited it.

At the end of the process, the label asked me to write out all the lyrics, which I’d never done before. I wrote them out and I realized they’re all exactly about the same thing: these kind of lonely men that I knew from the bar near my studio in the downtown of my hometown, which is a nowheresville, postindustrial city. The songs are about these guys who are frustrated by their emotional lives and are frustrated by women because they don’t know how to relate to them but they want them.

“There’s misogyny in the record that I was super-aware of. I wanted to make sure people realized that I was writing from a certain perspective.”

So the coat became this kind of metaphor for people who insulate themselves, because the city I live in is a place where people insulate themselves from the cold, both physically and emotionally. It’s just a down-and-out kind of town.

Kornhaber: So it’s not about being a badass and having a big coat?

Greenspan: No—though a little bit of the reason why I chose black was because the album was influenced a lot by my musical roots, which are industrial and techno music. So my nostalgia that I associate with is everyone wearing bomber jackets or trench coats. Big black coats are the uniform for people who are into industrial music.

Kornhaber: So you’re writing from the perspective of these bar-fly guys. Is that why the word “baby” is everywhere in the lyrics?

Greenspan: Yes, exactly. I wrote quickly and I wanted to write in a voice that was sort of—I don’t think “unpoetic” is the word, but sort of had this frame of frustration in it. This feeling like you don’t have the words to express what you’re meaning. So for me “baby” seemed like the operative word, especially in pop music. I have a friend who had a band called the Russian Futurists in Toronto. I remember asking him about some lyrics, like, “What’s this?” He said, “It’s always ‘baby,’ it’s always ‘baby.’” It’s this stand-in word for emotional resonance that can’t be articulated.

Kornhaber: Do you yourself identify with the subjects of these songs?

Greenspan: I do to some extent. The one big thing, though, is that a lot of the songs were inspired by the people in this bar near where my studio is, and I don’t drink at all. It’s kind of like I’m inspired by alcoholism in some way; I have this kind of outsider perspective. And I don’t feel down and out.

I do relate to the people I’m writing about, but I hope not too much. There’s a lot of misogyny in the record that I was super-aware of while I was doing it, but I wanted to make sure people realized that I was writing from a certain perspective.

Kornhaber: You’re not a drinker at all?

Greenspan: I’ve never drank. I can’t! I have this weird thing where after one drink I get impossibly dizzy. I get dizzy before drunk.

Kornhaber: Dance music is so much in the clubs, in the bars—you never connected on that level?

Greenspan: I used to be connected to dance music when dance music was more about drugs. I definitely had a period of my life when I was into that. Never alcohol though.

Kornhaber: As far as the way the songs sound, do you think of songwriting and instrumentation and production as separate things, or are they the same thing to you?

Greenspan: They’ve become more and more the same thing. My strategy for writing has changed a bit. The last two records previous to this one, the notion was I would do the songwriting by fiddling around with the equipment and then I would take a small body of work and really hone it. I think of songwriting as a great skill and respect people who are traditional songwriters. But for this new album I wanted to go away from that to some extent. I wanted the songs to retain their, I don’t know if “improvisational” is the right word—this core of being born out of happy accident.

I get into a studio, I set up all my equipment, and I press play, and I just fiddle around until something happens. When something happens I record it, and then traditionally I would take that and build it into a song. For this album I wanted the process of building it into a song to last as shortly as possible so that the energy of the first spark was retained.

Kornhaber: People tend to think there’s the song and then there’s the recording, and that you should be able to play the bones of the song on your guitar. But listening to some of your songs, they work because of what you’re doing in the studio.

Greenspan: Exactly. One of my favorite bands of all time is the band 10cc. They’re incredible songwriters just in the traditional sense, but those songs live and breathe because all of this studio trickery they’re doing. If you were to play those songs on a guitar or piano, they don’t work.

Stephen Sondheim wrote this book about lyric writing, and it opens up and says, “Lyrics are not poems.” Lyrics are not things that exist outside of songs. It’s words set to music, and so divorcing your lyrics from songs for me is just as stupid as divorcing your song from the context of recording it.

Kornhaber: I think about that song “No One’s Business,” and it’s all about how it moves around in your ear.

Greenspan: I’m glad you mentioned that one, because we did something really strange with that song. I have a really terrific mastering engineer, Bob Weston—he’s in the band Shellac and he engineered Nirvana records.That song actually starts one volume and ends at another volume, and we did that in the mastering process, which is super unusual. Mastering is a process of compressing, so you’re changing the perception of the volume to the listener. You don’t want one song to sound super loud and then the next song on your record to sound quiet. For that song we played with that so that, in terms of your perceived volume, it starts at one volume and ends at another.

Kornhaber: The end of “C’mon Baby”—what is going on there?

Greenspan: It sounds like a guitar, but there’s no guitar at all. It’s just a distorted Alpha Juno synthesizer being modulated by something called a low-frequency oscillator, with tons and tons of delay on it.

Kornhaber: Was that the answer to some sort of problem? Like, “I want some sort of emotional effect, here’s how to achieve it”?

Greenspan: That was just a moment of total madness. This is going to sound cheesy and pretentious but there’s something about being in a studio where it feels like a divination ritual. You’re throwing bones and looking at the result. My studio is very small physically, and the central piece of the studio is a patch bay and a modular synthesizer. You just start patching away and you start losing your focus and your sense of where everything is plugged in, and you just get into this state where you’re walking around the studio as things play back. You have to sit there for hours playing with total garbage and noise. But as long as you have the “record” button ready to go, you’re ready to write.

An American Hijab at the Olympics

At the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Ibtihaj Muhammad, a 30-year-old American, will wear a hijab beneath her beekeeper-like fencing mask. It’ll be the first time a competing U.S. athlete has worn a hijab at the Olympics.

Muhammad, who competes in saber fencing, became the first Muslim woman to join the U.S. team. Since then, she has won bronze medals at two out of the three World Cups she’s traveled to. This is her first Olympic Games.

Although the official U.S. fencing team won’t be announced until April, last week, at the World Cup in Greece, Muhammad earned enough points to guarantee she’ll parry in Rio. On Tuesday, this news earned her the most official of shout-outs.

On the way to his first visit as president to a mosque in the U.S., President Obama met with a small group of Muslim community leaders in Maryland. Muhammad was among the crowd. The president asked her to stand and the whole room applauded. Later, Obama said he “told her to bring home the gold! Not to put any pressure on her.”

Athletes in hijabs, whether their sport is soccer, judo, basketball, boxing, in high schools or at the Olympics, have all at some point been controversial. There were safety concerns with the traditional headscarves, and rules that sanctioned appropriate garb. Male-dominated sports have been slow to accommodate not just women, but also women with strong religious beliefs.

Fencing, however, faced few of these challenges. Its uniform covers the head, arms, and legs and this, in part, was why as a 13-year-old girl in New Jersey, Muhammad chose the sport.

“My parents were looking for a sport for me to play where I wouldn’t have to alter the uniform,” she told BuzzFeed.

Duke University later recruited Muhammad for its team. After she graduated, she decided to stick with fencing, she said, because “it’s always been a white sport reserved for people with money.” And she wanted to shake it up a bit.

There’s been a lot of that in other sports, too. In 2011, FIFA, soccer’s governing body, blocked the women’s Iranian soccer team from its qualifying match because the players wore hijabs. FIFA said it was too risky, and might cause head or neck injuries. It was a decision that prompted then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to call FIFA leaders “dictators and colonialists who want to impose their lifestyle on others.” In 2012 FIFA decided, as an experiment, to allow the hijab for two years. In that time, none of its dire predictions came true and FIFA eventually lifted its hijab ban.

The year 2012 and the London Olympics were momentous for the hijab in sports. It was the year Aya Medany, the Egyptian pentathlete, competed in a hijab. It was the first year Saudi Arabia sent (partly due to threat) women to the Olympics, including a judoka as well as an 800-meter runner, both of whom wore hijabs. And it was the year the hijab-wearing Khadija Mohammed competed in weightlifting, something only possible because her six-woman team from the United Arab Emirates had pushed the sport to ease its dress code rules.

This thawing has even opened a new sportswear market. There’s a breathable and sweat-whisking hijab for runners; fleece-lined versions for the outdoor sports enthusiast; and, of course, the—now FIFA approved––soccer version. Even the House of Fraser, the British department store, sells “sporty hijabs.”

In just the past five years, much of the world has changed the way it allows Muslim women to compete in international sports. Now, with Muhammad, the U.S. has joined.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower