Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 233

February 11, 2016

Clinton Tries to Stop the Sanders Surge

Who’s the Democratic front-runner now?

When Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders meet in Milwaukee tonight, you might think it’s Sanders. The sixth Democratic debate comes just three days after the Vermont senator’s landslide win in the New Hampshire primary, and the only question seems to be just how aggressive Clinton will be in going after him.

The former secretary of state was clearly humbled, if not outright humiliated, in the state that had once given both her and her husband new life in past presidential campaigns. Sanders had been expected to win handily, but his 22-point margin was even larger than forecast and cut across almost all demographics: Not only did he dominate among his core group of younger voters, but he even won among women overall, according to exit polls.

While the debate airing on PBS will take place in Wisconsin, the candidates’ focus is in Nevada and South Carolina, which hold their contests on February 20 and 27, respectively. And unlike Iowa and New Hampshire, the key constituencies will be minority voters. Immediately after claiming his Granite State win, Sanders flew to New York to meet with the Reverend Al Sharpton in Harlem. Clinton responded by announcing the endorsement of the Congressional Black Caucus’s political action committee. At its press conference on Thursday, Representative John Lewis offered this withering assessment of Sanders’s role in the civil-rights movement: “I never saw him. I never met him.”

Some Democrats have complained that issues of policing, criminal justice, and immigration have gotten short shrift in previous debates, but that shouldn’t be the case with Thursday’s telecast being moderated by PBS. Clinton will also hope for a focus on foreign policy, which in the past has forced Sanders off his core message of inequality. The Clinton campaign also criticized him for missing a Senate vote this week on North Korea sanctions, suggesting it underscored his lack of interest in foreign policy. (Sanders released a statement saying he supported additional sanctions.)

And if the last Democratic debate, just a week ago, was a referendum on which candidate was the true progressive, this one could turn into a referendum on President Obama. With an eye toward South Carolina’s large bloc of African American voters, Clinton has sought to link herself closely to the president, while in an interview on MSNBC, Sanders suggested he would provide more “presidential leadership” in working with Congress. (Clinton spokesman Brian Fallon replied on Twitter that this was “absurd.”)

Just how worried should Clinton be? A couple weeks ago, the thinking among most pundits had been that after a narrow win in Iowa, she could weather a defeat in New Hampshire because of her “firewall” in Nevada and South Carolina, where the diverse electorate is more favorable to her. And that may well still be the case. But the Clinton campaign has projected more nervousness in recent days. After the New Hampshire landslide, it immediately began to downplay her chances of a big victory in Nevada while arguing that the really importance races were not until the bigger states that voted in March. And there’s already been talk about the nearly 400 superdelegates that Clinton counts in her corner, which could provide a buffer against more Sanders victories—if they don’t start to peel away. The obvious worry is the snowball effect: Will the enthusiasm behind Sanders extend beyond his base of young, white voters and pick off black and Latino voters as well? Is the support for Clinton softer than it appears?

With the recent addition of four more Democratic debates, complaints about the schedule have died down. But after their matchup in New Hampshire a week ago, this will be the last meeting for Sanders and Clinton until after Super Tuesday on March 1. Clinton may still have the advantage, but Thursday is a key moment for her to stop the Sanders surge.

Maine Governor Paul LePage's Latest Stunt

Paul LePage wears many hats: governor, anti-press crusader, fount of racist innuendo, advocate for vigilante justice. Now he plans to add Maine education commissioner, too.

On Thursday, he said he would withdraw the nomination of acting Education Commissioner William Beardsley for a permanent role, citing insurmountable Democratic opposition in the state legislature to Beardsley’s elevation.

Related Story

“I will be the commissioner,” LePage said. Or as the governor might say in his native French, “l’etat, c’est moi.”

Senator Rebecca Millett, the top Democrat on the education committee, accused LePage of “making a mockery of the role of commissioner and the important responsibilities that fall beneath the commissioner and seriousness of educating our children.” Asked what might have motivated LePage, she told the Portland Press Herald, “I can’t explain why the governor does anything.”

Beardsley is currently serving as acting commissioner, and when that appointments runs out, he will return to being deputy commissioner, while LePage will lead the office. His answer was prompted by a question from the superintendent of Lewiston schools, who asked when the education department might get permanent leadership, . It’s perhaps not quite what the superintendent had in mind.

Education has been a hotly contested issue during LePage’s term. The Republican is a major proponent of charter schools, and signed legislation authorizing them in Maine. He also, by his own admission, used state funds to pressure a charitable organization into rescinding a job offer to the Democratic state house speaker, a vocal opponent of charter schools.

It’s already been a banner week for LePage, who’s prone to outrageous and offensive comments. He followed through on a threat not to deliver a state of the state address, instead sending a letter to the legislature, which the Bangor Daily News characterized as “terse” and “insulting.” For example, LePage wrote, “For the past year, socialist politicians in Augusta have been dragging my Administration's employees before a kangaroo court and plotting meaningless impeachment proceedings. While your colleagues were engaged in these silly public relations stunts, Mainers were literally dying on the streets.”

A group of legislators attempted to impeach LePage last month, but came up short.

This week he also returned to the about drug dealers “by the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty” who “come up here, they sell their heroin, then they go back home. Incidentally, half the time they impregnate a young, white girl before they leave.” He also suggested bringing back the guillotine to publicly execute drug dealers and called for vigilante justice against pushers: “Everybody in Maine, we have constitutional carry. Load up and get rid of the drug dealers.” (Capital punishment for drug trafficking might be unconstitutional; extrajudicial killing is definitely unconstitutional.)

On Tuesday, he argued that the remarks had all been part of a larger plan to get attention for the heroin epidemic in the state.

"I had to go scream at the top of my lungs about black dealers coming in and doing the things that they’re doing to our state," he said. "I had to scream about guillotines and those types of things before they were embarrassed into giving us a handful of DEA agents. That is what it takes with this 127th [legislature]. It takes outrageous comments and outrageous actions to get them off the dime."

As the Press Herald noted, however, the latest rationale is at odds with LePage’s earlier insistence that his critics, and not he, had injected race into the matter.

It’s been a tough week for LePage: New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, whom he had endorsed for president, dropped out of the race. Yet Christie’s exit seems to clear the way for LePage to back Donald Trump—a soul sibling in the hunt for every more offensive speech.

Firewatch and the Addictiveness of Lonely Video Games

Solitude, it turns out, can be addictive. So I learned playing the new hit indie game Firewatch, where all the action amounts to you, the player, being alone in the woods. You’re a lookout assigned to a summer posting in the Shoshone National Forest of Wyoming in 1989, meaning your job consists of nothing more than wandering around, clearing brush, and calling in any fires you might spot. Most video games equip you with tools and weapons, complex missions, and action sequences. All Firewatch gives you is a map, a compass, and a walkie-talkie—but it’s still one of the most compelling video games I’ve ever played.

Related Story

It’s the latest in a quiet movement of video games, more psychological products that tap into the atmosphere and wonder of loneliness rather than looking for the simpler thrills the medium usually provides. It’s tempting to trace this trend’s origins back to Minecraft, which launched in 2009 and became a worldwide phenomenon on the back of its extraordinary simplicity. But in Minecraft, you start armed only with your bare hands in a world of monsters, and can eventually upgrade into a city-builder armed with powerful tools. Firewatch is a more intimate affair: a short story, playable over a few hours, that succeeds first and foremost as an emotional experience.

Its closer cousins are indie games like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (released last year), Dear Esther (2012), and perhaps most famously, Gone Home (2013)—titles referred to as “walking simulators,” a classification that initially felt mildly pejorative but has managed to stick. Minecraft, which initially prospered on the PC, was an early success story in the now-flourishing world of independent games—easily bought online and downloaded onto mass-market consoles like the Playstation 4 and Xbox One. Such games rarely cost much money or require tons of processing power, partly because they’re driven entirely by story and mood.

In Everybody’s Gone to Rapture, you play as a person exploring a small English town where everyone has mysteriously disappeared. In Dear Esther, made by the same indie studio, you wander an uninhabited island in the Scottish Hebrides, slowly learning the story of a woman who has died in a car accident. In Gone Home, you are a young woman returning to her family home, only to find it empty, prompting you to piece together the past to understand the present. Solitude is crucial to all of these games: Like most “first-person” games, you’re an unseen actor progressing through various environments to advance the story. Unlike most such games, though, in walking simulators you don’t have to shoot any soldiers or fight any monsters along the way.

Firewatch is an intimate affair that succeeds first and foremost as an emotional experience.

Such games would have been unimaginable even 10 years ago, when the quality of writing and voice acting in the medium was rudimentary at best. One reason Firewatch works so well is the astonishing naturalism of its dialogue, which powers the game as you wander through its beautifully designed world (created in part by the Internet-renowned Olly Moss). The game’s story is driven by conversations you have over your walkie-talkie with your fellow lookout Delilah. Your chats start out as gently funny, move into deeper, more heartfelt territory, and then lurch into Lynchian terror as you begin to realize all is not as it seems.

The voice work is done by Rich Sommer (of Mad Men fame) and the veteran video-game actress Cissy Jones, and Moss’s painterly visuals are at once comforting and suspiciously beautiful. When things start to go awry, the tranquility of the environment starts to seem threatening without anything actually changing. Most walking simulators lean heavily on the details of their environment, but Firewatch is particularly successful in using its design to move along its overarching story (which I won’t spoil in any detail).

But more than anything, Firewatch is a game that explores the state of being alone, both psychologically and physically. You hang on your walkie-talkie conversations with Delilah, mostly small talk and technical information, because staving off silence feels so important. Most games these days have radars, complex heads-up displays, and arrows pointing to your next objective on the screen at all times; in Firewatch all you can do is mark up a paper map in your pocket that you need to take out and look at every time you want to get your bearings. Because of details like these, there’s a sense of accomplishment to every step you take.

The beautiful thing about the rise of walking simulators is that it shows just how inventive the gaming industry has gotten in recent years, and how huge a triumph a small team (Firewatch was created by a crew of only 11 at the indie studio Campo Santo) can pull off without the funding of a major studio. Video-game production is a multi-billion dollar business, pumping out blockbuster action franchises and sequels with the regularity of any global entertainment industry. It bodes well for the industry’s future that, this week, the only title anybody wants to talk about is one that’s risen entirely thanks to its own ingenuity.

'Insult to Homicide': Cleveland Sues Tamir Rice's Family for Ambulance Fees

Updated on February 11 at 2:34 p.m.

What’s more outrageous than having a police officer shoot an unarmed 12-year-old, failing to provide medical care, keeping his family forcibly from the scene, and then declining to indict the officer for the death? In most cases, little. But the city of Cleveland has found a way: It is suing Tamir Rice’s family for not paying the ambulance bill after a Cleveland cop shot and killed the boy in November 2014.

As the Scene reports, Cleveland has filed a claim in probate court, seeking $500 from Rice’s estate to pay for emergency medical services rendered after Officer Timothy Loehmann fatally shot the boy. The charge is especially galling because Loehmann and another officer apparently had no training or equipment to provide aid to Rice after they shot him. They did nothing for four minutes until an FBI agent who happened to be nearby took over.

“The callousness, insensitivity, and poor judgment required for the city to send a bill—its own police officers having slain 12-year-old Tamir—is breathtaking,” Subodh Chandra, a Rice family attorney, said in a statement. “This adds insult to homicide.”

On Thursday, Mayor Frank Jackson apologized for any pain caused by the suit and bill, which he attributed to a clerical error. He said the Rice family was never sent the preliminary bill, and the claim should have been made to the family’s insurance provider. The city says it has withdrawn the claim.

Yet this is not even the first moment the city has done such a thing. In March, Jackson apologized for language that Cleveland had used in a brief that blamed Rice for causing his own death by “failure ... to exercise due care to avoid injury.” Jackson called the language insensitive, but said it had been used to preserve the city’s legal defenses. That seems to cut straight to the heart of the matter: While Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty failed to indict Loehmann in the case, it seems telling the wording in the brief is so inflammatory to a lay public the mayor felt compelled to apologize.

Despite the criminal case against Loehmann ending without indictment, Rice’s family has filed a civil lawsuit. The city paid out more than $10 million to victims of police brutality between 2004 and 2014.

It’s hard to know just how common it is for a city to bill the family of a victim of police violence. In one similar case in 2012, the city of New York billed Laverne Dobbinson $710 for a dent in a police car. The car struck and killed her son Tamon Robinson; an officer was chasing him after spotting him trying to steal pavers. After public backlash, a law firm collecting the debt dropped its effort. A New York Police Department spokesman told The New York Times, “We don’t know any instance where we send letters like that. I’m not sure how it came out.”

Just this week, a Chicago officer filed a suit requesting $10 million in damages from the estate of Quintonio LeGrier, a college student he shot and killed on December 26.

But asking Rice’s family to pay for expenses after police shot him is reminiscent of little so much as “bullet fees,” charges reportedly issued by repressive governments after executions. In 2009, for instance, The Wall Street Journal reported the family of a young man shot during protests in Tehran was being asked to pay $3,000 to retrieve his body, as compensation for the bullet used by Iranian security forces to kill him. It’s also been widely reported the Chinese government charged a bullet fee to the families of people it executed. Those regimes are hardly seem like the model the Forest City wants to follow—even if its police has a similar track record of excessive violence.

Related Videos

An animated recollection of a violent police encounter

Is This the End for Fashion Week?

New York Fashion Week officially starts on Thursday, but the hottest show of the season happened the night before, when Hedi Slimane presented his fall menswear collection for Saint Laurent Paris at the Hollywood Palladium, 2,500 miles from Manhattan. The space is a massive concert venue—not the kind of place typically used for a high-fashion debut. But Saint Laurent is only one of a number of major labels abandoning the tents and runways of seasonal shows for something a little less conventional.

Does Fashion Week matter anymore? It’s a question that comes up every year in some form or another, along with debates over whether models are too skinny, and whether the industry should ditch fur. But it’s not a rhetorical one: Even in a generic tent or studio space, the cost of mounting a show averages just under half a million dollars. With up to two dozen shows per day in New York alone, many scheduled at the same time, it’s a game of diminishing returns for designers, in terms of press coverage as well as sales.

The glamour of live fashion shows—from the star-studded front row to the backstage drama—has become enshrined in American pop culture, eliciting tears in the Project Runway finale and laughs in the Zoolander films. But labels are increasingly (and rightfully) questioning the value of traditional, seasonal runway shows in a time of social media. Big names from Misha Nonoo to Tom Ford are already experimenting with possible alternatives, including informal “presentations” that bring models and journalists together, and videos, pop-up shops, and Instagram feeds instead of live shows. It’s a sea change that could bring renewed energy, creativity, and engagement to an industry that, for all its innovation, is still often reluctant to depart from convention.

Consider how the anachronistic notion of seasonal collections has persisted in a global fashion market: It may be freezing in New York right now, but it’s 90 degrees in Singapore. Online shopping has made it possible to buy clothes from around the world, at any time of year, for any type of weather. Bill Blass—rebooted last fall as an online-only company—is eschewing seasonal offerings in favor of adding new product every few weeks, a business model pioneered by fast-fashion purveyors like Zara and H&M. (Fittingly, Blass himself was an early advocate of seasonless clothes, which he considered more appropriate to the jet-set lifestyles of his socialite clients.)

Joel Ryan / AP

The enduring practice of seasonal collections has a human toll. The sad, self-destructive cases of Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, and L’Wren Scott have put the punishing schedules of fashion designers in the spotlight. Raf Simons was creating six collections per year for Christian Dior when he stepped down abruptly in October, citing the relentless pressure of the job. For many designers, spring and fall ready-to-wear collections are joined by haute couture, menswear, and “pre-collections,” meaning resort (or cruise) and pre-fall. In addition to being creatively demanding, each collection brings the frightening prospect of critical failure and financial disaster.

Editors, too, suffer from burnout, following the fashion circus from New York to Paris, London, and Milan. Diane von Furstenberg, the chairman of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, suggested in 2013 that “someday designers might show their collections only digitally”—a step that would go a long way toward putting designers—and journalists—of all backgrounds and budgets on an equal playing field. More recently, the CFDA indicated it was considering changing the format of Fashion Week, in response to concerns of consumers and designers alike. Steven Kolb, the council’s president, said: “We want to take a broken system and create a new system ... 95 percent of the people I’ve spoken to say, ‘Amen.’”

There are plenty of labels and designers who are continuing to do things mostly as they’ve been done for decades—Ralph Lauren, Michael Kors, and Calvin Klein will all be participating in New York Fashion Week as usual. But their choice appears to be more like an attempt to wait to see where the industry goes next than a dedicated effort to preserve the status quo.

* * *

The history of how fashion shows came about points to how ill-suited the system is to a modern environment. The incongruous notion of designers presenting their fall collections in February (and their spring collections in September) can be traced all the way back Louis XIV, who imposed a strict seasonal schedule on the French textile industry in an effort to strengthen his kingdom’s finances. New textiles appeared seasonally, twice a year, encouraging people to buy more of them and on a predictable schedule. Regardless of the weather, the summer fashion season began promptly on Pentecost (the seventh Sunday after Easter), with winter clothes donned on All Saint’s Day (November 1). It was a brilliant economic stimulus plan, forcing French consumers to replace their clothes semi-annually because the textile patterns had been superseded by new ones, not because the garments themselves had worn out.

Labels are increasingly (and rightfully) questioning the value of traditional, seasonal runway shows.

The runway aspect of the equation arrived in the late 19th century, when Charles Frederick Worth—the so-called “Father of Haute Couture”—became the first designer to present seasonal collections on live models in his atelier. While all couture was custom-made, Worth’s innovation was to offer his clients a predetermined range of styles in his own inimitable taste, from which they could choose their individually tailored wardrobes. Worth’s system became codified by the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, founded in 1910. In the aftermath of World War I, the Chambre Syndicale established a fixed calendar of live fashion shows timed for the convenience of the French fashion industry, the media, and foreign buyers, who paid for the right to produce licensed copies of Paris couture. The long lead time allowed clients to choose their clothes from the runway, and received the carefully hand-finished garments a few months later, just as the weather began to change.

The biannual media feeding frenzy now known as New York Fashion Week was launched in 1943 by the fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert; tellingly, it was originally called Press Week. With the once-dominant French fashion industry crippled by World War II, Lambert spotted an opportunity to promote American designers. Press Week had a transformative effect on both the internal and external perception of the American fashion industry, and changed the way Americans considered and consumed fashion. It was the first of the “Big Four” fashion weeks; Milan did not follow until 1958, trailed by Paris in 1973 and London in 1984.

At a time when most “American” fashion houses were accustomed to simply knocking off French couture on the cheap, Press Week served as a timely reminder that New York did have its own ideas to offer. Thanks to the war, New York manufacturers weren’t able to copy or expected to compete with Paris. Indeed, Lambert’s chief accomplishment was to brand New York as a style capital in its own right, if not the style capital. Press Week brought America’s fashion reporters to New York en masse, to be dazzled by the collective creativity and skill of Seventh Avenue. Lambert arranged for journalists’ travel expenses to be paid and ensured that a good time was had by all, arranging cocktail parties with the New York fashion press, audiences with the mayor, and tickets to Broadway shows. Fashion was presented as being an integral part of the city’s character.

The history of how fashion shows came about points to how ill-fitted the system is to a modern environment.

Before Press Week, regional reporters had shadowed hometown buyers—the influential gatekeepers who decided what got sold in department stores and specialty boutiques nationwide—as they placed orders in Seventh Avenue showrooms. Instead of these informal viewings, Lambert staged fashion shows—or “mannequin parades”—like those regularly held by French houses, subtly elevating New York ready-to-wear to the status of Parisian couture. These were low-tech productions, enlivened by the designers’ personality and passion rather than sophisticated stagecraft or pulsing soundtracks. Although conceived as a wartime stopgap, Press Week continued unabated after the war ended; in fact, it became more important than ever as American women got over their wartime frugality and the Paris fashion industry rebounded. Within a few years, Press Week stretched to nine days.

Eventually, Press Week became known as Fashion Week. But it remains a publicity-generating machine, even if today’s front-row seats are reserved for bloggers and street-style stars, as well as A-list celebrities and top-tier editors, all of whose tweets, reviews, and photos circulate within minutes rather than weeks.

Jonathan Short / AP

But rather than catering to the press, designers are increasingly pitching their runway shows to consumers rather than journalists, bypassing the critical eye of the media. More seats at Fashion Week are being reserved for regular customers, not reporters and retailers. Shows livestreamed (if not televised) to the uninvited public are now de rigeur; designers can also connect with their fans directly on social media, for better or for worse (Marc Jacobs made headlines last year for accidentally Instagramming nude selfies). A few years ago, “seasonless” was the industry’s favorite buzzword, signifying clothes that could work for multiple seasons; today, it’s “in-season,” meaning that the clothes shown on the runway—and instantly shared around the world—should be available to buy immediately rather than six months later.

Fans have become accustomed to seeing celebrities model designer samples on the red carpet at the Oscars or the Met Ball, just after their runway debut. But the publicity generated by these high-profile appearances isn’t free of drawbacks: Customers are frustrated when they can’t find runway looks in stores, and by the time they arrive there, they’re old news. The Paris-based designer Esteban Cortázar has struggled for years to close this gap; the sculptural, sequined navy gown Cate Blanchett wore to the London Film Festival in October was in stores by Christmas, thanks to Cortázar’s carefully coordinated network of suppliers and retailers. Proenza Schouler took a simpler approach when they showed their pre-fall collection to the press in December: They embargoed reviews and photos until the clothes hit stores later this spring.

More designers are pitching their runway shows to consumers rather than journalists, bypassing the critical eye of the media.

Both of these tactics achieved the same end result: a shorter interval between the runway and retail. But a different strategy is quickly gaining momentum within the industry: replacing the six-months-early Fashion Week with one geared to a “retail” or “consumer” schedule. On Friday, Tom Ford announced that he will not show at Fashion Week this season, instead debuting his fall 2016 collection to the press and public in September, as it arrives in stores. While he may do so in a runway show with all the usual trappings, the excitement it generates won’t have six months to dissipate. On the same day, Burberry unveiled plans to change the way it presents it collections, condensing its current four collections into two “seasonless” shows per year and releasing the clothes to consumers worldwide immediately following the shows. Paul Smith and Vetements have already followed suit.

For all three, opting out of the traditional Fashion Week schedule will have the added advantage of allowing them to combine their men’s and women’s lines into one show, just as Slimane did Wednesday. Rebecca Minkoff will use her Fashion Week slot on Saturday to show a slightly revamped version of the spring/summer 2016 collection she debuted in September, not her fall/winter one. Like Ford, Misha Nonoo is sitting out Fashion Week so she can debut her fall collection in September. While this strategy has obvious benefits to shoppers craving instant gratification (or a heavy coat in January) it will also thwart the knockoff artists who have plagued the fashion industry in recent years. As von Furstenberg has admitted, under the current system, “the only people who benefit are the people who copy it.”

In this consumer-friendly climate, store openings have become the new seasons. Last fall, the highlight of New York Fashion Week was an unofficial presentation by a French label, the house of Givenchy: a no-expenses-spared, 9/11-themed runway extravaganza staged at Pier 29 on the anniversary of 9/11, celebrating the opening of the label’s Manhattan flagship store. The show was notable for being open to the public (via a lottery) as well as hundreds of invited celebrities, reporters, and industry insiders; it was also livestreamed to a global audience that dwarfed its actual audience.

A few months earlier, Valentino moved its couture show from Rome to Paris, in honor of its new boutique there, and the Italian label Max Mara presented its resort collection in its new, three-story London flagship. In April, following the opening of its Rodeo Drive location, Burberry took over L.A.’s Griffith Observatory for a runway show and party for 700 guests, including Anna Wintour, Elton John, Naomi Campbell, John Boyega, Cara Delevingne, and the Beckham family, plus a battalion of Grenadier Guards. The Los Angeles Times called it “a high point in Anglo-Angeleno relations.” This year, the New York-based designer Rachel Comey will skip Fashion Week in favor of a March show in Los Angeles, where she’s opening her first West Coast boutique.

Other designers have coped with the limitations of Fashion Week by pouring money into their off-season or “pre-collection” presentations, where there’s less competition for media coverage (and, potentially, a longer window for sales). Chanel launched the current trend for splashy “destination” fashion shows for its off-season collections, staging lavish junkets to exotic destinations like Dubai and St. Tropez. Louis Vuitton chose Bob Hope’s modernist mansion in Palm Springs as the backdrop to its 2016 resort collection (the models paraded around the pool in lieu of a runway). Last month, Stella McCartney staged her pre-fall show in a Los Angeles record shop. In October, Chanel smugly announced that its 2017 resort collection will be presented in Havana, Cuba; Gucci countered with Westminster Abbey—not exactly the first locale that comes to mind when one thinks of resort wear, but groundbreaking in its own right.

At this rate, it won’t be long before we see resort shows in space. It’s precisely this kind of one-upmanship that’s driving so many designers to opt out of the runaway race, if not the fashion business itself, as Elbaz has done. By the time the CFDA figures out a permanent place to pitch its tents for future Fashion Weeks, the runway’s time may have run out. But as long as labels are taking the initiative and breaking from the norm—and as long as the public continues to embrace their efforts—the industry itself may soon find itself more refreshed, relevant, and healthier than it’s been in years.

Rising Tensions on the Korean Peninsula

North Korea has seized the Kaesong Industrial Complex, declared it a military zone, expelled South Koreans who work there, and called Seoul’s suspension of operations at the complex a “dangerous declaration of war.”

“The frozen equipment, materials and products will be managed by the committee of Gaeseong people,” said a statement from the North’s Committee for Peaceful Unification of the Fatherland. “From 10 p.m. on Feb. 11, (the North) will seal off the industrial park and nearby military demarcation line, shut the western overland route and declare the park as a military off-limit zone.”

The North also ordered 248 South Koreans at the complex to leave the country by 5 p.m. Thursday with their personal belongings, adding it would cut all lines of communication with the South, and the cross-border highway that connects the two countries. The AP reported some South Koreans were still at the complex past that deadline and had been told to await instructions from Seoul. The Korea Herald reported that trucks from South Korea returned home with workers and equipment.

“I feel bitter when I think about the possibility that I might lose my job due to the suspension of the factory operations,” Yun Sang-eun, a worker who drove a 22-ton truck back to the South with factory products from Gaeseong, told the newspaper.

South Korean business groups had called their government’s decision hasty.

More than 120 South Korean companies operate in the Kaeseong complex, which is located in the North Korean city of the same name and was established in 2004 as a symbol of cooperation between the two countries. The facility employs more than 50,000 North Korean workers, has earned Pyongyang about $515 million since it opened, and provides the North one of its few sources of hard currency. The workers there earn about $100 million annually, of which 30 percent goes to the government. In turn, South Korean companies get access to cheap labor.

South Korea’s suspension of activities at Kaesong on Wednesday came in retaliation for North Korea’s recent rocket launch and nuclear test.

United States v. Ferguson

The Justice Department filed a wide-ranging lawsuit against Ferguson, Missouri, in federal court Wednesday, accusing the municipality of “a pattern or practice of law enforcement conduct that violates the Constitution and federal civil rights laws,” Attorney General Loretta Lynch announced.

“Residents of Ferguson have suffered the deprivation of their constitutional rights—the rights guaranteed to all Americans—for decades,” Lynch said. “They have waited decades for justice. They should not be forced to wait any longer.”

The lawsuit’s allegations mirror those in the Justice Department’s landmark Ferguson Report, which was released last March on the same day as a separate report clearing Officer Darren Wilson of civil-rights violations for the shooting death of Michael Brown in August 2014. Brown’s death, alongside the high-profile shootings of unarmed black men and women in other cities, led to violent protests in Ferguson and ignited a national debate over race and policing in the U.S.

Although federal investigators declined to prosecute Wilson for Brown’s death in one report, they effectively indicted Ferguson itself in the other, accusing the city of flagrantly violating federal law and the First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendments. The Ferguson Report describes a municipal government transformed into what my colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates described as a system of plunder, funded by exorbitant court fines levied against the town’s impoverished black residents, and enforced by a police department for whom the Bill of Rights was an alien concept.

Justice Department lawyers filed the lawsuit Wednesday, a day after the Ferguson City Council unanimously voted to amend a proposed reform agreement negotiated between the city and the federal government. Both sides labored for months to craft a consent decree that would both reform Ferguson’s deeply troubled government and police force as well as avert a protracted legal battle.

Those hopes fell apart when the full scale of the agreement became public last month. Among its requirements: the Ferguson Police Department would no longer oversee the municipal court, stricter use-of-force policies would be drafted, the city’s most egregiously abused ordinances would be repealed, and a federal monitor would be appointed to ensure compliance.

But other conditions seemed more onerous for a municipality of 21,000 people. Ferguson’s annual budget is $14.5 million and the city is already running multimillion dollar deficits, but local officials estimate it will cost $3.7 million a year to carry out the agreement over the next three to five years. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, $1.9 million of that will go toward salary increases: $900,000 to make Ferguson Police Department salaries among the nation’s “most competitive” to attract better-trained officers, and another $1 million to raise salaries for other city government employees to keep pace.

Another contentious point in the agreement, according to the Post-Dispatch, was a clause that would uphold the reforms even if city officials disbanded the Ferguson Police Department.

One provision in the decree, which the city released to the public two weeks ago, says that all the requirements would apply to any agency that took over policing in Ferguson. By removing that stipulation, Ferguson could disband its police force and sidestep a large part of the agreement.

In an interview after the meeting, Councilman Wesley Bell acknowledged the change was significant, but said the tight deadline under which the city was operating left Ferguson little choice but to ask the provision be removed.

“If we get to the point where we have to disband our police department, which honestly I don’t see happening, but let’s say it does happen, no department is going to take us on with those conditions without charging twice as much,” Bell said. “It’s not a ‘no’ on the provision. It’s, ‘Let’s talk about the provision. Let’s figure out something we can all live with that actually makes sense.’”

In their vote Tuesday, Ferguson’s seven-member city council unanimously approved seven changes to the drafted agreement, including the removal of the “most competitive” requirement and the disbanding provision. City lawyers warned that the vote would almost certainly guarantee a federal lawsuit in retaliation. The Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division followed through within 24 hours.

For Ferguson, a victory in the courts is unlikely. The Justice Department has launched 67 investigations since Congress empowered it to sue police departments for civil-rights violations in 1994 after the Rodney King beating, according to the Washington Post. Of those, 66 led to consent decrees for the departments targeted—and Justice Department lawyers are appealing a lower-court defeat to obtain the 67th one.

February 10, 2016

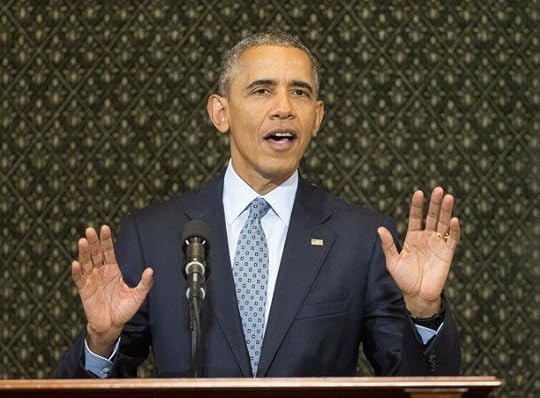

A Frustrated Obama Returns to the 'Politics of Hope'

There was a moment in the middle of President Obama’s address to the Illinois state legislature on Wednesday when a look of fear briefly came over his face.

Speaking to lawmakers with whom he used to serve, the president had been waxing nostalgic about his time as a state senator. Legislating in Springfield, as Obama described it, was nothing like the polarized Washington swamp. Sure, there was plenty of disagreement in Illinois, and the two parties debated the issues vigorously. But the political fights were civil. Republicans and Democrats played poker with each other, enjoyed rounds of golf together. They socialized. They didn’t call each other “idiots” or “fascists,” he said, “because then we would have to explain why we were playing poker with an idiot or a fascist who was trying to destroy America.”

In the White House, Obama’s inability to change politics has become his greatest failure and, as he has conceded repeatedly, “one of my biggest regrets.” He had not, he told some of his former colleagues in Springfield, been able to close “the yawning gap between the magnitude of our challenges and the smallness of our politics.”

But everything was different in Illinois—or at least that’s how the president had remembered it when he left over a decade ago. Because as Obama was claiming credit for what he had accomplished in spite of all the partisan rancor, he saw that only the Democrats in the Illinois general assembly chamber were standing to applaud. The legislature was cleaving along party lines before his eyes, just like Congress does every year when he speaks in the Capitol.

At first Obama smirked. “See, I didn’t want this to be a State of the Union speech where we have the standing up and the sitting down,” he interjected, drawing chuckles from the lawmakers. “C’mon guys, you know better than that,” he joked, pointing at his Democratic friends.

But then instead of quieting down, the applause from Democrats grew louder, and cheers erupted. Now Obama was annoyed, and he looked momentarily afraid that he was losing control of the crowd. He put his hands up. “I’ve got a serious point to make here,” the president said. “I’ve got a serious point to make here, because this is part of the issue.”

The members in the Illinois legislature were proving Obama’s point, and not in the way he wanted.

“I’ve got a serious point to make here,” the president said. “I’ve got a serious point to make here, because this is part of the issue.”

This was intended as a grand homecoming for the president, coinciding with the ninth anniversary of the speech that launched his campaign for the White House. Joined by his close friends Valerie Jarrett, David Axelrod, and Senator Dick Durbin, Obama’s speech to the lawmakers and then a second one to supporters was part of a yearlong farewell tour of sorts that began with his State of the Union address. In returning to Springfield, the president was also returning to the place that had inspired his “politics of hope” message.

He began his speech with inside jokes and friendly call-outs to members of both parties before turning to his assessment of politics in America. The address lasted over an hour, but by the end Obama had mostly said a lot of things he’s said in interviews, speeches, and press conferences throughout his tenure. He called for reducing “the corrosive influence of money in politics”; an end to gerrymandered congressional districts; same-day and automatic voter registration laws that make it easier, not harder, for citizens to cast ballots; and a greater commitment to civility in politics.

Obama made only passing references to the presidential race, but it was hardly a coincidence that his call for civility came a day after the candidate of incivility, Donald Trump, had won a landslide victory in the New Hampshire Republican primary. “We can’t move forward if all we do is tear each other down,” he said. “We should insist on a higher form of discourse in our political life.” There were also lines that could have resonance in the Democratic race, as when Obama made a pitch for pragmatism and criticized groups in both parties who condemned compromise and demanded purity from their allies. (In a possible dig at Bernie Sanders, he knocked not only “union bashing” but also “corporate bashing.”) “That kind of politics means that the supporters will be perennially disappointed,” the president said. “It only adds to folks’ sense that the system is rigged. It’s one of the reasons why we see these big electoral swings every few years. It’s why people are so cynical.”

Obama’s remarks drew kudos from government-reform advocates but a much harsher response from Republicans. “President Obama is uniquely unqualified to deliver this message and the Illinois legislature is uniquely unqualified to play host to a speech on bipartisanship,” complained Representative Peter Roskam, an Illinois Republican in Congress who served alongside Obama in the state Senate. “One thing in particular I’ve noticed about the president is his utter incapacity to be reflective about the weaknesses of his worldview.”

Yet the most interesting dynamic in Obama’s speech was his continued frustration that the politicians he was addressing—these friends he was holding up as exemplars!—kept acting like politicians. He chastised the Republicans for cheering his call for gerrymandering reform in a state whose districts have been drawn by Democrats. And he tried in vain to stop Democrats from acting as his partisan cheerleaders. “Sit down, Democrats!” he snapped playfully at one point, sounding like a teacher scolding students he had riled up in the first place.

It was all a little too symbolic at points, a president’s futile effort to keep a bunch of rowdy legislators in line. “One thing I’ve learned is that folks don’t change!” Obama ad-libbed when the lawmakers wouldn’t quiet down. In the moment, he was speaking of his former colleagues in Illinois, but it’s a sentiment the frustrated president could easily apply far more broadly than that.

When Computers Started Beating Chess Champions

There was a time, not long ago, when computers—mere assemblages of silicon and wire and plastic that can fly planes, drive cars, translate languages, and keep failing hearts beating—could really, truly still surprise us.

One such moment came on February 10, 1996, at a convention center in Philadelphia. Two chess players met for the first of six tournament matches. Garry Kasparov, the Soviet grandmaster, was the World Chess champion, famous for his aggressive and uncompromising style of play. Deep Blue was a 6-foot-5-inch, 2,800-pound supercomputer designed by a team of IBM scientists.

“There was no way that this tin box was going to defeat a reigning world champion,” says Maurice Ashley, an American grand chessmaster who provided live commentary for the game that day.

Kasparov thought so, too. He’d previously scoffed at the suggestion that a chess-playing computer might defeat a grandmaster before the year 2000, which, back then, probably seemed pretty ridiculous to most people. Personal computers were just over a decade old, and looked liked this. Commercial companies had begun providing Internet access to the general public just the year before. Chess required guile, wit, and foresight—distinctly human traits— and a hunk of hardware, the chess community thought, could not replicate all that—at least not well enough to beat Kasparov.

But the tin box won that game, becoming the first computer to defeat a sitting world chess champion.

Chess players and computer scientists alike were stunned. Computers were by then known for doing some things better than humans could, like solving complex math problems or processing employees’ paychecks. “But everybody knew that chess required intelligence to play well, so to see that a computer could do this and compete with the best player in the world—that was sort of a wakeup call,” says Murray Campbell, one of the IBM computer scientists who developed Deep Blue, and a competitive chess player himself. “It was a sign that a lot more was coming.”

The concept of chess-playing machines dates back centuries. One of the first iterations was rather dishonest: an automaton created by Wolfgang von Kempelen, a Hungarian inventor, in the 1760s only managed to win because the human player hidden inside was pulling levers to move pieces across the board. It took humans until the 1950s to program machines to observe the rules of chess. By the 1980s, computers could conduct basic searches of potential moves and strategies, but at considerably quick speeds, searching several thousands positions per second. They started competing against skilled human players—and winning. In 1987, Deep Thought, the precursor to Deep Blue, defeated British chessmaster David Levy.

“Deep Thought sees far but notices little, remembers everything but learns nothing, neither erring egregiously nor rising above its normal strength,” the IBM scientists wrote in 1990. “Even so, it sometimes produces insights that are overlooked by even top grandmasters.”

Deep Blue was considerably more advanced. At its core, the computer was built to solve complex numerical problems. In front of a chess board, Deep Blue, equipped with data from hundreds of existing master games, would scan the board for features it recognized. Like a human player, the computer thought ahead, exploring potential moves in terms of sequences, envisioning future positions. It numerically rated the moves as it went, finally making the one that came out with the highest rating—the “best” move. Deep Blue was capable of evaluating 100 million positions per second.

Kasparov went into the historic game in 1996 feeling confident, but it soon became clear Deep Blue was a tougher competitor than he’d expected. Kasparov, already known for being an animated player, was visibly frustrated during the game, often shaking his head, says Jeffrey Popyack, a computer science professor at Drexel University who was in the room. At one point, Kasparov spent 27 minutes deliberating before moving his queen. “The thing that really sticks with me now was just the anguish that Kasparov was going through,” Popyack recalls.

Toward the end of game, Kasparov and Deep Blue were like “two sumo wrestlers battling one another at the edge of a high cliff,” as Monty Newborn, chairman of the computer chess committee for the Association of Computing Machines, once put it. Kasparov was mounting an aggressive attack on Deep Blue’s king when the machine made an unusual move—going after a pawn across the board—that suggested the machine was unaware it was in trouble. (“It would be kind of like your house was burning down and you decided to go grocery shopping,” Ashley, the American grandmaster, said.) Turns out the computer had calculated that Kasparov’s move—a bold bluff that would have intimidated a human player—wasn’t going to work. The world champion, visibly distraught, resigned a few moves later.

Modern, game-playing artificial intelligence is, well, even scarier. In 2011, Watson, an IBM super computer capable of answering open-ended questions posed in human language defeated Ken Jennings on Jeopardy! Last month, a computing system developed by Google researchers bested the top human player of Go, a complex 2,500-year-old game that depends heavily on intuition and strategy. (Popyack points out that, despite all that, computers are still not very good at programming other computers.)

Human players are successful if they can spot their opponents’ blind spots, and supercomputers are built to find even the smallest of errors and exploit them. “It’s never going to get tired, and it’s never going to get overconfident, and it’s just going to kill you,” Ashley said. “That’s the difference now. It’s like playing the Terminator.”

Kasparov rebounded in the second game against Deep Blue, and went on to win the whole six-game series. But the scales had been tipped. And in a subsequent matchup in 1997, Deep Blue triumphed. Humans were no longer winning the battle between man and machine.

“It’s a really dangerous business to say, ‘computers will never,’ and then say something after that,” Campbell says.

Have the Coen Brothers Made Peace With Hollywood?

The main character in Hail, Caesar!, Eddie Mannix (played by Josh Brolin), is the only one who’s named for a real-life Hollywood figure: a notorious “fixer” who bullied movie stars into behaving themselves and kept their dirty secrets out of the press. Throughout the film, the heavily fictionalized Mannix runs into crisis after crisis and ponders whether he should quit the movie business all together. Despite his job title, he doesn’t actually fix many problems—most of them end up being resolved with goofy serendipity in one way or another.

Related Story

Hail, Caesar!: A Confection of Old Hollywood

DeeAnna Moran (Scarlett Johansson), an actress pregnant out of wedlock, is told to secretly give her baby to a studio agent (Jonah Hill) so that she can adopt it back from him in what seems a charitable move; instead, the two fall in love. Mannix is pestered by twin gossip columnists (both Tilda Swinton) who have a story of a star’s sexual shenanigans, but it falls apart when the source is revealed to be a communist. Mannix’s wife even asks him to call his son’s baseball coach because he doesn’t want to play shortstop; later he learns his son took the field without a fuss. “Took care of itself,” Mannix murmurs with satisfaction.

But there’s one issue he tackles decisively. Near the end of the film, the leading man Baird Whitlock (George Clooney), having been kidnapped by communists for a day, starts ranting about the evils of capitalism and the studio’s complicity in deceiving the working man. Mannix slaps him and tells him to get back to work: “The picture has worth, and you have worth if you serve the picture, and you’re never gonna forget that again.” It’s an ironic note of optimism from the Coens, but optimism nonetheless—a wry celebration of the movie system they’ve become a part of, and one that stands in fascinating contrast to their earlier, surreal Hollywood satire, Barton Fink.

In 1991, when Barton Fink was released, the Coens were still fairly new to the industry. They broke onto the scene with the indie critical hit Blood Simple in 1984 before making the small-budget Raising Arizona (1987) and the grander Miller’s Crossing (1990). The latter, a prohibition-era gangland yarn, frustrated them so much during the scripting process that it inspired Barton Fink, a film about having writer’s block. As with all their films, the Coens insist Fink isn’t remotely autobiographical. But even so, it paints a nightmarish picture of 1940s Hollywood as a town where the producers and studio heads are ranting egomaniacs, the writers are drunken, broken-down fools, and the L.A. hotel the action is set in literally resembles hell. The only similarity to Hail, Caesar!? They’re both about the same fictional company: Capitol Pictures.

In Barton Fink, the title character (John Turturro) is a playwright looking to bring his work to the masses: a Clifford Odets-type ready to be exploited when he’s put under contract by a major studio. Seeking to connect with the common man as he writes a wrestling movie for Capitol, he stays at a dumpy hotel where the wallpaper is peeling and there’s only one other visible resident, a garrulous man named Charlie Meadows (John Goodman). Meadows eventually turns out to be some sort of personification of the devil himself, a shotgun-wielding lunatic who makes the hallways spontaneously combust with his rage.

It’s my favorite Coen Brothers film, and one of their most divisive—partly because its deeper meanings are so obscure. It’s very clearly a film about creative frustration, but you could argue Hollywood is also a metaphor for something larger, or that Barton Fink is a satire of the studio system itself. While staying at the hotel, Fink is repeatedly attacked by a mosquito—his blood is literally being sucked dry, and his creative efforts on his script are rewarded at the end of the film with a dressing-down by the studio chief, who wanted formula and decides to punish Fink by keeping him under contract but publishing none of his work.

For the Coens, Hail, Caesar! is a wry celebration of the movie system they’ve become a part of.

Hail, Caesar! is preoccupied with larger issues too—it’s set in the early ’50s, as the studio system began to falter and lose its stranglehold on big stars. Mannix is a sort of grand mechanic for this sputtering Hollywood machine, walking onto lot after lot to try and solve everything that goes wrong. In the process, he (and the viewers) get to behold one dazzling spectacle after another, from an aquatic musical number fronted by Scarlett Johansson, to a Gene Kelly-esque dance sequence from Channing Tatum, to an athletic Western action sequence from Alden Ehrenreich. While Barton Fink offered only brief, mocking clips of other films about wrestling, Hail, Caesar! serves up a cornucopia of delights.

At the end of Barton Fink, the hero is enslaved to the studio system, and though his fate is uncertain, he seems to have tapped new creative potential. The nebbish Fink bears a distant resemblance to the disgruntled screenwriters who kidnap Whitlock in Hail, Caesar! and lecture him about the means of production and his diminished value within the capitalist machine. The Coens clearly have sympathy and affection for their fictional writerly brethren, but they’re still as pathetic as the woolly-brained Whitlock (the kidnappers try to donate the ransom to the Soviet Union to advance the “cause”). As in many Coen brothers films, there’s a certain fatalism at work here.

The difference is not in the message but in the tone. Films like Barton Fink, or A Serious Man, or Inside Llewyn Davis see their protagonists seeking creative fulfillment or asking questions of higher powers—and receiving no answer. In Hail, Caesar! the answer is given, and it’s as hopeful as one could expect from the Coens: Cinema’s somber, weighty moments matter, but equally crucial are the frivolous, joyful bits of entertainment—watching Channing Tatum tap-dance on a table, or George Clooney ramble overwritten monologues. It bears repeating, one last time: The picture has worth.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower