Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 230

February 16, 2016

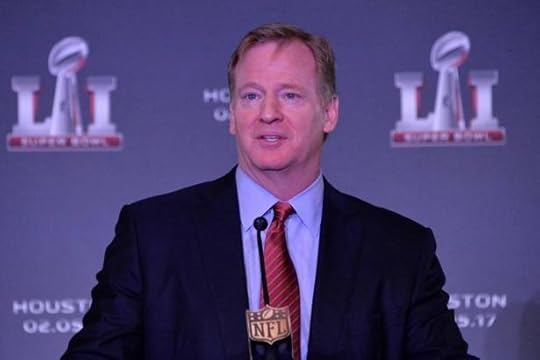

Roger Goodell's $34 Million Salary

By most accounts, 2014 was a particularly bad year for professional football.

Star NFL players, including Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson, were embroiled in very ugly and very high-profile domestic-abuse scandals. The president was calling the game unsafe while Congress was lobbying to get the league stripped of its status as a nonprofit. Former players were challenging a class-action settlement over the effects of concussions and a public campaign to rename of the league’s most storied teams became a cultural touchpoint.

Nevertheless, according to documents released Tuesday, Roger Goodell, the NFL commissioner, made $34.1 million in compensation in 2014, a year in which editorial boards of large newspapers and advocacy groups were calling for his ouster.

As ESPN reported, here’s how that figure breaks down:

Goodell had a $3.5 million base salary, but he also received a bonus of $26.5 million, a figure that was determined in 2013. In addition, he received $3.7 million in pension and other deferred benefits and $273,000 in “other reportable compensation.”

Goodall’s 2014 haul is slightly less than his 2013 salary ($35 million) and considerably less than his 2012 salary ($44 million), the latter of which included millions in deferred money. In his nine years as commish, Goodell has now raked in just over $180 million.

There are a number of different ways to look at these figures. Goodell’s salaries are much higher than any of the NFL’s highest-paid players. As Bloomberg points out, Goodall’s 2014 salary is higher than that of all but 61 CEOs of public companies.

Over at The New York Times, Ken Belson suggests that relative to the NFL’s revenue, Goodell makes a comparable salary to the heads of pro basketball and baseball. The key difference is that professional football has been the most popular sport in the United States for three decades running. Goodell, though he may be personally very unpopular among fans (and certainly among players), serves as a useful punching bag for a league that is beloved and pulled in $11 billion in revenue in 2014.

Kevin Seifert of NFL Nation makes the point that part of why Goodell is making so much money, especially over the past four years, is because the owners who determine his bonuses are making so much money:

What we've seen is a CEO paid for delivering significant revenue growth -- or, at least being in charge when it happened -- over a relatively short period of time. It's a continuation of the owners' delight with their 2011 collective bargaining agreement (CBA), an agreement that has helped their revenue soar.

In 2015, the NFL formally became a for-profit organization, which means that Goodell’s salaries going forward will remain private. And while he may be maligned, until pro football’s myriad image problems actually cut into the league’s record revenue, it’s hard to believe the commish or his salaries will truly fall.

Antonin Scalia's Secrets

Supreme Court justices seldom publish memoirs. But to judge by the never-before-told stories that have come out about Antonin Scalia in the days since his death, his autobiography would have been as compelling as the justice himself.

Vice President Scalia?

The most surprising tale came from former House Speaker John Boehner, who emerged from his post-resignation hibernation to reveal that in 1996, he met with Scalia about the possibility that Bob Dole would choose him as his vice-presidential running mate. Boehner was then the fourth-ranking member of the House Republican leadership, and as he writes in the Independent Journal Review, Scalia agreed to meet for a “clandestine” lunch with Boehner and his chief of staff, Barry Jackson.

It was there that Jackson and I made our pitch, over a pepperoni and anchovies pizza.

Scalia’s reaction was a mixture of amusement and humility, tempered by an underlying seriousness of purpose that reflected his love of country and sense of obligation to it. He asked very direct questions on both the practicality of running — including how a candidacy would impact his role on the Court, what Dole’s reaction would be if he were to express willingness and, ironically, what the impact on the political process might be of a vacancy appearing on the Court in the months before a presidential election.

Scalia was not a man who harbored any thoughts of seeking elective office, which intensified his appeal. But in spite of his personal misgivings, he also understood what was at stake for the country, and felt compelled to listen, out of a sense of duty.

And it was perhaps out of that same sense of duty that Scalia, while not saying “yes,” also didn’t say “no.”

Scalia was already a conservative favorite in 1996 after 10 years on the court, and he certainly would have been an out-of-the-box pick for Dole, who was facing a difficult fight to unseat President Bill Clinton. But the choice would have been incredibly risky for reasons having little to do with the presidency. The Supreme Court back then was nearly as closely divided as it is now, and if Scalia had stepped down from the Supreme Court to run and Clinton still won, Republicans would have lost not only the presidential election but also a reliably conservative seat on the bench.

An Unsolicited Recommendation

Fast-forward to 2009, when President Obama was faced with a vacancy on the Supreme Court just a few months into his term following the retirement of Justice David Souter. At the annual White House Correspondents Association dinner, Scalia was seated alongside David Axelrod, one of the president’s closest advisers. In a piece published on CNN.com on Sunday, Axelrod wrote that Scalia took the opportunity to weigh in on the appointment. “I have no illusions that your man will nominate someone who shares my orientation,” the justice told him. “But I hope he sends us someone smart.”

After Axelrod says he replied with a rather bland formality, Scalia pressed on.

“Let me put a finer point on it,” the justice said, in a lower, purposeful tone of voice, his eyes fixed on mine. “I hope he sends us Elena Kagan.”

Obama did send Kagan to the high court, but not in 2009. Having just installed the Harvard Law School dean as his solicitor general, the president nominated Sonia Sotomayor to replace Souter. He made Kagan his pick a year later to succeed the retiring Justice John Paul Stevens. Axelrod didn’t say whether Scalia’s recommendation had any influence on the president.

Scalia’s push for Kagan is more interesting in light of a complaint about the high court’s lack of geographic and religious diversity that he made years later in his dissent on the same-sex marriage case, as highlighted by Adam Liptak in The New York Times. Scalia noted that the court was dominated by people from the east and west coasts and lacked any evangelical Christians or even Protestants. Kagan, whom he recommended, was a Harvard-educated Jewish lawyer who was raised in Manhattan. She differed from the other eight justices only in having never previously served as a judge.

He Could Take a Joke

Scalia may not have been a unifying figure on the court politically, but he was universally lauded for his sense of humor. On The Late Show on Monday night, Stephen Colbert shared a story from the time he headlined the White House Correspondents Association dinner in 2006. Colbert’s sharply biting jokes at the expense of President George W. Bush landed with a thud among many of the luminaries in the room. But as he recalled on Monday, Scalia loved when Colbert made fun of him for getting caught making a rude gesture to photographers the week before. “When it was over, no one was even making eye contact with me. The one exception was Antonin Scalia,” Colbert said. The justice, was seen cackling in C-Span's reaction shots, came up to Colbert after the speech laughing. “Great stuff! Great stuff!” he told him before walking away. “I will forever be grateful for that one brief moment of human contact he gave me,” Colbert said before “saluting” Scalia one last time on Monday.

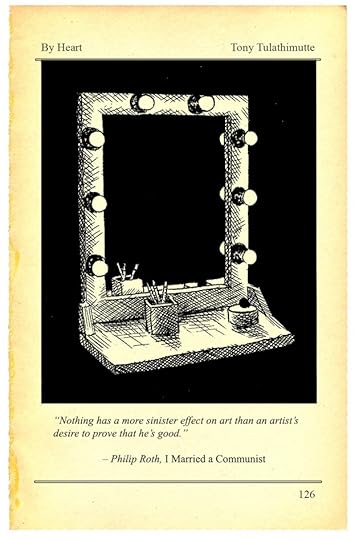

Good People Don't Make Good Characters

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

The debate about whether fictional characters should be sympathetic tends to focus on external pressures—the commercial considerations of “likability” and “relatability,” the fear that readers won’t stick with protagonists they can’t identify with or root for. But Tony Tulathimutte, the author of Private Citizens, points out something less often acknowledged: Writers themselves are expected to play the part of sympathetic, super-perceptive, even heroic human beings. And it’s easier to fulfill that requirement when you’re writing about “good” people.

In his essay for this series, Tulathimutte admits that, as a younger writer, he tried to telegraph his own nobility through generously imagined characters. But Philip Roth’s American Trilogy taught him to distrust the notion that novelists know more, or feel more, or are better people, than anyone else. Taking cues from Roth, Tulathimutte’s learned to write better fiction by fleshing out his characters’ ugly, reprehensible sides—disclosing (and problematizing) his own personal shortcomings in the process.

Private Citizens follows four recent Stanford Grads out of the ivory tower and into the wilds of a Bay Area disfigured by tech companies. Stanford students, we learn, are like ducks: “tranquil on the surface but paddling furiously to keep afloat.” As the characters haplessly pursue various fulfillments—sex, professional dignity, political purpose, venture capital—Tulathimutte’s manic, unsparing, and entertaining narrations reveal the psychic turmoil below each outwardly tranquil surface.

Tony Tulathimutte’s short fiction has won an O. Henry award; his writing has appeared in n+1, VICE, Salon, The New Yorker, AGNI, Threepenny Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other places.

Tony Tulathimutte: In 2008 I was cash flush and loathed myself and everything I’d written. I had a book of short stories that were decently written, but had something queasily embarrassing and juvenile in common: The protagonists were such good people. It wasn’t that they were flawless Mary Sues, but they were possessed of such admirable core qualities that their flaws were eminently forgivable: a fame-hungry bulimic, a hardass father drying out his pillhead son, a figure-skating prodigy who falls on purpose to terminate her secret pregnancy. They would usually be less well-to-do, less educated, less self-aware, in far greater suffering, usually female. Their relative simplicity was rationalized by their youth, and any misbehavior was justified by their hard circumstances. And if the reader still didn’t like them, at least I could avoid being identified with them: They were white.

The effect of these stories was to instill in readers a feeling somewhere between pity and tenderness, a tingling confidence that they were better, kinder people for having spent a time visiting the less fortunate, and by extension, gratitude for an author who really got people different from himself, who you might want to date and publish.

And publish I did! With a few modest tokens of legitimacy in hand, it took some time to accept how much effort I was spending trying to convince people—myself included—that I had the talent and compassion to see the innate humanness in people very different from me. That is, I wanted to prove through my “good” characters that I was good. Inwardly I convinced myself that, by reaching across identity boundaries and beyond my privileges, I was spurning “self-indulgence” and instead striving for depth, warmth, universality, even truth. Yet what’s faker than trying to pass off vanity as compassion?

Even then I was secretly disdainful of this approach, the clear sense that in doing all this admirable empathy-work, the author expects a sugar cookie and a pat on the head. It’s what makes me cringe when I read a comfortable gentile’s grotesque Holocaust fiction, for example—however heartfelt their empathy may be, they’re still co-opting a form of suffering they’ll never be exposed to, and usually getting deafening praise for it.

I wanted to prove through my “good” characters that I was good.

Around then I was starting to read a lot of Philip Roth, America’s literary sovereign for the last quarter century, whom I’d been equally recommended and warned against. I’d enjoyed Goodbye, Columbus and Portnoy’s Complaint, but my appreciation came with a few asterisks—I found his angry smashing of strictures exciting, and his angry performance of white-dude entitlements deeply uncute. I started with his American trilogy, which had been described as a meditation on moral outrage in three eras of American history. It sounded pretty tendentious to me, another laureled white guy out to tell us all what’s wrong with us. But isn’t this what we’ve come to demand and expect of a great writer? Readers of fiction know that they’re not getting anything like the literal truth, yet believe, through some combination of greater learning and deeper living and a dap from God, the author has the inside track to human nature and society, and they’re about to share it with the class.

Roth torches this view early on in American Pastoral, in a cliff of text delivered by his faithful stand-in Nathan Zuckerman:

You fight your superficiality, your shallowness, so as to try to come at people without unreal expectations, without an overload of bias or hope or arrogance … and yet you never fail to get them wrong … You get them wrong before you meet them, while you’re anticipating meeting them; you get them wrong while you’re with them; and then you go home to tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again. Since the same generally goes for them with you, the whole thing is really a dazzling illusion empty of all perception, an astonishing farce of misperception. And yet what are we to do about this terribly significant business of “other people,” which gets bled of the significance we think it has and takes on instead a significance that is ludicrous, so ill-equipped are we all to envision one another’s interior workings and invisible aims? Is everyone to go off and lock the door and sit secluded like the lonely writers do, in a soundproof cell, summoning people out of words and then proposing that these word people are closer to the real thing than the real people that we mangle with our ignorance every day? The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: We’re wrong. Maybe the best thing would be to forget being right or wrong about people and just go along for the ride. But if you can do that—well, lucky you.

I very much appreciate it when a writer makes their own job more difficult, and here, at the outset of a trilogy about a fictional character who writes fictions from the perspectives of other fictional characters, Roth hangs a big warning sign in the foyer more or less proclaiming WE’RE WINGING THIS SHIT, YOU IN?

The sentiment is echoed throughout the second book, I Married a Communist:

Look, there is no way out of this thing. When you loosen yourself from all the obvious delusions—religion, ideology, Communism—you’re still left with the myth of your own goodness. Which is the final delusion.

Nothing has a more sinister effect on art than an artist’s desire to prove that he’s good.

And again in The Human Stain:

There is truth and then again there is truth. For all that the world is full of people who go around believing they’ve got you or your neighbor figured out, there really is no bottom to what is not known. The truth about us is endless. As are the lies.

Why would a narrator, much less a writer, so utterly torpedo his own authority? It was Roth’s way out of the conundrum of fiction, his version of I-can’t-go-on-I’ll-go-on. By acknowledging that truly knowing and empathizing with other people is impossible, he obviates the idea that writing from the vantage of the less fortunate is inherently truer or more noble. And instead of trying to head off speculation about the author through his characters, Roth baits it, even featuring a narrator we can’t help but compare biographically to the author, at high risk of opprobrium.

Such an approach grants the writer a combination of humility and license. It offers a less credulous role for the reader: not to place superstitious trust in an author’s privileged insight, but to appreciate his characters the way one appreciates comedians doing impressions or actors acting—we never believe that they’ve become someone else, but we can admire the dazzling illusion.

Edmund White makes his students write bad characters: “Only once they break the good barrier do these young writers begin to understand the possibilities of fiction.” Zadie Smith warns that you can not only fail to tell the truth, but get away with it, fooling critics and yourself, and that “though we rarely say it publicly, we know that our fictions are not as disconnected from our selves as you like to imagine and we like to pretend.” For Smith, “writing is always the attempted revelation of this elusive, multifaceted self.”

I set out to write with as much love, empathy, hope, and imagination as hate, spite, pessimism, and self-indulgence.

In adapting Roth’s approach to my writing, I set out some heuristics—my characters would be 1.) exactly as smart as me, 2.) about as privileged, and 3.) freely awful. They’re millennials. Cory is self-righteous, Linda a malicious liar, Henrik a pitiful sad-sack. Then there’s Will, who, as the only Asian protagonist, I expected readers to identify with me. I’d always played it safe by strapping the neutralizing uniform of whiteness onto my characters, fearing that anything unusual an Asian character did would be attributed to their Asianness (and mine). Well, Will is Asian, and he’s a real dick. He surveils and manipulates his girlfriend, is ugly-rich, drinks, binges on porn, and nurtures a self-centered preoccupation with his own oppression that leads him to minimize everyone else’s. On top of that, he embodies just about every Asian male stereotype there is. Like Roth, rather than avoid unflattering comparisons and stereotypes, I booby-trapped them; and the impossibility of constructing an authentic identity was no longer an obstacle, but a subject.

Freedoms are habit-forming. Once I let go of any pretense of knowing other people and any interest in concealing my flaws, I saw at once how my less desirable qualities could be leveraged—that, for instance, being the most judgmental prick on Earth suited me to satire, or that my self-centeredness offered material for farce I could never touch before, because nothing dulls comedy like respectability. I set out to write with as much love, empathy, hope, and imagination as hate, spite, pessimism, and self-indulgence. And so the book got written.

I’m not saying unsavory characters automatically make for good writing; it’s just as easy to go the other way and make Bret Easton Ellis/Chuck Palahniuk shadow puppets (dark, flat, silly). The same usually goes for attempts to look intellectual, radical, manly, “brave” (in the sense of confessional), self-deprecating, hip; in each case, the project is branding, not art. I’m saying that to try to write your characters in such a way as to avoid or shape any comparisons to you, and worse, to call this empathy, is to forfeit the honesty that readers deserve in lieu of truth.

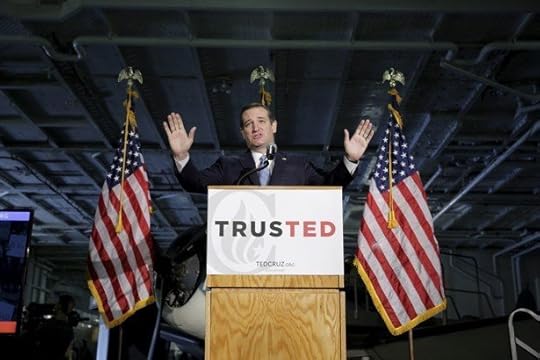

Ted Cruz's Hugely Expensive Plan for a Huge Military

MOUNT PLEASANT, S.C—If it’s the South Carolina Republican primary, it’s time to talk about the military, which is why Ted Cruz was on the USS Yorktown Tuesday, campaigning with Rick Perry and laying out his plans.

The Palmetto State has a high proportion of veterans and military families, especially compared to other states, making it a natural place to talk defense. During a rally on Tuesday, for example, Jeb Bush emphasized military readiness and reforming the Department of Veterans Affairs. But for Cruz, the issue is more pressing, because he’s already facing attacks for some of his votes on national security.

Related Story

And so on Tuesday, Cruz laid out his plan for the military—a massive program of spending, expansion, and innovation, leavened with a healthy dose of Obama-bashing and promises to subordinate civilian bureaucrats to military leaders. It was a plan that seemed aimed at guaranteeing that no one could call Cruz soft of defense, and that would prevent any rival from outflanking him on the right. Whether Cruz’s plan is fiscally reasonable or proportional to threats to the U.S., however, is a different question.

“For the past seven years, our nation has had a commander in chief who questions the value of American strength and denies our exceptional history,” Cruz said. “Instead he eagerly negotiates with terrorists and makes concessions to our enemies.”

Cruz promised to reverse Obama’s policies. He vowed not to constrain the military with political correctness, said he wouldn’t force women to register for selective service, and promised to grant the Marines an exemption from putting women into combat positions. (There was also a somewhat peculiar complaint about “gluten-free MREs.”) Cruz got the biggest applause when, in reference to the detention of American sailors in Iran, he said, “Starting next year, our sailors won’t be on their knees with their hands on their heads.”

But the heart of the plan was the promise of more, bigger, and better. He deplored Obama-era reductions in force, but didn’t simply call for their reversal. “We can’t just pour vast sums back into the Pentagon,” Cruz said. “We need to make generational investments in our defenses that will keep not only us but our children and grandchildren safe.”

Cruz said he would cancel President Obama’s plan to shrink the Army to 450,000 by 2018, and he said the nation needs a minimum force of 525,000 soldiers. He promised to increase the Navy from its current 273 ships to 350, the largest fleet in recent memory. He wants 12 new ballistic-missile submarines. He wants to increase the Air Force by nearly 20 percent, from around 5,000 planes now to 6,000. Mentioning the increasing centrality of drones to American military operations, he said the force of drone pilots needs to grow. He vowed to expand missile-defense systems, improve cyberwar defenses, and protect American assets in space.

In short, Cruz wants to spend a tremendous amount of money.

Cruz didn’t put a price tag on his plan, though he acknowledged it would not be cheap. He offered a variety of partial answers to the money question. “If you think it’s too expensive to defend this nation, try not defending it,” he said. He promised to audit the Pentagon and root out waste, fraud, and abuse, an idea with bipartisan appeal. (He claimed the Department of Defense has 12,000 accountants.) And he trumpeted his plan to cut $500 billion in federal spending over a decade.

“We will not go picking fights around the globe. The purpose of this rebuilt military is not to engage in every conflict.”

But the much-derided F-35 program—which Cruz did not mention on Tuesday—has already cost an estimated $1.5 trillion, as James Fallows has reported. How could Cruz possibly make his plan feasible? For that, there was some handwaving and some posturing.

“We can look to President Reagan as an example,” Cruz said. “He began with tax reform and regulatory reform that unleashed the engine of free enterprise. His policies brought booming economic growth, and that growth fueled building the military. That growth first bankrupted and then defeated the Soviet Union.”

There are a couple problems with that analogy. For one thing, Reagan’s military approach wasn’t especially fiscally conservative: He tripled the national deficit during his tenure. For another, the threat that the U.S. faces now is very different from the threat that Reagan faced. The Soviet Union was a huge, clunky behemoth that required massive spending. Cruz is not unaware of the threat of ISIS and other radical Islamist groups. He talked about them at length, and some of the most sustained applause came when he promised not to accept refugees who might have been “infiltrated” by ISIS. But it’s not clear how the Reagan plan would apply. Although ISIS has found itself cutting salaries as the price of oil plunges, it doesn’t appear that cash flow is the group’s main problem. Wouldn’t the U.S. end up bankrupt long before ISIS went broke?

Cruz’s plan for defeating ISIS has come in for criticism before. He has repeatedly demanded that the U.S. “carpet bomb” the group, a tactic military experts say makes no sense at all. On Tuesday, he said he would attack the group with overwhelming air power, by empowering Kurdish fighters, and by encouraging the Israeli and Jordanian militaries.

The magnitude of Cruz’s spending plan for the military is particularly striking because he has voted to slow defense spending in the Senate, but also because he is one of the less hawkish of the Republican candidates for president. Sure, he talks about how he would never apologize to Iran, but Cruz has tended to oppose intervention. He’s working to thread a needle: both appealing to voters who are upset about costly and unsuccessful interventions during the George W. Bush and Obama administrations, and also resisting attacks from more bellicose rivals like Marco Rubio, who have sought to label Cruz an isolationist.

On Tuesday, Cruz said that the “Obama-Clinton foreign policy” had shown the danger of what happens when the U.S. withdraws from the world, citing a wide range of different attacks as evidence of the danger of isolationism: Major Nidal Hassan’s shooting rampage at Fort Hood; the Sony hack; and the San Bernardino attacks. Yet he also blasted the American involvement in Libya as foolish and irresponsible. For Cruz, the answer is to project strength.

“We will not go picking fights around the globe,” he said. “The purpose of this rebuilt military is not to engage in every conflict, or to participate in expensive and time-consuming acts of nation building.”

Will Cruz’s message of spending huge sums to project strength and avoid conflict sway Republican voters? Cruz is second in RealClearPolitics’ average of the race, but he lags far behind the frontrunner. (The 200 people in attendance also lagged behind Trump’s own huge December rally on the Yorktown.) A poll released Monday found Cruz with a negative favorability rating. Even among enthusiastic Cruz backers on board the Yorktown, there was some wariness about his chances on Saturday.

“There is a mystifying level of support for Trump,” worried Bob Armstrong, who was sporting a red, white, and blue Cruz jersey ( number 45, for the prospective 45th president ). “I haven’t met any Trump supporters!” Just a couple rows away, Joseph Laudati told me was deciding between Trump and Cruz, though: “I like the outsiders.” He had once been a hardcore Trump backer, but he was starting to be turned off by the frontrunner’s rhetoric. Cruz will need to peel off a lot more people like him to get a win on Saturday.

Deconstructing Kendrick Lamar's Grammys Performance

Kendrick Lamar’s performance at the Grammys has been widely described as “fiery”—a nice way to say there were pyrotechnics both of the actual and emotional sort. But there was more than fire, too. The set was obviously political; it was obviously powerful. What exactly did it say?

Lamar arrived bound to other mock-inmates, slouchily walking with a hint of rhythm: every few beats, a twitch. This was clearly an image for the age of mass black incarceration. From the jail cells, jazz players noodled softly, queasily. Lamar put his chained hands over the mic and said “I’m the biggest hypocrite of 2015,” the first words of “Blacker the Berry.” The rhythm section suddenly stabbed in—bam, bam—and Lamar flinched before launching into another line.

When it was released last winter, “Blacker the Berry” sparked controversy because Lamar’s narrator berated himself for mourning Trayvon Martin while also participating in violence against black people. Some critics saw the narrative as an example of respectability politics, the ideology that lectures black people and blames their behavior for intractable, historically rooted problems. Others saw it as an artful dissection of how an oppressive society can divide a persons’s loyalties and create self-loathing. At the Grammys, Lamar didn’t let the song’s full logic develop. He only performed the first verse, the one where the narrator is in full righteous-fury mode, drawing power from his heritage to confront white America: “You hate me don’t you? You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture. You’re fuckin’ evil, I want you to recognize that I’m a proud monkey.”

The music picked up, its stutter morphing into a groove. The chains came off the prisoners, who started hunching, jumping, dancing. Lights dimmed. Day-glo patterns lit up what had been prison uniforms. All assembled rocked out. Then the music changed: bongos, sax, lively but smooth. Lamar headed stage right, staggering, as if in a daze. He had just rapped “I’m African American, I’m African / I’m black as the moon, heritage of a small village”; it now appeared he had been transported to that village, perhaps in a dream.

He’s calling for a “conversation for the entire nation,” illuminated by a fire that has been roaring for longer than America has existed.

As a massive bonfire blazed and people drummed and danced, Lamar performed the beginning of “Alright,” a rallying song for the Black Lives Matter movement. A lot of attention has gone to the chorus’s affirmations, but those affirmations matter because of the verses, which talk about the special allure money and sex have when exploitation and violence are facts of life. The image of a roaring African celebration is an image of joy outside of the tangle of American problems and slippery solutions Lamar’s lyrics describe. But all images of fire have duality—destruction and creation, war and life. Here, viewers may have thought of riots or bombings in America’s past. Notably, Lamar skipped the line, “We hate po-po,” though that may not be enough to dissuade some folks on Fox News from misconstruing the whole thing as “anti-police.”

For act three, the on-stage crowd fell away and Lamar performed a new song. “It’s been a week already / feeling weak already,” he began, and a few bars later he mentioned February 26, 2012, when Trayvon Martin was killed. On that day, Lamar said, “I lost my life too … [it] set us back another 400 years.” His narrator sank into anger, shame, and indignation at the larger system and at the particular situation of an unarmed black boy losing his life. “Why didn’t he defend himself? Why couldn’t he throw a punch?” he asked.

The music accelerated, becoming noisier, and Lamar started gesturing and rapping more furiously. The lyrical scene pivoted: All of the aforementioned turmoil is why “I’m by your house, you threw your briefcase on your couch.” He seems to be talking about a break-in. What follows might be a power/revenge fantasy, or a confession, or a description of getting your own in a violent world:

I plan on creeping through your damn door and blowing out

Every piece of your brain

'Til your spine drip to your arm

Cut off the engine then sped off in a Wraith

Lamar pivoted again—“I’m on the path with my bible”—before asking himself a series of questions about how to use his fame. His words were coming fast; you’ll have to read them online to understand. He talked about anxiety, struggles with sobriety, and a tentative relationship with religion. He talked about drinking by himself in the park, and then returned to the image of blowing someone’s brains out and speeding off in a car. The music reached a chaotic crescendo as the camera flipped back and forth between different angles on Lamar’s face.

Before the song cut out and an image of Africa with the word “Compton” on it appeared, Lamar ended with this:

I said Hiiipower, one time you see it

Hiiipower, two times, you see it

Hiiipower, two times you see it

Conversation for the entire nation this is bigger than us

“Hiiipower” is the name of a 2011 song by Lamar, but he has explained the term is a slogan for a larger movement: “The three i’s represent heart, honor and respect. That’s how we carry ourselves in the streets, and just in the world, period. Hiiipower, it basically is the simplest form of representing just being above all the madness, all the bullshit.”

This is a political message, but before that it’s a therapeutic message, one about psychology and behavior. It is, as is often the case with Lamar, about the inner struggle forced by outer struggles. The Grammys performance began with Lamar in bondage, escaping into righteous celebration, and then returning to the messy reality that troubles his psyche. It’s all in his head, but it’s also very clearly not. Lamar doesn’t say that through “heart, honor, and respect” alone injustice will be solved. He’s calling for a “conversation for the entire nation,” illuminated by a fire that has been roaring for longer than America has existed.

Remembering Boutros Boutros-Ghali

There are many reasons why Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the Egyptian diplomat and former UN secretary-general, appears in the annals of 20th-century history.

First, Boutros-Ghali, who died on Tuesday at 93, grew up in one of Egypt’s most prominent Coptic Christian families and was the grandson of Boutros Ghali, the Egyptian prime minister, who was assassinated in 1910. His father, Yusef, served as the country’s finance minister.

Later, as an ascendent member of Egypt’s diplomatic class, he garnered seemingly countless academic degrees, including a Ph.D. in international law from the University of Paris, and directed the Centre of Research of the Hague Academy of International Law. He was also a Fulbright scholar, wrote a dozen books and hundreds of scholarly pieces in prestigious journals, and taught law at the University of Cairo.

In 1977, Boutros-Ghali joined Egyptian President Anwar Sadat as a leader of Egypt’s groundbreaking delegation to Israel; he had been named acting foreign minister after Sadat’s previous chief diplomat resigned in protest against the overture to Israel. Two years later, Boutros-Ghali was present at the White House when Israel and Egypt, which had fought four wars in 30 years, signed their monumental peace agreement. The two heads of state were later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Following Sadat’s assassination, Boutros-Ghali continued to serve in high leadership positions in the country over the next 15 years, including as deputy prime minister and secretary of state. Eventually, he was elected secretary-general of the United Nations, the first African and Arab to hold the post.

Taking over the UN’s top position in the sanguine days following the end of the Cold War, Boutros-Ghali’s tenure was marred by the failed international efforts to stop the Rwandan and Bosnian genocides and the fighting in Somalia. He increasingly clashed with the lead diplomats and administrations in Washington, D.C., and London and, after he was replaced by Kofi Annan, he became the only secretary-general to only serve one term.

Affable and charismatic, Boutros-Ghali also became a cultural fixture, name-checked in Seinfeld, and a capable participant in an extremely memorable interview about world diplomacy with Ali G, Sacha Baron Cohen’s alter ego.

Perhaps more than anything, Boutros-Ghali is a reminder of a time when Egypt, the world’s most populous Arab country, was a vital force in the Middle East. In the wake of the Arab Spring, a Coptic Christian (and one married to a Jewish woman) would stand little chance of playing a leading role in a country and a region beset by religious and political strife.

The UN Security Council was the first to announce Boutros-Ghali’s death on Tuesday. The council held a moment of silence before entering discussion on the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Yemen.

Cuba and the U.S.: An Ongoing Thaw

Cuba and the U.S. are quickly becoming best––or at least better—friends. This week alone has seen the re-establishment of commercial flights, the approval of the first American factory to be built on the island since Fidel Castro took power in 1959, as well the return of a misplaced American missile.

On Tuesday, U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx flew to Havana and signed an agreement with Cuban officials that allows American airlines to compete for up to 110 flight routes per day. It was the latest step toward normalizing relations since Barack Obama and Raul Castro made their historic announcements in 2014 to restore ties.

The flight agreement would give commercial carriers 15 days to submit an application to the Transportation Department outlining the routes and destinations they’d like to fly to. It would allow carriers like American Airlines, JetBlue, Southwest Airlines, and Delta Air Lines––all of which have expressed interest––to bid for 20 daily flights to Havana, and 10 to each of Cuba’s other nine international airports.

Soon after Obama announced the thaw in relations between the U.S. and Cuba in 2014, American tourism to the island jumped. Last year, some 160,000 American tourists flew to the island, the Associated Press reported—a 77 percent increase over the previous year. That number doesn’t include the hundreds of thousands Cuban Americans allowed to visit family. Previously, flights to the country were restricted to around a dozen charter companies. Travel is supposed to have been, and still is, only for family visits, reporting trips, educational tours, and professional meetings––though, this seems to be softly enforced.

The agreement, so far, wouldn’t allow the state-run Cuban carrier to fly to the U.S., but might include “leases of aircraft between themselves or with airlines of a third country’s cooperation,” reported Granma, the official newspaper of Cuba’s Communist Party.

The thaw in travel should help Cuba’s economy. The island has been cut off from American dollars for half a century—though it does have trade relations with Europe and Canada. Still, U.S.-Cuban business relations had their own historic moment.

On Monday, Obama approved the first American factory to be built in Cuba since 1959. The company, run by two men in Alabama, sells small tractors. Like the rest of the exceptions Obama has created in the embargo, this was done through executive action. The Associated Press reported the Obama administration got around the law because of an exception that allows U.S. companies to export goods that help Cuban farmers. For the first three years, the factory will ship manufactured parts from the U.S. and assemble them in Cuba, with the eventual plan of manufacturing everything on the island. In a show of goodwill, the owners named their new tractor plant, The Oggun, a name taken from the Santeria saint of weapons and iron tools.

Relations between the two longtime rivals have improved so significantly that over the weekend Cuba returned an American missile it’d held onto since 2014. Although the laser-guided Hellfire bomb was not active, it’s loss was seen as a laughable mistake on the part of the U.S., one that “ranks among the worst-known incidents of its kind,” The Wall Street Journal wrote. In what is believed to have been a shipping error, the missile was accidentally sent to Cuba. Officials feared its secrets may have been shared with China or Russia. But for now, they say, they are just thankful to have it back.

What Will Become of Public-Sector Unions Now?

Over his 30 years on the Court, Antonin Scalia’s name became synonymous with conservative jurisprudence, and especially with the school of thought that calls upon judges to seek the original meaning of constitutional provisions. But Scalia’s principles could also lead him to some surprising results: On contentious issues such as whether the First Amendment protects flag burning, whether criminal defendants have a right to confront witnesses against them, and what sorts of police searches are “reasonable,” Scalia would sometimes break ranks with other conservative justices.

For that reason, progressives were pinning their hopes on Scalia to play the role of unlikely savior in one of the term’s most contentious cases: Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association. (While often the swing vote, Justice Kennedy’s comments during oral argument in a similar case two years ago indicated he was likely to vote against the union.) A ruling against the state and union defendants would be a major blow, perhaps the most significant one in a decades-long conservative effort to defund America’s public-sector labor unions by reversing Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, a 1977 decision which held that public-sector employees could be required to pay a so-called fair-share fee to the union that represents them. While no one would call him a great friend of organized labor, Scalia was the most likely swing vote in Friedrichs; Court-watchers saw his prior opinions as an endorsement of the union’s position. But Scalia had also characterized mandatory union fees as an “undeniably unusual” “tax” levied on public employees by private unions in a 2007 case, so his vote was no sure thing.

On the day Friedrichs was argued, those hoping for signs of a union-friendly Scalia left the Court severely disappointed. With his trademark gusto, Scalia tore into core arguments made by the union and government attorneys. Conservative pundits could barely contain their joy, while liberals began editing their obituaries for the American labor movement.

But with news of Scalia’s passing on Saturday, a new question emerged: Assuming Justice Scalia was indeed part of a five-justice majority to hold mandatory union fees unconstitutional, what will become of Friedrichs? There are two possibilities. First, sometime between now and July, the Court could hand down a 4-4 decision. A tie goes to the victor in the lower court, and in this case the union won handily before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which simply applied Abood. Second, the Court could hold the case over for re-argument once a new justice is confirmed. But the Court may be unwilling to leave Friedrichs and other close cases undecided while a confirmation battle plays out—especially because that battle seems to be shaping up to last a year or more.

At minimum, then, Abood is nearly certain to remain good law through the 2016 election. That alone is a victory for public unions, which will not be forced to divert member dues away from political activity in the middle of a presidential-campaign season.

What next for unions? It largely depends on what happens between now and November in the battle over Scalia’s replacement.

If the Court does set Friedrichs for re-argument—or if the issue reaches the Court again in another case, as it is likely to do—then the outcome will all be down to the new Justice. A Justice appointed by a Democrat is much more likely to vote to uphold Abood than one appointed by a Republican, though there are no guarantees. For example, Judge Sri Srinivasan, a likely President Obama nominee, has decided several First Amendment cases during his two and a half years on D.C. Circuit, but none addressing union fees. Still, Srinivasan voted to reject free-speech challenges to commercial-disclosure requirements, as well as against First Amendment protection for a public-school teacher who sent an email criticizing school conditions to Chancellor Michelle Rhee. These votes bode well for public-sector unions, though extrapolating from cases in which appellate judges are bound to apply Supreme Court precedent can be perilous. Conversely, potential Republican nominees, such as former Solicitor General Paul Clement, are more likely to follow in the steps of Justice Samuel Alito, who has been remarkably hostile to public unions.

If Abood stands—either because of a 4-4 decision or because a new Justice provides the fifth vote to affirm it—it will not spell the end of challenges to public-sector unions. Cases with the potential to chip away at organized labor will continue to reach the courts in significant numbers no matter what, and they will proliferate if the next justice is a Republican appointee. More important, states may still adopt “right-to-work” laws banning mandatory union fees, as the West Virginia legislature voted to do last week, or to eliminate collective bargaining for public employees altogether. Thus, a favorable decision in Friedrichs will not eliminate contentious fights over union rights—it will just move them to state governments, which increasingly lean Republican.

At the same time, unions may be left in a stronger position for having been through the Friedrichs crucible, assuming they emerge victorious. First, public unions responded to Friedrichs by redoubling their efforts to connect with represented workers, successfully convincing tens of thousands of them to become members. Those gains, and the infrastructure that facilitated them, will presumably remain in place. Second, blue-state lawmakers had already begun rethinking union rights in a post-Friedrichs world. For example, a Hawaii bill would partially fund collective bargaining through the state, while also allowing unions to experiment with charging non-members à la carte for their services. And, California responded to a 2014 Supreme Court decision eliminating fair-share fees for home health-care workers by giving unions the right to make a presentation at new employees’ mandatory orientation. Similar proposals may yet take hold, even if the Friedrichs threat is eliminated. Especially given that robust union representation is associated with higher pay for public employees, then, one indirect consequence of Friedrichs may turn out to be greater disparities in public-sector wages and working conditions among the states.

So what next for unions? It largely depends on what happens between now and November in the take-no-prisoners battle over Scalia’s replacement. With well-funded, conservative groups filing dozens of constitutional challenges to labor-friendly public-policy regimes, unions have a proverbial Sword of Damocles hanging over them. Replacing Scalia with another conservative justice would almost certainly bring it crashing down. A replacement by Obama, Clinton, or Sanders would likely remove the threat for now, and, depending on who the replacement is, could leave unions with the most labor-friendly Supreme Court since the 1960s.

February 15, 2016

Deadly Strikes Against Civilians in Syria

At least 23 people were killed and dozens injured when missiles hit three hospitals and a school in northern Syria Monday.

At least 14 people were killed in the town of Azaz when missiles struck a children’s hospital and a school that was sheltering people fleeing the attack, Reuters reported, citing residents and medics. At least two children were killed when another refugee shelter was hit. Dozens of people were injured in both attacks.

At least seven people were killed when missiles struck a hospital in in Ma’arat Al Numan supported by Médecins Sans Frontières, the global medical charity said in a statement on its website. Patients and hospital staff were among the dead. Eight staff are missing and presumed dead.

MSF said four missile strikes destroyed the 30-bed hospital, which employed 54 people and had two operating rooms, an emergency room, and an outpatient department. The hospital treated several thousand people and performed about 140 operations each month, MSF said.

Azaz and Ma’arat Al Numan are located in a region that has seen intensified violence in recent months as Syrian troops and opposition groups fight for control over nearby Aleppo, the country’s largest city. Russia has bolstered the Syrian government’s offensive, launching airstrikes against rebels since September. This weekend, the Turkish military fired artillery shells Kurdish fighters in northern Syria who are considered allies of the United States.

Major world powers announced late last week a “pause” in hostilities in Syria to allow for the delivery of aid to besieged Syrian cities. On the same day, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad vowed in an interview to eventually gain control of the entire country “without any hesitation.”

Better Call Saul: The Fable Continues

You can call Better Call Saul a few things: a prequel, a work of prestige TV, an economic stimulus package for the Albuquerque economy (which would have otherwise taken a hit when Breaking Bad ended). But perhaps the most important ways to think about it are as a writing challenge and as a morality fable. The promise that viewers will see the origins of the criminal-friendly lawyer who enabled Walter White’s escapades creates structural and storytelling conditions that no other show has ever had. It also means that, by necessity, the show will have something to say about psychology and about ethics—not that you’d expect anything else from the Breaking Bad universe.

In season two (which airs Monday on AMC), as in season one, things begin at the end. In artfully composed black-and-white frames, Vince Gilligan flashes to a time after the events of Breaking Bad, with the sadsack formerly known as Saul Goodman now running a Cinnabon in the Midwest. Season one jumped ahead in time to show how someday, Jimmy McGill would live in perpetual fear, unable to relax even when at home listening to records. Season two pulls a similar trick to show how his decision making will eventual change. He accidentally locks himself in the mall trash room, where his only immediate escape is be through a fire door that’s only to be used in case of emergency. Jimmy opts to wait for someone to stumble in and help him, rather than set off the alarm.

Does he do so because he doesn’t want to break the rules by using that door? Or does he stay put out of fear that the alarm would bring law enforcement attention—which could then lead to his cover being blown?

By now it’s clear that Gilligan’s storytelling primarily concerns itself with questions of moral motivation and risk-taking. When people do good or do bad, the common theory goes, they either do so for intrinsic reasons or extrinsic ones. And they do so after cost/benefit analysis. Walter White’s descent into villainy at a certain point flipped from being driven by extrinsic factors undergirded by internal pride—paying his bills without becoming a charity case—to a full-blown, deeply rooted drive to become the biggest drug dealer in the Southwest, no matter the cost. Better Call Saul season one, meanwhile, revealed that Jimmy’s quest to succeed in the legal industry came out of a desire to impress his brother, Chuck. When it became clear that he could never achieve that goal, his priorities reverted to something simpler: using his innate talent for deception to make money.

Yet anyone who thought that season two might settle into a simpler, seedier story now that Jimmy seems to have pledged allegiance to illegitimacy will be surprised. Certainly, for much of the premiere, Jimmy seems to be all-in on the huckster lifestyle. He turns down the cushy law firm job he’s offered and opts to spend his days in the lazy river at a desert resort, bilking naive patrons at the bar.

But there’s a complicating factor—another motivation. Love. It’s revealed that Jimmy only turned down his law-firm gig after receiving assurances from the coolheaded attorney Kim that it wouldn’t impact their relationship. This is, as far as I remember, the first time the show has made it unambiguous that the two really do have an ongoing, officially recognized romantic relationship and not just hints of tension and a shared history. Now that it’s a factor in the plot, Kim’s involvement puts some wobble in what otherwise might be a straightforward trajectory from Jimmy McGill to Saul Goodman.

The sick thrill, always, is in knowing where this all is headed, and the suspicion that a cosmic thunderbolt of justice could strike at any point.

A sequence involving the two of them collaborating on a low-grade scam in the premiere reminds viewers of all the strengths of Gilligan as a filmmaker and Odenkirk as an actor. The plotting, performances, and creative camerawork makes the audience feel as drunk on tequila and hopped up on the thrill of the con as the characters on screen are. But this sequence is the only moment of pure, entertaining payoff provided in the two second-season episodes I’ve seen so far. There’s also the continuation of a farce-like storyline that involves a hapless, newly crooked pharmaceutical worker: basically Walter White if he’d been a lot dumber. The plot line teeters between being amusing and being tiresome; the main fun of it is in affording Jonathan Banks’s wonderful Mike Ehrmantraut more chances to show off his patented glare of impatience.

All of which is to say that Better Call Saul season two is not yet as gripping as season one’s best episodes were. But there’s plenty of reasons to bet it soon could be. While Breaking Bad offered a Shakespearian tragedy about grand ambition and the nature of evil, Saul provides a humble fable about people clumsily groping for a better life. Accordingly, it moves at a more languid pace and spends a lot of time in strip malls and law offices whose all-too-recognizable drabness could have only resulted from careful production design. The underlying sick thrill, always, is in knowing where this all is headed, and the suspicion that a cosmic thunderbolt of justice could strike at any point.

During the premiere, Jimmy finds himself in one of those delightfully tacky New Mexico offices, where a light switch has a piece of tape on it, with a note that it’s not to be flipped in any circumstances. Jimmy, obviously quite different from the guy who eventually is unwilling to open a fire door to escape a dumpster room, flips it. Nothing happens. This time.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower