Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 188

April 17, 2016

The Limits of the Late-Night Comedy Takedown

You wouldn’t know it by looking at him, but John Oliver, the host of HBO’s Last Week Tonight, is a violent man. In the last year, he’s destroyed a “lying, hypocritical GOP idiot.” He’s eviscerated Congress over the issue of America’s infrastructure. Apparently desiring more viscera—this time from ideas rather than people—he went on to eviscerate voter-ID laws. If you take these headlines—and the articles they advertise—at face value, Oliver’s brand of late-night satire is a force to be reckoned with, and a potent political weapon.

Yet, Oliver’s victims remain surprisingly whole. The aforementioned “lying, hypocritical GOP idiot” is now the governor of Kentucky. Congress—approval ratings notwithstanding—continues to function with the same set of people Oliver reportedly eviscerated a few months ago. And, as many people participating in the current Presidential primaries can tell you, voter-ID laws haven’t gone away. Which probably explains why Donald Trump (despite being destroyed, taken down, demolished, systematically picked apart, annihilated, and...murderslayed?) remains the GOP’s presidential frontrunner. Simply put, the bombastic headlines used to describe Oliver’s late-night antics overstate the real-life impact such takedowns can have. At best, such headlines are exaggerations, but at worst, they perpetuate the myth that late-night comedy is an effective tool for broad political change.

Hyperbolic headlines aside, the only people who tend to see issues or politicians being “eviscerated” by Last Week Tonight are ideologically liberal. If a conservative voter watched any of the show clips the above headlines reference, he or she likely wouldn’t see an evisceration, but rather an attack by a biased media. (And, to be fair, the aforementioned conservative also wouldn’t see an evisceration because it’s a near certainty he or she wouldn’t be watching the show in the first place.)

Look at Last Week Tonight’s ancestor, The Daily Show. Its viewers are more politically knowledgeable than most others. Further, its viewers also skew overwhelmingly liberal. Add in the fact that viewers of all ideologies tend to select media sources based on ideological leanings, and it becomes very difficult for any of these late-night segments—be they delivered by Oliver, Samantha Bee, or Trevor Noah—to reach anyone outside a predominantly liberal audience.

Thus, it’s not hard to imagine a scenario where the “interest” created by late-night comedy is merely amplification within an echo chamber. The segments appeal to a liberal audience who may already know about the issue—or are otherwise likely to agree with the show’s position regardless. This also likely explains why interest dies down immediately thereafter—the same audiences are merely moving on to the next segment to share within the same circles. Which, in turn, explains why late-night comedy rarely causes policy change—it undoes its own work the moment the next segment airs.

Last Week Tonight makes for a great case study, as each episode covers at least one story in substantive detail, devoting several minutes to it if not the entire show. In some cases, the top story is so widely covered in the news that it’s impossible to isolate amid the larger conversation around the topic online. Trump’s rise is a great example of this. But in other weeks, whether it’s because the news cycle is slow or because Oliver feels strongly enough about a particular issue, the top story is evergreen—or newsworthy regardless of timing. In those weeks, you can frequently see that Oliver’s show does cause an increase in interest around that subject. The web-analytics firm Parse.ly pooled its data to chart this “John Oliver Effect.” But interest isn’t the same thing as action, which itself is a far cry from political change.

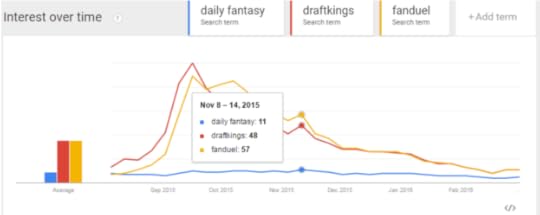

As Parse.ly notes, Oliver’s impact is strongest when it comes to relatively unknown issues, and quickly weakens the more prevalent the issue is. Take, for example, Last Week Tonight’s investigation of daily fantasy sports. The segment aired on November 15, 2015. Per Google Trends, there was a modest uptick in interest the week before the segment, but it’s been in decline since the segment aired—and is much lower than its peak several weeks before the segment.

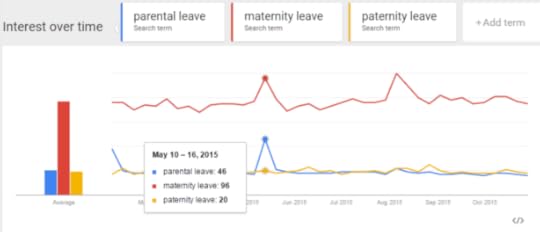

The show’s investigation of paid parental leave, which aired on May 10, 2015, is a good example of its ability to generate temporary interest. There’s a notable uptick in interest in the topic immediately after the segment aired; it’s not a huge logical leap to say the segment caused the interest. But a week after the segment, interest fell back to previous levels.

To be fair, conflating temporary interest with change is an easy trap to fall into. It’s true (and compelling) that the FCC website crashed immediately after Oliver’s segment on net neutrality, but examining the glut of comments that crashed the site reveals that relatively few are explicitly tied to Oliver or Last Week Tonight. Similarly, Oliver’s “Our Lady of Perpetual Exemption” church, established to complement his piece on televangelism, received a staggering amount of donations—enough that Oliver closed it rather quickly and donated the proceeds to Doctors Without Borders. Yet televangelism hasn’t gone anywhere, and while the donation is certainly a net positive, it’s a small blip on the radar that didn’t translate to long-term results.

Which isn’t to say that John Oliver and Last Week Tonight haven’t done good. But several of Oliver’s “victories” are likely better credited as assists, which coincided with major events. Last Week Tonight has covered FIFA corruption multiple times, including before last year’s arrests of several top executives. But the chronology between the air date of the first FIFA episode and the start of the investigation that ultimately toppled Sepp Blatter were almost a year apart—a long enough time that it’s hard to credit Oliver. It’s far easier (but also far more rare) to credit Last Week Tonight with helping reform the bail system in New York City, a move that Bill de Blasio announced within a month of the show covering the topic. It’s a legitimate win, but also precisely the type of win (an obscure but important issue, only within the geographic boundaries of a city with an enormously liberal voting bloc) that Last Week Tonight is limited to achieving.

That’s a far cry from winning on national issues like voter-ID laws, predatory televangelism—or stopping Donald Trump. Following Oliver’s #MakeDonaldDrumpfAgain bit, thinkpieces sprung up praising the efficacy of this form of journalism (though Oliver himself has rejected that label). One Bustle article posited that Wikipedia having a “Donald Drumpf” page is a sign that Oliver’s attack is going to stop Trump, while a Vanity Fair article already assumed efficacy on the part of Oliver and only wondered if the attack came too late.

Meanwhile, the hosts of these shows seem more than aware of their limitations. “My years of evisceration have embettered nothing,” the former Daily Show host Jon Stewart laments at the end in a clip highlighting that virtually every problem The Daily Show covered in his 16 years as host remains just as bad—if not worse—than ever before. Meanwhile his successor, Noah, has changed the tone and substance of the show and is less likely to engage in the substantive barbs that marked some of Stewart’s best-known segments.

The heir apparent to Stewart’s style, Samantha Bee, whose TBS show Full Frontal debuted earlier this year, does engage in substance at the same level as her former Daily Show colleague did, but it seems unlikely her “eviscerations” would fare much better. Her experience trying to fact-check a group of Trump supporters helps illustrate why, and goes back to the point of how big a role ideology plays in how receptive viewers are to what they see on TV. A correction to anything Trump (or any politician, really) claims is viewed with a partisan lens rather than an objective one. In many cases, a citizen, when presented with a correction to misinformation, doubles down on the misinformation rather than changing his or her beliefs. Thus, it’s no wonder that support for Trump hasn’t wavered in the face of numerous attacks, be they from Oliver, Bee, or anyone else.

To be clear, this isn’t an indictment of any late-night host—as Stewart noted, they already recognize their limits, no matter how funny, investigative, or correct their segments may be. Nor is it an indictment of those who share funny video clips with friends—that’s part of what the Internet is for. That said, given that these segments don’t change policy outcomes and that interest in these bits is pretty ephemeral, it’s time to stop pretending these progressive late-night shows have more calculable political power than they do.

April 16, 2016

An Earthquake in Ecuador

A magnitude 7.8 earthquake shook Ecuador Saturday night, killing at least 41 people and likely wounding dozens more.

The tremor struck about 108 miles northeast of Quito, the capital. Ecuadorean Vice President Jorge Glas said the death toll is likely to rise in a televised address to the nation.

The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center issued a tsunami warning for Ecuador after the quake, although severe flooding appears unlikely.

Early reports on social media showed inhabitants in some towns near the earthquake’s epicenter without power.

Sin electricidad en ciudadela en Samborondón. Habitantes se resguardan a la espera de que la situación se normalice. pic.twitter.com/Cn24UXp3uU

— Bessy Granja Barriga (@bessygranjaOK) April 17, 2016

President Rafael Correa, who was attending a conference in Rome, said via Twitter he would immediately return home.

Lo más pronto que podemos regresar es 10h00 hora de Roma, 3h00 hora de Ecuador.

Llegaremos en la tarde.

¡Ánimo!

— Rafael Correa (@MashiRafael) April 17, 2016

Ecuador borders the “Ring of Fire,” a seismically active arc that curves around the Pacific Ocean from Australia to South America. Another country along the arc, Japan, also saw large earthquakes last week, killing dozens.

This story will be updated with more information.

Confirmation: Another Teachable Moment in American History

In this current moment of political debauchery—of name calling and journalist shoving and gun engraving and violence inciting—it’s worth remembering the last time that the national imagination was unwillingly drawn to the penis size of a candidate for one of the most powerful jobs in the land.

In 1991, while Donald Trump was filing for the first of his four corporate bankruptcies, Anita Hill was testifying to the Senate Judiciary Committee that the Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her while he was her boss at two different government agencies. The vestiges of the hearing remain woven into the cultural fabric—the infamous Coke can, Long Dong Silver, Thomas’s stony silence in the 25 years he’s been on the court—but it’s easy to forget what an extraordinary spectacle it was at the time. Just as FX’s The People v. O.J. Simpson recently used a decades-old trial to reckon with a traumatic chapter in America’s history, HBO’s new dramatization of the hearing, Confirmation, casts a harsh light on a historical moment that feels almost more relevant than ever.

This isn’t the first time Hill’s testimony has resurfaced: In 2010, it emerged that Thomas’s wife, Ginni, had called Hill and left her a voicemail asking her to finally “consider an apology sometime and some full explanation of why you did what you did with my husband.” The message plays in the opening scene of Anita, Freida Lee Mock’s 2013 documentary about Hill, which made a thorough and convincing (if one-sided) case that she’d been telling the truth, and had been railroaded by a Senate committee in which both sides wanted her out the way. “The Democrats really didn’t rescue Anita Hill the way they could have,” says the New Yorker writer Jane Mayer in that movie, “and the Republicans were busy disemboweling her.”

Confirmation, directed by Rick Famuyiwa (Dope) and written by Susannah Grant (Erin Brockovich) seems less intent on re-adjudicating or picking a side than simply recreating events and letting them resonate (it uses a wealth of archival news footage, often splicing its actors in alongside real people). Hill (Kerry Washington) is a law professor at the University of Oklahoma when she learns that her former boss, Thomas (Wendell Pierce), has been nominated to the Supreme Court to replace the retiring Justice Thurgood Marshall. When a friend asks her if she might consider going public about her experiences working for Thomas, Hill demurs. “I saw women have their lives ruined because they spoke out against a manager at a diner,” she says.

But she clearly feels uneasy about his appointment, and when a staffer for Ted Kennedy (Grace Gummer) calls her to ask if it’s true that Thomas harassed female employees while he was the head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Hill is compelled to state what happened to her. She files a confidential affidavit for the Senate Judiciary Committee, which is promptly leaked to Nina Totenberg, leading to Hill being publicly named and called to Washington to testify in front of the nation.

As you might expect from an HBO True Washington Story™, there are scores of notable actors popping up in minor roles, notably Greg Kinnear as Joe Biden, whose folksy, combovered turn as the now-Vice President is unnervingly convincing. Treat Williams plays Ted Kennedy, whose own checkered background with women is one of the many reasons the committee didn’t feel comfortable digging too vigorously into Thomas’s past. Bill Irwin is particularly oily as the Missouri senator John Danforth, Thomas’s mentor, who’s so enraged by Hill’s testimony that he smears her as suffering from erotomania, and pursues obviously fake claims from students that she left pubic hair in their textbooks.

Confirmation seems less intent on re-adjudicating or picking a side than on simply recreating events and letting them resonate.

Subtly, though, Famuyiwa and Grant counter the scenes featuring men in power by focusing on the lower-profile women around them. Gummer’s character, Ricki Seidman, takes Hill’s affidavit to a Biden staffer, Harriet Grant (Zoe Lister-Jones), and Seidman is shown entreating Kennedy personally to defend Hill. One of the staffers on the White House team working feverishly to get Thomas confirmed is Judy Smith (Kristen Ariza), whose career as a DC fixer later inspired Scandal, the ABC show starring none other than Kerry Washington. And as much as the movie focuses on Thomas, and his immense anger and obvious pain, it seems compelled to feature his wife, Ginni (Alison Wright of The Americans), and the great toll the hearing took on his family.

Pierce’s Thomas is as inscrutable as the real deal, having very little to work with except rage and recrimination. The hearing’s testimony is reproduced verbatim from public record, including the moment when Thomas condemned it as “a travesty … a circus, a national disgrace … a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks.” After he states that he’s being “caricatured by a committee of the US Senate rather than hung from a tree,” the camera cuts to the faces of the men facing him, all of whom are left totally speechless. One exhales, slowly. Later, Hill’s lawyer, Charles Ogletree (Jeffrey Wright), interprets what just happened: “He only acknowledged race because it was about him. You think any of those white boys on that committee are prepared to challenge him now?”

Washington embodies Hill with poise and halting grace, mimicking the slow articulation of her complaints, and the humiliation the Senate panel put her through by forcing her to restate details of Thomas’s behavior—that he talked to her frequently about pornographic movies he watched involving group sex, rape, and animals; that he boasted about his own sexual prowess and endowment; that he repeatedly asked her to spend time with him outside the workplace. “He said,” she tells the panel, “that if I ever told anyone of his behavior, I would ruin his career.”

Yes, and no. In revisiting the hearing 25 years after it happened, Confirmation offers a chance to consider its impact, and what it lacks in stylistic verve, it makes up for in methodical storytelling. Hill went back to Oklahoma believing that her reputation had been “ruined,” but the movie shows that to a great number of women all over the country she’d become something of a hero. The number of sexual-harassment cases filed in the U.S. doubled the following year, and in 1992, five female senators were elected, with the media dubbing it “the year of the woman.” Three women now sit on the Supreme Court.

As meticulous as the movie is about emphasizing the he said-she said nature of proceedings (it features only one of the four women who traveled to DC to support Hill’s testimony with accusations of their own, and whom Biden never called upon), it makes a solid case for the character of Hill herself. Far from being a scorned woman or a vengeful employee, she was a quiet law professor who simply wanted her concerns about a man appointed to the highest court in the land noted. That her account became such a circus speaks more to the nature of political power itself, which still largely lacks the dignity with which Anita Hill came to Washington.

Game of Thrones and ‘Empowerment’: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Thrones of Blood

Clive James | The New Yorker

“Everyone in the show is dispensable, as in the real world. But without Tyrion Lannister you would have to start the show again, because he is the epitome of the story’s moral scope. His big head is the symbol of his comprehension, and his little body the symbol of his incapacity to act upon it. Tyrion Lannister is us, bright enough to see the world’s evil but not strong enough to change it.”

How “Empowerment” Became Something for Women to Buy

Jia Tolentino | The New York Times Magazine

“The world was built on a misaligned foundation; no amount of awareness can change the fact that it’s the already-powerful who tend to experience empowerment at any meaningful rate. Today ‘empowerment’ invokes power while signifying the lack of it. It functions like an explorer staking a claim on a new territory with a white flag.”

“We’re Creating a World That Feels True”

Caroline Framke | Vox

“Everyone on The Americans is working toward the same goal. This sounds like an obvious statement, but trust me: With so many variables in play and so little time to get everything done, that kind of teamwork is both rare and prized. If a set is like a train hurtling toward its destination, any bit of discord on the route clashes against the tracks and creates a warning spark—and the more that happens, the more likely it is that the whole thing will derail.”

Why Hamilton Matters

Jeremy McCarter | BuzzFeed

“When people talk about the role of the arts in our national life, the conversation tends to be dominated by the culture wars, the flashpoints when some outré performance starts everybody screaming. But as the broad embrace of Hamilton demonstrates, artistic expression more often, and more powerfully, has been an integrating force in American life.”

On Kobe Bryant

Nikil Saval | n+1

“Late Kobe, like late Hemingway, was a throwback to himself. The violent jabstep; the crossover and pump-fake; the heedless drive into the lane against multiple defenders before the nervous retreat into the fadeaway, his body hinging and snapping, his oversized jersey billowing, his shot—more likely than not—clanging out. What once seemed like a kind of vicious genius became what it perhaps always was: theatrical, ritualistic gestures toward a game that no one played any more, and with reason.”

“Yet I’ll Speak”: Othello’s Emilia, a Rebuke to Female Silence

Caitlin Keefe Moran | The Toast

“How had no one ever told me about Emilia, who, in only a couple of lines, brings down one of the most conniving, merciless villains in all of Western literature? How had no one told me about this fantastic female character who defies not one but two sword-wielding men in order to make sure Desdemona, her mistress and friend, receives justice? I wanted to rip up my diploma.”

Hannah Horvath, Why Do We (Still) Hate Thee So?

Kathryn VanArendonk | Vulture

“Beyond that cultural framework, though, there’s another way to consider Hannah’s strangely potent impact on her audience: as a character on a TV show. She is, after all, not a real person, and not a direct extension of her creator, much though that conflation seems to plague her critics. She’s a construction, made for the express purpose of being viewed by others, and so it’s especially befuddling that she’s so constantly bad at pleasing us.”

The Marginalized African Songbird Who Finally Became Visible Again

Robin Kelley | The Conversation

“But Benjamin never strayed from her devotion to modern jazz as ‘the most liberating music on the planet.’ Ironically, that same commitment ensured her marginalization, as beautiful romantic ballads and torch songs lost their relevance in a highly nationalistic era of urban militancy. And as a colored South African woman working in a genre too often construed as black—and as white, male and essentially American—Benjamin had to struggle just to be heard.”

Calvin Trillin’s New Yorker Poem Wasn’t Just Offensive. It Was Bad Satire.

Katy Waldman | Slate

“Effective parodies have a double consciousness—the enlightened perspective of the poem both envelops and refutes the blinkered viewpoint of the speaker. Trillin’s verse doesn’t give us enough reason to think its parodic heart is any more honorable than its bigoted tongue. Sure, if he were a Chinese writer, we’d have extradiagetic reasons to trust him, but the poem itself shows little indication of objecting to what’s really objectionable about its insensitive narrator.”

A Good Fit: Why the Best Thing About Catastrophe Is People Laughing

Linda Holmes | NPR

“By following models where the characters don’t notice jokes—by prohibiting them from laughing at laugh lines—lots of romantic comedies rob themselves of one of the primary ways people create connections and one of the ways close relationships are navigated and negotiated. Rob and Sharon use laughing as glue, as distraction, as entertainment, as team-building, and ultimately as reassurance to each other that in a world full of battles towering and stupid, they mean to be working together.”

Capturing David Bowie

Photographer Steve Schapiro was invited to photograph David Bowie one afternoon in 1974. The musician showed up at 4pm, Schapiro recalled, and the two men worked until dawn. “From the moment Bowie arrived, we seemed to hit it off. Incredibly intelligent, calm, and filled with ideas,” Schapiro said. Bowie came prepared with several costumes, testing out new personas for the camera. “He talked a lot about Aleister Crowley, whose esoteric writings he was heavily into at the time,” Schapiro said. “When David heard that I had photographed Buster Keaton, one of his greatest heroes, we instantly became friends.” The images taken that night went on to appear on the albums Station to Station and Low, as well as on the cover of People. One outfit, a diagonally striped navy number, even appears in Bowie’s video for Lazarus. But many of the images were never published—until now. Schapiro’s photographs of the late artist have been collected in a new book, Bowie, published by PowerHouse Books. A selection can be found below.

April 15, 2016

The Democrats' Most Substantive Climate Debate Yet

On Thursday evening, the two remaining Democratic candidates for president, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, paired off at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for their most sophisticated debate yet over setting the right energy and climate-change policy for the country.

The location made sense: Seven decades ago, the shipbuilders there earned a national reputation for their hardworking speed and can-do attitude. Seven decades from now, the shipyard could very well be under water—a victim of a crisis that humanity didn’t act fast enough to stop.

Their exchange got right to the weaknesses of the two candidates’ climate positions. To her critics, Clinton is too entrenched with fossil-fuel interests to do what needs to be done for the climate. Notably, she opposes a tax on carbon emissions, a measure so mainstream that it was sought by President Obama early in his first term. Sanders, meanwhile, can act more like an old-school green than a modern climate realist, opposing more pragmatic paths to quickly reducing carbon emissions (like nuclear power) due to their local environmental risks. And here as elsewhere, his calls for revolution can devolve into mere incrementalism when he’s pressed.

Clinton’s industry ties were the focus of the first half of their exchange. Sanders, echoing a criticism that his campaign has repeatedly leveled in April, hammered her for accepting campaign donations from oil-and-gas industry employees and lobbyists.

“Some people say, well, given the hundreds of millions of dollars she raises it’s a small amount,” he said. “That’s true. But, that does not mean to say that the lobbyists thought she was a pretty good bet on this issue.”

It’s a classic Sanders attack, focusing on the appearance of soft corruption. And Clinton has accepted about $3 million in donations from lobbyists associated only with the fossil-fuel industry (though that’s a smaller number than the Sanders camp has claimed). According to an NPR fact check, employees in the oil and gas industry have donated $300,000 to Clinton’s campaign. By comparison, they’ve donated more than $1 million to Ted Cruz, about $50,000 to Sanders, and less than $10,000 to Donald Trump.

But later in the exchange, Sanders was able to tie the appearance of corruption to a specific policy, asking: “Are you in favor of a tax on carbon so that we can transit away from fossil fuel to energy efficiency and sustainable energy at the level and speed we need to do?”

Clinton, who does not support a carbon tax, didn’t answer directly. He pressed her again, and she still didn’t answer—though the moderators cut them both off. Her opposition is somewhat confusing. Carbon taxes are considered by many economists to be the ideal small-c conservative response to climate change: They price in global warming’s externalities, while allowing the market to choose how to divert resources elsewhere. (For her part, Clinton says she supported dropping subsidies for the oil industry while she was secretary of state.)

But when they got to what energy policy should include beyond a carbon tax, things got more muddled.

As secretary of state, Clinton pushed to expand hydraulic-fracture mining for natural gas (“fracking”) around the world; now, she wants to limit its use, but not ban it outright. Sanders, meanwhile, opposes fracking in all its forms. NY1’s Errol Louis asked Clinton why she changed her view.

“No, well, I don’t think I’ve changed my view,” she answered, saying she has always seen natural gas as a “bridge” between dirty-burning coal and clean, renewable energy. She added that expanding the use of fracking worldwide helped the United States strategically, as it decreased Russia’s ability to sell oil and gas to countries in Eastern Europe.

Though Clinton was at pains to make it look like her views haven’t changed, she could have just said that the expert understanding of fracking has changed. When drilling was new, many environmentalists supported it. There’s a good reason for that: Fracking has reduced U.S. carbon emissions by six percent this decade, devastated the coal industry, and changed the global economics of energy. And though fracking can have horrifying local environmental consequences, they do not seem to be nearly as widespread as initially feared. (In 2008, solar and wind power also just weren’t efficient enough as technologies to generate the electricity they can now.)

Now, many more climate hawks oppose fracking outright. Recent studies have indicated that the although it may have helped the U.S. reduce its carbon emissions, those gains were largely offset by increases in methane leaks from the fracking process. While methane doesn’t last as long in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, it is much more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere for short periods of time. (Because of this, the Obama administration is also starting to regulate methane leaks from fracking operations.)

Then the moderators turned to Sanders, who opposes not only fracking but also all nuclear-power generation. Nuclear generates 20 percent of U.S. electricity without emitting any greenhouse gases, so this policy strikes some climate-concerned folks as a little strange. (It makes much more sense as a holdover view from Sanders’s 60s-era activism.) Louis, the moderator, asked Sanders:

You’ve said that climate change is the greatest threat to our nation’s security. You’ve called for a nationwide ban on fracking. You’ve also called for phasing out all nuclear power in the U.S. But wouldn't those proposals drive the country back to coal and oil, and actually undermine your fight against global warming?

This is the most important question to ask about Sanders’s energy policy. He didn’t answer it directly, instead turning to the broad language of emergency: “We have a global crisis. Pope Francis reminded us that we are on a suicide course,” he said. Then he started talking about the need for infrastructure spending and the plight of coal workers in a transitioning economy. (A plight, it should be added, that is getting worse and that should be addressed by public policy.)

But Louis pressed him, asking how, “with less than 6 percent of all U.S. energy coming from solar, wind and geothermal, and 20 percent of U.S. power coming from nuclear,” he would keep carbon emissions from rising again.

And he relented, admitting, “Well, you don’t phase it out tomorrow. And you certainly don't phase nuclear out tomorrow.”

It wasn’t a wrong answer, but it sounded indistinguishable from the “incrementalism” he had lambasted in the same exchange.

Throughout the back-and-forth on climate, Sanders compared global warming to warfare. The United States should respond to melting icecaps like it would respond to a foreign invasion, he said:

If we approach this, Errol, as if we were literally at a war—you know, in 1941, under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, we moved within three years, within three more years to rebuild our economy to defeat Nazism and Japanese imperialism. That is exactly the kind of approach we need right now.

The idea that climate change will require a mass economic mobilization on the level required by World War II is an increasingly popular idea among environmentalists. It’s been written about in these pages, and Al Gore has called for it as a way to end the global savings glut. It is also the opposite of the world’s current approach, which is effectively to divert investment from fossil fuels to clean energy. Seeing this idea enter mainstream Democratic rhetoric so forcefully bodes well for its chances.

Not that a mass mobilization—or a carbon tax—looks any likelier to happen in the short term. This may be the the only nuanced debate that American voters will hear this year over how to respond quickly to climate change. That’s because, while Democrats volley over how to respond to the problem, many leading Republicans straight-up don’t recognize the reality of global warming. Both Donald Trump and Ted Cruz deny that climate change is either real or human-caused, rejecting the consensus of NASA researchers, of 97 percent of all climate scientists, and of every major American scientific academy, including the American Medical Association. (Cruz’s claims here are especially bizarre.)

In most other developed countries in the West, the debate over climate change tends to happen between climate “hawks” and “doves”: those who think the economy must be restructured away from fossil fuels immediately, and those who think a slower transition is more feasible while remaining safe. Strangely, that’s not quite the debate that happens here yet, even within the Democratic party.

But it hardly matters. In the general election, one of these two candidates will call for a mix of policy solutions to address one of the gravest geopolitical threats this century. Their Republican opponent will likely say that the threat doesn’t exist.

Game of Thrones, Take Your Time

For five years, Game of Thrones has been a project of expansion: ever more characters, ever more lands, ever-bigger battles, and ever-bigger ratings. But now, the show creators might start pulling on the reigns of the behemoth that is Thrones, bringing it home while slowing it down.

“I think we’re down to our final 13 episodes after this season,” David Benioff told Variety’s Debra Birnbaum. “We’re heading into the final lap. That’s the guess, though nothing is yet set in stone, but that’s what we’re looking at.”

He added that the hypothetical finale run would be split into seasons of six and seven episodes in length—shorter than the standard annual Thrones serving of 10.

It’s a plan that recalls the profit-maximizing and often viewer-antagonizing strategy that this decade’s other major film and TV franchises have used when bringing their sagas to a close. The Hunger Games, Harry Potter, and Twilight movies all divided their ultimate installments into two, and Breaking Bad and Mad Men ended their runs with two years of mini seasons. Generally, this maneuver is perceived to be driven less by the desire to tell a good story and more by the desire to give the financial stakeholders one more payday.

But when it comes to Throne, calling it quits with shorter seasons could be the least cynical choice the creators could make. Viewer obsession with the show is so high that ratings might only grow for years to come, and HBO—which, after a middling reception for Vinyl, is currently hurting for culture-commanding Sunday dramas—likely doesn’t want to hasten the arrival of the post-Thrones era. Network president Michael Lombardo sounded diplomatic when Variety asked about Benioff and co-creator D.B. Weiss’s plan, saying he was open to the idea of ending in 2018 but adding, “As a television executive, as a fan, do I wish they said another six years? I do.”

Even if Thrones decides to run for longer, shorter seasons might help the show overcome obstacles that would seem to naturally arise from the unique situation it now finds itself in. Famously, most of its plotlines are about to outpace the Song of Ice and Fire books series upon which they’re based, and without the steady girding of George R.R. Martin’s meticulous work, creating the show has necessarily become a tougher task: In addition to scripting and filming a host of actors in locations across the world, Benioff and Weiss have to also wholly invent story. Martin, yes, has reportedly given them the big bullet points about how he expects the the series to unfold, but that is not the same thing as having tome-length guides for how exactly it all happens.

Without the girding of George R.R. Martin’s meticulous work, creating the show has necessarily become a tougher task.

It’s a challenge that gets to the heart of why Thrones appeals in the first place. One of the biggest things that sets the show apart from most works of popular fantasy entertainment is the sense that realistic cause-and-effect logic drives its action: Unlike with, say, The Force Awakens, viewers rarely are faced with a coincidence that they have to chalk up to destiny or magic or simple writer’s room convenience. This is unique in the world of mainstream entertainment, surely, because it’s hard to pull off. Martin, up to this point, had done the legwork for Benioff and Weiss; it takes him so long to write each installment in part because he has to figure out how to move the extremely complicated narrative along without resorting to shortcuts. And in addition to no longer having the simple and inexorable logic of Martin’s plot to build upon, Benioff and Weiss also have to create dialogue and setting details from scratch for nearly every single scene.

Logic would dictate that tackling this challenge would take more time, and therefore would mean that Benioff and Weiss could create fewer episodes in a year. Of course, season six, which premieres next Sunday, will run a full 10 weeks. Perhaps Benioff and Weiss’s writing team worked extra nights in the past year to keep the plot feeling as solidly constructed, as weirdly believable, as previous Thrones seasons have been. But if getting the story right in the future means they need to slow down, fans shouldn’t complain: It’s quality, not quantity, that keeps Thrones from being just another TV show.

Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt: More Madcap Than Ever

It makes perfect sense that Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt was a breakout hit for Netflix in its first season: The series brought Tina Fey’s wildly successful, madcap NBC style to the binge-watching world, and confronted dark issues with her typical verve. Simply put, viewers who liked season one are going to like season two, which (much like Fey’s previous show 30 Rock) doubles down on everything that worked before without worrying about appealing to a broader audience. Once again, Fey and her trusty co-creator Robert Carlock have offered up more bizarre, whimsical adventures for fans to barrel through.

Related Story

Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and the Sunny Side of Surviving

For such a deliberately cartoonish show, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt has a remarkable grasp on its central character’s buried traumas and the ever-widening gulf between New York City’s moneyed class and the victims of their wave of gentrification. And like 30 Rock, it routinely crams 10 incisive one-liners into a single, ludicrous exchange, making even the most absurd moments feel meaningful. In the first six episodes made available to the press, the show’s second season only appears to truly misfire once, in the third episode, which plays out as a bizarre, tone-deaf diatribe against those who’ve criticized the show in the past. It sits uncomfortably alongside an otherwise sterling batch of television, serving as a valuable reminder that Fey, like all the best comic minds, has her blind spots.

But first, the bigger picture. Kimmy Schmidt’s second season largely tracks along the lines of the first: Liberated after her kidnapping by a religious cult, Kimmy (Ellie Kemper) is a happy-go-lucky teen in an adult woman’s body, whose buffoonery belies impressive insightfulness and a strong moral compass. She’s navigating life in New York with her roommate and wannabe actor Titus Andromedon (Tituss Burgess), her batty landlady Lillian (Carol Kane), and her former employer Jacqueline (Jane Krakowski), who’s picking up the pieces after the collapse of her marriage to a cruel financier.

Season two pushes things in even more metatextual directions, largely to good ends. Kimmy’s Vietnamese love interest Dong (Ki Hong Lee), who was criticized for his halting, stereotypical speech patterns in the first season, is back with a much mellower accent and a hilariously silly explanation for that evolution. The early episodes of this season seek to explain Titus’s mysterious origin story, a needlessly convoluted tale that ends up succeeding because of its sheer ridiculousness. The first season, meanwhile, was mostly concerned with Kimmy’s backstory and would flash back to her life in the cult, building to a courthouse-drama finale as Kimmy finally took down the man who kidnapped her (played with cheerful aplomb by Jon Hamm).

Even though the show was conceived and shot for NBC (and obeyed that network’s strictures about language and sex), it nonetheless made a surprisingly good fit for the binge-friendly Netflix. The second season sticks to the tone of the first (Kimmy isn’t suddenly dropping F-bombs for the sake of it) but plays a little with the format: There are no obvious commercial breaks required anymore, and episodes don’t have to finish in precisely 22 minutes. That’s mostly a good thing, since Fey and Carlock are smart enough to know where to push the boundaries of the medium and where to pull back. At its best, the series evokes classic 30 Rock (it’s hard to think of a higher compliment).

Which is why the third episode—“Kimmy Goes to a Play!”—feels particularly clunky, and reveals the show’s blunter, crueler side, which is usually counterbalanced by the deep humanity of its main characters. In it, Titus stages a musical about a Japanese geisha whom he insists he was in a past life, and a troupe of angry bloggers (most of them Asian) picket the performance—supposedly to represent the online “outrage brigade” that descends upon a new cause every day. There’s certainly a way to satirize that subject, but the episode gets it all wrong: Titus’s performance is too bizarre (and his character too generally insensitive) for the show to convince viewers that its heart is in the right place. Ultimately, the whole storyline reeks of misplaced anger.

Fey has been vocal about her disinterest in the Internet’s “apology culture.” Her comments were partly prompted by the initial reaction to Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, which trod the “outrage” line with several of its storylines, from Kimmy’s romance with Dong, to Jacqueline’s Native American heritage, to Fey’s portrayal of a Marcia Clark-type lawyer at the end of the season. Most of those stories had enough pathos and wit to work despite the thorniness of those topics. This episode doesn’t, and it’s a misstep that makes it hard to fully enjoy the rest of the season—proof, perhaps, that Kimmy is still a winning show, but one that’s best when it errs on the sunny side.

Could Dilma Rousseff Get Impeached?

In March, millions of people took to the streets in hundreds of cities across Brazil to protest the government. The demonstrators vented their frustrations with a crippling economic recession, corruption scandals, and President Dilma Rousseff, who had presided over both.

“Impeachment now,” read a long, yellow-and-green banner, unfurled above the heads of dozens of protesters in São Paulo.

This weekend, the calls for Rousseff’s impeachment may be answered. Lawmakers in Brazil’s National Congress will decide Sunday whether to go ahead with impeachment proceedings against Rousseff, who is halfway through her second term. The leader of the center-left Workers Party has vowed to fight to “the last minute,” even as political allies have deserted her coalition ahead of the vote and polls show the majority of Brazilians want her out.

Rousseff suggested this week that members of her government were conspiring against her. Brazil is “living in strange times, times of a coup, of farce and betrayal,” she said.

How did this all start?

Last October, a federal court determined that Rousseff’s government had manipulated its financial accounts to hide a growing national budget deficit while she campaigned for re-election in 2014. Rousseff denied any crime had occurred. The ruling gave members of opposition parties the ammunition to begin formal impeachment proceedings.

But even before that court ruling, Rousseff’s government was in hot water—with an entirely different scandal.

In 2014, a money-laundering investigation uncovered the biggest corruption scandal in Brazil’s history at Petrobras, the state-run oil firm and largest company in the country. Investigators discovered an alleged secret network of bribes and kickbacks. Between 2004 and 2014, Petrobras executives overcharged the company for construction contracts and funneled millions of dollars of extra cash to themselves or others, or politicians, including members of Rousseff’s Workers Party. Millions of Brazilians—mostly middle-class people who already opposed Rousseff’s government—protested the scandal. Rousseff was not implicated in the alleged corruption, but it had occurred while she served on Petrobras’s board of directors, and while her political mentor, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, widely known as “Lula,” was president of Brazil. (Rousseff is his handpicked successor.) Rousseff’s approval ratings have plummeted since, and protests have grown to include even her supporters.

What happened this year?

Things got worse. In early March, Brazilian police announced Lula had received illegal kickbacks from the corruption at Petrobras and was “one of the main beneficiaries of these crimes.” “There is evidence that the crimes enriched him and financed electoral campaigns and the treasury of his political group,” police said.

On March 15, Rousseff named Lula her chief of staff, a Cabinet position that would grant him immunity from prosecution. On March 16, the day before Lula was sworn in, a prosecutor in the Petrobras scandal released tapped phone calls between the two politicians that suggested Rousseff gave Lula the job to help shield him from prosecution in the Petrobras scandal. Two days later, Two days later, a justice on Brazil’s highest court suspended Lula’s nomination.

How did lawmakers respond?

On March 17, the day Lula was sworn in, the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Brazil’s congress, voted to create a special commission in charge of an impeachment process against Rousseff. This week, the committee recommended that the legislature seek impeachment. Brazil’s constitution says a president can be impeached for a “crime of responsibility,” and the committee determined that Rousseff’s alleged tampering of budget numbers in 2014 fit that bill. (Fun fact: More than half of the members of that committee are under investigation for corruption or other serious crimes.)

So what happens now?

The committee’s decision paved the way for a full vote Sunday by the lower house. A two-thirds majority is required to move the impeachment proceedings to the Federal Senate, the upper house, for another vote. If the Senate approves impeachment, Rousseff would be suspended and replaced by Vice President Michel Temer as soon as early May. A trial could last six months.

Temer, who himself has been accused of involvement in an illegal ethanol-buying scheme, was heard in audio tapes leaked this week discussing the future Temer administration in the event of Rousseff’s impeachment.

The lower house opened debate on the impeachment Friday.

How does it look for Rousseff?

The vote is too close to call for now. But recent defections from Brazil’s ruling coalition have raised the odds against her. The Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, the country’s largest political party, left the coalition late last month. This week, the Progressive Party followed, saying most of its members would vote for impeachment, the BBC reported. Members of Rousseff’s own Workers’ Party are said to be losing hope.

In a last-ditch effort to stop the proceedings, Rousseff’s government filed a motion with the Supreme Court Thursday to annul Sunday’s vote, arguing that the process had been “contaminated.” On Friday, the court rejected the request.

When was the last time Brazil impeached a president?

In 1992. President Fernando Collor de Mello, facing corruption allegations, resigned the same day the Senate voted to move forward with an impeachment trial.

How Comic Fans Got Their Faith Back

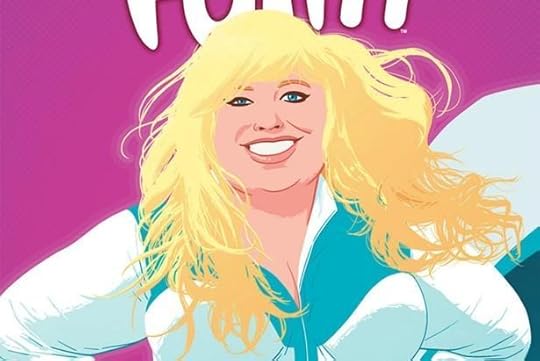

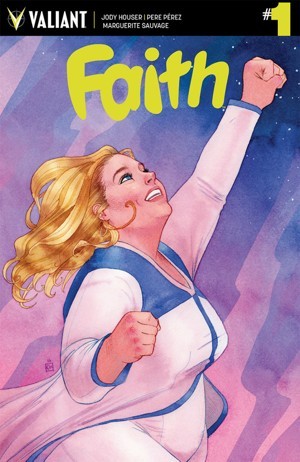

Faith Herbert is a telekinetic superhero in Valiant’s comic universe. She flies through the air donning a bright white and blue jumpsuit, saving puppies, and uncovering corruption around every corner. She's also fat—and not “fat” in the way that popular culture describes plus-size models like Ashley Graham. Faith has a double chin, and that skintight jumpsuit doesn't hide her curves. And the best part for many comic readers is that no one says a thing about it.

Faith may fit in with an increasingly body-positive culture, though she first emerged in 1992 in a Valiant series called Harbinger, which followed the adventures of a group of misfit teenagers. But in that series, Faith and her endlessly cheery outlook on life were constantly plagued by a barrage of fat jokes. And when the series was revived in 2012, little had changed—not her relentless optimism, not the unnecessary digs about her weight, like when a passerby notes, “That fat girl sure is light on her feet.”

But in 2016, things are different: Faith has stepped outside of the Harbinger umbrella and returned in a bestselling miniseries that came out in January. She’s also set to star in her first full series, which will debut in July and feature her first real nemesis, whom she’ll face off against as her story unfolds in monthly installments. This year marks the first time Faith has been written by a woman, the Orphan Black comic writer Jody Houser—and, not so coincidentally, there isn’t a fat joke in sight.

With her 2016 comeback, Faith finally seems to exist in the right time, and readers seem to agree: The miniseries has received the fastest third, fourth, and fifth printing in comic history. Instead of hearing more fat jokes, readers see Faith lounging around her apartment in her underwear or going to her job as a writer at a celebrity-gossip site. And she’s not as ditzy as she was in 1992 and 2012; here, she comes off as whip-smart, effortlessly kind, and supremely confident as she navigates the transition to adulthood. It also doesn’t hurt that she appears to be the consummate Millennial, a woke member of the Tumblr generation working at a BuzzFeed knock-off. Faith’s return to the comic-book landscape represents twin achievements for the medium: an increasing willingness to tell stories featuring heroic women, and a tendency to celebrate the ways in which those women to deviate from (or challenge) gender norms.

“People want to see themselves in comics, but they don’t want to see a character who is just one aspect of themselves—they want to see a fully fledged person like they are.”

Female characters, of course, have always been in comics, but there’s been a notable shift in the way they’re represented. More women and people of color are working behind the scenes on comics as writers and illustrators, which has led to the development of more dynamic and diverse characters: There’s Ms. Marvel, or Kamala Khan, a Pakistani American girl written by the Muslim comic writer G. Willow Wilson. And indie hits like Bitch Planet, a feminist comic introduced in 2014 that features women of all shapes, sizes, colors, and gender identities. And on television, formidable female superheroes star in their own shows: Supergirl, Jessica Jones, and Agent Carter.

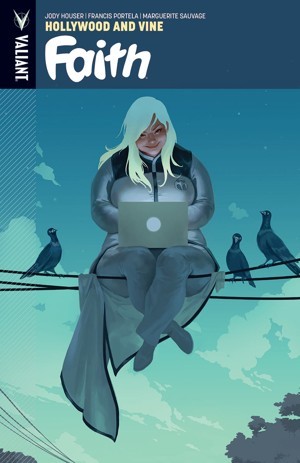

Valiant

And then there’s Faith, who has been covered extensively by media outlets for defying the aesthetic of the typical comic-book heroines audiences usually see (like the slender, raven-haired Wonder Woman). And yet the most compelling thing about her weight is that it’s a non-issue—one that has no bearing on her plotline or her abilities. Faith doesn’t talk about dieting or make self-deprecating jabs about her body. In the miniseries, the artists Francis Portela and Marguerite Sauvage have made her unabashedly large on the page and wholly unselfconscious in the way she carries herself. She doesn’t even destroy enemies with her strength like the vintage Marvel character Big Bertha, whose power is changing from a supermodel into an obese woman before literally crushing her opposition. Instead Faith’s powers defy gravity entirely—she flies gracefully through the air, stopping only to rest on a telephone wire and write a quick blog post.

For Houser, the fact that Faith’s size is seen rather than discussed is completely intentional. “That [Faith] represents a group of people not featured in comics very often is important, but it’s not the most interesting thing about her,” Houser says. “People want to see themselves in comics, but they don’t want to see a character who is just one aspect of themselves—they want to see a fully fledged person.”

Kiva Bay, an artist and social activist who lives in Oregon, often writes and tweets about feminist issues and the way fat bodies are perceived in popular culture. A longtime fan of comics and media, Bay says she was apprehensive at first when she heard about Faith—after all, mass media hasn’t historically done a great job of portraying marginalized groups the first time around. (Consider Hollywood’s long tradition of casting white actors to play characters of color.) “I see a lot of people co-opting body positivity and not really understanding how best to fight the stigma fat people face,” Bay says. “They end up reinforcing fat phobia.” But when Bay read the first issue her immediate response was: “Oh my god, this is everything I ever wanted in a fat character.”

Though Faith has always been a skilled hero, Houser’s Faith now more acutely embodies the idea that fat people can be just as good at what they do as their thin counterparts. Perhaps that seems obvious, but a 2015 experiment published in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes shows that many people subconsciously think otherwise. For their study, the Wharton Business School professor Maurice Schweitzer and the doctoral student Emma Levine asked employers to evaluate resumes that included photos of both thin and obese people. The result? “What we found across our studies is that obesity serves as a proxy for low competence,” Schweitzer says in a press release. In other words: “People judge obese people to be less competent even when it’s not the case.”

Valiant

And it’s clearly not the case with Faith. In the two previous Harbinger series, however, her accomplishments were greeted with surprise. Houser’s Faith, though, gives her the platform to be seen apart from the group in which she appears as the token fat girl (her inclusion in the first place came off as insincere when her size was so often used to insult her.) It’s here where the art of Faith’s story really speaks louder than the writing: It’s so striking when readers see her posed like Superman, or working at a media outlet like basically every male superhero. By playing on these classic tropes, Faith further reinforces the idea that her weight has no bearing on either her “regular” life and career or her superpowers.

For now, Houser says she has no plans to give Faith a storyline based on body-image insecurities or appearance-related bullying. Those narratives can be powerful, like in the episode of the show Louie, where Louis C.K.’s character goes on a date with a waitress named Vanessa who challenges his biases against fat women. Directly approaching these issues can be incredibly valuable in a world where, as Vanessa says, fat women are not supposed to talk about being fat. Faith’s world—one where her weight is a side note at most—may be an idealized one, but it offers a welcome reprieve for fat female comic-book lovers.

By playing on classic tropes, Faith further reinforces the idea that her weight has no bearing on either her “regular” life and career or her superpowers.

The same can’t be said for many other superhero books, movies, and TV shows, even those with the best of intentions. Bay mentions Jessica Jones for instance, a show that by all rights is a step forward for women in pop culture—after all, it features a strong, smart sexual-assault survivor taking on a serial rapist. Yet despite all the progress Jones represents, she’s not immune to mindlessly buying into other forms of casual prejudice. In the first 10 minutes of the show’s pilot, when she’s spying on Luke Cage, her binoculars wander up to a woman on a treadmill who stops to take a bite of a hamburger. “Two minutes on a treadmill, 20 minutes on a quarter pounder,” Jones says bitingly. This is a completely unnecessary scene—it doesn’t serve the plot or the character, since viewers already know she’s bitter and cynical. “One of the things that was so hurtful about that comment was that Jessica Jones created this really powerful umbrella for abuse survivors to gather under,” says Bay, who also wrote a Medium post on the topic. “That line signaled to me that I was excluded from that umbrella as a survivor of abuse and rape. I should be allowed to be part of this community without being the butt of a joke.”

This scene doesn’t erase the good things Jessica Jones does, but fair or not, the books, movies, and shows that are doing the most work promoting diversity are going to undergo more scrutiny than the white-male-led blockbuster. And if these shows are truly as progressive as the want to appear, it’s better for viewers when flaws are exposed. Even Faith isn’t perfect—the fact that she doesn’t mention size could be easily be seen as a disowning of part of her identity.

But in the end, diverse characters like Faith do the most overall good just by being at the center of their own stories. “I think about how excited I was when I was 7 and read a book that had a protagonist who was exactly like me: brown hair, glasses, small for her age, loved writing,” Houser says. “To think that there are women of all ages who never have that experience, that’s hard for me to wrap my head around.” But Faith, and the other diverse characters forging their way in media, is helping to make sure that readers do get those experiences—the ones that show people there is no separating the fat woman you see from the courageous, quick-thinking, telekinetic superhero inside of her.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower