Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 185

April 20, 2016

The Bureaucrats Charged in Flint's Water Crisis

This week, Governor Rick Snyder announced he’ll spend the month drinking water from Flint that’s been run through a water filter. One might call that a sip in the right direction—a gesture to demonstrate to residents that their water can be made safe with the filters, which the state has distributed. Reports suggest Flint residents have been reluctant to use water even after it goes through the filters.

Who can blame them? For months, residents were told their water was safe, even as ever-higher levels of government came to know it was not—in fact, the water was contaminated by poisonous levels of lead. On Wednesday, Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette announced charges in connection with the scandal. The names on the list don’t include the governor, the former head of the state Department of Environmental Quality, the city’s former emergency manager, or any of the other names that have appeared prominently in reports about the poisoning.

Related Story

What Did the Governor Know About Flint's Water, and When Did He Know It?

Instead, the three men charged today are relatively low-level bureaucrats. One is Mike Glasgow, the utilities administrator for the city of Flint. The other two are Stephen Busch, who was a district administrator for the drinking-water program at the DEQ, and Mike Prysby, who was an engineer at the department.

Busch and Prysby face the most serious charges. Prysby has been charged with six counts, each carrying maximums of between one and five years imprisonment. Four are felonies: two each of misconduct in office and one each of tampering with evidence and conspiring to do so. He also faces two misdemeanor counts of violating the Safe Drinking Water Act. Busch faces nearly the same slate, but only one count of misconduct in office. Glasgow has been charged with willful neglect of office and with tampering with evidence by changing test results to show lower lead levels in city water than were actually present.

In each case, the men seem to have had misgivings about Flint’s decision to switch away from the Detroit Water system and begin drawing water from the Flint River instead. The water in the Flint River turned out to cause corrosion in Flint’s aging lead pipes, which produced elevated levels of lead in drinking water. Heavy use of chloride to treat the water’s smell and taste created additional corrosion problems. A Legionnaire’s disease outbreak has also been traced to the water. But once the switch was in place, officials say, all three misled the public and other officials.

In January 2013, Prysby expressed concern about complications from switching to the Flint River. Two months later, in March, Busch cautioned that “Continuous use of the Flint River at such demand rates would: Pose an increased microbial risk to public health ... Pose an increased risk of disinfection by-product (carcinogen) exposure to public health … [and] Trigger additional regulatory requirements under the Michigan Safe Drinking Water Act.”

As the switch neared, Glasgow too had serious reservations. On April 17, 2014, he wrote to Prysby and Busch, “If water is distributed from this plant in the next couple of weeks, it will be against my direction. I need time to adequately train additional staff and to update our monitoring plans before I will feel we are ready. I will reiterate this to management above me, but they seem to have their own agenda.”

But in a city press release on April 25, Glasgow was quoted speaking approvingly about the switch:

For nearly 10 years Mike Glasgow has worked in the laboratory at the City of Flint Water Service Center. He has run countless tests on our drinking water to ensure its safety for public use. Mike has not only conducted tests on water provided to us by Detroit, but also on local water from nearby rivers, lakes and streams including the Flint River. When asked if over the last decade if he has seen any abnormalities of major concern in the water, his response was an emphatic, "No."

Where Glasgow got in trouble was with the testing of water. The samples that the city sent for testing came from houses with a variety of plumbing systems, rather than from high-risk locations with lead pipes. Glasgow blames that discrepancy on incomplete records, but officials say he signed a document affirming the samples came from high-risk houses. The result was artificially low levels of lead from the tests.

The crux of the allegation against Prysby and Busch is that they tried to impede investigations by the Genessee County Department of Health and by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. An EPA regulator named Miguel Del Toral became interested in the case and peppered the state DEQ with questions about what procedures were in place. In February 2015, Busch wrote to Del Toral that Flint “Has an Optimized Corrosion Control Program,” which was not true. Del Toral continued to probe the status of Flint’s water. On April 27, Busch complained to coworkers in an email: “If he continues to persist, we may need Liane [Shekter-Smith, head of the DEQ drinking-water program] or [DEQ] Director [Dan] Wyant to make a call to EPA to help address his over-reaches.” In the short term, that seems to have worked: Workers heard a few months later that “Mr. Del Toral has been handled.” (Del Toral has since accused EPA officials of muzzling him. The EPA denies this, but the official in charge of the region was forced to resign.)

Busch was suspended from DEQ in January pending the investigations. The Detroit Free Press reported Monday that Prysby had moved to another job in DEQ. While he did not respond to the paper, a spokeswoman said Prysby had not been forced to change jobs. In addition to the criminal charges Wednesday, Glasgow has said that Prysby told him the city of Flint did not need to use phosphate to coat the pipes and prevent corrosion. And Prysby was the subject of unflattering media attention when a September 2014 email to a colleague surfaced in which he wrote, “Thanks Richard...now off to physical therapy...perhaps mental therapy with all of these Flint calls....lol.”

Schuette, the state’s attorney general, said during a news conference Wednesday that the charges were the beginning and not the end of his investigation, and suggested that more individuals would be charged. He did not say who might be charged, saying that no one had been ruled out and that there was no target list.

One can guess some of the people who might still be charged. For example, there’s the DEQ official who appears in messages to be pressuring Flint to produce samples below the acceptable federal level of lead. There’s Shekter-Smith, Wyant, and DEQ spokesman Brad Wurfel, who were both forced to step down. And there could be other officials in the mix. As The Huffington Post notes, Schuette was initially reluctant to investigate the Flint situation, and reversed course only after massive national attention focused on the story. The FBI and several other federal agencies have also launched investigations.

Perhaps Schuette is starting with small fry in order to get to the big fish, but the fact remains that the indictments seem unlikely to sate the lust for revenge that many in Flint and beyond feel. If Schuette’s allegations are true, then the early misgivings that Prysby, Busch, and Glasgow gave don’t exculpate them—in fact, they underscore the misconduct, because they demonstrate that the trio ought to have known better.

But at the same time, those misgivings point to the fact that Glasgow, Busch, and Prysby were not the policymakers who conceived the disastrous switch to the Flint River as a water source. What about former Flint Emergency Manager Darnell Earley? What about Snyder? What about the officials in the governor’s office who knew about problems with Flint’s water, even if (as he says) they didn’t tell him? What about Wyant? It may be much easier to catch low-level employees on counts such as these—unlike political appointees, they are less likely to be conscientious about what they communicate via email, and as a result get tripped up. Or it may be that though top officials acted unacceptably or unconscionably, they simply did not commit any crimes.

A task-force report released last month provides relevant perspective. That panel, appointed by Snyder, came back with scathing conclusion—placing some blame on EPA, but most of the blame on the state, from Earley, the emergency manager whom Snyder appointed, right up through the DEQ to the governor’s office. The major message of that report was not that there had been a massive criminal conspiracy to poison city, but that there had been multiple, serious, systemic failures of government.

One lesson of the task-force report was that the Flint crisis began with a political failure. Because Snyder had appointed an emergency manager to run the city, the people of Flint had little voice in the switch and no method of holding its leaders accountable. One lesson of the criminal inquiry may be that the judicial system might not be the most effective tool for dealing with the ensuing crisis. Political failures at a high level may be best dealt with by the political system.

Rihanna's Righteous Music-Video Murder Spree

The just-released clip for her song “Needed Me” represents the third time that Rihanna has murdered a guy in a music video. In 2011, she tearily took a gun to a rapist for “Man Down,” triggering the Parents Television Council’s condemnation. Last year, she baited various ideologies of Internet commentators with her “Bitch Better Have My Money” video’s tale of kidnapping a woman and dismembering her husband, a shady accountant. Now, for “Needed Me,” she strides into a strip club and shoots a tattooed guy for unspecified reasons. Her apparent disinterest in the consequences to her actions within the world of the video is equal to her apparent disinterest to the consequences outside of it.

Last year, I speculated that images of female pop stars acting violent were becoming more common because of shifting gender conversations and—equally important—because music videos are now Internet sharebait rather than broadcast TV programming. There is frequently some political subtext to these clips, and Rihanna’s career is no exception. “Man Down” told a classic story about anger after sexual assault; “Bitch Better Have My Money" was a revenge fantasy with racial and gender dimensions. “Needed Me,” directed by the provocateur Harmony Korine (Kids, Gummo, Spring Breakers) initially might seem like a content-free fetishization of violence and outlaw imagery, but actually might be her purest vision of the underlying ideology of the girls-with-guns genre yet.

Viewers don’t really learn why she’s killing the guy, though you get the sense from all the gun-wielding cast members and cool motorcycle masks that he’s a rival crime lord. The other women on display are strippers, gyrating in slow motion as Rihanna walks by with indifference. When she finds her mark, he throws a wad of cash at Rihanna as if she’s a stripper. Mistake. She points her gun and shoots him. In an arena where women are made to be subservient sexual objects, she is something else entirely. You can extrapolate about popular music and culture more broadly without too much effort.

Rihanna helps herself to the same buffet of violence, sex, and money that culture has long availed to men.

It’s not a particularly original video, though in keeping with Korine’s career, it’s hypnotic and powerfully stylized—and not at all afraid about being accused of glamorizing violence. That disinterest in sending the “right” message, in helping herself to the same buffet of righteous violence, sexual conquest, and money that culture has long availed to men, is Rihanna’s current M.O. In this, does she set a bad example? Is she contributing to America’s guns obsession? Should she take Miley Cyrus’s advice and stop playing with weaponry?

Rihanna might find the questions offensive if she appeared to care about them at all. She’s said time and again that she’s no role model, with the implication that it’s a double standard to expect her to be one. This song’s headline lyric is, “didn’t they tell you I was a savage? / fuck your white horse and a carriage.” Maybe don’t ask her to explain again.

What the Supreme Court's Ruling on Iranian Assets Means

In a rare foray into the realm of foreign policy, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Wednesday that the Iranian government must use $2 billion in frozen assets to compensate U.S. victims of terrorist attacks, rejecting Tehran’s argument that Congress had exceeded its constitutional limits by intervening in the case.

On one side of the case, Bank Markazi v. Peterson, were more than 1,000 American victims of terrorist attacks linked to Iran, as well as their surviving family members. Opposing them was the Iranian government’s central bank. The case’s namesake, Deborah Peterson, lost her brother in the 1983 truck bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon. She and hundreds of others launched a wrongful-death suit against Iran in 2001. A federal district court awarded them a $2.65 billion judgment in 2007.

While the parties argued in court about how and whether Iran would pay the judgment, Congress passed the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 2012, which included a section that made $2 billion in frozen Iranian funds available for seizure in the Bank Markazi case, citing it by name.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals, using the new law, then sided with the families in 2014 to seize the funds. In response, Iran asked the justices to intervene against Congress’ alleged encroachment on the judicial branch’s powers to decide cases. Previous Supreme Court rulings forbade Congress from forcing courts to hand down specific verdicts or reopen final judgments.

But the Supreme Court ruled Wednesday no such encroachment had taken place. “Congress, our decisions make clear, may amend the law and make the change applicable to pending cases, even when the amendment is outcome determinative,” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote for a 6-2 majority. “In accord with the courts below, we perceive in §8772 no violation of separation-of-powers principles, and no threat to the independence of the Judiciary.”

Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor in a rare alliance, strongly disagreed with Ginsburg’s portrayal of the implications. “Hereafter, with this Court’s seal of approval, Congress can unabashedly pick the winners and losers in particular pending cases,” he warned.

In a possible nod to a lay audience, Roberts outlined the ruling’s significance without legalistic terms with a hypothetical case he called Smith v. Jones.

Imagine your neighbor sues you, claiming that your fence is on his property. His evidence is a letter from the previous owner of your home, accepting your neighbor’s version of the facts. Your defense is an official county map, which under state law establishes the boundaries of your land. The map shows the fence on your side of the property line. You also argue that your neighbor’s claim is six months outside the statute of limitations.

Now imagine that while the lawsuit is pending, your neighbor persuades the legislature to enact a new statute. The new statute provides that for your case, and your case alone, a letter from one neighbor to another is conclusive of property boundaries, and the statute of limitations is one year longer. Your neighbor wins. Who would you say decided your case: the legislature, which targeted your specific case and eliminated your specific defenses so as to ensure your neighbor’s victory, or the court, which presided over the fait accompli?

Ginsburg dismissed his hypothetical as absurd. “Of course, the hypothesized law would be invalid—as would a law directing judgment for Smith, for instance, if the court finds that the sun rises in the east,” she wrote. “By contrast, §8772 provides a new standard clarifying that, if Iran owns certain assets, the victims of Iran-sponsored terrorist attacks will be permitted to execute against those assets.”

The Court’s ruling came as President Obama met with Saudi Arabia’s King Salman in Riyadh. His trip is aimed at reducing friction between the White House and Middle East nations about the White House’s attempts at rapprochement with Iran and the president’s perspective on regional security.

Why I Write Scary Stories for Children

Six years into my career as a children’s novelist, I was in need of a big story. My 100 Cupboards trilogy was off wandering the world in various translations, and I was hoping to wrap up The Ashtown Burials series the following year. And then what? Nothing. The calendar was empty. The future was blank. A new and strange uncertainty hung over my notebooks and bulletin boards.

I caught a nasty virus and went down hard, sweating and helpless with fever. The experience was as miserable as such sicknesses tend to be, right up until the increased brain heat brought me the strangest dream. By the time the fever broke and I was able to join my family at the dining room table, I had a new story ready to be pitched to my offspring.

Kids, meet Sam Miracle. He lives in a ranch outside of Tucson and he’s traumatically disabled, both mentally and physically. Sam struggles constantly with memory loss, he has daydreams of adventures in which he always dies, and his arms are so badly damaged that his elbows won’t bend.

My horrified children stopped eating and began straightening their arms in curious sympathy. So far, so good. They were gripped, breathing the heat of the desert while Sam was hunted by a San Francisco banker turned time-hopping arch-outlaw. They felt Sam’s extreme pain when his rigid arms were brutally shattered and he wavered on the edge of death. And then, when I told them how his arms were not only saved, but became faster than any arms had ever been before, they were so rapt they were barely breathing.

Two live rattlesnakes were grafted into Sam’s arms—one nice, one mean. He rattles whenever he’s surprised or scared, and his hands now have minds of their own. His right arm is out of control and perpetually distracted. His left arm wants to kill him and everything else it can reach.

Over dinner, spawned by a fever dream, Outlaws of Time was born. It’s a scary book, and the scariness is no accident. This story is a safe place that—at times—feels unsafe, a place where young readers can experience vicarious fear and practice vicarious courage, where they can watch new friends sacrifice and become heroes.

I write violent stories. I write dark stories. I write them for my own children, and I write them for yours. And when the topic comes up with a radio host or a mom or a teacher in a hallway, the explanation is simple. Every kid in every classroom, every kid in a bunk bed frantically reading by flashlight, every latchkey kid and every helicoptered kid, every single mortal child is growing into a life story in a world full of dangers and beauties. Every one will have struggles and ultimately, every one will face death and loss.

The goal isn’t to steer kids into stories of darkness because those are the stories that grip readers. The goal is to put the darkness in its place.

There is absolutely a time and a place for The Pokey Little Puppy and Barnyard Dance, just like there’s a time and a place for footie pajamas. But as children grow, fear and danger and terror grow with them, courtesy of the world in which we live and the very real existence of shadows. The stories on which their imaginations feed should empower a courage and bravery stronger than whatever they are facing. And if what they are facing is truly and horribly awful (as is the case for too many kids), then fearless sacrificial friends walking their own fantastical (or realistic) dark roads to victory can be a very real inspiration and help.

With five children of my own (currently aged between 6 and 14), I live within a perfect focus group. Like many parents and teachers and librarians, I often look into a pair of eyes and hear the question, “What should I read next?” At any given moment, a dozen books are being consumed in our home: My kids are off wandering in Narnia or Middle Earth, making friends with Anne of Green Gables and The Penderwicks, exploring “The Wingfeather Saga” or the vivid pages and volumes of Amulet. Stories are being shared, told, and revisited all the time in our house, and when I venture out on tour or into schools, I meet thousands of kids who are off on the same fictional journeys as my own.

Overwhelmingly, in my own family and far beyond, the stories that land with the greatest impact are those where darkness, loss, and danger (emotional or physical) is a reality. But the goal isn’t to steer kids into stories of darkness and violence because those are the stories that grip readers. The goal is to put the darkness in its place.

When my eldest was first reading C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia on his own (at around the age of 7), he encountered an ink illustration of the White Witch’s evil band drawn by Pauline Baynes. Cue the nightmares. He couldn’t go on reading, and every time he slept, he saw those creatures coming to life and pursuing him.

In the wee hours of one nightmarish encounter, I realized that I had two choices. On the one hand, I could begin sheltering him from every single thing that his rich imagination might magnify and enliven into terror. This was my protective paternal impulse, but it seemed as impossible as it was short-sighted. I would be facilitating the preservation of his fearfulness.

My characters live in worlds that are fundamentally beautiful and magical, just like ours, in worlds that are broken and brutal, just like ours.

My other course was to try and embolden his subconscious mind. I carried my son into my office and downloaded an old version of Quake—a first-person shooter video game with nasty, snarling aliens 10 times worse than anything drawn by Pauline. I put my son on my lap with his finger on the button that fired our pixelated shotgun, and we raced through the first level, blasting every monster and villain away. Then we high-fived, I pitched him a quick story about himself as a monster hunter, and then I prayed with him and tucked him back into bed. A bit bashfully, I admitted to my wife what I had just done—hoping I wouldn’t regret it.

I didn’t. The nightmare never shook him again.

Jump a few years and four more children. My youngest daughter (pig-tailed and precocious) was devouring all sorts of sweet little books. At her insistence, I even wrote a pair of board books just for her (Hello Ninja and Blah Blah Black Sheep) and we spent lots of time making up stories together about winged puppies. Despite all that wholesomeness, she entered a very dark period during which she was inexplicably haunted by dragons. Vivid dragons, coiling and shadowy, able to emerge from her bedroom wall with dripping jaws. For a couple of weeks, if a night passed without a nightmare, my wife and I rejoiced. We tried to track where the dragons might be coming from—fully prepared to discard whatever book or film or show might be causing such regular terror. But the root was nowhere to be found … until one Sunday at church (in a high school gymnasium) my daughter looked over my shoulder and sighed.

“Well, there’s my nightmare,” she said.

Turning, I saw it—a wriggling, snarling, slavering dragon squaring off with a mascot knight on a high school pep banner.

My relief was instantaneous. That evening, I told her one of the scariest, funniest, most violent bedtime stories ever. I got the dragon description just right, and boy, did that serpent lose big. He died for good, right along with her nightmares.

I’m not interested in stories that sear terrifying images or monsters or villains into young minds—enough of those exist in the real world, and plenty of others will grow in children’s imaginations without any help. I am interested in telling stories that help prepare living characters for tearing those monsters down.

I don’t write horror. But I do write stories about terrified sheltered kids and fatherless kids and kids with the ghosts of abuse in their pasts. Those kids encounter horrors—witches and swamp monsters, black magical doors and undying villains, mad scientists and giant cheese-loving snapping turtles. Those kids feel real pain, described in real ways. They feel real loss. They learn that the truest victory comes from standing in the right place and doing the right thing against all odds, even if doing the right thing means losing everything. Even if doing the right thing means death. My characters live in worlds that are fundamentally beautiful and magical, just like ours, in worlds that are broken and brutal, just like ours. And, when characters live courageously and sacrificially, good will ultimately triumph over evil.

As children grow, fear and danger and terror grow with them, courtesy of the world in which we live and the very real existence of shadows.

I’m not trying to con kids into optimism or false confidence. I really believe this stuff. My view of violence and victory in children’s stories hinges entirely on my faith. Samson lost his eyes and died … but he has new eyes in the resurrection. Israel was enslaved in Egypt, but God sent a wizard far more powerful than Gandalf to save His people. Christ took the world’s darkness on his shoulders and died in agony. But then … Easter.

In the end, good wins. Always.

There’s a time for amusement, for laughter and farcical tales. There’s absolutely a time for escapism and comfort and wish fulfillment (especially in the middle of a dark tale). There’s a time for sibling drama and humor and stories of shy heartbreak and school pressures. Intense and suspenseful pulse-pounding tales aren’t the one true diet for young readers. But I absolutely believe them to be healthy for growing imaginations, as essential as protein and calcium for young bones and muscles.

My children have only ever known me as a writer. When the older three still toddled, I was always plinking away on a keyboard in the corner of their playroom. By the time all five were fully aware, I was writing in an office at the end of a long attic with bunk beds tucked into dormers. Their night-light was the glow beneath my door, and when someone couldn’t sleep or a dream took a bad turn, I was the closest port in the storm. As it turns out, five children can produce worries and fears and dreams in bulk, and I’ve spent many hours fighting story with story.

In our house, when a day has brought struggle or pain or frustration, when we’ve stood at a deathbed or beside a new grave, we gather together, we sit down and listen. We assess characters and choices, villains and themes. We talk about darkness, we talk about light. We talk about loss and bittersweet victory. We talk about winter and spring resurrections. And through all of this talking, my children have learned, the most important stories are the stories we live.

The rest are all food for the journey.

Closing the Chapter on the Danziger Bridge Shootings

Five former New Orleans police officers accused of killing unarmed civilians and covering it up pleaded guilty on Wednesday, more than a decade after the incident on Danziger Bridge.

Under the plea deals, the four former officers involved in the shooting agreed to prison terms ranging from 7 to 12 years. Another officer accused of the cover-up agreed to a three-year sentence.

Those sentences are significantly less than the 38 to 65 years in prison the four former officers previously faced. A judge found that there was “prosecutorial misconduct,” and lessened the terms. By pleading guilty, the officers avoided a retrial. They were originally found guilty in 2011, and have remained in jail without bond since.

The Times-Picayune accounts for what happened that day:

The shooting occurred on Sept. 4, 2005, six days after Hurricane Katrina made landfall, as the police riding inside a rental truck said they were responding to a report of an officer on the nearby I-10 high rise taking fire from the direction of the Danziger Bridge's intersection with Downman Road. The report wasn't verified, but the resulting police action would claim the lives of mentally disabled Ronald Madison, 40, and James Brissette, 17.

Brissette was attempting to cross the eastern side of the bridge with members of his uncle's family, who were pushing a grocery cart away from the flooded city center in search of supplies. Leonard Bartholomew III, his wife Susan, daughter Lesha and Brissette's friend Jose Holmes all sustained serious injuries when the police drove up and opened fire. Only 14-year-old son Leonard Bartholomew IV, who managed to escape under the bridge, got away unharmed.

The incident added on to the already 700 dead from the hurricane. In the years that followed, the city’s police have been under heavy scrutiny, including a federal investigation, requested by Mayor Mitch Landrieu, into the New Orleans Police Department.

Harriet Tubman's Journey to the $20 Bill

The U.S. Treasury reportedly will announce Wednesday that Harriet Tubman, the African American woman who helped slaves cross into freedom, will replace Andrew Jackson, the nation’s seventh president and a slave-owner, on the front of the new $20 note.

Treasury Secretary Jack Lew also is expected to introduce several redesigns to the $5 and $10 bills that would honor other important figures in American history, including leaders of the civil rights and women’s suffrage movements, according to Politico. Alexander Hamilton will remain on the $10 bill, much to Hamilton fans’ delight; Lew floated the idea of replacing him with a woman last year.

My colleague and newsroom historian Yoni Appelbaum points out a moment in Tubman’s life that involved the $20 bill, documented by Sarah Hopkins Bradford, who wrote the first biography of the anti-slavery activist in 1869. Tubman had asked the New York abolitionist Oliver Johnson for money to help her parents, who were still held as slaves in Maryland. When he refused, Tubman camped out in his office:

“Twenty dollars? Who told you to come here for twenty dollars?”

“De Lord tole me, sir.”

“Well, I guess the Lord’s mistaken this time.”

“I guess he isn’t, sir. Anyhow I’m gwine to sit here till I git it.”

So she sat down and went to sleep. All the morning and all the afternoon she sat there still, sleeping and rousing up—sometimes finding the office full of gentlemen—sometimes finding herself alone. Many fugitives were passing through Now York at that time, and those who came in supposed that she was one of them, tired out and resting. Sometimes she would be roused up with the words, “Come, Harriet, you had better go. There’s no money for you here.” “No, sir. I’m not gwine till I git my twenty dollars.”

The redesigns will be unveiled in 2020, and the new notes would reach circulation the following decade, according to The New York Times.

1,700 People Are Still Missing After Ecuador's Earthquake

Government officials in Ecuador are now reporting 525 deaths were caused by the 7.8-magnitude earthquake that struck off the Pacific coast on April 16—but they fear the tally could climb much higher, since as many as 1,700 are still listed as missing, and recovery efforts have just begun. The strongest earthquake to hit Ecuador in decades tore up highways and knocked down hundreds of buildings in communities along the coast. Rescuers are still hoping to find survivors amid the rubble who may have been trapped for days—more than 50 have already been rescued since Saturday.

The Stakes of Beyoncé’s ‘Lemonade’

Beyoncé’s next big release is called “Lemonade,” and that’s about all the public knows about it. Last weekend an esoteric trailer announced its existence, triggering competing rumors/speculation about it being a feature-length music video, another “visual album” like 2013’s Beyoncé, a dramatic film, or a behind-the-scenes documentary. Whatever it is will be broadcast on HBO at 9 p.m. Saturday—a time slot that asks her fans to incorporate her into their going-out plans for the weekend, and that tells members of the media that if they want to skim some clicks off of Beyoncé coverage they’ll have to pull an off-hours shift (an HBO representative’s uncharacteristically mysterious reply to my inquiry about advanced screeners was, “Sorry—there is nothing available to screen.”).

What seems likely is that “Lemonade” will be another effort in Beyoncé’s ongoing reinvention of celebrity best practices, and that it would be unwise to bet that it won’t be an effective one.

Until a month ago, the last time Beyoncé gave a traditional face-to-face interview with a print journalist was for the January 2013 edition of GQ, which revealed that her Manhattan office features a “long, narrow room that contains the official Beyoncé archive, a temperature-controlled digital-storage facility that contains virtually every existing photograph of her.” At the time, this revelation was greeted with a certain amount of horror—the sign of a Type-A narcissist, the kind of thing fabricated for literary satires of the digital era—and perhaps that negative reaction was the reason she stopped sitting for profiles.

But now the GQ article now seems like a fitting, perhaps intentional, farewell to traditional media. Amy Wallace’s story included lengthy quotes about Beyoncé’s self-critical tendencies—she watches footage of each of her concerts to write feedback notes to her crew the next day—as well as her desire for the kind of independence that pop stars rarely achieve. “When I was writing the Destiny’s Child songs, it was a big thing to be that young and taking control,” she said. “And the label at the time didn’t know that we were going to be that successful, so they gave us all control. And I got used to it. It is my goal in life to be that example.” The control she referred to was not only about creating her own art; it was taking charge of its distribution and marketing, too. She showed off her exhaustive personal archive to inform the press that she’d found a better way of promoting her work—all your pesky questions can go in a box to the left.

Beyoncé was influential then—GQ’s headline: “Miss Millennium”—but few could have guessed how much more influential she would become. A self-produced documentary for HBO, an impeccable Super Bowl show, and the unannounced and hugely acclaimed Beyoncé release—featuring an elaborate music video for each of its songs—followed. After a relatively quiet 2015, this year has seen a new surprise in the single “Formation,” which promoted another Super Bowl performance, another quickly sold-out tour, and a clothing line further bolstered by an Elle story touted as her first major interview in years—though it was conducted by what appears to be a handpicked member of the inner Beyhive. All of these maneuvers have asserted that Beyoncé is her own media machine capable of directly addressing the public, have savvily used controlled scarcity to maintain her ubiquity, and have breezed past distinctions between music, visuals, commerce, and art.

But the hype for “Lemonade” also owes to a yet more crucial part of Beyoncé’s appeal lately, which is her consistency. Anytime a chorus of “yaaaas” breaks out following a Beyoncé action, there’s typically a counter-chorus of people wondering if the praise is all sycophancy. It’s not. The way each frame of the “Formation” video offered a viscerally arresting image but invited further analysis for meaning—and triggered debate on topics typically outside the bounds of popular music—is typical. The song itself, which cuts through rest of what’s on the radio and takes a few listens to fully unveil its glorious pop potential, also demonstrates Beyoncé’s expert sense for how to balance novelty with familiarity. There are few if any other mega-musicians today who reliably serve up such a satisfying product every time they release something.

Which means there’s risk in her decision to let the public’s imagination run wild about “Lemonade” for a week. There’s potential for a masterpiece; deliver much less, and her brand could take a serious blow. The rumor that “Lemonade” will be a behind-the-scenes documentary like Beyoncé’s last HBO production, 2013’s Life Is But a Dream, would seem dubious based on the trailer alone—as far as anyone can guess, there are not sudden explosions behind the scenes of Beyoncé’s life. The safer bet, I think, is that Saturday’s broadcast will indeed be an “album” of music videos, and the fact that any album could conceivably be “released” on HBO would be an innovation that suits the great category-collapsing celebrity of our era. It’s not TV, it’s not music, it’s Beyoncé.

Documenting Los Angeles’s Near-Invisible Workers

A man pushes a lawn mower through an expanse of green. A woman scours a tall, tiled shower. A man cleans a large pool as another washes the windows of a modern looking house, framed by two palm trees.

These subjects are usually in the background of the luxurious California landscapes they help maintain, but the artist Ramiro Gomez uses his brush to document their existence, memorializing them in the midst of their work. By emphasizing the hidden labor that sweeps and polishes and scrubs, Gomez reframes the David Hockney paintings and glossy magazine advertisements he takes for inspiration, putting the lives of California’s near-invisible and individually disposable workers front and center.

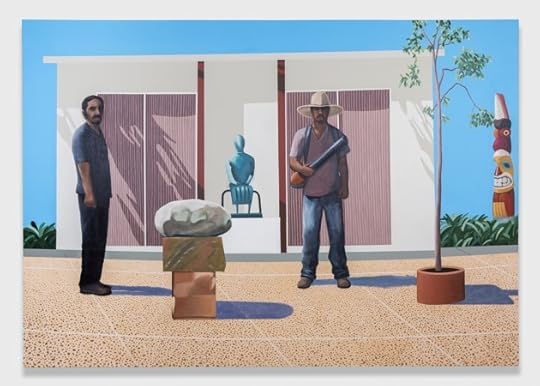

American Gardeners (after David Hockney’s American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman), 1968), a revised David Hockney painting (Ramiro Gomez)

Gomez, who was born in San Bernardino, California, to two then-illegal Mexican immigrants, found his subjects when he began working as a nanny for a family in Los Angeles. The other domestic employees would soon feel like a new family for him within a strange home, until suddenly they’d be gone, replaced without notice. “I felt an impulse to document these fleeting moments of their labor and existence, not knowing when or if they'd return,” Gomez said.

Gardener, North Beverly Dr., Beverly Hills, a cardboard cutout (Ramiro Gomez)

Now collected in the book Domestic Scenes: The Art of Ramiro Gomez with writing by Lawrence Weschler, Gomez’s work crosses media but returns to this same preoccupation. His cardboard cutouts of outdoor laborers and nannies that Gomez leaves around various parts of L.A. force passersby to notice the workers who maintain the city’s lawns and take care of the city’s children. “I wanted to slow people down, to have them double take, to make them take notice and see,” he tells Weschler in the book’s opening essay. “It was strange: Actual humans involved in their labor had become invisible to most people, but the image of a human, there, in the middle of your day, and not at some museum or gallery, but there in the middle of your path, somehow that registered.”

Valentin Cleaning the Pool, a painting on a magazine advertisement (Ramiro Gomez)

Gomez’s reimaginings of the British painter David Hockey’s beatific and serene California scenes, which insert the men and women in the act of creating them, have garnered critical acclaim, especially his revision of Hockney’s iconic “A Bigger Splash.” His painted reinterpretations of advertisements, the first project that he began while working as a nanny, feature the housekeepers and gardeners whose hands wipe and dust and wash the plush upholstery, cool granites, and dreamy garments of idealized domestic life. And his photo studies depict casual moments of labor—Gomez stops to photograph the menial workers he sees, his camera a means of recognition. He finds beauty, he says, in the domestic work environment—beauty that he doesn’t see reflected in the “advertisements or cultural products that surround us.”

DVF, a painting on a magazine advertisement (Ramiro Gomez)

Gomez’s figures are faceless, but he gives them names: Lupe, Eduardo, Abelina, Nemesio, Grizelda. He tells Weschler that this is “to suggest the way they were taken for granted and overlooked, but in part also because somehow the viewer reads more into them that way”—a tactic to inspire empathy, born from his own observations.

Estela and Dylan, a painting on a magazine advertisement (Ramiro Gomez)

At its heart, his work is a means of acknowledgment and documentation—of his own experience, of the overlooked lives around him, of his family’s history, of the immigrants who keep Los Angeles running smoothly but whose labor evaporates into the smog. “When a child is helped raised by a nanny ... the nanny's contribution becomes difficult to measure,” he said. “It puts things in perspective to understand that the times we are living in will only be viewed through those physical remnants which survive.”

Las Meninas, Bel Air, a cardboard cutout (Ramiro Gomez / David Feldman)

While Gomez acknowledges the political dimensions of his work, he also stresses that his art uses a quieter, more measured approach, focusing on humanizing his subjects in a way that is easy to understand.

“Paintings say what words often can’t,” he said. “They have the ability to reach into the hidden spaces within from which we view the world. What I am painting about isn't anything new—it’s in fact very familiar, immediately recognizable to everyone without getting lost in translation. Labor is everywhere, the cast is different, but the role is the same.”

April 19, 2016

Sentencing for Peter Liang

Former New York Police Department officer Peter Liang won’t spend a day in prison.

Liang, who was convicted in February of manslaughter and official misconduct in the shooting death of an unarmed black man in 2014, was sentenced Tuesday to five years of probation and community service after the judge in the case reduced his conviction from manslaughter to criminally negligent homicide moments before sentencing.

A New York jury had convicted Liang of manslaughter in February for killing Akai Gurley, who had walked into a housing complex stairwell. Liang was the first NYPD officer in more than a decade convicted of an on-duty killing. Critics of the verdict said Liang had been offered up as an Asian scapegoat though, for years, white officers had done worse, and gotten away with it.

During his trial jurors repeatedly asked to touch Liang’s gun, even pulling the trigger for themselves; Liang, who never confronted Gurley, had said his finger accidentally jerked the trigger when he was surprised by a loud sound.

Liang and his partner were patrolling the Louis H. Pink Houses in November 2014. The two opened a door to a dark and unlit stairwell on the eighth floor and Liang drew his gun. Liang said a loud noise surprised him and his gun accidentally fired. The bullet ricocheted and struck Gurley, who was walking down the stairs about a flight below with his girlfriend.

Liang later said he didn’t know anyone had been shot, so he and his partner, Shaun Landau, stepped outside into the hallway and debated who would call and tell their superior that the gun had been discharged. Meanwhile, Gurley had made it to the fifth-floor and lay bleeding. It was only when Liang stepped back into the stairwell to find the bullet that he and his partner heard Gurley’s cries. But even then, Liang didn’t offer help.

Liang had graduated from the police academy a year before. His partner would later testify that neither had received appropriate CPR training, and officials running the school had even fed them answers on the exam. Gurley’s girlfriend, who had to run for neighbors to ask for phone to call 911, performed CPR while an operator coached her. For that, Liang was charged with official misconduct. The rest of his charges included second-degree manslaughter, criminally negligent homicide, second-degree assault, and reckless endangerment.

Liang faced 15 years in prison for the manslaughter charge, but there was little chance he’d receive such a harsh sentence. In March, the Brooklyn district attorney’s office said it would not seek prison time for Liang, and instead asked he be sentenced to five years probation, with six months of home confinement. Of the recommendation, prosecutor Ken Thompson said that “from the beginning, this tragic case has always been about justice and not about revenge.”

It was not the news Gurley’s family wanted to hear. In a statement they released shorty after, the family said, “We are outraged at District Attorney Thompson’s inadequate sentencing recommendation. Officer Liang was convicted of manslaughter and should serve time in prison for his crime. This sentencing recommendation sends the message that police officers who kill people should not face serious consequences.”

Gurley’s death came just four months after the death of Eric Garner, another unarmed black man killed by police (though no one was charged in that instance). And the case came after a year when police shootings of unarmed black men led to protests in cities across the U.S.––in Ferguson, Missouri, Baltimore, Maryland, Chicago and New York.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower