Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 113

July 27, 2016

Trump's Plea for Russia to Hack the U.S. Government

Just when it starts to seem that Donald Trump can’t surprise the jaded American media anymore, the Republican nominee manages to go just a little bit further.

During a press conference Wednesday morning that was bizarre even by Trump’s standards, he praised torture, said the Geneva Conventions were obsolete, contradicted his earlier position on a federal minimum wage, and told a reporter to “be quiet.”

But the strangest comments, easily, came when Trump was asked about allegations that Russian hackers had broken into the email of the Democratic National Convention—as well as further suggestions that Vladimir Putin’s regime might be trying to aid Trump, who has praised him at length. Trump cast doubt on Russia’s culpability, then said he hoped they had hacked Hillary Clinton’s messages while she was secretary of state.

“By the way, if they hacked, they probably have her 33,000 emails,” he said. “I hope they do. They probably have her 33,000 emails that she lost and deleted. Because you’d see some beauties there.” A few minutes later, he returned to the idea, speaking directly to the Kremlin: “I will tell you this: Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing.”

It was a stunning moment: a presidential nominee calling on a foreign power not only to hack his opponent and release what they found publicly, but hoping the Russians had stolen the emails of a top American official, perhaps including classified information.

Following Trump’s thread on Russia was practically impossible. On one hand, he portrayed the act of hacking into Democratic emails as “a total sign of disrespect,” yet in the next breath he pleaded with foreign powers to do just that. He said he was “not going to tell Putin what to do.” He also insisted, “I have nothing to do with Putin. I don’t know anything about him, other than he will respect me.”

Trump previously claimed a friendship with the Russian president. “I got to know him very well because we were both on 60 Minutes, we were stablemates,” he said. That was later revealed as a lie: Although both men were on the same episode of the show, they had never met.

Trump has given conflicting signals about his connections to Russia elsewhere, too. On Tuesday, a spokeswoman told Newsweek that he had no business with the country. In 2008, however, Donald Trump Jr. said that “Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets … We see a lot of money pouring in from Russia,” as The Washington Post reported.

Trump struck a balance Wednesday, insisting that Putin was a strong leader but tempering his praise. In one of the odder moments, Trump charged Putin with racism and then immediately said he hoped Putin would like him.

“Putin has said things over the last year that are really bad things, okay. He mentioned the ‘n’ word one time. I was shocked to hear him. You know what the ‘n’ word is, right? Total lack of respect for President Obama. Number one, he doesn’t like him. Number two, he doesn’t respect him. I think he’s going to respect your president if I’m elected, and I hope he likes me.”

He has less affection for France, where Islamist terrorists killed a priest on Tuesday. “I wouldn’t go to France,” Trump said. “I wouldn’t go to France, because France is no longer France.”

What if Clinton or Obama had wished that a foreign power had hacked a political opponent’s emails?

For an ordinary candidate, that would been extraordinary enough of a press conference. But Trump was barely getting started. NBC’s Katy Tur asked him point-blank whether he believed the Geneva Conventions were out of date.

“I think everything’s out of date. We have a whole new world,” Trump said. He then reaffirmed his support for torture, even though there’s no evidence it’s an effective intelligence-gathering tool. “I am a person that believes in enhanced interrogation, yes. And, by the way, it works.”

He launched into a tirade against Clinton’s running mate, Senator Tim Kaine of Virginia. But Trump repeatedly accused Kaine of trying to raise taxes while governor of New Jersey. He was eventually corrected; it was unclear what caused the slip, although some reporters noted the similarity between Kaine’s name and former Governor Tom Kean (whose name is pronounced “cane”) of New Jersey.

Trump’s flip-flop on his relationship with Putin was not the only reversal. In May, Trump said he wanted to abolish the federal minimum wage. On Wednesday, he gave a somewhat confusing answer, saying, “I would like to raise it to at least $10,” yet also suggesting that perhaps states rather than the federal government should do that.

Just for good measure, Trump threw in a shot at Obama, who is scheduled to speak at the Democratic National Convention Wednesday evening. “I think President Obama has been the most ignorant president in our history,” he said. “When he became president, he didn’t know a thing. And honestly, today he knows less.”

By the end, Wednesday’s press conference made Trump’s weird speech on Friday seem positively quotidian. These sorts of outbursts are the kinds of things that are disqualifying for most candidates. It’s hard to imagine what would happen if Clinton or Mitt Romney or Obama had publicly wished that a foreign power had hacked a political opponent’s emails—especially a cabinet secretary. But Trump’s supporters have been unbothered so far. As Trump gleefully pointed out during the press conference, several recent polls show him leading Clinton. Who knows what inspired Trump to spout off on Wednesday, though. With the DNC in full swing, perhaps he just couldn’t bear to surrender attention to the Democrats any longer.

The Glorious Panic of a Radiohead Concert in 2016

Radiohead’s first American show in four years was terrifying. Throughout the band’s two hours and 15 minutes on stage at New York’s Madison Square Garden on Tuesday, my mind fixated on violence, death, and the end of the world, which means it was a very good Radiohead concert.

The set began with a version of "Burn the Witch" shorn of the dazzling string arrangement it has on this year’s A Moon Shaped Pool, and of any trace of cuteness once created by its disturbing/winsome stop-motion music video. Rather than orchestral pop, the band played the song as lean, furious rock while bathed in red light. It’s long been agreed that “Burn the Witch” is about paranoia pushing civilization to savagery, but the message seemed particularly urgent with this arrangement and, perhaps, in this context. After the Bataclan attack, after Orlando, after Nice, attending a sold-out concert—or any packed entertainment gathering—means knowing exactly what, in Yorke’s words, a “low-flying panic attack” feels like. It means realizing that when he sings “abandon all reason / avoid all eye contact / do not react / shoot the messenger,” he’s giving voice to a primal and dangerous impulse that’s at issue in this election, an impulse that has fascinated Radiohead for decades.

Previous Radiohead tours have featured forests of LED columns, or glowing shards hanging like chandeliers. But last night’s visuals consisted of a relatively simple, symmetrical array of lights and screens above and behind the band. Sometimes, they strobed in chaotic or gorgeous patterns. But between songs, the house lights would go up on stage as the band members traded instruments, breaking whatever spell the previous tune had cast. The muted visuals and discrete borders between performances had an intensifying effect on the music itself. We were being asked to consider Radiohead’s work on its own terms, not through the lens of arena spectacle.

Doing so means marveling at just how steady Yorke’s preoccupations have been over two and a half decades. Here are lyrics from 1995’s “Planet Telex,” performed with even greater volumes of U2-esque guitar echoing last night: “Everything is broken.” From 2003's “2+2=5”: “It is too late now / because you have not been paying attention,” sung as the band exploded in demented surf-rock. From 2016's slow, swirling lullaby “Daydreaming”: “Beyond the point / Of no return … It’s too late / The damage is done.” The subjects are always vague, but the sentiment is always clear: you, me, and everyone else have made a terrible, irreversible mistake. In a year like 2016—when people are making comparisons to some of the worst years in world history for comfort’s sake—this does not feel like idle fretting.

Early in the show, the new album’s “Decks Dark” made the gathered masses slowly sway as Yorke sang about the inevitable day when you—it’s in the second person—die. Soon after, the band entered rhythmic mania for “Ful Stop” as Yorke keened, “You really fucked up everything this time,” triggering a descent into one of the signature sonic modes of Radiohead’s career: glitchy workouts with deep, rumbling bass lines, embodied in tracks like “15 Step” and “Lotus Flower.” Live, these songs are totally transfixing body movers, none more than “The National Anthem,” which thundered onto stage with EKG visuals and audio snippets of news coverage of the Democratic National Convention. “Everyone around here has got the fear,” Yorke sang, correctly, despite the fact that the concert had opened with a sample of Nina Simone saying “I'll tell you what freedom is to me: No fear. I mean, really—no fear."

“No alarms and no surprises, please”—a prayer before checking a news app these days, no?

Don’t misunderstand: Within the arena, the concert was not received as a horror show. There were bros in front of me and behind me jumping and gesturing along with every anxious crescendo, every fractured break-beat, as they should have been. Despite their latter-day reputation for cold electronica, Radiohead came across like a true rock band, employing two drummers and four guitarists at many times as Yorke frequently smiled and pointed at the audience. New songs like “Tinker Tailor Soldier Sailor Rich Man Poor Man Beggar Man Thief” and “Desert Islands Disk” achieved a pleasingly placid aura, and the classic-rock shamble of “The Numbers” offered a reminder that there may be some glimpses of hope in Radiohead’s worldview: “The people have this power / The numbers don't decide” before the song transforms from rippling puddle to tidal wave.

Yet it was the band’s older material that connected most readily, especially aching fan-favorites from the ‘90s like “Let Down” (its first appearance in concert since 2006) and the set-ending elegy “Street Spirit.” Tracks from 2003’s Hail to the Thief, an airing of Bush-era frustration that saw somewhat mixed reception at the time of its release, were surprising highlights—the cathartic eruption of “2+2=5,” the heavy boogie of “Myxomatosis.” Most bizarre was seeing the Kid A tone poem “Everything In Its Right Place” become a buoyant singalong, with maraca sounds used for dance rather than for incantation.

But even the crowd pleasers carried a sense of dread somehow yet-sharper than the one on the band’s recordings. “Paranoid Android” had the entire arena joining in for a sarcastic sneer of “god loves his children, yeah” before the song’s final rock-out. And for “No Surprises,” the audience erupted in cheers for the lines “bring down the government / they don’t speak for us,” but, again, it was hard not to be unsettled by the song’s greater resonance: “No alarms and no surprises, please”—a prayer before checking a news app these days, no? At one point, in fact, the band did conjure something very similar to the sound of an actual alarm for the glorious freak-out at the end of “Idioteque.” “We’re not scaremongering / this is really happening,” Yorke had sung, but thankfully, in that moment, the communal nightmare was being rendered only in music.

The End of the Freddie Gray Prosecutions: No Convictions

Updated on July 27 at 4:20 p.m.

In April 2015, a 25-year-old black man in Baltimore named Freddie Gray was arrested on questionable grounds and thrown into a police van. By the time he arrived at the county jail less than an hour later, his neck was nearly severed. After a week in a coma, Gray died. His death set off mass demonstrations and a few riots in Baltimore, and they galvanized the police-reform movement: How could a man who posed no threat to the police have been killed while in police custody? To many observers, the case seemed like a clear-cut example of police brutality that called out for criminal prosecution, and Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby quickly brought a strong slate of charges against six officers.

Yet it now appears that no officers will be convicted in Gray’s death. After the first trial ended in a hung jury and the next three produced acquittals, prosecutors in Baltimore abruptly dropped charges against three remaining officers in Gray’s death on Wednesday morning. The trial of Officer Garrett Miller was supposed to begin Wednesday.

In a scorching news conference on Wednesday, Mosby defended her decision to pursue cases against the officers.

“As prosecutors, we are ministers of justice, and it is our ethical obligation to always seek justice over convictions,” she said. “Although no small task, justice is always worth the price paid for its pursuit.”

She complained that she and her staff had been “physically and professionally threatened, mocked, ridiculed, harassed, and even sued,” but added:

I was elected the prosecutor. I signed up for this and I can take it. Because no matter how problematic and troublesome it has been for my office, my prosecutors, my family, and me personally, it pales in comparison with what mothers and fathers all across this country, specifically Freddie Gray’s mother, Gloria Darden, or Freddie Gray’s stepfather, Richard Shipley, goes through on a daily basis.

Miller was the fourth officer scheduled to go on trial. The first, William Porter, saw his trial end in December with a hung jury, and until Wednesday, prosecutors had vowed to retry him. The following three trials—including that of Officer Caesar Goodson, who faced the most serious charge, of second-degree depraved-heart murder; Officer Edward Nero; and Lieutenant Brian Rice—all ended with acquittals.

Prosecutors’ failure to secure a conviction in the case, despite the details of Gray’s death, points to two realities about prosecuting police in brutality cases, one national and one local. First, it underscores the difficulty of prosecuting police. Nationwide, relatively few officers are charged with crimes in cases where civilians are killed, and even fewer are convicted. District attorneys are reluctant to bring charges against police because they depend on them for testimony in other cases, and juries tend to be deferential to cops.

The Baltimore case was supposed to be different, for several reasons. First, Mosby had moved quickly and decisively to charge the officers, which won her praise from reformers but worried an unusual coalition of police advocates and critics of prosecutorial overreach. Second, the Gray case seemed superficially simple: A healthy man entered a police van and was mortally wounded in police custody. How could a crime not have been convicted? Third, Baltimore juries were expected to be unsympathetic to the police.

Other than Porter, however, officers opted for bench trials, forgoing their right to a jury and putting their fate in Judge Barry Williams’s hands. Meanwhile, prosecutors were unable to produce the evidence they needed to show that police had intentionally hurt Gray, or had even been negligent. Although they argued in Goodson’s trial that Gray had been given a rough ride (the idea that officers intentionally banged him around in the van—not implausible, given a long history of rough rides in Baltimore and elsewhere), Williams scolded them for making incendiary allegations without evidence. Other parts of their cases relied on novel legal theories, charging police for behavior that, while perhaps distasteful, has seldom or never been prosecuted.

After going 0-3-1 through four trials, prosecutors apparently recognized that they were going nowhere. (There were particularly sharp challenges in the Miller case, as The Baltimore Sun explains.) Mosby has come in for sharp criticism, including some calls for her to be disbarred. It’s an ironic denouement: A prosecutor who presented herself as vanquishing a heavy-handed criminal-justice system is now portrayed as an exemplar of it.

During her press conference Wednesday, Mosby said there is “an inherent bias when police police themselves” and she accused police officers of sabotaging her case: placing officers who were witnesses on the investigation team, failing to ask tough questions, and being “completely uncooperative” and launching “a counterinvestigation to disprove the state’s case.” It’s not immediately clear what Mosby is referring to. She has been under a gag order on the case, and she did not take questions, citing civil suits against her.

For advocates, the Gray trials are perhaps not a total loss. David Jaros, a law professor at the University of Baltimore, told me in June that the trials had done an important service in putting allegations of brutality into the public record, even where there wasn’t evidence to convict.

“We have ample evidence that rough rides are occurring, even if there wasn’t a rough ride in this case. We have the state’s attorney acknowledging for the first time that police routinely grab people on the street, throw them up against the wall without probable cause, and search them,” he said. “How are we going to stop this egregious behavior?”

For Jaros, the answer was that police reform requires a broader effort, not one that relies on the criminal-justice system to change behavior around the margins. Prosecutors’ surrender on Wednesday seems to validate the need for reformers to look elsewhere.

As for the Gray family, it settled with the city of Baltimore for $6.4 million last fall. But a big payout doesn’t bring Freddie Gray back, and as the families of other people who died at the hands of police have noted, it’s not the same as justice, either.

July 26, 2016

The Fragile Unity of a Nation Under Attack

Sometimes what it takes to bring a country together is one horrific terror attack. But bringing a country together and keeping it together are two very different things.

France is reeling from yet another terror attack Tuesday—this time the horrific murder of an 85-year-old Catholic priest, claimed by ISIS, and committed just as mass was ending at a church in St.-Étienne-du-Rouvray, a town in Normandy. The attack is all the more appalling because, according to Le Monde, one of the suspected attackers, Adel Kermiche, was already under electronic surveillance after attempting to reach Syria, twice.

Already, the attack has brought fresh scrutiny for the deeply unpopular President Francois Hollande. The French leader has presided over some of the most sweepingly emotional moments in recent French history, triumphantly and defiantly leading a multinational, multifaith parade after the Charlie Hebdo attacks last January and again winning praise for his leadership after November attacks in Paris. Yet he is now president of a divided, fractious nation, one that doesn’t trust his leadership and is slumping toward the semi-fascism of the National Front. Hollande is the latest leader to see a terror attack bring a rattled nation together in intense unity, only to have that brief feeling of togetherness dissolve in the aftermath, whether due to unrealistic expectations from the public, botched policy by the government, or some combination of these and other factors.

The classic example is President George W. Bush. Though Bush had been elected by the skin of his teeth, the September 11 attacks less than a year into his term produced an outpouring of cohesion, patriotism, and resilience that turned Bush into a beloved figure stateside, and the United States earned the world’s sympathy. But over the following few years, Bush gradually frittered that away. The biggest error, of course, was the war in Iraq, which quickly proved to be ill-conceived, ill-executed, and destabilizing for the region. There were other steps, though, including the creation of a large security state, from the Patriot Act to questionably legal wiretaps to dubiously constitutional detention of suspects. Despite the (ahistorical) protestations of Bush loyalists that “he kept us safe,” Americans began to lose faith in his administration. Bush was able to win reelection in the hard-fought 2004 campaign, but the country was deeply polarized, and has remained that way. By 2006, Bush was a pariah; by the presidential elections of 2008, he mostly avoided the campaign trail, lest he hurt GOP nominee John McCain. It didn’t help, and McCain lost.

Bush’s arc, from massive popularity to historic disapproval, took several years, but then the United States always does things on a large scale. In Britain, Prime Minister Tony Blair compressed the timeline after the July 2005 London bombings, which killed 52. Blair’s approval ratings had fallen, in part due to his eagerness to join the American attack on Iraq, but the 2005 attacks rallied the country around him, and his popularity spiked—for what would turn out to be the last time in his long tenure. Blair, like Bush, overreached in his response, proposing sweeping new terrorism laws. “Let no one be in doubt,” he said. “The rules of the game have changed.” But Parliament balked, voting them down—his first defeat in the Commons. Within a year, he was forced to step down by his own party in favor of Gordon Brown.

The pattern isn’t universal. For example, Spain’s Partido Popular was unceremoniously defeated in elections just three days after the bloody 2004 attacks at Madrid’s Atocha Station. But it makes intuitive sense that in times of fear, citizens would rally around their leaders. It also makes some intuitive sense that leaders, being fallible, would often bobble and drop that precious resource.

Hollande must feel a bit like he’s trapped in a Groundhog Day-style look: attack, popularity, decline. Before the January 2015 attacks on the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket, Hollande’s favorability was already ailing. But those attacks did for France and for its president something like what 9/11 did for Bush, delivering unity at home and sympathy abroad. His response was widely praised, and his approval rating doubled.

The problem is what has happened since. Like Bush and Blair, he doubled down on bellicosity, announcing expanded operations in the Middle East. (Terror attacks pose an intractable dilemma for national leaders: Should they pull back from overseas, and risk looking like they’re cowed, or expand foreign involvement at the risk of overstretching with no strategic benefit?) Unlike Bush and Blair, Hollande started out with a pitifully low approval rating, and unlike them, he has faced a continuing spree of Islamist attacks inside his country’s borders: the January 2015 attacks on Charlie Hebdo and the kosher supermarket, November 2015 Paris attacks, the killing of two married police officers in June 2016, the July 14 attacks in Nice, and now the murder of the priest in St.-Étienne-du-Rouvray.

Hollande saw a bump in approval after the November Paris attacks and again after the Nice massacre. Overall however, his ratings remain at stunning lows. Just 12 percent said he was doing a good job in a poll in early July. Those short bursts of unity aren’t doing much to help him.

What’s going wrong? Perhaps French people, like people the world over, have somewhat unrealistic expectations for how safe the government can keep them. Stopping terrorist attacks, even with a high-quality intelligence system, requires a great deal of luck. Successful attacks aren’t necessarily evidence of negligence or failures, and lack of attacks doesn’t necessarily mean the intelligence and policing are doing a great job. Prime Minister Manuel Valls is calling for forbearance today.

“I understand this feeling of helplessness, but if the French people absorb this truth that it is a long war which will require resilience and resistance, we need to form a block and stay united,” Valls said. “For months we knew there would be new attacks, and everything is still being done to eradicate this terrorism in Syria and Iraq, and of course in France, but there are hundreds of radicalized people.”

But pleas like this start to sound hollow in the case of attackers whom authorities were supposedly already watching. Many of the Paris attackers were known to counterterror officials, just like Adel Kermiche. Although suspects can’t be arrested for Minority Report-style “pre-crime,” the St.-Étienne-du-Rouvray attack seems, from early accounts, to have been the result of a serious oversight.

The pattern is also evidence that if the goal is to foment political instability, terrorism can sometimes be an effective strategy. In the aftermath of attacks, leaders and citizens alike offer an immediate refrain about the importance of unifying in order to deprive the terrorists of what they want. Over time, however, people begin to forget, or grow skeptical of, that admonition, and leaders have time to make errors and undermine themselves. More broadly, leaders tend to eventually become unpopular over time in any case, and governments tend toward political entropy.

Perhaps the simplest explanation for the pattern of unusual unity followed by increasing strife is this: Moments of national crisis bring citizens together in the immediate aftermath, but they also offer a chance to ask: Can’t we do better than this?

The Lost 16th-Century Spanish Fort in South Carolina

NEWS BRIEF Using remote sensing technologies, U.S. archaeologists have unlocked a lost piece of early North American history—all without actually digging.

The fort of San Marcos, located in present-day Parris Island, South Carolina, was one of five forts that existed in 1577 in the Spanish colonial town of Santa Elena, the remains of which were first uncovered almost 40 years ago. After two years of research, Chester DePratter of the University of South Carolina and Victor Thompson of the University of Georgia were able to uncover the missing fort by employing ground-penetrating radar, soil testing, and monitoring magnetic fields to detect the landscape of the ancient settlement.

The 16th-century fort was part of one of the oldest Spanish settlements in the Americas, built by Spanish military officer Pedro Menedez Marquez in order to curb French expansion in the New World. Marquez constructed the fort in six days to defend the settlement against potential attacks from Native Americans. Though there were documentary sources proving the fort’s existence, previous attempts to locate it through archaeological excavation were unsuccessful.

“I have been looking for San Marcos since 1993, and new techniques and technologies allowed for a fresh search,” DePratter said in a press release Monday. “Pedro Menendez didn’t leave us with a map of Santa Elena, so remote sensing is allowing us to create a town plan that will be important to interpreting what happened here 450 years ago and for planning future research.”

The archaeologists say the discovery, which currently sits beneath a former military golf course, will allow them to better understand the land’s history, and the European powers’ competitive expansion that helped shape it.

Japan's Deadliest Attack in Decades

NEWS BRIEF At 2:10 a.m. Tuesday morning, 26-year-old Satoshi Uematsu broke through a window of a facility for the disabled in Sagamihara, Japan, and went on a stabbing rampage that killed 19 of the 150 patients in the facility, wounding 25 others. Among those killed were 10 women and nine men, ranging from 19 to 70 years old, according to the Associated Press.

Less than an hour later, Uematsu turned himself into police. The attack is the deadliest mass killing Japan has seen in decades.

The facility, Tsukui Yamayuri-en, was not unfamiliar to Uematsu. He began working there in 2012, and reportedly held a grudge against the facility for firing him last February. According to Kanagawa prefecture officials, the facility employs more than 200 people, though only nine of them were working on the night of the attack—a staffing shortage that Uematsu would have foreseen, according to Japanese media.

Though little is known of Uematsu’s background, the Japanese Parliament office told the AP that he attempted to deliver a letter to a local legislator in February, outlining his intentions of committing an attack on two facilities. In the letter, he called for “a revolution,” demanding that all disabled people be put to death through “a world that allows for mercy killings.” He further demanded that he be declared innocent on the grounds of insanity, given 500 million yen ($5 million) in aid, and receive plastic surgery.

Uematsu may have suffered from mental illness, with some reports saying he had been released from a psychiatric hospital six months ago. But attacks such as these are ultimately rare in Japan, which experienced only three mass killings in the past 15 years. Some have attributed this to the country’s strict gun control laws.

Nevin Thompson explained why in Quartz Tuesday:

Annual statistics compiled by Japan’s National Policy Agency show there was only one gun-related death in 2015 in Japan (link in Japanese), and six in 2014. In contrast, at the other end of the spectrum, there were between 11,000 and 12,000 homicides with guns in the US in 2014.

What reasons are behind Japan’s low homicide rate, especially those murders involving guns? For one thing, gun ownership in Japan is very rare. There are just 0.6 firearms per 100 people in Japan, compared to 88.8 in the US. But as the Sagamihara, Akihabara and Osaka massacres demonstrate, if an assailant wants to kill people, they do not need a gun to do so. But if there were 372 mass shootings in the US in 2015, why didn’t Japan have a similar number of knife massacres that year?

Japanese authorities arrested Uematsu on charges of attempted murder and unlawful entry. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe expressed his condolences in a statement Tuesday, saying, “The lives of many innocent people were taken away and I am greatly shocked. We will make every effort to discover the facts and prevent a reoccurance.”

It's a Bird, It's a Plane, It's a Delivery Drone

NEWS BRIEF Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon, said in 2013 he dreamed that soon the packages his online company shipped to homes across the world would be delivered by drones. Amazon was founded in the U.S., which is also its largest market, but there the federal aviation regulations would not allow for drone delivery.

On Monday, Amazon announced it had come to an agreement with the British government that eased laws enough to allow Amazon to test its drone-delivery system. The deal will allow operators to pilot the machines beyond the line of sight, to test automatic obstacle-avoidance technology, and to see if one person can safely pilot multiple drones simultaneously.

Under the new agreement, Amazon can test drones carrying deliveries that weigh up to five pounds, which makes up 90 percent of the packages the company delivers. Drones are also restricted to flying below 400 feet.

Typically, the British government’s regulations on drones are not that different from those in the U.S., as The Guardian reported:

Beyond special testing scenarios such as that granted to Amazon, current UK legislation dictates that drones cannot be flown within 50 metres of a building or a person, or within 150 metres of a built-up area. Drones also have to remain in line of sight and within 500 metres of the pilot, which has hampered attempts to use drones for delivery or surveillance purposes before.

But in the U.S., the Federal Aviation Administration has repeatedly denied drone makers who have lobbied to ease restrictions enough for drone delivery. Those lobbyists have argued it would cut down on transportation costs. In June, the FAA allowed for commercial drone use for machines under 55 pounds as long as the operator passed a written test, piloted the drone during the day, and the machine stayed within eyesight. That last regulation has been a deal breaker when it comes to drone delivery.

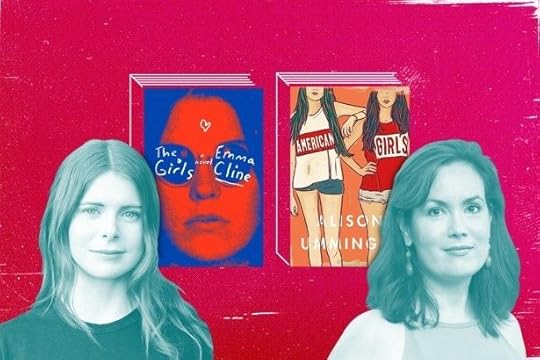

Charles Manson, the Girls, and the Banality of Desire

The most fascinating part of the Manson story has always been the girls.

Not the man who cobbled together bits of hippie philosophy, Scientology and How to Win Friends and Influence People to gather followers who’d do his bidding and help make him a star (and when that didn’t work out, kill people to try to start a race war). The ones willing and vulnerable enough to be gathered. Who wanted a community to belong to.

Even now, no one knows whether Charles Manson believed his own insane manifesto, or was just using it as a tool to get what he wanted. But the girls believed. Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie Van Houten, Susan Atkins—they believed. They belonged. And then, on two infamous evenings in 1969, they helped kill seven people.

Their stories have long been sidebars to Manson’s—when they’re mentioned, it’s as depraved killers or helpless pawns in his game, or both. Until now, I’d never read something that attributes them motives that go beyond “they were evil” or “they did whatever he wanted.” But two new novels explore the story of the Manson murders by shoving the ringleader to the side and putting the girls (and girlhood itself) at the center of the narrative: The much-discussed The Girls by Emma Cline, and the less-analyzed, though no less worthy, American Girls by Alison Umminger.

The Girls is a fictionalized re-telling of the days at the Manson family ranch before the murders, seen through the eyes of a new recruit named Evie. American Girls, set in the present day, is about a 15-year-old named Anna who spends a summer in Hollywood, learns about the Manson murders and grapples with them alongside the emotional violence she sees around her. Evie’s story, and the parallels Anna sees between her life and the lives of the young women she reads about, underscore something that other narratives have avoided: that maybe the girls—who’ve long held such enduring fascination in culture—are more relatable than many people would like to believe.

Evie, before she meets the people who draw her into a loosely veiled version of Manson’s family, is simply engaged in the tedious, hopeful business of being a teenage girl. She and her best friend spend their afternoons putting eggs in their hair, and reading magazines that offer thirty days of beauty tips to help prepare for the first day of school—“the constant project of our girl selves seeming to require odd and precise attentions,” Cline writes. But mostly, Evie waits for something—anything—to happen to her.

I remember my own girlhood primarily as waiting, too. Waiting for Christmas, or summer, or the next school year, or for my acne to go away. Waiting for college, waiting for the day a boy might be interested in me, waiting for my future to start. In middle school, I constantly wished for just a glimpse of my future self in high school, in college, as an adult, so I could see that I would end up okay; that I was moving toward something.

“The easy thing was to say No, they were monsters, they had to be monsters to do something like that.”

As an adult, Evie reflects on that very thing: “As if there were only one way things could go, the years leading you down a corridor to the room where your inevitable self waited—embryonic, ready to be revealed. How said it was to realize that sometimes you never got there.” Neatly, Cline makes the reader wonder—when you feel like your life has to have an eventual destination, are you more likely to follow someone who offers a path?

In Umminger’s book (which in the U.K. is called My Favorite Manson Girl, a much better title), Anna steals her stepmother’s credit card and runs away to live with her older sister, a struggling actress in Los Angeles. There, the creepy director of an indie film her sister is starring in (who also happens to be her sister’s ex) pays Anna to read about the Manson Family and give him reports, as “research.” And so she ends up processing everything that happens to her—the fallout of running away, her mother’s cancer, her sister’s self-destruction, a romance, the cruel way she treated a girl back home—on top of the backdrop of the Manson girls’ story. “Most people never thought of them as separate people at all,” writes Umminger of the girls—separate from Manson, she means, and what he made them do. But Anna does and Evie does, and Umminger does and Cline does.

Murders, especially strange, extreme murders like the ones perpetrated by Manson’s followers, fascinate people because they want to understand—who could have done this, why did they do it, what makes them kill? And as I’ve written about before, in the absence of a satisfactory explanation, people tend to write killers off as monsters. Evil is evil; it doesn’t need further explanation.

“The easy thing was to say No, they were monsters, they had to be monsters to do something like that,” Umminger writes. “But what if the truth was more complicated? What if they weren’t really as different as everyone wanted to believe?”

Cline’s writing is elegant and nostalgic, evoking beautifully a girlhood remembered. Umminger’s is brasher, crasser, more straightforward—showing a girlhood in progress. But reading both, it’s not hard to remember how it felt to be young and lonely and longing for the future: When I remember that time, the appeal Manson must have held makes perfect, frightening sense. Desire, when you haven’t been loved yet—romantically, anyway—is mostly about imagination. This makes idols easy to love, and loves easy to idealize. Teen girl love of Harry Styles, or the Beatles, or the boy next door who doesn’t know she exists, is more about what the girl wants, and how well the object of affection serves as a mirror for those desires.

“How impersonal and grasping our love was,” Cline writes, “pinging around the universe, hoping for a host to give form to our wishes.” Enter Charles Manson. Or “Russell,” as the Manson stand-in is known in The Girls.

Take Susan Atkins, for example, or “Sadie” as Manson nicknamed her. In her autobiography, the way she describes their initial meeting at first reads like pure projected desire. “My eyes landed instantly on a little man sitting on the wide couch in front of the bay windows [playing guitar]… His voice was middle range and expressive. He played the guitar magnificently … ‘He’s like an angel.’ I don’t think I spoke the thought aloud, but I was so loaded I couldn’t be sure. ‘I’ve got to dance—for him.’”

What if it’s not some dark force that drags good girls down a path to evil, but just our most basic desires?

But then, it all plays out like wish-fulfillment fan fiction. Manson gets up and dances with her, then tells her: “You are beautiful. You are perfect. I’ve never seen anyone dance like you. It’s wonderful. You must always be free.”

In American Girls, Anna reads Atkins’s autobiography, and finds it disappointing. “The fact that her reasons for taking part in the murders were all so stupid made the book extra depressing. I kept waiting for the moment when she revealed all the awful things that had happened to her that she’d forgotten to mention, but mostly she just sang the same old song. I wanted to be special. I wished Charlie and the other girls liked me more.”

The first night Patricia Krenwinkel met Manson, they had sex, and again, he told her she was beautiful. “I couldn’t believe that, I just started crying,” she told Diane Sawyer years later in an interview.

“I waited to be told what was good about me,” Evie recalls in The Girls. “I wondered later if this was why there were so many more women than men at the ranch.”

Reading about the girls, Anna thinks, “The fact that all the books mentioned how they looked meant that their appearances mattered, but no one ever said why, or how … I guess that Charles Manson had figured out why pretty mattered. Because he called Patricia Krenwinkel beautiful, even kept the lights on when they did the nasty, she chased down Abigail Folger and stabbed her so hard that she broke her spine in half.”

Manson’s desires were just as boring—to be famous, to be powerful. When the record deal he thought he deserved didn’t pan out, he became angry. There’s been some speculation that when Manson sent his family to kill the residents of the record producer Terry Melcher’s former home that night, it wasn’t just to start the race war he called Helter Skelter, but also partly to send Melcher a message, because he wouldn’t give Manson a record deal. As for the girls, if they first loved Manson because he told them they were special, it’s not hard to imagine that perhaps they shared his fury and disappointment when others told him he wasn’t special. Maybe they remembered how it felt, before him.

“The real danger,” Umminger writes, “wasn’t violence like you saw on the television news, random and exciting—the real danger was the vampiric kind, the sort that you invited in because it told you everything you wanted to hear.”

What draws Evie into the cult isn’t Manson—I mean Russell—but the other girls. One especially, Suzanne, strikes Evie as more wild and dangerous than the others. “She seemed as strange and raw as those flowers that bloom in lurid explosion once every five years, the gaudy prickling tease that was almost the same thing as beauty,” Cline writes. And when Suzanne speaks of the group gathered at Russell’s ranch, Evie wants to be a part of that community: “The girl was part of a we and I envied her ease.”

Fiction gives these authors the freedom to try to illuminate what the facts cannot.

So often, the way the girls’ story is told, it seems as though Manson is some kind of unstoppable force—a magnetic pit of evil that sucked them in. This is a comforting metaphor, because it allows us to think that most people would be smart enough to back away from the edge. But what if it’s not some unknowable dark force that drags good girls down a path to evil, but just our most basic desires that light the path with a welcoming glow?

On the ranch in The Girls, Evie and the others spend a lot of time doing drugs and talking about “the moment,” as she puts it. “We could talk about the moment for hours … It seemed like something important, our desire to describe the shape of each second as it passed, to bring out everything hidden and beat it to death.”

The story of the Manson girls has been combed intensely for hidden things, and what little we’ve found has been beaten to death. And yet it’s a story I keep coming back to, collecting and arranging details like they might add up to some kind of revelation, if I can just find the piece of the puzzle that makes it start to look like the picture on the box. Then I inevitably get bored or frustrated, and throw up my hands for a couple years before curiosity takes me to Wikipedia for another round. I keep thinking I’m going to find a new insight, but all I find is what I already know.

Fiction gives these authors the freedom to try to illuminate what the facts cannot. What it might feel like for someone to say exactly the things you’ve dreamed of hearing. “He thought I was smart. I grabbed on to it like proof. I wasn’t lost.” What it feels like to be lost: “I had become the human equivalent of one of those balloons we used to send into the air with our name and address on the string in the hope that someone might mail it back, but no one ever did.” Cline and Umminger take a crime that seems impossible to understand, and show the girls behind it being fueled by feelings that are all too familiar. (Again, I find only what I already know.) And, they ask, wouldn’t that be enough?

Where Stranger Things Loses Its Magic

This post contains spoilers for the first season of Stranger Things.

It’s impossible to talk about Stranger Things, the eight-episode Netflix sci-fi drama series released this month, without talking about all the ’80s references. Like the J.J. Abrams film Super 8, Stranger Things is an homage to all things Spielbergian—broken families, kids having secret adventures on bikes, supernatural beings, government conspiracies, heartfelt endings. After the series debuted, journalists began publishing comprehensive guides to its many, many allusions, a testament to the show’s dedication to authentically reconstructing the past.

But even if you’ve never seen E.T. or The Goonies, or lived through the 1980s in suburban America, Stranger Things has plenty to offer. Set in a small Indiana town, the story centers around the mysterious disappearance of a young boy named Will, the search effort that ensues (led by his mother, played by Winona Ryder), and the arrival of an odd young girl with strange powers. In the hands of its directors, the Duffer Brothers, Stranger Things is at turns touching (when it explores teenage love and friendship) and harrowing (when it follows the creature that turns out to be terrorizing the town).

Over the first seven episodes it’s easy to get swept up in how well the show reanimates beloved movie tropes and channels the feel of the 1980s. But by the finale, it becomes clear that the series has an ugly side that can be traced to the show’s treatment of its most vulnerable and enigmatic major character: the 12-year-old girl with magical abilities who goes by the name “Eleven.” Judging by her arc, which involves near-constant suffering, Eleven seems like Stranger Things’ biggest blind spot. The show harbors empathy for its many characters: Ryder’s harried mother Joyce, Police Chief Jim Hopper, Will’s best friend Mike, Mike’s teenage sister Nancy. Yet despite a rich backstory, Eleven is the show’s most thinly sketched protagonist, and it sometimes feels like Stranger Things’ reverence for 1980s pop culture is to blame.

In her first scene, Eleven is walking alone and barefoot in the woods, wearing only a hospital gown. She has a shaved head, can barely speak, and has a tattoo of the number “011” on her wrist. By the time Will’s friends Mike, Lucas, and Dustin find her, she’s already witnessed the fatal shooting of a kindly restaurant owner who tried to get her help. When they ask her what her name is, she points to her tattoo. (They call her “El” for short.)

Credit

Through brutal flashbacks, the show reveals that a secret government program was studying Eleven for her telekinetic powers. It also emerges that her mother was the subject of an earlier experiment that used LSD on patients, and that the government covered up Eleven’s birth. Growing up, the girl is treated as a prisoner, only dragged out of her tiny, bare room in a windowless bunker when it’s time for scientists to conduct experiments on her. They use her to spy on communists and make contact with inter-dimensional beings, but the latter mission goes awry, and Eleven accidentally frees a monster from a dark netherworld, causing Will’s disappearance.

Though deeply traumatized and physically and psychologically underdeveloped, Eleven becomes uneasy friends with Will’s group—especially Mike, who’s incredibly protective of her. And at first things seem hopeful: The boys realize she’s their key to finding out what happened to their missing friend, so they help hide her from the government agents trying to track her down. But mostly they’re impressed by her abilities. “We never would’ve upset you if we knew you had superpowers,” Dustin tells her. Eleven is often treated like a liability—a major character relegated to the corners of the story unless it’s time to save the day with her mind.

Eleven is clearly the token girl of the group—recalling the “Smurfette Principle” trope that pervaded children’s TV during that decade—but the show doesn’t display much self-awareness on this point. There’s even a textbook “makeover scene” involving a wig, some makeup, and a dress that leads the boys to behold a transformed Eleven in awe. In some ways, El’s background makes her more complex than the average young female protagonist. But because of what happened to her, she doesn’t talk much, leaving her a cipher to almost everyone who meets her—and to the audience. Her silence makes her mysterious, but it also flattens her character.

In aping earlier cinematic glories, there’s always the risk of replicating more subtly retrograde tendencies.

Stranger Things clearly draws from beloved coming-of-age narratives like Stand By Me and The Goonies. But the show is most generous in exploring the confusion and thrill of adolescence when it comes to the boys. Eleven herself doesn’t get to “grow up” herself; she’s there to help her new friends learn important life lessons. The best evidence for this comes in the climax for the series’ disappointing finale, “The Upside Down.” With the monster going on a rampage through the town, the group hides in a school classroom. Having just killed a horde of evil government agents, Eleven is almost unconscious. “We’ll be home soon and my mom … she’ll get you your own bed,” Mike tells her, clasping her hands. “Promise?” Eleven asks, crying. “Promise,” he replies. Moments later, the monster rushes in. The end seems near when an inexplicably revived Eleven slams the monster into the wall. Nose bleeding, she turns to the horrified boys behind her. “Goodbye, Mike,” she says. The monster explodes, and when the dust clears, Eleven is gone, too.

Later, Will has been recovered from the alternate dimension, and the boys visit him in the hospital. “We made a new friend,” Mike says. “She stopped [the monster]. She saved us. But she’s gone now.” Then, they begin excitedly regaling him with tales of how cool Eleven was, comparing her to Yoda, recounting how she made a bunch of government agents’ brains explode. It’s at this point the viewer realizes: The real Eleven has been erased and rewritten as just another action hero. Stranger Things spent several hours unspooling the visceral horrors Eleven encountered in her young life, trying to make her pain and sadness real. But in its final scenes, the show undid all of that. It made her into a bizarre martyr: the tragic, silent girl who suffered for abilities she never asked for, who seemed to only exist so she could nobly sacrifice herself at the end of the story.

No doubt, Eleven’s “death” was meant to be the sad-but-uplifting sort—but the casual treatment of her departure after so much buildup suggests that Stranger Things cared less about her than it initially implied. The show built Eleven to add more danger and excitement to an otherwise typical tale of boyhood adventure, only to conveniently dispatch her. (Oddly, Eleven’s story closely mirrors that of the female protagonist in last year’s pallid Goosebumps film.) In aping earlier cinematic glories, there’s always the risk of replicating more subtly retrograde tendencies.

Stranger Things is unwittingly guilty of this mistake, overwhelmingly privileging the happiness, desires, words, and lives of El’s friends over hers. Still one of Netflix’s better dramas, the show will continue to find avid fans, eager to relish its attention to period-specific detail and its compelling central mysteries. It’s also further proof that there’s no shortage of talent and creativity in the age of Peak TV. But there’s a higher bar for original stories—even homages—to clear when it comes to incorporating the lessons Hollywood has learned recently about depicting female characters who are as layered as their male counterparts. For all its charms, Stranger Things doesn’t quite meet that standard.

The Chicago Cubs Embrace a Controversial Baseball Player

The Chicago Cubs just acquired one of the best closing pitchers in professional baseball. But some fans aren’t excited about the man they’re getting in the trade.

Aroldis Chapman, who was traded from the New York Yankees, was suspended for the first 30 games of this season for violating the league’s domestic-violence policy. In December, he allegedly pushed his girlfriend against a wall and choked her. He also fired his gun eight times in his garage during the argument, according to a police report of the incident.

Cubs owner Tom Ricketts acknowledged Chapman’s suspension when Ricketts announced the trade Monday. But he quickly tried to ease concern, saying Chapman “takes responsibility for his actions.” He said:

I shared with him the high expectations we set for our players and staff both on and off the field. Aroldis indicated he is comfortable with meeting those expectations.

Chapman acknowledged his history in a statement Monday:

I regret that I did not exercise better judgment and for that I am truly sorry. Looking back, I feel I have learned from this matter and have grown as a person. My girlfriend and I have worked hard to strengthen our relationship, to raise our daughter together, and would appreciate the opportunity to move forward without revisiting an event we consider part of our past.

Major League Baseball policy does not specify the number of games a player is suspended from if they commit an act of sexual or domestic violence. Players usually return after their suspensions, just as Chapman did. Professional athletes at times are punished through the league, and sometimes law enforcement. But after they serve their punishment, they’re back to being handsomely paid athletes competing for teams that fans invest a great deal of emotional and financial support. They return to receiving praise for their talent. Chapman, for instance, allegedly choked his girlfriend but he can also pitch 105 miles per hour.

In the sports world, reports of domestic violence, or even sexual assault, can become footnotes in the larger story of their athletic prowess and statistics. This was the only mention of Chapman’s incident from popular sports columnist Bob Nightengale’s article in USA Today about the trade:

He missed the first 30 games of the season after being suspended for a domestic violence incident with his girlfriend, but has been successful in 20 of 21 save opportunities this year. He’s 3-0 with a 2.01 ERA, striking out 44 batters in 31.1 innings, with a fastball that has been clocked as fast as 105 last month.

After Patrick Kane, a star hockey player for the Chicago Blackhawks, performed well in the months that followed a rape investigation, the Chicago Sun Times framed it as a “rough patch” that he overcame with the longest NHL point streak in more than two decades.

A zero-tolerance policy could help alleviate this problem—an athlete commits an act of domestic violence and he is out of the league forever. That’s the way Steve Spurrier, the former University of South Carolina football head coach, sees it. “Never, ever, hit a girl. If you do this, you’re finished as a Gamecock football player,” says the player’s manual for the team.

But this policy is not widespread. In 2014, the White House pushed the NFL to have a zero-tolerance policy, saying in a statement:

Many of these professional athletes are marketed as role models to young people and so their behavior does have the potential to influence these young people, and it’s one of the many reasons it’s important that the league get a handle on this and have a zero tolerance.

After former Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice was caught on video punching his then-fiancée in 2014, the league was widely criticized for botching its reaction before eventually suspending Rice indefinitely. The league would later institute a new policy in which players are suspended for six games for their first incident of domestic or sexual violence and banished from the league in a second offense.

Rice later won his appeal to play football again, but he has yet to find a team willing to sign him. He has even pledged to donate his entire salary this upcoming season to organizations working to prevent domestic violence if a team lets him play.

Some football teams don’t want the risk of being associated with someone accused of these crimes. After Montee Ball was arrested for throwing his girlfriend into a table in February, the New England Patriots cut him from the team four days later. No team has picked him since the incident.

Professional sports leagues are still riddled with men who have committed domestic or sexual violence, like Chapman. The Cubs picked him up because they felt he could help them win the World Series.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower