Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 110

August 1, 2016

Who 'The Simpsons' Are Voting For

NEWS BRIEF Homer and Marge Simpson are voting for Hillary Clinton.

The Simpsons has added its take to the ocean of 2016 presidential election takes with a new two-minute clip that shows how Clinton and Donald Trump would handle a 3 a.m. phone from the Situation Room. Let’s say their responses would be different.

The clip shows Clinton eagerly taking the call—and taking the phone away from her husband and former president. It also shows a bald, untanned Trump in bed— a volume of great speeches by A. Hitler beside him—ignoring the call in favor of tweeting. By the time he does respond, eight hours later, it’s too late to stop the advancing Chinese fleet, the television show says.

Neither Trump nor Clinton has responded to the clip, which is an apparent reference to the “3 a.m. phone call” line Clinton used against her then-rival Barack Obama in the 2008 Democratic presidential primary to question his judgment and experience.

July 31, 2016

Wisconsin's Voting Laws Struck Down

NEWS BRIEF A federal district court struck down a series of voting restrictions in Wisconsin on Friday, marking the third major victory for voting-rights advocates this month.

In his 119-page ruling, federal judge James Peterson framed the state legislature’s efforts to enact strict voter-ID laws as an overreaction to the perceived threat.

“The Wisconsin experience demonstrates that a preoccupation with mostly phantom election fraud leads to real incidents of disenfranchisement, which undermine rather than enhance confidence in elections, particularly in minority communities,” he wrote. “To put it bluntly, Wisconsin’s strict version of voter ID law is a cure worse than the disease.”

Among the restrictions blocked were requirements that each city only have one polling place for early voting, an extended residency requirement for city wards, and strict rules governing what can be used as voter ID.

The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel has more:

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett praised the ruling, saying that "without a question" the city would take advantage of it to help more of its citizens vote.

"Gov. (Scott) Walker and the Legislature wanted to create a bottleneck in the city of Milwaukee to make it more difficult for people to vote," Barrett said.

The decision deals with a swath of election laws that have been modified in recent years by Walker and Republican lawmakers. Peterson, who was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2014, concluded many of them violate the First Amendment right to free speech, the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal protection under the law and the Fifteenth Amendment protection of the right to vote.

Wisconsin joins two other states where federal courts recently struck down restrictive voting laws. Earlier this month, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled Texas’s voter-ID law had a racially discriminatory effect to suppress black and Hispanic voters. Then, hours before the Wisconsin ruling, the Fourth Circuit ruled that recent changes to North Carolina’s election law targeted black voters “with almost surgical precision.”

'He Doesn't Know What the Word Sacrifice Means'

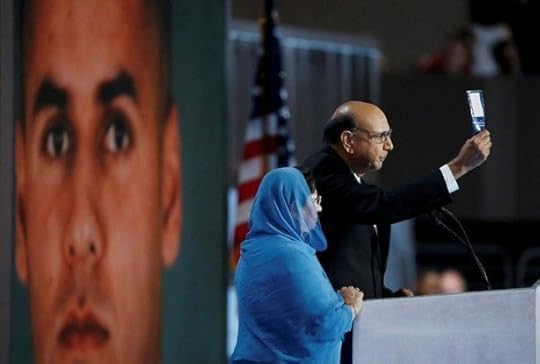

“I've had a flawless campaign,” Donald Trump insisted this weekend. A campaign’s most serious errors are only sometimes obvious in retrospect, but Trump’s decision to launch an all-out rhetorical war with Khizr and Ghazala Khan looks like an unforced error.

The Khans, Muslims immigrants from Pakistan, spoke Thursday at the Democratic National Convention, recalling their son, Captain Humayun Khan, who died while serving in Iraq in 2004.

Related Story

The Most Inspiring and Depressing Moment of the Democratic Convention

“Hillary Clinton was right when she called my son ‘the best of America,’” Khizr Khan said. “If it was up to Donald Trump, he never would have been in America. Donald Trump consistently smears the character of Muslims.… Let me ask you: Have you even read the U.S. Constitution? I will gladly lend you my copy. In this document, look for the words ‘liberty’ and ‘equal protection of law.’”

Khan added, “You have sacrificed nothing and no one.”

The speech was a breathtaking moment, hailed by conservatives and liberals alike. For about a day, Trump steered clear of commenting, perhaps a wise choice: What could he profitably say? But starting Friday night, the Republican nominee began firing back.

The most complete response came in an interview with ABC’s George Stephanopoulos. First, Trump made light of the fact that Ghazala Khan had not spoken. “His wife, if you look at his wife, she was standing there,” Trump said. “She had nothing to say. She probably—maybe she wasn't allowed to have anything to say.” (Ghazala Khan said she was too overcome with emotions to speak.)

“I think I have made a lot of sacrifices. I've worked very, very hard. I've created tens of thousands of jobs, built great structures.”

Second, he tried to change the subject: “We have had a lot of problems with radical Islamic terrorism, that's what I'd say. We have had a lot of problems where you look at San Bernardino, you look at Orlando, you look at the World Trade Center, you look at so many different things.” Then he tried to change the subject again, attacking retired Marine General John Allen, who also spoke at the DNC Thursday, for failing to defeat ISIS.

Finally, pressed by Stephanopoulos, he insisted he had sacrificed—by having a career in business. “I think I have made a lot of sacrifices,” he said. “I've worked very, very hard. I've created thousands and thousands of jobs, tens of thousands of jobs, built great structures. I've done—I've had tremendous success.” Stephanopoulos asked whether those were really sacrifices. “Oh, sure. I think they're sacrifices,” Trump said, likening his pursuit of monetary success to parents’ loss of a child in service of the nation.

Trump also made his point about Ghazala Khan in a conversation with The New York Times’ Maureen Dowd. Trump also issued a statement Saturday night, in which he said, in part:

While I feel deeply for the loss of his son, Mr. Khan who has never met me, has no right to stand in front of millions of people and claim I have never read the Constitution, (which is false) and say many other inaccurate things.

Trump’s statement is notable for how it garbles Khizr Khan’s comments—Khan merely asked whether Trump had read it—and for a very narrow reading of the right to free speech, an ironic twist for a man defending himself against charges that he does not understand the First Amendment.

On Sunday morning, Trump defended his right to swing at Khizr Khan:

I was viciously attacked by Mr. Khan at the Democratic Convention. Am I not allowed to respond? Hillary voted for the Iraq war, not me!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 31, 2016

Trump supported the war in Iraq, though he has repeatedly claimed he did not.

The Khan family did not hesitate to respond to Trump. Khizr Khan angrily responded in several interviews. “Unlike Donald Trump’s wife, I didn’t plagiarize my speech,” Khan told the Times, adding that his wife had persuaded him to remove other personal attacks on Trump from his remarks. He told The Washington Post that Trump’s attacks on his wife were “typical of a person without a soul” and told CNN, “He is a black soul, and this is totally unfit for the leadership of this country.”

Ghazala Khan, meanwhile, replied in a column in the Post:

Donald Trump has asked why I did not speak at the Democratic convention. He said he would like to hear from me. Here is my answer to Donald Trump: Because without saying a thing, all the world, all America, felt my pain. I am a Gold Star mother. Whoever saw me felt me in their heart.

She concluded: “Donald Trump said he has made a lot of sacrifices. He doesn’t know what the word sacrifice means.”

By choosing an all-out fight with the Khans, Trump is showing that he still has the capacity to surprise, more than a year after he surprised the political world by declaring a run for the presidency. It’s been less than a week since Trump flabbergasted foreign-policy and government experts by expressing his hope that a foreign government had hacked and would release government messages.

The Khan feud, if less freighted with geopolitical import, represents an even stranger choice. As Philip Rucker summed it up, with less than 99 days until the election, the Republican nominee is debating with the parents of a slain American serviceman over whether he has sacrificed as much they have. David Simon, creator of The Wire, added, “If I scripted this, it would critiqued harshly and correctly as West Wing-era liberal wish-fulfillment.” But over the last 14 months, Trump has repeatedly done things that made liberals rub their hands in glee—only to see him escape unscathed.

Most (in)famously, he made light of Senator John McCain, who was shot down, taken prisoner, and tortured in Vietnam. “He’s not a war hero,” said Trump. “He was a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.” Trump’s standing in the GOP primary didn’t falter, and McCain has since endorsed him for president.

McCain, however, is an experienced politician—a part of the rough-and-tumble D.C. world, fair game for attacks. The Khans, despite their rapidly growing profile, are not. Moreover, it’s not the primary anymore. My colleague David Frum warns against assuming gaffes like this could harm Trump, but Trump’s challenge over the next three months is not simply to hold his coalition; he needs to build it, especially with post-DNC polls giving Hillary Clinton back a lead. Debating the Khans over sacrifice isn’t a coalition-building move.

In late 1953, Senator Joe McCarthy turned his red-baiting crusade toward the Army, accusing it of being stocked with Communists. McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn, had miscalculated, and the reaction doomed McCarthy’s crusade and career. Decades later, Cohn became a close friend of a young real-estate developer named Donald Trump. If Cohn’s protégé learned anything about from him about why it’s unwise for a politician to go to war with the U.S. Army, it isn’t showing today.

Buffy Summers: Third-Wave Feminist Icon

The cult television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer is now indisputably one of the most widely analyzed texts in contemporary popular culture. The end of the series in 2003 didn’t herald the passing of a fleeting academic fancy, as many must have expected, but instead ushered in an unprecedented number of monographs, edited collections, book chapters, journal articles, and even university courses that grapple with the Buffy phenomenon one way or another.

Gender analysis has been central to popular and academic critiques of Buffy from the series’ inception, and debates about its feminist rhetoric, politics, and potential continue to engage readers and viewers, scholars and fans. But what accounts for the extraordinary and enduring feminist appeal of Buffy, more than a decade after it went off the air? And how did its ex-cheerleading, demon-hunting heroine become the poster girl for third-wave feminist popular culture?

Simply put, Buffy, the story of a popular high-school student chosen by fate to fight vampires, offers a vision of collective feminist activism that’s unparalleled in mainstream television. At the same time, the series’ emphasis on individual empowerment, its celebration of the exceptional woman, and its problematic politics of racial representation remain important concerns. But in its final season, which ran from September 2002 to May 2003, Buffy offered a more straightforward and decisive feminist message than the show had attempted before. And in doing so it painted a compelling picture of the promises and predicaments that attend third-wave feminism as it negotiates both its second-wave predecessors and its traditional patriarchal nemeses.

Over its seven-year cycle the series addressed a staggering range of contemporary concerns, from the perils of low-paid, part-time employment to the erotic dynamics of addiction and recovery. But it’s significant that the final season of Buffy makes a decisive shift back to feminist basics. Season seven eschews the metaphorical slipperiness and pop-cultural play that’s typical of its evocation of post-modern demons and instead presents a monster who is, quite literally, an enemy of women.

The principal story arc pits an amorphous antagonist, The First Evil, against the Slayer and her “army,” a group that’s swelled to include in its ranks “Potential” Slayers from around the world. In introducing a previously unknown matriarchal legacy (and weapon) for the Slayer, staging the series’ final showdown with a demon who’s overtly misogynist, and creating an original evil with a clearly patriarchal platform, Buffy’s final season raises the explicit feminist stakes of the series considerably.

One of the greatest challenges Buffy faces in season seven is negotiating conflicting demands of individual and collective empowerment.

Unable to take material form, The First Evil employs a former preacher turned agent-of-evil called Caleb as its vessel and deputy. Spouting hellfire and damnation with fundamentalist zeal, Caleb is, of all of the show’s myriad manifestations of evil, the most recognizably misogynist. Dubbed “the Reverend-I-Hate-Women” by Xander, Caleb is a monstrous but familiar representative of patriarchal oppression, propounding a dangerous form of sexism under the cover of pastoral care. “I wouldn’t do that if I were you, sweetpea,” Caleb at one point warns Buffy. At other times he calls her “girly girl,” “little lady,” and once (but only once), “whore.” Buffy’s response (after kicking him across the room) is to redirect the condescension and hypocrisy couched in his paternal concern: “You know, you really should watch your language. Someone didn’t know you, they might take you for a woman-hating jerk.”

In comparison with the supernatural demons of previous episodes, Caleb’s evil might seem unusually old-fashioned or even ridiculous, but his successive encounters with the Slayer underscore the fact that his power is all the more insidious and virulent for that. Mobilizing outmoded archetypes of women’s weakness and susceptibility, Caleb effectively sets a trap that threatens to wipe out the Slayer line. Within the context of the narrative, his sexist convictions, and, more importantly, their unconscious internalization by the Slayer and her circle, pose the principal threat to their sustained, organized, and collective resistance.

In its exploration of the dynamics of collective activism, Buffy’s final season examines the charges of individualism that have frequently been directed at contemporary popular feminism. “Want to know what today’s chic young feminist thinkers care about?” wrote Ginia Bellafante in a notorious 1998 article for Time magazine. “Their bodies! Themselves!”

One of the greatest challenges Buffy faces in season seven is negotiating conflicting demands of individual and collective empowerment. Trapped by the mythology propounded by the Watchers’ Council that bestows the powers of the Slayer on just “one girl in all the world,” Buffy is faced with the formidable task of training Potential Slayers-in-waiting who will only be called into their own power in the event of her death. In the episode “Potential,” Buffy attempts to rally her troops for the battle ahead:

The odds are against us. Time is against us. And some of us will die in this battle. Decide now that it’s not going to be you … Most people in this world have no idea why they’re here or what they want to do. But you do. You have a mission. A reason for being here. You’re not here by chance. You’re here because you are the Chosen Ones.

This sense of vocation resonates strongly with feminist viewers who feel bound to the struggle for social justice. However, such heroism can still be a solitary rather than collective battle. On the eve of their final fight, after decimating her advance attack, The First-as-Caleb makes fun of what he calls Buffy’s “One-Slayer-Brigade” and taunts her with the prospect of what we might think of as wasted Potential:

None of those girlies will ever know real power unless you’re dead. Now, you know the drill … “Into every generation a Slayer is born. One girl in all the world. She alone has the strength and skill …” There’s that word again. What you are, how you’ll die: alone.

Such references make it clear that loneliness and isolation are part of the Slayer’s legacy. Balancing the pleasures and price of her singular status, Buffy bears the burden of the exceptional woman. But the exceptional woman, as many leaders including Margaret Thatcher have amply demonstrated, is not necessarily a sister to the cause—a certain style of ambitious woman fashions herself precisely as the exception that proves the rule of women’s general incompetence.

In one of the more dramatic and disturbing character developments in the series as a whole, season seven presents Buffy’s leadership as becoming arrogant and autocratic, her attitude isolationist and increasingly alienated. Following in the individualist footsteps of prominent “power feminists,” Buffy forgoes her collaborative community and instead adopts what fans in the United States and elsewhere perceived as a sort of “you’re-either-with-me-or-against-me” moral absolutism—an incipient despotism exemplified by what Anya calls Buffy’s “everyone-sucks-but-me” speech. The trial of Buffy’s leadership is sustained up to the last possible moment.

Drawing attention to the Slayer’s increasing isolation, The First highlights the political crisis afflicting her community, but in doing so he inadvertently alerts Buffy to the latent source of its strength, forcing her to claim a connection she admits “never really occurred to me before.” In a tactical reversal that Giles claims “flies in the face of everything … that every generation has ever done in the fight against evil,” Buffy plans to transfer the power of the Chosen One, the singular, exceptional woman, to the hands of the Potentials—to empower the collective not at the expense of, but by force of, the exception. In the series finale, Buffy addresses her assembled army in the following terms:

Here’s the part where you make a choice. What if you could have that power now? In every generation one Slayer is born, because a bunch of men who died thousands of years ago made up that rule. They were powerful men. This woman [pointing to Willow] is more powerful than all of them combined. So I say we change the rules. I say my power should be our power. Tomorrow, Willow will use the essence of the scythe to change our destiny. From now on, every girl in the world who might be a Slayer will be a Slayer. Every girl who could have the power will have the power. Can stand up? Will stand up. Slayers—every one of us. Make your choice: are you ready to be strong?

At that moment—as the archaic power of a recently recovered matriarchal scythe is wrested from the patriarchal dictates of the Watchers’ Council—the show offers a series of vignettes from around the world, as young women of different ages, races, cultures and backgrounds sense their strength, take charge and rise up against their oppressors. This is a ‘feel the force, Luke’ moment for girls on a global scale.

In transferring power from a privileged, white Californian teenager to a group of women from different national, racial and socio-economic backgrounds, Buffy’s final season addresses—almost as an afterthought—the issue of cultural diversity that’s been at the forefront of third-wave feminist theorizing.

The contradictions embedded in Buffy’s cultural politics are indicative of the crosscurrents that distinguish the third wave of feminism.

From some of its earliest incarnations, academic third-wave feminism has presented itself as a movement that places questions of diversity and difference at the center of its agenda. In its less careful incarnations, as Buffy demonstrates admirably, third-wave feminism can perform the very strategies of occlusion and erasure that it’s aiming to redress. Buffy’s racial politics are more conservative than the show’s gender or sexual politics, a situation summarized by one of the few black characters to recur in the show’s first three seasons, Mr Trick, who says, “Sunnydale […] admittedly not a haven for the brothers – strictly the Caucasian persuasion in the Dale.”

But the contradictions embedded in Buffy’s cultural politics are indicative of the crosscurrents that distinguish the third wave of feminism. The refusal of misogynist violence, the battle against institutionalized patriarchy, and the potential of feminist activism are issues that remain at the forefront of the third-wave agenda, and are themes that Buffy’s final season explores with characteristically challenging and satisfying complexity. The fact that its success in critiquing its own cultural privilege is equivocal should be read less as a straightforward sign of failure than a reflection of the contradictions that characterize third-wave feminism itself.

In its examination of individual and collective empowerment, its ambiguous politics of racial representation and its willing embrace of contradiction, Buffy is a quintessentially third-wave cultural production. Providing a fantastic resolution—in both senses of the word—to some of the many dilemmas confronting third-wave feminists today, Buffy is comfort food for girls who like to have their cake and eat it too.

This article has been adapted from Patricia Pender’s book, I’m Buffy and You’re History: Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Contemporary Feminism.

July 30, 2016

From Olympic Gymnasts to Drake : The Week in Pop Culture Writing

An Ethical Stretch

Meghan O’Rourke | The Cut

“[Gymnastic’s] obsessive focus on the body and self-presentation is like kerosene poured on the flame of female adolescent self-scrutiny. By some lights, women’s gymnastics has come to seem almost retrograde, anti-feminist. I’ve even wondered whether watching gymnastics today is like watching the NFL in an era when we know its true price.”

Minimalism at Maximum Capacity

Kyle Chayka | The New York Times Magazine

“Part pop philosophy and part aesthetic, minimalism presents a cure-all for a certain sense of capitalist overindulgence. Maybe we have a hangover from pre-recession excess—McMansions, S.U.V.s, neon cocktails, fusion cuisine—and minimalism is the salutary tonic. Or perhaps it’s a method of coping with recession-induced austerity, a collective spiritual and cultural cleanse because we’ve been forced to consume less anyway.”

Rock-Docs in the Age of Access Journalism

Judy Berman | Pitchfork

“It makes sense that we’re hearing more about mental and physical illness as directors move beyond hagiographic or didactic portraits of famous musicians, to follow the longer arcs of lives that stretch past age 27 and contain more conflict than the relationship between a man, his guitar, and a crowd of screaming fans.”

Bringing Denzel Washington to the Table

Shea Serrano | The Ringer

“The most believably unbelievable performance comes in American Gangster, directed by Sir Ridley Scott. Washington’s character, a crime lord named Frank Lucas, holds court at a table during breakfast with his team. He sees a separate crime lord, Tango, played by Idris Elba, who is very handsome — more handsome than Old Denzel Washington, but not nearly as handsome as Young Denzel Washington. Tango owes Frank money. Frank wants it. Tango bucks. Frank shoots him in the head. Then he walks back to the table and sits down. It’s the farthest a Denzel Washington movie character has wandered away from a table and returned to it in the same scene. The table is a diner table.”

Drizzy’s Dancehall Appropriation

Sajae Elder | Buzzfeed

“For many American listeners, Drake’s claim to Afro-Caribbean music and culture seems contrived and unexpected — another example of his tendency to “ride” a particular wave and then move on to something else. It begged the question: What could a half-black, half-Jewish Canadian know about Jamaica? ‘There are all these different sounds so far on Views,’ some wondered, “but what does Toronto actually sound like?’”

Welcome to the ‘New Normal’: Kubrick and the Nuclear Farce

Robert Bright | The Quietus

“The only way out of the paradox of nuclear war lies in the ‘mind of man’ said Kubrick, and to fully appreciate the brilliance of Dr. Strangelove, we need to know that when he said it, it was men specifically he was referring to. The sublimation of sex and sexual anxiety are everywhere in the film. It’s obvious right from the start, where mid-air refueling sees the thick metal rod from a supply plane being inserted into a B52 bomber, all done to an instrumental version of ‘Try A Little Tenderness.’”

Dance, Little Sister

Karen Good Marable | The Undefeated

“The girls are athletes. Muscular and brown — a sea of builds and shades. Most of them have weaves that are as much about protecting their natural hair underneath as they are about the ability to whip it.”

80 Books No Woman Should Read

Rebecca Solnit | Literary Hub

“I just think some books are instructions on why women are dirt or hardly exist at all except as accessories or are inherently evil and empty. Or they’re instructions in the version of masculinity that means being unkind and unaware, that set of values that expands out into violence at home, in war, and by economic means. Let me prove that I’m not a misandrist by starting with Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, because any book Paul Ryan loves that much bears some responsibility for the misery he’s dying to create.”

Watching The Purge in Our Year of Nightmare Politics

Jia Tolentino | The New Yorker

“I watched the movie in a small theatre in Brooklyn popping with children. None of them were white and all of them looked well under the age of seventeen. (All The Purge movies are rated ‘R’) They reacted effusively, externalizing things that do not sit easily: the nerves, the panic, the hardness required to take pleasure in the cinematic execution of civilians at a time when we already see such things on the news, on our phones, in our minds, on the street. This is a year when violence crackles ambiently.”

Where Have All the Political Novels Gone?

Richard T Kelly | The Guardian

“But there is often a difficulty for writers who adopt an overtly political stance. A novelist may set out purposefully to make a book that furthers a cause, but it is not likely to be any good, since good books don’t carry messages like sacks carry coal.”

What We're Reading This Summer

The Atlantic’s editors and writers share their recommendations for summer reading—new titles, old favorites, and others in between.

Knopf

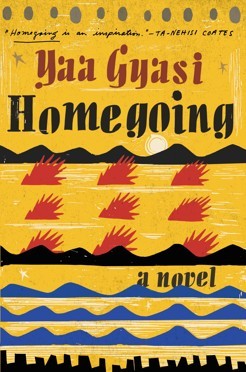

Homegoing

By Yaa Gyasi

In her first novel, Yaa Gyasi cleverly weaves the intergenerational tale of a family through a series of short, but interrelated stories set in what’s now Ghana during the mid-18th century. The two women at the center of the novel, Effia and Esi, are half-sisters who wind up on vastly different paths. One is captured during a battle between tribes, sold, and winds up on a slave ship bound for the U.S. The other—separated from her village and married off to a British slaver—ends up living on top of the dungeons that hold her own kin and hundreds of others who would also become slaves. The novel traces the lineage of these women through the tales of their children, and their children’s children, and so on—up until the present day.

Perhaps the most powerful aspect of Homegoing is how it takes racial history that’s often sanitized or glossed over and deftly pushes the the reader to contemplate the horrors inflicted upon black bodies at a granular and personal level. “Ness would fall asleep to the images of men being thrown into the Atlantic Ocean like anchors attached to nothing: no land, no people, no worth,” she writes. “In the Big Boat Esi said, they were stacked ten high, and when a man died on top of you, his weight would press the pile down like cooks pressing garlic.”

In her beautiful and painstaking retelling of this tragically divided family, Gyasi does more than provide a compelling fictional narrative—she lays out how the atrocities committed against a group of people have lived on, morphing across place and time. From slavery to Jim Crow to drug epidemics. From the Cape Coast to Pratt City to Harlem.

I read Homegoing during yet another week of heightened racial tension, anger, and disillusionment. But instead of increasing my despair, Gyasi’s placement of Africans and black Americans as the central characters in the story of race—capable of both tremendous sin and tremendous resilience, with the ability to overcome, change, and push forward—made the story hopeful and empowering. I hadn’t felt that way in a very long time.

Book I’m hoping to read: Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching by Mychal Denzel Smith

—Gillian White, senior associate editor

Vintage

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running

BY Haruki Murakami

Writing, like running, is something that’s glorious in theory, uncomfortable and humiliating in practice, and much easier to appreciate once it’s done. I love both; I frequently hate both, too. In summer—particularly in Washington where a five-minute walk to the drugstore leaves you languid and limp—it’s all too easy to put off either. But Haruki Murakami’s slight 2008 book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running is the perfect antidote to procrastination.

Part-memoir, part-fitness journal, part-travelogue, the book narrates a period in the author’s life (from 2005 to 2006) as he trains for the New York Marathon. Along the way, he recounts how he became a runner and how he became a writer, how similar the impulse was in both cases, and how the rhythm of long-distance running mimics the rhythm of writing. Both, Murakami argues, require discipline, talent, and commitment. But he also points out how running in some sense is a natural complement to the life of a writer: It forces you outside, and counteracts the “unhealthy type of work” that writing can be.

“Most runners run not because they want to live longer, but because they want to live life to the fullest,” he writes. “If you’re going to while away the years, it’s far better to live them with clear goals and fully alive then in a fog, and I believe running helps you to do that. Exerting yourself to the fullest within your individual limits: that’s the essence of running, and a metaphor for life—and for me, for writing as whole. I believe many runners would agree.” It’s hard not to. In writing about running with such precision and clarity, Murakami offers a compelling endorsement of both.

Book I’m hoping to read: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler

—sophie gilbert, senior editor

Random House

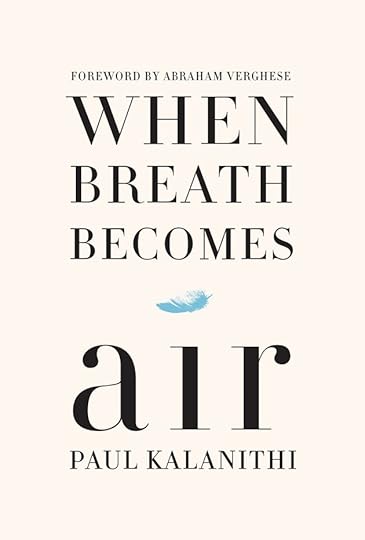

When Breath Becomes Air

by Paul Kalanithi

Despite loftier Goodreads ambitions, I’ve tended to tear into a certain type of book this year: collections of essays by sad girls and cool ladies. Paul Kalanithi’s memoir stood apart, but was no less absorbing. The book details Kalanithi’s two-year battle with stage-four metastatic lung cancer; he was diagnosed in 2013 toward the end of a neurosurgery residency at Stanford University, and he died last year at the age of 37.

Sure, the subject matter is heavier than the average beach read. But the best part of summer reading is—in theory, at least—having the time and capacity to be utterly consumed by a book. Kalanithi’s writing prompts a different kind of escapism from what you might associate with vacation lit—less distraction, more clarity. For me, the book was an invitation to confront my own understanding of a full life, the satisfying achievements and enduring love therein.

Kalanithi’s reflections on learning, growing, and dying are vulnerable and thoughtful. His language is fluid, elegant, and liable to linger in your head for days after reading. He faced his illness at the apex of a life built leaning into pain and the inevitability of death, absorbing as much as he could of the world. “Even while terminally ill Paul was fully alive,” his widow, Lucy, writes in the epilogue. “Despite physical collapse, he remained vigorous, open, full of hope not for an unlikely cure but for days that were full of purpose and meaning.”

Book I’m hoping to read: The Mothers by Brit Bennett

—Caty Green, managing editor

Simon & Schuster

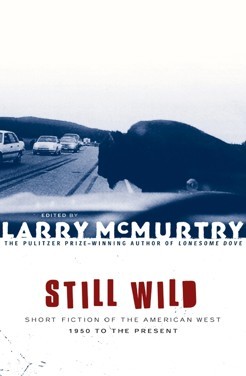

Still Wild: Short Fiction of the American West 1950 to the Present

by Larry McMurtry

Larry McMurtry, minor regional novelist, is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Lonesome Dove, The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment, and your grandfather's wildest dreams. Still Wild, a 2001 short-story collection he edited, is a gathering of some of the best in contemporary Western short fiction: a meditation on the American West as a strange, dangerous, and lonely place, written by a murderer’s row of contributors including Richard Ford, Wallace Stegner, Louise Erdrich, Raymond Carver, and Dianna Osanna.

Here, the West comes at you sideways—there are no John Waynes, and Monument Valley is far away. Rather, these stories interest themselves in a feeling, an environment. As McMurtry notes in the book’s introduction, only since 1950 has the West really become a producer—“as opposed to an importer”—of great writers. Still Wild, then, is a collection by people who know the land they're writing about intimately.

Here’s Stegner describing a boy awake in the night: “Through one half-open eye he had peered up from his pillow to see the moon skimming windily in a luminous sky; in his mind he had seen the prairie outside with its woolly grass and cactus white under the moon, and the wind, whining across that endless oceanic land, sang in the screens, and sang him back to sleep.”

Book I’m hoping to read: Barbarian Days by William Finnegan

—Tyler Parker, editorial fellow

Harper Perennial Modern Classics

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

by Annie Dillard

Published in 1974, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek chronicles a year of life in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley—not just Dillard’s, but all life in the area, from protozoa up to the tops of the pines. Dillard stalks muskrats, watches a mantis lay eggs, hikes uphill to watch a thunderstorm, and stares into the ripples of the creek until the horizon makes her dizzy. Coupling her own detailed observations with extensive research on insect and animal life, she is humbled and horrified and overjoyed by nature’s sheer scope of cruelties and intricacies. And she passes on all this abundance and awe in prose that is precise and matter-of-fact as it is dizzyingly immersive.

Read Dillard next to the nearest bit of green you can find—a mossy wood, a backyard tree, even a house plant, if that’s all you’ve got. Sit in the shade and watch leaf-shadows play on the print. Lie on the grass and let ants wander over the pages, or flies hover and light on the spine. To emerge from this book is to wake from a dream world into one that’s the same, and real, and better. In Dillard’s words: “Go up into the gaps. If you can find them; they shift and vanish too. Stalk the gaps. Squeak into a gap in the soil, turn, and unlock—more than a —a universe. This is how you spend this afternoon, and tomorrow morning, and tomorrow afternoon. Spend the afternoon. You can’t take it with you.”

Book I’m hoping to read: The Vegetarian by Han Kang

—Rosa Inocencio Smith, assistant editor

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Labor of Love

By Moira Weigel

I should warn you: Choosing Labor of Love as a beach read might result in annoyance for the people accompanying you on your getaway. When I brought the book with me on a recent outing with friends, I couldn’t help but interrupt the peaceful silence, repeatedly (sorry, guys), to share some of the historical tidbits the book offers: “Whoa, in Colonial America, they had this thing called ‘bundling,’ which allowed courting couples to sleep next to each other—but, like, in sacks, with drawstrings at the neck!” “Until the 1920s, having a ‘personality’ was considered evidence of a mental disorder!” “Did you know that TGI Friday’s was the first singles bar?”

One moral here may be “do not bring me on your beach vacation,” but the other one is much more interesting: Dating is, in the broad arc of human affairs, an extremely recent invention. It is what happened, Labor of Love argues, when courtship left the private sphere—the realm of relatives and religion and meddling neighbors—and entered the public. And it is also what happened when love became a market phenomenon. It’s no accident, Moira Weigel writes, that many Americans are accustomed to using the language of economics—“on the market,” “sealing the deal,” “damaged goods,” “getting the milk for free”—when it comes to partnering up. It’s also no accident that, even in this age of increased gender fluidity and of ever-more-normalized feminism, the market logic of dating still tends to take for granted the notion that it is women who are the goods on offer: objects to be purchased, ultimately, by men.

Weigel wrote Labor of Love while researching her PhD in comparative literature; the book is inflected, as most good academic works will tend to be, with its author’s deep knowledge of her subject matter. And yet: Beach reading this is! Really! The book’s sweeping look at dating incorporates references to The Real Housewives and the flair factories of TGI Friday’s as easily as it does its analyses of Marxism and feminism and parietal rules—all in the service of exploring what any modern-day Tinderer will know to be true: that dating is, on top of everything else, work. But Labor of Love makes its case as cheerfully as it does compellingly. Weigel’s book is both intense and lighthearted, by turns easy and surprising, offering momentary delights as well as subtle hints about the future. It’s everything, really, that a good date should be.

Book I’m hoping to read: Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

—Megan Garber, staff writer

Grand Central Publishing

Before the Fall

By Noah Hawley

Here’s the thing about the mystery/suspense/potboiler genre: I just don’t have the patience for it. When a murder/rape/disappearance happens, why take 200 pages of thinly drawn characters and ridiculous chase scenes to find out what happens? I often just skip to the end. Why wade, after all, through chapters upon chapters of Hercule Poirot questioning everyone but the vicar’s cat?

But Noah Hawley’s Before the Fall isn’t a typical mystery. Perhaps that’s why I couldn’t put it down. The novel imagines that the head of a conservative news channel (ahem, Fox News) is a decent guy with two young kids and an artsy wife. His wife offers a banker friend and an artist acquaintance a ride on the family’s private jet on their way back to New York City. In the first few pages of the book, the plane crashes, killing all but two people on board.

Why did the plane crash? Why did some people survive? Is this really how the very rich live? These are the questions Hawley answers over time, through flashbacks that tell the backstories of each of the plane’s passengers, alongside a fast-paced window into the investigation. He also pokes fun at the 24-hour-news cycle, which mourns, with a vengeance, the death of one of its own.

Hawley is a TV writer, and as such, knows how to do structure in a way that makes the reader stay engaged. You want to know not just why this plane crashed, but why the characters on board have taken the paths they have that brought them to this jet on a foggy summer night. And by keeping two characters alive, he keeps you invested in their futures, too. Is the answer to the mystery the most satisfying explanation Hawley could have come up with? Well, no. But the journey of getting there is a fun one, more fun than it would have been to just skip to the end.

Book I’m hoping to read: I Am No One by Patrick Flanery

—Alana Semuels, staff writer

Random House

Shame and Wonder

By David Searcy

The big question about David Searcy's first book, the 2001 novel Ordinary Horror, was whether the protagonist, “a widower about 70 years old,” was at the center of a thriller or kind of losing it in a satire of suburban loneliness. Now approaching 70 himself, the Dallas author’s debut essay collection is similarly given to ambiguity and hidden meanings.

Searcy has perfected a voice that sounds like it's coming from somewhere inside you. It’s weird and wise, weightless and bone deep; a style distilled from what he calls “that engulfing moment of self-consciousness and doubt.”

Lesser essayists would be grateful just for Searcy’s aperçus. Of an oak tree initialed to death by lovers, he writes, “We are residual, after all.” On modernist design: “It’s so strange how things look strange devoid of ornament.” On finding a prize in your cereal box: “That something-out-of-nothing sort of power and unlikeliness—to which a child, so recently produced out of that powerful unlikeliness, would be especially sensitive.”

But Searcy’s thoughts aren’t just clever. They haunt you with mysteries that point upward. He remembers imagining outer space, at seven, the way science fiction still teaches us to, as “a place from which the world you know has been essentially removed. Where it remains implied, however … And maybe, somehow, amniotic.”

Sixty-three years later, Searcy writes with that same sense of pervasion, always conjuring what’s unseen yet felt. In an essay about a Chevrolet El Camino, for instance, he asks, like a fish in water, “Is metaphor everywhere? Of course it is. Once consciousness, once meaning gets a start it keeps on going. You get literacy and metaphor and God.”

Book I’m hoping to read: Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine by Diane Williams

—Zachary Hindin, assistant editor

Broadway Books

Close to Shore: A True Story of Terror in an Age of Innocence

By Michael Capuzzo

One hundred years ago this month, a 23-year-old man named Charles Epting Vansant swam into the Atlantic Ocean, near the New Jersey resort town of Beach Haven. A capable swimmer, Vansant was splashing with a retriever far beyond his fellow bathers when the dog turned suddenly and paddled back to shore. Soon, sunbathers began calling out in alarm, but their voices must have been muffled by the crash of the surf. Vansant, who was by then alone in the water, started swimming in after the dog—unaware that the fin of a great white shark had pierced the waves and was moving swiftly toward him. He had just reached the shallows when the shark seized his left leg, fatally severing his femoral artery as a crowd watched in horror.

Vansant’s death marked the first in a remarkable series of shark attacks in New Jersey waters over 12 days in July 1916—events brought chillingly to life in Michael Capuzzo’s 2001 non-fiction thriller, Close to Shore. Of the five people bitten that summer, four died. One man was so brutalized that a beachgoer, misidentifying his body and the spreading stain of his blood, alerted lifeguards to a capsized canoe with a red hull floating out at sea. Disconcertingly, two of the victims were swimming in a creek, some 15 miles inland, when the shark came upon them. In a sort of true-life, Victorian take on Jaws (in fact, these attacks inspired Peter Benchley’s novel), Capuzzo compellingly captures the panic that spread across the country a century ago, as sensational reports of a man-eating shark seeped inland from the Jersey coast. While the attacks of 1916 have largely been forgotten, the radical wariness of the open ocean that they injected into the American psyche remains strong today.

Close to Shore has its faults: moments of high drama are sometimes undercut by purple prose, and while Capuzzo conducted extensive research, certain details strain the limits of the reader’s trust that the book is a work of pure non-fiction. (How could Capuzzo possibly know that Vansant, who bled out shortly after being dragged half-conscious from the sea, felt a shiver travel down his spine seconds before the shark bit him?) But the vivid descriptions of the attacks—and the jolt of horrified empathy they deliver—tap successfully into a primal, and deeply gripping, fear of these ancient fish, instilling something just short of awe. Close to Shore gives new meaning to the term beach reading—emphasis on beach.

What I want to read next: Moby Dick by Herman Melville

—William Brennan, associate editor

Riverhead Books

The Paying Guests

By Sarah Waters

In Waters’s sixth novel, it’s 1922 in the London suburbs, the Great War is over, sons and brothers have been killed, the family money is gone, the servants have been let go, the country is changing, and 26-year-old Frances Wray is left with her aging mother to bat about their large, upper-crust home doing chores, making meals, and reading (and doing more chores). It’s immediately clear that Frances is a singular character: an unrepentant lesbian in an era when that was considered deviant, and a flawed but reflective, self-aware, and deeply good person.

When the Wray women take in boarders to make ends meet, Frances’s most personal truth is laid bare. Those tenants, Leonard and Lily Barber, are a young couple a few social-class rungs down the ladder from the Wrays, who are gratified by their new grand home. There are still chores, meals, and reading to pass the day, but now these tasks are amplified by the Barbers’ curious footsteps overhead, and by chance encounters in the hall, the kitchen, the yard. Even though it’s easy to get lost in the sleepy fog of chores and innocent spying, those footsteps overhead feel dangerous—and that fog begins to lift.

There’s a delicious affair at the center of the 2014 novel that starts joyfully, lustily. But Waters edges that happy love into darker territory—before, like springing a trap, she gives the reader an unexpected and accidental murder. (There’s a harrowing cover-up that brilliantly mirrors Frances’s daily chores.) The crime binds Frances to Lily in an uncomfortable pact that creates so much tension and excitement you suddenly can’t read fast enough. Waters pivots from a tale of English manners to a literary thriller swaddled in secrets on a dime.

A trial and its attendant anxieties shed light on more affairs, a pregnancy, and an illegal abortion—all of which make the reader and Frances question everything that’s come in the first half of the book. Suddenly, details that earlier seemed like anodyne scene-setting are revealed as far more troubling. And Waters has hidden her clues so deftly that the last quarter of the novel reads like a series of epiphanies as each clue slides into place—each one making things worse for Frances. It’s masterfully done.

Book I’m hoping to read: The Trespasser by Tana French

—Sacha Zimmerman, senior editor

Nation Books

Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching

By Mychal Denzel Smith

What does it mean to be a young black man living in America right now? On the one hand, President Obama’s election is a special piece of my own racial identity and an achievement that connects my own life with the famed struggle of my forefathers and foremothers. On the other, there’s the immediate reality of black people dying in the streets and a national climate that seems increasingly hostile to people who look like me. There’s something that’s both perfectly poetic and perverse about all that, but even now, after having thought about it for years, I can’t really nail down exactly what it is.

Luckily for me and for anyone else interested in this peculiar zeitgeist of black millennial-ness, the world has Mychal Denzel Smith and his wonderful Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching. Falling somewhere in the space between memoir and long-form critical essay, the book evokes the themes of its namesake by Ralph Ellison as a black bildungsroman, with Smith—or a version of him—torn between the twin forces of personal discovery and the responsibility of activism.

Unlike Ellison’s Invisible Man, or many other older explorations of black masculinity and social justice, Smith’s book takes a page from the personal essays that dominate certain online spaces today, breaching topics of misogyny and mental health in a naked and vulnerable way that’s long been at odds with the major formative view of black masculinity. Or, as Smith puts it, “every lesson my father ever taught me came back to the myth.” Smith’s book is about those myths, and how they’re interwoven with a constellation of other factors in our lives. While Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching may not have the answers, its attempt to define the undefined something buzzing about blackness feels like catching lightning in a bottle.

Book I’m hoping to read: The Obelisk Gate by N. K. Jemisin

—Vann Newkirk, staff writer

Fantagraphics

Patience

By Daniel Clowes

Clowes’ first graphic novel in over five years might be his weirdest one yet. It’s a love story for the ages, one that quite literally jumps across the psychedelic fabric of space and time as we know it. Jack, the book’s bitterly cynical protagonist, travels through time to solve a crime that could save everything he holds dear, stumbling upon some strange truths along the way, and never once missing the chance for some dark comedic insight.

While Patience is Clowes’ first foray into sci-fi and the fantastical, his pastel-toned panels are instantly recognizable: They radiate the same jaded sense of American suburbia that made his breakthrough work, Ghost World, a cult classic. The book makes space for some pretty remarkable existential revelations, but Clowes’ Bukowski-esque narration never feels smug. He seems to be enjoying himself with the art here, taking his time with colorful double-page spreads that illustrate dimensional shapeshifting in kaleidoscopic detail.

Patience is an irreverent, paranoid journey which, at its heart, speaks to the basic human fear of loneliness, and the desire to reshape our pasts.

Book I’m hoping to read: A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

—Arnav Adhikari, editorial fellow

Grove Press

Cosmos

By Witold Gombrowicz

Cosmos begins with the meandering adventures of Witold and Fuchs, two Polish students who travel through the countryside to avoid fights with family and coworkers that the author only sparingly elucidates. The students are both bored and overstimulated; their reaction to their mundane surroundings is to analyze every last detail as if each were a sign of something significant. So when they stumble upon a dead sparrow in the woods, hanging by a wire from a tree, their inclination toward analysis leads them to imagine themselves at the center of a rich mystery concerning the bird’s bizarre death.

Comedy ensues as Witold and Fuchs begin to scrutinize every last detail of their surroundings, certain that any passing element must be part of a vast configuration of potential clues. Witold, who narrates the story, writes that they encounter an “overwhelming abundance of connections, associations … How many meanings can one glean from hundreds of weeds, clods of dirt, and other trifles?” As the collection of clues grows exponentially, Witold and Fuch’s search to unravel the mystery of the bird begins to possess them.

In a way, Cosmos is a mystery told in reverse. Part of the joy in reading it is that you must navigate a host of tenuously related details and determine whether the main characters are comically—perhaps psychotically—overreaching, or if they have indeed stumbled upon a great, cosmic mystery.

The winner of the 1967 International Prize for Literature, Cosmos is consistently absurd in a frequently funny but often disturbing manner. Perhaps most alarming: As the characters struggle to analyze the tiniest details of body language, you’re forced to confront how absurd your own search for signs in the most mundane details of life may well be.

Book I want to read next: The Lowland by Jhumpa Lahiri

—Ben Rowen, editorial fellow

Little, Brown and Company

Gods Behaving Badly

By Marie Philips

It's been a few years since the summer when I devoured 2007’s Gods Behaving Badly, and the fog-roll march of time since then has obscured many details of the reading experience in my memory—save for an overriding feeling of total delight.

Philips imagines that the Greek gods of myth were not only real people but real people still alive in the 2000s, hiding out in a London group house where they hold down unglamorous jobs and squabble with one another using their ever-more depleted powers. A dowdy pair of mortals enters their lives when the playboy of the house, Apollo, gets struck by one of Eros's arrows, creating an unlikely love triangle that ends up necessitating an adventure to the underworld. It’s a high-concept book that provides simple pleasures—the kind of breezy, irreverent comedy with a hint of poignancy that can make life on Earth, briefly, more divine.

Book I’m hoping to read: A Brief History of Seven Killings, Marlon James

—Spencer Kornhaber, staff writer

Metropolitan Books

The Arab of the Future

By Riad Sattouf

“The Arab of the future goes to school!” proclaims Abdel-Razak, the father of Riad Sattouf, as he loads his reluctant family onto a plane for their next adventure. The Arab of the Future, a graphic memoir from Sattouf, offers a darkly comic look at his nomadic early life, which was guided by his father’s north star, pan-Arabism, before being thrown off-course by the stark realities their family encountered abroad.

Born to a French mother, Clémentine, and a Syrian father who met when both were students at the Sorbonne, Riad, a well-known cartoonist formerly at Charlie Hebdo, spent his younger years going wherever his father willed. As the only child from his large family to go to college, Abdel-Razak fervently believed in the power of education to transform the Arab world and help others “escape from religious dogma.”

Blindly passionate about the task at hand, and less than sympathetic to his family’s desires, Abdel-Razak spends their time in Libya explaining the unfamiliar, excusing the questionable, and justifying the unfair, including some of the ideals Muammar Qaddafi set forth in The Green Book. But even Abdel-Razak has had enough when Qaddafi proposes “teachers would now be farmers and farmers would be teachers.” After a quick pit stop in France, the family is off to a Syria ruled by Hafez al-Assad. Abdel-Razak, away for 17 years, no longer quite fits in, Clémentine is uncomfortable with the local traditions, and Raid is teased mercilessly for his mixed heritage and Western ways.

The Arab of the Future takes the reader into everyday life in Libya and Syria through the eyes of a young Riad, but most striking about the memoir is the shifting lens through which he sees his father. Abdel-Razak is “fascinated by politics” and compulsively drawn to these countries dominated by powerful rulers. In retrospect, Sattouf is just as fascinated by Abdel-Razak, and his memoir offers a study of the similar power his father wielded over his own family.

For a book encompassing weighty topics, including the struggle to assimilate and life dictated by political upheaval, The Arab of the Future still manages to feel buoyant, thanks in part to the artwork itself. It’s Sattouf’s irreverent humor, though, that strikes the right balance and makes for an amusing and thought-provoking summer read.

Book I’m hoping to read: The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears by Dinaw Mengestu

—Anna Diamond, editorial fellow

Vintage

Possession

By A.S. Byatt

Possession is a work of beautiful intricacy. Two literary scholars, Roland Mitchell and Maud Bailey, discover letters exchanged by two Victorian poets, Randolph Henry Ash and Christabel LaMotte. Using these letters, Roland and Maud reinterpret the poets’ verses to trace a clandestine love affair between them. In addition to prose, the novel comprises poetry in the Victorian style, as well as diaries, academic scholarship, and letters—all Byatt’s fictional creations, though they feel authentic.

Another author might struggle to blend such complexities of plot and form into one cohesive picture. But Byatt manages to do so. Throughout Possession, hers is a style as easily seen as it is read. She describes, for example, a girl on a stained-glass window: “One cheek moved in and out of a pool of grape-violet as she worked. Her brow flowered green and gold. Rose-red and berry-red stained her pale neck and chin and mouth.”

No matter that Byatt’s lengthy novel might possess its reader for long periods. In the end, it also offers a picture to rival any summer sunset.

Book I’m hoping to read: The Dying Grass by William T. Vollmann

—Jake Pelini, editorial fellow

Hogarth

The Vegetarian

By Han Kang

Some individuals decide to stop eating meat because of its perceived cruelty towards animals; for Yeong-hye, the central character of The Vegetarian, her choice brings into stark relief the brutish nature of her own species. Yeong-hye, a South Korean housewife described (by her own husband, nonetheless) as “unremarkable,” wakes up one morning from grotesque nightmares and declares herself an herbivore. Vegetarianism isn’t widespread in South Korea, and Yeong-hye’s decision prompts confusion, concern, and fury from her family, which culminates in violence.

Apart from brief, often surrealistic interjections, the story isn’t told from Yeong-hye’s perspective. By focusing on the reactions of those around her, The Vegetarian emphasizes the repercussions individuals (particularly women) face when making decisions about their own bodies. The first two sections of the three-part novella offer the viewpoints of Yeong-hye’s husband and brother-in-law, respectively; both see her body as a reflection of their own identity and ego. Her husband believes a more conventional wife would help him rise at his company; instead, Yeong-hye refuses to wear a bra to an awkward business dinner where her dietary habits become a subject of derision and unease.

The unconventionality that infuriates Yeong-hye’s husband ultimately attracts her brother-in-law, an unsuccessful artist supported by his business-savvy wife. He seeks to use Yeong-hye’s body as a literal canvas—blurring the line between artistic expression and erotic proprietorship. The final section offers a view from his wife, Yeong-hye’s sister, whose genuine concern for her sibling further complicates the distinction between paternalism and invasive control by calling into question Yeong-hye’s own agency and sanity. By refusing to eat animals, Yeong-hye turns the socially accepted carnage of meat-eating toward herself.

Book I’m hoping to read: Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy

—Isabel Henderson, editorial fellow

W. W. Norton & Company

Flash Fiction International

Edited by James Thomas, Robert Shapard, and Christopher Merrill

At just 190 pages, featuring stories as long as a few pages or as short as a single paragraph, Flash Fiction International looks like a quick read. It isn’t.

These are stories that will leave you gasping for air, reeling, taking a walk around the block to clear your head. Flash fiction—also known as “microfiction,” “very short stories,” or “wait, it’s over already?”—is a genre as old as the parable, but it has come to new life on the Internet, and is flourishing in little-seen corners around the globe, from Israel (source of the satirical first selection, “The Story, Victorious”) to Cuba (Virgilio Piñera’s darkly funny “Insomnia”) to Taiwan (the fragile, tragic “Butterfly Forever”).

Flash Fiction International invites the reader to take in at a glance the breadth and inventiveness of modern fiction, what life and imagination is like everywhere in the world all at once. These stories are bullets, fired at lethal speed into the mind.

Book I’m hoping to read: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon

—David Somerville, design director

Picador

Lila

By Marilynne Robinson

I came to Lila after I’d been given a copy of Gilead, the first book in Robinson’s trilogy centered on the town of Gilead, Iowa. From Barack Obama to Leslie Jamison, many people have written about the ways in which these novels (as well as Home, the second book of the three) have mattered to them.

Bu what sticks in my mind from Lila is the image at the novel’s opening: a sick, crying child is left on a cold porch. A woman wraps the child in her shawl, names her Lila, and the two wander across the Midwest “with no place to go.”

An adult Lila drifts into Gilead, and wanders into a church service led by the much older Reverend John Ames (the main character in Gilead). The rest of the book follows Ames and Lila’s courtship and marriage, as well as Lila’s struggle to reconcile her new, more secure circumstances with a past marked by instability, violence, and loneliness.

While working her way through the Bible for the first time, Lila comes back to the book’s beginning via a cryptic proverb in “Ezekiel” about an abandoned child. The scene echoes the book’s first pages, and serves as a loose metaphor for the shape of Lila’s life. As she wrestles with the story, Lila begins to create a tenuous peace with her past, and open up about her ghosts—including a stint in a St. Louis whorehouse and a painful parting with her adopted mother.

None of Lila’s reflections is neatly wrapped up: there is no clean narrative at the end, and that disorder doesn’t hurt her newfound peace. As Leslie Jamison wrote for The Atlantic, Robinson’s writing doesn’t shy away from “complexities—the solitude that endures inside intimacy, the sorrow that persists beside joy.” Interwoven with thoughtful passages on faith, loneliness, and a few nuggets of Christian theology, Lila makes for a powerful, and ultimately uplifting read.

Book I’m hoping to read: Maurice by E.M. Forster

—Joseph Frankel, editorial fellow

Liveright

Our Sister Republics

By Caitlin Fitz

Americans often place themselves—I should say, ourselves—at the forefront of history. When high-school teachers discuss Western European political philosophy authored hundreds of years before 1776, they sometimes present it as a steady march toward prosperity and freedom—a march that irreversibly ends in George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and the postwar American Century.

Caitlin Fitz tells the story of one the first times Americans contorted global events to make it fit this happy story. In the 1810s and 1820s, South America was rocked by a series of anti-imperial revolutions. U.S. Americans adopted the revolutionaries’ cause as their own—sending money and arms, drinking to their health on July 4, even christening their towns and sons “Bolivar.” U.S. politicians, businessmen, newspaper editors, and even wives saw the South American revolutions as an extension of the spirit of 1776.

As Fitz tells, though, these joyous feelings splintered once some U.S. Americans saw their own country less as a radical project in equality and more of a testament to white exceptionalism. Suddenly, the rebellions in the South seemed not just anti-imperial, but antislavery—and U.S. support faded accordingly. Fitz’s elegantly written history tells an early American story of reverse racial progress.

Book I’m hoping to read: My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante

—Robinson Meyer, associate editor

Picador

The Sellout

By Paul Beatty

“This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man,” the unnamed narrator says in The Sellout, “but I’ve never stolen anything.” With that, it’s off to the races in what quickly became the most memorable book I read this year. The book tells the story of a narrator with a sensitive soul, born in the fictional “agrarian ghetto” of Dickens, a city in the southern outskirts of LA. He was raised by a single father, a sociologist who imposed racially charged experiments upon him in his youth. The guy spends his days growing robust crops of fruit and weed (he gives his strains names like Perspicacity and Anglophobia). Ultimately, after a series of unfortunate events, he decides to (with the help of a few excellent supporting characters) reinstate slavery in his own home and segregate the local high school—actions that bring him to be charged at the Supreme Court.

The Sellout is a brutally fun read, but don't misunderstand it as unserious. Some scenes are all too real; toward the beginning of the book, one character is shot dead by a police officer for essentially driving while black. Beatty delivers brilliant humor with a caustic bite, and parts can be uncomfortable to sit through. I paused on so many pages just to unpack the myriad historical and pop-culture references. But it was unlike anything else I’d read before, at once side-splitting and thought-provoking. It’s a book that forcibly ejects you out of your comfort zone, and once you’re there, you’re going to want to linger a while.

Book I’m hoping to read: White Teeth by Zadie Smith

—Emily Jan, associate editor

July 29, 2016

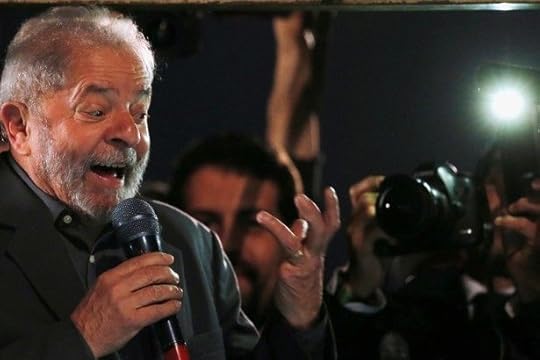

The Charges Against Brazil's Lula

NEWS BRIEF Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the man who presided over Brazil’s economic miracle in the early 2000s, became the highest-profile casualty of the widening corruption scandal at Petrobras, the state-run oil firm. A federal court in Brasilia formally charged Friday the former Brazilian president with obstruction of justice in the case.

:

Lula was previously under investigation in various jurisdictions in a sprawling corruption investigation focused on state-run oil company Petroleo Brasileiro SA but is now officially a defendant.

In March, as we previously reported, Lula was detained and taken to the Sao Paulo airport for questioning. Brazilian police executed 33 search warrants and 11 arrest warrants at the time. Two of them were in Sao Bernardo do Campo, in Sao Paulo state, where Lula lives. Police said Lula received illegal kickbacks from the corruption at Petrobras.

Here’s the background to the case:

At issue is Operation Car Wash, the investigation into alleged corruption and money laundering at Petrobras, the crown jewel of Brazilian state enterprises. Many of those activities are alleged to have taken place between 2003 and 2010, when Lula was president. Executives at the firm are accused of overcharging for contracts with construction companies, and funneling the difference either to themselves, others, or political parties, including Lula’s Workers Party.

The scandal has ensnared some of Brazil’s biggest political and business leaders, raised questions about President Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s chosen successor, and tainted the former president’s legacy as well.

Lula, as the former president is known, is a former trade-union leader who ascended to the Brazilian presidency in 2003 and remade his country into a regional economic powerhouse. Rousseff succeeded him in 2010. She was suspended in May over a separate scandal involving fudged economic data and is facing an impeachment trial. The verdict in that trial is expected in the middle of next month, during the Rio Olympic.

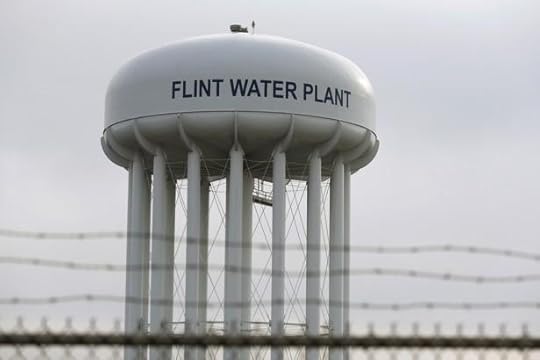

More Charges in the Flint Water Crisis

NEWS BRIEF Six more Michigan state employees were charged Friday in connection with the Flint water crisis.

Announcing our third legal action of the Flint Water Investigation right now. pic.twitter.com/K9qgwzb9nb

— A.G. Bill Schuette (@SchuetteOnDuty) July 29, 2016

State Attorney General Schuette announced the six additional charges at a news conference. Nancy Peeler, Corinne Miller, and Robert Scott, all officials with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, will be charged with misconduct in office, conspiracy, and willful neglect of duty.

Liane Shekter-Smith, Adam Rosenthal, and Patrick Cook, who were with the Department of Environmental Quality, will also be charged. Shekter-Smith will be charged with misconduct in office and willful neglect of duty; Cook with misconduct in office, conspiracy, and willful neglect of duty; and Rosenthal with misconduct in office, tampering with evidence, conspiracy, and willful neglect of duty.

“Each of these individuals attempted to bury or cover up, to downplay or to hide information that contradicted their own narrative, their story … these individuals concealed the truth and they were criminally wrong to do so,” Shuette said.

In addition to the individuals charged, civil suits have been filed against Lockwood, Andrews & Newman, the engineering firm, and environmental consultant Veolia North America on the grounds that the companies had the “knowledge and the ability” to stop the crisis. Both companies have denied any wrongdoing.

The investigation is ongoing, and Shuette said it will continue until “we have delivered justice for Flint.”

Two Michigan Department of Environmental Quality officials and one City of Flint employee were brought up on charges related to the water crisis last April.

Flint has been under a state of emergency since elevated levels of lead were discovered in the city’s water supply in 2014. The state of emergency has been extended until August.

An Olympic Ban on All Russian Weightlifters

NEWS BRIEF The International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) banned Friday all Russian weightlifters from competing at the Rio Olympics, justifying its decision because of the widespread evidence of state-involved doping, and saying Russian weightlifters brought the sport “into disrepute.”

Eight Russian weightlifters were scheduled to compete in the games. In its decision, the IWF said the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided to empower each sport with the power to ban, or not to ban, Russian athletes given the doping claims. The IWF cited that ruling, which said:

“Under these exceptional circumstances, Russian athletes in any of the 28 Olympic summer sports have to assume the consequences of what amounts to a collective responsibility in order to protect the credibility of the Olympic competitions, and the ‘presumption of innocence’ cannot be applied to them. On the other hand, according to the rules of natural justice, individual justice, to which every human being is entitled, has to be applied. This means that each affected athlete must be given the opportunity to rebut the applicability of collective responsibility in his or her individual case.”

The IWF said a reanalyses of the urine samples of eight Russian weightlifters showed seven used performance-enhancing drugs. The IWF called these findings “extremely shocking and disappointing.”

“The integrity of the weightlifting sport has been seriously damaged on multiple times and levels by the Russians, therefore an appropriate sanction was applied in order to preserve the status of the sport,” the IWF wrote in a statement.

The IWF also referenced the 100-page report commissioned by the World Anti-Doping Agency, which found state complicity in a scheme to cover up Russian athletes who used performance-enhancing drugs. The investigation alleged that Russia’s intelligence agency, the FSB, helped athletes cheat.

Don't Think Twice Nails the Tragedy of Comedy

If comedy is tragedy plus time, then Mike Birbiglia’s new film Don’t Think Twice focuses on time—the interim period in which the sad twists and turns of fate transform into humor. The tale of an improv troupe struggling to climb to the next rung of the comedy ladder without climbing over each other has a granular, true-to-life appreciation for its subject from its writer and director, himself a comedian, but manages to avoid feeling like inside baseball. Birbiglia is telling the story of the UCB generation of comedy to an audience that might not even know what UCB stands for—and he does it by making it a universally recognizable tale of artists trying to create work they can be proud of.

Birbiglia made his feature debut in 2012 with Sleepwalk With Me, a filmed version of his one-man show, which essayed his breakup with his fiancée, his career as a stand-up comic, and his struggles with sleepwalking. Though small in scale, it had a strong sense of its characters and their emotional shortcomings, while also communicating the energy and passion of stand-up comedy on screen. With Don’t Think Twice, he ventures into the even tougher ground of improv (the word alone may summon flashbacks to stilted college shows), while focusing on a bigger, messier ensemble. The result is still low-key but similarly intelligent—it’s laugh-out-loud funny, while never shying away from the narcissism and personal shortcomings that fuel many a performer’s life. Sleepwalk With Me was promising, and Don’t Think Twice delivers on that promise: It’s one of the best comedies of the year.

As he did in his last film, Birbiglia stars, writing himself as perhaps the most unlikable character of the bunch. As Miles, he’s the leader of The Commune, a well-regarded improv group that toils away with weekly shows in the comedy theaters of New York, praying that TV casting agents will drop by. Miles is approaching 40, but still dating girls right out of college, charming them into his loft bed with stories of his near miss at a spot in the cast of Weekend Live (the film’s Saturday Night Live analogue).

Along with Miles, The Commune is made up of Allison (Kate Micucci), a mousey cartoonist; Bill (Chris Gethard), a neurotic sad-sack who seems ever-prepared for the worst; Lindsay (Tami Sagher), whose family wealth inspires jealousy among the group; and Jack (Keegan-Michael Key) and Samantha (Gillian Jacobs), a couple who seem bound for stardom, though only Jack seems to have the ambition to follow through on his talent. Birbiglia takes great pleasure in laying out each character’s behind-the-scenes awkwardness, then showing them snap into performer mode onstage. The improv itself feels remarkably true to life: sometimes uproarious, other times in search of a groove, with things working best when the team shies away from showboating.

The real joy of Don’t Think Twice, though, comes in the tragedy, which ranges from minor spats to professional jealousy to deaths in the family. The film’s core premise is that these six performers are all in search of fame, but we know they’re not all going to make it. Birbiglia gets to the meat of that plot quickly and efficiently—some members of The Commune get asked to audition for television, while others look on anxiously—because he knows the real drama comes from whether or not they can stay friends and allies in the face of wealth and fame.

The twin problems of any film about the wrenching process of making comedy are that they have to be funny without forgetting to be serious. That’s the achievement of Don’t Think Twice, which does a beautiful job exploring the myriad ways that comedians exploit their own tragic circumstances to score meaningful laughs. There’s no scene sadder, yet hilariously apt, than one about a car ride in the middle of the movie, where the troupe returns from visiting Bill’s sick father in the hospital. After a few moments of weighty silence (something few comedians can abhor), the gang quickly starts spitballing jokes about him, the only way they know to wrestle with their emotions in the face of something so stark. Just like the film as a whole, it’s heartbreaking—and yet, you can’t help but laugh.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower