Ned Hayes's Blog, page 44

July 4, 2015

All I see is fireworks by (Guilty—Cubicles)

se17enteen:

Movement. by Crusade. on Flickr.

June 30, 2015

Convergence... putting it all together (Part 6 - How to Write Fantasy Fiction)

One final example in a work of contemporary literature may serve to illuminate the power that can be found in combining all these techniques. A truly masterful writer finds no need to be explicit about anything, but instead spells out only the characters, their basic emotional motivations, the realistic cues of the setting they are in, and describes—only at the most basic level—what supernatural actions they might take as they strive to achieve their goals. A pertinent example can be found in Cormac McCarthy’s haunting novel The Road.

One final example in a work of contemporary literature may serve to illuminate the power that can be found in combining all these techniques. A truly masterful writer finds no need to be explicit about anything, but instead spells out only the characters, their basic emotional motivations, the realistic cues of the setting they are in, and describes—only at the most basic level—what supernatural actions they might take as they strive to achieve their goals. A pertinent example can be found in Cormac McCarthy’s haunting novel The Road.

In many circles, McCarthy’s novel has been seen as a masterwork of apocalyptic realistic fiction. Yet the mysterious nature of the book and its frequent use of supernatural language call out for an other-worldly explanation. In fact, the novel’s title in an early draft was “The Grail,” a title that provides a hint of the great narrative arc in which a failing father embarks on a great quest to save his son, whom he imagines as a “chalice,” the symbolic vessel of divine healing in a kingdom suffering from a disastrous blight (McCarthy 64). In fact, at least one critic believes the destruction of The Road’s world must have “a supernatural cause” (Grindley 12). As Lydia Cooper points out in her estimable critique of the novel, the novel points to a mythological reality beyond the “straight story.” Throughout The Road, we find motifs of a Waste Land, a dying Fisher King, and a potentially unattainable healing balm in a holy fire and a Christological cup (Cooper 230). In all of these references, careful readers may see particularly pointed supernatural metaphors. These fantastic elements hint at supernatural allegory and mythological motif.

However, unlike Tolkien’s work, the overt quest is rarely named, and the need for salvation is only stated briefly and obliquely. The story carries the seeds of supernatural salvation in its heart, always implicitly and always without the need for an “info-dump” of scaffolding explanation. Nearly everything is withheld from the reader, and any hint of the supernatural must be discerned within the poetic and careful descriptions McCarthy provides to his readers.

As The Road opens, there is never an overt statement about what happened to land the main characters in their predicament. The story opens with these portentous lines: “When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him. Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before” (McCarthy 3). The apocalypse is upon them. Yet there is the possibility of supernatural help. After a description of night animals and dawn coming across a valley filled with blowing ash and smoke, the main character states in internal monologue: “He knew only that the child was his warrant… If he is not the word of God God never spoke” (McCarthy 5). This statement is for many pages the only mention of a salvific action or “magic” that may attend upon the child in his care, yet this mention of a possible miraculous “warrant” turns out to be the motivation for much of their long trip across the ruined countryside.

Furthermore, the actual events that led to the devastation across the apocalyptic landscape in which they travel are never explicitly stated. There is a description of “A long shear of light and then a series of low concussions,” followed by “a dull rose glow” (McCarthy 52). All of this implies—but never overtly states—some sort of cataclysmic intervention in the natural order, which could be anything from a nuclear bomb to a magical blast. A further explanation is never offered. Instead, the man recalls conversations from the past—in one such mention he states “We’re survivors,” followed by his wife contradicting him by saying “We’re not survivors. We’re the walking dead in a horror film” (McCarthy 55). For much of the book this description is an apt one, as the man and his son travel across a blasted terrible landscape full of horrors.

Many moments in The Road carry a double meaning, walking that tight-rope between both realism and magical activity. First, there is often an overt and literal meaning of activity—the man tells the boy that he must “carry the fire,” which in the context of this story means to keep an actual fire going, and bear with one the banked coals for the next morning’s flame. Yet this idea of “carrying the fire” repeatedly takes on a double meaning of hope and possible magic. Notably, near the end of the novel, the boy finally encounters another “good” human being, and he asks this new character repeatedly—as a test of humanity—whether or not he is, in fact, “carrying the fire” (McCarthy 283). The new character deflects this inquiry, stating that the boy is “a little weirded out,” which is a further implicit signal that the question goes beyond a literal fire into a matter of metaphysics and potential supernatural activity.

Many moments in The Road carry a double meaning, walking that tight-rope between both realism and magical activity. First, there is often an overt and literal meaning of activity—the man tells the boy that he must “carry the fire,” which in the context of this story means to keep an actual fire going, and bear with one the banked coals for the next morning’s flame. Yet this idea of “carrying the fire” repeatedly takes on a double meaning of hope and possible magic. Notably, near the end of the novel, the boy finally encounters another “good” human being, and he asks this new character repeatedly—as a test of humanity—whether or not he is, in fact, “carrying the fire” (McCarthy 283). The new character deflects this inquiry, stating that the boy is “a little weirded out,” which is a further implicit signal that the question goes beyond a literal fire into a matter of metaphysics and potential supernatural activity.

The story itself asks questions about if and how the human project may be preserved. But the secondary story asks other questions as well, about the role of the supernatural in our world, and our ability to find meaning in that other reality. All during the forward momentum across the countryside, they are haunted by supernatural possibilities. The idea of a “God called moment” rises repeatedly in the story. Near the end of the novel, the man is confronted once more, on a distant beach, by what he feels God has called him to do. He hears something speaking to him: “A sound without cognate… something imponderable shifting out there in the dark” which speaks to him, and which makes him ask questions like these: “What time of year? What age the child?… What will you say?” (McCarthy 261). These strange questions are asked of the man by himself—or by some never-named other voice—throughout the novel, leading to a double-voiced sense of mission that becomes a motivating factor for the man’s insistence that the boy should live.

Finally, the man’s questions to the larger disembodied voice in his head seem to resolve just before his death with these critical lines of hope: “Goodness will find the little boy. It always has. It will again” (McCarthy 261). This idea of “Goodness” is a never-named supernatural possibility in the story. When the idea of some greater “Goodness” is coupled with the Christological idea of “carrying the (holy) fire,” any careful reader begins to feel an overriding sense of hope in the midst of this darkly despairing narrative. Of course, this sense of hope finds resolution in the story itself through the survival of the boy in the hands of someone who has children himself, and thus is one of the “good guys.” The magic of hope brings the universe of this story to completeness.

McCarthy accomplishes all of this without once explicitly naming his main characters, naming the situation they are in, or overtly mentioning the supernatural possibilities inherent in his narrative. Every possibility of the supernatural in The Road is mysterious and evanescent: all these elements at play together conspire to create a superlative narrative experience.

Conclusion

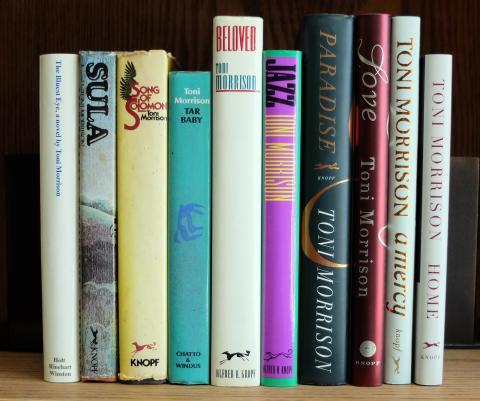

The insight into fictive techniques gained by the analysis of the works of masters such as Toni Morrison, Barbara Hambly, and Cormac McCarthy is useful to me only insomuch as it can be applied to my own writing. I have written historical fiction and contemporary fiction—stories set in particularly grounded places that I can actually visit and experience. Now that I am working in narratives that are “ungrounded” by the constraints of our present reality and our historical context, questions of intent, metaphorical content, and the uses of enchantment or the fantastic are often on my mind. Why is magic necessary to a story? How does one evoke a metaphor through fantastic means and not make it hackneyed or trite? Can supernatural images add to a story’s depth, rather than distracting the reader from the story’s characters?

My recent work in the novel-in-formation Wilderness of Mirrors attempts to combine both deeply researched historical knowledge about the Middle East, China, the War on Terror, and the history of the CIA with a fantastic and otherworldly story about Chinese spirits of the air—known as tian-long—and their possible (fictive) interactions with human beings. Like Marquez and Chabon, I hope to use the fantastic elements in this fiction to add a depth of insight into the emotional lives of my main characters, and give readers a new and different perspective. I do believe that fantastic literature can communicate profound metaphors for human experience, and I intend my use of magic in this novel to provide access to those metaphors. In the end, my desire is to produce a literature which is truly multivalent and goes beyond typical “spy” or “supernatural” writing into the kinds of haunting territory charted for us by Thomas Pynchon and Philip K. Dick.

My recent work in the novel-in-formation Wilderness of Mirrors attempts to combine both deeply researched historical knowledge about the Middle East, China, the War on Terror, and the history of the CIA with a fantastic and otherworldly story about Chinese spirits of the air—known as tian-long—and their possible (fictive) interactions with human beings. Like Marquez and Chabon, I hope to use the fantastic elements in this fiction to add a depth of insight into the emotional lives of my main characters, and give readers a new and different perspective. I do believe that fantastic literature can communicate profound metaphors for human experience, and I intend my use of magic in this novel to provide access to those metaphors. In the end, my desire is to produce a literature which is truly multivalent and goes beyond typical “spy” or “supernatural” writing into the kinds of haunting territory charted for us by Thomas Pynchon and Philip K. Dick.

As we’ve seen in Beloved and The Road, the supernatural can indeed be very powerful in a story, but it is most potent when it is spoken of in whispers and in subtext—rarely overtly and seldom with the need for any kind of explicit explanation. The power of a character-driven narrative can have a greater import when magic has a cost. Supernatural acts that take place can also have more power when their presence is grounded in a realistic sensory experience: if we see, hear and taste what is happening, then we believe it could be real. Finally, when important moments of magic are withheld, we also find the implications may lead us into readings that have the deeper flavor of allegory and mythology, instead of merely plot-driven fantasy. Use of these techniques in my own work will, I hope, enable me to create a literature that communicates on multiple registers, singing to my readers of both the world they live in and the possibilities of worlds beyond.

PART 1: Introduction (Writing Fantasy Fiction)

PART 2: Character Matters (Writing Fantasy Fiction)

PART 3: Grounding Magic in Reality (Writing Fantasy Fiction)

PART 4: The Sorcery of Withholding (Writing Fantasy Fiction)

PART 5: Working Magic by Implication (Writing Fantasy Fiction)

June 29, 2015

Working Magic by Implication -- (Part 5 - How to Write Fantasy Fiction)

Magic contains acts that supersede our reality, and thus are known as “supernatural.” As supernatural, these acts necessarily violate physical laws and partake of a reality that is mythological, allegorical, and otherworldly. If these alternate ways of seeing and knowing are explained and dissected at depth, they lose their ability to entrance and enthrall readers. Therefore, it is necessary for a writer to keep the magical explanations at arm’s length and refuse to spell out the mystery in great detail. Even books that are ostensibly about learning magic—such as Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogies and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter saga—use the act of learning magic to unveil the fact that there are “greater magics” that cannot be understood by the merely mortal characters who encounter these mysteries. In Earthsea, it is the mystery of the human heart’s capacity for evil, and in Harry Potter, both love and death are ultimate mysteries that confront the characters and the readers with their insoluble nature.

Magic contains acts that supersede our reality, and thus are known as “supernatural.” As supernatural, these acts necessarily violate physical laws and partake of a reality that is mythological, allegorical, and otherworldly. If these alternate ways of seeing and knowing are explained and dissected at depth, they lose their ability to entrance and enthrall readers. Therefore, it is necessary for a writer to keep the magical explanations at arm’s length and refuse to spell out the mystery in great detail. Even books that are ostensibly about learning magic—such as Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogies and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter saga—use the act of learning magic to unveil the fact that there are “greater magics” that cannot be understood by the merely mortal characters who encounter these mysteries. In Earthsea, it is the mystery of the human heart’s capacity for evil, and in Harry Potter, both love and death are ultimate mysteries that confront the characters and the readers with their insoluble nature.

In fact, the naming of explicit artifice and the spelling out of its elements functions to disrupt the metaphor, to call attention to the artifice, instead of letting the stories and the metaphors buried in those stories resonate deeply in our reading experience. Many writers refer to the work of an explicit outline and an explanation of the world-building as “scaffolding,” and often it is tempting to retain such “scaffolding” even when the scene is set and the characters are in motion. Such scaffolding is often contained in summary passages that are cut from the “scene” of the final work. All too often in works with supernatural elements these are retained.

One example of such summary scaffolding can be found in Clive Barker’s The Great and Secret Show. In this story, an early scene of a postal employee encountering strange missives is then “scaffolded” by a passage that describes Barker’s entire story and spells out details in an explicit manner:

There was a war waged in America that year, perhaps the bitterest and certainly the strangest ever fought on, in or above its soil. [… . ] As he’s sworn, Fletcher willed an army from the fantasy lives of the ordinary men and women he met as he pursued Jaffe across the country, never giving him time to concentrate his will and use the Art he had access to. He dubbed these visionary soldiers hallucigenia [….] Fuelled by a passion for each other’s destruction which had long ago escalated beyond the issue of the Art and its possessing… (Barker 45-46).

There was a war waged in America that year, perhaps the bitterest and certainly the strangest ever fought on, in or above its soil. [… . ] As he’s sworn, Fletcher willed an army from the fantasy lives of the ordinary men and women he met as he pursued Jaffe across the country, never giving him time to concentrate his will and use the Art he had access to. He dubbed these visionary soldiers hallucigenia [….] Fuelled by a passion for each other’s destruction which had long ago escalated beyond the issue of the Art and its possessing… (Barker 45-46).

This passage does not describe the “War” at all, but instead simply states that such a war is in existence, and names—explicitly—magic as an “Art” and also gives overt names to the “soldiers” that the main character Fletcher is using. It is always a bad sign when the reader must be told new and different names for common concepts like magical acts and soldiers fighting for one side or another.

A good test for the necessity of such overt naming is often to simply pretend that the story is happening in a realistic historical context, and whether or not in that context the need to know the names of the activities would be necessary to capture the reader’s attention. For example, in a novel set in the Napoleonic wars, is it necessary for the reader to know precisely the duties of a dragoon, or to know the precise weight and measure of the cannon balls and other munitions used during that war? If not, it is also not necessary for a reader to know the naming of so-called “magical” soldiers or munitions.

Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, a classic in the field of fantastic literature, is explicitly a magical quest story replete with odd and mythological creatures, yet on a deeper level it is an intense meditation on obsession, addiction, and human perseverance in the midst of personal addiction. It is a story of loss, of friendship, and of how one becomes married and indebted to one’s obsessions. The fantastic and the supernatural are merely one story among many ways of reading the story in the minds of Tolkien readers. Here is the first paragraph that names Gandalf as a “wizard” in the Lord of the Rings, at the end of the first chapter:

Take care of yourself! Look out for me, especially at unlikely times! Good-bye!’ [said Gandalf]. Frodo saw him to the door. He gave a final wave of his hand, and walked off at a surprising pace; but Frodo thought the old wizard looked unusually bent, almost as if he was carrying a great weight. The evening was closing in, and his cloaked figure quickly vanished into the twilight. Frodo did not see him again for a long time (emphasis mine: Tolkien Fellowship 50).

In fact, Gandalf the “wizard” does not re-appear in the narrative for nearly ten years, and when he does re-appear, it is only to stay the night and then to discuss ancient history and “shadows of the past”—it is not to cast bolts of energy or throw his sword at elfs or “Shades.” During those ten years, basic acts of historical realism take place in the novel: fields grow crops, people grow older, communities form closer bonds. No external acts of magic take place. No overt explicit actions are named or “wars” are described—even though during this exact period in the novel, a war machine is in motion, and is being built by an oppressing force.

In fact, Gandalf the “wizard” does not re-appear in the narrative for nearly ten years, and when he does re-appear, it is only to stay the night and then to discuss ancient history and “shadows of the past”—it is not to cast bolts of energy or throw his sword at elfs or “Shades.” During those ten years, basic acts of historical realism take place in the novel: fields grow crops, people grow older, communities form closer bonds. No external acts of magic take place. No overt explicit actions are named or “wars” are described—even though during this exact period in the novel, a war machine is in motion, and is being built by an oppressing force.

In fact, it is interesting to note that although magic apparently “exists” in the world of Middle-Earth, it is rarely if ever exercised, and when it is exercised, it is not seen onstage in the course of the narrative. For a story that concerns itself with a wizard, it’s notable that in the “prequel” Hobbit novel, no magical act is seen from Gandalf until the narrative is halfway over, and that activity constitutes merely the lighting of a handheld “light” in a cave in the mountains. Even when the company is clearly in danger from Trolls and other creatures, there is no magical intervention from any party.

In the Lord of the Rings trilogy itself, Gandalf and other wizards don’t demonstrate magical abilities until late in the story, and only then in a way that might well be sleight-of-hand, not real “magic” at all. The story concerns itself not with magic, but with activities that are not at all magical—the trudging through a rainy landscape full of mud and rocks; the hunger and deprivation on a difficult trip; fending off attacks by predators (by non-magical means); getting lost in a forest; conflicts among friends, and irritations over roles on a collaborative journey. One almost wonders if it is at all useful to have someone along who seems to carry the title of “wizard.”

In fact, this seems to be part of Tolkien’s point—and the “magic” of his choices in this narrative. Even Gandalf is only named as wizard by a few other characters, once or perhaps twice, and he never claims any specific powers himself. The “fantasy” aspect is a thin veneer over a difficult journey and a very human quest against great odds. The great saga of the Lord of the Rings grounds itself in a narrative of human endeavor and perseverance. It is not, at heart, a story at all about magical events or supernatural interventions. Because the story and their realistic setting take precedence, Lord of the Rings speaks on multiple levels and communicates multiple levels of truth. If the “magical” or “supernatural” elements remain unnamed, then the story becomes more powerful on the “fantastic” and resonates as a truly multivalent narrative.

In fact, this seems to be part of Tolkien’s point—and the “magic” of his choices in this narrative. Even Gandalf is only named as wizard by a few other characters, once or perhaps twice, and he never claims any specific powers himself. The “fantasy” aspect is a thin veneer over a difficult journey and a very human quest against great odds. The great saga of the Lord of the Rings grounds itself in a narrative of human endeavor and perseverance. It is not, at heart, a story at all about magical events or supernatural interventions. Because the story and their realistic setting take precedence, Lord of the Rings speaks on multiple levels and communicates multiple levels of truth. If the “magical” or “supernatural” elements remain unnamed, then the story becomes more powerful on the “fantastic” and resonates as a truly multivalent narrative.

There are many other examples in contemporary and classic literature. As we saw in Beloved, Toni Morrison performed a perfect act of “magic” without ever naming precisely what was happening. As a further example, in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the protagonist refers to himself as a “monster” often, but is this not the case for any human being in the grip of doubts about their parentage and their purpose? He never calls himself a “revenant” or a “zombie,” although technically he may be exactly these things. Instead, we are inside the creature’s head, and like Kafka’s famous cockroach-man, we are led to experience his reality. To cite yet another pertinent example, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is also never referred to as a specific kind of unearthly creature, and thus the story becomes an obsessional metaphor for Victorian neuroses about sexuality itself and sexual obsession.

READ the NEXT SECTION…. in which I wrap up my series on Writing Fantasy into Fiction >>

Working Magic by Implication — (Part 5 – How to Write Fantasy Fiction) was originally published on NedNote

June 28, 2015

The Sorcery of Withholding - (Part 4 - How to Write Fantasy Fiction)

The best stories feel as if you have simply stepped inside them and that the events of the story are simply happening. Many things are never explained. For example, few writers describe the sky or the ground in detail, and few writers describe the breath going in and out of the characters’ mouths before and after they speak. The reason these things are ignored is that they are simply assumed to be present. There is no explanation necessary, and if you are in media res in the story, there is no need for a prologue explanation or an after-the-fact explanation.

One further example can help to make this point. In the first six pages of Christopher Paolini’s high-fantasy novel Eragon, multiple acts of fully described supernatural magic erupt, all of them gratuitous and described in such a way as to take readers out of our mundane experience of reality. Here’s one on page six:

One further example can help to make this point. In the first six pages of Christopher Paolini’s high-fantasy novel Eragon, multiple acts of fully described supernatural magic erupt, all of them gratuitous and described in such a way as to take readers out of our mundane experience of reality. Here’s one on page six:

Desperate, the Shade barked ‘Garjzla!’ A ball of red flame sprang from his hand and flew toward the elf, fast as an arrow. But he was too late. A flash of emerald light briefly illuminated the forest and the stone vanished. Then the red fire smote her and she collapsed. The Shade howled in rage and stalked forward [… . ] He shot nine bolts of energy from his palm—which killed the Urgals instantly—then ripped his sword free and strode to the elf. (Paolini 6)

Obviously, it is taken for granted that readers ought to recognize “Shades,” overt acts of powerful “magic” in emerald lights and red flames, and magical creatures with special names—“Urgals,” elves, etc. These descriptions serve to disrupt and distract the reader, destroying the narrative flow and the focus on the characters, and putting the focus instead on world-building and scenery: such descriptions lead away from storytelling into the realm of the fabulist. This is not a direction that leads to readerly enchantment, but instead becomes a kind of oddly interesting art-form that is focused on its own existence, not writing a story that connects on an emotional level with the reader.

Magic or the supernatural itself should rarely—if ever—be spelled out, in terms of its function or its full effect. The unearthly should partake of the “standard” world we know in a way that allows it to slide into consciousness in a “mysterious” or undercover manner that does not distract the reader from the narrative flow. Yet it is possible to create magic in an implicit way, and allow a story to take shape without such overt hints and explicit statements.

In contrast to Eragon’s great acts of “Magic,” that are named with powerful capitalized “Words” and acts that create flames and light, Susanne Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell uses this technique of withholding to combine magic and history in a believable way. Strange & Norrell is in many regards a historical novel reminiscent of classic works by the Brontë sisters, Jane Austen, and George Eliot. It is a Victorian story of mannered English people of the upper class, set in the 1800s, and the chief concerns of this novel are the lives and marriages of young women and their suitors. Since Strange & Norrell was written in the modern era (published in 2004), the story also enters into the lives and habits of the servants, examining and explaining in emotional terms their abilities and hopes to exceed (or live down to) the expectations given to them as a “lower class” of Victorian society. The story also includes King George, Lord Byron, and Lord Wellington as (minor) characters, and scenes set on the battlefields of the Napoleonic wars. Despite these martial scenes, the real crux of the story is perhaps the story of two marriages and how two couples found a way to live happily ever after. Yet it may also be the story of a former slave, now a servant, who finds his strength and his own voice, despite his social class. In point of fact, there are many complex character arcs in the novel: it may be read in many dimensions as a great work of historical and cultural fiction.

In contrast to Eragon’s great acts of “Magic,” that are named with powerful capitalized “Words” and acts that create flames and light, Susanne Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell uses this technique of withholding to combine magic and history in a believable way. Strange & Norrell is in many regards a historical novel reminiscent of classic works by the Brontë sisters, Jane Austen, and George Eliot. It is a Victorian story of mannered English people of the upper class, set in the 1800s, and the chief concerns of this novel are the lives and marriages of young women and their suitors. Since Strange & Norrell was written in the modern era (published in 2004), the story also enters into the lives and habits of the servants, examining and explaining in emotional terms their abilities and hopes to exceed (or live down to) the expectations given to them as a “lower class” of Victorian society. The story also includes King George, Lord Byron, and Lord Wellington as (minor) characters, and scenes set on the battlefields of the Napoleonic wars. Despite these martial scenes, the real crux of the story is perhaps the story of two marriages and how two couples found a way to live happily ever after. Yet it may also be the story of a former slave, now a servant, who finds his strength and his own voice, despite his social class. In point of fact, there are many complex character arcs in the novel: it may be read in many dimensions as a great work of historical and cultural fiction.

However, along with all of these social and cultural dimensions at play, all the critics agree that Strange & Norrell is fundamentally a story of magic and of the supernatural. For the occupations of Strange & Norrell are that of rival magicians: both of them are struggling to revive a forgotten magic first instituted by a mythical English magician known as the “Raven King.” As a story of the supernatural that operates on all of these multivalent levels, Strange & Norrell is powerful because of the use of the techniques outlined in the preceding pages, but in particular the idea of “withholding.”

The most pivotal magical act in the book begins in this pedestrian manner: “Mr. Norrell rose wearily from his seat and took up a book….Then he began to recite a spell” (Clarke 84). Note that this is the first time a spell is ever said in the novel, even though as readers we are nearly 100 pages into the narrative. Furthermore, the functions and actions and words and specific incantation are never stated. In fact, everything is elided in this “spell-casting” moment—this is no Harry Potter sorcery that can be neatly charted or analyzed by the reader. The moment itself is off-stage and withheld.

The spell immediately has an effect, which does not take place in a magical, otherworldly set of ideas or with bright lights and loud sounds. Instead, a few carefully described realistic events occur. These are described in sensory terms: “It took effect almost immediately because suddenly there was something green where nothing green had been before and a fresh, sweet smell as of woods and fields wafted through the room” (Clarke 84).  Any “louder” magical or emotional side effects of the spell are left aside in favor of smells, colors, and—notably—the sudden presence of a person:

Any “louder” magical or emotional side effects of the spell are left aside in favor of smells, colors, and—notably—the sudden presence of a person:

Someone was now standing in the middle of the room: a tall, handsome person with pale, perfect skin and an immense amount of hair, as pale and shining as thistle-down. His cold, blue eyes glittered…. he was dressed exactly like any other gentleman, except that his coat was of the brightest green imaginable—the colour of leaves in early summer. (Clarke 85)

The descriptions are grounded in the reality known by the main characters. Instead of inserting language that is not organic to the scene—“Shade” and ‘Garjzla” and “nine bolts of energy”—the new character instead is presented in language suitable to the Victorian observer who sees him. “He was dressed like any other gentleman,” states our observer, and therefore all other unearthly elements are stripped away from the description. We know nothing more about this “fairy”—in fact, we don’t even know he is a fairy at all. There is a very subtle hint of something super-real (or supernatural) in the very bright coat he wears, and the reference to the natural seasons, but even this is muted and simply a strange detail.

As an addendum to my findings, I’d like to re-emphasize character. If the characters are utterly believable, and the “magic” is utterly believable to the characters themselves, it makes it easier for the reader to believe as well. Writing a fantastic scene should be an outgrowth of a character’s thought process and character development up until that point in the novel, rather than a deus ex machina that just appears or intrudes into the narrative. If the details of the “fantastic” are withheld until the very end, the focus remains on the characters, their development, and their experience of the fantastic. In the preceding paragraph, the experience of information being withheld is further heightened by the fact that the character’s behavior both mirrors the expectations of the magician who called him, and also confused our main character. The magic is not straightforward at all:

The gentleman with thistle-down hair suddenly became very excited. He spread wide his hands in a gesture of surprized delight and began to speak Latin very rapidly. Mr. Norrell, who was more accustomed to seeing Latin written down or printed in books, found that he could not follow the language when it was spoken so fast… (archaic spelling in original: Clarke 85)

In this scene, the author takes a moment to ground us in the reality of Mr. Norrell—who thinks he is much more educated than he really is, and prides himself on learning, yet finds that learning is insufficient when presented with a living embodiment of someone who actually speaks Latin. This entire sentence regarding languages is a rhetorical flourish—about rhetoric—that conceals knowledge about a critical plot point here. The magic is concealed under a discussion of language.

For the personage who is suddenly in the room has been called forth for one reason, and one reason alone. That reason is the death of a new bride named Miss Wintertowne. In fact, this Miss Wintertowne is merely a corpse on the bed when the gentleman with thistle-down hair appears. In this scene, apparently a spell is cast to resurrect her. Yet moments after his strange appearance, Miss Wintertowne walks down the stairs and enters the downstairs parlour, to all intents and purposes alive and well. The actual moment of resurrection is not seen; neither is the magic performed to bring about that resurrection observed by the reader in any regard. Again, all of this “critical” information happens off-stage. By concealing these acts, the mystery and the energy of the supernatural is entirely preserved. However, magic in this novel has a palpable cost, and in the remaining 500 pages of the book, readers are slowly brought to realize that terrible cost. An early sign of that cost is brought to the reader’s attention right after the newly resurrected bride walks downstairs and takes her seat in the drawing room:

Miss Wintertowne… appeared quite calm and collected, like a young lady who had spent a quiet, uneventful evening at home. She was sitting in a chair in the same elegant gown that she had been wearing when [the others] had seen her last.

Miss Wintertowne… appeared quite calm and collected, like a young lady who had spent a quiet, uneventful evening at home. She was sitting in a chair in the same elegant gown that she had been wearing when [the others] had seen her last.

….

She did not appear in any way alarmed by what she saw, but she did look surprized; she raised the hand so that her mother could see it.

The little finger of her left hand was gone. (Clarke 91).

The finger is gone, yet we as readers never see the decision to remove the finger, and never see the act of removing the finger. We see nothing except a bargaining exchange between the strangely bureaucratic magician and the odd and unsettlingly talkative man with the strange hair. A page later, the corpse is alive, the finger is removed, the sorcery is seemingly over and done with. The fact that all of the details were withheld from readers heightens the mystery, the suspense, and the very magic of the acts themselves. In fact, because we don’t know precisely what happened, the magic seeps p erversely into the subsequent chapters as the book casts its slow and insidious spell over our reading.

erversely into the subsequent chapters as the book casts its slow and insidious spell over our reading.

The modern novelist Susanne Clarke, who writes in the mode of Jane Austen or the Brontë sisters, makes astonishingly careful choices in Jonathon Strange & Mr. Norrell in order to withhold as much information as possible from readers. By so doing, she creates a world that is entrancing and mysterious, yet deeply grounded in our experience of reality. A final technique that accentuates this withholding is a focus on implicit acts, not explicit statements.

READ the NEXT SECTION… in which I discuss Dracula, Tolkien and Clive Barker >>

————————————-

FOOTNOTE:

Rick Barot of Pacific Lutheran University made the interesting observation, during his read of an early draft of this essay, that this moment can be read a slant rhyme to the “birth” scene from Beloved, previously cited. (February 2014)

The Sorcery of Withholding – (Part 4 – How to Write Fantasy Fiction) was originally published on NedNote

“The daylight ebbs into the snow. Above us the swallows...

“The daylight ebbs into the snow. Above us the swallows rustle and nest. After the sun goes, there is nothing left here in this dark room but faces ruddy in the light of the flames. As the smoke comes out of the chimney of this little fallen house, I can again see Nell upon the little forest way beside her croft, the stones patterned with petals and cedar boughs, scented with the lavender and mint she planted with her own hands.”

– from the novel Sinful Folk

June 27, 2015

Grounding Magic in Reality - (Part 3 - How to Write Fantasy Fiction)

One of the keys to multivalent use of magic in a novel is the author’s refusal to characterize the supernatural with language that removes the reader from their reality: once you begin fitting magic into bureaucratic boxes of technical terminology, the narrative founders. Providing a spell book of rules about your world and a precise description of how incantations or magic works in your world is a sure way to focus the reader on acts of specific import, rather than turning the reader’s attention to character growth and motivation.

To add to this point regarding grounding the supernatural in reality, it’s also important to consider that magical acts must have a real-world cost to the characters. Alternative reality master writer Terry Pratchett, creator of the Discworld science-fiction series, makes the following observation regarding how to write about the supernatural:

If you use magic in fiction, the first thing you have to do is put barriers up. There must be limits to magic. If you can snap your fingers and make anything happen, where’s the fun in that?…The story really starts when you put limits on magic. Where fantasy gets a bad name is when anything can happen because a wizard snaps his fingers. Magic has to come with a cost, probably a much bigger cost than when things are done by what is usually called “the hard way”.

Characters cannot be invulnerable, all-powerful beings like Superman, or else it will be impossible for readers to identify with them or to find a way into the story itself. The supernatural can never be a “get out of jail free” card. Grounding magic in reality means that the powerful characters that we’ve used as our focus must actually suffer and find themselves challenged by the effects of the supernatural. One interesting example of the use of the supernatural in this manner can be seen in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved.

In Morrison’s story, the dead ghost of a child re-emerges into the lives of the main characters as a grown fully fleshed woman who has “willed” her way back into existence. At first, they do not know who she is, or what she represents in their lives. Morrison mirrors the characters’ lack of context for “Beloved,” the name of the daughter, by providing the initial introduction of Beloved as a character through poetic language that paints the situation as strange and imaginatively unreal. When she comes into the world in a supernatural manner, the cost is evident in her every action and in the descriptions of her activity:

A fully dressed woman walked out of the water. She barely gained the dry bank of the stream before she sat down and leaned against a mulberry tree. All day and all night she sat there, her head resting on the trunk in a position abandoned enough to crack the brim in her straw hat. Everything hurt but her lungs most of all. Sopping wet and breathing shallow she spent those hours trying to negotiate the weight of her eyeballs…. She had new skin, lineless and smooth, including the knuckles of her hands…. four times the woman drank from the speckled tin cup as though she had crossed a desert. (Morrison 50)

The critical elements here that provide supernatural indications that this “woman” is not of our world are coupled with the “cost” to her in terms of physical expression: her lungs hurt, her eyeballs have an unusual weight, and she has new skin. Finally, she has just “crossed a desert.” All of these narrative choices communicate to the reader that this woman is experiencing reality in a different way than the other characters and that her arrival here has a palpable cost to her physical experience. Of course, after you’ve read the book once, you recognize the metaphors of birthing and of new life in the world. However, at first read, these hints give her suffering in our reality a radically different angle, an unusual and poetic perspective. The hints reverberate and accumulate over time until the weight of what they might mean is inescapable.

As Morrison demonstrates, fantastical occurrences are more powerful if they are described with very literal grounded language at first and then hinted at and illuminated by metaphor until the possibility of it, and then the reality of it, becomes something heavy and inescapable in the reader’s mind—an overwhelming radical change that is referenced only glancingly by the other characters, but gradually insists on its own reality, much as the character of Beloved gradually insists on her reality in the lives of the characters in Morrison’s work. Metaphor and oblique references are critical tools to invoke an alternate story, or to hint at a story that can’t be told overtly.

It is also necessary to show how other characters are gradually informed of Beloved’s secret reality. Withholding the actual story from readers, and allowing it to come out gradually as a narrator or protagonist tells it to other people, is a technique worth exploring. Morrison does this adroitly. For example, it is absolutely lovely to see how she has her characters interact with Beloved. They field seemingly innocuous questions and discussion, and then Morrison allows the realization of the import of those questions to land later, at the end of the discussion, so that the true meaning of that conversation reverberates backwards through the story.

Here is one instance of this technique: “Now she noticed something more. The questions Beloved asked: ‘Where are your diamonds?’ ‘Your woman she never fix up your hair?’ And most perplexing: Tell me your earrings. How did she know?” (Morrison 63). Beloved herself has knowledge ungained from the other characters. This fact is clear. But the cold realization of something unnatural only hits the rest of the characters after the reader has already realized something is strange about this woman’s knowledge.

Here is one instance of this technique: “Now she noticed something more. The questions Beloved asked: ‘Where are your diamonds?’ ‘Your woman she never fix up your hair?’ And most perplexing: Tell me your earrings. How did she know?” (Morrison 63). Beloved herself has knowledge ungained from the other characters. This fact is clear. But the cold realization of something unnatural only hits the rest of the characters after the reader has already realized something is strange about this woman’s knowledge.

Finally, Morrison brings the “alternate” story (or the backstory) into her characters’ lives through visceral experiences that are inserted into a present narrative. Suffering from her supernatural nature is a continuing theme in the story: magic has a cost. Morrison slides the supernatural elements gradually into the main narrative by taking the hints further, until their import is inescapable. Here is a later scene that shows “Beloved” demonstrating her story—and her ghostly reality—to the other characters:

Beloved, inserting a thumb in her mouth along with the forefinger, pulled out a back tooth. There was hardly any blood…. Beloved looked at the tooth and thought, This is it. Next would be her arm, her hand, a toe. Pieces of her would drop maybe one at a time, maybe all at once. Or on one of those mornings…she would fly apart. It is difficult keeping her head on her neck, her legs attached to her hips when she is by herself. (Morrison 133)

Again, in this scene, Morrison does not make the backstory of Beloved into something unreal or ghostly, but grounds her experiences in realistically described moments that the other characters can actually sense and feel and see. Her character’s tooth removal is described only with sensory input, making it feel ultra-realistic. She has laid necessary groundwork here for believability; therefore, when her character later ponders her own unreality, and the difficulty of living as a “ghost” in the human world, the reader can suspend disbelief and travel with her narrative, because the previous moments were firmly grounded. Instead of being caught in abstractions, the reader starts from an anchor point that is firmly grounded in the everyday world. What Morrison does so amazingly well is to make the supernatural suffering a present reality to the characters, and thus, to the readers.

The realistically described experiences of Beloved thus bring the realization of the backstory (or alternate story) home to readers with a powerful punch. Much later in the book, after all of these hints and experiences have slowly collected like drops wearing down the disbelief of her other characters, Morrison finally brings a waterfall of realization. This is the moment that Morrison brings out the main pivotal moment in the backstory. She adroitly weaves together remembered backstory and present descriptions in order to bring the reader into the narrative.

Here is how Morrison brings the truth home. First, the “sweet conviction” in Beloved’s eyes causes doubt: her eyes seem to have the power to“almost [make] him wonder if it had happened at all, eighteen years ago, that while he and Baby Suggs were looking the wrong way, a pretty little slavegirl had recognized a hat, and split to the woodshed to kill her children” (Morrison 158). The building momentum of these lines leading to the final powerful act of “killing her children” feels believable to readers because it is so grounded in the present reality of Beloved’s physical presence and the details of his memory. Because of her consistent buildup of this story, the description lands with a satisfying wallop of pain. In Morrison’s techniques of metaphorical description, backstory hints, and visceral experience of “magic,” here are excellent tools that can be used by any writer who is describing the supernatural.

In his espionage novel Declare, Tim Powers also uses similar techniques to describe the supernatural. The novel Declare is a masterly combination of cold-war spy drama and fantastic magic that balances on a tight-rope between deeply researched historical verisimilitude and supernatural activity. In this work, Powers consistently demonstrates how a writer can effectively lift “magic” off the page and insert it into a character’s felt existence. Here are the words Powers uses to show how the magic feels to his characters in one pivotal scene:

In his espionage novel Declare, Tim Powers also uses similar techniques to describe the supernatural. The novel Declare is a masterly combination of cold-war spy drama and fantastic magic that balances on a tight-rope between deeply researched historical verisimilitude and supernatural activity. In this work, Powers consistently demonstrates how a writer can effectively lift “magic” off the page and insert it into a character’s felt existence. Here are the words Powers uses to show how the magic feels to his characters in one pivotal scene:

Breathing in whimpers through clenched teeth, Hale ran back to the room’s door and braced himself against that wall; then he pushed away from it hard enough to crack the plaster… and then he was flying through the cold air, one hand clawed out in front of him. His other hand clutched the iron buckle of his belt—and the air was driven out of his lungs as he folded over the narrow belt, which seemed to be following the trajectory of his jump, independent of gravity…. His pulse was roaring in his ears so that he could not tell if there was any commotion yet on the street side. (Powers 140-141)

In this passage, Powers has taken an idea that could have been spelled out with a great deal of magical terminology, and instead of spelling out the specific functions of the physics of the “magic” or the “supernatural” effects at play, he has instead merely told us the effect of these things on his main character. Again, magic has a visceral cost to the characters. Powers transmutes a powerful supernatural event into suffering, pain, “clawing,” “pulse roaring” reality experienced by his characters. This technique—employed by bothMorrison and by Powers—is used in the service of creating a multivalent story, rather than simply a plot with characters as cardboard chess pieces.

READ MORE IN PART 4: The Sorcery of Withholding (Writing Fantasy Fiction)

FOOTNOTE ON TERRY PRATCHETT

Rae, Isabel. “Writing Frenzies” site, accessed on September 19, 2014. http://writingfrenzies.tumblr.com/us.

Grounding Magic in Reality – (Part 3 – How to Write Fantasy Fiction) was originally published on NedNote

BOOK QUOTE:“Sound carries far here in the trees. Snow slides off...

BOOK QUOTE:

“Sound carries far here in the trees. Snow slides off a heavy oak as some creature shuffles through the woods, and ancient branches snap. Out of the corner of one eye, I see the flash of colored feathers. It is a yellowhammer, black eyes flickering in a hedgerow, tiny breast plumped out in golden livery, streaked with colors rich and brown. It was calling in its winter song:

A little bit of bread and no cheese—

A little bit of bread and no cheese—

Moments later, the bracken flutters and the slight shadow of the bird darts into the woods. Deep in the forest now, I hear a low voice that wends back and forth, whispering in secret.”

— from the novel Sinful Folk

June 26, 2015

Character Matters in Fantasy -- (Part 2 - How to Write Fantasy Fiction)

It’s not easy writing fiction that contains fantasy or supernatural elements. One out of two tries at such work might even fail. The Pulitzer-Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon succeeded admirably in his novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. In this saga of Jewish immigration and comic-book capers, Chabon’s narrative became compelling and multivalent to readers because of his central focus on the characters of Kavalier and Clay, and his careful treatment of the magical threads in his novel (those of sorcery and golems), that he wove seamlessly into the central narrative fabric, which focused on his characters’ growth over the 600 pages of the novel. Chabon also avoided using familiar tropes of immigration, seizing instead on magical realism in order to “talk about things that cannot be explained.”

Yet in a book that appeared only two years after the success of Kavalier & Clay, Chabon demonstrably failed at creating a fantastical story that enthralled readers and spoke to our shared humanity. In 2002, Chabon published a novel explicitly billed as “young adult fantasy novel” entitled Summerland. In interviews, Chabon explicitly stated that he wished to produce a novel that was in the style of the classic children’s fantasy by Susan Cooper, The Dark is Rising. However, the distinction between Summerland and Dark is Rising is stark. Cooper’s work is about a boy’s maturation and understanding of his own powers and place in the world—and it also happens to contain some magical elements, allegorizing his coming-of-age in a mythological battle. Summerland, in contrast, seems to be explicitly about magic and alternate realms—and happens to mention one child’s struggles in passing. In Chabon’s work, the characters themselves are subliminated to a series of strange and fantastic events; as The New Times said, the novel was “bewilderingly busy.” Summerland, despite its ambition, showed that Chabon was only mocking the possibilities of Dark is Rising, without taking the time to go back and understand the true multivalent narrative of The Dark is Rising. In Cooper’s more powerful work, the structure and the subversion of genre conventions themselves reinforced and articulated the character’s adolescent path towards maturation.

Yet critics were unanimous that the failings of Summerland were due, almost entirely, to the “genre” in which Chabon was working in this novel. This is often assumed to be because the insertion of fantastical creatures and events can detract from human characterization. The critical rationale seems to be that some fiction in this genre has historically provided less insight into character and less meaningful interactions between the characters. Furthermore, some critics asserted that the YA fantasy form was “tired” in its form and function, and unworthy of Chabon’s gifts.

However, if we scrutinize a novel that is of exactly the same “genre” as Summerland, we can cross-examine that assumption. It may be possible to build deep complex characters on the same fantastical base, and fully flesh them out so readers care about their fates, and will travel into a fantastical domain to see their characters grow and change over time. This is the task of multivalent fantasy literature. And young adult fantasy literature doesn’t have to focus just on one young (white) male and his need for meaning and fulfillment: it doesn’t even have to focus on a coming-of-age story at all, despite the use of such a model in both Dark is Rising and Summerland. One example of a successful book that does things differently—with remarkable success—is Barbara Hambly’s historical fantasy Bride of the Rat God.

Bride of the Rat God is indeed a young adult fantasy novel—the title by itself tells you much about the book, and indeed the book lives up the title’s billing: it is very satisfying as a genre historical fantasy novel. The story takes place in 1920s Hollywood, which would seem an unusual locale for magical events, but Hambly pulls off a solid plot arc. Good fights mysterious ancient evil, complications ensue, and in the end, good defeats evil. Given these genre trappings, it was therefore a pleasant surprise to find deep, complex characters at play here, beginning with Norah Blackstone, the protagonist.

Bride of the Rat God is indeed a young adult fantasy novel—the title by itself tells you much about the book, and indeed the book lives up the title’s billing: it is very satisfying as a genre historical fantasy novel. The story takes place in 1920s Hollywood, which would seem an unusual locale for magical events, but Hambly pulls off a solid plot arc. Good fights mysterious ancient evil, complications ensue, and in the end, good defeats evil. Given these genre trappings, it was therefore a pleasant surprise to find deep, complex characters at play here, beginning with Norah Blackstone, the protagonist.

First, there’s the backstory: Norah is the Jewish, middle-aged, widowed sister-in-law of a silent movie star, and her relationship with her dead husband plays a part in her self-understanding. Her slow healing from that loss is the central motion of the story, from her perspective, even while sorcery is erupting all around her. In point of fact, Norah’s backstory and personal growth are so interesting, that I would love to read a whole series of books about her. As a fully embodied adult human being with a long and complex backstory, Norah belies the focus of young adult fantasy on only young adolescent males. Furthermore, Norah is a person with her own motivations and desires: she demonstrates regularly that she is hardly perfect, and yet her foibles make her seem more fully embodied to a reader. Her behavior towards her selfish and indulgent sister-in-law, and her general disdain for Hollywood, all endear her to the reader. And finally, despite her failings, Norah’s motivations and actions seem to be consistent with her character, and consistent with what we expect of actual human beings in the real world.

One example of this consistency and complexity is an early scene when she leaves her sister-in-law in a scene of impending peril to search out her new boyfriend. She does so because she is afraid of losing him the same way she lost her husband. Because of the backstory and her own fearfulness, her motivations seem justified and realistic. Readers must believe in a character’s actions, and Hambly makes this truth come to life in Norah’s character and actions. The act of writing a plot-driven story that contains the “literary” attributes of well-thought-through characters and deeply articulated motivations is a high-wire act. Barbara Hambly, in Bride of the Rat God, succeeds admirably in this act, and by so doing enthralls her readers with a story that speaks on multiple levels.

So it is possible to write fully embodied characters who don’t fall into familiar and hackneyed tropes. This act is a standard act in many literary works, but sometimes even strong and fully fleshed characters are overwhelmed or superseded by the spectacle of magical or unearthly moments—in Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare himself falls into this trap. Therefore, if a writer is going to introduce fantasy or the supernatural, how does one do this in a way that doesn’t distract from character depth and emotional growth?

READ MORE IN PART 3: Grounding Magic in Reality (Writing Fantasy Fiction)

—————————-

FOOTNOTES

—————————-

The Amazing Website of Kavalier & Clay. http://www.sugarbombs.com/kavalier/?page_id=4 “Genre fiction became not just a favorite type of story for Chabon but a metaphor at times as well. In April 2005, Chabon told the Australian publication Stuff that with The Final Solution, he chose to go the mystery route as a metaphor, a way of “producing the sense of mystery with a capital ‘M’. This allows us to talk about things that cannot be explained.” Accessed November 22, 2014.

Mendieta, Gabrielle. “An Open Book” Interview with Michael Chabon. January 2, 2013 http://www.anopenbookblog.org/michael-chabon-la-deuxieme-partie/

Lipsyte, Robert (November 17, 2002). “Children’s Books: Field of Really Strange Dreams.” The New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

Lipsyte, ibid.

[v] Tolkien, of course, wrote a wonderful essay in which he attacked this very assumption. The essay is entitled “On Fairy Stories,” and he describes how the job of a pure fantasy writer is actually harder than a “straight” fiction writer. From his perspective, a fantasy novelist must not only create characters to move through a believable world, but must also craft the world complete in itself.

“Adult Writers Write for Children.” Raleigh News and Observer. November 2002. http://bit.ly/1E3xxhj.

Other readers have agreed with my assessment, rating Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream a “C” or a “D+” – stating that the play is “thin” and relies too much on the supernatural to make a fully compelling story. See Anthony Wirth, UC Berkeley. Site accessed November 29, 2014. https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~anthony/Shake.html.

Character Matters in Fantasy — (Part 2 – How to Write Fantasy Fiction) was originally published on NedNote

Introduction & Techniques in Fantasy -- (Part 1 - How to Write Fantasy Fiction)

Part 1—Introduction

Part 1—IntroductionStrange things happen in books. Supernatural things are often described that can’t happen in real life, and yet these “fantastical” experiences provide some of the most startling insights available in literature. Think of the resonance of Kafka’s cockroach-man: turning into a bug is nothing if not supernatural. And what of the eerie disembodied voice calling out near the end of Jane Eyre? Mary Shelley’s unusual resurrection story—Frankenstein—also continues to resonate in our literary culture today. Add to your reading Shakespeare, whose magic-infused Tempest and Midsummer Night’s Dream are some of the most powerful works of drama on the stage. And in mentioning Shakespeare, we cannot ignore Hamlet, no doubt the most revered of his works. Hamlet, of course, is a supernatural ghost story—a ghost whose opening appearance and subsequent pronouncements are taken seriously by the title character. Strange things happen, indeed.

Yet why are supernatural events in fiction so often the liminal opening for deep insights and great literature? And why do some supernatural events in a story seem to rise above the clichéd idea of a mere spine-tingling “ghost story”? Critics have often wondered at the very use of the supernatural in literature. Why is it necessary or useful? And when confronted with writers who are acknowledged by all parties as “great,” these same critics wonder how some writers manage to use the supernatural, yet supersede that source material and create sublime heights of literary expression?

In fact, I think this question, as expressed, is looking through the wrong end of the lens. I would suggest that Shakespeare, Kafka, Mary Shelley and the Brontë sisters used fantastic fiction—and the supernatural—because by doing so, they were creating a text that was able to operate on multiple frequencies, telling one story while they were also speaking on a different register. Writers who use the fantastic choose to use this form because such “fantastic” moments open up new possibilities and new routes for narrative that could go beyond the “straight” story. Supernatural events, as Shakespeare and Mary Shelley demonstrate, are an indirect way of getting to deep truths which if stated obliquely on the page would not seem very interesting or artistically insightful. But through the lens of fantasy, they can be seen from a different angle and can resonate in new and startling ways.

Fantastic literature thus carries in it deeply felt metaphors for human experience. Explicitly “magical” plots usually conceal a secondary narrative that touches on universal human concerns. This dual voice in fantastic literature I find intriguing, and in my own work I am trying to create the same type of multivalent literature. In learning from masters of various fantastic forms of literature, I have identified several techniques that use the fantastic to communicate a profound literary narrative. These techniques include a) character-driven narratives, b) realistic grounding in the world of the novel, c) the withholding of details about the supernatural and d) descriptions of magic that emphasize implication, not explicit description.

These techniques are often important to maintain the balance of a text that works on both levels, as both a fantastical story and an emotionally realistic narrative. To demonstrate these techniques at play, I’ve chosen examples from the works of Toni Morrison, Barbara Hambly, J.R.R. Tolkien, Tim Powers, and Susanne Clarke; I will also cite and describe counter-examples found in the work of other writers, and summarize my view of a multivalent literature of the fantastic by a detailed analysis of Cormac McCarthy’s masterwork of allegorical fiction The Road.

These techniques are often important to maintain the balance of a text that works on both levels, as both a fantastical story and an emotionally realistic narrative. To demonstrate these techniques at play, I’ve chosen examples from the works of Toni Morrison, Barbara Hambly, J.R.R. Tolkien, Tim Powers, and Susanne Clarke; I will also cite and describe counter-examples found in the work of other writers, and summarize my view of a multivalent literature of the fantastic by a detailed analysis of Cormac McCarthy’s masterwork of allegorical fiction The Road.

The goal of this essay is to illuminate the successful strategies used by writers who embrace these techniques to create powerfully multivalent narratives. Yet before we delve deep into the techniques in question, allow me first to clarify the terms of our discussion, and provide a scope around “fantastic literature” that is reasonable for the present endeavor.

Terms and Scope

What is the worth of calling one piece “fantastical literature” and another mere “literature”? What’s the difference? The obvious and proper approach to all literature should be to consider what it is doing for its readers, and what literary acts it is performing on the page, and in the minds of readers, rather than paying attention to what label the marketing department has slapped on the cover of the printed book. To cite two small examples, Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Margaret Atwood work under the guise of writing “literature,” yet the magical moments and emotions in their text become so strong, so overwhelming of the text, that they stretch out into a world that is not quite grounded in the constraints usually found in contemporary realist-oriented “literary fiction” such as the works of Raymond Carver, Edward P. Jones, or Alice Munro. The works of Atwood and Márquez use “magical” moments to make explicit points about the power of emotion, the motivations of characters, or the ideas behind the worlds they have created.

Given these literary experiences, I propose making no distinction between literature labeled by a publisher’s marketing department as “literary fiction,” “magical realism,” “fantasy,” “horror,” or “science fiction.” Of course, an approach that ignores “genre marketing labels” does require readers to stretch bookish boundaries a bit to allow “literary” novels such as Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to fit into the genre of “science-fiction.” If we insist on using labels for literature, this also means Gabriel García Márquez and Isabelle Allende may also fit into “fantasy” and most of Michael Chabon’s award-winning work may be called mystery or thriller or even “horror.” Other works, such as Mary Russell’s The Sparrow or Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, seem to begin at the other end of the spectrum, explicitly stating that they are “about” an otherworldly domain, yet really they contain deep commentary and insight into life-as-we-live-it, under the guise of being about nothing in our known world. But if we start by not looking at the label, but instead by asking what these books are doing to and for readers, then we can begin to dissect the techniques in order to see the deeper effects at play under the surface of the narratives.

Given these literary experiences, I propose making no distinction between literature labeled by a publisher’s marketing department as “literary fiction,” “magical realism,” “fantasy,” “horror,” or “science fiction.” Of course, an approach that ignores “genre marketing labels” does require readers to stretch bookish boundaries a bit to allow “literary” novels such as Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to fit into the genre of “science-fiction.” If we insist on using labels for literature, this also means Gabriel García Márquez and Isabelle Allende may also fit into “fantasy” and most of Michael Chabon’s award-winning work may be called mystery or thriller or even “horror.” Other works, such as Mary Russell’s The Sparrow or Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, seem to begin at the other end of the spectrum, explicitly stating that they are “about” an otherworldly domain, yet really they contain deep commentary and insight into life-as-we-live-it, under the guise of being about nothing in our known world. But if we start by not looking at the label, but instead by asking what these books are doing to and for readers, then we can begin to dissect the techniques in order to see the deeper effects at play under the surface of the narratives.

Once our only calculus is based on what stories are actually “doing” to readers, it is reasonable to see a difference between “straight” literature and “fantastic” literature. A story that makes a leap into matters that could not occur in our “real” life is creating an explicitly multivalent narrative, and can thus be characterized as “fantastic.” “Straight” literature—or rather, literature that pretends to its audience that it is not on its face fantastic—attempts to produce a transcribed after-the-fact simulacrum of time and call it “realistic.” These works are implicit in their attempt at multivalency. Fantastic literature, in contrast, is explicit in its multivalency.

It is also important to note that multivalency is not constrained to “classics” of fantasy literature such as Shelley’s Frankenstein. One obvious example is the work of horror/fantasy genre master Anne Rice. Her first breakthrough novel Interview with the Vampire functions as a powerful metaphor for the experience of homosexuality, societal rejection and coming-to-terms with one’s nature. It is also a disturbing and deep commentary on death and life-after-death. What’s interesting is that, except for the title, the term “vampire” is rarely stated—it is instead subverted, under the surface of the story of self-abnegation, self-rejection, longings that are seen as depraved lust.

The careful reader will at this point have additional questions about the description of a text as “multivalent.” Where does multivalency begin? And where are the boundaries of a text’s multivalent content? Aren’t all texts multivalent? I would argue that multivalent fiction ideally gives us several layers of incited meaning at the same time. The plot on the surface is merely one line of story—but that line of story must be convincing in itself, and cannot be subverted to a secondary reading. The secondary reading is a reading of the characters’ motivations and inner lives, and that secondary reading must be equally convincing. Perhaps there’s a plot to move us forward, but ideally there’s also a deeper meaning underneath. What’s interesting is that the most multivalent fantastical moments are grounded realistically—a technique that we can examine more closely by looking at books by Michael Chabon and Barbara Hambly.

MORE IN MY NEXT POST…. on Barbara Hambly and Michael Chabon…. > >

—————————–

FOOTNOTES

—————————–

[i] In American letters, there is a long history of literary critics denigrating so-called “genre” works of fiction. Arthur Krystal in The New Yorker on May 28, 2012 provides a recent example: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/05/28/easy-writers

In the context of this essay, it is important to note that the particular “genre” marketing label that appears on the books in question is not of interest. Instead, I am considering what literary acts the work performs in the minds of readers, rather than paying attention to the label a marketing department has slapped on the cover of the printed book.

Literatures that regularly perform this latter hat-trick are often classed as “fantasy” (Jo Walton, Tolkien, Mieville) or “horror” (King, Barker, Lovecraft, Poe) or even (sometimes) “speculative” or “science-fiction” (Atwood, Alastair Reynolds, Le Guin).

I am writing this essay as a candidate for a Master in Fine Arts in a program that is explicitly aimed at producing writers of “literary” fiction. Therefore, it seems important in the present context to name the questions under discussion explicitly. To name the elephant in the room, how does one defend a critical essay that is focused on analyzing the treatment of “magic” in literature often classed as “genre” fiction?

[v] The present essay is, of course, an obvious attempt to address the fact that the multivalent frequencies used by fantastic literatures are often not recognized by either scholarly reviewers or by general readers.

[vi] Unfortunately, after the early success of these two profoundly multivalent texts, Rice continued the series in a shallow style, mistaking plot for substance, and mistaking action for insight. Of course, the problem with fantasy literature is that once it is successful, many writers are harassed by their editors or agents to try to recapture the magic by adding endless sequels. The sequels, and the also-rans, and the pastiches that follow, all too often focus on plot at the expense of a double-voiced narrative. The reason that writers are harassed to write sequels is, of course, that it sells amazingly well. Terry Brooks, whose career has often seemed to be focused on Tolkien knockoffs, retired rich to Hawaii, and continues to add pages to his Shanara epic series from the beach.

[vii] Anne Rice’s second novel Vampire Lestat is often considered to be a lesser novel, because the story overtly announces itself and spends much energy describing the supernatural aspects of the world she has created. The larger-than-life persona of Lestat is foregrounded, and his identity as a vampire, but in this second book in the series, Rice is making an entirely different commentary than the first. This time, she is writing a story about the nature of fame, and how it corrupts, and how identity itself is malleable depending on perspective. So the very explicit nature of the text – and the larger than life supernatural acts of the main character – contain a commentary in themselves on the “fame” of vampirism and of characters like Lestat. The novel works on a different level. It’s telling that Tom Cruise was cast as Lestat, because he subverted his own fame in this role, mocking his own fame as a heterosexual masculine hero in the process.

Introduction & Techniques in Fantasy — (Part 1 – How to Write Fantasy Fiction) was originally published on NedNote