Stephen Gallup's Blog, page 7

November 19, 2012

November 13 interview with host Lillian Brummet

The interviewer’s focus in this discussion remained pretty close to the “lost, isolated and helpless” theme in her write-up. Listening through it afterwards, I wondered if perhaps she wanted more acknowledgment from me that such is the fate of people trying to raise disabled kids.

Readers of What About the Boy know that I don’t minimize the reality and effect of strong emotions. However, my view is that the value of anything said about this depends in large measure on finding a way not to feel lost, isolated, and helpless, and instead to feel empowered to bring about positive change – or at least to remain undefeated in spirit. It seems the answers I offered to her questions restated that point in various ways.

As I’ve written in other posts, everyone seems to encounter hardship, disappointment, injustice, etc. Some folks do have easier lives than others, but there’s no point or future in anyone arguing that they’ve been given a worse deal than someone else. When you take that path, you’re in danger of nurturing that sense of unfairness. I don’t think it’s constructive to direct your energies away from the neverending process of living victoriously.

Please click the above image to hear the audio. Click here to read the transcript. As always, comments are welcome.

October 28, 2012

Are you ready for healing?

Ridiculous question, right?

Everybody in need of healing is ready for it. At least it seems that way on the surface (Many years had to go by before I was able to add this sentence).

Throughout the campaign to restore my son to his birthright, the high points of which are dramatized in WATB, I felt utterly–almost violently–impatient with any suggestion that:

His healing ought not be the first order of business

Our efforts to bring about his healing could be misguided

Healing was perhaps not God’s will

The apparent odds against succeeding were almost not a consideration. I understood that important goals required effort, persistence, sacrifice, positive thinking–and all that was OK! I wanted to do all that, so we could eventually accomplish the thing our family so desperately needed.

I think now that, if we had achieved complete success, it might have affected me in a bad way. Evidence that I’d been right with regard to the above points could have made me insufferable. Inflexible. Incapable of ever learning again. Never mind the fact that any effect on me would not compare to whatever wellness might have meant to my son. I still cannot see how he is better off without having attained wellness. Growing up as a well kid would have been a good thing for him.

Anyway, without that evidence, I felt confused and humbled. The years that followed have involved a fair amount of soul-searching. I’ve tried to be open to words of wisdom from various sources, but most often the input meant nothing. About a year ago, something triggered a little epiphany, a new way of understanding a word of advice that had been offered near the end of WATB. Today, I heard something that built upon it.

If you have wrestled for a long time with an unresolved problem like this, and are prepared to listen to a message that might not reinforce your own most strongly held opinions, I invite you to click here. As mentioned above, for a long time I was unwilling to hear different ideas. That kind of stubbornness did my family no good.

I’d like to know what you think.

October 16, 2012

A conversation with my son

I thought, at first, we were there. He looked directly at me, a steady, relaxed gaze, which in itself would be a remarkable thing for him to be doing, and should have been a clue. Standing in the washed out glow of a streetlight, he leaned back against a yellow VW beetle with both hands thrust deep in his pockets and regarded me, smiling faintly. As usual, I could only guess at what he found amusing.

Then I understood that it was really I who was looking at him. I pulled my attention away for a moment, not wanting to run the show. It seems I was straddling my old 10-speed, resting sweaty forearms on the handlebars. I looked down and prodded the toe clip, idly spinning the pedal on its axis.

“I never taught you how to ride a bike,” I murmured sorrowfully. I looked up again to see him striding through the garage and into the house.

Now we were in the dining room, still standing, the table between us. It was my own dining room, a place in which we’d both been innumerable times, but not like this. On the other hand, I sensed something archetypal about this encounter, an elemental cross-generational thing, possibly even a scene we’d rehearsed before.

He said, “I think someone is dreaming about this, and maybe planning to tell the world about my inner life.” He winked.

I switched to my earnest voice. “The important thing would not be telling secrets, but rather our simply being able to do this, you know, really.”

He nodded. “We could do this. If the me who’s here met the you who’s there.”

Zany laughter bubbled inside me. “But the you who’s there is the one everybody knows. There’s not much difference between the me who’s here and the me who’s there. Is there? But nobody has seen the you who’s here.”

He opened a varnished wooden box on the table, put his hands inside, and concentrated on doing something behind the raised lid.

“Um, yeah,” he said absent-mindedly. “Maybe people need glasses.”

I said, “I hate to say this, but there’ve been other dreams when you were dead. We were grieving!” My words stumbled out. “I thought those dreams meant, you know, that it was all over, and there was no more hope of reaching you.”

He glanced up from whatever he was doing in the box. “Ever hear anyone say you take yourself too seriously?”

I could feel a line of sweat moving down my forehead. “God, I’m hot,” I muttered to myself. “What is wrong with me?”

“Why don’t you turn the pillow over?” he suggested.

“That does help. Say, I used to do that all the time when I was a little kid. It’s nice and cool. I’d forgotten that trick.”

He smirked. “I’m closer to being a kid than you are.”

“True. OK, you have any other words of wisdom for me?”

“Is there such a thing?”

“Well, look. I know for a fact that people say stupid things all the time. So it kind of stands to reason that there could be the opposite of stupid.”

“You should know that words like stupid rub me the wrong way.”

I mumbled an incoherent apology, something about the excessive latitude we allow some words. He wasn’t listening, so I said, “Son, has anyone ever said you were stupid?”

He looked up from the box and gazed into the distance with a noble, longsuffering expression, immobile as finely polished marble.

“I’m like a statue to you,” he observed finally.

“You’re no statue. You’re my boy.”

“People don’t have expectations of statues.”

“We see something made by man, we look within ourselves. If it resonates, then we admire it.”

He sighed. “What you have in your head, about me, is made by man.”

“But not you yourself.”

“Not me.”

“You’re not made by man.”

He snorted derisively, looking back inside the wooden box. “I’m sure you think man could’ve done a better job of it.”

“I don’t get it. Do you want people to have expectations of you, or not? Have you never had expectations of yourself?”

He rolled his eyes. “We go way back. I remember, same as you, what that was like. Thank you for trying.” He inclined his head formally. “Some of it was good. You should know by now that’s ancient history.”

“Because the you who’s there–”

“The me who’s there doesn’t give a shit any more. I learned you don’t pin everything on–.” He lifted a hand and made vague circular motions above his head.

“Now that you mention it, that’s something I’ve always wanted to ask you. What do you give a shit about? I’d like to know. Because all I ever wanted to do was help you succeed.”

“Boo hoo. There you go again. And shame on me. A boy gets to my age, he’s supposed to start helping the old man, right?”

“I’m not asking for that,” I said, a sob welling up within my throat.

He smiled brightly. “It’s almost breakfast time. Hungry yet?”

“I’d rather talk while we can. We never talk.”

“One of us never talks. The other one talks too damn much.”

“Hey, hey, a little respect wouldn’t be amiss.”

He grinned even more radiantly and leaned across the table to clap a surprisingly large and strong hand on my shoulder. “Come on, I think you can take a joke.”

“You want me to shut up?”

“Know what? I want you to eat. Here.” He stepped away from the box, holding a black tray arranged with crisp Japanese precision–a large brown bowl flanked by a pair of long, lacquered chopsticks. He moved around the table and set it before me.

“Well that’s lovely.” I slipped into a chair and lifted the lid from the bowl, discovering I was suddenly desperate for refreshment. “Is it–is this yogurt?” He wasn’t there. I regarded the chopsticks with concern.

I heard his voice, behind me now. I wanted to see him again but couldn’t muster the energy to turn over. “You don’t have the right tools. That’s been my problem all along. I don’t have a spoon to give you. You don’t have what I need, either. We make do with what we’ve got. Or else let it go. That’s OK too.”

“But people can find tools. Make tools. Invent something new.”

His voice now came from such a distance I scarcely heard. “Good luck with that.”

Morning had arrived. The day was breaking over Mission Trails Summit, where he and I had never once gone biking together. Breaking over the neighborhood streets, where backpack-laden kids would soon be heading for school, and where short school buses would be plucking up those who followed my son’s footsteps. It’s morning there. And there is no here.

September 28, 2012

Caring

If there has been a theme for this month, for me it has been caring.

Caring as in feeling anxiety and frustration when, for example, through a series of unfortunate events my younger son Braxton put a gash in his chin, requiring seven stitches—and then managed to reopen the wound the day after the sutures were removed.

Caring as in dreading the implications of an upcoming conference scheduled to address the fact that my older son Joseph no longer fits in at the center where he has spent the last few years. (I’ll say more about that later, when I know more. But right now the situation does not sound good.)

It’s human nature to feel some variety of care, about one thing or another, on an ongoing basis. I care just as much about my daughter Susannah as I do about her brothers, but these days (as far as I know) her life proceeds with little turmoil, or at least she’s able to handle issues as they arise with minimal interference from her mom and me. She brings me an algebra problem from her homework or she asks for a few bucks, and then all is well. These issues are neither urgent nor dire, and—also much appreciated—are easily solved. So far. I know not to take that blessing for granted.

In my life, the most acute examples of caring have come in connection with my role as a parent. Beyond that, life presents an endless menu of other potential concerns. Some of those opportunities merit more focus than others, but living means attending to them all in some fashion. Likewise, caring about an issue can lead to situations in which I can’t avoid noting a lack of care given it by other people.

We could all provide examples. Here’s one. An autism research center in Canada contacts me from time to time for input to support the various studies it runs. Most recently, they sent a questionnaire to be filled out by the developmental professional who works with Joseph. It came with a postage-paid return envelope, and consisted of a few sheets of questions with multiple-choice answers. The therapist accepted the package and said she would do it, for me (as if I were the beneficiary)—and then dropped the ball.

The study itself is a small matter from our point of view, in that the outcome is unlikely to affect Joseph’s life, but it’s disturbing to see a certain consistency in the professional’s failure to take that request seriously. Going back quite a few years, her colleagues have had a similar response to every request I ever brought them. (I allude to that here.)

The month’s theme probably got its start a few weeks ago when I reread a novel by Daniel Quinn. In a way, that story dramatizes a variant of an issue that’s at the heart of What About the Boy?: Life can present you with a problem that calls for a serious response. You can care very much about providing that response, even to the extent that providing it becomes bound up with your concept of who you are. If you can be satisfied with the extent of your own response (as I am at the moment with my responses to Susannah), all well and good. Disappointment begins if you think it would be appropriate for someone else to take a similar interest.

September 18, 2012

A Community of Writers and Readers

“And are you a writer?”

This polite question was asked of my wife years ago, when I introduced her to my professor at a party. That professor’s byline frequently appeared under stories in The New Yorker, her first (of many) novels was coming out, and since the party was for her creative writing class, practically everyone around us aspired to similar success.

As it turns out, Judy did not write. But she had a ready comeback.

“No,” she said. “I’m a reader.”

Where indeed would writers be without readers?

The point is often made that a writer must also read—preferably in many genres—in order to stay up to speed with what others are doing. To some extent, the way a story is put together or the way language is used in it is a response to that context—not a final answer, of course, but one more statement in an ongoing conversation. That’s why, in my own first encounter with the above professor, she’d asked what authors I was reading. I mentioned Gogol and Tolstoy, but she shook her head impatiently. “Are you familiar with any current authors?” she asked.

“Well,” I said slowly, “I’m also partway into something called The Death of the Novel.” I named that one reluctantly, because it was very weird. I didn’t know how she’d react.

Actually, she liked that answer much better. “Ronald Sukenick is about as contemporary as you could get!” she said happily. (This was in the mid-70s. Thus far I wouldn’t say that Sukenick’s work has withstood the test of time as well as those others. I could go further and say his kind of experimentation was not the sort of thing newbie writers such as myself needed to be emulating, right out of the gate. Nevertheless, writers have to venture beyond the classics, and indeed beyond whatever material they find most comfortable. The more we stretch, the more we learn.)

A book like Sukenick’s is probably intended specifically for other writers. Most books are not. A reader of a book like What About the Boy? may pick it up as casually as any other small purchase, and will most certainly put it down again if it fails to connect. Such readers represent the true test of a book’s worth. Imagine the gratification I experience when a reader feels moved to contact me out of the blue—as when a woman in Atlanta wrote to say that WATB had spoken to her, even though she had no children of her own. Likewise, I was thrilled to receive a phone call one evening from the daughter of a deceased author, who’d written a memoir somewhat like mine many years ago.

On the other hand, thus far, few contemporary writers known to me have read WATB. (At least, they’ve had little to say about it.) Perhaps they think its focus on disability removes it from the body of works that constitute contemporary literature. Or perhaps the notion that it belongs is my own conceit. Determinations like that occur on a plane beyond my understanding.

In my view, writers and readers alike exist in a loosely connected community. We communicate with what we say and don’t say. In writing my memoir, in reviewing the works of others, in responding to occasional requests for private critiques, and in taking questions on call-in radio shows, I hope to contribute value to this community.

As always, feedback on that is very welcome.

September 7, 2012

My review of Solla Sollew

I read this charmer for the very first time last night when putting my little guy (Joseph’s (much) younger brother) to bed. What a pleasant surprise!

Up till now, if asked to pick a favorite Seuss title, I’d have gone for The King’s Stilts, mainly because of memories of having it read to me as a child. (We still have an early edition of that classic, which might be worth some money if only my sister and I hadn’t marked up the pages.) Dr. Seuss’s better-known creations are great fun, too. Last spring my 12-year-old did a school report on him, from which I learned such interesting trivia as the origin of his first title, And to Think That I Saw it on Mulberry Street: It was suggested by the rhythmic sound of the engine on a ship he was riding home from Europe.

Anyway, with the continuing presence of so many examples in our house, I’d thought I was reasonably up to speed on the Seuss oeuvre. Discovering surprising new material at this late date has a way of making me stop to reconsider. Offhand, I can think of one other that has such a clear moral lesson–Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose. This is not to say that lessons necessarily make a story better. It’s OK to enjoy something for its own sake, and there’s even a Seuss quote to that effect. But right now I find myself receptive to a little more.

No doubt the excitement has something to do with the story’s relevance to a theme I gnaw at with many of my blog posts (this one, for example), i.e., trouble and the disappointing results of our efforts to overcome it. Of course, I also immediately recognized the Wubble chap, who confidently promises to deliver our suffering main character to a utopia but instead ends up multiplying the hardships. That same guy is scheduled to give a speech tonight on prime-time TV. The lure of such characters resembles that of the lottery, and I think all of us feel it at least a little from time to time.

Hence the value of a story like this for folks of all ages.

My son has a habit of demanding that I read the same books again and again every night, so that, from my point of view, we’ve completely worn out some first-rate stories (The Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, The Velveteen Rabbit, etc.). Right now I hope he’s up for more of Solla Sollew.

(I originally posted this review on Goodreads.)

August 30, 2012

The disability of deafness: How a cholesteatoma changed my life

Being deaf in one ear definitely has its advantages. When I was a kid, my mom would yell up the stairs to ask a favor or to assign a chore, which I was conveniently “unable” to hear due to my deafness. If I’m ever with someone who talks too much, I can simply sit or walk on their right side and face my left ear toward them. I can lie on my right side with my ear against the pillow and effectively shut out most sounds. Losing hearing in one ear can be convenient.

But while I can joke about being deaf in one ear and talk about the perks that accompany it, the story of how I became deaf is not so lighthearted. When I was six I took the standard 1st grade hearing test. You know, the one where you put the headphones on and lift your hand when you hear the beep? I failed that test and was told to see a doctor. Upon visiting the doctor, the second he looked in my left ear all color drained from his face. He looked at my mother, explained that I had a cholesteatoma, and that I would need emergency surgery within the week.

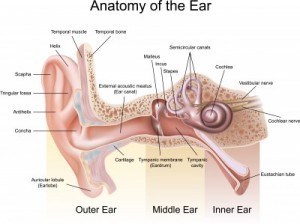

What is a cholesteatoma?

A cholesteatoma is an external cyst generated as a result of a developmental abnormality. A cholesteatoma can be acquired or congenital, with the acquired version being more common. In layman terms, a congenital cholesteatoma (which is what I had) develops because some cells that weren’t supposed to be in the ear became trapped there when the ear drum sealed during development, resulting in a tumor-like growth in the middle ear. A cholesteatoma can be especially dangerous because of the inner ear’s proximity to the brain. If the growth becomes too large, it will eventually eat into the bony structure separating ear and brain, resulting in possible brain damage and death. This is why the doctor’s face went pale when he was examining me. The growth had become so large that it was making my ear drum bulge. If surgery had not been performed, I would have died within a couple of years.

What are the symptoms of a cholesteatoma?

Symptoms typically include ear discharge, loss of hearing, blood coming from ears, a rotten smell, imbalance, and earache. Hearing loss and discharge are also symptoms of more common, less-threatening ear infections. However, since a cholesteatoma can be deadly, it is always considered a possibility when a patient has an earache. Only after concluding that the problem is only a common ear infection should a doctor exclude cholesteatomas.

Why do cholesteatomas affect hearing?

Cholesteatomas can eat away at the bones in the middle ear, namely, the malleus, stapes, and incus. Sound waves are mechanical, meaning that they vibrate, however so slightly, and the ear needs bones to register those vibrations. This is the most common side effect of cholesteatomas: loss of those three middle ear bones. Also, since the cholesteatoma is a growth, it is a mass interfering with the sound waves. In other words, stick some cotton balls in your ears and see how that affects your hearing.

I am, in fact, not completely deaf in my left ear. After finding the growth, the doctors promptly performed surgery and removed it. They discovered that I had lost both the malleus and the incus, but I had a portion of the stapes left, or rather a stub. The doctors laid my new ear drum (made of skin taken from the back of my leg) on top of the stub. It has been judged that I retain about 10% of the hearing that I should normally have in that ear. Essentially, I can stick an ear bud in my ear to listen to music, but anything farther away than that is difficult to hear.

What procedure is needed to remove a cholesteatoma?

Since a cholesteatoma grows in the middle and inner ear, it is difficult to remove via the ear canal. Although in some cases it can be removed by operating in the ear canal, a far more common practice is to make an incision behind the ear, pull the ear forward, and drill into the skull to reach the inner ear. The bottom line is that if you have a cholesteatoma, a procedure needs to be done because it can become life-threatening.

How do we cope with deafness?

Honestly, there isn’t much that can be done about deafness. Believe me, my doctors tried. I had my first surgery to remove the cholesteatoma when I was 6 years old and a second surgery to clear out scar tissue when I was 7. Removing the scar tissue did little to help my hearing, so the doctors then attempted three different surgeries to restore my hearing. All three tried something new, including inserting a prosthetic bone in my ear, and reconstructing my ear canal into an ear cavern. In the end none of them were successful. My doctor suggested hearing aids, but as a child about to go into middle school, I declined that idea.

The good news is that being deaf isn’t the end of the world. I have learned to adapt. I face my good ear toward a person that is talking to me. I use earphones when talking on the phone. I view my disease and recovery as a unique part of me that I like to share with people. I am proud to be deaf.

Ryan Wilson is a professional blogger and writer, and the current editor of Rusin Medical, a health blog committed to providing readers with current medical topics.

August 28, 2012

Is poison for one really food for another?

The first anniversary of What About the Boy’s publication occurs at a time when voters in my country are preparing to make a big decision. It’s no secret to anyone who knows me that I can bear to think about only one of the likely outcomes. And yet, as I encounter the same tired talking points being hurled back and forth every day, by people impervious to ideas other than the ones they’ve already accepted, it seems that discussion has stopped being productive.

The first anniversary of What About the Boy’s publication occurs at a time when voters in my country are preparing to make a big decision. It’s no secret to anyone who knows me that I can bear to think about only one of the likely outcomes. And yet, as I encounter the same tired talking points being hurled back and forth every day, by people impervious to ideas other than the ones they’ve already accepted, it seems that discussion has stopped being productive.

I’m not really talking about national politics or any particular issue, because other controversies can follow the same template. Just to pick an example, at the height of the vaccine debate, opposing sides had ceased talking to each other in favor of connecting with uninformed people and convincing them that the other side was dangerous. (OK, fair disclosure: I participated in that scuffle.) And I’ve seen coworkers—highly skilled, presumably intelligent professionals—disagree so fervently that the encounter more closely resembled a dogfight than a rational exchange of views. Bystanders intruded at their own risk.

Given so much discord, is it possible to back up and find universal agreement on anything?

Probably there’d be no objection from any side to this claim:

Things are not as they should be.

Naturally, saying this presupposes that we know how things should be, although disagreement resumes the minute anyone proposes a fix.

On the plane of existence where we mere mortals operate, I see approximately three alternative responses:

We can trust that somebody (possibly we ourselves) has answers that will make things right (or at least better). Everybody else just needs to be persuaded or otherwise brought into line until that remedy takes hold.

We can observe that most human effort is wheel-spinning that accomplishes little more than elevating one’s blood pressure. Unfortunately, if nothing can be accomplished, that leaves only depression or at best fatalism.

We can acknowledge that things are not only in a mess but are likely to remain that way, and conclude that the only defense is to carve out as nice a niche, for ourselves and our loved ones, as is possible, and take consolation there.

(There may be a Master Plan, in the context of which all this chaos makes sense, perhaps beautifully. I’m inclined to believe that Plan exists. But the focus here is on our current sphere of reference.)

I hadn’t thought of it in these terms before, but all the above scenarios play out in WATB.

Following Joseph’s birth, things most certainly were not as they should have been!

Judy and I believed with all our hearts that somebody would know how to improve the situation, and would be motivated to do so. When we found likely heroes, we gave them our allegiance and trust. And in all honesty, decades later I cannot bring myself to say that we were wrong. Judy went so far as to encourage others to do likewise. Sometimes, the resistance she encountered astonished her.

Joseph’s condition improved—but after extraordinary effort, things were still far from right. We fell so far short of the hoped-for result that Judy simply could not accept what had happened.

Picking up the pieces (with much guidance from Song Yi), I eventually created a nurturing little haven that remains the home base for Joseph as well as his younger siblings. There is indeed a deep consolation in these latter-day developments. I celebrate some of them on my personal Facebook page.

But the original problem has never been resolved, or even adequately addressed. Apparently, no one knows how to do that.

OK, so things tend not to work out so well. Still, each of us does make a difference, in everything we do. It was my hope in writing WATB that a frank portrayal of my family’s experience would add something to the question of how adversity might be handled (or in keeping with the metaphor in the book, how a maze ought or ought not be negotiated).

I also hope that I’ve reflected accurately on our interactions with other people and have portrayed them fairly.

Some of the people in this story disappointed me. Disappointment was in direct proportion either to my justification in expecting something from them or to the extravagance of their unfulfilled promises. Also, there were a few low-lifes who took advantage of our desperation for their personal gain. On the other hand, I owe boundless gratitude to so many people who could offer nothing more than friendship, a helping hand, and the benefit of their own perspective. Without them, none of us would have survived.

WATB supports the conclusion that entrenched positions can lead to ruin. In other words, we do need to continue talking to one another—and listening. All of us, myself included.

August 16, 2012

A glimpse through the window

Several weeks ago, I learned about a little book that is the product of a collaboration between a developmentally disabled teenager and his mother. He contributed several arresting illustrations, and she added written context. I ordered a copy and suggest that you consider doing so as well.

This book provides touching insight into the perspective of Wolf, the young man, as interpreted by the person who comes closest to understanding him. She explains that the things we find important do not register with her son. For example, he has no interest in the authority, social status, or mood of another person, or in passing the time with “small talk.” Instead, he cares about animals, Bigfoot, ghosts, life on other planets, and meteor showers, or as he puts it, “realistic things.”

While I think anyone would welcome this opportunity to consider another perspective, this particularly fascinates me because I’ve spent so many years wondering how my own son, Joseph, sees the world. Unfortunately, in our case we don’t have the avenues of artwork or verbal language. If I know what’s going on in Joseph’s head, it’s only because of clues like his facial expression. He can convey a lot that way, but a very big gap remains for a dad who relies on words as heavily as I do. The situation feels somewhat like the one in the movie Mr. Holland’s Opus, in which the music-loving father comes to terms with the fact that his son is deaf.

For a while, Wolf was drawing disturbing images because, he said, he needed to get it out of his head. His mom connected that preoccupation with the influence of “reality bullies” who believed he needed to spend his time in school. He had concluded by that point that school was a place where “I felt sick in my body and sick in my head.” She advocated for him, as of course a parent must, and won his release. After that, “his artwork was no longer plagued by disasters.”

“The older Wolf got,” the mother tells us, “the more pressure the world put on him to normalize … and it just wasn’t happening.”

I know all too well the feeling of having something not happen. I hesitate to use the word “pressure,” because it sounds so negative. I continue to think that trying to help a child “normalize” is a fundamentally good thing. Still, in so many cases we make our best efforts (granted, with mistakes along the way). We put our trust in those whom we believe merit that trust. We couple our efforts with theirs.

Well, another parent of a disabled kid calls that pursuit “a fool’s errand.” It can make the parents crazy with frustration, let alone the child.

Still, how do things end up going so wrong?

Because I do maintain that something is going wrong here. There is no question that, from any objective measure, including degree of control over his own circumstances, Joseph’s quality of life leaves a lot to be desired. And Wolf’s mom says up front that he “deals with chronic discomfort and confusion” that are due to his condition. It’s entirely reasonable for anyone to want to relieve a child of such problems. These are problems.

What are we to make of this? It’s the question I’ve had the most trouble with, over the years, and the one that other people seem to have the hardest time answering as well. All I can say is that a problem that cannot be resolved to our satisfaction is a problem we must make the best of. We must live with it, and we owe it to ourselves and to everyone around us to make life as good as it can be.

Wolf the Artist provides a fine example of a family doing just that. Please check it out.

August 1, 2012

Cutting to the chase – What’s important & where is it?

At an earlier stage in life, I underlined key passages in everything I read. Didn’t matter if it was a textbook on histology or a play by Shakespeare. I wanted to find the kernel of usable truth in there—the basic idea or fact that could make a difference in how things turned out for me.

In the case of a textbook, read in preparation for a looming exam, the rationale for this is obvious. But often I had a longer view. I assumed that most of what I read might have long-term relevance. I didn’t expect to have time to read the whole book more than once, so I wanted to leave markers to enable my future self to return and quickly find the takeaway among all those less important words.

Then, having extracted the essence from many books, presumably it would be no insurmountable task to assemble all those snippets, look for commonality or some kind of synthesis, and be able to say with some finality This much is true.

And then, of course, to be more enlightened, or more effective—more in sync with the great minds that had gone before. (The notion feels slightly sophomoric at this point.)

I’m reminded of that long-dormant impulse by the advice I hear nowadays, as a blogger, to populate my writing with keywords and bullet points. The idea is to make information easily accessible by web surfers and search engines alike.

I don’t seem to be doing a very good job of that here.

Now, in my day-job as a technical writer, I do know I’m supposed to provide just enough information for my readers to act upon. For example, someone reading the user guide for a new mobile phone has a specific purpose and doesn’t want to spend a whole lot of time accomplishing that purpose. Nobody does. They have too many other things to do.

But let’s say someone needs to get to the bottom of a controversial question, of which there are many in life. In my family’s story, when our baby had a developmental problem, we wanted answers and we wanted them yesterday. Time was passing, and the other kids were leaving him far behind. Doctors told us there was nothing anyone could do for him. But alternative provider A assured us that he could help. Alternative provider B warned us to pay no attention to A and to trust him instead.

We all want life to be simpler. We want to absorb a succinct message and have it be sufficient.

So in a situation like my family’s, eagerness to find a quick answer may drive us to uncritical acceptance of the wrong one. Human nature being what it is, deciding that one option is best can result in a rigidity that prevents us from reevaluating when new information comes along. The trouble is that the discarded choice may be less wrong than it is incomplete. In our story, the mainstream doctors had a valid point—but so did some of the alternatives. By ignoring the pediatrician’s advice, we did improve our son’s quality of life. On the other hand, we could not completely overcome his problems, and in the process of trying we damaged ourselves. The mainstream doctors had warned that we needed to look after ourselves as well as our son, and it turned out they were right about that.

It’s a challenge, distilling my experiences down to a handful of pithy truths. I hope that people can avoid some of the mistakes we made along the way, but to do so they probably need to travel some of that road with us, at least vicariously, on the page.