Gareth Rafferty's Blog, page 16

April 5, 2018

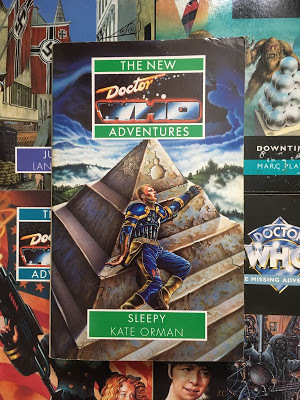

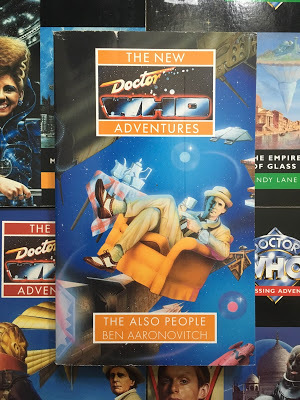

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #70 – SLEEPY by Kate Orman

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#48SLEEPYBy Kate Orman

Misleading title much? Kate Orman’s third book, SLEEPY, moves at roughly the speed of a rollercoaster in freefall. I’m a quick reader at the best of times – it helps with marathons – and I had to deliberately slow down to appreciate this one. That should probably bother me more, but after the lengthy exercise in self-dentistry that was The Man In The Velvet Mask I’m not about to look a gift horse in the proverbial.

It probably goes without saying that we skip the bit where the TARDIS lands and the characters get involved – that’s needless faff by most New Adventures’ standards, and Kate Orman is having none of it. The first chapter (there isn’t a prologue – pinch me) immediately has the Doctor psychically bewildered and confusing reality with a dream-state. This is excitingly disorientating, with snippets of the real world to make it clear how much this is distressing Bernice, Roz and Chris; that note of warmth is especially welcome after Warchild, or Andrew Cartmel Refuses To Play With Anybody Else: Part 3. It’s a sock-you-in-the-jaw way to open the proceedings, which involve a young colony world suffering an outbreak of psychic powers. The whole crisis feels somewhat lived-in before we even arrive, with divisions among the colonists and “powers” being received in different ways, and Orman’s absolute crusade to eliminate dead air means that by Chapter 3 the Doctor co. already have a pretty good idea whose fault the whole thing is. I don’t think a New Adventure has rollicked this determinedly since Exodus.

It would be fair to say it’s plot-driven, then, which makes SLEEPYa step up – in my estimation – from Orman’s earlier books. That’s not to deride The Left-Handed Hummingbird or Set Piece, as they’re both great works of character development, or at least really good character stories. (And if you want to compare them, I think character’s more important anyway.) I just felt that Hummingbird’s complicated structure made it less exciting, and Set Piece concluded a character arc beautifully using some pretty standard monsters. SLEEPY has an interesting problem (the psychic outbreak), interesting characters (including a significant number of Artificial Intelligences), interesting bits (including a quick recce thirty years into the past, told out of sequence) and best of all, hardly any villains. Which is a natty way to get around something that didn’t exactly light up the author’s previous books.

You need antagonists, and you get them: in paranoid sci-fi style, someone is either benefiting from the outbreak or will otherwise want it covered up, so a quartet of psychic operatives arrive to quarantine the colony. Orman makes clever use of first person with these characters, and gives them little lived-in quirks like the fact that their leader (White) has never actually made eye contact with the others. Nonetheless, despite White’s almost default villainy as he faces off against the Doctor, it’s apparent even to him that there is a larger game at play: anyone involved in the incident is likely to be expunged by the next team the Company sends, including him. White has an odd journey as he goes from powerful and in charge to utterly dejected and broken, largely because the Doctor has won over his team.

More obvious villainy comes in the form of a (mad?) scientist, Madhanagopal, whom Bernice and Roz encounter when the Doctor sends them away to gather intel. (In the past, because he has a… somewhat freer and easier relationship with time in this one?) An undercover mission goes quickly awry and leads to some experimentation – par for the course when running the Doctor’s errands, I suppose – but this in itself helps their cause. They also encounter GRUMPY, a computer with a human-ish mind, who sure enough sells them down the river rather than help them. But that doesn’t mean he’s incapable of growth. Madhanagopal isn’t a nice guy, but he’s keeping secrets from the Company, and it’s suggested we’ll hear more from him later. Orman makes the whole vignette more interesting by telling it retrospectively. Bernice, as ever, makes it more amusing.

There’s a general air of things seeming sinister which ultimately might not be. The psychic outbreak has damaging effects, leading to at least one accidental death, and there’s the underlying problem that sufferers are drawn somewhere by a voice that seems to know them. Your spider-sense should be tingling at this point: of course this is going to turn out to be some awful horror from the dawn of time, or else some new thing that wants control of the universe, unlimited rice pudding etc. And Orman sees you coming: this ain’t what it looks like. Disastrous events can ultimately be benign, ghostly voices can be friendly and bad people can change, or at the very least start over. There were numerous points where SLEEPYreminded me pleasantly of The Also People, another book that seemed ready to deflect expectations. That may also have something to do with its contained approach to plot, which in this case is not as “small” as The Also People, but is arguably as concise.

SLEEPY charges through its story, yet also fills it with character stuff. Bernice is quietly preoccupied by the events of Just War; it’s not a showy subplot, but it informs her actions and it’s entirely believable that what happened would stick with her. (Good continuity, have a biscuit. Frankly you should go and read Just War if you haven’t.) Roz is reminded of Ace’s place in the TARDIS when she goes looking for weapons, and occasionally ponders her future there. Chris seems to have a harrowing time of it, keeping a secret from Roz that causes a brief rift in their friendship, and he’s the most affected by the only death in the book. And then there’s the Doctor, who recalls a bet he made (with Death, or possibly the mad scientist from Original Sin?) to see if he can possibly save everybody, just once. SLEEPYmakes a damn good go of that: the psychic officers are not to be harmed unless absolutely necessary, the approaching warship is to be dealt with in a way that also saves its (dangerous) crew, the terrified colonists are somehow to be kept from harming each other and rescued as slyly as possible (including just bundling them into the TARDIS, because thank you, that is clearly the safest option!), and the Doctor seems genuinely troubled by the risk of danger to the AIs – which he helpfully installs with self-awareness. (Or rather, more of it.) I’ve often moaned about how grim and cruel these books can be, and I’d be mad not to applaud a book that does the opposite, and accentuates the positive. It has that, too, in common with The Also People. But it still has darkness, especially with its one accidental death and the Doctor’s pointed realisation that he cannot truly foresee everything. (Unfortunately I know where this is going, though I don’t know how or why said awful thing is going to occur.)

The supporting characters are a little numerous and it must be said, something’s gotta give with a pace like this, and it’s them. But I just about kept up with the doctor (whom the Doctor charmingly greets, seemingly every time, with “Doctor”) and his soon-to-be-wife, another young couple, the various other colonists, the psychic officers, the generally unfriendly Smith-Smith family and most notably Dot Smith-Smith, a deaf character whose communications (via translator drone and sign language) allow Orman to get creative again. SLEEPYtakes a thoughtful approach to deafness, especially in mixing it with telepathy; any knee-jerk assumption that any deaf person would love to hear voices is challenged head-on, as it’s noted that some people get along perfectly well without that sense and indeed, given a taste, would prefer to put the genie back in the bottle. We get some sequences from Dot’s point of view, which allow us to join the (ahem) dots about what’s happening just as she might. Along with some entertaining-rather-than-just-showy dream sequences, Bernice and Roz’s unhappy trip and numerous vignettes when the Doctor has dinner with White – which can be told either from his perspective, where he literally does all the talking, or from White’s as he wryly observes – Orman grabs every chance to make things more interesting. It can still be a little tricky juggling all the names, especially when “Yellow”, “Turquoise” and “Black” get names too, but the whole thing trundles along with such heft that I generally got the right idea from context.

With his bet to keep everybody alive, SLEEPY feels like a challenge for the Doctor. And possibly for Kate Orman. Can you have an exciting story when the Doctor is mostly just stringing the “bad guys” along until the real ones show up – even if we don’t really meet the clean-up crew at the end? Can you have high stakes if you get to the end and, now that you mention it, almost everybody lived? Is it still exciting when it’s basically just, y’know, nice? And can you make this many people feel like important characters, even if you don’t spend that much time with them individually? Broadly, yes. SLEEPY’s main failing is unfortunately part of its charm: it’s damn quick. I would have enjoyed a more patient version that dwelled more on the characters, which makes me wish more authors had the Jim Mortimore itch to revisit old novels. But I enjoyed it a lot as it is, executing a fairly easy-to-follow plot in idiosyncratic style. I was charmed, and I’ll be reading it again some day.

8/10

Published on April 05, 2018 23:48

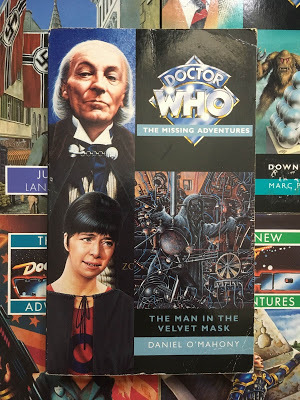

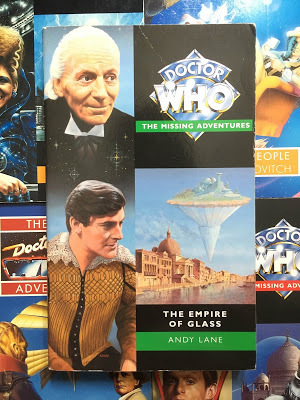

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #69 – The Man In The Velvet Mask by Daniel O'Mahony

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures#19The Man In The Velvet MaskBy Daniel O’Mahony

Aw. This one made me all nostalgic.

Not for the Hartnell era, obviously, which the author seems technically aware of but has no real interest in evoking. Or for my childhood when I first got this book, since I didn’t read it until now. The Man In The Velvet Mask brought back more recent memories of Virgin books – specifically the ones I had to all but prise my eyelids open to finish. It’s been a while since I had an honest to goodness ordeal in book-land, where just getting to the end feels like an achievement akin to slaying a Kaiju. Still, I did it! The city is safe again... for now.

I know it has its fans, but they’re the first to admit it’s a marmite book. And it ain’t the author’s first. Falls The Shadow, matter-of-factly referred to in the blurb as “mould-breaking” (O RLY?), also played fast and loose with things like plot, character and good taste. It was a book uncomfortably keen on sadism, which makes it hilariously unsurprising that The Man In The Velvet Mask goes the whole hog and features the man for whom sadism is named. I mean god forbid we psychoanalyse an author, but at this point I wouldn’t leave him alone with any small animals.

The villains of Falls The Shadow had some interesting aspects, their existence being a knock-on effect of the Doctor simply arriving in times and places, erasing what might have been. But as characters they didn’t have a dimension between them. They were sadists for a laugh – because well, sadism innit? – and that pervading sense of self-serving meanness hangs over The Man In The Velvet Mask. It’s a visceral and ugly book, dwelling on typically icky (and narratively absent) dream sequences and delighting in Giger-esque settings, all of which is its own reward. Once again, Daniel O’Mahony gives the impression that great care has gone into the prose, and any strikes with a red pen would be met with a snort of derision: “You just don’t get it, maaan!” It’s just as fond of random violence as the abominable Strange England, but this author at least seems to perceive a pattern. Lucky him. All the deliberation and care in the world can’t animate an AWOL story.

Again with trying not to second guess the author; I don’t know how meticulously the plot was laid out before he wrote the book. Shall we assume, very? If so, it doesn’t come across that way. Upon arriving in an obviously changed France of 1804 – the Doctor deduces this by stepping out of the TARDIS and reading a poster, how thrilling – the Doctor and Dodo go their separate ways and become embroiled in... the fact that it’s different, I guess, with a vague view to fixing it. There’s no plan to speak of for almost the entire book, since there’s correspondingly little clarification on what has changed and what, besides the presumable need to make it all nice again, is at stake. (When we finally do get the villain’s evil plan you can barely hear it over the bellow of Oh Well None Of This Will Have Happened Anyway. Ditto the threat of a French/British conflict. Who ruddy cares?) Sheer bad luck places this book quite soon after Just War, which handled its own alternate history with wit, gravity and originality. D’oh.

Lance Parkin was just all round better at this, jumping off from an easily recognisable historical fork in the road and grounding it with the experience of the regulars. O’Mahony has the Doctor vaguely potter around the villain’s Bastille, wrestling with his own mortality which doesn’t exactly relate to the present crisis; meanwhile Dodo falls in with some (obviously weird and metaphysical) actors, and starts a relationship with one of them, occasionally getting so involved in the Marquis de Sade play they’re performing that she uses another name. (Some of this echoes Managra, another book with a doolally view of history and an author eerily certain of his business. Except Managra was fun to read.) This is infamously the book where Dodo gets an STD, and it’s difficult to follow that with any meaningful analysis. Yep, that happens. What the freaking hell, dude.

The relationship behind said probably-meant-to-be-poignant sex keepsake isn’t strong enough to warrant such an odd water cooler moment. (What the hell would be? But even so.) Dalville likes Dodo immediately and makes it clear he wants to corrupt her. She is... fine with this? And after losing her virginity (I got too much detail so here you go as well) she continues to buzz around him. Problem: Dalville isn’t an interesting character. None of the actors are, some of whom are aliens, or in a supernatural disguise, which only adds to the anonymous blah of the lot of them. (The text describes them as “a parade of faces and false names” which gives the unnerving impression that they are meant to be a weird, colourless bunch of blah.) Nor are the two or three murderous characters who flit through the story and kill the girl Dodo replaces in the acting company. The Doctor fails to save her and then lies about it to Dalville; that either didn’t come up again or else I missed it.

Neither the Doctor nor Dodo is fully aware of what the other is up to, and both seem to osmose through the story in a sort of fugue state. (Rather like the one I was in.) You might at least find O’Mahony’s choice of characters interesting. Nobody writes about Dodo, a companion who didn’t quite find an audience and was so far from beloved that she left the show off-screen, mid-adventure, and Jackie Lane has had seemingly no interest in touching the character with a barge pole since. This book doesn’t especially like her either, highlighting her unspectacular looks (including, at one point, her flat chest, because this book is charming), and her need for attention so craven that she used to fake itching fits to get a few stares at her own birthday party. Yeah, so glad she got a book to herself and Leela didn’t.

By separating her from the Doctor the lingering (and you would think, pressing) question of “Does he actually like this random person who once barged into the TARDIS” doesn’t come up much, although he does aptly observe that she is effectively Susan’s reflection “distorted in a rough mirror.” Sure enough, the experience serves to highlight the fact that she will be leaving soon, not that she goes willingly so that’s all rather pointless, isn’t it? Perhaps the cover artist should have given her a T-shirt: “I Starred In A Book And All I Got Was This Lousy Venereal Disease.”

The Doctor is somewhat more recognisable, although his hurtling towards his own regeneration, which is a little while off actually, is a bit too try-hard in terms of interesting characterisation. Why is he so weak and feeble now, when the Doctor we see in the next TV story is if anything revitalised? (I think O’Mahony missed a trick setting this after The Savages, in which some of the Doctor’s life force is stolen. On my telly watch-through of the Hartnell era, including missing episodes, I thought this led serendipitously into his regeneration. But it isn’t spelled out here. Oh well.) Interesting side-notes include a reference to the Doctor having one heart in his first incarnation, which probably explains an inconsistency somewhere; the second heart came with the regeneration, apparently! Despite it all, O’Mahony’s Hartnell has the right measure of crotchety bluster and warmth, even when talking to a severed head on a spike or the Marquis de Sade. But it’s a very small plus in context.

In amongst this vague dawdle through a generally unpleasant Paris, not punctuated with enough relatable characters for the incongruity of it all to matter a damn, is de Sade, a slithery relation of his called Minski and the titular man in a velvet mask. I learned very little about de Sade here, but the trajectory of his story, and the identity of the masked man is all pretty obvious. (Praise be that something here is.) O’Mahony, as I’ve mentioned, tends to divert all power to the prose machine, so you’ve got tenses swapping (to denote being outside of regular time, which is at least explicable), bits in italics or brackets, gothic dream sequences and – need you ask! – a thoroughly weird prologue that combines much of the above. There is a general self-consciousness about how weird it all is, which for me is just pointing at the window dressing. I am here for story and meaningful character development. At points my eyes rolled over the words as pleasurably as if they were laying tarmac, and more than once my brain revolted and I nodded off. Like this review, it just goes on and on, (self?) flagellating.

There are moments where it attempts to lighten up. The chapter headings are in an oddly chirpy mood throughout (see “Carry On Chopping”); it has some literary allusions, generally Shakespeare, which mostly reminded me of books I liked more that did that; and characters occasionally use jolly colloquialisms. After all, you might argue, Donald Cotton wrote conspicuously dry dialogue (for the setting) in The Myth Makers. Yeah, but that worked in context. Lightness doesn’t suit The Man In The Velvet Mask at all.

I think it comes down to how you felt about Falls The Shadow. If you couldn’t get enough of its changing imagery and peculiar horrors, you’re in luck. Whereas if you struggled through its mostly incidental story and random violence, reading The Man In The Velvet Mask may be an exercise in punishment of which the Marquis de Sade would approve.

3/10

Published on April 05, 2018 00:24

April 3, 2018

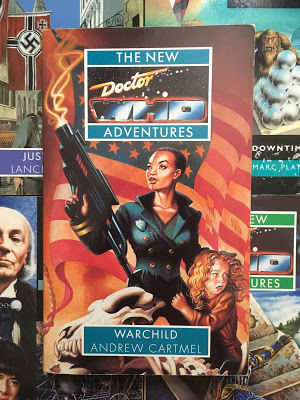

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #68 – Warchild by Andrew Cartmel

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#47WarchildBy Andrew Cartmel

Good heavens, is that a rainbow? The birds are singing, I can hear people bursting into song too, and – yes! Now it’s raining gumdrops! This can only be a novel by Andrew Cartmel, full of his characteristic vim and cheer!

Oh all right, fine. Despite his knack for clever prose that keeps you reading at a quick pace, Cartmel is narratively known for crossing his arms and huffing until the party comes to an awkward halt. Warhead was the first really dark New Adventure, followed by Warlock which was even more determined to leave a mark – preferably a bruise. Cartmel’s world contains wonders and traumas, and he favours the latter. He likes to keep the Doctor and co. in the wings, just in case you were getting too comfortable, and that has never been more apparent than in Warchild, where they barely guest star in the action. The War Trilogy has long since gathered a principal cast of its own and they’re the ones who push the story forward. When it deigns to move.

I’m at odds with some readers on this one, and apparently Cartmel himself. Going by this illuminating interview from NZDWFC he wasn’t impressed with Warhead, feeling that the plot wasn’t really there and was too fragmented. He thought Warlock was better in general, more focussed and story-driven. It’s been almost three years since I read it (!), but I remember Warhead’s pieces falling nicely into place, whereas Warlock moved a couple of chess pieces very slowly and not far. It also made its moral points with the finesse of a frustrated dog owner coming home to a puddle. Warchildis mostly concerned with the middle instalment, and quite frankly, if you haven’t read it then this is not for you. Cartmel’s second and third books seem to occupy not only the House at Allen Road, but also the odd assumption that these are the only books in the New Adventures series. (Indeed, he’s completely forgotten the futuristic setting of Warhead, which was relatively decades ago. Maybe all the effort to fix the environment, which was then almost beyond repair, led to them ditching hover-cars and the like? Let’s go with that.)

Following the harrowing events of Warlock, Justine and Creed have raised three children including her son from her first husband, the psychically-empowered Vincent. Creed still works for a shadowy government agency and while at the office he fends off his attraction to a co-worker, Amy. Back at home he isn’t getting along with Ricky, his stepson. Ricky is developing strange talents as he moves from school to school and is desperate to stay out of trouble. Shadowy forces would rather he fell right into it. Meanwhile a mysterious plague of violent dogs is tearing London apart, and Mrs Woodcott – the strange figure who showed up intermittently in Warlock, I’m still not sure who she is – “recruits” people to fight them, i.e. plucks them out of an airport if they remotely look like they can deal with the situation. Roz is one such recruit, Creed soon joins her. At the House in Allen Road the Doctor seems to be growing a dead(ish) Warlock character in a test tube while Bernice looks on.

I believe we were saying something about plots being too fragmented? Warchild pulls its threads together, but even then it’s difficult to shake the randomness of a dog revolution, despite its roots being established in Warlock. (One of the characters, Jack, literally lost his mind and it ended up in a dog.) Cartmel takes the no-watershed-no-problem approach of the New Adventures to extremes with Roz and her new colleagues battling a never-ending onslaught of bloodthirsty animals. It’s a curious follow-up to the intensely animal rights driven Warlock, killing as many dogs as possible; I wondered if it was meant to signal some kind of tragic retribution for how they’ve been treated, but it’s really all to get the Doctor’s attention, or it’s part of an evil scheme. (Not massively clear which.) And it feeds the book’s central idea of using influence to control crowds, specifically with alphas, which is Ricky’s special power.

Sure, it’s themed, but things in Dog-Land get thoroughly weird as they’re all driven by one ancient dog who occasionally stands like a person; a few others fool a motion sensor by standing on top of one another, Muppet-man-style, except with more bloodied footholds. I’m not making this up. Roz and her crew keep circling back to the house of a devastated flight attendant whose fiancé has been mauled, and it becomes their de facto base. Considering this is a state of emergency it doesn’t seem to affect more than a few square miles of London, which makes Mrs Woodcott’s “conscriptions” seem even weirder. I wanted the action to spread out a bit, but much of it takes place virtually in real time. But then, does it, with Creed having time to do all his stuff, then get over here from the US?

It’s not a plot-heavy book, but it sure takes its time. And that’s not to say it’s a slow read, as once again Cartmel’s prose is evocative but expedient, and the thing rollicks along. We feel things when the characters do, including myriad unpleasant secrets, and moments of action (such as a stalled plane engine) come with absolute clarity. It came as no surprise reading in that interview that Cartmel is a fan of Stephen King, as his writing has the same pulp pace and satisfying rush of detail, and sure enough, the same lopsidedly male-centric sexuality. Years after rescuing Justine from a forced abortion and a life of sex slavery (“Hey kids, I got you that Doctor Who book you wanted!”), then immediately sleeping with her and ending her marriage, Creed can’t quite ignore his gorgeous co-worker or women in general. (On a cranky parent at his son’s school: “the finest pair of firm tanned breasts that rich widowhood and elective surgery could provide.”) His marriage is difficult – almost as if the whole thing started in the aftermath of a nightmarish ordeal when neither of them was thinking straight – but he still has time to admire Justine: “Even after all these years of snot, diapers, madness and children she still turned him on.” / “...Creed deliberately dropping back for a moment so he could watch her sweet ass in those black culottes...” (The latter is followed by the slightly hmm observation that their older daughter now has the same walk.) Even the narrative, Creed-less, takes a moment to admire a neighbour’s “spectacular breasts”. It’s odd squaring all this with Andrew Cartmel, who has been fiercely interested in writing strong women, crafting Ace into someone with depth who can more than take care of herself. Sex in these books is always a little conspicuous, but in Warlock and Warchild it’s frankly a bit creepy.

At least he doesn’t let anybody get away with the last-minute liaison in Warlock. The wisdom of that decision has been in question ever since, at least somewhere in Creed’s mind, and it’s an instigator for the plot – in case you were wondering where Vincent has got to, he was devastated after those events and he’s the villain now, hoping to craft Ricky into a political weapon. It’s not much more complicated than that, and neither is the writing, which reduces a once main character to a sneering spurned lover / bad guy stereotype, complete with monologue. I already felt sorry for Vincent in Warlock, but the kid in Warhead deserved a more gradual finale. In any case, it seems the jury is still out on random dangerous-situation hook ups after all, as the distraught stewardess is probably going to sleep with one of Roz’s crew, because “they’re both extremely vulnerable. They need each other at this point and if they can help each other heal their wounds then that’s good.” Full disclosure, her boyfriend was gored to death by the family pet, hours after proposing to her; the other guy peed himself, after what seemed like sheer pages of conversation about needing to go. Yes, those things seem equal and this all makes sense. Sex approved!

The book seems most centred when it’s following Ricky at school, where his bullies have the unmistakeable ring of Stephen King, complete with harrowing home lives. (One of which comes to fruition courtesy of the ringleader’s deranged father.) Those events are only tenuously related to the Doctor and co., with Chris posing as a Buddhist teacher and inciting trouble for Ricky just by being there, whilst also keeping an eye on him. (This would seem a deliciously Doctorly contradiction if both those things were entirely the Doctor’s idea.) The book builds and builds to something involving Ricky, but he’s so determined to avoid his destiny that he almost succeeds. A scene at a train station makes creative use of his powers, as he tries to flee to a new life, relaxes for the first time in ages and sends everybody in the surrounding area to sleep. A tense stand-off between Roz and one of Creed’s co-workers, which more or less gives us the arresting front cover, comes and goes without a lot of fuss. The final confrontation with Vincent is left so late, and is so hasty in general, it’s like Cartmel considered not including it at all. Things end, need you ask, with very few happy campers.

The overall feeling is that Cartmel has this cast of characters who need to progress to the next stage in their story, and oh all right, if you absolutely insist, the Doctor can be in it as well. The Doctor claims a degree of responsibility for how it all plays out – the dog situation is about him by proxy, but then some of it’s Vincent? – but he spends a fair amount of time just pottering about in Allen Road. Roz’s ease with violence can be said to follow her behaviour in Just War, but then it’s pretty much indistinguishable from post-Deceit Ace. Chris hides in plain sight for much of the novel, and after two books Bernice somehow continues to evade Cartmel’s interest altogether.

It’s not an especially enjoyable experience for anybody involved, and I don’t want to sound like any sad or unpleasant story is an automatic fail with me; you can’t have light without dark. But there’s predominantly one mood in Cartmel’s Doctor Who books – two if you include “make it as little to do with Doctor Whoas possible”, or so it seems by now – and that’s grim. This approach worked best for me the first time, when he had (for my money, if not everybody’s) a decent plot to ladle it over. Warchild is more like a collection of surly new bits than a new story, and as such it doesn’t leave me with much to think about, or apparently to say. It’s less of a drag than Warlock. I’d rather read Warhead again.

6/10

Published on April 03, 2018 23:45

April 2, 2018

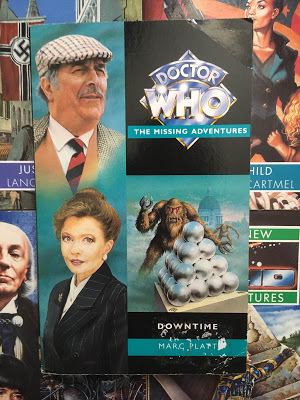

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #67 – Downtime by Marc Platt

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures#18DowntimeBy Marc Platt

We interrupt your regular Missing Adventures to return to the rather odd world of fan films, which vary in infamy, production value and tenuous association with Doctor Who. At least this one has some familiar characters in it, so (unlike Shakedown) won’t need a lot of work done to resemble a Doctor Whobook. More’s the pity, since the off-video parts of Shakedown were arguably the best bits.

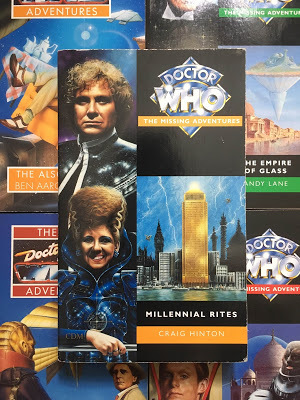

For his script, Terrance Dicks had two monsters and a single (pretty decent) shooting location, so it was logical for Shakedown to be a smash-and-grab actioner with no lofty ambitions. It got the job done. Downtimeis a different beast. Steeped in continuity and earnestly trying to build on it, with a plot largely reliant on metaphysical mysticism, it’s the long-delayed third act for the Great Intelligence. (Millennial Rites doesn’t count.) So quite ambitious then, especially with a script and novel by Marc Platt, who wrote a brilliantly complex Sylvester McCoy story… and then a New Adventure that was like reading spaghetti bolognese. In all honesty, this could have gone in either direction. (Platt’s Big Finish output is similarly all over the place.)

And I’ll own up right now: I haven’t seen the video.* I’ve got it lying around but I thought it would be fun to look through the other end of the telescope, see how well Downtimeworks as a novel first. I’ll watch it later. For now I’ve got no idea which bits were added for the book, though I can hazard a few pretty obvious guesses.

(*I have since seen the video. It’s, um. Some of it’s all right. If you’re at all interested in Downtime and you are able to pick and choose, I would suggest getting the book instead.)

Our first Obviously Added Bit is the Web Of Fear epilogue, for the Second Doctor and friends and then for the Brigadier, the latter tentatively setting up UNIT. (This is done with more aplomb than Terrance Dicks himself in his Web novelisation; he absolutely crowbarred it in there!) Platt reminds us how nervous Victoria could get on her travels, and how mindful she is of her father. Mown down by Daleks, but just as much by fate for helping them in their schemes, he left a hole in her life that couldn’t be filled. The Doctor and Jamie were there, and that was that. It’s easy to forget that some of his companions had unhappy reasons for stepping into the TARDIS, and Platt embraces this wholeheartedly with Victoria – a companion that, if I’m honest, never seemed like much more than a scream factory. But why should she be anything else? She wasn’t travelling for the fun of it or to see the universe. She more than likely just wanted to go home, except her father was dead, and her home had blown up. Her decision in the very next story to step off forever and live with the first decent people she’d met makes as much sense as anything else. Even if it’s not a be-all, end-all happy ending for her, it’s a chance at stability. And perhaps any time would seem like the wrong century when your own world has gone.

Downtime confirms that it wasn’t enough, lovely as the Harrises were. In a lengthy but satisfyingly packed first chapter, Platt finds Victoria trying to make it on her own years later. (She still keeps in touch with the Harrises.) She works with antiquities, privately catches up on the facts of the 20th Century while she’s doing it, and spends the intervening time dodging a belated will from her father. She also feels a tremendous longing for something. She occasionally drifts out of her body and moves towards what seems like her father’s voice, coming from Det-Sen Monastery, of all places. Platt’s penchant for odd concepts isn’t new to me – see Ghost Light, “Ooh!”, or Time’s Crucible, “Huh?!” – but he makes consistent use of out-of-body experiences here. It makes sense with a villain as disembodied as the Intelligence, and it makes a lot of sense for Victoria, who of all people does not have her feet on the ground. She eventually finds Det-Sen and, after a charmingly not-to-be rendezvous with a promising new friend, awakens something she shouldn’t. And then we catapult ahead to the present day (circa ’90s) where – bombshell – she’s working with the Intelligence.

On the face of it this is an odd way to treat a familiar character, even with the Intelligence’s record for possession. And there is a degree of coercion involved, but it’s less than you’d think. In the end Victoria seems to want to belong to something so badly that this will do, and she lets it happen. (Possibly I’m reading too much into that, and the video makes it clear that she’s really just under the ’fluence. Update: the video isn’t clear about much.) She occasionally laments the absence of the Doctor and wonders what he’d say of all this. Dealing with things in his absence is unavoidably one of Downtime’s themes, and it does an excellent job with Victoria’s not-particularly-happy story, without making such a miserable hash of it that you wish they hadn’t bothered asking. And it doesn’t end very well for her, which I’m guessing is where the video left her, but the book’s epilogue lets us down more gently: it turns out the Doctor kept coming back in different incarnations to make sure she was okay. Of course he was too late, but it’s a beautiful thought, and a sweet note to end on. Moments like this, and all the references to Web Of Fear and Evil Of The Daleks, feel much more relevant and earned than your average bit of continuity. (As for referring to the previous Yeti incidents as NN and QQ, which were their production codes on television, that’s more of a Nerd Alert – but then, shame on mefor knowing that.)

The Brigadier is in the book slightly less, but no less significantly; Platt has a troubled future in mind for him also. Lethbridge-Stewart becoming a maths teacher never made great heaps of sense to me, but then most careers would seem rather odd after UNIT. His retirement dinner is getting steadily delayed as strange dreams alert him to the Intelligence’s return, and danger creeps back into his life, possibly via UNIT itself. More importantly, his daughter is being menaced by something and she needs his help. Suddenly the conflict of his personal life and his work life comes to the fore – an open wound he never talked about on screen, but one that fits the facts well enough.

Kate has the same name as her New Who counterpart, but that’s the only real similarity. This one doesn’t want to know her father following years of familial ignorance (courtesy of his day-job), and she hasn’t even mentioned having a son. Seeing her dad again doesn’t patch it all up – after some tender words, she still decides that if she has to keep her son away forever to keep him safe then she will – but sure enough, things improve. There is some very nice writing here, as the Brigadier wells up seeing a picture of his grandson, and Kate begrudgingly admits the need to have her father around. (“Today, rather to her horror, Grandad looked terribly solid and reliable.”) Frankly I don’t like Kate all that much; it’s a fannish instinct, to not understand how someone couldn’t like the Brigadier very much. But she’s also not terribly useful in a dangerous situation, and following a brief possession from an actually quite benevolent force trying to stop the Intelligence, she goes on and on about feeling “soiled” by it. Oh, give over.

On a more positive note, the writing has a lot of time for little observations that make the story brighter. Not to diminish the generally lovely prose surrounding Victoria’s melancholy life – “That voice was in her, too. It embodied the despair and loneliness of a being cast out from its old and native haunts.” – but even small characters have their own conflicts, many of them funny. There’s an acerbic UNIT officer: “‘The old bugger probably choked to death on a mince pie.’ It was a fate he wished the precocious young officer might enjoy as well. But it was a long time to wait until Christmas.” We briefly meet up with Harold Chorley, whose elderly malaise seems tragically apt: “He called her Sandra and kept staring over her shoulder as if he expected a cue card to materialise out of the ether.” The Brigadier’s family history is at one point related with poignant amusement: “Anyway, Fiona had never talked to him either, not for years. So that evened things out a bit.” And the Brig gets at least one hilarious line, not including a pretty naff attempt at remaking Five Rounds Rapid: “‘I give up, Hinton,’ complained the Brigadier. ‘Am I asleep or are you dead?’” A scene where he is forced to bluster and stall the bad guy in his finest Doctor impression makes amusing light of the Doctor-shaped hole in the story – and in their lives, of course – as does the hilariously sharp observation that to the Doctor, the Brigadier isn’t so much a magician’s assistant as a bewildered volunteer from the audience. There is also a delightful dollop of world-building surrounding the Yeti, as in the animal ones, which have been proven to exist and can be seen in zoos. They’re named after Travers.

On a less positive note, I’ve hardly mentioned the plot or the villains yet, because that’s where Downtime comes up short.

It can be tricky piecing together what’s good or bad because of budgetary restraints, since Platt surely has license to make everything a bit grander in print, but if you came here for the Yeti then you’ll be disappointed. They do eventually show up, at first in a genuinely horrifying scene of a control sphere piercing a man’s chest and turning him into a Yeti – I’m not sure that’s how these things work but yep, that’s successfully horrid – and then in a full blown UNIT battle. (Which makes me wonder why the Yeti are in this so little. If they had a bunch of them in the video, where the heck are they?) Platt tries conspicuously hard to get chills out of web – like, on its own – and occasional beeping spheres. It’s a bit limp to just point at a few bits of iconography as if that’ll do. Web and control spheres, to me, are signifiers of something else. As for the human face of all this, Victoria’s inner struggles are perfectly interesting – see above – but her cohort in crime, Christopher Rice, is considerably less so. At least, I think that was his name? There are several more or less interchangeable characters involved, apologies if I’m naming the wrong one. Shrug. Professor Travers eventually shows up, having been completely ensnared by the Intelligence – although he gets away from it briefly – but he’s not put to a lot of use. It might have been more interesting, not to mention creepier if he was more present in this. (The presence of Deborah Watling’s real dad is a nice touch, though, adding serendipitously to her character’s journey.)

Victoria, some forgettable men and an occasional Travers aren’t much to write home about until the Yeti go ape, so Platt comes up with an intermediate baddie. If you’re more familiar with Downtime than I am, you were probably waiting for this bit: aren’t the Chillys rubbish? To back up briefly, Victoria (coerced?) is financing New World, a computer-based university that ostensibly makes teaching quicker and easier, but is obviously a cult and a front for the Intelligence. It aims to use the internet to take over the world. (Hey, didn’t New Who do that as well? Platt should sue!) The students wear caps and headphones and are brainwashed – the “Children of the New World”, they are known as Chillys. And I just… I can’t believe that’s the name he went with. They sound like ingredients, or a popular chain of restaurants, or some sort of sweet. It’s a really weird abbreviation. And they’re just a bunch of bloody teenagers with headphones on. That’s it. Kate calls her dad and puts her son into hiding, turning her life upside down because a bunch of plebs are hanging around. So? They don’t do anything! Even the prose can’t seem to give them a break: “There were also increasing numbers of accusations about computerised brainwashing cults and the general appearance and behaviour of the Chillys.” Oh no! Their general appearance is coming to get us! Quick, walk briskly in the opposite direction! It must have seemed like a great fix to have some vaguely uniform baddie to fill up the background in this, all for the price of some hats, T-shirts and dummy headphones, but it helps to actually make them antagonistic in some way.

Speaking of antagonism, the plan isn’t terribly clear – let’s assume it’s “come back and take over” in the main, but I didn’t catch the specifics beyond that. In one eyebrow-raising cutaway we see a train derail and flail about in the air, and a lot of computers pick themselves up and jump about, which is pleasantly weird. (Again I’m not sure that’s how the Intelligence operates, but why not. Guessing these bits might be new to the book!) New World just isn’t very concerning, since it’s filled with nonentities in baseball caps and stuffy villain-ish characters doing… something or other. It’s hard not to imagine the rest of the world giving the place a bemused glance at best, then just getting on with their day. UNIT are having an identity crisis in amongst all this, which is sort of interesting, but that doesn’t go anywhere interesting. (Some of them are possessed. Shocker?) It’s neat to see Crichton again after The Five Doctors, and there’s some slightly confusing input from Captain (aka Brigadier) Bambera, which means this story happened before Battlefield. Pausing the story to go “Hang on, where does this go?” isn’t the best idea. (Maybe it’s a reference to UNIT dating.)

Sometimes your heroes are only as good as your villains, and apart from the quite interesting personal dramas going on for Victoria and the Brigadier there’s not much of a fight to be having. (Save for the UNIT scrap at the end.) The Brigadier just sort of ambles towards New World and the climax of the story from the outset, while Sarah Jane Smith – who I haven’t mentioned yet because this is how relevant she is – circles the same. In the end, one of their best ideas is pulling a plug out. The Brigadier’s moment of impersonating the Doctor might be a solid character beat for Downtime, but it also inevitably feels like a writer going through the motions. I was left wondering how they defeated the Intelligence at all without the Doctor’s help, and if the thing could really have been trying in that case.

It’s a very different approach to Shakedown, which bundled its economical script into a 43-page “novelisation” and beefed up the before and (less so) after bits. Downtimejust novelises the video in earnest, and while it’s never noticeably padded, there’s a dearth of plot. Platt, as is his way, grabs onto some interesting ideas here and there: the repeated theme of astral projection, with the Brigadier having whole disorienting conversations in another plane of existence, is an unusual way to advance the plot, but memorable. That’s where Daniel Hinton comes in, the pseudo-heroic computer-whiz / powerful mystic / school drop-out who infiltrates New World, contacts the Brigadier in his dreams and ultimately helps save the world via Kate. (“I’ve been soiled!”) His character is pivotal, but all over the place; his convenient magic powers could definitely do with stricter limits. Then we have Sarah, who shows up presumably because Lis Sladen was happy to be involved and not because Platt had anything for her to do. If anything, some of her action could have gone to Kate and helped her contribute a bit more. The dead end is even more obvious when he’s managed to make Victoria, a character for whom screaming was a super-power, interesting.

There’s a surprising amount to recommend about Downtime, which sets its sights on what certain characters did next and commits to that. I mostly come to the Missing Adventures for the characterisation, so hooray. But it’s not all like that, and despite the latent novelty of the thing – a Doctor Who story without the Doctor, another bout with the Great Intelligence – it ends up all seeming a bit naff and uneventful. It feels, maybe unsurprisingly, like a low budget production. But you don’t need a lot of money for thoughtful writing, and thankfully there’s some of that on offer.

6/10

Published on April 02, 2018 23:40

April 1, 2018

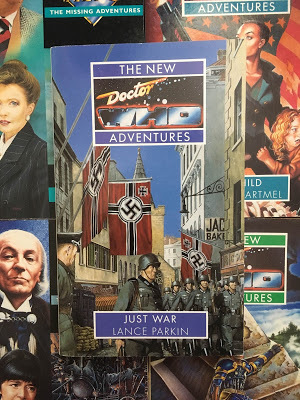

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #66 – Just War by Lance Parkin

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#46Just WarBy Lance Parkin

Doctor Who novels, meet Lance Parkin. The soon to be ubiquitous writer arrives with the satisfying crump of a grenade in Just War; along with The Also People(and in a sane world, Sky Pirates!) it isn’t so much “Love it or hate it” among fans as “Love it or what’s wrong with you?” Even trying to keep my objective hat on, it’s difficult to believe this is his first novel.

What’s so good about it? Well as morbid as this sounds, setting it in the Second World War has the odd effect of whispering “This is going to be good” before you’ve even started. Just War begins “Once upon a time, when the world was black and white”, and where could the stakes of good and evil be clearer? That iconography is part of Doctor Who, thanks to certain shrieking pepper-despots who live to exterminate their inferiors. One of their (best) stories is a resounding echo of the Blitz. Also one of the earliest New Adventures, Terrance Dicks’s Exodus, melds the old “What if Hitler won the war?” gag into a thrilling Back To The Future II riff. War is hell, but it makes good copy. You just know where you are with this stuff.

But then, is any of it new? Just War is set during the war for the express reason that the Germans will apparently win, and the Doctor and co. must find out how that happened. Isn’t that a bit too close to Exodus? I approached it with some trepidation over that, but in the end Parkin handles the subject differently. There is no Nazi-ravaged (or worse, Nazi-but-not-that-bad) future to shock us into action. In what is now the time honoured structure of Doctor-Benny-Roz-Chris books (and I am in no hurry to complain), they are already in the thick of it, carefully living through the past with the uncomfortable knowledge that soon it will all go wrong – or at least more wrong, it being WW2. They don’t know how, where or exactly why. The book takes its time circling back to there even being an alternate future we need to avoid, for the most part simply playing out its war story on several fronts. I occasionally thought, well it’s all very good, but are we sure it needed the Doctor and co. at all? Also, Nazis, evil: yup. Did we really need another memo to confirm that?

One of the book’s strengths is that Parkin seems fully aware of the stories you’ve already heard, and he came prepared. Hitler doesn’t feature at all. Most of the action occurs in the small, oddly critical island of Guernsey. When it comes to the Nazis they will obviously act like Nazis, but they’re also going to provide reasoned debate as to why they do what they do; quite a lot of words are spent on it. And the heroes will do questionable or downright awful things. Yes, this includes the Doctor – pretty much mandatory, isn’t it? – but for once there’s plenty of blame to share. It’s altogether more thoughtful than just a mission to put history on its correct course. The here and now matters, probably more so.

Bernice is living in Guernsey under an assumed name. (This won’t hide her effervescent personality from the reader, and in any case it doesn’t last, so this probably isn’t a spoiler.) The first chapter is a seasoned atmosphere-builder about life in that time, and it’s full of pregnant looks and things unsaid, as German soldiers act like they own the place and life tries awkwardly to go on around them. I assumed the book would linger there, as does Bernice, but things quickly escalate: a retrieval attempt from the Doctor goes badly wrong, and Bernice kills a young Nazi. She does this for good reasons, wanting to protect the identities of the women who have sheltered her, and she does it almost without thinking – it’s shockingly quick. Soon she’s so appalled by what she’s done that when the time comes for the Nazis to retaliate, gunning down civilians at random to clarify the pecking order, she crumbles and surrenders.

Her interrogation goes almost exactly as you would expect, humiliation and torture in quick succession, but Parkin uses it to examine her character. She is ordered to strip naked; she does so much easier than they would expect, even offering pithy commentary at her different social mores. All the time she is afraid and her resolve wobbles. Later, sleep-deprived and wounded, having told her real life story a bunch of times to no avail, she is so beaten down and delirious that she thinks “If this Doctor existed, he would have rescued [me] by now.” The bravado is a front, as readers know by now, but more importantly a survival instinct. The layers of sneering cleverness are (of course) like the post-it note revisions plastered over her diary: false, but also intrinsically who she is. I’ve wanted her to shed a few of those snarky layers for ages – perhaps not this literally! – and admit a little more frailty than she’d rather. Just War gives her both barrels. (I’m not surprised Big Finish felt confident enough to adapt it without any Doctor Whorights. It’s quintessential Benny.)

We get all of that without taking the most obvious route, all but destroying her. Bernice hates herself for Gerhard’s death, but it was what she had to do. She is broken by her torturers, but is also more than able to get away under her own steam; we don’t even dwell on how she does it, her confident pre-summary being more than sufficient. She traps her “nurse” in a morgue drawer, uncertain of whether there’s enough air inside, because guilt over a murder isn’t the end of this fight and she has every right to retaliate. Bernice isn’t perfect and she doesn’t always do nice things. As noted in The Also People, it’s a commonality with the Doctor that is becoming more apparent.

Their relationship (in general, but pointedly here) also doesn’t take the obvious route. The Doctor ostensibly betrays her by letting Wolff torture her, leaving her to get away on her own. The obvious thing would be to put another brick in the wall of “I shouldn’t trust you and I’ll be going soon”, ala Ace, but Bernice has always seen the Doctor a bit more clearly. When he apologises it is enough for her (although she won’t tell him right away!), and soon after her ordeal she writes a very sweet note asking him to come and rescue her, leaving it safely stowed for the future, Doc Brown style. (Who had The House At Allen Road? New Adventures Bingo!) The thing is, he tried – but the TARDIS overshot. When the inevitable telling off arrives, because she did wind up tortured by Nazis after all, there’s nothing he could realistically have done better. (And even if he wanted to, the note confirms that she made it to Allen Road on her own; he’d be messing with time if he got her out of Guernsey prematurely. Come to think of it, maybe that’s why he missed?) All of which is probably why, once he isn’t looking, Bernice quietly lets him off the hook.

Parkin has plenty of time for the other regulars, most notably Roz. She has a practical wit that marks her out from Benny, noting that a pretty ’40s roadster is “Great. But trust me, it’ll never get off the ground.” The dreaded romance-that-surely-will-not-work-out lands on her, as she begins a gentle love affair with a young British soldier. Again, the author knows you’re all expecting him to get blown up or torn away, so Roz goes into this clarifying that she won’t be here long. Their scenes are genuinely intimate and the attraction has legs. Her prickly exterior soon feels as necessary and callused as Bernice’s frivolity, and just as much not the only thing about her.

For one thing, her ingrained racism is an odd theme the books are commendably sticking with, and it had to come to the fore in this. Bernice acknowledges it offhand: “Perhaps she was turning into a racist. Or alienist. Whatever Roz was.” There is a knowingly awkward reference to Roz being “pure”, unlike the cosmetic-surgery addicts of her time. She is as proud of her direct lineage – however badly she feels she has let down her family – as certain other characters wearing different uniforms. When it comes to violence and killing, she hasn’t the remorse of Bernice, or even (you’d hope) an Adjudicator. Corruption and violence were everyday in Original Sin, which is why she and Chris left the Overcity, so why is she so ready to put a man’s eye out? (The man is a particularly cruel Nazi and if anyone had it coming... but even he has an inner moment of regret at torturing Bernice, admitting only to himself that she doesn’t deserve it.) Roz is one of the good guys, but she’s very far from perfect. Although to add even morecomplexity, in what is rapidly looking like moral ping-pong, Roz doesn’t know that people in the twentieth century can’t regrow eyes…

Chris, meanwhile, throws himself into the adventure, and he’s the only one thinking of it in those terms. (As Roz notes hilariously: “Cwej, of course, thinks that the ‘costumes’ are wonderful.”) He merrily breaks a Nazi’s neck because, apart from getting rid of him, it’ll impress a girl. All this provides interesting context to Roz and Bernice, but I’m beginning to worry that Chris won’t develop at all. Yes, he’s enjoyable, but how many times can we hit the “Loveable handsome idiot” note? Parkin isn’t terrible for doing the same thing as everyone else here, but somebody has to take the damn plunge some day. At any rate, the Doctor is the only one here that doesn’t directly murder anybody. Wolff is correct when he expresses concern about the so-called heroic people of the future, the ones on the “right” side of all this. (Speaking of which, this being war an utter atrocity happens in the book, and it’s the Allies that did it.) Ultimately the divisions of good and evil are what they are – the Doctor is unequivocal about who is in the right, successfully talking a Nazi into suicide by ticking off the failures of fascism – but Parkin doesn’t make it easy.

There is a careful, practiced quality to the book, which makes it very readable and often surprising. I had to admire the skill at dropping in something of relatively no import, like the Doctor’s disappointment at having his pockets emptied of dog biscuits – on the face of it, simply adding to his funny little ways – only to turn it into something plot-relevant later on. And without wishing to spoil the thing completely, the history-altering problem at the heart of Just War is not the devious chess game of doom you’re expecting, nor the unimaginable alien superweapon it’s built up as, but a significantly improved war machine created by a wrong thing said in front of the right person. The Doctor is someone who could change history with a well-chosen phrase, and it’s absolutely fair game to show the worst case scenario of that. Despite that power he is not the terrible, dark Doctor he’s built up as: sometimes he makes mistakes, hence Bernice’s harrowing run-in with Wolff. Isn’t that more interesting than just harping on about how nasty people are? (It’s here, in particular the book’s torture scenes, that I think of the novels that get this so wrong. It’s easy to pile on the violence and the misery and say “Look at this, isn’t it awful.” It’s interesting to pick all that apart and show the other side.)

Indeed, Parkin has time for light, whimsical touches. I loved the bit(s) about dog biscuits, and the observation that the Doctor doesn’t leave footprints in the sand, plus his seemingly magical reflection. I dislike mythologizing the Doctor (looking at you, New Who) but gently blurring the line between a sci-fi genius and a figure of unknowable oddity is all to the good, done well. He also pulls a few loveably silly faces – which Roz amusingly thinks of when the Doctor is mistaken for a criminal mastermind – and disguises himself as a nun at one point, and gets away with it. (I don’t want to say anyone is wrong for thinking the Doctor stays in the habit for the rest of the book, what with Parkin never explicitly removing it, but I think context makes it fairly clear he isn’t making with the Sister Act the whole time. It would certainly put the Russian Roulette scene in a new light.) There are several fourth-wall-prodding references to the Brigadier’s favourite anecdote, and the Doctor’s nom de plume literally being “Doctor Who” in a different language, which he has used on screen. It’s a heavy story about war and the things people to do survive and win it, but it’s not a grim or depressing book. Bernice gets tortured, sure. But she gets away, recovers and sees her friends again. It’s a succinct book, not morbidly dwelling on anything.

Perfect? Well, even after all that a part of me finds it tiresome to again point the finger of moral terribleness at the Doctor, however thoughtfully Parkin does it. And the book collects quite a few typos towards the end, with occasionally missing bits, a speech mark replaced with a semi-colon and in one whoops-hilarious moment, calling Chris “Christ”. I could understand this stuff in the early days of the range, but they’ve been at it years now and this sort of thing is preventable. But let’s face it, the buck doesn’t entirely stop with the author, and it makes as much sense to penalise the novel for that as for a dodgy front cover. Eye on the prize, then: Just Waris a straight-out-of-the-gate winner, doing a host of familiar things in new and interesting ways. The prose is lovely, the plot is extremely neat and most of the characters are more interesting for the experience. Pass the rubber stamp we reserve for special occasions.

9/10

Published on April 01, 2018 23:54

March 8, 2018

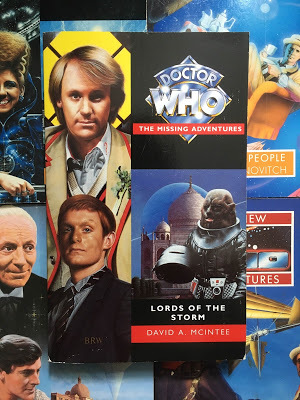

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #65 – Lords Of The Storm by David A. McIntee

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures#17Lords Of The StormBy David A. McIntee

And now for something… slightly different.

In his own words, David A. McIntee needed a change. Sanctuary was one of his most David A. Mcintee-ey books thus far: a pure historical with lots of action sequences, it indulged his main interests of historical detail and action… detail. It’s not exactly an upbeat book, although I think his suggestion here of a “grim ending” is a bit harsh. It ends on a note of hope, or at the very least some Schrödinger uncertainty – besides which, nobody reading the ongoing New Adventures would expect Bernice to suddenly get a long term boyfriend, so it can hardly be a surprise when Guy de Carnac doesn’t come with. (Let’s face it, the moment an unscheduled character says “I can’t wait to join the team!” they’re either going to change their mind or die. Godspeed, Lynda-with-a-Y.)

Onto his brave new novel, which the author describes as “more your old-fashioned space opera with shootouts, spaceships and lots of corridors,” and “not exactly mind-expanding”, but at least “more upbeat and fun than Sanctuary.” (Jeez, Dave. Who’s writing this review?) He’s fairly accurate on all counts, although his apparent ennui with historicals doesn’t prevent him dipping a toe in history. Hindu culture figures prominently in Lords Of The Storm, sufficiently to require a glossary at the back, which isn’t such a different context from Haiti in White Darkness or the UFO craze in First Frontier. But there is a pronounced difference between this and his other books so far.

Simply being a Missing Adventure makes Lords Of The Storm a less “heavy” book, as it doesn’t have to carry any major continuity (actually, hold that thought!) and it can come and go without frightening the horses. Also the story he has chosen plays more to Classic Who than I’ve come to expect with the Missing Adventures; aside from some impossible-to-realise visuals and at least one swearword, you could drop it into the show’s back catalogue without creating ripples. Whether it’s an especially brilliant Classic Who story is another matter, but either way there is a grateful audience for meat-and-potatoes Doctor Who.

We all like different things, but there are aspects of McIntee’s writing that make my teeth itch, and while they do feature in Lords Of The Storm they are largely restrained. The Prelude and the Prologue (and now you mention it, I do find it a bit annoying when books can’t just get on with it) are, for me, like that scene in Clockwork Orange with the eye-clamps. Establishing sentences ramble on with as much detail as possible, inviting the reader to pause the book and make a damn diagram of what’s going on and what it all looks like: “The faintly misty ribbon of stars that was draped across the infinite darkness like a fur stole slipped past to the left as Loxx switched over to the sublight drive and wheeled his ungainly gunship around in search of the source of the signal which had alerted his squadron.” Sometimes he’s like a kid in a candy store, only the candy is adjectives: “It was like looking out on a jagged sea, lit by the fiery glow of a sluggish river of molten rock…” In past novels he has favoured frequent paragraph breaks, which come in handy as he likes to spring new settings and characters on you, and the Prologue has this on all counts, jamming in the first hints of Hindu culture whilst simultaneously introducing disparate characters, often sticking to his old habit of telling us what their hair looks like, or stapling a descriptive signifier between lines of dialogue. (“Noonian grinned through his beard.”) It’s like eating several dinners at once. The jury is out on whether any of it is bad writing – although I’d be willing to argue the case against those adjectives – but it is largely contained to the first twenty-odd pages, surely a conscious decision.

What follows is a surprisingly measured, almost sedately paced plot that has several things to do – what’s going on on Raghi, what are the Sontarans up to on Agni – and follows them up at an efficient clip. Which is a monumentally boring way of saying the book moves through its plot without jumping all over the bloody place, or lingering too obsessively on the details, which I found rather refreshing. This is its Classic Who vibe: none of it’s in a terrible hurry but it’s not exactly boring either. After the uphill hike of the Prologue, I found it an easy read.

Equally Classic (if not, I would argue, classic) is the emphasis on plot, with characterisation as a bonus. No one is terribly written, but there’s nothing too memorable about the people here. Nur is a compelling new friend for the Doctor: a young woman treated like royalty who would much rather not be, her piloting skills are neatly underlined by a family tragedy, and she has a personal stake in the spread of disease on her home-world. When it comes to confronting her father about his involvement, what should be a pretty heated change in the status quo is entirely matter of fact; the consequences wait politely for the end of the book. The head of a local hospital, Jahangir, finds himself colluding with Sontarans and feels a palpable guilt over it, which makes him far more compelling than the average cloth-eyed collaborator. It later transpires he was hypnotised the whole time, which is less interesting than being coerced, and his subsequent character arc of revenge and sacrifice could not be more obvious. The climax of this goes strangely unseen, as does (or almost) the oh-yeah-I-forgot death of a programmer Turlough briefly meets. Several moments are weirdly nipped in the bud, like Jahangir freeing his hypnotised comrades from Sontaran control, which goes from “I might do this” to “Phew, finished” in close succession. The book just isn’t that interested in dwelling on things, which might be another conscious effort from McIntee. Despite making a big thing of Hindu castes and their parallels with the Sontarans, which is relevant to their plan, Lordswill not teach you anything major about Hindu people; it jumps through some fairly obvious hoops about karma and the wheel of life and then pretty much calls it a day. (Still, maybe I am so used to overkill from his previous books that I inadvertently miss it here! In which case I am impossible to please…)

The Sontarans, at least, are treated as thinking people, albeit distinctly Sontaran ones who are obsessed with war and can hardly tell humans apart. One of my favourite observations was that countless human deaths don’t really matter, because they probably reproduce as quickly and efficiently as the Sontarans do. (I.e., cloning.) That utter disinterest mixed with rationalisation gives them a thoughtful and alien approach. There are clearly differentiated ranks and castes of Sontarans, which explains why the clone race looks different every time they’re on screen. McIntee amusingly highlights what some think of others, not shying away from their general lack of subtlety but also crediting some of them with considerable intelligence. He is, I think, less successful in physically telling them apart: he makes an admirable effort each time but it always sounds to me like variations on “a brown potato”. Which I suppose they are, but it’s still difficult to know which one he means.

The Rutans inevitably feature. While this isn’t a given in Sontaran stories, although they do often talk about their gelatinous nemesis, the book makes it clear that these events form a prequel to Shakedown. And thar be Rutans. Or Rutan, as McIntee insists on pluralising them. (It’s worth it for the glossary. “Rutan: the plural of Rutan. See below. Rutan: the singular of Rutan. See above.”) Just as much consideration goes into them, with a similarly chilling disinterest in their enemies and, in sequences told from their point of view, an unnervingly liquid view of time. It’s only disappointing that they are kept back until the end of the book. A gestalt mind – which has always been a canny parallel of the general sameness of Sontarans – the Doctor makes light of them and calls one of them “Fred”, which is then picked up into the plural “Freds”. Best of all is a Rutan working undercover, who is so entrenched that he (they) gets his (their) tenses mixed up: “There would be time enough to resume a normal life later, if he survived. If we survive, he reminded himself – themselves – more forcefully.”

Said Rutan spy forms the main link between Shakedown and Lords Of The Storm, and I often wondered if it was even needed. Could the villain in Terrance Dicks’s book have got by without this specific back-story? But perhaps I’m just grouchy because our knowing the character’s name makes it a very long wait for what otherwise would have been a decent twist. I half expected a lot of nudges towards the fact that you may have already seen or read Shakedown, but it’s written straight, and offers surprisingly little to tip the wink. When the reveal comes it’s still pretty exciting, and it’s a very neat note to end on, give or take the corny final sentence.

Fortunately there is an entire novel besides the link to Shakedown, and indeed McIntee came up with this before Shakedown even appeared on video. The plot could easily survive without a link to anything else: the Sontarans just want to lure the Rutan into a trap and then wipe a lot of them out, and the caste system on Raghi makes it easier to trick them into thinking this is a planet full of Sontarans. (I did wonder, given how quickly Sontarans “reproduce” and how little they regard their “offspring”, including as potential target practice, whether it would have been easier just to breed a bunch of Sontarans and leave them there. It wouldn’t be cricket, I suppose, but weighed against the number of Rutan killed? I think they’d consider it.) There isn’t a great deal of mystery to be had, hence the fairly patient meting out of information as opposed to a series of shocking twists and turns. The Doctor doesn’t twig that the Sontarans are even involved until almost the halfway point, and then he just nods and gets on with it. Similarly, the disease raging through Raghi is an obvious consequence of their plan, and it won’t be a problem for long. The various interpersonal issues – Nur losing faith in her father, and struggling to forgive a hypnotised collaborator who is also her arranged spouse – get swept away as neatly as possible. McIntee’s description of Lords as “not exactly mind-expanding” is certainly accurate, but I wish it hadn’t been his mission statement.

The Doctor and Turlough are in an interesting place, i.e. the only Tegan-less existence they’ve ever known, but despite a few references (and a poignantly half-hearted “Brave heart”) it’s pretty much an ordinary day out for them. The Doctor is proactive and useful, which for Five is something of a relief. I liked the sympathetic description of his having “that slightly saddened air of one who’s seen too much suffering, regardless of his obvious youth.” Turlough is charmingly close to amoral in this, noting that “the choice between possible hurt to others and certain hurt to himself was an easy one to make.” There’s a degree of overkill in so repeatedly telling us how dimly he views humankind and how quickly he’d leave them to rot, and he skirts a little too tenuously on the edges of the story. But there are also enough references to his regal home life to suggest a subtle decline towards the next televised story. A reference to Kamelion does much the same thing, whilst also eyebrow-raisingly reminding me that I tend to forget he exists. (For the second time in the Missing Adventures, I find it odd that the book range doesn’t do more to give this technologically challenged character some fresh air. After all, they’re his only hope.)

I often wondered if this was my Proverbial Good David A. McIntee Book, but that’s disingenuous. I haven’t hated anything he’s written, I just tend to remember the irritating scaffolding surrounding the good bits. And there are always good bits, though they tend to be one evocative action scene out of many: the crashing ship in White Darkness, a plane falling out of the sky in First Frontier, a surprise attack in Sanctuary. I’m not sure I could pick a comparable highlight here, although the Prologue nearly throws its back out in the attempt. Lords Of The Storm is a more streamlined effort, often literally, as McIntee proves he’s entirely capable of describing things wittily and concisely: “The planet was not alone in its orbit; a necklace of sparkling jewellery encircled it and its tiny moon.” / “It was as if they were flying through a universe of smoke, ready to leap at the source and fan the flames.” / “There was an uneasy silence, whose gradually increasing length started the sergeant visualizing his opponent in the duelling pit.” Lords does not have a cast of thousands or a need to change channels all the time, so it’s an easier read than some of his other books. I’m not sure I would call it “upbeat and fun” – a description largely based on his last book not being those things – but it’s steadily enjoyable.

All the same, the pervading sense of casualness doesn’t add up to much. The Doctor and Turlough aren’t wiser for having had this experience, and neither am I; even it its best I couldn’t see myself reading it a second time. It’s a personal preference, and I know it’s slightly unfair when you’re reading not just Doctor Who books but era one-shots, but I just don’t have a lot of room on my shelf for stories that are happy just to get on with it and go home.

6/10

Next up: 66–70, starting with Just War by Lance Parkin...

Published on March 08, 2018 23:51

March 7, 2018

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #64 – Shakedown by Terrance Dicks

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#45ShakedownBy Terrance Dicks

If you think the New Adventures were an odd avenue for Doctor Who, you should see the other guy. Armed with assorted talent from the show but no license, fan videos were a (relatively) popular way to get your fix in the ’90s, provided you could stomach budgets that made… well, Doctor Who look lavish.

I was a timid young fan and couldn’t wrap my head around books with new companions, let alone unlicensed videos about some random people who may or may not look like the Doctor (or worse, no one that did), so I missed the boat. Most of the stuff I know now is from Dylan Rees’s excellent non-fiction book, Downtime. But I’d still heard of Shakedown: one of the more successful efforts, it was a self-contained thriller with Sontarans attacking humans on a spaceship. They shot it on a real battleship and the cast would all be familiar to the target audience. Terrance Dicks wrote it; you might remember him from Pretty Much All Of Doctor Who.

It was apparently Virgin’s idea to novelise it as a New Adventure, and in his introduction Dicks admits this is an odd choice. Shakedown featured no Doctor Who characters besides Sontarans and Rutans, and it’s 55 minutes long – a quick read even by his standards. To compensate the book begins before the video, novelises it, then carries on afterwards. Think of it as the most lavishly expanded Target book ever written.

In case you were optimistic, Dicks’s last book was Blood Harvest. A shoddy mix of gangster fare and unnecessary State Of Decay sequel, it felt rushed and it lacked the thrills of his earlier Exodus. And now I’ve seen Shakedown, which pretty well achieves its aims – the monsters look good, it doesn’t outstay its welcome, I liked the music – but is, shall we say, generally one take away from its best? Shakedown has Michael Wisher competing with a (comedy?) Sontaran for the hammiest turn, and it includes some spectacularly bad “romantic” dialogue between the two varyingly wooden leads. As with most of the ’90s fan videos, you probably had to be there. Even then I’ll bet it didn’t scream “This would make a really good book!”

Sure enough, the best bits are not taken from the video. Dicks throws himself into What The New Adventures Characters Did, or as it’s actually called, Part One: Beginnings. (Yeah, the subtitle’s not great.) We need a reason for the Doctor and co. to get involved, a reason for them to miss about 55 minutes of the action and then a reason they’ll be needed again afterwards. You get most of this just by splitting them up to hunt the Rutan who caused all the trouble in the video, and simultaneously find out what – besides the obvious – he’s done to annoy the Sontarans. Dicks adds a lot of colour to these side quests.

(Before I get into that, splitting up the characters used to be an irritating excuse to juggle too many of them, but it has become de rigueur since Chris and Roz joined. It feels right to have a police investigation with two ex-Adjudicators on staff, and it suits the Doctor’s rampant game playing to put it on several fronts. With novels like Toy Soldiers, Head Games and this, they’re sort of reclaiming that trope.)

We know the Doctor previously met Kurt (the erstwhile Shakedown hero) thanks to some cheeky references to a mysterious “dentist”, among other misremembered monikers. (Sue this!) The encounter is a slightly bigger deal now: the Doctor is mid-adventure (generally how I like it) on a planet about to be invaded by Sontarans, only he’s already trying to fend off some human colonists as his sympathies lie with the natives. Not a problem, now he just has two oppressors to get rid of. He and Kurt, the latter fleeing a compromised smuggling deal, turn things sour for the Sontarans and Kurt vows to pay him back for saving his life. The whole vignette fits into a pacey prologue and it makes for a memorable start, with the Doctor wholeheartedly toppling regimes just like the old days – although he seems a little too at ease teaching the natives to kill their oppressors, just as later on he has no problem at all offing Sontarans. (His characterisation is mostly all right, apart from wholesale murders and sounding oddly like the First Doctor at times.) The Jekkari, who only communicate by tapping, are an interesting bunch.

It neatly establishes Kurt’s knowledge of Sontarans, but it also creates a few hurdles. Kurt barely remembered the Doctor in the video (which was mighty convenient, of course), and there’s no sign that he had previously met the two Sontarans who would menace him later, as he does here. Dicks gets around such discrepancies – which to be clear, didn’t exist until the book! – but he ain’t exactly subtle. He has Kurt deliberately fudge his facts about the Doctor, essentially because uh, reasons? And on Commander Steg not recognising him, brace yourself: “Lucky I got rid of that beard!” Later when Steg miraculously survives his screen death to wreak some Act III revenge, we get a whole bracketed-off paragraph explaining Sontaran death comas. Truly seamless.