Gareth Rafferty's Blog, page 13

January 24, 2020

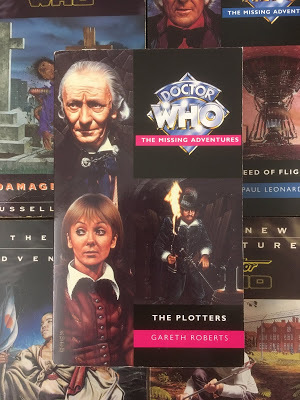

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #89 – The Plotters by Gareth Roberts

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures#28The PlottersBy Gareth Roberts

If you were new to Doctor Who you might find it odd that there are so few stories where the characters get embroiled in history. It seems like an obvious win for a time travel show, and to be fair there are many great examples of this in the early years, with characters trying to keep history on course while struggling to escape from it. But Daleks and Cybermen get you more Radio Times covers, I guess, so after 1967 the historicals sadly died off; all of a sudden the only way to see history was if aliens were trying to blow it up. (Not including Black Orchid, where you only wished aliens would blow it up.)

The novels have mostly followed suit, stapling reassuring sci-fi bits to any errant historical settings with two exceptions: Sanctuary, David A. McIntee’s grim book about the Spanish Inquisition, and now The Plotters by Gareth Roberts. In some ways this is the better historical. No doubt McIntee did more detailed research (Roberts’s book opens with an acknowledgement that The Plotters isn’t very accurate), but this one’s set in the Hartnell era, where you were most likely to find trips to the past. Roberts knows exactly how best to use these characters in that context, with the Doctor, Vicki, Ian and Barbara assuming more or less parallel roles to those in The Crusade. They slide back into the swing of things with such ease that you could easily imagine this being made for television.

Arriving in 1605, the Doctor dismisses Barbara’s obvious enthusiasm for this period of history but allows her and Ian to take in the sights while he and Vicki loiter in the TARDIS. This is a lie, of course: he knows just how close they are to a juicy bit of history and he intends to find a good seat to gawk from. His deception leads to some pretty unpleasant business for everyone else, and it’s absolutely in keeping for Hartnell’s Doctor to lap up every minute of it regardless. He’s a wily, wilful, crafty old sod in this, as comfortable leading Ian and Barbara astray as he is playing word-games with the devious Robert Cecil. He never exactly apologises to his friends for the consequences of his fib – more on those shortly – and none of it seems to upset him at all. He practically cries with laughter at King James’s oblivious line on the back cover, “If anyone tries to interrupt the opening of Parliament … there’ll be fireworks!”, and later he works with one of the conspirators because doing that will be better for history than not. You could put all of this down to Roberts indulging Hartnell’s gift for mischief, and that’d be fair, but I like to think it deliberately underlines how the Doctor is unlike his companions. He can often be a serious presence in historical stories, reminding the others of the implacability of time, but at this stage Ian and Barbara have learnt the lessons, so he seems almost free of obligation. He has faith that time will sort itself out and if he has to give things a little nudge along the way, nudge them he will.

Barbara, possibly winning the “least fun weekend in 1605” award here, goes with Ian to a tavern and promptly gets embroiled in the work of Guy Fawkes and Robert Catesby. She’s kidnapped, assaulted and threatened several times with execution, only escaping because she tells Fawkes a worrying amount of the truth about where she comes from and what she knows about him. (You can guess what she leaves out.) Fawkes is dead set on his goal, but he has no wish to harm her; he helps her escape from the more dangerous Catesby. Barbara observes several times that Fawkes is not such a bad man, or not universally so, and she’s absolutely tortured by the knowledge of what will happen to him. She still goes out of her way to ensure that it will. If The Plotters had somehow been made back in the ’60s, this would have made a bleak but satisfying end to Barbara’s learning curve in The Aztecs.

Good as all of that is, it would be fair to say that Barbara essentially just gets captured and escapes in this, which makes it even more unimpressive that Ian’s entire role in The Plotters is to dash about looking for her. Despite often inhabiting the more heroic role in Doctor Who, or maybe because he does, Ian fades into the background of the plot. (And later, The Plot.) He meets a pair of cheerful shoemaking rogues, Firking and Hodge, who offer shelter and haphazard support when he needs rescuing from Catesby and co. Roberts seemingly can’t wait to steer Ian back towards these two, as it allows more opportunity for amusement. I love Ian, but he’s at his funniest when the Doctor is making a faux pas, not so much when Barbara’s in danger.

Firking and Hodge provide a few straightforward laughs, but there’s a better comedy double act in the bickering Haldann and Otley: working to transcribe the King James Bible, they constantly snipe at each other but quietly agree it’s best to leave out some of the boring bits, because “Well, would you like to be stuck on the begats for week after week?” The Doctor’s apparent interest in 1605 is the transcription (at first), and he ingratiates himself not just into the King’s court, but between these equally cantankerous old goats. I found myself looking forward to these bits and gleefully imagining them on telly.

It’s debateable whether this version of King James would have made the cut. It’s remarkably similar to Alan Cumming’s take in the recent series, all lascivious looks and lusty Scots wit. But Roberts doesn’t so much acknowledge the King’s sexuality here as build a rocket out of it: he subverts the trope of the lusted-after companion by disguising Vicki as the Doctor’s ward, then making her the object of his affections precisely for that reason. It’s a particularly crafty farce that all Vicki has to do to end the King’s advances is lose the disguise, which is the one thing she can’t do. Grim as the consequences of her discovery would be, Roberts has endless fun with the obsessed King, whether patting his knee hopefully and sending knowing looks or throwing a drunken sulk because he can’t find him. There are some near misses: “‘I promise if you let the King have his way you will get a lovely surprise!’ ‘Not half as lovely as the surprise you’d get,’ said Vicki.”

A character like King James is a gift when you can write prose like Gareth Roberts. “With a snap of his fingers he summoned a boy to refill his goblet (boy-summoning was a choice pastime of his).” / “He was constantly searching for these little reminders of his specialness. He remembered his father warning him that the first sign of serious levels of unrest in one’s subjects was everybody’s dinner looking the same. Poor Dad. Blown to bits at Bannockburn.” / “‘Something – oh, something awfulhas happened!’ ‘Ugh. How awful?’ ‘Veryawful, Your Majesty.’ James remained to be convinced. ‘On a riding scale, if one is a stolen pie from the kitchens and ten is revolution in the streets, how awful?’ The Chamberlain hesitated. ‘Oh, eight, Your Majesty.’ ‘Oh, doom.’” Even the prose around him is fun. Describing the busybodying Chamberlain: “Patches of pink bloomed on his cheeks, making plump mulberries of them.” And the Chamberlain on food prep: “He’d forgotten to remind the cooks of James’s innate loathing of meringues.” There’s just gobs of this stuff, all delicious.

Where the TARDIS team are concerned, the wit is tinged with characterful insight. Barbara on the TARDIS’s failure to hit the 1960s: “Back to the Ship and pull the handle on the fruit machine again.” And adorably, “We’re only about three hundred and sixty years out. That’s quite good for the Doctor, all told.” Vicki is particularly, almost conspicuously unamused by the Doctor in this – probably spurred on King James’s affections – observing “He wore his own Edwardian outfit, which [she] didn’t dare point out was as anachronistic as any plastic mac.” More significantly, “[she] had noticed before how he faked symptoms of ill health when bringing bad news or trying to conceal a mistake.” At one point she’s so tired of lugging books for Haldann and Otley, she contemplates kicking him in the shins. The Doctor meanwhile snidely congratulates himself that “This excursion was turning out quite satisfactory, particularly without those schoolteacher people to distract him,” and on meeting the Chamberlain “found his constant gesticulations irritating, and quelled a desire to reach out and slap him.” Significantly (and dangerously) he gives Cecil one in the eye when he says “‘The ordering in the Alexandrian section is quite gone to plot – I mean to say, pot.’ Feeling rather puffed up and pleased with himself for that one he strode away round the corner.”

It’s not all playful and fun, of course, what with Barbara’s mistreatment and her inner torment over the fate of Fawkes. Also some marvellous, earnest little nuggets like this jumped off the page: “In this age it was still possible to see the stars, and as he trudged up the road Ian stopped more than once to look up and wonder which of them he had visited.” There’s a grim interlude where Ian and Barbara witness a bear being exhibited for cruel London punters, and there’s a surprising and horrifying murder late in the book (which thankfully Barbara misses), but nonetheless the plot errs on the side of fanciful. (Hence Roberts’s acknowledgement/warning at the start.) The Plotters offers a sinister linking presence to the machinations of Cecil and the delusions of Catesby. It’s never less than fun to read, particularly as the Doctor surprisingly disarms Cecil by agreeing to help him, then hoodwinks a mastermind by sheer dumb luck. But some of the machinations do get a bit silly, particularly a male character’s prolonged successful disguise as a serving wench, which seems more like Blackadder than Doctor Who. Towards the end of the book there’s an almost unruly number of scenes with characters held captive in dank little rooms; I had trouble remembering who was where, held at sword-point by whom.

I’ve definitely got some quibbles. The Plotters is a smidge too long at nearly 300 pages, some of it being the aforementioned game of “Whose cellar is it anyway?” Also it’s so intent on giving the Doctor a whale of a time that Ian and Barbara, and very nearly Vicki don’t get a great deal to do. But I’m so enamoured with the prose that I can just about write this off as era-appropriate. Historical stories could go on a bit just as much as the sci-fi epics, and four characters is always a lot to balance in terms of plot. (The Crusade, which I adore mainly as a novelisation, ultimately runs out of material for the Doctor and Vicki.) Where The Plotters isn’t perfect, it still feels like something the Hartnell era was foolish to let go. It’s just great Doctor Who.

8/10

Published on January 24, 2020 05:08

January 23, 2020

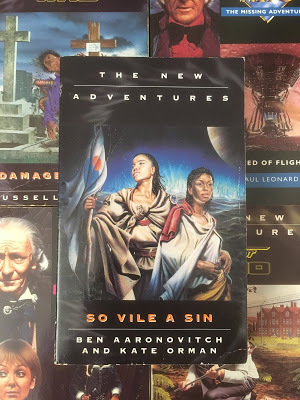

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #88 – So Vile A Sin by Ben Aaronovitch and Kate Orman

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#56So Vile A SinBy Ben Aaronovitch and Kate Orman

I’m not sure this warrants a spoiler warning since the book is 20+ years old and the major event in it is probably referenced in half a dozen other books. But you might have made it this far and not know, and I don’t want to be That Guy Who Ruined It For You, so: spoilers ahead.

Brace yourselves, this one’s important. So Vile A Sin is the culmination of the Psi-Powers arc, the last New Adventure to feature Roz, and it’s by Ben “Yes I wrote The Also People, I do other things, you know” Aaronovitch – added up that’s more than enough to hoik up the price on eBay. But then there was a mix up with a malfunctioning hard drive and a timewarp and it ended up being a) delayed, b) co-written by the equally beloved Kate Orman and c) the last New Adventure to feature the Doctor, his book rights having swanned off to the BBC. The accumulated geek points mean it is now d) eBay gold dust, unfortunately for prospective readers.

This wasn’t supposed to be the end of the New Adventures (feat. Dr. Who), but it is how they stopped: with a huge plot spoiler arriving half a dozen books too late. I can only imagine the weirdness of reading all the subsequent fallout before the actual event, or the even bigger weirdness of sitting down to So Vile A Sin afterwards and trying to look the least bit surprised.

Thankfully I’m able to read it in order, though it’s now become so infamous that avoiding the main spoiler was impossible. So Vile A Sin seems to anticipate this, strangely, announcing the major event on Page 1. Was that always the plan, or did they rearrange the flow of the story around the fact that most readers would already know? Either way the book is like: Roz dies. *mic drop*

Page 2 is her funeral. Much about this is unexpected, from taking place so early in the book to the blazing sunshine that accompanies it; the Doctor seems to be coping with disturbing ease right up to his heart attack. It’s a well-judged gut punch of an opening. I tried to imagine reading this totally unspoiled, and... you’d assume it was a wheeze, wouldn’t you? Doctor Who certainly isn’t above a dramatic fake out. The TARDIS “dies” every other Wednesday.

The ensuing story hops around in space and time and concerns different timelines and possible futures. The Doctor, in particular, is besieged by alternative lives and an actual double for some of it. The cumulative effect is the tantalising feeling that, all joking aside, there are plenty of escape clauses to choose from and we just wouldn’t do that to you. They dangle the possibilities quite openly here and there, like the Doctor seeing various futures and saying to Roz “You’re alive with me in four of them.” And elsewhere a young Forrester contemplates: “The rumour mill had it that little Thandiwe’s Aunty Roz hadn’t died, that this was a cover story for something far more interesting.” There’s even a sweet bit at the end that hints, maybe, somehow…? Hmm.

The book’s tone also seems to belie such a cruel twist of fate. I wonder if it’s indelicate to guess which author made which contribution, so I’ll just say that more often than not the book feels like Kate Orman – which here means that despite a lot of horrible things happening, it’s somehow a rather light and spirited read. A weight of expectation rests on it all, certainly, but at the same time it seems more than happy to zip away and think about something else instead. There’s a jolly scene where Chris meets some of Roz’s family in her multiple-museum-sized home, which includes an adorably Also People-ish bit with sentient airplanes. (Ben? Or is that too obvious?) There’s a fun bit where some of the AIs from SLEEPY unexpectedly gain physical form and have a rendez-vous. (Kate? I bet I’m getting this totally wrong.) One seemingly random diversion has two bit players meeting an alternate Doctor in his strange little home, and just being there, soaking up the odd atmosphere before he vanishes. The damn book is the first one to tell you that Roz dies, but there simply doesn’t seem to be time for something that big and awful to actually happen. (It employs a similar zippiness with the Brotherhood plot, with the signal from Damaged Goods being wrapped up rather succinctly early on. You begin to suspect that their plan, like Roz’s death, has been exaggerated.)

I spent the whole thing waiting for some catastrophic conflagration to come along and epically take Roz away, but of course, that’s not always how death rolls. One day she’s in a war zone, things don’t go her way and that’s it. The event itself is not transcribed.

The fight against the Brotherhood takes a bit of a left turn when Roz’s sister, Leabie, decides to go for it and take control of the Earth Empire. It’s worth noting that the Empire is in tatters and propped up by the Brotherhood, who have their own agenda, but it still feels like a coup and Roz might be wrong to participate in it. The epilogue doesn’t hem and haw too much over this, saying everything’s in good hands with Leabie, but it still didn’t quite sit right with me. But then, so what? There’s something brisk and unexpected about a companion taking such a dangerous, morally uncertain decision, especially as their last one. Roz’s final conversation with the Doctor is a rebuke, telling him that he’s not in charge and she should be able to go off and make her own decisions; that she isn’t like every other companion he’s had. “When all thosechildren you call your companions have their fits of moral anguish and cover up their eyes because of the things you have to do, just remember who it is that stands by you. Who does the necessary even when the necessary costs … You owe me. So you can threaten Bernice and Dorothée, you can show your human side for the cameras, but I know. That history kills people and sometimes even you can’t save them. So you owe me this, for my family, for the children of the angry man and for the ones that died in the slave ships and mines and all the others you couldn’t save at the time.” All the Doctor can offer in response, occasionally throughout the book, is a defeated entreaty not to get involved. Because undoubtedly he knows she will and that it’ll be over soon.

The Doctor’s powerlessness crops up throughout, from not knowing which version of himself is a duplicate to being unable to save Roz. There are literally other version of him that do have a plan and, it is strongly suggested, “our” one that finds himself at the funeral is not among them. He’s crushed. But in that curious way that I’m tempted to lay at Kate Orman’s door, he also has a lot of frivolous and fun little moments, like temporarily finding himself as a (terrible) ship’s cook or, after assassinating the current Empress – a thing that happens, incidentally! – he argues with and flippantly denies the authority of his trial. So Vile A Sin is acutely aware of the Doctor’s rep as a master game player, and wrong-foots it in a way that makes him seem a little more three-dimensional. He even admits to the Brotherhood that “‘You think I’ve been chasing you. Trying to expose you. But our paths have crossed at random. I’ve never sought you out.’ His shoulders fell. ‘We didn’t have to be enemies.’” Which, in all fairness, might say more about the Psi-Powers arc than it means to. I don’t think I’m alone in being unimpressed with the Brotherhood, and while it is satisfying to tie together their exploits in various earlier novels, I won’t miss them.

The book has an unusual way of dealing with these momentous events – Roz’s imminent death, the Brotherhood’s ultimate plan – in that it’s so flighty that they don’t feel momentous at first. Some of this I’m sure is an insidiously clever way to manage the reader’s expectations. It also (brilliantly, I think) reminds you that even grief and death are shrouded in life, upturns and random good bits: you can’t have one without the other, hence the odd feeling that you’re reading a really colourful and fun book about something awful happening. But then there’s the elephant in the room, somehow tooting “This isn’t how it was supposed to be” with its trunk. So Vile A Sin, as we’ve read it, is a recreation of what it might have been. There’s no point getting caught up in the ways Ben Aaronovitch would have handled all of this on his own, of course, because that book doesn’t exist for comparison, but the flighty, almost frantic pace of the thing – the jumps in time, the characters just plain conveniently turning up when they’re needed – do point to a kind of “Oh crumbs, how do I stick this together?” Which isn’t hard to believe.

It never feels rushed in the way a lot of other Virgin books do, i.e. changing tracks every half a page to spuriously try and get a bit of momentum going. But it nonetheless gives the impression that it is summarising, however brilliantly, another book. (I’m just observing, I really don’t mind. This is the only way we were going to get So Vile A Sin, so three cheers for Kate Orman for completing such an uphill brief. It’s not that easy – I recently read Kurt Vonnegut’s Timequake, which does a similar thing with his own abandoned story idea. I spent the whole thing wanting to read the original.)

You know what? I’ll need to read it again to get all of the nuances out of it. There are tons of characters who for various reasons (blah blah, see above) don’t stand out as much as they might. I think that’s excusable. But maybe that’s just me galloping through the book, perpetually surprised I wasn’t reading something turgidly weighty. Roz’s life, her contradictions and her secrets are celebrated here, going right back to Original Sin, and there’s nothing token about her death. (Which is a relief as, according to Bernice Summerfield: The Inside Story, there were plans to kill her in her first book!) We’re given plenty of nudges and winks that all might not be what it appears, and yet some sense of closure is somehow snuck between them. For what you might think of as a rescue mission or a juggling act by Kate Orman, that is a real achievement.

With its multifaceted Doctor and worlds of possibility, it also serendipitously embraces its place as a finale, ending (if you like) the New Adventures on a sad note, but with love. The Doctor could be anything and his companions can make their own choices. It’s not a bad legacy.

8/10

Published on January 23, 2020 22:47

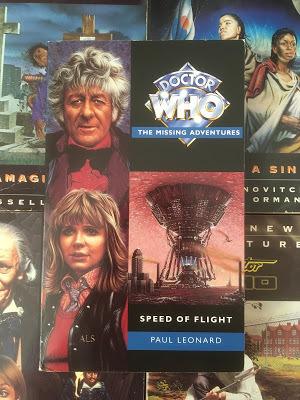

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #87 – Speed Of Flight by Paul Leonard

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures#27Speed Of FlightBy Paul Leonard

Oh good, it’s Paul Leonard. A bit of a sleeper hit when it comes to Virgin’s Whoauthors, Leonard has now written three quietly impressive books. Venusian Lullaby is the standard bearer for (very) alien life; Dancing The Code is a characterful examination of violence in the Third Doctor era; and Toy Soldiershas an evocative plot steeped in atmosphere and imagery. Now we have Speed Of Flight, another Lullaby-ish deep dive into offworld life. All aboard.

He sets the tone right away with a prologue following Xa, a simple-minded labourer on an expedition he doesn’t understand. The language is all a bit vague, much like Xa, describing suns, skies and lands in a way I can’t quite pin down. And Xa wants to fight – he must fight, if he wants to be “promoted”. The life cycle on this planet demands a mortal battle and to win means evolving wings and changing in other ways.

All of which is sort of interesting, except we’re stuck in Xa’s head and he just goes on and on about fighting while not understanding any of what’s happening around him. As a first impression, it’s frustrating. Not to worry though, since the rest of the book is (mostly) about other characters. But that sense of somewhat imaginative vagueness never goes away regardless of the character we’re following, and I struggled through more or less every page.

It’s hard to pin down the problem here, as there are a lot of complex ideas at work. Nooma – only named in the blurb unless I'm mistaken? – is an unusual setting with its seemingly artificial sky and low gravity. (Just typing “artificial sky” recalls The Also People, and look at the bountiful rewards in that.) The life cycle of its people has obviously been thought through in much the same way as “remembering” in Venusian Lullaby. The villain of the piece, Epreto, isn’t a bad guy per se; he just wants to break free from the strangely rigid evolution of his species, and while he’s at it the world around him, which seems to be falling apart. I’m all for moral ambiguity and a villain with only “good” motivations is a welcome change. There are even ideas to spare, such as the Dead, a series of pseudo-mechanical recreations of deceased people, and there are plenty of neat visuals such as the ubiquitous steamships.

For some reason though, none of this takes off. The world isn’t heavily explored: there is mention of temples on the sky but we hardly see them, nor most of the people who live here; roughly a quarter of the book seems to take place in one character’s house; the lack of gravity never seems important (and is surely at odds with the overall obsession with flight), and there are assorted characters of different sub-species with varying job titles, such as “confessor”, who just refuse to crystallise into relatable, breathing people. I never really understood what the Dead were all about and, as much as Leonard has applied his characteristic flair to the born>fight>evolve process on Nooma, the plot never progresses much beyond it. Also characters yakking on about wanting to fight is really not that interesting to me.

As it takes place after Dancing The Code (with references to prove it), you’re probably expecting more character work to bed in Jo’s imminent departure. That last book ended on a note of defiance for Jo, after all: a fork in the road between her and the Doctor where she was the one offering to help. Unfortunately, Speed Of Flight isn’t all that interested. Hoping to visit Karfel (so we can tick off that all important Timelash Easter Egg) the Doctor picks up Jo and Mike Yates, who have been sent on a prank blind date. Jo promptly meets the Dead and spends most of the novel not feeling like herself. (Towards the end there is a nod towards her desire to move on, but that’s all it is.) Mike’s clumsy arrival gets a sympathetic character killed, and he then spends a portion of the novel dead himself. (An incident at the end hints towards his troubled loyalty in later stories, but it’s a bit of a random link.) The Doctor figures out how this planet’s life cycle began as well as Epreto’s plan, and is curiously unsympathetic.

While his mannerisms are spot on as ever – including a delightful bit where he claims “Eeny, Meany, Miny, Mo” is a Venusian nursery rhyme – the Doctor’s attitude leaves something to be desired. It ought to be significant that he spends most of the novel away from Jo, but that feels incidental, as her out-of-it mind-set means she isn’t really learning and growing from her experiences. Mike Yates was mostly a nothing character on screen, and outside of The Eye Of The Giant (where he displayed some military efficiency for once), he’s the same in print. The Doctor is unfazed by his arrival and not especially knocked by the possibility of his death. It’s an odd three-man unit (ahem) to base your book around.

Speed Of Flight has some of the mechanics that made Leonard’s earlier books great, but it gets hung up on some details and doesn’t delve into others. It’s a book desperately lacking in colour and feeling, soldiering on to service an ultimately simple plot and finding no other rewards. It’s not a book I hate, but it is thankless work. I wish he’d filled this particular gap with Dancing The Code and then moved on.

4/10

Published on January 23, 2020 09:04

January 22, 2020

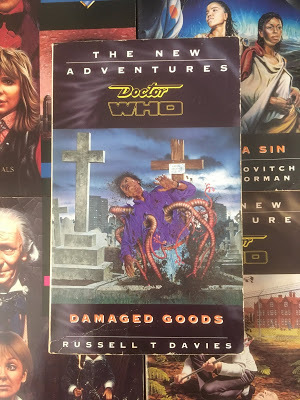

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #86 – Damaged Goods by Russell T Davies

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#55Damaged GoodsBy Russell T Davies

I’ve said this before, but as Gary Russell said to the continuity reference, what’s one more? The New Adventures have (or at least, to me they had) a certain stigma. They’re New. They’re grown up. There’s a significant chance they’re not for you, faint hearted young Whofan, so move on. (Which I did.)

And that’s bollocks. The majority of them are just Doctor Who books, some good and some bad, with more inclination towards swearwords and sex than you’d expect in Doctor Who. (It’s still not that much.) Whirling through these books, I occasionally wonder what all the fuss was about – where all the big, scary adultness went.

Well, it’s here, isn’t it? Damaged Goods practically earns the New Adventures reputation all in one go. It isn’t the first NA to push these buttons (messrs Aaronovitch and Cartmel have prior claim) but boy, is it the most. If you want to be literal about it, this book has the largest number of sexual references and perhaps the greatest quantity of violence I’ve seen in a Who book. It is bonzo-dog-doo-dah dark, and by the end it’s bleak enough that Andrew Cartmel might put it down for a moment and stare brokenly out of a window. (Fair’s fair: I think Cartmel trumps this one for drugs references in Warlock. And, uh, dog-related deaths in Warchild.)

It’s difficult to look at it unspoiled, as we’re all sitting on the other side of Russell T Davies’s time making actual watch-it-on-the-telly Doctor Who, so we’ve all got a pretty good idea what he likes about it. A fair amount of that material is seeded here. We have a poor estate in London, a family of Tylers, a devastating Christmas, more focus on the human lives going on while the Doctor machinates, and a great deal of guilt for the devastation he leaves in his wake. As a bonus, reading Damaged Goods makes you realise just how much he toned it down for TV. Damn, Russell!

Okay, let’s hunker down: the book begins with a flashback, which is also a flash-forward. Little Bev Tyler follows her mum out into a cold Christmas night on an unhappy errand, when she catches sight of a strange little man in a battered hat. Years later she meets him, and he has no idea who Bev is. (Davies delighted in telling Toby Hadoke that New Earth invented timey-wimey before Steven Moffat did, and he manages it even earlier here. But Steven arguably snuck in before him with Continuity Errors. Then again, they both nicked it from Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey.) I loved the immediacy of this, Bev picking the Doctor up right away on their strange meeting – it’s the kind of secret that usually festers away inside a character, and you wish they’d just bloody talk to each other instead. Plenty of that goes on elsewhere in Damaged Goods.

Something is eating away at Bev’s mother Winnie, and a great deal of unspoken horror haunts the seemingly unrelated Jericho family. Poor, slowly-losing-her-mind Eva Jericho has a black dress she’s saving for her son’s funeral. Steven Jericho sits vegetative in a hospital bed, while Winnie’s son Gabriel – curiously influential around his housing estate for a nine year old – taunts a local closeted man, Harry, teasing secrets out of his mind and making him run errands. Harry longs for his late wife Sylvie and hates himself for his nightly cruising, made all the worse by his confidently gay lodger David. The whole estate is disturbed by the suicide – and apparent resurrection – of a local drug dealer, the Capper, who quite apart from being reanimated is not the man he was. The Capper, Harry, Bev, Eva, Gabriel and others are all haunted by inner voices. Their thoughts and lives are what drive the book, more so than the Doctor Who paraphernalia you’re expecting.

One of the book’s main themes is that this isn’t the Doctor’s wheelhouse – normal people with their private lives and secrets factor into the Doctor’s adventures like bugs on a windshield, but this time they’re vital. When it comes to shaking down a housing estate, he’s stumped: “I’d find it easier to gain access to the court of Rassilon himself, than to step over Winnie Tyler’s front door. And there are seventy-six front doors in the Quadrant, seventy-six fortresses I might need to breach.” Shortly after that line he gets a foot in the door thanks to a random fire-bombing, and for a moment you do wonder if he organised it to hurry things along. Davies twists the knife several times, including: “These people never knew why they died, never had the chance to understand that greater issues had taken precedence over their little lives ... The Doctor had joined their ranks, powerless and ignorant and forgotten while disaster swept all around.” There’s something almost punishing about it. When the finale arrives and all hell breaks loose – more literally than in the vast majority of these books – the Doctor is several steps behind, and he can do nothing to stop it. Damaged Goods is a bloodbath, it is brutal – central characters die, which okay, doesn’t include the main trio, but still seems outrageous after growing to care about them so much. This is seemingly the point: the Doctor takes people for granted, and then people die. You feel every bit as gutted and powerless as the people in the Quadrant when the N-Form goes on its spree, killing at least 11,000 people. It’s around here you realise the whole cocaine plot has been strangely low in the mix – could the writer have forgotten about it? I’m betting no, as the Doctor is so wrong-footed he never makes his usual investigative strides, and then gets to watch it explode with the rest of us. Good god. (As a final thought on this, it’s interesting that a central conflict for the new series Doctor was learning to “do domestic”. He went from cold bastard Northerner to genial David Tennant in a Christmas hat. That’s beginning to look like a long-time itch being scratched.)

Implausible as it may seem, the book isn’t all bleak. The Quadrant and its outlying areas have a certain warmth – even the graveyard Harry visits for anonymous sex comes with a group of supportive men who would, if asked, come to his rescue. (He won’t ask.) Davies is refreshingly frank about sex and gay men, with characters like David all but rolling their eyes and saying “Oh give over” at anyone thinking it’s terribly weird to read about them in the first place. David is a sweet guy and immediately besotted with Chris – who is virtually omnisexual but doesn’t pick up on his signals at first. Their scenes are lovely, and David’s make-or-break joke about men having a hinge in their ribs manages to be both a believably earnest attempt to talk to Chris, and probably the bawdiest sex reference in all of Who. (Except for maybe Ursula the paving slab.) It’s juvenile to titillate for the sake of it, but it’s more grown up to be honest. This book has plenty of (mucky) honesty. And plenty of real, every day horror, including a prostitution ring run out of a downstairs flat by a married couple. Lovely stuff.

Stepping away from the sex (ahem), the most positive part of it is the prose. Occupying so many people’s inner thoughts gives the novel considerable drive which heightens the horrible moments. (Chapter Nine in particular, which moves between an impending suicide and a murder. It’s so good, you’ll pause.) Elsewhere, Davies tosses out enough gorgeous phrases and aphorisms that I had to stop taking notes. Random hits include: “It was a wonderful day, but lurking beneath it all like an unwelcome relative was the question of where the money came from” / “The suit of flame rendered his expression invisible, but all those watching knew to their horror that he was smiling” / “Harry went to Smithfield, always at night, for reasons other than remembrance” / “The pain in his chest was clawing from within – oh yes, the knife wound hurt now, it waited until it had Harry’s full attention and then crawled out of its hole on jagged legs, dancing with glee” / “Briefly, she wondered what equivalent of milkshakes had drawn them into his company” / “‘I’m in love,’ breathed David, then he ran to the bathroom to exfoliate” / “All in all, a reasonable face, bordering on handsome in a bad light” / “The Glamour’s nothing more than a shiver on water” / “Then she said no more and their chances of friendship died in the silence” / “The two women meet could no longer meet without the secret coming along as chaperone”. Despite being genuinely upsetting at times, the damned thing is a pleasure to read.

Even so, I think I’d refrain from calling it perfect. There’s a point at the end when one tragedy piles onto another and the clouds absolutely refuse to part, and I felt defeated trying to work out what it was for, other than giving the reader a kick. In fairness it must be hard to write really horrifying stuff without appearing to do it for its own sake – that way books like Falls The Shadow and Strange England lie, tediously interfering with themselves. The book says a lot of interesting (albeit unhappy) things about the Doctor and his effect on humanity, which all ring true except that a) he’s really come along in recent years, so maybe it’s a tad unfair to give him both barrels now, and b) the book’s focus isn’t really on the Doctor so much as Bev, Eva, Gabriel, Harry and David, so when it finally comes time to stick the boot in over Gallifrey’s ancient sins and the Doctor’s apathy, it feels a little bit random. Paradoxically, in delving into the humanity of its characters, Damaged Goods is a little short on protagonists; I felt like Winnie ought to have more say in events, I’m not surprised her other son Carl was written out of the Big Finish adaptation altogether, and poor Gabriel is forced to have very little say in his last dramatic scenes, which might otherwise have helped to offset how creepy he is. Chris and Roz have several tender and thoughtful moments throughout, the former with David and the latter working around the Doctor, but neither of them drives the story much. Frankly it’s a bit crowded in here. And this is sheer personal preference, but I’m not crazy about the N-Form or its links to old continuity. Talk of vampires and bowships all seems bizarrely grandiose in this context, which I suppose feeds the theme again of the Doctor being disconnected from real life. I still didn’t love it.

Of course I’d be insane to really nitpick a book that read as beautifully as this, or said as many interesting things about its characters, or felt this uninhibited and was this skilled at executing its ambitions. In clearer English: this is some of the best written Doctor Who you’re going to find, and if it makes you upset and mad sometimes, consider how many other books in the series elicited such strong feelings. It’s really something. And it’s clear that Davies was a smart choice to bring the show back, although it’s something to be grateful for that he had got a few things out of his system first.

9/10

Published on January 22, 2020 22:47

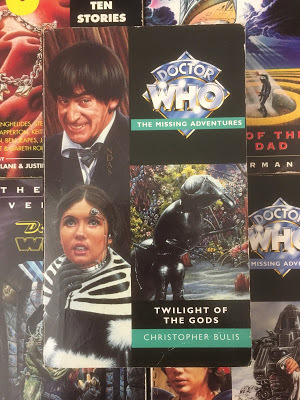

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #85 – Twilight Of The Gods by Christopher Bulis

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures#26Twilight of the GodsBy Christopher Bulis

A sequel to The Web Planet? You had me at awesome.

Okay, so it’s the only telly Who story that literally sends me to sleep. I still admire them for making it. Memorable for having no supporting humanoid characters, The Web Planet scores weirdness points over possibly all other Doctor Who. You’ve got to wonder what would motivate someone to return to that.

Short answer, I still don’t know. Twilight of the Gods plays strangely coy with its familiar setting, plastering a Zarbi on the front cover and confirming it in the blurb, then not saying it’s Vortis for 64 pages like we’re suddenly going to double take and go, really? In order for the story to work Vortis has to move significantly through space, Mondas-style, which is really rather odd but no one seems to notice or care much. Shouldn’t that be one of the main concerns? The central conflict has much to do with our last adventure on Vortis – you get one guess what sinister force is behind it all, okay it rhymes with Flanimus – but the bulk of the book is about a civil war between the Rhumons, a society split by revolution with both sides claiming the new world. They’re alien enough to require some solid time in a make-up chair, basically human otherwise. They have weary leaders, religious zealots, power-hungry lieutenants, thankless grunts, deteriorating marriages and old family manservants – same as us and, just to bludgeon the theme in, same as each other. Crammed between all this you get the occasional Menoptera clearing its throat to be noticed, even less frequently an Optera, and the Zarbi and larvae guns have what you could generously call cameos. Bad luck, Web Planet fans.

Call it a hunch, but I suspect there was a working version of Twilight of the Gods set somewhere else before someone leaned in and said “Pssst, change it a bit and get some of that sweet Web Planet dollah”. It’s not as if I was dying to read 300 pages about the Zarbi and the Optera – I doubt anyone was – but if you’re that uninterested, why bother? I’m guessing for the sheer convenience of not having to establish 1) a malign intelligence you can wake up later (that’s your last clue) and 2) a society of native non-humanoids to more clearly show colonialism, ramming home the difference between the human-ish Rhumons and the rest. Shortcut is a word that came to mind a lot while reading it.

You could also use the word authentic, I suppose. The Doctor, Jamie and Victoria are barely out of the TARDIS before they’re accosted by one lot of Rhumons who accuse them of spying for the other lot, then before you know it they’re accosted by the other lot who accuse them of spying for the first lot! Trope points there. This routine served a satirical point in The War Games (so hey, it’s era-appropriate), and a similar, more irritating point in Frontier In Space, but it’s just filler this time. The TARDIS crew then get split up and move between the two Rhumon camps and the Menoptera base; they play a forgettable sort of catch-up for most of the book, before frantically making everything go smashy-smashy at the end until the problem stops. For better or worse, this certainly feels like a Troughton six-parter with time to kill. During which, the Doctor uses local something-something-interferencein order to pilot the TARDIS properly; Jamie learns how to drive a lorry with improbable ease; and most improbably, Victoria has an interesting time of it, briefly going undercover for the Menoptera, then for one lot of Rhumons, then unknowingly for the other lot. It’s over too quickly, alas, and she’s back to worrying and fainting, which puts paid to the novel’s aspiration of setting up her departure in Fury From The Deep. This is foreshadowed in that clumsy Missing Adventures way, along with the Doctor’s need for his sonic screwdriver (which wouldn’t-you-know-it shows up in the next story!), before being picked up again right at the end to give the novel a coda. Nice try, but nul points: just giving Victoria a life-or-death adventure with a blob of autonomy and sayingthis has somehow caused her to grow up more than any other adventure before it is just another shortcut.

Sometimes the urge to skip ahead short-changes the book itself, not just its characters. The Rhumons are all concerned and/or in denial about “ghosts”, and bodies disappearing from nearby graves; there’s a reason for all this, but we mostly have to be told about it in passing rather than see it, and the main thing we take away is the intelligence controlling them. Are you crazy? Dead soldiers skulking about is way more interesting than (literally) generic grey monsters showing up a couple of times, or the political “struggle” between the Imperials and the Republicans. Even that doesn’t get a fair shake, as the last-act villain reveal (you’ll never guess who) causes them to more or less resolve their differences off-screen, even with the Menoptera. I kept expecting a reversal of this, because it’s just too easy, and it sort of comes in the last few pages… but by then it’s just bonus noise. The build-up to the main villain and its frenzied, keyboard-mashing death look sadly redundant when the stakes continue to go up after they’re gone.

Twilight of the Gods isn’t completely naïve about the Rhumons patching up their differences forever, with more ships on their way that don’t know about the ceasefire. But the ending is still as simplistic as you’ve come to expect, with the Doctor delivering a waffly, page-long speech that rings about as true of the era as Jamie’s HGV licence. (We know Pat Troughton liked to improvise, so great slabs like this probably would have gone out the window.) The Second Doctor is reasonably well-written otherwise, embracing (deliberately?) the contradiction of letting violent solutions take place but seemingly being upset about them. He’s mostly up front about his intelligence and keeps on everybody’s good side as much as possible, which is all a bit off, IMO, so call it a draw.

If you asked me what I thought when I was still reading it, I might have been more favourable. Twilight of the Gods is a mover, which I can’t sniff at: the characters are straightforward and they say what they mean, the action is easy to visualise. Younger readers would probably enjoy it, and I had a heck of an easier time here than I did with The Death of Art. That might seem an unfair comparison, but oddly there are sections that reminded me of the Quoth: some ethereal beings are up to something and they communicate in a bizarre, off-kilter way, which reads like Christopher Bulis experimenting and doesn’t fit at all with the rest of the book. No thanks. “Ah,” you might say, “but didn’t you want weirdness? It’s The Web Planet!” To which I’d say, I think we’ve established my preferences and limits as a reader – give me consistent weirdness and I’ll think about it, give me random bursts of what-the-hell-am-I-looking-at and I’ll count the seconds until we’re outta there, thanks. (Incidentally, the ethereal guys enable Bulis to retcon the history of Vortis, which is certainly a thing you could do? Ditto the wholly unasked for explanation for how a Menoptera can fly. Dude, if you hate The Web Planet, just say so.)

Somehow, I still don’t hate this. It can be a lot like Classic Who at times, filler, quarries and all. But there’s very little to recommend besides a basic level of competency and a quick pace. Bulis has done better, and hopefully will do again. Meanwhile if you want to get your alien planet fix, go and read Venusian Lullaby.

5/10

Published on January 22, 2020 05:05

January 21, 2020

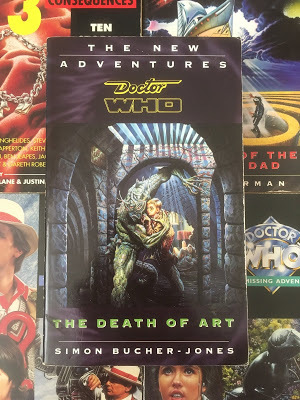

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #84 – The Death Of Art by Simon Bucher-Jones

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#54The Death of ArtBy Simon Bucher-Jones

Well this is a fine Welcome Back. Not that I’ve only just read The Death Of Art, of course: I started it months ago, then mysteriously ran out of steam. Later I started again in case I’d forgotten any of it, and... strangely stopped again. Huh. Life intervened for a few months until I finally decided to stick the landing on my third go, or perish trying. In all fairness, it could just be a coincidence that I struggled to finish it several times?

Sigh. Noooope. The Death Of Art is another of those first-time-author books that aren’t afraid to get weird, and aren’t too bothered about the people reading the result. There’s a certain spectrum for these which runs from “fires random words for shock value” to “seems to know what they’re doing even if we don’t,” and Simon Bucher-Jones lands at the smarter end. I mean that: there’s promise here, and good ideas. (Plural makes a difference.) But unavoidably there are sections that read like a fuse box, and the overall thing just sits there bubbling instead of actually moving. And oh, it is work.

Some of this I’d point to the editors at Virgin, who surely could have cracked the whip a bit more. Yes it’s interesting, but will anyone enjoy it? Will anyone who isn’t the author understand it? Fancy, idea-driven, heavily-stylised, showy-offy prose is all well and good (okay, I mostly hate it) but there’s also a lot to be said for knowing what the hell is going on.

So about the plot. (I almost had to Google it.) Following a brief cameo from Ace (hi and bye!), the TARDIS crashes (again) in France circa 1897. This is after an odd bit about Charles Dickens some time earlier, which had something to do with a monstrous possessed doll house that sure sounds like a badass setting for a Doctor Who story. On arrival, the TARDIS promptly begins morphing internally into a replica of France. The Doctor, Chris and Roz go investigating because they believe a proliferation of psychic powers will cause a disaster in time, which in turn is what summoned them here. If you’ve read my reviews post-Original Sin, you’ll know I love it when these three are on the case.

Roz befriends a psychically talented American; Chris joins the local gendarmes; the Doctor tries to get himself committed to an insane asylum with a surprising lack of success. All fun scenarios, by the way. Roz’s eye-rolling interaction with the impressionable Daniel is fun, if tragically short-lived; Chris’s easy application of his talents to 1897 police-work is brilliant (his effortless memory skills in particular); and the Doctor stuff… eh, that doesn’t come to much. I think we get one amusing scene involving grapes, but that’s it. Boo. More importantly we have the Family and the Brotherhood, warring (?) factions who can transform themselves as well as swap bodies. There’s a seriously cool bit where one character is run over by a horse and carriage, and his consciousness leaps straight into the cab driver who murdered him. On the flipside, some characters body-swap to the point where I don’t know who they are any more. And some of them just never distinguish themselves in the first place. When the last act rolls around it’s probably quite dramatic, but it would be more so if I wasn’t still playing catch-up.

In amongst all this (or between it, under it, who knows etc.) are the Quoth. They are… something, and they are doing… something. A direct explanation arrives literally three pages before the book is over, but suffice to say, the Quoth are a really cool idea. Put through a mangler. Then translated into Japanese. And back again. And finally juggled over an open bin. Seriously, who is reading the Quoth bits for fun? Were you retaining any information at the end of each paragraph? No fibbing. The Death of Art isn’t the first New Adventure to unload random jargon on us, and at least it’s not as sustained as the fever dreams of Time’s Crucible or Strange England, but I still tuned out every time the Quoth heaved into view. And every time the book dipped into poetry, which I admit is purely a pet hate. (Yes, I know I’m a philistine.)

The writing in this is, charitably, all over the place. For every paragraph rambling on about the Quoth and their pattern-lifetimes, there’s a sentence like: “It was starting to look as if she would not always have Paris”, or “Mirakle’s blonde receptionist was not enjoying her introduction to the Roz Forrester closet experience”. For every bit that takes the plot’s transmogrifications a little too far and just generates random words at us, there’s something pithy like: “For once in his lives, he needed to sleep. Besides, it was the quickest way he knew to make the phone ring, aside from getting into the bath”, or “There was an indescribable noise that was not like TARDIS materialisation. That was because the TARDIS was not materialising. Then there was a noise like everyone in the TARDIS screaming. That was because they were.” And Bucher-Jones has a real knack for ending his paragraphs or chapters with a shock, like “Mon Dieu. This future, then, you have come to prevent it?” The Doctor smiled. “No, to make certain of it”, or “As he turned he saw the first of the dolls crawling towards him.” Hell yeah! Conversely, The Death of Art indulges in one of my biggest pet hates in literature: frequent, short sections. I can hardly think of anything more annoying than settling down to a scene and then being somewhere else already, sometimes up to five or six times across over two open pages. Mate, it’s a novel. Relax. We’re invested. There’s a cup of tea next to us. We can stand to read about something for more than a page without reaching for the TV remote. (Unless it’s the Quoth. DEAR GOD, WHAT ELSE IS ON.) All this kind of fidgety nonsense does is remind me regularly that I could stop reading.

It’s frustrating, because it really feels like a good idea is in here, and a good writer is working on it, and just… stuff got in the way. You could pare down the Family and the Brotherhood, make it clearer who’s doing what. You could stick with the characters we get attached to, like Daniel. You could sprinkle some plot developments earlier in the story, or just plain kick it up the arse a bit sooner. For all the ballyhoo about Psi-Powers arc, you could make more of actual psychic powers in this, since the plot is really more focused on physical transformation. You could edit the Quoth to within a quark of their lives, so those bits actually say something in human terms rather than halting whatever momentum you’ve got going. Certainly you could give the Doctor more to do, and treat Roz a little better – she’s forcibly disrobed at least twice, in that New-Adventures-at-their-sleaziest way. Chris has a few solid laughs pretending to be the Doctor, which makes good use of Cold Fusion, but the book’s rampant “AND THEN THIS HAPPENED, THEN THAT HAPPENED” cutting makes it just some more noise in the mix. Ace impinges cleverly on the story a little more later on, thanks to a link back to Christmas On A Rational Planet – but that’s not the happiest link for me, as that was another book I struggled with. I was reminded of it often. Another one joins the “Huh?” club.

The Death of Art isn’t a complete wash-out, but it is what it is: slow, practically static for the most part, waking up long enough to be thoroughly unpleasant or unexpectedly witty. Poor Daniel does not wake up in the Epilogue to realise it was all an absinthe nightmare, but you might.

4/10

Published on January 21, 2020 22:46

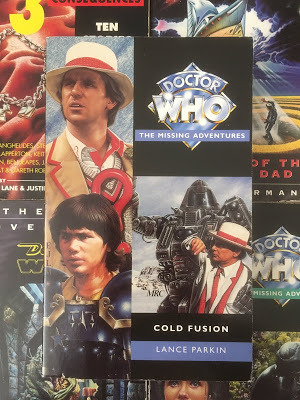

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #83 – Cold Fusion by Lance Parkin

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures

Doctor Who: The Missing Adventures#29Cold FusionBy Lance Parkin

NB: I’m breaking publication order for this one as the blurb puts it squarely after Return Of The Living Dad. I’m swapping out The Shadow Of Weng-Chiang which won’t cause any ripples coming later in the run.

Talk about a hard sell. Virgin’s first bona fide multi-Doctor story, directly crossing over the New and Missing Adventures, written by an up-and-comer whose last novel everybody loved? I mean, sure, if you happen to like that sort of thing.

Cold Fusion is an event book, so you’ll probably want to read it whether or not you’ve read any reviews. I really had no idea what it was about or what kind of story it was – although it’s a fair bet this is a multi-Doctor story more in the vein of “they both happen to be there” than “all of time and space is on the blink AND ONE DOCTOR ISN’T ENOUGH”. That’s good, as the latter is difficult to do well. I’m only surprised it took them this long. (There was apparently an imperative notto write multi-Doc books, but then at the same time there were more Doctor cameos in Virgin than you ever got on television.* Work that one out.)

Cold Fusion is primarily a Fifth Doctor book – it is a Missing Adventure after all – with the Seventh Doctor sneaking around the outskirts. That’s a neat way to approach a multi-Doctor thing, and it suits McCoy who has doubled down on deviousness in the New Adventures. But it does mean you’re not getting much multi-Doctor bang for your buck. There’s something pointed and interesting about using these Doctors – Davison having just regenerated, young and idealistic, plus McCoy getting older, more cynical and pragmatic. But Lance Parkin has his work cut out just finding something for the Doctor, Tegan, Nyssa, Adric, the Doctor, Chris and Roz to do. Making sure two out of that lot spend time trading insults does not seem like a priority, and a “Whose side is he on?” dichotomy perhaps needed somewhat equal screen time devoted to each side. McCoy sits most of the book out, so there isn’t much ideological sword-crossing.

After the TARDIS reacts to something wrong in the vortex, the Doctor (Davison) and co. arrive on an ice planet mostly known for scientific research. It is ruled by the Scientifica, who are so goal-driven that they have slaves and roll their eyes when people complain about it. One of them, Whitfield, is very interested in a strange machine that seems to pre-date known human civilisation. Incidentally (or not), there have been sightings of “ghosts” nearby.

A large number of Adjudicators are on the planet, ostensibly to deal with a terrorist element attacking the Scientifica, but this is clearly and suspiciously overkill. Nyssa meet a conspicuous and slightly randy blond gentleman investigating all this (Chris, duh) and Adric ends up working with a gruff ex-Adjudicator (Roz). Tegan and the Doctor soon make the acquaintance of a distressed lady Time Lord, Patience, and then make their way towards a shadowy figure who seems to be pulling the strings. Probably with the crook of his brolly.

This book has one of those plots where a lot of individual things seem to be happening, yet somehow they don’t knit together into a single, forward-moving plot. I never felt like the story properly “started” – the characters just move around and meet up in various combinations until it’s time for the denouement, which is surprisingly rushed at that. The nature of the “ghosts” is revealed too near the end; an apocalyptic event is averted via the Doctors playing “contact” and casually saying it’s been averted; a neat solution is manufactured literally by magic; and then the remaining problem neatly blows itself up quick-smart as well. By that time I’d lost interest in what all the Adjudicators were up to or what was going on with Adam, the planet’s resident terrorist-or-maybe-freedom-fighter. Questions such as the nature of Patience, who exits the story rather shockingly but without dwelling on that for some reason, are left for future books. I’d lost track of where Nyssa, Tegan and Adric even were.

An obvious problem here is hype, and it’s debatable whether that rests on Lance Parkin. A multi-Doctor story carries certain expectations, and it’s no exaggeration to say the Doctors only share thirty-odd pages near the end. Mixing the New and Missing Adventures is an intriguing idea – although the waters are pretty muddy with some MA writers playing up the blood and horror elements you didn’t get on TV – and Cold Fusion does this quite well in the last burst of pages. The two Doctors have their own approaches to the problem, with McCoy wryly commenting on his younger self’s fondness for suicidal selflessness, which contrasts tragically against his own cold manipulations in the final chapter. But there isn’t enough time to really make something of that, with Davison literally getting knocked unconscious before they can have it out. (Admittedly it's very funny.) Other ideas, like the true nature of the ghosts, are certainly interesting but not made enough of. The running theme of robots with unusual temperaments and jobs – such as an analytical Freudroid, and a robot with a chipper northern accent – is very welcome, but feels a bit too much like a random sprinkling of colour.

It’s a little schizophrenic to compare this to Just War, as it’s not trying to be a remotely similar book. However, we do know from Just War that Parkin can be brilliant at character development – that was a seminal story for Bernice, and there was some lovely Roz stuff too. The groaning cast list here precludes any heavy-lifting character work, so we instead opt for random blobs of it. The text observes a few times that the Fifth Doctor and his companions have been together less than a week, with Adric puzzlingly believing he’s only known the Doctor at all for “a couple of weeks”. There’s a funny bit where Davison ponders the length of his hair, which fluctuated between his first and second stories due to the shooting order. (Nerrrrrrd!) There’s a nice moment where Tegan contemplates her past and what she hopes to do in her future. Nyssa discovers that a Traken colony has survived, which cheers her up a bit – and is perhaps meant to explain what is, when all’s said and done, a pretty placid Nyssa considering what happened to her. On a darker note, Roz accidentally kills a man and then convinces herself that it was necessary. And McCoy is unavoidably confronted with Adric, and must not say anything about what will happen to him. At first this is shrugged off – par for the course – but we do get this lovely sequence: “The Doctor was more relaxed around Adric than anyone else she’d ever seen. He watched him, was interested in what he was doing. Like a grandfather playing with his grandson. The Doctor’s eyes betrayed a sadness of some kind, some deep regret that he was leaving unvoiced.”

It functions reasonably well as a New Adventure, with Chris and Roz babysitting the Doctor’s earlier companions (in Chris’s case, hilariously almost spoiling what happens to Adric – awkward), although the Doctor’s ultimately callous attitude towards the villains is thrown into maybe too light relief by Parkin playing up his whimsical aspect. I guess this is to help mark him out from the Fifth Doctor. (Incidentally, I couldn’t find anything to put this right after Return Of The Living Dad. The blooming romance between Chris and Roz is nowhere to be seen; otherwise couldn’t this take place anywhere, sans Benny? EDIT: It’s actually more to do with The Death Of Art, up next, which uses these events to create a fun bit with Chris.) It’s an at times very thoughtful Missing Adventure, occupying that space right after Castrovalva when all this is new to his companions, and to the Doctor himself. At the risk of becoming a broken record, however, we don’t really delve into it. The Doctor could use Patience as a way to come down from his own experience, but they don’t talk enough to make it happen. The Big Finish audio Psychodrome does a rather natty job with the same time-frame, opening the collective wound a bit more.

The guest cast have very little room to distinguish themselves. Whitworth, the scientist, espouses the values of the Scientifica and is dating one of the Adjudicators, but beyond that I got nothin’. She does make some pretty chilling observations about transmats, and how they literally involve creating a whole new self every time you “arrive”. (A sequence later on describes what happens when it goes wrong, in case you weren’t already creeped out.) Adam The Friendly Terrorist shows up for a scene or two and then promptly buggers off again; the only thing I registered was his friend, a shark-person named Quint, for obvious reasons. Patience ought to be the book’s biggest coup, and there is something to be said for the Time Lord world-building that seems to follow her around. We learn (although it may not be 100% accurate) that the Doctor took Susan away from Gallifrey because she was woman-born, and Time Lords don’t allow that (see Time’s Crucible); Patience suffered something similar, and may or may not be back somehow later on. Interesting as this stuff is – and there’s a casual-as-you-like reference to the House of Lungbarrow as well – Patience literally doesn’t say anything for most of it, and is then very abruptly taken out of the picture. So what exactly was all that in aid of? She could be a telepathic bag of flour.

Livening all this up – if, like me, you find the gradual moving of chess pieces unexciting – are a number of evocative action sequences, including a bloody robot attack at the start, an unusually conscientious train robbery, an avalanche and best of all, a space station hurtling towards a planet. The writing of that last piece is spectacular, likening the approaching station to a marble, a tennis ball, a melon and so on until it’s impossibly vast. There are also quite a few light-hearted moments, particularly when Chris first makes himself known using the surname Jovanka and an outrageous Aussie accent, outraging Tegan; there’s some funny confusion over whether the Doctor has regenerated in the course of the story, with McCoy asking if he has become “all frock-coat and youthful appeal? Well, perhaps I did but I haven’t yet.” (Yes, it’s a Five Doctors gag. How apt!) And there’s a bit where the two Doctors both reverse the polarity, nabbing Steven Moffat’s “confusing the polarity” joke 17 years early. Nicely done.

I wish I could think of more to say about it. I wish I liked it more. It’s not as if I hated Cold Fusion, but it wasn’t the book I was hoping for – even though I couldn’t specifically tell you what book that was. There are many deftly-written moments here, like the action and the occasional bit of comedy, and even scene transitions which you would ordinarily take for granted but are given clever attention here. And there are many good ideas, like the Scientifica and the ghosts and the whole concept of the Doctor at two points in his life, dealing with the same crisis and reaching different conclusions. You could do so much with that. Cold Fusion maybe tries to do too much, and ends up not doing much with any of it.

6/10

* Did I miss anyone?

* Genesys had Pertwee helping by proxy.

* Apocalypse had a Troughton flashback.

* Revelation had several Doctors in his own head. No Troughton or Colin, IIRC.

* Love And War has a very grim Pertwee memory.

* Blood Heat had Pertwee’s corpse.

* Tragedy Day had prequel material with Hartnell.

* Legacy had a prequel scene with Perters.

* All-Consuming Fire had Hartnell and Pertwee pop up.

* State Of Change – see Genesys. (Spotted the favourite cameo yet?)

* Downtime had a few Doctors visiting Victoria, notably Tom and Pertwee. Pat appeared in a flashback.

* Head Games had a rather unhappy Sixth Doctor cameo. He’s also insinuated in Love And War and Return Of The Living Dad.

* Cold Fusion has memories of Hartnell, Troughton and Tom.

Published on January 21, 2020 04:59

January 20, 2020

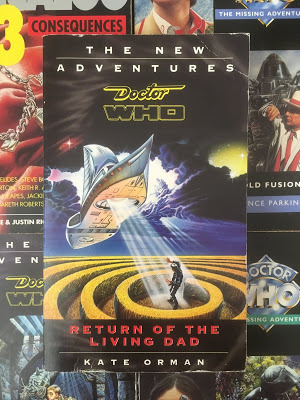

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #82 – Return Of The Living Dad by Kate Orman

Doctor Who: The New Adventures

Doctor Who: The New Adventures#53

Return Of The Living Dad

By Kate Orman

NB: I’ve owned Return Of The Living Dad for at least twenty years (and never read it, etc. etc.). I guess it always seemed like a strange place to jump on board, with even the title shouting “Ongoing Plot Ahoy!”, so I didn’t. Better late than never. This is the last of my Who Books I Own But Mysteriously Haven’t Read: Virgin Edition, but don’t panic, I’ve got a few BBC ones that still fit the bill…

She’s baaaaaaaaaaaack! As in Bernice, obviously, though a returning Kate Orman is also cause for a little happiness boogie. There’s been a good-book drought since Happy Endings, for me at least, and I could do with a pick-me-up. What’s that you say? A solid lump of character development for Bernice? That will do nicely, thank you.

Working at an archaeological dig with Jason, Bernice randomly meets someone who knew her father. Suddenly there’s a chance to find out what really happened at the fateful battle that left Isaac Summerfield branded a coward. Bernice contacts the Doctor to take her back for a look. This isn’t her first rodeo, so she knows she’s not allowed to interfere: it will be enough to know.

Of course it doesn’t go as planned, and in a style that may be permanent following the earlier, whip-cracking SLEEPY, Orman has it going almost immediately. Bernice meets her father’s old colleague three pages in. She meets her dad (spoiler alert?) on Page 28. Five pages later, the entire landscape of the story transforms on the spot. Return Of The Living Dad is another absolute belter from Orman, as full of good ideas as the denouement of a Paul Cornell novel and arguably as high on sugar. In all honesty the approach gives up mixed rewards, but whatever else happens, it may not be possible to be bored reading a Kate Orman book.

Plot-wise, this isn’t SLEEPY. Return is about character work (to a point), so we get the same kinetic whoosh in a story that prizes stillness, smallness, focus. The vast majority of it is set in a small English town where Bernice figures out her relationship with a man who went missing. Before that, the Doctor, Chris and Roz are having a quiet time in Sydney. The Doctor works in a hospice, trying to do some good on a different scale. Roz questions his motives, but I think the Doctor is, at this point in the New Adventures, trying to be a better person. The sequence seeds the idea of the future and how you can shape it, whether or not you’re around to see it. “‘When you phoned,’ said Chris, ‘you said there was someone you wanted us to meet.’ ‘There was,’ sighed the Doctor. ‘There was.’” Later there are visions of the future for most of the cast – including a premonition of the Seventh Doctor’s lonely, purposeless death – and fear for the future is ultimately what drives the plot. It’s an interesting direction for a story literally about catching up with the past.

I love a story that focuses on what’s important, and there are loads of rich, telling moments in this one. Bernice tries to juggle her father, Jason and the Doctor, naturally expecting them not to get along and quietly believing they’ll abandon her. Her feelings about the Doctor follow on nicely from Continuity Errors – as does the surprisingly apt “Fixing history used to be my job”. When he seems to have hyperthermia, Bernice immediately snuggles up shirtless to give him some body warmth. Apart from the inevitable Jason remark afterwards, this gives us: “Benny burst into tears. ‘I can’t think of anything clever to say,’ she whispered. ‘Please don’t die.’” It’s so refreshing to have a character not necessarily like the way the Doctor operates, but understand why he does that and know he’s trying to be better. She loves him with a lot less sturm und drang than it took to get Ace to the same place. And he feels the same, openly telling her he misses her and how nice this is, and in the first place being so quick to say yes to this trip through time. There’s a running thread of his not understanding why humans do things like reunite with an estranged father, and I’m not sure it’s entirely justified – he does spend a lot of time around us, just sayin’ – but it’s all worth it for the glorious awkwardness of their parting: “The Doctor looked at his feet, looked up at Benny, hesitated, folded his arms, unfolded them and put his hands in his pockets, looked up at the sky, took his hands back out of his pockets, stepped through the speckles of light and leant up and kissed Benny on the cheek. She looked at him in astonishment, breaking into a beautiful smile. And vanished.”

Meanwhile, Chris and Roz fumble through a growing attraction, and worry about whether any kind of relationship could work with the Doctor in their lives – out of practicality rather than bitterness. Their respective personalities have loads of room to work in lovely passages like: “‘I had this dream,’ said Chris. I don’t think I wanna hear this, said Roz’s expression”, and “‘We’re not in love, are we?’ Chris murmured. ‘No,’ said Roz. ‘You can keep nibbling on my neck if you want, though.’” (Bonus points for “You love everybody ... You fall in love on every planet we visit.” Bang to bloody rights, Squire Cwej.) It’s not exactly their story, but there’s a real arc going on between them, in between all the other stuff, and it’s totally plausible to push them in this direction.

When it comes to Isaac Summerfield the book is up against expectations. Make him too nice and it’s boring, make him a disappointment and it’s obvious. I don’t think it’s too great a spoiler to say that we get a little from both columns, but the emphasis is mostly on his not being the coward he’s painted as. There is a slightly worthy air to The Admiral, as he’s generally called, as well as a stiffness and a general foreknowledge that make his scenes with Bernice pretty one-sided emotionally. It’s still rewarding to read, but there are so many secondary characters buzzing around him, and he’s just so busy that the book never approaches the “exceptionally dull slice-of-life novel” Bernice at one point wishes it was. Plot-wise it’s an intriguing setup: arriving twenty years prior to the TARDIS, Isaac and his crew use the town of Little Caldwell as a base / haven for aliens and castaways, all of them displaced by UNIT and sundry invasions. They mop up the Doctor’s leftovers, in other words, sending aliens home or otherwise helping them out. It’s another clever, albeit very fannish bolt-on in the same vein as the Glasshouse. And if you like fannish ideas, hoo boy.

We’ve got aliens aplenty, running the gamut from cheeky mentions to full-blown characters. Ogrons, Ogri, Chameleons, a Vardan, a Sea Devil, a Navarino (the Delta And The Bannerman blobs – I had to look them up), a bit of an Auton, Daleks by proxy – so that’s another book giving a jolly “Do your worst!” V-sign to the Nation Estate. Speaking of pepperpots, one of their early televised stories is hugely vital to the plot. (You can probably guess which one.) So is the plot of an otherwise unconnected Tom Baker story. The Doctor is what indirectly triggers Isaac’s operation in the first place, and there is some in-universe nerddom with Joel, a time-displaced lad who discusses the Doctor and his antics online, gently ribbing real Who fans and getting in there way before LINDA. (“They figure [the Doctor]’s a code name, and they’re having this big flame war about whether he could ever be a woman. Same old debates.” Too sodding true.)

The longer it goes on, the nearer it gets to fanwank. That’s not necessarily a bad thing depending on how well you execute it: I was swept up enough in Happy Endings that I didn’t mind the book-length love letter, and Return Of The Living Dad very much feels like it’s showing up to the same party, giddy to unload its own car boot full of references. The setting is eerily similar to Cornell’s (and to several of his other books – he loves a little village) and there’s a shared enthusiasm for Virgin canon, which is pretty much my complaint Kryptonite. There are aliens from First Frontier, somebody mentions a Fortean Flicker, traumatic events from several books are remembered in the form of scars, and there’s even a loose end tied up from bloomin’ Witch Mark! (I had heard about that one in advance, but it still blind-sided me. I’ll bet Cornell wish he ticked that off.) At one point somebody mentions Isis, and I honestly thought the Timewyrm would rock up too.

Particular attention is paid to Orman’s The Left-Handed Hummingbird, and one of its settings is reused. I had largely forgotten the segment where the Doctor was tortured by Hamlet Macbeth, and going back to my review the 1968 portion of Hummingbird didn’t do a lot for me at the time. Literally returning to the scene of the crime is a good enough reason to dredge it up again, although there is a general feeling of “Well, why haven’t you been thinking about The Left-Handed Hummingbird all along?” C19 and the like (ticking off the Missing Adventures and Who Killed Kennedy) are important here, with the xenophobic Woodworth forming a paranoid alternative to Isaac’s commune. The curse of Hummingbird strikes again, however, as Woodworth’s character becomes more shouty and less interesting (also dropping the interesting relationship with the Doctor en route), and this portion of the story is ultimately something of a red herring anyway. I suspect that in time it’ll slip my mind in favour of other, more colourful bits on offer.

But gosh, there are a lot of bits. Isaac’s crew includes aliens who wear holographic disguises and sometimes use different names; there’s a women’s group camped nearby; an active weapons facility as well; the old house from Hummingbird, with attendant morally dubious staff; various sinister figures hovering around with their own agendas; the TARDIS crew, plus Benny and Jason; plus a ghost. The sections are kept short and kinetic, and the writing often makes very amusing light of its own pace – Chapter 5, in its entirety, reads: “And they landed in December, outside a post office.” As well as the title, there are jolly puns to be found in chapter headings, my favourite being Chris Chris, Bang Bang. The writing is thoughtful and often hilarious, what with it being a Bernice book and everything. So much good stuff, like “Believe it or not, this is the source of the transponder signal.’ ‘The Tisiphone, said Benny, ‘is conspicuous by its absence.” / “[The Doctor] looked ordinary until your invasion fleet unexpectedly dropped into the sun.” / “Most planets look like quarries. Earth is precious.” / The Doctor describing his adventures: “Hours of tedium followed by moments of sheer terror.” / A returning alien on seeing the Doctor: “One six-foot, fur-covered humanoid ran away waving its three arms and yelling, and drove off in its Mini.” All that and Graeme, the friendly lump of Auton shaped like a spatula, conspire to make Return Of The Living Dad almost aggressively loveable.

I’m not sure if I love it, exactly. The setting is my bread and butter: small town, creepy goings on, character interaction high on the agenda, “monsters” shown in a more sympathetic, even heroic light. It has that kinetic excitement that is becoming one of Orman’s trademarks, along with well-observed character writing. It takes an “important” event in the New Adventures canon and takes the pressure off, adding a casual ease to the reunion that forces your expectations to reboot. It’s excellent in many ways, but the central sugar rush makes some of the supporting cast a little difficult to hear above the din, and I’m still umming and ahhing about the plot’s reliance on established canon. It would be an interesting one to read again, knowing what to expect, and it’s certainly rewarding enough to look forward to a second time. Okay, so gift horse, mouth – caveats aside it’s a sweet and fun book, and it was worth the wait.

7/10

Published on January 20, 2020 22:51

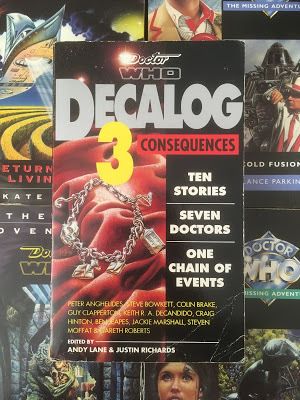

Doctor Who: The Virgin Novels #81 – Decalog 3: Consequences edited by Andy Lane and Justin Richards

Doctor Who: Decalog 3: Consequences

Doctor Who: Decalog 3: ConsequencesEdited by Andy Lane and Justin Richards

Time for more short stories, mostly by new writers, which is exciting. The theme here is consequences, and we’re leaning back towards the linked story format of Decalog 1: “Ten stories. Seven Doctors. One chain of events.” Interesting to see how the authors handle it, and whether anybody takes it literally and coughs up Revenge Of The Sensorites.

Let’s find out...

*

...And Eternity In An Hour By Stephen Bowkett

We’re off to a dramatic start as the Third Doctor and Jo are sent on a mission by the Time Lords. They must halt the spread of a colossal time rift which is causing (among other things) horrific deaths on Alrakis. There are ideas aplenty, such as the TARDIS having “intuition circuits”, which explains why it always arrives at pivotal moments. (Fair enough, but personally I like the New Who version: “I always took you where you needed to go.”)