Amy Lavender Harris's Blog, page 6

December 10, 2010

Big City Books

The Star has just published a short article I wrote on Toronto-focused children's books. It's available online here, on the Star's 'Parentcentral' website.

The Star has just published a short article I wrote on Toronto-focused children's books. It's available online here, on the Star's 'Parentcentral' website.

[Note: If you've come here from the Star's website and are interested in seeing the full list of children's books, click here for a catalogue of Toronto literature by genre (you'll need to scroll down a bit to get to the children's books.)]

In the article I focus on books mainly for younger children, particularly those with vivid pictures and simple stories. Among the dozen or so books discussed are these gems:

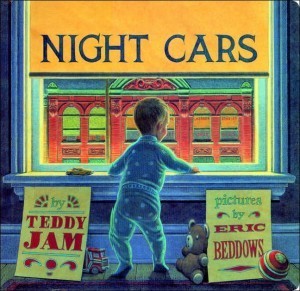

"Teddy Jam"'s Night Cars (Groundwood; beautifully illustrated by Eric Beddows). Teddy Jam was the alias of Governor General's Award-winning novelist Matt Cohen, and is a lovely picture book for very young children.

Joanne Schwartz and Matt Beam's City Alphabet (Groundwood), a postmodern alphabet book that turns found texts–from graffiti, street posters and sidewalk grates–into a semiotics of the street.

Zelda Freedman's Rosie's Dream Cape (Ronsdale), a book for slightly older readers about a young girl toiling in a garment industry sweatshop in early twentieth century Toronto. It's a heart-breaking and ultimately beautiful story and loss and beauty.

Joanne Schwartz's Our Corner Grocery Store (Tundra). Illustrated by Laura Beingessner, Schwartz's storybook was inspired by a real-life west-end family run grocery store.

Why read children's books set in Toronto? If you're a parent, doing so is a way of bringing the imagined city to life and reminding ourselves to find the extraordinary in the everyday. Many Toronto-set children's books (e.g., Barbara Nichol's Dippers, a story about winged creatures that rise about the city's ravines) remind us that storyland doesn't have to be somewhere fantastic or far away. The imagined city can be reached with a single turn of the page.

In the final chapter of the Imagining Toronto book, I talk about how having a child has altered my own view of the city and its literature, observing,

My daughter is a city child, born into a landscape of gleaming high rises, graffiti-stained alleys and verdant ravines. Her reference points are urban ones: streetcars and subway trains, stray cats, conniving raccoons, recycling trucks, jackhammers, concrete wading pools and the cadence of strangers in constant motion around her. [...] In important ways her life has already been shaped by this city, and so naturally she has been introduced to its stories, beginning with Dennis Lee's classic Alligator Pie and Allan Moak's A Big City ABC. Her bedroom bookshelves are well stocked with books to grow on, and together we read a new one almost every night.

In truth, though, these stories are for us more than they are for her: like all children she was born knowing exactly where the real and the imagined city meet. We are the ones who must remember how to make our way back to the city within the city, the city at the centre of the map.

Reading–and reading to our children–about the city is the best way to find our way back to the city at the centre of the map.

December 4, 2010

Why We're Teaching the Wrong Kind of Canadian Literature

A few days ago in the Globe & Mail acclaimed novelist (and former Writers Union of Canada President) Susan Swan wrote eloquently about the failure of Canadian educators to teach Canadian literature in schools. Citing literary lobbyist (why don't we have more of these?) Jean Baird on the "lingering attitude that Canadian literature is substandard," Swan identifies five reasons why Canadian literature, while continuing to become increasingly popular and diverse, is taught less and less in Canadian schools. Among them: the absence of a national (or even in many cases a coherent provincial) education strategy, budget cuts that (in addition to gutting book-buying programs) have seen librarians replaced with technicians and books replaced by other media, and teachers who themselves know little about Canadian literature.

become increasingly popular and diverse, is taught less and less in Canadian schools. Among them: the absence of a national (or even in many cases a coherent provincial) education strategy, budget cuts that (in addition to gutting book-buying programs) have seen librarians replaced with technicians and books replaced by other media, and teachers who themselves know little about Canadian literature.

My initial response to Swan's article was one of surprise. In the late 1980s and early 1990s I attended two very different high schools (one in the suburban Toronto area and the other in small-town Eastern Ontario) where Canadian literature received a strong–even overbearing–curricular emphasis. Far from seeing Canadian literature overlooked, we were subjected to it continually, and I have little doubt many of my classmates felt we had encountered all too much of it.* Canadian authors we were subjected to included Margaret Atwood, Margaret Lawrence, Alice Munro, Robertson Davies, Ernest Buckler, Roch Carrier, Susannah Moodie, David Helwig and Dennis Lee, among numerous others. If there was a flaw in this curriculum it was that what we read emphasized rural or historical themes and was generally depressing. Still, my interest was piqued strongly enough that I spent the better part of two years reading and writing about Canadian nature poetry and have read almost exclusively Canadian (and, for the past five years, Toronto) literature ever since.

Still, my sense that Swan is essentially correct comes from having spent the past five years teaching an undergraduate literature course in which the students–most who graduated from Toronto-area high schools within the past four or five years–look blankly at me whenever I mention Margaret Atwood (whose writing, scholarship and journalism have essentially defined Canadian literature for the last generation or two), Michael Ondaatje, David Adams Richards … even Dennis Lee, whose children's poems are seemingly inescapable.

I'm not certain, however, that the solution is to establish national curricular standards for the teaching of Canadian literature in schools.

For one thing, there isn't a Canadian literature so much as there are many Canadian literatures. By this I mean something other than the old 'regionalism' thesis people haul out in efforts to explain why Manitobans and Maritimers drink different kinds of beer. I mean something far more particular. It seems to me that rather than having everyone in the country poring over the plot of Late Nights on Air or Execution Poems (which would themselves be a vast improvement over Roughing It In The Bush), high school students in Sackville would do better to read David Adams Richards (and Clarke) while Vancouver students could focus more particularly on Douglas Coupland and Susan Musgrave.

What I am arguing is that rather than a national or even a regional education strategy, what we need is a far stronger commitment to engaging with local literature, particularly when it reflects the geographical, cultural and socio-economic backgrounds of students learning about it.

The students who take the Imagining Toronto course come from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds. Many are Italian, South Asian (particularly Indian or Sri Lankan) or Caribbean. Margaret Atwood means nothing to them because she says nothing about their cultural milieu. They don't care about Manitoba Mennonites, Left Coast computer programmers or wayward sons and daughters hoping to get off (or get back to) the Rock. They want to read, instead, about genocide, gang warfare and racial profiling and about people struggling with their sexual orientation and inter-generational cultural conflict in novels, stories, poems and plays set in suburbs and subways and shopping malls, airports, alleyways and downtown clubs. They want, in short, to read about themselves.

A 2007 Toronto District School Board study found that what GTA students desired most was to learn about themselves. The study found that students who did not find their experiences reflected in the curriculum were more likely to feel disengaged with the education system. Its findings seem to correlate with evidence that racialized students–particularly black or Aboriginal students–are far more likely to drop out of school than their white counterparts.

One way to serve these kids a little bit better would be to expose them to literature reflecting their own experiences. It's not that difficult a task. While researching the Imagining Toronto book, I began compiling culturally-specific readings lists, not because I saw the city's literature compartmentalized primarily in this way but because my students kept asking if there were any Toronto novels about Italians, Chinese, Tamils, Trinidadians, queers, suburbanites, Jews, Muslims and so on. It wasn't that these students wanted to read only about themselves: rather, this was their entry point into the city's–and Canada's–literature.

One way to serve these kids a little bit better would be to expose them to literature reflecting their own experiences. It's not that difficult a task. While researching the Imagining Toronto book, I began compiling culturally-specific readings lists, not because I saw the city's literature compartmentalized primarily in this way but because my students kept asking if there were any Toronto novels about Italians, Chinese, Tamils, Trinidadians, queers, suburbanites, Jews, Muslims and so on. It wasn't that these students wanted to read only about themselves: rather, this was their entry point into the city's–and Canada's–literature.

Like Swan, I'd love to see more librarians in schools with research specialties in Canadian literature. I'd like to see book budgets used for newer, more relevant literature rather than paperback reprints of stale-dated American or European novels. I believe that before being hired, high school teachers need to demonstrate adequate knowledge of the literature they will be teaching. I agree that provincial curricula must be better focused and that education programs should engage more with Canadian literature.

I don't think, however, that a national strategy–at least not as suggested–is the solution. For one thing (as Swan points out) the Constitutional division of powers means that education is pretty much guaranteed to remain the purview of the provinces for the foreseeable future. For another thing, I don't think we should be subjecting a new generation of students to what amounts to a nationalistic false consciousness. [All I ever got from The Mountain and the Valley, for example, was a sense of relief that my parents had left the Maritimes shortly before I was born.]

What might work, instead, is some kind of collaborative curricular exchange (whether local, regional or Canada-wide), in which educators, writers and cultural advocates could put together lists of literature that might appeal to various subsets of students. Whether the appeal would be national or purely local is not the point: the intent would be to expose students to various kinds of (Canadian) literature that says something about their own experiences.

I've already put together a reasonably comprehensive list for the Toronto area; I'd love to think something similar might exist (or be developed) for other Canadian cities and regions. The National Library of Canada's Canada: A Literary Tour is one valuable entry point, as are books like Saskatoon Imagined: Art and Architecture in the Wonder City, Storied Streets: Montreal in the Literary Imagination, The Imagined City: A Literary History of Winnipeg and Douglas Coupland's Vancouver Stories.

But improving literary education in Canada should do far more than fixate on physical places. Queer, gender-queer and questing students need access to literary works normalizing their own experiences (good sources might include Here Is Queer: Nationalisms, Sexualities and the Literatures of Canada and the anthologies Queer View Mirror: Lesbian and Gay Short Fiction and Bent On Writing: Contemporary Queer Tales). Aboriginal students deserve access to stories about Native experiences both on and off the reserve (as a person who grew up being told never to talk about my own Aboriginal heritage, it might have helped tremendously to have known about works by Daniel David Moses or Thomas King).

In short, what I'd like to see is a renewed focus not only on Canadian literature but on Canadian literatures –local, engaged, contemporary and diverse.

* I suspect that the reason I was deluged with CanLit in high school was because my teachers had trained during that heady period of nationalistic fervour accompanying the Centennial celebrations in the late 1960s: certainly many of the books we used, tattered paperbacks for the most part, dated from that era.

November 22, 2010

Do Literary Awards Juries Really Hate Toronto?

In this week's NOW Magazine, books columnist Susan G. Cole argues that the regional distribution of this year's Governor General's Literary Awards (which, according to her heuristic, favoured authors from Regina, Saskatoon and Newfoundland) reflects a bias against Toronto.  In particular Cole singles out Ojibway writer Drew Hayden Taylor, suggesting that his novel Motorcycles & Sweetgrass made the shortlist primarily because its author was Aboriginal.

In particular Cole singles out Ojibway writer Drew Hayden Taylor, suggesting that his novel Motorcycles & Sweetgrass made the shortlist primarily because its author was Aboriginal.

Toronto, Cole argues, loses out to the regions because GG Awards juries "want to spread the wealth away from Canada's major cities" where writers, she says, are more likely to "know the right reviewers and influential book page editors." This would be fair enough, Cole concludes, as long as GG awards juries were willing to "cop to it and defend their support for the regions, rather than pretend that they're not taking them into account when they make their decisions."

Do awards juries really hate Toronto? Cole equivocates in her essay, implying that while the Governor General's Awards favour "the regions," they do so in part to distinguish themselves from Giller and Writers' Trust juries, who in her view favour big cities like Toronto and Montreal. As evidence Cole names Johanna Skibsrud, whose Giller-winning novel The Sentimentalists was published by Nova Scotia-based Gaspereau Press but who as an author lives in Montreal (where, presumably, she had opportunities to whisper in the ears of the "right reviewers.")

Other critics are not as ambivalent. In 2002 books columnist Philip Marchand argued that there is a literary conspiracy against  Toronto, claiming that "Everybody hates Toronto [...] and if they're writers they would rather write about Uganda or Bolivia or Manitoba than the city they inhabit." Marchand's views contrast, of course, with those of Stephen Henighan, well known for once having claimed that "TorLit" has largely replaced CanLit and, in a 2006 Geist Magazine essay, adding that Giller Prize winners reflect a Toronto-centred conclave of publishers, booksellers and literary kingmakers.

Toronto, claiming that "Everybody hates Toronto [...] and if they're writers they would rather write about Uganda or Bolivia or Manitoba than the city they inhabit." Marchand's views contrast, of course, with those of Stephen Henighan, well known for once having claimed that "TorLit" has largely replaced CanLit and, in a 2006 Geist Magazine essay, adding that Giller Prize winners reflect a Toronto-centred conclave of publishers, booksellers and literary kingmakers.

Who is right? Do literary awards juries discriminate against Toronto writers? Or are Toronto writers unfairly advantaged by access to publishers and what remains of the Canadian book press.

In the Imagining Toronto book I explore this subject at some length, my interest having been motivated by the vitriol that tends to accompany both positions. I discovered, in contrast to claims GG awards juries have historically discriminated against Toronto, that books set in Toronto won the Governor General's Literary Award more often than has typically been acknowledged, and (in contrast to claims that the Giller reflects a Toronto-based conspiracy) that books set in Toronto have won the Giller Prize only twice in its sixteen year history.

The inference I drew from this research (which focused on where novels were set rather than where their authors lived, providing in my view a more nuanced assessment of literary production in Canada) is that Toronto-focused books win awards no more or less than might be expected. While Toronto has become a centre of literary production in Canada (given that the big publishers and major newspapers are headquartered here), it is by no means the only one, and award-winning (or shortlisted) books set in Saskatchewan and on Curve Lake Ojibway communities are a natural result of this country's literary diversity. Literary awards juries may legitimately be accused of many forms of bias, but there's no evidence Toronto suffers (or gains) as a result.

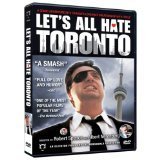

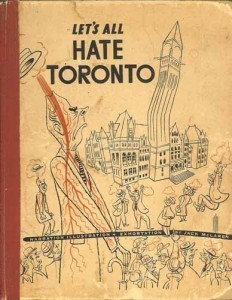

[Images: Albert Nerenberg and Rob Spence's 2007 documentary, Let's All Hate Toronto; and Jack McLaren's illustrated 1956 satire of the same title. Readers interested in literary Toronto-bashing should also check out Lister Sinclair's 1948 radio play "We All Hate Toronto." Chapter 1 of Imagining Toronto references numerous other examples of Toronto-bashing -- including insults published in the city's own literature.]

October 13, 2010

Imagining Toronto Book Launch

The Imagining Toronto book will launch on Tuesday 19 October 2010 at the Boat (258 Augusta Avenue) in Toronto's Kensington Market. Yippee: come out, come out!

This event will also celebrate Mansfield Press' tenth anniversary, and other books launching the same evening will include Leigh Nash's Goodbye, Ukuleke, Peter Norman's At the Gates of the Theme Park, Natasha Nuhanovic's Stray Dog Embassy and Priscila Uppal's Winter Sport: Poems.

If you like, you can join the Imagining Toronto 'page' on Facebook (and RSVP to the launch as well).

October 5, 2010

Behold; the book!

Here's the cover of the Imagining Toronto book, gone to the printers and hopefully back in time for the launch:

The cover (which I love and cannot keep from looking at) was designed by Denis De Klerck on behalf of Mansfield Press. Did I already say I love this cover?

September 25, 2010

Book Sale Bonanza Part I: Victoria College Book Sale

Every September as the season turns my breath quickens in anticipation of the fall book sales at the University of Toronto. Only rarely do I miss a sale, and over the years I've refined my approach. No longer do I go on opening night, when the line-ups are long and there's often an admission charge. Rather, where possible I attend the following morning, when crowds are thinner and the selection of books just as good, particularly in the sections I spend my time browsing.

Right now the Victoria College Book sale is on, running 23-27 September at Old Vic, 91 Charles Street West at the Museum Subway exit (take the stairs to the east side of Queen's Park Crescent, enter any walkway and follow the signs). The books for sale are all donated, and proceeds go to the Victoria University Library at the University of Toronto.

Every year I find so many wonderful books that the biggest challenge is finding a way to transport them all home. In the past it has been possible to strap a big box to my bike, but each of the past three years I've taken my little daughter, who attended her first Vic book sale when she was about six weeks old, strapped sleepily to my chest while I dug into boxes and moiled among the tables. Yesterday we rode the subway down together and walked into Vic with a shared sense of anticipation, mine for Canadian literature and poetry and hers for just about everything.

My big finds this year:

The two-volume Literary History of Canada (second corrected edition, 1976), a set I've wanted for years. This remains the seminal work of Canadian literary criticism in the country's formative years; most often cited is Northrop Frye's Conclusion–an excellent, still highly relevant essay–but The Literary History includes important commentaries abut writers, publishing and literary, including many referencing Toronto.

Maggie Helwig's Because the Gunman (Lowlife Publishing, 1987), another book I've wanted for years (seeing this in a box under one of the tables, I kept digging for long minutes hoping to come across The City on Wednesday, another one of her Lowlife chapbooks I've also long desired). Helwig is such a fantastic poet, novelist and essayist, with such precise vision, that it is impossible not to be drawn into the moral landscapes she crafts.

Doug (who now writes as George, I believe) Fetherling's the united states of heaven / gwendolyn papers / that chainletter hiway (Anansi, 1968). I've never been a big fan of Fetherling's work, but he reflects a critical turning point in Canadian (and Toronto)'s literary development, and the two volumes of his memoirs, Travels by Night and Way Down Deep in the Belly of the Beast, offer illuminating perspectives on the Toronto literary scene during the 1960s and seventies). I suspect many of the poems in this volume are derivative, but they're well enough written and have interesting things to say about Toronto in this era. Interestingly, the author's photo on the back of this book shows him with a copy of T.O. Now: The Young Toronto Poets (1968) another Anansi title in which Fetherling's work appears.

Polyphony: Toronto's People, an anthology of essays about Toronto's neighbourhoods and cultural communities, published in 1984 by the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. This book contains well-crafted snapshot histories of Toronto's cultural history and is a worthwhile addition to the Imagining Toronto Library.

Matt Cohen's Johnny Crackle Sings (McClelland & Stewart, 1971) a novel he derides in his 2000 memoir, Typing: A Life in 26 Keys. This novel is set mainly in Ottawa but was a product of Cohen's struggles to find his feet as a writer in this city.

Evelyn L. Weller's Cardinal Road, a 1955 novel that, as far as I can tell after a quick browse, is a Toronto-set novel about urban social change, suburbanization and immigration. If this is indeed the case, Cardinal Road is rather important as it traces Toronto's suburban growth nearly to its origins and thus becomes a predecessor even of Phyllis Brett Young's seminal 1960 novel The Torontonians. Intriguingly, the novel mentions "Rowanwood" on the first page — significant because Rowanwood gains considerable fictional weight in Young's novel, published five years later. Finding this novel is just one of many reasons I love the Victoria College Book Sale: the volunteers are sufficiently knowledgeable about the literature they sort to place it in an appropriate category. I would never have noticed this book among general literature.

Neil Bissoondath's On the Eve of Uncertain Tomorrows (1990) a collection of short stories, some set in Toronto. Bissoondath is surely one of Canada's most unfairly underappreciated writers (although if I am honest I'll admit that I thought his latest novel, The Soul of All Great Designs, set in Toronto, seemed a bit phoned-in). At his best, Bissoondath is piercing, brutal and elegant all at once, and On the Eve of Uncertain Tomorrows is all these things and more.

Doris Anderson's Rough Layout (McClelland & Stewart, 1981) a novel about a woman working in publishing, written by a woman working in publishing. At some point I'm going to write something about the recursive tendency of authors to write novels about cultural production in Canada. I've already compiled a long list, as it seems to be a bit of a fetish in the literature.

Pearson Gundy's Book Publishing and Publishers in Canada Before 1900, a pamphlet-sized little book published by the Bibliographical Society of Canada in 1964. I've found these sorts of catalogues and commentaries terribly useful in researching the history of Toronto literature, and am glad to add this to the shelves.

Rae Corelli's The Toronto That Used To Be, a 1964 compilation of essays originally appearing in the Toronto Star. This is a neat little book whose depictions of a vanished Toronto are magnified by the realization that the contemporary Toronto Corelli describes, circa 1964, has itself long vanished.

A beautiful little book written and presumably designed by T. Kenneth Gist called Night, published by Coach House in 1972.

And a whole shelf-load of other books, among them Dani Couture's Good Meat (2006), several David Donnells, several Judith Fitzgeralds, Goran Simic's Immigrant Blues (2003), Joe Rosenblatt's Virgins & Vampires (1975), a couple of John Robert Colombo's books of poetry, Susan Helwig's Catch the Sweet (2001), Mad Angels and Amphetamines, featuring among others such Insomniac Press stalwarts as Nik Beat and Matthew Remski, and so on and so forth.

I was a little disturbed, as always, to see new books, including two published in 2010, discarded so quickly. It's my view that if you don't intend to keep or do anything with a book, you probably shouldn't demand a free review copy or slide one into your bag at the launch, as I suspect was the case with both of these books.

At the same time, I am aware that some authors object to people buying their books second-hand, arguing that they do not receive royalties for these books and are thus being ripped off by the purchaser. My response to this is that if someone has paid for the book new , you've already received the royalty for it, and demanding a further payout from a second-hand buyer is akin to usury. Many of the used books I buy are out-of-print, and even where they are not (especially as was the case with the two 2010 books I picked up for $2 and $3 each), they are useful entry points to an author's oeuvre. I try to buy new books by authors I like new and from local, independent booksellers. I have a policy of paying for books, even review copies, received from small presses (although I'm happy to receive free copies from larger ones). In this sense I think book sales of this nature are tremendous ways of keeping literature alive.

And so.

The Victoria College Book sale (on until Monday and apparently on Tuesday you can buy whole boxes of books for $10 each) is only the first salvo in the fall season of book sales. Coming up are the University College Book Sale (15-19 October), the Trinity College Book Sale (22-26 October, Seeley Hall, second floor) and the St. Michael's College book sale (26-30 October in the John M. Kelly Reading Room, 113 St. Joseph Street). Did I miss the Woodsworth College sale? Is it still held? While I was a graduate student at UofT I went there every year and found quite a lot of good Canadian literature and local poetry. Also, coming up later this year (dates to be announced) is the Vanier College Book Sale at York University. Last year I picked up a true first edition of Al Purdy's Poems for All The Annettes (Contact Press) for only a dollar, a tremendous and rare find.

September 17, 2010

Notes on Finishing

After five years of research and three years of writing [interrupted by the birth of my daughter and the death of my father and the ceaseless forward movement of life and work], the Imagining Toronto book is done. All that remains is a little more haggling over the text. And the typesetting, a mysterious process I imagine to be conducted by elves who run rows of type back and forth between ink-stained cases and a manual press. Or maybe that was the dream I had after visiting Mackenzie House.

For nearly a week in the evenings I have wandered through the house looking for something to read. Something that will not require keeping a package of post-it notes handy to mark passages for later reference. Something that will not arouse an urge to add another section to the book, already a bit of a door-stopper. Last night I picked up Janet Lunn's Double Spell, a children's story set in the Beach area of Toronto. A book I had read and loved as a child, but that never made its way into the book. Feeling guilty about this, I set Double Spell aside and instead giggled over Russell Ash and Brian Lake's Bizarre Books: A Compendium of Classic Oddities until I fell asleep.

And this morning. Cool, sunny, September. My husband travels out for a day of teaching; my daughter sleeps in her bed; the cats are fed. And I feel at loose ends. I ache, a little, to turn to other projects I have held in abeyance. But they must wait a little longer. And for the moment I sit here in a kind of suspended animation. The moment of creation; the bullet between the gun and its target; an embryo (also a kind of bullet) floating somewhere in the fallopian tubes. What does a suicide think in the moments after her feet leave the surface of the bridge? Newton must have something to say about this inertia, the moment between an action and its consequence.

Life goes on. Tomorrow I will vacuum, scrub the bathroom, redesign my faculty website, play with our daughter, bike somewhere with my husband, and feel the season turn around us. Undoubtedly I will write: the compulsion is far too deeply ingrained to have any thought of stopping now.

But there is peace here. Trains rumble through the Junction; a blue jay screams in the cedars. My daughter stirs. Hello, she says. Hello, my little girl.