Amy Lavender Harris's Blog, page 5

February 9, 2011

Week 6: The Myth of the Multicultural City

We're back! After last week's snow-related class cancellation, this week in the Imagining Toronto course we'll be discussing the myth of the multicultural city. Among other things, we'll consider whether the myth of the multicultural city is Toronto's 'creation myth,' explore literary representations of racism and cultural exclusion and discuss what role tolerance might play in a city that has made unlikely neighbours of Croations, Serbs, Tamils, Sinhalese, Tutsis, Hutus, Sikhs, Hindus, Turks, Armenians, Greeks, Macedonians, Muslims, Jews and manifold other diasporas. In short, we'll explore whether we can live together without coming to blows — or whether doing so is even possible.

Literary works we'll discuss include Dionne Brand's novel What We All Long For, Farzana Doctor's Stealing Nasreen, Krisantha Bhaggiyadatta's "Race Talk," Earle Birney's "Anglosaxon Street," Austin Clarke's novel More, Rabindranath Maharaj's Homer in Flight, M.G. Vassanji's No New Land and a variety of other works.

Critical works we'll consider will include Stanley Fish's "Boutique Multiculturalism," Slavoj Zizek's "Tolerance as an Ideological Category," Herber Marcuse's "Repressive Tolerance," among others.

This week's lecture slides are available here:

2010-2011 Week 6 slides GEOG 4280 Myth of the Multicultural City

Some additional links:

Falloon, Matt, 5 February 2011. "Multiculturalism has failed in Britain, PM Cameron says." Globe & Mail.

Canadian Multiculturalism Act. 1985, c.24. An Act for the preservation and enhancement of multiculturalism in Canada.

Fish, Stanley, 1987. Boutique Multiculturalism, or why liberals are incapable of thinking about hate speech. Critical Inquiry, 23(2).

February 2, 2011

A Shadow Against the Snow

During a snow squall a few days ago, a great winged thing flew into a high tree behind our house. Too far away to identify, it was nonetheless instantly recognisable as a bird of prey, its flight and landing signaling warning and an almost subconscious trickling of alarm. The starlings that had flashed like motes of dark against the snow vanished; the neighbourhood grew utterly silent. Only the scraping of one branch against another and a sudden drift of snow marked the great bird's departure. Although I was inside the house, my head filled suddenly with the heavy beating of wings.

During a snow squall a few days ago, a great winged thing flew into a high tree behind our house. Too far away to identify, it was nonetheless instantly recognisable as a bird of prey, its flight and landing signaling warning and an almost subconscious trickling of alarm. The starlings that had flashed like motes of dark against the snow vanished; the neighbourhood grew utterly silent. Only the scraping of one branch against another and a sudden drift of snow marked the great bird's departure. Although I was inside the house, my head filled suddenly with the heavy beating of wings.

Every winter we feed a population of starlings, cardinals, sparrows, blue jays, chickadees and finches. The little finches caper at the feeder hanging outside my office window; the larger birds eat what they kick down to the ground. The starlings eat the kibble we put out in the alley for stray cats. Occasionally, on frigid winter days, something the size and shape of a kestrel appears and soon slips away. When crows come, less frequently these days, the smaller birds scold and chase them away. But no birds stayed in the presence of this great bird of prey.

According to an Egyptian legend, Horus, the god of the sky who took the form of a falcon, ruled both the sun and moon. And it is true that on the day this great bird visited us, a weak sun bled itself upon the snow before the full cold moon waxed into fullness that very night. The city lay haunted beneath the shadow of this visitation.

In the morning the great bird returned, closer this time, and I saw that it was a falcon.

The second day of February is considered the turning point toward spring, a moment when we pause to measure the return of light. But this day is also the middle of winter, and spring remains as distant as the fall behind us. And it is hardly a surprise that we measure the day with shadow as well as light. The shape of a storm cloud, the cast of snow against dusk. Or the shadow of a great winged predator in the deep of winter.

[This post was originally published at Reading Toronto in 2007, and is reposted here on Groundhog Day 2011.]

Amy Lavender Harris is the author of Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, 2010).

January 24, 2011

Minding the Word Hoard

In "Five Visits to the Word Hoard," an essay published in Writing Life,[3] Margaret Atwood borrows terminology from Anglo-Saxon poetry to pay homage to the sources of inspiration writers rely on throughout their creative lives. ""The word hoard,"" she writes, "is what they called their well of inspiration, which overlapped with the language itself; and "hoard" signified "treasure." A treasure is kept in a secret, guarded place, and words were seen as a mysterious treasure: they were to be valued."

In "Five Visits to the Word Hoard," an essay published in Writing Life,[3] Margaret Atwood borrows terminology from Anglo-Saxon poetry to pay homage to the sources of inspiration writers rely on throughout their creative lives. ""The word hoard,"" she writes, "is what they called their well of inspiration, which overlapped with the language itself; and "hoard" signified "treasure." A treasure is kept in a secret, guarded place, and words were seen as a mysterious treasure: they were to be valued."

Words are, of course, ultimately difficult to distinguish from their containers, a point Anglo-Saxon scholars make whenever discussing the etymological and cultural significance of the wordhord. Literary scholar Britt Mize,[4] for example, argues that wordhord extends beyond the mental well into the corporeal, cultural–and perhaps even architectural–domains:

A wordhord is not merely a 'collection of words' in the modern sense [...] but the discursive treasury–a container full of that which may be said, or thoughts–that its possessor can onlucan 'unlock' in the act of speech.

In this way, then, a word hoard is found not only a literary lexicon, or the store of ideas–overheard conversations, borrowed memories, accumulated images and cultural artifacts–writers rely on, but also extends to the physical places those ideas are contained. As such, books, bookcases, libraries and archives are also part of the word hoard.

What happens, then, when we lose control of the word hoard; when instead of being a treasure it inundates everything around it, threatening to drown the unwary in an unmanageable volume of words?

When I was in a graduate program a decade or so ago, my supervisor warned me against doing too much reading. "Analysis paralysis" was what he called the state researchers find themselves mired in when they have too many sources and too many ideas to keep track of. Another academic colleague told me she would write down ideas that did not seem to fit with one project and lock them in a desk drawer. In her view the greatest challenge any academic faces is knowing when to stop thinking–and to stop reading–and start writing.

Lately I have been thinking quite extensively about hoarding–and literary hoarding in particular–because I am working on a long story about hoarders, dumpster divers, bottle collectors and urban scavengers. And coincidentally, while reading Alissa York's excellent Toronto novel Fauna (Random House, 2010), I came across a protagonist whose mother had hoarded books:

To begin with, Letty kept her books on shelves like anyone else. On weekends Edal trailed after her through the auction barn or napped fretfully in the passenger seat while Letty trolled the yard sales for "proper wood." By the time she turned eight, her mother had burned through the small savings Nana and Grandpa Adam had left behind, and even a set of used veneer shelves had become a luxury. Letty still slowed for every hand-painted roadside sign, but now all her pennies went on books. [....] Not long after she lost her helper, Letty stopped constructing shelves. The books stood in piles then–Historic Hairstyles of the World, A Guide to Grouting, The Good Earth. Edal grew accustomed to clearing a space when she wanted to open the fridge, or run a bath, or watch one of two stations that came in striped and blurry on their rabbit-eared TV. One afternoon she came upon a Canadian Club box full of Trixie Belden mysteries sitting on the stovetop, directly over the pilot light. I only set them there for a second, Edal. I was coming right back.

I am reminded, too, by Books on Books blogger Nathalie Foy that a book hoarder figures prominently in Martha Baillie's Toronto novel The Incident Report (Pedlar Press, 2009). Baillie's narrator (a librarian, oddly or conveniently enough) is the daughter of a man who hoarded books:

My father did not read the books he collected. Whereas many men drink, he eased his anguish by purchasing books. He imagined that his collection might one day acquire an immense value. Not that he planned to sell his books. [....] Musty volumes stood in piles on the stairs going up to our second floor; they formed a low wall leading to the washroom. Neither the shelves in my parents' bedroom nor those in the living room could contain all my father's books. His collection filled the garage. The car remained parked in the driveway, in every season, no matter the weather. My mother prohibited him from bringing home more books. He hid them under his coat or he waited until she was out of the house.

I read passages like these with a certain discomfort because I also have a tendency to hoard books, and it is only a parallel preference for order that keeps the worst symptoms of this compulsion in check.

Books–and bookstores especially–give me a physical high, and I have an addict's response whenever I am unable to spend most of the time among books. A kind of withdrawal, an internal itch very similar to the one that manifests in my hands whenever I lack the time or space to write. As a child I ran a library–the "Read Alot Library"–out of my bedroom, and inventoried my childhood collection of 200 books in order to make them available for lending. In elementary school my classmates derided me for my ambition (one I am not sure whether I ever expressed or if it was simply imposed upon me) to become a librarian. In my late teens I thought it would be wonderful to amass a complete library consisting of every book (or, later, every Canadian book) ever published and, in my twenties, read with envy a newspaper article about a Canadian university professor whose private library reportedly extended to 25,000 volumes.

But by the time I was twenty-five or so my attraction to books had become slightly more measured. As a graduate student I realised the absurdity of having too many books to find the one needed most urgently. At some point I began to cull a collection of books that had begun to overwhelm my 560 square foot apartment, and although when I met my husband my dowry consisted of nearly 100 boxes of books, it was a smaller collection (around three thousand books) than it had been even a year or two earlier.

I am not sure how many books we have now; perhaps six thousand volumes, hopefully slightly fewer. Since beginning the Imagining Toronto project I have added easily a thousand Toronto-focused books, although at the same time I have culled several hundred novels and poetry anthologies and scholarly books that could no longer justify their keep.

When we cull books they usually end up in boxes on the sidewalk in front of the house, where they are pored and picked over and disappear rapidly. At some point someone appears in an old car and makes away with the rest, which (presumably) end up in a cluttered bookshop or private library.

But I wonder: what is it about the comfort of books that people will endure the clutter and physical discomfort to amass them? For me, collecting books is a compulsion born of curiosity and greed. I am not a good library patron, as I do not often return books on time; as a result it is easier to have them permanently. And as a researcher I like to have my sources close at hand, pages marked (Post-its only; I rarely write in the margins anymore) for easy reference. On a more visceral level I like to have books around me because they are comforting to look at, to smell and touch. They are imprinted on my soul so deeply that when I visit a house without books it seems somehow empty, incompletely furnished.

I know many bibliophiles with large private libraries; also writers with startlingly small collections of books. Pierre Berton reportedly kept his own library to a mere 1500 volumes, a size I find stiflingly small.

But it is easy for a collection to grow too large to be manageable, and the point when this occurs is almost never known until long after the fact. It is possible to wedge books atop other books lined up on the shelves, to double the rows, to create piles on the floor nearby. To stack books along the wall until, in the end, all that is left is a narrow passageway between books. To accumulate so many books that all that is left is to clamber over them.

This was the state I reached while finishing the Imagining Toronto book. My tiny office long since overwhelmed, I moved my laptop to the third floor and begun stacking books on the surfaces around it. For the last several months of writing I would spend up to an hour every few days searching for a book I knew was somewhere in one of those piles, an act guaranteed to produce a seething rage that ruined any prospect of meaningful progress for the rest of the day.

When the book was done, the first thing I did was clear those piles of books. Somehow I managed to fit almost everything (including hundreds of volumes picked up during the process of writing) back into my office. And since then I have redoubled my efforts to cull unwanted books from our collection. Every few days I spend an hour or two poring over the shelves and digging out books to give away. And as much as I love books, the result is a tremendous relief, because the only thing more aesthetically pleasing than a row of books is room for movement and the generation of new ideas.

In this light, it has not seemed a coincidence that I began to make real progress on my long story about hoarders, scavengers and urban outsiders only when my own word hoard had been cleared away.

[Image: Book hoarder gargoyle, available at Gargoyle Statuary.]

Amy Lavender Harris is the author of Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, 2010).

[3] Writing Life: Celebrated Canadian and International Authors on Writing and Life, ed. Constance Rooke, 10-23. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ↩

[4] "The representation of the mind as an enclosure in Old English poetry," in Anglo-Saxon England, Vol. 35: 57-90. ↩

January 18, 2011

Torontoist Reviews the Imagining Toronto Book

Is there not enough Toronto literature — or too much?

Is there not enough Toronto literature — or too much?

That's the upshot of Torontoist's review of Imagining Toronto, accessible here.

My own view, of course, is that no volume of literature, however great, will ever manage completely to distill the essence of a city. As Toronto's Poet Laureate Dionne Brand observed once of Toronto, "The literature is still catching up with the city, with its new stories." And if Torontoist's reviewer finds the volume of literature overwhelming, I'm similarly overwhelmed almost every day when I come across a new novel, poetry collection, memoir or play engaging with Toronto, one I haven't heard of before, one I itch immediately to read. I ache, too, with the knowledge of all the stories that did not make it into the book, whole sections carved out because there was no more room for them.

But I take heart, and hope you will too, in an awareness that the city's literature — like the city itself — expands continuously around us. The universe unfolds, and we unfold with it.

Thank you to Suzannah Showler and Torontoist for taking time to read and review the book!

Want your own copy of Imagining Toronto? The book is available at bookstores everywhere — if possible, please support your local, independent bookstore. You can also order a copy online through Mansfield Press, Chapters/Indigo or Amazon.

[Image: Shelves A-D of the Imagining Toronto Library, 18 January 2011]

Amy Lavender Harris is the author of Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, 2010)

January 12, 2011

Week 2: The City as Text

This week in the Imagining Toronto course we will discuss theoretical and conceptual approaches to the imagined city, including perspectives influences by nineteenth century French poet Charles Baudelaire, essayist Walter Benjamin and (among others) contemporary spatial thinkers Michel Foucault, Henri Lefebvre, Homi Bhabha, Edward Soja, Edward Said and Roland Barthes.

Toronto examples we will explore include city streets like Yonge and Spadina and public spaces such as Union Station, City Hall and the CN Tower.

Lecture slides for today are available here:

2010-2011 Week 2 slides GEOG 4280 The City as Text

The handout for the first reading response assignment is available here:

First Reading Response Assignment GEOG 4280 Winter 2010-2011

January 5, 2011

Welcome to the Imagining Toronto Course

A warm welcome to students enrolled in the Imagining Toronto course (GEOG 4280 3.0) at York University.

For your information, the course syllabus is available to be downloaded here:

Syllabus GEOG 4280 ImaginingToronto 2010-2011

The slides for today's class are available here:

2010-2011 Week 1 slides GEOG 4280 The Imagined City

This week we'll get to know one another and explore the course outline and organizing themes.

In the next few days I'll update the Course section of the website to reflect the new term and material.

P.S. Members of the general public with an interest in the Imagining Toronto project are welcome to follow along in any way you like. Lecture slides and notes will be uploaded each week during the term, which will run until early April. The course is a more formal / scholarly, exploration of themes addressed in the Imagining Toronto book.

Welcome aboard!

January 1, 2011

"It's time. The air is ready. The sky has an opening."

On the first day of the year the cosmos opens and makes room for something new to unfurl. Exactly a decade ago I learned it would make room even for me.

On the first day of the year the cosmos opens and makes room for something new to unfurl. Exactly a decade ago I learned it would make room even for me.

In January of 2007 I tried to articulate this sense of unfolding, describing the year in terms of its temporal cartography.

"In the dark shortly before dawn, I learn to remember the new year's colour, which is a smoky, almost blue shade, the colour of a Siamese cat.

The year travels in two directions. Within itself, the year has already crested and now glides down the long slope that broadens out like an alluvial plain toward spring. Beyond itself, the year rises into the millennium, which darkens as it will for several years before becoming light again. This is not a prediction of difficulty; it is merely a description of the geometry of time.

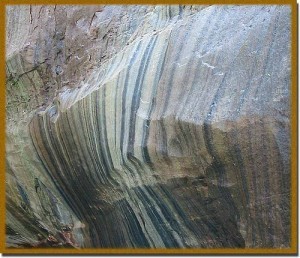

A personal description and a private geometry, I might add, although apparently research has found patterns in even this kind of  conceptual synaesthesia, reporting that chronologies tend to be linear or otherwise coherently organized. A prosaic description, perhaps, of the cognitive tricks we all employ to orient, understand, and remember. But synaesthetic mappings occur beyond the level of metaphor or cognitive convenience. And, perhaps not unlike like Blake's wheel or Yeats' gyre, my map of time flows outward and upward. But its recursions are not spiral; they are limnological, like sediment layers under a still lake, or like geological formations laid down across epochs. And, in the same way that a paleontologist might survey a stony landscape seeking evidence of the organic past, it is possible to read these temporal landscapes looking for patterns and discontinuities across time and space."

conceptual synaesthesia, reporting that chronologies tend to be linear or otherwise coherently organized. A prosaic description, perhaps, of the cognitive tricks we all employ to orient, understand, and remember. But synaesthetic mappings occur beyond the level of metaphor or cognitive convenience. And, perhaps not unlike like Blake's wheel or Yeats' gyre, my map of time flows outward and upward. But its recursions are not spiral; they are limnological, like sediment layers under a still lake, or like geological formations laid down across epochs. And, in the same way that a paleontologist might survey a stony landscape seeking evidence of the organic past, it is possible to read these temporal landscapes looking for patterns and discontinuities across time and space."

Four years later, as 2011 unfurls and emits a nearly translucent light, I try to remember who I was when I wrote those words.

In January of 2007 I knew the Imagining Toronto project would become a book. I did not know how such a thing would happen but I believed verily that the universe would unfold, that room would be made for the idea to spill itself upon some open field.

In January of 2007 I also knew I would bear a child. In truth this desire had resided quietly in my person for many years, but in 2007 it began to flesh out and take on a visible form.

These two things are inextricably linked in my mind, and I do not think it a coincidence that I became pregnant near the end of 2007, less than a month after being contracted to write the Imagining Toronto book. The grace of the timing was this: that after a period of dogged persistence both projects took on a trajectory almost entirely of their own. The word became flesh and took breath and lived.

But all these things became possible only after 2000, the year I shrugged off the final fragments of shell and outgrew my embryonic form. I began to move freely in the world. For some time I had thought of myself as waiting, but early that year I realized I had been paying close attention to currents in the atmosphere. At the time I wrote, "I have been listening for such a long time, and now I am learning to speak."

In February of 2000 I bought a paperback edition of American poet Mark Strand's Pulitzer Prize-winning Blizzard of One. For several months I had carried around a newspaper clipping announcing the honour, describing Strand's Maritime origins and introducing a single poem from the collection: "Blizzard of One." It is a poem I cannot read even now without weeping, so aptly it did–and does– express the sense of opening I felt (and continue to feel) in my own life. The sense of waiting for something to take form, and being ready to notice it when it does.

"That's all / There was to it," Strand writes: "No more than a solemn waking / To brevity, to the lifting and falling away of attention [...] Except for the feeling that this piece of the storm, / Which turned into nothing before your eyes, would come back, / That someone years hence, sitting as you are now, might say: "It's time. The air is ready. the sky has an opening."

It is now 2011, and the Imagining Toronto book is finished. It is in print. And it is a good book, in the sense that faith and effort and love may produce something capable of emitting its own light.

And my little daughter, whose name means "pure light," who moves and speaks and makes her own way into the world: she too is a product of that same opening.

And at the beginning of this brave new year, as a new set of projects begins to take shape, I listen to the atmosphere and make ready to make my way into this new opening.

[The top image was created by 00dann. The sediment image was created by Andrew Eick . Both images are used under the aegis of a Creative Commons license. The lines of Mark Strand's poetry are drawn from "A Piece of the Storm," published in Blizzard of One (Knopf, 1998).]

December 31, 2010

Toronto Books You Should Read Part II: 77 Essential Non-Fiction Reads

In the first part of the "Toronto Books You Should Read" series I introduced 100 literary works that are essential reading for anyone interested in the imagined city. In the second part, presented herewith, I list 75 77 non-fiction books about Toronto that should form part of every Torontophile's reading library.

In researching and writing the Imagining Toronto book I learned beyond any doubt that it was not enough simp ly to read literature set in the city: it was also imperative to understand the full range of social, spatial, economic and ecological processes that have shaped Toronto. As a result, I also began to read and amass a library of non-fiction works engaging with the city. Among the books listed below are some sources that played critical roles in shaping the book, as well as my perceptions of Toronto.

ly to read literature set in the city: it was also imperative to understand the full range of social, spatial, economic and ecological processes that have shaped Toronto. As a result, I also began to read and amass a library of non-fiction works engaging with the city. Among the books listed below are some sources that played critical roles in shaping the book, as well as my perceptions of Toronto.

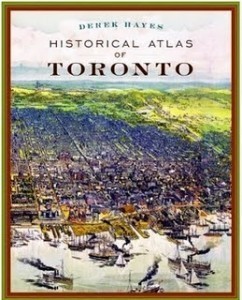

I have favourites, of course, among them Matthew Hayes' fantastically beautiful Historical Atlas of Toronto and Percy Robinson's excellent Toronto During the French Regime (a rare example of accessible history and the best book I have come across on Toronto prior to 1800; not to mention an important source in my next project). I'm also fond of Robert Thomas Allen's When Toronto Was For Kids, a sort of memoir about a Toronto that has nearly vanished from memory.

This list isn't the complete story of Toronto, of course: I maintain a much larger database of non-fiction works engaging with Toronto here, and many of these (and other) works make an appearance in Imagining Toronto. I'm always interested in hearing about new sources, so if you would like to suggest additions (here or to the Library itself), I'll be happy to hear about them.

Please note that while the list is numbered, it is not meant to convey any order of importance. I've also listed my own book here, and hope personal vanity will be excused.

Architecture and Urban Design

1. William Dendy, 1993. Lost Toronto (McClelland & Stewart, 1993).

2. Margaret Goodfellow and Phil Goodfellow, A Guidebook to Contemporary Architecture in Toronto (Douglas & McIntyre, 2010).

3. Michael McClelland and Graeme Stewart (eds.), Concrete Toronto: A Guide to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies (Coach House, 2007).

4. Osbaldeston, Mark, Unbuilt Toronto: A History of the City That Might Have Been (Dundurn, 2008).

5. John Sewell, The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning (University of Toronto Press, 1993).

Art and Cultural Production

6. Don Cullen, The Bohemian Embassy: Memories and Poems (Wolask & Wynn, 2007).

6. Don Cullen, The Bohemian Embassy: Memories and Poems (Wolask & Wynn, 2007).

7. Edith Firth, Toronto in Art: 150 Years Through Artists' Eyes (Fitzhenry & Whitside in cooperation with the City of Toronto, 1983).

8. Amy Lavender Harris, Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, 2010).

9. Geoff Pevere (ed.), Toronto On Film (Toronto International Film festival, 2009).

10. John Warkentin, Creating Memory: A Guide to Outdoor Public Sculpture in Toronto (Becker Associates / The City Institute at York University, 2010).

11. Alana Wilcox, Christina Palassio, and Jonny Dovercourt (eds.), The State of the Arts: Living with Culture in Toronto (Coach House, 2006).

12. Liz Worth, Treat Me Like Dirt: An Oral History of Punk in Toronto and Beyond, 1977-1981 (Bongo Beat, 2009).

Heritage and History

13. Robert Thomas Allen, When Toronto was for Kids (McClelland & Stewart, 1961).

14. Carl Benn, Historic Fort York: 1793-1993 (Natural Heritage / Natural History, 1993).

15. Frank A. Dieterman and Ronald F. Williamson, Government On Fire: The History and Archaeology of Upper Canada's First Parliament Buildings (eastendbooks, 2001).

16. Mike Filey, Toronto Sketches Volumes 1-9. Toronto: Dundurn. [Although I must note that the terrible typesetting and un-illuminating essay titles irk me considerably.]

17. Sally Gibson, Inside Toronto: Urban Interiors, 1880-1920 (Cormorant, 2006).

18. Derek Hayes, Historical Atlas of Toronto (Douglas & McIntyre, 2008).

19. Eric Wilfrid Hounsom, Toronto In 1810 (Ryerson, 1970).

20. Kilbourn, William, 1984. Toronto Remembered. Toronto: Stoddart.

21. Michael Kluckner, Toronto The Way It Was (Whitecap Books, 1988).

22. Steve MacKinnon, Karen Teeple & Michele Dale, Toronto's Visual Legacy: Official City Photography from 1856 to the Present (James Lorimer & Company, 2009).

23. J. Ross Robertson, The Diary of Mrs. John Graves Simcoe, Wife of the First Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Upper Canada, 1792-6 (Coles, 1973). facsimile edition.

24. Percy J. Robinson, Percy J., Toronto During the French Regime, 1615-1793 (University of Toronto Press, 1933; 1965).

25. Henry Scadding, [edited and abridged by Frederick H. Armstrong], Toronto of Old (Dundurn, 1987).

26. Ronald F. Williamson (ed.), Toronto: An Illustrated History of its First 12,000 Years (James Lorimer & Company, 2008).

Multicultural Toronto

27. Paul Anisef and Michael Lanphier (eds.), The World in a City (University of Toronto Press, 2003).

28. Frances Henry, The Caribbean Diaspora in Toronto (University of Toronto Press, 1994).

29. Franca Iacovetta, Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003).

30. Cyril Levitt and William Shaffir, The Riot at Christie Pitts (Key Porter Books, 1987).

31. Stephen A. Speisman, The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937 (McClelland & Stewart, 1979).

32. Carlos Teixeira and Victor M.P. Da Rosa (eds.), The Portuguese in Canada: Diasporic Challenges and Adjustment. (University of Toronto Press, 2009).

33. Richard H. Thompson, Toronto's Chinatown: The Changing Social Organization of An Ethnic Community (AMS Press, 1988).

34. John E. Zucchi, Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875-1935 (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988).

Nature and Environment

35. Nick Eyles, Toronto Rocks: The Geological Legacy of the Toronto Region (Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2004).

35. Nick Eyles, Toronto Rocks: The Geological Legacy of the Toronto Region (Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2004).

36. Wayne Grady, Toronto The Wild (Macfarlane, Walter & Ross, 1995).

37. Wayne Reeves Christina Palassio (eds.), HTO: Toronto's Water from Lake Iroquois to Lost Rivers to Low-Flow Toilets (Coach House, 2008).

38. Charles Sauriol, Remembering the Don (Amethyst, 1981), Tales of the Don (Natural Heritage, 1984), A Beeman's Journey (Natural Heritage, 1984), Green Roots: Recollections of a Grassroots Conservationist (Hemlock, 1991), Trails of the Don (Hemlock, 1992), Pioneers of the Don (1995).

39. Murray Seymour, Toronto's Ravines: Walking The Hidden Country (Boston Mills, 2000).

40. Alana Wilcox, Christina Palassio and Jonny Dovercourt (eds.), 2007. GreenTOpia: Towards a Sustainable Toronto (Coach House, 2007).

People

41. William Burrill, Hemingway: The Toronto Years (Doubleday, 1994).

41. William Burrill, Hemingway: The Toronto Years (Doubleday, 1994).

42. John Davidson / Laird Stevens, The Stroll: Inner-City Subcultures (NC Press, 1986).

43. Joe Fiorito, Union Station: Love, Madness, Sex and Survival on the Streets of the New Toronto (McClelland & Stewart, 2006).

44. James FitzGerald, What Disturbs our Blood: A Son's Quest to Redeem the Past (Random House of Canada, 2010).

45. W.E. Mann (ed.), The Underside of Toronto (McClelland & Stewart, 1970).

46. Richard Poplak, KENK: A Graphic Portrait (Pop Sandox, 2010).

47. Kenneth H. Rogers, Street Gangs in Toronto: A Study of the Forgotten Boy (Ryerson, 1945).

Places and Neighbourhoods

48. F.R. Berchem, The Yonge Street Story, 1793-1860 (McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1977).

49. Jack Batten, The Annex: The Story of a Toronto Neighbourhood (Boston Mills Press, 2004).

50. Robert R. Bonis, (ed.), A History of Scarborough (Scarborough Public Library, 1968).

51. Jon Caulfield, City Form and Everyday Life: Toronto's Gentrification and Critical Social Practice (University of Toronto Press, 1994).

52. Jean Cochrane, Jean; photographs by Vincenzo Petropaolo, Kensington (Boston Mills / Stoddart, 2000).

53. Penina Coopersmith, Cabbagetown: The Story of a Victorian Neighbourhood (James Lorimer, 1998).

54. Stuart Henderson, Making the Scene: Yorkville and Hip Toronto in the 1960s (University of Toronto Press, forthcoming spring 2011).

55. Denis De Klerck and Corrado Paina (eds.), College Street, Little Italy: Toronto's Renaissance Strip (Mansfield Press, 2006).

56. Rosemary Donegan, Spadina Avenue. (Douglas & McIntyre, 1985).

57. Robert Fulford, Accidental City: The Transformation of Toronto. Boston (Peter Davidson / Houghton Mifflin, 1996).

58. Sally Gibson, More Than An Island: A History of the Toronto Island (Irwin, 1974).

59. James Lorimer and Myfanwy Phillips, Working People: Life in a Downtown City Neighbourhood (James Lewis & Samuel Ltd, 1971).

60. Macfarlane, David, ed., 2008. Toronto: A City Becoming. Toronto: Key Porter.

61. Albert Rose, Regent Park: A Study in Slum Clearance (University of Toronto Press, 1958).

62. Carolyn Whitzman, Suburb, Slum, Urban Village: Transformations in Toronto's Parkdale Neighbourhood, 1875-2002. (University of British Columbia Press, 2009).

63. Lorraine O'Donnell Williams, Memories of the Beach: Reflections on a Toronto Childhood (Dundurn, 2010).

64. Leonard Wise and Allan Gould, Toronto Street Names: An Illustrated Guide To Their Origins (Firefly, 2000).

Politics and Governance

65. Julie-Anne Boudreau, Roger Keil and Douglas Young, Changing Toronto: Governing Urban Neoliberalism (University of Toronto Press, 2009).

66. Pier Giorgio Di Cicco, Municipal Mind: Manifestos for the Creative City (Mansfield Press, 2007).

66. Pier Giorgio Di Cicco, Municipal Mind: Manifestos for the Creative City (Mansfield Press, 2007).

67. Jason McBride and Alana Wilcox (eds.), Utopia: Towards a New Toronto (Coach House, 2005).

68. Dave Meslin, Christina Palassio and Alana Wilcox (eds.), Local Motion: The Art of Civic Engagement in Toronto (Coach House, 2010).

69. John Sewell, John, Up Against City Hall (James Lewis & Samuel, 1972).

Psychogeography

70. Sean Micaleff, Stroll (Coach House, 2010).

71. Ninjalicious, Access All Areas: A User's Guide to the Art of Urban Exploration (Infiltration / Coach House, 2005).

72. John Bentley Mays, Emerald City: Toronto Visited (Viking, 1994).

Suburbs

73. S.D. Clark, The Suburban Society. Toronto (University of Toronto Press, 1966).

74. Richard Harris, Unplanned Suburbs: Toronto's American Tragedy, 1900 to 1950 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

75. John R. Seeley, R. Alexander Sim and Elizabeth W. Loosley, Crestwood Heights: A Study of the Culture of Suburban Life (Basic Books / Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968).

76. Sewell, John, The Shape of the Suburbs: Understanding Toronto's Sprawl (University of Toronto Press, 2009).

77. Lawrence Solomon, Toronto Sprawls (University of Toronto Press, 2007).

Amy Lavender Harris is the author of Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, 2010).

December 28, 2010

100 Toronto Books You Should Read

As the BBC's list of the UK's best loved 100 novels makes its tedious way around the internet more than seven years after BBC listeners voted for their favourite books, readers continue to measure their own literary prowess against the list. One meme that regularly makes rounds on social networking sites is a similar list headlined by the claim that "the BBC believes the majority of people will have only read 6 of the 100 books here."

A number of commentators have pointed out (1) that the BBC appears never to have made such a claim, (2) the list varies (sometimes widely) from one incarnation to the next, (3) the list is quite Anglo-centric and (4) that (among other things) participants tend to exaggerate the works they have read (the 'works of William Shakespeare,' for example, is a far longer list than many people think, and James Joyce's Ulysses a longer and more complicated novel than many readers seem to recall).

In truth there are dozens of "100 books you must read or die a Philistine" lists out there. While some of them are fun to read (or measure your own reading against), they are typically limited by some fatal combination of patronizing elitism and cultural narrowness.

As an alternative, I present herewith a list of the top 100 Toronto books you should read. Please feel welcome to share this list around, highlighting your own reads and perhaps mentioning somewhere that the TLC (Toronto Literary Committee) believes the majority of Torontonians won't have read more than six of these books. Are you elite enough to have read more?

The Toronto Canon

1. Margaret Atwood, The Edible Woman (or any of Atwood's other Toronto novels)

2. Robertson Davies, The Rebel Angels (other Davies novels set mainly in Toronto accepted)

3. Timothy Findley, Headhunter

4. Hugh Garner, Cabbagetown (1968 Ryerson Press edition as well as the 1950 White Circle abridged version)

5. Dennis Lee, Civil Elegies

6. Gwendolyn MacEwen, Noman's Land

7. Anne Michaels, Fugitive Pieces

8. bpNichol, The Martyrology Book V

9. Michael Ondaatje, In the Skin Of A Lion

10. Josef Skvorecky, The Engineer of Human Souls

11. Earle Birney, Down The Long Table

12. Augustus Bridle, Hansen: A Novel Of Canadianization

13. Morley Callaghan, Strange Fugitive

14. Henry Kreisel, The Rich Man

15. Wyndham Lewis, Self-Condemned

16. Joyce Marshall, Lovers and Strangers

17. George F. Millner, The Sergeant of Fort Toronto

18. Ernest Thompson Seton, Wild Animals I Have Known (bonus point for Two Little Savages)

19. Patrick Slater, The Yellow Briar

20. Phyllis Brett Young, The Torontonians

New Classics

21. Dionne Brand, What We All Long For

22. Catherine Bush, Minus Time

23. Barbara Gowdy, Falling Angels (or Mister Sandman or The Romantic or Helpless)

24. Maggie Helwig, Girls Fall Down

25. Rabindranath Maharaj, The Amazing Absorbing Boy

26. Darren O'Donnell, Your Secrets Sleep With Me

27. Michael Redhill, Consolation

28. Emily Schultz, Heaven Is Small

29. Russell Smith, How Insensitive (or Noise or Muriella Pent)

30. Alissa York, Fauna

Poetry

[in addition to works of poetry included elsewhere in this list]

31. Margaret Avison, Momentary Dark (also Concrete and Wild Carrot)

31 1/2. Ronna Bloom, Public Works

32. Dionne Brand, Thirsty

33. Alice Burdick, Simple Master

34. Lynn Crosbie, Queen Rat: New and Selected Poems

35. Rishma Dunlop, Metropolis

36. Maggie Helwig, Talking Prophet Blues

37. Daniel Jones, the brave never write poetry

38. Gwendolyn MacEwen, Afterworld

39. Stuart Ross, Razovsky At Peace

40. Raymond Souster, Collected Poems Volumes 1-10

The City of Neighbourhoods

41. Sarah Dearing, Courage My Love

42. Claudia Dey, Stunt

43. Cory Doctorow, Someone Comes To Town, Someone Leaves Town

44. Katherine Govier, Fables of Brunswick Avenue

45. Helen Humphreys, Leaving Earth

46. Don Lyons, Yorkville Diaries

47. Katrina Onstad, How Happy To Be

48. Ted Plantos, The Universe Ends at Sherbourne and Queen

49. Ray Robertson, Moody Food

50. George F. Walker, The East End Plays (Criminals In Love, Better Living and Beautiful City)

Culture and Identity

51. Gordon Stewart Anderson, The Toronto You Are Leaving

52. Joseph Boyden, Born With a Tooth

53. David Chariandy, Soucouyant

54. Austin Clarke, More (or his 'Toronto trilogy:' The Meeting Point, Storm of Fortune and The Bigger Light)

55. Farzana Doctor, Stealing Nasreen

56. Odimumba Kwamdela, Niggers This Is Canada

57. Rabindranath Maharaj, Homer In Flight

58. Richard Scrimger, Crosstown

59. Antanas Sileika, Buying On Time

60. M.G. Vassanji, No New Land

Genre Fiction

61. Kelley Anderson, Bitten

62. Rosemary Aubert, Firebrand

63. Linwood Barclay, Bad Move

64. Pat Capponi, Last Stop Sunnyside

65. Nalo Hopkinson, Brown Girl In The Ring (eagerly awaited: her forthcoming novel, tentatively titled T'Aint)

66. Tanya Huff, Blood Price (or any other of Huff's Blood series. Bonus point for Gate of Darkness, Circle of Light)

67. Maureen Jennings, Poor Tom Is Cold (or any other of her Murdoch Mysteries)

68. John McFetridge, Dirty Sweet or Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere

69. Robert Rotenberg, Old City Hall

70. Robert Charles Wilson, The Perseids and Other Stories

Children's Books

71. Ramabai Espinet (illustrated by Veronica Sullivan), The Princess of Spadina

72. Cary Fagan, The Market Wedding

73. Zelda Freedman, Rosie's Dream Cape

74. Bernice Thurman Hunter, That Scatterbrain Booky (see also With Love From Booky and As Ever Booky)

75. Teddy Jam (Matt Cohen; illustrated by Eric Beddows), Night Cars

76. Dennis Lee (illustrated by Frank Newfeld), Alligator Pie

77. Robert Munsch (illustrated by Michael Martchenko), Jonathan Cleaned Up–Then He Heard A Sound; or; Blackberry Subway Jam

78. Barbara Nichol, Dippers

79. Barbara Reid, The Subway Mouse

80. Joan Schwartz and Matt Beam, City Alphabet

Anthologies

81. Janine Armin and Nathaniel G. Moore (eds.), Toronto Noir

82. Barry Callaghan (ed.), This Ain't No Healing Town: Toronto Stories

83. Lynn Crosbie and Michael Holmes (eds.), Plush

84. Cary Fagan and Robert MacDonald (eds.), Streets of Attitude: Toronto Stories

85. William Kilbourn, The Toronto Book

86. Dennis Lee (ed.), T.O. Now: The Young Toronto Poets

87. Caroline Morgan Di Giovanni (ed.), Italian Canadian Voices: A Literary Anthology,  1946-2004

1946-2004

88. Karen Richardson & Steven Greed (eds.) T-Dot Griots: An Anthology of Toronto's Black Storytellers

89. Helen Walsh (ed.), TOK: Writing The New Toronto, Volumes 1-5

90. Dennis Wolfe and Douglas Daymond (eds.), Toronto Short Stories

Unforgettable but Uncategorizable

91. Ansara Ali, The Sacred Adventures of a Taxi Driver

92. Hedi Bouraoui, Thus Speaks The CN Tower

93. Juan Butler, The Garbageman

94. Daniel Jones, 1978

95. Crad Kilodney, Excrement (see also Putrid Scum)

96. Bryan Lee O'Malley, Scott Pilgrim, Volumes I-VI.

97. Annie G. Savigny, A Romance Of Toronto

98. John Reid, The Faithless Mirror

99. Jarvis Warwick (Hugh Garner), Waste No Tears

100. Scott Symons, Civic Square

Amy Lavender Harris is the author of Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, fall 2010).

December 14, 2010

Pickle Me This Reviews the Imagining Toronto Book

Writer and book critic Kerry Clare of Pickle Me This has written the most wonderful review imaginable of the Imagining Toronto book, describing it as

one of the best books I've read this year, blowing my mind with its gorgeous prose, fascinating facts, stunning narrative, and sheer readability

and adding

Harris has not merely written a book about Toronto, but she has written the city itself

Click here to read the full review. [Image property of Pickle Me This]

Update: Librarian Deborah Black also gives the book a nod at her blog, Humming in the Night, describing Imagining Toronto as "[a] highly recommended book that should not only appeal to those who know the city of Toronto in Ontario but those who know that in a city's streets and buildings lies memory and imagination."