Nerine Dorman's Blog, page 36

December 30, 2017

Alive Again by Andre Eva Bosch

Alive Again by Andre Eva Bosch was a review copy that fell on my desk, so it's not necessarily a book I would have chosen to read myself, but in the spirit of fairness, I'll give this winner of the 2013 Sanlam Youth Literature Prize my best.

Alive Again tells us the story of Nandi, a bright young girl who grows up in KaNyamazane township. Her mother is a cook by profession, and her father appears to be largely absent – doing manual labour. Her parents couldn't be more different. Her mum believes that her children should have a good education so that they can be the best that they can be, while her father is an embittered man prone to violent outbursts. (It's this strong dualistic divide between good/bad attitudes in the parents that did grate on me a bit.)

Alive Again tells us the story of Nandi, a bright young girl who grows up in KaNyamazane township. Her mother is a cook by profession, and her father appears to be largely absent – doing manual labour. Her parents couldn't be more different. Her mum believes that her children should have a good education so that they can be the best that they can be, while her father is an embittered man prone to violent outbursts. (It's this strong dualistic divide between good/bad attitudes in the parents that did grate on me a bit.)

Nandi harbours dreams of becoming a human rights lawyer, so she works hard towards that dream, supported by her friend Maryke and her Special Boy Bheka. And the friendships between the youngsters is all quite charming, and the budding romance is a lovely counterpoint to the Terrible Thing that Happens. I won't say more for fear of spoilers, but I'm sure savvy folks will be able to read between the lines and figure out what topic I'm skirting around.

Bosch's writing flows well and is most certainly accessible, and it's easy to see why the judges liked this story – despite the tendency to indulge in exposition, there is well-defined narrative: Despite the absolute awfulness of The Terrible Thing, this is a tale about hope and about being strong in the face of incredible adversity. Love conquers all, and all that. But. (There is going to be a "but" for those who know me well.) I personally felt that this novel verged on being too didactic and the development of the characters could have had more nuance when I compare this to novels in a similar genre. The style of the narrative is very much like a memoir, so there is more focus on Nandi's feelings and less on direct and indirect characterisation, so layering felt a bit glossed over, and there could have given a little more friction between characters as one would find in real life. As it is, the antagonist's motivations for their actions feels almost left of field, even if they are painted out from the get-go for being a horrible person. (So in that sense they're a bit two-dimensional and even though some sort of historical basis is given to justify their actions, it still didn't ring quite true with me.)

I give that it's beyond the scope of the novel to delve too deeply into the darker aspects of the plot, but even that to me felt as if it had almost been brushed off. Granted, I suspect this story was written with the motive for providing a role model for girls who might be in a similar situation, so the transformative aspects that hinge on the Terrible Thing are focused on rather than the negative aspects. (Hence me maintaining my feeling that this story is didactic in nature – the author stating clearly about "universal messages" in the foreword is a dead giveaway, in my opinion.) I'm not certain how young readers might feel about reading a book that's been set up to deliver such an overt message. I guess that's up to individual readers, and I feel that as a devoted reader, I'm a little leery of authors who employ certain devices to progress character development and sound clarion calls for hope and courage, even if their motives come from a good place.

I can well imagine this book may be stocked in school libraries or gifted to young readers who may be in need of a bit of inspirational literature. But if you've got a teen who's into their action-packed Harry Potters and Percy Jacksons, then maybe steer clear and try to find something more to their tastes.

Alive Again tells us the story of Nandi, a bright young girl who grows up in KaNyamazane township. Her mother is a cook by profession, and her father appears to be largely absent – doing manual labour. Her parents couldn't be more different. Her mum believes that her children should have a good education so that they can be the best that they can be, while her father is an embittered man prone to violent outbursts. (It's this strong dualistic divide between good/bad attitudes in the parents that did grate on me a bit.)

Alive Again tells us the story of Nandi, a bright young girl who grows up in KaNyamazane township. Her mother is a cook by profession, and her father appears to be largely absent – doing manual labour. Her parents couldn't be more different. Her mum believes that her children should have a good education so that they can be the best that they can be, while her father is an embittered man prone to violent outbursts. (It's this strong dualistic divide between good/bad attitudes in the parents that did grate on me a bit.)Nandi harbours dreams of becoming a human rights lawyer, so she works hard towards that dream, supported by her friend Maryke and her Special Boy Bheka. And the friendships between the youngsters is all quite charming, and the budding romance is a lovely counterpoint to the Terrible Thing that Happens. I won't say more for fear of spoilers, but I'm sure savvy folks will be able to read between the lines and figure out what topic I'm skirting around.

Bosch's writing flows well and is most certainly accessible, and it's easy to see why the judges liked this story – despite the tendency to indulge in exposition, there is well-defined narrative: Despite the absolute awfulness of The Terrible Thing, this is a tale about hope and about being strong in the face of incredible adversity. Love conquers all, and all that. But. (There is going to be a "but" for those who know me well.) I personally felt that this novel verged on being too didactic and the development of the characters could have had more nuance when I compare this to novels in a similar genre. The style of the narrative is very much like a memoir, so there is more focus on Nandi's feelings and less on direct and indirect characterisation, so layering felt a bit glossed over, and there could have given a little more friction between characters as one would find in real life. As it is, the antagonist's motivations for their actions feels almost left of field, even if they are painted out from the get-go for being a horrible person. (So in that sense they're a bit two-dimensional and even though some sort of historical basis is given to justify their actions, it still didn't ring quite true with me.)

I give that it's beyond the scope of the novel to delve too deeply into the darker aspects of the plot, but even that to me felt as if it had almost been brushed off. Granted, I suspect this story was written with the motive for providing a role model for girls who might be in a similar situation, so the transformative aspects that hinge on the Terrible Thing are focused on rather than the negative aspects. (Hence me maintaining my feeling that this story is didactic in nature – the author stating clearly about "universal messages" in the foreword is a dead giveaway, in my opinion.) I'm not certain how young readers might feel about reading a book that's been set up to deliver such an overt message. I guess that's up to individual readers, and I feel that as a devoted reader, I'm a little leery of authors who employ certain devices to progress character development and sound clarion calls for hope and courage, even if their motives come from a good place.

I can well imagine this book may be stocked in school libraries or gifted to young readers who may be in need of a bit of inspirational literature. But if you've got a teen who's into their action-packed Harry Potters and Percy Jacksons, then maybe steer clear and try to find something more to their tastes.

Published on December 30, 2017 00:12

December 29, 2017

Red Seas Under Red Skies by Scott Lynch

Anyone who finishes Red Seas Under Red Skies by Scott Lynch (book #2 of his Gentleman Bastard series) will understand why I muttered, “Damn it, Locke” under my breath when I reached the end of the book. As always, Lynch weaves a convoluted tale, filled with double crossings after double crossings, until unwary readers may go quite squint trying to keep up with things. And trust me when I say there were times during this novel that I wondered whether a) things could get any worse and b) how the heck the two friends were going to get out of their predicament. Which kept me turning pages, so I guess that’s half the author’s work done right there.

I will add that Lynch is one of the few fantasy authors who, in my mind, can get away with writing the kind of shallow third verging on omniscient point of view that he does. He sometimes skates dangerously close to withholding key information, but the break-neck speed of his telling at key moments means that even when he does neglect to share what Locke or Jean knows, he usually shows the rest of his hand soon enough after. So I forgive him. However I will state this much: I am difficult to please when it comes to omniscient third because so few authors get it right. Lynch gets around this by having short sub-sections per chapter, so that he cycles through characters’ points of view as and when it’s necessary, but every once in a while the author-narrator intrudes.

I will add that Lynch is one of the few fantasy authors who, in my mind, can get away with writing the kind of shallow third verging on omniscient point of view that he does. He sometimes skates dangerously close to withholding key information, but the break-neck speed of his telling at key moments means that even when he does neglect to share what Locke or Jean knows, he usually shows the rest of his hand soon enough after. So I forgive him. However I will state this much: I am difficult to please when it comes to omniscient third because so few authors get it right. Lynch gets around this by having short sub-sections per chapter, so that he cycles through characters’ points of view as and when it’s necessary, but every once in a while the author-narrator intrudes.

For fear of spoilers, I’m not going to go into a general overview of the novel, suffice to say that it starts out with Locke and Jean planning the heist to end all heists – a job that’s two years in the making as they execute their designs of the aptly named Sinspire gaming house.

The environment in which they find themselves is decadent to say the least, and I lapped up the descriptions of the people. Lynch’s world building is intricate and layered, and I’ll hazard to say that nearly every small detail is important – so take note. He does a lot of foreshadowing to get around the fact that he doesn’t immediately clue you in with the full details. You’ll know something is afoot, but not much more than that until he reveals.

Also, I went into this novel expecting one thing, and about halfway through Lynch pulled the rug from under my feet and the kind of story I thought I would be reading turned out to be something completely different. I won’t say what, but it was awesome, and fun, and he introduced me to some unforgettable characters.

Damn it, Lynch. There is The Thing that happens near the end. I won’t say what but I was gutted. Not quite to the degree that I am reading Robin Hobb, but pretty darned close. And that’s all I will say on the matter.

Getting into Red Seas Under Red Skies was not immediate, as it felt to me that there was quite a bit of setting up that happened before the story really got underway. Lynch’s style isn’t for everyone, nor is the subject matter – focus is very much on action rather than emotional layering, which he keeps close to his chest. But once I got going, I was invested, and that’s what counts. I really do love the dynamics between Locke and Jean, even if the novel tends to stagger around unexpectedly. The worst part is that I finished reading the novel while on holiday in an area where I had to walk 1km to just get cellphone signal, so at the time I couldn’t go google to see whether there’s another novel to follow up this one… Yeah, it was that sort of book. (And there are more in the series… so I’m happy)

I will add that Lynch is one of the few fantasy authors who, in my mind, can get away with writing the kind of shallow third verging on omniscient point of view that he does. He sometimes skates dangerously close to withholding key information, but the break-neck speed of his telling at key moments means that even when he does neglect to share what Locke or Jean knows, he usually shows the rest of his hand soon enough after. So I forgive him. However I will state this much: I am difficult to please when it comes to omniscient third because so few authors get it right. Lynch gets around this by having short sub-sections per chapter, so that he cycles through characters’ points of view as and when it’s necessary, but every once in a while the author-narrator intrudes.

I will add that Lynch is one of the few fantasy authors who, in my mind, can get away with writing the kind of shallow third verging on omniscient point of view that he does. He sometimes skates dangerously close to withholding key information, but the break-neck speed of his telling at key moments means that even when he does neglect to share what Locke or Jean knows, he usually shows the rest of his hand soon enough after. So I forgive him. However I will state this much: I am difficult to please when it comes to omniscient third because so few authors get it right. Lynch gets around this by having short sub-sections per chapter, so that he cycles through characters’ points of view as and when it’s necessary, but every once in a while the author-narrator intrudes.For fear of spoilers, I’m not going to go into a general overview of the novel, suffice to say that it starts out with Locke and Jean planning the heist to end all heists – a job that’s two years in the making as they execute their designs of the aptly named Sinspire gaming house.

The environment in which they find themselves is decadent to say the least, and I lapped up the descriptions of the people. Lynch’s world building is intricate and layered, and I’ll hazard to say that nearly every small detail is important – so take note. He does a lot of foreshadowing to get around the fact that he doesn’t immediately clue you in with the full details. You’ll know something is afoot, but not much more than that until he reveals.

Also, I went into this novel expecting one thing, and about halfway through Lynch pulled the rug from under my feet and the kind of story I thought I would be reading turned out to be something completely different. I won’t say what, but it was awesome, and fun, and he introduced me to some unforgettable characters.

Damn it, Lynch. There is The Thing that happens near the end. I won’t say what but I was gutted. Not quite to the degree that I am reading Robin Hobb, but pretty darned close. And that’s all I will say on the matter.

Getting into Red Seas Under Red Skies was not immediate, as it felt to me that there was quite a bit of setting up that happened before the story really got underway. Lynch’s style isn’t for everyone, nor is the subject matter – focus is very much on action rather than emotional layering, which he keeps close to his chest. But once I got going, I was invested, and that’s what counts. I really do love the dynamics between Locke and Jean, even if the novel tends to stagger around unexpectedly. The worst part is that I finished reading the novel while on holiday in an area where I had to walk 1km to just get cellphone signal, so at the time I couldn’t go google to see whether there’s another novel to follow up this one… Yeah, it was that sort of book. (And there are more in the series… so I’m happy)

Published on December 29, 2017 12:07

December 14, 2017

What About Meera by ZP Dala

What About Meera by ZP Dala is one of those books I chose to read because I knew it would take me way out of my comfort zone, and not only that, but show me a slice of life I'm not privy to. Also, please just take a moment to appreciate the beauty of the cover. Just a little bit. It's even prettier when admiring the book in real life.

The blurb on the back goes on about the book being "full of black humour" and goes on about a "woman's attempts to shape her own destiny" but that makes it sound somewhat uplifting. This is, as the title, a story about Meera, an Indian South African woman who grew up on a sugar cane farm in Tongaat, but if I had to think of a subheading for the book, it would be more along the lines of "awful people being awful". And there are many awful people in this book who cross paths with Meera.

The blurb on the back goes on about the book being "full of black humour" and goes on about a "woman's attempts to shape her own destiny" but that makes it sound somewhat uplifting. This is, as the title, a story about Meera, an Indian South African woman who grew up on a sugar cane farm in Tongaat, but if I had to think of a subheading for the book, it would be more along the lines of "awful people being awful". And there are many awful people in this book who cross paths with Meera.

Dala digs deep beneath the skin of the South African Indian culture, examining the relationships between parents and children, wives and husbands, and the power structures that exist in communities. This is not an easy read, and truth be told, I found nothing at all humorous. Not even darkly humorous. Just crushingly dark and unrelenting – the way I like my books.

ZP's storytelling flows between past and present, sometimes digressing to show us more about the people in Meera's life and giving you an idea of what motivates them to be ... well ... the awful people doing the awful things.

I'll also have you know that I find this kind of digging under the skin absolutely lush, and some of the imagery is just perfect (like the wedding where the marigolds and human ordure accidentally met) so don't for one moment think I don't like it – I do. Even if the story is heartrending, even if you find yourself shaking your fists impotently at the situations Meera finds herself in.

At first she is passive, accepting an arranged marriage, accepting others' decisions for her, but there comes a time when the cumulative cruelty others mete out becomes too much, and Meera cracks. At first she runs back to her parents, but here she is a woman who doesn't know her place. "Go back to your husband," they keep telling her, but instead she flees to Dublin, of all places, in a desperate attempt to find something for herself.

And for a while it seems that she's doing all right, that is until she has a passionate affair with an Irishman ... which drives her to The Awful Thing. And it is awful. Truly godawful. And I find it difficult to forgive her. But I do have empathy for her. Meera is broken. Her responses are as a result of the brokenness of her upbringing and her desperate attempts to gain direction in her life (and her eventual failure to do just that).

ZP doesn't flinch from ugliness. In fact, she purposefully holds up that cracked, dirty mirror so that we may examine ourselves and how we relate to others. This is not an easy book to read, but I savoured every chapter and the fluidity of the telling that went at exactly the pace it needed to go, even when it digressed to nearly surreal moments that, I feel, did well to express Meera's desperate situation.

If you're looking for hope, for some sort of reassurance of something better, this is not your book. What About Meera is an evocative, dark existentialist fugue that revels in the brittle, broken parts of human nature; it's about the realisation that we are all, in a sense, victims of circumstances and there is no escape. It's about not getting the words to the song right, and being okay with that. And then revelling in the absurdity of life, in its short, nasty and brutish nature.

The blurb on the back goes on about the book being "full of black humour" and goes on about a "woman's attempts to shape her own destiny" but that makes it sound somewhat uplifting. This is, as the title, a story about Meera, an Indian South African woman who grew up on a sugar cane farm in Tongaat, but if I had to think of a subheading for the book, it would be more along the lines of "awful people being awful". And there are many awful people in this book who cross paths with Meera.

The blurb on the back goes on about the book being "full of black humour" and goes on about a "woman's attempts to shape her own destiny" but that makes it sound somewhat uplifting. This is, as the title, a story about Meera, an Indian South African woman who grew up on a sugar cane farm in Tongaat, but if I had to think of a subheading for the book, it would be more along the lines of "awful people being awful". And there are many awful people in this book who cross paths with Meera.Dala digs deep beneath the skin of the South African Indian culture, examining the relationships between parents and children, wives and husbands, and the power structures that exist in communities. This is not an easy read, and truth be told, I found nothing at all humorous. Not even darkly humorous. Just crushingly dark and unrelenting – the way I like my books.

ZP's storytelling flows between past and present, sometimes digressing to show us more about the people in Meera's life and giving you an idea of what motivates them to be ... well ... the awful people doing the awful things.

I'll also have you know that I find this kind of digging under the skin absolutely lush, and some of the imagery is just perfect (like the wedding where the marigolds and human ordure accidentally met) so don't for one moment think I don't like it – I do. Even if the story is heartrending, even if you find yourself shaking your fists impotently at the situations Meera finds herself in.

At first she is passive, accepting an arranged marriage, accepting others' decisions for her, but there comes a time when the cumulative cruelty others mete out becomes too much, and Meera cracks. At first she runs back to her parents, but here she is a woman who doesn't know her place. "Go back to your husband," they keep telling her, but instead she flees to Dublin, of all places, in a desperate attempt to find something for herself.

And for a while it seems that she's doing all right, that is until she has a passionate affair with an Irishman ... which drives her to The Awful Thing. And it is awful. Truly godawful. And I find it difficult to forgive her. But I do have empathy for her. Meera is broken. Her responses are as a result of the brokenness of her upbringing and her desperate attempts to gain direction in her life (and her eventual failure to do just that).

ZP doesn't flinch from ugliness. In fact, she purposefully holds up that cracked, dirty mirror so that we may examine ourselves and how we relate to others. This is not an easy book to read, but I savoured every chapter and the fluidity of the telling that went at exactly the pace it needed to go, even when it digressed to nearly surreal moments that, I feel, did well to express Meera's desperate situation.

If you're looking for hope, for some sort of reassurance of something better, this is not your book. What About Meera is an evocative, dark existentialist fugue that revels in the brittle, broken parts of human nature; it's about the realisation that we are all, in a sense, victims of circumstances and there is no escape. It's about not getting the words to the song right, and being okay with that. And then revelling in the absurdity of life, in its short, nasty and brutish nature.

Published on December 14, 2017 10:13

November 18, 2017

Kingdom of Daylight: Memories of a Birdwatcher by Peter Steyn

A little back story here: When I was in primary school, Standard 4, or thereabouts, I won a book prize for my academic activities and my class teacher gave me the Robert's Bird Guide for the southern African region. Little did that teacher know that they would be sparking a life-long interest in our avian friends (not that I needed much nudging, since I had grown up on a steady diet of nature documentaries and was still hell bent on going into nature conservation*).

So, imagine my frabjous joy when Peter Steyn's Kingdom of Daylight: Memories of a Birdwatcher landed on my desk. [Serious bird geek here, all right?]

So, imagine my frabjous joy when Peter Steyn's Kingdom of Daylight: Memories of a Birdwatcher landed on my desk. [Serious bird geek here, all right?]

Anyhow, here's the low-down for those who don't know about Steyn. Though he started out as a teacher, his all-consuming passion for the study and photography of birds led him to eventually go full time with his interest, and this man has written piles of books. Piles. And his photos are just bloody marvellous. His patience for sitting in a hide to snap that one perfect shot makes me realise exactly how much work goes into those wonderful bird books I took for granted when I was younger (yes, I own a hardcover, first edition of The Complete Book of South African Birds that my parents couldn't really afford to buy for me at the time but did anyway.)

Kingdom of Daylight is, in a nutshell, Steyn's summary of his adventures throughout his life, from his boyhood in Cape Town, to the years he spent in Zimbabwe before moving back to Cape Town. Each chapter deals with a location or a specific trip, and discusses not only the many birds he saw there, but also offers glimpses into the lives of the people who're movers and shakers in ornithological circles, as well as some background in his experiences while travelling. And this man has travelled...

There are times when I wish there'd been more space for more photos, because really, the many smaller images in the side panels are a little on the tiny side, so the layout really doesn't do them justice – even though they do give a better idea of the overall scope of Steyn's experiences. At times I did feel that the writing was a wee smidge on the dry side, but overall I realise that he has so much information that he needs to impart in only so much space.

There are times when I wish there'd been more space for more photos, because really, the many smaller images in the side panels are a little on the tiny side, so the layout really doesn't do them justice – even though they do give a better idea of the overall scope of Steyn's experiences. At times I did feel that the writing was a wee smidge on the dry side, but overall I realise that he has so much information that he needs to impart in only so much space.

Also, I'm really inspired now myself to sort out my stuff so that I can travel to some of the destinations Steyn has – especially locations like Madagascar and other parts of the African continent. He most certainly has lived a remarkable life. If anything, Steyn reminds me to slow down and really appreciate my own environment because it's not just those exotic birds on any birdwatcher's life list, but most certainly also in the joy of observing the birds I see in my garden every day. Five bats out of Auntie's hat for Peter Steyn.

* Fortunately I did something sensible, and studied graphic design, because in hindsight, as much as I love nature, I don't fancy being chased by elephants or acting as a glorified nanny for foreign tourists at some larny private game reserve.

So, imagine my frabjous joy when Peter Steyn's Kingdom of Daylight: Memories of a Birdwatcher landed on my desk. [Serious bird geek here, all right?]

So, imagine my frabjous joy when Peter Steyn's Kingdom of Daylight: Memories of a Birdwatcher landed on my desk. [Serious bird geek here, all right?]Anyhow, here's the low-down for those who don't know about Steyn. Though he started out as a teacher, his all-consuming passion for the study and photography of birds led him to eventually go full time with his interest, and this man has written piles of books. Piles. And his photos are just bloody marvellous. His patience for sitting in a hide to snap that one perfect shot makes me realise exactly how much work goes into those wonderful bird books I took for granted when I was younger (yes, I own a hardcover, first edition of The Complete Book of South African Birds that my parents couldn't really afford to buy for me at the time but did anyway.)

Kingdom of Daylight is, in a nutshell, Steyn's summary of his adventures throughout his life, from his boyhood in Cape Town, to the years he spent in Zimbabwe before moving back to Cape Town. Each chapter deals with a location or a specific trip, and discusses not only the many birds he saw there, but also offers glimpses into the lives of the people who're movers and shakers in ornithological circles, as well as some background in his experiences while travelling. And this man has travelled...

There are times when I wish there'd been more space for more photos, because really, the many smaller images in the side panels are a little on the tiny side, so the layout really doesn't do them justice – even though they do give a better idea of the overall scope of Steyn's experiences. At times I did feel that the writing was a wee smidge on the dry side, but overall I realise that he has so much information that he needs to impart in only so much space.

There are times when I wish there'd been more space for more photos, because really, the many smaller images in the side panels are a little on the tiny side, so the layout really doesn't do them justice – even though they do give a better idea of the overall scope of Steyn's experiences. At times I did feel that the writing was a wee smidge on the dry side, but overall I realise that he has so much information that he needs to impart in only so much space.Also, I'm really inspired now myself to sort out my stuff so that I can travel to some of the destinations Steyn has – especially locations like Madagascar and other parts of the African continent. He most certainly has lived a remarkable life. If anything, Steyn reminds me to slow down and really appreciate my own environment because it's not just those exotic birds on any birdwatcher's life list, but most certainly also in the joy of observing the birds I see in my garden every day. Five bats out of Auntie's hat for Peter Steyn.

* Fortunately I did something sensible, and studied graphic design, because in hindsight, as much as I love nature, I don't fancy being chased by elephants or acting as a glorified nanny for foreign tourists at some larny private game reserve.

Published on November 18, 2017 10:45

November 17, 2017

The Thousand Steps (Elevation #1) by Helen Brain

First off, I must add, that Helen Brain's The Thousand Steps (the first of her Elevation trilogy) has scored what I think is quite possibly the best-looking cover for South African youth literature that I've seen in a long, long time. Wow. It's the kind of book that just begs to be picked up and admired.

The story itself stood out for me because while it plays on the usual "chosen one" riff that is so common in SFF, it does so with originality and nuance that I find is so often lacking in the genre. There's a lot going on under the skin.

Ebba den Eeden, our protagonist, starts out life in an underground bunker, where she and two thousand other young people are set to work shifts producing food for their community. Or so they think. She's led to believe that the world outside their bunker has been destroyed during a great cataclysm. That is, until she is miraculously "Elevated" at the eleventh hour before her execution, that is. (A rescue in the nick of time that seems awfully convenient, if you ask me.)

Ebba's Cape Peninsula is vastly different to the one we know today, and I loved seeing an environment I know defamiliarised. The higher sea level means that the mountain chain of the region has become a string of islands, and the communities living there have a hard life: food is scarce and the disparity between the haves and the have-nots is tremendous.

Coping with this sudden turnaround in her world, from being but a lowly drudge to one of the elite, is not easy, and while on one hand I felt that Ebba herself lacked agency in book one, this was, I believe, in keeping with her character development – she is way out of her depth and struggling to know her place and understand the power that she can wield.

Yet her intentions are good, even if her naïveté is painful, and though I cringed often as I saw her trying to navigate this society in which she found herself, her words and deeds come from a good place. It cannot be easy for a girl who's followed orders her entire life to kick against an authoritarian regime has infiltrated nearly every facet of the people's lives. Ebba is very much in a gawky phase in this story, where she hasn't fully grasped her power – so expect her to make mistakes and flounder a bit, and for others to take the initiative.

There are some lovely secondary characters, like Isi the dog and, of course, Aunty Figgy, whose special brand of magic happens in the kitchen. The world Helen conjures up feels tactile, as if it could possibly just exist in a slightly left-of-parallel universe. Yes, yes, in case you're asking, there is a kinda love triangle. Well not quite. But you'll have to see. I did feel as if the love interest was a bit quick on the draw, but then again there's a lot happening, and we get to the end of book one at a rapid rate.

I must add that much of book one does come across like an extended introduction to the setting, giving us all the main players and an indication of conflict – so don't expect any closure. There are loads of threads left hanging, and I'm looking forward to seeing how Helen will weave them together.

Where Helen shines is that she has a keen eye for understanding how people interact, especially in the subtexts of non-verbal communication, and indirect characterisation, which she brings across often so poignantly. There's a part of me that wishes the story could have been expanded, so that we could've dug deeper. (Though this may also be due to the fact that I'm used to reading doorstoppers, so don't mind me too much.) My biggest criticism was that the action sequences felt a bit rushed, glossed over and cause-and-effect not quite established, but the the sheer depth and breadth of her well thought-out world building, and an entire mythology to unpick, more than makes up for this.

Where Helen shines is that she has a keen eye for understanding how people interact, especially in the subtexts of non-verbal communication, and indirect characterisation, which she brings across often so poignantly. There's a part of me that wishes the story could have been expanded, so that we could've dug deeper. (Though this may also be due to the fact that I'm used to reading doorstoppers, so don't mind me too much.) My biggest criticism was that the action sequences felt a bit rushed, glossed over and cause-and-effect not quite established, but the the sheer depth and breadth of her well thought-out world building, and an entire mythology to unpick, more than makes up for this.

My verdict: This is a super awesome story. It reads quickly, and there's much to unpack, and I'm looking forward to seeing where Helen takes this. Five bats squeaking out of auntie Nerine's hat for The Thousand Steps.

The story itself stood out for me because while it plays on the usual "chosen one" riff that is so common in SFF, it does so with originality and nuance that I find is so often lacking in the genre. There's a lot going on under the skin.

Ebba den Eeden, our protagonist, starts out life in an underground bunker, where she and two thousand other young people are set to work shifts producing food for their community. Or so they think. She's led to believe that the world outside their bunker has been destroyed during a great cataclysm. That is, until she is miraculously "Elevated" at the eleventh hour before her execution, that is. (A rescue in the nick of time that seems awfully convenient, if you ask me.)

Ebba's Cape Peninsula is vastly different to the one we know today, and I loved seeing an environment I know defamiliarised. The higher sea level means that the mountain chain of the region has become a string of islands, and the communities living there have a hard life: food is scarce and the disparity between the haves and the have-nots is tremendous.

Coping with this sudden turnaround in her world, from being but a lowly drudge to one of the elite, is not easy, and while on one hand I felt that Ebba herself lacked agency in book one, this was, I believe, in keeping with her character development – she is way out of her depth and struggling to know her place and understand the power that she can wield.

Yet her intentions are good, even if her naïveté is painful, and though I cringed often as I saw her trying to navigate this society in which she found herself, her words and deeds come from a good place. It cannot be easy for a girl who's followed orders her entire life to kick against an authoritarian regime has infiltrated nearly every facet of the people's lives. Ebba is very much in a gawky phase in this story, where she hasn't fully grasped her power – so expect her to make mistakes and flounder a bit, and for others to take the initiative.

There are some lovely secondary characters, like Isi the dog and, of course, Aunty Figgy, whose special brand of magic happens in the kitchen. The world Helen conjures up feels tactile, as if it could possibly just exist in a slightly left-of-parallel universe. Yes, yes, in case you're asking, there is a kinda love triangle. Well not quite. But you'll have to see. I did feel as if the love interest was a bit quick on the draw, but then again there's a lot happening, and we get to the end of book one at a rapid rate.

I must add that much of book one does come across like an extended introduction to the setting, giving us all the main players and an indication of conflict – so don't expect any closure. There are loads of threads left hanging, and I'm looking forward to seeing how Helen will weave them together.

Where Helen shines is that she has a keen eye for understanding how people interact, especially in the subtexts of non-verbal communication, and indirect characterisation, which she brings across often so poignantly. There's a part of me that wishes the story could have been expanded, so that we could've dug deeper. (Though this may also be due to the fact that I'm used to reading doorstoppers, so don't mind me too much.) My biggest criticism was that the action sequences felt a bit rushed, glossed over and cause-and-effect not quite established, but the the sheer depth and breadth of her well thought-out world building, and an entire mythology to unpick, more than makes up for this.

Where Helen shines is that she has a keen eye for understanding how people interact, especially in the subtexts of non-verbal communication, and indirect characterisation, which she brings across often so poignantly. There's a part of me that wishes the story could have been expanded, so that we could've dug deeper. (Though this may also be due to the fact that I'm used to reading doorstoppers, so don't mind me too much.) My biggest criticism was that the action sequences felt a bit rushed, glossed over and cause-and-effect not quite established, but the the sheer depth and breadth of her well thought-out world building, and an entire mythology to unpick, more than makes up for this.My verdict: This is a super awesome story. It reads quickly, and there's much to unpack, and I'm looking forward to seeing where Helen takes this. Five bats squeaking out of auntie Nerine's hat for The Thousand Steps.

Published on November 17, 2017 11:13

October 23, 2017

City of Masks by Ashley Capes

City of Masks (Bone Mask Trilogy #1) by Ashley Capes is one of those review books that has been languishing in my Kindle app for far too long, so I pressed on and finished it. I have mixed feelings about this book. On one hand I really, really wanted to like it because the world that Capes introduces us to is rich in lore. We have Anaskar, a port city, that is guided by those who wear the Greatmasks – objects of power that imbue the wearer with certain powers. We have the Mascare – an elite secret police, masked of course, who police the city. The society itself is almost Venetian in its Machiavellian power struggles as people attempt to work their way to literally living in the top tier of the city.

Characters are certainly diverse as they are fascinating – we meet Sofia, who's caught in the middle of an awful betrayal. We have Notch, an erstwhile city guard now reduced to Mercenary. We have the mysterious innkeeper Seto, who is most certainly more than he appears to be. Flir is an exceptionally strong woman. As in supernaturally strong. I won't spoil where she gets her powers. Throw all these misfits together, and you've certainly got an interesting dynamic going. Add in a few mysterious dangerous beasties too, as well as a pair of tribesmen on a holy mission ... and things become downright chaotic.

Characters are certainly diverse as they are fascinating – we meet Sofia, who's caught in the middle of an awful betrayal. We have Notch, an erstwhile city guard now reduced to Mercenary. We have the mysterious innkeeper Seto, who is most certainly more than he appears to be. Flir is an exceptionally strong woman. As in supernaturally strong. I won't spoil where she gets her powers. Throw all these misfits together, and you've certainly got an interesting dynamic going. Add in a few mysterious dangerous beasties too, as well as a pair of tribesmen on a holy mission ... and things become downright chaotic.

Look, the story was interesting. I never once wanted to throw the book across the room (besides breaking my iPad) but I felt that many of the important plot threads didn't *quite* hang together as nicely as they could have. I can see there were touches were a little foreshadowing happened, but this seemed slightly tacked on and by the by, and nearly coincidental. I wanted more. This book could have been about a third longer just so that the threads could have been a lot more strongly woven more thoroughly enhanced, deeper. Characters sometimes behave in ways that lack sufficient motivation as well. There are odd little bits thrown in that don't quite go anywhere. Or events that are not quite fully explained, though I hope they are developed in the books that follow.

Is this a worthy read? Yes. I'll add that some of the stuff that bothered me was the kind of stuff that I'd have caught while doing an assessment. I couldn't quite take off my editor hat while reading, which suggests that this novel could have been pushed a bit harder during editing. But it's not a deal breaker. I was still engaged. I still cared about the characters, and to be quite honest, this will most likely not even bother most readers.

There is a rich world here, full of interest, and City of Masks has moments where it shines, which makes it a solid read for those who love fantasy with a sense of immense lore and layers of mystery.

Characters are certainly diverse as they are fascinating – we meet Sofia, who's caught in the middle of an awful betrayal. We have Notch, an erstwhile city guard now reduced to Mercenary. We have the mysterious innkeeper Seto, who is most certainly more than he appears to be. Flir is an exceptionally strong woman. As in supernaturally strong. I won't spoil where she gets her powers. Throw all these misfits together, and you've certainly got an interesting dynamic going. Add in a few mysterious dangerous beasties too, as well as a pair of tribesmen on a holy mission ... and things become downright chaotic.

Characters are certainly diverse as they are fascinating – we meet Sofia, who's caught in the middle of an awful betrayal. We have Notch, an erstwhile city guard now reduced to Mercenary. We have the mysterious innkeeper Seto, who is most certainly more than he appears to be. Flir is an exceptionally strong woman. As in supernaturally strong. I won't spoil where she gets her powers. Throw all these misfits together, and you've certainly got an interesting dynamic going. Add in a few mysterious dangerous beasties too, as well as a pair of tribesmen on a holy mission ... and things become downright chaotic.Look, the story was interesting. I never once wanted to throw the book across the room (besides breaking my iPad) but I felt that many of the important plot threads didn't *quite* hang together as nicely as they could have. I can see there were touches were a little foreshadowing happened, but this seemed slightly tacked on and by the by, and nearly coincidental. I wanted more. This book could have been about a third longer just so that the threads could have been a lot more strongly woven more thoroughly enhanced, deeper. Characters sometimes behave in ways that lack sufficient motivation as well. There are odd little bits thrown in that don't quite go anywhere. Or events that are not quite fully explained, though I hope they are developed in the books that follow.

Is this a worthy read? Yes. I'll add that some of the stuff that bothered me was the kind of stuff that I'd have caught while doing an assessment. I couldn't quite take off my editor hat while reading, which suggests that this novel could have been pushed a bit harder during editing. But it's not a deal breaker. I was still engaged. I still cared about the characters, and to be quite honest, this will most likely not even bother most readers.

There is a rich world here, full of interest, and City of Masks has moments where it shines, which makes it a solid read for those who love fantasy with a sense of immense lore and layers of mystery.

Published on October 23, 2017 14:16

October 9, 2017

The Not-Quite September fanfiction round-up

This was totally meant to be the September fanfiction round-up but then I wanted to finish this massive AU Solavellan fic called

Schooling Pride

by AnaChromystic. I’ll give a big-ass disclaimer and say that I normally *don’t* do AUs, but this one tickled me. The writing’s not perfect. My inner editor wanted to slice and dice because the pacing is a bit uneven in places, but considering that I stuck it through to the end, the payoff was great. There’s no magic in this modern Thedas, and Solas is the adopted scion of a messy, horrible wealthy family. The story is all about how an initial hate-fuck with a rebellious Ellana Lavellan turns into something deeper, and how together they help him break away from his abusive family. The ending gives all the feels. I’d hazard to say that this deviates so far from lore nearly all the serial numbers have been filed off, but I still found something oddly compelling about this piece, and the writer gives a lot of emotional depth.

PridetotheFall is a writer I’ve been following for a while on AO3 and I was super happy when I saw that they’ve got a new piece up. Ashes and Embers is a one-chapter piece that takes us right to the beginning of the events transpiring in Inquisition. Major plot spoilers: If you’ve not finished Trespasser, then for the love of dog don’t read this story. It’s told from Solas’s point of view. Enough said. For those of us who’re madly and passionately still in Solavellan hell, this story is *just* right. Everything about this story is perfect. The nuances, the layering, the descriptions. Hell, this writer can (and probably should) think about writing original fiction and trying to put themselves out on the market. Enough gushing. Go read it if you think this will be your thing. It’s part of their Beautiful Chains series, which I’m now going to go finish.

It was Cullen Appreciation Week recently, so my friends Sulahn and withah collaborated on a piece called Strange Behaviour – which I then beta-read. I’m a huge Cullen fan (you wouldn’t think so, but jawellnofine, I won’t lie) and this piece nails our favourite Commander’s tone perfectly. It’s a sweet bit of LavellanXCullen warm fluff.

And of course I’m totally enjoying part two of withah’s Warded Heart series – especially wonderful for all the Cullenites out there. This story picks up with Cullen and the Hero’s happy-for-now as they navigate their new marriage and the little one on its way in the midst of the events that transpire during the battle with Corypheus. Not the best time to be raising littlies… But what I love about this story is the way the two characters are often at cross purposes because of their outlooks on the mage/templar conflict.

That’s it for now. If you have any pieces to suggest, mail me at nerinedorman@gmail.com

PridetotheFall is a writer I’ve been following for a while on AO3 and I was super happy when I saw that they’ve got a new piece up. Ashes and Embers is a one-chapter piece that takes us right to the beginning of the events transpiring in Inquisition. Major plot spoilers: If you’ve not finished Trespasser, then for the love of dog don’t read this story. It’s told from Solas’s point of view. Enough said. For those of us who’re madly and passionately still in Solavellan hell, this story is *just* right. Everything about this story is perfect. The nuances, the layering, the descriptions. Hell, this writer can (and probably should) think about writing original fiction and trying to put themselves out on the market. Enough gushing. Go read it if you think this will be your thing. It’s part of their Beautiful Chains series, which I’m now going to go finish.

It was Cullen Appreciation Week recently, so my friends Sulahn and withah collaborated on a piece called Strange Behaviour – which I then beta-read. I’m a huge Cullen fan (you wouldn’t think so, but jawellnofine, I won’t lie) and this piece nails our favourite Commander’s tone perfectly. It’s a sweet bit of LavellanXCullen warm fluff.

And of course I’m totally enjoying part two of withah’s Warded Heart series – especially wonderful for all the Cullenites out there. This story picks up with Cullen and the Hero’s happy-for-now as they navigate their new marriage and the little one on its way in the midst of the events that transpire during the battle with Corypheus. Not the best time to be raising littlies… But what I love about this story is the way the two characters are often at cross purposes because of their outlooks on the mage/templar conflict.

That’s it for now. If you have any pieces to suggest, mail me at nerinedorman@gmail.com

Published on October 09, 2017 11:31

September 25, 2017

The Gloaming

Published on September 25, 2017 02:49

September 21, 2017

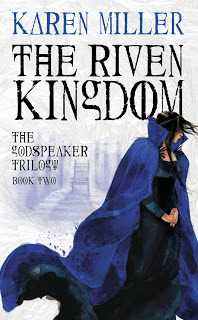

The Riven Kingdom (The Godspeaker Trilogy #2) by Karen Miller

The Riven Kingdom (The Godspeaker Trilogy #2) by Karen Miller is part of my catching up of all the fantasy novels I've been meaning to read over the years, and it's one of the titles so far that's led me to believe that Miller is possibly one of the most underrated voices in the genre I've encountered in a while. I tucked into book #1, Empress, a while back, and was a bit concerned that I'd lose the thread, but there was sufficient recap in book #2 that I wasn't at a complete loss; Miller touches on the pertinent bits without going overboard.

The Riven Kingdom introduces us to Princess Rhian, whose father the king is dying. During more enlightened times, she would have been heir to the throne, but unfortunately for her, the island kingdom of Ethrea still favours a male heir. With her two older brothers being deceased, her fate is to marry the man chosen for her to be her king, and to then produce future kings. So, basically, she's a prize brood mare and all the dukes and the church are gasping to place the future king of their choice on the throne. Absolutely lovely. You can well imagine that Rhian is less than pleased by this state of affairs.

The Riven Kingdom introduces us to Princess Rhian, whose father the king is dying. During more enlightened times, she would have been heir to the throne, but unfortunately for her, the island kingdom of Ethrea still favours a male heir. With her two older brothers being deceased, her fate is to marry the man chosen for her to be her king, and to then produce future kings. So, basically, she's a prize brood mare and all the dukes and the church are gasping to place the future king of their choice on the throne. Absolutely lovely. You can well imagine that Rhian is less than pleased by this state of affairs.

Indulged from a young age with an education and some instruction in less gentle pursuits, like fencing, Rhian is not your typical princess, and she's absolutely not going to allow a bunch of stodgy old men tell her who she's going to marry. Add a grasping, power-hungry religious leader to the mix, who seeks to control Rhian after her father's passing, and we're set up for the essential theme that runs through this book – the battle for the separation of church and state.

In fact, the theme of religion runs heavy throughout the trilogy, from the looks of things. In book #1, we meet Hekat, who justifies her grab for power through her faith in a hungry, violent god that demands bloodshed. She is ruthless in her actions, and though not a likeable character by any means, is fascinating to observe how she constantly does mental gymnastics to maintain her power and her stance.

Rhian also has to balance power and religion. She's from a deeply religious nation, and often her behaviour is very much that of an indulged, untried girl who's used to getting her own way. [I realise this might make people hate her as well.] Yet her intentions, compared to Hekat, are that of being a just, fair ruler. Much like Hekat, she has a great conviction that she is meant to rule, and will do what she must to attain her aims.

Not everyone in Ethrea is religious. We compare Marlan, the antagonist – the prolate who wishes to rule through a puppet monarch. He doesn't believe in a god but he will use religion as a way to control people. There is most certainly a strong nod towards the Catholic Church's machinations in this story. On the other hand, we have the formerly agnostic toymaker Dexterity, who gets dragged into the saga rather unwillingly – he has liminal experiences thrust upon him and he is granted god-given power to perform miracles. What he does with his powers is vastly different than what Marlan would.

The character I'm sure most loved to hate was Rhian's chaplain Helfred. At first he comes across as a thoroughly despicable, weak individual whose faith makes him annoying as all hell. Yet his redemption arc from a toadying sycophant to a man of true faith is perhaps the most satisfying.

The way characters deal with power – the gaining thereof and the loss, makes for a fascinating dynamic. We have former warlord Zandakar, reduced to a slave and rescued by Dexterity, whom I suspect will still play a pivotal role in book #3, and there is the way Rhian realises that she literally holds the power of life and death, and how she is then faced with the choice of what sort of ruler she will become.

I realise I've gone on a lot more with this review than I normally do, but that's because this is a book that made me think quite a bit. I will say this much: I didn't like any of the characters, except perhaps for Ursa the healer. Yet there is a lot going on here which makes it a worthy novel to read. There were moments when I felt there was literally a bit too much of a deus ex machina happening, yet I do have to admit that this very issue is central to the plot. Which makes me wonder about the rules applying to deities in this setting (which I'm sure Miller will go into eventually, or at least I hope so).

Miller doesn't shrink from graphic depictions of violence, and her characters (who occasionally verge on twee) are very much painted in shades of grey (which then redeems them), so I have to give her this much – she gives a few unexpected twists and turns but all in all delivers a solid and compelling read that has given me much to consider.

The Riven Kingdom introduces us to Princess Rhian, whose father the king is dying. During more enlightened times, she would have been heir to the throne, but unfortunately for her, the island kingdom of Ethrea still favours a male heir. With her two older brothers being deceased, her fate is to marry the man chosen for her to be her king, and to then produce future kings. So, basically, she's a prize brood mare and all the dukes and the church are gasping to place the future king of their choice on the throne. Absolutely lovely. You can well imagine that Rhian is less than pleased by this state of affairs.

The Riven Kingdom introduces us to Princess Rhian, whose father the king is dying. During more enlightened times, she would have been heir to the throne, but unfortunately for her, the island kingdom of Ethrea still favours a male heir. With her two older brothers being deceased, her fate is to marry the man chosen for her to be her king, and to then produce future kings. So, basically, she's a prize brood mare and all the dukes and the church are gasping to place the future king of their choice on the throne. Absolutely lovely. You can well imagine that Rhian is less than pleased by this state of affairs.Indulged from a young age with an education and some instruction in less gentle pursuits, like fencing, Rhian is not your typical princess, and she's absolutely not going to allow a bunch of stodgy old men tell her who she's going to marry. Add a grasping, power-hungry religious leader to the mix, who seeks to control Rhian after her father's passing, and we're set up for the essential theme that runs through this book – the battle for the separation of church and state.

In fact, the theme of religion runs heavy throughout the trilogy, from the looks of things. In book #1, we meet Hekat, who justifies her grab for power through her faith in a hungry, violent god that demands bloodshed. She is ruthless in her actions, and though not a likeable character by any means, is fascinating to observe how she constantly does mental gymnastics to maintain her power and her stance.

Rhian also has to balance power and religion. She's from a deeply religious nation, and often her behaviour is very much that of an indulged, untried girl who's used to getting her own way. [I realise this might make people hate her as well.] Yet her intentions, compared to Hekat, are that of being a just, fair ruler. Much like Hekat, she has a great conviction that she is meant to rule, and will do what she must to attain her aims.

Not everyone in Ethrea is religious. We compare Marlan, the antagonist – the prolate who wishes to rule through a puppet monarch. He doesn't believe in a god but he will use religion as a way to control people. There is most certainly a strong nod towards the Catholic Church's machinations in this story. On the other hand, we have the formerly agnostic toymaker Dexterity, who gets dragged into the saga rather unwillingly – he has liminal experiences thrust upon him and he is granted god-given power to perform miracles. What he does with his powers is vastly different than what Marlan would.

The character I'm sure most loved to hate was Rhian's chaplain Helfred. At first he comes across as a thoroughly despicable, weak individual whose faith makes him annoying as all hell. Yet his redemption arc from a toadying sycophant to a man of true faith is perhaps the most satisfying.

The way characters deal with power – the gaining thereof and the loss, makes for a fascinating dynamic. We have former warlord Zandakar, reduced to a slave and rescued by Dexterity, whom I suspect will still play a pivotal role in book #3, and there is the way Rhian realises that she literally holds the power of life and death, and how she is then faced with the choice of what sort of ruler she will become.

I realise I've gone on a lot more with this review than I normally do, but that's because this is a book that made me think quite a bit. I will say this much: I didn't like any of the characters, except perhaps for Ursa the healer. Yet there is a lot going on here which makes it a worthy novel to read. There were moments when I felt there was literally a bit too much of a deus ex machina happening, yet I do have to admit that this very issue is central to the plot. Which makes me wonder about the rules applying to deities in this setting (which I'm sure Miller will go into eventually, or at least I hope so).

Miller doesn't shrink from graphic depictions of violence, and her characters (who occasionally verge on twee) are very much painted in shades of grey (which then redeems them), so I have to give her this much – she gives a few unexpected twists and turns but all in all delivers a solid and compelling read that has given me much to consider.

Published on September 21, 2017 04:53

September 20, 2017

Why the reader isn't always right

The other day, someone threw back at me the idea that a reader can use whatever criteria they like when evaluating a work of fiction. They're right, of course, but I'm also going to call bollocks on this statement.

I can take any written work, be it the Bible or Fifty Shades of Grey, and I can read the book any way I want to. I can choose to see either of those titles as the product of a raving lunatic or an expression of pure genius. I might be wrong. I might be right. It all depends on who I am and what my values are.

I can take any written work, be it the Bible or Fifty Shades of Grey, and I can read the book any way I want to. I can choose to see either of those titles as the product of a raving lunatic or an expression of pure genius. I might be wrong. I might be right. It all depends on who I am and what my values are.

The Dark Tower movie might fail the Bechdel Test miserably, in my opinion, but I can't use that as the sole criteria to evaluate whether I think it's a good film (or not). (Or even whether it's a half-decent adaption of a Stephen King novel.)

But you see what the problem is here. We're not coming to any objective conclusion as to whether a work has any literary merit whatsoever. How are we evaluating a work?

Welcome to cultural relativism, where everyone's opinion is equally valid and we are incapable of gauging whether a cultural object is ... well ... good.

Before we go haring off into the hinterlands, let's just look at communication. Books are communication. You've got the author, the cultural environment in which the book happens to be published, and you've got the reader.

We'll never know what's really going on in an author's head when they write their masterpiece, but sometimes they'll be interviewed or we'll have access to their journal, or there will be some indication as to what the author's intention was when they were creating a particular work. So, I guess what I'm saying, is keep it in mind that the author may have had particular intentions when they wrote their story, be it to purely entertain or perhaps function as a way to convey opinions. A romance author might intend her story to evoke the feelings of falling in love while a literary author might wish to challenge her readers' opinions about something or the other.

Now a book doesn't just float around in a vacuum. It often relates to other media, is perhaps created in response to or borrows from other texts. (This is called intertextuality, a kind of interplay and understanding of the relationships that happen between works.) Look at Neil Gaiman's The Sandman comics – they discuss and comment upon the huge body of works in comic book culture and, by default, human culture at large. [You can read The Sandman without knowing much about comics, but the experience is going to be so much richer if you do have that background.] So you'd also look at when a book was published, and who published it. You will look at its content in context with other examples of media. You will try to understand a work's relation to all these. So, in essence, you'll look at the bigger picture to give you an idea of where the work fits.

Ask yourself this: Would a novel like Lolita by Viktor Nabokov be published today? Why not?

Now, let's get to the reader. That's you. You don't know what the hell the author was thinking when he wrote the bloody book. Your cultural milieu might be vastly different from that of old Mr Nabokov. Or you might simply never have read enough in a particular genre to gain an understanding of its intertextuality. And now you're reviewing a book. Let's make it a romance novel. A nice, bodice-ripping, breeches-busting rompetty-pompetty. You've never read this sort of novel before. You've only ever read literary novels that are completely embedded with nuance and metaphor, where there're rich, profound cultural references and ideas that make you gaze off into the middle distance pondering the nature of reality.

What's your first reaction?

To be honest, I wouldn't blame you if you tossed that high-octane romance novel across the room so fast it broke the sound barrier. Here's the deal, and it's going to save you a lot of heartache in the future. Evaluate a novel without putting yourself into it, without using your likes/dislikes as the sole barometer as to whether a work is good.

In literary criticism terms, this is when you judge a book based on your own emotions (they call it the affective fallacy and that's all fancy-like). So, you think a character is junk and therefore because you don't like the character, the entire novel is now rubbish. You don't like talking rabbits? Well, that's not the only reason why Watership Down sucks*, is it? What if the author had never intended for a character to be likeable in the first place? Can you see what I'm getting at here? You didn't like the book because there was just sex in it? In fact, more sex than plot? And we all know that only stupid people read sex books, amiright? [That was sarcasm, BTW] Well, how does it compare to other erotica out there? Is it a pulpy small press novel meant to be devoured in one sitting by readers who want to get their panties all squishy and stuck up their butt cracks? You cannot compare this novel to Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace. For the love of fuck, please don't. They're not even remotely the same beasts. You do yourself a disservice if you do.

So, what can you, as a reader do?

Firstly, read widely and read outside of your chosen genres. Read novels that are considered classics. Maybe take time to read according to theme – like 19th-century Irish authors or the beat poets. Find out what makes the cut-up technique rock. [Fuck it, go read William Burroughs.] Then go read a proper Gothic novel, like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Try to paint a broader picture of literature. How does JRR Tolkien compare to Michael Moorcock? Don't just stay in your comfort zone because you're scared of big words. Hell, peaches, there's an entire interwebz out there. Improve your Google-fu if there're ideas or terminology that challenge you. Also, go read reviews for some of these novels. Ask yourself why you agree or disagree with what some of the reviewers say. Try to figure out why someone would come to a particular conclusion.

That's not to say you shouldn't read the books you love. Hell, I always have at least one epic fantasy novel's spine cracked at any given moment. But I do try to read stuff I wouldn't ordinarily dip into, like children's novels, dubcon erotica, military SF, classics, Afrikaans literature, historical...

Understand, mostly, that you have personal likes/dislikes that mean you'll never like a particular type of book. Hell, I'm not advocating that you suddenly develop a passion for political thrillers, but at least understand why a particular political thriller works as a piece of literature (good pacing, strong characterisation) as opposed to another book within the same genre that is poorly written and filled with cliché-ridden characters. Understand why a romance novel may be excellent within its genre even though you're not going to hold it up next to an intense literary masterwork.

I may loathe JM Coetzee's Disgrace with the fury of a thousand rabid camels, but I cannot deny that it's an excellent work of literature, for various reasons that I'm not going to go into now because they'll probably bore us both to tears. I'd sooner get my jollies reading the next Mark Lawrence, in any case. (However I have an idea what books Mr Lawrence has been reading, based on educated guesses related to intertextuality, which makes me quietly smile as I turn those pages.)

So, get to know all sorts of genres. Gain an understanding of what the objective values are that make good literature and how that varies between genres. When you evaluate, keep that bigger picture in mind. Look at the technical and aesthetic reasons why a particular work may be successful (or not), and go from there.

A book isn't just rubbish or a paragon of literary greatness. There are reasons why, and they're often way beyond your own personal likes and dislikes. Granted, you can use your own criteria as a guide, but try to dig a little deeper than, "I think Mr Joe is a horrible person and this book is sucks great big hairy bollocks."

In fact, what you hate about a novel often says a lot more about you than it does about the stupid sod who wrote the blighted thing. Just keep that at the back of mind when you start putting on the hate.

* Okay, I don't think Watership Down sucks, but some people might. In fact, I've cried every time I watched the fucking movie, okay? I just have to hear the song "Bright Eyes" and the waterworks begins.

I can take any written work, be it the Bible or Fifty Shades of Grey, and I can read the book any way I want to. I can choose to see either of those titles as the product of a raving lunatic or an expression of pure genius. I might be wrong. I might be right. It all depends on who I am and what my values are.

I can take any written work, be it the Bible or Fifty Shades of Grey, and I can read the book any way I want to. I can choose to see either of those titles as the product of a raving lunatic or an expression of pure genius. I might be wrong. I might be right. It all depends on who I am and what my values are.The Dark Tower movie might fail the Bechdel Test miserably, in my opinion, but I can't use that as the sole criteria to evaluate whether I think it's a good film (or not). (Or even whether it's a half-decent adaption of a Stephen King novel.)

But you see what the problem is here. We're not coming to any objective conclusion as to whether a work has any literary merit whatsoever. How are we evaluating a work?

Welcome to cultural relativism, where everyone's opinion is equally valid and we are incapable of gauging whether a cultural object is ... well ... good.

Before we go haring off into the hinterlands, let's just look at communication. Books are communication. You've got the author, the cultural environment in which the book happens to be published, and you've got the reader.

We'll never know what's really going on in an author's head when they write their masterpiece, but sometimes they'll be interviewed or we'll have access to their journal, or there will be some indication as to what the author's intention was when they were creating a particular work. So, I guess what I'm saying, is keep it in mind that the author may have had particular intentions when they wrote their story, be it to purely entertain or perhaps function as a way to convey opinions. A romance author might intend her story to evoke the feelings of falling in love while a literary author might wish to challenge her readers' opinions about something or the other.

Now a book doesn't just float around in a vacuum. It often relates to other media, is perhaps created in response to or borrows from other texts. (This is called intertextuality, a kind of interplay and understanding of the relationships that happen between works.) Look at Neil Gaiman's The Sandman comics – they discuss and comment upon the huge body of works in comic book culture and, by default, human culture at large. [You can read The Sandman without knowing much about comics, but the experience is going to be so much richer if you do have that background.] So you'd also look at when a book was published, and who published it. You will look at its content in context with other examples of media. You will try to understand a work's relation to all these. So, in essence, you'll look at the bigger picture to give you an idea of where the work fits.

Ask yourself this: Would a novel like Lolita by Viktor Nabokov be published today? Why not?

Now, let's get to the reader. That's you. You don't know what the hell the author was thinking when he wrote the bloody book. Your cultural milieu might be vastly different from that of old Mr Nabokov. Or you might simply never have read enough in a particular genre to gain an understanding of its intertextuality. And now you're reviewing a book. Let's make it a romance novel. A nice, bodice-ripping, breeches-busting rompetty-pompetty. You've never read this sort of novel before. You've only ever read literary novels that are completely embedded with nuance and metaphor, where there're rich, profound cultural references and ideas that make you gaze off into the middle distance pondering the nature of reality.

What's your first reaction?

To be honest, I wouldn't blame you if you tossed that high-octane romance novel across the room so fast it broke the sound barrier. Here's the deal, and it's going to save you a lot of heartache in the future. Evaluate a novel without putting yourself into it, without using your likes/dislikes as the sole barometer as to whether a work is good.

In literary criticism terms, this is when you judge a book based on your own emotions (they call it the affective fallacy and that's all fancy-like). So, you think a character is junk and therefore because you don't like the character, the entire novel is now rubbish. You don't like talking rabbits? Well, that's not the only reason why Watership Down sucks*, is it? What if the author had never intended for a character to be likeable in the first place? Can you see what I'm getting at here? You didn't like the book because there was just sex in it? In fact, more sex than plot? And we all know that only stupid people read sex books, amiright? [That was sarcasm, BTW] Well, how does it compare to other erotica out there? Is it a pulpy small press novel meant to be devoured in one sitting by readers who want to get their panties all squishy and stuck up their butt cracks? You cannot compare this novel to Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace. For the love of fuck, please don't. They're not even remotely the same beasts. You do yourself a disservice if you do.

So, what can you, as a reader do?

Firstly, read widely and read outside of your chosen genres. Read novels that are considered classics. Maybe take time to read according to theme – like 19th-century Irish authors or the beat poets. Find out what makes the cut-up technique rock. [Fuck it, go read William Burroughs.] Then go read a proper Gothic novel, like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Try to paint a broader picture of literature. How does JRR Tolkien compare to Michael Moorcock? Don't just stay in your comfort zone because you're scared of big words. Hell, peaches, there's an entire interwebz out there. Improve your Google-fu if there're ideas or terminology that challenge you. Also, go read reviews for some of these novels. Ask yourself why you agree or disagree with what some of the reviewers say. Try to figure out why someone would come to a particular conclusion.

That's not to say you shouldn't read the books you love. Hell, I always have at least one epic fantasy novel's spine cracked at any given moment. But I do try to read stuff I wouldn't ordinarily dip into, like children's novels, dubcon erotica, military SF, classics, Afrikaans literature, historical...

Understand, mostly, that you have personal likes/dislikes that mean you'll never like a particular type of book. Hell, I'm not advocating that you suddenly develop a passion for political thrillers, but at least understand why a particular political thriller works as a piece of literature (good pacing, strong characterisation) as opposed to another book within the same genre that is poorly written and filled with cliché-ridden characters. Understand why a romance novel may be excellent within its genre even though you're not going to hold it up next to an intense literary masterwork.

I may loathe JM Coetzee's Disgrace with the fury of a thousand rabid camels, but I cannot deny that it's an excellent work of literature, for various reasons that I'm not going to go into now because they'll probably bore us both to tears. I'd sooner get my jollies reading the next Mark Lawrence, in any case. (However I have an idea what books Mr Lawrence has been reading, based on educated guesses related to intertextuality, which makes me quietly smile as I turn those pages.)

So, get to know all sorts of genres. Gain an understanding of what the objective values are that make good literature and how that varies between genres. When you evaluate, keep that bigger picture in mind. Look at the technical and aesthetic reasons why a particular work may be successful (or not), and go from there.

A book isn't just rubbish or a paragon of literary greatness. There are reasons why, and they're often way beyond your own personal likes and dislikes. Granted, you can use your own criteria as a guide, but try to dig a little deeper than, "I think Mr Joe is a horrible person and this book is sucks great big hairy bollocks."

In fact, what you hate about a novel often says a lot more about you than it does about the stupid sod who wrote the blighted thing. Just keep that at the back of mind when you start putting on the hate.

* Okay, I don't think Watership Down sucks, but some people might. In fact, I've cried every time I watched the fucking movie, okay? I just have to hear the song "Bright Eyes" and the waterworks begins.

Published on September 20, 2017 10:17