Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 45

April 2, 2017

Never Too Grown Up for Picture Books

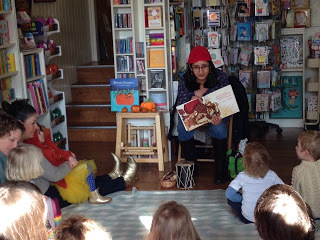

I love picture books – to read on my own, to read aloud to my nephews and to write. But the side-effect of writing picture books is that I also have to perform the book – or as I call it – Sing for my Supper. I usually sing a modified version of Old MacDonald Had a Farm – all it requires is enthusiasm.

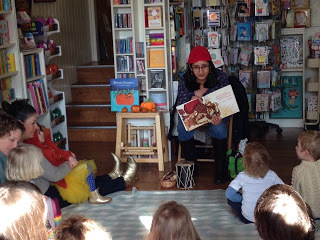

Notice the cap and the drums...When I get invited into schools, I usually have to do sessions with children from Reception to Year 6. Reception, Year 1 and Year 2 are perfect for the picture books. I tell stories, we make up stories together and they love reading from the picture books.Then for Year 3 and Year 4 – I read from my chapter books and discuss the stories for their inner meaning of justice and fairness. That’s all good.

Notice the cap and the drums...When I get invited into schools, I usually have to do sessions with children from Reception to Year 6. Reception, Year 1 and Year 2 are perfect for the picture books. I tell stories, we make up stories together and they love reading from the picture books.Then for Year 3 and Year 4 – I read from my chapter books and discuss the stories for their inner meaning of justice and fairness. That’s all good.

But what happens when I go into Year 5 and 6 classes? They are too old for my picture books and definitely not interested in my younger chapter books. At first I used to show my books for 30 seconds and then say, “I write for younger kids, let’s do some writing ourselves.” I would never bring out my books again thinking they might not be interested. Then one day it occurred to me that I could use picture books in Upper Key Stage 2 too, as long as I use them effectively to draw them in and bring a different perspective. Here are some ideas I use in Key Stage 2 classrooms with my picture books. Maybe as a writer in schools or a teacher you might be able to use them too.

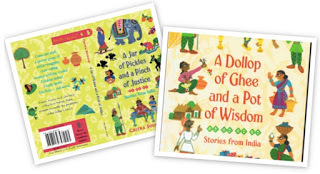

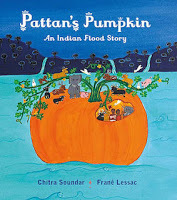

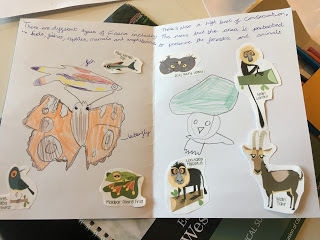

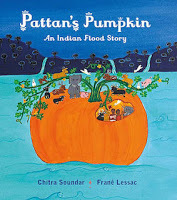

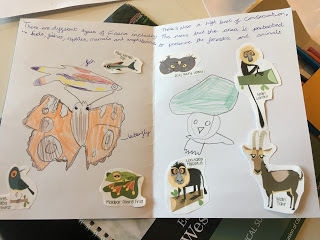

Idea #1: Convert my fictional story into a non-fiction activity I read the story aloud in class and then use the book as a jumping off point to discuss non-fiction that underpins the text. For example Pattan’s Pumpkin is the retelling of an ancient legend – but when I use it in KS2 classrooms, I engage the children in the setting – the beautiful UNESCO protected Sahaydri Mountain Range and talk about the fauna and flora of the region. I bring in some information sheets about the region, the animals etc and the class works in groups to create non-fiction booklets about the mountains, or animals or India depending on which topic interests them.

For example Pattan’s Pumpkin is the retelling of an ancient legend – but when I use it in KS2 classrooms, I engage the children in the setting – the beautiful UNESCO protected Sahaydri Mountain Range and talk about the fauna and flora of the region. I bring in some information sheets about the region, the animals etc and the class works in groups to create non-fiction booklets about the mountains, or animals or India depending on which topic interests them.

Of course teachers love this workshop too as it covers a bit of geography, science, reading and I sneak in a bit of Maths. Check out the teaching ideas I share with teachers here.

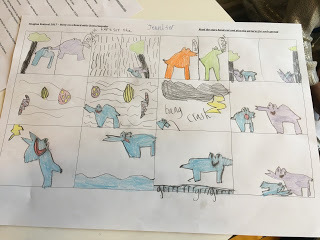

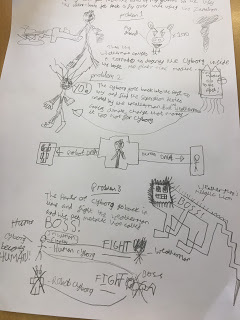

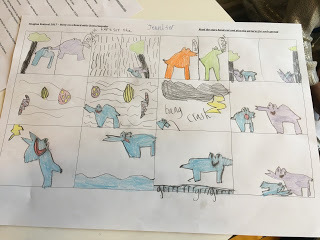

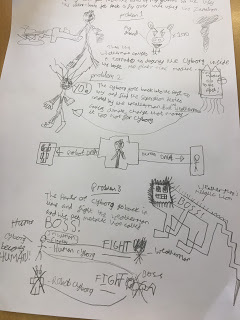

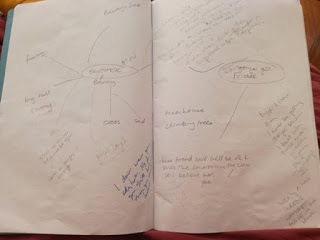

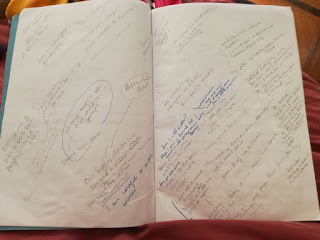

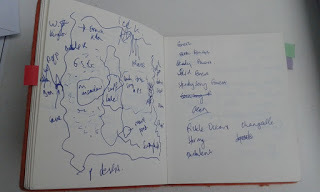

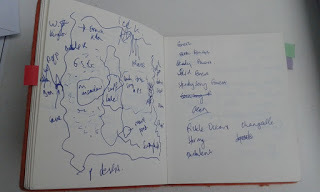

Idea #2: Picture Book Story Board WorkshopIn this workshop, I talk about the layout of a picture book as a writer. I show them my notebook where I break up text into spreads, draw boxes to figure out what might go into each spread. I talk about page-turns, exciting events and story mountains. Then I give each table a story that I am currently working on. Each group then designs the picture book turning into designers and illustrators. They have to break out my text into spreads and put illustrations and words into 12-box grid. Each group comes up with a different design and they love to compare and discuss their reasons.

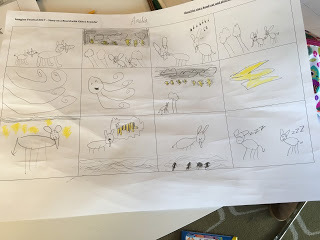

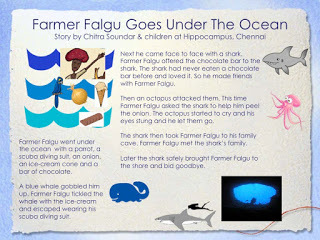

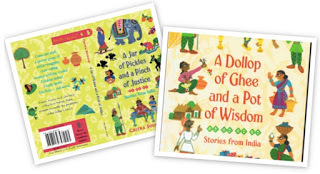

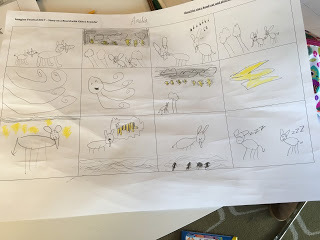

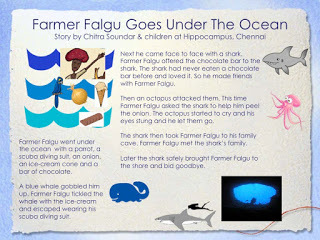

Idea #3: Plan Your Own Picture BookThis workshop is a combination of the other two. First I tell them a story from one of my picture books. Especially one that has a pattern – usually from one of the titles from the Farmer Falgu series. For example, in Farmer Falgu Goes to the Market, my character goes on a journey and encounters problems throughout his journey and in the end finds resolution.Then I invite the class to throw ideas into a big story salad. Can we make Farmer Falgu go somewhere else? Whom will he meet? What problems will he face? So far we have sent off Farmer Falgu to the moon, to the undersea and to alien planets. The children decide the characters Farmer Falgu meets, the obstacles in his way and the resolution.

For example, in Farmer Falgu Goes to the Market, my character goes on a journey and encounters problems throughout his journey and in the end finds resolution.Then I invite the class to throw ideas into a big story salad. Can we make Farmer Falgu go somewhere else? Whom will he meet? What problems will he face? So far we have sent off Farmer Falgu to the moon, to the undersea and to alien planets. The children decide the characters Farmer Falgu meets, the obstacles in his way and the resolution.

Some children of course then change course and find their own characters and that’s okay too. Once we have discussed the basics, then either in pairs or on their own, they plan their storyboard. Some develop the whole story while others enjoy telling the story to everyone else. Read more stories that were developed in classrooms here. The important thing is then the children engage with the picture book without guilt. They are often told they are too old for it. When they are allowed to, they enjoy it very much – but in a very different way.

The important thing is then the children engage with the picture book without guilt. They are often told they are too old for it. When they are allowed to, they enjoy it very much – but in a very different way.

So if you’re a picture book author who is nervous to go into older classes, you can move up from Reception, take off your costume and do workshops with the older kids too.

Chitra Soundar writes picture books and young fiction and is published in the UK, India, US and many other countries. Follow her on Twitter @csoundar and find out more about her at www.chitrasoundar.com.

Chitra Soundar writes picture books and young fiction and is published in the UK, India, US and many other countries. Follow her on Twitter @csoundar and find out more about her at www.chitrasoundar.com.

Notice the cap and the drums...When I get invited into schools, I usually have to do sessions with children from Reception to Year 6. Reception, Year 1 and Year 2 are perfect for the picture books. I tell stories, we make up stories together and they love reading from the picture books.Then for Year 3 and Year 4 – I read from my chapter books and discuss the stories for their inner meaning of justice and fairness. That’s all good.

Notice the cap and the drums...When I get invited into schools, I usually have to do sessions with children from Reception to Year 6. Reception, Year 1 and Year 2 are perfect for the picture books. I tell stories, we make up stories together and they love reading from the picture books.Then for Year 3 and Year 4 – I read from my chapter books and discuss the stories for their inner meaning of justice and fairness. That’s all good.

But what happens when I go into Year 5 and 6 classes? They are too old for my picture books and definitely not interested in my younger chapter books. At first I used to show my books for 30 seconds and then say, “I write for younger kids, let’s do some writing ourselves.” I would never bring out my books again thinking they might not be interested. Then one day it occurred to me that I could use picture books in Upper Key Stage 2 too, as long as I use them effectively to draw them in and bring a different perspective. Here are some ideas I use in Key Stage 2 classrooms with my picture books. Maybe as a writer in schools or a teacher you might be able to use them too.

Idea #1: Convert my fictional story into a non-fiction activity I read the story aloud in class and then use the book as a jumping off point to discuss non-fiction that underpins the text.

For example Pattan’s Pumpkin is the retelling of an ancient legend – but when I use it in KS2 classrooms, I engage the children in the setting – the beautiful UNESCO protected Sahaydri Mountain Range and talk about the fauna and flora of the region. I bring in some information sheets about the region, the animals etc and the class works in groups to create non-fiction booklets about the mountains, or animals or India depending on which topic interests them.

For example Pattan’s Pumpkin is the retelling of an ancient legend – but when I use it in KS2 classrooms, I engage the children in the setting – the beautiful UNESCO protected Sahaydri Mountain Range and talk about the fauna and flora of the region. I bring in some information sheets about the region, the animals etc and the class works in groups to create non-fiction booklets about the mountains, or animals or India depending on which topic interests them.

Of course teachers love this workshop too as it covers a bit of geography, science, reading and I sneak in a bit of Maths. Check out the teaching ideas I share with teachers here.

Idea #2: Picture Book Story Board WorkshopIn this workshop, I talk about the layout of a picture book as a writer. I show them my notebook where I break up text into spreads, draw boxes to figure out what might go into each spread. I talk about page-turns, exciting events and story mountains. Then I give each table a story that I am currently working on. Each group then designs the picture book turning into designers and illustrators. They have to break out my text into spreads and put illustrations and words into 12-box grid. Each group comes up with a different design and they love to compare and discuss their reasons.

Idea #3: Plan Your Own Picture BookThis workshop is a combination of the other two. First I tell them a story from one of my picture books. Especially one that has a pattern – usually from one of the titles from the Farmer Falgu series.

For example, in Farmer Falgu Goes to the Market, my character goes on a journey and encounters problems throughout his journey and in the end finds resolution.Then I invite the class to throw ideas into a big story salad. Can we make Farmer Falgu go somewhere else? Whom will he meet? What problems will he face? So far we have sent off Farmer Falgu to the moon, to the undersea and to alien planets. The children decide the characters Farmer Falgu meets, the obstacles in his way and the resolution.

For example, in Farmer Falgu Goes to the Market, my character goes on a journey and encounters problems throughout his journey and in the end finds resolution.Then I invite the class to throw ideas into a big story salad. Can we make Farmer Falgu go somewhere else? Whom will he meet? What problems will he face? So far we have sent off Farmer Falgu to the moon, to the undersea and to alien planets. The children decide the characters Farmer Falgu meets, the obstacles in his way and the resolution.

Some children of course then change course and find their own characters and that’s okay too. Once we have discussed the basics, then either in pairs or on their own, they plan their storyboard. Some develop the whole story while others enjoy telling the story to everyone else. Read more stories that were developed in classrooms here.

The important thing is then the children engage with the picture book without guilt. They are often told they are too old for it. When they are allowed to, they enjoy it very much – but in a very different way.

The important thing is then the children engage with the picture book without guilt. They are often told they are too old for it. When they are allowed to, they enjoy it very much – but in a very different way. So if you’re a picture book author who is nervous to go into older classes, you can move up from Reception, take off your costume and do workshops with the older kids too.

Chitra Soundar writes picture books and young fiction and is published in the UK, India, US and many other countries. Follow her on Twitter @csoundar and find out more about her at www.chitrasoundar.com.

Chitra Soundar writes picture books and young fiction and is published in the UK, India, US and many other countries. Follow her on Twitter @csoundar and find out more about her at www.chitrasoundar.com.

Published on April 02, 2017 23:00

March 26, 2017

BECOME A CELEBRITY AUTHOR IN 10 EASY STEPS - by Michelle Robinson

Michelle Robinson: successful

Michelle Robinson: successfulchildren's author and non-entityEvery time a celebrity puts their name to a children’s book, a professional author drops down dead. With celebs 'shutting us out of our trade', authors are heading toward extinction. It's hard not to feel bitter when your books aren't even stocked, let alone given their own pedestal. But sucking on sour grapes does not an attractive author make.

Chin up, chums! It's not all that bad. Besides, we ought to be flattered: the rich and famous want to be just like us. Can you blame them? We get to have 'a name' and hang around in our pyjamas all day, not being recognised in public. We'll never be considered too unfit or too wrinkly to do our jobs. Still, from where I'm sitting being rich and famous looks pretty appealing too...

How about we level the playing field and supplement our income with second jobs - as celebrities.

It's TOTES possible to be a successful celeb and brilliant author

It's TOTES possible to be a successful celeb and brilliant author

PUT THE ARGOS APPLICATION FORM DOWN.

You've already defied all odds to make it into print despite being a complete non-entity. If you can do that, you can do anything. A monkey with a typewriter can write a bestselling picture book and you can host the Brits! You're 10 steps away from a high profile second job that's WAY better paid than the one you've been busting a gut over. Take a shortcut to fame!

GET A SECOND CAREER AS A CELEB IN 10 EASY STEPS

This actually happened.Step 1: Look loadedYou'll need to speculate to accumulate. I know this is hard when regular children's authors don't make a lot of money, but if you're going to convince everyone you're worth squillions, you need to stop wearing rags. From now on, travel first class and invest in some half decent clothes. Men: buy a tailored smoking jacket, it's what Ant and Dec would do. Women: if we want to be taken seriously we’re going to have to start showing a little more flesh - no socks from now on.

This actually happened.Step 1: Look loadedYou'll need to speculate to accumulate. I know this is hard when regular children's authors don't make a lot of money, but if you're going to convince everyone you're worth squillions, you need to stop wearing rags. From now on, travel first class and invest in some half decent clothes. Men: buy a tailored smoking jacket, it's what Ant and Dec would do. Women: if we want to be taken seriously we’re going to have to start showing a little more flesh - no socks from now on.Step 2: Act confidentThe paparazzi won't shoot themselves - although you'll soon be wishing they would! Shoulders back, chest out. A shower wouldn’t hurt. Turn up the confidence a notch while you're at it and stop acting so grateful for having achieved your dreams. Demand the dream with a cherry on top. You’re worth it.

This man is probably writing

This man is probably writing a children's book as we speak.Step 3: Handle your own publicity

Once we’re famous we’ll have all the publicity we need - and more. Until then it’s a case of do-it-yourself. Try getting a mention on Steve Wright’s Sunday Love Songs or running down the high street naked. It doesn’t matter if your books don’t figure in any of this. At this stage all exposure is good exposure.

Step 4: Get 'legit'

You’re going to need a blue tick on Twitter and a squillion followers. Everyone knows you don’t necessarily come by thousands of adoring fans legitimately. Just like a top ten slot in the bestseller charts, you can simply buy a fanbase. This is not cheating; this is celebrity publishing. We’re going for quantity not quality.

Step 5: Bluff it

Nothing says ‘Paint me orange and feature me in Heat Magazine’ like wearing a huge pair of shades and a baseball cap down Lidl’s. Serendipitously you'll find these items readily available in store. Hop to it (and stop using clever, writerly words like 'serendipitously'). Note: it is acceptable to dress down when incognito, provided all loungewear is by Gucci.

These children's authors are all pictured on their way to their local indie bookshops to beg them to stock their books. Step 6: Create a stir

These children's authors are all pictured on their way to their local indie bookshops to beg them to stock their books. Step 6: Create a stir

Your cat will soon be as rich as you We can’t all be literary sensations, but we can all be sensational. Do something outrageous. It will give you material for that memoir you’ll finally have time to write in prison. Goodness knows you'll be too busy to write the rest of the time what with all those television appearances and international flights. Don't worry about your schedule; your PA will soon be organising everything for you, and you won't have to do school visits, ever again. With any luck you won't have to write anything ever again either - someone else will do it for you. You could even request a body double for all those top-billing lit fest events you'll be doing. Get in!

Your cat will soon be as rich as you We can’t all be literary sensations, but we can all be sensational. Do something outrageous. It will give you material for that memoir you’ll finally have time to write in prison. Goodness knows you'll be too busy to write the rest of the time what with all those television appearances and international flights. Don't worry about your schedule; your PA will soon be organising everything for you, and you won't have to do school visits, ever again. With any luck you won't have to write anything ever again either - someone else will do it for you. You could even request a body double for all those top-billing lit fest events you'll be doing. Get in!Step 7: Acquire a cute back story Sales and marketing departments love 'a hook'. Those lucky old celebs have them ready made. ‘Treasure in the Attic’s Wotsisface has treasure in HIS attic with new children’s book masquerading as pile of junk’. ‘Reclusive writer's cardigan provides refuge for rare moths’ isn’t going to cut the mustard. You and I are going to have to dig a little deeper to create eye catching headlines. Consider selling your own granny. Who cares if you're disinherited? Pretty soon you're going to be MINTED.

Step 8: Get a famous partnerRemember when Jools Oliver wrote a children's book? No? Oh. Well, a celebrity author is one thing, but a celebrity author with a celebrity partner is TWO THINGS. Photoshop yourself into a compromising situation with a celeb of your choosing. Don’t worry about being sued; you can settle out of court once you’ve made your first million.

Brightens texts and teeth! Step 9: Smile Coffee and red wine may help with the unsociable hours writing requires, but nobody wants to see their ill effects in HD. Tooth whitening is expensive and you’ve probably blown all your cash on a butler. Thankfully you are naturally creative and have a plentiful supply of Tippex. Say cheese!

Brightens texts and teeth! Step 9: Smile Coffee and red wine may help with the unsociable hours writing requires, but nobody wants to see their ill effects in HD. Tooth whitening is expensive and you’ve probably blown all your cash on a butler. Thankfully you are naturally creative and have a plentiful supply of Tippex. Say cheese!Step 10: Grow a thick skin Don’t expect to be welcomed to all those star-studded parties* with open arms. Those celebs didn’t just suddenly become children’s authors without putting in the hours. Okay, maybe some of them did. Still, if you should happen upon some children’s authors having a moan about the amount of non-entity authors selling loads of books, smile politely and find someone sympathetic to talk to. Like Madonna.*Orgies...? Take breath freshener.

See you on your luxury yacht, my friend!

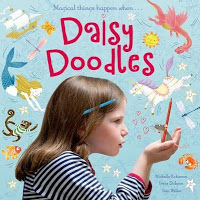

Michelle Robinson manages the tricky balancing act of being both a successful children’s author and a total non-entity. She has seven picture books publishing in the next six months - and still no invitation to appear on Oprah!

Michelle Robinson manages the tricky balancing act of being both a successful children’s author and a total non-entity. She has seven picture books publishing in the next six months - and still no invitation to appear on Oprah!‘Daisy Doodles’, illustrated by Irene Dickson with photography by Tom Weller, publishes with OUP in June 2017. p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 14.0px} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} span.Apple-tab-span {white-space:pre}

Published on March 26, 2017 22:30

March 20, 2017

Are you rich? by Jane Clarke

A couple of weeks ago, I was sent an email via my website, it didn't address me by name:

"I have a Fiction Story which I plan to Publish in UK. However, I do not have enough revenue to sponsor the idea. Hence I need a Partner that can assist me in this regard. If interested, You are to pay me 10,000 pounds which will entitle you to 50% of the royalties from the sales of the book after it has been publish.”

There are so many things wrong with this scenario, all I could do was smile as I hit the delete button. But, regardless of whether this is a scam or not, it has an underlying belief that all authors must be rich. It’s a belief that’s clearly shared by a lot of people I meet when I’m out and about doing author-ish things, and I’ve been out and about doing lots of author-ish things round World Book Day this month. The children I’ve seen are often up front enough to ask 'are you rich?’

My reply? "Yes! I have a new granddaughter. She's my third, I'm rich in granddaughters!"

One of the very precious things in my life

One of the very precious things in my life

But despite the underlying truth in that, it's a bit disingenuous.

So for the record, although I now have had over 80 books published, writing has not made me rich. This isn’t a moan, I love my job and I feel very privileged to earn my living from writing, but my current income is around what I would be earning if I was still teaching.

Happy author

Happy author

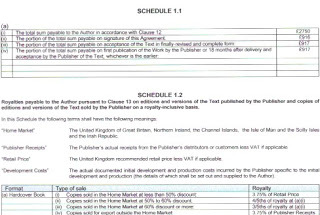

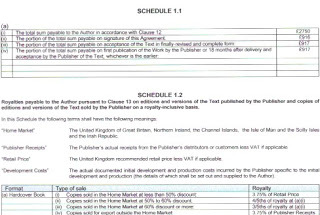

You may have heard of writers receiving a ’six figure advance.’ An advance is what is the publishers pay you in advance of the publication of your book. My most recent advance for a picture book text was for £2750 (paid in 3 instalments). After publication, once the publishers have recouped the costs of the book in question, I will earn royalties of 3.75 percent on each book sold (as long as they are not heavily discounted).

Some tedious details.

Some tedious details.

If a book does well, royalties may occasionally be in the thousands over the lifetime of the book, but that’s very rare - more often a book earns just a few pounds a year - or nothing when it goes out of print. It’s also hard to get picture books taken by publishers, I feel very lucky if I get one or two a year. I do other sorts of writing, like ghost writing and writing for reading schemes, and chapter books (all with smaller advances than for picture books) and school visits to supplement my income.

Having fun helping Reception class make up a story

Having fun helping Reception class make up a story

It’s no hardship or compromise, I really enjoy all these things. I think I have the best job in the world! In the UK, we’re fortunate to receive an annual payment from Public Lending Right (and lots of people borrow picture books from libraries, thank you, it all adds up!). A couple of times a year, there's a much smaller payment from the Authors Licensing and Collecting Society - if you register each title you get a tiny amount each time a poem or story is copied, broadcast or recorded by an institution that responsibly registers its use.http://www.alcs.co.uk.

Thanks to PLR and ALCs every little bit adds up.

Thanks to PLR and ALCs every little bit adds up.

Of course, there are a few exceptions who have made pots of money from children’s writing, but they are in a tiny minority. Much lower down the financial scale come the fortunate people like me who earn their living from children’s writing. But the majority of children’s writers and illustrators do not earn enough money to make a living from it, and don’t dare drop the day job.

So please don't assume any of us at the PictureBookDen are rolling in it. You're not rich, by the way, are you? If you have the odd £10,000 to spare, you're welcome to take my website correspondent up on that offer! :-)

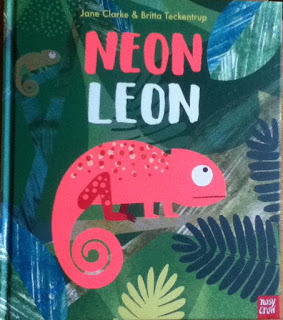

Jane’s latest picture book is Neon Leon, fabulously illustrated by Britta Teckentrup, who is almost certainly not rich either :-)

"I have a Fiction Story which I plan to Publish in UK. However, I do not have enough revenue to sponsor the idea. Hence I need a Partner that can assist me in this regard. If interested, You are to pay me 10,000 pounds which will entitle you to 50% of the royalties from the sales of the book after it has been publish.”

There are so many things wrong with this scenario, all I could do was smile as I hit the delete button. But, regardless of whether this is a scam or not, it has an underlying belief that all authors must be rich. It’s a belief that’s clearly shared by a lot of people I meet when I’m out and about doing author-ish things, and I’ve been out and about doing lots of author-ish things round World Book Day this month. The children I’ve seen are often up front enough to ask 'are you rich?’

My reply? "Yes! I have a new granddaughter. She's my third, I'm rich in granddaughters!"

One of the very precious things in my life

One of the very precious things in my lifeBut despite the underlying truth in that, it's a bit disingenuous.

So for the record, although I now have had over 80 books published, writing has not made me rich. This isn’t a moan, I love my job and I feel very privileged to earn my living from writing, but my current income is around what I would be earning if I was still teaching.

Happy author

Happy authorYou may have heard of writers receiving a ’six figure advance.’ An advance is what is the publishers pay you in advance of the publication of your book. My most recent advance for a picture book text was for £2750 (paid in 3 instalments). After publication, once the publishers have recouped the costs of the book in question, I will earn royalties of 3.75 percent on each book sold (as long as they are not heavily discounted).

Some tedious details.

Some tedious details.If a book does well, royalties may occasionally be in the thousands over the lifetime of the book, but that’s very rare - more often a book earns just a few pounds a year - or nothing when it goes out of print. It’s also hard to get picture books taken by publishers, I feel very lucky if I get one or two a year. I do other sorts of writing, like ghost writing and writing for reading schemes, and chapter books (all with smaller advances than for picture books) and school visits to supplement my income.

Having fun helping Reception class make up a story

Having fun helping Reception class make up a storyIt’s no hardship or compromise, I really enjoy all these things. I think I have the best job in the world! In the UK, we’re fortunate to receive an annual payment from Public Lending Right (and lots of people borrow picture books from libraries, thank you, it all adds up!). A couple of times a year, there's a much smaller payment from the Authors Licensing and Collecting Society - if you register each title you get a tiny amount each time a poem or story is copied, broadcast or recorded by an institution that responsibly registers its use.http://www.alcs.co.uk.

Thanks to PLR and ALCs every little bit adds up.

Thanks to PLR and ALCs every little bit adds up.Of course, there are a few exceptions who have made pots of money from children’s writing, but they are in a tiny minority. Much lower down the financial scale come the fortunate people like me who earn their living from children’s writing. But the majority of children’s writers and illustrators do not earn enough money to make a living from it, and don’t dare drop the day job.

So please don't assume any of us at the PictureBookDen are rolling in it. You're not rich, by the way, are you? If you have the odd £10,000 to spare, you're welcome to take my website correspondent up on that offer! :-)

Jane’s latest picture book is Neon Leon, fabulously illustrated by Britta Teckentrup, who is almost certainly not rich either :-)

Published on March 20, 2017 00:00

March 13, 2017

Practising What You Preach in School Author Visits: Mindfulness, Mistakes and Early Picture Book Drafts by Juliet Clare Bell

During a school visit, have you ever been talking about your writing process and a great top tip for writing... and then found yourself thinking “what a great idea! I should do that.” ? And you realise that you’ve not actually done it (or that your writing process has strayed away from what you’re describing) recently…

Maybe I’m the only one, but I suspect not. And the time around World Book Day, usually the busiest time of the year for author visits, is a good time to listen carefully to what you’re saying to others and making sure that you practise what you preach.

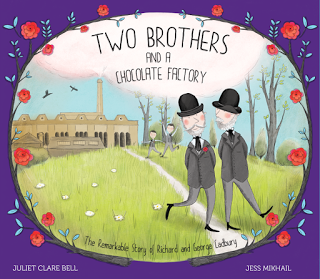

I am currently going into one school for two days a week over a five-week period, where amongst other things, I am practising and discussing mindfulness with the children and how mindfulness can help us in our everyday lives and when we are writing. Jess Mikhail (who illustrated Two Brothers and a Chocolate Factory) is doing the same with illustration.

I'm lucky enough to be working on a mindfulness and writing/art project with Jess Mikhail, after having worked with her on Two Brothers and a Chocolate Factory: The Remarkable Story of Richard and George Cadbury, above.

I have practised mindfulness, on and off, over the last twenty five years, and it’s been extremely useful, but I hadn’t used it much over the past ten years and not deliberately when writing.

One of the things we’ve focused on a lot in the school is making mistakes and taking risks and trying to encourage children to embrace their mistakes and feel better about making them. If you’re afraid to get things wrong, you’re unlikely to take risks in your work (or life) because of the fear of failing at something. So we’ve been using mindfulness to try and feel better about getting things wrong.

There’s a great clip for children from Kung Fu Panda that deals simply with trying to remain present. It might feel a bit corny to an adult but it’s quite easy to grasp and the children pick it up pretty easily:

Clip from Kung Fu Panda (directed by Mark Osborne and John Stevenson)

And one way of feeling ready to take risks and make mistakes is by being in the present –and not worrying about the past (how you felt when you made mistakes before) or the future (what might people think of you if you do something that’s wrong?).

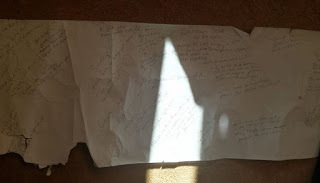

So I’ve shown them my very messy, rough plans for my stories –on messy paper, where I’m not censoring my ideas but getting everything I’m thinking down onto paper before I try and actively shape it. And I talk about how it not being in a beautiful notebook makes it easier for me not to worry about messing up something that’s clean and fresh and beautiful.

Scrappy planning for a picture book of mine, which I share with surprised (and amused/horrified) children.

I’ve given them each a lovely clean sheet of blank A4 paper and then got them to scrumple it up, jump on it, rip it and then use it so it feels less like something that it would feel bad to make a mistake on. And then we’ve made deliberate mistakes on the page –it can be surprisingly hard to write your name wrong, but we do, and then we write sentences where the structure is clearly wrong –and then talk about how we feel about doing it.

Children writing their own names wrong and coming up with sentences that are grammatically wrong, on scrumpled up and jumped on paper...

And they love the book, Beautiful Oops, by Barney Saltzberg, which celebrates the mistakes we makes and shows us how to make the most of them

Beautiful Oops, by Barney Saltzberg

So I hope we’re now at the point where the children are feeling more inclined to take risks and make mistakes in their writing and art throughout the rest of the project –and beyond.

But am I practising what I preach?

Well, in terms of being messy and writing on big scrappy paper and not censoring my thoughts as I’m planning, then yes. That’s definitely how I work. And taking risks? Every time I show my work to anyone –whether it’s my agent, my editor or another writer, I’m taking a risk. All authors do it -so yes, again. But in terms of being mindful and trying to be present as much as possible, especially when writing?

I’ve tried. Since we arranged the project many months ago and whilst I’ve been thinking about the project, I have tried to be practise mindfulness with my writing more often. With my most recent story, I actually tried a different way of writing the first draft of the manuscript –with mindfulness very much in mind.

I am writing a picture book on a very sensitive subject. It’s a story about a girl whose older brother gets sick and then dies. There are all sorts of expectations about the book and I do feel a real responsibility to get it right as the people who will read it will be very vulnerable. Whilst I was researching the book, interviewing bereaved parents and doing creative work (for their own books) with bereaved and pre-bereaved siblings, and with young people with life-limiting conditions, I made no notes for my story at all. But I immersed myself in what I was doing and tried to be as ‘present’ as I could be. When it came to writing the first draft, I did make a scrappy mind map one morning (between 6 and 7 am, when I can focus best, without distraction)

and then the following morning, I wrote my story. But the story felt fragile and I’d deliberately not thought about it too much. I wanted to be as focused as I could without distraction so I tried something new:

I wrote it in the dark.

I had to have just enough light so that I could see that I wasn’t writing lines directly on top of other lines, but I only even glanced down at the unreadable page when I’d got to the end of each line, just to be sure there was some space between the lines:

Written in the dark (at what turns out to be a not very horizontal angle)

And the results?

In terms of focusing on the present, and reducing distractions (as we’re trying to encourage the children to do), I was much better able

To focus: I don’t visualise things so in the dark, I don’t have any images or colour and I can’t be distracted by seeing any objects around me

To keep going: I couldn’t read what I’d written so I wasn’t immediately being distracted from my task of keeping on writing by being tempted to edit words or phrases that I’d just written

Not to worry about mistakes: because I couldn’t see them!

I can find myself easily distracted when writing but practising mindfulness and being able to focus like this actually worked really well for me. And interestingly, the story written this way has needed far less editing than a lot of my stories.

School visits are valuable in many ways, but this school project has been helpful in an unexpected way: because of the particular project I’ve really had to go away and practise what I preach. And for me, at least, it’s worked.

Have you tried any unusual ways of writing –as an experiment, or so you can focus properly? Or have you tried other things to help you focus? And how have school visits helped you as an author? Please leave a comment, below.

www.julietclarebell.com

Published on March 13, 2017 07:29

March 5, 2017

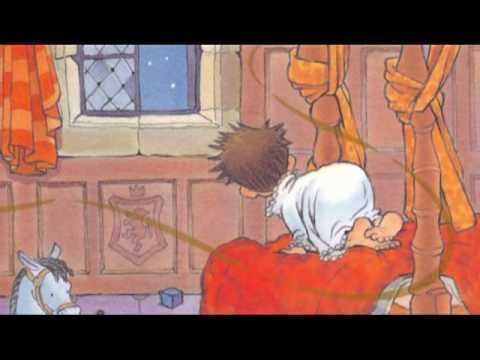

School Visits for Infant Years by Abie Longstaff

It's March. School visit season. So if you see raggedy authors looking exhausted, pulling large bags behind them please smile at us in sympathy.

For me, school visit season is both the most exciting and the most knackering time of year. It's the time when I step away from my computer and go to see my audience. It's wonderful to find that the world you created in your head really resonates and impacts on kids. And there's nothing better than seeing children dressed up as your character.

Kittie Laceys on World Book Day But school visits can be really stressful and tiring, I cover Reception to Year 6, and each year has its own particular needs. KS1 is an age group that few authors cover (we PictureBookDenners are a rare breed) and I often get phone calls from panicked author friends saying 'Help! I have to talk to Reception - what do I say?' Here are some tips for the picture book age group.

Kittie Laceys on World Book Day But school visits can be really stressful and tiring, I cover Reception to Year 6, and each year has its own particular needs. KS1 is an age group that few authors cover (we PictureBookDenners are a rare breed) and I often get phone calls from panicked author friends saying 'Help! I have to talk to Reception - what do I say?' Here are some tips for the picture book age group.

1. Timing4 year olds do not sit still for long. 30-40 minutes is about right.

2. SizeLarge groups can be intimidating for small children. It's better to do multiple sessions repeated in each Reception class, rather than put all the year group together into a hall.

3. TechnologyPut the book up on the interactive whiteboard so that all the children can see the illustrations clearly. If you read from your lap the kids will jostle and wriggle to get a closer view.

4. Make your session interactive

Ask questions, do noises and silly voices, ask children to bark like a dog or cackle like a witch. The more they are involved the more they'll listen.

5. Dress up

Kids love outfits, wigs and costumes.

Fairytale Hairdresser skirt

Fairytale Hairdresser skirt

Fairytale Hairdresser hair

Fairytale Hairdresser hair

6. Bring propsThis age group is very tactile. They love to hold things. Bring soft toys or objects that go with your book. Bottles for Magic Potions Shop

Bottles for Magic Potions Shop

Rapunzel hair to try on

Rapunzel hair to try on

Dolls waiting to have their hair done7. Show them your mistakes

Dolls waiting to have their hair done7. Show them your mistakes

I bring my sketchbooks and notebooks and show children how messy I am and how many times I need to re-write until I get it right.

8. Tell them about you

Kids love to hear about where you live and work

My writing hut9. Get them creatingThis age group is old enough to plot very simple stories.I show them a scrapbook with animals in and together we invent a story about a character. Pick a photo where an animal is doing something exciting or showing a strong emotion.The Comedy Wildlife Awards has great pictures you could use.

My writing hut9. Get them creatingThis age group is old enough to plot very simple stories.I show them a scrapbook with animals in and together we invent a story about a character. Pick a photo where an animal is doing something exciting or showing a strong emotion.The Comedy Wildlife Awards has great pictures you could use.

10. Structure your event

I asked picture book author Alex English ('Yuck! said the Yak') how she organises her infant events. She said:

'I'd suggest splitting your workshops into lots of sections so that there is a variety of activities - listening to stories, getting up and being active, colouring, cutting and sticking, writing a poem together (with you writing on the board). Then you can do as many or as few bits as you can fit in - it can be very hard to judge how long things will take them or how quickly they will start to get bored!'

11. 'Questions'The questions from this age group are not really questions. They are more of a chat. One little boy put his hand up to tell me 'I had pineapple for breakfast'. This is the kind of interaction you should expect. It's VERY cute and I love having little chats with all the kids.

12. What can illustrators do?

Hannah Shaw ('Bear on a Bike') advises:

‘I do live-drawing, and I make my talk much more about the illustration side. I prepare rhymes, riddles and jokes, as well as a 'making' or drawing thing linked to the book. The children love any kind of craft activity and I often give them a fun worksheet for them to colour in or add to.’

13. Relax and enjoy itI love this age group! They are always so excited and enthusiastic. My main problem is gently peeling them off me when they've been cuddling me for a bit too long.

Please add your tips below - I'd love to hear how you cope.

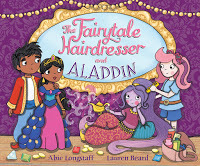

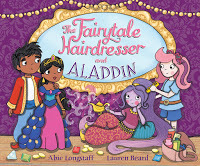

Abie's latest book is The Fairytale Hairdresser and Aladdin - out on 9th March!

For me, school visit season is both the most exciting and the most knackering time of year. It's the time when I step away from my computer and go to see my audience. It's wonderful to find that the world you created in your head really resonates and impacts on kids. And there's nothing better than seeing children dressed up as your character.

Kittie Laceys on World Book Day But school visits can be really stressful and tiring, I cover Reception to Year 6, and each year has its own particular needs. KS1 is an age group that few authors cover (we PictureBookDenners are a rare breed) and I often get phone calls from panicked author friends saying 'Help! I have to talk to Reception - what do I say?' Here are some tips for the picture book age group.

Kittie Laceys on World Book Day But school visits can be really stressful and tiring, I cover Reception to Year 6, and each year has its own particular needs. KS1 is an age group that few authors cover (we PictureBookDenners are a rare breed) and I often get phone calls from panicked author friends saying 'Help! I have to talk to Reception - what do I say?' Here are some tips for the picture book age group.1. Timing4 year olds do not sit still for long. 30-40 minutes is about right.

2. SizeLarge groups can be intimidating for small children. It's better to do multiple sessions repeated in each Reception class, rather than put all the year group together into a hall.

3. TechnologyPut the book up on the interactive whiteboard so that all the children can see the illustrations clearly. If you read from your lap the kids will jostle and wriggle to get a closer view.

4. Make your session interactive

Ask questions, do noises and silly voices, ask children to bark like a dog or cackle like a witch. The more they are involved the more they'll listen.

5. Dress up

Kids love outfits, wigs and costumes.

Fairytale Hairdresser skirt

Fairytale Hairdresser skirt

Fairytale Hairdresser hair

Fairytale Hairdresser hair6. Bring propsThis age group is very tactile. They love to hold things. Bring soft toys or objects that go with your book.

Bottles for Magic Potions Shop

Bottles for Magic Potions Shop

Rapunzel hair to try on

Rapunzel hair to try on Dolls waiting to have their hair done7. Show them your mistakes

Dolls waiting to have their hair done7. Show them your mistakesI bring my sketchbooks and notebooks and show children how messy I am and how many times I need to re-write until I get it right.

8. Tell them about you

Kids love to hear about where you live and work

My writing hut9. Get them creatingThis age group is old enough to plot very simple stories.I show them a scrapbook with animals in and together we invent a story about a character. Pick a photo where an animal is doing something exciting or showing a strong emotion.The Comedy Wildlife Awards has great pictures you could use.

My writing hut9. Get them creatingThis age group is old enough to plot very simple stories.I show them a scrapbook with animals in and together we invent a story about a character. Pick a photo where an animal is doing something exciting or showing a strong emotion.The Comedy Wildlife Awards has great pictures you could use.10. Structure your event

I asked picture book author Alex English ('Yuck! said the Yak') how she organises her infant events. She said:

'I'd suggest splitting your workshops into lots of sections so that there is a variety of activities - listening to stories, getting up and being active, colouring, cutting and sticking, writing a poem together (with you writing on the board). Then you can do as many or as few bits as you can fit in - it can be very hard to judge how long things will take them or how quickly they will start to get bored!'

11. 'Questions'The questions from this age group are not really questions. They are more of a chat. One little boy put his hand up to tell me 'I had pineapple for breakfast'. This is the kind of interaction you should expect. It's VERY cute and I love having little chats with all the kids.

12. What can illustrators do?

Hannah Shaw ('Bear on a Bike') advises:

‘I do live-drawing, and I make my talk much more about the illustration side. I prepare rhymes, riddles and jokes, as well as a 'making' or drawing thing linked to the book. The children love any kind of craft activity and I often give them a fun worksheet for them to colour in or add to.’

13. Relax and enjoy itI love this age group! They are always so excited and enthusiastic. My main problem is gently peeling them off me when they've been cuddling me for a bit too long.

Please add your tips below - I'd love to hear how you cope.

Abie's latest book is The Fairytale Hairdresser and Aladdin - out on 9th March!

Published on March 05, 2017 23:16

February 26, 2017

Openings with a Promise – the Emotional Journey of Your Character

I love it when as a writer you realize that other creative people face similar struggles or challenges with their craft. Like when I attended the SCBWI conference in LA last summer, I was heartened to hear how Drew Daywalt, the author of the NY Times bestselling The Day the Crayons Quit, waited six years for his agent to find a publisher who ‘got’ his book and wanted to publish it.

The Day the Crayons Quit

The Day the Crayons Quit by Drew Daywalt and Oliver Jeffers

Or like how Jon Klassen of I Want My Hat Back fame was stuck because:

“… I had a problem in that I didn’t like drawing characters. I like drawing scenery and inanimate objects and I especially liked it back then. The challenge of making a piece where the subject wasn’t a living thing was really fun, and I liked how quiet the effect was.”

I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen

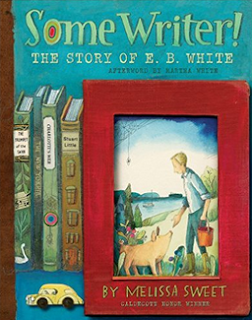

I Want My Hat Back by Jon KlassenI recently received a gift. It was one of my favourite kinds of books – the story of a fellow writer. As I savoured the book, its pages, beautifully designed windows into E.B. White’s life and writing, I realized a few things:

Some Writer! The Story of E.B. White

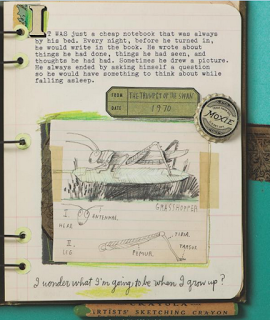

by Melissa Sweet • E.B. White kept a journal and he finished each entry by asking himself a question that he could think about as he was drifting off to sleep.

from Some Writer! The Story of E.B. White by Melissa Sweet

from Some Writer! The Story of E.B. White by Melissa Sweet Yes! This is such a good technique – to mull the questions of the day, of the story, of a stuckness that becomes unstuck in the subconscious of slumber. I love to do that too!

• In his column One Man’s Meat for Harper’s Magazine, he wrote in 1982 about the influence of moving to a farm in Maine, where “confronted by new challenges, surrounded by new acquaintances – including the characters in the barnyard who were later to appear in Charlotte’s Web – I was suddenly seeing, feeling, and listening as a child sees, feels and listens”.

from Some Writer! The Story of E.B. White by Melissa Sweet

from Some Writer! The Story of E.B. White by Melissa SweetI thought about this. As I read on . . .

• It took E.B. White a year of revisions to settle on the iconic opening for Charlotte’s Web.

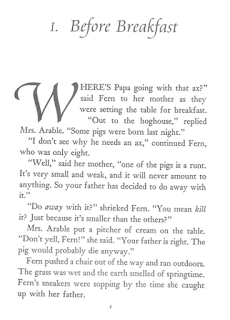

Charlotte's Web by E.B. White, illustrated by Garth Williams,

Charlotte's Web by E.B. White, illustrated by Garth Williams,published 1952

In Some Writer!, Sweet includes images of White's original manuscripts, complete with crossings-out and musings in the margins.

I learned that E.B. White tried at least six different tacks to nail the opening of his most famous book. First:

“Charlotte was a grey spider who lived in the doorway of a barn.”

Then: “I shall speak first of Wilbur.”

Then: “A barn can have a horse in it, and a barn can have a cow in it, and a barn can have hens scratching the chaff and swallows flying in and out through the door – but if a barn hasn’t got a pig in it, it is hardly worth talking about.”

After a year, White wrote: “At midnight, John Arable pulled his boots on, lit a lantern, and walked out the hoghouse.”

Next, he cut to the action: “Where’s Papa going with that hand ax?”

Which was shortened to: “Where’s Papa going with that ax?”

opening chapter from Charlotte's Web by E.B. White

opening chapter from Charlotte's Web by E.B. WhiteI was struck by this journey to find the way into the story. The story was there all along, wasn’t it, but it was only when White cut to the emotional core of the characters’ emotional journey and told it like child might experience it that it felt right.

In previous blogs about creating compelling openings and using “show, don’t tell”, I wrote about the importance of:

• showing readers through the character’s body language, action and dialogue

• including the answers to the questions who, what and where to create a compelling opening

• clear character motivation – why?

• creating vivid, detailed scenes

But, connecting these elements with

• the promise of the characters’ emotional journey and

• “seeing, feeling, and listening” like a child

is what will really hook readers into the story and get them to keep turning the pages.

When we read the opening line of Charlotte’s Web, these elements come together almost effortlessly. But the weren’t effortless at all . . .!

E.B. White with his beloved dog

E.B. White with his beloved dog Wow, some writer! ________________________

Natascha Biebow

Author, Editor and Mentor

Blue Elephant Storyshaping is an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Check out my small-group coaching Cook Up a Picture Book courses! Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles.

Blue Elephant Storyshaping is an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Check out my small-group coaching Cook Up a Picture Book courses! Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles.

Published on February 26, 2017 19:30

February 19, 2017

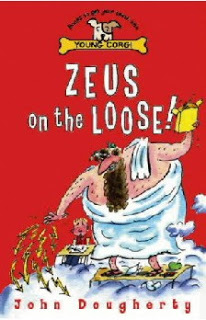

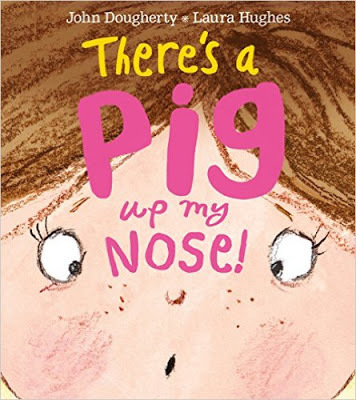

How the Pig Got Published • John Dougherty

A big THANK YOU to guest blogger John Dougherty for this post that shows how perseverance can pay off in picture book publishing.

Like many children’s writers, I used to be a teacher. And like many children’s writers, I probably wouldn’t be a professional author now if I hadn’t been a teacher first.

Like many children’s writers, I used to be a teacher. And like many children’s writers, I probably wouldn’t be a professional author now if I hadn’t been a teacher first.A week of my pre-teacher training course classroom observations was spent with a teacher who told me, “If you're going to teach children, you need to read children’s books,” and who sent me home with some reading: Gene Kemp; Dick King-Smith; a different author every night. On the course itself, an entire module examined ways to use children’s books in our teaching, introducing me as it did so to the likes of Anthony Browne, Jeanne Willis and Tony Ross. It wasn’t long before I found myself devouring children’s books and thinking, “These are great - I wonder if I could write one?”

Teaching being as all-consuming as it is, I was, for a while, too creatively drained to be able to try any actual writing. But in my third year, my imagination was given a nudge by my pupils and some of their idiosyncrasies, and I ended up writing a number of what I hoped were picture-book manuscripts. My favourite of the bunch was inspired by Suganthi, a sparky little girl with a very snorty laugh; I’d taken to teasing her that she had a pig up her nose, and this prompted a story of a girl who, well, had a pig up her nose.

The reaction from publishers and agents was fairly consistent: these made us laugh, but they’re not what we’re looking for at the moment. But one editor - Sue Cook at Random House - went on to say, “I like the flavour of your writing, and I’d be interested in seeing anything else you’ve written.”

To cut a long story short, that was my break. Over the next few years Sue gave me feedback on everything I sent her, suggested I have a go at writing chapter books for newly emergent readers, and finally, when I sent her Zeus on the Loose, offered me my first deal.

I love being a published author, and I’m very proud of my work to date. But I started off trying to write picture books, and for years I wondered why none of the picture book manuscripts I’d written had ever been published. I’ve still got a growing pile of them, and every now and then my lovely agent Sarah would send one of them out… but nothing. Just an addition to the great big pile of nope that I keep under my desk. Until a couple of years ago, when, Sarah having retired, my new lovely agent Julia asked me, “Anything in the bottom drawer we could try sending out again?”

Well, to cut another long story short, Egmont - the very first publisher to whom Julia sent There’s a Pig Up My Nose - went mad for it. Absolutely loved it; made us an offer; secured the services of the fabulous Laura Hughes to do the illustrations. And since publication in January, it’s been getting all the love - a great review in The Guardian, Nicolette Jones’s Children’s Book of the Week in the Sunday Times…

I have no idea what made the difference. Why did it get virtually no attention from anyone twenty-one years ago, yet an almost instant deal and broadsheet reviews all this time later? I can guess, of course, as can any of us, but there’s really no way of knowing. Perhaps ridiculous humour was just unfashionable in children’s publishing then, but is in vogue now. Perhaps it just landed on the right person’s desk this time round.

Whatever the reason, it’s another reminder of the lesson most of us, as authors, keep coming back to: persevere. If you believe in a story, don’t give up on it, because some day someone else may agree with you about it.

Of course, Suganthi and the other children in that Year Three class at Hillbrook Primary school will be all grown up now. But I hope that some of them will come across There’s a Pig Up My Nose in a bookshop or a library somewhere, and recognise my name, and read it to their own children. And I hope that whatever they’re doing, they too will have learned the lesson of persistence.

John’s website is at www.visitingauthor.com and you can follow him on Twitter @JohnDougherty8. There’s a Pig Up My Nose, illustrated by Laura Hughes and published by Egmont, is his latest book.

Published on February 19, 2017 22:00

February 12, 2017

Building Bridges Through Picture Books, by Pippa Goodhart

As our world divides, and distrust between different peoples seems to be growing, our children need to learn to do better than us. That will only come through understanding and communication between cultures. This has set me thinking about the few occasions when my story text has been illustrated by an artist from a different culture.

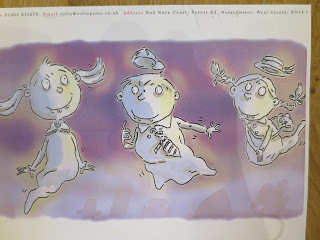

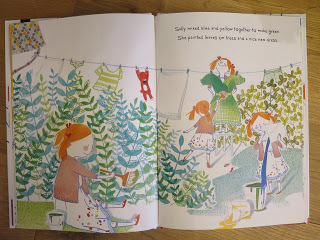

The first time was when I wrote a silly rhyming story about Three Little Ghosties who like to bully ghoulsies, witches and ogres. They are about to scare a human child … when the child wakes up and scares them instead. I had a particular British illustrator in mind for this book. Colin Paine did these lovely roughs ...

… but Bloomsbury appointed an Italian illustrator, Anna Cantone, to do the final illustrations. She used collage to produce very ‘designery’ images (please excuse the badly lit photo!). I wasn't sure about them to begin with. And yet I’ve come to love them. Why? Well, largely because young children react to them so well! (NB This book is now out of print).

I’ve had books illustrated, published and sold in South Korea, and those have surprised me by showing children who look more British than Korean to me.

I asked my fellow Picture Book Den contributors what experiences they had in working with writers or illustrators from other cultures, and only Jonathan Emmett had experience of working this way. He told me …

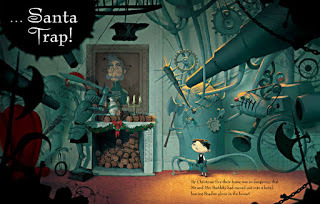

It took three years to find a suitable illustrator for my picture book story, The Santa Trap and I’d almost given up hope of ever finding one when my editor Emily Ford discovered Argentinian illustrator Poly Bernatene. Poly brought a distinctly South-American Gothic feel to the illustrations that was a perfect fit for the dark, cautionary tale.

Poly’s English is pretty good these days (and certainly puts my miserable Spanish to shame) but back then his wife Paula translated the story’s text and Emily’s email correspondence so that the language difference did not seem to present too much of a problem. We’ve since done three more books together and are hoping to do a fifth. Although Poly can sometimes interpret my words in a way that I hadn’t intended, this often leads to interesting and appealing results.

That highlights one obvious problem; language differences. And yet translation of short texts isn't hard. Perhaps there should be more cross-cultural cooperation?

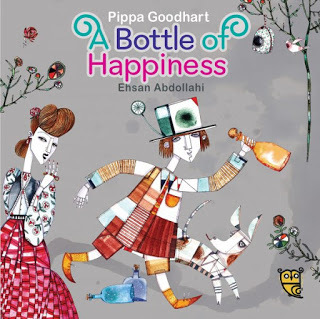

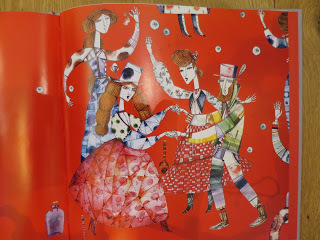

There is! Tiny Owl Publishing have recently launched an exciting and innovative move to publish children’s picture books which ‘bridge cultures’, specifically between Iran and Britain. They asked me to write a fable for an Iranian illustrator to work on. So I wrote A Bottle of Happiness, and, remarkably quickly, there was my story made into the most beautiful and, to me, initially slightly strange images by Ehsan Abdollahi.

As with Three Little Ghosties, I wondered whether the style would be too sophisticated and strange to British children’s view, but not a bit of it! More fool me for underestimating them. Of course ALL styles, indeed the whole world, is new to a small child, so they naturally tend to be more open to new ideas than we adults might give them credit for.

In our modern world, we need to know facts about each other, but I strongly believe that we also need to have a proper feel for, and familiarity with, each other’s worlds and outlooks. We need to share cultures.

My father, who was a lovely and wise man, used to say that the point of education was to give us more things in life to enjoy. Well, having access to the beauty and insights of other cultures certainly gives us more things to enjoy. So let’s give that joy to our children!

Published on February 12, 2017 16:30

February 6, 2017

Want to get published? Five rules of what not to do - Lynne Garner

When I submitted my first picture book manuscript I knew nothing about the industry, I just knew I wanted to write picture books. I'd proved I could write non-fiction as I'd had features and non-fiction books published. However picture books was one of those bucket list things, so I decided to give it a go. Not surprisingly I received a lot of rejections and along with some of those rejections I received a little advice from editors (which is uncommon, they simply don't have the time, so their comments were much appreciated). So I decided to study and signed up for a distance writing course. I started to submit my work and although I received positive feedback I also received notes, similar to those I'd received from editors.

So in the spirit of sharing here are the five rules I've drawn up based on the feedback I've received over the years.

Rule one:

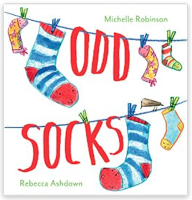

Don't write about inanimate objects, especially those that talk. Talking and thinking inanimate objects is old fashioned. Children don't like to be 'talked down' to so they won't believe that inanimate objects can have a life of their own. So talking socks - oh no talking socks would never make a good story.

An epic adventure that starts

An epic adventure that starts

in a sock drawer.Rule two:

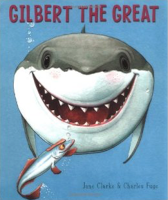

Don't write about things considered to be 'adult' topics things like death, disability, bullying etc. So nothing like Gilbert the Great which deals with the lose of a friend - that'd never reach the shelves.

Gilbert The Great White Shark

Gilbert The Great White Shark

loses a friend.

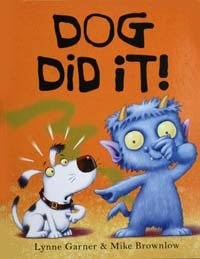

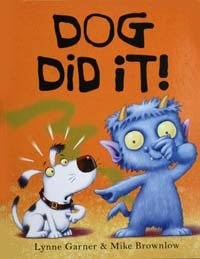

Rule three:Never ever write about a character that is not cute. Children and adults can't bond with un-cute characters, they want a character that has the arrr! factor.

Trolls aren't cute but I think I got away with it because

Trolls aren't cute but I think I got away with it because

this story relies on humour.

Rule four:

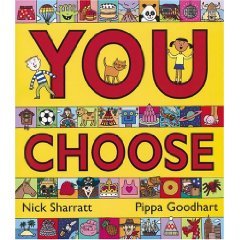

If you want your story to be published then it should have a 'proper' story arch with a beginning, middle and end. One where your character changes, gains or learns something. So a book where you make choices on behalf of the character would never get published.

Well it does work and so well that this title has been

Well it does work and so well that this title has been

followed by another including colouring books. Rule five:

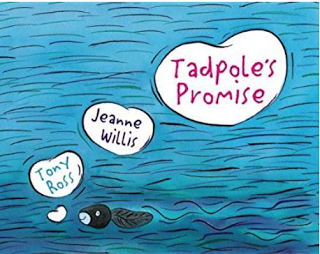

Your story should always have a happy ending. Leave your reader feeling positive. There's enough sadness in the world, so you don't have to introduce it to young readers in a book.

You'd never think a picture book where one of the main

You'd never think a picture book where one of the main

characters eats the other would work, but it does.

So now you know the rules guess what? Go on break them! If it worked for these authors then it might work for you.

Mmmm what rule can I go and break?

Lynne

Now for a blatant plug, so please feel free to stop reading now:

My latest short story collection Coyote Tales Retold is available on Amazon in ebook format. Also available Meet The Tricksters a collection of 18 short stories featuring Anansi the Trickster Spider, Brer Rabbit and Coyote is available as a paper back and an ebook.

I run the following online courses for Women On Writing:

How to write A children's book and get published

5 picture books in 5 weeks

How to write a hobby-based how to book

So in the spirit of sharing here are the five rules I've drawn up based on the feedback I've received over the years.

Rule one:

Don't write about inanimate objects, especially those that talk. Talking and thinking inanimate objects is old fashioned. Children don't like to be 'talked down' to so they won't believe that inanimate objects can have a life of their own. So talking socks - oh no talking socks would never make a good story.

An epic adventure that starts

An epic adventure that starts in a sock drawer.Rule two:

Don't write about things considered to be 'adult' topics things like death, disability, bullying etc. So nothing like Gilbert the Great which deals with the lose of a friend - that'd never reach the shelves.

Gilbert The Great White Shark

Gilbert The Great White Shark loses a friend.

Rule three:Never ever write about a character that is not cute. Children and adults can't bond with un-cute characters, they want a character that has the arrr! factor.

Trolls aren't cute but I think I got away with it because

Trolls aren't cute but I think I got away with it becausethis story relies on humour.

Rule four:

If you want your story to be published then it should have a 'proper' story arch with a beginning, middle and end. One where your character changes, gains or learns something. So a book where you make choices on behalf of the character would never get published.

Well it does work and so well that this title has been

Well it does work and so well that this title has beenfollowed by another including colouring books. Rule five:

Your story should always have a happy ending. Leave your reader feeling positive. There's enough sadness in the world, so you don't have to introduce it to young readers in a book.

You'd never think a picture book where one of the main

You'd never think a picture book where one of the maincharacters eats the other would work, but it does.

So now you know the rules guess what? Go on break them! If it worked for these authors then it might work for you.

Mmmm what rule can I go and break?

Lynne

Now for a blatant plug, so please feel free to stop reading now:

My latest short story collection Coyote Tales Retold is available on Amazon in ebook format. Also available Meet The Tricksters a collection of 18 short stories featuring Anansi the Trickster Spider, Brer Rabbit and Coyote is available as a paper back and an ebook.

I run the following online courses for Women On Writing:

How to write A children's book and get published

5 picture books in 5 weeks

How to write a hobby-based how to book

Published on February 06, 2017 00:43

January 30, 2017

The World of the Weird Versus The Weird in the World - Timothy Knapman

I don’t know about you, but I’ve never had much time for the kitchen sink. By “kitchen sink”, I don’t mean the sink-shaped thing you find in a kitchen with taps, plughole and draining board attached. I’m a writer, after all. I drink tea. Lots of tea. From mugs. Mugs that need – eventually – to be hosed down and scraped clean so they can contain yet more tea.

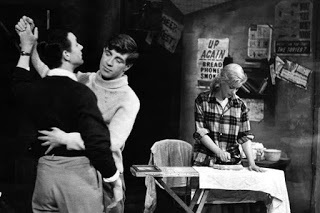

No, I mean naturalism, realism, whatever you want to call it: the attempt to create in art a faithful replica of the surface detail of real life - the sort of thing “kitchen sink” novelists and playwrights such as Alan Sillitoe, David Storey and John Osborne were doing in the 1950s.

John Osborne’s “kitchen sink” drama “Look Back In Anger” – though perhaps it’s better described as an “ironing board” drama

John Osborne’s “kitchen sink” drama “Look Back In Anger” – though perhaps it’s better described as an “ironing board” drama

I admire the skill, of course - and the compassionate and campaigning impulses behind it - but a bit of me is always thinking: why should I go out to see a play about alcoholism, despair, poverty and unemployment? I can get all that at home.

(I feel much the same about 3D movies. Why should I pay extra for a 3D movie? I get 3D all the time! Life is in 3D! It’s 2D that’s the novelty! But I digress...)

As a child, I was always drawn to the strange, the funny, the macabre – in short, the weird. I loved Doctor Who and Star Wars and Monty Python: aliens, robots and Terry Jones showing his bottom. So when I started writing for children, of course, it was the fantastical, the odd, the bizarre, that I wanted to write about.

The anxiety of influence: Terry Jones’s bottom

The anxiety of influence: Terry Jones’s bottom

And children are the perfect audience for fantasy because not only do they spend a lot of time in their own imaginative worlds, they are also untouched by the deadening effect of experience: the knowledge that things simply “aren’t like that”. In a child – especially a child of picture book age – however much they might protest that some things “couldn’t happen”, there is a residual suspicion that, you know what, they just might. The barrier between the real and the imaginary isn’t as clear, or as strong, as it is in grown-ups and so the potential to get lost in a created world is much greater.

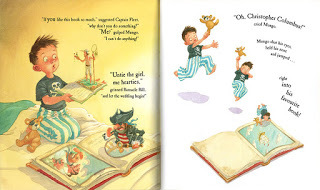

It’s the haziness of that barrier that was the subject of my Mungo books. In each one, Mungo is reading a different kind of story and then something goes wrong. In Mungo and the Picture Book Pirates, for instance, he reads his favourite book so many times that the hero becomes exhausted from having to repeat his acts of derring-do so often and goes on holiday. Without the hero to stop them, the book's villains start to take over the story, so Mungo has to jump into the book to save the day - and the book.

Mungo saves the day

Mungo saves the day

But just because anything can happen in a picture book – anything a writer and illustrator can imagine, anyway – doesn’t mean that anything should. I think totalfantasy – fantasy that is completely unanchored in the details of lived experience – doesn’t work because it’s arbitrary. There are no restrictions and it’s restrictions that create good art. For fantasy to captivate the reader – especially if that reader is a young child – it needs to rub up against the solid fact of the real world in some way. It’s that friction - between our world and the fantastical one - that strikes the spark of a really enjoyable story.

A writer has two ways of using fantasy. She can either set her story wholly, or mostly, in a made-up environment – what I am calling The World of the Weird – or by she can introduce fantasy elements into familiar settings – what I am calling The Weird in the World.

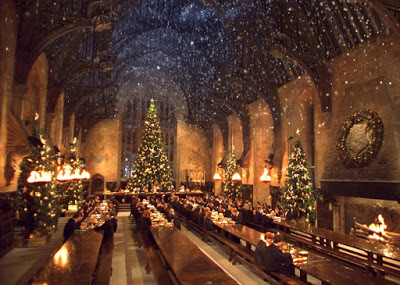

In general, The World of the Weird stories appeal more to children who are old enough clearly to delineate between the real and the fantastic, and who are therefore able to enjoy the detail of the imagination with which the stories are told. Just think of the geekish glee with which fans of Harry Potter seize upon – and argue about – the minutiae of JK Rowling’s wizarding universe. Part of the pleasure of her brilliant books comes from finding in them a place that has been so completely imagined by the writer that you can imaginatively occupy and explore it yourself.

Hogwarts – a fantasy world full of imaginative detail

Hogwarts – a fantasy world full of imaginative detail

(It’s easier to do that sort of thing in books – where the writer has more space and time to lay out every detail of her world – than in, say, movies. The reason why George Lucas’s Star Wars saga began in the middle – with “Episode Four” of a supposed six-part story – was so that he wouldn’t have to explain how everything in his “galaxy far, far away” worked. Because movie-goers were coming in halfway through the story, Lucas reasoned, they would just have to pick things up as they went along.)

Tolkien and Lewis

Tolkien and Lewis

The level of detail in the imagined world is important here. Rowling spent years constructing hers, so did JRR Tolkien, whose Middle Earth exerts a similar fascination for its fans. Compare that with Tolkien’s friend CS Lewis. He jerry-built his Narnia books from pre-fabricated fantasy elements – Greek mythology, King Arthur, Christian allegory and the 1,001 Nights. I don’t think is a coincidence that the Narnia books inspire far less immersive geekiness than the Middle Earth books – or that they are aimed at younger readers.

Because younger readers aren’t interested in fantasy worlds in the same way as more mature readers are: for one thing, they’re not old enough to enjoy the imaginative detail. They want a story they can navigate without having to learn the rules of an alien world first.

“It went thataway!” The Kiss That Missed

“It went thataway!” The Kiss That Missed

Of course there are plenty of picture books that are set in imaginary places, but the picture book writer isn’t inventing an internally consistent other world that the reader can explore. Instead, she is more often than not portraying our world dressed up in funny clothes. Take David Melling’s wonderful The Kiss That Missed. It may look like it’s set in a world of castles, knights and dragons, but we don’t need to know about any interesting or innovative “rules” this world might have because they’re not important. This is a sweet, domestic tale, a clear metaphor for something that happens in our world, somewhere or other, every bedtime. A busy father (in the story, the king) has been too preoccupied properly to say goodnight to his child (the prince). His loving feelings (the runaway kiss) are true and powerful, but he has been too busy with other things to express them properly.

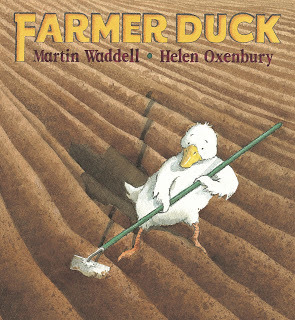

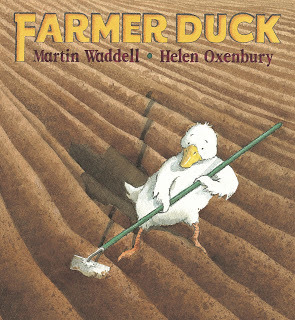

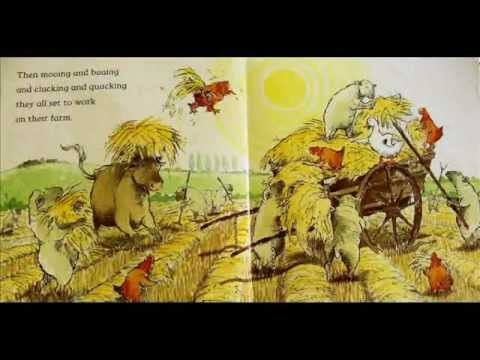

The most common kind of World of the Weird picture book is the anthropomorphic animal story. From Aesop to Mr Toad and on, animal stories aren’t about animals or their world; they’re about us. One of my favourites, is Martin Waddell’s Farmer Duck, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury. Not only is it about things that young children will instantly recognise – unfairness, and the need to put things right – it’s even a version of another animal story that is, itself, really about our world: George Orwell’s Animal Farm. (Check out the last illustration, where the once put-upon duck is now in charge of the farm. You’ll notice an imperious pointing of the wing: like the pigs in Orwell’s story, the duck is now the oppressor.)

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

For all these reasons, I think fantasy works better in picture books if the stories are of the Weird in the World variety. Like their World of the Weird counterparts, they can involve animals. The most famous is probably Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came To Tea. But there’s a difference. These are not always metaphorical stories. Kerr herself has been very clear that the tiger – who consumes all the food and drink in a suburban home before disappearing, never to return – is not in any way a representation of Hitler, whose rise to power forced her to emigrate from her native Germany. The pleasure of her tale comes not from “decoding” it, from working out what she "really" means, but simply from its oddness.

The Tiger Who Wasn’t Hitler

The Tiger Who Wasn’t Hitler

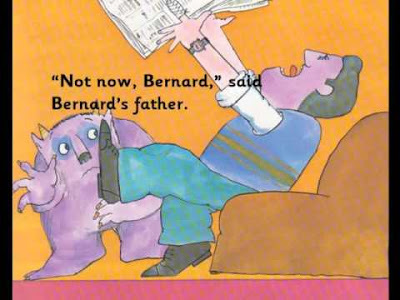

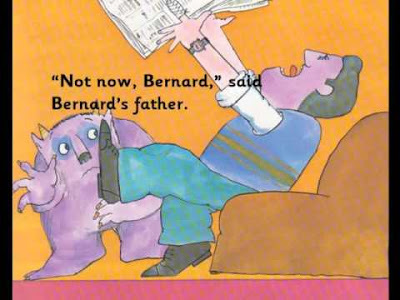

Weird in the World stories often use the juxtaposition of real and fantastic for comic ends. Think of the elephant you can’t take on the bus in Patricia Cleveland-Peck’s book, illustrated by David Tazzyman. Or Not Now Bernard, by David McKee – a funny, but very dark depiction of parental preoccupation in which a monster eats a neglected child and is unthinkingly pushed into taking his place by a mother and father who are too interested in other things to notice.

Monsters, children – what’s the difference when you're trying to read the paper?

Monsters, children – what’s the difference when you're trying to read the paper?

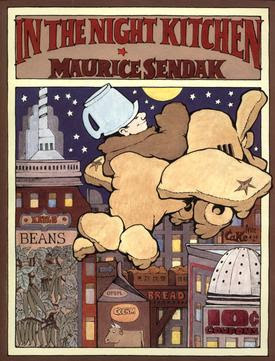

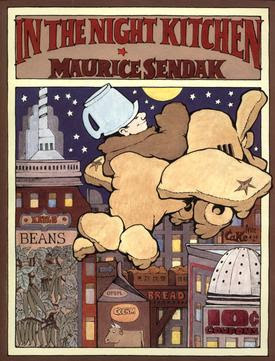

Sometimes, picture book characters will pop in and out of fantasy worlds. The most famous is Max, whose temper tantrum carries him “through night and day, and in and out of weeks, and almost over a year, to where the wild things are”. But it’s the domestic details that bookend the story – the mischief of one kind and another at the beginning, the supper that’s still hot at the end – that makes his journey interesting. By contrast, the arbitrary dream logic of Maurice Sendak’s subsequent In The Night Kitchen renders that story random and inconsequential.

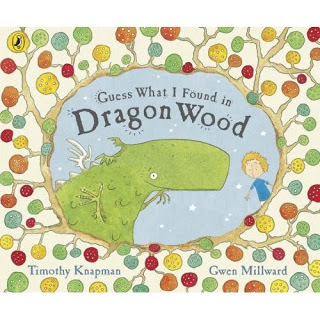

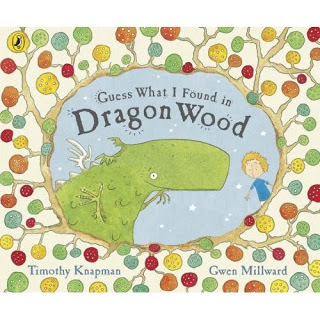

Ten years ago, I wrote a book that was an attempt to mix a Weird in the World story with a World of the Weird one. Guess What I Found in Dragon Wood was inspired by a picture the illustrator, Gwen Millward, had made. It was a beautiful study of a boy and a dragon, playing together in the boy’s room. The two were obviously friends but Gwen couldn’t find a story there.

My suggestion was that, instead of the dragon being in the boy’s world, the boy should be in the dragon’s – at least to start with. So the book is told from the dragon’s point of view, and is all about his new discovery: a strange and magical creature called a “Benjamin”. We’re in a weird world all right – the dragons eat worms and stinky fish, and go to school to learn how to sit on a volcano – but there’s something weirder still in that world: one of us.

Seeing the Benjamin through the dragon’s eyes, I hoped my young readers would understand (even if it was only without realising) how odd and fantastical – how weird - our world is. And I hoped the story would help them enjoy the closely imagined fantasy that we call “real life”.

No, I mean naturalism, realism, whatever you want to call it: the attempt to create in art a faithful replica of the surface detail of real life - the sort of thing “kitchen sink” novelists and playwrights such as Alan Sillitoe, David Storey and John Osborne were doing in the 1950s.

John Osborne’s “kitchen sink” drama “Look Back In Anger” – though perhaps it’s better described as an “ironing board” drama

John Osborne’s “kitchen sink” drama “Look Back In Anger” – though perhaps it’s better described as an “ironing board” dramaI admire the skill, of course - and the compassionate and campaigning impulses behind it - but a bit of me is always thinking: why should I go out to see a play about alcoholism, despair, poverty and unemployment? I can get all that at home.

(I feel much the same about 3D movies. Why should I pay extra for a 3D movie? I get 3D all the time! Life is in 3D! It’s 2D that’s the novelty! But I digress...)

As a child, I was always drawn to the strange, the funny, the macabre – in short, the weird. I loved Doctor Who and Star Wars and Monty Python: aliens, robots and Terry Jones showing his bottom. So when I started writing for children, of course, it was the fantastical, the odd, the bizarre, that I wanted to write about.

The anxiety of influence: Terry Jones’s bottom