Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 38

June 24, 2018

Writing an accidental Picture Book Series by Chitra Soundar

I didn’t start out to write a series of picture books. But now I realise I’ve one successful series and another one edging in that direction.

I’ve always been a fan of series fiction – whether as chapter books or as picture books. When I fall in love with a character, be it Elmer or Lulu, I love to read other stories about them. I want to see them do different things.

I’ve always been a fan of series fiction – whether as chapter books or as picture books. When I fall in love with a character, be it Elmer or Lulu, I love to read other stories about them. I want to see them do different things. But as a writer, I always knew that a series is something you can plan for, but actually getting to publish one, is not up to me. So even though I never intended to write one, I stumbled on to a series.

The Farmer Falgu series originated in India and is now available worldwide in many languages. And this is how it started.

The Farmer Falgu series originated in India and is now available worldwide in many languages. And this is how it started.I wrote a story about silence and the joyfulness of noise set in an Indian farmer’s life. I wanted the story to have musical elements and I wanted my farmer full of positivity. I didn’t have an idea that I was creating a friend for myself.

After I submitted the story and it was accepted, I happened to realise another one of my story ideas will fit this character. So I asked the publisher if they would accept another story for the same character. Now this was even before an illustrator was chosen for the first. While the first one focussed on sound, the second one was all about food.

It was a gamble but the editor said yes and to my delight both Farmer Falgu Goes on a Trip and Farmer Falgu Goes to the Market is available in many different languages – from French to German to Japanese and American English.

It was a gamble but the editor said yes and to my delight both Farmer Falgu Goes on a Trip and Farmer Falgu Goes to the Market is available in many different languages – from French to German to Japanese and American English. The success of the first two books both in India and abroad, triggered a commission of two more stories. And a series was born.

The success of the first two books both in India and abroad, triggered a commission of two more stories. And a series was born.But the thing about series is, especially one that has become popular is, there’s more at stake. I wrote so many different stories for the same character, trying to find the third and the fourth I was commissioned.

But the 3rd and 4th book would not have been possible if I wasn’t doing extensive research on both Farmer Falgu and India in particular looking for stories.

Farmer Falgu was completely a product of imagination and a series of accidental events. So after I created the character, I did a lot of research on his back story. I had chosen a name that happened to have historical significance. And that was a happy accident. The illustrator had set him in Rajasthan and that was another happy accident for me (although she would have made a conscious choice).

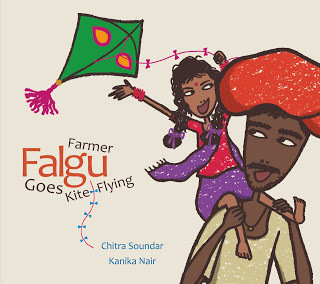

So I researched the background of the state, created resources and activities for kids. This led to my researching the kite festival, which then turned into an idea for Book 4.

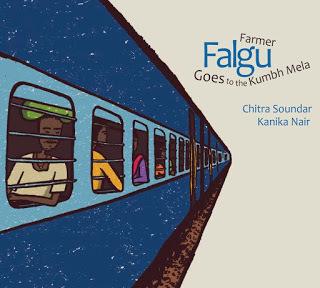

Researching India and having a discussion with the publisher gave me another idea – the Kumbh Mela – the biggest festival on earth. I loved that it had all the elements I love in a story and in life – rivers, trains, food, elephants and a Farmer Falgu who couldn’t catch a break. Or did he?

So as I wrote Book 3 and 4, I learned some key things about writing an unplanned, accidental series.

a) The character now has a life of his own. And therefore the story has to fit this life. As the illustrator Kanika Nair made him a Rajasthani farmer, the new stories needed to fit his new life in Rajasthan and what happened there.

b) The throughline – the first two stories had unconsciously created a personality, a theme and an ethos for my character. He was a glass-half-full guy and therefore any new story needed to fit his ethos.

c) The Economics: Three or four books of the same character, the same author-illustrator duo is an investment for a small independent publisher from India. They had to be really sure that the 3rdbook and the 4th book would work. So there was a lot more scrutiny, review and discussion before these stories were even written.

d) The expectations: These stories showcased India in a small way and with the first two books having sold in many foreign territories, a need to show some wonderful events or places in India within Farmer Falgu’s life was tempting. We zoomed back from his farm out into a bigger world for Book 3 and 4.

e) Series guidelines: These weren’t written down – but there was a sense of how long the book would be, the pattern, the setting and the title. The first two titles had “Farmer Falgu Goes…”. So I had to make him go somewhere in each story.

As a writer, suddenly I had to work within a framework. Sometimes it felt as if the story didn’t come first, the series guidelines did. But then pushing the story to the forefront and making the character centre-stage helped me plot Book 3 and Book 4.

Available in the UK soon through Red Robin Books

Available in the UK soon through Red Robin BooksAs much as there is a pre-defined framework when you work on a series, there are benefits too. If parents and teachers like one of the books in the series, they’re more likely to buy the others. The characters turn into friends. I have Farmer Falgu talking to me at odd times when he sees something through my eyes. But also as a writer I start seeing the world through his eyes.

Available in the UK soon through Red Robin Books

Available in the UK soon through Red Robin BooksAnd now I’m standing on the edge of another series. Fingers crossed!

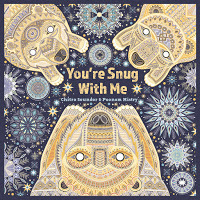

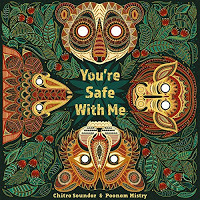

You’re Safe With Me (illustrated by Poonam Mistry) was met with so much love even before it was published that the publisher, Lantana Publishing, commissioned a companion story, You’re Snug with Me. Although it is not the same characters in the second book, a pattern has emerged. Whether there’s a third book, only time will tell.

You’re Safe With Me (illustrated by Poonam Mistry) was met with so much love even before it was published that the publisher, Lantana Publishing, commissioned a companion story, You’re Snug with Me. Although it is not the same characters in the second book, a pattern has emerged. Whether there’s a third book, only time will tell.  Chitra Soundar is an Indian-born British writer of picture books and junior fiction. When she's not writing stories, she can be seen telling them to both children and grown-ups across libraries, festivals and schools in the UK and worldwide. Find out more at www.chitrasoundar.com or follow her on Twitter at @csoundar.

Chitra Soundar is an Indian-born British writer of picture books and junior fiction. When she's not writing stories, she can be seen telling them to both children and grown-ups across libraries, festivals and schools in the UK and worldwide. Find out more at www.chitrasoundar.com or follow her on Twitter at @csoundar.

Published on June 24, 2018 23:00

June 17, 2018

Ssshhh! When a Picture Book writer embarks on an affair with a Novel. And what have other authors brought from picture book writing to novel writing, and from novel writing to picture book writing? by Juliet Clare Bell

You know when you first start writing, and how you keep your writing habit secret for a while, or only speak about it apologetically? And then once you’ve been doing it a while and feel more confident in your area, you might talk about with more certainty, and maybe you get a book published, and you feel more legitimate again…?

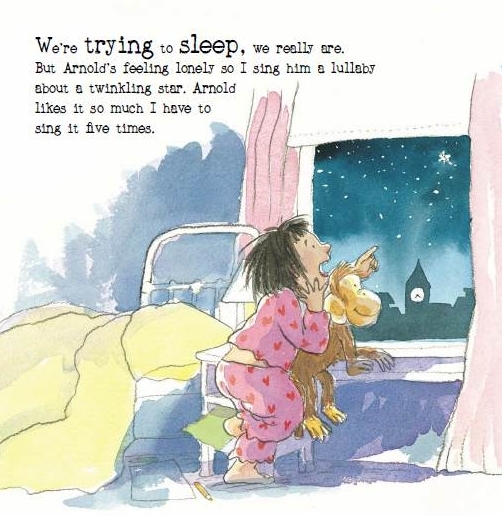

The joy of having your first book published and feeling like a 'real writer'. A young (non-panicking) Annika jumping for joy (on my behalf) at my first book, Don't Panic, Annika! (illustrated by Jennifer E Morris, 2011)

But what about when you feel legitimate in one area of writing but start doing something in a brand new one? Do you have to start again as a complete newbie? What strategies from one can you bring to the other? And can you keep some of that confidence, or do you have to go back to those terrible apologetic conversations with people about what you’re currently writing?

Well in the spirit of allowing yourself to be vulnerable and to take risks in order to be and know who you are (which is central to the story I’m writing), I’m ’fessing up, even though I’m at the early apologetic stage:

I AM WRITING A NOVEL.

I had to delete and change that from ‘I AM TRYING TO WRITE A NOVEL’, the language I’ve absolutely slipped back into now I’m writing in a completely new field. But I am writing one. It may never end up getting published, but I AM writing it, rather than ‘trying to write it’ and I am trying to use what I already know from writing picture books.

I love learning from other people, and so I asked a few children's writer-y friends who have done/are doing both children's novels and picture books, for their thoughts…

First, I wanted to know how easy is it to work on both at the same time?

I asked this because I have so far found it extremely difficult to think about both. It turns out, the writers I asked who liked writing both genres all found the switching easy. Here’s Sophia Bennett, successful, award-winning author of novels including Unveiling Venus, Threads and Love Song …. and who has at least one new picture book out in 2019 (she can't say too much about anything at the moment, but having read a draft of one of them, I can tell you that she is an exquisite picture book writer).

Sophia's most recent novel, Unveiling Venus (Stripes Publishing, 2018)

“Finding the time is extremely difficult. But when I do, I actually love skipping from one to the other, because each one uses different brain space and makes coming back to what I was doing before feel fresh, and a pleasure.”

(c) Jacob Sager Weinstein (2017)

Jacob Sager Weinstein is the author of The City of Secret Rivers (an absolute favourite with one of my children), for which he has been shortlisted for the Branford Boase award for most promising new author, and the upcoming picture book Lyric McKerrigan, Secret Librarian (illustrated by Vera Brosgol).

(c) Jacob Sager Weinstein and Vera Brosgol (2018)

He agrees with Sophia:

“In some ways, it’s easier than just working on one kind of book — if I’m not in the right frame of mind for one, I’m often in the right frame of mind for the other. God knows I still procrastinate, but at least I have the option of procrastinating productively”.

Productive procrastination? I look forward to that…

Wendy Meddour, author of many books, including the Wendy Quill series

(c) Wendy Meddour and Mina May (2013)

(c) Wendy Meddour and Duncan Beedie. Stefano the Squid, Hero of the Deep will be out with Little Tiger Press

and also finds the shift easy, and does it based on timing:

“I generally treat myself to writing picture books on weekends …and work on novels at night (after I’ve finished work and the kids are in bed)”.

I’m feeling more hopeful now. I had naively thought when I started that I could work on my novel from 6-7am each morning, and then do everything else (picture books, author visits, admin etc) during the rest of the time available and that I could make the switch easily. But unlike the authors, above, I found it almost impossible to think about picture books at all whilst I was in the really early stages of doing the novel. As a picture book writer, I think loads about structure as it’s so critical to a picture book. I knew that I know how to write; I knew I know how to structure a picture book, but what I didn’t know was whether I could structure a novel. And so I made myself work on the structure and get that sorted (including having a description of each scene) before I actually started writing out the story at all. There was no way I was going to embark on a full-length novel if I wasn’t sure I could complete it in a way that made sense (I had started an adult novel about 17 years ago but never got beyond Chapter 3 as I just didn’t have a structure for the whole thing, even though I had hundreds of pages of rough notes about the characters). This was before I’d written picture books, and now I’m used to plotting and I’ve seen how a longer story can crumble so quickly without decent foundations. And, taking to heart the sentiment of Seamus Heaney's wonderful poem (with apologies to him for the spurious connection of his poem to the subject of children's novel writing, as opposed to love -but it's a great poem, and reading, of) Scaffolding I would never embark on such an enormous story without feeling I’d got my scaffolding in order:

Seamus Heaney reading his poem, ScaffoldingAs Sophia says:

“ I do find each novel daunting… knowing I’m going to risk writing for a whole year about something readers may not connect with when it’s done. You never know. That aspect of novel writing seems mad. At least with a picture book it’s quicker!”

Exactly. That’s why it’s taken so long for me even to consider trying to write a novel again. And at least if you have the scaffolding there, you feel more confident that what will stand at the end of it will be solid. Ish. And now, having finished the structure for the first draft, it feels like I don’t have to hold it all in my head anymore; I can just write what I’m told to (by me), looking at each scene description and following its structure. As a picture book writer, this feels much more familiar –and safe- and I am now going to put my Wendy Meddour hat on and write the novel at certain specified times of the week, and picture books at others, and I have just in this last week got back into thinking about picture books again. (Unless I am in need of a bit of Jacob's productive procrastination (thank you, Jacob), in which case I might be really frivolous, and swap...).

So how do the picture-book-and-children's novel writers I spoke with use strategies for plotting and structuring one type of book for the other?

Sophia:

“I am a planner. With all my books - adult, young adult and picture books - I plan and research a lot before I start, and more as I go. Even so, the story moves off in directions I wasn’t quite expecting. With all of them, my core subject is something I’m passionate about, so I put a lot of myself into them.”

Sophia Bennett

And on using novel writing strategies for a picture book?

“I think of it in various acts! Even though I only have a few hundred words to play with, I have my opening section, the building action, the climax and the resolution. I try and use interesting dialogue. I research a lot, think hard about the characters and have it plotted out in my head before I start, but then let the poetry of the words lead me on as I write.

As I’m new to picture books I don’t really have strategies for it - just an endless learning process. Hopefully I’ll have something to bring from it to the other books eventually. It might be to do with how much you can leave unsaid and still get the message across. I keep finding that the more words I cut, the better it gets.”

Candy, your thoughts?

Candy Gourlay, award-winning author of Tall Story and Shine

(c) Candy Gourlay, 2010

whose first picture book, Is It a Mermaid? (illustrated by Francesca Chessa, Otter Barry Books, 2018) is just out

(c) Candy Gourlay and Francesca Chessa (2018)

and whose new novel, Bone Talk (David Fickling Books, 2018) will be out later this year, talked about writing picture books as an author of children's novels:

“because novel writing has a lot to do with structure, I find myself applying longer format structural rules to my picture book writing. Like putting a plot pivot at the very middle of a story. And thinking hard about context and set up to create a satisfying pay off. I do this a million times over the course of writing a novel … so I can chart a reader's emotional arc as they read the novel. But in picture books, you only get one shot at satisfying your reader”.

(c) Candy Gourlay (2018)

And Jacob?

“Plot is probably more important in a novel than in a picture book. A picture book can be purely about language or character or a single emotion; a novel needs a well-structured story to drive it forward. For better or for worse, my picture books are very plot-driven. I’m in awe of PBs that don’t have a traditional plot, and I have no idea how to write one. “When you’re writing a picture book, you have to think carefully about every single word. With a novel, it’s easier to let flabby language slide. My last major rewrite of a novel is always to read it through and cut out as many words as I possibly can. I’m only realising it now, as I answer this question, but that definitely involves looking at my novel with the eyes of a picture book writer.”

Wendy, on the other hand, is not a natural planner:

“I’m not a good planner. I wish I was. But I’m not. I just love to write. This is true for both my picture books and novels. It’s the idea that is crucial. I never know exactly where I’m going to find myself. I just trust that some part of my brain does.

With both novels and picture books, an idea starts fizzing, one that I can’t ignore, so I write it out furiously. Then edit. And edit. And edit. Ideas often emerge when I’m trying to process an experience in real life: say, a worry about someone or something, or a topic I feel strongly about at the time: child refugees, migration, Islamophobia, childhood anxiety, library closures, sexism. Whatever. Writing it out (in fictional form) allows me to feel like I’m doing something productive. As to strategies, having always been an avid reader, I’m very familiar with both genres, so although it feels like a ‘natural process’ when I’m writing, and I’m not a planner as such, I think I am probably quite technical in my writing without being particularly conscious of it. I’ve read so many novels and picture books over the years that I know how to structure them, hook the reader and vary the pace. I also teach creative writing at Exeter University, so am used to giving lectures about ‘character’, ‘style’ and ‘form’”.

Malachy Doyle, whose picture book Cinderfella (illustrated by Matt Hunt) is coming out later this year with Walker,

(c) Malachy Doyle and Matt Hunt (2018)

and who has written many picture books, including one of my favourite picture books

When a Zeeder Met a Xyder ( (c) Malachy Doyle and Joel Stewart, 2006)

When a Zeeder Met a Xyder ( (c) Malachy Doyle and Joel Stewart, 2006)

is not a planner either:

“I find that, when I write longer, it can be very time-consuming because I craft every sentence, sweat over every word, as I would when writing picture book. I haven't learnt to run loose. I like to work in miniature - poetry, picture book, Barrington Stoke length books for older readers. Somehow it just suits me. I never plan. Which may work better for picture book than full-length novel, but it's just how I work. Find a character, put them in an interesting situation and run with it. Surprise yourself!”

And what do you find are the advantages and disadvantages of staying with a story so long when you’re writing a novel as opposed to a picture book? Jacob:

“By the time a novel goes to print, I must have read its 60,000 words two dozen times. That’s like reading one very repetitive 1,440,000 word novel. I’m sick and tired of it, and I struggle to remember that readers will be coming to it fresh.

On the other hand, it’s an absolute joy to plant a little clue on page one of a book, and pay it off in the last chapter, or even another book. Plus, there’s room for characters to grow and change and surprise not just the reader but me as well. Picture book characters still need to go on journeys, but they’re much shorter (and, usually, much less nuanced) ones".

(c) Jacob Sager Weinstein (2018) Hyacinth and the Stone Thief -second in the trilogy (out in the US already)

Wendy:

“[with children's novels] I can start behaving like my characters. My children used to ask me to stop being ‘so Wendy Quillish’ when I was mid-series with her. (She’s always taking things too literally and getting into trouble). The dangers of method writing! [But the advantage?] When the writing is flowing, and the words are doing what they should, it feels amazing.

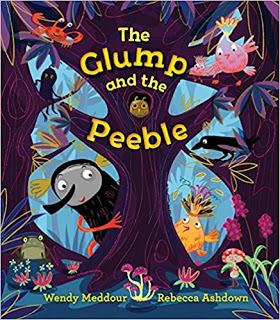

Also, I don’t think I do move on quickly [from picture books]. All the picture book characters I write stay with me. The process is very intense. Possibly more intense than novels. Rapunzel. The Glump. The Peeble. Stefano the Squid. All so very real in my head. Especially when an illustrator has helped bring them to life”.

(c) Wendy Meddour and Rebecca Ashdown (2016)

Sophia?

“I get to know my characters so well [in a novel]. Also themes emerge as I write that I didn’t know would be important when I started, but which obviously mean a lot to me and bubble up from my subconscious as I go. Often, what the novel ends up being ‘about’ is not at all what I had in mind when I started. Threads is definitely about the power of friendship, for example, but I meant to write about the unknowability of genius and the other girls were just in it to do functional things in the plot. Then their personalities took over and the pleasure came from how they interacted.”

And which do you prefer, or find easier to write?Jacob:

“Picturebooks originally came more naturally to me. Before I turned to kids books, I had written short stories and screenplays for [adults]. Like a short story, a picture book is an intense narrative burst. Like a screenplay, a picture book text is just one part of a collaboration with a visual artist. So the skills I had spent years developing were much more applicable to PBs. Now that I’ve written two MG novels (and a few drafts of a third), I think I’ve finally got the hang of it, and I don’t think either form is easier than the other. I don’t have a preference, which is why I write both! I consider myself really lucky that I can work in both forms”.

A 'really lucky' Jacob Sager Weinstein

Wendy:

“I enjoy all forms of writing. They exercise different parts of my brain and allow me to explore ideas and play with thoughts in different ways… Adapting my style or tone of voice to suit the intended audience is all part of the fun. Rhyming picture books come very easily, as they have a certain silliness and structure, but if I can hear a character’s voice in my mind, then I’m off”.

Sophia:

“I find both difficult. The only books I have ever found easy were the very first one I wrote - an (unpublished) adult detective story, and book two of the Threads trilogy, when the characters just seemed to do whatever I needed them to without question. I think I enjoy writing picture books more though. Because every word counts, I can take pleasure in each one. I also love imagining what an illustrator will do. I want to write one for 5-7 year olds about Abstract Impressionism, so I don’t exactly set myself the easiest tasks, but I’ll be so pleased if I manage to make it work the way it does in my head”.

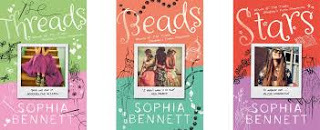

Beads, the only one of Sophia's published books that she found easy to write

And Malachy?

“Picture books are my first love. I find that when I go teenage - Georgie, Who is Jesse Flood? for example - I go all angsty. I find that I become the age I was then, in a strange way. I've decided that I much prefer to inhabit the young happy enquiring Malachy than the angst-ridden teen Malachy, so that's where I concentrate my efforts these days.

I also love working with illustrators, and my books becoming more than the sum of their parts - when an illustrator totally gets where I'm coming from in my story, but then adds the depth and wonder that they can bring as a gifted visual artist, true magic, a form of alchemy, can happen. My new picture book, Molly and the Stormy Sea, out this week from Graffeg, illustrated by the wonderful Andrew Whitson, is a perfect example of this”.

trailer for Molly and the Stormy Sea (c) Malachy Doyle and Andrew Whitson (2018)

I love picture books. I even found myself feeling guilty for choosing to write a (YA) novel when I’ve pledged my allegiance to picture books. But now I’m writing ‘up’ the novel (that is already planned and plotted), I’m back to continue with both. It may take many, many drafts (probably fewer than the 187 drafts Malachy had for his first picture book, and I hope fewer than the seventeen drafts Sophia did for her first published novel, Threads, before she was ready to send it off and then a further seventeen before it was finished and published, though very possibly not) but I’m ready to go with it. To accept that I’m going to learn a whole lot over the next couple of years about something new, that I’ll make a ton of mistakes along the way (like I encourage young people in schools to do, all the time), that I’ll probably feel the terror that I did when showing my picture book manuscripts back when I started, before I grew a very tough (picture book) skin. Will that toughness extend to showing people my novel? I suspect not, but I also suspect it won’t be quite as awful and raw as it was. And actually allowing yourself to be vulnerable like that is a pretty powerful thing:

Brene Brown's Ted Talk on vulnerability

I will do Jacob’s ‘picture book author’ edit on my novel where I try and cut lots of words that aren’t necessary. I am hopeful that writing this novel will also help me write early versions of picture books more quickly (if I wrote anything like as slowly with the novel, it would be many, many years before I got my first novel draft out). And that I’ll learn new things about structuring which will strengthen future picture books, too. Whatever the outcome, I will finish a first draft, and then a second, and subsequent ones, and I will learn loads –about story writing and myself. I hope that writing as a teenager won't make me get too angsty. Like Malachy, I was a much happier picture-book aged child than I was a teenager (so thanks for the warning, Malachy). And if it doesn’t end up as a published novel, well that’s not the end of the world. I will have gained much more than if I hadn’t tried (I've already read more novels in the past year than I probably had in the previous twenty). And who knows, it might even one day find itself a home…

Many thanks to Sophia Bennett, Malachy Doyle, Candy Gourlay, Wendy Meddour and Jacob Sager Weinstein for sharing their helpful thoughts on writing in both genres. If you've tried writing picture books and novels, how has the writing and planning of one type affected the writing and planning of the other? I'd love to hear from you with any thoughts, below. Juliet Clare Bell is the author of five picture books and three early readers. She would love to add the novel she is currently writing to this, but fully intends to write many more picture books, regardless.

www.julietclarebell.com

The joy of having your first book published and feeling like a 'real writer'. A young (non-panicking) Annika jumping for joy (on my behalf) at my first book, Don't Panic, Annika! (illustrated by Jennifer E Morris, 2011)

But what about when you feel legitimate in one area of writing but start doing something in a brand new one? Do you have to start again as a complete newbie? What strategies from one can you bring to the other? And can you keep some of that confidence, or do you have to go back to those terrible apologetic conversations with people about what you’re currently writing?

Well in the spirit of allowing yourself to be vulnerable and to take risks in order to be and know who you are (which is central to the story I’m writing), I’m ’fessing up, even though I’m at the early apologetic stage:

I AM WRITING A NOVEL.

I had to delete and change that from ‘I AM TRYING TO WRITE A NOVEL’, the language I’ve absolutely slipped back into now I’m writing in a completely new field. But I am writing one. It may never end up getting published, but I AM writing it, rather than ‘trying to write it’ and I am trying to use what I already know from writing picture books.

I love learning from other people, and so I asked a few children's writer-y friends who have done/are doing both children's novels and picture books, for their thoughts…

First, I wanted to know how easy is it to work on both at the same time?

I asked this because I have so far found it extremely difficult to think about both. It turns out, the writers I asked who liked writing both genres all found the switching easy. Here’s Sophia Bennett, successful, award-winning author of novels including Unveiling Venus, Threads and Love Song …. and who has at least one new picture book out in 2019 (she can't say too much about anything at the moment, but having read a draft of one of them, I can tell you that she is an exquisite picture book writer).

Sophia's most recent novel, Unveiling Venus (Stripes Publishing, 2018)

“Finding the time is extremely difficult. But when I do, I actually love skipping from one to the other, because each one uses different brain space and makes coming back to what I was doing before feel fresh, and a pleasure.”

(c) Jacob Sager Weinstein (2017)

Jacob Sager Weinstein is the author of The City of Secret Rivers (an absolute favourite with one of my children), for which he has been shortlisted for the Branford Boase award for most promising new author, and the upcoming picture book Lyric McKerrigan, Secret Librarian (illustrated by Vera Brosgol).

(c) Jacob Sager Weinstein and Vera Brosgol (2018)

He agrees with Sophia:

“In some ways, it’s easier than just working on one kind of book — if I’m not in the right frame of mind for one, I’m often in the right frame of mind for the other. God knows I still procrastinate, but at least I have the option of procrastinating productively”.

Productive procrastination? I look forward to that…

Wendy Meddour, author of many books, including the Wendy Quill series

(c) Wendy Meddour and Mina May (2013)

(c) Wendy Meddour and Duncan Beedie. Stefano the Squid, Hero of the Deep will be out with Little Tiger Press

and also finds the shift easy, and does it based on timing:

“I generally treat myself to writing picture books on weekends …and work on novels at night (after I’ve finished work and the kids are in bed)”.

I’m feeling more hopeful now. I had naively thought when I started that I could work on my novel from 6-7am each morning, and then do everything else (picture books, author visits, admin etc) during the rest of the time available and that I could make the switch easily. But unlike the authors, above, I found it almost impossible to think about picture books at all whilst I was in the really early stages of doing the novel. As a picture book writer, I think loads about structure as it’s so critical to a picture book. I knew that I know how to write; I knew I know how to structure a picture book, but what I didn’t know was whether I could structure a novel. And so I made myself work on the structure and get that sorted (including having a description of each scene) before I actually started writing out the story at all. There was no way I was going to embark on a full-length novel if I wasn’t sure I could complete it in a way that made sense (I had started an adult novel about 17 years ago but never got beyond Chapter 3 as I just didn’t have a structure for the whole thing, even though I had hundreds of pages of rough notes about the characters). This was before I’d written picture books, and now I’m used to plotting and I’ve seen how a longer story can crumble so quickly without decent foundations. And, taking to heart the sentiment of Seamus Heaney's wonderful poem (with apologies to him for the spurious connection of his poem to the subject of children's novel writing, as opposed to love -but it's a great poem, and reading, of) Scaffolding I would never embark on such an enormous story without feeling I’d got my scaffolding in order:

Seamus Heaney reading his poem, ScaffoldingAs Sophia says:

“ I do find each novel daunting… knowing I’m going to risk writing for a whole year about something readers may not connect with when it’s done. You never know. That aspect of novel writing seems mad. At least with a picture book it’s quicker!”

Exactly. That’s why it’s taken so long for me even to consider trying to write a novel again. And at least if you have the scaffolding there, you feel more confident that what will stand at the end of it will be solid. Ish. And now, having finished the structure for the first draft, it feels like I don’t have to hold it all in my head anymore; I can just write what I’m told to (by me), looking at each scene description and following its structure. As a picture book writer, this feels much more familiar –and safe- and I am now going to put my Wendy Meddour hat on and write the novel at certain specified times of the week, and picture books at others, and I have just in this last week got back into thinking about picture books again. (Unless I am in need of a bit of Jacob's productive procrastination (thank you, Jacob), in which case I might be really frivolous, and swap...).

So how do the picture-book-and-children's novel writers I spoke with use strategies for plotting and structuring one type of book for the other?

Sophia:

“I am a planner. With all my books - adult, young adult and picture books - I plan and research a lot before I start, and more as I go. Even so, the story moves off in directions I wasn’t quite expecting. With all of them, my core subject is something I’m passionate about, so I put a lot of myself into them.”

Sophia Bennett

And on using novel writing strategies for a picture book?

“I think of it in various acts! Even though I only have a few hundred words to play with, I have my opening section, the building action, the climax and the resolution. I try and use interesting dialogue. I research a lot, think hard about the characters and have it plotted out in my head before I start, but then let the poetry of the words lead me on as I write.

As I’m new to picture books I don’t really have strategies for it - just an endless learning process. Hopefully I’ll have something to bring from it to the other books eventually. It might be to do with how much you can leave unsaid and still get the message across. I keep finding that the more words I cut, the better it gets.”

Candy, your thoughts?

Candy Gourlay, award-winning author of Tall Story and Shine

(c) Candy Gourlay, 2010

whose first picture book, Is It a Mermaid? (illustrated by Francesca Chessa, Otter Barry Books, 2018) is just out

(c) Candy Gourlay and Francesca Chessa (2018)

and whose new novel, Bone Talk (David Fickling Books, 2018) will be out later this year, talked about writing picture books as an author of children's novels:

“because novel writing has a lot to do with structure, I find myself applying longer format structural rules to my picture book writing. Like putting a plot pivot at the very middle of a story. And thinking hard about context and set up to create a satisfying pay off. I do this a million times over the course of writing a novel … so I can chart a reader's emotional arc as they read the novel. But in picture books, you only get one shot at satisfying your reader”.

(c) Candy Gourlay (2018)

And Jacob?

“Plot is probably more important in a novel than in a picture book. A picture book can be purely about language or character or a single emotion; a novel needs a well-structured story to drive it forward. For better or for worse, my picture books are very plot-driven. I’m in awe of PBs that don’t have a traditional plot, and I have no idea how to write one. “When you’re writing a picture book, you have to think carefully about every single word. With a novel, it’s easier to let flabby language slide. My last major rewrite of a novel is always to read it through and cut out as many words as I possibly can. I’m only realising it now, as I answer this question, but that definitely involves looking at my novel with the eyes of a picture book writer.”

Wendy, on the other hand, is not a natural planner:

“I’m not a good planner. I wish I was. But I’m not. I just love to write. This is true for both my picture books and novels. It’s the idea that is crucial. I never know exactly where I’m going to find myself. I just trust that some part of my brain does.

With both novels and picture books, an idea starts fizzing, one that I can’t ignore, so I write it out furiously. Then edit. And edit. And edit. Ideas often emerge when I’m trying to process an experience in real life: say, a worry about someone or something, or a topic I feel strongly about at the time: child refugees, migration, Islamophobia, childhood anxiety, library closures, sexism. Whatever. Writing it out (in fictional form) allows me to feel like I’m doing something productive. As to strategies, having always been an avid reader, I’m very familiar with both genres, so although it feels like a ‘natural process’ when I’m writing, and I’m not a planner as such, I think I am probably quite technical in my writing without being particularly conscious of it. I’ve read so many novels and picture books over the years that I know how to structure them, hook the reader and vary the pace. I also teach creative writing at Exeter University, so am used to giving lectures about ‘character’, ‘style’ and ‘form’”.

Malachy Doyle, whose picture book Cinderfella (illustrated by Matt Hunt) is coming out later this year with Walker,

(c) Malachy Doyle and Matt Hunt (2018)

and who has written many picture books, including one of my favourite picture books

When a Zeeder Met a Xyder ( (c) Malachy Doyle and Joel Stewart, 2006)

When a Zeeder Met a Xyder ( (c) Malachy Doyle and Joel Stewart, 2006)is not a planner either:

“I find that, when I write longer, it can be very time-consuming because I craft every sentence, sweat over every word, as I would when writing picture book. I haven't learnt to run loose. I like to work in miniature - poetry, picture book, Barrington Stoke length books for older readers. Somehow it just suits me. I never plan. Which may work better for picture book than full-length novel, but it's just how I work. Find a character, put them in an interesting situation and run with it. Surprise yourself!”

And what do you find are the advantages and disadvantages of staying with a story so long when you’re writing a novel as opposed to a picture book? Jacob:

“By the time a novel goes to print, I must have read its 60,000 words two dozen times. That’s like reading one very repetitive 1,440,000 word novel. I’m sick and tired of it, and I struggle to remember that readers will be coming to it fresh.

On the other hand, it’s an absolute joy to plant a little clue on page one of a book, and pay it off in the last chapter, or even another book. Plus, there’s room for characters to grow and change and surprise not just the reader but me as well. Picture book characters still need to go on journeys, but they’re much shorter (and, usually, much less nuanced) ones".

(c) Jacob Sager Weinstein (2018) Hyacinth and the Stone Thief -second in the trilogy (out in the US already)

Wendy:

“[with children's novels] I can start behaving like my characters. My children used to ask me to stop being ‘so Wendy Quillish’ when I was mid-series with her. (She’s always taking things too literally and getting into trouble). The dangers of method writing! [But the advantage?] When the writing is flowing, and the words are doing what they should, it feels amazing.

Also, I don’t think I do move on quickly [from picture books]. All the picture book characters I write stay with me. The process is very intense. Possibly more intense than novels. Rapunzel. The Glump. The Peeble. Stefano the Squid. All so very real in my head. Especially when an illustrator has helped bring them to life”.

(c) Wendy Meddour and Rebecca Ashdown (2016)

Sophia?

“I get to know my characters so well [in a novel]. Also themes emerge as I write that I didn’t know would be important when I started, but which obviously mean a lot to me and bubble up from my subconscious as I go. Often, what the novel ends up being ‘about’ is not at all what I had in mind when I started. Threads is definitely about the power of friendship, for example, but I meant to write about the unknowability of genius and the other girls were just in it to do functional things in the plot. Then their personalities took over and the pleasure came from how they interacted.”

And which do you prefer, or find easier to write?Jacob:

“Picturebooks originally came more naturally to me. Before I turned to kids books, I had written short stories and screenplays for [adults]. Like a short story, a picture book is an intense narrative burst. Like a screenplay, a picture book text is just one part of a collaboration with a visual artist. So the skills I had spent years developing were much more applicable to PBs. Now that I’ve written two MG novels (and a few drafts of a third), I think I’ve finally got the hang of it, and I don’t think either form is easier than the other. I don’t have a preference, which is why I write both! I consider myself really lucky that I can work in both forms”.

A 'really lucky' Jacob Sager Weinstein

Wendy:

“I enjoy all forms of writing. They exercise different parts of my brain and allow me to explore ideas and play with thoughts in different ways… Adapting my style or tone of voice to suit the intended audience is all part of the fun. Rhyming picture books come very easily, as they have a certain silliness and structure, but if I can hear a character’s voice in my mind, then I’m off”.

Sophia:

“I find both difficult. The only books I have ever found easy were the very first one I wrote - an (unpublished) adult detective story, and book two of the Threads trilogy, when the characters just seemed to do whatever I needed them to without question. I think I enjoy writing picture books more though. Because every word counts, I can take pleasure in each one. I also love imagining what an illustrator will do. I want to write one for 5-7 year olds about Abstract Impressionism, so I don’t exactly set myself the easiest tasks, but I’ll be so pleased if I manage to make it work the way it does in my head”.

Beads, the only one of Sophia's published books that she found easy to write

And Malachy?

“Picture books are my first love. I find that when I go teenage - Georgie, Who is Jesse Flood? for example - I go all angsty. I find that I become the age I was then, in a strange way. I've decided that I much prefer to inhabit the young happy enquiring Malachy than the angst-ridden teen Malachy, so that's where I concentrate my efforts these days.

I also love working with illustrators, and my books becoming more than the sum of their parts - when an illustrator totally gets where I'm coming from in my story, but then adds the depth and wonder that they can bring as a gifted visual artist, true magic, a form of alchemy, can happen. My new picture book, Molly and the Stormy Sea, out this week from Graffeg, illustrated by the wonderful Andrew Whitson, is a perfect example of this”.

trailer for Molly and the Stormy Sea (c) Malachy Doyle and Andrew Whitson (2018)

I love picture books. I even found myself feeling guilty for choosing to write a (YA) novel when I’ve pledged my allegiance to picture books. But now I’m writing ‘up’ the novel (that is already planned and plotted), I’m back to continue with both. It may take many, many drafts (probably fewer than the 187 drafts Malachy had for his first picture book, and I hope fewer than the seventeen drafts Sophia did for her first published novel, Threads, before she was ready to send it off and then a further seventeen before it was finished and published, though very possibly not) but I’m ready to go with it. To accept that I’m going to learn a whole lot over the next couple of years about something new, that I’ll make a ton of mistakes along the way (like I encourage young people in schools to do, all the time), that I’ll probably feel the terror that I did when showing my picture book manuscripts back when I started, before I grew a very tough (picture book) skin. Will that toughness extend to showing people my novel? I suspect not, but I also suspect it won’t be quite as awful and raw as it was. And actually allowing yourself to be vulnerable like that is a pretty powerful thing:

Brene Brown's Ted Talk on vulnerability

I will do Jacob’s ‘picture book author’ edit on my novel where I try and cut lots of words that aren’t necessary. I am hopeful that writing this novel will also help me write early versions of picture books more quickly (if I wrote anything like as slowly with the novel, it would be many, many years before I got my first novel draft out). And that I’ll learn new things about structuring which will strengthen future picture books, too. Whatever the outcome, I will finish a first draft, and then a second, and subsequent ones, and I will learn loads –about story writing and myself. I hope that writing as a teenager won't make me get too angsty. Like Malachy, I was a much happier picture-book aged child than I was a teenager (so thanks for the warning, Malachy). And if it doesn’t end up as a published novel, well that’s not the end of the world. I will have gained much more than if I hadn’t tried (I've already read more novels in the past year than I probably had in the previous twenty). And who knows, it might even one day find itself a home…

Many thanks to Sophia Bennett, Malachy Doyle, Candy Gourlay, Wendy Meddour and Jacob Sager Weinstein for sharing their helpful thoughts on writing in both genres. If you've tried writing picture books and novels, how has the writing and planning of one type affected the writing and planning of the other? I'd love to hear from you with any thoughts, below. Juliet Clare Bell is the author of five picture books and three early readers. She would love to add the novel she is currently writing to this, but fully intends to write many more picture books, regardless.

www.julietclarebell.com

Published on June 17, 2018 23:00

June 10, 2018

Why I Paint • Garry Parsons

It’s often difficult to work out just how illustrators go about making their artwork for picture books without asking them directly and really, the not knowing adds to the mystery anyway? But, being an illustrator myself, it’s something I like to ponder over and look closely at when I fall in love with a spread from a new picture book from a talented illustrator.

I might study the illustrations to consider “How did they get that texture?” Or “What did they do to make that depth so convincing or compelling?” for example.

What I do know is that most illustrators working today deliver their final art electronically. Delivering artwork as a finished piece is apparently becoming a rarity. I know this because of the reactions I receive from publishers when I hand over my painted picture book boards. It’s not that they receive my artwork with a sour expression, far from it, what I get is often delighted gasps along with a few “oohs” and “aahs”.

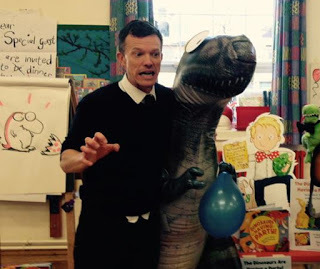

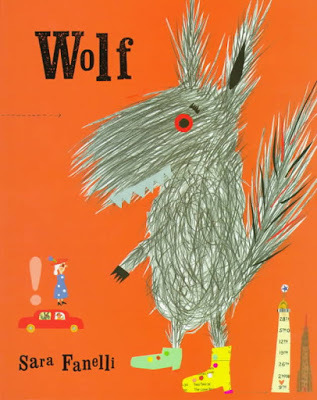

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of the oohs and aahs, but they can be accompanied by comments exclaiming how “hardly anyone delivers art this way any more” and just how “rare” it is to handle original artworks that need to be sent for scanning. It’s the “rarity” aspect that has prompted me to write, because, I realise, I’m not only painting dinosaurs, I am one!

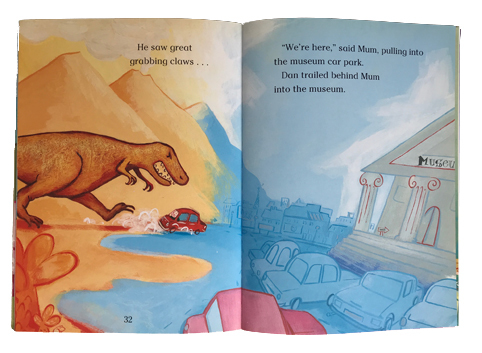

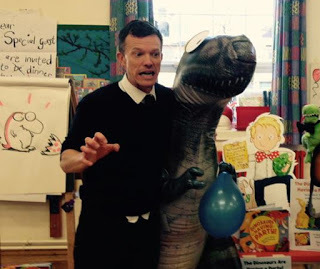

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry Parsons

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry Parsons

My art school training was as a painter on a fine art degree course back in the 90’s. British painters where prominent in the art scene at the time and the art schools reflected that appeal in what they offered to students embarking on fine art careers, those being painting, sculpture or printmaking.

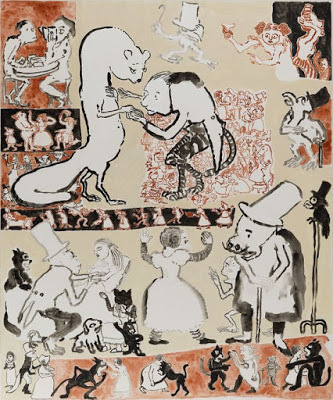

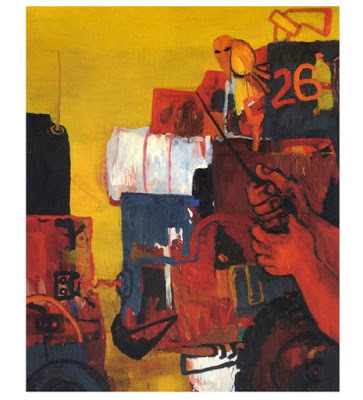

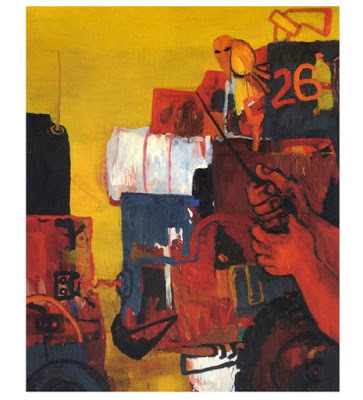

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.

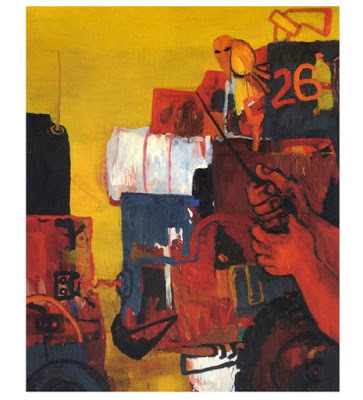

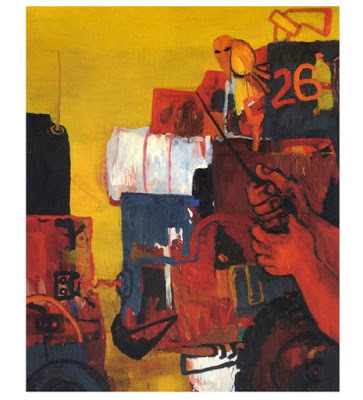

Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965

Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965

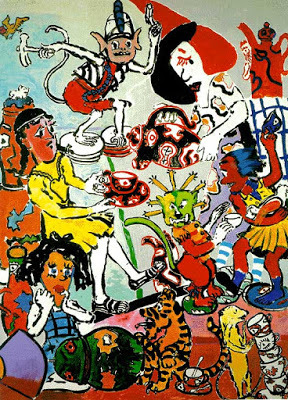

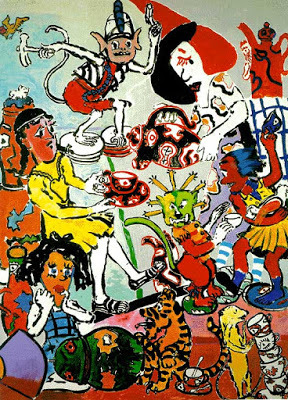

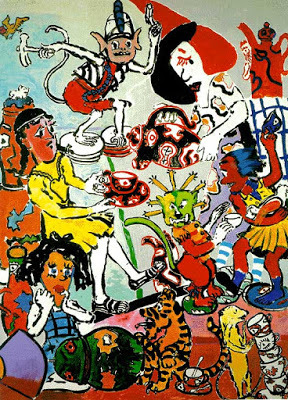

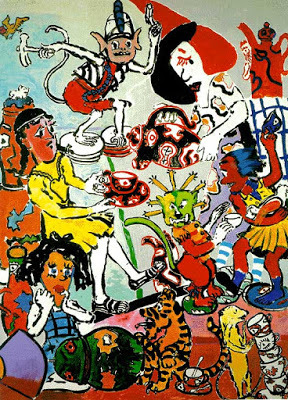

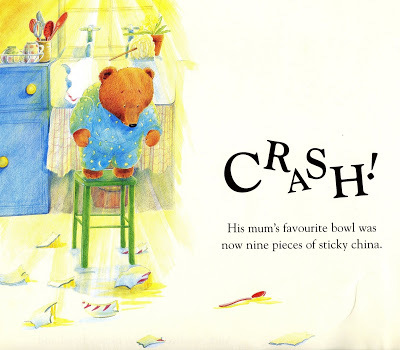

Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

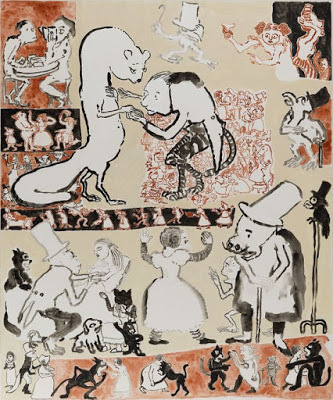

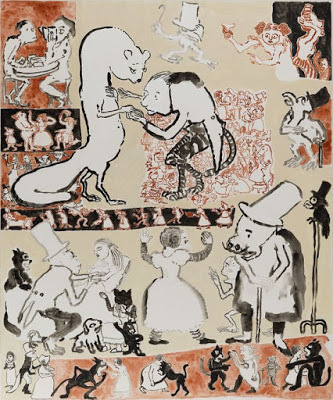

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

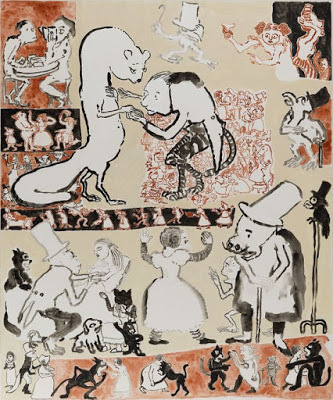

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972

Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord.

Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord.

John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972

John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972

I altered the scale of my work but continued to paint with the notion of moving towards animation and illustration. I made a monochrome book based on the opera “A Woman Without A Shadow” by Richard Strauss, a rather sinister tale about unborn children and fried fish. In my second year, and in need of a lighter subject to work on, I embarked on a short animated film depicting the life of Pythagoras, in which collaged numbers floated skyward from a very loosely painted main character, who preached to animals about numeracy. On leaving the MA, I started illustrating for editorial, my painted images appearing in Sunday supplements, newspapers and magazines, with some advertising jobs thrown in. Illustration was at an all-time high of popularity with public media, and illustration catalogues were fat with illustrators taking a share of the feast.

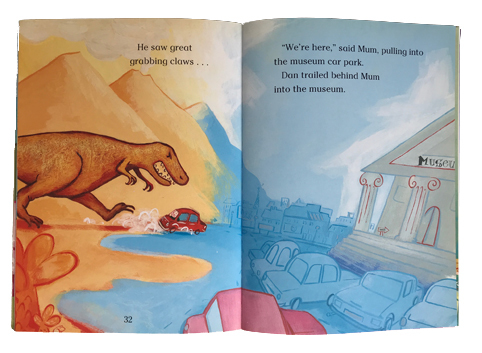

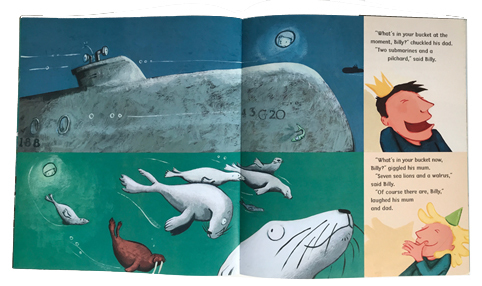

So, despite exploring and learning new graphics technologies, I continued to paint, but in a style that was more akin to children’s publishing, leading to my first publishing commissions: “Digging for Dinosaurs” by Judy Waite and then “Billy’s Bucket” by Kes Grey, first published in 2004.

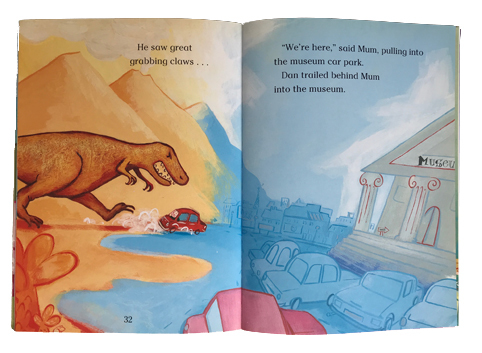

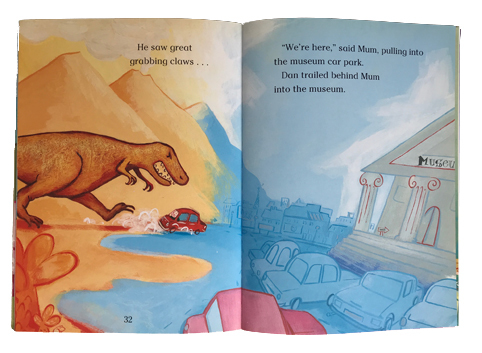

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox

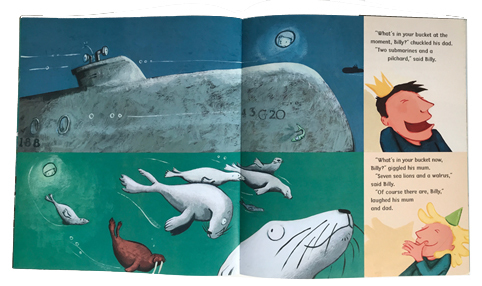

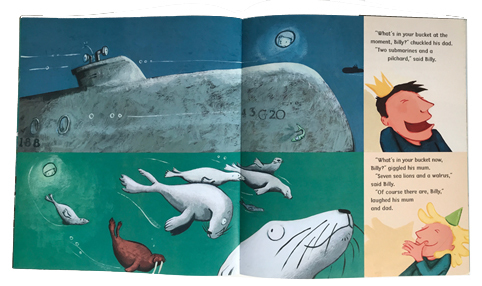

Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley Head

Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley Head

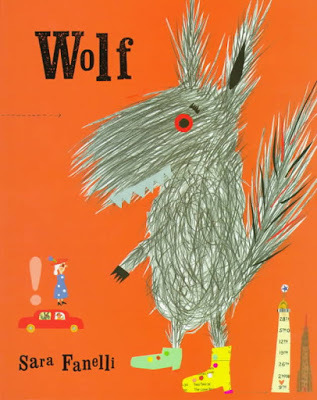

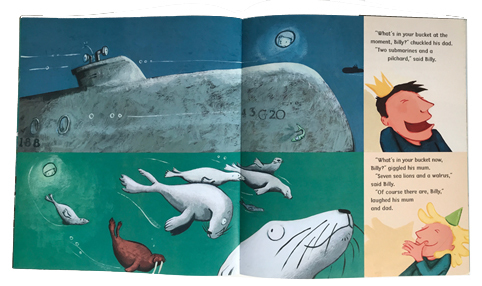

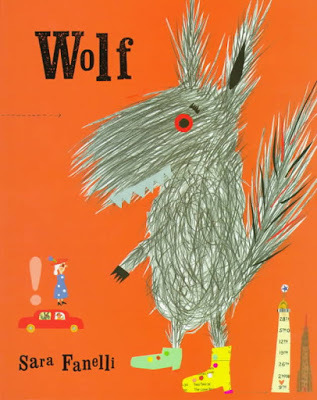

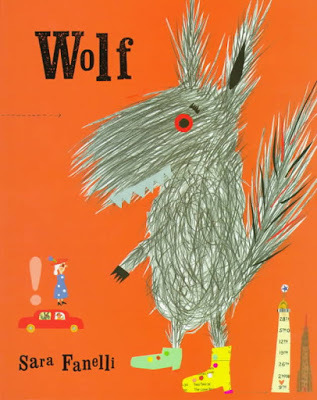

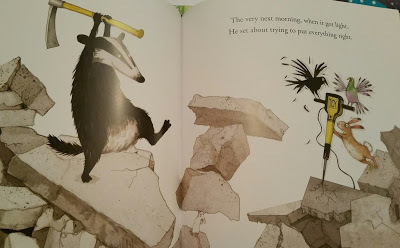

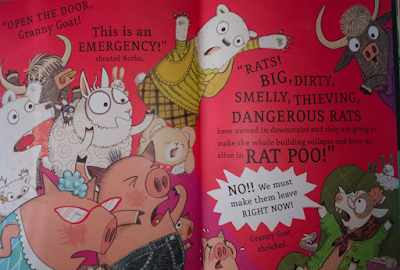

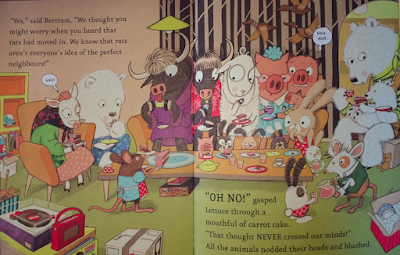

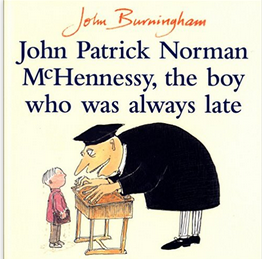

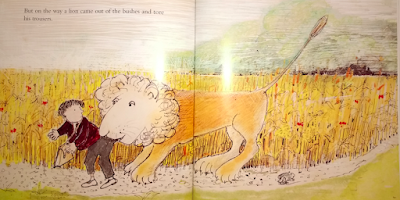

I remember enjoying the drawn, painted and multi-media approaches of Cathy Gale, Sara Fanelli and John Burningham at this time.

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.

Somewhere over the years my editorial work switched entirely to a digital format and this has more recently included some publishing work too, but painting has continued as a steady staple within my picture book illustration and the enjoyment of using paint as my main medium remains. I find great pleasure in the handling of acrylics, from the mixing of colour to it’s rough initial application through the slow development from splurges and daubs to something more refined. When I hold up original artwork to a class of year 2 students I’m often questioned about their authenticity, “are you sure they are not print-outs? Or, did you really use a brush on that?”

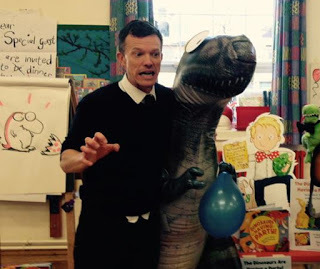

Garry Parsons.

Garry Parsons.

It's no longer the case that once the artwork is given to the publisher the next time I see it is in book form. I am increasingly working into the painted artwork digitally, it might be to add texture to a dinosaurs skin, a pattern on a piece of clothing or just a sparkle to the surface of water.

What I’m learning to embrace now is the novelty of being a dinosaur delivering painted artwork about dinosaurs.

***

You can see more of Garry's illustration for children's books on his website by clicking here. Follow on twitter @icandrawdinos

I might study the illustrations to consider “How did they get that texture?” Or “What did they do to make that depth so convincing or compelling?” for example.

What I do know is that most illustrators working today deliver their final art electronically. Delivering artwork as a finished piece is apparently becoming a rarity. I know this because of the reactions I receive from publishers when I hand over my painted picture book boards. It’s not that they receive my artwork with a sour expression, far from it, what I get is often delighted gasps along with a few “oohs” and “aahs”.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of the oohs and aahs, but they can be accompanied by comments exclaiming how “hardly anyone delivers art this way any more” and just how “rare” it is to handle original artworks that need to be sent for scanning. It’s the “rarity” aspect that has prompted me to write, because, I realise, I’m not only painting dinosaurs, I am one!

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry Parsons

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry ParsonsMy art school training was as a painter on a fine art degree course back in the 90’s. British painters where prominent in the art scene at the time and the art schools reflected that appeal in what they offered to students embarking on fine art careers, those being painting, sculpture or printmaking.

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.  Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965

Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965 Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972 Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord.

Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord. John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972

John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972I altered the scale of my work but continued to paint with the notion of moving towards animation and illustration. I made a monochrome book based on the opera “A Woman Without A Shadow” by Richard Strauss, a rather sinister tale about unborn children and fried fish. In my second year, and in need of a lighter subject to work on, I embarked on a short animated film depicting the life of Pythagoras, in which collaged numbers floated skyward from a very loosely painted main character, who preached to animals about numeracy. On leaving the MA, I started illustrating for editorial, my painted images appearing in Sunday supplements, newspapers and magazines, with some advertising jobs thrown in. Illustration was at an all-time high of popularity with public media, and illustration catalogues were fat with illustrators taking a share of the feast.

So, despite exploring and learning new graphics technologies, I continued to paint, but in a style that was more akin to children’s publishing, leading to my first publishing commissions: “Digging for Dinosaurs” by Judy Waite and then “Billy’s Bucket” by Kes Grey, first published in 2004.

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley Head

Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley HeadI remember enjoying the drawn, painted and multi-media approaches of Cathy Gale, Sara Fanelli and John Burningham at this time.

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.Somewhere over the years my editorial work switched entirely to a digital format and this has more recently included some publishing work too, but painting has continued as a steady staple within my picture book illustration and the enjoyment of using paint as my main medium remains. I find great pleasure in the handling of acrylics, from the mixing of colour to it’s rough initial application through the slow development from splurges and daubs to something more refined. When I hold up original artwork to a class of year 2 students I’m often questioned about their authenticity, “are you sure they are not print-outs? Or, did you really use a brush on that?”

Garry Parsons.

Garry Parsons.It's no longer the case that once the artwork is given to the publisher the next time I see it is in book form. I am increasingly working into the painted artwork digitally, it might be to add texture to a dinosaurs skin, a pattern on a piece of clothing or just a sparkle to the surface of water.

What I’m learning to embrace now is the novelty of being a dinosaur delivering painted artwork about dinosaurs.

***

You can see more of Garry's illustration for children's books on his website by clicking here. Follow on twitter @icandrawdinos

Published on June 10, 2018 16:46

Why I Paint

It’s often difficult to work out just how illustrators go about making their artwork for picture books without asking them directly and really, the not knowing adds to the mystery anyway? But, being an illustrator myself, it’s something I like to ponder over and look closely at when I fall in love with a spread from a new picture book from a talented illustrator.

I might study the illustrations to consider “How did they get that texture?” Or “What did they do to make that depth so convincing or compelling?” for example.

What I do know is that most illustrators working today deliver their final art electronically. Delivering artwork as a finished piece is apparently becoming a rarity. I know this because of the reactions I receive from publishers when I hand over my painted picture book boards. It’s not that they receive my artwork with a sour expression, far from it, what I get is often delighted gasps along with a few “oohs” and “aahs”.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of the oohs and aahs, but they can be accompanied by comments exclaiming how “hardly anyone delivers art this way any more” and just how “rare” it is to handle original artworks that need to be sent for scanning. It’s the “rarity” aspect that has prompted me to write, because, I realise, I’m not only painting dinosaurs, I am one!

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry Parsons

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry Parsons

My art school training was as a painter on a fine art degree course back in the 90’s. British painters where prominent in the art scene at the time and the art schools reflected that appeal in what they offered to students embarking on fine art careers, those being painting, sculpture or printmaking.

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.

Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965

Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965

Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972

Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord.

Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord.

John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972

John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972

I altered the scale of my work but continued to paint with the notion of moving towards animation and illustration. I made a monochrome book based on the opera “A Woman Without A Shadow” by Richard Strauss, a rather sinister tale about unborn children and fried fish. In my second year, and in need of a lighter subject to work on, I embarked on a short animated film depicting the life of Pythagoras, in which collaged numbers floated skyward from a very loosely painted main character, who preached to animals about numeracy. On leaving the MA, I started illustrating for editorial, my painted images appearing in Sunday supplements, newspapers and magazines, with some advertising jobs thrown in. Illustration was at an all-time high of popularity with public media, and illustration catalogues were fat with illustrators taking a share of the feast.

So, despite exploring and learning new graphics technologies, I continued to paint, but in a style that was more akin to children’s publishing, leading to my first publishing commissions: “Digging for Dinosaurs” by Judy Waite and then “Billy’s Bucket” by Kes Grey, first published in 2004.

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox

Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley Head

Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley Head

I remember enjoying the drawn, painted and multi-media approaches of Cathy Gale, Sara Fanelli and John Burningham at this time.

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.

Somewhere over the years my editorial work switched entirely to a digital format and this has more recently included some publishing work too, but painting has continued as a steady staple within my picture book illustration and the enjoyment of using paint as my main medium remains. I find great pleasure in the handling of acrylics, from the mixing of colour to it’s rough initial application through the slow development from splurges and daubs to something more refined. When I hold up original artwork to a class of year 2 students I’m often questioned about their authenticity, “are you sure they are not print-outs? Or, did you really use a brush on that?”

Garry Parsons.

Garry Parsons.

It's no longer the case that once the artwork is given to the publishing the next time I see it is in book form. I am increasingly working into the painted artwork digitally, it might be to add texture to a dinosaurs skin, a pattern on a piece of clothing or just a sparkle to the surface of water.

What I’m learning to embrace now is the novelty of being a dinosaur delivering painted artwork about dinosaurs.

***

You can see more of Garry's illustration for children's books on his website by clicking here. Follow on twitter @icandrawdinos

I might study the illustrations to consider “How did they get that texture?” Or “What did they do to make that depth so convincing or compelling?” for example.

What I do know is that most illustrators working today deliver their final art electronically. Delivering artwork as a finished piece is apparently becoming a rarity. I know this because of the reactions I receive from publishers when I hand over my painted picture book boards. It’s not that they receive my artwork with a sour expression, far from it, what I get is often delighted gasps along with a few “oohs” and “aahs”.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of the oohs and aahs, but they can be accompanied by comments exclaiming how “hardly anyone delivers art this way any more” and just how “rare” it is to handle original artworks that need to be sent for scanning. It’s the “rarity” aspect that has prompted me to write, because, I realise, I’m not only painting dinosaurs, I am one!

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry Parsons

From The Dinosaurs Are Having A Party! Gareth P Jones & Garry ParsonsMy art school training was as a painter on a fine art degree course back in the 90’s. British painters where prominent in the art scene at the time and the art schools reflected that appeal in what they offered to students embarking on fine art careers, those being painting, sculpture or printmaking.

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.

Sandwagon. Garry Parsons. 1990The well-known painters of the day used paint in such a way that brush strokes, daubs and drips were plainly visible. I relished the bold brushwork and fluid expression of paint and found myself greatly influenced by the contemporaries of the day, especially those who were figurative and those who included animal motifs in their work. I looked closely at the works of Ken Kiff, Paula Rego, Philip Guston and Eileen Cooper, to name a few.  Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965

Ken Kiff. Man Painting on Yellow. 1965 Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

Paula Rego. The Vivian Girls With The China. 1984

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

Paula Rego. La Traviata. 1983

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972

Philip Guston. The Rest Is For You. 1972 Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord.

Eileen Cooper. Woman Bathing in Her Own Tears. 1987I also liked to think that I employed a loose narrative in my paintings, which connected them together. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that the work I was producing was like a giant wall-sized picture book and that, with a reduction in scale, it might become a book. So, with this in mind, along with a few years in the desperate wilderness of becoming a painter (I sold one painting in two years!), I went back to Brighton to study on the Sequential Design MA under George Hardie and John Vernon-Lord. John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972

John Vernon-Lord. The Giant Jam Sandwich. Verses by Janet Burroway. Jonathan Cape 1972I altered the scale of my work but continued to paint with the notion of moving towards animation and illustration. I made a monochrome book based on the opera “A Woman Without A Shadow” by Richard Strauss, a rather sinister tale about unborn children and fried fish. In my second year, and in need of a lighter subject to work on, I embarked on a short animated film depicting the life of Pythagoras, in which collaged numbers floated skyward from a very loosely painted main character, who preached to animals about numeracy. On leaving the MA, I started illustrating for editorial, my painted images appearing in Sunday supplements, newspapers and magazines, with some advertising jobs thrown in. Illustration was at an all-time high of popularity with public media, and illustration catalogues were fat with illustrators taking a share of the feast.

So, despite exploring and learning new graphics technologies, I continued to paint, but in a style that was more akin to children’s publishing, leading to my first publishing commissions: “Digging for Dinosaurs” by Judy Waite and then “Billy’s Bucket” by Kes Grey, first published in 2004.

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox

Digging For Dinosaurs. Judy Waite & Garry Parsons. Red Fox Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley Head

Billy's Bucket. Kes Grey & Garry Parsons. Bodley HeadI remember enjoying the drawn, painted and multi-media approaches of Cathy Gale, Sara Fanelli and John Burningham at this time.

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Cathy Gale. All Your Own Teeth. Written by Adrienne Geoghegan. Bloomsbury

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

Sara Fanelli. Wolf. Mammoth 1997

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.

John Burningham. Oi, Get Off Our Train!. Red Fox 1991As far as I could tell, every illustrator would have been hand delivering finished original artwork to his or her publisher to be sent to the Far East to be scanned and reproduced. Once the artwork was given to your editor, the next time you saw it was in a finished book, at least it was in my case.Somewhere over the years my editorial work switched entirely to a digital format and this has more recently included some publishing work too, but painting has continued as a steady staple within my picture book illustration and the enjoyment of using paint as my main medium remains. I find great pleasure in the handling of acrylics, from the mixing of colour to it’s rough initial application through the slow development from splurges and daubs to something more refined. When I hold up original artwork to a class of year 2 students I’m often questioned about their authenticity, “are you sure they are not print-outs? Or, did you really use a brush on that?”

Garry Parsons.

Garry Parsons.It's no longer the case that once the artwork is given to the publishing the next time I see it is in book form. I am increasingly working into the painted artwork digitally, it might be to add texture to a dinosaurs skin, a pattern on a piece of clothing or just a sparkle to the surface of water.

What I’m learning to embrace now is the novelty of being a dinosaur delivering painted artwork about dinosaurs.

***

You can see more of Garry's illustration for children's books on his website by clicking here. Follow on twitter @icandrawdinos

Published on June 10, 2018 16:46

June 3, 2018

Starting to Write Children's Picture Books • Paeony Lewis

Illus by Sarah GillMaybe Lucy Rowland's blog post last week has inspired you with ideas for potential picture books. If you're itching to write, this week's blog post aims to help.