Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 37

September 2, 2018

When Science is the Fabric on which I Stitch Stories • Chitra Soundar

As a storyteller, I love retelling origin stories. I go looking for stories in my own culture and others where the nature is explained in a story full of wisdom. How the sun came to be or why the stars shimmer? Such stories are also full of emotions and life lessons.

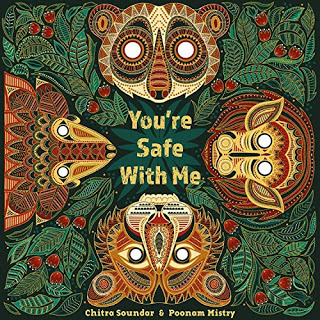

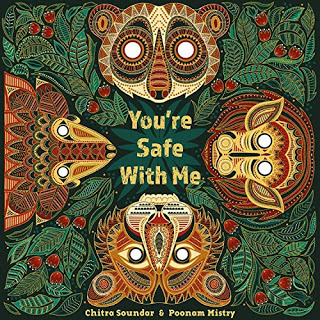

When I wrote You’re Safe With Me, that was my underlying objective – I wanted to explain thunderstorms in a poetic way while also making it scientifically accurate because science has come a long way since origin stories. Teaching children something wrong like the earth is flat will backfire when a 4-year will demonstrate to me why I’m wrong.

But the science between rains and rivers (the water cycle), the thunder and lightning didn’t require much research, I was born in the land of monsoons and I grew up near rivers and oceans.

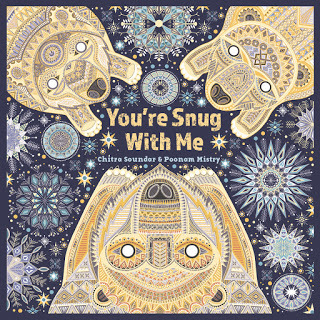

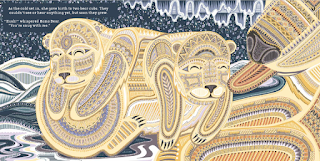

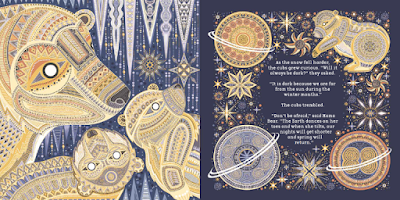

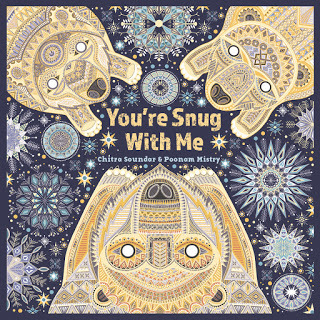

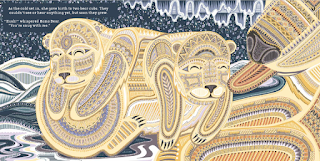

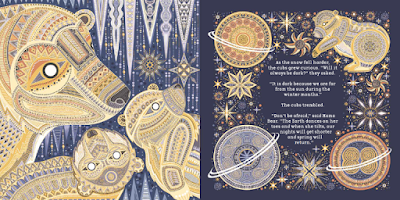

But when I came to write “You’re Snug with Me” which will be out in November 2018, the second book in the series, the story was set in the polar regions amidst a polar bear family. While keeping the words of wisdom of Mama Bear like an ancient storyteller, I also wanted to make sure that the science wasn’t wrong. But I didn’t grow up in a land of ice and snow. Even though the story is fictional and involves polar bears talking, Mama Bear needed to be poetic and factual (but not in an overt way). It would be weird to break the storyteller voice to say "And the world has risen in temperature and the snow is melting at the pace of...."

Here are the five things I learnt while writing a story that will not present any facts, but still needs to be accurate:

a) The science of description – I needed to understand the colours of the polar region through day and night, through winter and spring. What trees might grow there and what colours do they exude? Otherwise even the simplest of descriptions would ring false.

b) The science of sensory details - I needed to understand the touch, smell and sounds of the land above, the oceans beneath and the den in which these cubs spend their first few months. What does snug feel like for a cub that knows only the den?

c) The science of habitat – who else lives along with polar bears and what is the food pyramid? What would be the little bears be afraid of and who will be afraid of them?

d) The science of climate change – what are the threats to the bear cubs? What do they need to know about their world and in protecting their world?

e) The science of growing up – when do the cubs learn to swim? When do they hunt themselves? And when do they leave their mother and lead an independent life? Because it’s a scary world out there and one day these cubs will have to find food and start a new family too.

Where did I go for research?I read a lot of original research literature about pregnant polar bears in dens, how they hibernate and what they do inside. I watched videos of simulated dens that some zoos have created. I watched innumerable number of youtube videos and BBC Nature videos of polar bears and their cubsI contacted scientists and researchers who work with these magnificent beasts to ask about their specific facts.

Here is a little treat - watch the apprehension of polar bear cubs emerging out of their den for the first time.

What was my approach to writing the story itself?

a) Do initial research about the topic – that would take me two days of solid reading, getting completely lost inside Google and wandering into research rabbit holes.

b) Then I’ll write a storyboard to see if I know the scenes based on my research. Especially for this book where there is a pattern based on the first book, it was critical to know how many call and response patterns did the Mother and cubs have?

c) More research to fill in the gaps if I don’t have the 15 spreads I need. (12 if UK books, but because Lantana Publishing targets UK and US simultaneously, they prefer 15 spreads)

d) Then I will start writing the story. If I don’t know a detail, I will make a note and keep going. This is the stage where the rough draft of the text will happen and the structure will slowly emerge.

e) Over the next two stages I’ll get the structureright – when is the refrain happening – every two spreads or three? Where do page-turns happen? Will I have sounds or specific patterns of text for each group of spreads?

f) Then I go back to do specific research – I need to know about the specific animals I have used in the story or the colour of the sky or the sound of the snowdrift. This will help tighten the words and cut as many adjectives and adverbs I can.

Then finally when I’m happy, I send it to the editor, who then after a few edits, will send it to fact-checkers and her own science testers to make sure we have the facts right before we will finalise the text for illustration.

When you read the story you will hopefully not notice any science protruding like a jagged rock in the story. The aim is to create a seamlessly joyful story that works because of the science but the facts are woven into its fabric just like nature itself is.

Do you research for fictional picture books? What kind of research do you do? And how much of that is procrastination and how much of that is essential?

Chitra Soundar is an Indian-born British writer, storyteller and author of children’s books, based in London. When not writing stories or not visiting schools, Chitra fills her well with her nephews, taking photos of flowers and birds, going to museums and attending dancing classes. Find out more at www.chitrasoundar.com or follow her on twitter via @csoundar.

Chitra Soundar is an Indian-born British writer, storyteller and author of children’s books, based in London. When not writing stories or not visiting schools, Chitra fills her well with her nephews, taking photos of flowers and birds, going to museums and attending dancing classes. Find out more at www.chitrasoundar.com or follow her on twitter via @csoundar.

Published on September 02, 2018 23:00

When Science is the Fabric on which I Stitch Stories

As a storyteller, I love retelling origin stories. I go looking for stories in my own culture and others where the nature is explained in a story full of wisdom. How the sun came to be or why the stars shimmer? Such stories are also full of emotions and life lessons.

When I wrote You’re Safe With Me, that was my underlying objective – I wanted to explain thunderstorms in a poetic way while also making it scientifically accurate because science has come a long way since origin stories. Teaching children something wrong like the earth is flat will backfire when a 4-year will demonstrate to me why I’m wrong.

But the science between rains and rivers (the water cycle), the thunder and lightning didn’t require much research, I was born in the land of monsoons and I grew up near rivers and oceans.

But when I came to write “You’re Snug with Me” which will be out in November 2018, the second book in the series, the story was set in the polar regions amidst a polar bear family. While keeping the words of wisdom of Mama Bear like an ancient storyteller, I also wanted to make sure that the science wasn’t wrong. But I didn’t grow up in a land of ice and snow. Even though the story is fictional and involves polar bears talking, Mama Bear needed to be poetic and factual (but not in an overt way). It would be weird to break the storyteller voice to say "And the world has risen in temperature and the snow is melting at the pace of...."

Here are the five things I learnt while writing a story that will not present any facts, but still needs to be accurate:

a) The science of description – I needed to understand the colours of the polar region through day and night, through winter and spring. What trees might grow there and what colours do they exude? Otherwise even the simplest of descriptions would ring false.

b) The science of sensory details - I needed to understand the touch, smell and sounds of the land above, the oceans beneath and the den in which these cubs spend their first few months. What does snug feel like for a cub that knows only the den?

c) The science of habitat – who else lives along with polar bears and what is the food pyramid? What would be the little bears be afraid of and who will be afraid of them?

d) The science of climate change – what are the threats to the bear cubs? What do they need to know about their world and in protecting their world?

e) The science of growing up – when do the cubs learn to swim? When do they hunt themselves? And when do they leave their mother and lead an independent life? Because it’s a scary world out there and one day these cubs will have to find food and start a new family too.

Where did I go for research?I read a lot of original research literature about pregnant polar bears in dens, how they hibernate and what they do inside. I watched videos of simulated dens that some zoos have created. I watched innumerable number of youtube videos and BBC Nature videos of polar bears and their cubsI contacted scientists and researchers who work with these magnificent beasts to ask about their specific facts.

Here is a little treat - watch the apprehension of polar bear cubs emerging out of their den for the first time.

What was my approach to writing the story itself?

a) Do initial research about the topic – that would take me two days of solid reading, getting completely lost inside Google and wandering into research rabbit holes.

b) Then I’ll write a storyboard to see if I know the scenes based on my research. Especially for this book where there is a pattern based on the first book, it was critical to know how many call and response patterns did the Mother and cubs have?

c) More research to fill in the gaps if I don’t have the 15 spreads I need. (12 if UK books, but because Lantana Publishing targets UK and US simultaneously, they prefer 15 spreads)

d) Then I will start writing the story. If I don’t know a detail, I will make a note and keep going. This is the stage where the rough draft of the text will happen and the structure will slowly emerge.

e) Over the next two stages I’ll get the structureright – when is the refrain happening – every two spreads or three? Where do page-turns happen? Will I have sounds or specific patterns of text for each group of spreads?

f) Then I go back to do specific research – I need to know about the specific animals I have used in the story or the colour of the sky or the sound of the snowdrift. This will help tighten the words and cut as many adjectives and adverbs I can.

Then finally when I’m happy, I send it to the editor, who then after a few edits, will send it to fact-checkers and her own science testers to make sure we have the facts right before we will finalise the text for illustration.

When you read the story you will hopefully not notice any science protruding like a jagged rock in the story. The aim is to create a seamlessly joyful story that works because of the science but the facts are woven into its fabric just like nature itself is.

Do you research for fictional picture books? What kind of research do you do? And how much of that is procrastination and how much of that is essential?

Chitra Soundar is an Indian-born British writer, storyteller and author of children’s books, based in London. When not writing stories or not visiting schools, Chitra fills her well with her nephews, taking photos of flowers and birds, going to museums and attending dancing classes. Find out more at www.chitrasoundar.com or follow her on twitter via @csoundar.

Chitra Soundar is an Indian-born British writer, storyteller and author of children’s books, based in London. When not writing stories or not visiting schools, Chitra fills her well with her nephews, taking photos of flowers and birds, going to museums and attending dancing classes. Find out more at www.chitrasoundar.com or follow her on twitter via @csoundar.

Published on September 02, 2018 23:00

August 26, 2018

Continued Professional Development • Lynne Garner

As a teacher I'm expected to undertake CPD (Continued Professional Development) throughout the academic year. Thankfully, because some of my teaching involves leading creative writing sessions I'm able to double up with my CPD. That's to say I can improve my creative writing knowledge for both of my chosen careers (teacher and writer) at the same time. Recently I've had a 'splurge' of reading books about writing and I decided to share those I felt helped me. So, here they are.

As a teacher I'm expected to undertake CPD (Continued Professional Development) throughout the academic year. Thankfully, because some of my teaching involves leading creative writing sessions I'm able to double up with my CPD. That's to say I can improve my creative writing knowledge for both of my chosen careers (teacher and writer) at the same time. Recently I've had a 'splurge' of reading books about writing and I decided to share those I felt helped me. So, here they are.Plots and Plotting, How to create stories that work by Diana Kimpton

This book is broken down into easy to follow sections and covers everything from brainstorming for ideas to creating interesting characters to inventing places/worlds and crafting an original plot. Useful for authors of all genres, including picture books.

How to Write a Children's Picture book by Darcy Pattison

This book covers everything from the basics of writing a picture book to exploring picture book genres to looking at structuring a picture book. Well worth a read for beginners to learn the craft and for those who've been published and need a bit of a refresh.

From the Heart of a Copy Editor (10 most common mistakes and how to fix them) by Sheila Glasbey

From the Heart of a Copy Editor (10 most common mistakes and how to fix them) by Sheila GlasbeyToday publishers are very, very choosy about the books they publish and your manuscript (for any genre) has to be as error free as possible. I know I have a few gaps in my knowledge which is why I picked this book up.

Whilst reading this book I had a few light bulb moments and I'm hopeful some of the lessons it taught me have stuck.

A Technique for Producing Ideas by James Webb Young

This book was originally aimed at people working in the advertising industry. However, this little book (just 48 pages) has helped me generate new ideas, not only for my fiction writing but also my non-fiction.

This book was originally aimed at people working in the advertising industry. However, this little book (just 48 pages) has helped me generate new ideas, not only for my fiction writing but also my non-fiction.How to Write a Children's Picture Book (Volume I: Structure) by Eve Heidi Bine-Stock

This book explores how well known picture books are structured. It breaks them down and highlights the tools and techniques the authors has used to build an interesting and layered picture book story. There are another two titles in the series these being:

How to Write a Children's Picture Book (Volume II: Words, Sentences, Scene, Story)How to Write a Children's Picture Book (Volume III: Figures of Speech) And they are both on my reading list.

My next read will be Dear Agent - Write the Letter That Sells Your Book by Nicola Morgan. It was recommended by a writing friend after I'd moaned that I still haven't found myself an agent. As soon as she told me who had written it I knew I had to add it to my list. I've had the pleasure in meeting Nicola on a few occasions and she really does know her stuff.

My next read will be Dear Agent - Write the Letter That Sells Your Book by Nicola Morgan. It was recommended by a writing friend after I'd moaned that I still haven't found myself an agent. As soon as she told me who had written it I knew I had to add it to my list. I've had the pleasure in meeting Nicola on a few occasions and she really does know her stuff.I'm hoping one or two or the books I've suggested may help you. If you've read a book that you found useful please share and I'll add it to my reading list.

Regards

Lynne

P.S.

Just a little plug for my latest book. It's the second in my Moon Meadow Farm series and features the sly, cunning and fascinating Fox of Moon Meadow Farm (ebook just 99p). With fingers crossed the paperback will be available late September or early October 2018.

Ten short stories featuring Fox

Ten short stories featuring Fox

Published on August 26, 2018 23:00

August 19, 2018

Tips for titles: What's in a name? by Lucy Rowland

This year, I was asked to produce 4 short pieces about writing picture books for the SCBWI-BI ‘Words and Pictures’ online magazine. I chose to write about writing in rhyme, editing rhyme, picture book endings and also picture book titles.

I decided to share and expand some of my thoughts on picture book titles in this post. This is partly because, at the moment, I’m really struggling to come up with the right title for a particular story!... but also because titles are so important.

Strong titles can hook us in and make us want to pick up a book. So how do you know when you’ve found the right one? Here are some points I consider when looking for the perfect picture book title. It’s certainly not easy though and I’d love to hear your pointers too!

Be short and snappy! Tara Lazar, Children’s Book Author, writes that ‘Picture books tend to sell on concept. That concept must be communicated succinctly in order to capture a young child’s (and a parent’s) imagination. If your picture book manuscript has an overly long title, it may suggest your concept is either too vague or too complicated for the format. You want to nail down your concept and make it snappy!’Lots of picture book titles are quite short and to the point. Just having a look through my bookcase today, I notice that many of them are just 2-3 words long. For example: 'Blown away' by Rob Biddulph

'Blown away' by Rob Biddulph

'Oi Frog!' by Kes Gray and Jim Field'Daddy's Sandwich' by Pip Jones and Laura Hughes'Grandad's Island' by Benji Davies'Mr Wolf’s pancakes' by Jan Fearnley'Lost and Found' by Oliver Jeffers'Dinosaurs don’t draw!' by Elli Woollard and Steven Lenton.

Though, of course, as Tara Lazar mentions, sometimes long picture book titles stand out and can work really well, particularly if they're used to stress a key idea such as in'Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day' by Judith Viorst and Roy Cruz.

Be intriguing! I love a title that makes me want to know more. ‘There is No Dragon in this Story’ (by Lou Carter and Deborah Allwright) is a title that does just that. The cover clearly shows a dragon and yet we’re told there are no dragons in this story! So what exactly is going on here?!

And what about the unusual titles, ‘Cloudy with a chance of Meatballs’? by Judi and Ron Barrett or 'Don't let the pigeon drive the bus?' by Mo Willems. Those are titles that definitely make me want to read on.

And what about the unusual titles, ‘Cloudy with a chance of Meatballs’? by Judi and Ron Barrett or 'Don't let the pigeon drive the bus?' by Mo Willems. Those are titles that definitely make me want to read on.

Be aware of co-edition sales This is where I tend to fall down! I often come up with stories because I like experimenting with words. Many of my picture book titles are rhyming- e.g. ‘Gecko’s Echo’(illustrated by Natasha Rimmington) and others are plays on words like ‘Little Red Reading Hood’ (illustrated by Ben Mantle). But how do these titles work for co-editions where the words may not rhyme in the new language? It can be done (Little Red Reading Hood is now published in French as ‘Little Red Riding Hood who loves to read’) but it’s certainly something to consider.

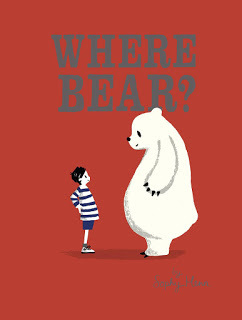

I personally really enjoy rhyming titles. In fact, ‘Where Bear’ by Sophy Henn, ‘Lucie Goose’ by Danny Baker and Pippa Cunick and ‘Follow the Track all the Way Back’ by Timothy Knapman and Ben Mantle are just a few of the rhyming titles that I currently have on my shelf.

I personally really enjoy rhyming titles. In fact, ‘Where Bear’ by Sophy Henn, ‘Lucie Goose’ by Danny Baker and Pippa Cunick and ‘Follow the Track all the Way Back’ by Timothy Knapman and Ben Mantle are just a few of the rhyming titles that I currently have on my shelf.

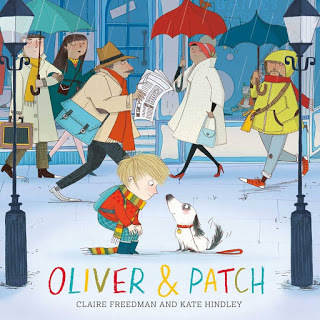

Be open to changing your title.My original text ‘Ned said No’ is now called ‘The Knight who said No’ (illustrated by Kate Hindley). ‘Stoppit Floppit’ is now titled ‘Catch that Egg’ (illustrated by Anna Chernyshova). These changes were made after discussions with my publishers who consider things such as search engine optimisation. Parents often buy books for a particular time of year- Christmas, Mother’s Day, Halloween etc or because their children are going through a particularly intense ‘dinosaur phase’. If a parent is searching for a picture book about ‘knights’, ‘dinosaurs’ or ‘Easter’- you want them to be able to find yours.Also worth considering is whether or not to use character’s names.Sometimes the character’s names don’t give us a lot to go on. They don’t give us a really clear idea of what that book is about. I’ve recently changed a title where I was using a character’s name ‘Wanda’ to one where I use ‘The Little Witch’. Again, it can be useful to think about the words that someone might search for if they are looking for a book about a particular topic. Parents often look for picture books in order to support children with fears/phobias or to help them to learn about and navigate new experiences. Is your book about worry/fear of the dark/first day of school/ a trip to the dentist? If so, is this communicated really clearly by your title?Having said that, looking again at my lovely picture book shelf, using character names certainly didn’t harm Sophy Henn with her gorgeous book ‘Edie’ or Claire Freedman and Kate Hindley with their book ‘Oliver and Patch’! Oooh this is so tricky!!

I’d love to hear some of your top tips for titles. Do you have any particular picture book titles that stand out to you?

I decided to share and expand some of my thoughts on picture book titles in this post. This is partly because, at the moment, I’m really struggling to come up with the right title for a particular story!... but also because titles are so important.

Strong titles can hook us in and make us want to pick up a book. So how do you know when you’ve found the right one? Here are some points I consider when looking for the perfect picture book title. It’s certainly not easy though and I’d love to hear your pointers too!

Be short and snappy! Tara Lazar, Children’s Book Author, writes that ‘Picture books tend to sell on concept. That concept must be communicated succinctly in order to capture a young child’s (and a parent’s) imagination. If your picture book manuscript has an overly long title, it may suggest your concept is either too vague or too complicated for the format. You want to nail down your concept and make it snappy!’Lots of picture book titles are quite short and to the point. Just having a look through my bookcase today, I notice that many of them are just 2-3 words long. For example:

'Blown away' by Rob Biddulph

'Blown away' by Rob Biddulph'Oi Frog!' by Kes Gray and Jim Field'Daddy's Sandwich' by Pip Jones and Laura Hughes'Grandad's Island' by Benji Davies'Mr Wolf’s pancakes' by Jan Fearnley'Lost and Found' by Oliver Jeffers'Dinosaurs don’t draw!' by Elli Woollard and Steven Lenton.

Though, of course, as Tara Lazar mentions, sometimes long picture book titles stand out and can work really well, particularly if they're used to stress a key idea such as in'Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day' by Judith Viorst and Roy Cruz.

Be intriguing! I love a title that makes me want to know more. ‘There is No Dragon in this Story’ (by Lou Carter and Deborah Allwright) is a title that does just that. The cover clearly shows a dragon and yet we’re told there are no dragons in this story! So what exactly is going on here?!

And what about the unusual titles, ‘Cloudy with a chance of Meatballs’? by Judi and Ron Barrett or 'Don't let the pigeon drive the bus?' by Mo Willems. Those are titles that definitely make me want to read on.

And what about the unusual titles, ‘Cloudy with a chance of Meatballs’? by Judi and Ron Barrett or 'Don't let the pigeon drive the bus?' by Mo Willems. Those are titles that definitely make me want to read on.

Be aware of co-edition sales This is where I tend to fall down! I often come up with stories because I like experimenting with words. Many of my picture book titles are rhyming- e.g. ‘Gecko’s Echo’(illustrated by Natasha Rimmington) and others are plays on words like ‘Little Red Reading Hood’ (illustrated by Ben Mantle). But how do these titles work for co-editions where the words may not rhyme in the new language? It can be done (Little Red Reading Hood is now published in French as ‘Little Red Riding Hood who loves to read’) but it’s certainly something to consider.

I personally really enjoy rhyming titles. In fact, ‘Where Bear’ by Sophy Henn, ‘Lucie Goose’ by Danny Baker and Pippa Cunick and ‘Follow the Track all the Way Back’ by Timothy Knapman and Ben Mantle are just a few of the rhyming titles that I currently have on my shelf.

I personally really enjoy rhyming titles. In fact, ‘Where Bear’ by Sophy Henn, ‘Lucie Goose’ by Danny Baker and Pippa Cunick and ‘Follow the Track all the Way Back’ by Timothy Knapman and Ben Mantle are just a few of the rhyming titles that I currently have on my shelf.

Be open to changing your title.My original text ‘Ned said No’ is now called ‘The Knight who said No’ (illustrated by Kate Hindley). ‘Stoppit Floppit’ is now titled ‘Catch that Egg’ (illustrated by Anna Chernyshova). These changes were made after discussions with my publishers who consider things such as search engine optimisation. Parents often buy books for a particular time of year- Christmas, Mother’s Day, Halloween etc or because their children are going through a particularly intense ‘dinosaur phase’. If a parent is searching for a picture book about ‘knights’, ‘dinosaurs’ or ‘Easter’- you want them to be able to find yours.Also worth considering is whether or not to use character’s names.Sometimes the character’s names don’t give us a lot to go on. They don’t give us a really clear idea of what that book is about. I’ve recently changed a title where I was using a character’s name ‘Wanda’ to one where I use ‘The Little Witch’. Again, it can be useful to think about the words that someone might search for if they are looking for a book about a particular topic. Parents often look for picture books in order to support children with fears/phobias or to help them to learn about and navigate new experiences. Is your book about worry/fear of the dark/first day of school/ a trip to the dentist? If so, is this communicated really clearly by your title?Having said that, looking again at my lovely picture book shelf, using character names certainly didn’t harm Sophy Henn with her gorgeous book ‘Edie’ or Claire Freedman and Kate Hindley with their book ‘Oliver and Patch’! Oooh this is so tricky!!

I’d love to hear some of your top tips for titles. Do you have any particular picture book titles that stand out to you?

Published on August 19, 2018 23:00

August 10, 2018

#OnlyOneOfMe: Making a picture book in just a few weeks • Michelle Robinson

We have a guest post this week from former Picture Book Den team member Michelle Robinson about

Only One of Me

, a very special picture book Michelle has written with Lisa Wells. You can find out more about the project and read the book's text on Michelle's blog.

I swear: no deadline will ever stress me out again.Since announcing our intention to produce #OnlyOneOfMe on July 31st, it's been go, go, go. With the help of my amazing agent, James Catchpole I've been spearheading a campaign to make a top quality heirloom picture book for charity.

Thankfully there isn't only one of me. The team is small but tight knit, and everyone is pulling together to make it happen. Illustrators Catalina Echeverri and Tim Budgen are currently burning the midnight oil, more than earning the right to be referred to as, "The hardest working people in the business".

Before the nitty gritty: I'm auctioning the rare opportunity to have an in-depth picture book manuscript critique with me, with all proceeds going to the fund. You can bid here!

Let me tell you a little about the book: Written from the perspective of a terminally ill parent, Only One Of Me is an expression of undying love for their children. What makes it so unique is that it was written by someone in that terrible situation.

Lisa and baby SaffiaLisa Wells was diagnosed with stage 4 bowel and liver cancer at the end of 2017. Her doctors told her she has between just two and twelve months to live. Lisa and her husband Dan have two lovely little girls, Ava-Lily, 5 and Saffia, 9 months. I don't need to say anything more about it, really. It's too sad to think about. But for Lisa and Dan there's no getting away from it.

Lisa and baby SaffiaLisa Wells was diagnosed with stage 4 bowel and liver cancer at the end of 2017. Her doctors told her she has between just two and twelve months to live. Lisa and her husband Dan have two lovely little girls, Ava-Lily, 5 and Saffia, 9 months. I don't need to say anything more about it, really. It's too sad to think about. But for Lisa and Dan there's no getting away from it.

How do you go about preparing yourself to leave everyone you hold dear behind? I can only begin to imagine, and I'm so glad that for me it's just hypothetical. I wish I had a magic wand and could change the future for Lisa. The only wand I have is my pen - so I've given it a wave with Lisa's help.

Our story is designed to help dying parents express their feelings, giving them a lasting and tangible token of comfort to leave behind. Thanks to Lisa's courage, energy and loving nature - and thanks to all the people who are donating, spreading the word and supporting the Only One Of Me team throughout this crazy busy time - her voice will bring comfort not just to her own family but countless others like them.

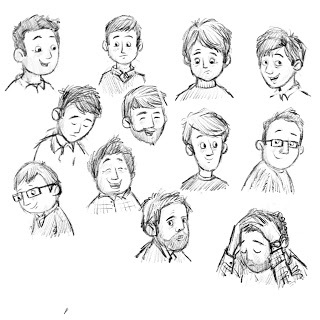

So how do you create a picture book in just a few weeks? You fly by the seat of your pants and call in favours from as many generous experts as you can! Tim's initial character sketches for dadWe were inundated with hundreds of submissions from illustrators. I reckon we had to make our decision faster than any editor ever in the history of publishing! We chose to go with both Tim and Catalina. This way we could produce two different books - one for mums, one for dads - with the freedom to draw human characters instead of gender neutral animals. It also meant no single artist was going to bear the burden of the project alone. The two are forming a great partnership behind the scenes, supporting one another in every decision - there are so many to make, and we have to make them at break neck speed!

Tim's initial character sketches for dadWe were inundated with hundreds of submissions from illustrators. I reckon we had to make our decision faster than any editor ever in the history of publishing! We chose to go with both Tim and Catalina. This way we could produce two different books - one for mums, one for dads - with the freedom to draw human characters instead of gender neutral animals. It also meant no single artist was going to bear the burden of the project alone. The two are forming a great partnership behind the scenes, supporting one another in every decision - there are so many to make, and we have to make them at break neck speed!

What should the characters look like? How can we be sure to make the characters diverse and inclusive? How do we convey the depth of sorrow involved while ultimately providing comfort? What colour scheme? What type style? Spreads? Single pages? The list is endless! Thankfully Catalina and Tim have plenty of support.

The counsellors at WHY We Hear You, our official charity partner, have been helping guide us, as have our publisher, Graffeg and my own super agent, James Catchpole. It's faster, easier and cheaper to get Tim and Catalina together in London (Graffeg are based in Cardiff Bay) for a brainstorming session, so my friends at Walker Books have offered to host, feed and advise them on Tuesday 14th August. In short, Tim and Catalina have a lot of support - but even so, they basically have to create a spread a day to meet our August 30th deadline.

We are so close to full funding - and we print on September 21st!

Huge thanks to Rob Hayward and the team at CPI Antony Rowe, Melksham, and are aiming to hold a fundraising launch party on the same day. To say timings are tight is an understatement! If the books aren't ready in time, we'll be celebrating thin air! We simply can't afford to mess this up.

But we won't. The whole team is dedicated, committed and fired up. We are determined that Lisa will get to enjoy the thrill and satisfaction of seeing her book in print before she dies.

DONATE HERE!

Thank you to everybody who has read the story, spread the news, donated and sent words of encouragement! It means so much. We've had donations ranging from £2 to £250 and every single one is equally appreciated. The more we raise, the more books we can ultimately print - our bookbinders are very generously doing the first run free of charge, which is phenomenal, but we predict a bit of a frenzy in sales!

I should say that the book will be available to everyone, but has been designed as a resource for dying parents. Do keep a copy on your shelf, but be careful sharing it with young children if you're a parent in fine fettle! We wouldn't want to cause any undue anxiety! You will have the option to buy copies and donate them directly to charity, either under your own steam or via WHY We Hear You, who will help see that the books get to where they're most needed.

I should say that the book will be available to everyone, but has been designed as a resource for dying parents. Do keep a copy on your shelf, but be careful sharing it with young children if you're a parent in fine fettle! We wouldn't want to cause any undue anxiety! You will have the option to buy copies and donate them directly to charity, either under your own steam or via WHY We Hear You, who will help see that the books get to where they're most needed.

So wish us luck! Luxuriate in your deadlines! And above all, live, laugh and love. Michelle x

Michelle Robinson is the bestselling author of picture books such as A Beginner's Guide to Bear Spotting and Goodnight Spaceman

I swear: no deadline will ever stress me out again.Since announcing our intention to produce #OnlyOneOfMe on July 31st, it's been go, go, go. With the help of my amazing agent, James Catchpole I've been spearheading a campaign to make a top quality heirloom picture book for charity.

Thankfully there isn't only one of me. The team is small but tight knit, and everyone is pulling together to make it happen. Illustrators Catalina Echeverri and Tim Budgen are currently burning the midnight oil, more than earning the right to be referred to as, "The hardest working people in the business".

Before the nitty gritty: I'm auctioning the rare opportunity to have an in-depth picture book manuscript critique with me, with all proceeds going to the fund. You can bid here!

Let me tell you a little about the book: Written from the perspective of a terminally ill parent, Only One Of Me is an expression of undying love for their children. What makes it so unique is that it was written by someone in that terrible situation.

Lisa and baby SaffiaLisa Wells was diagnosed with stage 4 bowel and liver cancer at the end of 2017. Her doctors told her she has between just two and twelve months to live. Lisa and her husband Dan have two lovely little girls, Ava-Lily, 5 and Saffia, 9 months. I don't need to say anything more about it, really. It's too sad to think about. But for Lisa and Dan there's no getting away from it.

Lisa and baby SaffiaLisa Wells was diagnosed with stage 4 bowel and liver cancer at the end of 2017. Her doctors told her she has between just two and twelve months to live. Lisa and her husband Dan have two lovely little girls, Ava-Lily, 5 and Saffia, 9 months. I don't need to say anything more about it, really. It's too sad to think about. But for Lisa and Dan there's no getting away from it.How do you go about preparing yourself to leave everyone you hold dear behind? I can only begin to imagine, and I'm so glad that for me it's just hypothetical. I wish I had a magic wand and could change the future for Lisa. The only wand I have is my pen - so I've given it a wave with Lisa's help.

Our story is designed to help dying parents express their feelings, giving them a lasting and tangible token of comfort to leave behind. Thanks to Lisa's courage, energy and loving nature - and thanks to all the people who are donating, spreading the word and supporting the Only One Of Me team throughout this crazy busy time - her voice will bring comfort not just to her own family but countless others like them.

So how do you create a picture book in just a few weeks? You fly by the seat of your pants and call in favours from as many generous experts as you can!

Tim's initial character sketches for dadWe were inundated with hundreds of submissions from illustrators. I reckon we had to make our decision faster than any editor ever in the history of publishing! We chose to go with both Tim and Catalina. This way we could produce two different books - one for mums, one for dads - with the freedom to draw human characters instead of gender neutral animals. It also meant no single artist was going to bear the burden of the project alone. The two are forming a great partnership behind the scenes, supporting one another in every decision - there are so many to make, and we have to make them at break neck speed!

Tim's initial character sketches for dadWe were inundated with hundreds of submissions from illustrators. I reckon we had to make our decision faster than any editor ever in the history of publishing! We chose to go with both Tim and Catalina. This way we could produce two different books - one for mums, one for dads - with the freedom to draw human characters instead of gender neutral animals. It also meant no single artist was going to bear the burden of the project alone. The two are forming a great partnership behind the scenes, supporting one another in every decision - there are so many to make, and we have to make them at break neck speed!What should the characters look like? How can we be sure to make the characters diverse and inclusive? How do we convey the depth of sorrow involved while ultimately providing comfort? What colour scheme? What type style? Spreads? Single pages? The list is endless! Thankfully Catalina and Tim have plenty of support.

The counsellors at WHY We Hear You, our official charity partner, have been helping guide us, as have our publisher, Graffeg and my own super agent, James Catchpole. It's faster, easier and cheaper to get Tim and Catalina together in London (Graffeg are based in Cardiff Bay) for a brainstorming session, so my friends at Walker Books have offered to host, feed and advise them on Tuesday 14th August. In short, Tim and Catalina have a lot of support - but even so, they basically have to create a spread a day to meet our August 30th deadline.

We are so close to full funding - and we print on September 21st!

Huge thanks to Rob Hayward and the team at CPI Antony Rowe, Melksham, and are aiming to hold a fundraising launch party on the same day. To say timings are tight is an understatement! If the books aren't ready in time, we'll be celebrating thin air! We simply can't afford to mess this up.

But we won't. The whole team is dedicated, committed and fired up. We are determined that Lisa will get to enjoy the thrill and satisfaction of seeing her book in print before she dies.

DONATE HERE!

Thank you to everybody who has read the story, spread the news, donated and sent words of encouragement! It means so much. We've had donations ranging from £2 to £250 and every single one is equally appreciated. The more we raise, the more books we can ultimately print - our bookbinders are very generously doing the first run free of charge, which is phenomenal, but we predict a bit of a frenzy in sales!

I should say that the book will be available to everyone, but has been designed as a resource for dying parents. Do keep a copy on your shelf, but be careful sharing it with young children if you're a parent in fine fettle! We wouldn't want to cause any undue anxiety! You will have the option to buy copies and donate them directly to charity, either under your own steam or via WHY We Hear You, who will help see that the books get to where they're most needed.

I should say that the book will be available to everyone, but has been designed as a resource for dying parents. Do keep a copy on your shelf, but be careful sharing it with young children if you're a parent in fine fettle! We wouldn't want to cause any undue anxiety! You will have the option to buy copies and donate them directly to charity, either under your own steam or via WHY We Hear You, who will help see that the books get to where they're most needed.So wish us luck! Luxuriate in your deadlines! And above all, live, laugh and love. Michelle x

Michelle Robinson is the bestselling author of picture books such as A Beginner's Guide to Bear Spotting and Goodnight Spaceman

Published on August 10, 2018 07:03

August 5, 2018

Are you famous? by Jane Clarke

Over the last few weeks, I’ve done assorted school and library events for the under 8 year olds, and, when it’s time to chat, I've been asked “are you famous?” They’re puzzled because I’m standing in front of them, being introduced as a special visitor - yet they haven’t seen my face on TV - and won’t have heard of my name, except in the context of that event.

Sky Private Eye (illustrated by Loretta Schauer) - Jane at the event at Barnes Lit Fest

If I ask the children if they know any picture book writers or illustrators, the name they most often come up with is Julia Donaldson. They know her as the author of the Gruffalo books, but they often struggle to name Axel Scheffler as the illustrator - or to add any more names to the list. The majority of picture book writers and illustrators are invisible to them. But when I ask the same children what picture books they love, their eyes light up. They know the title and the characters and can’t wait to tell me all about the story. They remember who read their favourite book to them, how it made them feel - and how they requested it to be read again, and again, and again. The book is etched into their hearts and has become part of their childhoods.

But when I ask the same children what picture books they love, their eyes light up. They know the title and the characters and can’t wait to tell me all about the story. They remember who read their favourite book to them, how it made them feel - and how they requested it to be read again, and again, and again. The book is etched into their hearts and has become part of their childhoods.

Most adults I’ve asked can also recollect in detail the stories the picture books they loved as a child, and see the illustrations in their mind’s eye - even if they can’t remember the name of the author and illustrator. Often, as adults, they have sought out the book they loved as a child so they can read it to their children.

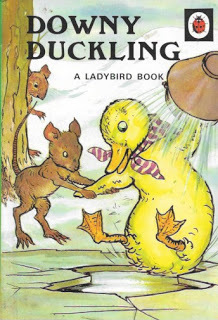

I had to track down Downy Duckling (Ladybird Books, fist published 1942!) to share with my sons. I had no idea who wrote and illustrated it -the names of AJ MacGregor and W Perring are not on the cover.

I had to track down Downy Duckling (Ladybird Books, fist published 1942!) to share with my sons. I had no idea who wrote and illustrated it -the names of AJ MacGregor and W Perring are not on the cover.

So when I’m asked “are you famous?” I explain that not many people know my name or what I look like, but they might know and love some of the stories I’ve created - and that sort of fame makes me very happy.

In the case of the picture books I’ve written, Gilbert the Great is probably the best known, thanks to Charles Fuge’s wonderful illustrations, and this summer, in the USA, there was even a Gilbert plush in Kohl’s, helping to raise money for Kohl’s Cares charities.

In the case of the picture books I’ve written, Gilbert the Great is probably the best known, thanks to Charles Fuge’s wonderful illustrations, and this summer, in the USA, there was even a Gilbert plush in Kohl’s, helping to raise money for Kohl’s Cares charities.

Do you have a favourite picture book you remember as a child, but didn’t find out the names of the author and/or illustrator until you were much older?

Jane also often gets asked “are you rich?” She answered that question in this post https://picturebookden.blogspot.com/2017/03/are-you-rich-by-jane-clarke.htmlNothing has changed, except she’s now even richer in granddaughers (4)!

Sky Private Eye (illustrated by Loretta Schauer) - Jane at the event at Barnes Lit Fest

If I ask the children if they know any picture book writers or illustrators, the name they most often come up with is Julia Donaldson. They know her as the author of the Gruffalo books, but they often struggle to name Axel Scheffler as the illustrator - or to add any more names to the list. The majority of picture book writers and illustrators are invisible to them.

But when I ask the same children what picture books they love, their eyes light up. They know the title and the characters and can’t wait to tell me all about the story. They remember who read their favourite book to them, how it made them feel - and how they requested it to be read again, and again, and again. The book is etched into their hearts and has become part of their childhoods.

But when I ask the same children what picture books they love, their eyes light up. They know the title and the characters and can’t wait to tell me all about the story. They remember who read their favourite book to them, how it made them feel - and how they requested it to be read again, and again, and again. The book is etched into their hearts and has become part of their childhoods.Most adults I’ve asked can also recollect in detail the stories the picture books they loved as a child, and see the illustrations in their mind’s eye - even if they can’t remember the name of the author and illustrator. Often, as adults, they have sought out the book they loved as a child so they can read it to their children.

I had to track down Downy Duckling (Ladybird Books, fist published 1942!) to share with my sons. I had no idea who wrote and illustrated it -the names of AJ MacGregor and W Perring are not on the cover.

I had to track down Downy Duckling (Ladybird Books, fist published 1942!) to share with my sons. I had no idea who wrote and illustrated it -the names of AJ MacGregor and W Perring are not on the cover.So when I’m asked “are you famous?” I explain that not many people know my name or what I look like, but they might know and love some of the stories I’ve created - and that sort of fame makes me very happy.

In the case of the picture books I’ve written, Gilbert the Great is probably the best known, thanks to Charles Fuge’s wonderful illustrations, and this summer, in the USA, there was even a Gilbert plush in Kohl’s, helping to raise money for Kohl’s Cares charities.

In the case of the picture books I’ve written, Gilbert the Great is probably the best known, thanks to Charles Fuge’s wonderful illustrations, and this summer, in the USA, there was even a Gilbert plush in Kohl’s, helping to raise money for Kohl’s Cares charities. Do you have a favourite picture book you remember as a child, but didn’t find out the names of the author and/or illustrator until you were much older?

Jane also often gets asked “are you rich?” She answered that question in this post https://picturebookden.blogspot.com/2017/03/are-you-rich-by-jane-clarke.htmlNothing has changed, except she’s now even richer in granddaughers (4)!

Published on August 05, 2018 22:00

July 22, 2018

From Nursery Rhyme to Picture Book, by Pippa Goodhart

Nursery rhymes are often nonsensical, at least to modern child understanding, and yet they persist, generation to generation, often having lasted hundreds of years. Why? It’s the rhythm and the rhyme and the repetition that makes them memorable and easy to join in with, as well as nice to rock a baby to. Those three ‘r’s, rhythm, rhyme and repetition, are often found in picture book stories for young children for those same reasons. So it makes good, clever, sense to use an established old rhyme as the basis for a new picture book story. Here are three such books which work wonderfully well –

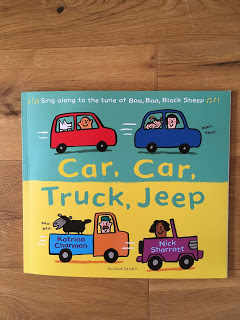

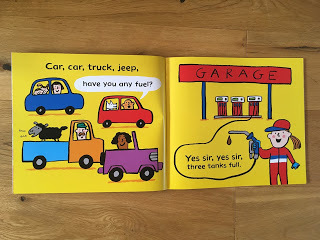

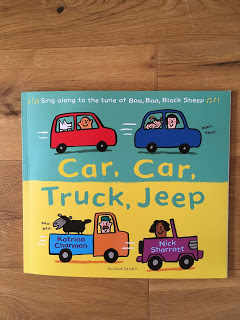

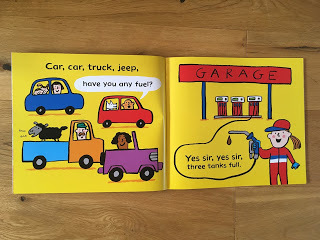

Brand new, bright and fun, full of vehicles and sounds, with a proper mix of people driving the many vehicles, is Car, Car, Truck, Jeep, written by Katrina Charman and illustrated by Nick Sharratt. This whizz along with busy vehicles comes to a nicely sleepy end, and matches the pattern of rhythm and rhyme laid out in Baa Baa Black Sheep … ‘Baa baa black sheep, have you any wool? Yes, sir. Yes, sir, three bags full. One for the master. One for the dame. One for the little boy who lives down the lane.’

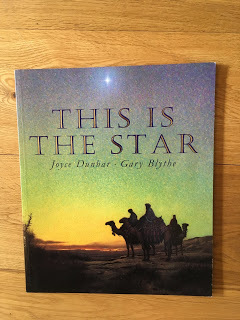

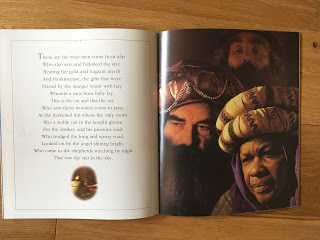

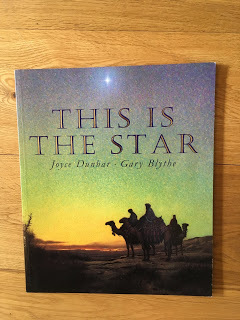

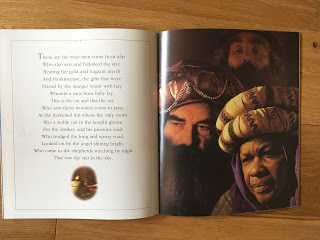

Quieter, and more sophisticated, but wonderfully powerful, is This Is The Star, written by Joyce Dunbar and illustrated by Gary Blythe. This tells the Christmas story, mirroring the cumulative rhyme that is This Is The House That Jack Built … ‘ This is the house that Jack built. This is the malt that lay in the house that Jack built. This is the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built. This is the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt … and so on for many more verses.’ The big problem with a cumulative story is that the text gets bulkier and the pictures more crowded, meaning that the finale can all look at bit small. But Joyce Dunbar punctures that with a spread that breaks that pattern startlingly to give us, ‘This is the child that was born.’

Each Peach, Pear, Plum by Janet and Alan Ahlberg is, of course an old favourite. The original playground rhyme seems to go something like, ‘Each, peach, pear, plum, out goes Tom Thumb. Tom Thumb won’t do so out goes Betty Blue. Betty Blue won’t go, so out goes you!’ It’s one of those rhymes for eliminating a child at a time in order to choose who will be 'It' for a game. The Ahlbergs took the structure, and the idea of playing with familiar nursery rhyme or fairytale characters, from that rhyme, and made a classic of it.

[image error]

Do you know of any other picture books based on well-known children’s rhymes? Can you suggest a rhyme ripe for such picture book treatment?

Brand new, bright and fun, full of vehicles and sounds, with a proper mix of people driving the many vehicles, is Car, Car, Truck, Jeep, written by Katrina Charman and illustrated by Nick Sharratt. This whizz along with busy vehicles comes to a nicely sleepy end, and matches the pattern of rhythm and rhyme laid out in Baa Baa Black Sheep … ‘Baa baa black sheep, have you any wool? Yes, sir. Yes, sir, three bags full. One for the master. One for the dame. One for the little boy who lives down the lane.’

Quieter, and more sophisticated, but wonderfully powerful, is This Is The Star, written by Joyce Dunbar and illustrated by Gary Blythe. This tells the Christmas story, mirroring the cumulative rhyme that is This Is The House That Jack Built … ‘ This is the house that Jack built. This is the malt that lay in the house that Jack built. This is the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built. This is the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt … and so on for many more verses.’ The big problem with a cumulative story is that the text gets bulkier and the pictures more crowded, meaning that the finale can all look at bit small. But Joyce Dunbar punctures that with a spread that breaks that pattern startlingly to give us, ‘This is the child that was born.’

Each Peach, Pear, Plum by Janet and Alan Ahlberg is, of course an old favourite. The original playground rhyme seems to go something like, ‘Each, peach, pear, plum, out goes Tom Thumb. Tom Thumb won’t do so out goes Betty Blue. Betty Blue won’t go, so out goes you!’ It’s one of those rhymes for eliminating a child at a time in order to choose who will be 'It' for a game. The Ahlbergs took the structure, and the idea of playing with familiar nursery rhyme or fairytale characters, from that rhyme, and made a classic of it.

[image error]

Do you know of any other picture books based on well-known children’s rhymes? Can you suggest a rhyme ripe for such picture book treatment?

Published on July 22, 2018 16:30

July 15, 2018

A Space For the Reader • Susannah Lloyd

Please welcome our latest guest to the Picture Book Den - Susannah Lloyd.

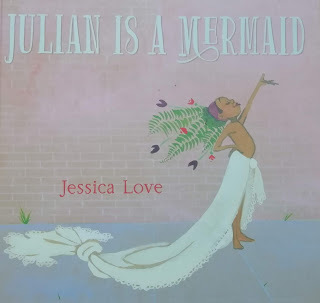

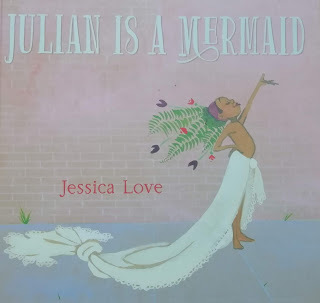

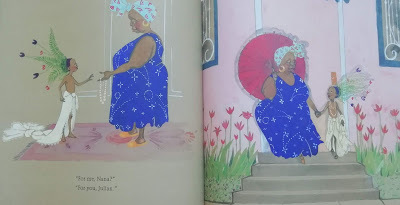

Ursula Le Guin once wrote: ‘The unread story is not a story; it is little black marks on woodpulp. The reader, reading it, makes it live: a live thing, a story.’ This could not be truer than for a picture book, a book for the very young; for readers absolutely brimming with the imagination required to bring a story to life. All my favourite picture book authors take a very wry and playful approach with their readers. They resist the temptation to wrap things up so neatly that there is nothing left for the reader to do. Instead they trust their readers enough to let them take an idea, let their imagination loose and just run with it. As Le Guin put it ‘You can consider the reader, not a helpless victim or a passive consumer, but as an active, worthy collaborator. A colluder, a co-illusionist.’ But it needs careful consideration to make the most of your colluder’s valuable time and attention. Mac Barnett, discussing his stories on the Picture Book Podcast, said of his work “I write a thing that has lots of gaps for [the illustrator] to fill in and then ideally, when the illustrator is done, there are still gaps for the person who is reading the book out loud to fill in and put their own spin on it, and then finally there still should be some spaces for the reader to crawl into and figure those things out.” To listen to the podcast in full click here. This is a topic dear to my heart. I am a new picture book writer and it’s what I’m always striving to achieve my own writing. Needless to say, I have found that it is trickier than it first appears! One recent book that really carries this off is Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love. I absolutely love this book. It is quiet, beautiful, thought-provoking and very moving. It had me sniffing back the tears before I even got it out of the book shop.

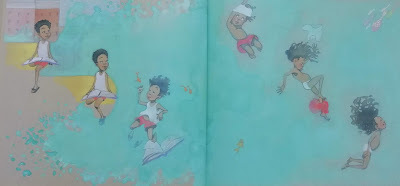

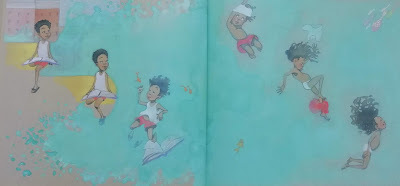

Julian, a little boy, watches some glamourous women in mermaid costumes on his bus ride home from the swimming pool, and becomes totally lost in a day dream, imagining himself as a glorious mermaid. JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love.

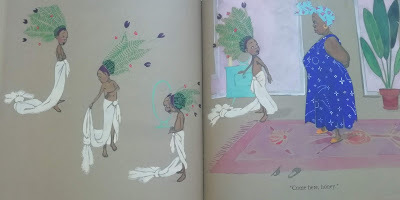

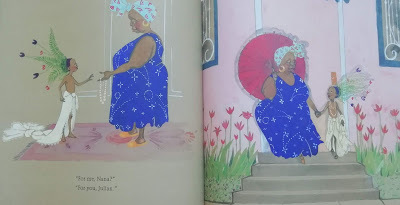

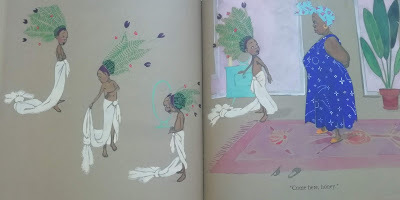

Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.On the way into their house he declares to his grandmum “Nana, I am also a mermaid.” When she goes off for a bath he looks about the house and bedecks himself in everything he can find to transform himself into a mermaid. What will she make of his flamboyant homemade costume when she returns from her bath?

The text of Julian is very minimal, and the words tell us nothing at all about what the characters of Julian or Nana are thinking or feeling. That is 100% the job of the reader to work out. When his Nana returns from her bath and finds him dressed up in her curtains, plant and makeup, she says nothing but disappears off, leaving us alone with Julian for a very suspense-filled spread. Julian suddenly looks a little vulnerable, a little uncertain, as he peers at himself in the mirror. JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.The fact that the readers are invited to fill these spaces themselves, and make their own connections, creates a gentle opportunity for them to experience getting things wrong, and then for them to re-evaluate assumptions that they may have made. When we turned the page my youngest son, quite certain that Julian would be in trouble, jumped back on the sofa, and looked cautiously through his fingers, finally taking his hands away and giving the page a long thoughtful stare. When Nana returns with a necklace to complete his costume, there are no words to tell us about how Julian feels about this, but there don’t need to be – the reader has felt it for themselves.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.The fact that the readers are invited to fill these spaces themselves, and make their own connections, creates a gentle opportunity for them to experience getting things wrong, and then for them to re-evaluate assumptions that they may have made. When we turned the page my youngest son, quite certain that Julian would be in trouble, jumped back on the sofa, and looked cautiously through his fingers, finally taking his hands away and giving the page a long thoughtful stare. When Nana returns with a necklace to complete his costume, there are no words to tell us about how Julian feels about this, but there don’t need to be – the reader has felt it for themselves.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.I recently listened to an interview with Jessica on the Picture Book Podcast. She said that, in creating a book like Julian, she is “Throwing a ball up into the air, into the unknown, and the reader…has the opportunity to catch it….and the magic of catching it can’t happen unless it’s actually been thrown. If someone just stuffs it into your hand, you haven’t caught anything, you’ve been handed something, and that’s not the same thing.” To listen to this interview in full click here.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.I recently listened to an interview with Jessica on the Picture Book Podcast. She said that, in creating a book like Julian, she is “Throwing a ball up into the air, into the unknown, and the reader…has the opportunity to catch it….and the magic of catching it can’t happen unless it’s actually been thrown. If someone just stuffs it into your hand, you haven’t caught anything, you’ve been handed something, and that’s not the same thing.” To listen to this interview in full click here.

This idea really struck me. I thought yes! This is exactly what I want to do in my own writing! So, to learn more about the subtle art of the throwing, I decided to contact Jessica and ask her about this.

Questions:

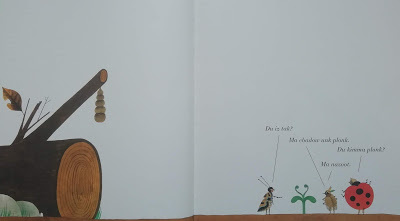

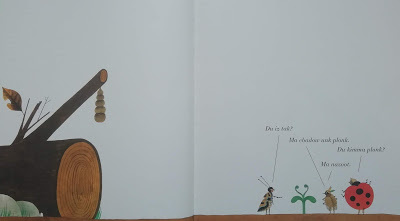

Film Director Ernst Lubitsch apparently said: “Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever”. I am completely hooked on trying to achieve this in my picture book stories. What are your thoughts on why this approach makes for such a satisfying an experience for the picture book reader, in particular?This quote is a bullseye. I've worked for the last 13 years as an actor in the theatre--I trained at Juilliard and have been performing in plays ever since. One of the great assets of live performance is the immediate, legible feedback you get from an audience. You know when you have the audience, and you can feel it when you've lost them. Here's what audiences hate: being preached at. Here's what audiences love: making connections on their own. I feel confident saying this is as close to a universal rule as there is in the theatre: show don't tell. But the why of it is what you are asking about, and I've actually spent a lot of time thinking about this and here's what it boils down to: art isn't the object itself. Art isn't the finished book, or painting, or script. That is just the set-up. I think of it this way, art is the thing that happens when an idea travels from the mind of the artist to the mind of the viewer. It's like an electrical impulse leaping from one dendrite to the next. It is the leaping part that is magical. That is the miraculous current that gives the artist and the reader a little zap when they touch it. I think the reason this kind of story is so much more satisfying for the reader, is it allows them to participate, and do their job. I believe artists need to have enough respect for their readers to know when their job is finished, and allow the reader to do theirs. How do you ensure you don’t crowd out the reader’s space or role in your stories, and do you feel it helps that you are both the author and illustrator of the book? That is the question isn't it? How do you actually do it? I think the trick is to think of the reader as your collaborator. It is your job to set them up with the information they need, but connecting the dots is actually their job, not yours. When I first sold Julián is a Mermaid we toyed with the idea of making it entirely wordless. But here's the problem with that: if the reader doesn't have the information from the very beginning that Julián is a boy the reader doesn't have the right coordinates from which to start--they just assume he is a girl and never go on the journey. I think it is always a matter of asking, what is the least amount of information I can give the reader in order for them to make a connection? The bigger the leap, the more satisfying it is for them; the more thrilling the game of catch between you. What books have you loved which leave lots of room for the reader?"Du Iz Tak?", written and illustrated by Carson Ellis. It is a masterpiece and it is in a made-up, bug language! And do kids get bored? No! They lean forward because finally someone has given them something to figure out!

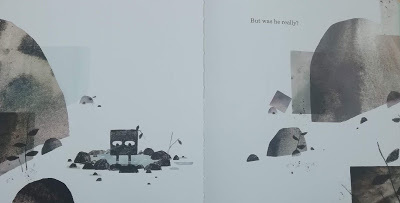

DU IZ TAK? Copyright © 2016 by Carson Ellis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA."Square", by Mac Barnett illustrated by John Klassen--how many children's books do you know that end with a question?

DU IZ TAK? Copyright © 2016 by Carson Ellis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA."Square", by Mac Barnett illustrated by John Klassen--how many children's books do you know that end with a question?

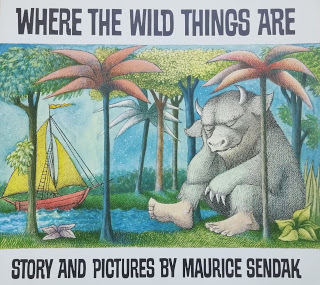

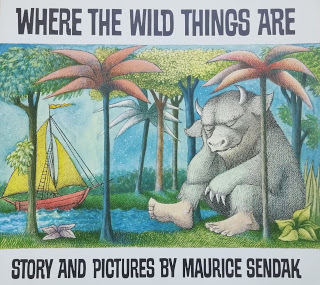

SQUARE. Text copyright © 2018 by Mac Barnett. Illustrations copyright © 2018 by Jon Klassen.Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA."Where the Wild Things Are"- Maurice Sendak is the consummate example of working on a deep, dream-scape level. He allows room for darkness, wildness, doubt, and fear. I think too often we are so afraid of these experiences in ourselves we try to blot them out in children as well, but childhood can be dark and terrifying. I remember how much I appreciated it when adults allowed for this, rather than yelling "THERE IS NOTHING TO BE AFRAID OF!" which of course kids know is bs.

SQUARE. Text copyright © 2018 by Mac Barnett. Illustrations copyright © 2018 by Jon Klassen.Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA."Where the Wild Things Are"- Maurice Sendak is the consummate example of working on a deep, dream-scape level. He allows room for darkness, wildness, doubt, and fear. I think too often we are so afraid of these experiences in ourselves we try to blot them out in children as well, but childhood can be dark and terrifying. I remember how much I appreciated it when adults allowed for this, rather than yelling "THERE IS NOTHING TO BE AFRAID OF!" which of course kids know is bs.

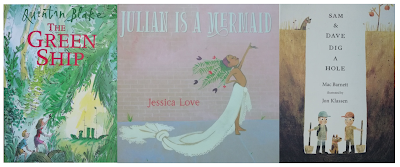

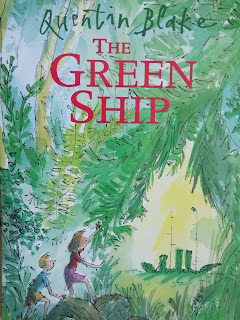

Thank you so much Jessica for your brilliant and thoughtful replies!My own list of favourites is very long, as my groaning bookshelf can testify, but it includes these gems:The Green Ship by Quentin Blake The reader is not given any heavy-handed instruction on the nature of Mrs Tredagar’s grief, but through the green ship’s journey, steering into the eye of a violent storm, and making it safely through, we can experience it.

Thank you so much Jessica for your brilliant and thoughtful replies!My own list of favourites is very long, as my groaning bookshelf can testify, but it includes these gems:The Green Ship by Quentin Blake The reader is not given any heavy-handed instruction on the nature of Mrs Tredagar’s grief, but through the green ship’s journey, steering into the eye of a violent storm, and making it safely through, we can experience it.

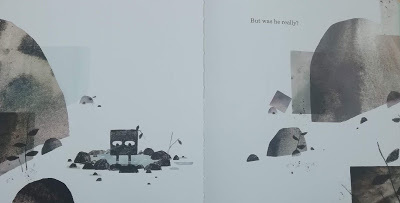

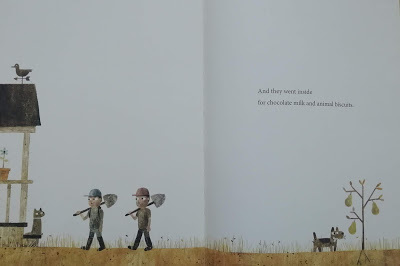

Sam and Dave Dig a Hole by Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen At the end of this story, Sam and Dave fall tumbling through the bottom of the hole they have been digging, and land safely in a place remarkably similar to the one they set off from. But something is not quite right. There is a pear tree where the apple tree was, a different collar on the cat, a different house, and … no hole. These details do not perturb Sam and Dave in any way, but they do seem to bother their dog. What on earth is going on? The back cover shows the original cat, peering down into the hole they dug, possibly trying to figure out the answer to the same question.

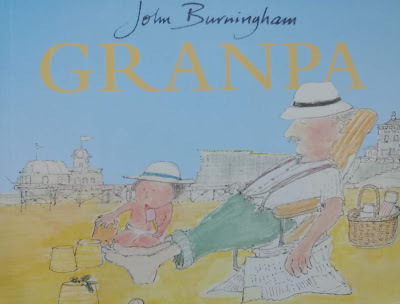

SAM AND DAVE DIG A HOLE. Text copyright © 2014 by Mac Barnett. Illustrations copyright © 2014 by Jon Klassen. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.Grandpa by John BurninghamThe heart-breaking ending leaves us with Grandpa’s empty chair and his granddaughter, curled up, simply looking at it. There is no need for any words to spell out what has happened or how the little girl feels.

SAM AND DAVE DIG A HOLE. Text copyright © 2014 by Mac Barnett. Illustrations copyright © 2014 by Jon Klassen. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.Grandpa by John BurninghamThe heart-breaking ending leaves us with Grandpa’s empty chair and his granddaughter, curled up, simply looking at it. There is no need for any words to spell out what has happened or how the little girl feels.

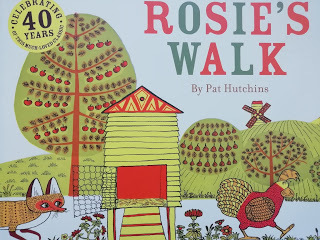

Rosie‘s Walk by Pat Hutchins

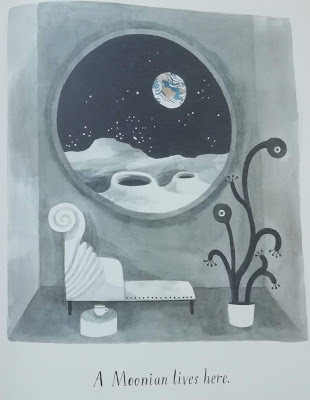

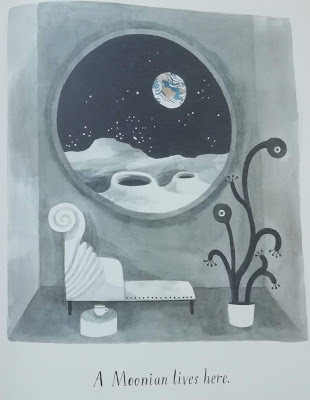

An absolute classic. Is Rosie oblivious to the danger she is in or is she making some very shrewd choices as to where to travel on her journey? Perhaps she has even made a reconnaissance trip? My youngest son and I disagree strongly on this matter. Home by Carson Ellis Carson Ellis poses lots of questions for her reader in her book Home, such as ‘But whose home is this? And what about this? Who in the world lives here? And why?’ On another page she simply says ‘A Moonian lives here’, but whether the Moonian is the owner of the strange looking plant staring glassily back at us, or is the plant itself, is left up to us to decide.

Home by Carson Ellis Carson Ellis poses lots of questions for her reader in her book Home, such as ‘But whose home is this? And what about this? Who in the world lives here? And why?’ On another page she simply says ‘A Moonian lives here’, but whether the Moonian is the owner of the strange looking plant staring glassily back at us, or is the plant itself, is left up to us to decide.

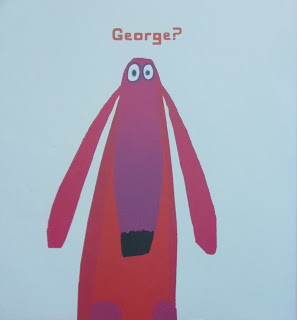

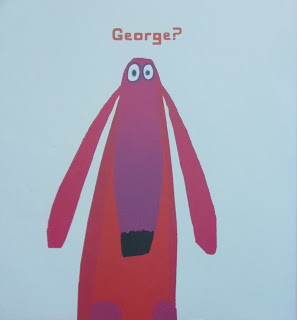

HOME. Copyright © 2015 by Carson Ellis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.Oh No George! by Chris HaughtonAt the end we see George, who always tries so very hard to overcome his urges and ‘be good’, considering the particular tempting delights of a full rubbish bin. The reader is simply asked ‘What will George do?’

HOME. Copyright © 2015 by Carson Ellis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.Oh No George! by Chris HaughtonAt the end we see George, who always tries so very hard to overcome his urges and ‘be good’, considering the particular tempting delights of a full rubbish bin. The reader is simply asked ‘What will George do?’

OH NO, GEORGE!. Copyright © 2012 by Chris Haughton. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA on behalf of Walker Books, London.Please let me know your own favourites in the comments below. I would love to hear from you, and I have a terrible book buying habit that only needs the very slightest encouragement

OH NO, GEORGE!. Copyright © 2012 by Chris Haughton. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA on behalf of Walker Books, London.Please let me know your own favourites in the comments below. I would love to hear from you, and I have a terrible book buying habit that only needs the very slightest encouragement

Susannah has picture books coming out soon with Simon and Schuster (2019) and Frances Lincoln (2020). You can follow Susannah on Twitter and Instagram at @squirrelpocket .

Ursula Le Guin once wrote: ‘The unread story is not a story; it is little black marks on woodpulp. The reader, reading it, makes it live: a live thing, a story.’ This could not be truer than for a picture book, a book for the very young; for readers absolutely brimming with the imagination required to bring a story to life. All my favourite picture book authors take a very wry and playful approach with their readers. They resist the temptation to wrap things up so neatly that there is nothing left for the reader to do. Instead they trust their readers enough to let them take an idea, let their imagination loose and just run with it. As Le Guin put it ‘You can consider the reader, not a helpless victim or a passive consumer, but as an active, worthy collaborator. A colluder, a co-illusionist.’ But it needs careful consideration to make the most of your colluder’s valuable time and attention. Mac Barnett, discussing his stories on the Picture Book Podcast, said of his work “I write a thing that has lots of gaps for [the illustrator] to fill in and then ideally, when the illustrator is done, there are still gaps for the person who is reading the book out loud to fill in and put their own spin on it, and then finally there still should be some spaces for the reader to crawl into and figure those things out.” To listen to the podcast in full click here. This is a topic dear to my heart. I am a new picture book writer and it’s what I’m always striving to achieve my own writing. Needless to say, I have found that it is trickier than it first appears! One recent book that really carries this off is Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love. I absolutely love this book. It is quiet, beautiful, thought-provoking and very moving. It had me sniffing back the tears before I even got it out of the book shop.

Julian, a little boy, watches some glamourous women in mermaid costumes on his bus ride home from the swimming pool, and becomes totally lost in a day dream, imagining himself as a glorious mermaid.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.On the way into their house he declares to his grandmum “Nana, I am also a mermaid.” When she goes off for a bath he looks about the house and bedecks himself in everything he can find to transform himself into a mermaid. What will she make of his flamboyant homemade costume when she returns from her bath?

The text of Julian is very minimal, and the words tell us nothing at all about what the characters of Julian or Nana are thinking or feeling. That is 100% the job of the reader to work out. When his Nana returns from her bath and finds him dressed up in her curtains, plant and makeup, she says nothing but disappears off, leaving us alone with Julian for a very suspense-filled spread. Julian suddenly looks a little vulnerable, a little uncertain, as he peers at himself in the mirror.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.The fact that the readers are invited to fill these spaces themselves, and make their own connections, creates a gentle opportunity for them to experience getting things wrong, and then for them to re-evaluate assumptions that they may have made. When we turned the page my youngest son, quite certain that Julian would be in trouble, jumped back on the sofa, and looked cautiously through his fingers, finally taking his hands away and giving the page a long thoughtful stare. When Nana returns with a necklace to complete his costume, there are no words to tell us about how Julian feels about this, but there don’t need to be – the reader has felt it for themselves.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.The fact that the readers are invited to fill these spaces themselves, and make their own connections, creates a gentle opportunity for them to experience getting things wrong, and then for them to re-evaluate assumptions that they may have made. When we turned the page my youngest son, quite certain that Julian would be in trouble, jumped back on the sofa, and looked cautiously through his fingers, finally taking his hands away and giving the page a long thoughtful stare. When Nana returns with a necklace to complete his costume, there are no words to tell us about how Julian feels about this, but there don’t need to be – the reader has felt it for themselves.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.I recently listened to an interview with Jessica on the Picture Book Podcast. She said that, in creating a book like Julian, she is “Throwing a ball up into the air, into the unknown, and the reader…has the opportunity to catch it….and the magic of catching it can’t happen unless it’s actually been thrown. If someone just stuffs it into your hand, you haven’t caught anything, you’ve been handed something, and that’s not the same thing.” To listen to this interview in full click here.

JULIAN IS A MERMAID. Copyright © 2018 by Jessica Love. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.I recently listened to an interview with Jessica on the Picture Book Podcast. She said that, in creating a book like Julian, she is “Throwing a ball up into the air, into the unknown, and the reader…has the opportunity to catch it….and the magic of catching it can’t happen unless it’s actually been thrown. If someone just stuffs it into your hand, you haven’t caught anything, you’ve been handed something, and that’s not the same thing.” To listen to this interview in full click here.This idea really struck me. I thought yes! This is exactly what I want to do in my own writing! So, to learn more about the subtle art of the throwing, I decided to contact Jessica and ask her about this.

Questions:

Film Director Ernst Lubitsch apparently said: “Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever”. I am completely hooked on trying to achieve this in my picture book stories. What are your thoughts on why this approach makes for such a satisfying an experience for the picture book reader, in particular?This quote is a bullseye. I've worked for the last 13 years as an actor in the theatre--I trained at Juilliard and have been performing in plays ever since. One of the great assets of live performance is the immediate, legible feedback you get from an audience. You know when you have the audience, and you can feel it when you've lost them. Here's what audiences hate: being preached at. Here's what audiences love: making connections on their own. I feel confident saying this is as close to a universal rule as there is in the theatre: show don't tell. But the why of it is what you are asking about, and I've actually spent a lot of time thinking about this and here's what it boils down to: art isn't the object itself. Art isn't the finished book, or painting, or script. That is just the set-up. I think of it this way, art is the thing that happens when an idea travels from the mind of the artist to the mind of the viewer. It's like an electrical impulse leaping from one dendrite to the next. It is the leaping part that is magical. That is the miraculous current that gives the artist and the reader a little zap when they touch it. I think the reason this kind of story is so much more satisfying for the reader, is it allows them to participate, and do their job. I believe artists need to have enough respect for their readers to know when their job is finished, and allow the reader to do theirs. How do you ensure you don’t crowd out the reader’s space or role in your stories, and do you feel it helps that you are both the author and illustrator of the book? That is the question isn't it? How do you actually do it? I think the trick is to think of the reader as your collaborator. It is your job to set them up with the information they need, but connecting the dots is actually their job, not yours. When I first sold Julián is a Mermaid we toyed with the idea of making it entirely wordless. But here's the problem with that: if the reader doesn't have the information from the very beginning that Julián is a boy the reader doesn't have the right coordinates from which to start--they just assume he is a girl and never go on the journey. I think it is always a matter of asking, what is the least amount of information I can give the reader in order for them to make a connection? The bigger the leap, the more satisfying it is for them; the more thrilling the game of catch between you. What books have you loved which leave lots of room for the reader?"Du Iz Tak?", written and illustrated by Carson Ellis. It is a masterpiece and it is in a made-up, bug language! And do kids get bored? No! They lean forward because finally someone has given them something to figure out!

DU IZ TAK? Copyright © 2016 by Carson Ellis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA."Square", by Mac Barnett illustrated by John Klassen--how many children's books do you know that end with a question?

DU IZ TAK? Copyright © 2016 by Carson Ellis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA."Square", by Mac Barnett illustrated by John Klassen--how many children's books do you know that end with a question?