Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 29

November 18, 2018

Life Lessons from Picture Books by Jane Clarke

Last week, Book Trust tweeted

So, inspired by this thread, and with tongue firmly in cheek, here are some life lessons from a few of my favourite old picture books. I’ve confined myself to sausages, elephants and poultry - but feel free to add anything in the comments at the end :-)

1. If you strut about with your beak in the air, you’ll miss a lot of exciting stuff.

2. Never underestimate the power of compromise, especially when arbitrated by a duck.

3. Fake wings may be cool, but they won’t enable you to fly.

4. Be nice to demanding house guests and treat yourself to sausages, chips and ice cream at a cafe after they leave.

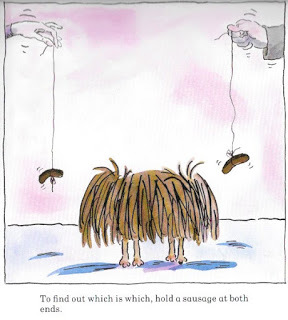

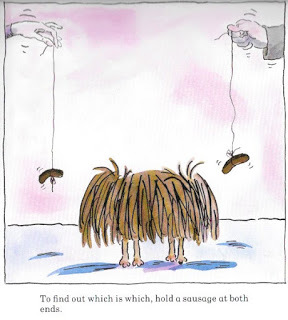

5. It's wise to keep sausages handy in case you need them to determine which end of an Earth Hound has the fangs, and which end has the waggler.

Dr Xargle's book of Earth Hounds by Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross

Dr Xargle's book of Earth Hounds by Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross

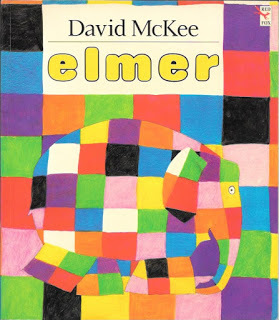

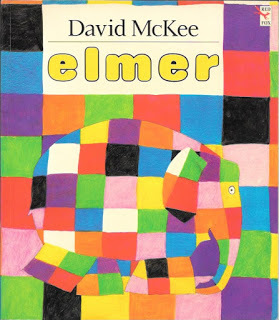

6. Elephants are happiest when they don’t try to hide their true colours.

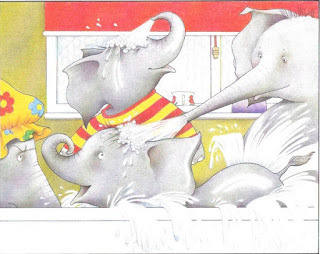

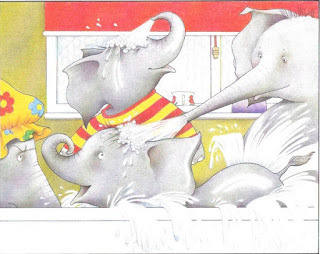

7. If there are four elephants in a bath, only three have fun.

Five Minutes Peace by Jill Murphy

Five Minutes Peace by Jill Murphy

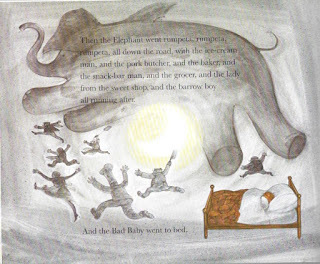

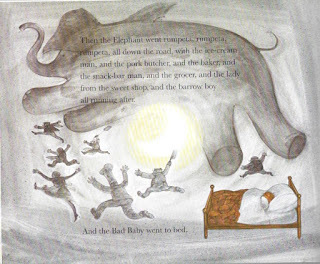

8. If you spend all day going rumpeta, rumpeta, rumpeta all down the road with an elephant, you will need to lie down at the end of it.

The Elephant and the Bad Baby by Elfrida Vipont and Raymond Briggs

The Elephant and the Bad Baby by Elfrida Vipont and Raymond Briggs

There are huge philosophical truths to be extrapolated from picture books and I recognise (somewhat guiltily) that the subject deserves a much more serious post than this. In the meantime, though, I hope you’ll leave a comment to let us know more life lessons (from the silly to the profound) you’ve learned from picture books.

Jane's just finished writing the Dr KittyCat series and is currently working on a third picture book to be illustrated by Britta Teckentrup, and the fourth book in the Al's Awesome Science series illustrated by James Brown.

So, inspired by this thread, and with tongue firmly in cheek, here are some life lessons from a few of my favourite old picture books. I’ve confined myself to sausages, elephants and poultry - but feel free to add anything in the comments at the end :-)

1. If you strut about with your beak in the air, you’ll miss a lot of exciting stuff.

2. Never underestimate the power of compromise, especially when arbitrated by a duck.

3. Fake wings may be cool, but they won’t enable you to fly.

4. Be nice to demanding house guests and treat yourself to sausages, chips and ice cream at a cafe after they leave.

5. It's wise to keep sausages handy in case you need them to determine which end of an Earth Hound has the fangs, and which end has the waggler.

Dr Xargle's book of Earth Hounds by Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross

Dr Xargle's book of Earth Hounds by Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross6. Elephants are happiest when they don’t try to hide their true colours.

7. If there are four elephants in a bath, only three have fun.

Five Minutes Peace by Jill Murphy

Five Minutes Peace by Jill Murphy8. If you spend all day going rumpeta, rumpeta, rumpeta all down the road with an elephant, you will need to lie down at the end of it.

The Elephant and the Bad Baby by Elfrida Vipont and Raymond Briggs

The Elephant and the Bad Baby by Elfrida Vipont and Raymond BriggsThere are huge philosophical truths to be extrapolated from picture books and I recognise (somewhat guiltily) that the subject deserves a much more serious post than this. In the meantime, though, I hope you’ll leave a comment to let us know more life lessons (from the silly to the profound) you’ve learned from picture books.

Jane's just finished writing the Dr KittyCat series and is currently working on a third picture book to be illustrated by Britta Teckentrup, and the fourth book in the Al's Awesome Science series illustrated by James Brown.

Published on November 18, 2018 22:30

November 11, 2018

Illustrating the night in children's picture books • Paeony Lewis

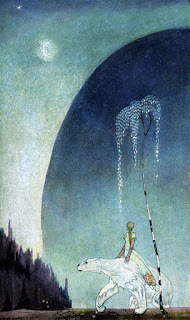

In 1914, Kay Neilson illustrated East of the Sun, West of the MoonAs the nights grow longer and darkness arrives too soon, my thoughts have turned to the illustration of night in children’s picture books. Looking through the books on my shelves, I’ve adored seeing how different illustrators have portrayed the night and moonlight.

In 1914, Kay Neilson illustrated East of the Sun, West of the MoonAs the nights grow longer and darkness arrives too soon, my thoughts have turned to the illustration of night in children’s picture books. Looking through the books on my shelves, I’ve adored seeing how different illustrators have portrayed the night and moonlight.I've discovered that the night can fill the page with grandeur, or be swallowed up by city lights. The moon may glow at the top of the page, or flickering stars are glimpsed through a window. Illustrator style dictates whether the illustrations are simple or detailed, and these images then reflect the mood of the story, which could be fun, cosy, awesome or scary. There is a colour choice to be made: black, grey, purple or blue, but which blue? Will there be moon shadows? Do artificial lights shine through the gloom? So many decisions and I'd love to find out about other books and hear the thoughts of illustrators, but for now, the moon is rising, here comes the night...

This is the only illustration I've seen where the words are inside a white moon.

This is the only illustration I've seen where the words are inside a white moon. The sky is inky black and filled with white stars. The moon's light shines on the swan

and I feel the white house helps hold the composition together.

From The Night Box box by Louise Greig, illustrated by Ashling Lindsay (Egmont, 2017)

I assume this is a linocut, using only black ink?

I assume this is a linocut, using only black ink?There's no moon, although the shape of the hillside is reminiscent of the curve of the moon.

If the stars were taken away we'd still know it was night from the dense un-inked lines that shine like moonlight and the glowing windows of the houses.

From Tales from Outer Suburbia, by Shaun Tan (Templar, 2009)

Here we have no sky, moon or stars. Even the background is white. However, by using dark shadows on the sleepers and their meagre belongings we know it is dark, wherever they are sleeping.

Here we have no sky, moon or stars. Even the background is white. However, by using dark shadows on the sleepers and their meagre belongings we know it is dark, wherever they are sleeping.From My Name is Not Refugee by Kate Milner (The Bucket List, 2017)

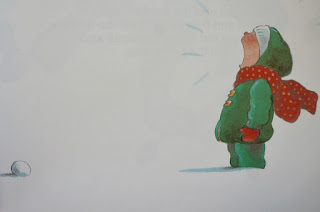

Snow and moonlight seem popular in children's picture books, and I can appreciate why - the whites and blues almost sing together.

My box of crayons no longer feels childish if this is what can be done with a couple of blue crayons and brilliant white paper (and a lot of skill!).

My box of crayons no longer feels childish if this is what can be done with a couple of blue crayons and brilliant white paper (and a lot of skill!).From Shackleton's Journey by William Gill (Flying Eye Books, 2014)

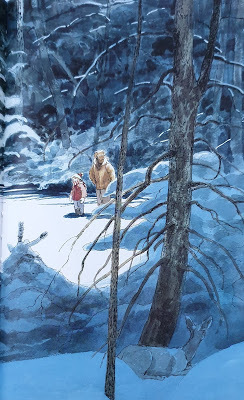

This time it's watercolour. The silent shadows of the forest contrast with the moonlight bouncing off the snow.

This time it's watercolour. The silent shadows of the forest contrast with the moonlight bouncing off the snow.From Owl Moon by Jane Yolen, illustrated by John Schoenherr (Philomet Books, 1987)

A different style of gentle watercolour. The cool colours of the snowy night contrast subtly with the warm colours of the bedroom. The blue of the night sky links with inside of the house through the poster on the wall.

A different style of gentle watercolour. The cool colours of the snowy night contrast subtly with the warm colours of the bedroom. The blue of the night sky links with inside of the house through the poster on the wall.From Crinkle, Crackle, Crack: It's Spring! by Marion Dane Bauer, illustrated by John Shelley (Holiday House, 2015)

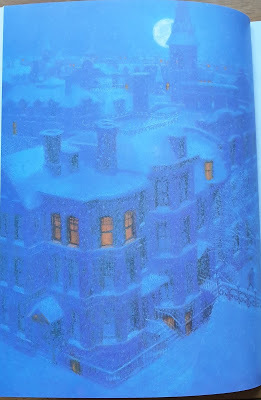

Here, falling snow produces a haze of night blue and snow white, broken through by the complementary orange of the indoor light.

Here, falling snow produces a haze of night blue and snow white, broken through by the complementary orange of the indoor light.From The Night Before Christmas by Clement C Moore, illustrated by Christian Birmingham (Harper Collins, 2007)

A very different style, this time using an intriguing diorama. The night sky is grey, like the mood of poor, patient Goliath.

A very different style, this time using an intriguing diorama. The night sky is grey, like the mood of poor, patient Goliath. From Waiting for Goliath by Antje Damm (Gecko Press, 2017 translated from German)

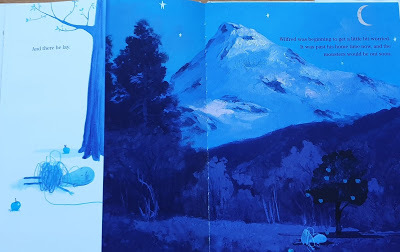

Interesting how the blue totally changes the illustration from day to night.

Interesting how the blue totally changes the illustration from day to night.From This Moose Belongs to Me by Oliver Jeffers (Harper Collins 2012)

The night sky doesn't have to be black or blue; purple works well too and fits the mysterious theme.

The night sky doesn't have to be black or blue; purple works well too and fits the mysterious theme.From Leon and the Place Between by Angela McAllister and illustrated by Grahame Baker-Smith (Templar, 2009)

Here's another purple night sky, this time in a simple graphic style, that's still effective.

Here's another purple night sky, this time in a simple graphic style, that's still effective.From Good Little Wolf by Nadia Shireen (Jonathan Cape 2011)Many illustrators have fun with artificial light at night, and where there is ambiguity as to whether it's night or day, the white, yellow or orange artificial light confirms the darkness.

There's very little colour here, but we know it's night from bright yellow windows. We notice the lion because he is surrounded by white. This lion is also yellow, but it's a different yellow so we know he's not a strange looking lamp!

There's very little colour here, but we know it's night from bright yellow windows. We notice the lion because he is surrounded by white. This lion is also yellow, but it's a different yellow so we know he's not a strange looking lamp!From How to Hide a Lion by Helen Stephens (Alison Green Books, 2012)

The bike lamp accentuates the darkness and is the same blue as the daytime sky on the opposite page.

The bike lamp accentuates the darkness and is the same blue as the daytime sky on the opposite page.

From The Journey by Franseca Sanna (Flying Eye Books, 2016)

The yellow of the inside light transforms the illustration into the night.

The yellow of the inside light transforms the illustration into the night.From The Three Robbers by Tomi Ungerer (Phaidon Press, 2009)

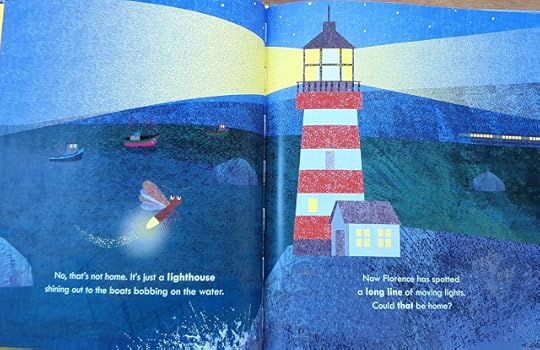

The night is emphasised by the bright artificial yellow light from a house, boats, train and lighthouse. And there's natural yellow light too, from a firefly!

The night is emphasised by the bright artificial yellow light from a house, boats, train and lighthouse. And there's natural yellow light too, from a firefly!From Firefly Home by Jane Clarke and illustrated by Brita Teckentrup (Nosy Crow 2018)

The bright artificial lights bring out the gaiety of the ship at night.

The bright artificial lights bring out the gaiety of the ship at night.Two illustrations from The Real Boat by Marina Aromshtam and illustrated by Victoria Semykina (Templar 2017)

Two night illustrations from the same book. Both use window light, but when thee mood changes the blue of the dark night also changes. In the first the cat is having fun, but not in the second where the darkness has turned grey.

Two night illustrations from the same book. Both use window light, but when thee mood changes the blue of the dark night also changes. In the first the cat is having fun, but not in the second where the darkness has turned grey.From Mr Pusskins by Sam Lloyd (Orchard Books, 2007)

Another two illustrations. At the top are layers of blue with the blobs of light of the town similar to stars (or are they like holes, representing the mining beneath?). In the second illustration from the book the men are in the mines and the movement of the paint adds to the feeling of the heavy ground pressing down on them.

Another two illustrations. At the top are layers of blue with the blobs of light of the town similar to stars (or are they like holes, representing the mining beneath?). In the second illustration from the book the men are in the mines and the movement of the paint adds to the feeling of the heavy ground pressing down on them. From Town is by the Sea by Joanne Schwartz and illustrated by Sydney Smith (Walker Books 2017)

Another symphony of blue layers (watercolour?). The shade of blue is cool, like the night.

Another symphony of blue layers (watercolour?). The shade of blue is cool, like the night.From There is a Tribe of Kids by Lane Smith (Two Hoots, 2016)

This time the moonlight is grey because of the fog. I've included the words on the left because the author likened the foggy moonlight to everything seeming dusted with flour.

This time the moonlight is grey because of the fog. I've included the words on the left because the author likened the foggy moonlight to everything seeming dusted with flour. From Fog Island by Tomi Ungerer (Phaidon Press reprint, 2013)

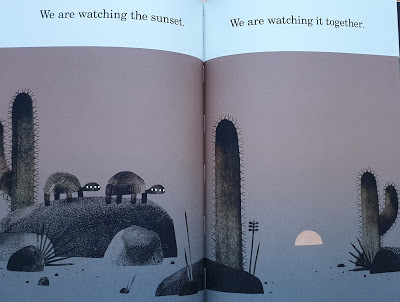

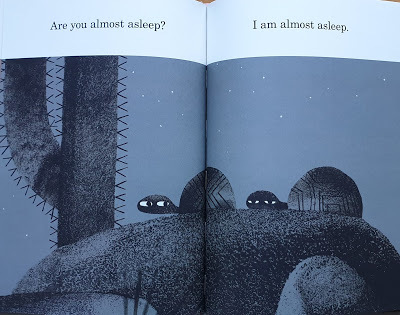

For a grey night, you don't get much greyer than this book. Even the sunset is muted, but so are the subdued lives of the creatures and it adds to the atmosphere of fun boredom.

For a grey night, you don't get much greyer than this book. Even the sunset is muted, but so are the subdued lives of the creatures and it adds to the atmosphere of fun boredom.From We Found a Hat by Jon Klassen (Walker Books, 2016)

From a muted desert to New York City at night in shades of blue. It's not a neon explosion because our eyes are meant to focus on the people watching the screen ahead that's framed by an unusually starry night . Even the cabs don't have light from their headlamps as that would detract from the focus.

From a muted desert to New York City at night in shades of blue. It's not a neon explosion because our eyes are meant to focus on the people watching the screen ahead that's framed by an unusually starry night . Even the cabs don't have light from their headlamps as that would detract from the focus.From Curiosity: The Story of a Mars Rover by Markus Motum (Walker Studio, 2017)

Here's another example of a deliberate downplay of light. The room and lamp are muted to allow the moon outside the window to shine brighter than everything else.

Here's another example of a deliberate downplay of light. The room and lamp are muted to allow the moon outside the window to shine brighter than everything else.From Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown, illustrated by Clement Hurd (1947)

Time for a bit of diorama drama. Lightning looks good at night, especially above a tower!

Time for a bit of diorama drama. Lightning looks good at night, especially above a tower!From The Princess and the Pea by Lauren Child and Polly Borland (Puffin, 2006)

Finally, Moon, illustrated by Britta Teckentrup (Little Tiger Kids, 2017), displays the cut-out shapes of the phases of the moon as you progress through the book.There are many, many more picture books that include the night, but I suspect I've already included too many! Anyway, I hope the night illustrations haven't made you too sleepy. I adore looking at the differences in method and style and wonder if Prussian Blue is the best cool blue for the night? All thoughts appreciated, thank you!

Finally, Moon, illustrated by Britta Teckentrup (Little Tiger Kids, 2017), displays the cut-out shapes of the phases of the moon as you progress through the book.There are many, many more picture books that include the night, but I suspect I've already included too many! Anyway, I hope the night illustrations haven't made you too sleepy. I adore looking at the differences in method and style and wonder if Prussian Blue is the best cool blue for the night? All thoughts appreciated, thank you!Paeony Lewis, children's author

www.paeonylewis.com

List of my blog posts at the Picture Book Den.

Published on November 11, 2018 18:47

November 4, 2018

Looking into the eyes of picture book characters.

Garry Parsons takes a closer look at how illustrators render the eyes of their characters.

Julia Sarda from The Liszts written by Kyo Maclear.

Julia Sarda from The Liszts written by Kyo Maclear.

Recent conversations about characters' eyes have left me in a spin. It’s clear that some people have a preference for how characters' eyes are rendered - and why wouldn’t they? You may have a preference yourself. You may prefer just dots, or you might prefer ovals with dots.

This Is the Way to the Moon by M.Sasek

This Is the Way to the Moon by M.Sasek

There are dots, then dots within circles, then circles with dashes, then ovals with dots, and ovals with dashes, then almonds with lids and lids with lashes and lashes with dots and a lot more variations too tricky to describe. But the closer I looked the more compelling it became.

But it is not only individuals who have preferences.

Gentleman Jim by Raymond Briggs

Gentleman Jim by Raymond Briggs

Apparently, book markets across the world have differing collective preferences on how eyes should be rendered, some favouring dots, others preferring dots within circles, for example, which may leave you with a conundrum if you aim to sell your books in more than one country.

The Journey by Francesca Sanna

The Journey by Francesca Sanna

We all know that the co-edition market is important for book sales and book longevity. And what a joy it is to receive copies of your work translated into Chinese, Estonian or Swedish! But does the shape of the eyes have an impact on what sells abroad?

Emma Chichester Clark from Have You Ever Ever Ever? written by Colin McNaughton

Emma Chichester Clark from Have You Ever Ever Ever? written by Colin McNaughton

Supposing we were to jot down a list of criteria for a picture book to generate enough interest to secure those vital sales abroad, how far down the list would the shape of the character’s eyes be? And if individual countries, or even continents, do have a preference, then couldn’t the sales team just tot up the figures and request that the illustrator give the character the eyes appropriate for the market they want to sell to? “Is that a half circle and a dash or would that be a dot with a lash for Scandinavia?”

“No, wait - it’s dots for Japan and circles for South America, please!”

Angela Barrett from Anne Frank written by Josephine Poole

Angela Barrett from Anne Frank written by Josephine Poole

It seems that it’s not quite that simple to appeal to everyone, sell to the whole world and cover all the bases, but the conversations I was having seemed to imply that there might just be a happy medium to accommodate a healthy majority (if not everyone) somewhere in between a half circle and a dash perhaps, something that could satisfy almost every cultural requirement. Can you supply the holy grail of character eyes that appeals to pretty much everyone, please, Illustrator?

Garry Parsons from Hey! What's That Nasty Whiff? written by Julia Jarmen

Garry Parsons from Hey! What's That Nasty Whiff? written by Julia Jarmen

So exactly what shaped eyes should you do? And does it really matter anyway? Surely the story and the overall feel of the book is way more important than such a small detail. After all, we are talking about something as simple as a dot or a dash.

I’m back in a spin.

The Cat in the Hat by Dr Seuss

The Cat in the Hat by Dr Seuss

Reaching for the bookshelves, I browse through the variety of eye shapes to look at techniques illustrators have employed at different times to convey the eyes of their characters. From the 1960s to the present day, the spectrum goes from the realistic to the wildly bizarre, but mostly, in essence, they are all variations on dots or dots within circles to some degree.

David Roberts from Tyrannosaurus Drip written by Julia Donaldson

David Roberts from Tyrannosaurus Drip written by Julia Donaldson

There are now lots of picture books spread all over the desk and floor. Within this pile of books I noted that some illustrators alternate between dots and circles from one book to another, not sticking to one method throughout their career, but moving back and forth and chopping and changing technique. In one book a character has dots, in the next the eyes have circles, and then in another book by the same hand we are back to dots again. I even surprised myself, when I noticed how my own characters have switched and swapped between dots, circles and half circles over time, too.

Other Goose by J.Otto Seibold

Other Goose by J.Otto Seibold

There are illustrators who use the same eye shape throughout a whole book for multiple characters, and some who vary this. In some books animal characters are adorned with the same eyes as the people they converse with, and in others they are not. Sometimes animals and make-believe characters are given distinctly different eyes to their human counterparts, and then in some, human characters have dots and their human companions have circles on the same page. Some characters appear to flick between the two (in the blink of an eye) with the eyes changing from dots to full round circles to express, shock, horror or delight and then returning to the mildness of dots again.

Bruce Ingman from The Runaway Dinner written by Allan Ahlberg

Bruce Ingman from The Runaway Dinner written by Allan Ahlberg

I hoped I might identify fashions or trends for eye shapes within this pile of books in front of me, but there were always contradictions and alternatives. Obviously my quick study has been confined to just one collection of books. I’ve not explored the archives of the British Library or studied the bookshelves of other countries, but one thing that is clear is that these eyes are not just dots, circles and dashes, seen in isolation. They have to be viewed as a whole. The rendering of the eyes is embedded in the nature of the character and within the style of the illustrator. To separate the eyes out from the rest of the whole now seems like a ludicrous notion. Would we then have to have a similar conversation about noses? A tick or a curve, a blob or a point...?

Ingrid Godon from Hello, Sailor written by Andre Sollie

Ingrid Godon from Hello, Sailor written by Andre Sollie

So, where to leave this ramble about eyes, be they dots or be they circles? Back in the place where picture books belong, I think. On a shelf where there are no rules and where the impossible can become possible through words and pictures combined. And where no one, it seems (even though we may try) can predict the ingredients of a worldwide bestseller.

Sara Ogilvie from Detective Dog written by Julia Donaldson

Sara Ogilvie from Detective Dog written by Julia Donaldson

So, if you find yourself feeling conflicted over a detail like dots or circles, maybe it’s best to forget whom you are trying to please and just let your characters decide for themselves.

We're going to end on a quiz! Can you identify who the illustrator is by the eyes alone? Answers will appear in the comments section on Tuesday evening. So there's no peeking!

Garry Parsons is a children's book illustrator.

See more of Garry's illustration here.

@icandrawdinos on Instagram & Twitter

***

Julia Sarda from The Liszts written by Kyo Maclear.

Julia Sarda from The Liszts written by Kyo Maclear.Recent conversations about characters' eyes have left me in a spin. It’s clear that some people have a preference for how characters' eyes are rendered - and why wouldn’t they? You may have a preference yourself. You may prefer just dots, or you might prefer ovals with dots.

This Is the Way to the Moon by M.Sasek

This Is the Way to the Moon by M.SasekThere are dots, then dots within circles, then circles with dashes, then ovals with dots, and ovals with dashes, then almonds with lids and lids with lashes and lashes with dots and a lot more variations too tricky to describe. But the closer I looked the more compelling it became.

But it is not only individuals who have preferences.

Gentleman Jim by Raymond Briggs

Gentleman Jim by Raymond BriggsApparently, book markets across the world have differing collective preferences on how eyes should be rendered, some favouring dots, others preferring dots within circles, for example, which may leave you with a conundrum if you aim to sell your books in more than one country.

The Journey by Francesca Sanna

The Journey by Francesca SannaWe all know that the co-edition market is important for book sales and book longevity. And what a joy it is to receive copies of your work translated into Chinese, Estonian or Swedish! But does the shape of the eyes have an impact on what sells abroad?

Emma Chichester Clark from Have You Ever Ever Ever? written by Colin McNaughton

Emma Chichester Clark from Have You Ever Ever Ever? written by Colin McNaughtonSupposing we were to jot down a list of criteria for a picture book to generate enough interest to secure those vital sales abroad, how far down the list would the shape of the character’s eyes be? And if individual countries, or even continents, do have a preference, then couldn’t the sales team just tot up the figures and request that the illustrator give the character the eyes appropriate for the market they want to sell to? “Is that a half circle and a dash or would that be a dot with a lash for Scandinavia?”

“No, wait - it’s dots for Japan and circles for South America, please!”

Angela Barrett from Anne Frank written by Josephine Poole

Angela Barrett from Anne Frank written by Josephine PooleIt seems that it’s not quite that simple to appeal to everyone, sell to the whole world and cover all the bases, but the conversations I was having seemed to imply that there might just be a happy medium to accommodate a healthy majority (if not everyone) somewhere in between a half circle and a dash perhaps, something that could satisfy almost every cultural requirement. Can you supply the holy grail of character eyes that appeals to pretty much everyone, please, Illustrator?

Garry Parsons from Hey! What's That Nasty Whiff? written by Julia Jarmen

Garry Parsons from Hey! What's That Nasty Whiff? written by Julia JarmenSo exactly what shaped eyes should you do? And does it really matter anyway? Surely the story and the overall feel of the book is way more important than such a small detail. After all, we are talking about something as simple as a dot or a dash.

I’m back in a spin.

The Cat in the Hat by Dr Seuss

The Cat in the Hat by Dr SeussReaching for the bookshelves, I browse through the variety of eye shapes to look at techniques illustrators have employed at different times to convey the eyes of their characters. From the 1960s to the present day, the spectrum goes from the realistic to the wildly bizarre, but mostly, in essence, they are all variations on dots or dots within circles to some degree.

David Roberts from Tyrannosaurus Drip written by Julia Donaldson

David Roberts from Tyrannosaurus Drip written by Julia DonaldsonThere are now lots of picture books spread all over the desk and floor. Within this pile of books I noted that some illustrators alternate between dots and circles from one book to another, not sticking to one method throughout their career, but moving back and forth and chopping and changing technique. In one book a character has dots, in the next the eyes have circles, and then in another book by the same hand we are back to dots again. I even surprised myself, when I noticed how my own characters have switched and swapped between dots, circles and half circles over time, too.

Other Goose by J.Otto Seibold

Other Goose by J.Otto Seibold There are illustrators who use the same eye shape throughout a whole book for multiple characters, and some who vary this. In some books animal characters are adorned with the same eyes as the people they converse with, and in others they are not. Sometimes animals and make-believe characters are given distinctly different eyes to their human counterparts, and then in some, human characters have dots and their human companions have circles on the same page. Some characters appear to flick between the two (in the blink of an eye) with the eyes changing from dots to full round circles to express, shock, horror or delight and then returning to the mildness of dots again.

Bruce Ingman from The Runaway Dinner written by Allan Ahlberg

Bruce Ingman from The Runaway Dinner written by Allan AhlbergI hoped I might identify fashions or trends for eye shapes within this pile of books in front of me, but there were always contradictions and alternatives. Obviously my quick study has been confined to just one collection of books. I’ve not explored the archives of the British Library or studied the bookshelves of other countries, but one thing that is clear is that these eyes are not just dots, circles and dashes, seen in isolation. They have to be viewed as a whole. The rendering of the eyes is embedded in the nature of the character and within the style of the illustrator. To separate the eyes out from the rest of the whole now seems like a ludicrous notion. Would we then have to have a similar conversation about noses? A tick or a curve, a blob or a point...?

Ingrid Godon from Hello, Sailor written by Andre Sollie

Ingrid Godon from Hello, Sailor written by Andre SollieSo, where to leave this ramble about eyes, be they dots or be they circles? Back in the place where picture books belong, I think. On a shelf where there are no rules and where the impossible can become possible through words and pictures combined. And where no one, it seems (even though we may try) can predict the ingredients of a worldwide bestseller.

Sara Ogilvie from Detective Dog written by Julia Donaldson

Sara Ogilvie from Detective Dog written by Julia DonaldsonSo, if you find yourself feeling conflicted over a detail like dots or circles, maybe it’s best to forget whom you are trying to please and just let your characters decide for themselves.

We're going to end on a quiz! Can you identify who the illustrator is by the eyes alone? Answers will appear in the comments section on Tuesday evening. So there's no peeking!

Garry Parsons is a children's book illustrator.

See more of Garry's illustration here.

@icandrawdinos on Instagram & Twitter

***

Published on November 04, 2018 16:04

October 29, 2018

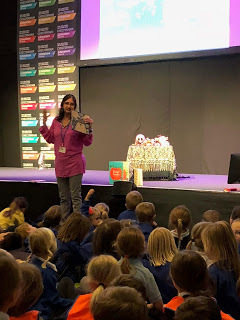

'The Less Said The Better' by Lou Carter

This week, author, Lou Carter, has taken the Picture Book Den reins and is talking to us about minimal word count picture books. Lou is the author of 'Pirate Stew', illustrated by Nikki Dyson, and also 'There Is No Dragon In This Story', illustrated by Deborah Allwright, which has now been translated into a phenomenal 18 languages!! 'Oscar The Hungry Unicorn' is Lou and Nikki's next offering and we're lucky to have a sneak peek of it today! Thank you, Lou.

'When my agent suggested that I try to write a minimal word count picture book I immediately thought, no way. Surely that would be territory reserved only for author-illustrators. And would a publisher not think I was just downright lazy? But then I got to work…

When I run picture book writing workshops in schools, one of the most important things I try to get across is that you must let the pictures tell some of the story. This sounds obvious I know, but I think it is all too easy to write too much in the text and then have an illustration showing the same information.

For example;TEXT: One bright, sunny morning Rabbit put on her favourite red hat and hopped off to the Carrot Cafe for breakfast. ILLUSTRATION: A rabbit in a red hat hopping towards Carrot Cafe, the sun shining in the sky.

In this example the text tells you everything you need to know without the picture. Similarly the picture tells you everything you need to know without the text. You would not glean any extra information from either the words or the illustrations. Ideally, with this illustration the only text needed would be something that Rabbit thinks or feels i.e. something we cannot SEE.For example;TEXT: Rabbit was hungry! orTEXT: Rabbit couldn't wait for breakfast!

This skill is important for any length picture book but is essential for minimal word texts.

In my opinion, Jon Klassen is the king of this genre, my favourites being This Is Not My Hat and I Want My Hat Back. In both stories the illustrations and text come together perfectly to tell simple yet highly amusing stories.

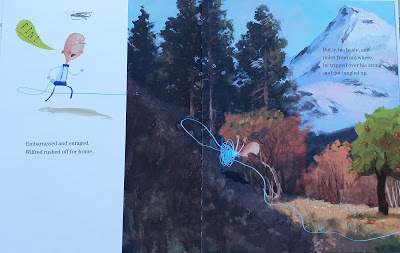

So when I came to write Oscar The Hungry Unicorn I tried to focus on these key principles;1) story simplicity(The Oscar storyline is that of a unicorn who eats everything, including his stable, and simply tries to find somewhere else to live.)2) punchline pictures (where the text will set up the joke for the illustration to answer)For instance, on this page neither the text nor the illustration would be complete on their own. But together the text sets up the joke by explaining that the ship has a hole in it and the picture provides the punchline - Oscar has bitten the hole in it.

My first drafts of Oscar were in excess of 400 words (around half that of my other picture books.) And although I was pleased with the early versions I felt they could be funnier still.

It was my daughter in the end who suggested that I “cut way more words”. Once I halved the word count again to just under 200 words the story suddenly felt right and packed more of a punch.

Less is more, as they say.'

'Oscar the Hungry Unicorn' by Lou Carter and Nikki Dyson is out now and can be found in all good book shops and online!

'When my agent suggested that I try to write a minimal word count picture book I immediately thought, no way. Surely that would be territory reserved only for author-illustrators. And would a publisher not think I was just downright lazy? But then I got to work…

When I run picture book writing workshops in schools, one of the most important things I try to get across is that you must let the pictures tell some of the story. This sounds obvious I know, but I think it is all too easy to write too much in the text and then have an illustration showing the same information.

For example;TEXT: One bright, sunny morning Rabbit put on her favourite red hat and hopped off to the Carrot Cafe for breakfast. ILLUSTRATION: A rabbit in a red hat hopping towards Carrot Cafe, the sun shining in the sky.

In this example the text tells you everything you need to know without the picture. Similarly the picture tells you everything you need to know without the text. You would not glean any extra information from either the words or the illustrations. Ideally, with this illustration the only text needed would be something that Rabbit thinks or feels i.e. something we cannot SEE.For example;TEXT: Rabbit was hungry! orTEXT: Rabbit couldn't wait for breakfast!

This skill is important for any length picture book but is essential for minimal word texts.

In my opinion, Jon Klassen is the king of this genre, my favourites being This Is Not My Hat and I Want My Hat Back. In both stories the illustrations and text come together perfectly to tell simple yet highly amusing stories.

So when I came to write Oscar The Hungry Unicorn I tried to focus on these key principles;1) story simplicity(The Oscar storyline is that of a unicorn who eats everything, including his stable, and simply tries to find somewhere else to live.)2) punchline pictures (where the text will set up the joke for the illustration to answer)For instance, on this page neither the text nor the illustration would be complete on their own. But together the text sets up the joke by explaining that the ship has a hole in it and the picture provides the punchline - Oscar has bitten the hole in it.

My first drafts of Oscar were in excess of 400 words (around half that of my other picture books.) And although I was pleased with the early versions I felt they could be funnier still.

It was my daughter in the end who suggested that I “cut way more words”. Once I halved the word count again to just under 200 words the story suddenly felt right and packed more of a punch.

Less is more, as they say.'

'Oscar the Hungry Unicorn' by Lou Carter and Nikki Dyson is out now and can be found in all good book shops and online!

Published on October 29, 2018 00:30

October 21, 2018

Finding and Finessing a Folktale by Chitra Soundar

I’ve started teaching a course on picture books and as I break down the basics to other writers, I realised that I’m articulating my own understanding. My writing, especially in the medium of picture books, comes from my lifelong love of picture books, from this moment, I was handed this book when I was 7.

I read picture books and comics as much as I can, growing up, and when I started writing way back in 2003. I still read way too many picture books and often most ideas present themselves to me in 12 spreads.

Along with this love for picture books, I’m also a storyteller. I think I told stories even when I was four and the love for oral storytelling never really left me even when I was working in the corporate world.

Here is my process of how I search, find and finesse a folktale for a modern audience.

Finding a story : I usually choose a story from my own culture or a trickster tale. I read quite a few stories from collections I’ve accumulated over the years to identify which story connects with me. I need to get the “theme” of the story and I want to be able to see the story in scenes, rather than a quick joke.

If I do choose a story that is not from a culture I’m familiar with, I would check if there are enough independent “first-hand” sources I can rely on for accuracy of representation. I’d want to know if this story has been retold or adapted or written about by people who are native to that culture and what do they think of it. Often folktales have hidden allegory and meaning that will work at a different level than the “story” itself and I might inadvertently cause hurt or offence to people by re-telling this story.

Check out a research paper on this here.

My search takes me into libraries, Internet archives of ancient texts and research notes because modern retellings or “collections” might be derivative and I would try and find as many “native” sources I can.

Evaluating for a Modern Audience: There are many funny stories in Aesop fables or Panchatantra or our epics that might not be suitable for today’s children. Many of these stories are true to their time and geography. So a story about “girls knowing their place” or “a cruel stepmother” or "old women are witches" are not only inappropriate but also harmful for today’s child.

So I read and understand the underlying concepts of each of these folktales and think about whether the protagonist and the events of the story are telling a tale suitable for today and beyond. While we can’t go back and erase our past, or justify some of the notions, the least we could do is not to propagate unhelpful stereotypes – whether it’s about gender, age, sexual orientation or cultures.

Read about some of the stereotypes challenged in last year's IBBY conference.

Adapting the Story : Now comes the techniques of writing a picture book. I need to know enough about the story to be able to adapt it. As I said before, I would try and find as many variants of the story I can. I’ll try and find archives with original text or translations.

Having absorbed the story, these are my techniques to adapt the story:

a) Understanding its spine – what’s the story really about? What’s the message and essence of the story? In this, oral storytelling and adapting have the same goal. I normally break down a story into 10 simple scenes or sentences. Or 5 things I need to remember and then distill it into “a message”. Once I know this, I can then adapt the story and still be able to keep the essence.

b) Who are the characters? Especially when I’m working with trickster tales, the characters in the story are crucial for the logic of the story to work. Like Stork and the Fox in Aesop Fables, or the Crocodile and the Monkey in Panchatantra. The characteristics and the “character” – who is evil, who is tricking whom, who is symbolised as clever – all of that will need to be worked out. Often keeping the same characters as per the original story is sufficient. Sometimes I’d want to change it. When changing the characters, I’ve to make sure that the “symbolic” nature of their characters will still work.

It’s important to know the cultural archetypes here. In some cultures some animals and birds are clever / evil / cunning and if I need to credit the culture, then using an alternate one or the wrong one will take away the authenticity.

c) What’s the punch line and how do I get there? I’ll need to understand what are the relevant scenes that need to have happened for the punch line to work. But at the same time, we need 12 scenes in the picture book that are different from each other.

Here’s where research pays off – knowing the geography of the story, knowing the other characters will help.

Also as a storyteller, the embellishing happens here – adding more scenes to show the allegory or the true nature of the characters will help a child reader understand the punch line better.

d) Word count and other practical considerations: Most modern picture books are under 400 words with exceptions of course. I need to be able to tell the 12 scenes with enough happening between the scenes and still keeping the word count down.

The other thing I’ll think about is viewpoint – which character is telling the story? Am I going to use the voice of a storyteller? Is my language going to be modern or folktale-ish? Is this story going to be billed as a re-telling or an adaptation?

e) Adapting vs Retelling – Whether it’s the Gruffalo or the True story of the Three Little Pigs, or my own A Jar of Picklesand a Pinch of Justice or Pattan’s Pumpkin – the story can be hidden under a completely new setting, cast of characters and a modern retelling.

Whether or not the reader knows the underlying story, it will still be fun for them. Of course, in all of my adaptations, I’ve made it clear that I’ve adapted traditional tales. Sometimes a story is in folk-legend widely that you might not need to mention it.

For those who are starting out to write picture books and grappling with “where do I get ideas?”, adapting folktales can be a wonderful exercise in research, structure and plotting. Folk tales have plots that have worked for hundreds of years and can be useful in showing us how to construct a regaling tale.

If you enjoyed reading this post, do share your favourite folktale adaptations in the comments.

Chitra Soundar is the author of many picture books and retellings. Her latest book is an original story of two polar bear cubs discovering the world. Find out more about You’re Snug with Me, illustrated by Poonam Mistry and published by Lantana Publishing here.

Chitra Soundar is the author of many picture books and retellings. Her latest book is an original story of two polar bear cubs discovering the world. Find out more about You’re Snug with Me, illustrated by Poonam Mistry and published by Lantana Publishing here.

Published on October 21, 2018 23:00

October 15, 2018

Your Procrastination Shield –What is it actually protecting you from, and how do you lay it down so you can get on with your writing? by Juliet Clare Bell.

Do you ever put off writing? Can you find really plausible excuses not to sit down and get on with it? I suspect if we pooled all our excuses for putting off writing (and, of course, many other things) there’d be a lot of overlap, but I also suspect there are some excuses that are more specific and personal to each of us, the ones that we’ve managed to craft carefully, often unconsciously, to fool ourselves as best we can… After all, say Jane Burka and Lenora Yuen (authors of the book, below), “it’s yourprocrastination” and we can each find our own special ways of making those excuses, the ones that will work best on the person it needs to work on: us.

I was always a terrible procrastinator, but I’ve actually found a book that has had quite a remarkable impact on me and I feel that if it can work for me, then there may be hope for other procrastinating writers out there, too. And here’s the book:

Procrastination. Why You Do It, What To Do About It NOW by Jane Buerka and Leonora Yuen (2008).

It’s not a new book (it was fully revised and updated for its 25th anniversary –ten years ago, but it’s new to me and I have a feeling that it would help a LOT of writers (and everyone else). So I’m going to write about it and describe a week-long writing experiment I did based on the book, and how I wrote more in that week than I had written in the three months before it, in the hopes that it might be of some use to other writers.

I’ve known for a long time that I’ve procrastinated and I’ve kind of described myself as badly organised and thinking I need to get better at time management, and I’ve enjoyed reading books about managing time more effectively (probably as a way of procrastinating and not doing what I should have been doing). I guess I’ve not felt too bad seeing myself as someone who isn’t great with time management… but this book doesn’t see procrastination as a problem with time management as much as with emotion management...

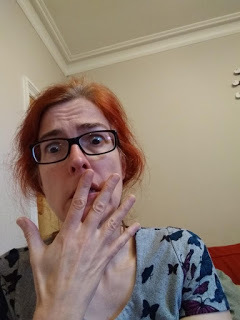

(Me being fearful)

And that is harder –for me, at least (though I suspect, many of us)- to feel ok about. As a writer (and former psychologist!), I like to see myself as being pretty self-aware, so this book was challenging for me, and it may be challenging for you, too, should you choose to read it, but I think it’s a challenge well worth undertaking.Jane Burka and Lenora Yuen talk about procrastination as a shield:

“In one sense, procrastination has served you well. It has protected you from what may be some unpleasant realisations about yourself. It has helped you to avoid uncomfortable and perhaps frightening feelings. It has provided you with a convenient excuse for not taking action in a direction that is upsetting in some way, ” (p137).

“For procrastinators, avoidance is the king of defences, because when you avoid the task, you are also avoiding the many thoughts, feelings, and memories associated with it ,” (p93).

So this book encourages you to be honest with yourself about things that you may not have thought about for a long time in order to recognise what is happening to you when you reach what they call a ‘choice point’ –the point at which you are coming up with excuses not to sit down and write (in our case), where you need to decide whether to go with the excuse, or carry on with the activity (writing) anyway.At least, then, if you still conclude “…therefore, I’ll do it later”, you’re being more consciously aware of your procrastination. But once you’re aware, you may well choose to over-ride the desire to put it off, and do it anyway.

The authors talk about physiological fear responses, and how for example, if you’re touched unexpectedly, that fear response (and the body’s reaction) will occur before you even feel the touch.

Goosebumps / goose pimples

And they relate it back to procrastinating:

"By the time you think about doing a task you’ve been avoiding…, your body has already reacted with fear. No wonder you put it off,” (p92).

And so the book encourages us to identify (with useful lists) what triggers our own task avoidance and for us to observe our reaction kindly and without judgement as a step towards overcoming those physiological reactions we may feel when confronting ourselves with something we’re trying to put off.

So what’s holding you back from writing that story? Could it be

Fear of failure?

Did people praise you for writing as a child? Was that part of your identity? Does it feel dangerous risking people’s (or your own) perceptions of yourself in case you don’t get that publishing deal or the story isn’t as good as you thought it would be? Is it safer not to do it?

A tiny proportion of my picture book rejection letters

Procrastinating leads us to do things last minute, where we can avoid testing our true potential (and risking our sense of self by what we might find) –so the final piece of writing is not a reflection of your true ability but what you can do under last-minute pressure. Are you so frightened of discovering that you’re not what you think you are/want to be, that you’re willing to slow down so much and be last minute in order to avoid your best work being judged?Procrastination allows you to believe that your ability is greater than your performance indicates –you never have to confront the real limits of your ability.

OR

Perhaps people didn’t have confidence in your writing when you were younger (or people don’t now) –and if you did write something, might you be worried that those people may be proved right?Or could what’s holding you back be a

Fear of success?

This may seem less obvious but the authors talk about this:

· Do you sometimes slow down on a project that’s going well?· Do you feel anxious when you receive a lot of recognition?· Are you uncomfortable with compliments?· Do you worry about losing your connection with relatives if you’re successful?

And perhaps…

· You fear/believe success in writing will demand more of you than you’re willing/able to give (many of us know successful writers who are now extremely pressed for time in the writing and personal lives).· You’ll turn into a workaholic; people will become obstacles –success will mean loss of control and loss of choice in your life· You may be considered selfish or full of yourself· You may get hurt –do you really want to be judged by your readers/reviewers? –bad reviews/low sales figures can be extremely demoralising.

There are lots of reasons explored in the book, and identifying your own personal reasons will help you take practical steps towards writing and stopping putting things off.

The book also helps you identify your own procrastination style

Mine (when I should be writing)? -reading emails, surfing the web, looking on Facebook, working on something less important, sitting and staring, going to sleep

Your own physical feelings when you’re meant to be starting something but are considering procrastinating:

Mine? –a feeling in my chest and tummy; feeling light-headed

And your own excuses?

Mine? I’ve got to get organised first; I don’t have everything I need; I don’t have time to do it all so there’s no point in starting; it might not be good enough; I’ll wait until I’m inspired; I don’t feel well; I’m too tired right now; I’m not in the mood; I’ve done the worst part of it; the final bit won’t take much time so I can do it later.

And the book encourages you to monitor what’s happening for a week and try an experiment… which is what I did.

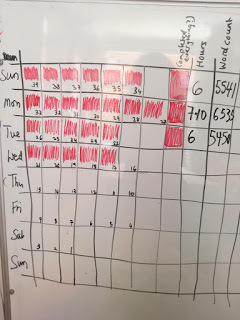

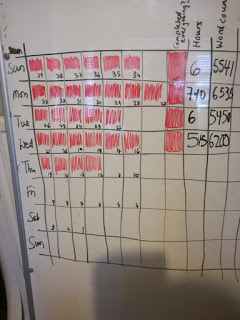

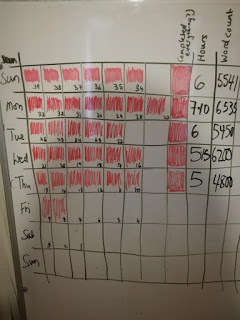

MY ONE-WEEK PROCRASTINATION AND WRITING EXPERIMENT

The authors recommend that you

· Select a single goal –with a desire to learn from both success and failure (think like a researcher gathering data rather than a critic passing judgement) –I used to be a researcher so this appealed to me and made it seem like it was less personal;

· List the steps (and do a reality check –can all those things be done in the time you have?) It was going to be full-on, but yes, it was realistic –if I didn’t procrastinate;

· What’s the very first step? –write it down; should be small and easy;

· Get feedback from others –perhaps other writers- about the achievability of the goal;

· Consider the feelings you have now you’ve got your goal –excited and scared;

· Could visualise your progress; optimise chances (where you work and when, etc) –this one is never going to work for me as I don’t visualise, but it could help other people;

· Stick to the time limit;

· Don’t wait until you feel like it –this was going to be a challenge, as not feeling like I’m in quite the right mood for writing is one of my biggest excuses.

And this is what they suggested you do during the week:· Watch out for your excuses –an excuse means you’re at a choice point: you can procrastinate or you can act (so go from ‘I’ll do it later’ to ‘I’ll just to fifteen minutes…’ (and think –how do I feel?) –I kept a journal for the week, writing at the beginning and the end of each day, saying how I felt before I started, and then commenting on the day at the end of each day.

· One step at a time (not the whole picture book/novel) –I had a list of exactly what I needed to do each day.

· Work around obstacles

· Reward yourself after progress

· Be prepared to be flexible if necessary

· It doesn’t have to be perfect

At the end of the week, assess your progress

· Examine your feelings

· Review your choice points (at least you’ll have procrastinated more consciously)

I Identify what you've learned.

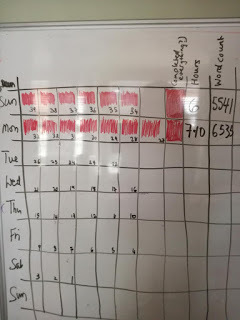

Now I chose a really big goal as my children were going to be away for a whole week and I really wanted to finish the novel I was working on, even though I had about 30,000 words left to write. It really doesn’t have to be that big at all (and it was only possible because I was going to have a whole week without any responsibilities, so I was in an unusual position).I went through the list of scenes I had left to write and calculated how long I thought each scene would take, realistically if I didn’t procrastinate at all, and then worked out how many I’d have to write each day in order to finish the book. This worked out at about six hours per day –IF I didn’t procrastinate at all but just wrote.

And then I kept a journal for that week and just did exactly what I had said I’d do, thinking of myself like a dispassionate researcher, monitoring how I felt and what I did when I felt like I really didn’t want to write a certain part (or any part).

And…

(Shame that I accidentally forgot to colour in three of the scenes on the final day but I did finish them. Honest)

I finished! I wrote more than 30,000 in a single week!

I had never written anything like the amount I wrote that week. And I am convinced that I wouldn’t have been able to do it without the procrastination book. But the most interesting thing to come out of it for me was that the excuse I’ve used so much as a writer:

I’m not in the right mood

was irrelevant to what I wrote. When I feel like I’m not in the mood (or when I use that excuse), I often find some other work to do instead of writing. But this time, I didn’t. I just monitored how I was feeling, acknowledged it, and then did it anyway. And what I found from my notes on the experiment was that the times when I did it when I wasn’t in the mood, I was just as productive as the times when I did feel in the mood, and having read all those scenes now (as part of the whole book), there is no difference in how good those scenes were. This is probably the most important thing I’ve learned from the whole process: I did genuinely think that there were times when I was going to write better and times when I was going to write less well (or not at all) because of my mood –but it really didn’t make a difference –

as long as I made myself do it.

I have had to abandon my romantic notion of the muse being present. It really was –for me- just a case of showing up and doing it. And I genuinely didn’t quite believe that –until I did the experiment.I should just point out that this related to writing ‘up’ the novel once I’d done all the creative plotting, which I couldn’t work on in this way of a certain number of hours a day for a week, at all –not yet, anyway… But once I’ve worked out a structure for a picture book or a novel, I know now that any excuse that I am just not in the mood, is exactly that: an excuse.

There’s a lot more useful stuff in the book, which I can’t go into now as there’s no time, which includes suggested techniques to reduce your procrastination, like: using little bits of time (check out their unscheduled on page 198); have an accountability partner (I have for writing, and it’s great); work together (for example, like we do in our local SCBWI group, weekly, where we write alongside each other); say no to e-addictions/have a low information diet; do more exercise, and take exercise breaks; be realistic about time; just get started; use the next fifteen minutes, watch for your excuses and use your procrastination as a signal. In the end, it’s your choice:

You can delay or you can write

-and you can write even though you’re uncomfortable.

I really couldn’t recommend this book highly enough -for picture book writers, novel writers, everyone. And if I can identify why I’m coming up with excuses and learn to put those thoughts and feelings aside and write anyway, then you can do it, too.Huge thanks to my wonderful friend and former partner-in-procrastination Caroline Keenan for recommending this book to me. You know me well!

Do you have any tips for beating procrastination? Have you read this book, and if so, how helpful did you find it? Please do reply in the comments, below…

Thank you –and happy writing –even if, or especially if, it’s uncomfortable!

www.julietclarebell.com

Published on October 15, 2018 07:43

October 7, 2018

Humour in Picture Books by Liz Brownlee, Poet

Louis Franzini PhD, in his book Kids Who Laugh, identifies 13 categories of humour which children recognise – I calculated once that 10 of them are already being used in books meant for pre-schoolers and infants. Which has to point to the fact that humour is very important to humans. This conclusion is certainly borne out by numerous studies Franzini cites into how having a sense of humour is linked to higher levels of intelligence, creativity and flexible thought processes, and is also associated with higher self-esteem, good self-control and a sense of empathy.

Other research (despite a new study showing that virtually everything about us is governed by nature not nurture) shows there is good evidence that a sense of humour is acquired as a child, so it’s jolly lucky it sells both picture books and poetry!

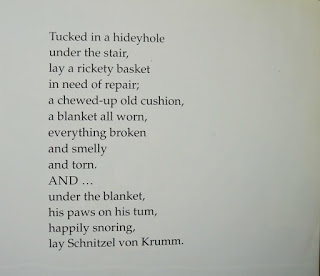

So – I can hear you wondering what those 10 types of humour are, and frantically totting up types on your fingers. Verbal wordplay such as I have just used is one… alliteration fills this job nicely. Children’s poetry and the poetic language in many children’s picture books employ this simple way to make the text fun to say, fun to listen to, and to help with the humour of what the words are saying. Language in everyday life is logical, orderly, and usually unrhythmic, without sentences ending in rhyming couplets, so it is made funnier to children when they do. Lynley Dodd’s picture books are wonderful examples of both alliteration and rhyme – here’s a page of Schnitzel von Krumm’s Basketwork:

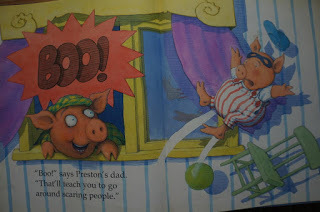

Surprise is number two in my list. Laughter is an automatic reaction to the release of tension. In Colin McNaughton’s ‘Boo’, Preston the Masked Avenger piglet goes round town shouting ‘boo’ unexpectedly and gets his come-uppance when he does it to his dad pig, and dad pig sends him to his room and does it back.

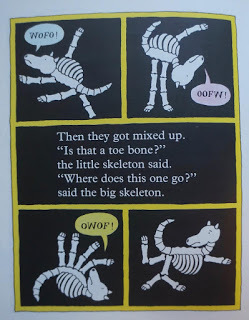

Number three is slapstick. Number four is absurdity. ‘Funnybones’ by Janet and Allan Ahlberg was a book that never failed to have my 4 year old son helpless with laughter. The book is also full of alliteration. A big skeleton, a little skeleton and a dog skeleton who live down a ‘dark, dark cellar, down a dark, dark staircase’ etc. go out at night to scare people, but mainly end up scaring themselves. The big skeleton throws a stick for the dog skeleton. The dog skeleton jumps for it and bumps into a tree, and ends up as a little pile of bones. The big skeleton and the little skeleton try to put him back together again, but get his skeleton all mixed up. The dog can only say ‘WOFO’. They try again, and this time he says ‘OOFW’. Then ‘OWOF’ and ‘FOOW’.

My son could not read, so it fascinated me that the idea that the dog’s ‘WOOF’ was the wrong way round struck him as so funny. Clearly the word sounds are being listened to along with the meaning by this age This must help with the acquisition of reading skills. Alliteration, wordplay, slapstick, absurdity and the realization that letters in the wrong order say something different, all in one book. No wonder it is still on sale – my son is 26!

Human predicament is my number five. Obviously the predicaments available to picture book authors are narrowed to those that are pertinent to the very young, and a book we bought in Canada, I Have To Go!, by Robert Munsch, illustrated by Michael Martchenko shows this one perfectly. Andrew is asked by his parents if he needs to go pee before setting off on a journey; “No, no, no, no,” said Andrew. “I have decided never to go pee again.” Obviously five minutes into the journey he has to go, very urgently. Later he goes to play in the snow at Grandma’s without having a pee first, and his snowsuit has 5 zippers, 10 buckles and 17 snaps.

Everyone has to pee. The child being read to knows this. The humour for the child is in the knowledge and having this knowledge, and knowing what is going to happen fosters empathy (feeling for the child) at the same time as self-esteem (knowing he knows better) and the ability to foresee the logical conclusion to a train of events.

Six, defiance, and seven, incongruity are ably illustrated by David McKee, in his book Who’s a Clever Baby Then? “Who’s a clever baby then?” said Grandma. '“And where’s my oofum boofum pussy cat? Say ‘cat’, Baby.” “Dog,” said Baby.’ Saying ‘No’ and getting away with it, being naughty, getting one over on a parent, brother, sister or friend, is extremely appealing to a young child who has little control over their own life. The incongruity of the baby saying dog instead of cat is also funny to the child listening.

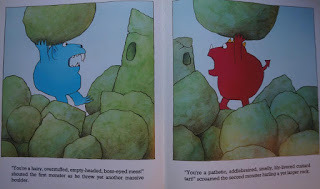

Two monsters by David McKee uses mainly violence, type number eight. The two monsters argue over whether day is disappearing or night is arriving – as they live on either side of a mountain they cannot see what the other monster can.

They end up trading very funny insults and then throwing rocks at each other until the mountain is destroyed and the truth that they are both right is revealed. Their argument is resolved – hopefully revealing that arguments are often absurd and a happy resolution is possible. Incidentally I am convinced David McKee has listed types himself as I found loads of his books each of which mainly used one category of humour.

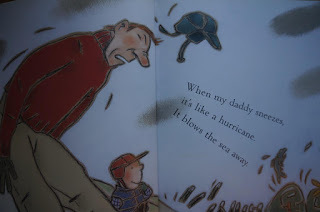

Exaggeration is number nine and of course ten thousand times more important than any of the other categories. It is often paired with absurdity. Carl Norac’s ‘My Daddy is a Giant’, illustrated by Ingrid Godon, is a gorgeous example of exaggeration.

The exaggerations are affectionate, funny and descriptive. ‘When the clouds are tired, they come and sleep on my daddy’s shoulders’.

Simple puns is the final category. These are not usually used until the child is older, but can be used when the text is helped by pictures which helps the joke easy to understand. TWO CAN TOUCAN by David McKee uses a pun. It’s about a plain black bird without a name. He goes to seek his fortune. Because of his big beak, he’s useless at most jobs -except carrying two cans of paint.

All these picture books are fairly old as they are the ones we had when my children were small. But any I’ve bought or read since have all employed a mixture of the above types of humour. I’m a poet, not a picture book writer (yet!), but of course all these tools and types of humour are used in poetry too, for ages 3 up to 7 – and how remarkable is that?

Liz Brownlee, National Poetry Day Ambassador, Liz's personal blog: http://www.lizbrownleepoet.comLiz's blog for all things poetry related: http://www.poetryroundabout.comApes to Zebras, an A-Z of Shape Poems, Reaching the Stars, Poems about Extraordinary Women and Girls, The Same Inside, Poems about Empathy and Friendship. Reference: Dr Louis Franzini, PhD. Professor of Clinical Psychology San Diego University Ca. Kids Who Laugh, New York, Square One Publishers, 2002

Published on October 07, 2018 22:00

September 30, 2018

Following The Logic, by Pippa Goodhart

I do love a simple story that makes logical sense in the barmiest of ways. Some of my favourite picture books take an idea and follow it to a logical, very funny, conclusion that still manages to surprise.

Here are three prime examples, and I’d love to know of more –

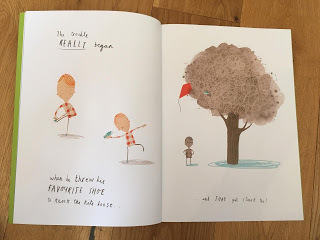

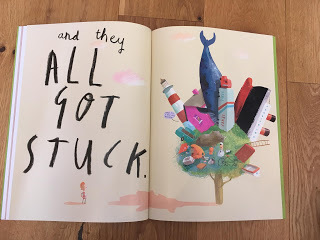

In Oliver Jeffers’ ‘Stuck’, Floyd’s kite gets stuck in a tree, so he does what many of us have done in the same situation, and he throws his shoe at the kite in the tree. But it doesn’t dislodge the kite. It, too, is stuck in the tree.

Floyd then throws up more and bigger things of kinds we perhaps haven’t yet tried throwing into trees, such as a whale and house.

How does Oliver Jeffers solve this situation? Floyd suddenly thinks of using a saw. We assume that saw is going to be used to cut down the tree … but, no! Floyd swerves away from that, and chucks the saw into the tree … and at last the kite falls out of it. So silly, and yet so wonderfully logical!

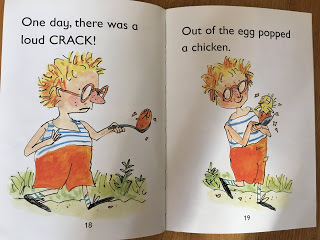

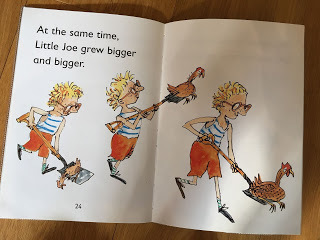

Leapfrog early reading book ‘Little Joe’s Big Race’, written by Andy Blackford and illustrated by Tim Archbold, follows the logic of an egg and spoon race. Joe, egg and spoon in hand, races, coming last but keeping on racing, on and on. He races so far over so long that the egg hatches a chicken!

The chicken grows, and Joe grows too as he runs, until he finally circles the earth to end up back at school sports day. We already know he didn’t win the egg and spoon race. But it turns out that he does win the chicken and spade race! Hooray!

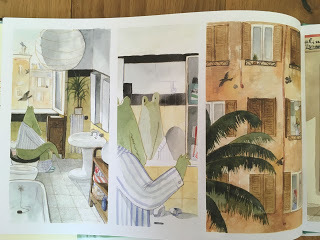

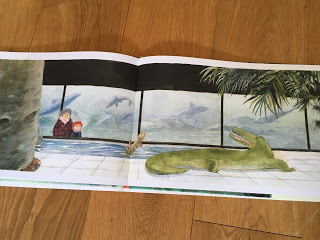

‘Professional Crocodile’ by Giovanna Zoboli and Mariachiara Di Giorgio is a wordless picture book. It shows the Crocodile getting up and going to work in a very human way.

Its only on the last spread that we finally find out what he work is. We see him arriving at work, then undressing and putting towel around his middle before finally appearing … as a ‘naked’ crocodile on display in a zoo. Of course! You didn’t think a crocodile would be a teacher or something, did you?! Well, yes, of course we did, given what’s gone before. But it’s a delight to be fooled in this way.

What other logical sequences to fun conclusions in picture books can you think of?

Published on September 30, 2018 16:30

September 23, 2018

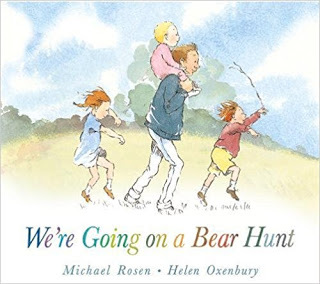

Although some people will only know We’re Going on a Bear Hunt as a picture book by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury, the text is adapted from an American folk song and many children of my generation will have known it as a scout and guide campfire song long before the picture book was published.

We’re Going on a Bear Hunt is one of the most celebrated examples of a picture book adapted from a song. Song lyrics often need some authorial tinkering to make them work well as a picture book text and the onomatopoeic sounds in the book (Swishy swashy! Splash splosh! etc.) and the verses about the forest and the snowstorm are both Rosen's invention.

My picture book She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain, illustrated by Deborah Allwright, was also adapted from an American folk song.

When an editor asked me to adapt the song a few years ago, I decided that the first thing I needed to do was reduce the repetition. While a degree of repetition is often encouraged in picture book writing, I felt that having the same phrase repeated five times on every spread would become a little tedious, so I replaced two of the repeated phrases in each verse with a rhyming couplet.

So this first verse of the original folk song:

She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming ‘round the mountain,She'll be coming ‘round the mountain,She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!Became this in my picture book version:

She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!I also replaced most of the folk song's later verses – including the ones about sleeping with grandma and killing the old red rooster – with new verses. The new verse where the cowgirl paints the whole town purple was a cowboy-hat-tip to the Clint Eastwood western High Plains Drifter, in which an enigmatic cowboy literally paints a whole town red.

Yes, she'll whistle like a train,

As she speeds across the plain,

She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!

One of Deborah Allright's spreads from She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain (now out of print).

One of Deborah Allright's spreads from She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain (now out of print).Song often make it onto the page without any authorial tinkering. There are plenty of picture book adaptations of Over in the Meadow and Old MacDonald had a Farm that feature the original lyrics …

… but there are also quite a few adaptations that have been re-written to include a more exotic, mechanical or flatulent cast of characters.

While all of the above examples are adapted from folk songs, picture book adaptations of contemporary songs have become increasingly common in recent years. One of the first examples I remember seeing is this 2007 adaptation of the Peter Paul and Mary song Puff the Magic Dragon illustrated by Eric Puybaret.

Since then, contemporary songs by Bob Marley, Dolly Parton, John Lennon, Kenny Loggins and many others have been adapted into picture books.

Illustrator Tim Hopgood has produced a series of picture book adaptations of classic 20th Century songs.

As picture books adapted from songs have become increasingly popular, the interval between the song coming out and the picture book being published seems to be reducing. Last year’s picture book adaptation of When I Grow Up, illustrated by Steve Anthony, was published just seven years after the song first appeared, in Tim Minchin’s Matilda the Musical.

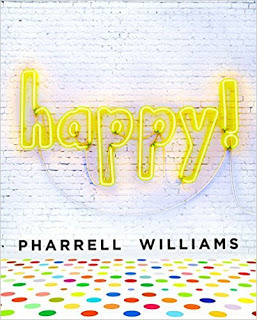

And the picture book version of Pharrell Williams’ Happy! (illustrated with photographs) came out only one year after the song was released!

So if you’re a picture book author or illustrator looking for ideas, you might try flicking through an old songbook or switching on the radio. If you’re lucky, you might discover the inspiration for the next We’re Going on a Bear Hunt!

In the meantime, if you know of any good picture book adaptations of songs, do tell us about them in the comments section below.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.Find out more about Jonathan and his books at his Scribble Street web site or his blog. You can also follow Jonathan on Facebook and Twitter @scribblestreet.

See all of Jonathan's posts for Picture Book Den.

Published on September 23, 2018 22:30

Although some people will only know We’re Going on a Bear Hunt as a picture book by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury, the text is adapted from an American folk song and many children of my generation will have known it as a scout and guide campfire song long before the picture book was published.

We’re Going on a Bear Hunt is one of the most celebrated examples of a picture book adapted from a song. Song lyrics often need some authorial tinkering to make them work well as a picture book text and the onomatopoeic sounds in the book (Swishy swashy! Splash splosh! etc.) and the verses about the forest and the snowstorm are both Rosen's invention.

My picture book She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain, illustrated by Deborah Allwright, was also adapted from an American folk song.

When an editor asked me to adapt the song a few years ago, I decided that the first thing I needed to do was reduce the repetition. While a degree of repetition is often encouraged in picture book writing, I felt that having the same phrase repeated five times on every spread would become a little tedious, so I replaced two of the repeated phrases in each verse with a rhyming couplet.

So this first verse of the original folk song:

She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming ‘round the mountain,She'll be coming ‘round the mountain,She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!Became this in my picture book version:

She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!I also replaced most of the folk song's later verses – including the ones about sleeping with grandma and killing the old red rooster – with new verses. The new verse where the cowgirl paints the whole town purple was a cowboy-hat-tip to the Clint Eastwood western High Plains Drifter, in which an enigmatic cowboy literally paints a whole town red.

Yes, she'll whistle like a train,

As she speeds across the plain,

She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!

One of Deborah Allright's spreads from She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain (now out of print).

One of Deborah Allright's spreads from She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain (now out of print).Song often make it onto the page without any authorial tinkering. There are plenty of picture book adaptations of Over in the Meadow and Old MacDonald had a Farm that feature the original lyrics …

… but there are also quite a few adaptations that have been re-written to include a more exotic, mechanical or flatulent cast of characters.

While all of the above examples are adapted from folk songs, picture book adaptations of contemporary songs have become increasingly common in recent years. One of the first examples I remember seeing is this 2007 adaptation of the Peter Paul and Mary song Puff the Magic Dragon illustrated by Eric Puybaret.

Since then, contemporary songs by Bob Marley, Dolly Parton, John Lennon, Kenny Loggins and many others have been adapted into picture books.

Illustrator Tim Hopgood has produced a series of picture book adaptations of classic 20th Century songs.

As picture books adapted from songs have become increasingly popular, the interval between the song coming out and the picture book being published seems to be reducing. Last year’s picture book adaptation of When I Grow Up, illustrated by Steve Anthony, was published just seven years after the song first appeared, in Tim Minchin’s Matilda the Musical.

And the picture book version of Pharrell Williams’ Happy! (illustrated with photographs) came out only one year after the song was released!

So if you’re a picture book author or illustrator looking for ideas, you might try flicking through an old songbook or switching on the radio. If you’re lucky, you might discover the inspiration for the next We’re Going on a Bear Hunt!

In the meantime, if you know of any good picture book adaptations of songs, do tell us about them in the comments section below.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.Find out more about Jonathan and his books at his Scribble Street web site or his blog. You can also follow Jonathan on Facebook and Twitter @scribblestreet.

See all of Jonathan's posts for Picture Book Den.

Published on September 23, 2018 22:30