Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 25

August 4, 2019

Image Flash-Back- The longevity of favourite childhood illustrations - Garry Parsons

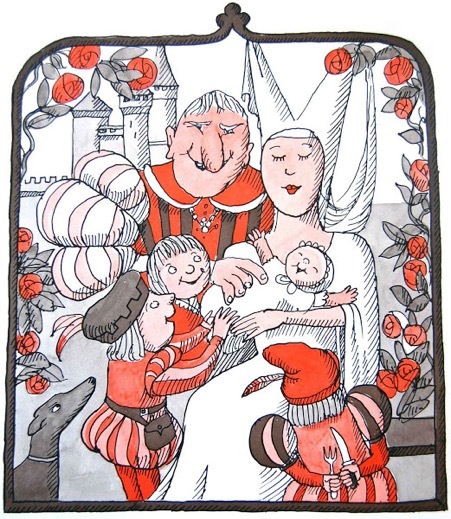

In a recent guest blog post for The Picture Book Den, author Timothy Knapman included an image that he recalled from his childhood. The illustration is by writer and illustrator Tomi Ungerer, whose books for children included “Moon Man,” first published in 1966, and Tim’s favourite “Zeralda’s Ogre,” which was published a year later.

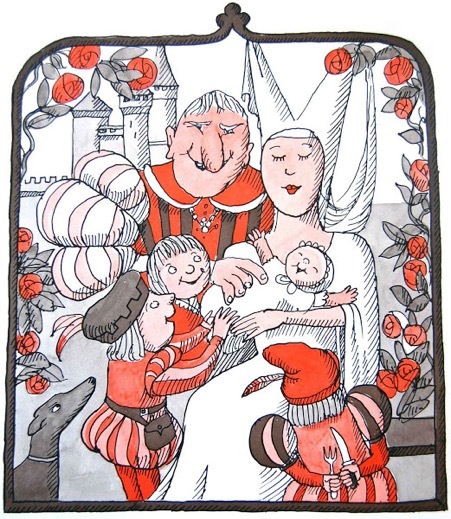

On the last page of "Zeralda's Ogre" we see a picture of the happy family; proud parents Zeralda and her ex-ogre are surrounded by their offspring and Zeralda has a baby in her arms. One of her older children leans over his new-born sibling, apparently adoringly. But behind his back – visible to us but not to his parents – he holds a knife and fork.

Zeralda’s Ogre by Tomi Ungerer

Zeralda’s Ogre by Tomi UngererTim says, "I don’t know why that image has stayed with me. I do remember thinking it was funny rather than scary. I was a ghoulish child, I suppose. But – more than that – it’s the subversiveness of the image, the feeling that “you’re not supposed to do that!" that was – and remains – truly thrilling."

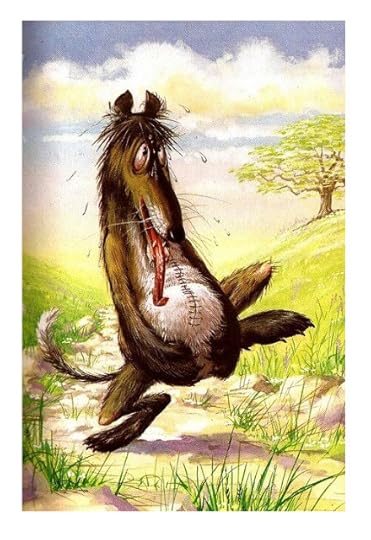

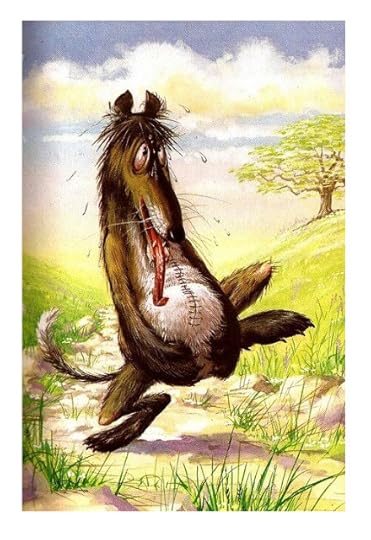

Intrigued by the impact this clearly had on the young Tim Knapman, I remembered an illustration from my childhood. Surfacing from my memory, like a ship hauling on deck an unexpected sea monster, was an image of a staggering wolf with his tummy in stitches. A quick search online not only brought back the image in all its gruesomeness but also all the feelings I had as a young boy looking at it, as if fresh out of the fridge!

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books For me, this image was pure cruelty. His agonising stance, his rough worn knees and pained expression, as he sweated and panted along the track alone, were shocking. All I wanted to do was to rush in there and help him. I remember the sense of his aimless, desperate wandering - after all, who, in this land, was going to help him? - and I was pretty sure there wasn’t a reputable hospital nearby. And as for the goats who did this to him, I despised them and their self-righteous goodness, their spiteful alter egos, not to mention their bad sewing skills, which, I remember thinking as a boy, were no better than mine.

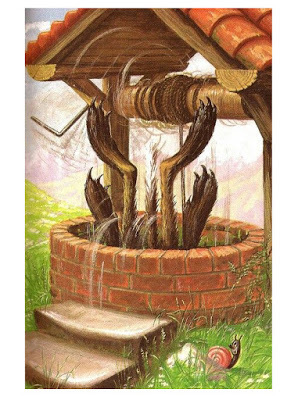

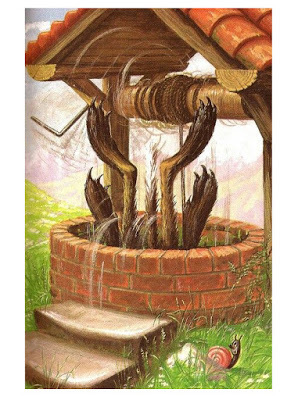

In the story, based on the Grimm fairy tale, the mother goat leaves her kids in the house while she goes out, but warns them about a prowling wolf and says not to open the door to him if he comes calling. But the wolf tricks his way into the house and swallows the kids whole, all except one who hides in the grandfather clock. On her return, the distraught mother finds the wolf sleeping off his feast under a tree nearby and cuts open his stomach to set the kids free. She then instructs her young ones to gather rocks to fill the wolf’s tummy and she sews him back up. (Having hooves clearly makes sewing tricky, hence the haphazard stitching). Waking from his slumber, the wolf, feeling not so great, staggers and stumbles under the weight of the rocks towards a well, where he falls in to his demise.

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books

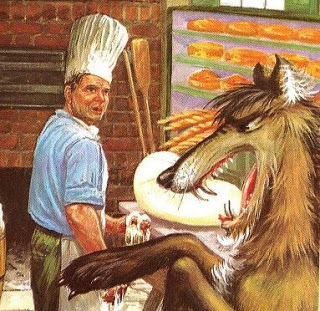

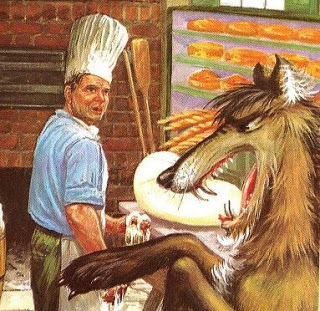

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading BooksLooking through the rest of the book, each illustration is just as loaded for me as the next. The baker’s disbelief at the sight of the wolf in his kitchen, the wolf’s enormous and terrifying feet at the window and even the texture and thickness of the dough on the wolf’s foot as he rampages through the goats' house.

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading BooksI had questions, too, about why the baker is looking slightly to the side of the wolf drooling in his kitchen and not directly at him, and doubts about why the wolf wouldn’t wake up at the jabbing insertion of the goat’s scissors into his belly when she opens him up. In hindsight, some of my interpretations of Robert Ayton’s illustrations as a child were probably not what he had anticipated or intended, my feeling sorry for the wolf being one of them. But I don’t think that matters, they certainly gave me a lot to think about, and the feelings remembered are so clear to me I can’t help but wonder how much influence this subconscious illustration library has had on my work as an illustrator today.

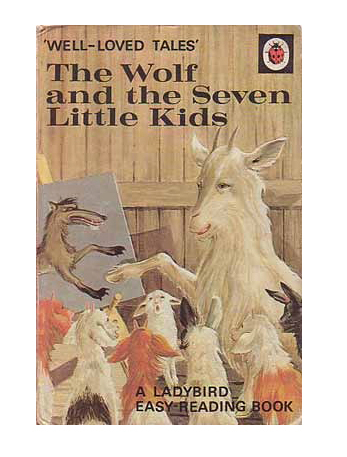

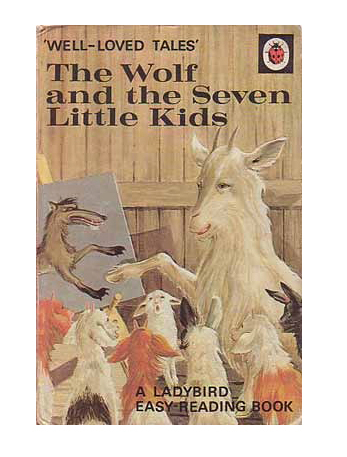

"The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids" (1969), which brought me delight and horror in equal measure, was part of a series of “Well-Loved Tales”, a LadyBird Easy-Reading Book (though easy on the psyche maybe not!) that included other gems which I also relished such as "The Little Red Hen and the Grains of Wheat," "The Magic Porridge Pot" and "The Elves and the Shoemaker," all re-told from the original Grimm stories by Vera Southgate and illustrated by Robert Lumley and Robert Ayton, among others.

The wolf’s tragic story wasn’t the only illustration embedded into my memory, of course there are others.

Each Christmas I was given a Rupert annual as a gift. I never read the stories inside properly, I only looked at the pictures and from these I would form my own version of Rupert’s escapades. But the images that thrilled me the most were the end pages. These were full scenes, often of Rupert and his chums looking out over a vista, a snap shot in time from one of his adventures, which, for me, somehow always felt like the exciting possibility of the summer holiday I was about to have. I was transported. I was there in the scene with Rupert. I was one of his mates!

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1974 end papers - signed Cubie

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1974 end papers - signed Cubie

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1976 end papers - signed Cubie

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1976 end papers - signed Cubie

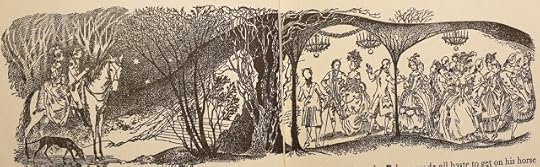

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1973 end papers - signed BestallInspired by William Roscoe’s 1807 poem of the same name, Alan Aldridge’s "The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast" (1973) also included landscapes and scenes. For me the background was important, the incidental details were the parts I liked most, and Alan Aldridge’s pictures are crammed full of the essential non-essentials and, as with the Rupert annuals, I never read the text.

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1973 end papers - signed BestallInspired by William Roscoe’s 1807 poem of the same name, Alan Aldridge’s "The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast" (1973) also included landscapes and scenes. For me the background was important, the incidental details were the parts I liked most, and Alan Aldridge’s pictures are crammed full of the essential non-essentials and, as with the Rupert annuals, I never read the text. The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator) The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)

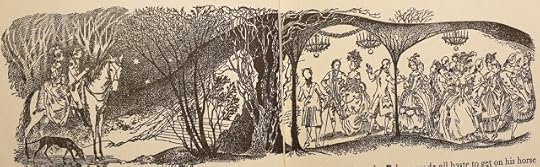

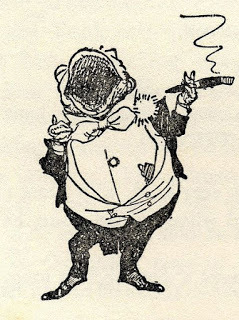

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)These were, and still are, thrilling and engrossing images and, like the wolf’s story, brought up exciting questions and a lot of wondering. The illustration of Dandy Rat and the Footpads includes a visual game and invites you to find the Stoat’s name hidden in the picture, exciting in itself, but what really interested me as a child was the size of the horse compared to the other characters. Was the horse a special tiny horse or, more exhilarating, were Dandy and his mates the size of an adult human? I loved the badness of this image. These were subversive characters up to no good.

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)I like that a child’s interpretation of an illustration can be utterly different from its intention and that stories made up in the mind can be equally thrilling for the individual. What freedom and flights of fancy the imagination can take from a captivating image. Does it really matter where it takes the reader? I think probably not.

I was curious to know what images other authors and illustrators might have fixed firmly in the subconscious or lying latent in the mind, so I asked the members of the Picture Book Den team to reveal them…

Pippa GoodhartI’m afraid that mine is a horror one as well. I’ve just popped around to my mum’s to photograph this from the book of Edgar Allan Poe stories illustrated by Arthur Rackham. This is from "The Pit And The Pendulum." My big brother showed it to me when I was quite young. He explained that the swinging axe pendulum was coming lower and lower. The picture fascinated and terrified me. I have still never read the story, but I was deeply aware of that book on that bookcase, and, just sometimes, I would take a deep breath and open it. It still makes me feel sick.

I can remember lots of nice pictures from other books, but this is the one that churns me, taking me right back to childhood.

Arthur Rackham

Arthur RackhamJane ClarkeMine, too, is from a Ladybird Book, "Down Duckling," illustrated by A.J. McGregor, 1942 (!)

It's of Downy Duckling falling through the ice and dragging his friend Monty in with him. (We lived near Wicksteed Park lake which often iced over in the winter, and my parents instilled in me the dangers of falling through thin ice). The image brings back the remembrance of the feelings it invoked - fear and distress - quickly followed by the huge relief of the happy ending. But it's not the happy ending image that I held in my mind's eye, it's this one.

A.J.McGregor

A.J.McGregorLucy RowlandI also found the images from the old Ladybird fairy tale books really striking and memorable and looking at them now really takes me right back! My sister and I had so many of the books, so it was hard to think of a single image, but I remember the end papers being a big tree with all the characters on and I must have looked at that so many times!

LadyBird Fairy Tales - end papers

LadyBird Fairy Tales - end papersPaeony Lewis

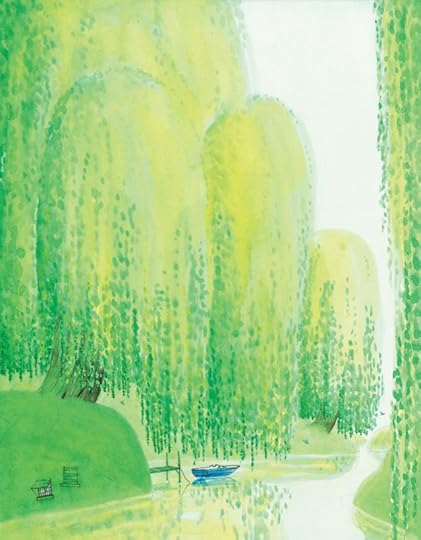

For me it’s usually the theme behind an entire book that I recall, particularly when it resonated with me on an emotional level. However, I’ve always been intrigued by secrets and hidden worlds, so I adored Andy Pandy’s idyllic picnic behind the magical fronds of the willow tree. Later in life I lent the book to someone so they could pick out a weeping willow tree for me at the garden centre – I wanted to emulate Andy Pandy, Looby Loo and Teddy (now I’ve written this, I sound rather pathetic!).

Andy Pandy and the Willow Tree, illustrated by Matvyn Wright, early 1960s

Andy Pandy and the Willow Tree, illustrated by Matvyn Wright, early 1960sAlso, I liked to explore the woods at the bottom of the garden and make up stories (this was when very young children went out to play on their own). The thought of a faerie world lurking beneath the ground enthralled me, so I adored this image from the British fairy tale, ‘Kate Crackernuts’.

British Fairy Tales, illustrated by Pauline Diana Baynes, 1965

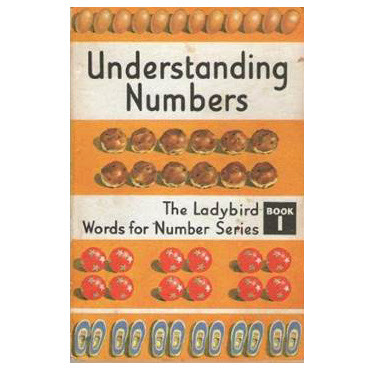

British Fairy Tales, illustrated by Pauline Diana Baynes, 1965Mini GreyI just got thrown into Ladybird Book Central and ended up buying the Ladybird Book of Understanding Numbers because of my fierce memory of those currant buns.

In this image (from The Princess and the Pea, also a LadyBird EasyReader ) the princess is SO extremely wet and shiny and the green dress is unusual – is it a pea premonition? What is she up to running around in her green dress in the rain anyway? But as a child I thought it was just a really exciting picture of a really wet princess.

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)And this picture was very important – it was like the book reaching out to you and saying – yup, it’s all real, come and find me.

But the whole Princess & Pea message is such a stinker – that only royalty are able to be hypersensitive.

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)What appears notable about all these illustrations is not that they are the most loved favourites from our collective childhoods but more that they have un-apologetically imposed themselves onto our memories. Deep treasures that hold complex thoughts and feelings whether you like them or not. I can't help but wonder if the books we make today are having the same impact on children as these images have - we'll just have to wait and see.

Thank you to Pippa, Lucy, Jane, Paeony, Mini and the young Tim Knapman for contributing to this post. If you have an illustration implanted in your memory that you would like to share, please do so in the comments section.

To read Timothy Knapman's post mentioned earlier in this blog:http://picturebookden.blogspot.com/20...

Garry Parsons is an illustrator of many picture books for children but as yet, none with wolves in.

www.garryparsons.co.uk @icandrawdinos

Published on August 04, 2019 22:32

Image Flash-Back!- The longevity of favourite childhood illustrations - Garry Parsons

In a recent guest blog post for The Picture Book Den, author Timothy Knapman included an image that he recalled from his childhood. The illustration is by writer and illustrator Tomi Ungerer, whose books for children included “Moon Man,” first published in 1966, and Tim’s favourite “Zeralda’s Ogre,” which was published a year later.

On the last page of "Zeralda's Ogre" we see a picture of the happy family; proud parents Zeralda and her ex-ogre are surrounded by their offspring and Zeralda has a baby in her arms. One of her older children leans over his new-born sibling, apparently adoringly. But behind his back – visible to us but not to his parents – he holds a knife and fork.

Zeralda’s Ogre by Tomi Ungerer

Zeralda’s Ogre by Tomi UngererTim says, "I don’t know why that image has stayed with me. I do remember thinking it was funny rather than scary. I was a ghoulish child, I suppose. But – more than that – it’s the subversiveness of the image, the feeling that “you’re not supposed to do that!" that was – and remains – truly thrilling."

Intrigued by the impact this clearly had on the young Tim Knapman, I remembered an illustration from my childhood. Surfacing from my memory, like a ship hauling on deck an unexpected sea monster, was an image of a staggering wolf with his tummy in stitches. A quick search online not only brought back the image in all its gruesomeness but also all the feelings I had as a young boy looking at it, as if fresh out of the fridge!

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books For me, this image was pure cruelty. His agonising stance, his rough worn knees and pained expression, as he sweated and panted along the track alone, were shocking. All I wanted to do was to rush in there and help him. I remember the sense of his aimless, desperate wandering - after all, who, in this land, was going to help him? - and I was pretty sure there wasn’t a reputable hospital nearby. And as for the goats who did this to him, I despised them and their self-righteous goodness, their spiteful alter egos, not to mention their bad sewing skills, which, I remember thinking as a boy, were no better than mine.

In the story, based on the Grimm fairy tale, the mother goat leaves her kids in the house while she goes out, but warns them about a prowling wolf and says not to open the door to him if he comes calling. But the wolf tricks his way into the house and swallows the kids whole, all except one who hides in the grandfather clock. On her return, the distraught mother finds the wolf sleeping off his feast under a tree nearby and cuts open his stomach to set the kids free. She then instructs her young ones to gather rocks to fill the wolf’s tummy and she sews him back up. (Having hooves clearly makes sewing tricky, hence the haphazard stitching). Waking from his slumber, the wolf, feeling not so great, staggers and stumbles under the weight of the rocks towards a well, where he falls in to his demise.

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading BooksLooking through the rest of the book, each illustration is just as loaded for me as the next. The baker’s disbelief at the sight of the wolf in his kitchen, the wolf’s enormous and terrifying feet at the window and even the texture and thickness of the dough on the wolf’s foot as he rampages through the goats' house.

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading Books

From The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. LadyBird Easy-Reading BooksI had questions, too, about why the baker is looking slightly to the side of the wolf drooling in his kitchen and not directly at him, and doubts about why the wolf wouldn’t wake up at the jabbing insertion of the goat’s scissors into his belly when she opens him up. In hindsight, some of my interpretations of Robert Ayton’s illustrations as a child were probably not what he had anticipated or intended, my feeling sorry for the wolf being one of them. But I don’t think that matters, they certainly gave me a lot to think about, and the feelings remembered are so clear to me I can’t help but wonder how much influence this subconscious illustration library has had on my work as an illustrator today.

"The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids" (1969), which brought me delight and horror in equal measure, was part of a series of “Well-Loved Tales”, a LadyBird Easy-Reading Book (though easy on the psyche maybe not!) that included other gems which I also relished such as "The Little Red Hen and the Grains of Wheat," "The Magic Porridge Pot" and "The Elves and the Shoemaker," all re-told from the original Grimm stories by Vera Southgate and illustrated by Robert Lumley and Robert Ayton, among others.

The wolf’s tragic story wasn’t the only illustration embedded into my memory, of course there are others.

Each Christmas I was given a Rupert annual as a gift. I never read the stories inside properly, I only looked at the pictures and from these I would form my own version of Rupert’s escapades. But the images that thrilled me the most were the end pages. These were full scenes, often of Rupert and his chums looking out over a vista, a snap shot in time from one of his adventures, which, for me, somehow always felt like the exciting possibility of the summer holiday I was about to have. I was transported. I was there in the scene with Rupert. I was one of his mates!

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1974 end papers - signed Cubie

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1974 end papers - signed Cubie

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1976 end papers - signed Cubie

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1976 end papers - signed Cubie

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1973 end papers - signed BestallInspired by William Roscoe’s 1807 poem of the same name, Alan Aldridge’s "The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast" (1973) also included landscapes and scenes. For me the background was important, the incidental details were the parts I liked most, and Alan Aldridge’s pictures are crammed full of the essential non-essentials and, as with the Rupert annuals, I never read the text.

Rupert The Daily Express Annual 1973 end papers - signed BestallInspired by William Roscoe’s 1807 poem of the same name, Alan Aldridge’s "The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast" (1973) also included landscapes and scenes. For me the background was important, the incidental details were the parts I liked most, and Alan Aldridge’s pictures are crammed full of the essential non-essentials and, as with the Rupert annuals, I never read the text. The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator) The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)These were, and still are, thrilling and engrossing images and, like the wolf’s story, brought up exciting questions and a lot of wondering. The illustration of Dandy Rat and the Footpads includes a visual game and invites you to find the Stoat’s name hidden in the picture, exciting in itself, but what really interested me as a child was the size of the horse compared to the other characters. Was the horse a special tiny horse or, more exhilarating, were Dandy and his mates the size of an adult human? I loved the badness of this image. These were subversive characters up to no good.

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)

The Butterfly Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast, William Plomer &Alan Aldridge (illustrator)I like that a child’s interpretation of an illustration can be utterly different from its intention and that stories made up in the mind can be equally thrilling for the individual. What freedom and flights of fancy the imagination can take from a captivating image. Does it really matter where it takes the reader? I think probably not.

I was curious to know what images other authors and illustrators might have fixed firmly in the subconscious or lying latent in the mind, so I asked the members of the Picture Book Den team to reveal them…

Pippa GoodhartI’m afraid that mine is a horror one as well. I’ve just popped around to my mum’s to photograph this from the book of Edgar Allan Poe stories illustrated by Arthur Rackham. This is from "The Pit And The Pendulum." My big brother showed it to me when I was quite young. He explained that the swinging axe pendulum was coming lower and lower. The picture fascinated and terrified me. I have still never read the story, but I was deeply aware of that book on that bookcase, and, just sometimes, I would take a deep breath and open it. It still makes me feel sick.

I can remember lots of nice pictures from other books, but this is the one that churns me, taking me right back to childhood.

Arthur Rackham

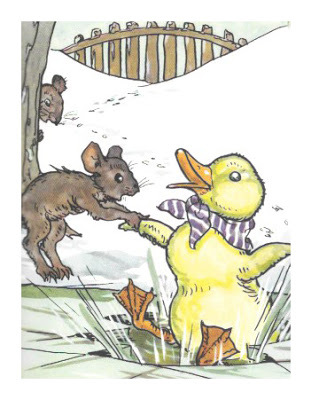

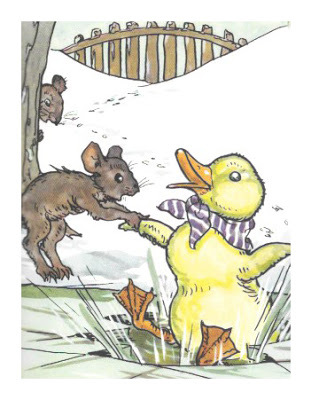

Arthur RackhamJane ClarkeMine, too, is from a Ladybird Book, "Down Duckling," illustrated by A.J. McGregor, 1942 (!)

It's of Downy Duckling falling through the ice and dragging his friend Monty in with him. (We lived near Wicksteed Park lake which often iced over in the winter, and my parents instilled in me the dangers of falling through thin ice). The image brings back the remembrance of the feelings it invoked - fear and distress - quickly followed by the huge relief of the happy ending. But it's not the happy ending image that I held in my mind's eye, it's this one.

A.J.McGregor

A.J.McGregorLucy RowlandI also found the images from the old Ladybird fairy tale books really striking and memorable and looking at them now really takes me right back! My sister and I had so many of the books, so it was hard to think of a single image, but I remember the end papers being a big tree with all the characters on and I must have looked at that so many times!

LadyBird Fairy Tales - end papers

LadyBird Fairy Tales - end papersPaeony Lewis

For me it’s usually the theme behind an entire book that I recall, particularly when it resonated with me on an emotional level. However, I’ve always been intrigued by secrets and hidden worlds, so I adored Andy Pandy’s idyllic picnic behind the magical fronds of the willow tree. Later in life I lent the book to someone so they could pick out a weeping willow tree for me at the garden centre – I wanted to emulate Andy Pandy, Looby Loo and Teddy (now I’ve written this, I sound rather pathetic!).

Andy Pandy and the Willow Tree, illustrated by Matvyn Wright, early 1960s

Andy Pandy and the Willow Tree, illustrated by Matvyn Wright, early 1960sAlso, I liked to explore the woods at the bottom of the garden and make up stories (this was when very young children went out to play on their own). The thought of a faerie world lurking beneath the ground enthralled me, so I adored this image from the British fairy tale, ‘Kate Crackernuts’.

British Fairy Tales, illustrated by Pauline Diana Baynes, 1965

British Fairy Tales, illustrated by Pauline Diana Baynes, 1965Mini GreyI just got thrown into Ladybird Book Central and ended up buying the Ladybird Book of Understanding Numbers because of my fierce memory of those currant buns.

In this image (from The Princess and the Pea, also a LadyBird EasyReader ) the princess is SO extremely wet and shiny and the green dress is unusual – is it a pea premonition? What is she up to running around in her green dress in the rain anyway? But as a child I thought it was just a really exciting picture of a really wet princess.

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)And this picture was very important – it was like the book reaching out to you and saying – yup, it’s all real, come and find me.

But the whole Princess & Pea message is such a stinker – that only royalty are able to be hypersensitive.

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)

The Princess and the Pea LadyBird Easy Reader Robert Ayton (illustrator)What appears notable about all these illustrations is not that they are the most loved favourites from our collective childhoods but more that they have un-apologetically imposed themselves onto our memories. Deep treasures that hold complex thoughts and feelings wether you like them or not. I can't help but wonder if the books we make today are having the same impact on children as these images have - we'll just have to wait and see.

Thank you to Pippa, Lucy, Jane, Paeony, Mini and the young Tim Knapman for contributing to this post. If you have an illustration implanted in your memory that you would like to share, please do so in the comments section.

To read Timothy Knapman's post mentioned earlier in this blog:http://picturebookden.blogspot.com/20...

Garry Parsons is an illustrator of many picture books for children but as yet, none with wolves in.

www.garryparsons.co.uk @icandrawdinos

Published on August 04, 2019 22:32

July 28, 2019

"Designing books is my life – I love it." • Ness Wood

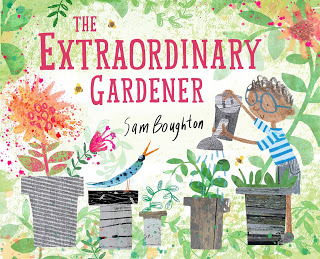

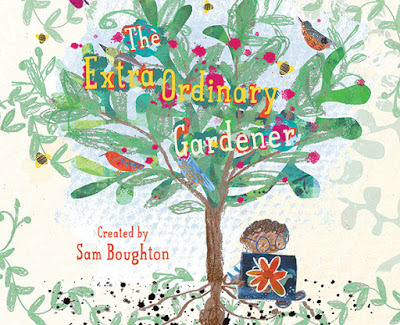

Behind the scenes with acclaimed book designer, Ness Wood. In this guest blog post, Ness looks at the processes involved in designing Sam Boughton's debut picture book, The Extraordinary Gardener, which has recently been shortlisted for the 2019 Klaus Flugge Prize.

The Extraordinary Gardener by Sam Boughton (Tate Publishing, 2018)Hi! I am Ness Wood, a freelance book designer working for various publishers. Holly Tonks (then at Tate Publishing) contacted me to see if I wanted to work on Sam Boughton’s book. I knew Sam’s work as I collaborate with Cambridge School of Art, providing lectures and presenting the students work at the Bologna Book Fair. I love Sam’s illustration and I am aware of how hard she worked for her final show and, after it, continually developing her style to what it looks like today.

The Extraordinary Gardener by Sam Boughton (Tate Publishing, 2018)Hi! I am Ness Wood, a freelance book designer working for various publishers. Holly Tonks (then at Tate Publishing) contacted me to see if I wanted to work on Sam Boughton’s book. I knew Sam’s work as I collaborate with Cambridge School of Art, providing lectures and presenting the students work at the Bologna Book Fair. I love Sam’s illustration and I am aware of how hard she worked for her final show and, after it, continually developing her style to what it looks like today.

Holly sent me the text and I did initial layouts as a starting point. Prior to this, Sam and Holly had been working on the story and flow of the book.

I usually do a few examples of typefaces that I think could be used, to see how different styles of font ‘feel’ with the text and images – it’s is about complimenting the images and story; the typeface could be contrasting or it could be sympathetic to the style of illustration.

The editor and designer and author/illustrator come to an agreement about which to use and then Sam does roughs for the book. Sam had already roughed the book out, but after doing some tweaks to some of the spreads and pacing, she sends me the roughs digitally. I position them in InDesign, considering the text and the image placement in order to get balance across the spread. Some of the spreads may be double-page spreads and some may be singles or have vignettes – at this point the layout is still ‘up in the air.’

Sam Boughton's roughs, a double-page spread from The Extraordinary Gardener

Sam Boughton's roughs, a double-page spread from The Extraordinary Gardener

There is lots of to-ing and fro-ing as a designer – sending layouts by pdf to the editor and then doing the amends and then consulting with Sam to see if she thinks certain layouts/amends to her original layouts will work. It is a collaborative process.

Another rough and early layout from inside Sam Boughton's The Extraordinary Gardener

Another rough and early layout from inside Sam Boughton's The Extraordinary Gardener

After the roughs and layouts are okayed Sam starts the artwork. After Sam has done one piece of artwork, the Tate get a test proof done – this is a proof which will show Sam how all her colours will be reproduced when printed. As Sam works digitally this will show her what she needs to do to amend any of the colours in photoshop to achieve the colour she desires.

It is at this stage that I start doing cover designs – I have the roughs so I can use those in order to start some initial ideas. Covers are often needed early for catalogues/sale material.

I send cover ideas to Holly and she will discuss them with her team. Usually the editor will come back to me with feedback and then I will amend the ideas and they present them again. I will share them with Sam to see what she thinks and then we will discuss further.

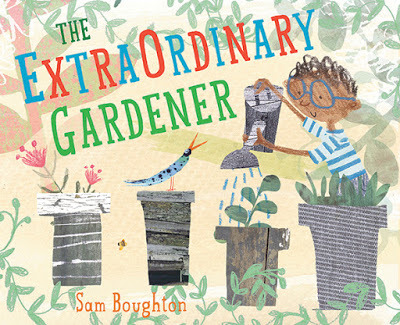

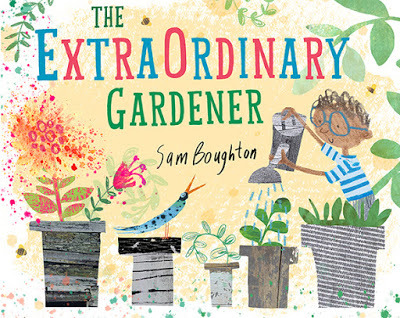

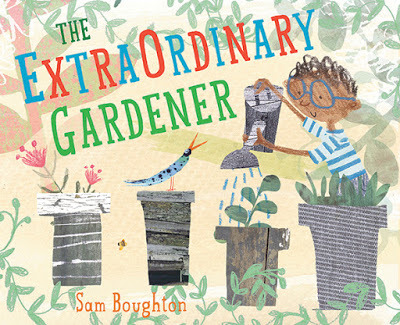

Above and below are early versions of the cover design.

Above and below are early versions of the cover design.

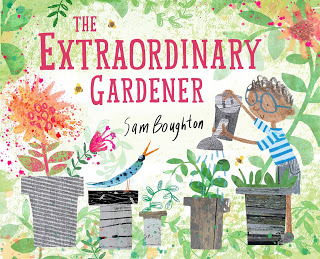

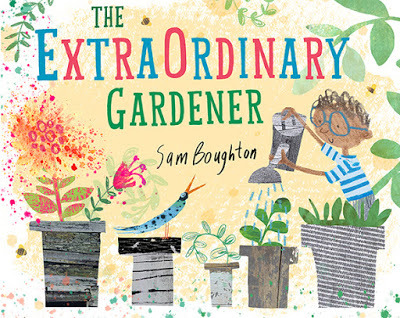

The design is tweaked until finally we have final cover, front and back (shown below)

The design is tweaked until finally we have final cover, front and back (shown below)

Sam will have been doing the artwork for the insides. Her artwork is all done by hand using ink pastel and paint, which she then scans in and puts the elements together in photoshop. So when she has finished the illustrations, she will send it to me digitally, rather than as physical pieces of actual artwork, and I will position the files and then send a pdf with my comments to the editor. We will collate our comments and then send them to Sam. There may be some pieces of artwork Sam needs to amend, though hopefully not, as any issues should have been sorted out at the rough stage. No illustrator really wants to start amending artwork after they have finished the book, but it does happen. The cover is also finalised too at this stage and the type, colours and the back cover copy is also checked. The whole book is then once more checked over, for any typos or sentences that do not quite work or any images that have been cropped wrongly or need repositioning.

The book is then sent to be proofed and then usually the editor and illustrator and designer go through the proofs together. It is very exciting to see the proofs: Sam’s illustrations actually on paper.

No one book is the same, so other projects may have other stages, and more complex issues. Sam’s book is an amazing début and I am very proud to have worked on it.

Many thanks to Ness Wood for her great insight into the design process behind children's picture books. For more information on Ness, book design and illustration, including courses (via Orange Beak Studio), please visit: nesswood.co.uk

Many thanks to Ness Wood for her great insight into the design process behind children's picture books. For more information on Ness, book design and illustration, including courses (via Orange Beak Studio), please visit: nesswood.co.uk

The Extraordinary Gardener by Sam Boughton is one of six books by outstanding debut picture-book illustators, shortlisted for the 2019 Klaus Flugge Prize.The winning book will be announced 11 Sept 2019.

The Extraordinary Gardener by Sam Boughton (Tate Publishing, 2018)Hi! I am Ness Wood, a freelance book designer working for various publishers. Holly Tonks (then at Tate Publishing) contacted me to see if I wanted to work on Sam Boughton’s book. I knew Sam’s work as I collaborate with Cambridge School of Art, providing lectures and presenting the students work at the Bologna Book Fair. I love Sam’s illustration and I am aware of how hard she worked for her final show and, after it, continually developing her style to what it looks like today.

The Extraordinary Gardener by Sam Boughton (Tate Publishing, 2018)Hi! I am Ness Wood, a freelance book designer working for various publishers. Holly Tonks (then at Tate Publishing) contacted me to see if I wanted to work on Sam Boughton’s book. I knew Sam’s work as I collaborate with Cambridge School of Art, providing lectures and presenting the students work at the Bologna Book Fair. I love Sam’s illustration and I am aware of how hard she worked for her final show and, after it, continually developing her style to what it looks like today. Holly sent me the text and I did initial layouts as a starting point. Prior to this, Sam and Holly had been working on the story and flow of the book.

I usually do a few examples of typefaces that I think could be used, to see how different styles of font ‘feel’ with the text and images – it’s is about complimenting the images and story; the typeface could be contrasting or it could be sympathetic to the style of illustration.

The editor and designer and author/illustrator come to an agreement about which to use and then Sam does roughs for the book. Sam had already roughed the book out, but after doing some tweaks to some of the spreads and pacing, she sends me the roughs digitally. I position them in InDesign, considering the text and the image placement in order to get balance across the spread. Some of the spreads may be double-page spreads and some may be singles or have vignettes – at this point the layout is still ‘up in the air.’

Sam Boughton's roughs, a double-page spread from The Extraordinary Gardener

Sam Boughton's roughs, a double-page spread from The Extraordinary GardenerThere is lots of to-ing and fro-ing as a designer – sending layouts by pdf to the editor and then doing the amends and then consulting with Sam to see if she thinks certain layouts/amends to her original layouts will work. It is a collaborative process.

Another rough and early layout from inside Sam Boughton's The Extraordinary Gardener

Another rough and early layout from inside Sam Boughton's The Extraordinary GardenerAfter the roughs and layouts are okayed Sam starts the artwork. After Sam has done one piece of artwork, the Tate get a test proof done – this is a proof which will show Sam how all her colours will be reproduced when printed. As Sam works digitally this will show her what she needs to do to amend any of the colours in photoshop to achieve the colour she desires.

It is at this stage that I start doing cover designs – I have the roughs so I can use those in order to start some initial ideas. Covers are often needed early for catalogues/sale material.

I send cover ideas to Holly and she will discuss them with her team. Usually the editor will come back to me with feedback and then I will amend the ideas and they present them again. I will share them with Sam to see what she thinks and then we will discuss further.

Above and below are early versions of the cover design.

Above and below are early versions of the cover design.

The design is tweaked until finally we have final cover, front and back (shown below)

The design is tweaked until finally we have final cover, front and back (shown below)

Sam will have been doing the artwork for the insides. Her artwork is all done by hand using ink pastel and paint, which she then scans in and puts the elements together in photoshop. So when she has finished the illustrations, she will send it to me digitally, rather than as physical pieces of actual artwork, and I will position the files and then send a pdf with my comments to the editor. We will collate our comments and then send them to Sam. There may be some pieces of artwork Sam needs to amend, though hopefully not, as any issues should have been sorted out at the rough stage. No illustrator really wants to start amending artwork after they have finished the book, but it does happen. The cover is also finalised too at this stage and the type, colours and the back cover copy is also checked. The whole book is then once more checked over, for any typos or sentences that do not quite work or any images that have been cropped wrongly or need repositioning.

The book is then sent to be proofed and then usually the editor and illustrator and designer go through the proofs together. It is very exciting to see the proofs: Sam’s illustrations actually on paper.

No one book is the same, so other projects may have other stages, and more complex issues. Sam’s book is an amazing début and I am very proud to have worked on it.

Many thanks to Ness Wood for her great insight into the design process behind children's picture books. For more information on Ness, book design and illustration, including courses (via Orange Beak Studio), please visit: nesswood.co.uk

Many thanks to Ness Wood for her great insight into the design process behind children's picture books. For more information on Ness, book design and illustration, including courses (via Orange Beak Studio), please visit: nesswood.co.uk The Extraordinary Gardener by Sam Boughton is one of six books by outstanding debut picture-book illustators, shortlisted for the 2019 Klaus Flugge Prize.The winning book will be announced 11 Sept 2019.

Published on July 28, 2019 23:00

July 21, 2019

Interview with Augusta Kirkwood, by Pippa Goodhart

[image error]

I am hugely proud to introduce debut picture book illustrator Augusta Kirkwood. Especially proud since her debut picture book, 'Daddy Frog and the Moon' was written by me. It's lovely that its been published fifty years after the first landing of man on the moon ... which I remember, but Augusta is too young to!

Alan Windram of Little Door Books Little Door Books likes to use new illustrators for Little Door's picture books, and I think the result looks absolutely beautiful. So I asked Augusta how she created that beauty ...

How did you become an illustrator?

Growing up I always loved drawing and storytelling and was encouraged to be creative and interested in everything. I seemed to have a flare for art which I kept developing and experimenting with. After the wonderful Bridge House Art course in Ullapool I studied Illustration at the Edinburgh College of Art where I truly explored the form and art of children’s picture books. I have very fond memories of picture books from my childhood so felt a real purpose in creating stories and illustrations to engage and comfort children. My first picture book with Pippa Goodhart is Daddy Frog and the Moon published by Little Door Books. I was very fortunate that my work was found and selected from my degree show and I am extremely thankful to all involved who gave me this amazing opportunity.

What are your thoughts when faced with a text to illustrate? How do you make the story yours as well as the writer’s?

When faced with a text I find it best to separate the story out into the set amount of pages to help visualise the book from the very beginning stages of creation. This helps shape the pace of the story and allows me to see how I want the illustrations to differ and flow from page to page. It is a privilege to work with another’s story as it is really inspiring to bring a writer’s words to life with your illustrations and collaborate on the book in ways that are exciting and sometimes unexpected.

[image error]Like with any collaboration there is an essence of each individual in the final outcome, and it is that partnership which makes them pretty special. To make the story mine as well, I found it fun to add in a little extra storyline that was not mentioned in the text. In Daddy Frog and the Moon I had fun creating a little sub-storyline with two snails who pop up throughout the book. As the illustrator, how you interpret the characters and setting really shapes the book so it is important to find the perfect match for the text.

[image error]

Can you tell us what your process is in creating your wonderful illustrations?

My process is rather lengthy and has many different stages to it. I begin with sketching ideas for characters and the setting, getting my inspiration observation. photos, books and documentaries. I like to figure out how the characters look and move at this stage, taking moments from the story.

[image error]

I then read the story many times, roughly sketching small scenes that come to mind and understanding where the important moments sit in the book. I then create a storyboard that determines where the illustrations and text sit on the page and how the story flows across those pages.

[image error]

Once I have all that in place I then start creating the illustrations. I have developed a style and process which combines a variety of drawing techniques. I create my illustrations by digitally collaging hand drawn and painted elements, with relief and mono-printed textures. What I love about this process is the flexibility and the trial and error that comes with it.

[image error]It can be really exciting when through experimenting you get an illustration that is not what you expected and often far better than you had planned. My illustration is a refreshing mixture of tactile creating and digital manipulation that keeps the creative process interesting for me.

[image error]Have you other books that you’re working on now? Are you tempted to write your own texts, or do you prefer to work with other writers?

I am currently mulling over ideas and figuring out what I want to work on next. I have a few picture books I made whilst studying that I would like to revisit and polish up and apply all that I have learnt since. I also have other little projects I am planning, like another illustrated alphabet!

Having worked with an author on Daddy Frog and the Moon I would be delighted to work with another as I loved the collaboration and support you get by working in a partnership. I am still so excited about our new book and cannot wait to see where it takes me!

So, all you publishers out there, take note!

Published on July 21, 2019 16:00

July 14, 2019

Building Kids’ Bookshelves - Just One (More) Book At a Time • by Natascha Biebow

I have this image stuck in my mind: just one book on a lonely bookshelf, occupying pride of place.

A precious resource.

The key to so many things, among them MAGIC. Yes, the magic of reading, the magic of another world, the magic of access, the magic of fun.

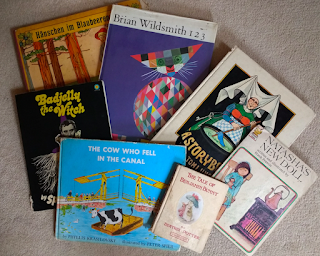

I grew up in a non-English speaking place, so books were treasured gifts from family living in England.

I loved reading, and I loved books. My school had a library also. More windows.

I still have these books. They are friends. When I was old enough, I filched from my parents’ bookshelves as well.

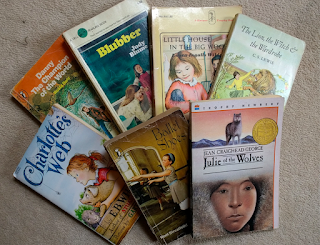

I still have these books. They are friends. When I was old enough, I filched from my parents’ bookshelves as well. But for many, the reality is very different.

In 2018, in the UK, the National Literacy Trust surveyed 44,097 children aged 8-18. It worryingly concluded that 1 in 11 children and young people in the UK don’t own have a book of their own at home.

The same survey also revealed unsurprisingly that “the more books a child owns, the more likely they are to do well at school and be happy with their lives.”

It is well documented that reading for pleasure is the single biggest indicator of a child’s future success, and that reading is key to developing empathy. Picture books (and all books!) matter.

There are some great initiatives to bring books into households:

Booktrust’s Bookstart – which gives free books to every child in England and Wales at two key stages before school, as well as free packs for children with additional needs.

World Book Day – where each child receives a £1 book token towards a book – is a registered charity on a mission to give every child and young person a book of their own. Published figures state that WBD reaches 15 million children and young people in 45,000 schools every year.

With every book donated, there is a greater chance of a child discovering their love of reading and gaining access to a brighter future.

But, clearly, there is more to be done.

Even if children have one book on their shelves, they should be entitled to more. Access to books through free school and public libraries is something that will benefit everyone’s future.

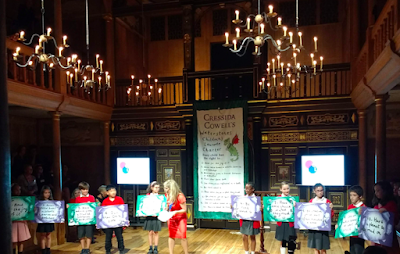

This week, Cressida Cowell took over the mantel of Children’s Laureate from Lauren Child, with an ambitious ten-point charter:

In her impassioned speech at the launch event, Cowell talked about the magic of books and reading for fun. She promised to do more to lobby for access to books, school libraries and author and illustrator visits.

And she promised to LISTEN to what children are saying about books and reading and needing to address our planet’s climate emergency.

School children support Cressida Cowell's laureate launch speech

School children support Cressida Cowell's laureate launch speechCowell admits that it’s a huge list, but she’s committed and she has the laureateship behind her.

But is there something I could do to contribute, I wondered?

I thought about this again . . .

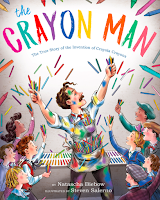

And I remembered: on my author tour this Spring to promote THE CRAYON MAN, I met a teacher and librarian who shared with me the order form for my book that went home with the children. On it, in addition to the possibility of ordering my book to be signed when I came to the school, parents and carers could also choose to buy a book for another child, one who might perhaps not have access to such a thing. And people did!

At another school, the PTA purchased a book for the library and a copy to give out as reward for children who had achieved something noteworthy at school. I know some authors and illustrators, if they're able, sometimes donate a copy of their book to the school library.

If, for every author/illustrator visit we did, even one child got a book who might not otherwise have one, just think how many more books might be on that bookshelf?

_______________________________________________________________

Natascha Biebow, MBE, Author, Editor and Mentor

Natascha is the author of The Crayon Man: The True Story of the Invention of Crayola Crayons, illustrated by Steven Salerno, Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Co-Regional Advisor (Co-Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. She is currently working on more non-fiction and a series of young fiction. She runs Blue Elephant Storyshaping, an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Find her at www.nataschabiebow.com

Natascha is the author of The Crayon Man: The True Story of the Invention of Crayola Crayons, illustrated by Steven Salerno, Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Co-Regional Advisor (Co-Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. She is currently working on more non-fiction and a series of young fiction. She runs Blue Elephant Storyshaping, an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Find her at www.nataschabiebow.com <!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;} @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-520092929 1073786111 9 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;} p {mso-style-priority:99; mso-margin-top-alt:auto; margin-right:0cm; mso-margin-bottom-alt:auto; margin-left:0cm; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-fareast-language:JA;} @page WordSection1 {size:595.0pt 842.0pt; margin:72.0pt 90.0pt 72.0pt 90.0pt; mso-header-margin:35.4pt; mso-footer-margin:35.4pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} -->

Published on July 14, 2019 20:00

July 7, 2019

Tips on writing picture book non-fiction • Moira Butterfield

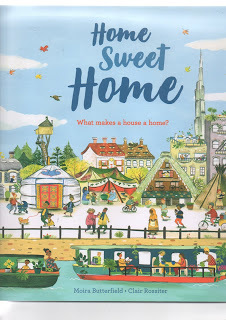

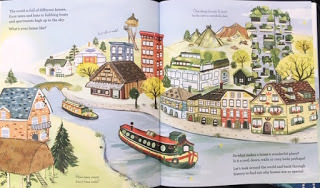

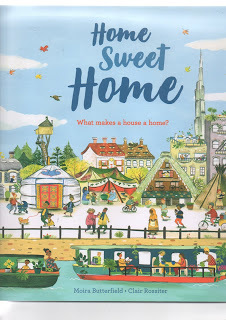

Moira Butterfield was one of our Picture Book Den co-founders, and has recently been writing lots of highly-illustrated non-fiction for age 4+. Her book Welcome to Our World (Nosy Crow)was an international bestseller in 2018. Her new book Home Sweet Home (Red Shed, Egmont)came out at the end of June 2019. In 2020/2021 she will have picture book non-fiction published by Nosy Crow, Walker Books and Quarto.

What is picture book non-fiction? Picture book non-fiction uses the medium of the illustrated picture book to explore real life. It might be for ages 4+, or pitched slightly older at 6+ (as is Home Sweet Home). The text will be paired with the work of an imaginative picture book illustrator.

Moira’s new book – Home Sweet Home.

Moira’s new book – Home Sweet Home.

The text needs to be a great out-loud read Picture book non-fiction text needs to exhibit the same writing skillsets as a storybook. As it is likely to be a shared reading experience between adults and children, the author needs to think hard about the way the book will hold up as a ‘together’ read. Just as you would do with a story, read your work out loud regularly as you write. That way you can catch anything that doesn’t flow well, is long-winded or confusing.

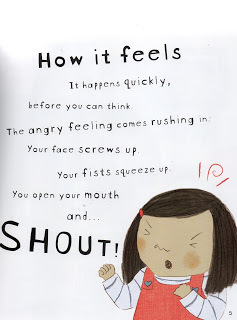

The text might be poetic or caption-based Some non-fiction picture book text is lyrical – using the features of poetry to explore a subject. By contrast, some non-fiction texts use an introduction and short caption facts (as per Home Sweet Home). For instance, lyrical non-fiction about a butterfly might read more like a poem about a butterfly, whereas in a caption-based text you might want to explain – step-by-step - the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly. It should still sound great out loud (and with its meaning as clear as a bell), but it’s not laid out as poetry.

I myself have written both these styles and I’m happy to mix them up in the same book. I think it makes for a good varied read.

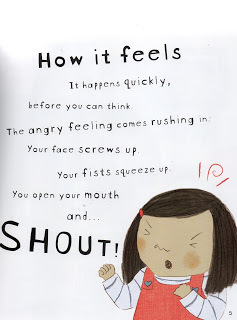

This poem comes from the beginning of ‘Everybody Feels Angry’ (QED, illustrated by Holly Sterling). The book contains a mixture of material exploring a child’s feelings.

This poem comes from the beginning of ‘Everybody Feels Angry’ (QED, illustrated by Holly Sterling). The book contains a mixture of material exploring a child’s feelings.

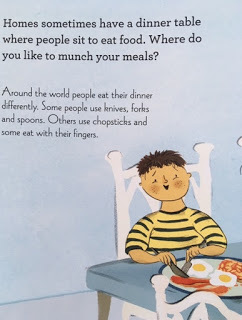

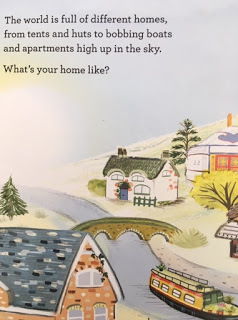

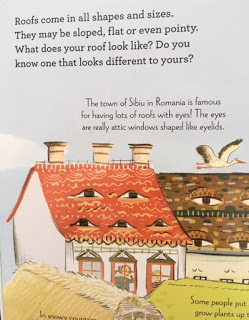

Here’s a snippet from a Home Sweet Home spread.

Here’s a snippet from a Home Sweet Home spread.

It shows an introduction and caption.

Be hyper-aware of the needs of your age-group Be very careful to ensure your text caters to the age-group you’re aiming at. Will they be interested/able to connect with what you are saying and the way you are saying it? For example, a 4 year-old might prefer the poetry approach as a way of accessing a subject. A 6+ year-old might prefer longer content with more caption facts.

The text should have a sense of wonder Most importantly the language of a non-fiction book should impart a sense of wonder in its subject. That’s why picture book non-fiction is such a great genre. We’re getting the chance to spark a child’s interest in the amazing world around them.

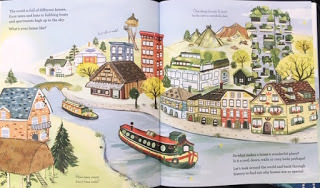

The opening spread of Home Sweet Home, illustrated by Clair Rossiter

The opening spread of Home Sweet Home, illustrated by Clair Rossiter

and written to get children interested in life around the world.

Page length varies Picture book non-fiction may not always follow a 12-spread pattern. I have written for 48pp and longer recently. In fact a publisher has just suggested that I write with no page numbers in mind, which I think is a great idea. The designer will then work on the text to see what comes out. That’s pretty radical and has given me the impetus to be very creative without stricture!

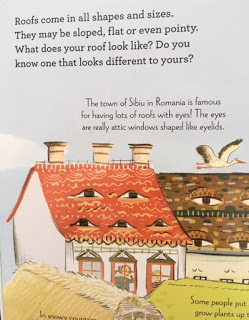

Children need to feel involved A non-fiction picture book text should, in my opinion, connect to the lives of the children who read it. So, for example, Home SweetHomelooks at homes around the world and in history, but with reference to a child’s own experience. I am giving them surprising and (I hope) fascinating facts but making sure I link the information to what they know. In fact, in this case I decided to ask the reader questions as they move through the book – to get them actively connecting themselves to the things they are learning.

First example of including questions -

First example of including questions -

taken from Home Sweet Home.

Second example of including questions -

Second example of including questions -

taken from Home Sweet Home.

The text needs heart Above all, a picture book non-fiction text needs heart, just as a story does. Are you passionate about it? What’s the reason you chose a particular subject? If you have something important to say, then your feeling is more likely to shine through in your work.

www.moirabutterfield.comTwitter @moiraworldInstagram @moirabutterfieldauthor

What is picture book non-fiction? Picture book non-fiction uses the medium of the illustrated picture book to explore real life. It might be for ages 4+, or pitched slightly older at 6+ (as is Home Sweet Home). The text will be paired with the work of an imaginative picture book illustrator.

Moira’s new book – Home Sweet Home.

Moira’s new book – Home Sweet Home.

The text needs to be a great out-loud read Picture book non-fiction text needs to exhibit the same writing skillsets as a storybook. As it is likely to be a shared reading experience between adults and children, the author needs to think hard about the way the book will hold up as a ‘together’ read. Just as you would do with a story, read your work out loud regularly as you write. That way you can catch anything that doesn’t flow well, is long-winded or confusing.

The text might be poetic or caption-based Some non-fiction picture book text is lyrical – using the features of poetry to explore a subject. By contrast, some non-fiction texts use an introduction and short caption facts (as per Home Sweet Home). For instance, lyrical non-fiction about a butterfly might read more like a poem about a butterfly, whereas in a caption-based text you might want to explain – step-by-step - the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly. It should still sound great out loud (and with its meaning as clear as a bell), but it’s not laid out as poetry.

I myself have written both these styles and I’m happy to mix them up in the same book. I think it makes for a good varied read.

This poem comes from the beginning of ‘Everybody Feels Angry’ (QED, illustrated by Holly Sterling). The book contains a mixture of material exploring a child’s feelings.

This poem comes from the beginning of ‘Everybody Feels Angry’ (QED, illustrated by Holly Sterling). The book contains a mixture of material exploring a child’s feelings.  Here’s a snippet from a Home Sweet Home spread.

Here’s a snippet from a Home Sweet Home spread. It shows an introduction and caption.

Be hyper-aware of the needs of your age-group Be very careful to ensure your text caters to the age-group you’re aiming at. Will they be interested/able to connect with what you are saying and the way you are saying it? For example, a 4 year-old might prefer the poetry approach as a way of accessing a subject. A 6+ year-old might prefer longer content with more caption facts.

The text should have a sense of wonder Most importantly the language of a non-fiction book should impart a sense of wonder in its subject. That’s why picture book non-fiction is such a great genre. We’re getting the chance to spark a child’s interest in the amazing world around them.

The opening spread of Home Sweet Home, illustrated by Clair Rossiter

The opening spread of Home Sweet Home, illustrated by Clair Rossiter and written to get children interested in life around the world.

Page length varies Picture book non-fiction may not always follow a 12-spread pattern. I have written for 48pp and longer recently. In fact a publisher has just suggested that I write with no page numbers in mind, which I think is a great idea. The designer will then work on the text to see what comes out. That’s pretty radical and has given me the impetus to be very creative without stricture!

Children need to feel involved A non-fiction picture book text should, in my opinion, connect to the lives of the children who read it. So, for example, Home SweetHomelooks at homes around the world and in history, but with reference to a child’s own experience. I am giving them surprising and (I hope) fascinating facts but making sure I link the information to what they know. In fact, in this case I decided to ask the reader questions as they move through the book – to get them actively connecting themselves to the things they are learning.

First example of including questions -

First example of including questions - taken from Home Sweet Home.

Second example of including questions -

Second example of including questions -taken from Home Sweet Home.

The text needs heart Above all, a picture book non-fiction text needs heart, just as a story does. Are you passionate about it? What’s the reason you chose a particular subject? If you have something important to say, then your feeling is more likely to shine through in your work.

www.moirabutterfield.comTwitter @moiraworldInstagram @moirabutterfieldauthor

Published on July 07, 2019 22:00

July 1, 2019

Protests over picture books: LGBT+ inclusion by Juliet Clare Bell

Many people will have read about the protests outside two primary schools in Birmingham recently, with protesters arguing against the reading and discussing of certain picture books at certain ages in school.

Having been involved with the group SEEDS (Supporting the Education of Equality and Diversity in Schools, set up in the wake of the protests), marching alongside people from the Muslim LGBT+ community at this year’s Pride, meeting in a highly charged setting with our local MP (who has, controversially, backed the protesters, directly at odds with his own party), and as a picture book author and local parent, I’d like to talk about some of the books that are being read in the schools and what appears to have been going on.

No Outsiders Programme

Created by Andrew Moffat, deputy head at Parkfield Community School in Birmingham, No Outsiders is a programme followed in some primary schools, using 35 picture books (five each year from Reception through to Year 6) to help open up discussions about inclusion and equality, alongside all the many other books the children will be reading/have read to them. Here are the picture books deemed controversial by some:

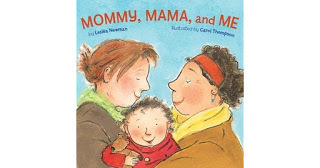

Mommy, Mama and Me (Leslea Newman and Carol Thompson),

(c) Carol Thompson (2009)

King and King (Linda de Haan and Stern Nijland)

(c) Stern Nijland (2002)

And Tango Makes Three (Justin Richardson, Peter Parnell and Henry Cole)

(c) Henry Cole (2015)

and My Princess Boy (Cheryl Kilodavis and Suzanne DeSimone).

(c) Suzanne DeSimone (2011)

In addition to these four books whose main characters/families are in same sex relationships or who do not conform to gender norms, there are two others about families in general which include mention (and pictures) of same sex couples in families alongside many other non LGBT+ families:

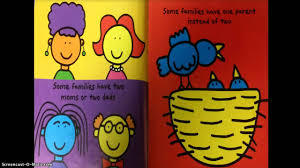

The Family Book by Todd Parr (used with Reception children)

(c) Todd Parr (2010)

(c) Todd Parr (2010)

“Some families have two mums or two dads. Some families have one parent instead of two.”

(c) Todd Parr (2010)

And The Great Big Book of Families , by Mary Hoffman and Ros Asquith (used with Year 2 children)

(c) Ros Asquith (2015)

The book talks about lots of different families before moving on to different homes, holidays, food etc. It’s a beautiful, inclusive book.

"Some children have two mummies or two daddies. And some are adopted or fostered."

(c) Ros Asquith (2015)

But back to the four books that have caused the most controversy. As with so many books for young children, these are about relationships and love. It seems almost absurd to mention it but because of all the misinformation, it’s worth stating that they are in no way whatsoever about sex.

Mommy, Mama and Me (read in Reception, with five- and six-year olds) is about a loving family unit with two parents doing ordinary, everyday things with their child.

(c) Carol Thompson (2009)

“Mommy gently combs my hair. Mama rocks me in her chair”

(c) Carol Thompson (2009)

“Mommy packs a yummy snack. Mama rides me on her back.”

(c) Carol Thompson (2009)

At the end of the simple story, Mommy and Mama kiss the child good night.

That is all. It’s like many other lovely picture books for young children about the important adults in their life.

King and King (Linda de Haan and Stern Nijland is read in Year 4 (with eight- and nine- year-olds).

(c) Stern Nijland (2002)

It’s a fairy tale about a prince whose mother, the Queen, is trying to marry him off to a princess. He’s not interested in any of the princesses she’s lined up for him. Instead, he falls in love with the brother of one of the princesses, and as with many fairy tales: "it was love at first sight":

(c) Stern Nijland (2002)

and the two princes marry instead.

In year 5 (where the children are nine- and ten- years old), And Tango Makes Three is introduced.

(c) Henry Cole (2015)

This is the true story of two male penguins in Central Park Zoo who paired up and eventually (after trying to incubate a stone)

(c) Henry Cole (2015)

were given an egg that needed looking after. They incubated the egg, which hatched successfully and they brought up the baby penguin as their own.

In Year 6, the final year of primary school, where the children are ten and eleven years old, they read (alongside the other books in the No Outsiders programme, and countless other books)

Suzanne DeSimone (2011)

My Princess Boy This is another story of love and acceptance, written by a mother about her son who likes to wear dresses and who is completely loved exactly as he is.

Suzanne DeSimone (2011)

These are the books that have proved so controversial (you can see the full No Outsiders reading list here:) No Outsiders book list

As with the other books on the list (including our own 'Denner's You Choose -Pippa Goodhart and Nick Sharratt, Elmer -David McKee and Red Rockets and Rainbow Jelly -Sue Heap and Nick Sharratt), these books are about acceptance and love, saying that it's ok to be you, showing children that different people like different things.

These books cover protected characteristics in the Equalities Act 2010. It is illegal to discriminate against someone on the grounds of their gender, or gender reassignment, or race or religion, and (with the shocking exception of Northern Ireland) same sex marriage is legal and here and holds equal weight in law with marriage between a man and a woman. This is not controversial subject matter for this country. These books are merely reflecting reality and ensuring, for example, that the many children of two mums can see themselves in a book, and those children without two mums can see that a slightly different family set up is still in many ways similar to their own.

We need to encourage empathy in children, and picture books that reflect the wonderful diversity of the place we live in are crucial. Children need to see themselves and their families, and they need to see other families that are different from their own, in picture books. This includes children of different ethnicities, with disabilities, and families and children from the LGBT+ community. One protected characteristic does not over-ride another. All these characteristics are protected. We don't get to say one should be more protected than another. Our job -and the legal duty of schools- is to protect them all. What better way than introducing them in attractive picture books that are engaging and welcoming?

And yet we are witnessing some very uncomfortable scenes, far removed from the loving and accepting nature of these books...

Anderton Park School (one of our local schools) currently has an exclusion zone around it so that children and staff are not intimidated and/or frightened by the protesters who were standing outside at the end of the school day, chanting. Having been banned from outside the school, the protesters are now protesting slightly further away outside the exclusion zone, though on some days their shouting can still be heard near the school. When a group of us from SEEDS went to our local MP’s surgery to talk with him about his views on the age-appropriateness of these picture books, the police were out in force to ensure our safety. This was at an MP surgery session – to talk about the picture books mentioned above. These are books about acceptance and love.

Sarah Hewitt-Clarkson, the head teacher, said last week at a meeting on Defending Equalities, that this protest has “at times, crushed my soul”. She said how she loves that it is her duty as head teacher, to foster relationships between those people with protected characteristics (under the Equalities Act 2010) and those without, and that equality is woven “into everything we do”, and that although the ongoing protest “has broken our hearts,… we are not broken because Anderton Park is built on equality”. Anderton Park School doesn’t follow the No Outsiders programme. They use many hundreds of books throughout school including some of the same books mentioned above (Mommy, Mama and Me; My Princess Boy, and And Tango Makes Three). She said at the meeting that they didn’t have consultation with the parents about using those specific books in school because they are doing nothing different from what they are always doing –teaching acceptance and equality.

There has been so much misinformation about the books being used in schools. I do not want to write too much about the protesters as I do think that the story has been manipulated by the media to make it look like it’s a more generalised problem than it is. The vast majority of schools are not experiencing these problems -including the vast majority of schools in Birmingham. But for anyone who is interested, it is really worth watching the statement made by Nazir Afzal, former Chief Crown Prosecutor for North West England, who was brought in to try and mediate between Anderton Park School and the protesters:

Nazir Afzal's comments on the protests

In the Gender Equalities meeting last week, MP for the nearby constituency of Birmingham, Yardley, Jess Phillips, talked about her concern and upset about the misrepresentation in the press of these protests. Although she was filmed challenging the main protester (who is not actually a parent of anyone at the school), she wanted to point out that in her own nearby constituency with approximately 40% of constituents of Bangladeshi- and Pakistani- origin, not a single person has mentioned it to her. This is simply not the fight that is most important to most people, she said, and she hates that it has been portrayed as such in the media. Many Muslims in the UK have experienced an increase in Islamophobia and general racism in recent years and are feeling vulnerable. Many people in the LGBT+ community are also feeling vulnerable at the moment. Those who are LGBT+ within the Muslim community are some of the most vulnerable. We are living in very uncertain times politically. If people felt less marginalised, there would be easier dialogue and discussions and considerably less likelihood of outside parties managing to spread misinformation. Let’s work together –as writers, humans, parents, neighbours, teachers, citizens to ensure that we don’t choose one protected characteristic over another -that we fight racism, Islamophobia, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, discrimination against those with disabilities together. As picture book writers, let us keep writing books that encourage empathy, with diverse characters so that everyone can feel seen, and publishers, let us see more diverse writers and illustrators being published and greater authentic diversity in our picture books. Let's be less defensive and willing to have difficult conversations and be open to making mistakes along the way, and allowing others to make mistakes along the way as we try to celebrate diversity in all its richness. But one thing is clear: showing diversity in books should not be a debate. And nor should sharing those books with young children. It should be our duty.

Juliet Clare Bell is a picture book author, whose next picture book (which she will be able to announce soon) is due for release in 2020. Her experience of doing author visits in schools in this area has been overwhelmingly positive and still believes that this is solvable. Love, ultimately, will win.

www.julietclarebell.com

Please feel free to comment, below. Many thanks.

Published on July 01, 2019 16:24

June 23, 2019

What I wish I'd known... by Jane Clarke

It’s my 20 year anniversary as a published writer - a poem in Tony Bradman’s anthology appeared in 1999, and my first picture book text was accepted in June that year, (though not published until 2001).

So here are a few things I wish I’d known when I hit my 40s, and started to write…

It’s not the end of the world if your story is rejected. Rejections are part of a writer’s life. Go for a walk, have a cup of tea - and get on with writing another story.

Self edit more. Don’t finish writing a text and send it straight off. Stick it in a folder and leave it for a while, then get it out and have another look.

These days, most of my files are on the computer but I still have to fight off the urge to send off stuff prematurely.Get someone else to read what you have written. Join The Society of Children's Book Writer's and Illustrators. A good critique group is a much better source of useful writing advice than bribed teenagers.

These days, most of my files are on the computer but I still have to fight off the urge to send off stuff prematurely.Get someone else to read what you have written. Join The Society of Children's Book Writer's and Illustrators. A good critique group is a much better source of useful writing advice than bribed teenagers.

Mug shots of hairy teenagers at age of bribery. Fear not, they both turned into wonderful adults (and fathers).During harrowing times, don’t add to your stress by wondering if you will ever be able to again. You will.

Celebrate every significant writing moment (even finishing a story that you suspect will go on to be rejected). They’re great excuses for cake!

Jane’s also discovered that if you write a book about a shark, you tend to accumulate shark-related items. Gilbert the Great illustrated by Charles Fuge.

Jane’s also discovered that if you write a book about a shark, you tend to accumulate shark-related items. Gilbert the Great illustrated by Charles Fuge.

So here are a few things I wish I’d known when I hit my 40s, and started to write…

It’s not the end of the world if your story is rejected. Rejections are part of a writer’s life. Go for a walk, have a cup of tea - and get on with writing another story.

Self edit more. Don’t finish writing a text and send it straight off. Stick it in a folder and leave it for a while, then get it out and have another look.

These days, most of my files are on the computer but I still have to fight off the urge to send off stuff prematurely.Get someone else to read what you have written. Join The Society of Children's Book Writer's and Illustrators. A good critique group is a much better source of useful writing advice than bribed teenagers.

These days, most of my files are on the computer but I still have to fight off the urge to send off stuff prematurely.Get someone else to read what you have written. Join The Society of Children's Book Writer's and Illustrators. A good critique group is a much better source of useful writing advice than bribed teenagers.

Mug shots of hairy teenagers at age of bribery. Fear not, they both turned into wonderful adults (and fathers).During harrowing times, don’t add to your stress by wondering if you will ever be able to again. You will.

Celebrate every significant writing moment (even finishing a story that you suspect will go on to be rejected). They’re great excuses for cake!

Jane’s also discovered that if you write a book about a shark, you tend to accumulate shark-related items. Gilbert the Great illustrated by Charles Fuge.

Jane’s also discovered that if you write a book about a shark, you tend to accumulate shark-related items. Gilbert the Great illustrated by Charles Fuge.

Published on June 23, 2019 22:30

June 16, 2019

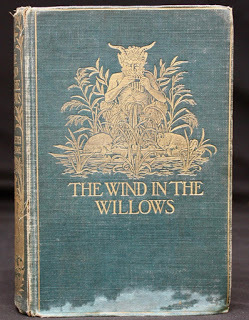

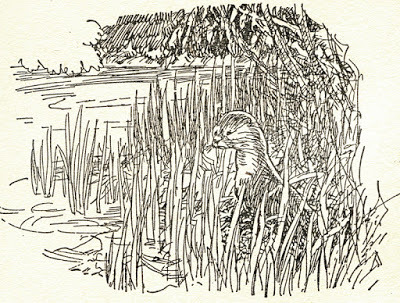

Tales from the riverbank – a wander into the world of Wind in the Willows with Mini Grey

As a child I watched far too much TV. There was a show called Tales of the Riverbank. The stars of the films were real animals, who were shown moving around in miniature boats, cars, balloons and aeroplanes. I loved seeing rodents rushing downstream in rickety water-crafts.

As a child I watched far too much TV. There was a show called Tales of the Riverbank. The stars of the films were real animals, who were shown moving around in miniature boats, cars, balloons and aeroplanes. I loved seeing rodents rushing downstream in rickety water-crafts.

I live near the river in Oxford, and there’s nothing I’d be so excited to see as a water-vole rowing a tiny boat down the Thames.

I live near the river in Oxford, and there’s nothing I’d be so excited to see as a water-vole rowing a tiny boat down the Thames.

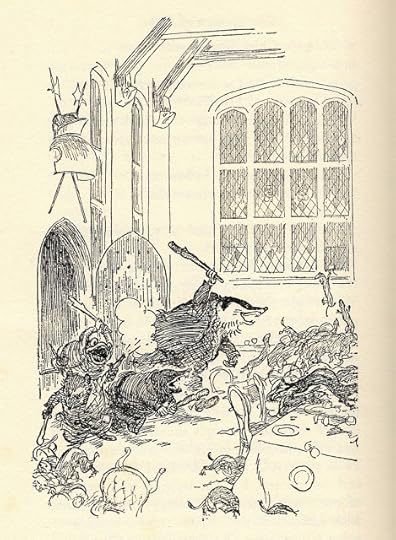

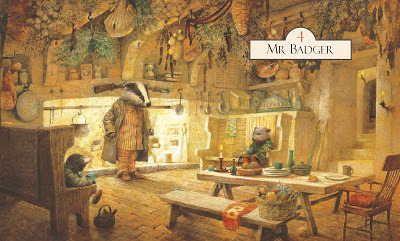

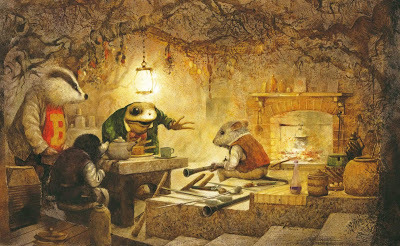

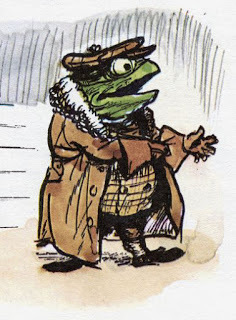

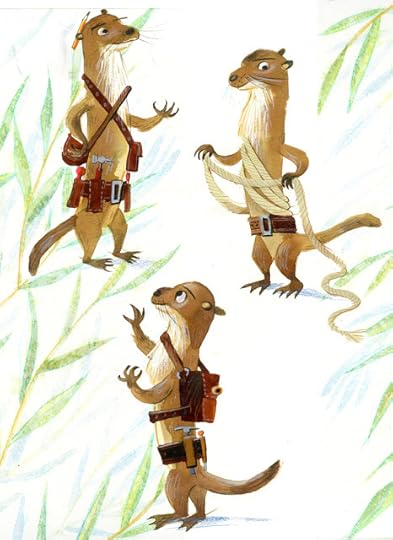

The original messing about in boats is of course in The Wind in the Willows. And I’ve recently finished making the illustrations for a story set slap-bang in Wind in the Willows territory, so in this post I’m going to have a look at Kenneth Graham’s book and some of its illustrators. I want to consider the challenges of illustrating in the Willows Zone, and how the Willows, the most comfortingly nostalgic of books, was actually shivering with premonitions of the modern world.

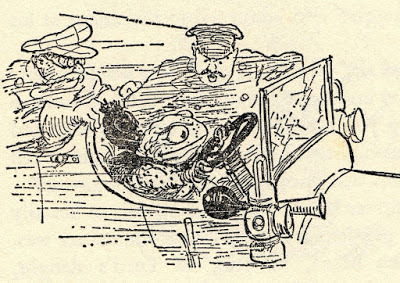

The book was published in 1908, but it wasn’t until 1931 that EH Shepard illustrated it. To me EH Shepard’s pictures are as much a part of Wind in the Willows as the text – so I was surprised to discover they weren’t there at the beginning.Grahame didn't live long enough to see the book released with Shepard's illustrations, but their meeting would be reported by Shepard in a 1950s edition of the classic, as follows:

"Not sure about his new illustrator of his book, he listened patiently while I told him what I hoped to do.Grahame was living in Pangbourne near the Thames – and at other times he lived in Cookham, also on the River Thames – so to me, the river running through the book is always the Thames - which bubbles up in Gloucestershire and flows through Oxford, Reading, Henley and Windsor and eventually becomes the great river that snakes through London on its way to the sea. Mole, on his escape from white-washing, is captivated by the river; it “chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.”

Then he said 'I love these little people, be kind to them'.

Just that; but sitting forward in his chair, resting upon the arms, his fine handsome head turned aside, looking like some ancient Viking, warming, he told me of the river nearby, of the meadows where mole broke ground that spring morning, of the banks where Rat had his house, of the pool where Otter hid, and of Wild Wood way up on the hill above the river.EH Shepard

...He would like, he said, to go with me to show me the river bank that he knew so well, '...but now I cannot walk so far and you must find your way alone'."

EH Shepard

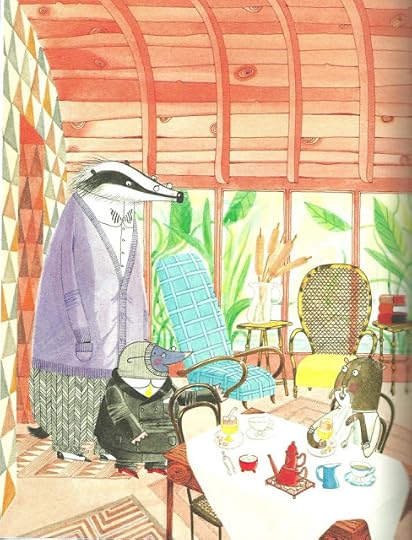

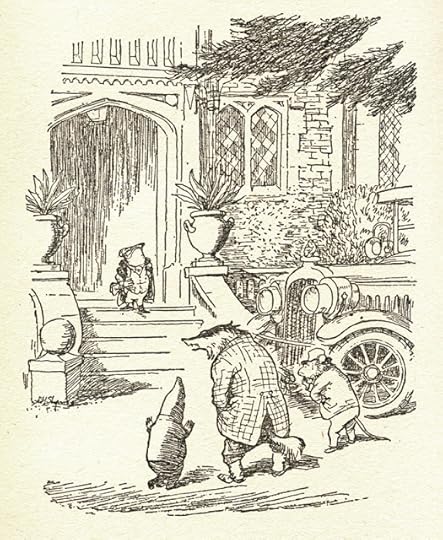

EH ShepardThe Wind in the Willows has been rich ground for re-illustration. To me EH Shepard’s illustrations are part of its fabric, like Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice, but still both books are big enough to inspire reinvention. And so far, in all the versions I’ve seen, the animals are wearing clothes.

Animals in Clothes