Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 16

June 20, 2021

Picture books about Dads. Garry Parsons chooses picture books to celebrate fatherhood all year round.

One of my favourite depictions of fatherhood is the moment Geppetto lifts Pinocchio off the floor and joyfully whirls him around the room at the end of the Disney movie. This is the very last scene in the movie where distraught Geppetto is sobbing on the bed and all looks lost. But when he lifts his head to see who’s talking he realises that Pinocchio is not only alive after the ordeal with the whale but has magically been transformed into a real boy.

Pinocchio - Disney 1940

Pinocchio - Disney 1940I’m sure we’d all agree that Geppetto’s parenting skills in the movie require some attention but what I love about that final scene is the overwhelming sense of joy Geppetto has at being a father and the relief he has to be reunited with his son. You can watch the scene on youtube here.

Like Geppetto, no one is perfect at being a parent and nor would we want to be, but Dads in picture books often seem to get a raw deal. Dads are often depicted as caricatures of dads, preoccupied with tasks in the shed, washing the car or tinkering under the bonnet. Sometimes unkempt or dishevelled, they can appear absent minded, aloof or uncaring, preferring to fix things than parent directly.

Dads generally appear less in picture books than mums too and are more likely to play background roles. There are certainly more mums in picture books than dads but that is probably a fair representation of who is taking on most of the full time parenting today, particularly with books for younger children. Dads in picture books can be on the periphery of family life or simply absent from the story altogether, but that might also be a reflection on the world we live in too.

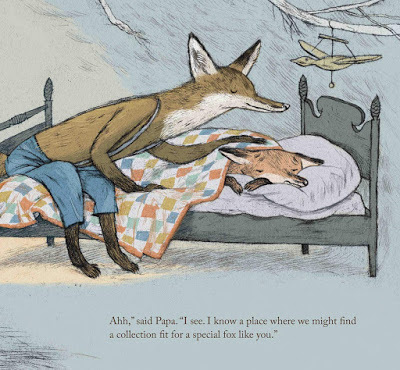

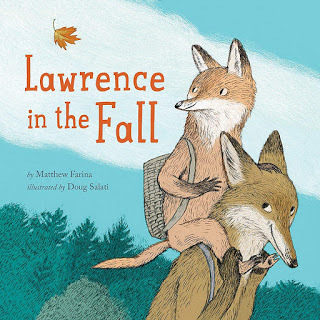

From Lawrence in the Fall by Matthew Farina & Doug Salati

From Lawrence in the Fall by Matthew Farina & Doug SalatiSo it’s heart-warming to see some new Dad characters coming to the fore in recent picture books. Dads who care and parent from a place of nurture (“Lawrence in the Fall”) and dads who are gentle and willing to listen (“Jabari Jumps”) And dads who are keen to impart wisdom and help their children grow.

What We’ll Build by Oliver Jeffers

What We’ll Build by Oliver Jeffers As it is Father’s Day this weekend we have good reason to delve back into the book shelf and pull out some old favourites too.

Don’t Let Go! By Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross.

Don’t Let Go! By Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross.I’ve picked out a few picture books with strong father figure characters who, I feel, have a lot to give and that you might enjoy too.

Lawrence and his Papa go searching in the woods to collect things to show in school. Papa gently departs his knowledge of the forest and his wisdom of how the world works. In a moment when they become separated, Lawrence discovers a forest secret of his own. A tender story of the bond between father and son where the characters express clear emotion, beautifully illustrated scenes and characters that capture the tenderness and wild elements of the landscape.

What We’ll Build by Oliver Jeffers is a story of a father and daughter setting out plans for their life together, building memories and a home to keep them safe. A moving story of love and protection.

A story about courage and gentle parental encouragement. Jabari has made his mind up that he is going to take a leap from the diving board but it's high and a little scary but he has his dad with him for support.

Pete’s A Pizza by William Steig is a firm favourite in our house and never ceases to bring a smile. It's raining outside and Pete can't go outside to play. Pete's attentive dad decides to make him into a pizza instead and bake him on the sofa. A funny and warm story around the kindness of a tuned-in dad with paired-down but spot-on illustrations.

A Brave Bear is a contemplative story of gentle parenting and attentive awareness. Dad has to navigate encouragement and some sulking when his son has ambitions of jumping big and grazes his knee in the wilds of the forest. Beautiful, textured illustrations from Emily Hughes.

Another enduring favourite in our house is Don’t Let Go! By Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross. A little girl wants to visit her daddy but to do that she needs his help to learn to ride her bike. "Daddy, I'm here, I won't let go. Not until you say. Hold on tight. I love you, so - We'll do this together...OK?" Prepare to be moved by this affectionate father and daughter relationship.

Great for younger readers, My Daddy is a Giant is a simple celebration of a father with Indrid Godon's uniquely wonderful illustrations.

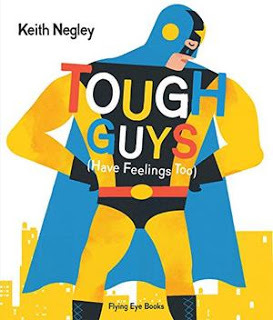

Stereotypically manly men are shown in emotional or scary moments in Tough Guys (Have Feeling Too) by Keith Negly. Evertone has feelings, unless you are a robot!

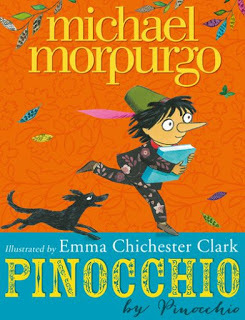

And to return to Geppetto and his son, Pinocchio by Pinocchio, retold by Michael Morpurgo, illustrated by Emma Chichester Clark

As ever, please use the comments section to recommend your favourites and let’s celebrate the fully formed Dad in picture books all year round. Happy Fathers Day!

***

Garry Parsons is an award winning illustrator of children’s books and father to two boys.

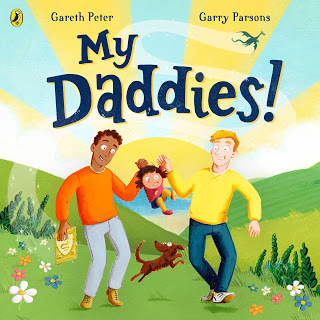

Garry is the illustrator of My Daddies! By Gareth Peter.

@icandrawdinos www.garryparsons.co.uk

June 13, 2021

PERFORMING PICTURE BOOKS

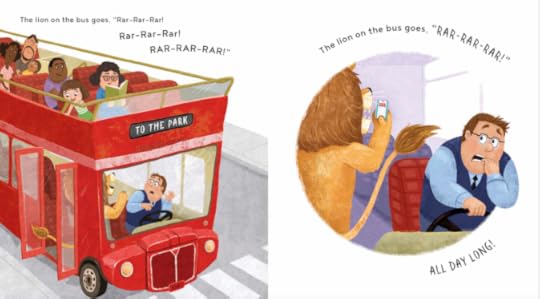

My fourth picture book is published on 24th June. The Lion on the Bus is illustrated by Jeff Harter and follows an eventful bus journey through the eyes of a little girl happily singing ‘The Wheels on the Bus.’ When she spots a lion get on, she sings:

Her mother is lost in a book and oblivious to the fact that her daughter's song is describing what is happening around her - as yet more ferocious animals board the bus, eventually taking the passengers hostage! Don't worry. It's all right in the end.

I came up with the idea for this book when I was singing The Wheels on the Bus with my daughter and one of us (we don't agree on which one) started singing The Lion on the Bus goes RAR RAR RAR!

I wondered what a lion would be doing on a bus then wrote this book to answer that question.

While most picture books are designed to be read aloud, this one is designed to be sung so requires some level of performance.

As the author, I am dying to get out and perform this book. I find that picture books come to life through performance in ways that often surprises and intrigues me. I often learn something new about my own books when I read them in public, because it allows me to see them through my audience's eyes.

When I’m writing a picture book, I will read it aloud countless times to ensure that the words trip off the tongue, rather than the tongue tripping over the words, but reading a book to an audience is an entirely different experience.

With 3 picture books out this year, I can't wait for the return of school visits, festival shows and library events. Happily, I've got a few lined up so I've been reminding myself of the important things to remember when performing a picture book. 1. EVERY PERFORMANCE IS A REHEARSAL

You can practice reading your book in advance all you like but you won't be able to properly rehearse it until you have an audience in front of you (no matter how small). For me, it takes a good 5 or 6 public readings before I have properly learned how to perform one of my books. Even after 50 performances, I still discover new ways to improve the reading - and quite often these ideas come from the audience.

2. KNOW THE BOOK, SHOW THE BOOK

The best readings (especially of picture books) don’t actually involve much reading. With a new picture book, I might still be reading the words for the first few performances, but eventually these words get ingrained in my head like the lyrics of a song and this means I can focus on all the other aspects of the performance. It also means I can hold the book so that the audience can see the pictures.

3. ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER

With my first picture book, The Dinosaurs are Having a Party (illustrated by Garry Parsons) I get the audience to roar a lot and, at one point to throw tantrum, shouting, "It's not fair and nobody cares!" In Are You the Pirate Captain? (also with Garry) I have them hammering nails, chipping off snails and swabbing the decks. With Rabunzel (illustrated by Loretta Schauer) I have discovered that the audience love to bring the hungry eyes creatures to life with growls howl, hisses and eagle screeches - although mine often sound more like seagull squawks. I don't think about these interactive elements when I'm writing the books. Nor when I'm commenting on the illustrations. I usually discover them through the performance itself.

4. ENGAGE AND CONNECT

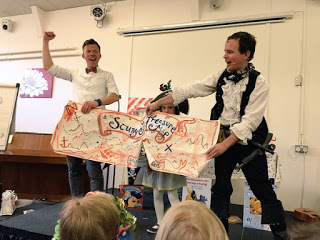

The more engagement, the better when it comes to reading books in schools. The more you can keep the audience involved the less chance you give them to wriggle about and get distracted. Don’t be afraid to stop and ask a question or add in a funny aside. Or maybe you have a puppet. Or a prop like this treasure map that Garry made. Or a song. Whatever you can do to make the reading more than a reading will really help hold your audience's attention.

5. ALLS WELL THAT END'S WELL

No matter how clear it is to you that your beautifully composed conclusion signifies the end of the book, your audience may not realise it's over. Perhaps you can indicate it's the end with an emphatic closing of the final page. Or maybe you have a song to finish with. Or is there a repeated phrase or action that the audience can join in with that will let them know it's all done? It’s worth thinking about because, although it is perfectly fine to end with the words “And that’s the end of this book,” there will always be a more satisfying way to conclude.

And that’s the end of this blog.

Gareth P Jones’ new book The Lion on the Bus is illustrated by Jeff Harper and published by Farshore Books. You can see him talking (and singing) about the book on 24th June at Moon Lane TV. He is appearing at Camp Bestival & Latitude this summer and is currently taking bookings for school visits, library events and festivals.

June 6, 2021

28 Creatives and What Inspires Them To Write and Draw (Plus a MEGA GIVEAWAY!)

What inspires you to be creative? The publishing industry is pitted with challenges and obstacles, a lot of which are out of our control, which means it's even more important to keep WHY we create at the forefront of our minds.

In today's Picture Book Den post you'll hear from 28 picture book creators about what helps the words flow, the ideas strike, AND what keeps them going through hard times.

CLARE HELEN WELSH:

Being creative makes me feel good. In particular, I find writing a very mindful activity, allowing me to process what’s buzzing around my head, either in a conscious or unconscious way. Of course, there are times when writing can be hugely frustrating, but the breakthrough moments make it worthwhile. As well as the personal gains, I also write for others - be that my own children, children I've taught, my godchildren or those I've yet to meet. It makes me very happy to think of my books bringing something special to bedtimes, difficult times and lesson times. I often aspire to write books I would have used if I were still teaching myself. Keeping these internal and external gains close at heart, helps me through the ups and downs.

LUCY ROWLAND:

'I write because it's such an amazing feeling to watch a little seed of an idea grow into a whole book which can be enjoyed by children and families. I am inspired to write when something crosses my mind and makes me think 'Now, who might need a story about that?' That's why I wrote Wanda's Words Got Stuck.'

EMMA REYNOLDS:

For my picture books, words and pictures come together. Often I'll start with a character that sparks something special, and then I will write a story about them. I'm inspired by nature and saving it, imagination and the magic found in the everyday, and making books about kindness.

KAREN SWANN:

I write because I have stories in my head that I want to tell, in a way that only I can tell them. I keep writing because there are always more stories that need to be told.

KATE THOMPSON :

As writers we have the power to transform a blank sheet of paper into something that will empower, reassure, or simply entertain children (and hopefully their grownups) - it's a pretty amazing super power! I can’t control what happens to my manuscripts once they’re out in the world, but I’ll keep writing as long as I have stories and characters in my head that need to be created.

FIONA BARKER :

I started writing as a bit of a challenge, sort of to see if I could do it. I found out there was a lot to learn and I’ve been trying to get it right ever since! It’s so satisfying to start with an idea or a character and build a story around them.

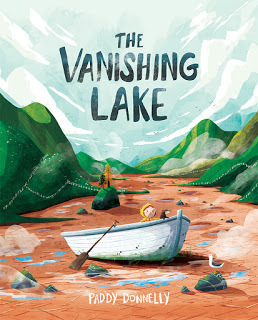

PADDY DONNELLY:

I write stories that I want to illustrate. I build in all of the things that fascinated me as a child, and I love that creative process of crafting words and images simultaneously to form one story. It was an extra special treat that my debut author illustrated picture book was based on a real disappearing and reappearing lake near my hometown in Ireland. Getting to share a little piece of magic from home in my stories is definitely a motivating factor for me.

CATHERINE EMMETT:

I write because I’ve started to realise that I can’t ‘not’ write! There are too many voices in my head that demand attention. Often, I can find myself a bit distracted with life and realise that I haven’t written anything for a while. When I’m writing a picture book and it’s going well, I have a huge sense of contentment and satisfaction – I find something in the process of constructing a story (particularly rhymers) is very calming. When writing is going well, everything else goes well!

EMILY DAVISON:

My brain is bursting with ideas, which is what keeps me going with my writing! I’m always so excited when a new idea POPS into my head!! The chance that one of these ideas may actually make it onto a shelf and bring joy and excitement to children, absolutely blows my mind. I feel very lucky that in 2022, my debut picture book will be making its BIG entrance into the world and I can’t wait to reveal more about it in the coming months.

RACHAEL DAVIS:

Three things inspire me to write: my mum, my children and books! I first started writing as a way to channel my emotions when my mum got sick. After having my daughters, I was blown away by the incredible range of children’s books being published, and it made me want to try to write my own stories. But I also began to reflect on the fact that growing up I never saw myself in children’s fiction. Representation in children’s books still has a long way to go, but I’m hoping that I can be a tiny part of the solution and I’m really excited to share my debut picture book with the world in 2022.

MEREDITH VIGH:

Inspiration can come from anywhere - things my children say, something I saw online, a random title that pops into my head or a verse of rhyme that appears seemingly from nowhere. Sometimes a germ of an idea hovers on the edge of my brain and needs teasing out to become fully formed. Generally, for me to write I must feel excited by a project, but there have been occasions where I’ve forced through a block and ended up creating some of my best work. I write because I can’t NOT write. Each story is a challenge - but writing is FUN! And to create something lovely for children in a world that is so often ugly feels like a worthwhile thing to do.

FRANCES STICKLEY:

I’m a bit of a compulsive daydreamer, and I always have been. I never really stopped escaping into my head and I like to furnish my worlds with all the little details and all the character nuances so I would imagine that’s what made me want to write it all down. I started writing poetry when I was 6; It was a poem about my Dad’s milk float getting stuck in the snow. They do say that, if you’re a writer, you write for the age-group you were when you first fell in love with stories, so I wonder if that’s perhaps when it happened for me.

LEONIE ROBERTS:

I write despite numerous rejections because when I am writing, editing or coming up with new ideas, that's when I am at my happiest. Nothing else gives me this sense of bliss. So, even if I don't write for months or need to take a break from the rejections, I always go back to it. I feel it's important to do what you love.

DONNA DAVID:

I write because you can stay in your pajamas all day and 'work' in bed. I write because you can secretly be watching YouTube whilst everyone thinks you're working. I write because there are no colleagues to judge you for having a family size bag of Maltesers for lunch (again). What's not to love?

SUSANNAH LLOYD :

I was a late starter to writing. It took me until I was nearly forty to realise that I should begin writing, but now I’m making up for lost time. Now I think that, even in all those years when I didn’t write a thing, and even though I didn’t know it, I was always a picture book writer deep down. I always loved picture books with an almost religious reverence, and whenever I read a sentence than really shone, I used to think “I really wish I had written that!”

Ideas tend to float into my head unannounced when I’m far from my desk, and occupied with other things. I gather up little stacks of random notes that I’ve made on scraps of paper, the backs of soap packets and crumpled up bun wrappers... and try to turn them into a story.

LAURA BAKER :

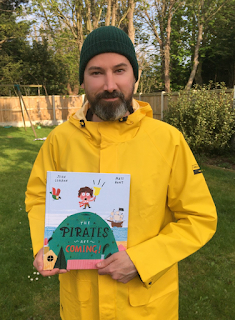

I write because of the magic and power of books. For me a book isn’t simply a story. It’s a memory, and a shared experience. It’s the feeling of reading with a grown-up, or a group, or a special sibling or friend, over and over – a feeling that sticks with you. I grew up loving Dogger, so I’m all about finding stories in the real situations of children. I enjoy picking up on little phrases or actions that kids say or do and making more out of them. I love peeking into a child’s world and seeing where it can take you – and where it can take them. Most recently, my picture book favourite and inspiration has to be John Condon and Matt Hunt’s The Pirates are Coming! – a retelling with humour, heart and TWO twists. What more could you strive for?

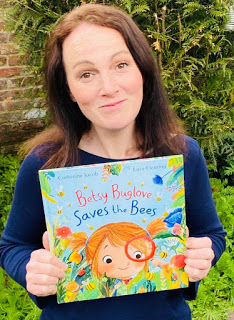

CATHERINE JACOB:

I’m inspired to write by my children. Betsy Buglove is based on my eldest daughter, who’s a real nature lover. I first wrote a Betsy story when she was five years old and would always be found looking under rocks, naming families of woodlice, or saving bees and butterflies from peril on pavements. It’s the same with many of my books: they all start the seed of an idea that might entertain my three children (4, 9 and 11) or sometimes, that comes up in a game they’re playing, and it goes from there. I write when inspiration strikes, which can often be in the most unusual place, particularly, for some reason, while driving long distances!

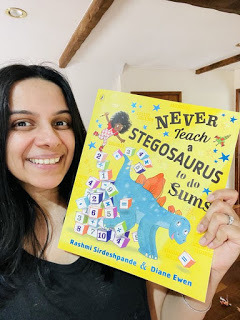

RASHMI SIRDESHPANDE:

I write for children because they're so curious and so full of hope and wonder. I write to make them smile, laugh, feel, think, and dream. And I write for me. Because it feels right. Because it feels like I've found My Thing.

JANE CLARKE:

I write because I've always enjoyed telling stories. I loved making up funny bedtime stories for my sons when they were small. When I worked in a school library, I took requests (the first was for a little girl called Jasmine, who wanted a story about a Princess, a rabbit and shopping). It was the teachers who told me I had to write them down! It gives me enormous pleasure to think that now lots of children can enjoy them.

NATASCHA BIEBOW:

I love to write! I am always writing even when I'm not. I see ideas for stories everywhere. I challenge myself to learn one new fact every day - chances are there's a story there and, sometimes, even a book. Our world is filled with wonder and seeing it with the kind of curiosity that is inate to children is a special thing to keep hold of. I love being able to capture that magic on the page by making books and sharing it with young readers. The books I am making now are true stories – they read like storybooks but they are 100% fact. I love doing all the research, learning new facts and the process of finding and shaping the STORY. Sometimes, it's hard work that takes so much time and perseverance, but when it comes together, you have this amazing colourful piece of work that you can share with kids and grown-ups and that is really special.

JOHN CONDON:

What inspires me to write is the joy of bringing a character to life and sending them off on an adventure. And the hope that this character will some day take a child on that adventure with them.

GARETH P JONES

GARETH P JONES

I write for different reasons: to discover something, because I want to find out what happens next or because I just want to play with an idea. I find picture books the hardest thing to write because thinking visually doesn't come very naturally to me, but when I do get one off the ground I love the collaboration with illustrators and I love how the end result is something I could never do on my own.

LEISA STEWART-SHARPE:

I write non fiction and picture books about the natural world and its strange and wonderful creatures. By telling their stories, I hope to inspire young people to take an interest in our wonderful world and the amazing plants and animals we share it with.

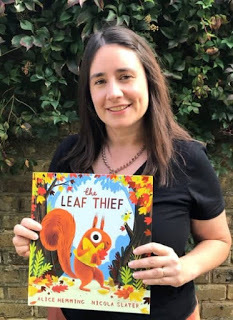

ALICE HEMMING:

For me, writing is my creative outlet, my therapy and, happily, how I earn a living. In hard times it's the writing itself that keeps me going, along with the support of friends and family, yoga, and cake.

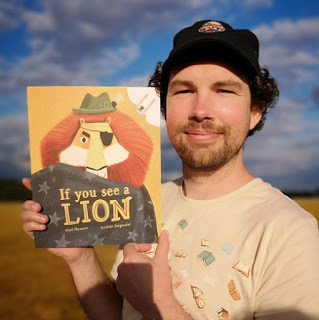

KARL NEWSON:

Why I write? Well, naturally,like a fish in the sky,or a bird in the sea, it's just a thing that happens to mewhile I'm busy dunking biscuits.

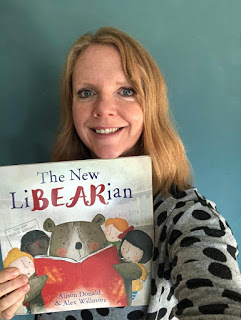

ALISON DONALD:

All children's authors are big kids at heart and I'm no exception! I love to put myself in the shoes of a child and to write a story from their point of view. I hope that my books will be an escape for kids - especially during difficult times. The thing that keeps me going is that I genuinely love to write. I try to focus on the enjoyment I get from writing rather than focusing on publishing deals. If I'm enjoying what I'm doing, it comes through in my writing.

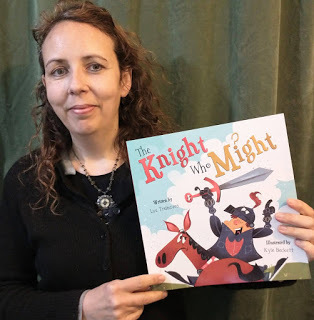

LOU TRELEAVEN

love creating imaginary worlds just from some black and white text on a page - it's such a magical process. I also love seeing a book come to life and all the stages in between. To be a part of that journey is such a thrill.

What keeps me going through hard times: writing, reading, and my family and pets. Being able to escape into imagination is a great resource.

NATELLE QUEK:

I communicate with people through art. It's something that's always a constant in my life and I feel like I can put thoughts and emotions through illustration that are quite difficult for me to convey otherwise. I hope to create stories that connect people to each other, that offer tiny worlds to escape to, that resonate with someone enough for them to create memories that they can carry with them for many years to come.

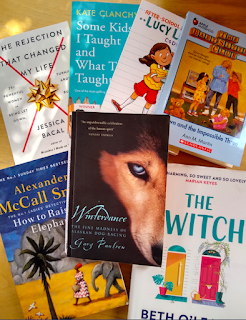

To enter this MEGA GIVEAWAY, winning a copy of all the books pictured above, simply leave a comment at the bottom of this post and we'll pick a winner at random. Closes midnight 13th June. (UK Only)

Titles include:

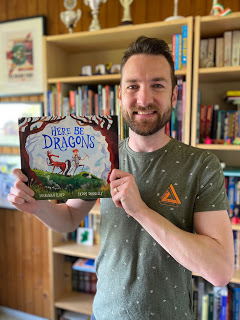

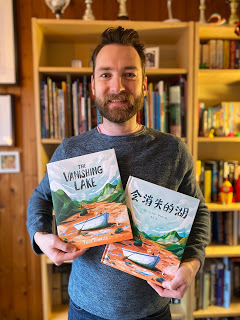

Amelie and the Great Outdoors - Fiona Barker and Rosie BrooksAmara and the Bats - Emma Reynolds (will be posted in July)Betsy Buglove Saves the Bees - Catherine Jacob and *8 (will be posted in July)Blue Planet 2 - Leisa Stewart- Sharpe and Amy DoveDanny and the Dream Dog- Fiona Barker and Howard GrayFirefly Home - Jane Clarke and Britta TeckentrupHere Be Dragons - Susannah Lloyd and Paddy DonnellyIf You See a Lion - Karl Newson and Adrean StegmaierLove You Always - Frances Stickley and Migy BlancoOh no, Bobo! - Donna David and Laura WatkinsMy Colourful Chameleon - Leonie Roberts and Mike ByrneNever Teach a Stegasaurus to Do Sums - Rashmi Sirdeshpande and Diane EwenSetusko and the Song of the Sea - Fiona Barker and Howard GraySuperheroes Don't Get Scared - Kate Thompson and Clare ElsomThe Colour of Happy - Laura Baker and Angie RozelaarThe Knight Who Might - Lou Treleaven and Kyle BeckettThe Leaf Theif - Alice Hemming and Nicola SlaterThe Little Mermaid - Natelle Quek and Anna KempThe Perfect Shelter - Clare Helen Welsh and Asa GillandThe Pet - Catherine Emmett and David TazzymanThe Pirates Are Coming - John Condon and Matt HuntThe Tale of the Whale - Karen Swann and PacmandaraThe Vanishing Lake - Paddy DonnellyWanda's Words Got Stuck - Lucy Rowland and Paula BowlesWhat will you dream of tonight? - Frances Stickley and Anuska Allepuz The Crayon Man: The True Story of the Invention of Crayola Crayons - Natascha Biebow and Steven Salerno

May 23, 2021

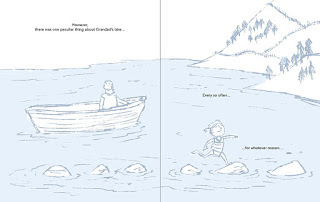

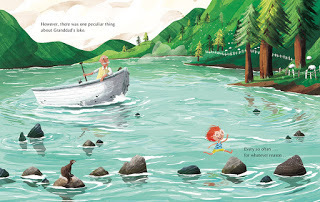

Making It Up As You Go Along by Paddy Donnelly

This week we invited guest author-illustrator Paddy Donnelly to talk to us about creating his new picture book The Vanishing Lake, published by Yeehoo Press.

I’m always fascinated to hear how other authors and illustrators’ put the pieces of their picture books together. There can be a variety of methods each person implements, and each process differs wildly. No matter how many interviews I listen to, or articles I read, every creator seems to follow a different path towards their goal. There is one thing they all have in common though. They made that process up, and are still making it up.

There’s no such thing as a perfect ‘process’ and no two picture book projects follow the exact same set of steps to completion. Writing and illustrating are quite unpredictable tasks - filled with floods of inspiration as well as creative droughts. Challenges appear, feedback can be surprising and you can most definitely find yourself painted into a corner. What’s important to remember is that everyone, no matter how successful they are, also experience all of these things on each project. It’s how you react to them that spurs you towards success.

When starting out in this industry, I would view people who were successful as those who’d ‘figured it out’. They’d discovered the magic formula for putting together a bestseller. However the longer I worked as an illustrator and author, the more I discovered the common truths that link everyone together. Everyone is full of doubts. Everyone has made many mistakes. Everyone has been surprised when something became a ‘hit’. And everyone has a dream story idea that nobody has picked up (yet!). It was reassuring to hear that successful authors and illustrators also took very rambling paths towards where they are today. Nobody in fact has really figured ‘it’ out. And there’s not really an ‘it’ to figure out. Realising this, and combining it with some advice from my old university lecturer - ‘Just say yes and figure it out later’, has definitely brought many enjoyable opportunities my way.

I first got into children’s publishing in 2018, and in the beginning I had no clue how all the different parts of the publishing machine worked, what publishers like to see in a portfolio, what an agent does or how to create an effective page turn. I tried to soak up as much knowledge as I could, and while there are many ‘guidelines’ to working in picture books, they are simply that - ‘guidelines’. All these ‘rules’ can be broken. There’s always a first time for everything. And you can absolutely change your way of working, or completely switch up your illustration style, or write in another genre. Nothing is set in stone.

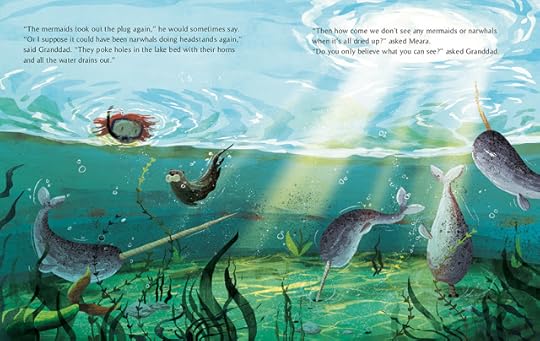

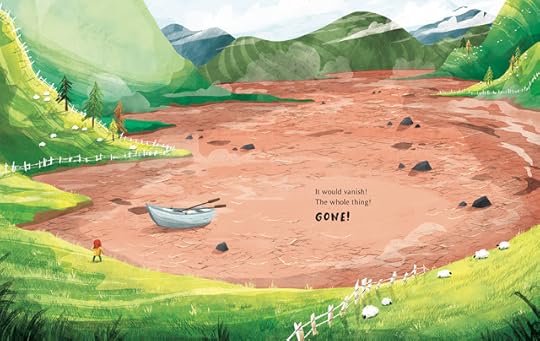

The Vanishing Lake is about a little girl called Meara who visits her Grandad who lives by a mysterious lake which disappears and reappears for no apparent reason. She constantly asks her Grandad why it happens and each time he has a more extravagant and unbelievable reason for her. Meara doesn’t believe any of his stories about mermaids, giants or narwhals, but with a little imagination she may discover the ‘real’ reason.

The story is actually based on a real place, close to where I grew up in Ballycastle in Ireland. It’s a lake called Loughareema which actually does disappear and reappear every few days, depending on the weather!

Storytelling is a huge part of life in Ireland, so I was surrounded by myths and legends from a young age and I think that’s had a big influence on me and my work. Rough seas, rugged coastlines, islands and mountains are all things I absolutely love to illustrate. That definitely comes from growing up surrounded by stunning scenery. It’s something I’ve come to appreciate so much more after moving away.

When you grow up with a wonder like this on your doorstep, you definitely take it for granted, and I hadn’t really thought about it for years. I was brainstorming a few different story ideas and it somehow popped into my head one day. I thought the title itself was intriguing and then I set off to build a story around that. I thought the mystery of ‘why’ the lake would disappear and reappear could be interesting to drive the story, and then setting the character up to be unwilling to believe each reason, spurred me on to come up with crazier and crazier ones.

I created the little girl of Meara for kids to relate to, and then I needed a wiser character who could tell her these tales. A grandparent made the most sense here as there’s something special about the relationship between grandparent and grandchild. They’re at such different points in their lives, but there’s often a really direct connection that kids don’t have with their parents. And grandparents are often full of wild tales. Playing on that familiar situation of a child asking ‘why?’ something is the way it is, and a parent/ grandparent trying to give an explanation was something I thought both the reading parent and child could relate to.

Meara couldn’t live by the lake herself, otherwise she’d be like me and probably think it was quite normal for it to disappear and reappear. The setting had to be familiar and at the same time strange and mysterious, so that was another reason to make it a grandparent who lived by the lake.

As most picture books have a standard number of pages, I knew how much I had to work with. I laid out some super rough thumbnails, plotting in the main set pieces - introduction to the lake, having it disappear and reappear, a few spreads of Grandad’s wild tales and then a few resolution spreads.

Once I had that really rough outline, I made slightly more detailed roughs. Then I finally moved on to the words. I’d learned a little from my characters from the sketching process, so I could now start writing in their ‘voices’. For example, I knew the Grandad would be really casually telling these magical stories of giants and mermaids, brushing them off as completely normal. Of course mermaids pulled the plug out!

I wrote and rewrote, all the while keeping the visuals in mind.

Trying not to show and tell, but have both the words and illustrations work together in harmony, as two halves of the same puzzle.

As I wrote, that would lead me to new ideas for illustrations, and as I would work on the final illustrations, I would be tweaking the words. I bounced back and forth, back and forth all the way until the end.

This was very different to my previous book projects, where I was illustrating someone else’s story. Usually in that situation, the manuscript has already been through an editing process and comes to you fully formed. So you don’t really have an affect on the actual words as you add the illustrations. I don’t really want to mess with the author’s words either, and I find that process really fascinating too. You get a huge flood of images in your head as soon as you read through a really well-formed piece of writing, and the best manuscripts already get me sketching after the first read.

I wanted to have the natural world shine through in the artwork, using a lot of vibrant colour schemes. I would take a lot of inspiration from the Irish landscape, but also with a little bit of fantasy world built in. The mix between imaginary worlds and the real world is a key element in this story, however it’s very difficult to see where one begins and one ends.

The lines are blurred, and I left plenty of space for the child reading it to decide what’s real and what’s not.

Maybe you’ll be able to pull some interesting insights out of how I worked on this picture book. Some things might work for you, some things totally won’t. Take bits and pieces from it, try it backwards, take a sledgehammer to it! Remember though, that this was my path for this one particular book, and I can already see that it’s not the same for my second author illustrated picture book. This next one is an entirely different kind of story and is presenting both new challenges and firsts for me as an author and illustrator. All really exciting though!

‘Process’ is, and should be, a constantly evolving thing as you grow as an author or illustrator.

Take comfort in the fast that everyone else is making it up as they go too. Don’t be afraid to get messy in your process. Try out something wild, new and scary and see what happens!

What does your current ‘process’ look like? Do you visualise images first when you’re writing a story? Do the characters already have a voice and you feel like you’re just writing down what they say. Do you have no idea what your characters will look like until the illustrator sends the first artwork? Or if you both write and illustrate, how does one fit with the other?

Watch trailer of the book here!

Watch Paddy's short interview here.

Paddy Donnelly is an Irish illustrator and author of picture books, and also creates middle grade book covers. He wishes Pluto was still a planet. Follow him on Twitter @paddydonnelly and on Instagram at @paddy

May 16, 2021

What a waste! by Laura Mucha

When I began writing for children, I was determined to illustrate my work myself. So I did numerous courses in topics ranging from painting to Photoshop, drawing to collage, and anything specifically on children’s book illustration.

I came to the slow, painful realisation that I wasn’t going to be good enough to illustrate picture books without a few more years of life drawing, so decided to give up on illustration and focus on my writing.

When people hear this, they often say, ‘You spent HOW MUCH!?’ or ‘How FRUSTRATING!’ and ‘What a WASTE!’ However spending a small fortune on studying illustration was anything but. It was invaluable – not just for my understanding of children’s book illustration and the creative process more generally, but also for my writing.

Here are some of the lessons I learned along the way.

Make a mess (The Slade)

Day one of a painting course at The Slade, I remember spending an inordinate amount of time trying to get the nice, neat lines in place so that I could make something nice and… er… neat.

But my nice and neat work was BORING because my textures were bland and there was no feeling or energy in there as I spent all my time worrying about line.

The tutor came over and told me to stop what I was doing. She laid large plastic sheets on the floor and instructed me to make a mess.

Encouraged by fellow students, I did. I ruined some clothes and shoes in the process, but it was worth it. I threw, squelched and smooshed the paint, then did the same the next week and the week after, before eventually stepping back to look at what I had and think about how I could tidy it up (with those beloved lines).

Tidied up walrus

Tidied up walrusI wasted months, possibly years, doing the equivalent in writing for adults and children – perfecting the detail before ensuring that the content was interesting and feeling-full. It doesn’t matter whether the full stops are perfect if the sentence is tedious and unnecessary…

Now I have a strict policy of throwing, squelching and smooshing words, before doing any sort of tidying. Only after my shoes and clothes are decimated will I even consider shaping them into lines.

Get it on the page (Central Saint Martins)

I was very busy staring at a blank piece of paper at Central Saint Martins when my tutor spotted me. He watched for a while before shuffling over and saying, ‘Don’t keep it in your head, you’ll only know if it works when you get it on the page’.

My first reaction was

‘BUT I HAVE NO IDEA WHAT I’M DOING!’

But, as he was the tutor and therefore knew everything, I took his advice. And I’m glad I did. What I could have spent another hour (or five) mulling over became very clear as soon as ink hit paper. I’ve found it’s the same with writing.

Writers disagree on how much you should think before getting your pens out. RL Stine, for example, plots the whole story before writing the chapters, whereas Stephen King doesn’t plot at all and instead begins with a situation (and some bland characters). I think I’m a mix of the two. I spend plenty of time thinking, but some of the most important creative work happens when I’m trying things out on the page.

Seeing something on the white space, seeing how many words there are, where the page breaks will be, and what the font size is helps clarify things. It also helps generate ideas and leads to those delicious ‘ooooooh’ and ‘ahhhhhh’ moments that make creativity worthwhile.

Pacing (House of Illustration)

I spent a very long time studying the visual pacing of picture books and quickly learned I didn’t want them to be uniform in terms of size or angle on each page. I wanted some close ups, some zooming out, some double spreads, some smaller images. But it’s not just the images that need pacing – so do the words.

A story shouldn’t be like a uniform set of steps. Some parts should be smoother, then suddenly steep, then you should face a terrible drop and wonder how on earth you’re going to escape, only for there to be a way down (or up) that you hadn’t thought of.

Creating a story where you find yourself stuck at the top of a cliff wondering how the hell you’re going to get down can obviously be a bit stressful… But I think it gets easier with time because you have more and more faith that you’ll figure it out. (Either that or you just start to carry a parachute with you.)

Steps that make for a boring story

Slightly more interesting story steps

Hmm...maybe a bit too-ooo non-linear

My studying wasn’t a waste. Not only did I learn about how to make books, I learnt about myself. I didn’t like not being good at something, but I had to suck it up while I learnt. I didn’t like making a mess, but I had to get to grips with that if I wanted to create something I could be proud of. I didn’t like not knowing how to resolve a story problem, but I had to sit with that if I wanted to write compelling tales.

Studying how to draw, paint, collage, and illustrate was time and money well spent. And I highly recommend it to anyone, even if they have absolutely no intention of illustrating themselves.

Laura Mucha is an award-winning poet and author. Her latest book is Rita’s Rabbit illustrated by Hannah Peck (Faber) and you can read /listen to her work at lauramucha.com. @lauramucha

May 10, 2021

Long Ago? by Pippa Goodhart

‘Long ago and far away’ is the setting for so many picture book stories, and yet historically realistic ‘long ago’ is rarely found. Why?

This question came to me as I’ve been compiling a virtual summer course for Cambridge University’s ICE (Institute for Continuing Education) on ‘Writing Historical Fiction for Children’. I had hoped to include picture books, early reader illustrated chapter books, middle grade novels, and young adult fiction. I do include all those, but very little on picture books because picture book historical fiction is scarce.

There is a current boom in picture books about famous people from the past, tapping into national curriculum topics for Key Stage 1 such as ‘the first aeroplane flight’ and ‘lives of significant individuals’ ranging from Mary Anning to Alan Turing. Those topics ensure book sales to schools.

But why not use historical settings for stories, as background, with no link to a great historical character or event?

Surely nobody thinks that a picture book story setting from the past would be off-putting to young children for whom everything is new? We rightly offer young children stories set in geographical places and in cultures very different from their own. They also happily accept characters who are peas and carrots and robots and cacti! Children are naturally ready to imagine and play. And they happily enjoy the very few picture books which do have a setting which we can see is from a past time.

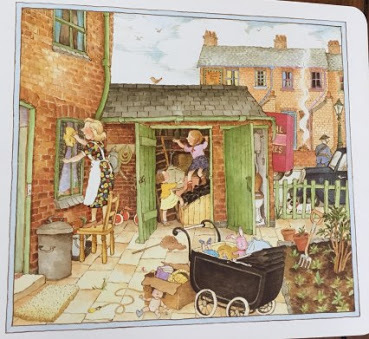

I wonder, did publishers in 1981 feel doubtful about Janet and Alan Ahlberg’s ‘Peepo!’ being set amid World War Two family life, a bombed building and air-raid warden visible? If they did, they needn’t have worried. Many, perhaps most, small children enjoy that book for its ‘peepo’ game, with the baby and adult family members they can relate to. Some might look at picture detail, ask questions, and have an interesting discussion about the differences in that home from their own with the adult who reads the book to them. But all children exposed to the book, will, I suspect, have absorbed a feel for that time and place. When they come to learning about the Second World War, and life on the Home Front, something of it will already be within their existing knowledge, thanks to ‘Peepo!’.

But, earnest educational value aside, life is simply richer and more interesting the more we know of it. So, let’s enjoy the diversity of story setting that the past offers us, and offer it to young children too!

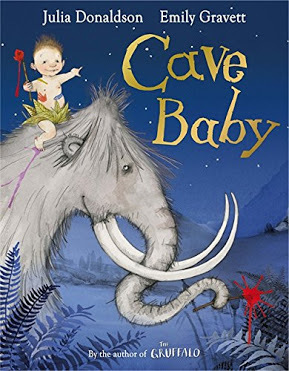

Why aren’t there more picture book stories with historical settings? Is it for fear of ‘getting it wrong’? With prehistory, so little is known that there’s a freedom to use a sort of generic visual shorthand for how things looked in Stone Age times; people in fur knickers, waving spears at woolly mammoths. There are quite a number of picture book stories set in prehistorical times.

But for historical times about which we know more, there will always be those ready to point out mistakes, just as they do for historical films. I’ve been an ‘extra’ when the ITV murder mystery ‘Grantchester’ series has been filmed in my home village, and, yes, they hung prop tights rather than stockings on a washing line set in the 1950s. Wrong! But the tights were background, and not pertinent to the story. If we mind too much about accuracy, we restrict ourselves for the sake of academic safety. That’s a waste. Children think in bigger ways than that.

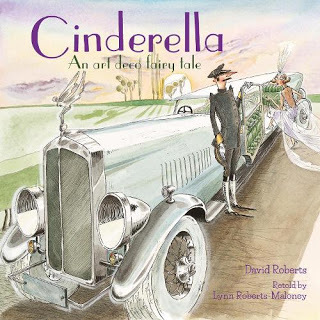

Children love ‘long ago’, and illustrators and publishers are confident when using a ‘long ago’ setting that is clearly fictional, so can’t be ‘wrong’. Fairy tales, and the many newly created picture book stories featuring knights and princes and princesses, tend to be set in vaguely ‘long ago’ times of long dresses and carriages and page boys. It’s the same unspecified ‘long ago’ sort of setting that pantomime sets and costumes go for. But let’s use the picture book opportunity to introduce children to more realistic other times.

David Roberts shows children lush 1930s Art Deco wonders in his version of Cinderella (written by Lynn Roberts Maloney).

I think there’s an opportunity here for more beautiful and interesting extra visual riches to be brought into some picture book fiction. I wonder if any publishers and illustrators agree?!

May 2, 2021

How I am Writing My New Books Every Minute Even When I'm Not • by Natascha Biebow

Writing is something I do. But most of the time, I am not writing.

While I am supposed to be writing, but really I am not writing, I am:

- Juggling: if you have work, family, volunteer commitments, and life in general like me, chances are you are also juggling. This is useful for writing because it means you are living. And living is what is at the heart of writing. So, I make lists, do the school run, hoover the house, check in on my mum, keep wishing dinner will cook itself, help run SCBWI-BI to pay it forward to other writers and illustrators, edit books, and breathe . . . because one day these experiences will be in my books.

- Reading Other People’s Writing (Books): each day, I indulge in a bit of R-E-A-D-I-N-G. Very often, this is not a children’s book, but if you pay attention while you are reading, you can glean quite a few useful things while you are not writing: inspiration how to write good (or bad) dialogue, techniques for storytelling, ideas for formats, insights into the competition, an awareness of the marketplace. If it’s a book that hooks, or a funny book, or an artfully written one, you can bask in good language like a shark basking in the sun and dream of one day writing a book like that too.

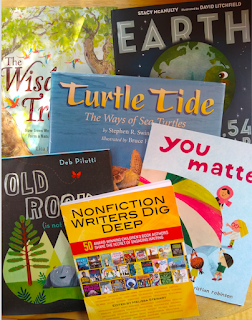

Some books I've been reading

Some books I've been reading

And picture books and nonfiction research

And picture books and nonfiction research- Walking the Dog: this is an excellent way to pound out plot problems and other writing niggles. Plus observing people in the park means you mightget the odd ideas for characters. Importantly, it makes you go out so you are not entirely a hermit in front of a computer staring at a blank screen or typing wondering where this book is going . . . You might even find out what is actually going on in the world and meet a person. And it's exercise so it helps you stay fit. (NB: If you don’t have a dog, you can walk yourself.)

My dog Luna lives for watching

My dog Luna lives for watching

then unsuccessfully chasing for squirrels.

- Reading Aloud to a Child (Or a Pet): reading A-L-O-U-D is an excellent way to get an ear for the sounds and structure of writing. When reading aloud, I get completely and totally immersed in the story and it is oh, so rhythmical in a way that reading silently just isn’t. (Sometimes I read my stories A-L-O-U-D to the walls – thankfully, they don’t voice their opinion).

- Cooking, cleaning, washing and Taking Care of Other Chores that always seem to need doing on repeat: see juggling (above).

- Listening to Craft Webinars or Reading Craft Books: mostly listening to other authors speak is a comforting language of threads of a shared experience in the life of writing; it is also great procrastination “Hey, I’m learning HOW to do it, yes, really” instead of bum on seat. Bonus is you can do it at the same time as Walking the Dog . . . and get in the zone.

- Watching Children be Children: if you are lucky to meet a child on your walk or pass a playground or even have family with children or children of your own, you can do something very important while practising not writing: watching and listening.

- Sleeping. A surprising amount of writing can be done in that subconscious state before you fall asleep. This is a great time to noodle around with ideas and story problems. Plus it's necessary.

-Eating Chocolate (Shhh!) definitely helps you keep going.

@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-520092929 1073786111 9 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-fareast-language:JA;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

In other words, I Am BUSY Living, So A Piece of Me Can Find Its Way Into My Books:

All this living is collecting material for writing. One day you’ll see it in my books. I am working on a new nonfiction project; while I’ve done some research and there is much more to do . . . as I’m ‘writing through living’, I’m figuring out HOW TO TELL THIS STORY to make it compelling for a child to read. Every book I write is written because of some living I did. A piece of me is in there, and it is this that I am hoping will connect with readers big and small to make the story resonate with them also.

Nonfiction picture books are 100% TRUE STORIES.

To figure out and collect the ‘true’ bit, I need to do a lot of outreach and research. I've decided my topic has ‘legs’ – e.g. it hasn’t already been done by someone else and it has a strong enough hook – so I am busy uncovering more of the required facts. Eventually, it will be time to weed out what should go in the book, and what should be parked up (what is not relevant to the story can possibly go in the backmatter).

Fueled by curiosity and a love of my new topic, my quest is to discover the inner truth, the passion that makes THIS story tick, the child-centred angle, something that will elicit an emotional response from my young readers so they, too, can connect with the spark that led me to write this book.

When I sell my idea to a publisher, you'll be the first to know how the living has made it become a real book. As I told a group of school children on a virtual author visit recently, it can take years to make a book, sometimes as long as they have been alive. It's about trusting the process.

For this, I need much time LIVING.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Natascha Biebow, MBE, Author, Editor and Mentor

Natascha Biebow, MBE, Author, Editor and Mentor Natascha is the author of the award-winning The Crayon Man: The True Story of the Invention of Crayola Crayons, illustrated by Steven Salerno, winner of the Irma Black Award for Excellence in Children's Books, and selected as a best STEM Book 2020. Editor of numerous prize-winning books, she runs Blue Elephant Storyshaping, an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission, and is the Editorial Director for Five Quills. She is Co-Regional Advisor (Co-Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. Find her at www.nataschabiebow.com

<span style="font-family: trebuchet;">@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-520092929 1073786111 9 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-fareast-language:JA;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</span>

April 25, 2021

It's About Time - with Mini Grey

A look at the challenges of depicting time in picture book form

One of my favourite ever films is The Time Machine. The original one, the proper one, the one from 1960, from the book by HG Wells.

The film features the best-styled Time Machine ever: “Everyone knows what a time machine looks like,” says physicist Sean Carroll, “something like a steampunk sled with a red velvet chair, flashing lights, and a giant spinning wheel on the back.”

There’s a moment when our Time Traveller tries out his magnificent Edwardian contraption and pushes its crystal knob towards the future, and days and nights start to flash by and the sun and moon chart visible tracks across the sky and the mannequin in the shop opposite bears witness to the march of time with her shortening fashions.

We’re (hopefully) reaching the end now of a year spent in lockdown. A year where days have flashed past, with the same daily routines, doing the same daily walks, watching the unfurling of Spring warm its way into Summer and noticing the progress of birdsong yield to late summer bird quietness. The repetition makes you pay attention to small differences. The tiny daily changes add up to slices from a stop motion film of the seasons’ progress. But I wonder whether some events will have been missing, the ones that make memorable experiences. With what will the memories be forged? – the highs and lows – the terror before real events with a real live audience, the monkey of dread sitting on your chest beforehand, and the collaboration and achievement and adventure when a long-planned event goes actually, unbelievably, well.

So lately I’ve been thinking about time, especially as the book I’m making at the moment is all about time.

This book really started about 10 years ago, at the Oxford Museum of Natural History, where I would often hang out with my small son Herbie. Admiring the Iguanodon skeleton, I realised I didn’t even know WHEN the dinosaurs had been extinctified by that asteroid (it was 66 million years ago) OR anything about what was going on BEFORE the dinosaurs (a LOT!) or how old the Earth was (about 4.6 billion years).

Then I wanted to see what 4.6 billion years looked like, and in the process of trying to find that out, I ended up making a model book about the story of life on Earth being performed in a shoebox theatre on a town dump. By insects. So that’s what I’m making for real now.

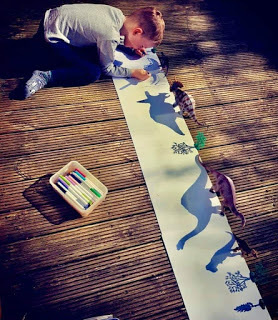

My model book for the story of life on Earth

My model book for the story of life on Earth It was a very long zig-zag and it would have been impossible to publish in this format.

It was a very long zig-zag and it would have been impossible to publish in this format. The reverse side of the model book had the tape measure of time on it, to show what 4.6 billion years looks like...

The reverse side of the model book had the tape measure of time on it, to show what 4.6 billion years looks like...At primary school you get to learn about the Greeks and the Egyptians and the Tudors, and it’s good to have a timeline of the last ten thousand years to hang these on. But maybe what young children need too, is a sense of the fundamental timeline, the Story of our world, the 4.6 billion year story of Life on Earth.

So what does 4.6 billion years look like?

For my time line, my Tape Measure of Time, I decided to have one centimetre represent one million years. That makes my total lifeline of the Earth 45 metres long which is about 10 cars long or a small street. But for loads of that time the biggest life on Earth was microbial. It wasn’t until around 600 million years ago that things got really interesting, and we start to get animals with bodies, and then the whole story of life speeds up for the last 500 million-year roller-coaster ride of changing climates and mass extinctions and explosions of different life forms. All the stuff that’s interesting to us has happened in the last 5 metres – it can fit along my stairs and landing.

This was my original timeline - each centimetre was 10 million years - so the last 500 million years happens REALLY FAST, in half a metre.

This was my original timeline - each centimetre was 10 million years - so the last 500 million years happens REALLY FAST, in half a metre.At my Tape Measure of Time scale of 1cm to 1 million years, each open double-page is around 50 cm wide – so about 50 million years. Quite a lot of the Ages of Earth – the Devonian, the Carboniferous, the Permian, and all the rest – lasted very roughly 50 million years.

Here's the Tape Measure at the 1cm to a million years scale.

Here's the Tape Measure at the 1cm to a million years scale.

Here are my insect Troupe acting out the Carboniferous Era.

Here are my insect Troupe acting out the Carboniferous Era.Modern humans first appear about 200 000 years ago, which is 2mm ago on my 45m timeline. The oldest cave painting is from about 45,000 years ago: that’s less than half a millimetre ago.

Humans farming and the Holocene time of warmth and plenty begins about 10,000 years ago: that’s 1/10 of a millimetre, or a hair’s breadth.

The last 100 years, where we have unleashed the enormous power of fossil fuels and a farming fertiliser revolution and human population has grown from nearly 2 to nearly 8 billion people, and the populations of wild animals of earth have plunged: all this has happened in one thousandth of one millimetre on my Tape Measure: cut a hair into 100 thinner hairs to find this width.

Ice Age Megafauna illustration by Sergio De La Rosa

Ice Age Megafauna illustration by Sergio De La RosaIf you visited Earth 100,000 years ago, it would be a place of astounding megafauna: mammoths, mastodons, woolly rhinos, giant sloths, sabre-toothed cats, giant elks and aurochs. As humans spread around the world from 60,000 to 10,000 years ago – very mysteriously the local megafauna always became extinct. Maybe the vanishing took a few thousand years – it may have been too slow for people to notice the changes. And it didn’t happen deliberately, I think – you can see the awe for the beasts in the cave paintings – but maybe the people didn’t see that occasional predation of what looked like an endless source of big animals eventually wasn’t in tune with the animals themselves – essentially, was unsustainable.

Around 10,000 years ago at the start of the Holocene, just about all the megafauna of America and Europe and Australia was gone. The place where megafauna lived on was in Africa. Was this because the humans and the megafauna had evolved with each other? In all the other places, early people had migrated in, and then mysteriously the megafauna vanished.

Maybe evolving with the megafauna rather than encountering them, kept a balance. And somehow we have to create balance today.

We are prisoners of our short lifespans – we last for a blink of an eye in the Earth’s lifespan but to us 100 years is forever. And with nature we fall victim to shifting baselines: you get used to there being less.

We have to give back habitat to nature. Because if we don’t have a balance but a slow but inexorable shrinking of animal populations it leads relentlessly to extinctions – because that’s what enough time mixed with a slow process of reduction will always do. In a country like Great Britain, where we have made so many predators extinct, and appropriated so much of the land to human uses and fragmented the landscape with tarmac – we should especially be halting the appropriation of wild or unbuilt-on land to human uses. We also should contribute to the wilderness and wildlife of the planet.

Roman Krznaric’s book The Good Ancestor is about how to look further. Let’s look into the future: Earth has about 500 million good years left, before the sun swallows it up. That’s another 5 metres on my tape measure. That’s as long as we’ve already had visible animal life for. We have to use our imaginations to see longer and further into the future – to imagine a future where people and the rest of the world are in balance: what would that look like? And in the context of that, examine everything we do: does doing this ultimately wreck the planet, or could this happen happily for ever?

(Building on wild spaces. Intensive animal agriculture. Bottom trawling. Emitting CO2. I’m looking at you.)

But now, with a jolt, I’m getting in my backwards time machine and zooming back to 15 years ago, 2006.

I’m in the John Radcliffe Hospital; my son Herbie has just been born. He was born at 6.45am after a night of gas and air and the help of the world’s best midwife. Now it’s mid-morning. His dad Tony needs to return home to feed the cat, and then I will be alone with our new life form, who is asleep at the moment.

But there’s a TV by my bed and it works – (what are the chances of that?) and it’s playing the film of The Time Machine (what are the chances of that?). The original 1960 one, the good one.

Off you go Tony, I say, I’ll be fine. This is my absolutely favourite film.

I listen to the lilting haunting theme music of The Time Machine, and I think about the small new life-form that’s just been born. I think about how it has just started on its journey through life, a journey that travels only one way, that my new life-form is a time machine, that we’re all time machines, travelling ever onwards, only going forwards, while our brief window of experience is open. And the brief window of experience and existence shines like a short flash of light in an infinite oblivion that stretches forever before and beyond it.

But that’s the danger of listening to lilting haunting music when you’re marinating in hormones after just giving birth to a baby.

A nice doctor turns up to check something medical. Tears are flooding down my face. She suggests that she returns at another time. Between gulps I just about manage to explain how much I really reallylove this film.

Mini's latest book-involvement is The Book of Not Entirely Useful Advice, with AF Harrold. Her BlogSite is at Sketching Weakly.

April 18, 2021

Never Ever Give Up! by Cath Jones

When is it time to give up on a story? This question is often asked by aspiring picture book authors and my answer is simple: never. I think you’ll see why after I tell you about a slug.

image jgrrz PIxabay

image jgrrz PIxabayBack in 2012, I was part of an online SCBWI critique group. It was then that I wrote ‘Slug in Love’. The central character was a lovable, optimistic slug, a glass half full kinda Slug.

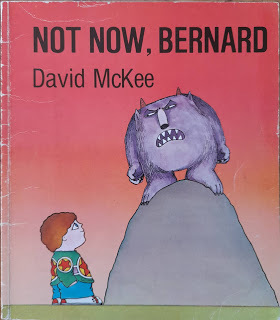

The story went down well; everyone loved the first half. Reaction to the ending however, was mixed. I do have a tendency towards black humour (Not Now Bernard is my all time favourite picture book) but not everyone appreciates this!

After months of rewriting, in 2013 I shared it with another critique group. I really liked my rather yucky, slightly shocking ending; similar in style to The Italian Job. But once again, opinion was divided.

I set to work on yet more rewrites; I created so many different versions! A human character became a bear and then a human again. But nothing seemed quite right. Finally, I set the story aside and moved on.

Three years later I had my first stories accepted for publication. Dozens of books followed, published by a number of different publishers. Occasionally I thought of Slug.

Then, in July 2019, I had the opportunity to submit to an editorial meeting. I opened up my WIP folder. There were lots of texts to choose from! Slug in Love stood out. I knew the text wasn’t quite right but heh, it definitely wouldn’t get published languishing in a file on my computer.

A few days later, I received an email from the editor:

“The idea is really fun, and the way it’s written is hilarious, but we do feel the ending is a bit bleak and would need to be changed.”

It was the same old story, the ending! But at least an editor was interested. I spent months rewriting it, added Spider, a sidekick for Slug and finally did away with my grisly ending. October 2019, I submitted a revised text.

The editor emailed:

“...it did have us all laughing out loud!” but the ending still needed revising.

In the following months, I rewrote it again and again. Then the pandemic struck and everyone started meeting on ZOOM.

A geographically scattered group of writing friends started meeting on online. Dorset based Lizzie Bryant, a storyteller and former film editor and producer read Slug in Love. She is a master of story and helped me understand my own story:

the central theme is the impossible friendship between Slug and a gardener and this needs to be resolved!

image Harriet P from Pixabay

image Harriet P from PixabaySounds simple? It was a revelation! I started thinking about Slug in Love in a whole new way. For the first time, after seven years of living with this story, I truly grasped the essence of it. Immediately, I knew why it wasn’t working. Out went my funny but still not very happy, ending. More months slipped by as I pondered how to make it work.

February 2021, I was out taking my daily pandemic lockdown walk, picking up litter and thinking story when BAM, I started talking excitedly about THE BUCKET OF DOOM. I was on the way to new ending!

I rewrote the second half of the text and emailed my very patient editor. The reply?

“Yay! You’ve cracked it!”

So I wrote Slug in Love in 2012 and it was accepted in 2021! The title has changed, I have lost count of the number of rewrites and bleak endings have been banished. This picture book journey, from first idea to signing the publisher contract makes one thing abundantly clear:

NEVER EVER GIVE UP ON A STORY!

Cath Jones

Cath Jones

Cath is the author of dozens of early readers, junior and middle grade fiction and a quirky picture book. She’s passionate about diversity and strong female characters. She’s particularly proud of The Best Wedding Gift, a story featuring a child with two mums. Her life is dominated by vegetable growing, picking up litter and swimming in the sea. Cath lives in Kent with her wife and a spoilt rescue cat. Chat with her on Twitter: @cathjoneswriter

April 11, 2021

Picture Book Characters with a Passion for Fashion by Garry Parsons

Who Wants to be a Poodle - Lauren Child

Who Wants to be a Poodle - Lauren Child

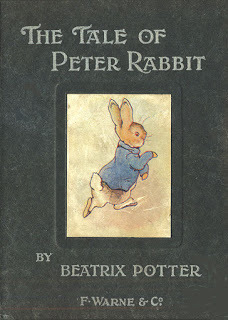

Animal characters in children’s books have long been wearing clothes, but some appear to a have a passion for fashion unbounded.

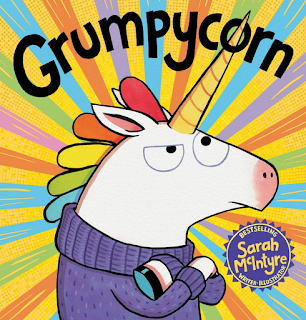

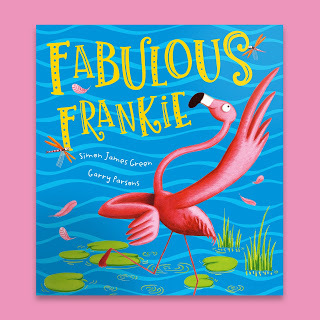

Fabulous Frankie - Simon James Green and Garry Parsons

Fabulous Frankie - Simon James Green and Garry Parsons

Having recently illustrated a book where the central character has a penchant for fabulous attire, I have been taking a closer look at what the animal characters on my bookshelf are currently wearing and revisiting some old favourites whose clothing style still remains striking.

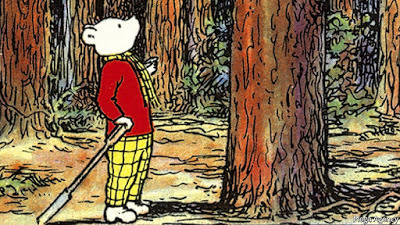

Rupert The Bear - The Daily Express

Rupert The Bear - The Daily Express

Stories where animals appear wearing humans’ clothes preoccupy most of my bookshelf, as they seem to do in most children’s bookshops. This anthropomorphism is everywhere in our lives and has a long history in literature.

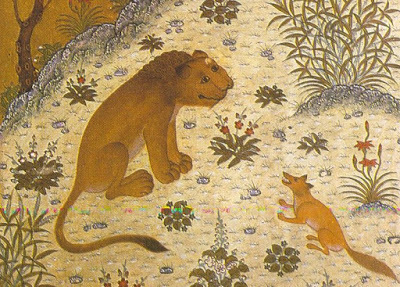

Illustration from the Panchatantra

Illustration from the Panchatantra Preceding Aesop’s Fables by centuries, personification is a well-established literary device from ancient times such as in the Panchatantra from India, in which anthropomorphized animals illustrate principles of life.

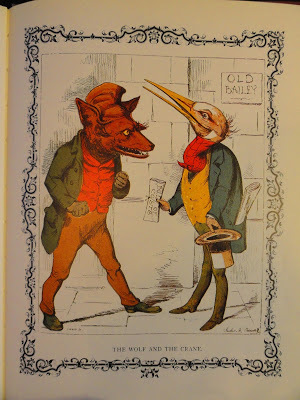

The Wolf and the Crane - Aesop

The Wolf and the Crane - Aesop

Many of the animal stereotypes we are familiar with today originate from these texts and have an influence on what we read today and the roles animal characters take on in our stories but these weren’t aimed directly at children in the same way we recognise animal characters in picture books today.

Before the mid-eighteenth century, the notion of childhood, as we know it now, did not exist. Children were dressed in adult clothes and their natural playful curiosities were largely ignored, at least in literature, where illustrated material for children was virtually non-existent. Later, as the middle class developed and views about children changed, adults began catering to their emotional needs, and animals with human characteristics began to appear in children’s books.

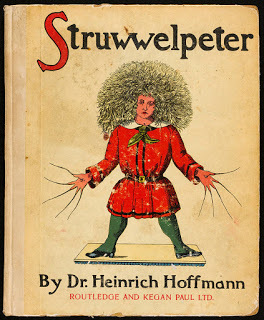

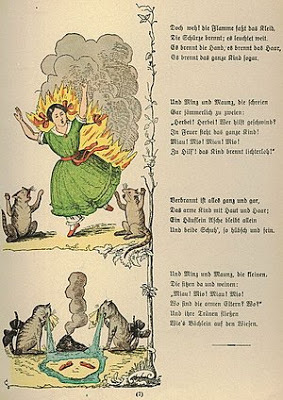

Struwwelpeter, considered to be the first children’s picture book that used anthropomorphism in illustrations (1845) is a collection of moral tales that relate what might happen when children don’t heed the advice of parents, to pretty disastrous consequences. Heinrich Hoffmann was a physician as well as author and illustrator of the book and created the stories for his son as a Christmas present.

In The Dreadful Story of Harriet and the Matches, Harriet ignores the warnings from the two cats not to play with matches which results in her catching fire and being burned to ashes, just leaving a pair of shoes. The cats in the illustrations are not yet wearing clothes but do use handkerchiefs to dry their tears at Harriet’s demise.

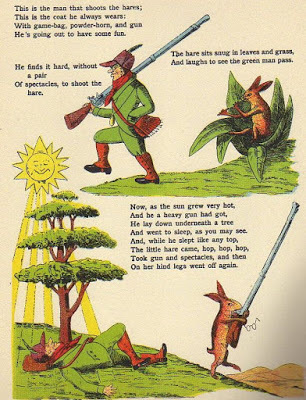

In The Story of the Wild Huntsman, the hare steals the hunter's gun and spectacles and turns the gun on him until he falls down the well outside his house.

Looking at these illustrations now, we can be forgiven for having a nostalgic view of them because of their attire but the clothing that Potter’s characters are made to wear are mainly for them to look socially acceptable for the time, rather than the characters themselves having a desire for fashion.

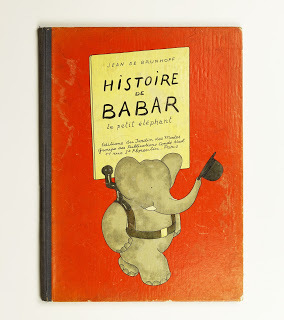

However, The story of Barbar, the little elephant by Jean De Brunhoff, first published in France in 1931 (English edition 1934), tells the story of an elephant who discovers an attraction to tailored suits and fine footwear. The first story of Barbar depicts his life as a young elephant who is tragically orphaned by a miserable hunter right at the beginning of the book. The distraught Barbar flees from the hunter and finds himself in a wealthy provincial town where his mind is taken off his tragedy by his admiration of the clothes of the people who live there.

Everyone in the town appears to share an enthusiasm for fashion including an old lady who helps Barbar out with a place to stay and some spending money. Barbar purchases himself a smart green suit, a lovely bowler hat, shoes and spats. How wonderfully smart he looks!

Barbar’s cousins, Arthur and Celeste, find him in the city and help encourage him to return to the ‘Great Forest’ where, with his new found knowledge from the city, he becomes the new Elephant King and marries his cousin Celeste in stylish wedding clothes picked out by a dromedary with an uncanny eye for high fashion.

The attention to stylish clothing perhaps reflects the fact that the original publisher of the books was Editions du Jardin des Modes, a French language women's fashion magazine published monthly in France between 1922 and 1997 and owned by Condé-Nast. The Babar books were the first Condé-Nast publications not specifically about fashion.

In contrast to Barbar, Mr. Tiger, in Mr Tiger Goes Wild by Peter Brown, feels dissatisfied with his formal dress and discovers that he feels more himself in a quadruped stance than the adopted bipedalism of city life. His friends lose patience with him and he leaves the city to reclaim his wildness. When he returns later, he discovers other folk in his community are also feeling the urge to be themselves and abandoning their need for clothing.

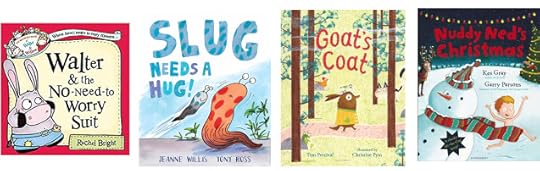

Clothing plays an important role in the narratives of many picture books - Walter & the No-Need-To-Worry Suit by Rachel Bright, Slug Needs A Hug from Jeanne Willis and Tony Ross and the Goat’s Coat by Tom Percival and Christine Pym to name a few, but clothing also gives the illustrator a chance to deepen the character they are depicting through what they are wearing, or notwearing, as is the case for Kes Gray’s streaking Nuddy Ned.

Curious to find out why Sarah McIntyre’s Grumpycorn wears a purple roll neck sweater, she told me…

As I mentioned at the beginning, I have recently been illustrating the story of a character who’s desire is stand out from the crowd and the only way he is sure he can do that is by being fabulous. But for a flamingo in a lagoon full of fabulous flamingos, standing out from the crowd is not an easy task, even when your wearing a sequin cloak inspired by Kansai Yamamoto!

***

Thank you to Sarah McIntyre for answering my question about Grumpycorn. Sarah is a best selling writer and illustrator. See more of her work here. @jabberworks

Garry Parsons is an illustrator of many children's books. @ICanDrawDinos

For more picture book passion for fashion, Fabulous Frankie by Simon James Green and illustrated by Garry Parsons publishes 1st June from Scholastic.

@font-face {font-family:Arial; panose-1:2 11 6 4 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:10887 -2147483648 8 0 511 0;}@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-1610611985 1073741899 0 0 159 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}span.css-901oao {mso-style-name:css-901oao; mso-style-unhide:no;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US; mso-fareast-language:JA;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}