Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 14

November 14, 2021

Do you control the verse, or does the verse control you? by Michelle Robinson

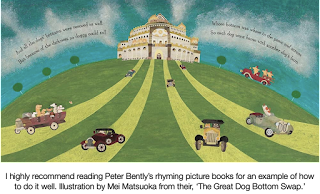

If you’re serious about writing picture books, you’ve probably been warned-off writing in rhyme. The reason given was most likely that rhyme doesn’t easily translate, making it hard to sell co-edition rights and limiting potential profits.

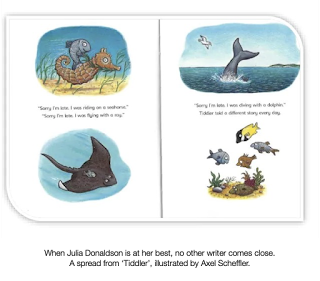

I expect you’ve argued back: Rhyming hasn’t done Julia Donaldson any harm. Loads of popular and successful picture books are written in verse.

It’s all true. You know what else is true? Those popular and successful books are exceptional, and your attempt at rhyming text is most probably not.

It’s an uncomfortable fact to deliver, and an even harder fact to swallow, but it’s still a fact. Ask any editor, agent or skilled writer of rhyming picture book texts. We get sent dreadful text after dreadful text, and are left wondering, how can the writer not see how bad they are at this?

Let’s just break that bit in bold down a second.

Rhyming. Picture book texts.

Writing rhyme requires skill.

Writing picture books requires skill.

Writing popular and successful rhyming picture books requires at least double the skill, a wing, a prayer, plenty of pig-headed determination and a backbone of steel for dealing with all the editing, let alone handling the rejections.

So how do you acquire those skills? And how do you learn to tell the difference between top quality verse and terrible rhyme? The answer is straightforward, but getting there isn’t easy. You work, hard.

You pick every word with consideration. You edit your own work ruthlessly and tirelessly. If there even might be a better alternative, you chuck out your favourite line and try a new one.

You keep all of the following in mind at every stage: plot, character, sense and logic, age appropriateness, commercial appeal, rhythm, timing, accent and pronunciation, syllables, stresses, emotional arcs, story beats, universality, originality, overall word count, word count per page, page turns, potential changes of scene in the illustrations… There’s more, but that’s enough to be going on with.

You write and you rewrite, over and over and over again, taking all of the above into consideration along the way. If you don’t, it will show. Nothing is more obvious than inexperienced (or lazy, but I’ll give you all the benefit of the doubt) writing.

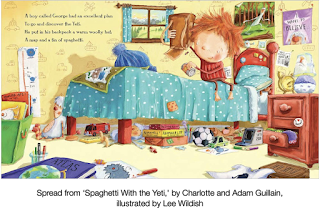

To make it simple, let’s just take the most basic step — rhyming. The inexperienced writer finds the first rhyming word and tells herself, “That’ll do”. This might lead to the occasional happy result (for example Spaghetti with the Yeti, a lovely rhyming book cleverly crafted by Charlotte and Adam Guillain), but by and large it will force your story to take a particular and constrictive path.

If you’ve ever tried writing in rhyme, you’ll know what I mean. When you pick a word just and only because it rhymes, the verse is leading you. To master writing rhyming picture books, you need to keep working until the opposite becomes true.

Through hard work, you will learn how to control the words, and not be led by them. Here’s an admittedly silly example.

You come up with a line that you like. Let’s say it goes,

A mouse took a swim in a deep, dark pond.

I like that, you think to yourself, whatever happens next, that line’s a keeper. Now I just need to think of something that rhymes with pond…

A mouse took a swim in a deep, dark pond.

He said to himself, “What might be beyond?”

That works, you kid yourself. The grammar’s questionable, but it’s a solid rhyme, and it seems to bounce along okay. I reckon I can get away with it.

No, you can’t, it’s rubbish. No one speaks like that, so your character instantly sounds inauthentic. And the next bit now has to be about what’s beyond the pond, so your plot is being dictated by the rhyme, too.

The experienced writer will stop here and start over. But starting again is hard work and raises lots of difficult questions. Who is the mouse? Would a mouse really swim? Why? Might a different character and setting work better? Does that opening line sound oddly familiar? etc., etc.

But what the heck, you’ve made two lines rhyme, and that feels like a solid start. Onwards! Although… it’s getting hard to find rhymes for ‘pond’. Not to worry, there’s always rhymezone.com.

Bond. Fond. Frond. Wand…

Ooh, a wand — he could be a MAGIC mouse, that might be fun. Look at me, I’m writing in rhyme!

A mouse took a swim in a deep, dark pond.

He said to himself, “What might be beyond?”

So he swapped his swimming trunks for a magic wand.

And he waved it around, then his hair turned blonde.

You;’re only four lines in and, because the verse has led you and not the other way around, you’ve already made several rods for your back.

The rhythm is clunky and the beat is off. You’ve created a weird aquatic mouse with clothing and hair. You’ve also made him magical, for no reason other than the rhyme suggested it, and now you have to write a story about him rescuing his barnet. This is nonsense — and not in a good way. Can you imagine a whole story this bad? Line after line of poorly crafted, ill-conceived non-story?

Those of us working in publishing don’t have to imagine them, we get sent them all the time.

A skilled writer will not let the rhyme lead them. They will not remain so wedded to a line that they sacrifice sense, rhythm, logic — and the rest.

A skilled writer will grab the reins and force the story to work, and work flawlessly, so that the rhymes are so neat, so carefully chosen and constructed that you barely even notice they’re there.

The reader won’t be left questioning the choice of character or their journey, because the story will make perfect sense. When read aloud, it will cast a spell over the room. It might bounce and invigorate, or comfort and calm, and it will resolve in the most satisfying way.

No clunkiness. No raised eyebrows. No double takes. No words that only work when read aloud in a certain accent. No made up words (unless you’re Dr. Seuss). No blonde mice. Just a great story that would stand up just as well if you rewrote it in prose — which skilled writers are often required to do.

Writing in rhyme is enormous fun and I would encourage anyone to give it a go. But please think twice before submitting i t as finished work. Have you really finished, or have you only just begun?

Michelle Robinson

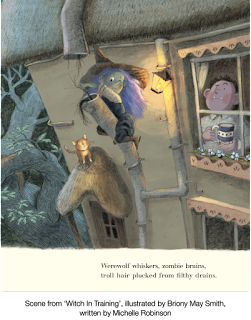

Michelle is the author of many picture books, including Lollies award-winning Ten Fat Sausages, illustrated by Tor Freeman. Her books have been read and sold all over the world, and even on the International Space Station. She is still learning to write flawless rhyme.

Website: www.michellerobinson.co.uk

Twitter: @MicheRobinson

Instagram: @MichelleRobinsonBooks

November 9, 2021

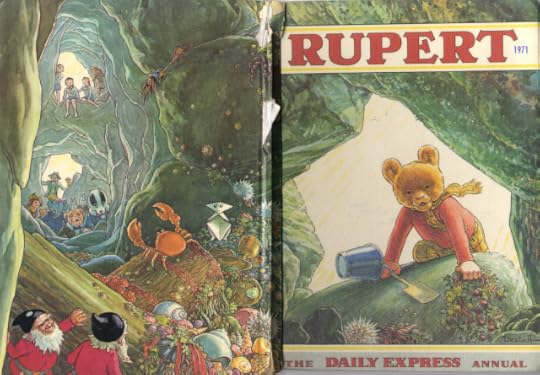

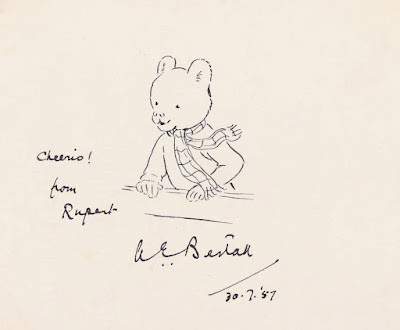

Alfred Bestall and the enduring life of Rupert - Garry Parsons

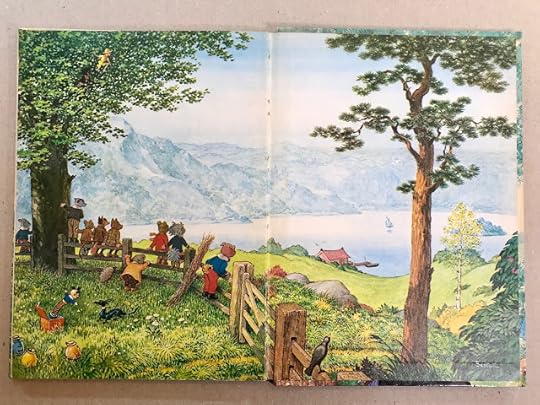

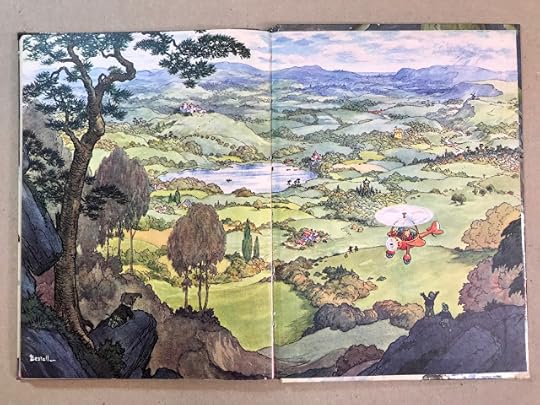

Alfred Bestall's illustrations for Rupert Bear have had a huge influence on my work as an illustrator and this blog post is a little visual celebration to honour his work.

Rupert Bear was originally created for The Daily Express in 1920 by Mary Tourtel, an established artist and children's book illustrator. Mary's husband, Herbert Tourtel was a news editor at the paper.

At that time, The Express needed a comic strip character that could rival the Daily Mail's popular 'Teddy Tail' strip series for children, and so Herbert turned to his wife to create one. The early Rupert strips were written by Herbert and drawn by Mary, as two cartoons each day and often in rhyme.

Mary stopped drawing Rupert in 1935 when her eyesight deteriorated and Alfred Bestall was selected to take over. Mary's last published cartoon was Rupert and Bill's Seaside Holiday, appearing in the paper on June 27th and Alfred Bestall's first strip, Rupert, Algy and the Smugglers ran the next day. Unlike Mary, who relied on her husband for the words, Alfred agreed to take on Rupert on his own. This became a life long dedication, though incredibly, Bestall didn't sign his work for the first 12 years out of respect for Mary until her death in 1948.

Bestall had studied at the Central School of Art in London and was an accomplished artist, exhibiting pictures in the Royal Academy and forging a career as a commercial artist making regular illustrated contributions to Punch and Tatler before taking on Rupert as a way to secure more regular work.

He also served in World War 1 as a motor transport driver in the British Army where he transported troops and ammunition, often under enemy fire.

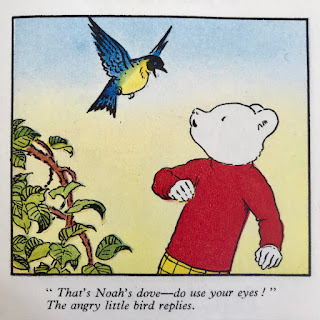

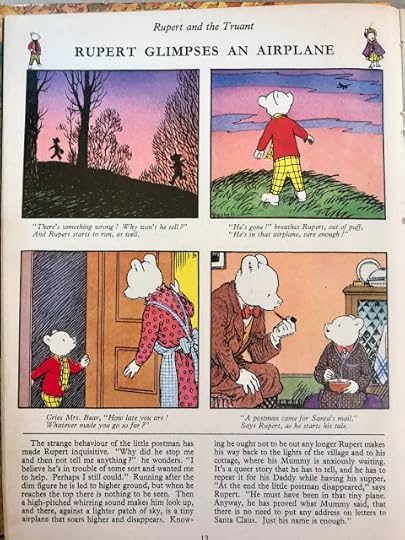

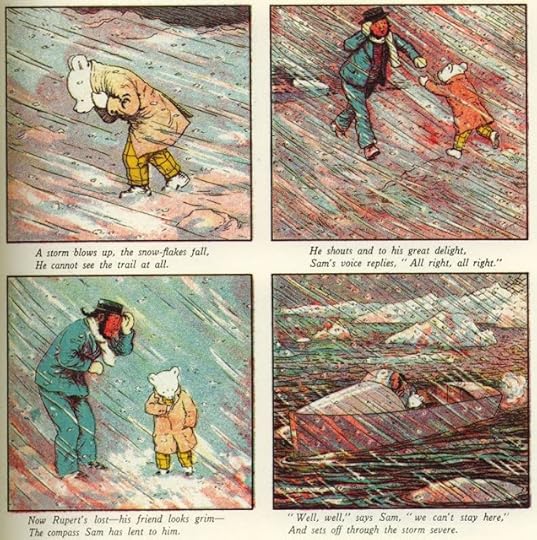

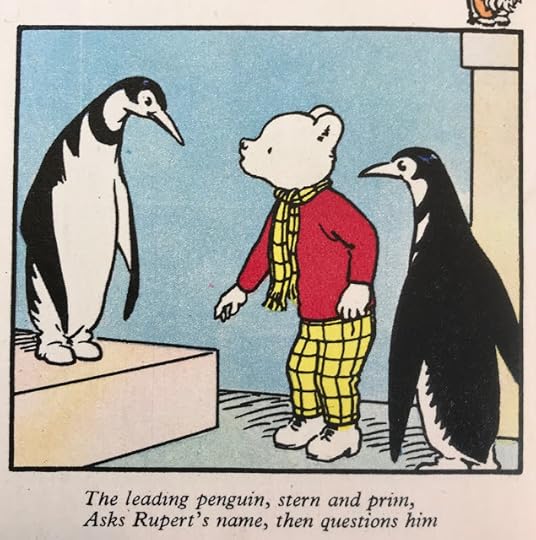

Bestall developed the classic Rupert story format: the story is told in picture form (generally two panels each day in the newspaper and four panels to a page in the annuals), in simple page-headers, in rhyming two-line-per-image verse, and as running prose at the foot. Rupert Annuals can therefore be "read" on four levels.

Alfred retired from drawing the Daily Express strips in 1965 at the age of 73 creating 273 Rupert stories in all. He continued to draw for the Annuals until 1983.

I adored the Rupert books as a child and like many children, I was given a Rupert annual as a Christmas present each year.

I would practice my signature a few times before I scrawled my name inside and then I’d read them cover to cover. I loved the illustrations and the myriad of characters and that you were given the choice of how you read the stories but even then I'd often skip the reading altogether and make up my own narrative from the illustrations.

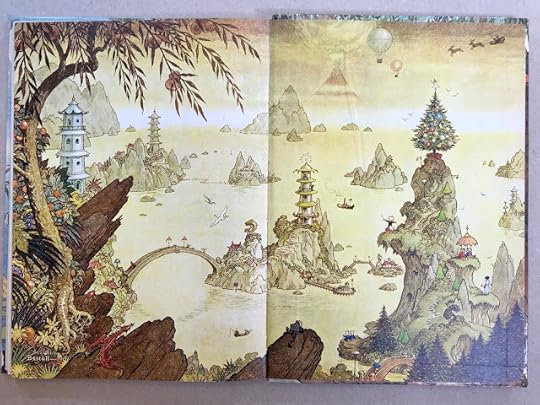

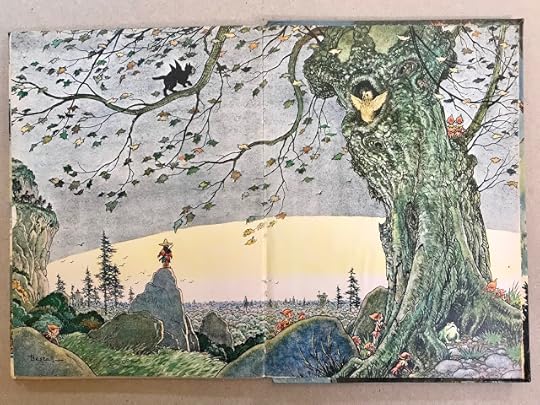

One of the most absorbing parts about the books for me then, as now, is getting lost in the end papers.

@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US; mso-fareast-language:JA;}.MsoPapDefault {mso-style-type:export-only;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

If you are interested in Alfred Bestall's life and work, read Caroline G. Bott's 'The Life and Works of Alfred Bestall' (Bloomsbury, London, 2003). For a shorter read online, try Lambiek Comiclopedia here.

Garry Parsons is an illustrator of children's books. You can find him here and follow him @icandrawdinos on instagram and twitter.

***

November 1, 2021

What Happens to Rejected Books? By Gareth P Jones

Being a writer means dealing with rejection, but what happens to the stories that never made it? Do you look at them with sadness, shame or regret? Do you still have hope that will one day they will find homes? Can you bear to read them? Every writer is different, so I asked the question on Twitter.

I had 50 replies from a wide selection of writers. These replies were interesting, revealing, helpful and heartening and this blog is an attempt to summarise them.

Reject the Rejects

Personally, I rarely look at my rejected books. The way I deal with rejection is to emotionally detach myself from the work and begin work on something new. I'm not the only one. Children’s author, Sally Nicholls replied, “I have quite a short statement span when it comes to ideas and have usually moved onto something else.”

Animator/Illustrator Steve May replied: “They sit in a folder & never really get revisited because they all feel a bit 'tainted'.”

Tainted is a great word. I feel like these unloved ideas have let me down – although it’s more likely that I’ve let them down. As author/publisher, Lucy Courtney points out, this is especially gruelling with certain picture books. “It’s the carefully worked rhyming texts that kill me. Too good to bin! Not good enough to publish! Impossible to revise!”

But are we being too hard on our previous efforts? Books are rejected for all kinds of reasons and so much is about timing, luck and circumstances. And sometimes it’s impossible to completely move on. Picture book author Dr Fiona Barker replied, “Some of them go and sit quietly in a corner, ashamed of themselves. But others won’t keep quiet and are quite demanding and high maintenance.

Recycle & Reuse

A lot of the replies revealed a Frankenstein-like approach. Author/illustrator, Paul Linnet wrote: “I dismantle the stories and use them for parts.”

Writer/editor Sean McSweeney finds it helpful to give his stories a cooling off period before going back to “plunder bits for other work.”

Bloomsbury commissioning editor/author, Jonathan Eyers agrees. “All the good stuff gets cannibalised eventually. I've even lifted descriptions and dialogue from one project to another, and sigh secretly with relief that the earlier one didn't get published because things work better in the later one.”

Author, Ashok Banker replied, “I mine them for material. I'll often lift characters, plotlines, even entire chapters and then revise extensively and use it in the new work.”

Here we see writers are plunderers, miners and, er… cannibals, but I enjoyed hearing this more positive approach. Writer/editor Roz Kay wrote a novel that was rejected by everybody for several years so she “took two of the chapters, buckled them together, and called it a short story, which was selected for publication in an international competition.”

Unpublished Not Unloved

Teen fiction author, Tamsin Winter reminds us that unpublished isn't the same as unsuccessful. “My son insists on me reading one of them again and again,” she replied. “It’s a hit in our house.”

Writer/Photographer Lou Abercrombie keeps the faith. “I completely believe in all of them! I can't bear to think of them as never being read by someone.” We’ve lived with these characters so long, it can be hard to let them go. Author/Artist/Lecturer NJ Simmonds wrote, “It’s weird to love fictitious people then never see them come to life.”

For writers such as Lorraine Johnson, self-publishing is the answer. “I was given good feedback but a ‘don’t feel enthusiastic enough to proceed’ kind of knock backs. I self-published it and it’s doing well!”

Lost Stories Found

So many of the replies were 'good news' stories. Author/Academic, Jo Nadin said, “They sit in a folder called ‘books in need of a home’. Every few years they get resubmitted elsewhere (and sometimes to the same place), and every so often they get accepted. Markets change. Editors move.”

Author, Kerry Drewery’s latest novel, The Last Paper Crane was initially rejected, but she told me, “It sat on a shelf for a few years and then with advice from new editor, I tweaked it and it found a home.”

Anna Wilson writes books for adults and children and her next picture book "went around the houses, but found a home eventually and now it looks STUNNING!”

Picture Book Den children’s author, Clare Helen Walsh said, “I have a picture book coming out in 2022 that I first wrote at the end of 2018. I came back to it twice before getting it just right. There was something about it.”

New York based picture book author. Naomi Danis wrote to tell me: “Several of my picture books got published after ten or more years of being rejected. Enough of the rejections included some words of encouragement to keep me going. I submitted I HATE EVERYONE for 11 years, and WHILE GRANDPA NAPS for 17 years. I'm never sure if it is encouraging or discouraging for people to learn it can take so long.”

I don’t about you, but it gives me great hope to hear so many accounts of authors who didn’t give up on their work and who rejected rejection and found acceptance. Or, as children’s author, Emma Read put it, “I really needed to read this today. There is hope for the unloved stories after all.”

Gareth P Jones is the author of 45 published books – and countless more that lie in the dark recesses of his computer. After writing this blog he's thinking of going back and looking at them. His published works include The Thornthwaite Inheritance, Solve Your Own Mystery: The Monster Maker, Rabunzel and CinderGorilla.

And if you want to read the full twitter thread, you can find it here.

What Happens to Rejected Books?Being a writer means deal...

What Happens to Rejected Books?

Being a writer means dealing with rejection, but what happens to the stories that never made it? Do you look at them with sadness, shame or regret? Do you still have hope that will one day they will find homes? Can you bear to read them? Every writer is different, so I asked the question on Twitter.

I had 50 replies from a wide selection of writers. These replies were interesting, revealing, helpful and heartening and this blog is an attempt to summarise them.

Reject the Rejects

Personally, I rarely look at my rejected books. The way I deal with rejection is to emotionally detach myself from the work and begin work on something new. I'm not the only one. Children’s author, Sally Nicholls replied, “I have quite a short statement span when it comes to ideas and have usually moved onto something else.”

Animator/Illustrator Steve May replied: “They sit in a folder & never really get revisited because they all feel a bit 'tainted'.”

Tainted is a great word. I feel like these unloved ideas have let me down – although it’s more likely that I’ve let them down. As author/publisher, Lucy Courtney points out, this is especially gruelling with certain picture books. “It’s the carefully worked rhyming texts that kill me. Too good to bin! Not good enough to publish! Impossible to revise!”

But are we being too hard on our previous efforts? Books are rejected for all kinds of reasons and so much is about timing, luck and circumstances. And sometimes it’s impossible to completely move on. Picture book author Dr Fiona Barker replied, “Some of them go and sit quietly in a corner, ashamed of themselves. But others won’t keep quiet and are quite demanding and high maintenance.

Recycle & Reuse

A lot of the replies revealed a Frankenstein-like approach. Author/illustrator, Paul Linnet wrote: “I dismantle the stories and use them for parts.”

Writer/editor Sean McSweeney finds it helpful to give his stories a cooling off period before going back to “plunder bits for other work.”

Bloomsbury commissioning editor/author, Jonathan Eyers agrees. “All the good stuff gets cannibalised eventually. I've even lifted descriptions and dialogue from one project to another, and sigh secretly with relief that the earlier one didn't get published because things work better in the later one.”

Author, Ashok Banker replied, “I mine them for material. I'll often lift characters, plotlines, even entire chapters and then revise extensively and use it in the new work.”

Here we see writers are plunderers, miners and, er… cannibals, but I enjoyed hearing this more positive approach. Writer/editor Roz Kay wrote a novel that was rejected by everybody for several years so she “took two of the chapters, buckled them together, and called it a short story, which was selected for publication in an international competition.”

Unpublished Not Unloved

Teen fiction author, Tamsin Winter reminds us that unpublished isn't the same as unsuccessful. “My son insists on me reading one of them again and again,” she replied. “It’s a hit in our house.”

Writer/Photographer Lou Abercrombie keeps the faith. “I completely believe in all of them! I can't bear to think of them as never being read by someone.” We’ve lived with these characters so long, it can be hard to let them go. Author/Artist/Lecturer NJ Simmonds wrote, “It’s weird to love fictitious people then never see them come to life.”

For writers such as Lorraine Johnson, self-publishing is the answer. “I was given good feedback but a ‘don’t feel enthusiastic enough to proceed’ kind of knock backs. I self-published it and it’s doing well!”

Lost Stories Found

So many of the replies were 'good news' stories. Author/Academic, Jo Nadin said, “They sit in a folder called ‘books in need of a home’. Every few years they get resubmitted elsewhere (and sometimes to the same place), and every so often they get accepted. Markets change. Editors move.”

Author, Kerry Drewery’s latest novel, The Last Paper Crane was initially rejected, but she told me, “It sat on a shelf for a few years and then with advice from new editor, I tweaked it and it found a home.”

Anna Wilson writes books for adults and children and her next picture book "went around the houses, but found a home eventually and now it looks STUNNING!”

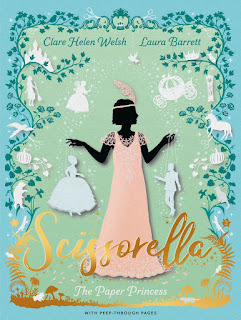

Picture Book Den children’s author, Clare Helen Walsh said, “I have a picture book coming out in 2022 that I first wrote at the end of 2018. I came back to it twice before getting it just right. There was something about it.”

New York based picture book author. Naomi Danis wrote to tell me: “Several of my picture books got published after ten or more years of being rejected. Enough of the rejections included some words of encouragement to keep me going. I submitted I HATE EVERYONE for 11 years, and WHILE GRANDPA NAPS for 17 years. I'm never sure if it is encouraging or discouraging for people to learn it can take so long.”

I don’t about you, but it gives me great hope to hear so many accounts of authors who didn’t give up on their work and who rejected rejection and found acceptance. Or, as Children’s Author, Emma Read put it, “I really needed to read this today. There is hope for the unloved stories after all.”

Gareth P Jones is the author of 45 published books – and countless more that lie in the dark recesses of his computer. After writing this blog he's thinking of going back and looking at them. His published works include The Thornthwaite Inheritance, Solve Your Own Mystery: The Monster Maker, Rabunzel and CinderGorilla.

And if you want to read the full twitter thread, you can find it here.

October 25, 2021

WRITING FAIRY-TALE RETELLINGS by Clare Helen Welsh and Friends

We all have our favourite childhood fairy tales, and so it’s not surprising that writers draw on well-known characters and narratives from traditional tales in their own writing.

This blog post will take a look at the reasons why re-imagined fairy tales are so loved and also look at what to consider when writing your own re-imagined tales.

To do that, I’ve recruited some special guests who’ve agreed to answer my most pressing questions about fairy tales and also offered their top tips!

GARETH JONES:

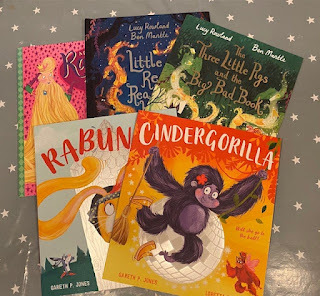

Gareth is the author of a fantastic series of fairy tale re-imaginings with Loretta Schauer, including Rabunzel and Cindergorilla. I was keen to know how he had found the market to be for fairy tale stories.

What do you think the market is like for fairy tale retellings?

Gareth said:

"Once I had written Rabunzel, I sent it directly to my editor, Melissa at Egmont (now Farshore) Books. It sat unread in her inbox for months but when she did read it, she liked it so much that she immediately called her sales team. They loved it too. She then picked up the phone and called me to tell me that they wanted the book as the first in a series. None of this is normal for me. I think that the story being an original retelling of a well-known fairy tale really helped. A long eared rabbit that gets locked in a high hutch is a joke that everyone instantly gets. Rabunzel Rabunzel, Let Down Your Ears! Whether or not the series will meet my publisher’s high expectations in terms of sales and foreign rights, I can’t say. I certainly hope it does. But I’ve never had such enthusiasm from a publisher about any of my previous picture books and I think a lot of that is down to it being a fairy tale retelling."

Gareth’s Top Tip for Writing Fairy Tale Retellings:

Fairy tales are problematic. They are often dark, weird and teach lessons that are no longer relevant to our world. They are also full of plot points that would have most editors reaching for the red pen if they were featured in an original story. Why doesn’t Cinderella’s slipper change back? In fact, why does the magic wear off at all? All of these things can be resolved, but it does take a bit of work. There are going to be four books in my series and my feeling is that with each one, I will stray further from the source material as I find ways to resolve these problems to create stories worth telling. With an original story you have to ask why this story is worth telling. With a fairy tale retelling, you have to question what you are bringing to the genre that is new, fresh, funny, interesting and worth hearing. I hope I’ve answered all these questions with Rabunzel and CinderGorilla. And I also hope that readers will also be interested to see what I’ve done with Snowy White next February. As for the fourth book? I’ll have to keep you posted on that because I’m not yet sure what it will be.

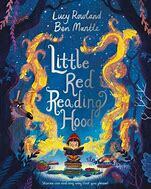

LUCY ROWLAND:

Former Picture Book Denner, Lucy, is no stranger to fairy tale re-imaginings. She is the author of ‘Little Red Reading Hood’ and ‘The Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Book,’ published by Macmillan and illustrated by Ben Mantle. She has also written ‘Rapunzel to the Rescue’ with Katy Halford (Scholastic).

From time to time I hear reservations about fairy tale stories, originating from the fact that they don't always have global appeal. Unfortunately, not all countries have the same much-loved tales, which can make them harder to sell globally. I was curious to know how Lucy’s titles had sold internationally.

How have your fairy tale retellings sold internationally?

Lucy said:

“When I started writing re-imagined fairy tales they were quite popular but there seems to have been a slight shift in the industry and have been a little harder to sell, perhaps because publishers have found them harder to sell abroad.”

Lucy’s texts, which are also in rhyme, have numerous co-editions. Indeed, the brilliant ‘Little Red Reading Hood’ has been translated into several languages including French, Italian and Spanish. Plus, Lucy and Ben have another re-imagined fairy tale in the works with Macmillan– ‘A Hero Called Wolf,’ which confirms to me that the rumours of co-editions don’t stop a publisher buying a fairy tale story if the concept is strong and marketable in enough markets.

Lucy’s Top Tip for Writing Fairy Tale Retellings:

"Try mixing it up! What would happen if you reversed character roles or wrote from a different character's viewpoint? What would happen if it was the same story but in a different world or setting?"

TRACY CURRAN:

Tracy has just released her debut picture book – Pumpkin’s Fairy Tale - congratulations, Tracy! The story has been brought to life with fabulous illustrations from Wayne Oram. I asked Tracy how she came up with the idea for Pumpkin’s Fairy tale and what it is about fairy tales that inspires her.

How did you come up with the idea for Pumpkin’s Fairy tale and what is it about fairy tales that inspires you?

Tracy said:

“I've always loved fairy tales, from my earliest childhood. They can be light and magical or dark and gritty, they impart valuable knowledge to readers and they are always evolving, which I find exciting. My idea for Pumpkin's Fairytale came from this deep affection I have for fairytales, my love of pumpkins and my curiosity of exploring a different point of view. I've always thought that, in the original story, Cinderella's pumpkin is rather cruelly cast aside after playing an important role. So, I thought I'd bring it (it became a him) to life and see what he had to say about the matter. 'Pumpkin's Fairytale' is the story he told me.”

Tracy’s Top Tip for Writing Fairy Tale Retellings:

“My top tip is to experiment with writing a version in both rhyme and prose. I think rhyme works beautifully in fairy tale retellings but two agents have now asked me to convert to prose, so why not have both up your sleeve! If you automatically prefer to write in prose, then just run wild and have fun!”

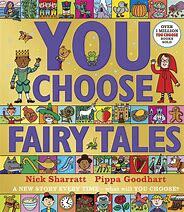

PIPPA GOODHART:

Pippa is the author of the You Choose series with Nick Sharratt. Her fairy tale version allows children to make up their very own fairy tale adventures where they choose what happens next. This is what Pippa had to say about fairy tales and why we love them!

What do you think it is about fairy tales and fairy tale characters that people love?

Pippa said:

"It must be partly the familiarity of the most well known tales. We’ve heard and seen and been aware of references to them from the youngest age, and there’s something comforting in both that familiarity and the knowledge that we all share those tales as part of our mutual culture. Maybe we sometimes hope for a new slant on that familiar tale? The most well established fairy tales are thrillingly shocking, but safely not in our real world, so we dare to play with big scary things within them."

Pippa’s Top Tip for Writing Fairy Tale Retellings:

"I'd say, think about the emotional heart of the tale. What is it REALLY about at an emotional rather than event level? For example, we all empathise with Cinderella for being the one who is mistreated and left out of things. We can all relate to that. But maybe we could see that from another angle? Long ago (and far away!) I wrote a version of Cinderella from the ‘ugly sisters’ point of view. Who is calling them ‘ugly’? How does that feel? What was it like for them when they acquired this beautiful perfect step-sister? There are multiple stories within each story, and its fun delving in to find them."

And last but definitely not least...

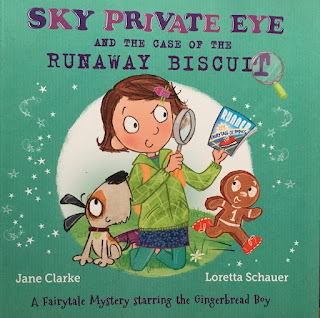

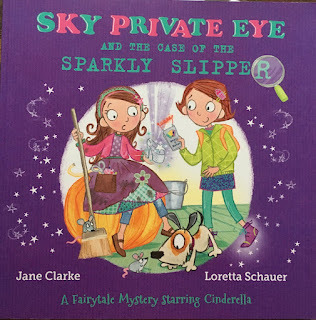

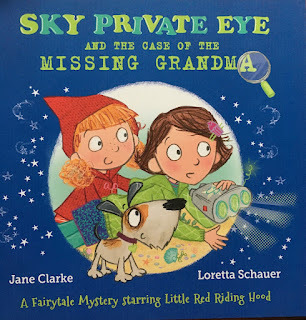

JANE CLARKE:

Jane is the author of a picture book fairy tale detective series, featuring Sky Private Eye. Titles include – ‘Case of the Missing Grandma,’ ‘Case of the Runaway Biscuit’ and ‘Case of the Sparkly Slipper’ based on the stories Red Riding Hood, Gingerbread Boy and Cinderella. The stories have been illustrated by Loretta Schauer and are published by Five Quills. I was keen to know how the process of writing these books was similar and/ or different to her other picture book texts.

Traditional tales need stick relatively closely to the original tale. Did you find this helpful or restrictive or something else? Can you tell us a little bit about your process?

Jane said:

"I found the process of taking the essential elements of a fairy tale and re-jigging the story with an original twist very different from writing other picture book texts. I enjoyed the challenge and had lots of fun adding creative elements to the story."

Jane’s Top Tip for Writing Fairy Tale Retellings:

"

As well as re-telling the main elements of the tale, reflect the pattern of how the tale is usually told. The rule of 3 is big in fairy tales!"

So to sum up, it’s worth bearing in mind that there are lots of retellings out there. As always, it’s important to make sure you are doing something different and/ or doing something in a different way. Is your premise a high concept idea that will cut through the noise and appeal to a wide market?

But don't let that put you off!

There is A LOT of love for fairy tale retellings. They often feature strongly in our childhoods and in school curriculums, too. They are based upon on characters and arcs we know well, creating opportune moments to switch things up and surprise the reader!

Have you written a fairy tale re-imagining? Do you like reading them? Which are your favourites?

BIO: Clare writes fiction and non-fiction picture book texts - sometimes funny and sometimes lyrical. Her latest picture book is a fairytale retelling inspired by the life and work of Lotte Reiniger. Scissorella is out on November 4th 2021. It's Clare's first book with Andersen Press and it has been wonderfully brought to life by Laura Barrett. You can find out more about Clare at her website www.clarehelenwelsh.com or on Twitter @ClareHelenWelsh.

October 19, 2021

The best defined single tip I’ve heard about writing narrative nonfiction: Candace Fleming and her VITAL IDEA by Juliet Clare Bell

We are all too aware of the many disadvantages and often grave difficulties faced in a long-term pandemic. Today I'd like highlight a positive thing for writers, particularly those who may not yet be published and who are really trying to hone their craft. With so much having been moved online, over here in the UK, we have had the chance to attend lots of US webinars about the craft of picture books that we’d never normally get the chance to (as they’d have previously happened in person). Given that narrative nonfiction is so much bigger in the States than it is here (and that many UK writers write with US publishers in mind as a result), nonfiction webinars have been particular useful.

I’ve taught writing classes and been part of a writing panel on narrative nonfiction, posted blog posts and I’ve written three nonfiction books, all commissioned but for different markets:

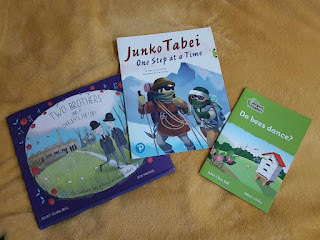

Two Brothers and a Chocolate Factory: The Remarkable Story of Richard and George Cadbury (illustrated by Jess Mikhail, BVT; Junko Tabei: One Step at a Time (illustrated by Evelt Janais) and Do Bees Dance (illustrated by Adam Linley)

And I’ve written several blogposts for the picture book den about narrative nonfiction -links. I’ve got loads of narrative nonfiction picture books which have been really useful for research and for comparison.

A small selection of my narrative nonfiction book collection

It’s something I’m really interested in, and especially so at the moment when I’m editing my latest narrative nonfiction picture book which I was thinking and researching about for a long time before I actually started writing it.

Well, there was. Many nonfiction writers might be familiar with this concept -and I’ve worked at doing this myself but I’ve never known it as well explained as Candace’s explanation. I can’t talk you through the whole webinar as it is hers -and anyone who’s interested in writing nonfiction, whether you’re already published in the genre or not, I’d highly recommend attending any sessions she does, but she’s blogged about this idea herself, so I can highlight the principle behind the general idea:

Giant Squid by Candace Fleming and Eric Rohmann

Candace Fleming’s

VITAL IDEA

for nonfiction.

Candace breaks it down into your TOPIC and your VITAL IDEA

When you set out to write a nonfiction book, you usually have the general topic in mind, and often you will start your research around the topic without yet knowing the angle you’re going to take. For example, with our book Two Brothers and a Chocolate Factory: The Remarkable Story of Richard and George Cadbury (illustrated by Jess Mikhail)

the broad topic was given to us. We were commissioned by Bournville Village Trust to write a children’s book on some aspect of the Cadbury family. That was all. So I set to work looking at the extraordinary archives attached to the factory in Bournville, UK, and at Birmingham Central Library, and I started reading books on the entire Cadbury family… There were many interesting stories to be told but after a good deal of research I found something that spoke to me more than all of the fascinating things I was reading. It was the story of Richard and George Cadbury and the creation of the chocolate factory and later, Bournville Village. So that was the TOPIC.

The story itself was fascinating but what really hooked me was looking into the personal archives and reading about why they wanted to do what they did: Richard and George were keenly aware of their good fortune and worked tirelessly -in many ways- towards sharing their good fortune with others. And this was my VITAL IDEA.

When I wrote the book, I didn’t know about the term VITAL IDEA but it’s really interesting to look back over the book and identify what Candace talks about. Once you’ve chosen your vital idea -and there can only be ONE in a picture book, then the rest of your research can be honed. This VITAL IDEA will be the heart of your story, and information you have -however interesting- that does not speak to the vital idea does not belong in that story. It can feel very harsh (but hey, you can put it in the back matter). Anyone who’s done a lot of research for a book knows there are so many things that would engage your reader, but your job is telling the story of your VITAL IDEA. It’s why you can have so many picture books on the same topic and they are all so different.

And this is what I love about narrative nonfiction: the vital idea for the story is really personal to the author. As Candace states, you need to think (once you know enough about your topic)

what is it that I -rather than anyone else- have to say about this topic to the child reader?

This concept (without using the term vital idea) is really interestingly discussed throughout the book Narrative Nonfiction Writers Dig Deep -where authors tell the personal stories behind why they chose their topics and the particular angle of the story:

Nonfiction Writers Dig Deep (edited by Melissa Stewart)

For me, when it came to the Cadbury story, I had grown up with the Quaker philosophy (my dad and his Irish family for generations had been Quakers) and although I’m not a Quaker, I went to Quaker Meeting regularly for a while as a child and have always liked a lot of their philosophy. Our local Amnesty International and CND groups where I grew up were dominated by Quakers -they were actively involved in trying to make the world a better place to live. And the more I read of George Cadbury’s writings on responsibility and society, the more I felt that their story was highly relevant to our current climate. I would find quotes from him, almost one hundred years old, that felt like they could have just been written. The Quaker philosophy was never going to take up a big part of the book (it was only referred to specifically in one sentence of the story) but I appreciated how it underpinned so much of what they felt and how they lived their lives. And we (Jess, the illustrator, and I) both lived within three or four miles of Bournville and the Cadbury factory. All these reasons came together to form the vital idea -the story that only I could tell in that particular way because of my engagement with the subject.

So there is only one vital idea and that has to be honoured throughout the story. And this will affect the mood and the language used. As Candace says, when you know your vital idea, you hone your language accordingly and this is what makes the language ‘soar’, which editors are always so keen to see.

Even though I’d pretty much applied this to the Cadbury book (and to the Junko Tabei book) without having used the terminology of vital idea, I applied it to my editing for my current book, which took a lot of research before I realised what I wanted at the heart of the story.

Lots of notes for my current manuscript

I can’t write it about here as the book is not out yet (nor even yet sold) but articulating the vital idea to myself, writing it down and honing it until it was really precise, meant that I was able to edit more effectively and ruthlessly, even killing my darlings -things I really wanted to share with the reader but weren’t important enough to my vital idea (but all is not lost: I get to sneak them into the back matter!) And I’ve been able to adapt the language slightly to help bring out that vital idea…

For anyone who is interested, I’d recommend checking out the Writing Barn webinars and all the SCBWI online events. Some of the digital SCBWI events are free to SCBWI members but the regional ones (like Candace’s one) have a small fee.

Do you have any brilliant tips for nonfiction writing? Have you applied the vital idea principle to your manuscript? I’d love to hear any thoughts or suggestions in the comments below. Thank you.

Juliet Clare Bell (always called Clare) is a children’s author of more than thirty books -but who will always love learning new perspectives on writing and thinking from fellow authors. www.julietclarebell.com

October 10, 2021

Should We All Celebrate? by Chitra Soundar

We All Celebrate, don’t we? Autumn is here and that means across the world, many communities are celebrating different festivals through the next few months as skies darken and the air turns cold and traditionally was the harvest season in the Northern Hemisphere.

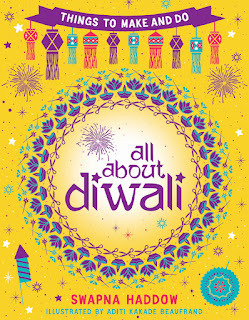

Last week marks the start of Dussera or Navarathri for me as a Hindu from India. Hindus across the world mark nine days of Dussera celebrations in different ways. And then it leads up to Deepavali or Diwali, one of the largest Hindu festivals. Did you know the same day is marked as a festival by Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs too?

As a writer of picture books and writing in the UK, I always wondered why there weren’t that many picture books about Deepavali (or Dussera for that matter) and why the lead up to Christmas, booksellers didn’t highlight this wonderful festival of lights?

So, when Albert Whitman from the US asked me to write a Deepavali book, I was absolutely elated.

Illustrated by Charlene Chua

Illustrated by Charlene ChuaIn some ways, the US had caught the wave a little sooner. These books were published both by indie and big publishing houses and very popular among South Asian families and western families in the US.

But my original complaint remained – why aren’t UK publishers not interested in other religious and cultural celebrations?

Do we need another Christmas book? Actually, do we need another Santa Claus / Father Christmas book? Even if we do, can they feature different communities celebrating Christmas in diverse ways?

Will the children that are not celebrating Christmas be missing out on their own celebrations?

To counter this dearth of books, I wrote a Diwali counting book (which will come out soon! Shh!).

Then I wanted to address the above question. Can I highlight celebrations that are not so well-known? So I pitched this book (We All Celebrate) to Tiny Owl and they loved it. With Jenny Bloomfield's glorious illustrations, this book will be out this autumn, right in time for the festival season.

Illustrated by Jenny Bloomfield and published by Tiny Owl Books

Illustrated by Jenny Bloomfield and published by Tiny Owl BooksBut back to Deepavali (or Diwali as many call it) books in the UK... I went looking for books that celebrate this festival, written by authors and illustrators from the culture the festivals belonged to.

So, if you don’t see Peppa Pig or Mr Men Celebrating Diwali in this list, that’s why.

Here are two that came out decades ago.

And here are two just out this year, right in time for this year's festival. What are you waiting for? Go and grab these!

That is it. Two new books in decades.

While I have to scroll through a long list of Christmas books, books about Diwali, I can count on one hand - published across four decades.

We need more books about all the little and big celebrations everyone is celebrating across our country – because we all celebrate and so, let’s celebrate together.

Here is a call to action!

Are you a picture book writer? Do you celebrate a festival that we are not familiar with? Do you have unique traditions of celebrating a well-known festival? Then why don't you try writing a picture book about it?

Writing about a festival need not be dry or didactic. It can be full of wonder and storytelling, it can be filled with activities and hands-on fun and it can be joyous inviting others to join in.

Have a go! Write something different about Christmas or pick another festival from your own heritage and tell us a story that resonates universally!

Chitra Soundar is the author of over 60 books for children. She has written over 20 picture books and new ones are on the way. She loves celebrating with family and friends, cooking up a meal and sharing stories together. Find out more about her at www.chitrasoundar.com and follow her on Twitter @csoundar.

October 3, 2021

From Here to There . . . Why SCBWI is Key to Getting YOU There

SCBWI turns 50 this year. It started out when Lin Oliver and Stephen Mooser, two newbie writers, commissioned to write some children’s books, sought to learn more about their craft and the publishing industry. Finding no established organization, they decided to start something. Responding to their advert, Sue Alexander suggested getting in touch with published author Jane Yolen, who was keen to help out.

Lin Oliver, Founder and Executive Director, SCBWI

Lin Oliver, Founder and Executive Director, SCBWI

Stephen Mooser, Founder, SCBWI

Stephen Mooser, Founder, SCBWI

At the library, Lin read and researched the children’s book section, then wrote to 10 authors inviting them to a conference. She received 10 replies. Dr Seuss sent an apology in the form of a hand-typed letter: ‘the more I talk as a talking author, the less I write as a writing author’. Steve’s dad licked the mailing labels and Lin’s mum made the potato salad for lunch.

And from there, it grew . . .

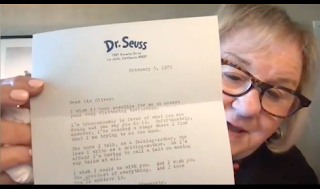

At the SCBWI Big 50 Conference,

At the SCBWI Big 50 Conference, Lin shares the letter she received from Dr Seuss

The founding members started a monthly Bulletin at Lin’s kitchen table (it is still published today), and the friends started pouring in: Judy Blume, Uri Shulevitz, Sid Fleishman, Tomie dePaola, Judy Blume, Ezra Jack Keats, Dawn Freeman, Myra Cohn Livingston, Mildred Fitzwalter, James Marshall, Walter Dean Myers, Laurence Yep, Arnold Lobel, Lee Bennett Hopkins, Paula Danziger - the great voices upon which the organization was built, who became friends and colleagues, organizing conferences and meet-ups.

Acclaimed author Jane Yolen was a founding member of SCBWI.

Acclaimed author Jane Yolen was a founding member of SCBWI.

Bear Outside is her 400th book.

More friends joined: Jerry Pinkney, Lois Lowry, Arthur Levine, Bruce Coville, Christopher Paul Curtis, Pam Munoz Ryan, Elaine Konigsburg, Linda Sue Park, Karen Cushman, Virginia Hamilton and Dan Santat – the community was formed, and still is, by volunteers.

The Bulletin, May 2021 artwork by

The Bulletin, May 2021 artwork by Maple Lin

Now, 50 years later, the SCBWI is the largest international professional organization for children’s book creators with over 26,400 members in 70 regions around the globe. The British Isles region, founded in 1996 by author Gloria Hatrick and E. Wein, started in a similar way, and now its published members are those to whom new(er) authors and illustrators find inspiration – Candy Gourlay, Chitra Soundar, Jane Clarke, Sara Grant, Mo O’Hara, Kathy Evans, Sarah McIntyre, Bridget Marzo, Jasmine Richards, A M Dassu, Patrice Lawrence, Teri Terry, Sarwat Chadda, James Brown, Loretta Schauer and many others.

SCBWI British Isles Conference Mass Book Launch 2019

SCBWI British Isles Conference Mass Book Launch 2019Why am I telling you all this? I was inspired by a talk at the SCBWI big 50 summer conference by Dan Santat in which he spoke about his creative journey from the beginning to #1 New York Times bestselling and award-winning author and illustrator. What struck me was that he talked about how when you look back at the creative path you took, and you are in awe of what has transpired in the all the years you’ve been in the business; you look back at your work and you see that there is really no ‘there’ because you continue to grow, find out about yourself and – and, here’s the important bit – you do this with SCBWI as your family.

#1 New York Times bestselling and award-winning author and illustrator

#1 New York Times bestselling and award-winning author and illustrator

Dan Santat and his picture books

In the words of Lin Oliver: Picasso once said ‘Inspiration is great, but when it comes, it better find you working’. So, we must combine our talents, with our training and our dreams and our passions and then combine it with hard work. But even more than this, we are more if we are part of a supportive community because the path to creation is often a very solitary one.

When you are part of a community of critique groups, networking connections, friendships and happenstance opportunities such as those you find in SCBWI, standing on the shoulders of the published friends who came before you, innovating and finding new paths then the creative journey as you grow from here to ?there?, the possibilities are infinitely expanded.

The themed Mass Book Launch cake features mini book covers made out of icing

The themed Mass Book Launch cake features mini book covers made out of icing

What you get out of the SCBWI isn’t something you can quantify – it’s somehow more than the sum of all its parts. Sure, your membership offers practical things like

• critique groups

• webinars, podcasts and conferences

• mentorships, retreats and masterclasses

• 1-1s with industry professionals

• scholarships, grants & awards

• industry insider newsletters

• marketing & publicity opportunities, training and support

• porfolio showcases

• mass book launches

But did you know that you can . . .

• banter with an agent at a party?

• make like-minded friends – the kind you can ask questions of at all stages of your career?

• make insider connections with industry professionals and super-famous authors & illustrators by organizing an event you’ve always dreamed about?

• raise your profile by writing for and editing for Words & Pictures, the British Isles’ regional magazine, or contributing illustrations?

• get top tips on how to connect with those disruptive kids in your school visit audience?

• buddy up to create promotional opportunities?

• get discovered through the Undiscovered Voices initiative?

• make some art that might land you a 1-1 meeting with an art director in NYC?

• get your book cover made out of icing on a Mass Book Launch cake?

• eat pizza with a librarian?

Author Mike Brownlow with his icing cake cover of Ten Little Monsters at the SCBWI Annual Mass Book Launch

Author Mike Brownlow with his icing cake cover of Ten Little Monsters at the SCBWI Annual Mass Book Launch

These are just some of the priceless gems that you can tap into at whatever stage of your career you find yourself.

Here’s a story about HOW IT'S WORKED FOR ME:

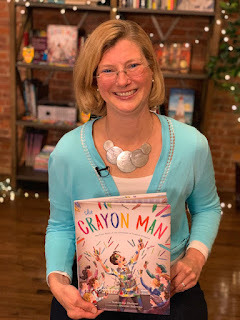

KitLit TV studio recording of the read-aloud

KitLit TV studio recording of the read-aloud with Julie Gribble in NYC

Some time ago, I was really STUCK with my picture book writing – I needed a new direction. Cue fellow SCBWI member and PB Denner, Juliet Clare Bell, who recommended an online non-fiction writing course with Kristen Fulton. As part of the course, I wrote a new book. Shortly afterwards, I attended an SCBWI conference, where I met author Sandra Nickel, who was a faculty member and whom I knew through SCBWI France/Switzerland. Sandra’s agent, Victoria Wells Arms was also presenting at the conference. At the drinks party after the wrap-up, Sandra invited me to meet her agent. This makes it sound easy, but I was not at all sure I could find the courage to even talk to her. After the conference, I pitched my book to Victoria and she became my agent, too. Encouraged by the advice and success of fellow SCBWI authors Candy Gourlay, Sara Grant and Mo O’Hara who run a fabulous author bootcamp to help empower us to market ourselves successfully, I peeked out from under my rock and decided to apply for an SCBWI Marketing grant. After all, what did I have to lose? Well, I got it! I used more SCBWI Connections to help me organize a mini book tour to launch my book, THE CRAYON MAN, and even film a Read Aloud with KitLit TV (another SCBWI connection!), and so it goes. @font-face {font-family:Arial; panose-1:2 11 6 4 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:10887 -2147483648 8 0 511 0;}@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Trebuchet MS"; panose-1:2 11 6 3 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:647 0 0 0 159 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}a:link, span.MsoHyperlink {mso-style-priority:99; color:blue; mso-themecolor:hyperlink; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;}a:visited, span.MsoHyperlinkFollowed {mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; color:purple; mso-themecolor:followedhyperlink; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-fareast-language:JA;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

Paula Danziger of Amber Brown fame was an inspiration

Paula Danziger of Amber Brown fame was an inspiration

to never give up and stay true to your voice.

It was an inspirational talk for the SCBWI British Isles in London in the early 90’s (when it consisted of only a handful of members), by legendary author Paula Daniziger – one of those aforementioned founding members Lin recruited – that inspired me to join and, soon after, volunteer. Who knew I’d still be volunteering and going ‘there’ on my picture book craft journey alongside fellow members some 23 years later?! (Psst, it even took me to the Palace to meet Prince Charles, who knew?!)

Truly, a gold mine of friendship, connections, and information about publishing the world over is yours with your SCBWI membership if you make the most of it, even more if you volunteer. Plus, volunteering is meant to be good for your health!

All those moments of SCBWI glitter add up to something precious – a heartfelt THANK YOU to Lin, Steve and all the other authors and illustrators and creatives who have built the treasure that is SCBWI!

____________________________________________________________

Natascha Biebow, MBE, Author, Editor and Mentor

Natascha Biebow, MBE, Author, Editor and Mentor Natascha is the author of the award-winning The Crayon Man: The True Story of the Invention of Crayola Crayons, illustrated by Steven Salerno, winner of the Irma Black Award for Excellence in Children's Books, and selected as a best STEM Book 2020. Editor of numerous prize-winning books, she runs Blue Elephant Storyshaping, an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission, and is the Editorial Director for Five Quills. She is Co-Regional Advisor (Co-Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. Find her at www.nataschabiebow.com

September 26, 2021

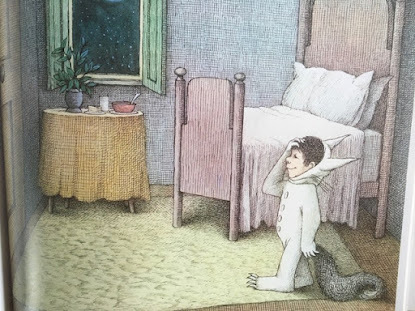

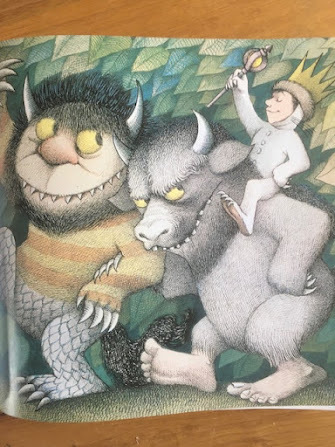

Taming Wild Things; Where Sendak's Wild Things Came From, by Pippa Goodhart

For this post I am simply going to quote Maurice Sendak from his acceptance speech given to the American Library Association in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1964, in which he answers the question, ‘Where did you ever get such a crazy, scary idea for book’, referring to his, then recently published picture book, Where The Wild Things Are.

Where The Wild Things Are is a simple book in terms of the word count and plot, but, my goodness it carries a rich heavy load of story, and it’s fascinating to glimpse where that emotional depth and insight comes from -

‘During my early teens I spent hundreds of hours sitting at my window, sketching neighborhood children at play. I sketched and listened, and those notebooks became the fertile field of my work later on. There is not a book I have written or a picture I have drawn that does not, in some way, owe them its existence. Last fall, soon after finishing Where The Wild Things Are, I sat on the front porch of my parents’ house in Brooklyn and witnessed a scene that could have been a page from one of those early notebooks. I might have titled it ‘Arnold the Monster.’

Arnold was a tubby, pleasant-faced little boy who could instantly turn himself into a howling, groaning, hunched horror – a composite of Frankenstein’s monster, the Werewolf, and Godzilla. His willing victims were four giggling little girls, whom he chased frantically around parked automobiles and up and down front steps. The girls would fee, hiccupping and shrieking, ‘Oh, help! Save me! The monster will eat me!’ And Arnold would lumber after them, rolling his eyes and bellowing. The noise was earsplitting, the proceedings were fascinating.

At one point, carried away by his frenzy, Arnold broke an unwritten rule of such games. He actually caught one of his victims. She was furious. ‘You’re not supposed to catch me, dope,’ she said, and smacked Arnold. He meekly apologized, and a moment later this same little girl dashed away screaming the game song: ‘Oh, help! Save me!’ etc. The children became hot and mussed-looking. They had the glittery look of primitive creatures going through a ritual dance.

The game ended in a collapse of exhaustion. Arnold dragged himself away, and the girls went off with a look of sweet peace on their faces. A mysterious inner battle had been played out, and their minds and bodies were at rest, for the moment.

I have watched children play many variations of this game. They are the necessary games children must conjure up to combat an awful fact of childhood: the fact of their vulnerability to fear, anger, hate, frustration – all the emotions that are an ordinary part of their lives and that they can perceive only as ungovernable and dangerous forces. To master these forces, children turn to fantasy: that imaged world where disturbing emotional situations are solved to their satisfaction. Through fantasy, Max, the hero of my book, discharges his anger against his mother, and returns to the real world sleepy, hungry, and at peace with himself.

Certainly we want to protect our children from new and painful experiences that are beyond their emotional comprehension and that intensify anxiety; and to a point we can prevent premature exposure to such experiences. That is obvious. But what is just as obvious – and what is too often overlooked – is the fact that from their earliest years children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions, that fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday lives, that they continually cope with frustration as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming Wild Things.

It is my involvement with this inescapable fact of childhood – the awful vulnerability of children and their struggle to make themselves King of All Wild Things – that gives my work whatever truth and passion it may have.’

There is more, equally interesting, but, to read it you’ll need to get hold of a copy of Caldecott & Co. by Maurice Sendak.

September 12, 2021

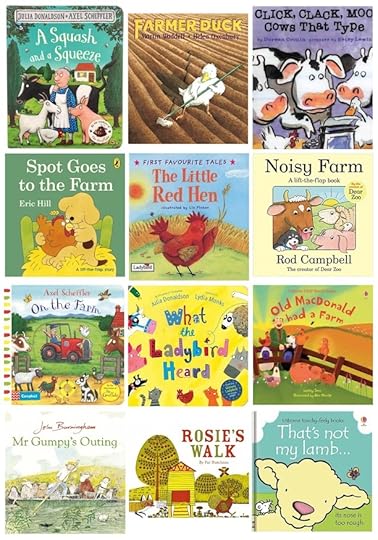

Fury at the Farm (with Mini Grey)

George Monbiot lays the blame on picture books.

George Monbiot lays the blame on picture books. Talking about making the film Rivercide with Franny Armstrong (livestreamed on 14th July this year), the environmentalist George Monbiot says:

“When I say farming, what image comes to mind? Well, I bet for quite a few of you, at least fleetingly, a particular kind of picture flitted across your mind. A picture with which we’re surrounded when we’re very small children, at the very dawning of consciousness. Many of the books produced for very young children are about farms; and most tell broadly the same story.”

He also writes that “even the grim realities of industrial farming cannot displace the storybook images from our minds. At a deep, subconscious level, the farm remains a place of harmony and kindness—and this suits us very well if we want to keep eating meat”.

So what’s a picture book farm?

George Monbiot says: “The animals – generally just one or two of each species – live in perfect harmony with the rosy-cheeked farmer, roaming around freely and talking to each other, almost as if they were members of the farmer’s family. Understandably there’s no indication of why they might be there, what happens to them in life, how and why they die.”

A picture book farm is a random collection of one or a few of several animals living together with a farmer – it’s a kind of animal sanctuary. No-one gets killed. The main danger is usually foxes or wolves. Old MacDonald had a picture book farm. Eee-i-eee-i-oh….

But I love picture book farms: it’s a lovely mythical place to explore – a family of animals who can talk to each other, it’s a great setting for a story to unfold. We love to see animals living together and talking together. Little children like to make animal noises and all pat the bone. It’s familiar. It’s fun.

And lots of ingenuity and creativity and humour can be had with farm animals.

Here’s Farmer Duck, one of my all-time favourites. It’s so thrilling to see all the animals getting together to discuss their cunning plan to outwit and oust the fat and lazy farmer. It’s so beautifully imagined and lit and painted by Helen Oxenbury. What a perfect place for a story.

(Also secretly I’m reminded by the cow of the classic Larson Far Side cartoon ‘Car!’)

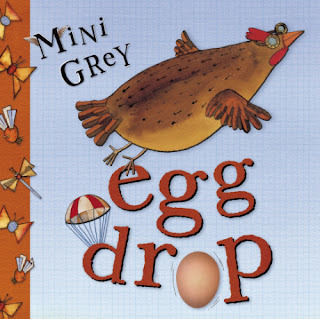

And I’ve been there too. My first book, Egg Drop, is narrated by a chicken and set on a bucolic farm idyll with gently distressed chicken houses.

Here's Chris Mould brilliantly illustrating Animal Farm and he says about the story: “It works on different levels. If you look at what it is saying politically, it will always be relevant as a text, but from a child’s point of view it’s also about animals talking to each other, and that’s great fun.” There's upheaval and horror and sadness in Animal Farm - but the animals have agency. Just imagine the same animals transposed into a factory farm. How would that look?

Here's Chris Mould brilliantly illustrating Animal Farm and he says about the story: “It works on different levels. If you look at what it is saying politically, it will always be relevant as a text, but from a child’s point of view it’s also about animals talking to each other, and that’s great fun.” There's upheaval and horror and sadness in Animal Farm - but the animals have agency. Just imagine the same animals transposed into a factory farm. How would that look? Older children's books do address what really happens on farms - here are a couple...

Older children's books do address what really happens on farms - here are a couple...The reality of Factory Farms

But in Rivercideit’s revealed that factory farms are the leading source of river pollution. So what lies hidden beneath? What’s the reality of factory farms?

Here’s THE LIST of FACTORY FARM BY-CATCH

Approximately two in three farmed animals are now raised in “factory farms” worldwide (Compassion in World Farming 2018).

The biggest cause of river pollution in the UK is farming.

Intensive chicken farms will house about 40,000 birds that will be cleared out, killed and replaced every 40 days or so.

You don’t need a permit for a farm if you’ve got fewer than 40,000 chickens.

The UK now has some 2,000 chicken factories.

Even so-called ‘free range’ isn’t necessarily what you’d think it was. Here are the images Happy Eggs want you to imagine of their ‘free-range’ chickens:

….and here’s the reality: (pictures screen-grabbed from Rivercide.)

(Happy Eggs are one of the biggest 'free-range' egg producers in the UK.)

It’s impossible to put this in picture books

Well, how about trying this as the setting for your picture book?

Or this?

Where can you go? Clearly, the Great Escape. But for very little peoples, it’s too unacceptable, too haunting, too disturbing. And what does THIS tells us about factory farming? It’s too unacceptable, too haunting, too disturbing. The truth is, we wouldn’t be able to read a picture book about factory farming to a very little child – it’s too upsetting. So if it’s too unpleasant to bear in picture books, it must be the same in real life. But we don’t get to see it.

“The history of intensive animal farming has led to a progressive removal of animals from public view” (Stewart and Cole 2009).

The farm myth in picture books acts as a very useful screen.

Picture books have helped to shield hidden factory farms, acting as a screen that we don’t worry about looking behind, because we all feel farms are friendly places. Intensive farming is hidden, invisible, and also shielded by the visible happy farms we can see when we go for a nice walk (like the lovely shaggy beasts I see grazing on Wittenham Clumps).

So let’s have a look at the Invisible.

The Invisible is the true cost of cheap meat.

THE COSTS

Enormous amounts of animal shit that the landscape can’t absorb

Nitrogen-fuelled algal blooms in rivers, dying rivers

Misuse/overuse of antibiotics (and don’t even mention sea lice on farmed fish)

Methane emissions

The loss of small farms, as they can’t compete with the economies of scale of huge ones

Animals inside can’t forage and need feeding. Soya to feed livestock is a main cause of deforestation in the Amazon (and don’t even talk about feeding farmed fish.)

The suffering and discomfort and misery of millions of animals

And don’t forget fish farms – fish can be miserable too.

Can we make the invisible visible?

What about a packaging revolution so it is impossible to buy a product containing factory-farmed animal product without knowing about it? Let’s do a magic trick and make the invisible visible.

If policy makers are not up to banning or limiting factory farms (which is what they should do), I want to make it impossible to buy intensively farmed meat without knowing who it was, and that it’s from an industrial livestock unit. (Honestly, it shouldn't deserve the word 'farmed'. )

Look at cigarette packaging. I don’t know if you’ve hung around with smokers lately – but I have, and I noticed that the horror on cigarette packets is impossible to ignore.

The packaging on animal products should also be impossible to ignore.

Do picture book makers have a responsibility?

Well, maybe. But maybe we should make our farming more like picture books. We should “eat meat as our grandparents did, as something rare and special” and “recognise that an animal has been sacrificed to serve our appetites, to observe the fact of its death: is this not the least we owe it?” (George Monbiot 2015)

Living within your landscape

Landscapes need animals. All farmed animals should be able to live in a natural landscape and be able to behave as they naturally would. (This means really low stocking densities. And yes that means really expensive animal products. But we could subsidise ethical meat.) Meadows need grazing animals; a proper landscape would have top predators too, but around here, they’re us. We live in a landscape (which is often a river valley): the landscape is our framework, and we must only put in it the amount of animals, houses and waste products that it can support without being degraded – which means treading lightly. The signs of environmental collapse: disappearing creatures, algal blooms, polluted rivers – mean we are dumping too much onto the landscape and taking too much out. Humanity’s long term project has got to be to learn to live in balance with the Earth: balance in CO2, water, habitat, wildlife, landscape.

The picture book superpower is to be able to put the reader into the place of someone else.

Someone who might be a chicken.

So here, to end, is a story for you: the story of Doris, the chicken who changed the world.

Doris the Chicken appeared in the Puffin Book of Big Dreams, published by Puffin Books in 2020.

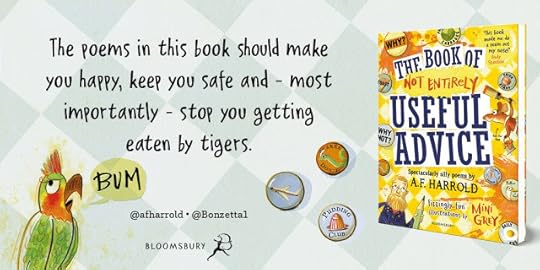

Mini's latest published book-involvement is The Book of Not Entirely Useful Advice, with AF Harrold. Her BlogSite is at Sketching Weakly.